Introduction

Collective phenomena have long been considered crucial signatures for the formation of a deconfined state of nuclear matter, quark-gluon plasma (QGP), in high-energy heavy-ion collisions [1-5]. However, in recent years, a flood of similar collectivity-like features has been observed in smaller systems, namely, high-multiplicity proton–proton (pp) and proton–nucleus (pA) interactions at the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider and Large Hadron Collider (LHC) [6-12]. These findings, which are largely unanticipated for such small systems, indicate potential similarities between the collective behaviors observed in small and large systems, demanding a paradigm shift in our understanding of QGP [13, 14]. Investigating the system size dependence of these collectivity phenomena is an important way to understand the properties of deconfined quark matter created during different collision processes.

The system sizes of different collisions can be effectively classified based on the event multiplicity, frequently represented by the final-state charged-particle pseudorapidity density measured at midrapidity

Distinguishing modifications to the hadron production process, such as baryon-to-meson fraction changes, were initially investigated using hadrons consisting of light-flavor quarks. The resemblance of light-flavor hadron production between high-multiplicity pp and heavy-ion collisions in the soft regime stimulates the application of hydrodynamic and thermodynamic modeling to describe bulk particle yields in small systems [22-28]. The measured relative abundances of the created particles can be used as important experimental inputs to constrain the temperature, chemical potential, and volume of the matter produced in pp collisions [29-32]. Another phenomenological modeling approach often relies on a modified string fragmentation framework implemented based on the multi-parton interaction (MPI) assumption [33-38]. Researchers expect that inter-string effects can be sizable in a dense environment with multiple MPI string systems overlapping in the coordinate space. The color reconnection and rope hadronization effects implemented in the PYTHIA8 model successfully described the multiplicity dependence of the flow-like behavior of particle spectra in pp collisions [33, 39, 40].

Recently, similar multiplicity-dependent measurements have been extended to charm hadrons in high-energy pp collisions, and a sizable enhancement of the baryon-to-meson ratio

In this work, we employed the string-melting AMPT model built on PYTHIA8 initial conditions, including the final-state interactions and parton coalescence mechanism, to study the multiplicity-dependent hadron production of various flavors. The AMPT model with PYTHIA8 initial conditions was observed to describe the hadron yield in the soft regime and multiparticle correlations reasonably well [51, 52]. Being capable of delivering the final-state rescattering effects at both partonic and hadronic levels, the AMPT model provides an important method to test the final-state effects for hadron production from light to heavy flavors in the presence of deconfined parton matter. We compared the AMPT results to the string fragmentation model calculations in the multiplicity-dependent flavor hierarchy of hadron production to demonstrate the key features of these two widely used physics assumptions for small system collectivity studies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: we explain the model setups for the AMPT model and the color reconnection included string fragmentation model in Sect. 2. The results of the model calculations are presented and compared with experimental data in Sect. 3. We summarize the major conclusions and discuss future applications in Sect. 4.

Method

In this study, we used the AMPT model based on the PYTHIA8 initial conditions to explore the final-state interaction effects on hadron production with different flavor components. The string-melting AMPT model consists of four major components: fluctuating initial conditions, final-state parton transport interactions, a coalescence hadronization model, and final-state hadronic cascade interactions. The event-by-event fluctuating initial conditions for the subsequent evolution stage were generated using PYTHIA8 [53] embedded with the spatial structure at the sub-nucleon level. After propagating the initial string system to their formation time and converting them to the constituent valence quark components, the resultant quark system may experience the parton evolution stage with the microscopic scattering process implemented by Zhang’s parton cascade (ZPC) model [54], with a two-body scattering cross section σ frequently determined by comparison with anisotropic flow data. In this study, the value of the parton scattering cross section was set to

In this study, we turned on the parton and hadron final-state transport mechanisms in a step-by-step manner to explore the effects developed in different evolution stages. When both parton and hadron rescattering were disabled, the results were labeled as “noFSI” (no final-state interaction), whose behavior should be similar to the pure PYTHIA string fragmentation predictions without any collective effect. If the parton rescattering stage was enabled while hadron rescatterings are excluded, it was denoted as the “pFSI” case (partonic final-state interaction). When both final-state parton and hadron rescattering effects were included, the results were indicated as “allFSI” (all final-state interaction), in which the evolving system experienced the entire partonic and hadronic evolutions.

Collectivity-like behavior in small systems can also be induced by modified string fragmentation models that consider inter-string effects when a significant number of string pieces overlap in the limited transverse space [39]. The color reconnection (CR) model has been found to reasonably reproduce inclusive baryon-to-meson ratios with different flavors [37, 40, 42, 45]. In this study, we employed the beyond leading color (BLC) CR model built in the PYTHIA8.309 package [53], in which strings are allowed to form between both leading and non-leading connected partons [61]. With the possibility of forming junctions in BLC CR as an additional source for baryon production, multiplicity-dependent baryon enhancement is observed in this model [33]. We compared the AMPT calculations with the results from the CR model to explore the difference between these two underlying physical mechanisms. The parameters of the CR model used in this study were set by following the procedure described in Ref. [40, 62].

Results

This work focused on the hadron productions in pp collisions with

Inclusive particle production

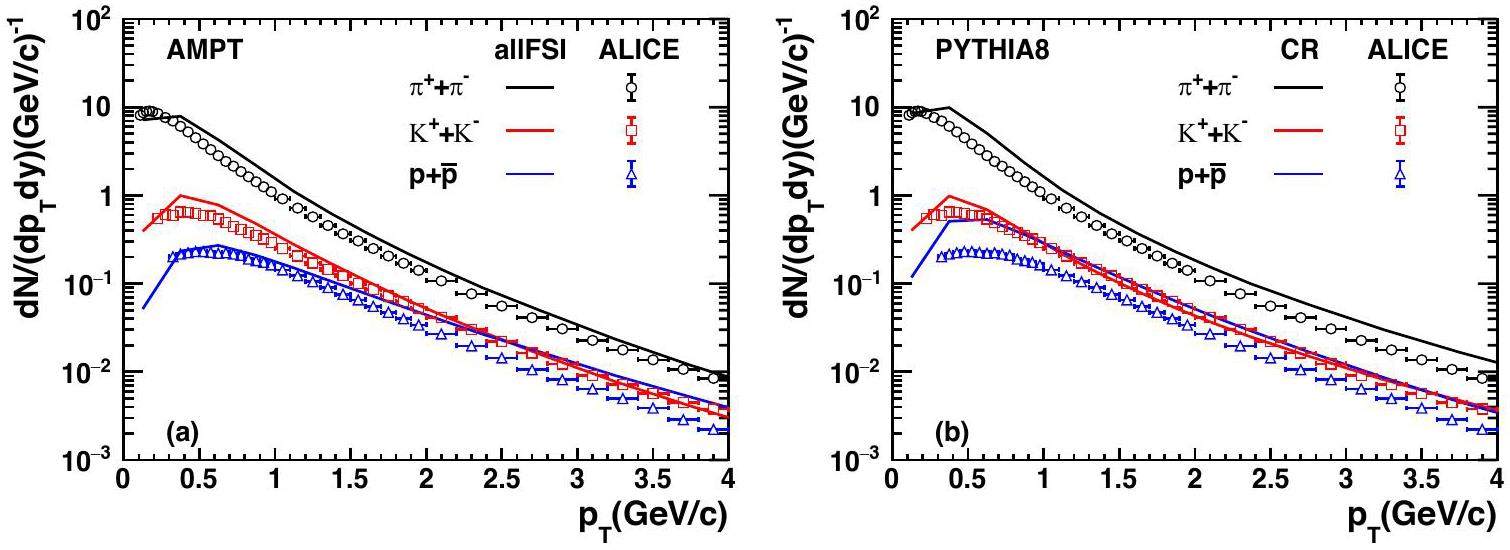

The data for all light-flavor particles in this paper represent the sum of particles and anti-particles, whereas the data for heavy-flavor particles are the sum of particles and anti-particles divided by 2, following experimental analysis conventions. For inclusive hadron production, events were selected according to the minbias trigger used in the ALICE experiment, which requires signals accepted by either side of the V0 detector. The transverse momentum spectra for charged pions, kaons, and protons with |y|<0.5 are shown in Fig. 1 produced in inelastic pp collisions at

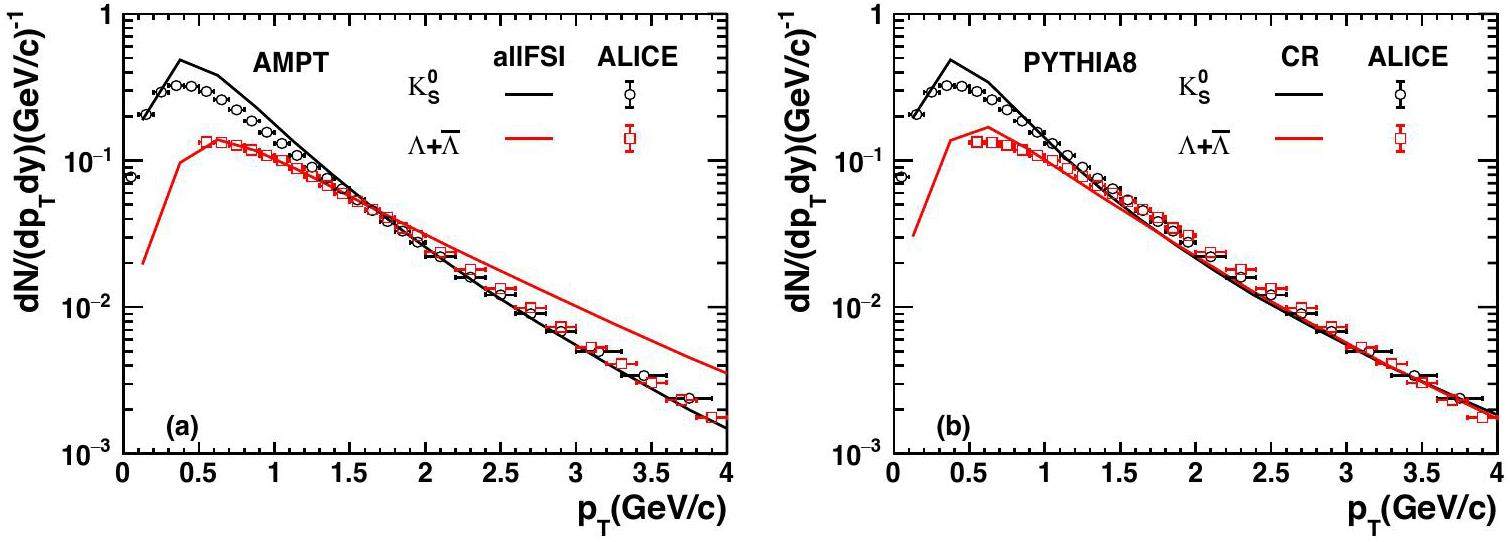

We compare the transverse momentum dependence of the neutral strange hadrons

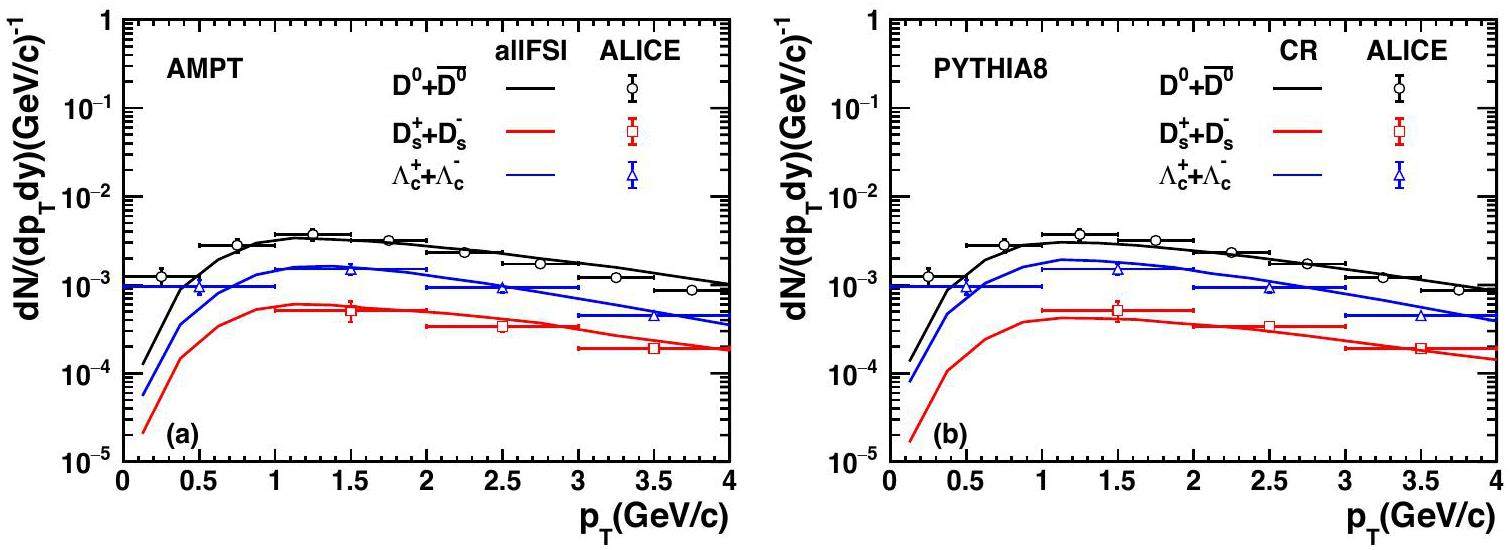

The transverse momentum spectra for D0,

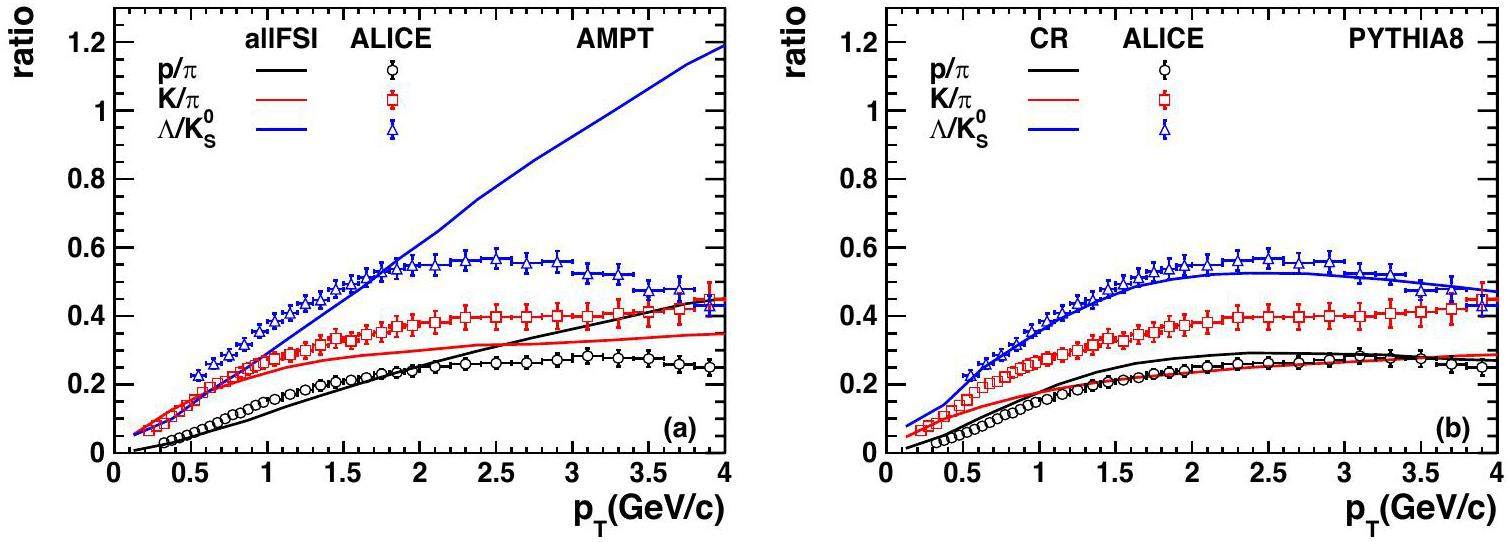

The particle ratios p/π, K/π and

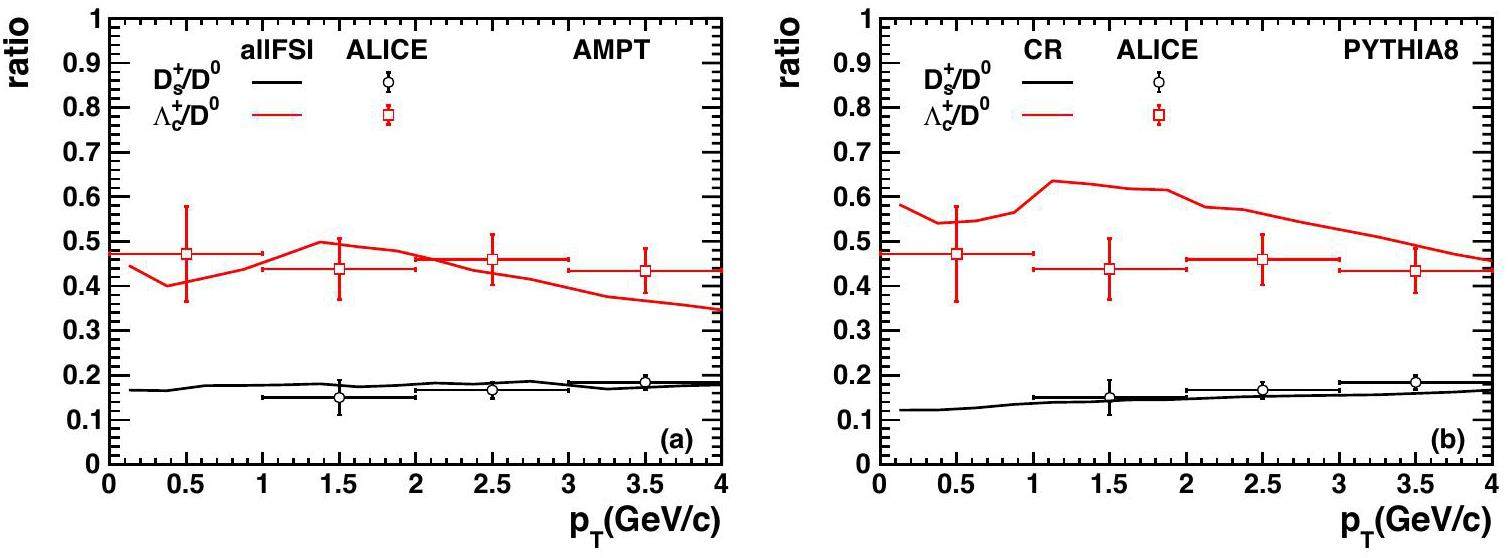

Figure 5 shows the pT dependence of the heavy-flavored particle ratios, namely

Multiplicity dependence of particle ratio

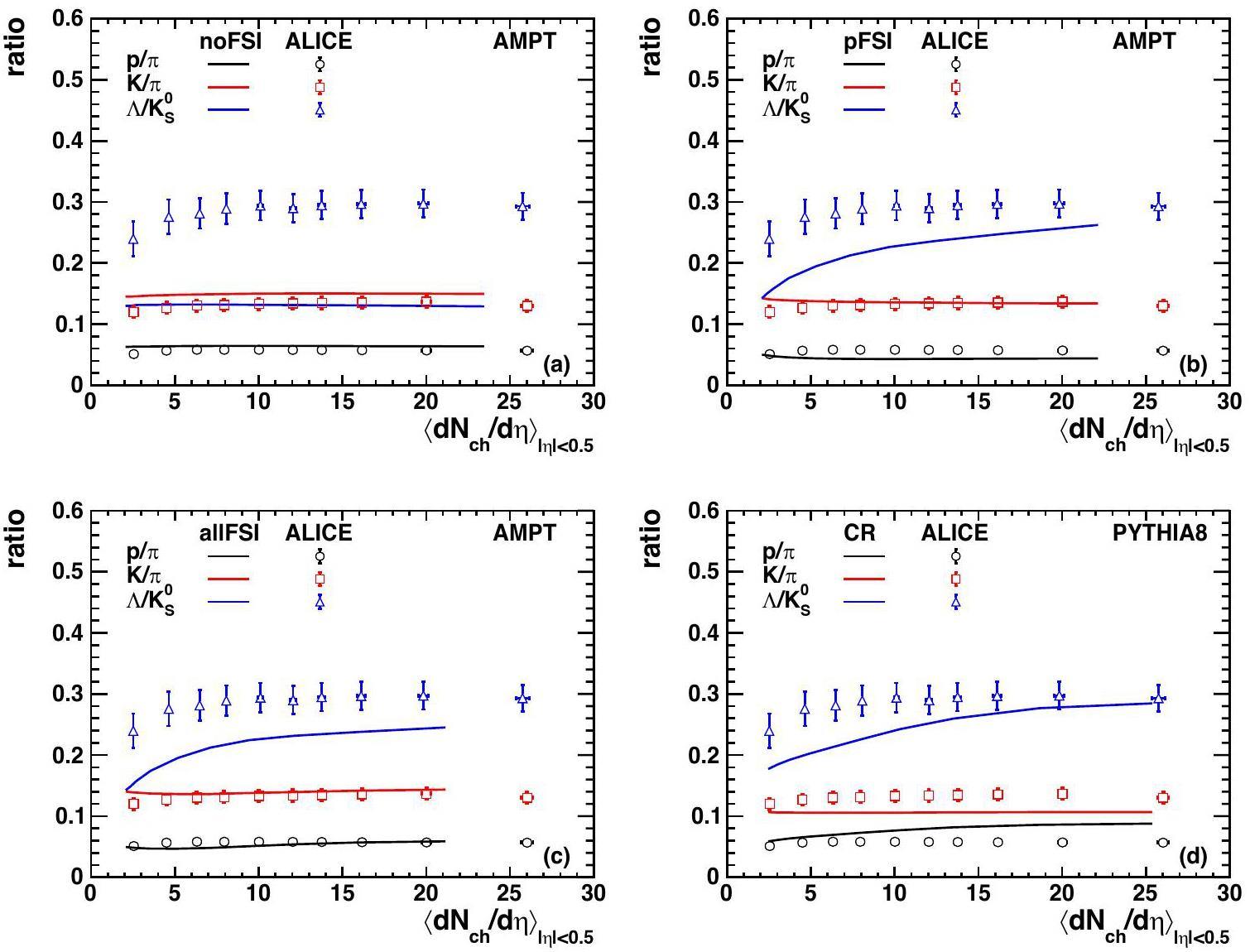

After examining the inclusive hadron production, in this section, we investigate the variations in the hadron chemical compositions by exploring the ratios of different particle species with the final-state charged particle density. Figure 6 shows the pT integrated particle ratios of K/π, p/π, and

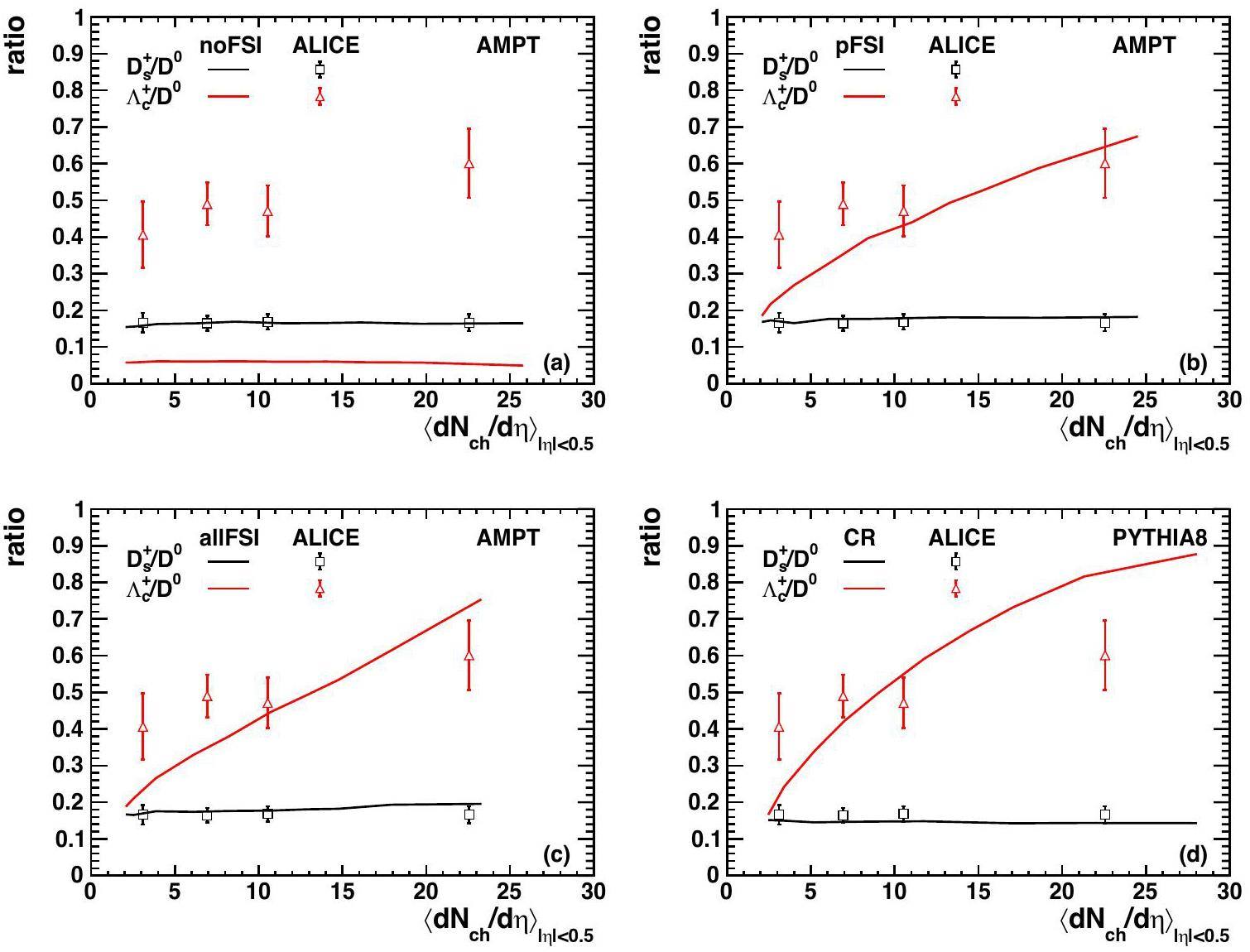

In Fig. 7, we compare the charm hadron ratios

An interesting observation was that the

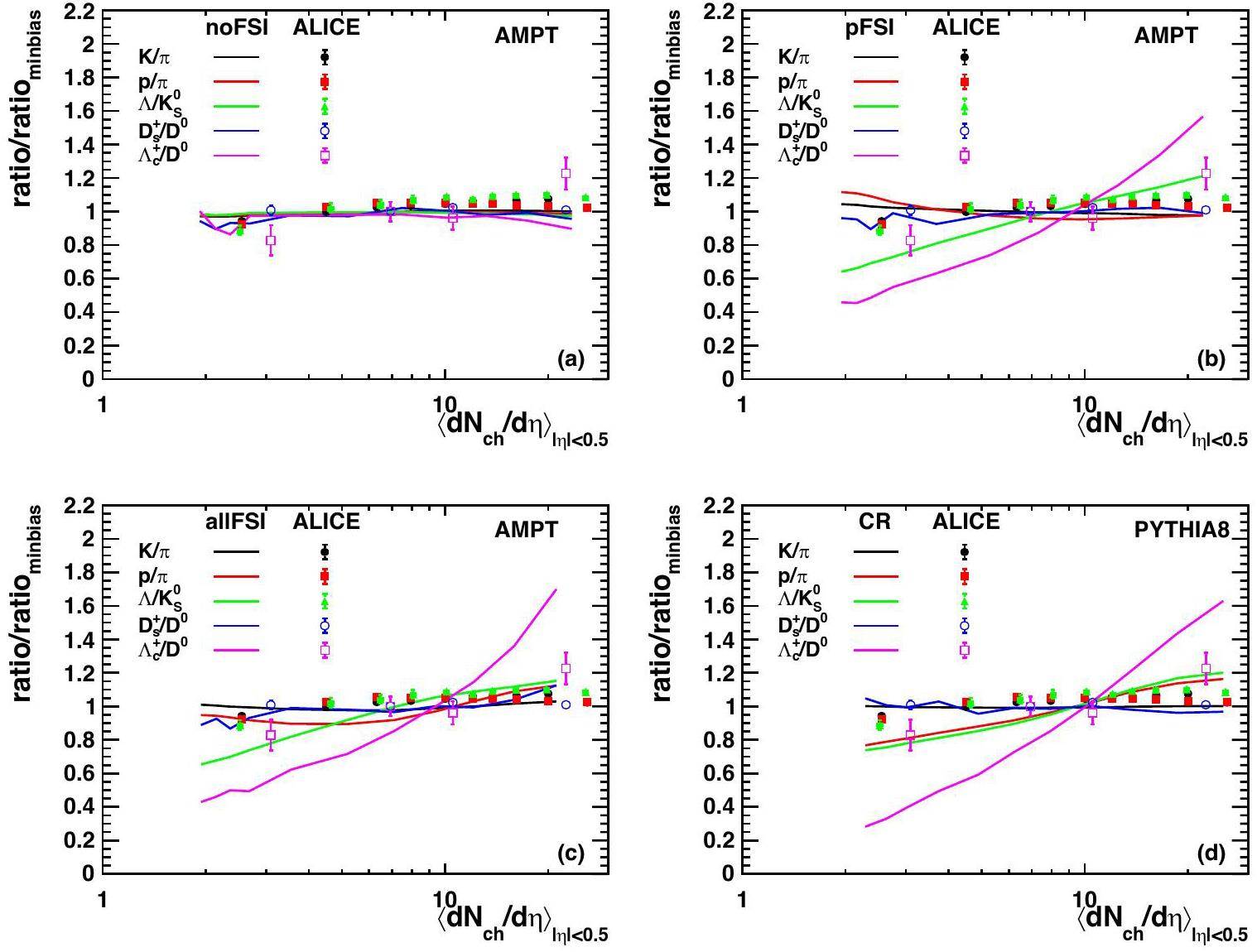

To further identify the multiplicity-dependent shape of the particle ratios with different quark flavor components, we present the self-normalized particle ratios for p/π, K/π,

Transverse momentum dependence of the double ratio

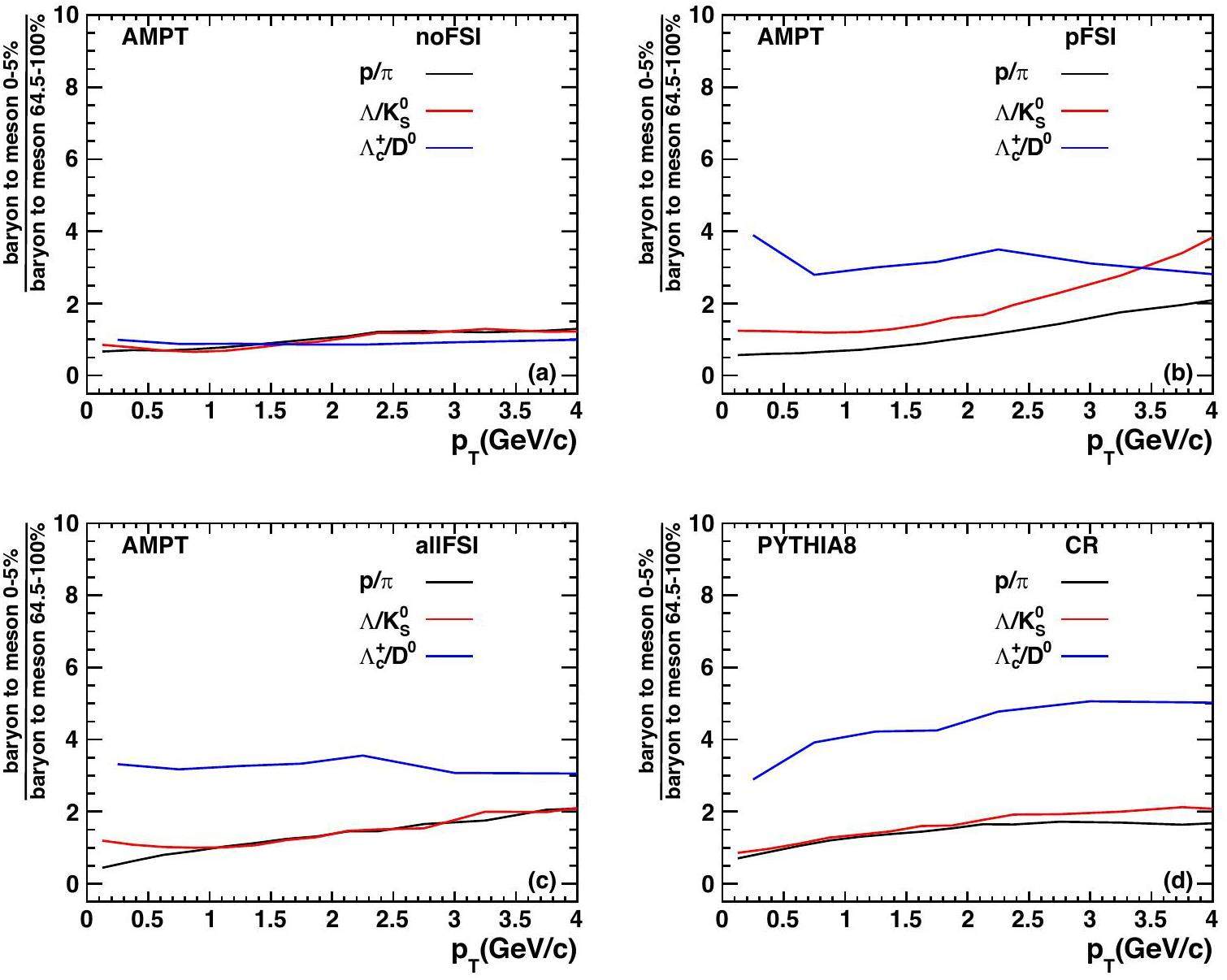

We further investigated the transverse momentum-dependent modifications to the hadron production ratios induced by the event multiplicities and present the double ratios constructed with the particle ratios from central collisions (0%–5% centrality) divided by those from peripheral collisions (64.5%–100% centrality) in Fig. 9. Because the strange-to-non-strange meson ratios K/π and

Summary

This study systematically investigated multiplicity-dependent hadron production with different flavors in proton–proton collisions at

Additionally, we observed that the final-state parton stage evolutions, in conjunction with the coalescence process, result in a pronounced multiplicity dependence for the baryon-to-meson ratios, displaying a clear flavor hierarchy. The color reconnection model predicts a similar multiplicity dependence for the baryon-to-meson ratio, although it does not clearly delineate the ordering between p/π and

The multiplicity-induced modifications to the pT shape of the baryon-to-meson ratio in the AMPT model with different quark components revealed the flavor related medium response effects in high-energy pp collisions. We believe that the discrepancy in the calculations for the flavor hierarchy in the baryon-to-meson ratio and pT shape of the meson ratio between the AMPT and color reconnection models can be important to distinguishing the hadronization mechanism at play in high-multiplicity pp collisions.

This study underscores the importance of conducting multiplicity-dependent studies while analyzing the flavor hierarchy patterns. Such an approach is essential for gaining insight into the collectivity-like effects observed in small systems.

Uniform description of soft observables in heavy-ion collisions at sNN=200

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101,Heavy ion collisions: The big picture, and the big questions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 68, 339-376 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-101917-020852The exploration of nato adv sci inst se: introduction to relativistic heavy-ion physics

. J. Phys. G 50,QGP Signatures revisited

. arXiv:2308.05743Experimental study of the QCD phase diagram in ccast wl sw

. Nuclear Techniques 46,QCD challenges from pp to A–A collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 288 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00270-1Observation of long-range near-side angular correlations in proton-proton collisions at the LHC

. JHEP 09, 091 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP09(2010)091Evidence for collectivity in pp collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Lett. B 765, 193-220 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.12.009Enhanced production of multi-strange hadrons in high-multiplicity proton-proton collisions

. Nature Phys. 13, 535-539 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4111Measurement of pion, kaon and proton production in proton–proton collisions at s=7 TeV

. Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 226 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3422-9Multiplicity dependence of light-flavor hadron production in pp collisions at s=7 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Properties of QCD matter: a review of selected results from alice experiment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01583-2Small system collectivity in relativistic hadronic and nuclear collisions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 68, 211-235 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-101916-123209Progress and challenges in small systems

. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301324300054Enhanced production of multi-strange hadrons in high-multiplicity proton-proton collisions

. Nature Phys. 13, 535-539 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys4111Multiplicity dependence of π, K, and p production in pp collisions at s=13 TeV

. Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 693 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-8125-1System-size dependence of the hadronic rescattering effect at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 109,System-size dependence of the charged-particle pseudorapidity density at sNN=5.02 TeV for pp, pPb, and PbPb collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 845,Multiplicity dependence of (multi-)strange hadron production in proton-proton collisions at s=13 TeV

. Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 167 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-7673-8Multiplicity dependence of K*(892)0 and ϕ (1020) production in pp collisions at s=13 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 807,Observation of a multiplicity dependence in the pT-differential charm baryon-to-meson ratios in proton–proton collisions at s=13 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 829,Enhancement of strange baryons in high-multiplicity proton–proton and proton–nucleus collisions

. PTEP 2018,Unified description of hadron yield ratios from dynamical core-corona initialization

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Multiplicity dependence of light flavour hadron production at LHC energies in the strangeness canonical suppression picture

. arXiv:1610.03001Hydrodynamic collectivity in proton–proton collisions at 13 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 780, 495-500 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.03.022Searching for small droplets of hydrodynamic fluid in proton–proton collisions at the LHC

. Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 846 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-8376-xStudy of baryon number transport dynamics and strangeness conservation effects using ω-hadron correlations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01464-8Investigating the elliptic anisotropy of identified particles in p–Pb collisions with a multi-phase transport model

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01387-4Temperature and fluid velocity on the freeze-out surface from π, k, p spectra in pp, p-Pb and Pb-Pb collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Kinetic freeze-out temperature from yields of short-lived resonances

. Phys. Rev. C 102,System size and flavour dependence of chemical freeze-out temperatures in alice data from pp, pPb and PbPb collisions at LHC energies

. Phys. Lett. B 834,Tsallis-thermometer: a QGP indicator for large and small collisional systems

. J. Phys. G 47,Effects of color reconnection on hadron flavor observables

. Phys. Rev. D 92,A shoving model for collectivity in hadronic collisions

. arXiv:1612.05132Collectivity without plasma in hadronic collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 779, 58-63 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.01.069Setting the string shoving picture in a new frame

. JHEP 03, 270 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP03(2021)270Hadronic rescattering in pA and AA collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 57, 227 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-021-00543-3String interactions as a source of collective behaviour

. Universe 10, 46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/universe10010046Color reconnection and flowlike patterns in pp collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111,Effects of overlapping strings in pp collisions

. JHEP 03, 148 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP03(2015)148Charm production and fragmentation fractions at midrapidity in pp collisions at s=13 TeV

. JHEP 12, 086 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP12(2023)086Study of flavor dependence of the baryon-to-meson ratio in proton-proton collisions at s=13 TeV

. Phys. Rev. D 108,Λc± production in pp collisions with a new fragmentation function

. Phys. Rev. D 101,Study of charm hadronization with prompt Λc+ baryons in proton-proton and lead-lead collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. JHEP 01, 128 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP01(2024)128The dynamic hadronization of charm quarks in heavy-ion collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. C 84, 231 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-12593-0New feature of low pT charm quark hadronization in pp collisions at s=7 TeV

. Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 344 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-5817-xCharged-particle multiplicity dependence of charm-baryon-to-meson ratio in high-energy proton-proton collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 815,Charm-baryon production in proton-proton collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 795, 117-121 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.06.004Charm hadrons in pp collisions at LHC energy within a coalescence plus fragmentation approach

. Phys. Lett. B 821,Heavy flavor as a probe of hot QCD matter produced in proton-proton collisions

. Phys. Rev. D 109,Further developments of a multi-phase transport model for relativistic nuclear collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00944-5Investigating high energy proton proton collisions with a multi-phase transport model approach based on pythia8 initial conditions

. Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 755 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-021-09527-5An introduction to pythia 8.2

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 191, 159-177 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2015.01.024Zpc 1.0.1: A parton cascade for ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 109, 193-206 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(98)00010-1Disentangling the development of collective flow in high energy proton proton collisions with a multiphase transport model

. Eur. Phys. J. C 84, 1029 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-13378-1Improved quark coalescence for a multi-phase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Enhanced production of strange baryons in high-energy nuclear collisions from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Improvement of heavy flavor production in a multiphase transport model updated with modern nuclear parton distribution functions

. Phys. Rev. C 101,A multi-phase transport model for relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Formation of superdense hadronic matter in high-energy heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 2037-2063 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.2037String formation beyond leading colour

. JHEP 08, 003 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP08(2015)003Strange particle production in jets and underlying events in pp collisions at s=7 TeV with PYTHIA8 generator

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58, 53 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00709-7Production of light-flavor hadrons in pp collisions at s = 7 and s=13 TeV

. Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-08690-5Improved monte carlo glauber predictions at present and future nuclear colliders

. Phys. Rev. C 97,On the non-universality of heavy quark hadronization in elementary high-energy collisions

. arXiv:2402.03692The authors declare that they have no competing interests.