Introduction

The terahertz (THz) frequency range extends from 0.1 THz to 10 THz, positioned between far-infrared and microwave frequencies, and is often referred to as the “THz gap” [1-3]. THz photons, with a photon energy of approximately 4 meV at 1 THz, possess relatively low energy. Their high transmittance through most nonconductive materials and large bandwidth render THz technology promising for applications such as material analysis [4, 5], nondestructive testing in biology [6-9], security screening [10, 11], and high-speed communication [12, 13]. THz fields are typically detected using Golay cells, bolometers, Schottky/tunnelling diodes, and pyroelectric detectors [14, 15]. Nonetheless, with the diversification of application domains, considerable challenges remain in creating sensors that can simultaneously measure THz fields with high sensitivity and speed.

Recently, a new type of THz detector system based on Rydberg atoms has emerged, expanding THz spectroscopy detection technology [16, 17]. Rydberg atoms with high polarization rates and strong THz transition dipole moments are promising sensitive THz detectors, for example, alkali atoms excited to high principal quantum numbers [18-21]. Typically, THz detection can be directly demonstrated using photoluminescence (PL) spectra resulting from spontaneous emission during the decay of the THz-induced final Rydberg state [18, 19]. Wade et al. introduced an innovative technique for real-time near-field THz imaging that employs atomic PL signals [18]. Researchers at Durham University have also proposed a THz imaging system that achieves THz-to-optical conversion using atomic vapor, which is capable of full-scene imaging using conventional optical camera technology, demonstrating a frame rate of up to 3000 fps with a spatial resolution close to the diffraction limit and high sensitivity [19]. With the support of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, THz imaging techniques based on Rydberg atomic vapor are under intense investigation at Shanghai Advanced Research Institute, and a 100×200-pixel capture of a 0.548 THz field was demonstrated for cesium atoms [22], achieving both a sensitivity of 43 fW/μm2 and a frame rate of 6000 fps simultaneously.

Considering the promising prospects of THz imaging, it is natural to explore THz spectroscopy utilizing Rydberg atoms, especially for potential applications in broadband THz fields generated by particle accelerators, such as the Shanghai soft X-ray free-electron laser facility [23, 24]. One potential approach is to utilize the PL spectral differences of various Rydberg states to resolve THz frequencies, which is complicated. Therefore, before establishing THz spectroscopy based on Rydberg atoms, further THz frequency-related research should be conducted on existing Rydberg systems. Currently, cesium serves as the main Rydberg atom candidate for THz field sensors. The PL characteristics of the Rydberg states of cesium atoms in relation to THz fields are not thoroughly understood. Therefore, a complete understanding of the Rydberg atomic PL spectrum of cesium is crucial.

Herein, we present a fundamental study underpinning THz spectroscopy. The PL spectra of two adjacent Rydberg states in cesium atoms that undergo THz transitions are of particular interest. Using the differential PL spectra of the Rydberg states in cesium atom vapor obtained by subtracting the PL signal with the THz field (PLWithTHz) from the PL signal without THz field (PLWithoutTHz), a rapid characterization of the THz field was performed. The effects of temperature, THz frequency, and THz intensity on the PL spectra of cesium Rydberg states were systematically measured for the first time. The dataset investigates the PL spectral mechanism of cesium atom vapor, laying the foundation for further establishing multifrequency THz spectroscopy using Rydberg atoms.

Methods and dataset

The fundamental principle of utilizing Rydberg atoms to sense THz fields is based on the resonance between the electric dipole transition frequencies of two adjacent Rydberg states and the THz frequency to be detected. Simultaneously, variations in the transition probabilities and dipole moments among the different Rydberg atomic states result in two types of spontaneous emission efficiencies. In this study, a 0.548 THz field was employed to couple the principal quantum number 14 and 13 levels in cesium atoms.

Study design

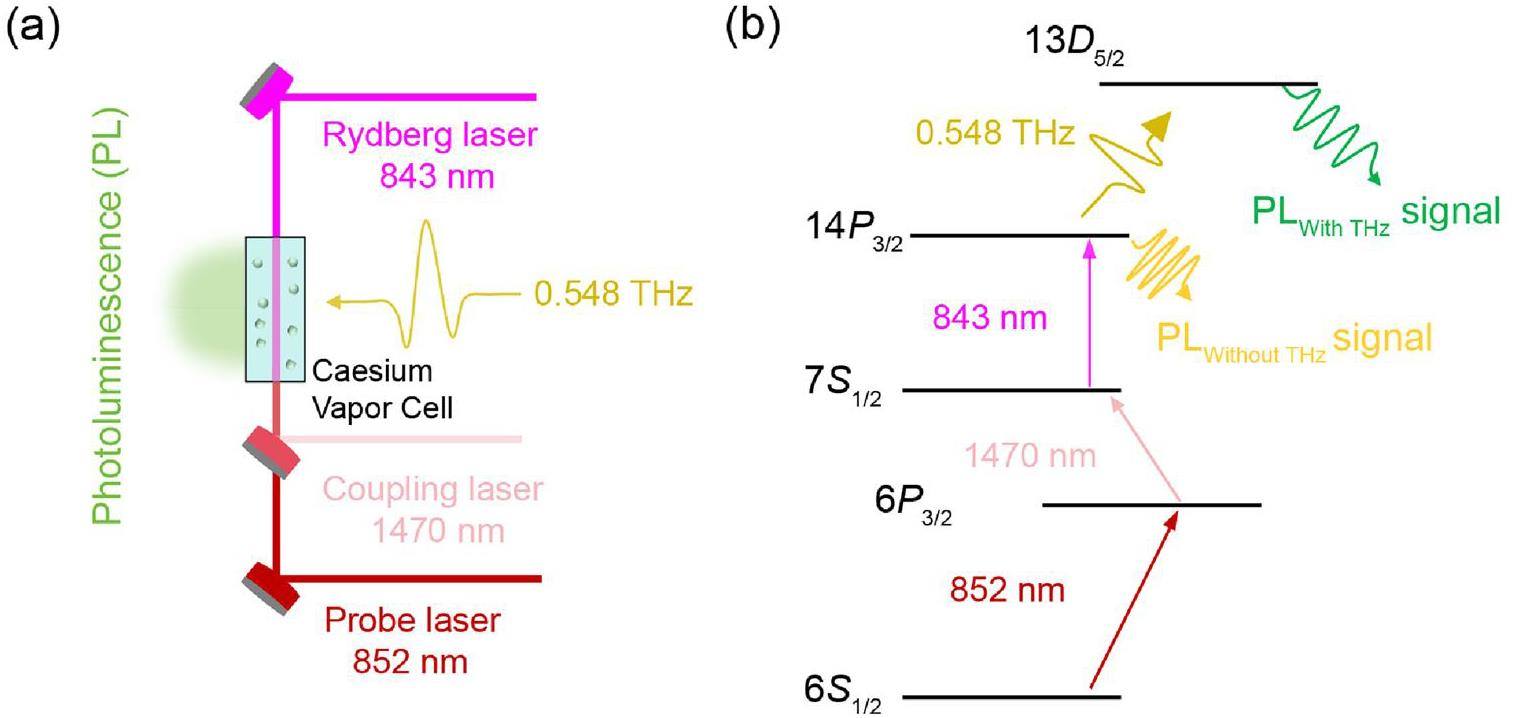

Cesium Rydberg atoms convert the difficult-to-detect THz fields into visible PL spectra. The basic principle is that the electric dipole transitions between the adjacent Rydberg states of cesium atoms lie within the THz frequency range. The spontaneous emission process of two adjacent Rydberg states has different decay pathways owing to their transition probabilities and selection rules. Therefore, the PL spectra of the two neighboring Rydberg states are crucial for detecting THz fields. In our demonstration, a rectangular vapor cell serving as a warm cesium atom Rydberg detector is shown in Fig. 1a. Three laser beams, shaped by plano-convex and plano-concave cylindrical lenses, define an interaction region filled with cesium atoms via thermal atomic motion inside the vapor cell. In the region where the THz field and laser beams coexist, the atoms are excited to the final Rydberg state by the THz field and then fluoresce as they decay in the visible PL signal.

Figure 1 a shows schematic diagrams of a 5-level energy ladder of cesium atoms and lasers, where three laser beams excite cesium atoms to a Rydberg state, and the THz field further excites the cesium atoms to the final Rydberg state. The probe laser (5 mW at 852 nm) is tuned between the ground 6P1/2 state and 6P3/2 state, while the coupling laser (20 mW at 1470 nm) and Rydberg laser (200 mW at 843 nm) are coupled to the 6P3/2 →7S1/2 and 7S1/2 → 14P3/2 transitions, respectively. The final Rydberg state 14P3/2 → 13D5/2 transition is in the THz field (548.613 GHz at 1.58 mW). In contrast to previously presented THz detection schemes, this scheme is used to sense the THz field through the PL signal.

In the absence of the THz field, the populated 14P3/2 state emits spontaneous decay containing visible fluorescence, which is referred to as the “PLWithoutTHz” signal. In contrast, when the THz field is present, the population is transferred to the 13D5/2 state by the THz field, and the PL signal emitted from the decay of the 13D5/2 state is designated as the “PLWithTHz” signal (Fig. 1b).

Experimental set up

To strictly control the quality and availability of the dataset, a detailed introduction to the system parameters is required. The filling vapor cell pressure employed in the cesium atomic vapor was maintained at 10-4 Pa [25]. The dimensions of the cesium atomic vapor cell were 1 cm ×1 cm × 2 cm, with a laser path length of 1 cm and a quartz wall thickness of 1 mm. The sealed cesium atomic vapor is heated to approximately 62.5 ℃ to increase the vapor pressure and optimize the PL signal [19].

The strategy to excite cesium atoms to Rydberg states involves a three-step excitation process, after which THz further excites these atoms to the final Rydberg state. The probe laser was generated using an external cavity semiconductor laser (ECL801). This laser was operated at a wavelength of 852 nm with a power output of 5 mW. The coupling laser used was a Distributed Bragg Reflector semiconductor laser with a wavelength of 1470 nm and a power of 20 mW. The Rydberg laser used was a Tapered Amplifier laser (TAL801 and ECL801) with a wavelength of 843 nm and a power of 200 mW. The laser beam was shaped using a plano-concave cylindrical lens and a plano-convex cylindrical lens, creating a 1 cm × 1 cm two-dimensional light sheet in atomic vapor. All lasers used in the experiment were purchased from Uniquanta Co., Ltd. The frequency range of the THz source is between 535 GHz and 570 GHz. It is equipped with a WR-1.5 DH rectangular standard waveguide as the output port, which provides a power of 1.58 mW.

The PL spectra were measured using a HORIBA iHR320 spectrometer and a charge-coupled device (CCD, SYNCER-1024 × 256). The spectrometer grating has a groove density of 1800 g/mm, achieving a resolution of ∼0.05 nm. The spectrometer and CCD system were calibrated using a mercury lamp as a standard light source. The testing range for the cesium atomic PL spectra was 450–730 nm.

Quality control and existing use of data

An alkaline Rydberg calculator (ARC) was used to calculate the laser and corresponding energy levels of the excited cesium atoms, ensuring the rationality of the experiment. To ensure data quality, the equipment underwent standard spectral calibration, and multiple measurements were conducted on the obtained data to verify consistency. The evaluation of the test results involved the use of an ARC calculator for the rationality analysis of the PL spectral data, ensuring that the data were valid. The relevant data has been published in the Science Data Bank, and a complete overview of the dataset, including the “title”, “description”, “data”, and “information”.

Data Records

Photoluminescence spectra

To verify the performance of cesium atom THz detectors and understand the detection mechanism of cesium atoms in the THz field, we conducted experiments on the PL spectra of the adjacent Rydberg states. The PL spectra have also been shown to affect the vapor cell temperature, THz frequency, and THz field intensity. In the differential PL spectra, a positive signal signifies an increase in PL spectra intensity caused by the transfer to the final Rydberg state and an increase in transition probability, whereas negative signals indicate a decrease in PL signal due to the population transfer to the final Rydberg states.

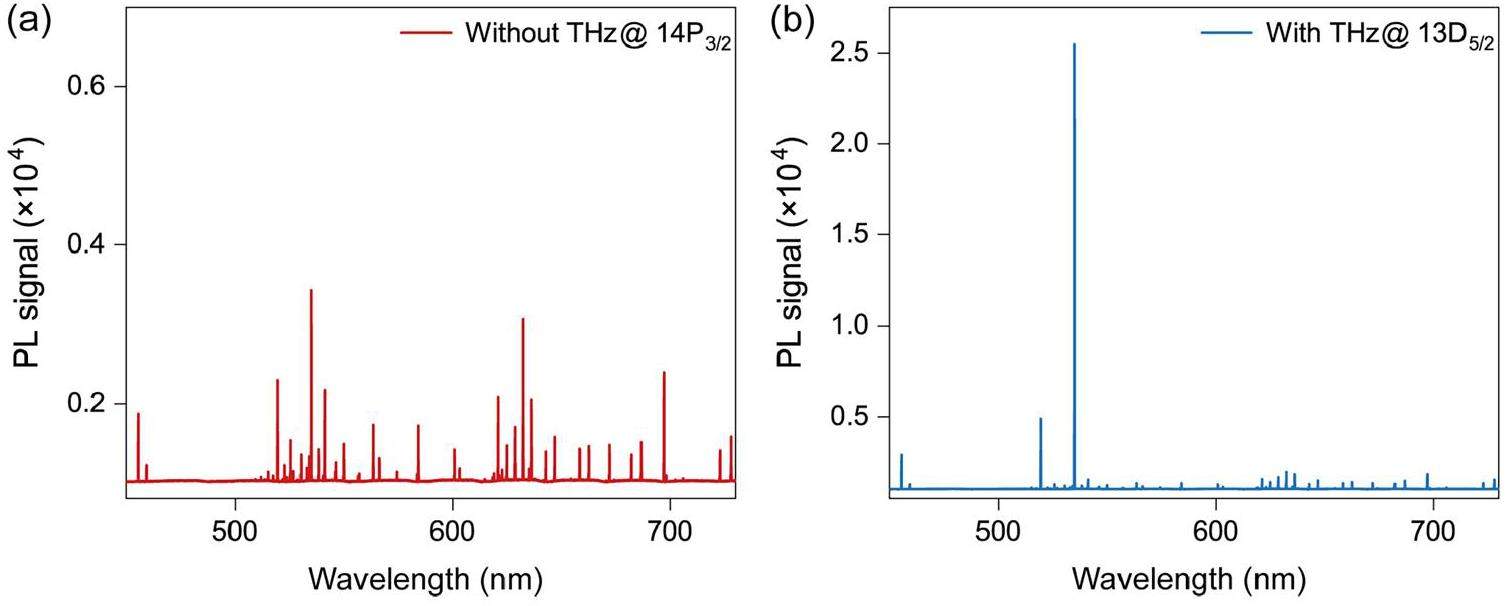

Figure 2a illustrates the excitation of cesium atoms’ PL spectra by the three lasers in the absence of a THz field, covering the range of 450–730 nm. The PLWithoutTHz signal of the excited cesium atom has peaks at 534.9 nm and 632.2 nm. This result indicates that the population transfers from

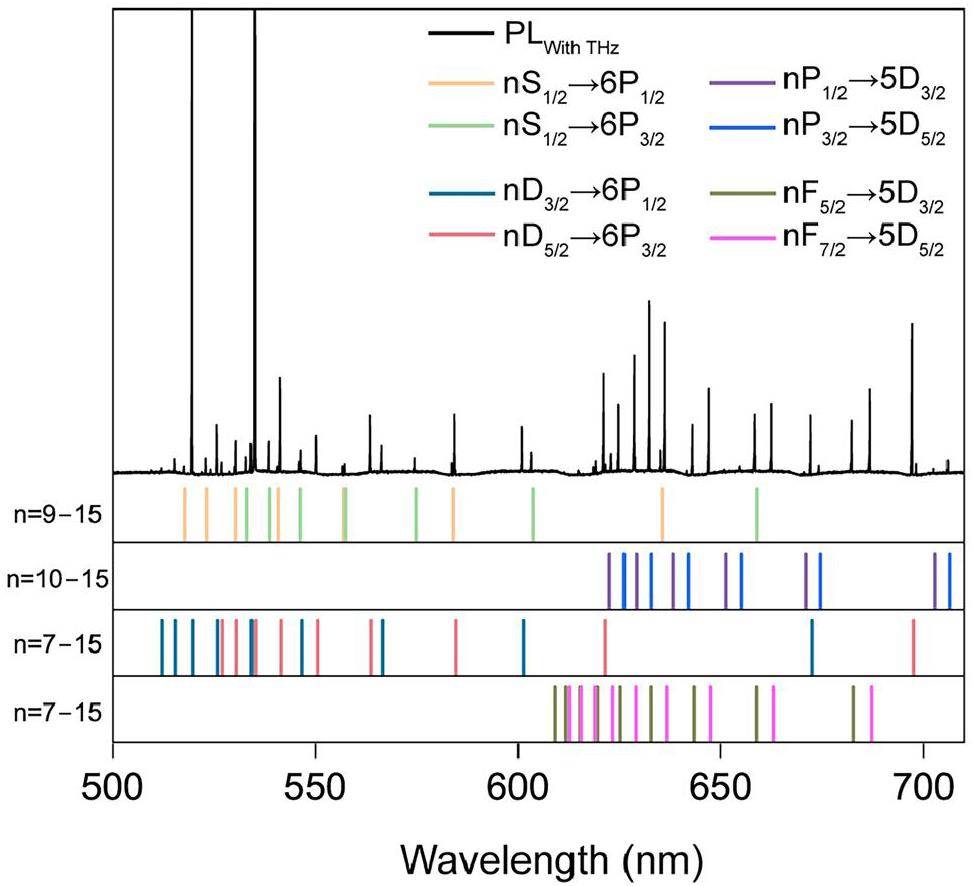

To better understand the correspondence between the spectra and the decay pathways, the transition channels in the PL spectra were calculated using ARC. The peaks of the PL spectra were identified based on the potential decay pathways and grouped according to the different channels (Fig. 3). The black curve in Fig. 3 represents the PLWithTHz spectra, which cover the PL spectra in the range of 500–730 nm. The vertical lines in different colors correspond to the wavelengths of the calculated transition channels. The first row of vertical lines illustrates the decay pathways from nS1/2 to 6P1/2 and nS1/2 to 6P3/2 (n=9-15). The second row shows the decay pathways from nP1/2 to 5D3/2 and nP3/2 to 5D5/2 (n=10-15). The third row corresponds to the decay pathways from nD3/2 to 6P1/2 and from nD5/2 to 6P3/2 (n=7-15). The fourth row shows the decay pathways from nF5/2 to 5D3/2 and nF7/2 to 5D5/2 (n=7-15). Notably, most peaks in the measured spectra were accounted for in the calculations.

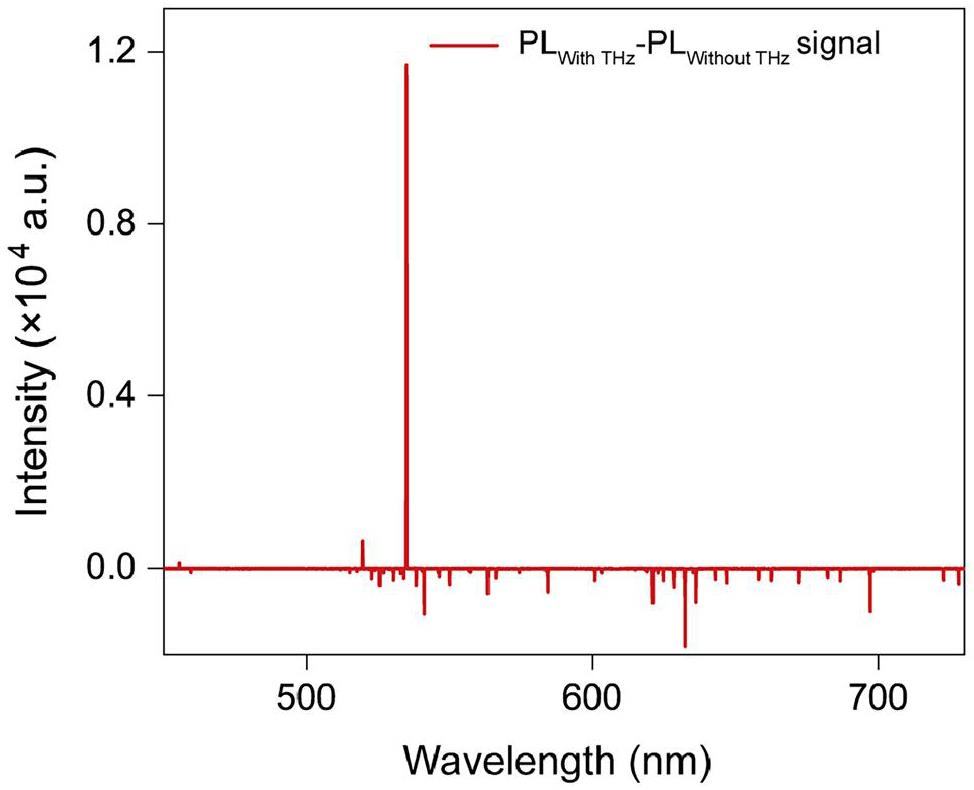

It is noteworthy that, at 534.9 nm of cesium atoms, the peaks of PLWithTHz and PLWithoutTHz signals display a significant difference in signal intensity, suggesting a diverse transition efficiency for the PL spectra of 14P and 13D states. The THz-induced PL characteristic spectra of cesium atoms can be expressed as the PLWithTHz spectra subtracted from the PLWithoutTHz spectra (Differential PL spectra, Fig. 4). The results of representative processed PL spectra are provided at several different intensities in Fig. 4, where the enhanced PL signals are at 519.6 nm and 534.9 nm, while the other PL peaks are all attenuated signals. For the THz field-induced case, the differential PL spectra of the 14P3/2 and 13D5/2 states arise from the variations in the transition probabilities and electric dipole moments, resulting in differing efficiencies of the decay channels. Thus, these differential PL spectra can serve as a fingerprint spectrum for a 0.548 THz field.

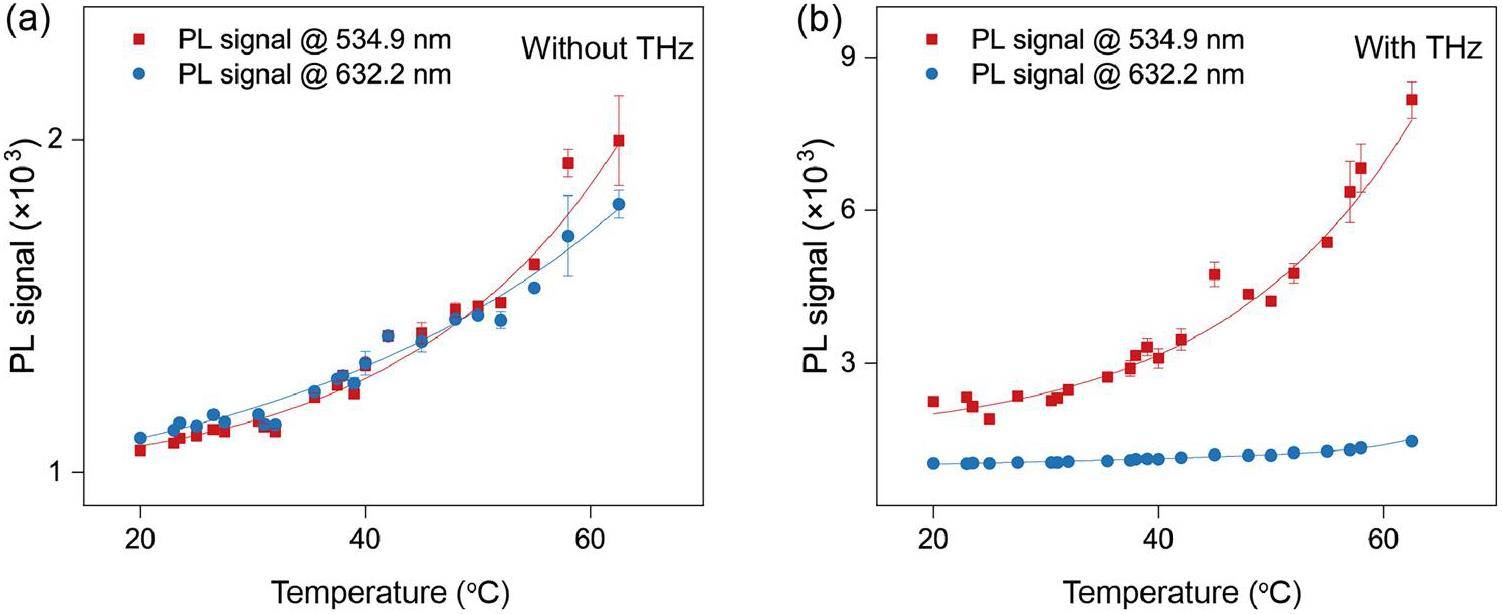

Figure 5a shows the PL spectra of cesium atoms without the THz field, spanning the range of 20–62.5 ℃. The PL signal peak at 534.9 nm and 632.2 nm rises with increasing temperature. It is worth noting that the PL signal intensity at 632.2 nm (20–45 ℃) is stronger in the lower temperature range. As the temperature increases, the PL signal at 534.9 nm gradually exceeds the 632.2 nm signal peak at the same temperature (>45 ℃). However, in the case of the THz field, both the 534.9 nm signal and the 632.2 nm signal show a phenomenon where the PL signal becomes stronger as the temperature increases, and the 534.9 nm signal peak is greater than the 632.2 nm signal peak at any temperature in Fig. 5b. Therefore, these results suggest that higher temperatures facilitate the distinction of the 534.9 nm signal from other signals.

Evolution of PL with THz Detuning and Detector Sensitivity

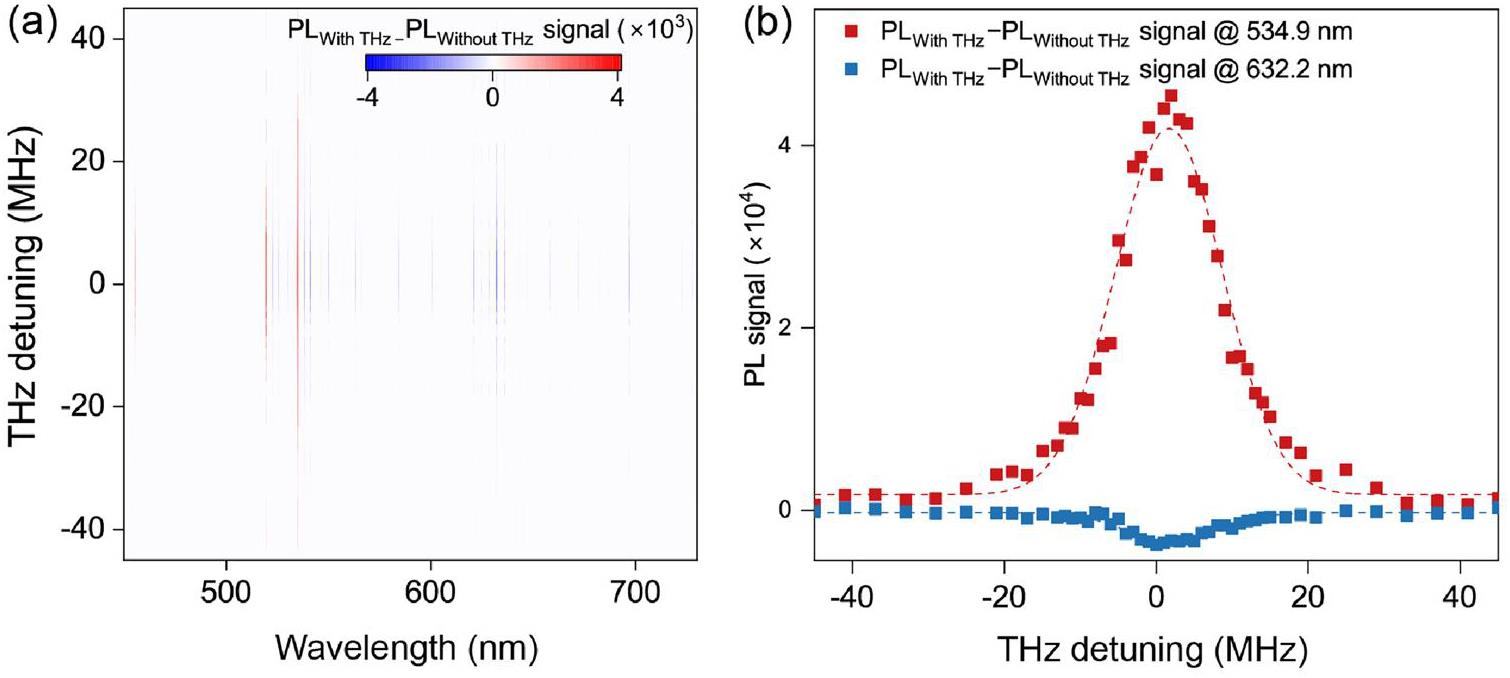

To investigate the influence of varying THz detuning on the PL spectra, the differential PL spectra evolution under THz detuning was characterized, as shown in Fig. 6a. The red-shaded area represents signals in which the differential PL signal is positive when the THz field is tuned. The blue-shaded area corresponds to the signal where PL spectra are suppressed and the differential PL signal is negative. When the THz field is present, the maximum enhanced peaks of the PL signal are 534.9 nm and 519.3 nm, corresponding to the strongest emission lines (decay from the 13D state) at a center frequency of 548.613 GHz. The suppressed PL spectra correspond to the emission lines present in the PL spectra without the THz field (decay from the 14P state). To determine the THz-responsive linewidth, differential PL spectra at THz frequency detuning were recorded, extracting the intensity of the 534.9 nm and 632.2 nm signals as a function of the THz frequency, as shown in Fig. 6b. Based on this result, the PL spectra with THz frequency detuning displayed a full width at half maximum (FWHM) value of approximately 14 MHz.

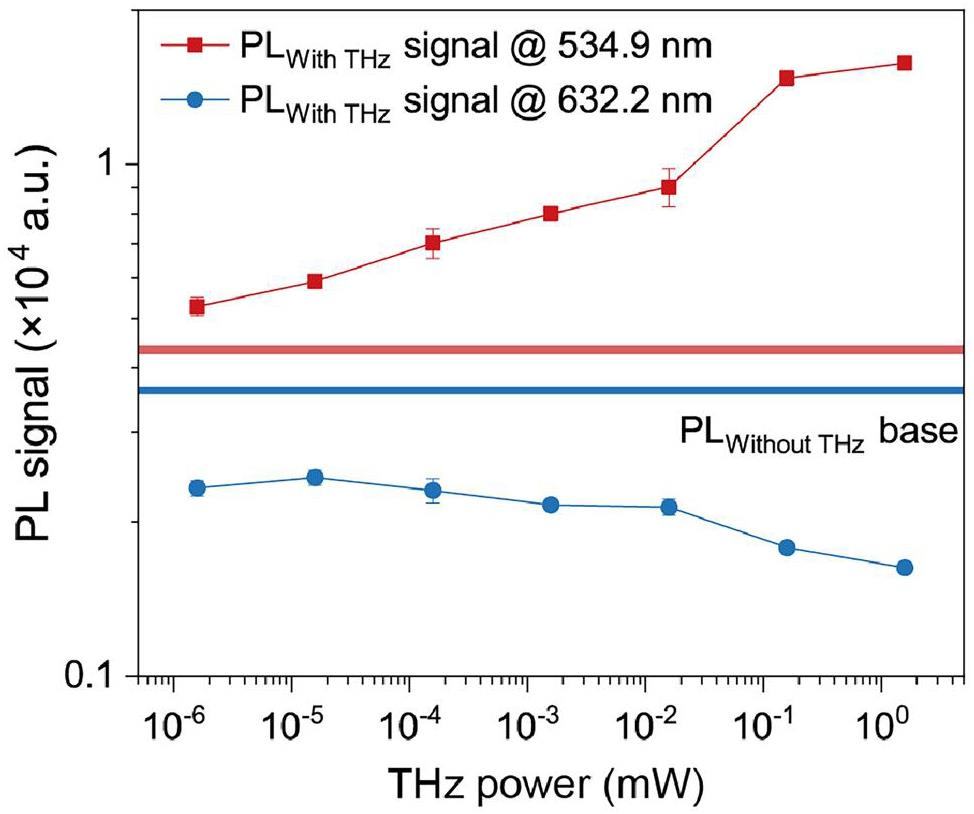

The PL spectra of cesium atomic Rydberg states are sensitive to the THz field, and the PL spectral intensity was measured at different THz intensities, as shown in Fig. 7. The signal intensity of the cesium Rydberg atom at 534.9 nm increases with an increase in terahertz intensity, whereas the 632.2 nm signal diminishes as THz intensity increases. This observation indicates a robust dependence of the decay channels on THz intensity. Furthermore, at a THz intensity of ∼10-6 mW, the 534.9 nm signal continues to exhibit a distinct difference from the PLWithoutTHz base, while the 632.2 nm signal demonstrates a significantly lower intensity than the PLWithoutTHz base, thereby achieving commendable resolution capability with respect to

Basic Information of the Dataset

Rydberg atoms have been extensively studied in areas such as THz imaging. PL spectroscopy was combined with the imaging and testing of the PL spectra while simultaneously recording the THz spectroscopic detection. Therefore, the impact of the atomic vapor cell temperature, THz intensity, and THz frequency detuning on the PL spectra is important. The supporting data for a clear presentation of the dataset and experimental operations were recorded, as shown in the Specifications Table 1.

| Subject | Nuclear physics |

| Specific subject area | Atomic molecular and optical physics |

| Data format | .dat and .ai |

| Type of data | Raw and analyzed |

| How data were acquired | Measurements were performed using a HORIBA iHR320 spectrometer and a SYNCER-1024×256 CCD. |

| Parameters for data collection | Tested with an exposure time of 2 or 0.5 seconds and a slit width of 20 or 200 μm. |

| Description of data collection | |

| Data collection | Data were collected by saving CCD. |

| Data source location | Institution: Shanghai Advanced Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences |

| Country: China | |

| Data accessibility | Repository name: Science Data Bank |

| Data identification number: https://cstr.cn/31253.11.sciencedb.16313 | |

| Direct URL to data: https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.16313 |

Dataset location

The datasets contained both raw and analyzed data. All datasets for this study have been uploaded to the “Science Data Bank” as a separate .zip file. (https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.16313https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.16313)

Dataset name and format

The data contained a file of two classes: (1) the data, including both raw data and analyzed data (file format: .dat). (2) This file contains all the original files for the drawings and is in. ai format. All files are provided in English. After obtaining written permission from the Science Data Bank, the data were used publicly for academic research and teaching purposes.

Data Content

The “data” index has five files, containing the raw data and analyzed data with corresponding file names of “raw” and “analyzed”. Figure 2 shows the raw and analyzed atomic PL spectra with and without the THz field. Figure 3 includes the raw and analyzed data of the differential PL spectra. The file in Fig. 4 contains the raw data and original PL spectra data at temperatures ranging from 20 to 62.5 ℃, both with and without THz field conditions. Figure 5 shows the analysis data of cesium atomic PL spectra with and without THz detuning. Figure 6 shows the raw cesium atomic PL spectra and the analysis data at different THz field intensities.

Recommended repositories to store and find data

Technical Validation

The Rydberg state of cesium atoms was achieved by laser frequency locking using 852-, 1470-, and 843 nm lasers to match the excitation frequency with the cesium atom resonance transition frequency. The 852 nm probe laser was scanned using a piezoelectric ceramic module to adjust the laser output frequency to match the cesium atom resonance transition frequency. For the 1470 nm coupling laser, the EIT locking method was used for frequency locking. A modulation signal was added to the 843 nm laser, and the error signal caused by the laser was extracted by a phase-locked amplifier and fed back into the laser for frequency locking. The PL spectra were collected using a plano-convex lens in free space and entered the spectrometer slit. The spectrometer was set with a 20 μm slit width in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4, with an exposure time of 1 s. The slit width in Fig. 5 is 200 μm, with an exposure time of 0.5 s. The THz field was delivered to a vapor cell in free space.

Usage Notes

THz radiation has broad application prospects in imaging and spectroscopy. The use of the PL spectral differences of Rydberg atoms to achieve THz frequency resolution is a new and validated feasible method. By utilizing the differential PL spectroscopy of Rydberg atoms, this method can be used for THz imaging and THz spectroscopy. The dataset includes PL spectra for identifying a 0.548 THz field, differential PL spectra, PL spectra under THz detuning, and provides differential PL spectra at different frequencies, offering reusable data for researchers. The data in this dataset is in .dat format, which can be opened and directly used by the vast majority of data-processing software. The dataset was uploaded to the Science Data Bank, and both raw and processed data in the database are readily usable without the need for further software processing. In the database, the x axis of the raw data represents the PL spectrum wavelength, whereas the y axis represents the PL intensity.

Resonant and nonresonant control over matter and light by intense terahertz transients

. Nat. Photonics 7, 680-690 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2013.184Review of terahertz photoconductive antenna technology

. Opt. Eng. 56,Tunable few-cycle coherent terahertz radiation with watt-level power from relativistic femtosecond electron beam

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 693, 23-25 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2012.07.034Real-time, subwavelength terahertz imaging

. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 43, 237-259 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-matsci-071312-121656Consecutively strong absorption from gigahertz to terahertz bands of a monolithic three-dimensional Fe3O4/graphene material

. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 1274-1282 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b17654Applications of terahertz spectroscopy in biosystems

. ChemPhysChem 8, 2412-2431 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.200700332Terahertz pulsed spectroscopy of freshly excised human breast cancer

. Opt. Express 17, 12444-12454 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.17.012444Detection of single-base mutation of DNA oligonucleotides with different lengths by terahertz attenuated total reflection microfluidic cell

. Biomed. Opt. Express. 11, 5362-5372 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1364/boe.400487Reflective terahertz imaging of porcine skin burns

. Opt. Lett. 33, 1258-1260 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.33.001258Security applications of terahertz technology

. SPIE 5070, 44-52 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.500491Terahertz channel propagation phenomena, measurement techniques and modeling for 6G wireless communication applications: A survey, open challenges and future research directions

. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 24, 1957-1996 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2022.3205505An overview of signal processing techniques for terahertz communications

. P. IEEE 109, 1628-1665 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2021.3100811Terahertz band communication: An old problem revisited and research directions for the next decade

. IEEE T. Commun. 70, 4250-4285 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2022.3171800Recent developments in terahertz wave detectors for next generation high speed terahertz wireless communication systems: A review

. Infrared Phys. Techn. 141,A review of terahertz detectors

. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 52,Terahertz electrometry via infrared spectroscopy of atomic vapor

. Optica 9, 485-491 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.456761A practical guide to terahertz imaging using thermal atomic vapor

. New J. Phys. 25,Real-time near-field terahertz imaging with atomic optical fluorescence

. Nat. Photonics 11, 40-43 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2016.214Full-Field Terahertz Imaging at Kilohertz Frame Rates Using Atomic Vapor

. Phys. Rev. X 10, 11027 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.10.011027Ultra-wide dual-band Rydberg atomic receiver based on space division multiplexing radio-frequency chip modules

. Chip 3,Atomic receiver by utilizing multiple radio-frequency coupling at Rydberg states of rubidium

. Appl. Sci. 10, 1346 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/app10041346Double cameras Terahertz Imaging with Kilohertz frame rates and high sensitivity via Rydberg-atom vapor

. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 58,A strong-field THz light source based on coherent transition radiation

. Front. Phys. 11,Generating high-power, frequency tunable coherent THz pulse in an X-ray free-electron laser for THz pump and X-ray probe experiments

. Photonics 10, 133 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics10020133Revisiting collisional broadening of 85Rb Rydberg levels: conclusions for vapor cell manufacture

. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.16669Hai-Xiao Deng is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.