Introduction

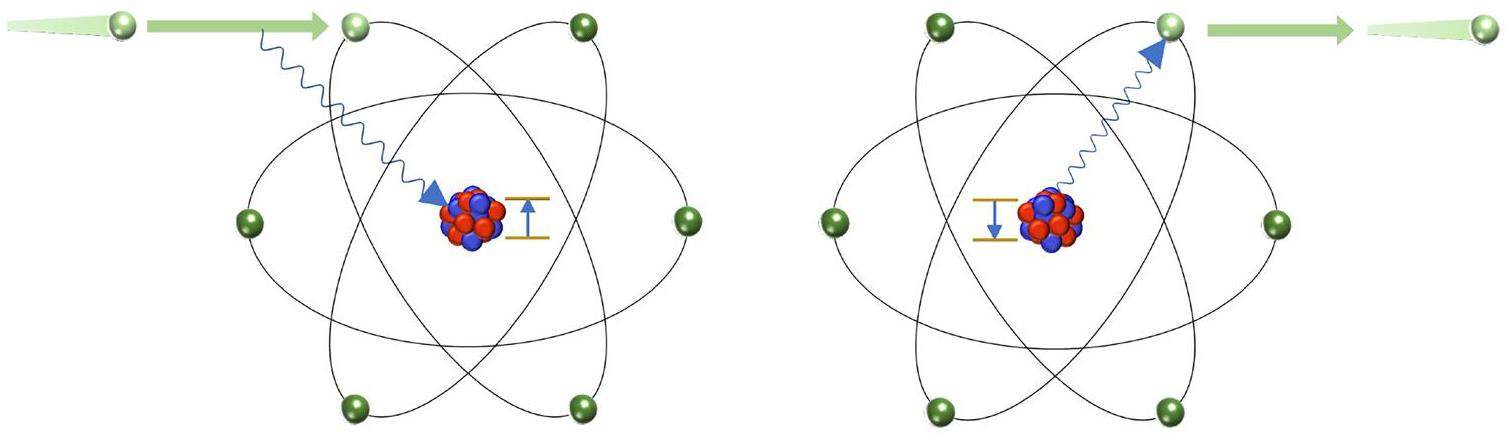

Nuclear excitation by electron capture (NEEC) involves a positively charged ion capturing a free electron, leading to the excitation of its nucleus. This intriguing process was first reported by Goldanskii and Namiot in 1976, who explored its potential for observation in the laser-generated plasma of 235U [1]. Originally referred to as inverse internal electron conversion, NEEC represents the inverse mechanism of internal conversion (IC) [2-4], as shown in Fig. 1.

The NEEC process has a profound significance across various fields, including astrophysics and nuclear physics. For example, in astrophysical environments, this mechanism may influence nucleosynthesis. Elucidating nuclear mechanisms such as NEEC in astrophysical plasmas is essential to enhancing our understanding of the formation, evolution, and interactions of stellar bodies, galaxies, and other astronomical entities [5]. Furthermore, NEEC is expected to serve as an important method for nuclear isomer production with broad applications across various domains, including nuclear medical treatment [6, 7], nuclear batteries [8-10], nuclear clocks [11, 12], and nuclear lasers [13].

NEEC has been the subject of extensive theoretical analyses and experimental proposals since it was first reported nearly half a century ago, but it is yet to be confirmed experimentally. These efforts encompass a range of methodologies, including the use of cooling storage rings [14], ion accelerators [15-19], electron beam ion traps (EBIT) [20], and others based on laser-induced plasma [7, 21-23].

The primary challenge in detecting NEEC is the presence of substantial background noise. Pálffy et al. noted that by employing a Feshbach projection operator formalism to derive cross-sections of various processes during electron capture [24], including NEEC, dielectronic recombination (DR) [25], and radiative recombination (RR) [26], notable DR and RR processes generate signals that closely mimic those from NEEC, thereby introducing significant background noise in experiments [27, 28]. This issue is particularly evident in experiments involving the isomer 93mMo, where a significant discrepancy exists between the theoretical predictions and experimental results. Signals initially attributed to NEEC were later suspected to have originated from other mechanisms [17, 18, 29-32].

In addition to the basic NEEC process, several other variants have been extensively explored in the literature. These include NEEC with X-rays (NEECX) [33], NEEC in excited ions (NEEC-EXI) [34, 35], and NEEC with vortex beams [36]. NEECX involves the capture of an electron into an excited atomic orbital rather than the ground state, followed by the emission of an X-ray photon [33]. This process facilitates coincidence measurements by simultaneously detecting the x- and γ-photons. On the other hand, NEEC-EXI is the process in which an electron is captured to an inner-shell vacancy in an atom that is already in an excited state [34].

NEEC with vortex electron beams introduces additional intriguing features into the study of NEEC. Vortex beams, distinguished by their helical wavefronts, carry an intrinsic orbital angular momentum (OAM) along the propagation direction [37-41]. This intrinsic OAM of vortex states introduces an additional degree of freedom compared with plane-wave states by introducing new selection rules for nuclear processes, offering novel opportunities in the study of nuclear excitation processes. Since the initial proposal concerning optical vortex beams in Ref. [42], optical vortices have garnered significant interest, leading to a plethora of remarkable achievements and applications. Vortex photons have been intensively studied in fields such as quantum communications, nonlinear optics, optical trapping, microscopy, nanotechnology, astrophysics, and manipulations of atomic transitions [37, 38, 43, 44]. In the context of NEEC, the use of electron vortex beams is expected to enhance the cross-section by up to four orders of magnitude [36].

In short, NEEC provides a quantum many-body platform that involves the interplay between atomic and nuclear systems. However, despite its fundamental nature, the process is not yet fully understood. In this mini-review, we begin with a historical overview of the theoretical work on NEEC, followed by an examination of the role of NEEC in astrophysical environments and laser-induced plasmas. In addition, the current status of NEEC studies using vortex beams and traditional accelerators is discussed. Finally, a brief summary of the proposed methods is presented.

Theoretical cross-section calculation of NEEC

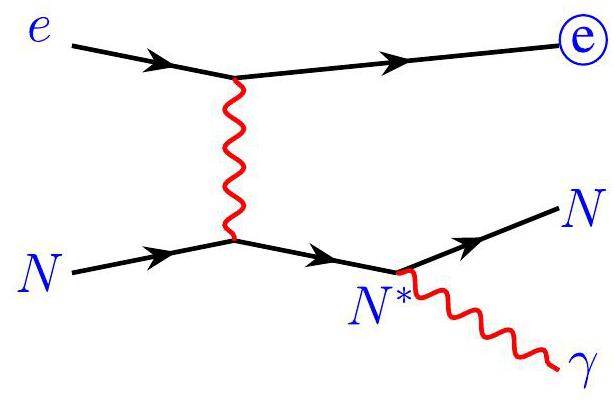

In the theoretical treatment of the NEEC process, the capture of a free electron into a bound state by a positively charged ion is considered, which leads to the excitation of the nucleus. Typically, a γ-photon is emitted as follows. A Feynman diagram illustrating this process is presented in Fig. 2, involving two steps and three states. The initial state is represented by

In this treatment, the nuclear excitation results from a time-dependent electromagnetic field acting on the nucleus. Typically, the influence of this field is minimal and can be effectively addressed using first-order quantum-mechanical perturbation theory. The excitation probability can be expressed in terms of the same nuclear matrix elements that govern radiative transitions between nuclear states. Detailed illustrations of the main physical features of this process are provided in Ref. [24]. In the following discussion, we present the mathematical results of the quantum-mechanical theory for the NEEC process.

The cross-sections of the NEEC process for a free electron with kinetic energy ε are expressed as follows: [24]:

As previously noted, electromagnetic excitation involves the same nuclear matrix elements as the radiative transitions of the corresponding multipole order. Thus, for a given multipolarity

NEEC in astrophysical environments

The NEEC process can significantly affect astrophysical plasmas by altering the proportion of nuclear isomers present, similar to the influence of other nuclear reactions [47]. Its effects may vary with the plasma temperature, which influences the electron energy distribution. Further research is required to clarify the role of NEEC in these environments and understand its potential impact on the behavior and evolution of astrophysical plasmas.

NEEC in astrophysical plasma

The role of NEEC in cosmic nucleosynthesis is poorly understood. Astrophysical nucleosynthesis calculations are dependent on accurate nuclear reaction rate inputs, and NEEC cross-sections could be critical for certain nuclear reactions within astrophysical plasmas. Considering that nucleosynthesis is a network of reactions, it is crucial to recognize that a single reaction rate can profoundly influence the astrophysical evolution. NEEC may significantly affect the production of isomers, thereby influencing nucleosynthesis processes.

A nuclear isomer is an excited state in which the structural effects within the nucleus inhibit its decay, potentially granting the isomeric state a longer lifetime than those of ordinary nuclear states. Known nuclear isomers exhibit a remarkable range of lifetimes, from 1015 years for 180mTa—exceeding the widely accepted age of the universe—to as short as approximately 1 ns, as is commonly recognized [48, 49]. From the perspective of isomer types, while shape isomers, spin traps, and seniority isomers tend to be concentrated in narrow mass regions on the nuclear chart, K-isomers are more broadly distributed, particularly in heavy and well-deformed nuclei [50].

Isomers are noteworthy not only for their unique intrinsic properties but also for their potential practical applications. The energy density of conventional energy sources relies on chemical processes, and is fundamentally determined by the energy stored in chemical bonds—the so-called “chemical limit.” To overcome this limitation, it is necessary to explore the subatomic realm. Particularly interesting are nuclear isomers with half-lives of approximately one year or more. When energy is required, the reduction of the isomer population can be induced by providing the appropriate energy to excite the nucleus from the isomer to a higher state (referred to as the triggering level), and then allowing it to decay to the ground state via paths that bypass the isomer [51-53]. This process results in the release of energy on a much smaller time-scale than the natural decay of isomers. Among the proposed triggering processes, the triggering of long-lived nuclear isomeric states via coupling to the atomic shells in the NEEC process has attracted significant interest [14].

Low-lying triggering levels are desirable for obtaining a high-energy gain [54]. Identifying suitable triggering levels above the isomer is crucial to facilitate decay. For instance, most isomers, such as the 103.00 keV isomer in 81Se, predominantly transition to lower energy states, with transitions to the ground state occurring 99.949% of the time [55]. A sufficient connection to the ground state ensures that the destruction of the isomer does not deviate from the thermal equilibrium. Historically, the depletion of 178m2Hf by low-energy (∼10 keV) photons was claimed by Collins et al. [56], but was subsequently refuted by more sensitive measurements [57, 58]. Thus, while an isomer with a long lifetime may prevent thermalization at low temperatures, in a hotter environment, thermally driven transitions through intermediate states can enable equilibration.

In addition, some isomers isolated from the ground state in the astrophysical sites where they are produced are not populated during the production of the nucleus. Thus, although some isomers play an influential role in astrophysical nucleosynthesis, most do not. This distinction leads to the definition of “astrophysical isomers” or “astromers” as nuclear isomers that have a significant influence in a specific astrophysical environment. Unlike their associated ground states, astromers behave differently and should be treated as separate species within nucleosynthesis networks. These networks may involve transitions that create and destroy these states [59].

In astronomical environments, the dynamics are governed by a multitude of microscopic processes, including electromagnetic processes such as ionization and RR, as well as nuclear reaction processes. The first two are crucial for maintaining charge balance and primarily occur between electrons and ions. Meanwhile, nuclear reaction processes may involve not only nuclei but also atoms, as seen in the case of NEEC. Cosmic plasmas are created through ionization, which can occur in several ways, including collisions of fast particles with atoms, photoionization by electromagnetic radiation, or electrical breakdown in strong electric fields. The charge state of the plasma is determined by the balance between ionization and recombination, with RR contributing significantly. Free electrons, abundant in astrophysical environments, are fundamental to the NEEC process. Thus, NEEC potentially plays a crucial role in nuclear excitation through electromagnetic interactions between electrons and ions during the recombination process.

Numerous nuclear interactions contribute to the production of elements during cosmic nucleosynthesis. Most of the hydrogen (H) and helium (He), along with a small amount of lithium (Li), were formed during the first 3 min following the Big Bang. This early element formation is a key aspect of Big Bang Nucleosynthesis [60-63], where the heavier elements required for the formation of complex matter, including organic matter and life, are predominantly produced through fusion processes. In addition, isotopes of elements heavier than iron (Fe) are primarily synthesized via neutron-capture processes (n-capture), including slow (s) and rapid (r) neutron-capture mechanisms. This is due to the strong Coulomb barrier that prevents their formation by fusion alone [60, 64-66].

The potential role of NEEC in the depletion or accumulation of isomeric states within highly charged ions in dense stellar plasmas, particularly in the context of the s-process, has attracted significant attention[47, 67-69]. During this process, a seed nucleus undergoes neutron capture to form an isotope with a higher atomic mass, followed by beta decay if it is unstable. Notably, nuclei along the s-process path tend to remain in isomeric states when the condition

Beyond affecting isomeric depletion, any nuclear reaction chain involving an intermediate isomeric state can be affected by the NEEC process. For example, consider the

NEEC is especially advantageous in extremely hot plasmas, which are better settings where NEEC can significantly influence nuclear reactions. This is because the reaction rate of NEEC increases as the charge states of ions increase [24]. Therefore, when performing astrophysical nucleosynthesis calculations, it is essential to incorporate NEEC rates (λNEEC) for ions with zero, one, or two initially bound electrons into the nuclear reaction rate inputs.

To put it succinctly, viewing nucleosynthesis as just a series of interconnected reactions may be too simplistic. Recognizing that a single reaction rate, including NEEC, can have a profound impact on astrophysical evolution is vital. NEEC can significantly affect both the accumulation and depletion of isomers, thereby playing a pivotal role in nucleosynthesis.

Nuclear structure models for

In the NEEC process, identifying the NEEC rate is dependent on understanding the transition probabilities from the isomer to the triggering level [24]. These probabilities, which are crucial for evaluating the efficiency of triggering, is dependent on both the nuclear transition selection rules and the structural characteristics of the isomer and triggering level. If these transition probabilities have not been measured experimentally, they must be estimated using reliable nuclear structure model calculations.

For instance, in the case of the 21/2+ isomer in 93Mo (with excitation energy Ex = 2.425 MeV and half-life

To adequately account for the structure of the isomers and triggering levels in discussions, theories aimed at calculating the NEEC cross-sections must incorporate dedicated nuclear structure models. This critical integration of NEEC theory with modern nuclear structure models, which would enable a microscopic description of the interaction between the nuclear and atomic levels, remains an unfulfilled need. Among existing modern structure models, the nuclear shell model is the preferred choice [73-75].

The shell model provides a powerful framework for detailed nuclear structure studies that are crucial for understanding nuclear isomers and their effects under various conditions. This is because theoretical states in these calculations must be eigenstates of basic quantum numbers, such as angular momentum, parity, and isospin, given that all nuclear transitions occur between the initial and final states with well-defined quantum numbers. Shell model calculations typically require significant computational resources. Thus, a minimal set of basis states that adequately captures the essential physics is sought. For nuclei that are neither heavy nor strongly deformed, only a limited number of single-particle states are used to define the low-energy structure. In such cases, the conventional spherical shell model can leverage the reduced basis to compute relevant quantities efficiently. Upon completion of these calculations, all levels, including isomers and triggering states and the transitions among them, are expected to be described consistently within the designated model spaces.

Except for nuclei near shell closures, the majority of nuclei on the nuclear chart exhibit are deformed, posing a significant challenge to the conventional spherical shell model because of the inevitable issue of dimensional explosion. Consequently, the exploration of nuclear structures in heavier, deformed nuclei—where most K-isomers are found—has predominantly relied on deformed mean-field approximations [76]. These models employ the concept of spontaneous symmetry breaking, where the angular momentum—a crucial quantum number for describing nuclear states—is not conserved in the calculations. Over the years, considerable efforts have been dedicated towards advancing beyond mean-field descriptions to develop shell models in which all excited states are exact eigenstates of the angular momentum. It has been emphasized that the angular momentum projection technique is an essential quantum-mechanical tool, with the projected shell model (PSM) [77] emerging as a practical model specifically tailored for the study of K-isomers.

Thus, for the microscopic study of nuclear isomeric states in general, and the NEEC process in particular, two distinct types of shell models are applicable, sharing the same conceptual framework but differing in their implementation. The first is the conventional shell model (CSM) that utilizes a spherical basis. The CSM calculation process is conceptually straightforward: it involves constructing a many-body configuration basis, selecting an appropriate Hamiltonian for this basis, and performing numerical diagonalization [78, 79]. Ideally, such calculations would yield a comprehensive excitation spectrum including low-energy collective states, isomers, and normal states. However, in practice, employing such a CSM to study arbitrarily heavy, deformed nuclei is impractical because of the huge dimensionality of the configuration space and related computational challenges. Even with current computational capabilities, standard CSM calculations are only feasible up to the mass-70 region, where the dimensions of the configuration space can approach one billion. For heavier mass regions, the general application of the CSM is untenable, and only a few selective calculations are possible for nuclei near closed shells.

In contrast, the PSM presents an unconventional approach [77] that significantly diverges from the CSM in both its implementation and targeted nuclei. The PSM utilizes angular momentum projection, which is an effective method for truncating the shell model space that would otherwise be unmanageably large [77]. This methodology—pioneered by Hara and Sun in their early work [80]—has undergone significant evolution over the years, and has been successfully employed in the nuclear spectroscopy of a wide range of isotopes on the nuclear chart [81, 82]. The representative calculations range from light [83] to heavy nuclei [84], and even extend to the superheavy mass region [85-87], thereby providing insights into the anticipated superheavy island of stability. Moreover, the PSM has been utilized in studies of nuclei exhibiting normal and super deformations [86, 87], and in advanced studies on exotic nuclear shapes, including the coexistence of reflection asymmetric and symmetric shapes, as detailed in Ref. [88].

Recently, the PSM has been noticeably expanded to include studies on nuclear-level density [89], marking a milestone where shell model calculations have addressed nuclear levels on the order of 106 per MeV for the first time. Within the PSM framework, it is now feasible to simultaneously explore the properties of nuclear isomers and their associated triggering levels. This expansion may have far-reaching implications for the study of isomers in nuclear astrophysics, particularly in scenarios encountered in nucleosynthesis simulations involving the transmutation of nuclei via nuclear reactions and decays in thermally excited environments. In the absence of sufficient structural information on excited nuclear states, current nucleosynthesis calculations typically adopt one of two approaches to approximate nuclear transmutation rates [90]. The simpler approach neglects excited states and focuses solely on the ground-state properties of nuclei, as exemplified by discussions on neutrino luminosity via the Urca process [91, 92]. Alternatively, some models assume a thermal equilibrium population of excited states, with each state contributing to the overall rate of transmutation based on its thermal population probability [93]. However, as demonstrated by Misch et al. [59], depending on the specific astrophysical environment, nuclear isomers may challenge the validity of these conventional approaches. Notably, Wang et al. provided initial examples [94] demonstrating that the manifestation of isomer effects through the NEEC process is viable. This suggests the need for further investigation into appropriate astrophysical environments.

NEEC in Laser-induced Plasmas

The interactions between photons and matter remain a cornerstone of modern physics. The development of advanced laser technologies, particularly chirped pulse amplification (CPA) [95], has facilitated the creation of environments characterized by ultra-intense and ultra-short electromagnetic fields. When subjected to such fields, target atoms undergo ionization, leading to plasma formation. These plasmas possess electromagnetic fields significantly stronger than those produced by traditional magnetic systems. In such environments, the electrons and ions could be accelerated followed by a series of atomic and nuclear interactions [96-98]. The generated plasmas can achieve extremely high temperatures and densities, which can trigger a complex sequence of nuclear reactions, including the excitation, transformation, and decay of nuclei. Thus, intense laser-matter interaction produces plasmas containing free electrons and various ionic states [7, 19, 71, 99-103].

Laser-induced plasma

The invention of the laser in 1960 was a groundbreaking development, marking the first instance of coherent control over light. This milestone led to rapid advancements in laser technology, notably in the compression of laser pulse durations and the corresponding increase in peak intensities. The proposal and realization of CPA technology have significantly advanced these developments, bringing laser pulse durations into the femtosecond and even attosecond regimes, while dramatically enhancing laser intensities [95]. By 2023, three scientists received the Nobel Prize for their contributions to attosecond-pulse technology [104-106], underscoring the profound impact of this advancement. In contemporary settings, femtosecond laser pulses can achieve focused intensities as high as 1022 W/cm2 in laboratory environments [107-109]. At such high intensities, the oscillating electric field of the laser significantly surpasses the internal electric field of atoms, quickly ionizing them into a plasma state. Consequently, the study of laser-plasma interactions has emerged as one of the most dynamic areas within the field of plasma physics [110].

The acceleration of electrons and ions driven by laser-plasma interactions provides an ideal experimental platform for investigating photon-nucleus and electron-nucleus reactions. These include photon excitation (PE) [111], Coulomb excitation (CE) [112-115], nuclear excitation by electronic transition (NEET) [116-120], electron bridge [12], and photonuclear reaction (γ, n) [7, 121, 122]. While both CE and NEET have been experimentally confirmed, NEET typically exhibits a much smaller cross-section than other processes. The dominant process or processes for nuclear excitation depend critically on specific laser parameters and plasma conditions [99, 123]. Therefore, meticulous calculations, simulations, and experimental investigations are necessary to determine whether NEEC or other competing nuclear excitation mechanisms predominate under particular experimental conditions.

Laser-ablated plasma

Laser ablation on a solid surface is a convenient method for plasma generation. The temperature and density of electrons within this plasma are highly sensitive to both position and time. By combining rough estimates of plasma density and temperature with the cross-sections of each relevant nuclear and electronic process, it is possible to approximate the rates of NEEC, NEET, nuclear excitation by inelastic electron scattering (NEIES), DR, and RR [22, 23, 102].

Subsequent studies have refined the determination of plasma conditions by simulating plasma dynamics from their generation to diffusion. Gunst et al. investigated NEEC processes in a cold, dense plasma environment induced by X-ray free-electron laser pulses irradiating an 93mMo target [124]. Wu et al. investigated NEEC processes in a femtosecond laser-ablated plasma using a comparable target [72, 125]. Variations in laser parameters led to plasmas with different temperatures and densities, which were leveraged in these studies to identify optimal experimental setups for observing the NEEC process. In studies conducted by these researchers, it was emphasized that to effectively induce NEEC events while simultaneously minimizing background noise from processes such as RR and PE, the plasma temperature and density must be maintained at relatively low levels. For instance, laser intensities in the order of 1014–1016 W/cm2 with energy ranges between 10 and 100 mJ are employed to generate plasma, resulting in a cold plasma where the thermal photon flux is insufficient to induce the PE of the nucleus, suppressing the NEIES process [72, 126, 127]. Concurrently, the nuclear energy gap should be appropriately low, on the order of several keV, which aligns with the region of cold plasma that corresponds to the highest density of electron energies. Examples include the 1.565 keV transition in 201Hg, 1.642 keV transition in 193Pt, 2.329 keV transition in 205Pb, and 4.821 keV transition in 151Sm, as listed in Ref. [128].

In cases where secondary X-rays are generated via inner-shell processes, such as those noted in Ref. [72], it must be ensured that the plasma density remains sufficiently low to maintain the stability of inner-shell vacancies, as higher densities would lead to rapid depletion of these vacancies due to RR processes.

Borisyuk et al. conducted an experiment focusing on the isomeric excitation of 229Th utilizing a Nd:YAG laser to ablate a Th:SiO2 target containing 6.8% of 229Th [19]. They measured the energy levels and half-life of the generated 229Th isomer. Their theoretical calculations showed that nuclear excitation was induced by the NEEC process. However, the study did not provide detailed analyses to rule out other nuclear excitation mechanisms, leaving it unclear whether NEEC was indeed the dominant mechanism in this scenario.

Laser-heated cluster

The interaction between intense laser pulses and atom clusters offers a unique plasma environment that is well-suited for verifying NEEC [129]. Qi et al. proposed a method using laser-cluster interactions to excite 229Th from its ground state to its isomeric state [127]. Their calculations indicated that isomeric excitation was primarily driven by NEEC and NEIES. By adjusting the laser intensity, it was possible to continuously tune between NEEC and NEIES, providing an approach to confirm the NEEC.

Laser-heated clusters, although nanometer-sized plasmas, exhibit characteristics distinct from those of ablation plasma plumes. First, cluster nanoplasmas possess simpler plasma characteristics and dynamics, allowing more effective characterization. Second, they exhibit significantly higher electron densities, which highlight the importance of NEEC and NEIES over other mechanisms. To further isolate the NEEC, specific laser intensities can be employed to emphasize the NEEC while minimizing the contribution from the NEIES. Recently, Qi et al. demonstrated that the interaction between intense laser pulses and 235U clusters provides an ideal system in which the NEEC process accounts for over 99.9% of the nuclear isomeric excitation [126].

Pros and cons of using laser-ablated plasma

Here, we outline the advantages and disadvantages of verifying NEEC using laser-generated plasmas. The advantages include the following:

(i) Laser-generated plasmas provide a relatively well-controlled experimental environment in which plasma parameters, such as temperature, density, and composition, can be precisely adjusted and quantitatively measured, facilitating systematic investigations of NEEC under controlled environmental conditions.

(ii) The ability of laser-generated plasmas to achieve certain temperatures and densities increases the likelihood of NEEC occurrences, providing a suitable setting for the observation and study of this phenomenon.

(iii) Laser-generated plasma experiments enable the exploration of a wide energy range relevant to NEEC. This capability allows the investigation of various nuclear systems and energy regimes (e.g., 8 eV for 229Th, 76 eV for 235U, and 4.8 keV for 93Mo) by adjusting laser parameters.

The disadvantages of employing laser-generated plasmas for investigating NEEC include the following:

(i) The lifespan of laser-generated plasmas is short because of rapid cooling and expansion, and restricts the temporal window available for NEEC occurrences, potentially limiting the experimental observation and analysis of the process.

(ii) Laser-generated plasmas allow multiple nuclear excitation mechanisms, such as NEEC, NEIES, NEET, and optical excitations. For instance, in cluster nanoplasmas, nuclear excitation predominantly arises from NEEC and NEIES, while in plasmas generated by more intense lasers, NEET may predominate. Therefore, detailed calculations are imperative to determine optimal laser parameters to emphasize NEEC over competing processes.

(iii) Interactions within a laser-plasma environment can introduce additional effects such as electron heating, ionization, and charge screening, each of which can influence nuclear excitation processes. Accurate simulations and accounting for these effects are necessary to approximate the actual conditions within the plasma.

NEEC Studies with Vortex Beams

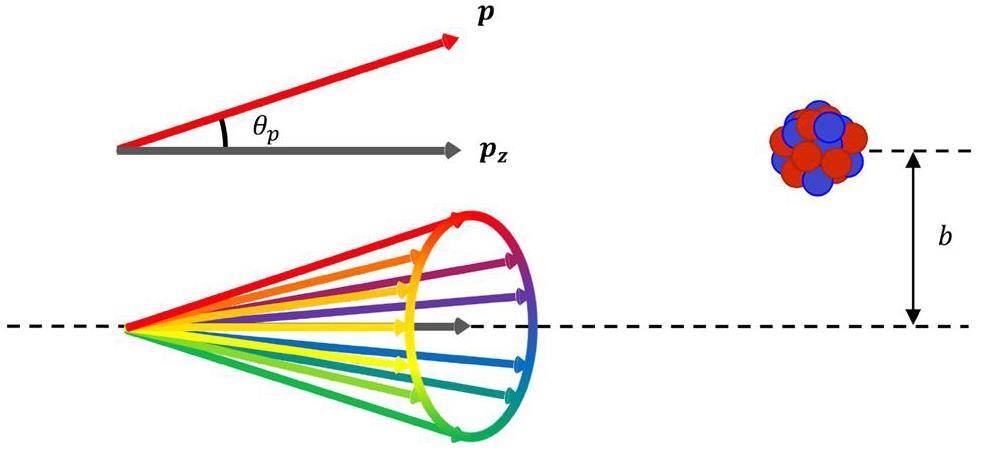

Vortex light beams (Fig. 3), first proposed in the 1990s [42], represent a transformative development in photonics. These beams are characterized by photons that carry not only intrinsic spin angular momentum but also OAM. The inclusion of intrinsic OAM introduces a new degree of freedom, distinguishing vortex states from traditional plane-wave states and inspiring the extensive exploration of novel phenomena in atomic and nuclear physics. For instance, theoretical studies on the photodisintegration of deuterons using twisted photons were discussed in Ref. [130, 131]. These studies examined the dependence of the photodisintegration cross-section on the impact parameter b, i.e., the distance between the target nucleus and vortex beam axis. These studies also identified the increased threshold energy required for the reaction, along with interesting features of selection rules for small-impact parameters. Similarly, hadron excitation induced by vortex photons was analyzed in Ref. [132]. More recently, theoretical studies on giant multipole resonances in nuclei induced by vortex γ-photons were presented in Ref. [133, 134]. These investigations highlight the potential for manipulating the excitation of giant multipole resonances by vortex γ-photons, facilitating transitions that are otherwise forbidden or enabling quasi-pure transitions, provided that the nucleus is precisely aligned with the vortex beam axis [133].

Recent advancements in fabricating phase masks with nanometer-level precision have enabled unprecedented control over the coherent superposition of matter waves, facilitating the generation of vortex beams with chiral wave-function spatial profiles that carry the OAM [135-139]. By imparting chirality to massive particles, vortex beams have been proposed as novel tools for studying [39-41, 44, 140] and even manipulating [138, 141-143] the structural properties of neutrons, protons, ions, and their associated particle and nuclear processes. Electron vortex beams—among the most extensively studied massive-particle vortex beams—have been experimentally realized using various techniques such as holographic gratings, phase plates, magnetic monopole fields, and chiral plasmonic near fields [39-41, 44, 135-137]. These beams achieved angular momenta as high as

The potential of vortex electrons to advance nuclear physics has been extensively discussed in Refs. [40, 41, 41, 143]. In particular, the possibility of manipulating nuclear excitation via vortex electrons has been studied theoretically in the context of NEEC [36].

The NEEC cross-section with a vortex electron beam is expressed as [36]

The recombination orbital of the electron and nuclear transition multipolarity determine the selection rules governing the angular momentum components of the incoming electron participating in the NEEC process. For plane-wave electrons, the wave function has a fixed partial-wave expansion across all multipoles. However, vortex electrons can be intentionally shaped to enhance the NEEC efficiency [36]. By analyzing isomer depletion in 93mMo and 152mEu, representative of E2 and M1 nuclear transitions, respectively, Ref. [36] demonstrates that vortex electrons with a suitable opening angle and quantum number for the OAM, and precise control of the distance between the ion and electron vortex axis, could significantly alter the isomer-depletion rate. These results highlight new possibilities for the dynamical control of isomer depletion and other nuclear processes.

It is important to emphasize that the remarkable features observed in nuclear processes involving vortex photons and electrons rely on the highly precise positioning of the nucleus relative to the vortex axis, at a scale comparable to the photon wavelength or the inverse transverse momentum of the vortex particle. This behavior has also been observed in studies of vortex photon interactions with atomic systems [43, 44, 144-147]. However, the typical energy scale of nuclear processes, which ranges from keV to several MeV, makes achieving such precision a significant experimental challenge [41]. The use of cold neutron vortex beams may reduce these experimental challenges, allowing the exploration of the intriguing features of vortex particles in nuclear processes [41, 130, 148, 149]. Nonetheless, further research is required to develop methods that relax these stringent conditions while enabling the observation of these features, particularly in the context of the NEEC process. Advancements in this area would be crucial for applications of vortex particles in the manipulation of nuclear processes via the coupling of nuclear and electronic degrees of freedom.

NEEC Studies Based on Accelerators

Another approach for studying NEEC in laboratory settings involves the use of accelerators where high-energy beams of highly charged ions are generated.

By Using a Storage Ring

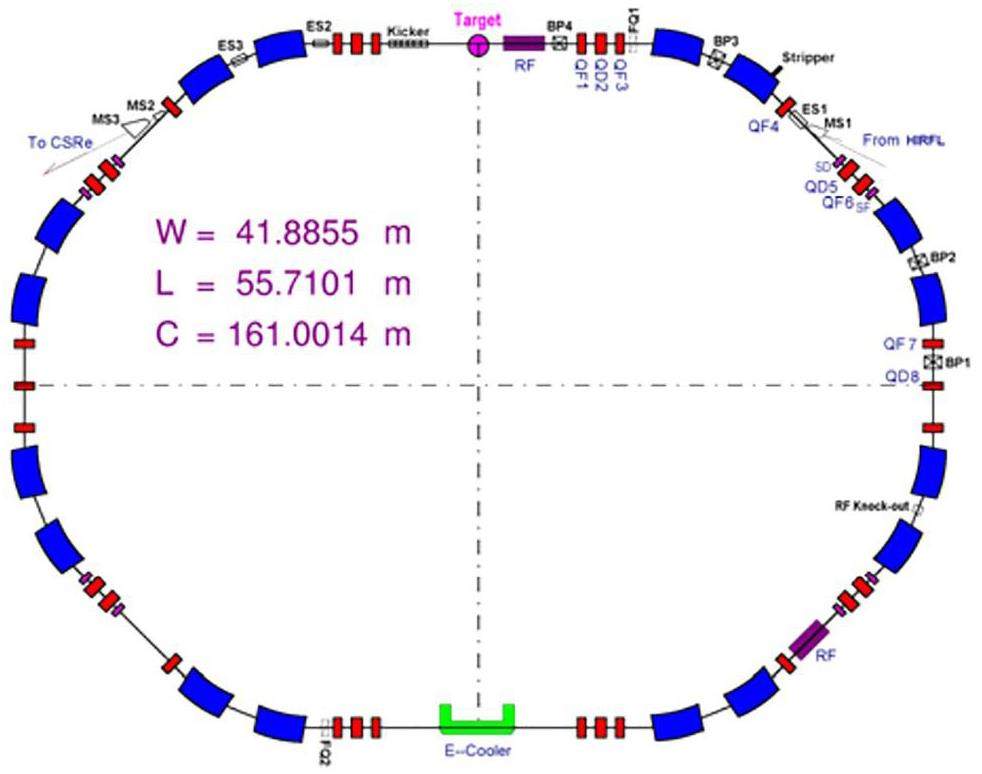

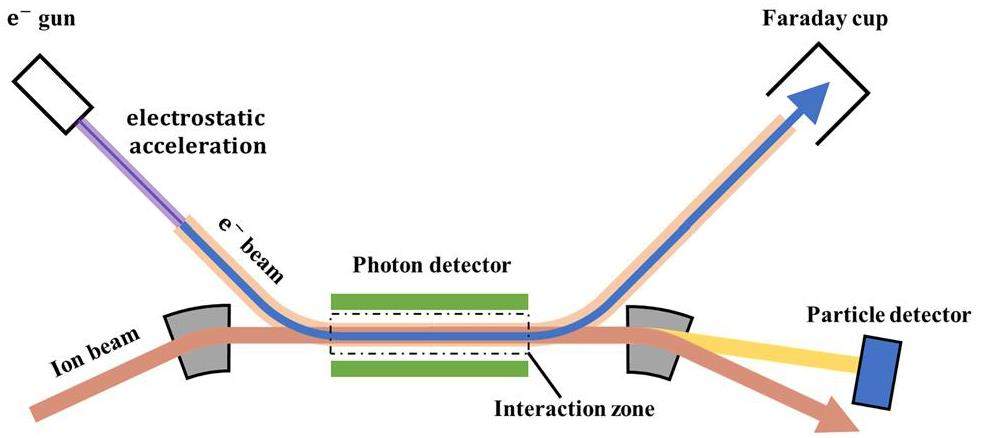

In a cooling storage ring, as illustrated in Fig. 4, a cooling electron beam is employed for ion-beam stability. This configuration facilitates electron-ion interaction experiments, which will enable the observation of the NEEC process. A heavy-ion storage ring provides an ideal experimental environment, in which relatively long-lived isomers interact with electron beams under controlled conditions, analogous to those in DR experiments [150-152].

Palffy et al. proposed an experimental method for spatially separating photon emissions based on different timescales of the RR and NEEC processes, while also providing theoretical insights for enhancing the resonance strength of NEEC by introducing fast electronic X-ray decay [33]. In this approach, the RR process emits a photon within 10-15 s, whereas the NEEC process emits the photon after the excited nucleus with time-scale of ns ~ μs. This temporal separation enables relatively pure confirmation of NEEC events through the detection of delayed photons.

A primary challenge in implementing this method is the efficient capture of excited isomers. Constructing a detector that encompasses the full circumference to capture all the emitted photons would be prohibitively expensive. Consequently, it is crucial to develop cost-effective techniques, such as coincidence detection, to enhance the efficiency of capturing these rare events [154]. As shown in Fig. 5, Yang et al. described the NEEC process that occurs within the interaction zone, where the circulating ion beam in the CSR interacts with an electron beam originally employed for beam stabilization. A photon detector array was positioned around the interaction zone, while ions—whose charge states were altered owing to the occurrence of NEEC or RR processes—were subsequently collected by a particle detector. The NEEC and RR events can be distinguished from each other by the emission time.

Adding another electron beam into storage rings, such as the High Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility [155], holds significant promise for advancing NEEC experimental studies. This approach enables more precise and efficient detection methodologies, significantly expanding the range of isomers available for investigation compared with laser-induced plasma systems. The tunable energy of the electron beam offers enhanced control over resonance conditions, allowing access to a broader spectrum of nuclear energy levels.

By Using Ion Beams

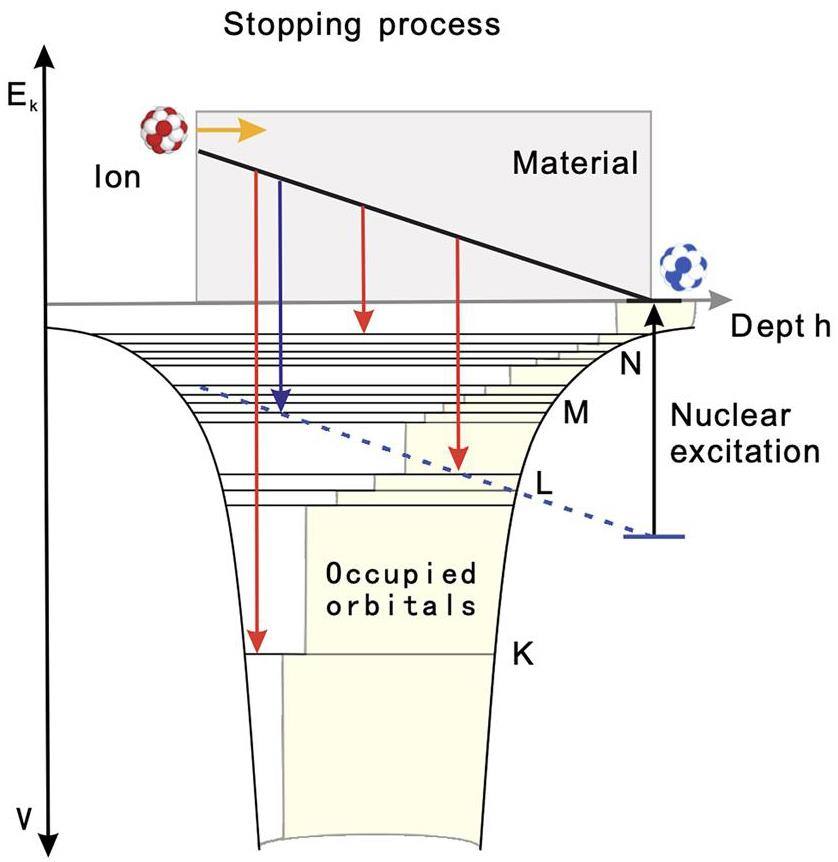

When an ion beam is directed toward a solid target, the ions traverse the material and undergo continuous changes in direction and energy. Simultaneously, their excitation and ionization states may vary because of processes such as electron capture or loss [156-159]. Typically, as the velocity of ions decreases, their average charge state also diminishes. This variation depends significantly on the properties of the target material. During the stopping process, NEEC channels progressively close, beginning with outer orbitals and moving inward, as shown in Fig.6. For a given orbital, the resonance condition on energy is satisfied at a specific point during the stopping process. If the orbital is not firmly occupied, the corresponding NEEC channel can be activated during the stopping process.

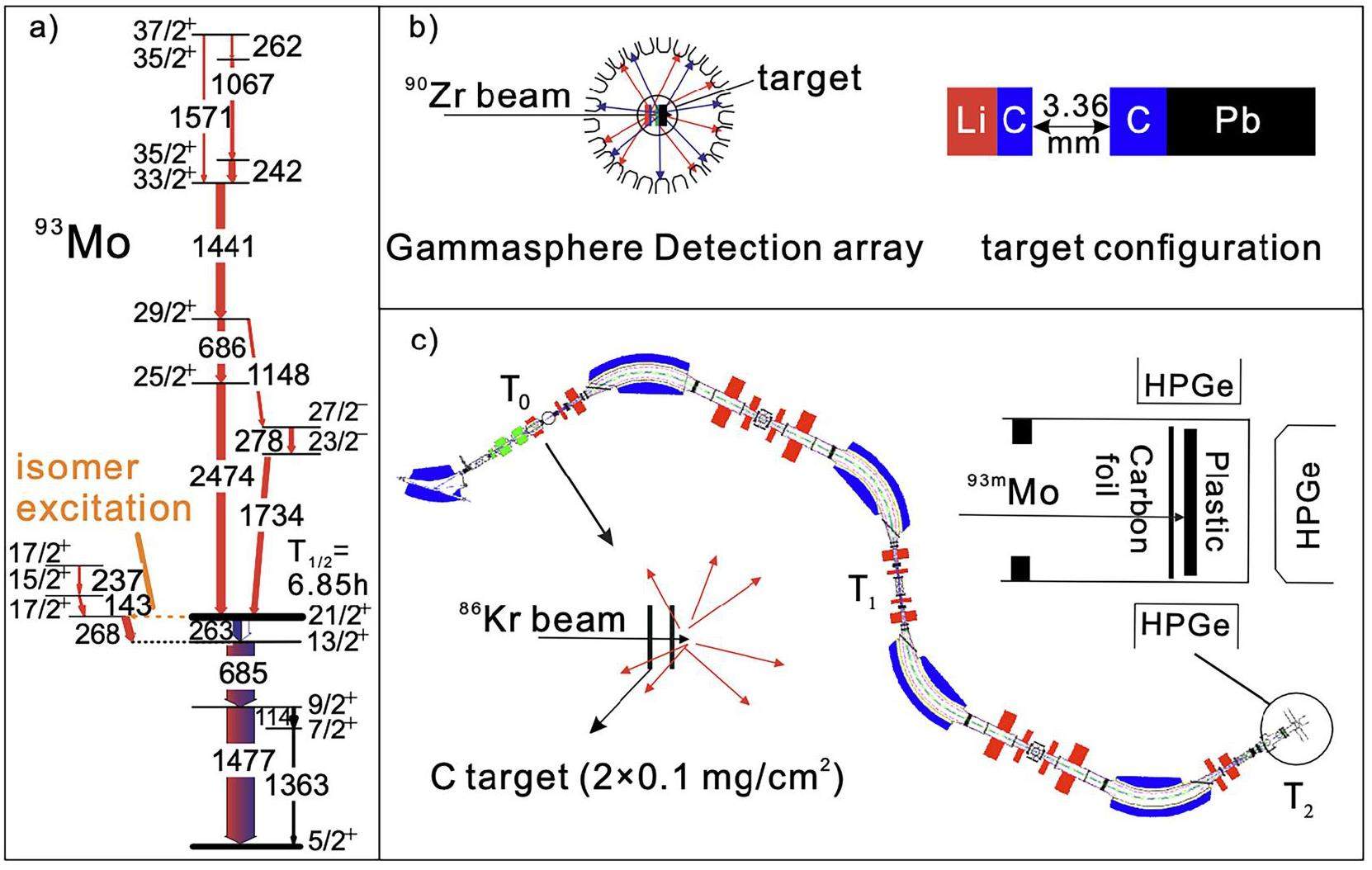

The number of active NEEC channels depends on the energy gap between the isomeric and triggering states. Therefore, the NEEC probability can vary significantly among different isomers. Based on theoretical predictions, several isomers have been proposed as candidates for experimental measurements. Among these, 93mMo has attracted significant attention because of its favorable properties. This isomer has an excitation energy of 2425 keV, a half-life of 6.85 h, and spin and parity of 21/2+, as shown in Fig. 7a. A triggering state with 17/2+ lies just 4.8 keV above the isomeric state and has a half-life of 3.5 ns.

The first experimental observation of NEEC was reported by Chiara et al., with a probability of 0.010(3) for 93mMo ions interacting with a carbon foil [17]. The measurements were conducted at the ATLAS facility at Argonne National Laboratory, utilizing the Gammasphere array to detect γ-rays, as shown in Fig.7b. In the experiment, 93mMo ions were produced at the 7Li target bombarded by a 90Zr beam with an energy of 840 MeV, implanted in a carbon foil located 3 mm away from the primary target, and finally stopped in the lead backing. The NEEC process was hypothesized to occur within the carbon foil, leading to the coincidence detection of γ-rays above the isomeric state and those below the triggering state. The γ-rays from states above the isomeric level exhibited Doppler shifts owing to the ionic motion, while those below the triggering state did not, as the ions stopped in the carbon and lead layers within a few picoseconds—a duration much shorter than the half-life of the triggering state.

From numerous triple- or higher-fold coincidence events, the coincidence between the 268 keV transition depopulating the triggering state and the transitions above the 21/2+ isomer was determined to be valid. Based on these results, a depletion probability of 0.010(3) was deduced. However, subsequent theoretical studies were unable to reproduce such a large probability; instead, they predicted a much smaller value of approximately 10-11 [31].

Later, it was noted that the handling of the background in this experiment may have been overly idealized, potentially leading to an overestimation of the extracted NEEC probability. In a reply, Chiara et al. argued that the random coincidence could only contribute approximately 0.0008 to the reported probability, and the possible contamination of the reported spectra could be explained with some unpublished information [160].

To address the controversy surrounding the NEEC probability, another independent experiment was conducted at the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou, as shown in Fig.7c [18]. In this experiment, an 86Kr beam with an energy of 559 MeV was directed onto a carbon target positioned at T0 of the secondary radioactive ion-beam line (RIBLL) in Lanzhou. The resulting 93mMo ions were transported by RIBLL to the detection station located at T2, and stopped in a plastic scintillator. The NEEC of 93mMo ions was anticipated to occur during their deceleration in a 20μm-thick carbon foil located in front of the plastic scintillator. γ-rays emitted from the NEEC process and subsequent isomeric transitions were detected by five Compton-suppressed high-purity germanium detectors surrounding the plastic scintillator, while the prompt γ-rays from the primary fusion-evaporation reactions were emitted at T0 and did not contribute to the background of the measurement. The NEEC of 93mMo was not observed in this experiment, with an upper limit of the NEEC probability of 2×10-5.

However, the recoiling energy in the latter experiment was considerably lower, and the stopping materials differed between the two experiments. Consequently, the debate persists from both experimental and theoretical perspectives. Further experiments are required to provide conclusive evidence to resolve these discrepancies.

By Using Electron Beams

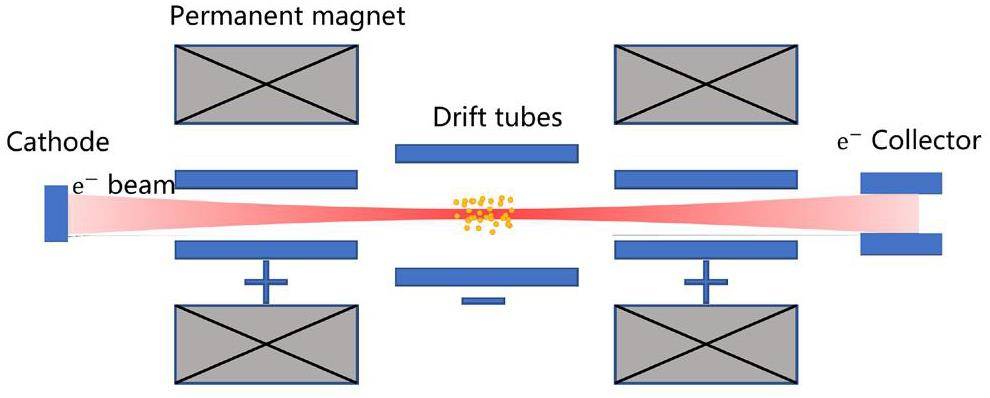

Because NEEC is a resonant process, the selection and preparation of appropriate energy levels and ion charge states are critical for its successful observation. An EBIT offers an alternative environment for these studies by providing a tunable electron beam and well-confined, highly charged ions.

In an EBIT, ions are confined within a narrow spatial region, primarily centered around the electron beam, as shown in Fig. 8. The electron-beam density ranged from approximately 1010 to 1012 cm-3. The equilibrium charge state of the ions can be controlled by adjusting key parameters such as the electron-beam energy, axial magnetic field, and the presence of neutral atoms in the trap region, as detailed in [161].

In Ref. [35], Ringuette conducted simulations of the NEEC process at the TITAN setup to excite 129mSb (

In the experimental setups proposed by these researchers, NEEC events were confirmed by detecting the photons emitted through an observation window around the drift tubes. As noted by Wang et al., the differentiation between NEEC events and background signals, particularly those from the RR process, relies primarily on their distinct angular distributions. Developing a more comprehensive approach for detection and discrimination, along with further optimization of experimental conditions, remains an active area of investigation.

The NEEC counting rate is significantly affected by the energy distribution of the electron beam in the EBIT [35]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that NEEC signals can be effectively distinguished from the RR background only when the experimental conditions, particularly the electron beam, are well defined [27].

Summary

The NEEC process, along with its inverse process of IC, represents a unique interaction that involves both atomic and nuclear structures. NEEC and IC are closely related to the excitation or de-excitation of nuclear isomeric states, with implications for technological applications and fundamental physics, including nuclear batteries, nuclear clocks, and nucleosynthesis in astrophysical environments.

Since its theoretical proposal in 1976, NEEC has attracted considerable attention from the scientific community. Several researchers in related fields have suggested that NEEC could play a significant role in astrophysical environments and plasma physics. In astrophysics, NEEC could extend the reaction chains of neutron-capture processes, potentially altering the isotopic abundances in stellar and cosmic contexts. In plasma environments, NEEC could influence the population balance of atomic nuclei and their associated isomers.

Nevertheless, despite its theoretical potential, experimental verification of NEEC has remained a formidable challenge. Key challenges include the high background noise inherent in experimental environments, whether in laser-induced plasmas or particle accelerators. In these settings, the NEEC cross-section is small compared to other competing electromagnetic interactions, such as CE and RR, complicating the task of isolating NEEC signals from substantial noise. Efforts to enhance NEEC rates and mitigate background interference continue to be an active research area.

In the selection of experimental setups and the design of experimental schemes, researchers such as Gunst, Wu, and Qi have explored optimal laser parameters and plasma properties to enable NEEC in laser-induced plasmas. They suspected that using low-energy-density lasers on solid targets to generate cold, low-density plasmas could effectively reduce noise and enhance the occurrence and detection of NEEC events. In plasma environments, the detection scheme for NEEC using X-rays tends to focus on nuclei or isomers with low gaps above, typically in the eV to keV range. However, researchers such as Pálffy, Chiara, Ringuette, and Wang have focused on demonstrating that precise energy control via electron or ion beams can improve the efficiency of NEEC, thereby reducing the influence of noise. They employ techniques such as storage rings, ion-beam interactions with solids, and electron-beam interactions with plasmas, which significantly expand the range of selectable nuclear energy levels. In particular, if dual electron beams are used in a storage ring or EBIT setup, the efficiency of reactions can be enhanced while maintaining the stability of the ion beam in the storage ring or plasmas in the EBIT. However, these methodologies require further refinement and development in future experimental setups.

In addition, it should be noted that owing to the inherent properties of nuclear transition selection rules, higher-order multipole transitions are typically suppressed, resulting in insufficient reaction cross-sections. Wang et al. introduced vertex beams into the study of NEEC and developed a theoretical framework for their application. Owing to the OAM carried by vortex beams, traditional selection rules are broken, enabling the occurrence of higher-order multipole transitions. Thus, the successful generation of high-intensity vortex beams in laboratory environments represents a significant breakthrough, potentially advancing the study of nuclear excitation processes.

Designing experiments that effectively eliminate background noise and enable the discovery of NEEC remain an active area of research. Successfully confirming NEEC would mark a significant breakthrough in our understanding of nuclear processes, paving the way for advancements in both fundamental research and practical applications.

On the excitation of isomeric nuclear levels by laser radiation through inverse internal electron conversion

. Physics Letters B 62, 393 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(76)90665-1The calculation of internal conversion coefficients

. Physical Review 55, 122 (1939). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.55.122The theory of internal conversion

. Physical Review 83, 399 (1951). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.83.399Nuclear structure effects in internal conversion

. Annual review of nuclear science 10, 193-234 (1960). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ns.10.120160.001205Plasma astrophysics and modern plasma cosmology

. Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics 47, 490-535 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chinastron.2023.09.003Total body pet: Why, how, what for?

IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 4, 283-292 (2020).Photonuclear production of nuclear isomers using bremsstrahlung induced by laser-wakefield electrons

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 74 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01219-xA study of nuclear structure for 244Cm, 241Am, 238Pu, 210Po, 147Pm, 137Cs, 90Sr and 63Ni nuclei used in nuclear battery

. Modern Physics Letters A 32,Induced acceleration of the decay of the 31-yr isomer of 178m2Hf using bremsstrahlung radiation

. Physics Letters B 750, 89-94 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2015.08.051Electron recombination as a way of deexciting the 129mSb isomer

. Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Physics 84, 1207-1209 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3103/S1062873820100135Scheme for the excitation of thorium-229 nuclei based on electronic bridge excitation

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 24 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01169-4Populating 229mTh via two-photon electronic bridge mechanism

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 59 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00900-3Isomer triggering via nuclear excitation by electron capture

. Physical review letters 99,Nuclear excitation by target electron capture

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 40, 25-27 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-583X(89)90914-2First-principles calculation of the cross sections for nuclear excitation by electron capture of channeled nuclei

. Physical Review C 47, 323 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.47.323Isomer depletion as experimental evidence of nuclear excitation by electron capture

. Nature 554, 216-218 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25483Probing 93mMo isomer depletion with an isomer beam

. Physical Review Letters 128,Excitation of 229Th nuclei in laser plasma: the energy and half-life of the low-lying isomeric state

. arXiv:1804.00299Feasibility study of nuclear excitation by electron capture using an electron beam ion trap

. Frontiers in Physics 11,. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1203401Self-consistent description for x-ray, auger electron, and nuclear excitation by electron transition processes

. Physical Review C 48, 2277 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.48.2277Mechanisms of nuclear excitation in plasmas

. Physical Review C 59, 2462 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.2462Enhanced nuclear level decay in hot dense plasmas

. Physical Review C 70,Theory of nuclear excitation by electron capture for heavy ions

. Physical Review A 73,Cross sections for radiative recombination and the photoelectric effect in the K, L, and M shells of one-electron systems with 1 ≤ z ≤ 112 calculated within an exact relativistic description

. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 74, 1-121 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.1999.0825Quantum interference between nuclear excitation by electron capture and radiative recombination

. Physical Review A 75,Nuclear effects in atomic transitions

. Contemporary Physics 51, 471-496 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/00107514.2010.493325Possible depletion of isomers in perturbed atomic environments

. Laser physics 20, 977-984 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1054660X10090355Calculated yield of isomer depletion due to neec for 93mMo recoils

. Physics of Atomic Nuclei 75, 1362-1367 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778812110117Mo 93 m isomer depletion via beam-based nuclear excitation by electron capture

. Physical review letters 122,Novel approach to mo 93 m isomer depletion: Nuclear excitation by electron capture in resonant transfer process

. Physical Review Letters 127,Nuclear excitation by electron capture followed by fast x-ray emission

. Physics Letters B 661, 330-334 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2008.02.027Nuclear excitation by electron capture in excited ions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Towards nuclear excitation via electron capture in an electron beam ion trap

. Ph.D. thesis,Dynamical control of nuclear isomer depletion via electron vortex beams

. Physical Review Letters 128,Optical vortices 30 years on: Oam manipulation from topological charge to multiple singularities

. Light: Science & Applications 8, 90 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-019-0194-2Transverse and longitudinal angular momenta of light

. Physics Reports 592, 1-38 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.06.003Electron vortices: Beams with orbital angular momentum

. Reviews of Modern Physics 89,Theory and applications of free-electron vortex states

. Physics Reports 690, 1-70 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2017.05.006Promises and challenges of high-energy vortex states collisions

. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 127,Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of laguerre gaussian laser modes

. Physical review A 45, 8185 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.45.8185Transfer of optical orbital angular momentum to a bound electron

. Nature communications 7, 12998 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12998Excitation of an electric octupole transition by twisted light

. Physical Review Letters 129,Study of nuclear structure by electromagnetic excitation with accelerated ions

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 28, 432-542 (1956). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.28.432Theory of nuclear excitation by electron capture for heavy ions

. Ph.D. thesis,Coupling highly excited nuclei to the atomic shell in dense astrophysical plasmas

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Long live isomer research

. Nature Physics 1, 81-82 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys150Atlas of nuclear isomers-second edition

. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 150,Excited nuclear states and k-isomers in the projected shell model

. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 233, 1037-1045 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-024-01095-5Nuclear structure and the search for induced energy release from isomers

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 261, 960-964 (2007).Nuclear metastables for energy and power: status and challenges

. Innovations in Army Energy and Power Materials Technologies 36, 289 (2018).Isomer depletion

. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 233, 1151-1160 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-024-01149-8Manipulation of nuclear isomers with lasers: mechanisms and prospects

. Science Bulletin 67, 1526-1529 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2022.06.020Nuclear data sheets for A = 81

. Nucl. Data Sheets 109, 2257-2437 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2008.09.001Accelerated emission of gamma rays from the 31-yr isomer of 178Hf induced by x-ray irradiation

. Phys. Rev. Lett 82, 695 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.695Search for x-ray induced decay of the 31-yr isomer of 178Hf using synchrotron radiation

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Search for low-energy induced depletion of 178Hfm2 at the spring-8 synchrotron

. Phys. Lett. B 679, 203-208 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.07.025Astromers: nuclear isomers in astrophysics

. Astrophys. J. Supp. Ser. 252, 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/abc41dBig bang nucleosynthesis: Present status

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88,Astromers: status and prospects

. Eur. Phys. J. Sp. Top. 233, 1075-1099 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-024-01136-zOrigin of the elements

. Astro. Astrophys. Rev. 31, 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00159-022-00146-xPrimordial Nucleosynthesis Redux

. Astrophys. J. 376, 51 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1086/170255Primordial nucleosynthesis: theory and observations

. Phys. Rep. 333–334, 389-407 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(00)00031-4Big bang nucleosynthesis

. Nucl. Phys. A 777, 208-225 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2004.10.033Modification of nuclear transitions in stellar plasma by electronic processes: K isomers in 176Lu and 180Ta under s-process conditions

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Nuclear excitation by electron capture in stellar environments

. (2011)Nuclear reactions in astrophysical plasmas

. Ph.D. thesis,Characteristics of the 21/2+ isomer in 93Mo: Toward the possibility of enhanced nuclear isomer decay

. Phys. Lett. B 696, 197-200 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2010.10.065Nuclear excitation by electron capture in optical-laser-generated plasmas

. Phys. Rev. E 97,X-ray-assisted nuclear excitation by electron capture in optical laser-generated plasmas

. Phys. Rev. A 100,The mean-field theory of nuclear structure and dynamics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 54, 913-1015 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.54.913The shell model as a unified view of nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 427-488 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.77.427Evolution of shell structure in exotic nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92,Projection techniques to approach the nuclear manybody problem

. Phys. Scripta 91,Monte carlo shell model studies with massively parallel supercomputers

. Phys. Scripta 92,Projected shell model and high-spin spectroscopy

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 4, 637-785 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301395000250High spin spectroscopy with the projected shell model

. Phys.Rep. 264, 375-391 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(95)00049-6Fortran code of the projected shell model: feasible shell model calculations for heavy nuclei

. Comput.r Phys. Commun. 104, 245-258 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(97)00064-7Backbending mechanism of 48Cr

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1922 (1999)Scissors-mode vibrations and the emergence of su (3) symmetry from the projected deformed mean field

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 672 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1922Nuclear isomers in superheavy elements as stepping stones towards the island of stability

. Nature 442, 896-899 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05069Theoretical constraints for observation of superdeformed bands in the mass-60 region

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 686 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.686Systematic description of yrast superdeformed bands in even-even nuclei of the mass-190 region

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 2321 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.2321Coexistence of reflection asymmetric and symmetric shapes in 144Ba

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Projected shell model description of nuclear level density: Collective, pair-breaking, and multiquasiparticle regimes in even-even nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Sensitivity of neutron-rich nuclear isomer behavior to uncertainties in direct transitions

. Symmetry 13, 1831 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13101831Strong neutrino cooling by cycles of electron capture and ? - decay in neutron star crusts

. Nature 505, 62-65 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12757Urca cooling pairs in the neutron star ocean and their effect on superbursts

. Astrophys. J. 831, 13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3847/0004-637X/831/1/13Stellar weak-interaction rates for sd-shell nuclei. I-nuclear matrix element systematics with application to Al-26 and selected nuclei of importance to the supernova problem

. Astrophys. J. Supp. Ser. 42, 447-447 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1086/190657Urca cooling in neutron star crusts and oceans: Effects of nuclear excitations

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Compression of amplified chirped optical pulses

. Opt.Commu. 56, 219-221 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4018(85)90120-8The interaction of high-power lasers with plasmas

. Plasma Phys. Controll. Fus. 45, 181 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1088/0741-3335/45/2/701Review of laser-driven ion sources and their applications

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75,Laserdriven ion and electron acceleration from near-critical density gas targets: Towards high-repetition rate operation in the 1 pw, sub-100 fs laser interaction regime

. Phys. Rev. Res. 6,Quantum theory of isomeric excitation of 229Th in strong laser fields

. Phys. Rev. Res. 5,Electric-dipole-forbidden nuclear transitions driven by super-intense laser fields

. Phys. Rev. C 77,α decay in extreme laser fields within a deformed gamow-like model

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01371-ySpatial and spectral measurement of laser-driven protons through radioactivation

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 183 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01324-xEffective extraction of photoneutron cross-section distribution using gamma activation and reaction yield ratio method

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 170 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01330-zTheory of highharmonic generation by low-frequency laser fields

. Phys. Rev. A 49, 2117-2132 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.49.2117Attosecond metrology

. Nature 414, 509-513 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/35107000Observation of a train of attosecond pulses from high harmonic generation

. Science 292, 1689-1692 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059413Generation and characterization of the highest laser intensities (1022W/cm2)

. Opt. lett. 29, 2837-2839 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.29.002837Generation of 1011 contrast 50 TW laser pulses

. Opt. Lett. 31, 1456-1458 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.31.001456Ultra-high intensity-300-TW laser at 0.1 Hz repetition rate

. Opt. Exp. 16, 2109-2114 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.16.002109Accelerated emission of gamma rays from the 31-yr isomer of 178Hf induced by x-ray irradiation

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 695-698 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.695High-energy electron scattering and nuclear structure determinations

. Phys. Rev. 92, 978 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.92.978Excitation of 229mTh at inelastic scattering of low energy electrons

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Nuclear excitation cross section of 229Th via inelastic electron scattering

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Isomeric excitation of 235U by inelastic scattering of low-energy electrons

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Nuclear excitation by electron transition and its application to uranium 235 separation

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 49, 1574-1586 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.49.1574Nanosecond stroboscopic electron spectroscopy for observation of nuclear excitation by electron transition (NEET) in 197Au

. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys 24, 1703 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.24.1703Nuclear excitation in atomic transitions (NEET process analysis)

. Nucl. Phys. A 539, 209-222 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(92)90267-NObservation of nuclear excitation by electron transition in 197Au with synchrotron x rays and an avalanche photodiode

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1831 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1831Elements and their transitions feasible for NEET

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tables 91, 1-7 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2005.07.002Photo-excitation production of medically interesting isomers using intense ?-ray source

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 168,A general framework for describing photofission observables of actinides at an average excitation energy below 30 MeV*

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Theory of isomeric excitation of 229Th via electronic processes

. Front. Phys. 11,Dominant secondary nuclear photoexcitation with the x-ray free-electron laser

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112,Tailoring laser-generated plasmas for efficient nuclear excitation by electron capture

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120,Laser-based approach to verify nuclear excitation by electron capture

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Isomeric excitation of 229Th in laserheated clusters

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Cooperative effects in nuclear excitation with coherent x-ray light

. New J. Phys 14,Femtosecond pumping of nuclear isomeric states by the coulomb collision of ions with quivering electrons

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Radiative capture of cold neutrons by protons and deuteron photodisintegration with twisted beams

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 45,Recoil momentum effects in quantum processes induced by twisted photons

. Phys. Rev. Res. 3,Delta baryon photoproduction with twisted photons

. Annalen der Physik 534,Manipulation of giant multipole resonances via vortex γ photons

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Excitation of multipolar transitions in nuclei by twisted photons

. Phys. Atom. Nucl. 87, 561-569 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778824700364Generation of electron beams carrying orbital angular momentum

. Nature 464, 737-739 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08904Production and application of electron vortex beams

. Nature 467, 301-304 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09366Electron vortex beams with high quanta of orbital angular momentum

. Science 331, 192-195 (2011)Controlling neutron orbital angular momentum

. Nature 525, 504-506 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15265Vortex beams of atoms and molecules

. Science 373, 1105-1109 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj2451Decay of the vortex muon

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Twisting neutrons may reveal their internal structure

. Nat. Phys. 14, 1-2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4322xSelf-accelerating dirac particles and prolonging the lifetime of relativistic fermions

. Nat. Phys. 11, 261-267 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3196The quantum future of microscopy: Wave function engineering of electrons, ions, and nuclei

. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116,Optical angular momentum and atoms

. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 375,Atomic spectroscopy with twisted photons: Separation of M1 − E2 mixed multipoles

. Phys. Rev. A 97,Experimental verification of position-dependent angular-momentum selection rules for absorption of twisted light by a bound electron

. New J. Phys. 20,Modification of multipole transitions by twisted light

. Phys. Rev. A 100,Schwinger scattering of twisted neutrons by nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Elastic scattering of twisted neutrons by nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 103,KLL dielectronic recombination resonant strengths of He-like up to O-like xenon ions

. Phys. Rev. A 81,Giant retardation effect in electronelectron interaction

. Phys. Rev. A 105,Absolute dielectronic recombination rate coefficients of highly charged ions at the storage ring CSRm and CSRe

. Chin. Phys. B 32,Overview on the HIRFLCSR facility

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E-nucl. Phys. 18, 405-410 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301309012446Feasibility of probing the NEEC process using storage rings

. Front. Phys. 12,Status of the high-intensity heavyion accelerator facility in china

. AAPPS Bull. 32, 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-022-00064-1Interaction of slow, very highly charged ions with surfaces

. Prog. Surf. Sci. 61, 23-84 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6816(99)00009-XLaser generated proton beam focusing and high temperature isochoric heating of solid matter

. Phys. Plasmas 14,Equilibrium and nonequilibrium charge-state distributions of 2 MeV/u sulfur ions passing through carbon foils

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B: Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 267, 2675-2679 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2009.05.035The charge exchange of slow highly charged ions at surfaces unraveled with freestanding 2D materials

. Surf. Sci. Rep. 77,Reply to: Possible overestimation of isomer depletion due to contamination

. Nature 594, E3-E4 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03334-4Upgrade of the electron beam ion trap in Shanghai

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 85,