Introduction

The field of research concerning the interactions of strong laser fields with atoms and molecules has reached a considerable degree of maturity [1-3]. Recently, projects for extremely high-intensity lasers have been proposed by the Shanghai Ultra Intensive Ultrafast Laser Facility [4, 5], the Extreme Light Infrastructure for Nuclear Physics [6, 7], and a Russian group [8]. Because of the enhancements envisaged for the near future, laser-driven nuclear physics has attracted increasing interest and extensive research has been performed on, for example, the impact of laser fields on α decay [9-19], proton emission [6, 20, 12], cluster radioactivity [12, 18], nuclear fission [12], nuclear fusion [21-23], and nuclear excitation [24-26]. Among these, significant attention has been paid to the α decay of nuclei under the influence of strong laser fields.

α decay is crucial in nuclear physics because it provides information on the nuclear structure [27-29] and facilitates the understanding of topics such as the nuclear transformation between the liquid state and cluster state [30, 31]. α radioactivity was first discovered by Rutherford in 1903. Following this discovery, many attempts were made to modify α decay rates by changing the temperature, pressure, and magnetic and gravitational fields [32, 33]. The changes in the decay constant were small and could be neglected. These interpretations may stem from Gamow’s explanation of quantum-mechanical tunneling [34], according to which α decay is correlated with the width through the potential. The distortions in the potential and changes in the decay energy modified by the above experiments were negligible and no effect was detected. The remarkable developments in laser technology provide an alternative method to explore and advance this study.

Lasers interact with matter through two fundamental mechanisms: single-photon and electromagnetic field interactions. The former is not feasible for nuclear processes because of the significant energy discrepancy between a single photon (on the order of 1 eV) and nuclear energy levels (on the order of 1 MeV). When the laser intensity is sufficiently high, the laser–matter interaction is predominantly governed by the electromagnetic field [3], which is believed to possess the potential to control nuclear systems. Thus, many studies have focused on the necessity of high-intensity lasers to modify decay processes [9-19]. According to Ref. [11], no significant modification of α decay is expected with the lasers currently available or those anticipated for the forthcoming years.

However, some recent studies have indicated the substantial effect of current laser intensities on α decay by solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation within the oscillating Kramers–Henneberger frame [15-19]. Others suggest a small yet detectable influence at the current laser intensities or those that will be attained in the foreseeable future [9, 10, 12-14]. The inconsistencies in these findings highlight the ongoing debate and the lack of a clear consensus. Moreover, the temporal and angular effects and variation in the spatial shape of the laser field are intriguing for experiments; however, these remain ambiguous. In this study, we investigated the influence of extreme laser fields on nuclear α decay using the frozen Hartree–Fock (FHF) approach [35-37]. In contrast to the aforementioned approaches, it can compute the microscopic internuclear potential and deformation effects in a self-consistent manner [38-40]. Cluster radioactivity has been investigated since 1984 [41] as an intermediate process between α decay and spontaneous fission [42-44], and it has deepened our understanding of decay mechanics. Thus, it would also be interesting to study cluster radioactivity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework for laser-assisted particle decay using the FHF method. Section 3 presents and discusses the results. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions of this study.

Theoretical framework

Unified formula of half-lives for α decay and cluster radioactivity

α-decay and cluster radioactivity processes can be interpreted within a unified tunneling framework following Gamow’s depiction [44-46]. The emitted particles are assumed to preform on the surface of the parent nucleus with varying preformation probabilities [47, 48] and eventually penetrate the potential barrier by constantly hitting it. The unified formula for the half-lives of α decay and cluster radioactivity is expressed as follows:

The impinging frequency F is expressed as follows:

The penetration possibility P is determined using the Wentzel–Kramers–Brillouin (WKB) approximation. Considering the nuclear deformation effect, the total penetration possibility

| Decay channels | Qe(MeV) | l | log10Texp | log10Tcal | log10HF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 144Nd → 140Ce+α | 1.90 | 0 | 22.86 | 22.77 | 0.09 |

| 226Ra → 222Rn+α | 4.87 | 0 | 10.70 | 10.09 | 0.61 |

| 238U → 234Th+α | 4.27 | 0 | 17.15 | 17.14 | 0.01 |

| 242Cm → 238Pu+α | 6.23 | 0 | 7.15 | 6.57 | 0.58 |

| 147Sm → 143Nd+α | 2.31 | 0 | 18.53 | 18.66 | -0.13 |

| 213Po → 209Pb+α | 8.54 | 0 | -5.43 | -6.85 | 1.42 |

| 235U → 231Th+α | 4.68 | 1 | 16.35 | 14.04 | 2.31 |

| 239Pu → 235U+α | 5.25 | 3 | 11.88 | 11.46 | 0.42 |

| 222Ra → 208Pb+14C | 33.05 | 0 | 11.22 | 11.42 | -0.20 |

| 223Ra → 209Pb+14C | 31.83 | 4 | 15.04 | 13.84 | 1.20 |

| 224Ra → 210Pb+14C | 30.53 | 0 | 15.87 | 16.16 | 0.29 |

| 226Ra → 212Pb+14C | 28.20 | 0 | 21.20 | 20.93 | 0.27 |

The uniform values or formulas for the pre-formation factor Spre in Eq. (1) have been established [49-52]. For α decay, we adopt the following values [51]:

The frozen Hartree–Fock method

The nucleus–nucleus interaction potential, which consists of the nuclear potential VN and Coulomb potential Vc, is utilized to substitute the corresponding terms in Eq. (5). This potential was calculated using the FHF method, which requires frozen ground-state densities ρi of the two nuclei at all distances. The resulting nucleus–nucleus interaction potential, referred to as the FHF potential in this context, is expressed as follows:

Laser–nucleus interaction

In this context, a laser field, known as an electromagnetic field, is treated as an electric field. In fact, the magnetic part can be neglected because the subbarrier motion of the emitted particles under investigation remains nonrelativistic. Generally, the wavelength of the laser fields (near-ultraviolet to near-infrared) is much larger than the nuclear length scale (on the order of a femtometer). The dipole approximation can thus be used for the laser electric field, which is given in the length gauge as

The effect of the spatial shape of the laser on the decay processes is of interest. In this study, we consider two types of laser shapes, which are expressed as follows:

Relative change of penetration possibility ΔP

The FHF method ignores the dynamic effects and Pauli repulsion between nucleons belonging to different nuclei [40, 57]. The latter is regarded as a significant factor in the preformation of the emitted particles on the surface of the parent nucleus. Moreover, our model is incapable of calculating the preformation factor, which remains a great challenge for the beyond-mean field theory. Therefore, this work focuses on the relative change in the penetration possibility induced by the laser field while ignoring the impact of the laser field on the preformation factor [11-14]. The relative change in the penetration possibility is defined as

Results

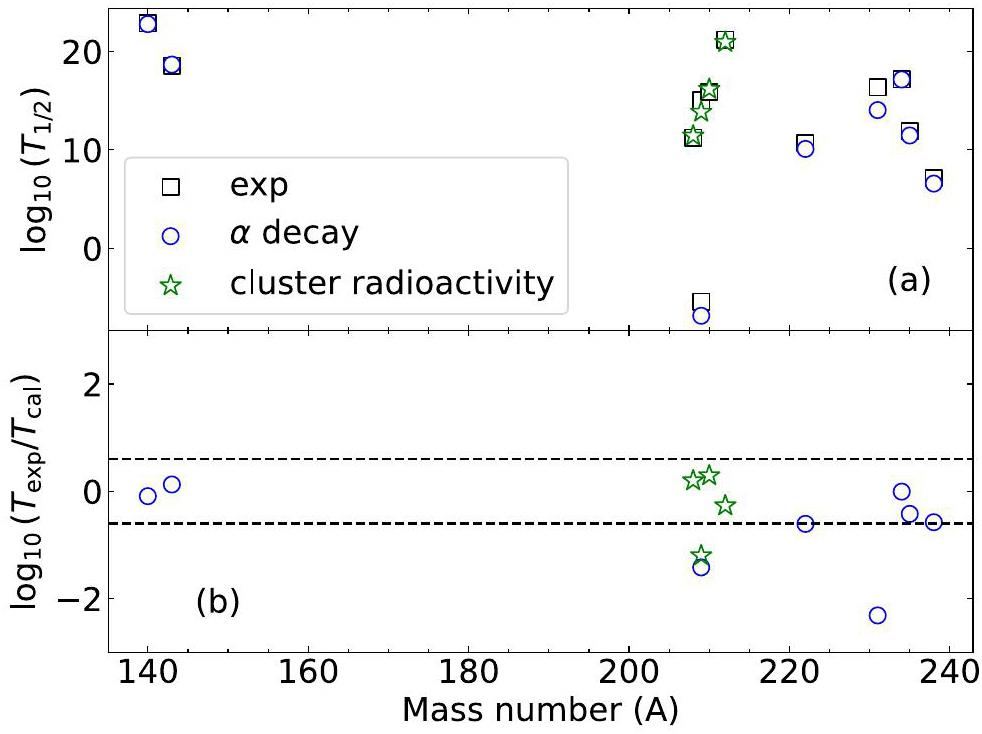

Figure 1(a) shows a comparison of the experimental and theoretical half-lives. The corresponding deviations between the logarithms of the experimental half-lives and the calculated values are shown in Fig. 1(b). The blue circles represent the calculated α decay of the ground-state parent nuclei 144Nd, 226Ra, 238U, 242Cm, 147Sm, 213Po, 235U, and 239Pu. The green stars represent the calculated 14C cluster radioactivity of the ground-state parent nuclei, 222,223,224,226Ra. It can be observed that the difference between the calculated values and experimental data is small. The values of log10(Texp/Tcal) for α decay and cluster radioactivity were generally within the range of approximately ±0.6. These values correspond to the values of the ratio Texp/Tcal within the range of approximately 0.25–3.98. This demonstrates the reliability of our model for predicting half-lives. Detailed information regarding the experimental and calculated data is presented in Table 1.

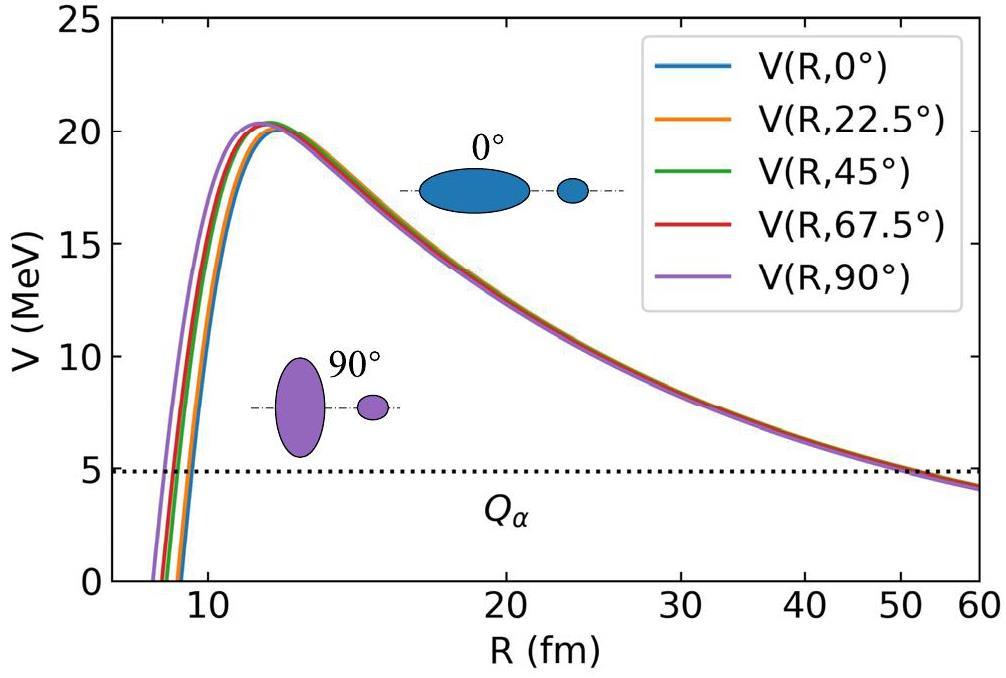

One typically assumes a spherical shape for the nuclei to simplify the calculation of α decay half-lives. However, nuclear deformation has been reported to significantly affect these calculations [50, 51]. Figure 2 shows the FHF potential of α+222Rn for selected orientations. Because the α particle is spherical, the differences in these potentials stem from the orientation of the daughter nucleus 222Rn. This shows that as the orientation rotates from the tip to the side, the Coulomb barrier increases and the nuclear part of the potential becomes shallower. This phenomenon can be attributed to the larger overlap of the nuclear density distribution in the tip orientation, which leads to a more pronounced effect on the nuclear potential. This also shows that the tunneling points differ by approximately 1 fm with varying orientations, resulting in an order-of-magnitude change in the penetration probability and subsequent alterations in α decay half-lives. In addition, the laser–nucleus interaction depends on the angle between the directions of the laser field and particle emission. It is inferred that nuclear deformation is a critical factor that should be incorporated into laser-assisted α decay and cluster radioactivity calculations.

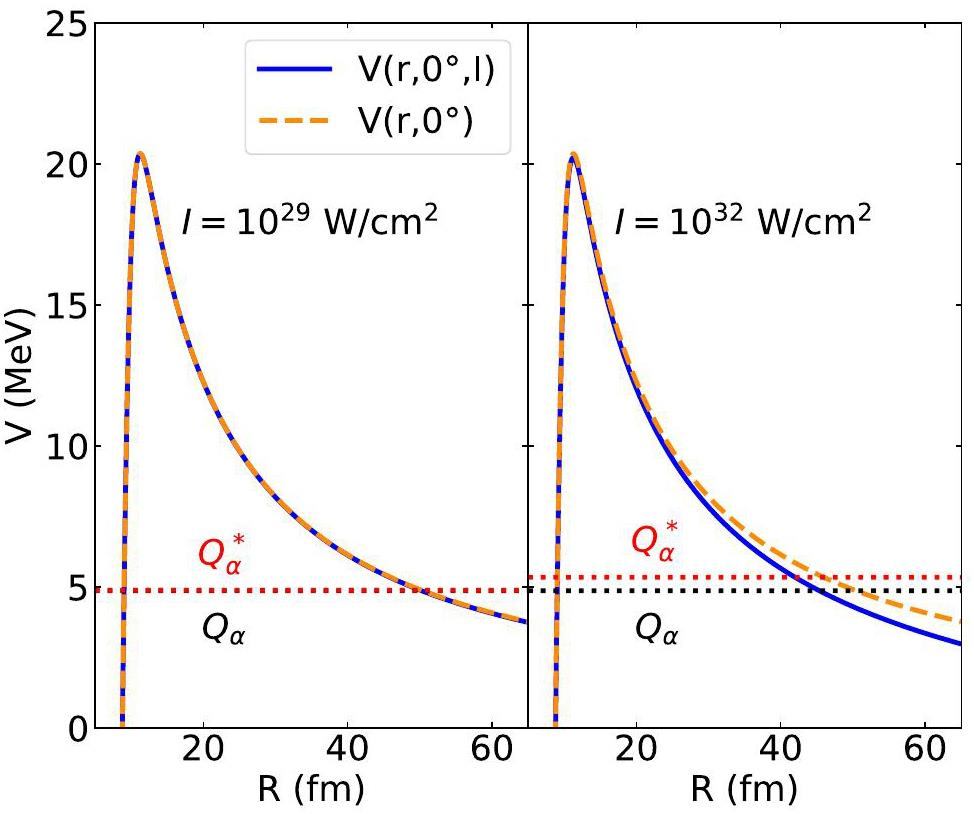

To illustrate the influence of the laser field on the penetration process, a comparison of the laser-free internuclear potentials for the α+222Rn system with the two laser-assisted cases is shown in Fig. 3. For simplicity, only the tip-orientation case is presented. The laser field induces a downward shift in the Coulomb portion of the potential and an increase in the α-decay energy, whereas its impact on the nuclear portion remains negligible. This is not surprising, because the intense laser field of intensity 1032 W/cm2 (1029 W/cm2) is comparable to the Coulomb field strength from the daughter nucleus 222Rn at a distance of approximately 66 fm (371 fm). The Coulomb component is defeated by the nuclear component within the core. Therefore, the laser field alters the tunneling points by deforming the long-range Coulomb part of the potential and changing the energy of the emitted particles, thereby affecting the penetration probability.

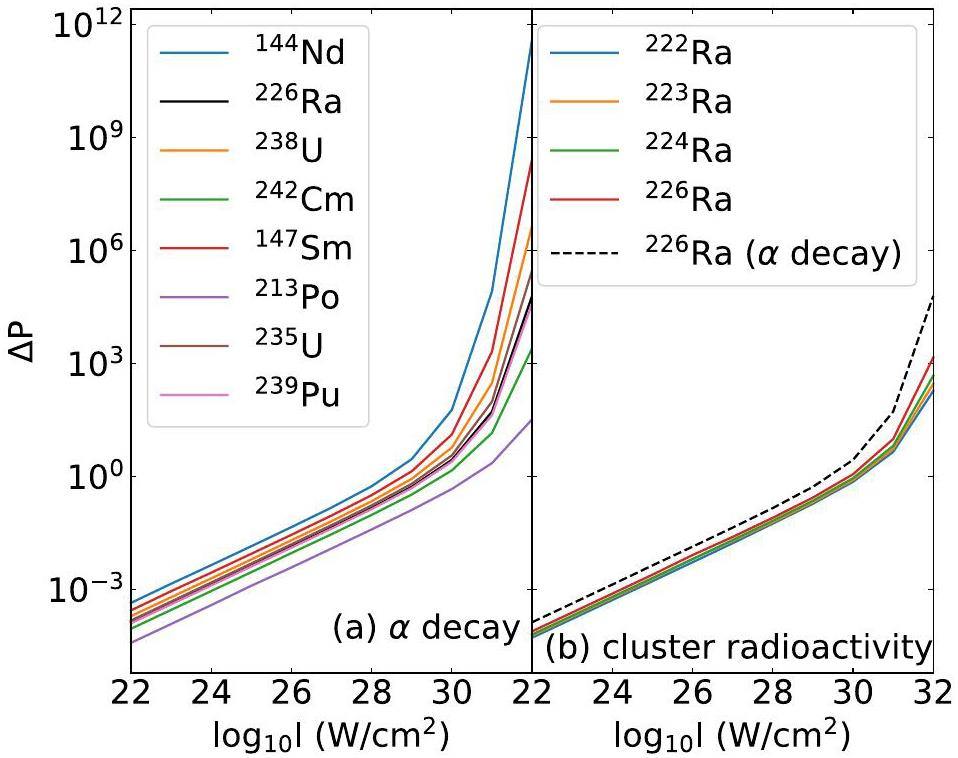

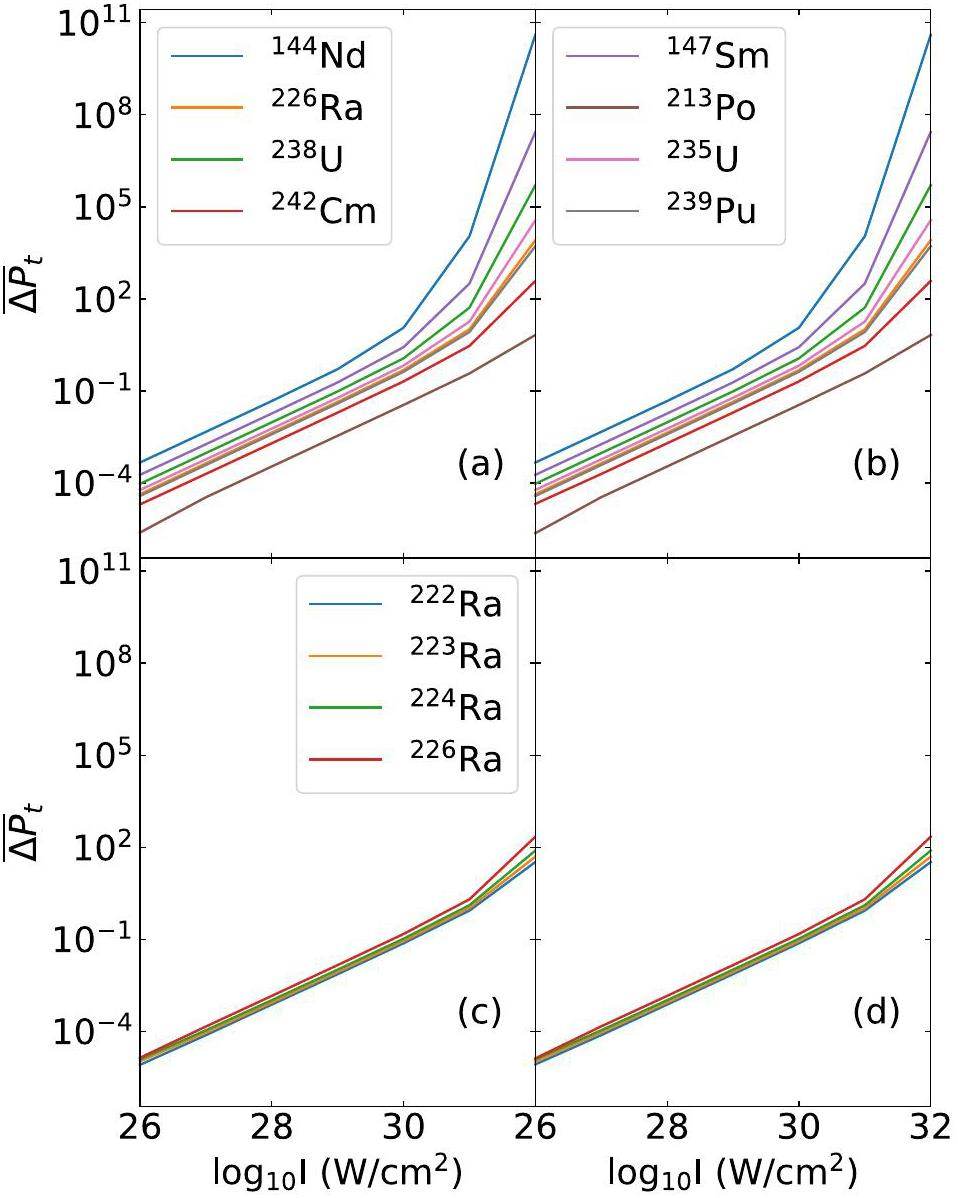

As shown in Fig. 3, the modification by the laser field becomes observable only when the intensity reaches 1032 W/cm2. Given the current laser technology, no significant modifications in the half-lives were observed experimentally. Nevertheless, even subtle alterations in the potential or decay energy may give rise to discernible effects on the decay processes because tunneling is highly sensitive to the internuclear potential. This is illustrated in Fig. 4. The relative change in the penetration probability ΔP can reach 10-3 within the accessible laser intensity. In Fig. 4, ΔP is obtained at the moment of the peak electric field strength with a fixed angle θ = 0°. ΔP and the laser intensity I are plotted on a logarithmic scale. As depicted in Fig. 4, the lower the decay energy a parent nucleus has, the greater the relative change in its penetration possibility across different nuclei. Evidently, the parent nucleus 144Nd is susceptible to laser-induced modification. This stems from its relatively low α decay energy, which results in an extended tunneling path, thereby allowing the laser field to exert a prolonged influence on the decay process. At an intensity of 1024 W/cm2, the modification of the penetration possibility is on the order of 0.1% for 144Nd, which is in agreement with Ref. [10, 12].

The laser-assisted α decay modifications for the even–even nuclei also show good agreement with the predictions in Ref. [13, 14]. The above calculations were conducted using the same approximations (dipole and quasistatic approximations) for the laser field and various internuclear potentials. Some studies [10-14] employed the phenomenological internuclear potentials, whereas this work utilized the microscopic potentials and considered nuclear deformation effects. Although the results are similar, the FHF method helps pursue a more microscopic understanding of laser-assisted α decay and cluster radioactivity in a self-consistent manner. In addition, in contrast to the modest impact of the laser field predicted by our model, several studies [15-19] have suggested a significant alteration in the alpha decay processes under current laser intensities. These calculations were obtained by solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation within the oscillating Kramers–Henneberger frame. The critical assumption was the continuity of the laser field, whereas this study was based on the premise of a single laser pulse. This discrepancy in laser conditions resulted in substantial differences in the respective predictions. However, high-intensity continuous laser fields are unattainable. The potential for future technological advancements in continuous laser technology presents an intriguing area for exploration with the promise of inducing more pronounced modifications in α decay processes.

A comparison of ΔP between α decay and cluster radioactivity for the same parent nucleus, 226Ra, was made. As shown in Fig. 4(b), ΔP for α decay is larger than that for cluster radioactivity of any parent nucleus shown here. This can be illustrated by the sensitivity of tunneling to changes in potential and decay energy. It is known that the α (14C cluster) decay energies used here are approximately 5 MeV (30 MeV) and that the tunneling exit points for α (14C cluster) are approximately 60 fm (25 fm). This implies that the modifications of the laser field in the potential and decay energy for α decay have a larger impact on the decay processes and, subsequently, a higher relative change in the penetration possibility. In addition, ΔP exhibits linear dependence on the laser intensity, whereas the values of the slope change dramatically after 1030 W/cm2. This can be explained using Eq. (22) and Eq. (23) or Eq. (24). At relatively low intensities, ΔP is proportional to

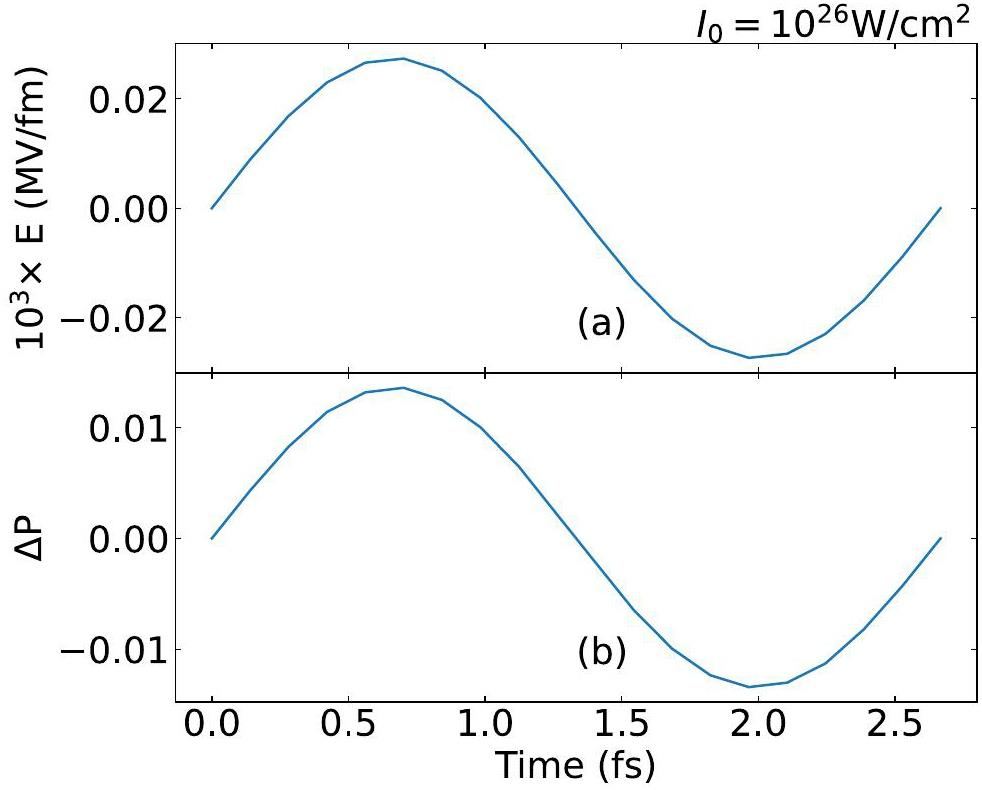

The aforementioned theoretical calculations were implemented at the peak laser electric field strength and a fixed angle θ = 0°. Figure 5 shows the linearly polarized laser electric field strength E and the relative modification of the penetration possibility ΔP at a fixed angle θ = 0° as a function of time. It is clear that time-dependent Et and ΔP share a similar variation trend, which can be explained by Eq. (22) and Eq. (23). Theoretically, the laser promotion and suppression effects on the possibility of penetration can be observed throughout a laser pulse circle. However, the best time resolution of the experimental detector is of the order of nanoseconds, which is much larger than the current laser period (of the order of femtoseconds). This implies that we cannot observe a time-dependent alteration in ΔP, as shown in Fig. 5(b), but a time averaging result in practice. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the effect of the complete laser period on ΔP.

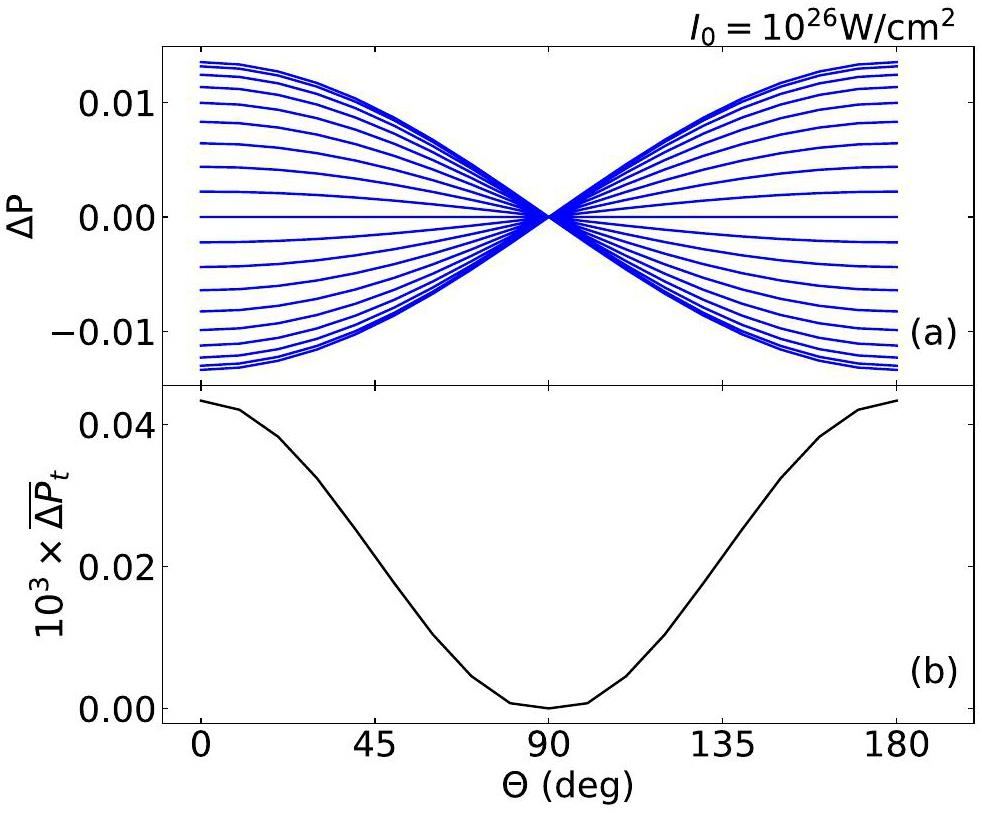

Figure 6(a) shows the correlation between ΔP and θ for a circular pulse. As illustrated in Eq. (23), ΔP exhibits a linear correlation with cosθ at some moment t. This explains the large variations in ΔP around 0 and 180 and the lack of modification along 90. Along one fixed angle, ΔP appears quite symmetric to be canceled by integrating over time. Thus, no net gain would remain for modification. Figure 6(b) shows the time-integrated modification

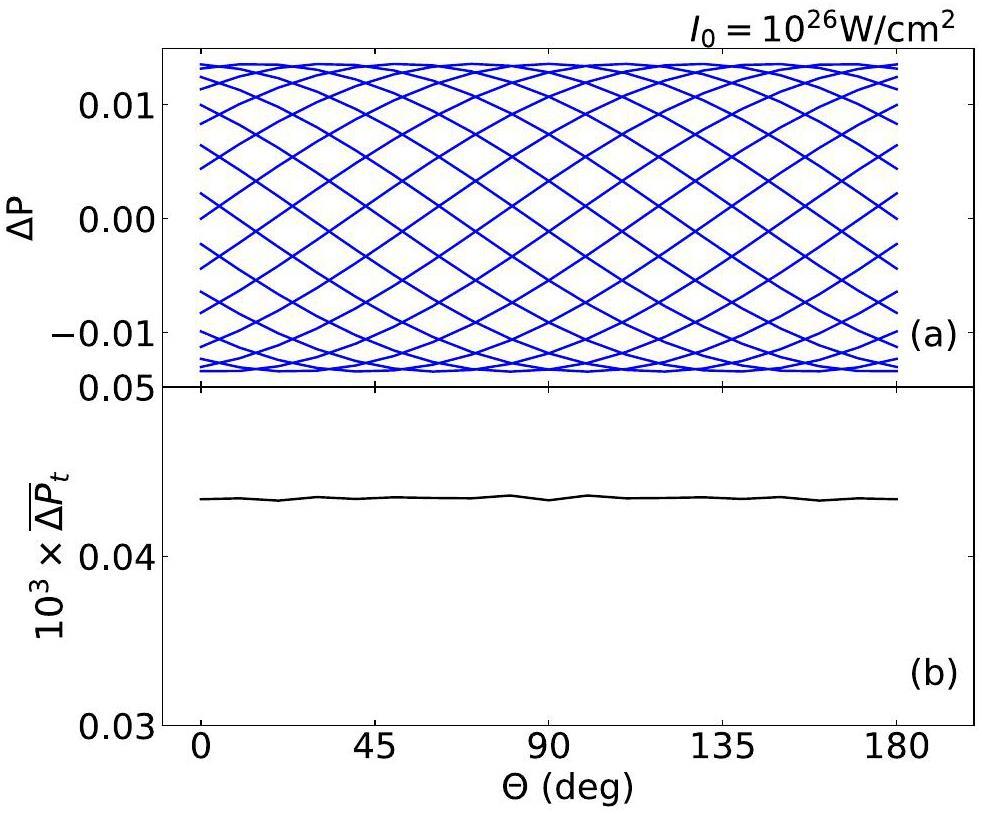

Some studies [59, 60] have explored the potential of elliptically polarized lasers to harness more information from strong-field atomic physics. Circular polarization, a specific manifestation of elliptical polarization, was considered. Figure 7(a) shows the correlation between ΔP and θ for a pulse circle with circular polarization. Unlike in the linearly polarized case, ΔP in the circular polarization arises from the superposition of sinθ and cosθ, leading to uniformly distributed modifications across all angles. The time-integrated results are presented in Fig. 7(b). It can be observed that the time-integrated modification

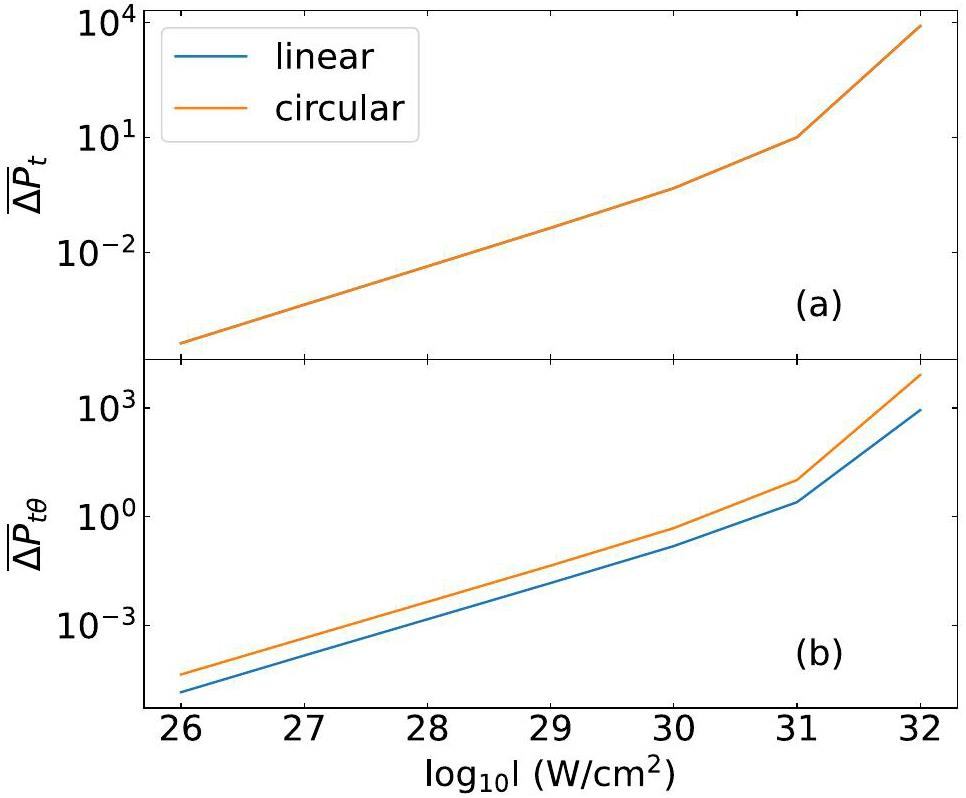

As was shown in Fig. 6, the linearly polarized laser results in angular anisotropy, with the most significant modifications along 0 and 180. A comparison of the time-integrated modification

Figure 9 displays the time-integrated modification

| Decay channel | Log10I | |

|---|---|---|

| 144Nd → 140Ce+α | 27 | 4.66×10-3 |

| 226Ra → 222Rn+α | 28 | 4.39×10-3 |

| 238U → 234Th+α | 28 | 9.51×10-3 |

| 242Cm → 238Pu+α | 28 | 1.97×10-3 |

| 147Sm → 143Nd+α | 27 | 1.84×10-3 |

| 213Po → 209Pb+α | 29 | 3.48×10-3 |

| 235U → 231Th+α | 28 | 5.92×10-3 |

| 239Pu → 235U+α | 28 | 3.89×10-3 |

| 222Ra → 208Pb+14C | 29 | 7.28×10-3 |

| 223Ra → 209Pb+14C | 29 | 8.58×10-3 |

| 224Ra → 210Pb+14C | 28 | 1.03×10-3 |

| 226Ra → 212Pb+14C | 28 | 1.43×10-3 |

Conclusion

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive microscopic analysis of the effects of extreme laser fields on α decay and cluster radioactivity. Our primary objective was to quantitatively assess the influence of intense laser fields, accounting for their temporal and angular effects, as well as variations in spatial structure. The theoretical framework is based on the Gamow model of quantum mechanical tunneling, whereas the FHF method provides a self-consistent description of the internuclear potential and nuclear deformation effects. The laser–nucleus interaction is represented by an electric field under the dipole approximation.

Our findings indicated that the laser field induced a downward shift in the Coulomb component of the potential and an increase in the decay energy. Given the high sensitivity of quantum tunneling to internuclear potential changes, even minor alterations in the potential or decay energy significantly affect the penetration probability. At an intensity of 1024 W/cm2, the modification in the penetration probability for the relevant nuclei reached approximately 0.1%, which is consistent with the results reported in Ref. [10].

The time- and angle-dependent modifications of penetration probability were analyzed using both linearly and circularly polarized lasers. In the case of linearly polarized lasers, the penetration probability exhibited its maximum modification at angles of 0 and 180, with no modification at 90. Conversely, circularly polarized lasers produced uniformly distributed modifications across all angles, and the angle-integrated modification induced by circular polarization was several times greater than that produced by linear polarization at the same intensity. Nevertheless, the modifications decreased by three orders of magnitude after temporal and angular integrations.

Finally, we compared the time- and angle-integrated modification of the penetration probability induced by circularly polarized lasers for both α decay and 14C cluster radioactivity across various nuclei. Among the studied nuclei, 144Nd was the most susceptible to laser-induced modifications, primarily because of its relatively low decay energy. At an intensity of 1027 W/cm2, the modification of

In conclusion, achieving observable laser-assisted α decay and 14C cluster radioactivity requires future advancements in laser technology to significantly enhance the intensity and experimental resolution. Consequently, expectations regarding the feasibility of laser-induced mechanisms for recycling nuclear radioactive waste should be carefully calibrated considering these technological constraints.

Time-dependent density functional theory

. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 55, 427-455 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/b11767107339 J high-energy Ti: sapphire chirped-pulse amplifier for 10 PW laser facility

. Optics letters 43, 5681-5684 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.43.005681High-contrast front end based on cascaded XPWG and femtosecond OPA for 10-PW-level Ti: sapphire laser

. Optics express 26, 2625-2633 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.26.002625Laser-assisted proton radioactivity of spherical and deformed nuclei

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 46,Current status and highlights of the ELI-NP research program

. Matter Radiat. at Extremes 5,New horizons for extreme light physics with mega-science project XCELS

. Eur. Phys. J. Special Topics 223, 1105-1112 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2014-02161-7Nuclear recollisions in laser-assisted α decay

. Phys. Lett. B 723, 401-405 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.05.025α decay in intense laser fields: Calculations using realistic nuclear potentials

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Can extreme electromagnetic fields accelerate the α decay of nuclei?

Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Nuclear fission in intense laser fields

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Determinants in laser-assisted deformed α decay

. Phys. Lett. B 848,α decay in extreme laser fields within a deformed Gamow-like model

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01371-yα-decay in ultra-intense laser fields

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 40,Geiger-nuttall law for nuclei in strong electromagnetic fields

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119,Three dimensional α-tunneling in intense laser fields

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 45,Charged particle emissions in high-frequency alternative electric fields

. Nucl. Phys. A 976, 23-32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2018.05.004Coupled-channels analysis of the α decay in strong electromagnetic fields

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Systematic study of laser-assisted proton radioactivity from deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Dynamically assisted nuclear fusion

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Enhanced deuterium-tritium fusion cross sections in the presence of strong electromagnetic fields

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Deuterium-tritium fusion process in strong laser fields: Semiclassical simulation

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Laser-nucleus reactions: Population of states far above yrast and far from stability

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112,A laser excitation scheme for 229mTh

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119,Exciting the isomeric 229Th nuclear state via laser-driven electron recollision

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Signatures of the z=82 shell closure in α-decay process

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Synthesis of a new element with atomic number z=117

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,Description of structure and properties of superheavy nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 58, 292-349 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2006.05.001α-clustering in atomic nuclei from first principles with statistical learning and the hoyle state character

. Nat. Commun. 13, 2234 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29582-0How atomic nuclei cluster

. Nature 487, 341-344 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11246Zur quantentheorie des atomkernes

. Zeitschrift für Physik 51, 204-212 (1928). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01343196Nuclear quantum many-body dynamics: From collective vibrations to heavy-ion collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 48, 152 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2012-12152-0Entrance channel potentials in the synthesis of the heaviest nuclei

. The European Physical Journal A-Hadrons and Nuclei 15, 375-388 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2002-10039-3Energy dependence of the nucleus-nucleus potential close to the coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Microscopic study of fusion reactions with a weakly bound nucleus: Effects of deformed halo

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Microscopic study of the hot-fusion reaction 48Ca+238U with the constraints from time-dependent hartree-fock theory

. Phys. Rev. C 107,How the pauli exclusion principle affects fusion of atomic nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 95,A new kind of natural radioactivity

. Nature 307, 245-247 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1038/307245a0Cluster radioactivity using various versions of nuclear proximity potentials

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Systematic study of various proximity potentials in 208Pb-daughter cluster radioactivity

. Phys. Rev. C 85,New perspective on complex cluster radioactivity of heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Unified description of α-decay and cluster radioactivity in the trans-tin region

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 39,Unified formula of half-lives for α decay and cluster radioactivity

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Nuclear clusters bound to doubly magic nuclei: The case of 212Po

. Phys. Rev. C 90,α clustering in nuclei and its impact on the nuclear symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Favored α-decays of medium mass nuclei in density-dependent cluster model

. Nucl. Phys. A 760, 303-316 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.06.011New deformed model of α-decay half-lives with a microscopic potential

. Phys. Rev. C 73,Global calculation of α-decay half-lives with a deformed density-dependent cluster model

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Half-lives and cluster preformation factors for various cluster emissions in trans-lead nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Cluster radioactivity preformation probability of trans-lead nuclei in the NpNn scheme

. Phys. Rev. C 108,The TDHF code Sky3D

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2195-2216 (2014).The TDHF code Sky3D version 1.1

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 229, 211-213 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2018.03.012The TDHF code Sky3D version 1.2

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 301,Heavy-ion collisions and fission dynamics with the time-dependent hartree-fock theory and its extensions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 103, 19-66 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2018.07.002A skyrme parametrization from subnuclear to neutron star densities part ii. nuclei far from stabilities

. Nucl. Phys. A 635, 231-256 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00180-8Attosecond ionization and tunneling delay time measurements in helium

. Science 322, 1525-1529 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1163439Angular correlation in strong-field double ionization under circular polarization

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,On gauge invariance and vacuum polarization

. Phys. Rev. 82, 664-679 (1951). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.82.664The authors declare that they have no competing interests.