Introduction

Experiments involving heavy-ion collisions at ultra-relativistic energies, conducted at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), aim at studying a new state of matter known as the quark–gluon plasma (QGP) [1-4]. Viscous hydrodynamics is remarkably successful at describing a wide range of observables and has become the “standard model” for the evolution of ultra-relativistic heavy-ion collisions [5-7]. Abundances of the final state hadrons contain important information about the dynamics of the QGP created in relativistic heavy-ion collisions. While the measured integrated yields are rather well understood within the picture of the thermal particle production, the shape of the transverse momentum distribution, in particular at low transverse momentum (pT) below 500 MeV/c, is still poorly understood within the state-of-the-art hydrodynamic model calculations [6-9]. The particle production at low transverse momentum is associated with the long-distance scales, which are accessible in heavy-ion collisions and out of reach in hadronic interactions. Its enhancement could indicate transverse momentum and particle species yield redistribution of the thermally produced hadrons due to conventional phenomena [10-15], which is not yet implemented in the current state-of-the-art hydrodynamic models, or new physics phenomena [16-29].

An enhancement at low transverse momentum was first observed at the ISR in high multiplicity pp and α–α collisions when compared to minimum bias pp collisions [30] and in p–A collisions at Fermilab and CERN [31, 32], and later in A–A collisions at the AGS and CERN [21, 33-36]. A less than 10% enhancement at low-pT was observed for midrapidity pions in both p–Pb and A–A collisions by the NA44 Collaboration [37]. The low-pT enhancement in A–A collisions showed no target size dependence and was smaller for pions at midrapidity compared to target rapidity [21]. Intriguing explanations proposed at that time included exotic behavior in dense hadronic matter [17-19], the decay of quark matter droplets [38], collective effects [20], baryonic and mesonic resonance decays [21-23], and the possible formation of a transient state with partially restored chiral symmetry in the early stage of the heavy-ion collision [24-26].

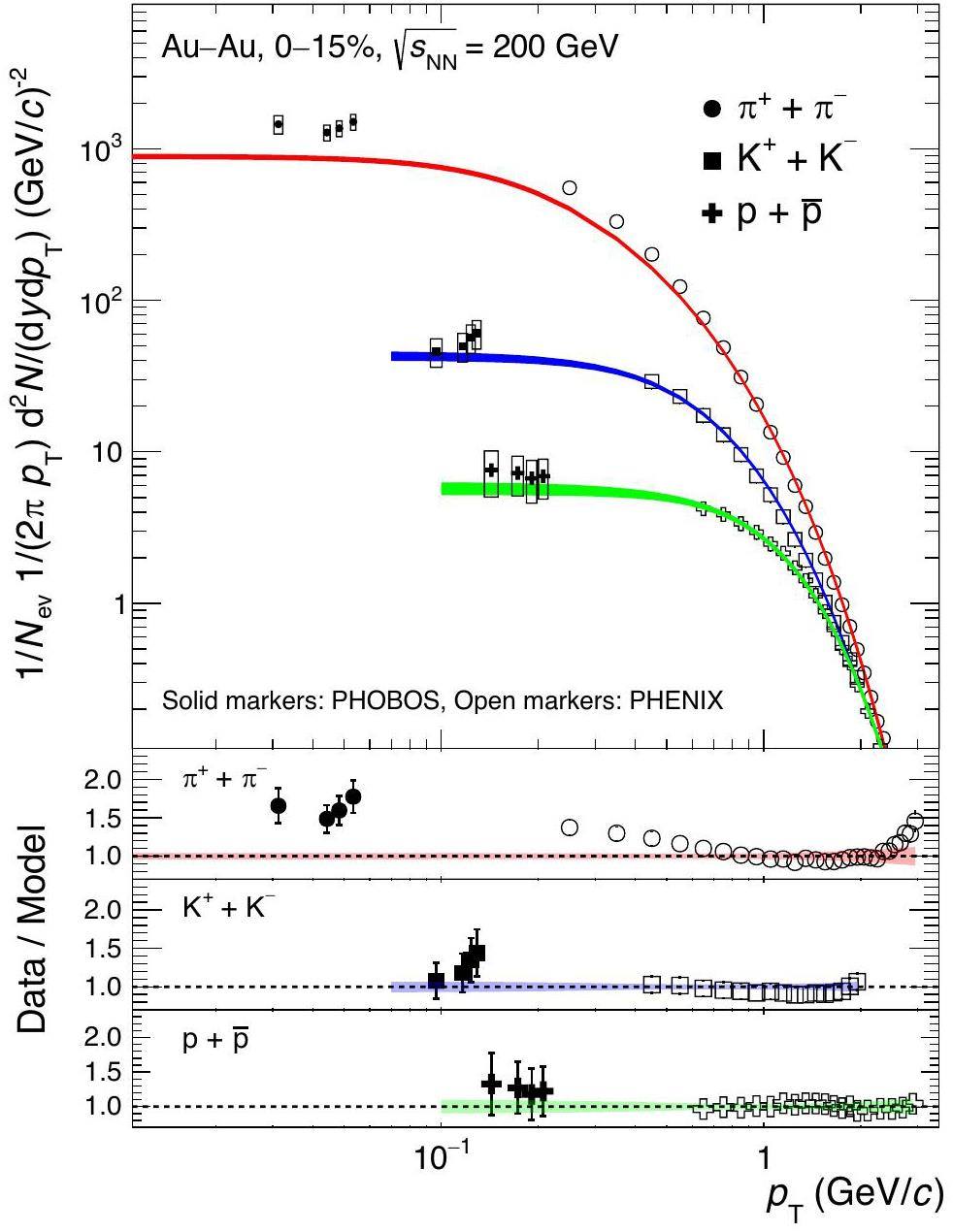

The mechanism of low-pT pion production remains an open question for experiments at the modern heavy-ion colliders. An excess is seen when comparing low-pT pion yield measured by the ALICE [39-42] at the LHC and the PHENIX and STAR [43-46] at RHIC to the hydrodynamic model calculations [7-9, 47-53]. An indication of the excessive pion yield, though with large uncertainties, is also visible from the comparison of the thermal model fits to measured integrated yields of different particle species [12]. While in most experiments at RHIC and the LHC the pion pT spectra are measured only above pT = 0.1–0.2 GeV/c, the PHOBOS experiment at RHIC [54, 55] measured it down to the pT=30–50 MeV/c. An extrapolation of the blast-wave model [55], fitted to PHOBOS experimental data in the intermediate pT region, revealed no significant increase in kaon and proton production when compared to low-pT data. However, the same extrapolation showed a possible enhancement in pion production at very low pT.

The low-pT pion excess may arise from physics mechanisms not accounted for in the current hydrodynamic model simulations, like Bose–Einstein condensation [27, 28], increased population of resonances [10], treatment of the finite width of ρ meson [11], or critical chiral fluctuations [29]. Quantification of the low-pT pion yield excess is important for both, the improvement of fluid dynamic modeling and the search for new particle production mechanisms in heavy-ion collisions. On the experimental side, the proposed next-generation detector ALICE 3 at the LHC [56], which combines excellent particle identification capabilities, a unique pointing resolution, and large rapidity coverage, will allow measurements below pT ~ 100 MeV/c.

To advance in understanding of the mechanism for low pT particle production we propose a procedure to systematically quantify the model-to-data differences using modern Bayesian inference analysis techniques, which allows for consistent treatment of the experimental uncertainties. In this paper, we deploy a procedure based on the relativistic fluid framework FLUIDuM with partial chemical equilibrium (PCE) coupled to TRUIDuM initial state and FASTRESO decays to analyse pT distributions of charged pions, kaons and protons measured in collisions of Pb–Pb at

Modelling of heavy-ion collisions

Our model for simulating high-energy nuclear collisions combines three distinct components. The TRENTO model [57] was utilized for the initial conditions, while the FLUIDuM model with a PCE implementation [58], featuring a mode splitting technique for fast computations, was used for the relativistic fluid dynamic expansion with viscosity. Additionally, the FASTRESO code [15] was used to take resonance decays into account.

The TRENTo model involves positioning nucleons with a Gaussian width w using a fluctuating Glauber model, while ensuring a minimum distance d between them. Each nucleon contains m randomly placed constituents with a Gaussian width of v. TRENTo uses an entropy deposition parameter p that interpolates among qualitatively different physical mechanisms for entropy production [57]. Furthermore, additional multiplicity fluctuations are introduced by multiplying the density of each nucleon by random weights sampled from a gamma distribution with unit mean and shape parameter k. For this study, the TRENTo parameters are set based on [59]. The inelastic nucleon–nucleon cross sections are taken from the measurements by the ALICE and PHENIX Collaborations [60, 61]. The Pb and Au ions are sampled from a spherically symmetric Woods–Saxon distribution, while the Xe ion comes from a spheroidal Woods–Saxon distribution with deformation parameters β2=0.21 and β4=0.0 [62].

The software package FLUIDuM [58], which utilizes a theoretical framework based on relativistic fluid dynamics with mode expansion [63-65], is used to solve the equations of motion for relativistic fluids. The causal equations of motion are obtained from second-order Israel–Stewart hydrodynamics [66]. As in our previous work [8], we are interested in examining the azimuthally averaged transverse momentum spectra of identified particles at midrapidity. Therefore, we do not consider azimuthal and rapidity-dependent perturbations and only require the background solution to the fluid evolution equations, neglecting terms of quadratic or higher order in perturbation amplitudes.

The Cooper–Frye procedure is used to convert fluid fields to the spectrum of hadron species on a freeze-out surface, which in our work is assumed to be a surface of constant temperature [67]. As in our previous work [8], the hadronic phase, after the chemical freeze-out and before the kinetic freeze-out, i.e. Tkin < T < Tchem, is modeled by a concept of partial chemical equilibrium (PCE), which replaces the need for a hadronic after-burner in the simulation. Our description follows the work described in Refs. [68-70], in which different particle species in a hadronic gas are treated as being in chemical equilibrium with each other, while the overall gas is not. During the PCE, the mean free time for elastic collisions is still smaller than the characteristic expansion time of the expanding fireball, thereby keeping the gas in a state of local kinetic equilibrium. The chemical equilibrium is not maintained if the mean free path of the inelastic collisions exceeds this threshold. On the kinetic freeze-out surface, we take the particle distribution function to be given by the equilibrium Bose–Einstein or Fermi–Dirac distribution (depending on the species), modified by additional corrections due to bulk and shear viscous dissipation [71, 72] and decays of unstable resonances [15]. We use a list of approximately 700 resonances from Refs. [73-75].

As described in Ref. [8], our central framework revolves around certain free parameters: the overall normalization constant Norm,

| Pb–Pb | Xe–Xe | Au–Au | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (ζ / s)max | 10-4-0.3 | ||

| (η / s)min | 0.08-0.78 | ||

| Tchem (MeV) | 130-155 | ||

| Tkin (MeV) | 110-140 | ||

| Norm | 20-80 | 50-150 | 3-80 |

| τ0 (fm/c) | 0.1-3.0 | 0.5-7.0 | 0.5-3.0 |

Determination of the optimal fitting range

The pion, kaon, and proton pT spectra across various collision centrality classes measured by the ALICE Collaboration at the LHC and by the PHENIX and STAR Collaborations at RHIC in different colliding systems and center-of-mass energies, namely Pb–Pb collisions at

To determine the optimal

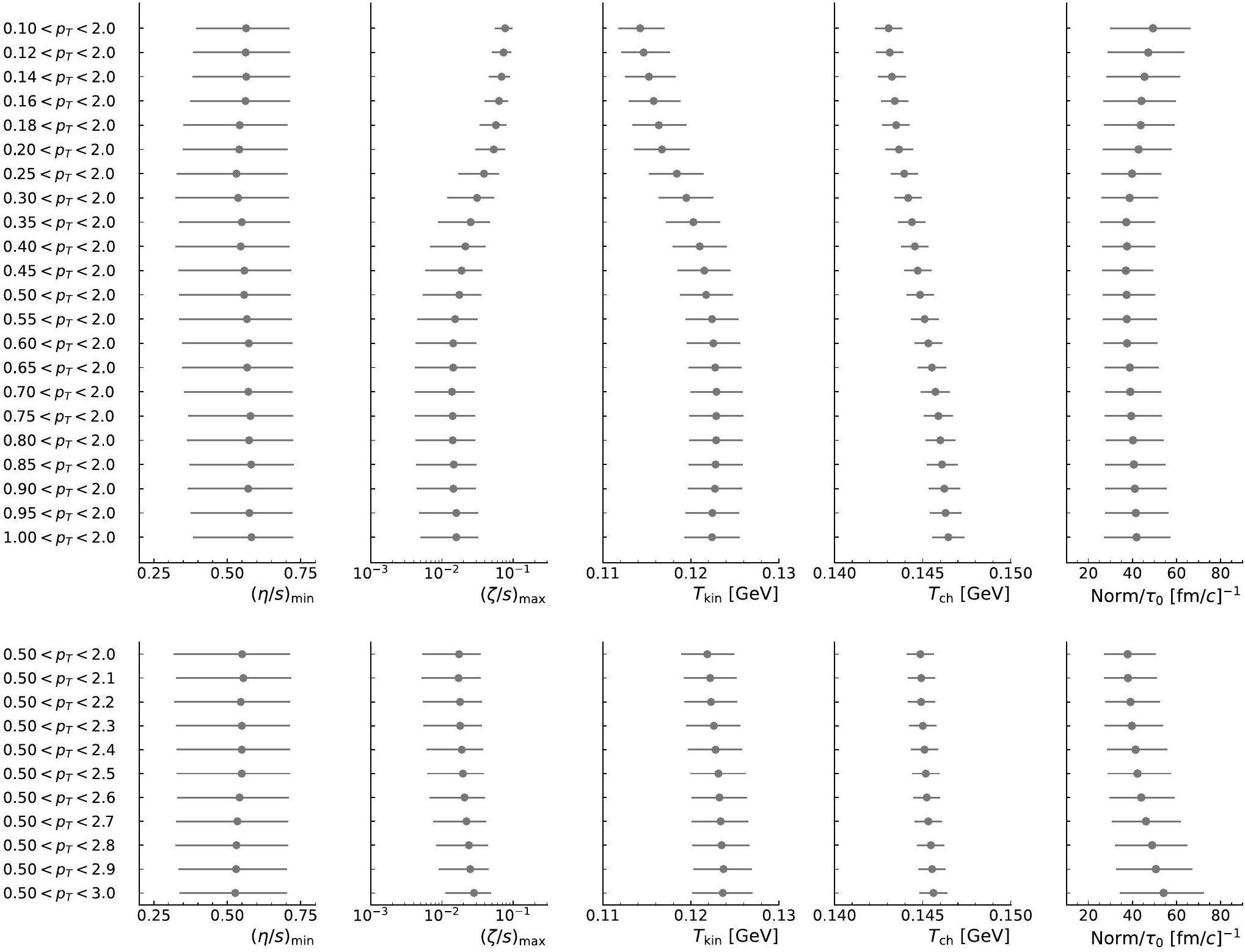

Although the constraint of the QGP physical parameters is not the main focus of this research, it is crucial to monitor their performance and convergence while optimizing the pion pT range. This ensures that the chosen pT range in the Bayesian inference procedure leads to convergence. In Fig. 1 the six key parameters for the 0–5% centrality class in Pb–Pb collisions at

All parameters exhibit varying stability across the fitting ranges. In the top panel, the parameters converge to stable values when x1 exceeds the pT threshold of approximately 0.5 GeV/c. This indicates that using the low- pT pion region (x1 < 0.5 GeV/c) in the Bayesian inference procedure would introduce instabilities in constraining the physical parameters, demonstrating that a fluid dynamic framework cannot capture the experimentally measured low-pT pion spectra. In the lower panel of Fig. 1, the parameters start deviating from the converged values again when the Bayesian procedure includes the spectra values for

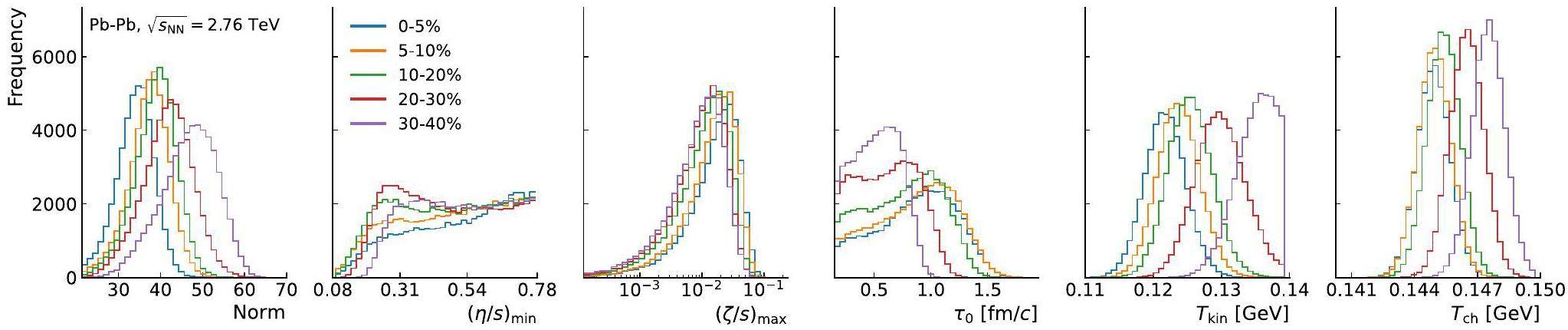

In Fig. 2 the Bayesian posterior distributions of the model input parameters utilized in this analysis for all centrality classes in Pb–Pb collisions at

This study determined that the optimal pT range for the pion pT spectra is

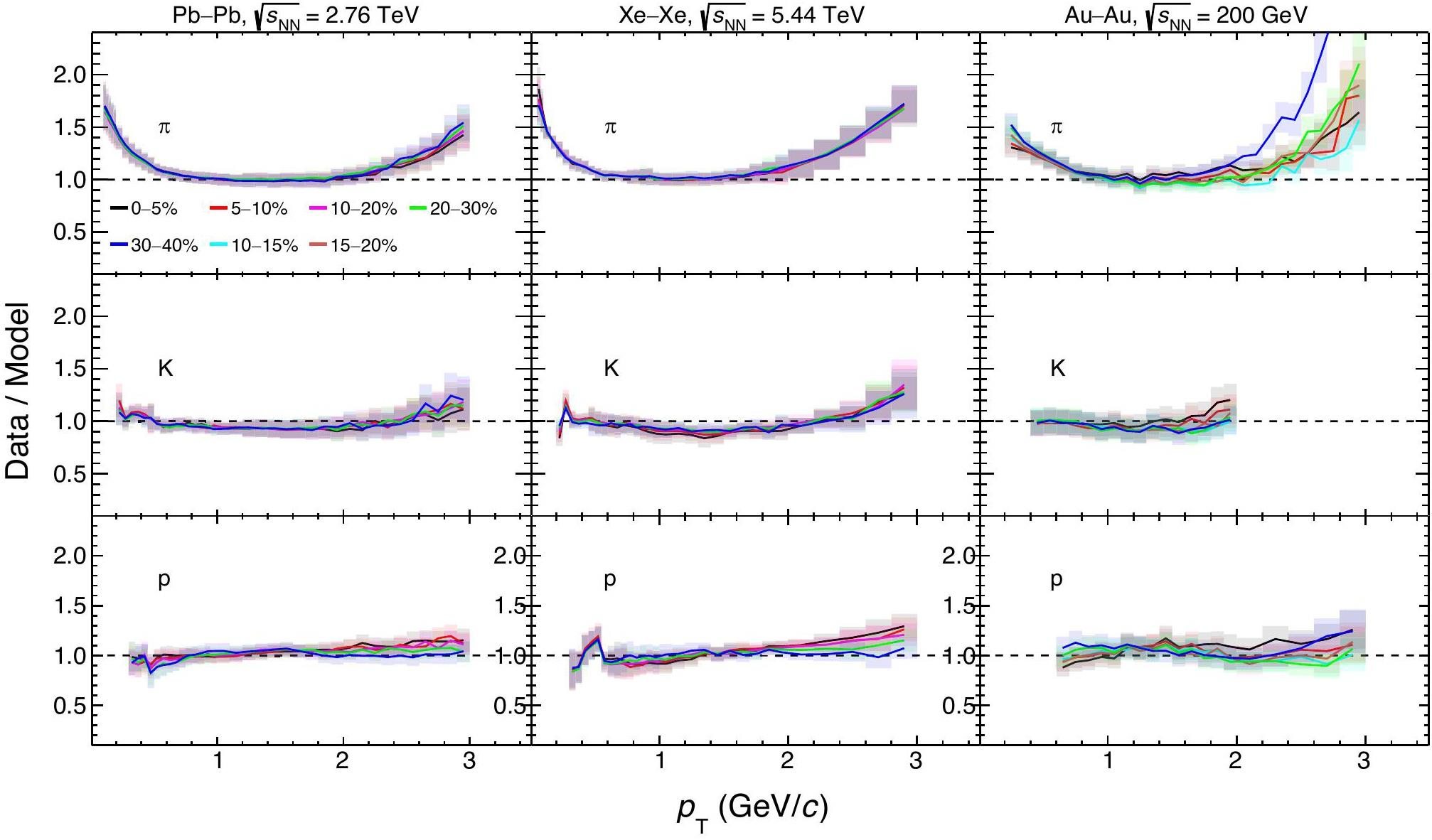

Low-pT pion yields

In Fig. 3 the ratios of the experimental spectra over model calculations for pions, kaons, and protons are shown. For those ratios, the model calculations are performed using the Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) estimates of the parameters [57]. The MAP estimate refers to the set of model parameters corresponding to the mode of the posterior distribution, representing the point in parameter space with the highest posterior probability. Given that we use uniform priors in our Bayesian inference, the MAP values are equivalent to those that maximize the likelihood function. The ratios are arranged in rows per particle type and columns per collision system. The bands depict experimental statistical and systematic uncertainties combined in quadrature. FLUIDuM calculations yield nearly flat data-over-model ratios compatible with unity within one standard deviation across the entire pT spectrum for pion, kaons, and protons for all centrality intervals and collisions systems in the intervals used in the Bayesian analysis.

We recall that for kaons and protons the pT interval used for the Bayesian analysis is pT < 2.0 GeV/c, while for pions it is 0.5 < pT < 2.0 GeV/c. For pT > 2.0 GeV/c, the model calculations for all hadrons start to deviate from experimental measurements, suggesting that the higher pT domain may not be predominantly governed by soft processes, which can typically be described by fluid dynamic calculations. The observed deviations are larger for pions with respect to heavier particles, supporting the idea that hadrons originate from a fluid with a unified velocity field.

In the low-pT range (pT < 0.5 GeV/c), unlike kaons and protons, the data-over-model ratios for pions exceed unity across all centrality classes and collision systems, indicating a systematic pion production excess in the experimental measurements with respect to the fluid dynamic production. As discussed in the previous section, even when including the pion spectra in the Bayesian inference analysis, the fluid dynamic calculation is not able to capture this low-pT interval.

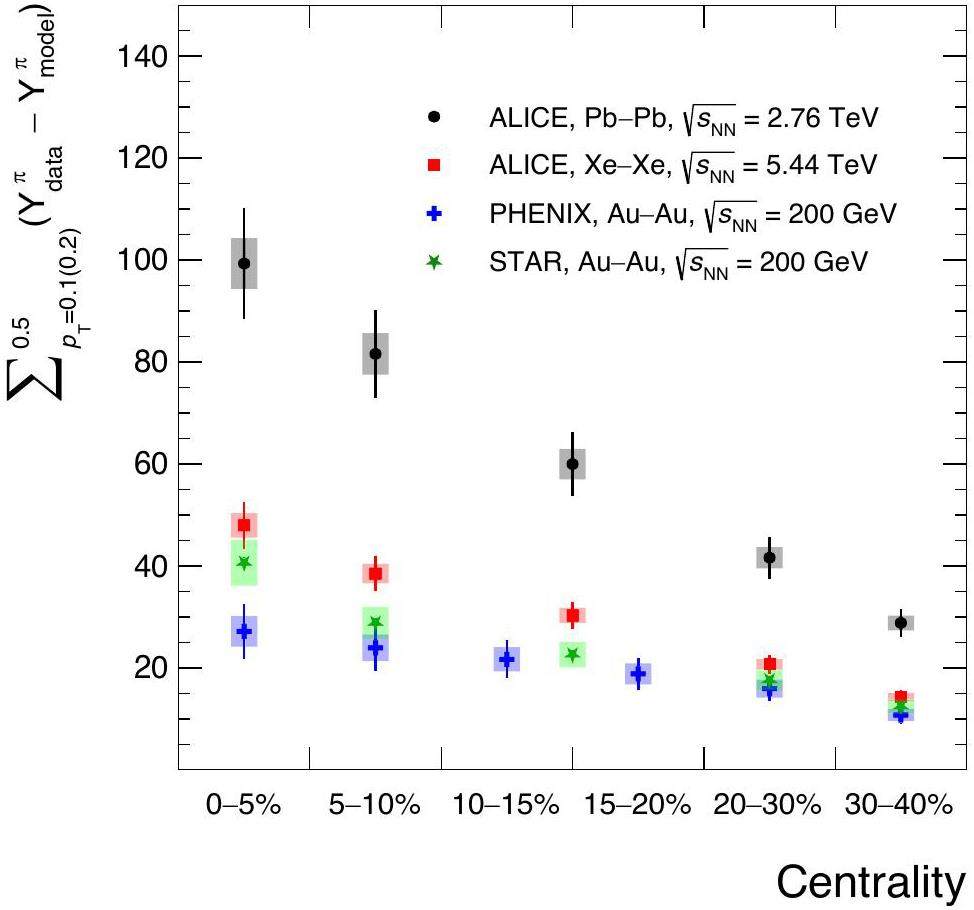

In Fig. 4, the pion excess, computed as the difference between the integral of the experimentally measured pion spectra in the interval pT < 0.5 GeV/c and the integral of the pions computed within our framework in the same pT interval, is shown for the three collision systems as a function of centrality. It is important to notice that the excess is computed in two different pT intervals for LHC and RHIC. At the LHC pion spectra are measured down to pT = 0.1 GeV/c while at RHIC down to pT = 0.2 GeV/c. This study focuses on the single-charge π excess, utilizing π+ pT spectra in Pb–Pb at

The uncertainties depicted by the bands in the figures originate from our model reflecting different sources of model and experimental uncertainty. The uncertainties represent the spread in posterior distributions and the extrapolation in the parameter space performed by the neural network (NN) emulator. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the MAP parameters provide a sufficient description of the data, indicating that the predominant source of model uncertainty arises from our NN emulator. Enhancements in the posterior distribution’s precision could be achieved by conducting the calibration with an increased number of design points and a narrower range of parameter values to increase the density of the training points to reduce the interpolation uncertainty.

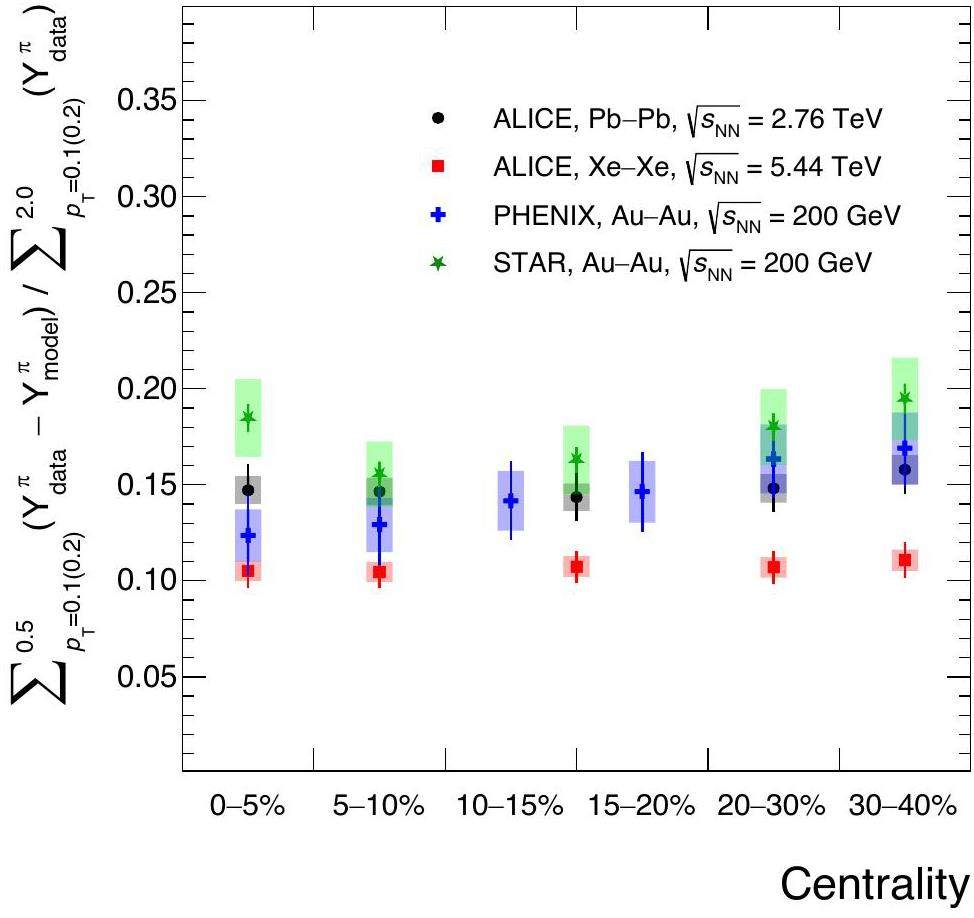

In Fig. 5, the excess relative to the integral of the experimental data in the interval 0.1 < pT < 2.0 GeV/c for the LHC and 0.2 < pT < 2.0 GeV/c for RHIC is presented. When calculating the relative excess the systematic uncertainties between the excess and the integrated pion yields are treated as correlated, which partially cancels them out. For the STAR measurements, due to the limited pT intervals, the PHENIX measurements are used as the denominator, hence no cancellation in the systematic uncertainties was possible. To obtain the yields for the 10–20% centrality interval from PHENIX, the arithmetic average of the yields for 10–15% and 15–20% was used. The relative excess remains constant as a function of centrality, with a consistent 10–20% excess across different collision systems. The computed relative excess indicates that fluid dynamic calculations account only for 80–90% of the measured pion production in heavy-ion collisions. An excess yield is found in all collision systems and centrality ranges considered.

Having performed the Bayesian inference analysis utilizing the available RHIC data at

Summary

In summary, we propose a procedure to advance in understanding the mechanism for low pT particle production in heavy-ion collisions, which allows to systematically quantify the model-to-data differences using modern Bayesian inference analysis techniques and consistently treat the experimental uncertainties. We deploy this procedure using relativistic fluid framework FLUIDuM with PCE coupled to TRENTo initial state and FASTRESO decays to analyse pT distribution of charged pions, kaons, and protons measured in heavy-ion collisions at top RHIC and the LHC energies. Despite the limited information about the correlation among systematic uncertainties in the data, our results indicate a systematic excess of pions produced below

Heavy Ion Collisions: The Big Picture, and the Big Questions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 68, 339-376 (2018). arXiv:1802.04801, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-101917-020852The ALICE experiment: a journey through QCD

. Eur. Phys. J. C 84, 813 (2024). arXiv:2211.04384, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-12935-yExperimental and theoretical challenges in the search for the quark gluon plasma: The STAR Collaboration’s critical assessment of the evidence from RHIC collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 757, 102-183 (2005). arXiv:nucl-ex/0501009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.03.085Formation of dense partonic matter in relativistic nucleus-nucleus collisions at RHIC: Experimental evaluation by the PHENIX collaboration

. Nucl. Phys. A 757, 184-283 (2005). arXiv:nucl-ex/0410003, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.03.086Recent development of hydrodynamic modeling in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 122 (2020). arXiv:2010.12377, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00829-zRunning the gamut of high energy nuclear collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Bayesian analysis of heavy ion collisions with the heavy ion computational framework Trajectum

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Mapping properties of the quark gluon plasma in Pb-Pb and Xe-Xe collisions at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Bayesian quantification of strongly interacting matter with color glass condensate initial conditions

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Thermal phenomenology of hadrons from 200-A/GeV S+S collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 48, 2462-2475 (1993). arXiv:nucl-th/9307020, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.48.2462Effects of ρ-meson width on pion distributions in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 769, 509-512 (2017). arXiv:1608.06817, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.03.060Decoding the phase structure of QCD via particle production at high energy

. Nature 561, 321-330 (2018). arXiv:1710.09425, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0491-6Resonance decay dynamics and their effects on pT-spectra of pions in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 97,The thermal proton yield anomaly in Pb-Pb collisions at the LHC and its resolution

. Phys. Lett. B 792, 304-309 (2019). arXiv:1808.03102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.03.052Fast resonance decays in nuclear collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 284 (2019). arXiv:1809.11049, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6791-7Physics of the pion liquid

. Phys. Rev. D 42, 1764-1776 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.42.1764Nonzero Chemical Potential and the Shape of the pT Distribution of Hadrons in Heavy Ion Collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 243, 181-184 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(90)90836-ULow p(T) pion enhancement from partial thermalization in nuclear collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 262, 326-332 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(91)91575-GSearch for Collective Transverse Flow Using Particle Transverse Momentum Spectra in Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions

. Z. Phys. C 48, 525-541 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01572035Low p(T) phenomena observed in high-energy nuclear collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 566, 175C-182C (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90622-XIs there a low p(T) ’anomaly’ in the pion momentum spectra from relativistic nuclear collisions?

Z. Phys. C 52, 593-610 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01562334Pions from resonance decay in Brookhaven relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 253, 19-22 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(91)91356-ZDCC: Attractive idea seeks serious confirmation

. Acta Phys. Polon. B 27, 1687-1702 (1996). arXiv:hep-ph/9606263Disoriented chiral condensate: Theory and phenomenology

. Acta Phys. Polon. B 28, 2773-2791 (1997). arXiv:hep-ph/9712434Dynamical simulation of DCC formation in Bjorken rods

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Bose-Einstein condensation of pions in heavy-ion collisions at the CERN Large Hadron Collider (LHC) energies

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Fluctuations as a test of chemical non-equilibrium at the LHC

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Soft pions and transport near the chiral critical point

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Charged Particle Spectra in ααand αp Collisions at the CERN ISR

. Z. Phys. C 27, 191 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01556609Inclusive Charged Particle Production in Neutron - Nucleus Collisions

. Phys. Rev. D 19, 3210 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.19.3210Nuclear Size Dependence of Inclusive Particle Production

. Phys. Lett. B 67, 355-357 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(77)90392-6Recent Results From the Na35 Collaboration at CERN

. Nucl. Phys. A 498, 133C-150C (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(89)90594-0Transverse momentum distributions of pi- from 14.6-A/GeV/c silicon ion interactions in copper and gold

. Phys. Lett. B 281, 29-32 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(92)90269-ALow p(T) pion enhancement in Si-28 + Pb collisions at 14.6-A/GeV/c

. Nucl. Phys. A 566, 435C-438C (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90663-7Baryon distributions and meson production in Au+Au at 11.6 solA.GeV c. first particle spectra from E-866

. Nucl. Phys. A 566, 601-604 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90703-XResults from CERN experiment NA44

. Nucl. Phys. A 544, 125C-136C (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(92)90569-6Cold Quark - Gluon Plasma and Multiparticle Production

. Annals Phys. 192, 66 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(89)90116-4Centrality dependence of π, K, p production in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Production of charged pions, kaons, and (anti-)protons in Pb-Pb and inelastic pp collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Production of pions, kaons, (anti-)protons and ϕ mesons in Xe–Xe collisions at sNN=5.44 TeV

. Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 584 (2021). arXiv:2101.03100, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-021-09304-4Multiplicity dependence of charged pion, kaon, and (anti)proton production at large transverse momentum in p-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 760, 720-735 (2016). arXiv:1601.03658, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.07.050Identified charged particle spectra and yields in Au+Au collisions at sNN=200−GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Centrality dependence of pi+ / pi-, K+ / K-, p and anti-p production from sNN=13 GeV Au+Au collisions at RHIC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88,Identified particle distributions in pp and Au+Au collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92,Systematic Measurements of Identified Particle Spectra in pp, d+ Au and Au+Au Collisions from STAR

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Hydrodynamic description of ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions. 634–714 (2003)

. arXiv:nucl-th/0305084Global fluid fits to identified particle transverse momentum spectra from heavy-ion collisions at the Large Hadron Collider

. JHEP 06, 044 (2020). arXiv:1909.10485, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP06(2020)044Towards QCD-assisted hydrodynamics for heavy-ion collision phenomenology

. Nucl. Phys. A 979, 251-264 (2018). arXiv:1805.02985, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2018.09.046Event-by-event anisotropic flow in heavy-ion collisions from combined Yang-Mills and viscous fluid dynamics

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Hydrodynamic predictions for Pb+Pb collisions at 5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Temperature and fluid velocity on the freeze-out surface from π, K, p spectra in pp, p-Pb and Pb-Pb collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Early-Times Yang-Mills Dynamics and the Characterization of Strongly Interacting Matter with Statistical Learning

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132,Particle production at very low transverse momenta in Au + Au collisions at sNN=200−GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Identified hadron transverse momentum spectra in Au+Au collisions at sNN=62.4−GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 75,Letter of intent for ALICE 3: A next-generation heavy-ion experiment at the LHC

. arXiv:2211.02491Alternative ansatz to wounded nucleon and binary collision scaling in high-energy nuclear collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Fluid dynamics of heavy ion collisions with mode expansion

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Bayesian calibration of a hybrid nuclear collision model using p-Pb and Pb-Pb data at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Centrality determination in heavy ion collisions. ALICE-PUBLIC-2018-011

.Transverse energy production and charged-particle multiplicity at midrapidity in various systems from sNN=7.7 to 200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Evidence of the triaxial structure of 129Xe at the Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Mode-by-mode fluid dynamics for relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 728, 407-411 (2014). arXiv:1307.3453, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.12.025Kinetic freeze-out, particle spectra and harmonic flow coefficients from mode-by-mode hydrodynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Statistics of initial density perturbations in heavy ion collisions and their fluid dynamic response

. J. High Energ. Phys 08, 005 (2014). arXiv:1405.4393, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP08(2014)005Causality of fluid dynamics for high-energy nuclear collisions

. J. High Energ. Phys 08, 186 (2018). arXiv:1711.06687, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP08(2018)186Comment on the Single Particle Distribution in the Hydrodynamic and Statistical Thermodynamic Models of Multiparticle Production

. Phys. Rev. D 10, 186 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.10.186The Role of the entropy in an expanding hadronic gas

. Nucl. Phys. 378, 95-128 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(92)90005-VChemical freeze-out temperature in hydrodynamical description of Au+Au collisions at sNN=200−GeV

. Eur. Phys. J. A 37, 121-128 (2008). arXiv:0710.4379, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2007-10611-3Kinetic freeze-out temperature from yields of short-lived resonances

. Phys. Rev. C 102,The Effects of viscosity on spectra, elliptic flow, and HBT radii

. Phys. Rev. 68,Production of photons in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. 93,Constraining the hadronic spectrum through QCD thermodynamics on the lattice

. Phys. Rev. 96,Effect of the QCD equation of state and strange hadronic resonances on multiparticle correlations in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. 98,Effects of bulk viscosity and hadronic rescattering in heavy ion collisions at energies available at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Multidimensional parameter optimization in fluid dynamic simulations of heavy-ion collisions

. Master’s thesis,emcee: The MCMC Hammer

. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 125, 306-312 (2013). arXiv:1202.3665, https://doi.org/10.1086/670067