Introduction

Low- and medium-level radioactive waste is primarily disposed near the surface. In recent years, there has been growing interest in the disposal of rock caves, to increase safety. The Chinese 14th Five-Year Plan includes provisions for constructing the first rock cave disposal facility for low- and medium-level radioactive waste in Guangdong Province. The cave repository is situated in a granite layer with four barriers to prevent nuclide migration. Gaomiaozi bentonite serves as the backfill material, with granite as the surrounding rock [1]. However, barrier systems can fail under unforeseen circumstances such as extreme weather and geological activities during long-term disposal, enabling groundwater to transport nuclides such as 137Cs, 60Co, 90Sr, and 131I into the biosphere, thereby irreversibly harming the ecological environment [2]. Among these nuclides, 90Sr is a prominent fission product of radioactive waste that is known for its solubility and mobility in water [3-5]. This nuclide is highly biologically toxic and can inflict considerable damage to the bone marrow and bone tissue, increasing the risk of cancer and leukemia [6]. Therefore, close monitoring of the adsorption and migration of 90Sr in repository barrier materials is essential for long-term safety assessments.

Colloids are usually particles with diameters of 1 nm to 1 μm suspended in a fluid [7]. Colloids have large specific surface areas and charged surfaces, resulting in a high affinity for the vast majority of nuclides in repositories. The many types of colloids in the water environment of waste repositories include inorganic colloids derived from clay minerals, iron and aluminum oxides/hydroxides from the corrosion of waste containers, organic colloids formed from organic macromolecules and humic acid, and biological colloids, such as bacteria and viruses. Bentonite is used as backfill material and is abundant throughout the repository. Consequently, bentonite colloids are the primary colloidal species in nuclear waste repositories [8]. Bentonite colloids are produced by underground erosion and soaking of bentonite. However, the subsequent continuous loss of bentonite and degradation of engineering barriers [9] threaten the blocking capacity of the engineering barrier system of the repository. Bentonite colloids have large specific surface areas and can chemically adsorb or form complexes with nuclides. Thus, bentonite colloids transport nuclides, affecting the migration behavior of nuclides in the repository. Several studies have confirmed that bentonite colloids significantly affect the migration of radionuclides in repositories [10-13]. Consequently, considering the impact of bentonite colloids is crucial for assessing the security of repositories.

Granite serves as the final barrier in a repository, bridging the engineered barrier and the biosphere. Bentonite colloids transporting radionuclides through the engineered barrier come into direct contact with granite. During this interaction, bentonite colloids may be retained in the granite regardless of radionuclides, thereby penetrating the granite and enabling nuclides to be retained in the granite. Bentonite colloids affect nuclide migration in granite through a complex and reversible process, which may have different effects on different nuclides. Numerous studies have shown that the presence of bentonite colloids may diminish the ability of surrounding rock barriers to block nuclides. Katezirina et al. [14] investigated the migration behavior of 137Cs on fractured granite in the presence of bentonite colloids and found that bentonite colloids transport a small portion of 137Cs through the granite. Similarly, Zheng et al. [2] investigated the impact of gibbsite and sodium bentonite colloids on U(VI) transport in saturated granular granite columns. The strong binding affinity of U(VI) to the colloids enhanced U(VI) transport. However, the interactions and cotransport modes of colloids and nuclides may also inhibit or eliminate the effect of bentonite on nuclide migration in granite [15]. Elo et al. [16] conducted column experiments and showed that mobile bentonite colloids have a negligible effect on Np(V) migration in granite. By contrast, Timothy et al. [17] found that Am(III) transport by bentonite colloids is governed by the desorption of Am(III) from specific binding sites on the colloids. Bentonite colloids weakly promote Am(III) transport. Most of the numerous studies that have been performed on bentonite colloids have focused on either the adsorption properties of colloids or the direct impact of colloids on nuclide migration. However, few experiments have been conducted on joint adsorption and migration to comprehensively investigate the influence of bentonite colloids on nuclide migration in granite in terms of adsorption capacity.

Hence, in this study, strontium (Sr) was considered as the target nuclide, sampling it from the surrounding granite and backfill material (bentonite) in the first cave repository for low- and medium-level radioactive waste in China. The physical and chemical properties of granite and bentonite in the area were characterized, and bentonite colloids were produced using local groundwater. Batch adsorption experiments were performed to compare the adsorption of Sr2+ on bentonite colloids, bentonite, and granite. The mechanism of Sr2+ adsorption onto bentonite colloids was elucidated by combining empirical models with characterization methods. Accordingly, dynamic migration experiments were conducted to investigate the impact of bentonite colloids on the migration behavior of Sr2+ in granite columns, with a particular focus on the influence of a multinuclide system on Sr2+ migration. This study provides insights into accurate estimation of the potential risk of Sr migration in cave repositories for radioactive waste.

Materials and Methods

Geological materials

Granite samples were obtained from granite rock formations near a low- and medium-level radioactive waste repository in Guangdong Province. The samples were extracted from a depth of 173 m with a specific surface area of 2.54 m2/g. The bentonite samples were obtained from Gaomiaozi, Inner Mongolia and had a measured specific surface area of 38.278 m2/g. The elemental and oxide compositions of both granite and bentonite samples were determined using an Axios series X-ray fluorescence spectrometer (XRF). The findings are presented in Table1. Groundwater samples were extracted from boreholes proximal to the cave repository at depths ranging from 148 to 173 m. During sampling, the groundwater had a flow rate of 41.5 L/min, conductivity of 298.5 μS/cm, and pH of 6.7. Groundwater samples were analyzed for major cation and anion compositions using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and ion chromatography, respectively, and the results are shown in Table 2.

| Element (%) | SiO2 | Al2O3 | K2O | Fe2O3 | CaO | Na2O | MgO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granite | 67.68 | 10.84 | 8.16 | 5.72 | 5.03 | 0.56 | 0.34 |

| Bentonite | 74.02 | 15.56 | 1.82 | 2.31 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 2.86 |

| Element (mg⋅L-1) | Al3+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | Si4+ | Mn2+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.379 | 39.651 | 2.134 | 3.530 | 36.484 | 0.562 | |

| Fe3+ | Cl- | F- | - | |||

| 0.616 | 3.87 | 0.529 | 17.7 | 4.65 | - |

Experimental instruments and materials

Transmission micrographs of the samples were obtained using field-emission transmission electron microscope (FETEM) (Libra200FE, Zeiss, Germany). Electron micrographs of the samples were obtained using a high-resolution cold-field emission scanning electon microscopy / energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) (UItra55, Zeiss, Germany). The Zeta potentials (Zeta) of the samples were measured using a potentiometer (ZetaPALS, Brookhaven, USA). The mineral compositions of the samples were determined by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (TD-3500, Panaco, Netherlands). The functional group compositions of the samples were determined using a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) absorption spectrometer (Frontier, Perkin Elmer, USA). Colloid mass concentrations were measured using a gravimetric method combined with ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry (V-5800, Yuanyi, China). The residual Sr2+ concentration in the solution was measured by ICP-MS (iCAP6500, Thermo Fisher, USA).

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) was obtained from China West Long Science Co., Ltd. (China). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%), ferric chloride (FeCl3, 99%), calcium chloride (CaCl2, 99%), magnesium chloride (MgCl2, 99%) and potassium chloride (KCl, 99%) were obtained from Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (China). Caesium chloride (CsCl, > 99%) and strontium chloride hexahydrate (SrCl2⋅6H2O>99%) were procured from Aladdin Reagent Factory (China), and cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2⋅6H2O, > 99%) and nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2⋅6H2O, >99%) were purchased from Macklin Reagent Company (China). All chemical reagents and drugs used in this study were of analytical grade and were not further purified before use.

Preparation of bentonite colloids

Ten grams of bentonite powder (200 mesh) were weighed and dispersed in 1 L of ultrapure water with a resistivity of 18.25 MΩ·m. The powder was dispersed by ultrasonic agitation for 30 min, followed by magnetic stirring for 4 h to ensure uniform mixing. The mixture was allowed to settle at room temperature for two days. The resulting sample was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min to remove particles larger than 1 μm. The separated solution was transferred to a dialysis bag for purification. The dialysis water was periodically replenished, and the pH and conductivity were monitored using pH and conductivity meters, respectively. The conductivity of the solution decreased from 160 μS/cm to 10.58 μS/cm during dialysis, indicating that the colloidal dispersion had a low ionic strength and therefore an appropriate dispersion coefficient. The prepared colloidal samples were stored in a sealed conical flask at room temperature until further use. The colloidal concentration was determined by using the differential gravity method combined with UV spectrophotometry, following the method used in our previous study [18]. A colloidal sample solution with a desired concentration gradient was prepared based on the mass concentration obtained using the differential gravity method. The full spectrum of the colloidal solution was scanned using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, and the characteristic wavelength of the solution was determined to be 240 nm. The colloid mass concentration was determined by generating a standard curve (R2 = 0.999) from the data.

Adsorption/desorption experiments

Batch adsorption experiments were conducted on two groups: a powder (S1) and colloidal (S2) group, to investigate the adsorption behavior of Sr2+ on geological barrier materials and colloids, respectively. Each experiment was repeated three times, and the average measurement was recorded. For Group S1, several portions of granite (Gt) and bentonite (Bt) powder were weighed and placed in polypropylene centrifuge tubes, to which 4.5 mL of deionized water was added. Group S2 was prepared by adding a bentonite colloidal (BC) solution to the centrifuge tubes. Samples from both groups were equilibrated overnight at room temperature. Subsequently, 4.5 mL of Sr2+ solution was added to each sample, to achieve the desired nuclide concentration. In experiments, 4.5 mL of a mixed solution of Sr2+ and the respective ions were added to the sample, to investigate the influence of specific ions on adsorption. The pH values of the samples were adjusted using trace quantities of hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. The samples were placed in an oscillating box and agitated until the adsorption equilibrium was reached. The equilibrated samples were centrifuged at 10000 r/min for 30 min to separate the solid and liquid phases. The supernatant of the Group S1 samples was directly diluted, and the residual Sr2+ concentration was determined using ICP-MS. To ensure that the bentonite colloids were completely separated from the adsorbed solution, the supernatant of the S2 group was passed through a 0.1 μm filter membrane before the residual Sr2+ concentration in the liquid phase was determined. A desorption experiment was conducted after the completion of the adsorption experiment. The suspension that remained at the end of the adsorption experiment was removed to yield a granite sample with adsorbed Sr2+. An equal volume of solution and pH were added to the sample and shaken under the same experimental conditions as those used for the adsorption experiment, to reach desorption equilibrium. The sample was centrifuged, filtered, and analyzed using ICP-MS to determine the Sr2+ concentration in the supernatant.

Migration experiment

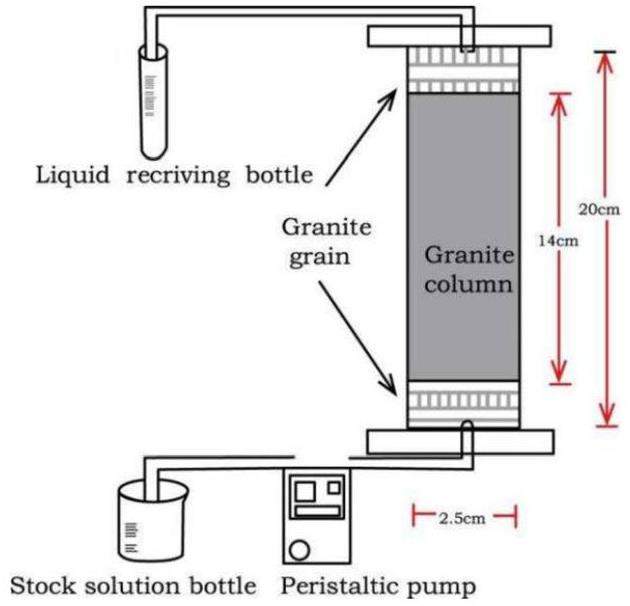

The migration experiment was performed using a dynamic shower column with a length of 20 cm and diameter of 2.5 cm, which was filled with a soil column with an actual length of 14 cm. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 1. Coarse-grained granite (60-80 mesh) was wet-filled into the shower columns. Nylon nets were placed at both the upper and lower ends of the column to prevent the granite powder from escaping the eluent during the filling process. The filled granite was continuously washed with an upward flow of ultrapure water at a constant rate until water flow equilibrium was reached in the shower column to ensure a stable moisture content throughout the experiment.

The Sr2+ migration experiment was performed on the equilibrated shower column in two stages: transport and elution. Prior to conducting the experiment, a Sr2+ solution (Sr2+ and inoized water), BC-Sr2+ solution (bentonite colloid, Sr2+), and mixed solution (bentonite colloids, Sr2+, Cs+, Co2+, Ni2+) were prepared, each with a nuclide concentration of 100 mg/L along with a bentonite colloid concentration of 250 mg/L, to simulate the expected near-field range of spent fuel storage. During the transport stage, the prepared solution was continuously added to the lower end of the granite column at a fixed flow rate of 4 mL/h via a peristaltic pump. Samples were periodically withdrawn and diluted for testing until the nuclide concentration stabilized. During the elution stage, ultrapure water was continuously pumped into the granite column at a constant flow rate of (4 mL/h). Regular sampling and testing were conducted until the simulated nuclide concentration in the detection solution approached zero.

Data analysis

The adsorption capacity for Sr2+(qe) was determined for granite, bentonite, and bentonite colloid. The migration of Sr2+ in the granitic media was analyzed by calculating the longitudinal diffusion coefficient (DL), which is expressed as:

Adsorption model

The adsorption data obtained at different contact times were fitted using pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models and the Weber-Morris (W-M) internal diffusion model to obtain kinetic information on the mineral and colloid surface adsorption, which was subsequently used to infer the adsorption mechanism of the sample. The kinetic models are provided below [19, 20]:

The adsorption data obtained at different Sr2+ concentrations were fitted using the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm models. The Langmuir isotherm model assumes single-layer adsorption and the attraction between molecules decreases sharply as the distance between the molecules increases. The Freundlich isotherm model is based on adsorption with an uneven distribution of sites on the adsorbent surface. The Temkin model assumes that adsorption energy decreases linearly with increasing surface coverage [21]. The D-R isotherm model can be used to calculate the average free energy of adsorption and determine the adsorption type. The model is expressed as follows [22, 23]:

Langmuir:

Results and Discussion

Characterization

XRD and FT-IR

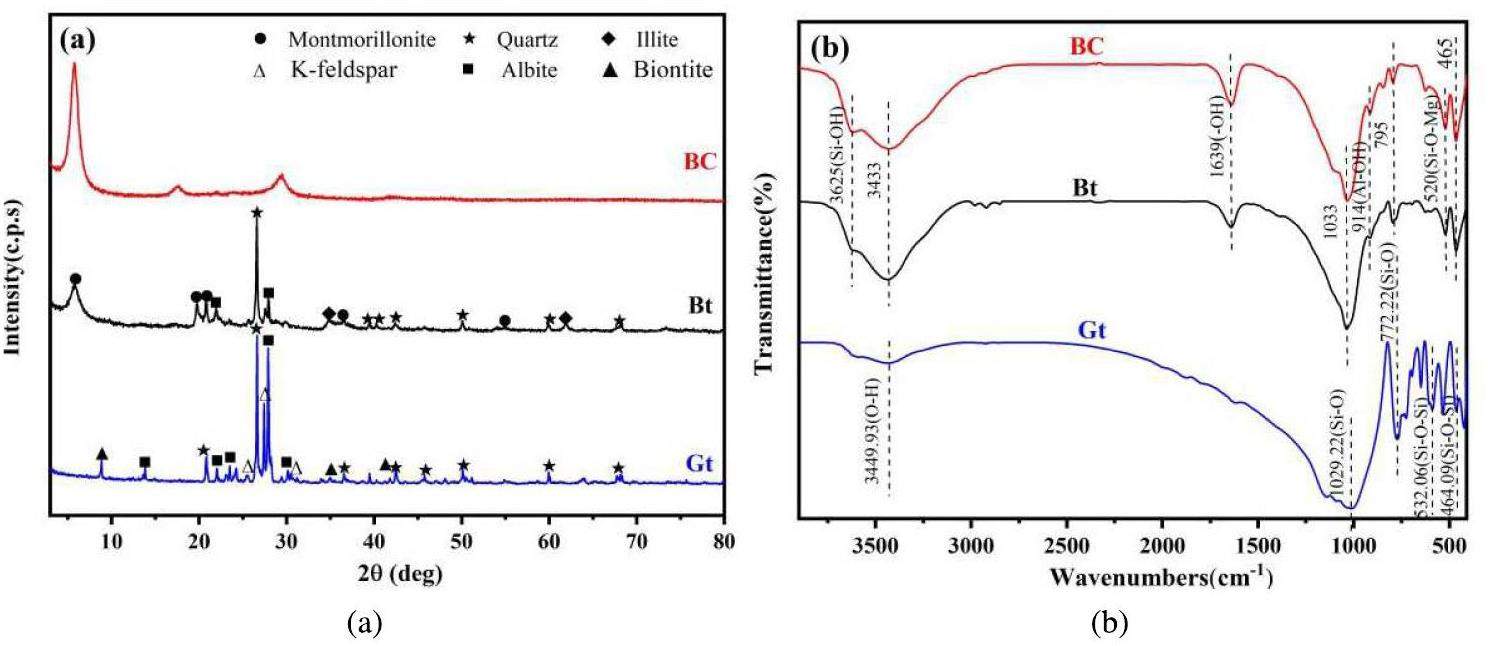

The mineral compositions of the samples were determined by XRD and FT-IR analyses.

Figure 2a shows the XRD patterns of the samples. The predominant mineral components of granite are quartz, albite, potassium feldspar, and biotite, with albite and K-feldspar together constituting approximately 70% of the mass percentage of the granite minerals. Bentonite contains montmorillonite as the main mineral component as well as secondary minerals, such as quartz, illite, and albite (Fig. 2b). The interplanar spacing of the bentonite colloid at the (001) plane differs slightly from that measured for the soil sample (1.52 nm). The diffraction curve of the bentonite colloid contains only a montmorillonite peak, indicating that secondary minerals were removed by centrifugation and dialysis [24]. The FT-IR analysis of the surface functional groups revealed that granite mainly consists of Si- and Al-based functional groups, including O-H, Si-O, Al-O, and Si-O-Si, which are similar to those present in bentonite [25, 26]. The bentonite colloids and bentonite have similar primary functional groups with minimal differences in the corresponding peak shapes and positions in the FT-IR spectra. This suggests that colloid formation has a negligible effect on the surface functional groups and chemical bonds of bentonite.

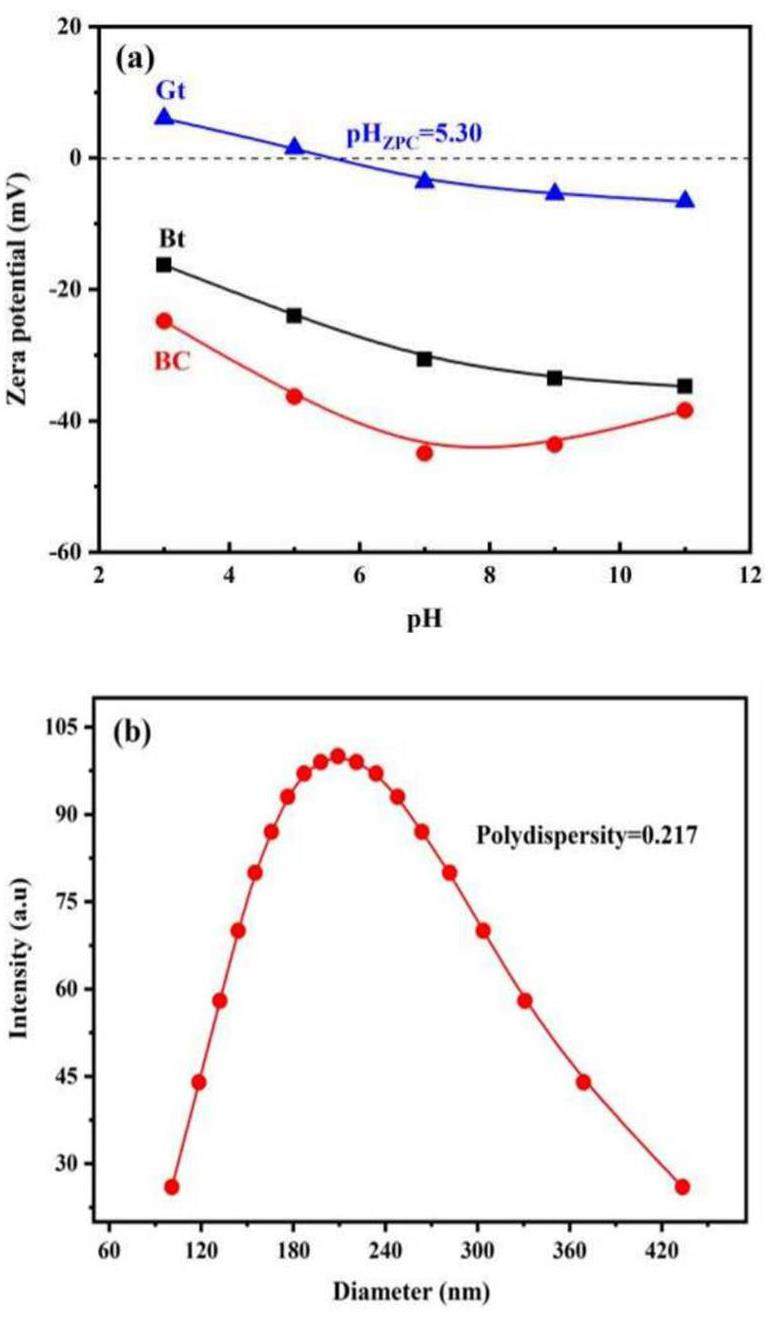

Zeta and particle size distribution

The Zeta potential of the geological materials and bentonite colloids at different pHs is shown in Fig. 3a. Granite reaches the zero-point charge site at a pH of approximately 5.30, whereas bentonite and bentonite colloids have negative zeta potentials across the pH range of 3–11, with the bentonite colloids having a slightly lower potential than bentonite. The negative charge of bentonite arises from both the permanent charge of the structure and variable edge charge [27]. The colloid preparation process can affect the deprotonation of -SiOH and -AlOH, resulting in a bentonite colloid with a slightly lower potential than bentonite. However, the charges of bentonite and bentonite colloids were similar, indicating that the contribution from the edge charge was small. Figure 3b shows the average size and size distribution of the colloidal particles determined by dynamic light scattering. The colloidal particle sizes ranged from 100.9 nm to 433.5 nm with an average of 209.1 nm, suggesting relatively good colloidal stability. The polydispersity index (PDI) is a crucial parameter for characterizing particle size uniformity in a system. The bentonite colloid sample had a PDI of 0.217 in ultrapure water, indicating excellent dispersion.

SEM-EDS before and after adsorption

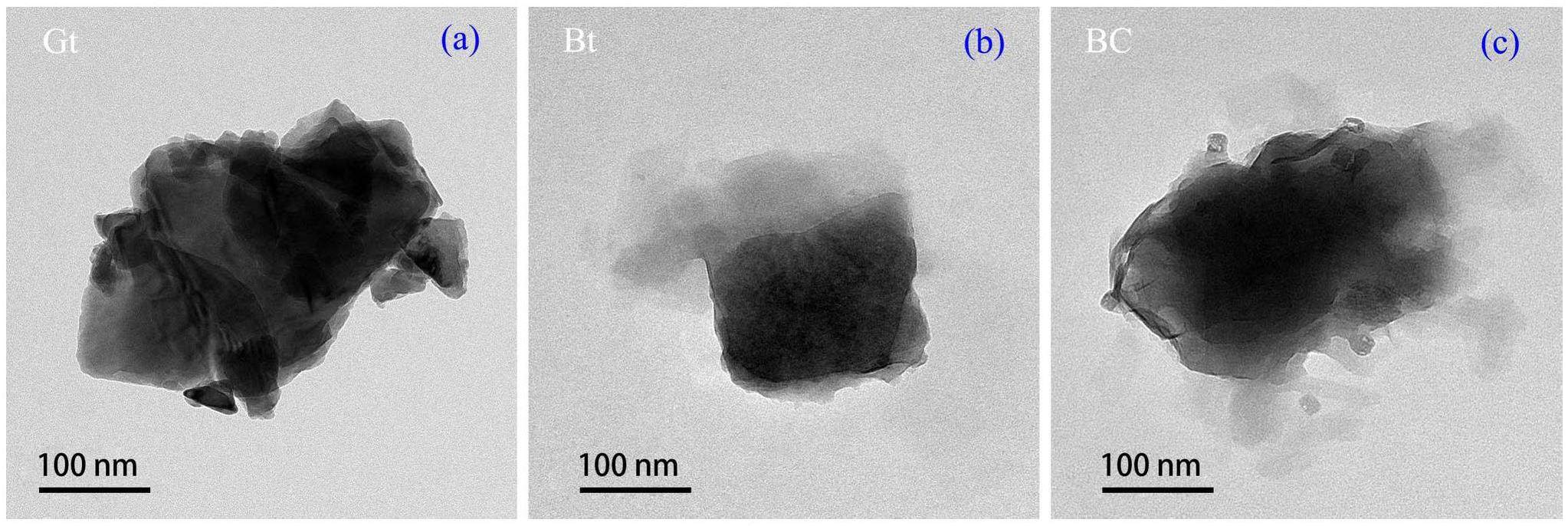

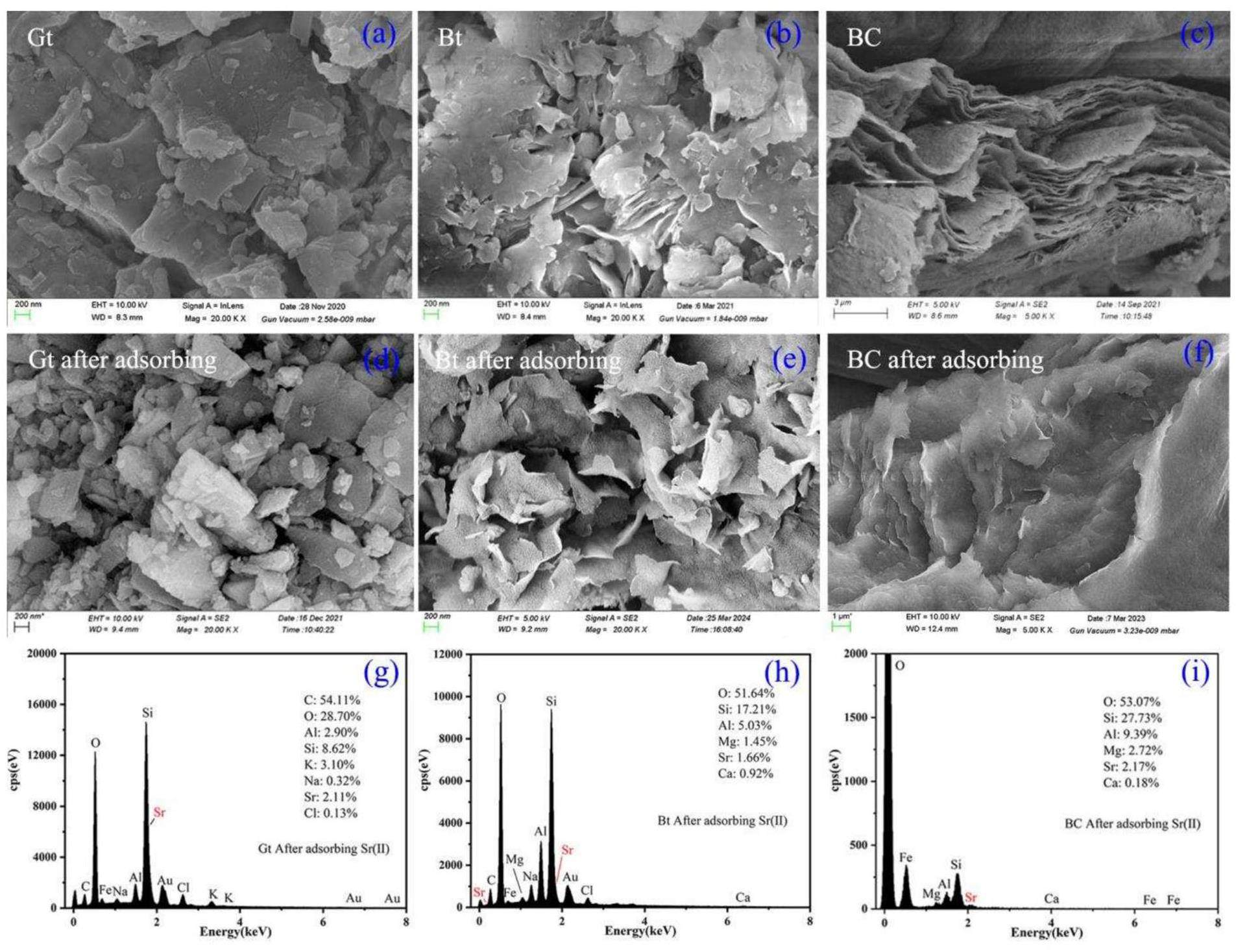

The TEM images of the samples are shown in Fig. 4. Granite exhibits a massive shape with a dense internal texture. Both bentonite and bentonite colloids display similar sheet morphologies with irregular edges, and the layered structure of the colloid is more pronounced, confirming the XRD results. In addition, the TEM diagram illustrates that the prepared bentonite colloid has good dispersion, and the particle size of the colloid is approximately 200 nm, which is consistent with the particle size distribution test results of the colloid.

The surface morphologies of the samples before and after adsorption were characterized by SEM-EDS. Figure 5 shows that the granite samples have a fragmented distribution with unevenly sized layered fragments, and the sample surface is smooth with angular features. There is no significant difference in the morphology of the adsorbed granite before and after adsorption although adsorption makes the surface rougher and more fragmented, possibly because of immersion and agitation. The EDS results for the samples after adsorption indicate an increase in the quantity of adsorbed Sr2+ on the granite surface; however, there is no discernible distribution pattern for Sr2+ or a direct correlation between the distributions of Sr2+ and the other ions. The nonuniform particle size of bentonite indicates a distinct flaky structure with numerous irregular pores and cavities that facilitate the migration and diffusion of nuclides [28]. After adsorption, the bentonite surface curls and becomes rough, presumably because adsorption is followed by drying [29].

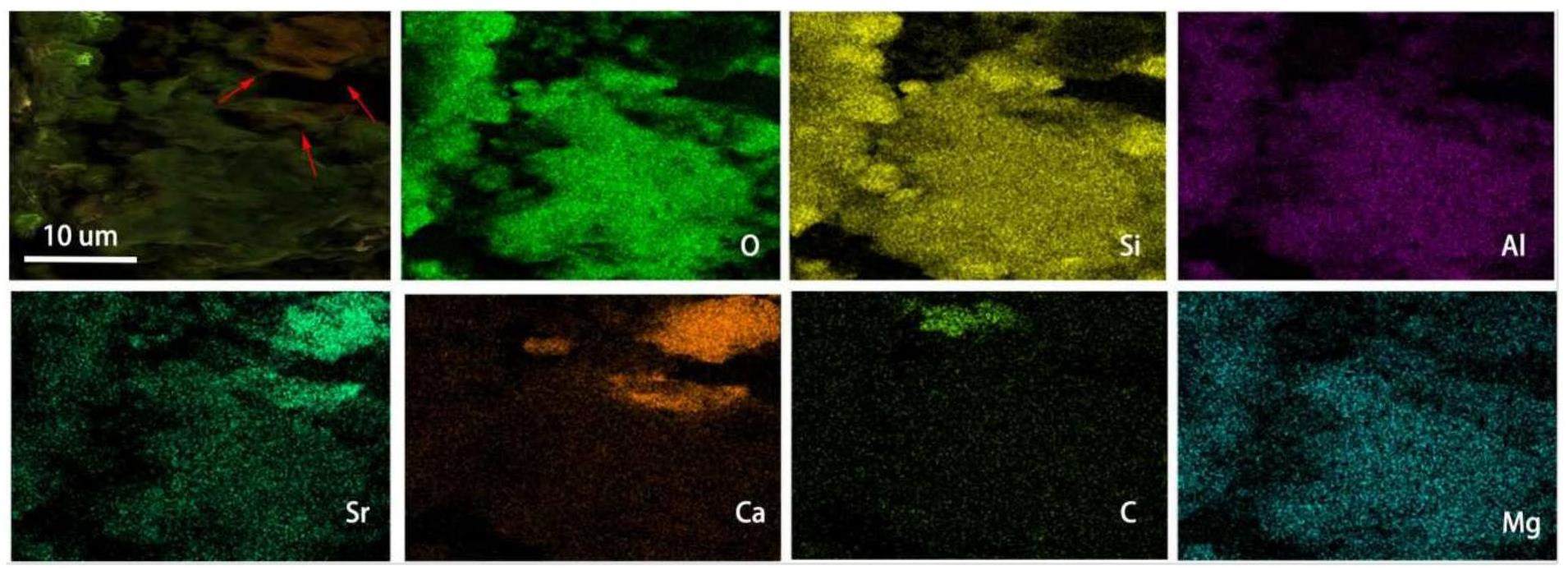

The immersion and dialysis of bentonite generates bentonite colloids with a distinct layered morphology [30] with clearer boundaries and a more regular distribution than that of the soil samples. Adsorption does not change the morphology of the colloids considerably but makes the layered structure denser, more compact, and agglomerated, with less distinct interlayers. The EDS results presented in Fig. 6 show that O, Si, Al, and Mg are still the main elements in the colloidal samples after simulated nuclide adsorption. The Sr2+ ions are adsorbed unevenly on the colloids, mainly accumulating in the layered stacking regions, indicating the presence of different adsorption sites on the colloids, with the stacking edge sites having possibly a stronger affinity for Sr2+ [31]. The distribution of Sr on the colloids appears to be correlated with that of Ca, suggesting that Ca in the colloids might participate in the adsorption of Sr via an ion exchange reaction between Ca and Sr. Bentonite colloids primarily consist of montmorillonite. Missana et al. [32] observed similar phenomena for Sr adsorption onto Na-montmorillonite.

Adsorption behavior of Sr2+

Adsorption kinetics

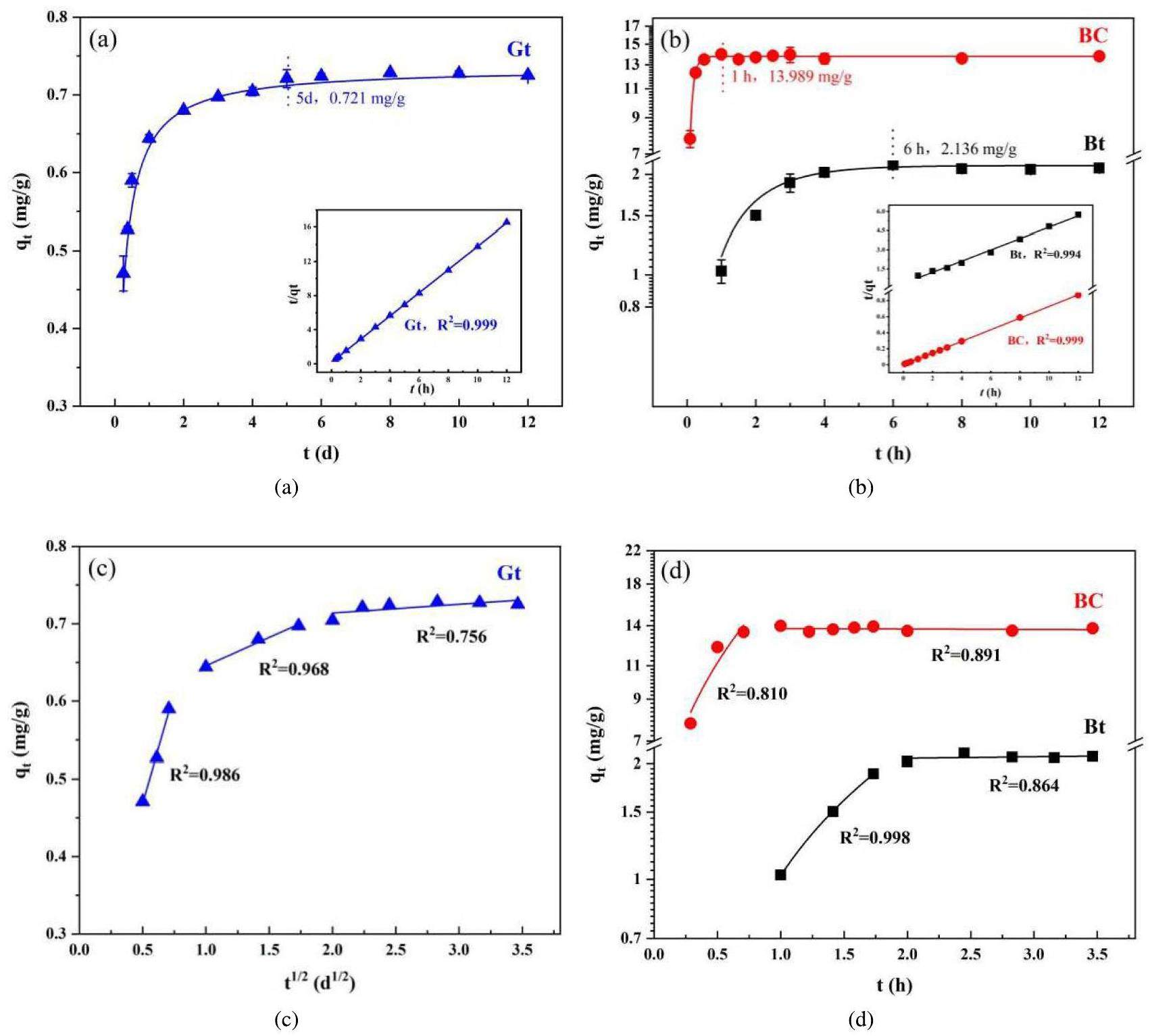

The results of the kinetic experiments are presented in Fig. 7. The adsorption capacities of the three geological materials for Sr2+ are observed to decrease in the order of bentonite colloid (BC) > bentonite (Bt) > granite (Gt). The adsorption equilibrium time for Sr2+ at five days is notably shorter for Gt than for BC and Bt, possibly because of the differences in the number and specificity of surface adsorption sites among the materials. The pseudo-second-order kinetic equation fits the adsorption data for Gt with a high correlation coefficient (R2=0.998), suggesting that Sr2+ adsorption by Gt is primarily chemical [33]. The fitting curve for the Gt data based on the W-M model has three distinct regions corresponding to surface diffusion, internal diffusion, and equilibrium, indicating that intraparticle diffusion is not the sole rate-controlling step for Gt adsorption. In contrast, BC rapidly reaches adsorption equilibrium within 1 h, with qe increasing from 2.136 mg/g to 13.989 mg/g, indicating a considerably greater adsorption capacity than that of Bt. This result is attributed to the larger specific surface area and lower surface charge of BC compared with that of Bt, leading to an increased number of adsorption sites and an enhanced ability to capture Sr2+ ions. Both BC and Bt data were most accurately fitted by pseudo-second-order kinetics, suggesting a chemical adsorption process involving surface complexation between functional groups and ion exchange [34]. Fitting the adsorption data of BC and Bt using the W-M equation revealed a two-stage process, unlike the adsorption on Gt. The fitted BC and Bt curves do not go through the origin, implying that the adsorption of Sr2+ is primarily determined by the adsorption sites and that the activation energy for adsorption and internal diffusion plays a minor role in the process [35]. Overall, the adsorption capacity of bentonite surpassed that of granite, suggesting a potential synergy between the two materials in blocking nuclide diffusion. However, the strong adsorption capabilities of bentonite colloids introduce considerable uncertainty and risk factors for the long-term disposal at repositories.

Effect of nuclide concentrations

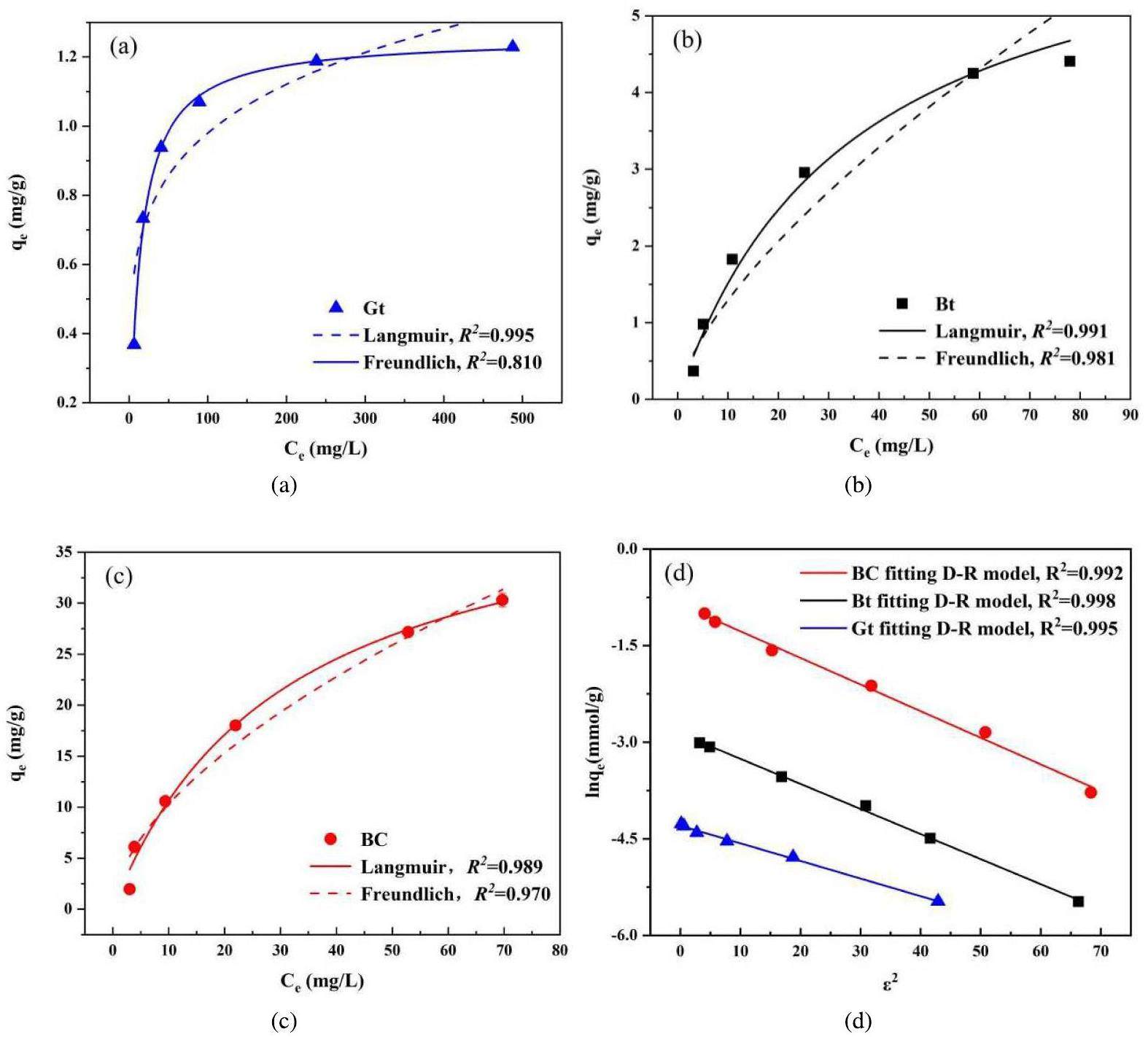

The concentrations of nuclides carried in groundwater fluctuate with natural precipitation and water flow, which can deteriorate the blocking performance of barrier materials. Figure 8 shows that BC has the highest adsorption potential for Sr2+, whereas the adsorption capacities of Gt, Bt, and BC for Sr2+ all increase with the Sr2+ concentration, gradually tending toward equilibrium. This phenomenon may be attributed to the low probability of Sr2+ binding to sites with low Sr2+ concentrations, with the probability increasing with Sr2+ concentration, which facilitates the capture of Sr2+ by adsorption sites. Consequently, the saturation of the binding sites decreases, resulting in a slower increase in the adsorption capacity, leading to gradual equilibrium [36]. To further explore the adsorption mechanism, we used the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and D-R isotherm models to fit the adsorption data at different Sr2+ concentrations (Table 3). Compared with the Freundlich and Temkin models, the fit of the Langmuir adsorption model to the Gt, Bt, and BC data had higher correlation coefficients of 0.996, 0.991, and 0.989, respectively. This indicates that Sr2+ is mainly adsorbed as a surface monolayer [37]. Within the experimental concentration range, the maximum adsorption capacities of Gt, Bt, and BC for Sr2+ were 1.229 mg/g, 4.407 mg/g, and 30.303 mg/g, respectively, and were positively correlated with the specific surface areas of the materials. The fit of the Gt, Bt, and BC data to the Temkin model also showed high linearity, suggesting strong intermolecular interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate [38]. As the Freundlich constant, 1/n, is less than 1, adsorption occurs easily. In the D-R equation, E denotes the energy required for 1 mol of nuclide to react with the adsorbent surface. Table 4 shows that Gt, Bt, and BC have E values above 16 kJ/mol; therefore, the adsorption mechanism of Gt, Bt, and BC is a chemical process [39], which is consistent with the kinetic fitting results.

| Model | Material | Paramaters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order model | Gt | qe=0.708 mg/g | k1=3.838 d-1 | R2=0.914 |

| Bt | qe=2.125 mg/g | k1=0.763 h-1 | R2=0.804 | |

| BC | qe=13.088 mg/g | k1=9.008 h-1 | R2=0.957 | |

| Pseudo-secondorder model | Gt | qe=0.736 mg/g | k2=0.992 g (mg d)-1 | R2=0.998 |

| Bt | qe=2.267 mg/g | k2=0.560 g (mg d)-1 | R2=0.993 | |

| BC | qe=13.761 mg/g | k2=3.941 g (mg d)-1 | R2=0.999 | |

| Weber-Morris model | Gt | kid,1=0.223 mg/g d-1/2 |

C1=0.424 mg/g |

R2=0.986 |

| Bt | kid,1=1.174 mg/g h-1/2 |

C1=-0.151 mg/g |

R2=0.998 |

|

| BC | kid,1=13.671 mg/g h-1/2 |

C1=4.369 mg/g |

R2=0.810 |

| Models | Parameters | Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gt | Bt | BC | ||

| Langmuir | kL | 0.072 | 0.029 | 0.032 |

| qm | 1.257 | 6.750 | 43.360 | |

| R2 | 0.996 | 0.991 | 0.989 | |

| Freundlich | kF | 0.402 | 0.275 | 2.74 |

| 1/n | 0.194 | 0.671 | 0.573 | |

| R2 | 0.810 | 0.981 | 0.970 | |

| Tempkin | kT | 0.1928 | 1.331 | 8.645 |

| f | 1.969 | 0.412 | 0.426 | |

| R2 | 0.901 | 0.986 | 0.987 | |

| D-R | β | 0.0273 | 0.0389 | 0.0385 |

| E | 25.901 | 18.17 | 18.366 | |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.998 | 0.992 | |

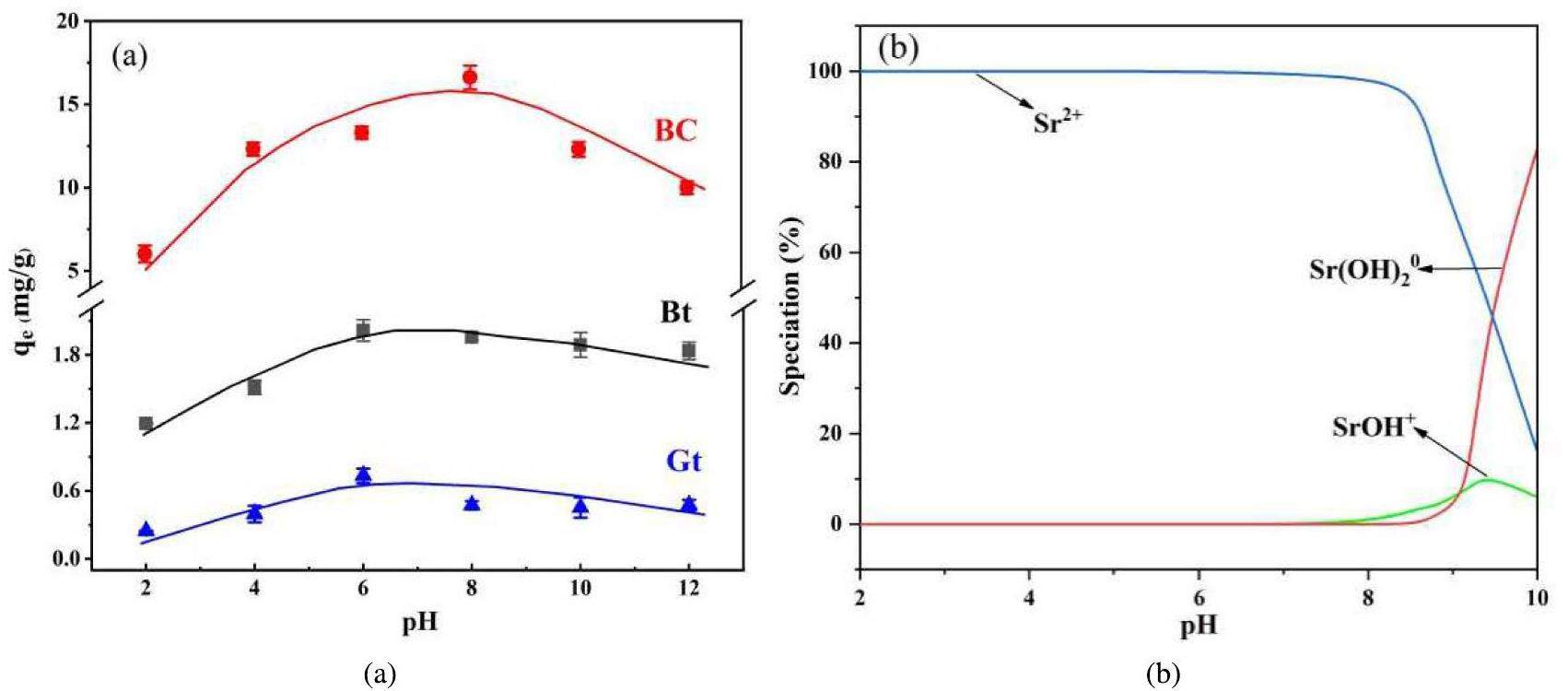

Effect of pH

The pH of the environment strongly influences the mineral surface potential and species distribution of ions, which affects the adsorption of ions on minerals [40, 41]. Figure 9a shows the impact of the pH on Sr2+ adsorption. The adsorption of Sr2+ by Gt, Bt, and BC is impeded by both acidic and alkaline environments. The adsorption capacities of BC, Bt, and Gt peak at pH6 displaying amplitudes of 13.303 mg/g, 2.014 mg/g, and 0.733 mg/g, respectively. This phenomenon may be attributed to the combined effects of the distribution of the strontium species, zeta potential, and colloidal stability. Figure 9b shows that Sr2+ is the primary strontium species under acidic conditions, where the competition between excess H+ and Sr2+ for adsorption sites hinders adsorption [42]. Consequently, adsorption is generally inhibited in acidic environments. As the pH increases, complexes are formed between OH- and Sr2+, such as Sr(OH)+ and Sr(OH)+, which hinder adsorption. Therefore, the adsorption of Gt, Bt, and BC is impeded in alkaline environments. The poor stability of bentonite colloids in acidic environments results in a greater inhibitory effect on BC than on Gt or Bt [43, 44]. Zeta potential affects the affinity of the adsorbent for nuclides. The pHZPC value of Gt is approximately 5.30. At pHs below 5.30, the Gt surface is positively charged, which impedes the adsorption of Sr2+ via electrostatic repulsion. Conversely, at pHs > 5.30, the Gt surface becomes negatively charged, facilitating adsorption. Given that the permanent structural charge of Bt and BC is negative, the zeta potentials of these materials remain negative within the experimental pH range and decrease with increasing pH, indicating that the affinity of Bt and BC for Sr2+ increases with pH. However, this behavior does not alter the inhibition of adsorption by Bt and BC under alkaline conditions. This result can be explained in terms of the minor role that charge attraction plays in adsorption by Bt and BC. The pH of groundwater near disposal facilities is typically approximately 6.70. Around this pH, BC demonstrated high Sr2+ adsorption activity. Therefore, considering the potential effect of colloids on Sr2+ migration during disposal is important.

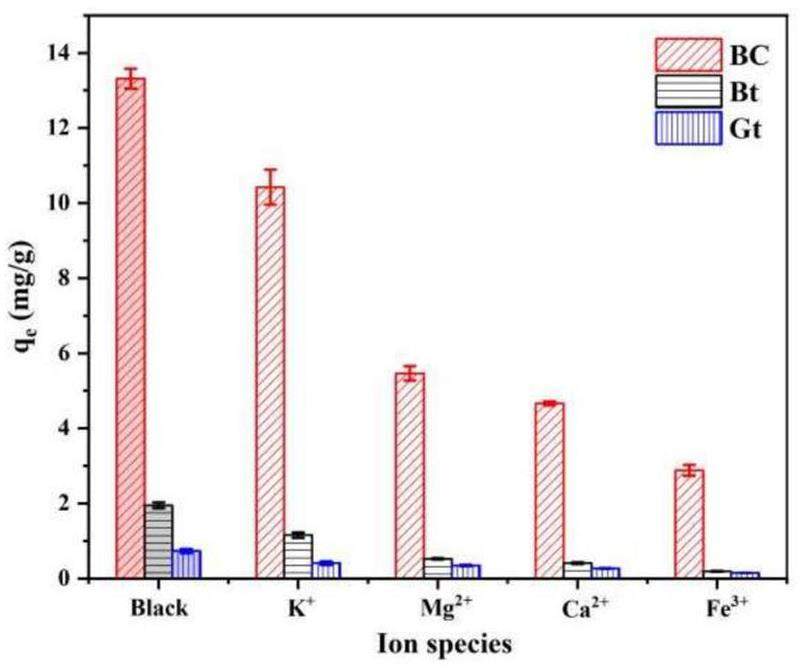

Effect of ions

The complex disposal environment for radioactive waste can result in a groundwater solution containing numerous ions that can affect the adsorption of nuclides by colloids and barrier materials. Preliminary analysis of the groundwater solution showed that the primary anions and cations in the groundwater near the disposal site were

Migration behavior of Sr2+

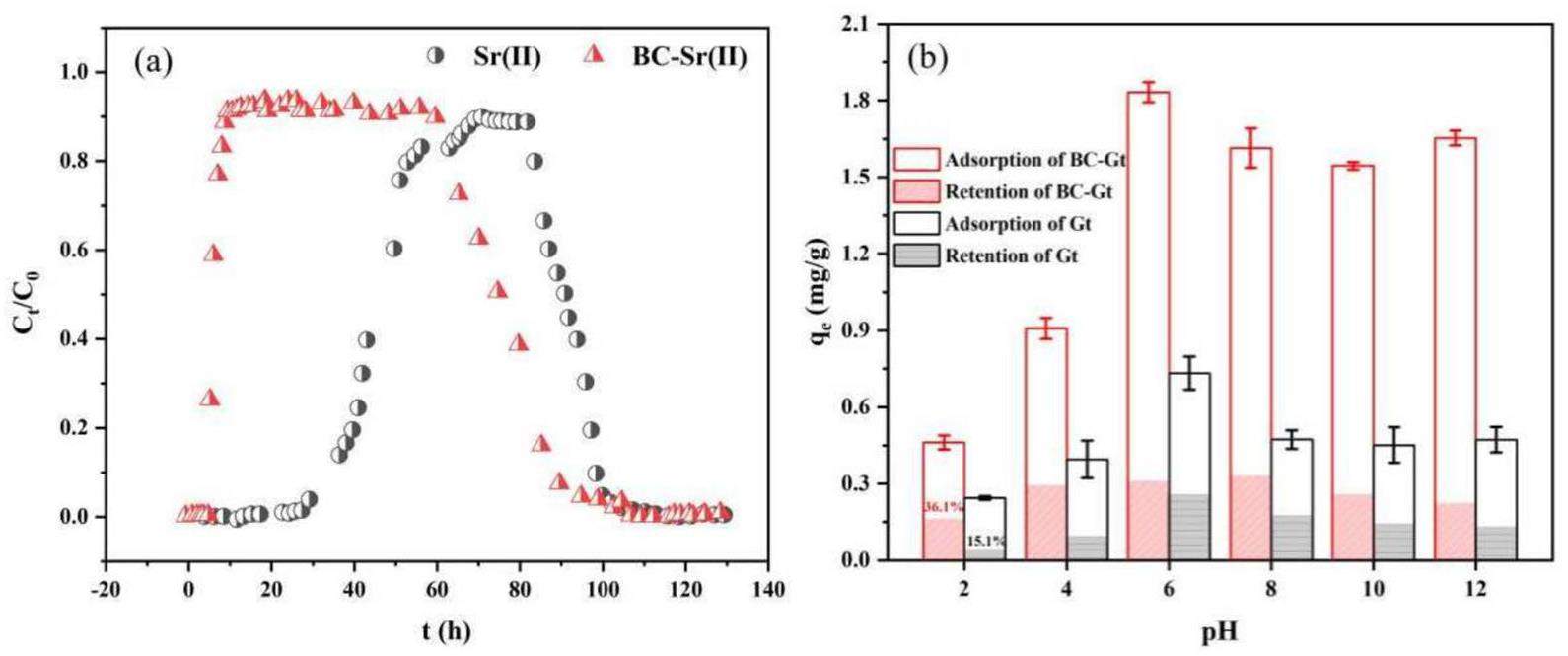

Effect of bentonite colloid on migration

Batch adsorption experiments confirmed the robust adsorption capacity of BC for Sr2+, motivating us to perform dynamic shower experiments to further investigate the influence of BC on Sr2+ migration in the granite system. Figure 11a shows a penetration curve in which neither the peak values of BC-Sr comigration nor Sr migration alone reach 1, indicating retention of Sr2+ in the granite column. The longitudinal dispersion length (DL) measured during Sr-BC comigration was 4.27×10-4. Penetration of the granite column commenced at 18 h, which was considerably shorter than 70 h for Sr migration alone, indicating that the presence of colloids strongly promotes Sr2+ transport. This effect can be attributed to colloidal adsorption and inherent migration. Both bentonite colloids and granite exhibit negative charges across a broad pH range, resulting in repulsion between the colloids and granite during nuclide transport. Static adsorption experiments revealed that the adsorption of Sr2+ by BC is robust, advancing BC as a carrier for accelerating Sr2+ transport. Many studies [30, 45-47] have corroborated that bentonite colloids strongly promote the migration of Em(III), Pu(IV), U(VI), and other nuclides.

Retention of Sr2+ in the granite column was observed in the migration experiments. To investigate the influence of colloids on Sr retention in granite, experiments were conducted on the adsorption/desorption of Sr2+ on BC and Gt. As shown in Fig. 11b, the adsorption results indicate that the BC-Gt system has strong adsorption capacity for Sr2+. Under alkaline conditions, the adsorption capacity of the BC-Gt system is considerably greater than that of the Gt system because the stability of BC is enhanced in an alkaline environment [48]. The desorption experiments revealed that Gt has a lower adsorption capacity for Sr2+, with most sites being reversible [49], which resulted in a low retention rate of (15.1% to 35.6%) for Sr2+ in Gt after desorption, which is consistent with the observations in the migration experiments. The retention of Sr2+ on Gt was slightly higher for the BC-Gt system, which is attributed to the small number of colloids attached to the surface of the granite. Notably, acidic conditions considerably increased Sr2+ retention, which can be attributed to the reduced stability of BC under acidic conditions [50], leading to sedimentation and adhesion with Gt, which weakens desorption. Overall, fractures in granite significantly increase the risk of Sr2+ leakage into the biosphere, and a small amount of colloid adhering to the surface of granite in the repository may slightly enhance the retention of Sr2+ in granite. However, colloid promotion was not observed to have a significant impact on the retention of Sr2+ in granite during dynamic migration experiments. This indicates that the influence of colloids on Sr2+ retention in granite should be considered alongside multiple factors such as flow rate, concentration, and pH, which are crucial for the safety assessment of nuclear waste disposal facilities.

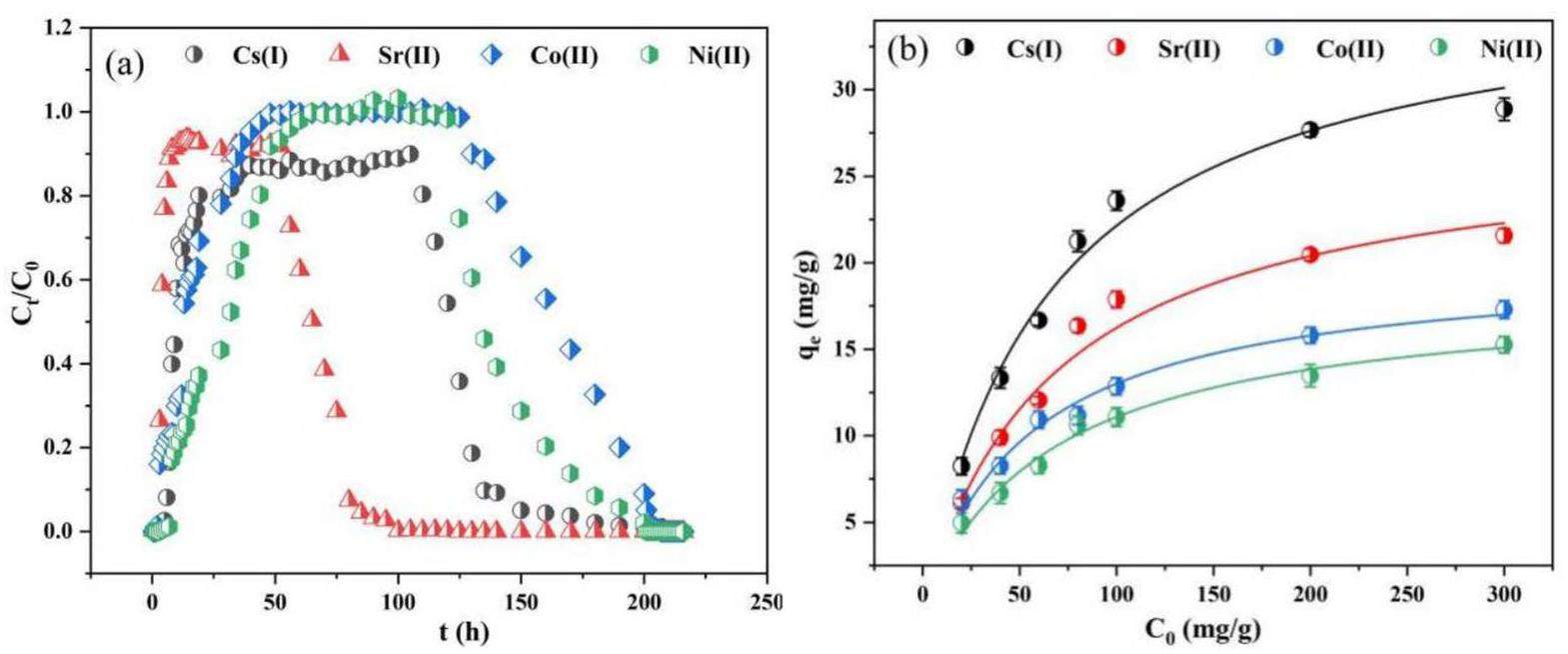

Comigration of Bentonite Colloids and Polynuclides

As shown in Fig. 12b, the adsorption capacity of bentonite colloids for nuclides in multicomponent systems increased in the order of Co2+ < Ni2+ < Sr2+ < Cs+, indicating that BC has the strongest affinity for Cs+ in a multicomponent system. Analysis of the breakthrough curve revealed that the detection time for Sr2+ in the multinuclide comigration system surpassed that of the BC-Sr system. This delay may arise from the interaction between the numerous positively charged ions and bentonite colloids, mitigating electrostatic repulsion and reducing colloidal fluidity to promote bentonite agglomeration. These agglomerates were retained in the column because of size exclusion effects. Similar outcomes have been reported in studies on coexisting ions, in which fluctuations in ion content were attributed to external interference. In particular, the coexistence of ions with the same valence state causes steric hindrance, and filtering exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on colloidal transport [51]. The effluent recovery rate increased in the order Co2+ < Ni2+ < Sr2+ < Cs+ because of the nuclide adsorption capacity of BC. Nuclides adsorbed on BC can be retained in granite columns, diminishing the nuclide recovery rates in the effluent. Differences in affinities and binding capabilities of the colloids and different simulated nuclides resulted in Sr2+ and Cs+ eluting faster than Co2+, which had a more pronounced elution curve. Nuclides with a stronger affinity for BC were affected more during migration. The penetration times of the nuclides in the multielement system increased in the order Sr2+ < Cs+ < Ni2+ < Co2+. Hence, considering the role of bentonite colloids in predicting Sr2+ migration is important in the safety assessment of repositories.

Conclusion

In this study, the impact of bentonite colloids on the migration of Sr2+ in granite was investigated in terms of adsorption capacity by conducting a combination of static adsorption and dynamic shower experiments. The influence of the multinuclide system on the migration of Sr2+ was analyzed. The findings of this study provide fundamental data and rational recommendations for safety assessment and establishment of migration models for nuclear waste disposal facilities. The results of the static adsorption experiments demonstrate that bentonite colloids have a considerably greater Sr2+ adsorption capacity than bentonite and granite, with maximum adsorption rates of 30.303 mg/g, 4.407 mg/g, and 1.2285 mg/g for bentonite colloids, bentonite, and granite, respectively. The adsorption behavior of Sr2+ conformed to both the Langmuir isotherm and pseudo-second-order kinetic models. Fitting the Sr2+ adsorption data with the W-M model revealed a two-stage distribution, indicating that single-layer chemical adsorption is controlled by the site activation energy. The distribution of Sr2+ on the colloid surface is nonuniform, and the mechanism of Sr2+ adsorption may involve ion exchange with Ca. Colloids have an optimal Sr2+ adsorption capacity in neutral environments. However, cations in groundwater inhibit Sr2+ adsorption onto colloids, and the inhibition efficacy decreases in the following order: Fe3+>Ca2+>Mg2+>K+. Colloids maintain substantial adsorption potential even at high Sr2+ concentrations. Dynamic migration experiments revealed that the presence of colloids influence the retention of Sr2+ in granite, which is consistent with the findings of the adsorption/desorption experiments. However, the addition of colloids considerably accelerated the diffusion rate of Sr2+ in granite, reducing the penetration time from 70 h to 18 h. The presence of Co2+, Ni2+, and Cs+ in a multinuclide system diminished the ability of the colloids to promote Sr2+ migration. The effluent recovery rate increased in the order Co2+ < Ni2+ < Sr2+ < Cs+ because of the nuclide adsorption capacity of BC. This result confirms that the stronger the colloidal adsorption capacity for a nuclide, the greater is the impact of the colloids on Sr2+ migration. In conclusion, the presence of colloids increases the risk associated with Sr2+ migration in disposal facilities. Therefore, the influence of colloids on Sr2+ migration must be considered in safety assessments.

Sorption of cesium on surrounding granite of Chinese low- and medium-level nuclear waste repository in the groundwater environment

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 5, 331 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-022-08280-7Recent progress in radionuclides adsorption by bentonite-based materials as ideal adsorbents and buffer/backfill materials

. Appl. Clay. Sci. 232,Investigating the role of Na-bentonite colloids in facilitating Sr transport in granite minerals through column experiments and modeling

. J. Hazard. Mater. 463,Non-thermal plasma irradiated polyaluminum chloride for the heterogeneous adsorption enhancement of Cs+ and Sr2+ in a binary system

. J. Hazard. Mater. 424,Electrokinetics couples with the adsorption of activated carbon-supported hydroxycarbonate green rust that enhances the removal of Sr cations from the stock solution in batch and column

. Sep. Purif. Technol. 265,Comparison of sustainable biosorbents and ion-exchange resins to remove Sr2+ from simulant nuclear wastewater: batch, dynamic and mechanism studies

. Sci. Total. Environ. 650, 2411-2422 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.396Kinetics and irreversibility of cesium and uranium sorption onto bentonite colloids in deep granitic environments

. Appl. Clay Sci. 26(1), 137-150 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2003.09.008Investigating the influence of bentonite colloids on strontium sorption in granite under various hydrogeochemical conditions

. Sci. Total. Environ. 900,Insight into impact of phosphate on the cotransport and corelease of Eu(III)) with bentonite colloids in saturated quartz columns

. J. Hazard. Mater. 461,Interaction between gaomiaozi bentonite colloid and uranium

. Nuclear. Analysis 1(4),Co-transport of chromium(VI) and bentonite colloidal particles in water-saturated porous media: effect of colloid concentration, sand gradation, and flow velocity

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 234,Insight into the stability and correlated transport of kaolinite colloid: effect of pH, electrolytes and humic substances

. Environ. Pollut. 266(2),Results of the colloid and radionuclide retention experiment (CRR) at the grimsel test site (GTS), switzerland - impact of reaction kinetics and speciation on radionuclide migration

. Radiochim. Acta. 92(9), 765-774 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1524/ract.92.9.765.54973137Cs transport in crushed granitic rock: The effect of bentonite colloids

. Appl. Geochem. 96, 55-61 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129636Gaomiaozi bentonite colloids: interactions with plutonium (IV) and zirconium (IV)

. Colloid. Surface. A. 650,Neptunium(V) transport in granitic rock: a laboratory scale study on the influence of bentonite colloids

. Appl. Geochem. 103, 31-39 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.07.001Laboratory investigation of the role of desorption kinetics on americium transport associated with bentonite colloids

. J. Environ. Radioact. 148, 170-182 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/00295450.2022.2083749Adsorption Properties of Cs(I) and Co(II) on GMZ Bentonite Colloids

. Nucl. Technol. 208(12), 1894-1907 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/00295450.2022.2083749Adsorption of strontium at K-feldspar-water interface

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 181,Nonthermal plasma-irradiated polyvalent ferromanganese binary hydro(oxide) for the removal of uranyl ions from wastewater

. Environ. Res. 217,Synthesis of activated carbon from lemna minor plant and magnetized with iron (III) oxide magnetic nanoparticles and its application in the removal of ciprofloxacin

. Biomass. Convers. Bior. 14(1), 649-662 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-021-02279-yEnhanced adsorption of phenol using graphene oxide-bentonite nanocomposites: synthesis, characterisation, and optimisation

. J. Mol. Liq. 395,Enhancement of the heterogeneous adsorption and incorporation of uraniumvi caused by the intercalation of β-cyclodextrin into the green rust

. Environ. Pollut. 290,Influence of experimental procedure on d-spacing measurement by XRD of montmorillonite clay pastes containing pce-based superplasticizer

. Cem. Concr. Res. 116, 266 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.11.015Adsorption behaviors of Eu(III) on granite: batch, electron probe micro-analysis and modeling studies

. Environ. Earth Sci. 78(8), 1-9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-019-8170-yThe sorption interactions of humic acid onto beishan granite

. Colloid. Surface. A. 484, 37-46 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2015.07.045Kinetic determination of sedimentation for GMZ bentonite colloids in aqueous solution: Effect of pH, temperature and electrolyte concentration

. Appl. Clay. Sci. 184,Adsorption characteristics of strontium by bentonite colloids acting on claystone of candidate high-level radioactive waste geological disposalsites

. Environ. Res. 213,Effects of bentonite heating on U(VI) adsorption

. Appl. Geochem. 109,Montmorillonite colloids: II. Dependence of colloidal size on radionuclide adsorption

. Appl. Clay Sci. 123, 292-303 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2016.01.017Montmorillonite colloids: I. characterization and stability of dispersions with different size fractions

. Clay. Sci. 114, 179-189 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2015.05.028Adsorption of bivalent ions (Ca(II), Sr(II), and Co(II)) onto febex bentonite

. Phys. Chem. Earth. 32(8), 559-567 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2006.02.052Graphene oxide-modified organic gaomiaozi bentonite for Yb(III) adsorption from aqueous solutions

. Mater. Chem. Phys. 274,removal of u(vi) and humic acid on defective TiO2-X investigated by batch and spectroscopy techniques

. Chem. Eng. 325, 576-587 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.05.125Adsorption kinetic, thermodynamic and desorption studies of Th(IV) on oxidized multi-wall carbon nanotubes

. Colloid. Surface. A. 302, 449-454 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2007.03.007Insights into the removal of lithium and molybdenum from groundwater by adsorption onto activated carbon, bentonite, roasted date pits, and modified-roasted date pits

. Bioresource Technology Reports. 18,Effect of direct yellow 50 removal from an aqueous solution using nano bentonite; Adsorption isotherm, kinetic analysis, and thermodynamic behavior

. Arab. J. Chem. 16(2),Efficient adsorption of tetracycline from aqueous solution using copper and zinc oxides modified porous boron nitride adsorbent

. Colloids Surfaces. A. 666,Tetracycline and sulfamethoxazole adsorption onto nanomagnetic walnut shell-rice husk: isotherm, kinetic, mechanistic, and thermodynamic studies

. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 100, 1-23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2019.1646739https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2019.1646739Uptake of 137Cs and 85Sr into thermally treated bentonite

. J. Environ. Radioact. 193, 36-43 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2018.08.015A comprehensive investigation of zeolite-rich tuff functionalized with 3-mercaptopropionic acid intercalated green rust for the efficient remval of Hg(II) and Cr(VI) in a binary system

. J. Environ. Manage. 324,Sorption of sr in granite under typical colloidal action

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 233,Colloidal behavior of aqueous montmorillonite suspensions: Specific role of pH in the presence of different electrolytes

. Appl. Clay. Sci. 27(1/2), 79-95 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2004.01.001Colloidal stability of bentonite clay considering surface charge properties as a function of pH and ionic strength

. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 16(5), 837-841 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2010.05.002Fate and cotransport of Pb(II) and Cd(II) heavy ions with bentonite colloidal flow in saturated porous media: The role of filter cake, counterions, colloid concentration, and fluid velocity

. J. Hazard. Mater. 466,Uranium and cesium sorption to bentonite colloids under carbonate-rich environments: Implications for radionuclide transport

. Sci. Total Environ. 643, 260-269 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.162Bentonite colloids mediated Eu(III) migration in homogeneous and heterogeneous media of Beishan granite and fracture-filling materials

. Sci. Total. Environ. 904,Sorption behavior of U(VI) onto chinese bentonite: Effect of pH, ionic strength, temperature and humic acid

. J. Mol. Liq. 188, 178-185 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2013.10.008Sorption and desorption of Sr onto a rough single fractured granite

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 228,Stability of GMZ bentonite colloids: Aggregation kinetic and reversibility study

. Appl. Clay Sci. 161, 436-443 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2018.05.002Competitive removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions by montmorillonitic and calcareous clays

. Water. Air. Soil. Pollut. 223, 1191-1204 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-011-0937-zThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.