Introduction

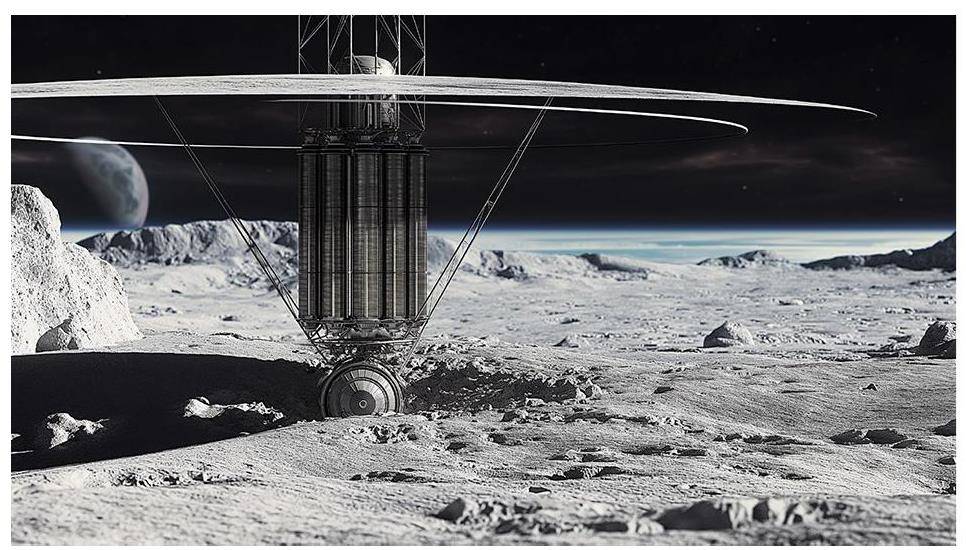

As the demand for advanced extra-terrestrial exploration voyages intensifies, the limitations imposed by solar and chemical energy sources become increasingly evident in the context of cosmic frontier exploration. Nuclear energy offers a sustained power supply, extending from the lunar to even the expanse of remote celestial bodies, thereby catering to the diverse requisites of space missions, including, but not limited to, the establishment of enduring outposts (Fig. 1). Owing to its extended lifespan, exceptional energy quantum, and steadfast operational efficacy, the Space Nuclear Reactor Power System (SNRPS) [1] is an ideal choice for executing interstellar missions. Power prerequisites encompass various tasks [2, 3] of cosmic exploration, such as deep-space voyages, orbital space stations, and planetary surface infrastructures, within the range of 10––1000 kW [4, 5]. For such space-bound expeditions, a power conversion system with a lengthy serviceable life, high dependability, and substantial power density is pivotal. A heat-pipe-cooled reactor [6-11] is an innovative nuclear apparatus that harnesses heat pipes to transfer the reactor’s core heat directly to its secondary system. The Stirling engine, crafted by the ingenious British engineer Robert Stirling in 1816 [12], offers numerous benefits, including adaptability to virtually all energy sources, diminished noise levels, and indifference to pressure fluctuations. Recently, there have been notable advances in the fabrication of kilowatt-scale SNRPS that amalgamate Stirling engines with heat pipe-cooled reactors [13-16]. The Stirling cycle can theoretically achieve a relatively high thermodynamic-to-electrical conversion efficiency, ranging from 20% to 40%[17]. Hence, the integration of heat pipe-cooled reactors with Stirling engines has been actively pursued as an area of research. The United States has harnessed the principles of the Stirling cycle in the conceptualization and design of a diverse array of kilowatt-scale heat pipe fission reactors, such as the Heat Pipe Mars Exploration Reactor (HOMER)[18] and the Kilowatt Reactor Using Stirling Technology (KRUSTY) [19-21]. In March 2018, KRUSTY, successfully operated as a fission power system, emerged as the first nuclear-powered operation of a truly new reactor concept in the United States over the past 40 years [22]. The performance of the Stirling engine significantly influences the thermal output of the reactor; therefore, analyzing its operational characteristics is essential. The Stirling cycle thermodynamic model is widely used to describe and predict the processes and thermal performance of the Stirling cycle. Ideally, the Stirling cycle consists of two isothermal and two constant-capacity processes, and the thermal conversion efficiency is comparable to that of the Carnot cycle. Nonetheless, in practical terms, various energy-dissipation demand considerations are of paramount importance for constructing an accurate thermodynamic model.

Martini [23]classified the Stirling analytical models into zero-, first-, second-, third-, and fourth-order models. Zero-order analysis employs empirical relationships derived by fitting a substantial volume of experimental data, facilitating quick and straightforward calculations of the power output and efficiency of the Stirling engine. This methodology, represented by the Beale number method [24], can be beneficial for the qualitative examination of the engine. The first-order analysis of the Stirling cycle incorporates an extensively idealized model utilizing variables, such as the temperatures of the cold and hot sources, pressure, rotational velocity, piston diameter, and piston stroke. It predicts the output work and cycle efficiency of a Stirling engine based on the conservation of energy between the working spaces. Schmidt’s analysis method [24] is a typical example of a first-order analysis method in which the entire engine is integrated into three spatial segments (dead space, expansion space, and compression space). Herein, the prevailing temperatures were assumed to remain constant, which is often referred to as isothermal analysis. However, the exceedingly ideal nature of this analysis results in calculations that deviate significantly from those of real-world Stirling engines. In contrast, the second-order Stirling analysis model accounts for potential power losses and heat dissipation, rendering more precise results and widespread application in Stirling cycle period analyses. Nevertheless, traditional second-order methods exhibit a discrepancy of approximately 30–40% between calculated and experimental cycle efficiency values [24]. To refine prediction accuracy, numerous studies have aimed to optimize the second-order analysis model. Sayyaadi et al. combined finite-speed thermodynamics with multiple losses and proposed Simple II [25] and CAFS [26] models that reduced the error between the simulated and experimental values of cycle efficiency to approximately 6.1%-18.7%. Based on the ideal adiabatic model, Ni et al.[27] considered heat losses, such as incomplete regeneration losses in the regenerator, and power losses, such as flow resistance losses, and developed an ISAM model. The error between the simulated and experimental values of the cycle efficiency was reduced to approximately 9.8%–19.9%. Third-order Stirling analysis models [28-30] divide the engine into multiple nodes in the mainstream direction, solving the partial differential equations governing mass, momentum, and energy conservation at each node. These models achieve higher computational accuracy in calculating the heat transfer and output power. However, their calculation speed is significantly slower compared to second-order models. The fourth-order analysis method, also known as the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) method [31-33], provides the highest level of accuracy but imposes substantial demands on computational resources, making system-level analysis challenging. Considering the need to balance precision and computational efficiency for the development of the thermoelectric conversion module in the heat pipe-cooled reactor system analysis code, this study adopted a second-order analysis methodology to advance the Stirling analysis model.

This study proposes refining the simple analysis method by incorporating additional loss terms into the loss module, as observed in models such as Simple-II, CAFS, and ISAM. These additional losses include conductive heat loss, shuttle loss of the displacer piston, leakage loss, finite-speed loss of the piston, and mechanical friction loss.

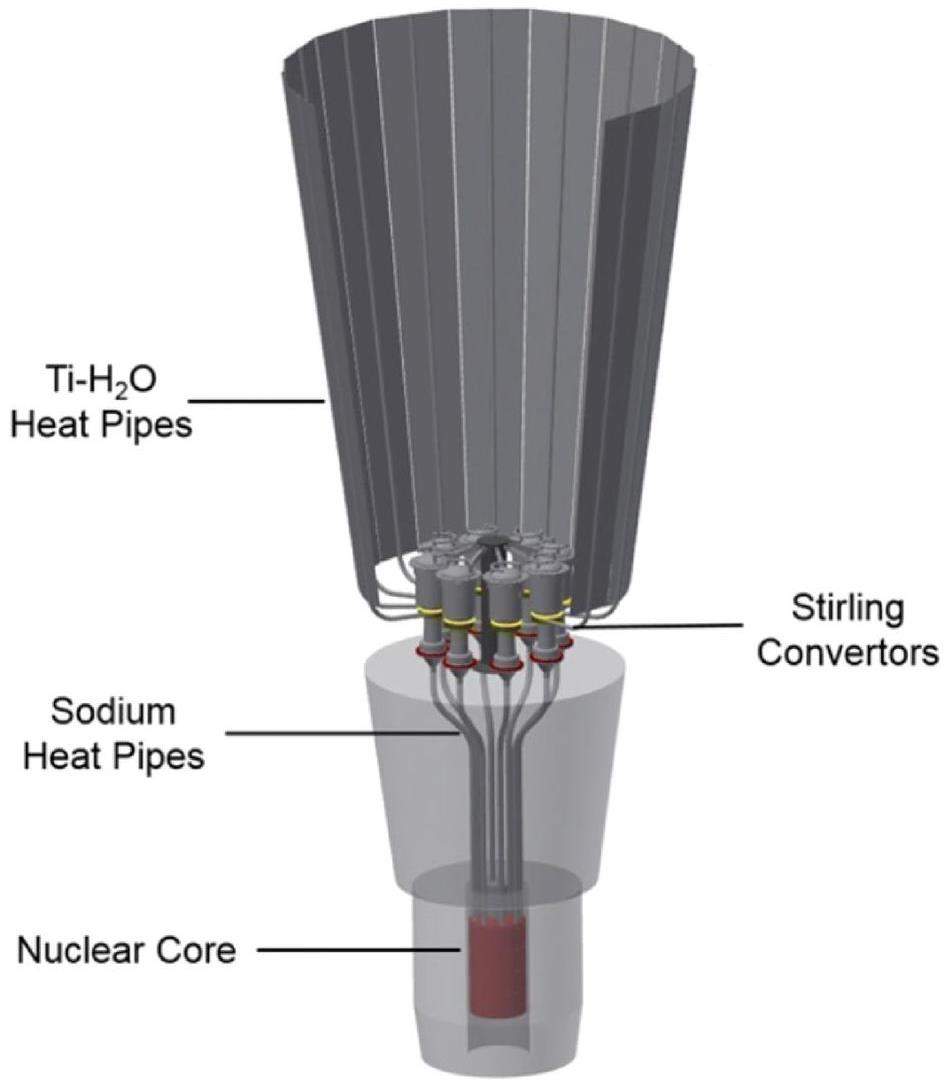

Figure 2 shows a typical space reactor system coupled with a Stirling engine [34]. The free-piston Stirling engine is currently regarded as the most suitable option for kilowatt-scale space nuclear power systems. In contrast, the use of the GPU-3 engine in this context is generally considered inappropriate. Nevertheless, the GPU-3, a well-known beta-type Stirling engine, remains a prevalent research model among scholars and research institutions for academic investigations. As early as the previous century, NASA conducted extensive testing to verify the efficiency and reliability of this engine. Yang et al. [15] proposed a dynamic model of a lunar surface nuclear power system, incorporating a secondary Stirling cycle analysis methodology with the GPU-3 Stirling engine. Their study examined the transient response of the reactor under varying operational conditions and a range of space environmental temperatures.

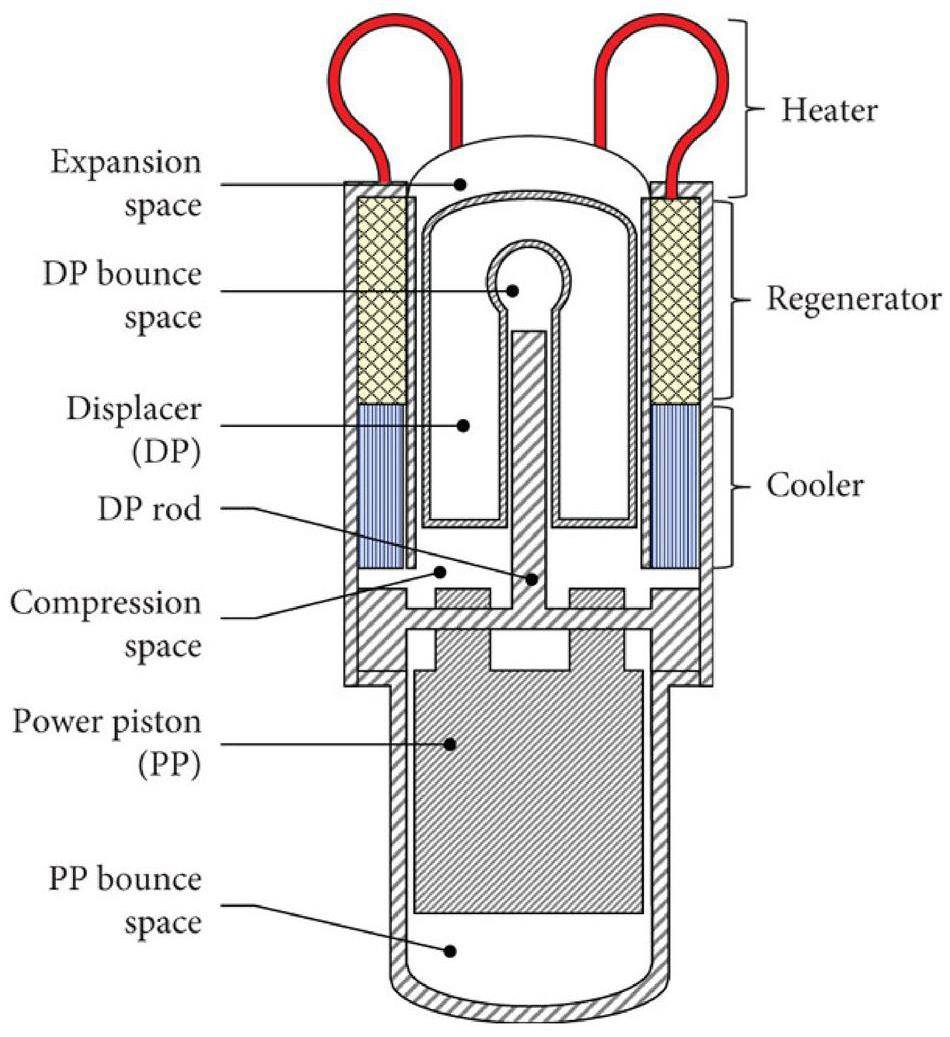

The accuracy of the proposed model was validated against various second-order analysis models and experimental data from GPU-3 (Fig. 3) and the free-piston Stirling engine RE-1000 (Fig. 4) [35, 36]. The results demonstrated that the model is suitable for simulating both beta- and free-piston Stirling engines. The calculation of the average pressure incorporates an iterative pressure convergence method, which enables the rapid convergence of the average pressure. Based on the developed model, an appraisal of the operational characteristics of Stirling engines was undertaken. This study simulated Stirling cycles using hydrogen and helium as working media under varying pressures and rotational velocities to investigate how their distinct thermophysical properties affect engine performance. Moreover, this study probes the effect of regenerator parameters such as porosity, mesh diameter, and axial length of the regenerator on the output work and cycle efficiency at different rotational speeds and suggests optimization directions for these parameters based on the simulation outcomes. Given that the heater and cooler of a Stirling engine are in direct contact with the heat source and cold sink, any changes in the temperatures of these sources directly alter the temperatures of the heater and cooler, thereby affecting the performance of the engine. Stirling cycles were simulated at various temperature ratios to examine the consequences of temperature differentials at the hot and cold ends.

Stirling Model

Adiabatic modeling

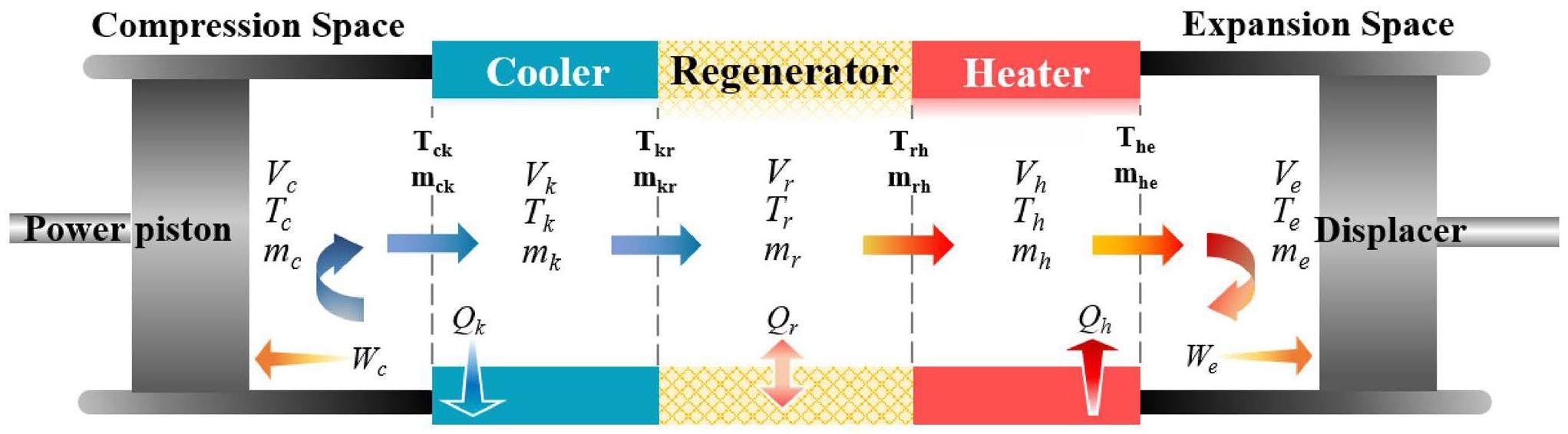

Models based on oscillatory flow characteristics without pressure gradients are widely used for Stirling cycle characterization. The Stirling engine is divided into five chambers (as shown in Fig. 5), namely, expansion space, heater, regenerator, cooler, and compression space. The second-order analysis method is based on the ideal cycle, where the mass and energy conservation equations and the gas equation of the state of each chamber are solved to obtain an analytical solution. This approach allows further calculation of the various power losses and heat losses, yielding the output power and the required heat that are closer to the actual situation. During the development of the ideal adiabatic model, the following assumptions were made.

(1) The working fluid was assumed to be an ideal gas.

(2) There was no leakage of the working fluid in the cycle, and its mass remained constant.

(3) The temperatures of the working gas in the cooler and heater were considered to be equal to the wall temperature and were held constant.

(4) Instantaneous pressures throughout the system are equal.

(5) The heat leakage between the compression and expansion spaces and the heat transfer to the environment are negligible.

(6) The kinetic and potential energies of the gas flow are ignored.

The adiabatic model differential equation set is presented in Table 1, where the subscripts c, k, r, h, and e represent the compression cavity, cooler, return heaters, heaters, and expansion cavity, respectively. The subscripts ck, kr, rh, and he represent the four interfaces of the following five components: compression, cooler, heat return, heater, and expansion spaces, respectively.

| Pressure | |

| mc=pVc/RTc | Mass |

| mk=pVk/RTk | |

| mr=pVr/RTr | |

| mh=pVh/RTh | |

| me=pVe/RTe | |

| Mass flow | |

| Tkr=Tk | |

| Trh=Th | |

| Conditional | |

| temperature | |

| Temperature | |

| Energy | |

Modification of the Adiabatic Model

The simple analysis method considers only the effects of non-ideal heat transfer and pressure loss in the heat exchanger. In this study, based on a simple analysis method, the mass leakage loss term and distribution piston shuttle loss are coupled in the energy conservation equation.

(1)Shuttle heat loss. The shuttle loss is primarily caused by the reciprocating movement of the displacer piston between the hot and cold cylinders. There was a significant temperature gradient at both ends of the displacer piston, leading to heat loss, because some of the heat was directly conducted to the cold end through the piston. The differential expression for this phenomenon is expressed as follows:

Calculation and validation

Calculation process

(2)Seal leakage loss. In the actual operation of the engine, a certain pressure difference emerges between the compression space and the buffer space, which leads to a portion of the gas passing through the gap between the piston and cylinder wall in the compression space and the buffer space back and forth, resulting in leakage losses. The leakage into the buffer space is calculated as follows:

By coupling the shuttle and leakage losses with the differential equations in the adiabatic analysis method, the pressure and pressure differential terms are changed to

Non-idea heat transfer

The heat recovery performance of the Stirling engine was evaluated based on the efficiency of the regenerators. The efficiency of the regenerator is defined as the ratio of the actual enthalpy change to the maximum enthalpy change of the working fluid in the regenerator. When the gas flowed from the cooler to the heater, the temperature at which it exited the return heater was slightly lower than that of the heater. The gas absorbs more heat from the heater (external heat source), resulting in a less efficient heat cycle. Thus, the actual heat absorption and heat release can be written as follows:

Other losses effects

(1)Thermal conductivity loss: The regenerator was connected to the cooler and heater, and the heat from the hot end flowed through the cylinder wall of the return heaters to the cold end, which was the main source of heat conduction loss. This can be evaluated using Fourier’s law[37]:

(2) Flow-resistance loss. Pressure loss is caused by friction owing to the viscosity of the fluid, and the loss caused by the pressure drop is known as flow resistance loss. The multilayered annular mesh structure within the regenerator is the primary cause of the flow resistance loss. The pressure drop and flow resistance loss can be calculated using the following semi-empirical formulas:

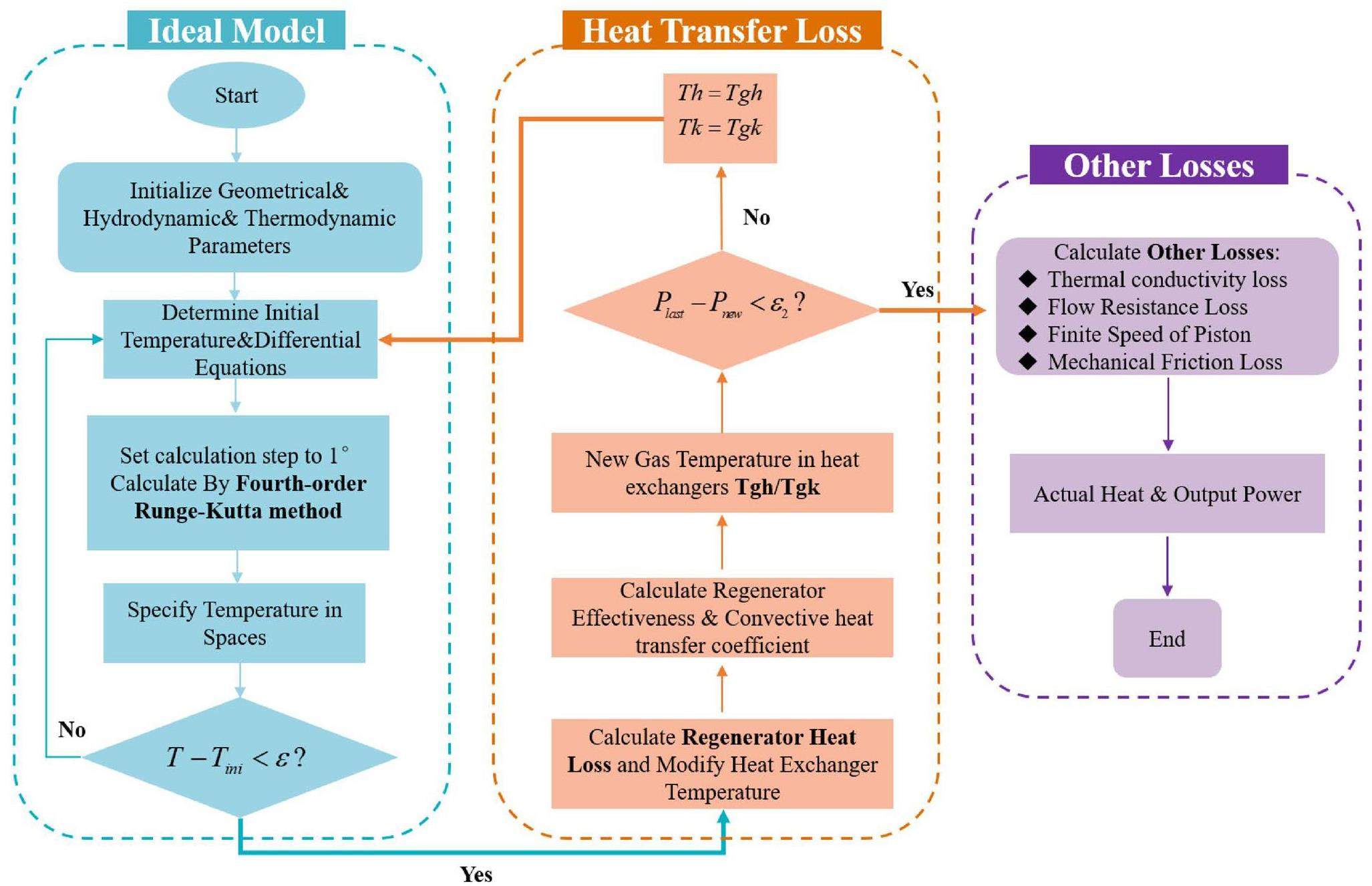

The algorithm of the model used in this study is shown in Fig. 6. In the first step, the Stirling engine geometry and hydrodynamic and thermodynamic parameters were initialized. The geometric equations for Vc, Ve, dVc and dVe as functions of the rotation angle were obtained from the engine configuration. Hydrodynamic parameters, such as the cross-sectional area, wet area, and hydraulic diameter. based on the geometric parameters. Initialize the thermodynamic parameters, such as the specific heat capacity, gas constant, and thermal conductivity.

Second, the computational parameters are initialized. The temperatures of the expansion and compression spaces were initialized to wall temperatures Twh and Twk. The initial mass is computed using the following first-order model:

Third, initialize angle θ as 0 and the calculation step is set to 1. The angle is initialized at the end of each cycle, and for the initial value problem, the system of differential equations is solved using the fourth-order Runge–Kutta method with θ=360 to complete the calculation of one cycle. It is determined whether the cavity temperature at the end of the cycle is equal to the temperature at the beginning of the cycle until the gas temperature approaches the limit of convergence to turn on the next step of the calculation.

The regeneration efficiency of the regenerator and convection heat transfer coefficients of the heater and cooler are described in detail in [24]. The actual heat exchange quantity between the heat exchanger wall and the working fluid is derived based on the ideal heat exchange amount obtained from the previous step. The new temperature of the heat exchanger is computed and used as the initial value to return to the third step of the ideal adiabatic model for calculation. This process is repeated until the convergence criteria are met and then proceeds to the fifth step of the calculation.

Finally, other losses were calculated to obtain the actual heat and output work. The method for solving The classical fourth-order Runge–Kutta method is solved as follows:

Average pressure convergence

In this study, an iterative method was applied for pressure convergence. While solving the Stirling cycle, the average pressure must be calculated to satisfy the condition of average pressure convergence. The average pressure in the compression space over one cycle should be equal to the set average pressure.

Verification and validation

Validation of the GPU-3 Engine

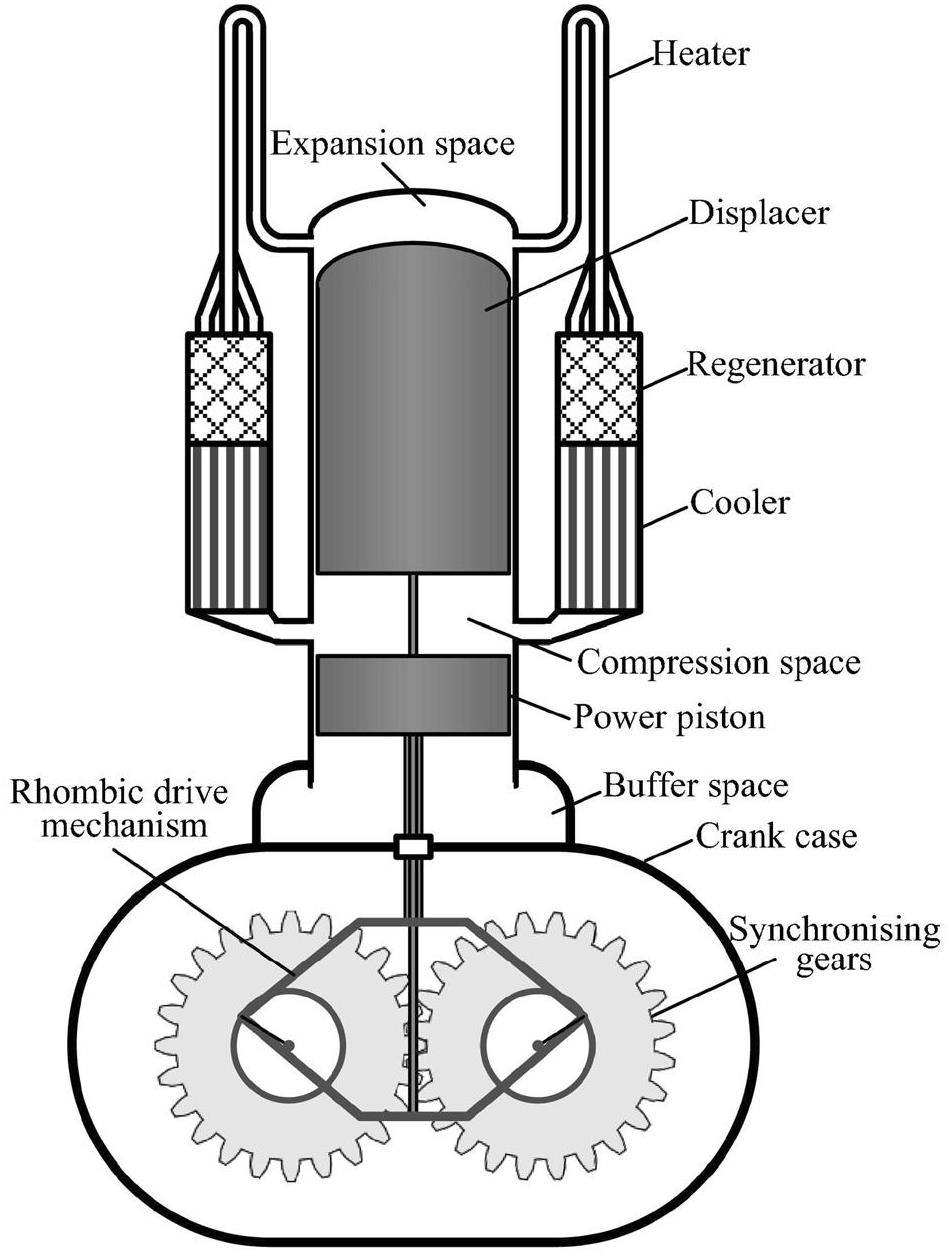

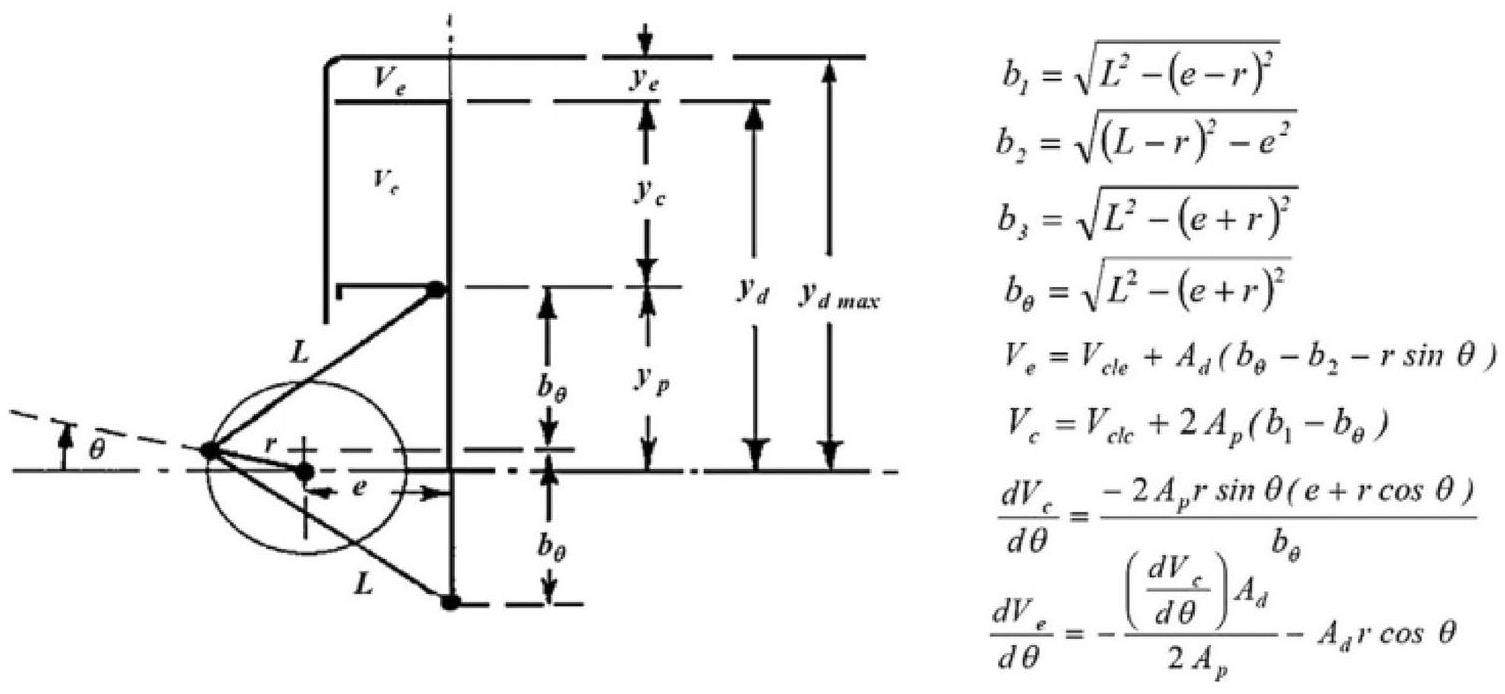

The GPU-3[23, 39] Stirling engine, a portable generator set developed by General Motors for the military sector, has well-established equations of motion for the rhombic drive mechanism to calculate the expansion and compression space volume changes, as shown in Fig. 7. The detailed design dimensions and parameters of GPU-3 are presented in Table 2.

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clearance volumes | Swept volumes | |||

| Compression space | 28.68 cm3 | Compression space | 113.14 cm3 | |

| Expansion space | 30.52 cm3 | Expansion space | 120.82 cm3 | |

| Heater | Cooler | |||

| Tube number | 40 | Tube number | 312 | |

| Tube inside diameter | 3.02 mm | Tube inside diameter | 1.08 mm | |

| Tube length | 245.3 mm | Tube length | 46.1 mm | |

| Void volume | 70.38 cm3 | Void volume | 13.8 cm3 | |

| Regenerator | Drive | |||

| Void volume | 50.55 cm3 | Connecting rod length | 46 mm | |

| Length | 22.6 mm | Crank radius | 13.8 mm | |

| Internal diameter | 22.6 mm | Eccentricity | 20.8 mm | |

| No. per cylinder | 8 | Displacer stroke | 31.2 mm | |

| Diameter of wire | 0.04 mm | Internal diameter of cylinder | 69.9 mm | |

| Porosity | 0.697 | Working fluid | Helium | |

| Material | Stainless steel | Frequency | 41.72 Hz | |

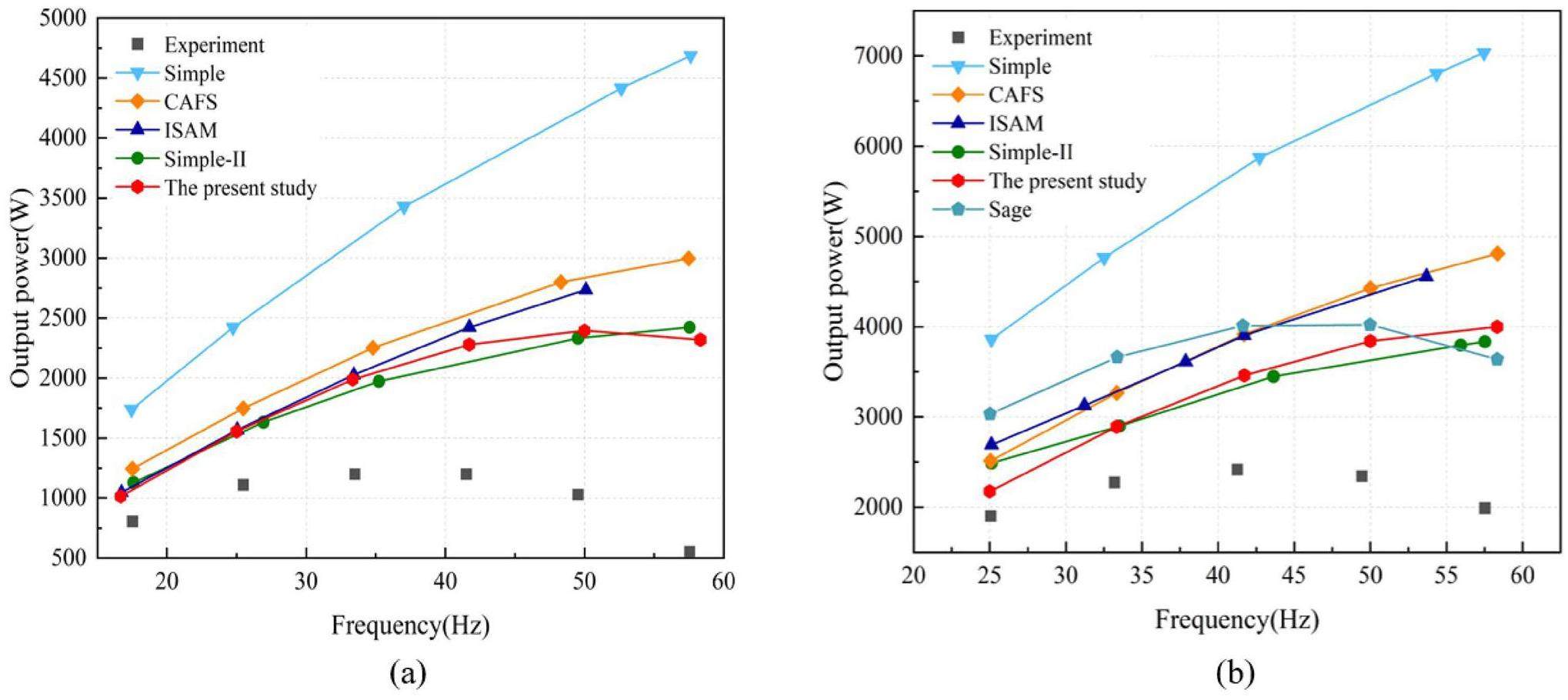

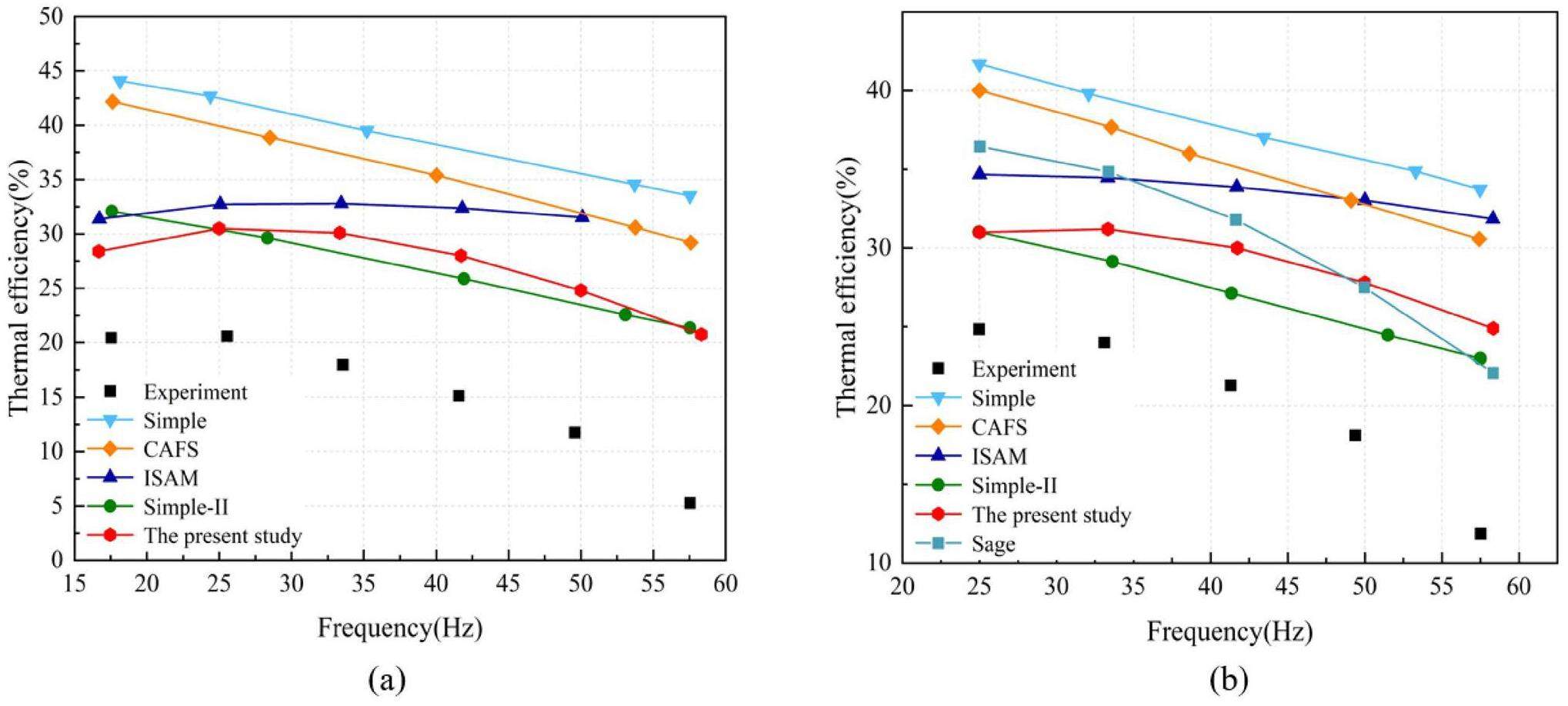

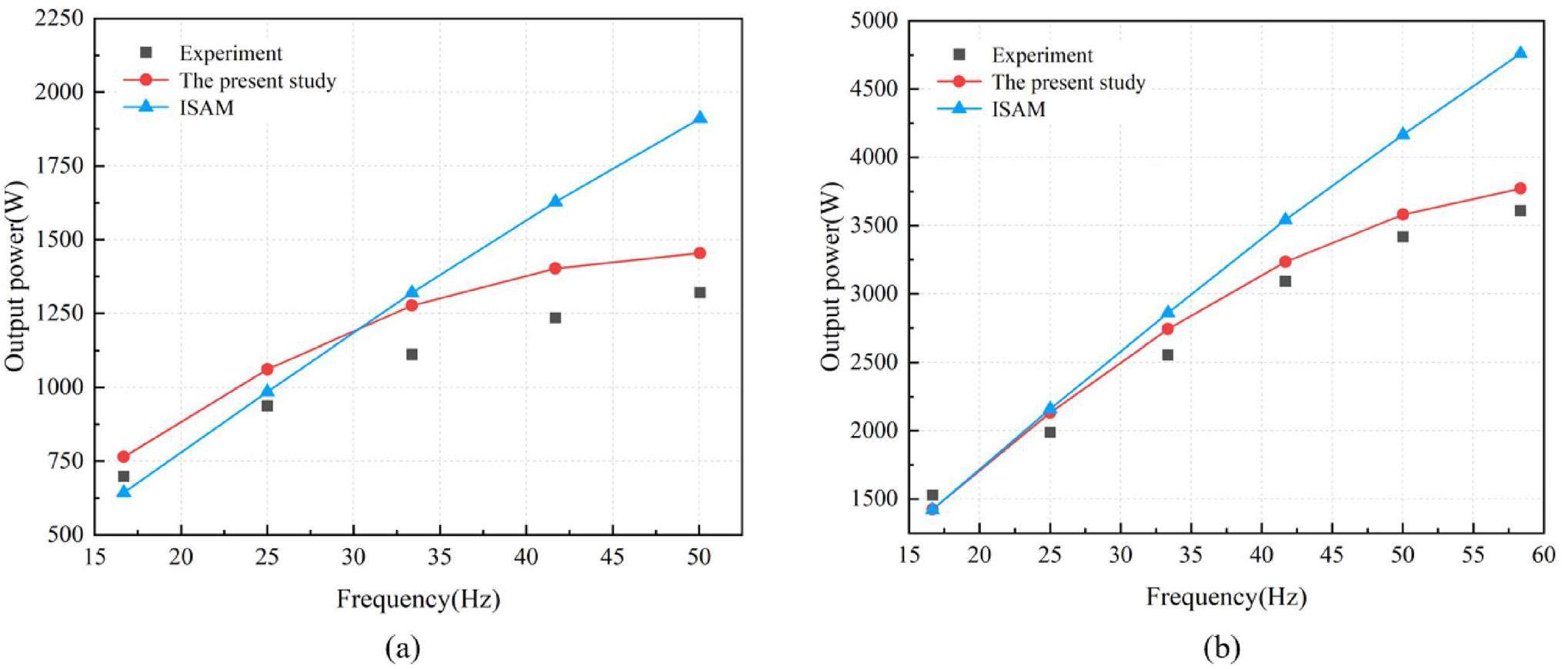

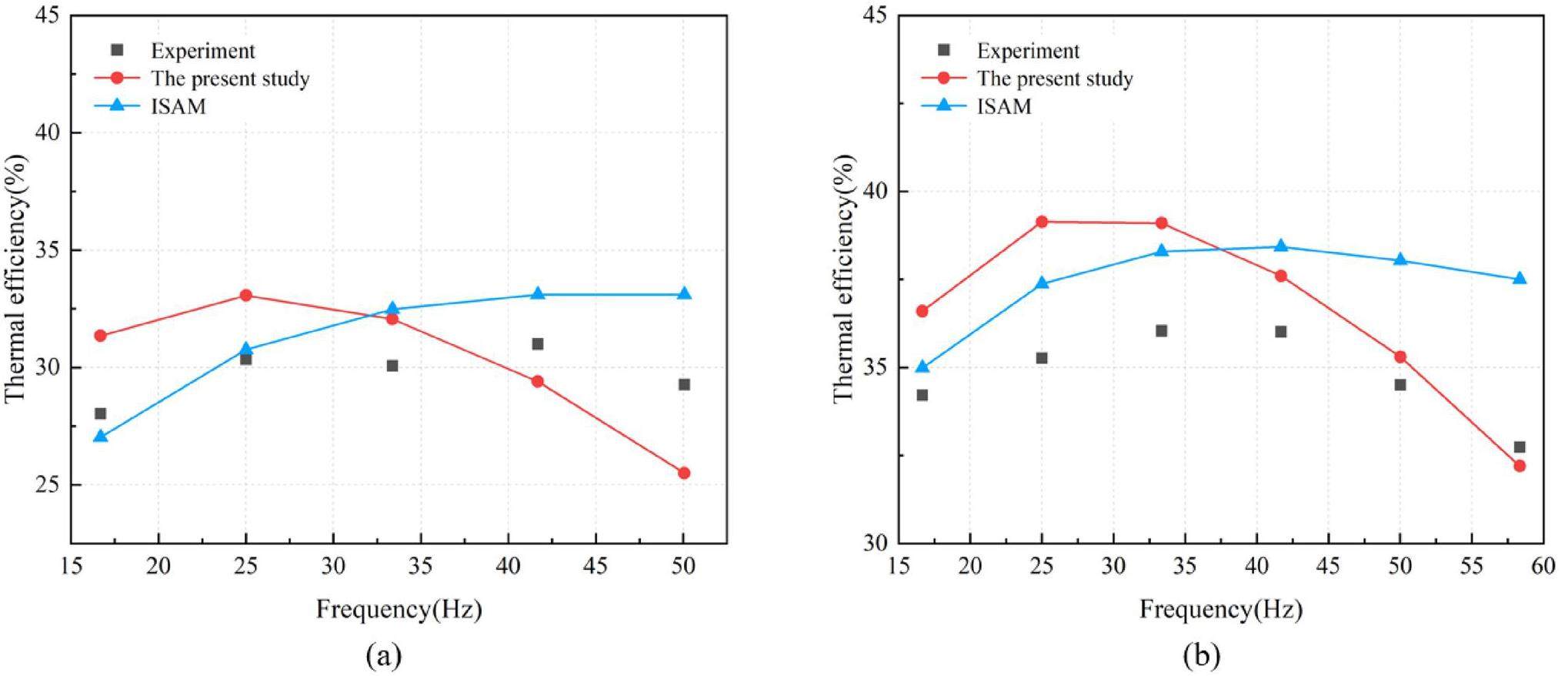

To validate the model, simulations (Helium, Twh = 922 K, Twk = 286 K) were performed against the GPU-3 Stirling engine experiment with two different pressure conditions (Pmean = 2.76 MPa and Pmean = 4.14 MPa). The computational results were compared with the simulation data of the available second-order analysis models (Simple-II, CAFS, ISAM, and simple models) and the third-order analysis software Sage. Experimental data were obtained from NASA experiments on a GPU-3 Stirling engine.

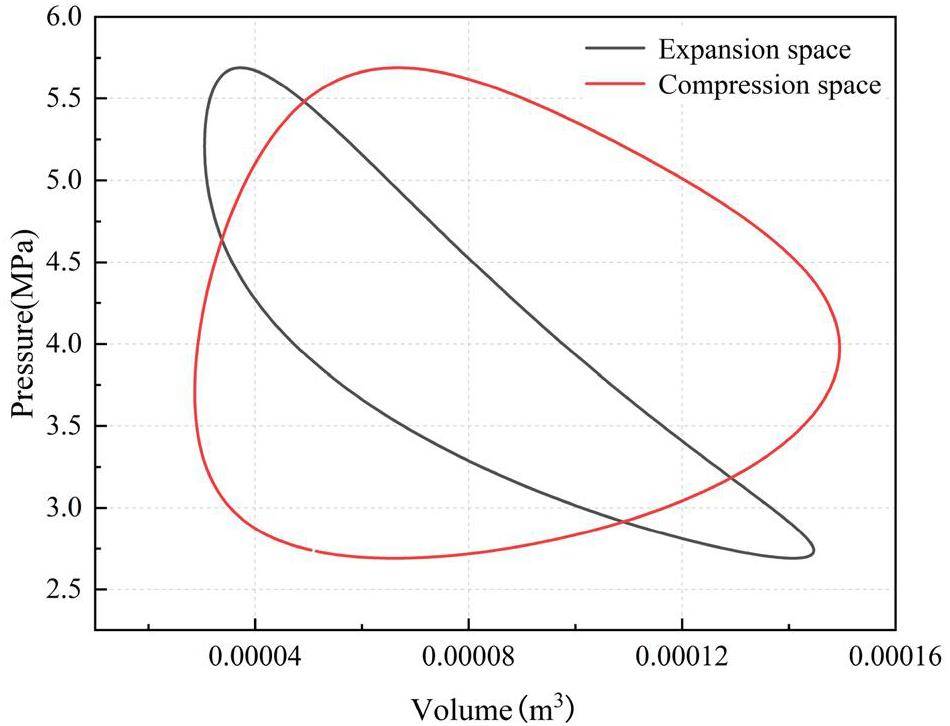

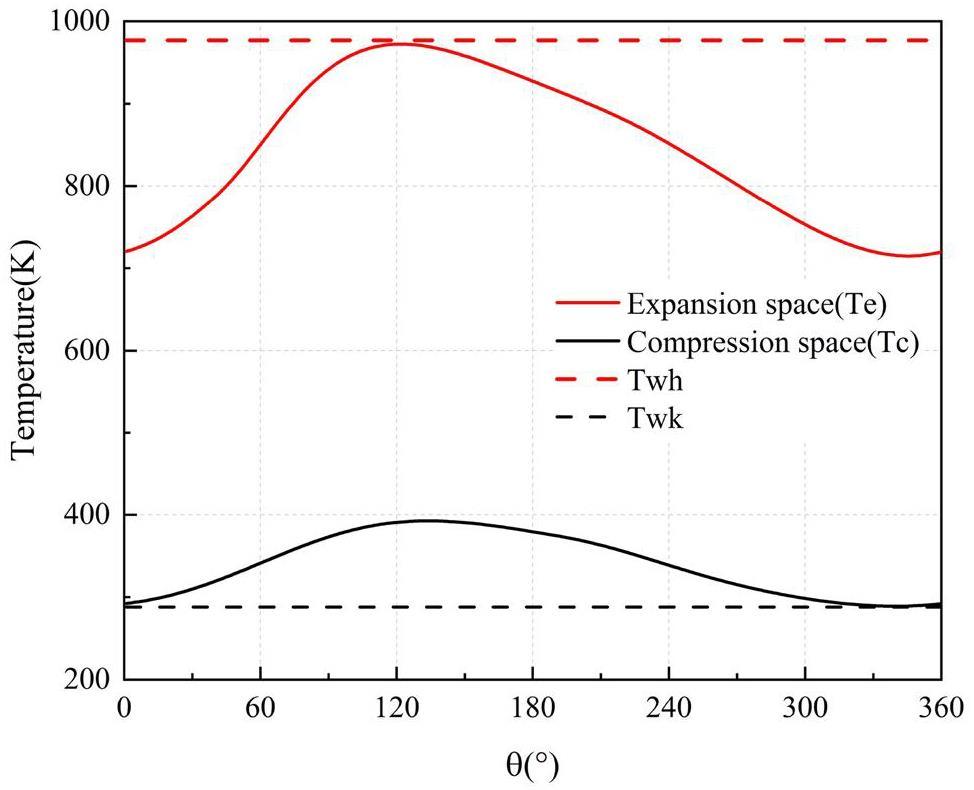

Figures 8 and 9 illustrates the relationship between the working fluid temperature variation with angle in the expansion and compression cylinders, as well as the P-V (pressure-volume) diagram of the cycle. The temperature of the cavity returns to the initial point after one complete rotation of the Stirling rhombic drive mechanism, and the cycle is repeated periodically in accordance with the basic characteristics of the Stirling cycle.

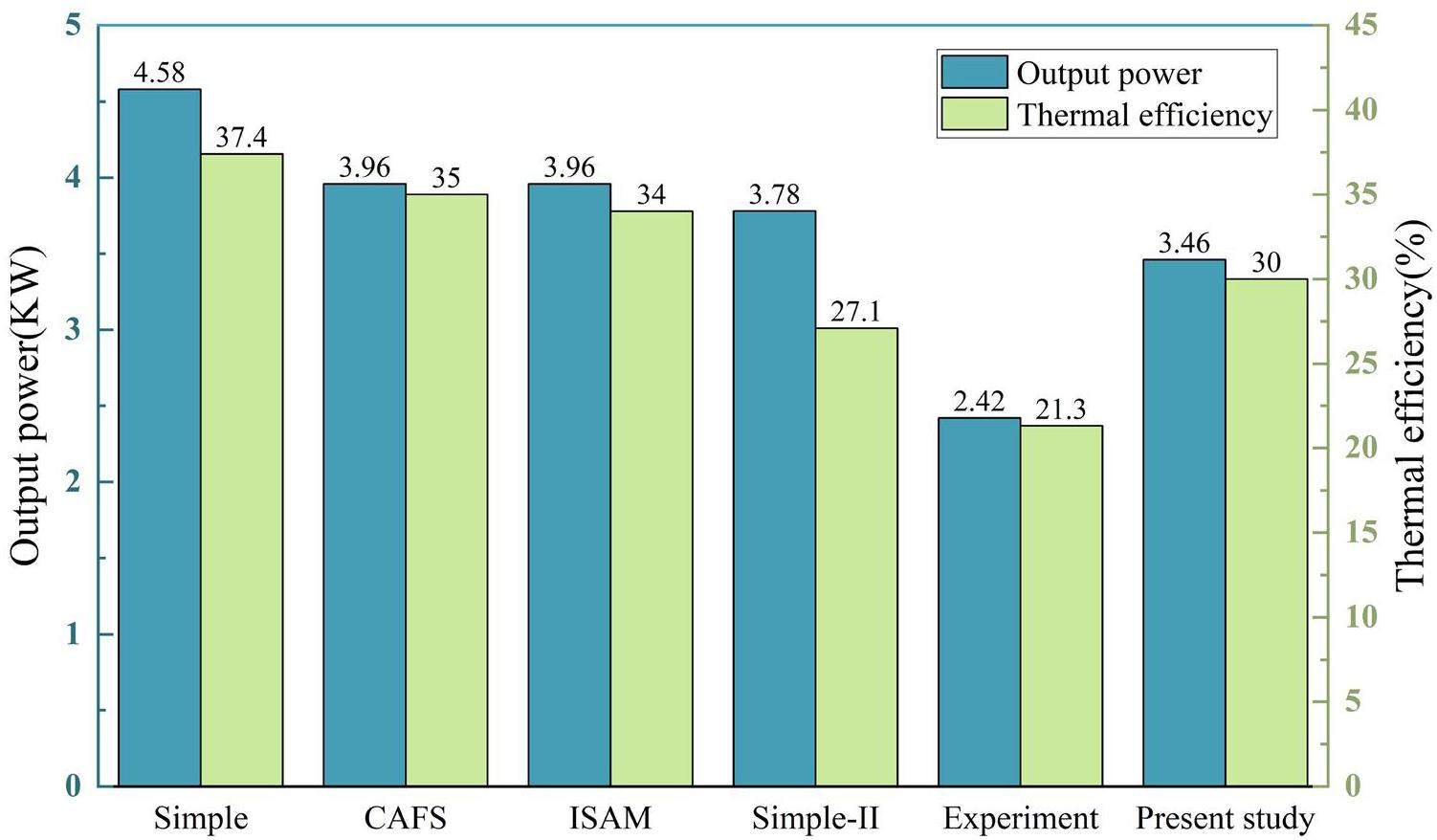

Figure 10 presents a comparison of the output work results between the model in this paper and the existing second-order model at various frequencies. Figure 11 displays a comparison of the cycle efficiency results between the model in this paper and the existing second-order model across different frequencies. Compared with the simple model (Pmean=4.14 MPa), the maximum power error of the proposed model was reduced by 152.5%, and the maximum efficiency error (as a difference) decreased by 10.67%. The average reduction in the power error across all frequency conditions was 110.0%, and the average reduction in the efficiency error was 8.43%. Figure 12 illustrates the comparison of the simulation values between the model in this study and the existing second-order model under the standard operating conditions of 4.14 MPa pressure and 41.67 Hz frequency. Compared with the simple model, the simulation error for the output work was reduced by 46.2%, and the simulation error (as a difference) for cycle efficiency was reduced by 8.7%. Compared with the third-order analytical Sage model, the output work exhibited maximum and minimum errors(as differences) of 28.3% and 4.5%, respectively, with an average error of 11.5%. The cycle efficiency demonstrated maximum and minimum errors (as differences) of 5.43% and 0.30%, respectively, with an error of 1.55%.

A comparison of the simulated and experimental values allowed for the analysis of certain working characteristics of the Stirling engine. When helium was used as the working fluid, the output work of the Stirling engine decreased as the frequency increased under high-frequency conditions (with a working frequency greater than 41.72 Hz), and the cycle efficiency exhibited an overall downward trend within the frequency analysis range defined in this study, which was particularly pronounced in the high-frequency region. In contrast, in the subsequent parameter sensitivity analysis, when hydrogen was used as the working fluid, both the output work and cycle efficiency of the Stirling engine exhibited significant upward trends. This difference is caused by the different material properties of the two substances. In addition, as the working frequency increased, the error between the experimental and simulated values in the engine gradually increased because of other undetermined losses caused by high-frequency oscillating flows.

Validation of the RE-1000 Engine

To further validate the correctness of the model, experimental data from the RE-1000 free-piston Stirling engine, developed by NASA, was utilized for the validation process. The model was validated against the operating conditions and experimental outcomes specified in [40] for test case #1011. Several studies referenced these data to validate RE-1000 engines [35, 36]. The detailed design dimensions and parameters of the RE-1000 are presented in Table 3. Because of the periodic motion of the displacer and power piston, the volume changes in the compression and expansion spaces are described as follows:

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heater | Cooler | |||

| Tube number | 34 | Fin number | 115 | |

| Void volume | 27.33 cm3 | Void volume | 20.43 cm3 | |

| Regenerator | Volume | |||

| Porosity | 0.759 | Expansion space | 27.74 cm3 | |

| Diameter of wire | 0.0889 mm | Compression space | 54.80 cm3 | |

| Void volume | 56.37 cm3 | |||

| Displacer | Phase angle | 57.5° | ||

| Stroke | 24.5 mm | Frequency | 30 Hz | |

| Diameter | 56.4 mm | Working fluid | Helium | |

| Power piston | Heater temperature | 873 K | ||

| Stroke | 28 mm | Cooler temperature | 297 K | |

| Diameter | 57.2 mm | Mean pressure | 70.6 MPa | |

Table 4 lists the results of the comparison between the experimental and simulated values. The relative errors for the input heat, output work, and cycle efficiency are correspondingly -2.4%, 10.4%, and 4.4%. Validation against experimental and simulated data from the GPU-3 and RE-1000 Stirling engines demonstrated the high level of precision of the model.

| Parameters | Present study | Experiment[40] |

|---|---|---|

| Heat in(W) | 3940 (-2.4%) | 4038 |

| Indicated power(W) | 1138 (10.4%) | 1030 |

| Indicated efficiency(%) | 28.9 (4.4%) | 25.5 |

Parameter sensitivity analysis

Effect of frequency and different working fluids

The selection of working fluids for Stirling engines predominantly focuses on gases, with commonly used working fluids being N2, H2, CO2, He, and air. Owing to the superior heat exchange characteristics of small-molecular-weight gases, most technologically advanced high-power Stirling engines employ He or H2 as the working fluid.

To investigate the effects of frequency and different work materials on the output work and cycle efficiency, hydrogen is selected as the work material (Twh=977 K, Twk=288 K), with two different pressure variables set at 1.38 MPa and 2.76 MPa. Figures 13a and 13b plot the changes in the output work with respect to the frequency. Figures 14a and 14b illustrate the changes of the cycle efficiency with the frequency.

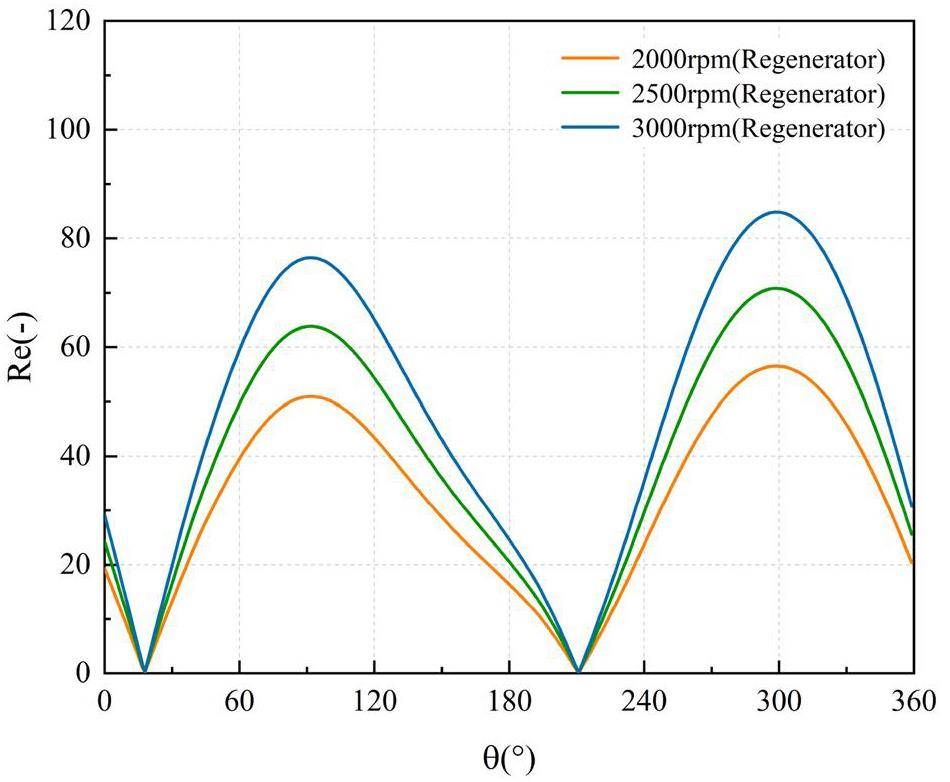

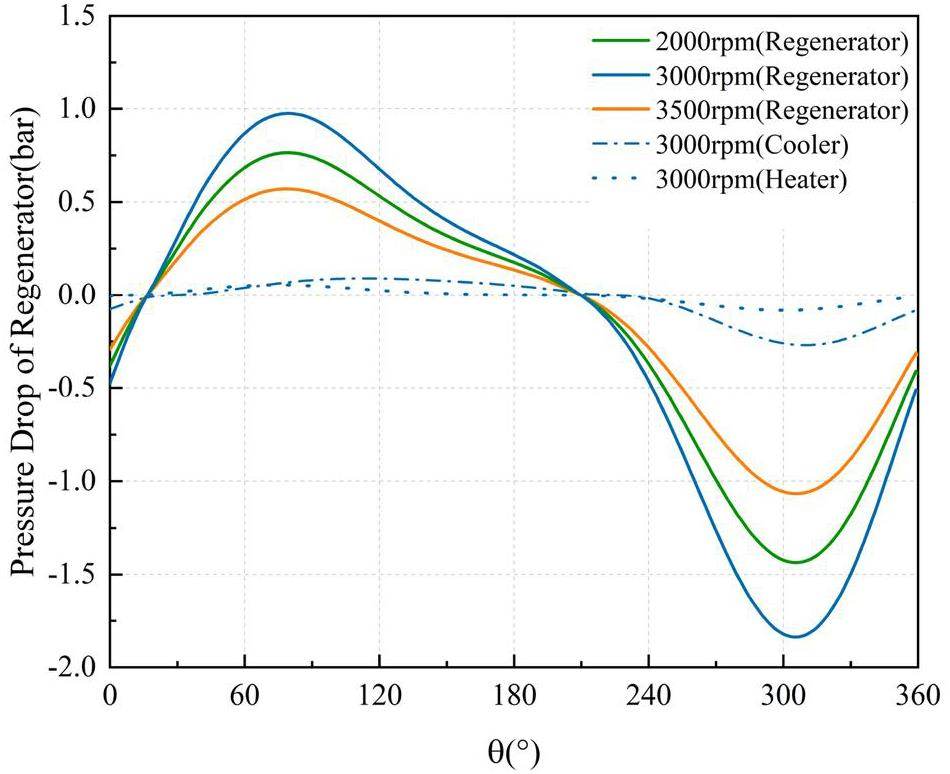

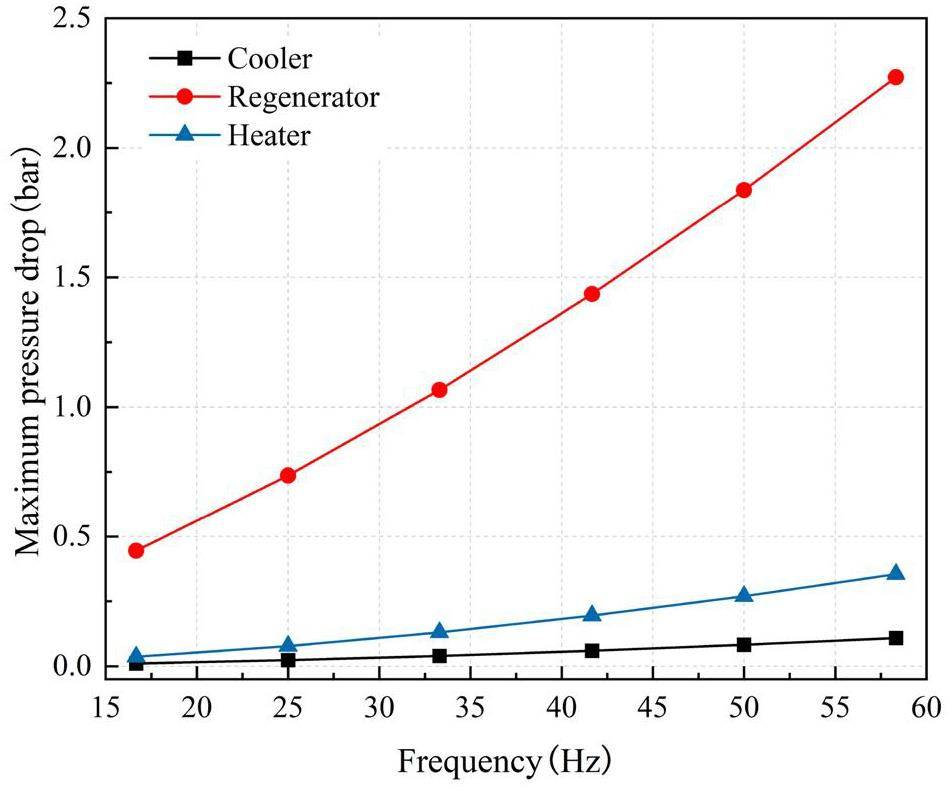

In scenarios with slower rotational speeds, the system efficiency increased with the rotation speed. However, as the rotational speed continued to increase, the system efficiency declined, resulting in a general trend of an initial increase followed by a decrease. When the work material is H2, the power output of the Stirling engine is significantly enhanced with increasing rotational speed, displaying a steep upward trend. However, when the work material is He, a faster rotation speed has a detrimental impact on the output of the Stirling engine, with a less steep upward trend. Due to the screen-like structure of the regenerator, a substantial pressure drop occurs as the working mass flows through it, leading to a loss attributed to flow resistance. Figures 15 and 16 demonstrate the effect of the Reynolds number of the regenerator and different rotational speeds on the resulting pressure loss. Figure 17 demonstrates the variation of the maximum pressure drop within the heat exchanger with frequency. With an increase in the frequency, both the Reynolds number and pressure loss inside the heat exchanger increase. Compared to the pressure loss in the regenerator, the pressure losses in the cooler and heater were negligible, demonstrating that the wire mesh structure of the regenerator was the primary source of pressure loss. The high rotational speed of the Stirling engine causes an oscillating flow and heat exchange of the work material inside the body, which tends to be complicated and results in a significant increase in the flow resistance loss or local loss, which in turn affects the cycle efficiency. H2, which has a lower dynamic viscosity coefficient, produces a smaller flow resistance loss when operating at high rotational speeds than He. However, H2 exhibits poor sealing properties, rendering it susceptible to leakage and explosion, which can cause challenges such as hydrogen embrittlement in certain materials. Therefore, helium is commonly used as the working fluid.

Effect of regenerator parameters

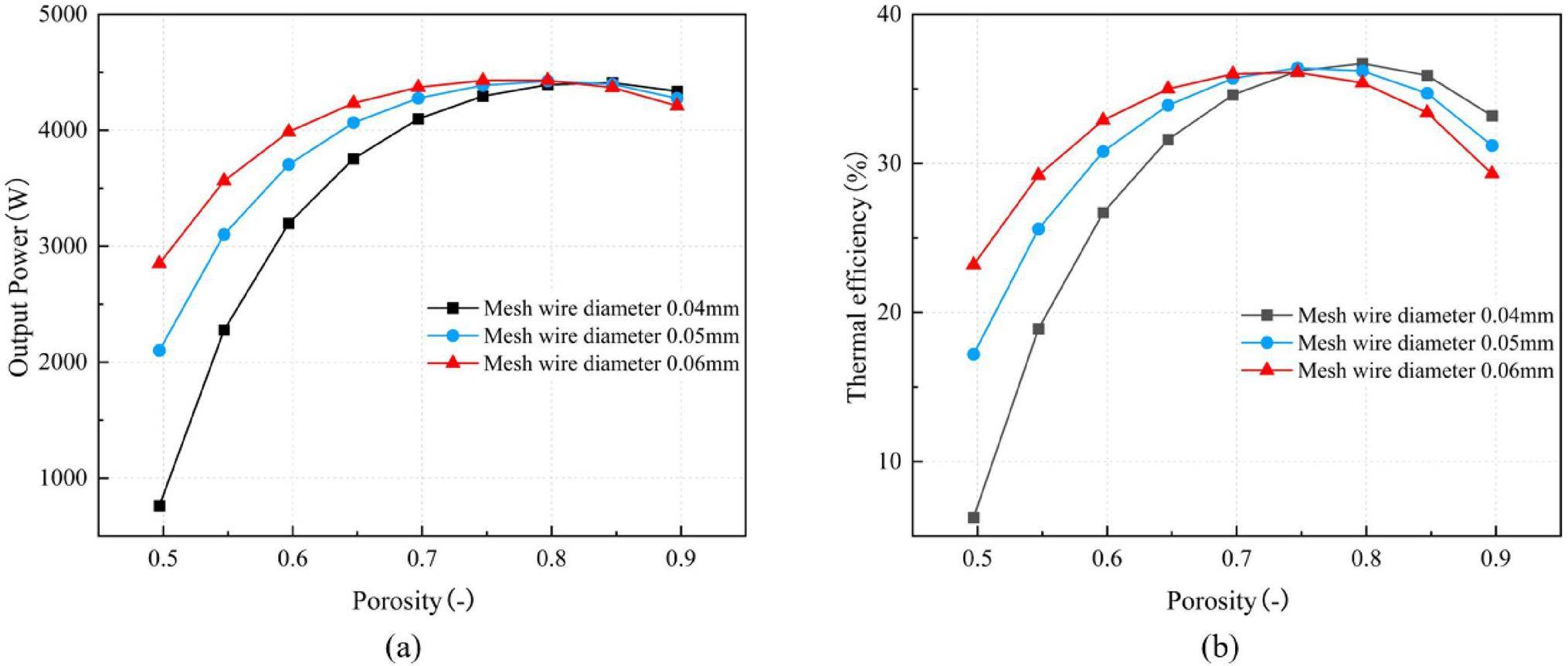

The regenerator features an internal structure filled with a metal wire mesh. Porosity is represented by the ratio of the porous volume of the regenerator to its overall volume. Figure 18 depicts the variation of output work and cyclic efficiency with changes in porosity and wire mesh diameter. For metal wire meshes with different diameters, the cyclic efficiency tended to initially increase and then decrease. This trend is attributed to the fact that an appropriate increase in porosity increases the hydraulic diameter and reduces the wetted area of the mesh in contact with the working fluid. This reduction in the pressure drop across the regenerator leads to a decrease in the flow resistance losses, thereby enhancing the output work and cyclic efficiency of the engine. At lower porosities, a denser mesh configuration results in a smaller hydraulic diameter and an increased wetted area for the regenerator, which can significantly affect the flow resistance and adversely affect the cyclic efficiency and output work.

When the porosity was below 0.797, Stirling engines equipped with larger-diameter wire meshes exhibited higher cyclic efficiencies than those equipped with smaller-diameter meshes. This trend is attributed to the larger convective heat transfer area provided by the larger-diameter meshes under conditions of low porosity. In contrast, when the porosity surpassed 0.797, wire meshes with smaller diameters demonstrated superior cyclic efficiencies, attributable to their comparatively lower flow resistance losses. At a wire mesh diameter of 0.04 mm, a turning point in cyclic efficiency was observed at a porosity of 0.797. With a further increase in porosity to 0.847, there was a slight increase of 0.1% in the output power, whereas the cyclic efficiency decreased by 3%. In conclusion, the engine output and cyclic efficiency were optimal at a porosity of 0.797.

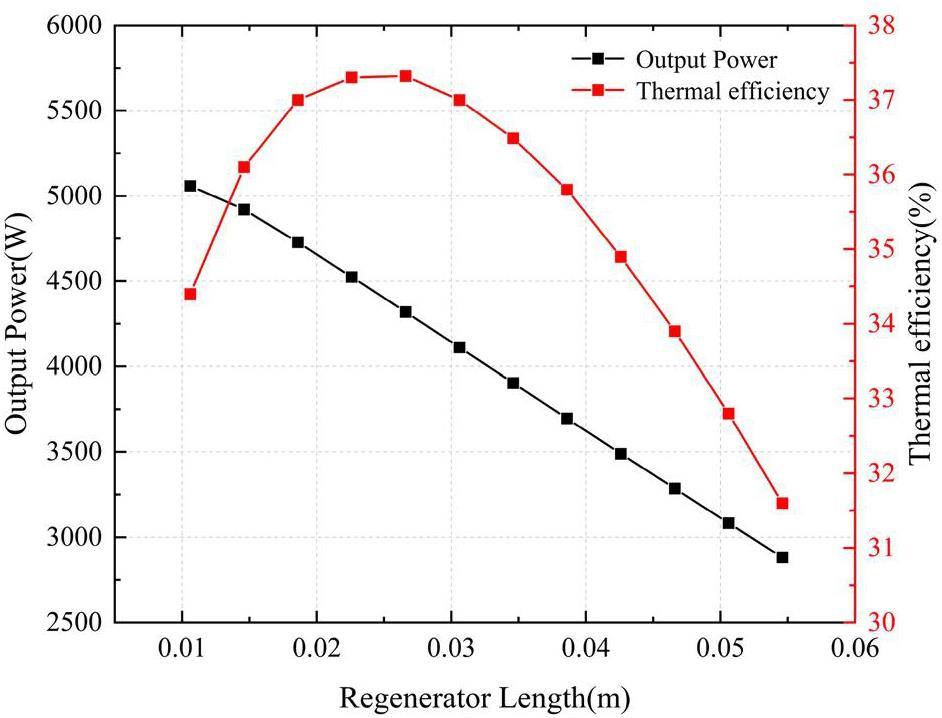

Figure 19 illustrates the variation of output work and cycle efficiency with the length of the regenerator. At a mean pressure of 4.14 MPa, an inflection point appears in the cycle efficiency curve when the regenerator length is approximately 0.025 m. When the regenerator length is less than 0.025 meters, an increase in length leads to a larger heat exchange area, allowing for more sufficient heat transfer within the regenerator’s metal wire mesh, which in turn increases cycle efficiency with the increase in length. Moreover, because the pressure losses due to flow resistance inevitably increase with length, the output work will necessarily decrease as the regenerator lengthens. Consequently, when the regenerator length exceeds 0.025 m, the positive effect of the increased heat exchange area on cycle efficiency is insufficient to offset the negative effect caused by increased losses, resulting in a decline in cycle efficiency. At Pmean=4.14 MPa, the optimal regenerator length is approximately 0.025 m.

Effect of temperature of heat exchangers

During the actual operation of a space nuclear reactor, the hot-end temperature of the Stirling system fluctuates with changes in the core temperature of the nuclear reactor, and the performance of the radiative heat rejection system can also affect the cold-end temperature. Shifts in both the hot- and cold-end temperatures directly affect the quantity of heat absorbed and released by the working fluid gas, thereby influencing the output work and cyclic efficiency of the Stirling engine. Consequently, for space nuclear power reactors, it is necessary to assess the impact of cold- and hot-end temperatures on the performance of Stirling systems.

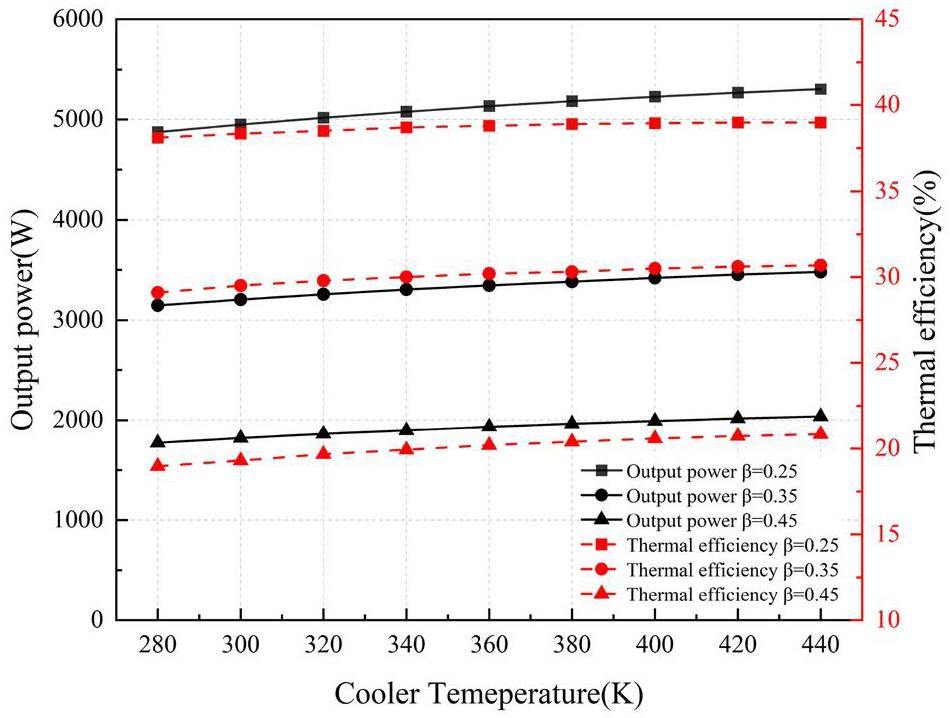

Figure 20 demonstrates the variation in output work and cyclic efficiency of the Stirling engine at different temperature ratio conditions as the cooler temperature increases from 280 K by increments of 20 K up to 440 K. At a temperature ratio of 0.25, the output work increased from 4874 to 5301 W, an increment of 2.3%. At a temperature ratio of 0.35, the output work increased from 3146 to 3480 W, which is an increase of 5.4%. When the temperature ratio was 0.45, the output work increased from 1773 to 2037 W, denoting an increase of 9.8%. When the temperature ratio was fixed, alterations in the cooler temperature had a negligible influence on the output work and cyclic efficiency. In actual scenarios, owing to material constraints, the heater of a Stirling engine cannot reach excessively high temperatures; therefore, an ideal case is considered here. At a constant cooler temperature, as the temperature ratio rose from 0.25 to 0.35, the output work decreased by an average of 34.8%, and the cyclic efficiency decreased by an average of 8.61%. As the temperature ratio increased from 0.35 to 0.45, the output work decreased by an average of 42.3%, and the cyclic efficiency decreased by an average of 10.0%. In particular, the lower the temperature ratio, the higher the output power and cyclic efficiency of the system. Conversely, the higher the temperature ratio, the lower the output power and cyclic efficiency of the system. At a constant cooler temperature, a higher heater temperature is more conducive to achieving satisfactory output work and cyclic efficiency. Similarly, under the condition of a constant heater temperature, the lower the cooler temperature, the better the engine performance. However, in practice, owing to the impact of environmental factors, coolers cannot achieve excessively low temperatures, and this limitation should be considered based on the actual conditions. The operating temperature of the working fluid in high-temperature heat pipes exceeds 730K. The most frequently used sodium heat pipes have a working temperature range of 700-1100K. The hot end of the Stirling engine transfers heat to a high-temperature heat pipe through solid-to-solid contact, whereas the cold end can only dissipate heat into the space environment through radiative cooling. Therefore, for space power devices, thermal efficiency is particularly important. A higher thermal efficiency under the same weight and cost conditions allows for higher power output and extended operation.

In the parameter sensitivity analysis of the cold- and hot-end temperatures, we fixed the temperature boundaries to simulate steady-state operating conditions. However, temperature control and management are complex and critical issues for practical engineering applications. For example, during the reactor start-up process, there is a significant concern about controlling the thermal balance throughout the entire process, from the heat generated in the core to its transfer via high-temperature heat pipes to the Stirling engine, and finally to the heat rejection system. Heat pipes are often quite fragile, and initiating a cold start of a Stirling engine can lead to thermal imbalance, causing the heat pipes to fail and posing a risk to reactor safety. Therefore, to address the startup issue, it is necessary to devise a reasonable temperature control plan to balance the heat transfer between the various components. This challenge will be further explored in a subsequent study.

Conclusion

Stirling engines with their high efficiency, strong reliability, and compact structure have attracted significant attention from researchers, particularly in recent decades, leading to their substantial development and irreplaceable role in various fields. To investigate the operational characteristics of Stirling engines, this study established a second-order analysis model, thoroughly validated it, and conducted extensive parameter analysis based on the validated model. Specific work includes

(1) The model developed in this study was fully validated against the experimental data of the GPU-3 Stirling engine obtained from NASA. Under the condition of 4.14 MPa pressure, compared to the simple model, the maximum power error was reduced by 152.5%, and the maximum efficiency error was reduced by 10.67%. The average reduction in the power error across all frequency conditions was 110.0%, and the average reduction in the efficiency error was 8.43%. Furthermore, comparisons were conducted with the experimental data from the RE-1000 free-piston Stirling engine. The results indicate that the model developed in this study demonstrates an accuracy equivalent to that of existing second-order models, thereby confirming the correctness of the model.

(2) This study investigated the impact of working fluids on the operational characteristics of Stirling engines. The results indicate that hydrogen, with its low dynamic viscosity coefficient and reduced flow resistance losses, can generate a higher output power when used as the working fluid in Stirling engines. In addition, research has revealed that high rotational speeds lead to complex oscillatory flow phenomena, resulting in increased pressure drops. Furthermore, as the Reynolds number increased, the flow resistance losses increased, leading to a reduction in the output power of the engine.

(3) The output power and cycle efficiency of the Stirling cycle were simulated for different wire mesh porosities and diameters. The results showed that the porosity, wire diameter, and regenerator length had a significant impact on the performance of the Stirling engine. When the wire mesh diameter is 0.04 mm, the optimal porosity is 0.797, and the optimal regenerator length is approximately 0.025 m.

(4) The performance of a Stirling engine in a space nuclear reactor is significantly influenced by the hot- and cold-end temperatures. The variations in these temperatures directly affect the heat exchange and efficiency of the engine. In addition, optimal temperature ratios enhance the output work and efficiency, whereas extreme values can lead to significant reductions. Moreover, thermal management, particularly during start-up, is critical for preventing thermal imbalances and ensuring reactor safety.

Space nuclear power: opening the final frontier

. in: Proceedings of 4th International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference and Exhibit (IECEC),Design, ground test and flight test of SNAP 10A, first reactor in space

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 5, 7-21 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5493(67)90074-XDeployment history and design considerations for space reactor power systems

. Acta. Astronaut. 64, 833-849 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2008.12.016Study of space reactors for exploration missions

. in Proceedings of the 4th European Conference for Aerospace Sciences (EUCASS),A comparison of Brayton and Stirling space nuclear power systems for power levels from 1 kilowatt to 10 megawatts

. Amer. Inst. Phys. 552(1), 1017-1022 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1358045Initiation and development of heat pipe cooled reactor

. Nucl. Power. Eng. 40(4), 1-8 (2019). (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.13832/j.jnpe.2019.04.0001The technology of micro heat pipe cooled reactor: A review

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 135,Heat pipe failure accident analysis in megawatt heat-pipe-cooled reactor

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 149,Coupled neutronic, thermal-mechanical and heat pipe analysis of a heat pipe cooled reactor

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 384,Steady-state multi-physics coupling analysis of heat pipe cooled reactor core

. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 165,A review of liquid metal high temperature heat pipes: Theoretical model, design, and application

. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Tran. 214,Stirling air engine and the heat regenerator

. US Patent,Design and analysis of a free-piston stirling engine for space nuclear power reactor

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 53(2), 637-646 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2020.07.011Design and heat transfer optimization of a 1 kW free-piston stirling engine for space reactor power system

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 53(7), 2184-2194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.01.022Dynamic performance of the combined stirling thermoelectric conversion technology for a lunar surface nuclear power system

. Appl. Therm. Eng. 221,Operation and safety analysis of space lithium-cooled fast nuclear reactor

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 166,Modified Stirling cycle thermodynamic model IPD-MSM and its application

. Energ. Convers. Manage. 260,The heatpipe-operated Mars exploration reactor (HOMER)

. Appl. Int. Forum, 552(1), 797-804 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1358010NASA’s Kilopower reactor development and the path to higher power missions

. 2017 IEEE Aerospace conference 1-14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/AERO.2017.7943946Multi-physics coupling analysis of test heat pipe reactor KRUSTY based on MOOSE framework

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 414,Development and application of a transient analysis code for heat pipe cooled reactor systems

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 419,The Kilopower Reactor Using Stirling TechnologY (KRUSTY) nuclear ground test results and lessons learned

. 2018 International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, 4973 (2018). https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2018-4973Stirling engine design Manual. NASA CR-135382

. (1978).Simple-II: a new numerical thermal model for predicting thermal performance of Stirling engines

. Energy 69, 873-890 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2014.03.084CAFS: The Combined Adiabatic–Finite Speed thermal model for simulation and optimization of Stirling engines

. Energ. Convers. Manage. 91, 32-53 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2014.11.049Improved simple analytical model and experimental study of a 100 W β-type Stirling engine

. Appl. Energ. 91, 32-53 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.02.069A transient one-dimensional numerical model for kinetic Stirling engine

. Appl. Energ. 183, 775-790 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.09.024A third-order numerical model and transient characterization of a β-type Stirling engine

. Energy, 222,An approach to combine the second-order and third-order analysis methods for optimization of a Stirling engine

. Energ. Convers. Manage. 165, 447-458 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2018.03.082A computational fluid dynamics study on the heat transfer characteristics of the working cycle of a β-type Stirling engine

. Energ. Convers. Manage. 88, 177-188 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2014.08.040CFD simulation to investigate hydrodynamics of oscillating flow in a beta-type Stirling engine

. Energy 153, 287-300 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.04.017Numerical analysis of fluid dynamics and thermodynamics in a Stirling engine

. Appl. Therm. Eng. 189,Titanium-water heat pipe radiators for space fission power system thermal management

. Energy 33(7), 1100-1114 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12217-020-09780-5Development and validation of an improved quasisteady flow model with additional parasitic loss effects for Stirling engines

. Int. J. Energ. Res. 2024(1),Coupled thermodynamic–dynamic semi-analytical model of free piston Stirling engines

. Energ. Convers. Manage 52(5), 2098-2109 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2010.12.014Design and performance optimization of GPU-3 Stirling engines

. Energy, 33(7), 1100-1114 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2008.02.005The Direct Method from Thermodynamics with Finite Speed used for Performance Computation of quasi-Carnot Irreversible Cycles

. Rev. Chim-Bucharest, 63, 74-81 (2012).A comprehensive review on modeling and performance optimization of Stirling engine

. Int. J. Energ. Res. 44(8), 6098-6127 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/er.5214RE-1000 free-piston Stirling engine sensitivity test results. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Report 1

. (1986).The authors declare that they have no competing interests.