Introduction

Nuclear fission has been widely applied in nuclear engineering owing to the substantial energy release during this process. Despite the existence of several models that aid in understanding the mechanism of nuclear fission [1-6], current understanding of nuclear fission processes remains incomplete, both in terms of experimental observations and theoretical research [7-10]. Nuclear data serve as a fundamental basis for understanding the physical mechanisms of nuclear fission and its diverse applications in nuclear engineering. As an important fission nucleus, 239Pu is widely used in accelerator-driven subcritical systems and fast neutron reactors [11, 12]. Therefore, nuclear data of the neutron-induced fission of 239Pu have received extensive attention. Specifically, the prompt fission neutron spectra (PFNS) of neutron-induced 239Pu fission have significant applications in reactor calculations, shielding, nuclear fuel management, and transmuting nuclear waste. This has inspired continuous interest in enhancing the accuracy of PFNS for these applications [13, 14].

PFNS measurement is a crucial task in nuclear physics and is commonly achieved through the use of a fission chamber combined with the neutron time-of-flight (TOF) technique. This method obtains the energy of fission neutrons by measuring the time difference between the time signals generated by the fission fragments and those of the emitted neutrons [15]. With the development of experimental detection techniques, several experiments have measured the different energy regions of the PFNS of 239Pu(n, f) for various incident neutron energies [16-20]. However, experimental data often suffer from poor statistics and complex analyses, which can result in incomplete coverage of all energy domains, large uncertainties, and inconsistencies [16-20].

In practice, evaluated data are used in various engineering applications. The evaluation process typically involves both experimental data and theoretical calculations. Models such as the Maxwellian distribution, Watt spectrum, and Los Alamos model [21-23] are typically used for evaluation with the aim of providing evaluated data across the entire energy range. However, it is important to note that the current state of PFNS within evaluated nuclear data libraries is not yet fully satisfactory. Despite the existence of several international libraries, such as CENDL-3.2 [24], ENDF/B-VIII.0 [25], JENDL-5 [26], and JEFF-3.3 [27], inconsistencies in PFNS remain. This highlights the need for further research to enhance data accuracy and consistency.

The uncertainty in differential experimental data is often relatively large. The use of similar detection methods in most experiments can lead to unidentified biases or errors, resulting in incorrect evaluations of mean values and covariances [28]. Given that the measurement accuracy of physical quantities in integral experiments is often higher and directly related to practical applications, integral experimental data can be used to constrain differential experimental data. Several studies have aimed to provide guidance for improving evaluation data through integral experiments. These methods typically constrain microscopic data by simulating integral experiments, employing models to represent the microscopic data, and utilizing sensitivity analysis and Bayesian methods to adjust the microscopic data [28-31].

However, the uncertainties derived from the propagation of model parameter uncertainties in PFNS models tend to be smaller at certain outgoing energies, which is often inconsistent with the uncertainties typically observed in experimental PFNS. Furthermore, uncertainties attributable to the inherent shortcomings of the model are usually not estimated or included in the evaluation process [32-34]. To minimize the impact of the model on data optimization and circumvent the sensitivity analysis requirement that the integral quantity must exhibit a linear response to the differential quantity, this study perturbs the latest differential experimental data to generate a significant amount of PFNS data. Subsequently, the perturbed PFNS are then incorporated as inputs into a transport simulation. By comparing the calculated integral quantities keff for the criticality benchmarks, the quality of the perturbed PFNS is evaluated.

In general, perturbations can be performed based on the covariance matrix. However, the covariance matrix in experiments typically needs to be obtained through sufficient experimental information, such as counting statistics, background correction, detector efficiency determination, finite-time resolution, and uncertainty in the TOF length [35]. Furthermore, many studies have not clearly reported this information, particularly in early experiments.

Therefore, in this study, an assumed correlation matrix is combined with experimental uncertainties to generate a covariance matrix. Additionally, for comparative analysis, sampling is conducted using the covariance matrix provided by the experiment. This offers a novel approach for optimizing microscopic experimental data through integral experiments. Specifically, this method can be applied to optimize microscopic experimental data when a covariance matrix is not provided.

Methods

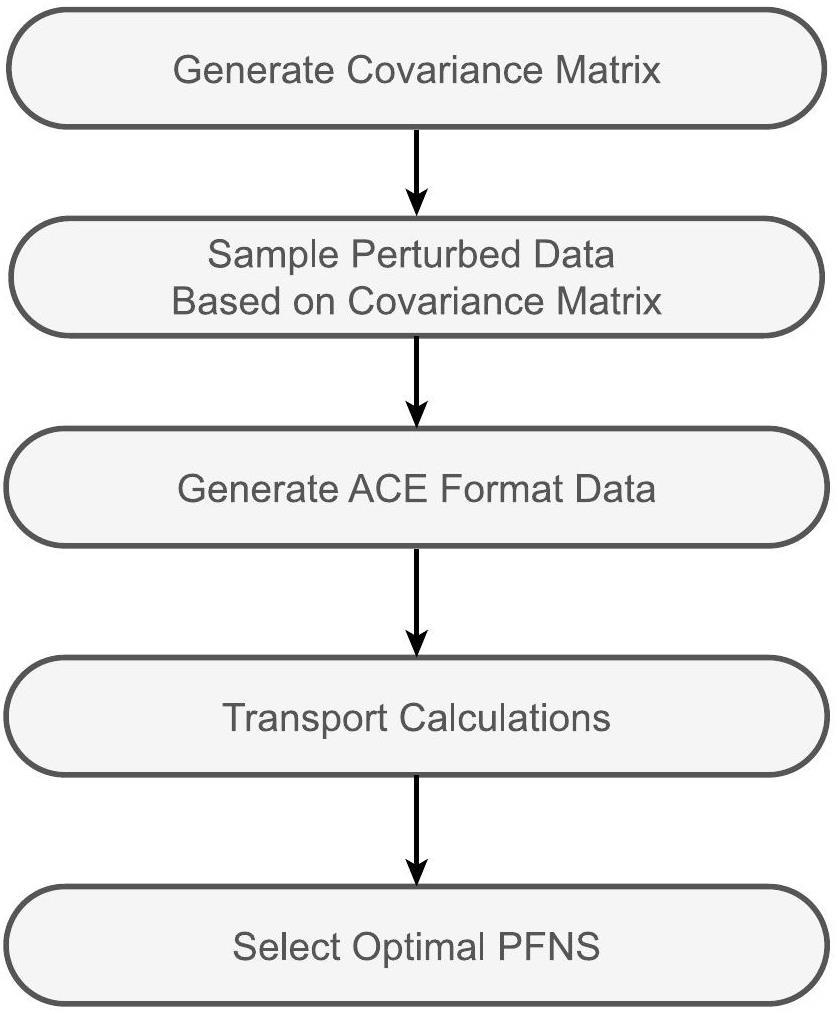

Considering the relatively large uncertainties associated with differential experiments, and taking into account the higher precision of integral experimental data, as well as the fact that criticality benchmark experiments have already been employed for validating and improving nuclear data [36, 37], alongside their similarity to engineering applications, this study aims to maximize the utilization of the existing experimental data. To achieve this aim, integral nuclear data keff were employed as the target quantity to constrain the microscopic nuclear data, specifically the PFNS of 239Pu. The main approach involved using the differential experimental data and their associated uncertainty information to perturb the experimental values and then utilizing these perturbed data in transport simulations to determine the optimal differential data.

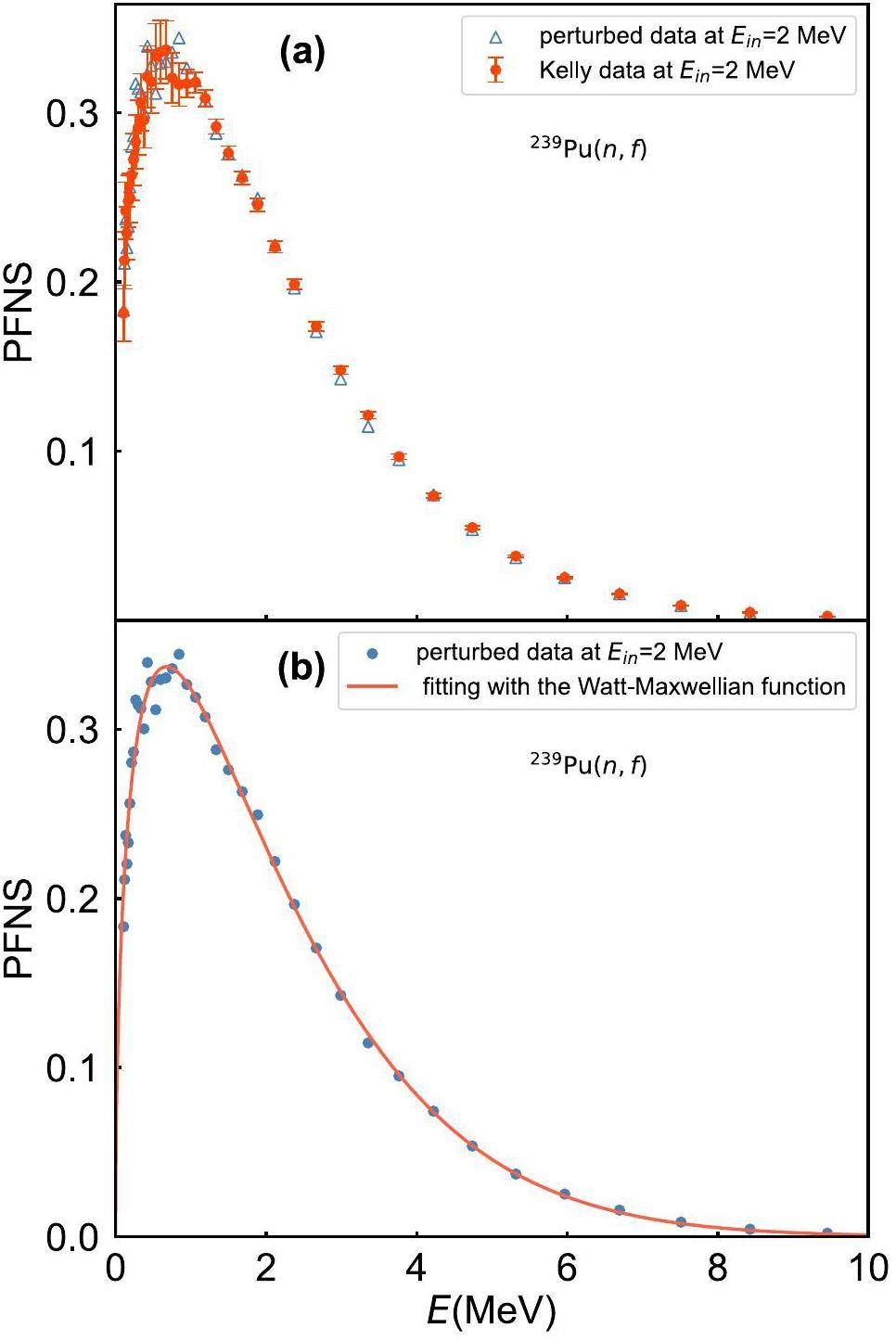

To minimize the impact of the models on this method, a data-driven approach was adopted to constrain the PFNS. As the Watt-Maxwellian function has four adjustable parameters, it exhibits flexibility in describing the PFNS [32, 38]. Consequently, the experimental data were typically well-fitted by the Watt-Maxwellian function. The Watt-Maxwellian function was exclusively employed to describe the differential data, leveraging its properties of normalization and non-negativity to ensure that the PFNS maintained the characteristics of the shape spectra and enabled the extrapolation of differential data beyond the available range. The Watt-Maxwellian function is a linear combination of the Maxwellian and Watt distributions:

Generation of the perturbed PFNS

The differential experimental data used in this method were sourced from the experimental nuclear reaction database (EXFOR), as reported in [39, 40]. These studies have reported the latest experimental data on the neutron-induced PFNS of 239Pu, covering 20 average incident energy points ranging from 1 to 20 MeV. Compared with the measurement results in the previous literature, this dataset has achieved breakthroughs in terms of accuracy, detailed uncertainty analysis, and thorough investigations of necessary corrections [39, 41].

By utilizing the experimental uncertainty information, a perturbation of the data around the experimental measurements is proposed to generate a perturbed PFNS for transport code simulations. However, owing to the large number of data points, a gridded approach for generating points, in which candidate values are generated at each energy point based on the mean values and error bars, significantly slows the calculation process as the computational load grows exponentially with the number of data points. To reduce computational cost, this study introduces a sampling method that utilizes a covariance matrix to reduce the dimensionality of data variations. This obtains a relatively optimized PFNS with fewer simulation calculations, thereby improving computational efficiency.

The EXFOR database often includes experimental data accompanied by uncertainties; however, covariance data are not always available. To develop a method applicable to general scenarios, particularly in the absence of a reported covariance matrix, a correlation matrix was constructed based on the characteristics observed in the correlation matrix in [39, 40], and a covariance matrix was generated by combining the uncertainty information from the experiments. The correlation matrix diagram [39, 40] showed an extremely high correlation between the PFNS at different neutron incident energies. Therefore, assuming that the correlation between different data points in the PFNS spectrum decreases exponentially with the square of their distance, as shown in Eq. 2, a covariance matrix was constructed and used to perturb each data point of the PFNS spectrum at a single incident energy.

To mitigate the impact of excessive uncertainty at low-energy points on the fitting function, data points were selected within an energy range consistent with those reported in the literature, specifically selecting points 100 keV for outgoing neutron energies. Based on the above description, the total uncertainty was used as the standard deviation, which is the square root of the variance. The correlation definition provided in Eq. 3 [42] was used to obtain the covariance matrix. From this definition, it was simple to derive Eq. 4. The covariance matrix was computed by combining the derived equation with the assumed correlation matrix.

As depicted in Fig. 1, random sampling utilizing the covariance matrix effectively generated perturbed data proximal to the experimental data, and the Watt-Maxwellian function exhibited a robust fit to the perturbed data points. For a comprehensive set of PFNS encompassing various incident energies, a strong correlation across PFNS at different incident energies was achieved by selecting a uniform random number seed. This novel sampling and fitting methodology yielded a substantial number of continuous PFNS.

Using the perturbed data for transport calculations

To correlate differential data with integral data, transport calculations were used, taking differential data as the input and generating integral data as the output, which was then compared with the benchmarks. In this study, the Joint Monte Carlo transport (JMCT) code was utilized to perform criticality computations [43-45].

To optimize the PFNS, during transport calculations, except for the PFNS data, all other nuclear data were obtained from the ENDF/B-VIII.0 library [25]. To generate PFNS data suitable for utilization in this code, a nuclear data processing system (NJOY2016) was used to process the perturbed PFNS data, transforming them into the ACE format [46]. To facilitate subsequent comparisons with the results from ENDF/B-VIII.0, the same incident energy selections as those in ENDF/B-VIII.0 were adopted. As the experimental data did not perfectly align with this set of incident energies, linear interpolation was used to generate PFNS for various incident energies. As the range of the experimental incident energies was slightly narrower than that of ENDF/B-VIII.0, the PFNS was extrapolated for energies below the minimum experimental average incident energy of 1.54 MeV or above the maximum experimental incident energy of 19.59 MeV in ENDF/B-VIII.0. Specifically, a consistent approach of linear extrapolation, analogous to the aforementioned linear interpolation method, was used to predict PFNS at these incident energies.

Given that the differential experimental data employed in this study were limited to the incident energy range 1 MeV, the selection of fast neutron spectra was the most appropriate for this specific energy domain. To minimize the possible uncertainty in the transport process while covering as much of the experimental data region as possible, five criticality benchmarks with relatively simple geometric configurations were selected. Each of these benchmarks is characterized by a dominant “FAST” flux spectrum and is directly associated with the nuclide 239Pu. The benchmark cases employed in this study were Pu-Met-Fast-002, Pu-Met-Fast-003, Pu-Met-Fast-008, Pu-Met-Fast-009, and Pu-Met-Fast-010 [47, 48]. In the aforementioned benchmarks, Pu-Met-Fast-002 represents a bare experiment (20.1 at.% 240Pu), Pu-Met-Fast-003 represents an array of plutonium metal buttons in an unmoderated configuration, Pu-Met-Fast-008 represents an experiment involving a thorium reflector, Pu-Met-Fast-009 represents an aluminum reflected experiment, and Pu-Met-Fast-010 represents an experiment that utilizes a natural uranium reflector [49]. By utilizing these relatively simple criticality benchmark assemblies, which encompass diverse configurations, this study aimed to enhance the robustness of the constraints on differential data by integrating the experimental data. The input for the JMCT used computer aided design (CAD) modeling [45], and the models of these criticality benchmarks were constructed based on information sourced from the MIT Computational Reactor Physics Group [50].

All cases were executed using the same perturbed data, with each simulation using 10000 neutrons per cycle, 100 inactive cycles, and 1400 additional active cycles. The uncertainty of the calculated eigenvalue keff exhibited a slight variability depending on the device and input files; however, it consistently remained < 20 pcm. This value is notably smaller than the benchmark uncertainties.

Calculated

To evaluate the quality of each perturbed PFNS, a comparative analysis was conducted between the eigenvalues keff derived from transport simulations for the five criticality benchmarks and their respective benchmark values. Specifically, the relative calculation-to-experimental ratio, denoted as

This approach enabled the identification of the most suitable perturbed PFNS that best captured the integral experimental behavior and achieved optimal results.

Results and discussion

Calculation results from the generated covariance matrix

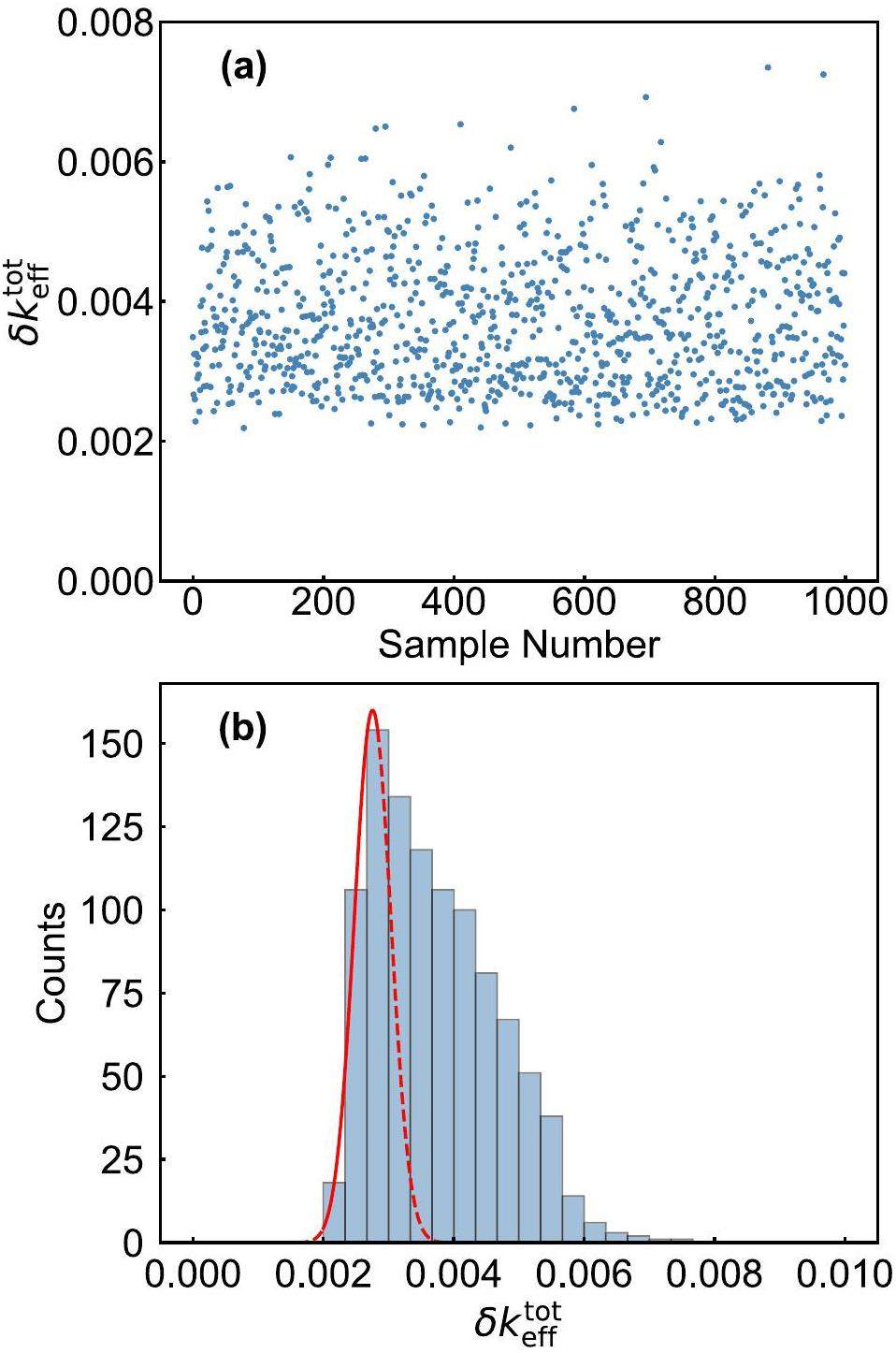

By following the steps shown in Fig. 2, a covariance matrix was initially generated based on Eq. 2, assuming that σ = 1. This assumption allowed the derivation of a correlation matrix that exhibited a relatively rapid decrease in the correlation between data points. By incorporating the uncertainty data provided in the experiment [40], the covariance matrix was obtained for this specific scenario. Subsequently, this covariance matrix was used to perform random sampling of the data points, thereby generating perturbed datasets. In this framework, 1,000 samplings were executed and the corresponding

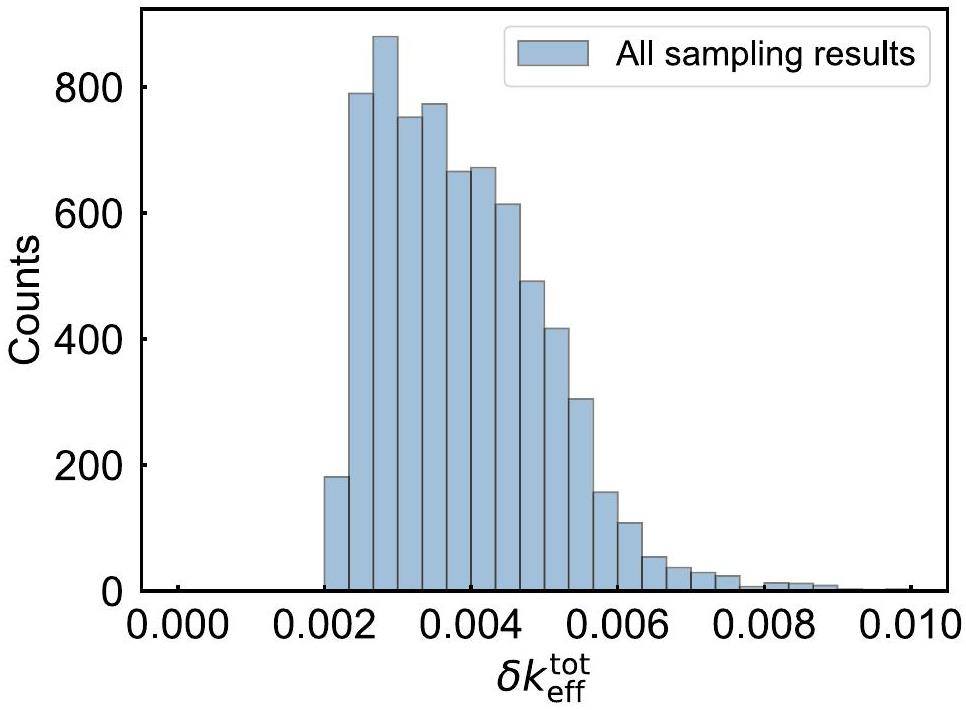

Figure 3(a) illustrates the effect of the PFNS sampled from the generated covariance data on the transport calculations. The scattered random distribution of points reflects the stochastic nature of the sampling process. It is evident that different PFNS lead to variations in the computed keff values, demonstrating that adjustments to the differential data within the error bands can affect the integral data. This further validates the effectiveness of constraining differential experiments through integral experiments. Figure 3(b) shows a histogram of the statistical distribution of

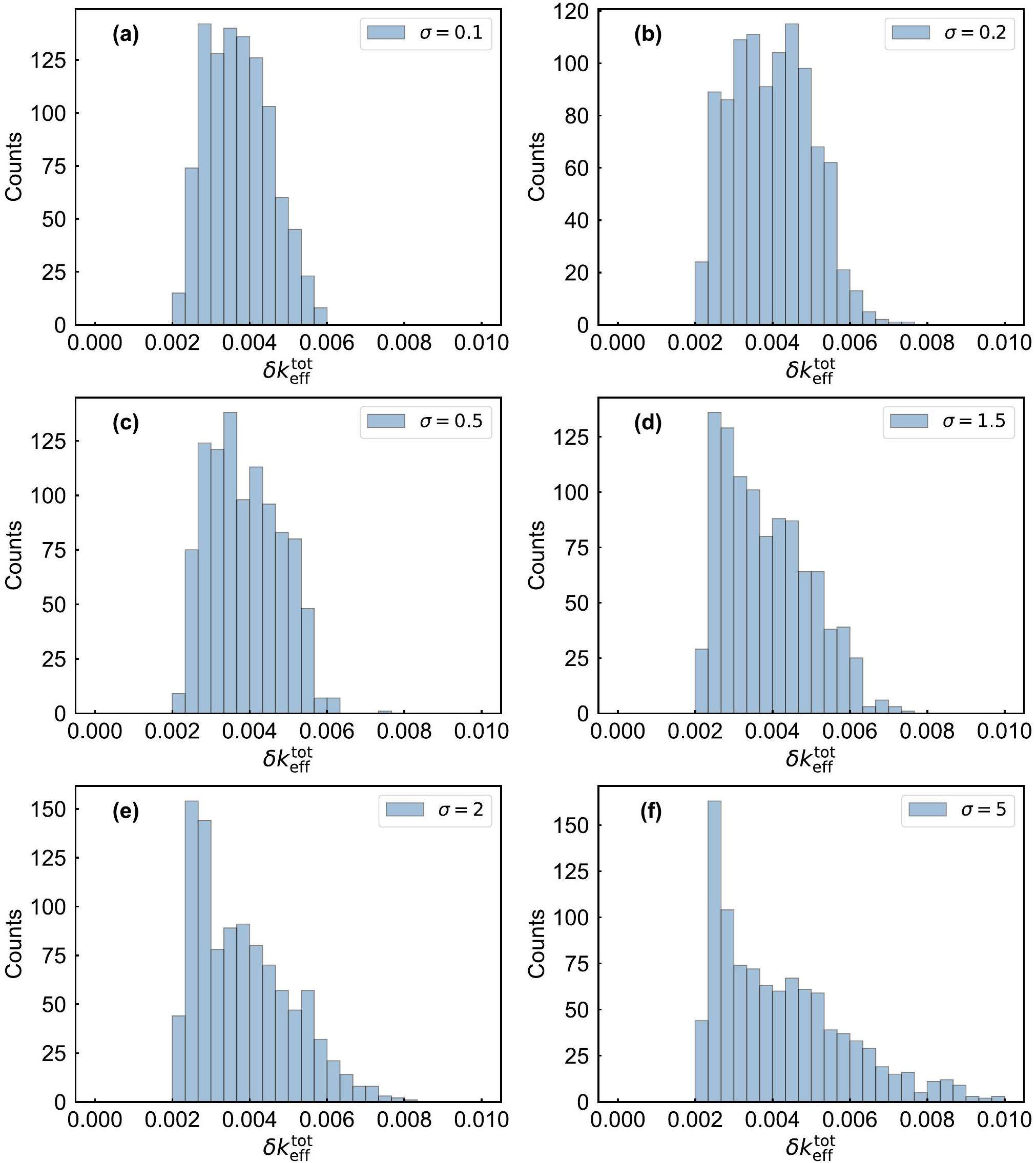

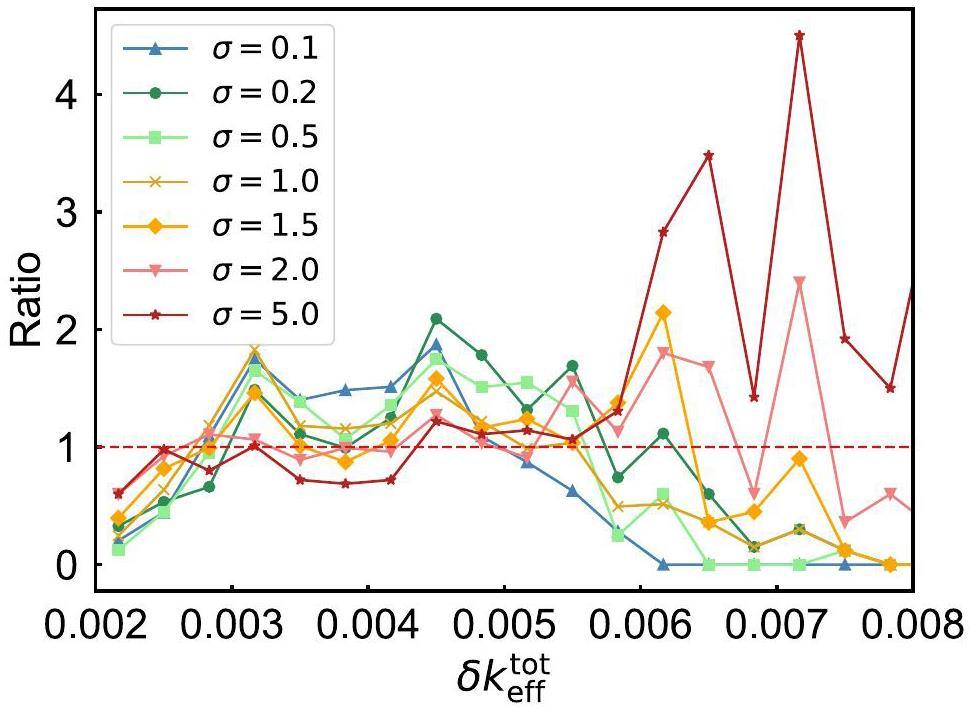

To broaden the scope of the parameter variation, different values for σ were selected in Eq. 2. By choosing distinct σ values, the rate of decrease in the correlation for the correlation matrix was altered, thereby generating different covariance matrices. In addition, σ = 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.5, 2.0, and 5.0 were selected and the method detailed in Sect. 2 was used to generate the covariance matrices. Analogous to the case where σ = 1.0,

As illustrated in Fig. 4, although the distribution of

The perturbed PFNS have been obtained for seven distinct σ values. The results were compiled together to use the statistical information from the entire sampling process. The overall distribution of

Calculation results from the experimental covariance matrix

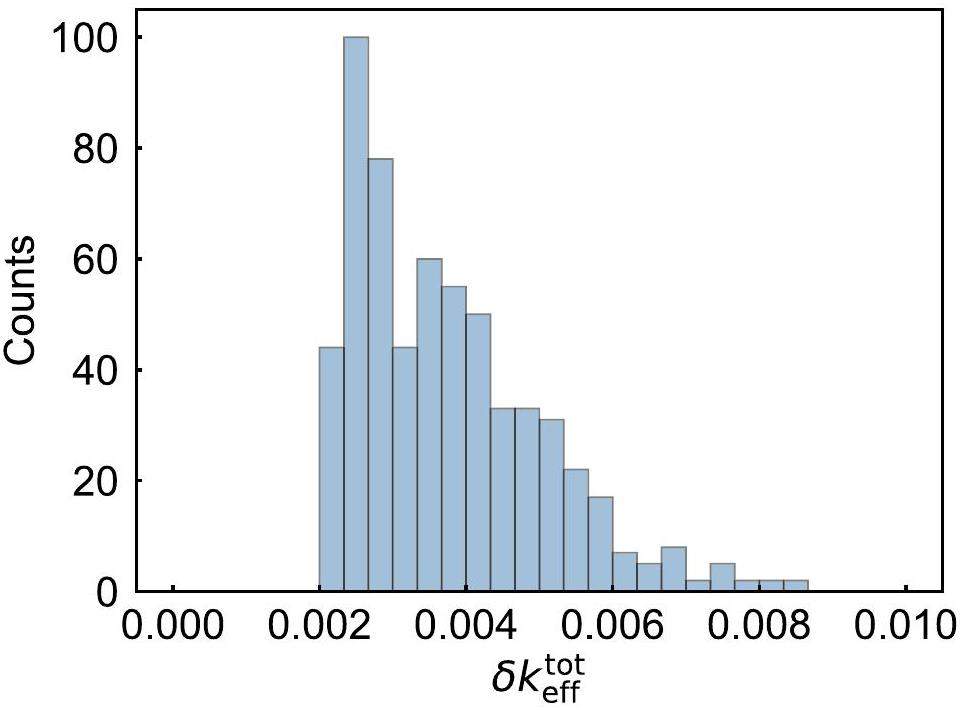

In recent years, with the growing emphasis on covariance data in experiments and evaluations, more experiments have begun to report covariance data. The experimental data used in this study included a reported covariance matrix [39, 40]. The reported covariance matrix from the experiment was used to generate a perturbed PFNS using the aforementioned sampling method. This specific method is consistent with that described in Sect. 2, with the only modification being the replacement of covariance matrix generation. 600 samplings were performed using the covariance data provided by the experiment and the

Discussion

Covariance matrices were generated for the differential data using two distinct methods. Method 1 involved constructing a correlation matrix and combining it with the experimental uncertainty information,. Method 2 directly utilized the covariance information provided by the experiment. The experimental data were perturbed near the error range through random sampling and the perturbed PFNS were used for transport calculations to conduct integral validation, thereby optimizing the differential PFNS.

Based on the results presented in Figs. 5 and 6, the distributions of

| PFNS Source | Method 1 | Method 2 | ENDF/B-VIII.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00210 | 0.00208 | 0.00299 |

Although methods 1 and 2 can optimize the PFNS to approach an optimal value, differences in the covariance matrix lead to varying convergence speeds of the data near this optimal value. The distribution characteristics near a low

Figure 7 illustrates that, near the left end of the

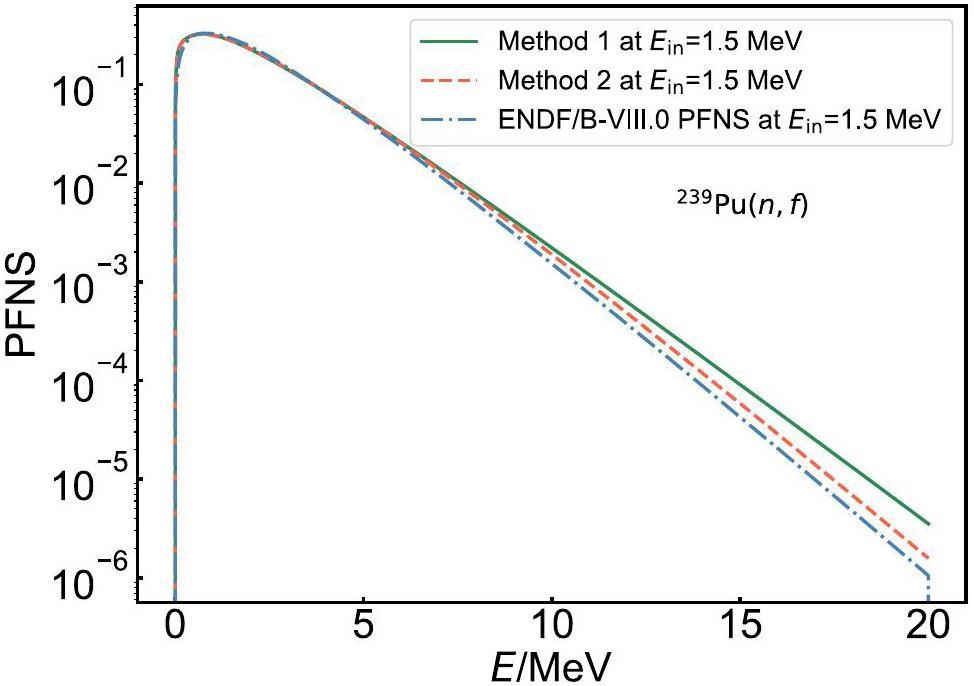

Figure 8 presents a comparison of the optimized PFNS results obtained using Methods 1 and 2 with ENDF/B-VIII.0, using an incident energy of 1.5 MeV as an example. The optimized PFNS exhibited slight variations from ENDF/B-VIII.0, and these variations contributed to the optimization of the integral experiment for calculating keff. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the method of utilizing integral experiments to constrain differential experiments demonstrates an effective adjustment of PFNS. Owing to the normalization of the spectrum, there is inevitably an interplay between the low- and high-count parts of the final energy spectrum, and the distribution in the low-count region is modulated by slight variations in the high-count region. The results show that the adjusted PFNS performs better in calculating the criticality benchmarks. Consequently, the adjustment to the PFNS is beneficial for the entire spectrum, as it aligns well with both the microscopic and integral experiments.

Summary and prospects

In summary, a method was introduced that utilizes integral criticality benchmark experiments to constrain the data of differential quantities, specifically the PFNS. The measured central values were perturbed by constructing a correlation matrix and combining it with the experimental error data provided by experiments. Subsequently, the perturbed PFNS was used as the input data for transport simulations. The quality of the perturbed PFNS was evaluated by comparing the deviation between the calculated keff and the benchmark values of the criticality assemblies. A set of optimal PFNS values was obtained through extensive sampling. In addition, this study examined a sampling method based on a covariance matrix derived from differential experiments. The results indicate that sampling using the covariance matrix directly provided by the experiments yields a higher probability of obtaining results close to the optimal value, thereby facilitating the achievement of a better PFNS with fewer sampling instances. Notably, in terms of the optimal value, the method for generating a covariance matrix using an assumed correlation matrix is similar to the method that utilizes the experimentally provided covariance matrix. This indicates that, for data lacking an experimentally provided covariance matrix, the proposed method can still be utilized to obtain a relatively optimized PFNS through a finite number of sampling iterations.

It is also important to note that the optimal

Fission barriers of compound superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,A microscopic theory of fission dynamics based on the generator coordinate method

. Lecture Notes in Physics (2019) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04424-4Geant4 development for actinides photofission simulation

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1062,A general framework for describing photofission observables of actinides at an average excitation energy below 30 MeV

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Sensitivity impacts owing to the variations in the type of zero-range pairing forces on the fission properties using the density functional theory

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01422-4Theory of nuclear fission

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 125,Pre-neutron-emission mass distributions for reaction 238U(n, f) up to 60 MeV

. Chin. Phys. C 39,Cumulative fission yield measurements with 14.7 MeV neutrons on 238U

. Chin. Phys. C 47,Exploratory study of fission product yields of neutron-induced fission of 235U, 238U, and 239Pu at 8.9 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Nuclear fission dynamics: Past, present, needs, and future

. Front. Phys. 8, 63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.00063The electron accelerator driven sub-critical system

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 386,239Pu prompt fission neutron spectra impact on a set of criticality and experimental reactor benchmarks

. Nucl. Data Sheets 118, 459-462 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2014.04.106The need for precise and well-documented experimental data on prompt fission neutron spectra from neutron-induced fission of 239Pu

. Nucl. Data Sheets 131, 289-318 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2015.12.005Uncertainty propagation of prompt fission neutron spectrum for physics analysis of fast and thermal reactors

. Prog. Nucl. Energy 144,Prompt-fission-neutron average energy for 238U(n,f) from threshold to 200 MeV

. Phys. Lett. B 575, 221-228 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2003.09.048Prompt fission neutron energy spectra induced by fast neutrons

. Nucl. Phys. A 591, 41-60 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00119-LAdvanced Monte Carlo modeling of prompt fission neutrons for thermal and fast neutron-induced fission reactions on 239Pu

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Measurement of prompt neutron spectra from the 239Pu(n,f) fission reaction for incident neutron energies from 1 to 200 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Uranium and plutonium average Prompt-fission Neutron Energy Spectra (PFNS) from the analysis of NTS NUEX data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 119, 213-216 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2014.08.059Prompt-fission-neutron spectra in the 239Pu(n, f) reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Fission neutron spectra and nuclear temperatures

. Phys. Rev. 113, 527-541 (1959). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.113.527Energy spectrum of neutrons from thermal fission of 235U

. Phys. Rev. 87, 1037-1041 (1952). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.87.1037New calculation of prompt fission neutron spectra and average prompt neutron multiplicities

. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 81, 213-271 (1982). https://doi.org/10.13182/NSE82-5CENDL-3.2: The new version of Chinese general purpose evaluated nuclear data library

. EPJ Web Conf. 239, 09001 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023909001ENDF/B-VIII.0: The 8th major release of the nuclear reaction data library with CIELO-project cross sections, new standards and thermal scattering data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 148, 1-142 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2018.02.001Japanese evaluated nuclear data library version 5: JENDL-5

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 60, 1-60 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2022.2141903The joint evaluated fission and fusion nuclear data library, JEFF-3.3

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00141-9Uncertainties in nuclear fission data

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 42,Combined use of integral experiments and covariance data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 118, 596-636 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2014.04.145Enhancing nuclear data validation analysis by using machine learning

. Nucl. Data Sheets 167, 36-60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2020.07.002Evaluation and use of the prompt fission neutron spectrum and spectra covariance matrices in criticality and shielding

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 610, 540-552 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.08.076Prompt Fission Neutron Spectra of Actinides

. Nucl. Data Sheets 131, 1-106 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2015.12.002Impact of model defect and experimental uncertainties on evaluated output

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 723, 163-172 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2013.05.005Nuclear data evaluation methodology including estimates of covariances

. EPJ Web Conf. 8, 04001 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/20100804001Preliminary evaluation and uncertainty quantification of the prompt fission neutron spectrum of 239Pu

. Nucl. Data Sheets 123, 146-152 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2014.12.026Benchmark experiment on slab 238U with D-T neutrons for validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 29 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01386-5Measurement and simulation of the leakage neutron spectra from Fe spheres bombarded with 14 MeV neutrons

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 182 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01329-6Current issues in nuclear data evaluation methodology: 235U prompt fission neutron spectra and multiplicity for thermal neutrons

. Nucl. Data Sheets 123, 8-15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2014.12.003Measurement of the 239Pu(n,f) prompt fission neutron spectrum from 10 keV to 10 MeV induced by neutrons of energy 1–20 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 102,The Covariance of PFNS Results from the Chi-Nu Experiment

. EPJ Web Conf. 281, 00026 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202328100026Comparison of results from recent NNSA and CEA measurements of the 239Pu(n, f) prompt fission neutron spectrum

. Nucl. Data Sheets 173, 42-53 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2021.04.003The analysis of shape data including normalization and the impact on prompt fission neutron spectrum measurements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 943,JMCT Monte Carlo Code with Capability of Integrating Nuclear System Feedback

, in Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Applied Mathematics, Modelling and Statistics Application (AMMSA 2018), pp. 48-54, (2018), https://doi.org/10.2991/ammsa-18.2018.10The coupled neutron transport calculation of Monte Carlo multi-group and continuous cross section

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 127, 433-436 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2018.12.032A high fidelity general purpose 3-D Monte Carlo particle transport program JMCT3.0

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01092-0The NJOY Nuclear Data Processing System, Version 2016

. (2017). https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1338791An expanded criticality validation suite for MCNP

. (2011). https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1083139ICSBEP Handbook 2019

. (2019). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/data/e2703cd5-enCross-Evaluation of the PU-MET-FAST criticality benchmark experiments in ICSBEP handbook (by the end of 2022)

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 415,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.