Introduction

Lead-cooled fast reactors, which are considered highly promising Generation-IV nuclear energy systems, have garnered significant attention from the international nuclear energy community[1-3]. A lead-cooled fast reactor steam generator rupture (SGTR) accident can lead to a series of complex chain reactions [4], resulting in fluctuations in core power [5]. When high-pressure subcooled water comes into direct contact with high-temperature liquid metal, intense heat and mass transference occurs. The generation of a large amount of vapor leads to pressure accumulation in the system, and bubbles may follow the coolant into the core. Furthermore, direct contact between cold and hot fluids can cause the liquid metal to lose heat and potentially solidify. Thus, the consequence assessment of SGTR accidents and research on mitigation measures are important to progress lead-cooled fast reactors toward commercial deployment [6, 7].

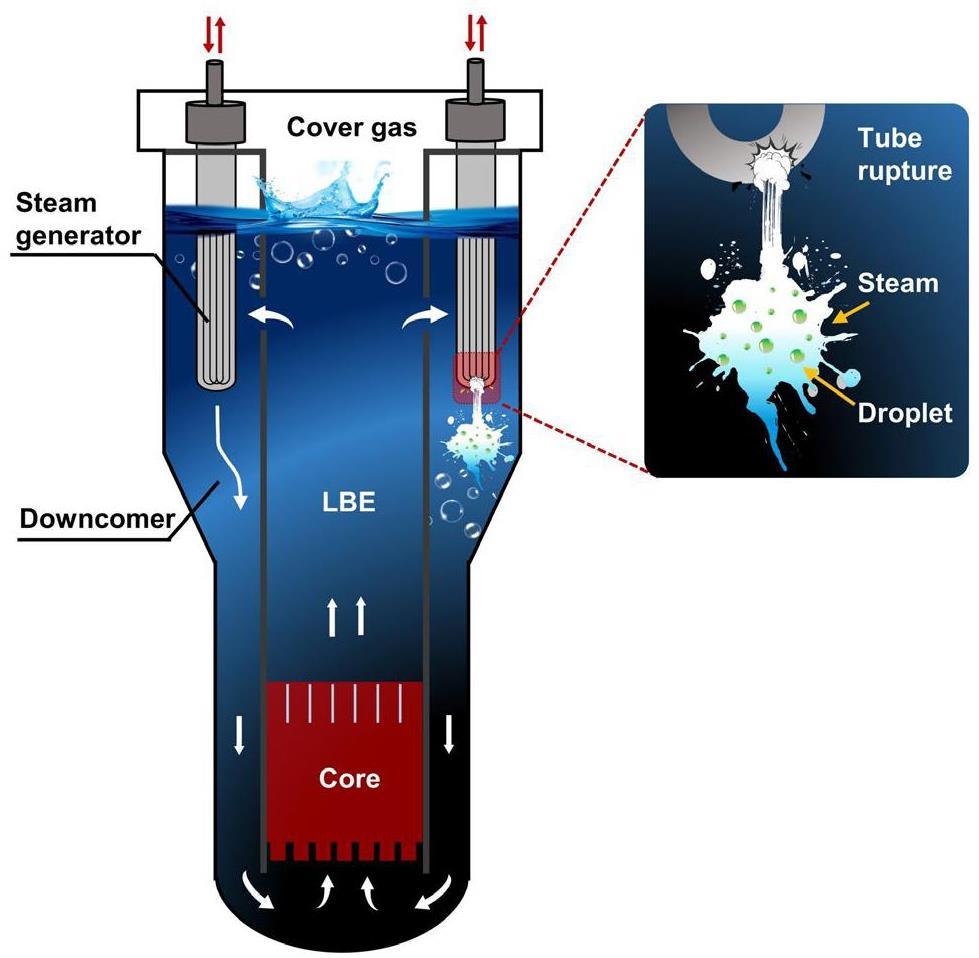

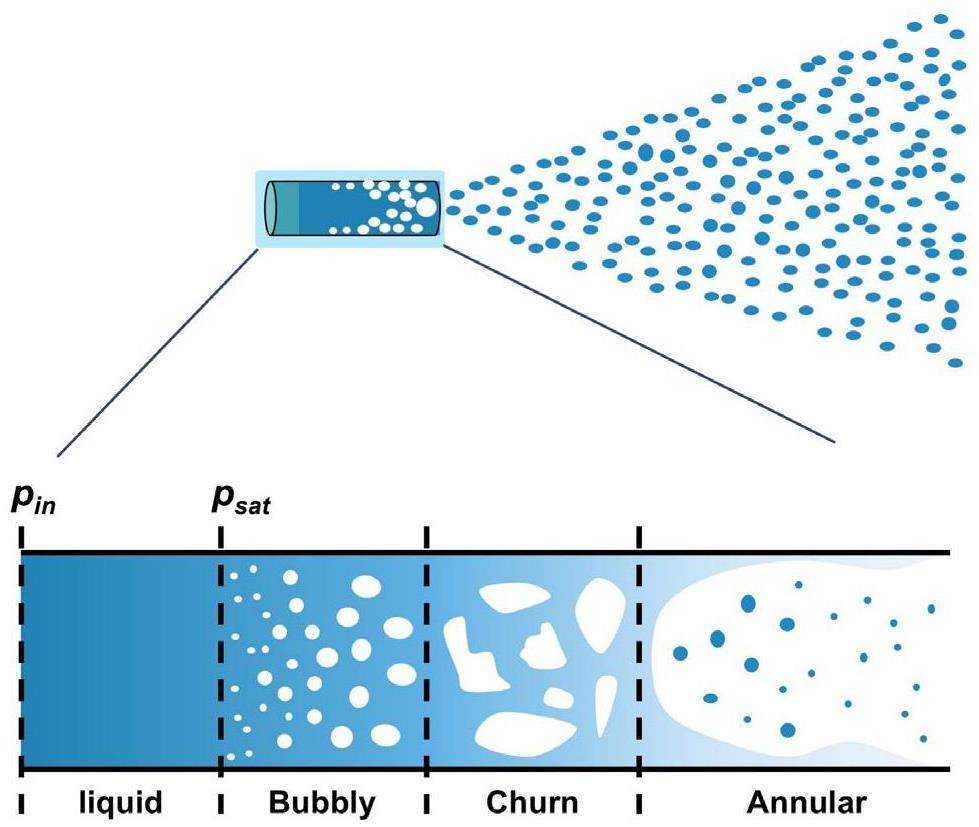

Fig. 1 shows a schematic diagram of the SGTR accident in a lead-cooled fast reactor. The accident is accompanied by strong thermodynamic and kinetic interactions between the lead–bismuth eutectic liquid metal (LBE) and the water [8], resulting in complex multiphase flow phenomena. The bubbles induced by the interactions can cause severe core power fluctuations if they enter the core [9]. The migration and evolution path of the discrete phases within the continuous phase (LBE) is a direct prerequisite for the entry of bubbles into the core.

The complexity of boiling multi-phase flows and the light-shielding properties of liquid metals pose challenges to the understanding of phase evolution due to interactions. As a result, there is less comprehension of the mechanism of phase evolution due to LBE–water interactions[10-12]. The Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (also known as the Energia Nucleare ed Energie Alternative, or ENEA) was one of the earliest international institutions to focus on this type of accident, but its main concern was the validation of SIMMER codes rather than the migration of discrete phases [13].

Moreover, some researchers have examined the metal fragmentation mechanism by observing the liquid metal droplets entering a water pool. For example, Huang et al. [14]used a high-speed camera to record the fragmentation behavior of molten LBE underwater. Similarly, Tan et al.[15] conducted an experimental study using the VTMCI facility by injecting a molten lead–bismuth amorphous alloy into water in free-fall mode. The effects of the experimental parameters, such as water temperature, LBE temperature, melt penetration rate, and water depth on the fragmentation of molten LBE were investigated. However, this experimental approach differed from the phenomenon of water jetting into liquid metal after SGTR. Subsequently, radiographic imaging techniques were developed to investigate the behavior of bubble flow[16-18]. However, lead–bismuth liquid metals, which are commonly used as radiation protection materials, have a higher capability to absorb radiation particles, leading to lower imaging resolution[19]. Ultrasound technology was initially utilized in the medical industry and other fields and was subsequently adapted to observe bubble behavior within liquid metals. Murakawa et al. [20] developed a tomography (UCT) system consisting of eight ultrasound transducers to reconstruct a three-dimensional image of a gas bubble. However, the reconstructed image did not include velocity data. Therefore, the bubble position and motion information could not be obtained. Although existing ultrasound techniques can be used to examine certain parameters (velocity and displacement) [21, 22], the capturing of the transient phase interface evolution and motion characteristics remains challenging.

Some numerical simulations for interface evolution and tracking methods have been developed to analyze multi-phase behavior [23-25]. The SIMMER code possesses a unique advantage in simulating severe accidents in metal-cooled fast reactors [26-28]. Although verified in the LIFUS5 series of experiments, the lack of a multi-phase flow structure in the code causes deviations in the numerical results from the test data. Huang et al. [29] replicated the LIFUS5/Mod2 experiments using MC3D and stated that additional experiments and physical modeling were required to improve the capability of MC3D. Yakush et al. [30] showcased the significant potential of the Volume of Fluid (VOF) method in complex multi-phase flow numerical calculations by simulating the interactions between water and molten metal in the non-boiling state. The research team plans to explore this interaction in the boiling state in future work. Ling et al. [31] combined VOF and level set methods to track moving interfaces during phase transitions. This method proved to be competitive in terms of accuracy. In summary, due to the complexity of multi-phase interactions, numerical simulation methods are still in the exploratory stage.

Therefore, discrete phase diffusion and evolution are crucial to build a complete picture of an SGTR accident and further understanding of bubble migration. However, the opacity of liquid metals and the complexity of multi-phase interactions make the phase behavior mechanism and evolution process difficult to fully understand. In this research, we conducted experiments and developed numerical simulations to examine the mechanisms underlying LBE–water interactions. Additionally, the migration and evolution behavior of discrete phases in the LBE–water interaction were reproduced based on the transient temperature data and numerical simulations inside the liquid metal.

Experimental and numerical simulation methods

Test platform and procedure

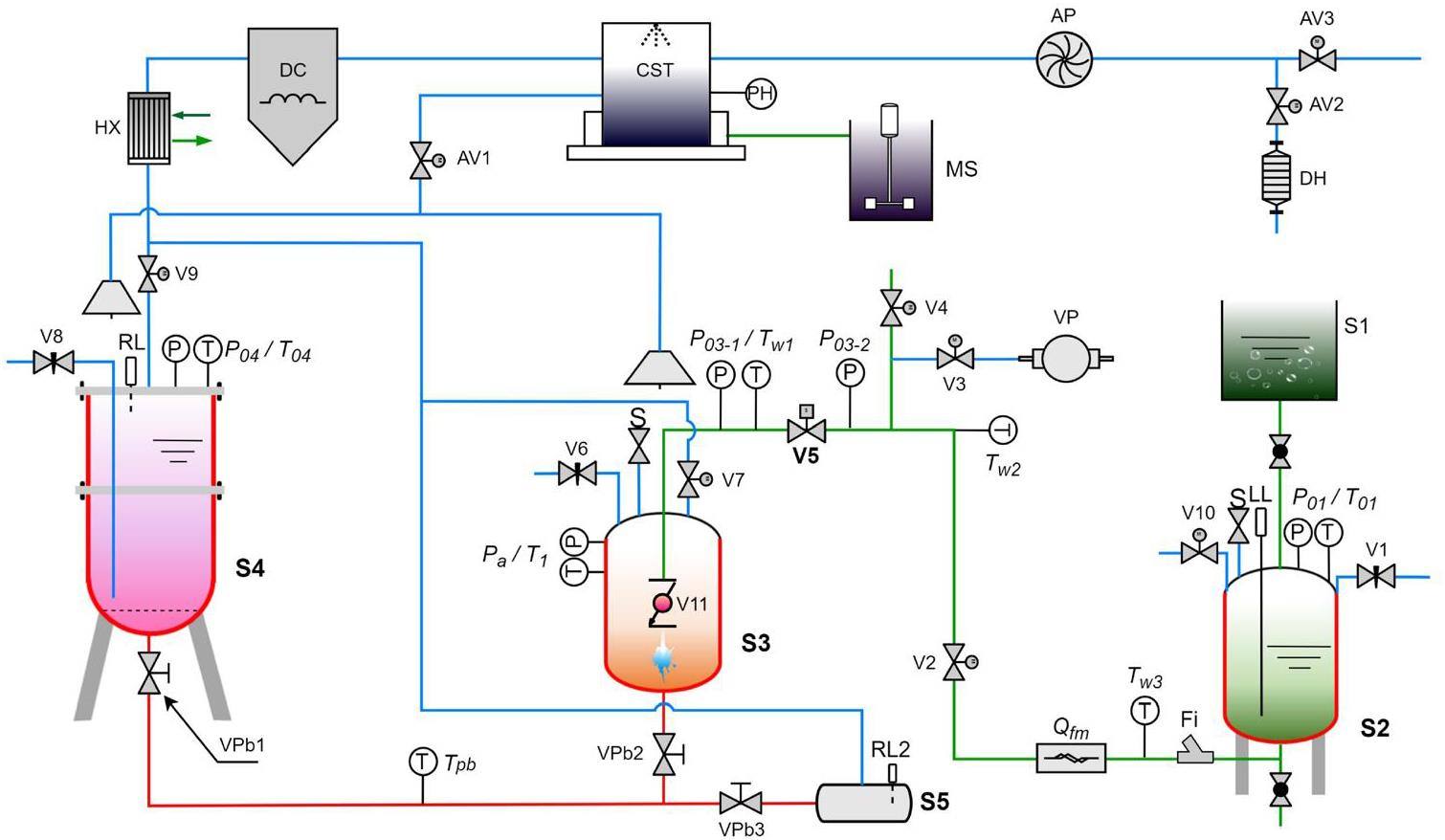

The LIJI, a test platform for LBE–water interactions designed by Shanghai Jiao Tong University, was used to study discrete phase migration and evolution. The layout of the LIJI is illustrated in Fig. 2. Detailed information about the test system can be found in a previous paper[32].

The experimental pipeline included LBE, water, and gas lines, corresponding to the red, green, and blue lines in Fig. 2, respectively. The experimental setup consisted of five subsystems: water preheating, LBE preheating, reaction and unloading, flue gas purification, and remote measurement and control. The water preheating system consisted of equipment including the deionized water tank S1, water preheating tank S2, solenoid valve V5, and high-pressure argon gas source control valve V1, with the primary purpose of controlling the preheating and pressurization of water. The LBE preheating system consisted of equipment including the argon gas source control valve V8, preheating tank S4, and lead valves Vpb1, Vpb2, and Vpb3. This system was used to melt and heat the liquid metal. The reaction and unloading system consisted of equipment including the reaction tank S3 and the recovery tank S5. This system was used to conduct experiments and recover liquid metal afterward. The flue gas purification and remote measurement systems were auxiliary subsystems. These systems were used to prevent the spread of toxic lead fumes and enable remote experimentation. These systems consisted of equipment including a heat exchanger (HX), dust collector (DC), scrubber tower (CST), fan (AP), alkali solution tank (MS), and dehumidifier (DH).

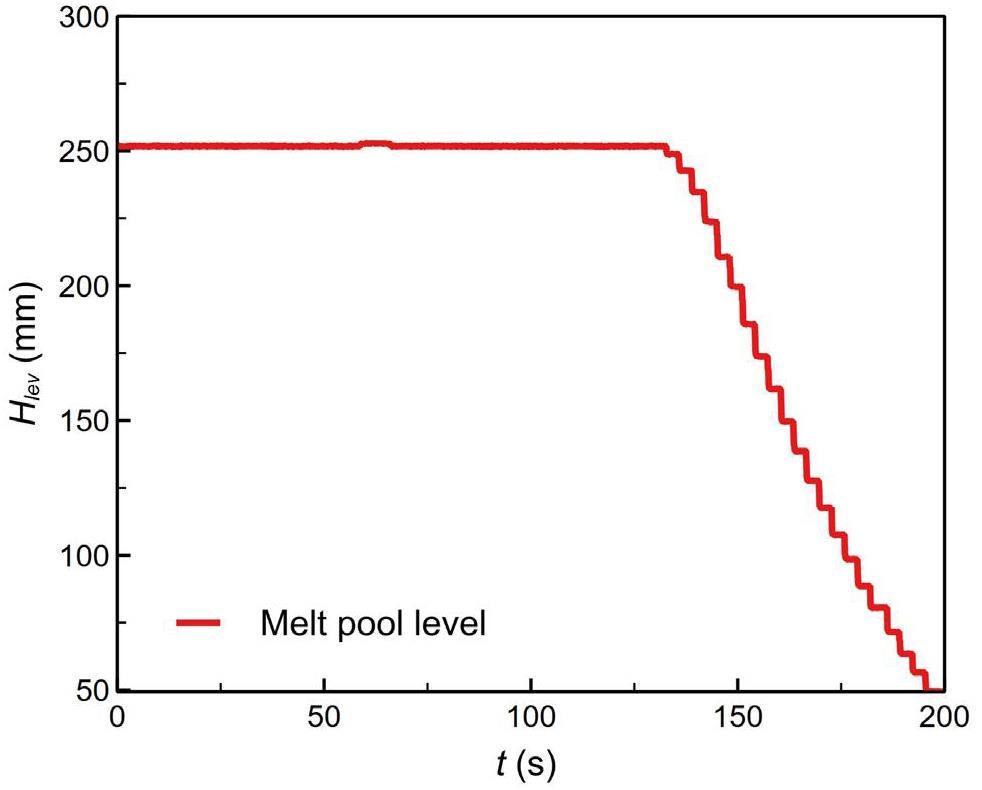

In the setup, S2 and S4 were the heating tanks for water and liquid metal, respectively, corresponding to the green and red tanks illustrated in Fig. 2. After being heated to the required temperature and pressure in S2 and S4, the water and liquid metal were introduced into the reaction tank S3 (the orange tank in Fig. 2) utilizing pressure and gravity. As shown in Fig. 3, high-precision guided wave radar (1 mm resolution, 3 mm accuracy) was used to measure the changes in the liquid level of the LBE. Since the molten lead tank was directly connected to the testing section, a drop in its liquid level corresponded to a rise in the testing section. After the experiment, all of the liquid metal in the testing body flowed into the recovery tank S5. The liquid level of the liquid metal was verified by cutting open the S5 tank. The high-speed solenoid valve V5 was installed on the jet pipeline. The jet was controlled by the opening and closing of the valve. When the parameters of the LBE in test section S3 reached the preset working conditions, the high-speed responsive solenoid valve V5 opened to precisely control the time of the water jet (with a jet flow rate error of less than 2.5% and a jet time of 0.5 s). Table 1 provides an overview of the test conditions for this study.

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Water pressure (MPa) | 0.5–2 |

| Water temperature (°C) | 84–160 |

| LBE temperature (°C) | 300–400 |

| Jet time (s) | 1–10 |

| Nozzle diameter (mm) | 10 |

Test section and measurement

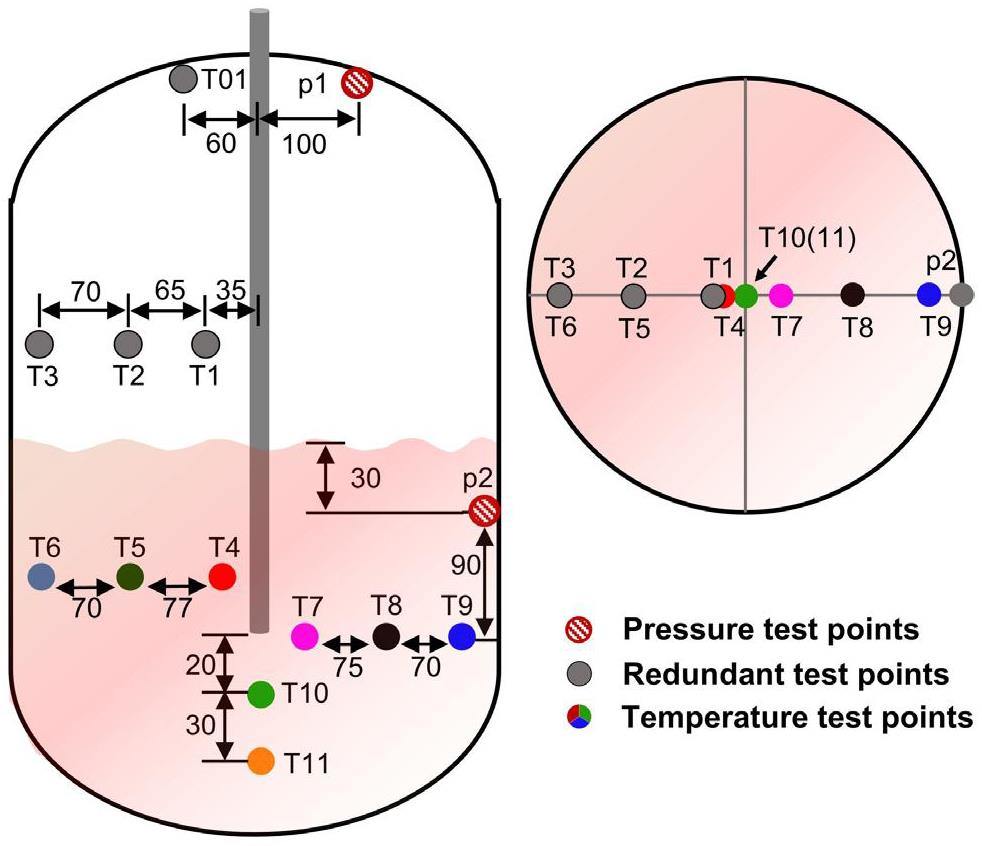

This study was primarily focused on the diffusion behavior of the vapor–water mixture within the liquid metal after high-pressure subcooled water was injected into a high-temperature liquid metal pool. A large number of bubbles were generated within the liquid metal, and these bubbles rose into the cover gas space due to buoyancy. The pressurization rate of the cover gas indicated the interaction mechanism between the liquid metal and the water. Therefore, the main test data included the cover gas pressure inside the reaction tank (p1) and the transient temperature data from measurement points within the liquid metal (T4–T11). The pressure evolution of the cover gas reflected the intensity of the phase change. The temperature transients at the measurement points indicated the vapor–water mixture’s passage, thereby aiding the mapping of its diffusion behavior. The other measurement points were auxiliary and are not included in this paper.

Figure 4 shows a schematic diagram of the test section with the distribution of the internal measurement points. Inside S3, 12 thermocouples and 2 transient pressure transducers with a high-frequency response (10 kHz) were installed. The test section’s total volume was 60 L, with the liquid metal occupying 30 L of the total volume. The nozzle diameter was 10 mm, and a high-pressure check valve was installed at the end of the nozzle to prevent the backflow of lead bismuth. The measurement errors are summarized in Table 2. The physical properties of the LBE were determined using the recommended relationships from the Pb-Bi metal Handbook [33]:

| Parameters | Error (+/-) |

|---|---|

| Temperature | 1 K |

| Pressure | 0.075% |

| liquid level in S2 | 0.5% |

| liquid level in S4/S5 | 3 mm |

| Water injection mass | <2.5% |

Numerical simulation methods

Numerical simulations of the LBE–water interactions were carried out using the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) ANSYS software program to support the experimental data and aid understanding of the phase behavior evolution characteristics and interaction mechanisms. The geometry model and the liquid metal’s physical properties are presented in Sect. 2.2. The vapor was treated as an ideal gas with the physical properties taken from the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database. The cover gas did not directly participate in the LBE–water interaction, so it was modeled as vapor to reduce the complexity of the simulation. The VOF method was employed to track the phase interface, and the User-Defined Function (UDF) program was utilized to adjust the mass and energy transfer due to the phase change. The energy transfer was calculated as the product of the mass rate induced by the phase change and the latent heat. The three main conservation equations used in the VOF model are:

The turbulence model chosen was the Realizable

It is worth noting that the Lee model is limited in its applicability to pressure-driven flash vaporization phase change mechanisms. The high-pressure, high-temperature water jet was accompanied by the depressurization flash evaporation. As shown in Fig. 5, flashing is a non-equilibrium strong transient phase change behavior. Therefore, the direct simulation of flashing in the interaction between the LBE and the high-temperature water was impractical.

The pressure-driven flashing process was converted into a multiphase mass flow inlet by calculating the mass flow rate and void fraction after flashing. The calculation process is as follows. Based on Dalton’s law of partial pressures, the principles of isentropic expansion, and the assumption of an ideal gas, the vapor-water mixture after flashing can be expressed as:

During flash evaporation, the sensitivity of the vapor temperature change to system pressure is small compared to the mass flow rate, so the effect of the temperature change rate is omitted. Therefore, Eq. 12 can be rewritten as:

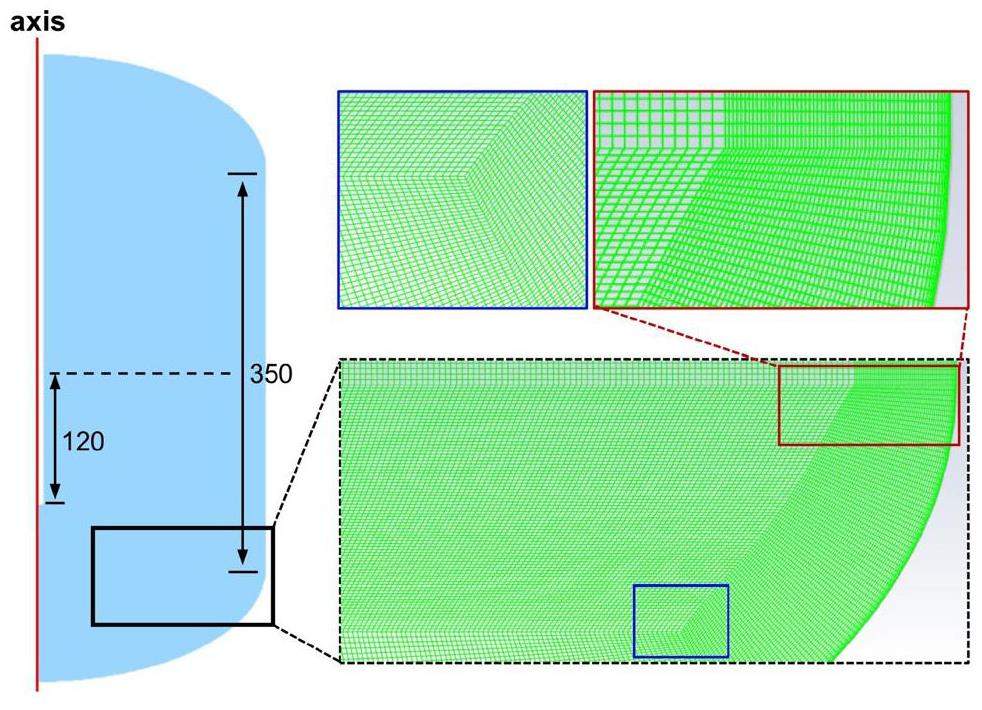

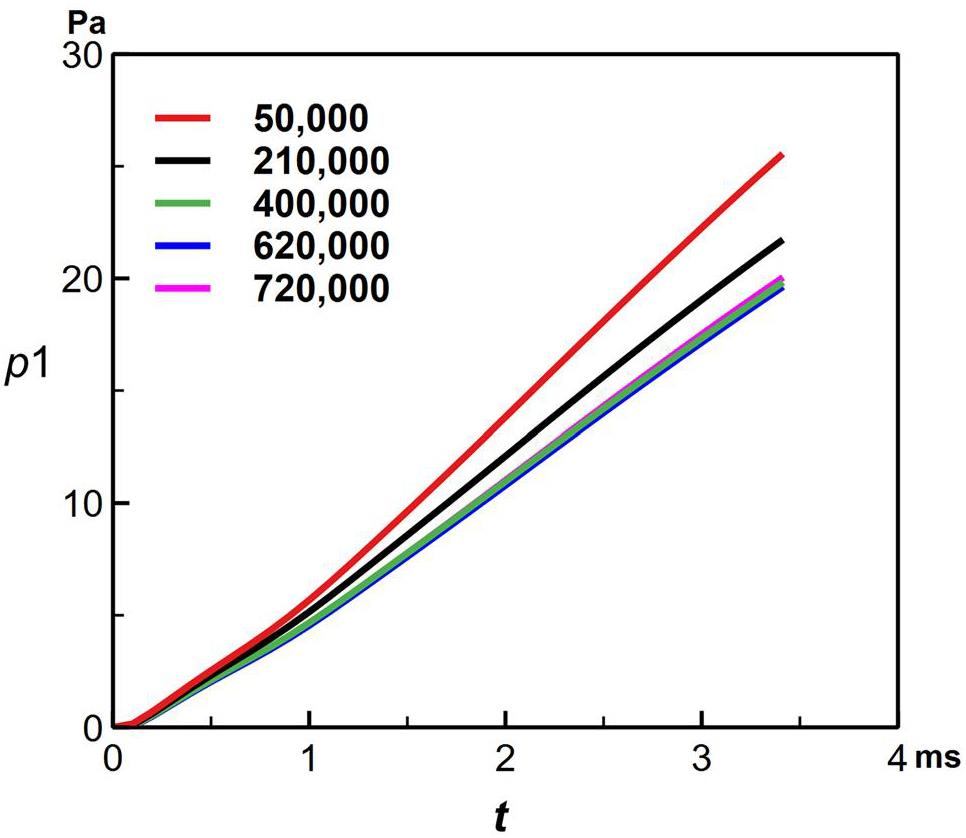

The geometry was sealed without an outlet, and the mass flux inlet condition caused repeated iterations of the total inlet pressure, making it extremely difficult for this simulation to converge numerically. Therefore, a structured grid was used to minimize numerical errors, ensuring that the grid quality ranged from 0.95 to 1.0 (Fig. 6). To reduce the influence of the number of grids on the results, 5w, 21w, 40w, 62w, and 72w grids were used to test the instantaneous pressurization of the cover gas at the jet moment. As shown in Fig. 7, 620,000 grids ensured both high accuracy and time efficiency. The Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations Consistent (SIMPLEC) algorithm decoupled the velocity-pressure relationship, and the density, momentum, and energy equations were discretized using the second-order upwind format, with the higher-order Quadratic Upwind Interpolation of the Convective Kinematics (QUICK) format for the volume fraction. The minimum time step was

Results and discussion

Physical mechanism for LBE–water interaction

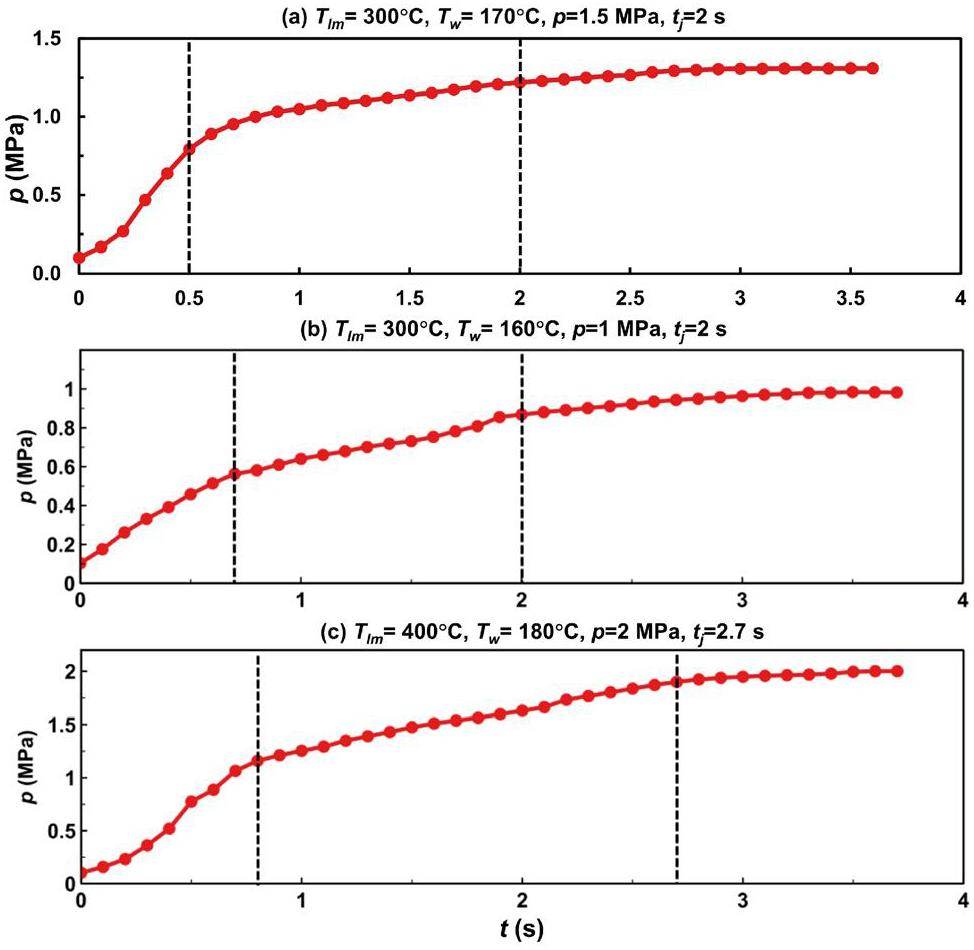

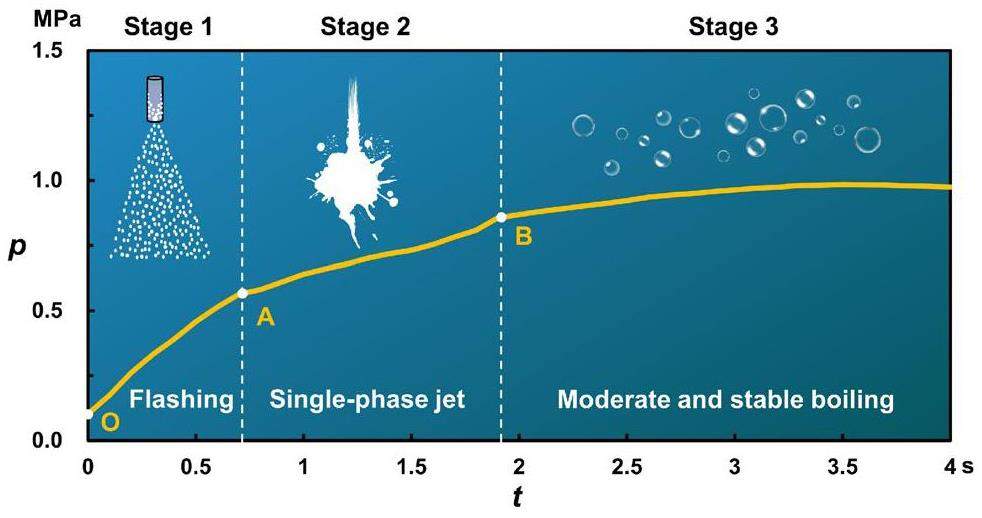

Figure 8 illustrates the pressurization during the LBE–water interaction. The data illustrated in the figure indicate that the interaction between the high-temperature lead–bismuth liquid metal and the high-pressure subcooled water occurred in three stages. The physical mechanisms of the three stages were as follows. First, the high-pressure subcooled water began to flash after the solenoid valve V5 was opened, and the resulting vapor–water mixture entered the liquid metal pool. A large amount of vapor then accumulated in the sealed reaction tank S3, causing a gradual increase in the system pressure. As a result, the vapor fraction of the flashing decreased until the pressure inside the reaction vessel was consistent with the saturation pressure of the initial water temperature, and the flashing ended. In the second stage, single-phase water entered the pool when it was driven by the pressure difference. The third stage began when the valve was manually closed or when the pressure inside the reaction vessel was equal to the initial jet pressure, at which point the flow lost its driving force. Therefore, the turning point of the first stage corresponded to the saturation pressure of the initial water temperature. For example, in cases (a), (b), and (c), the corresponding saturation pressures for the initial water temperatures were 0.789 MPa, 0.61 MPa, and 0.99 MPa, respectively. Furthermore, since the cover gas pressure did not represent the pressure near the nozzle after flashing, the turning point data were not entirely consistent, but the data were generally close.

Figure 9 provides a summary of the physical mechanisms of the three stages described above. In the first stage, the mixture with a high vapor fraction first entered the melt pool with the effect of the depressurized flash evaporation. The flashing led to the formation of a large amount of vapor, which was accompanied by a decrease in the heat transfer capacity. At this stage, the heat transfer form was primarily the boiling of liquid water surrounded by vapor in a hot environment. Consequently, the mass balance of this vapor can be expressed as:

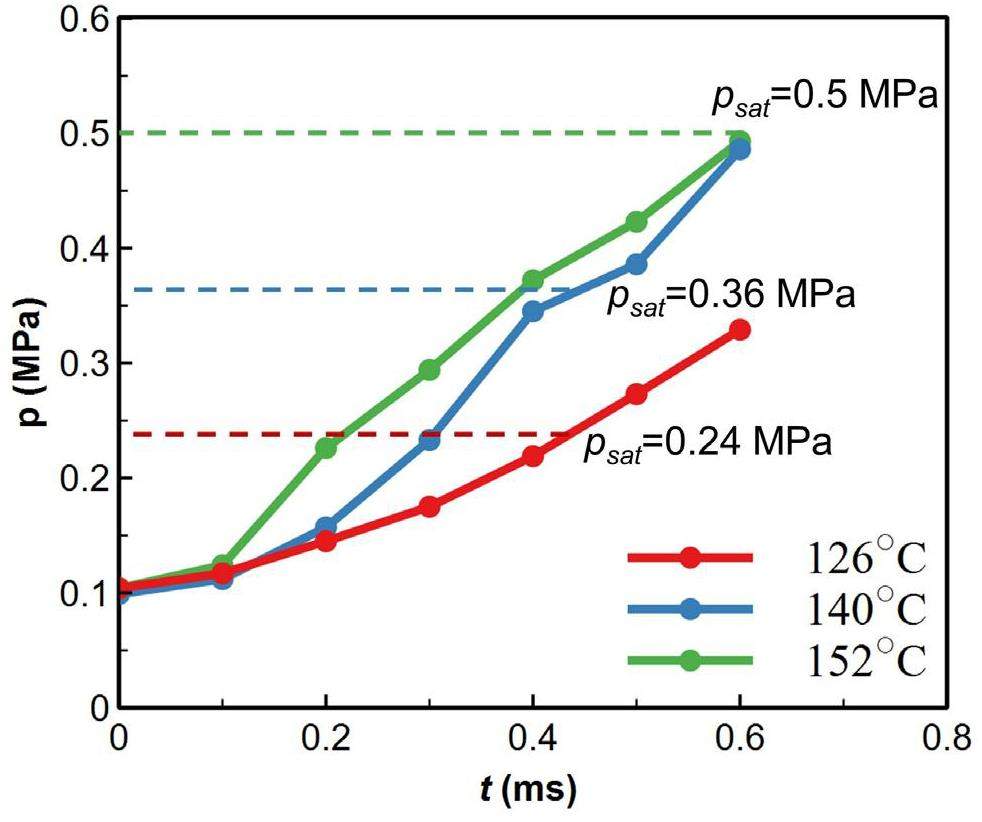

Figure 10 compares the impact of the flashing stage on the pressure increase at various water temperatures. The test data below the saturation pressure corresponding to the initial water temperature were categorized as part of the flashing stage (e.g.,

As the pressure inside the melt pool gradually increased, the vapor mass generated by flashing diminished until the internal pressure matched the saturation pressure of the initial water temperature. It then entered the second stage, known as jet impingement boiling, in which the jet was governed by the transient Bernoulli equation. Due to the direct contact between the subcooled water and the hot liquid metal, the boiling mode during this stage was unstable film boiling (transition boiling).

The third stage was marked by the cessation of flow. There were two scenarios. One scenario was valve closure due to external factors (cases a and b in Fig. 8). The second scenario was the loss of jet driving force when the internal melt pool pressure was equal to the external jet pressure. Thus, after entering the third stage, the heat transfer pattern stabilized without external interference. The residual liquid water was surrounded by the vapor and floated up inside the liquid metal, at which point the produced vapor mass was small.

Flash evaporation corresponds to the fastest phase change rate, followed by jet impingement boiling. Thus, the three phases correspond to decreasing pressurization rates in the order described, as shown in the experimental data illustrated in Fig. 8.

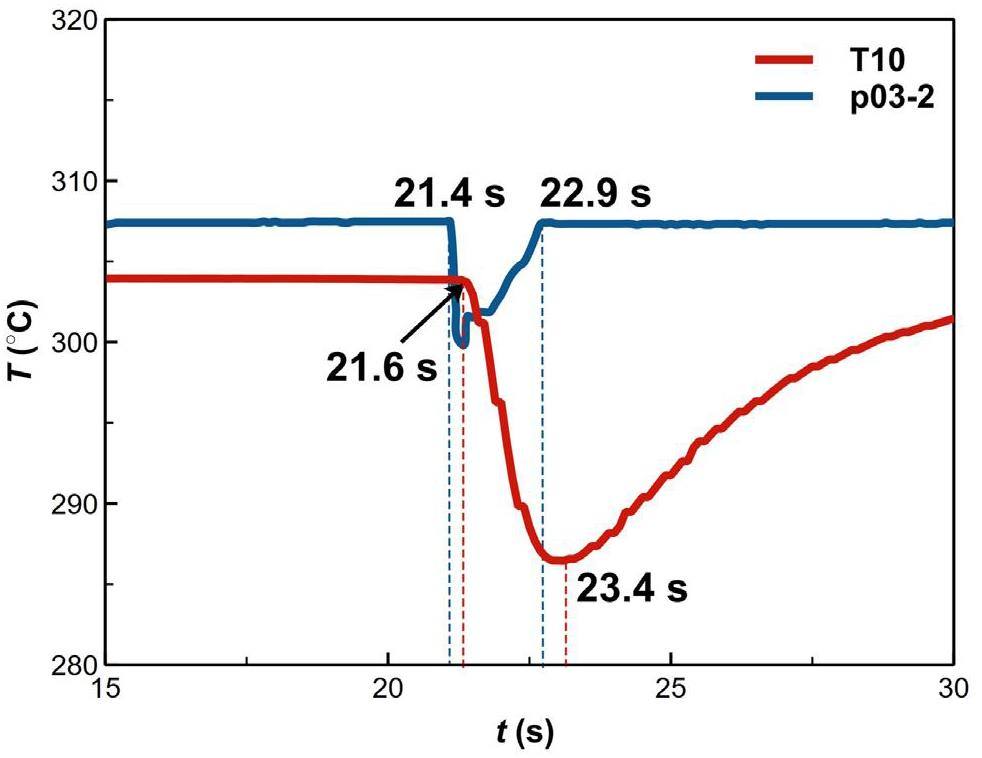

The behavior and migration of discrete phases

First, it should be clarified that sharp fluctuations in the temperature detected by the thermocouples inside the molten pool indicated that water or vapor was passing through that measurement point. Instantaneous temperature fluctuations were not indicative of the temperature of the lead–bismuth. As shown in Fig. 11, the jet pipe pressure p03-2 recovery time was taken as the actual injection time. The spray release began at 21.4 s, and T10 (the measurement point closest to the nozzle) started to plunge at 21.6 s, indicating the passage of discrete phases through the T10 measurement point. The output frequency of the pressure sensor was much higher than that of the temperature sensor. It was assumed that the moment at which the pressure sensor detected a pressure drop corresponded to the start of the jet. By comparing the turning points of the p03-2 and T10, and ignoring the time taken by the water passing from the pipe outlet to the measurement point, we could estimate that the time uncertainty of the thermocouple reflecting the discrete phases migration was less than 2.2%. Therefore, the transient behavior and migration path of vapor/water could be understood based on the temperature transient law. It is important to note that the thermocouple response method is intended for steady-state conditions as well as large temperature differences. When a thermocouple’s sensing element is in an unstable external environment, its response time becomes inadequate.

The specific assessment was grounded on the following criteria and assumptions:

(1) The transient drop in temperature profiles indicated the presence of low-temperature discrete phases passing through the test point.

(2)The sequence of temperature transients determined the migration path of the discrete phases.

(3)The jet process was assumed to be axially symmetric.

(4) Only the first drop in temperature was analyzed when the test point was in a steady state.

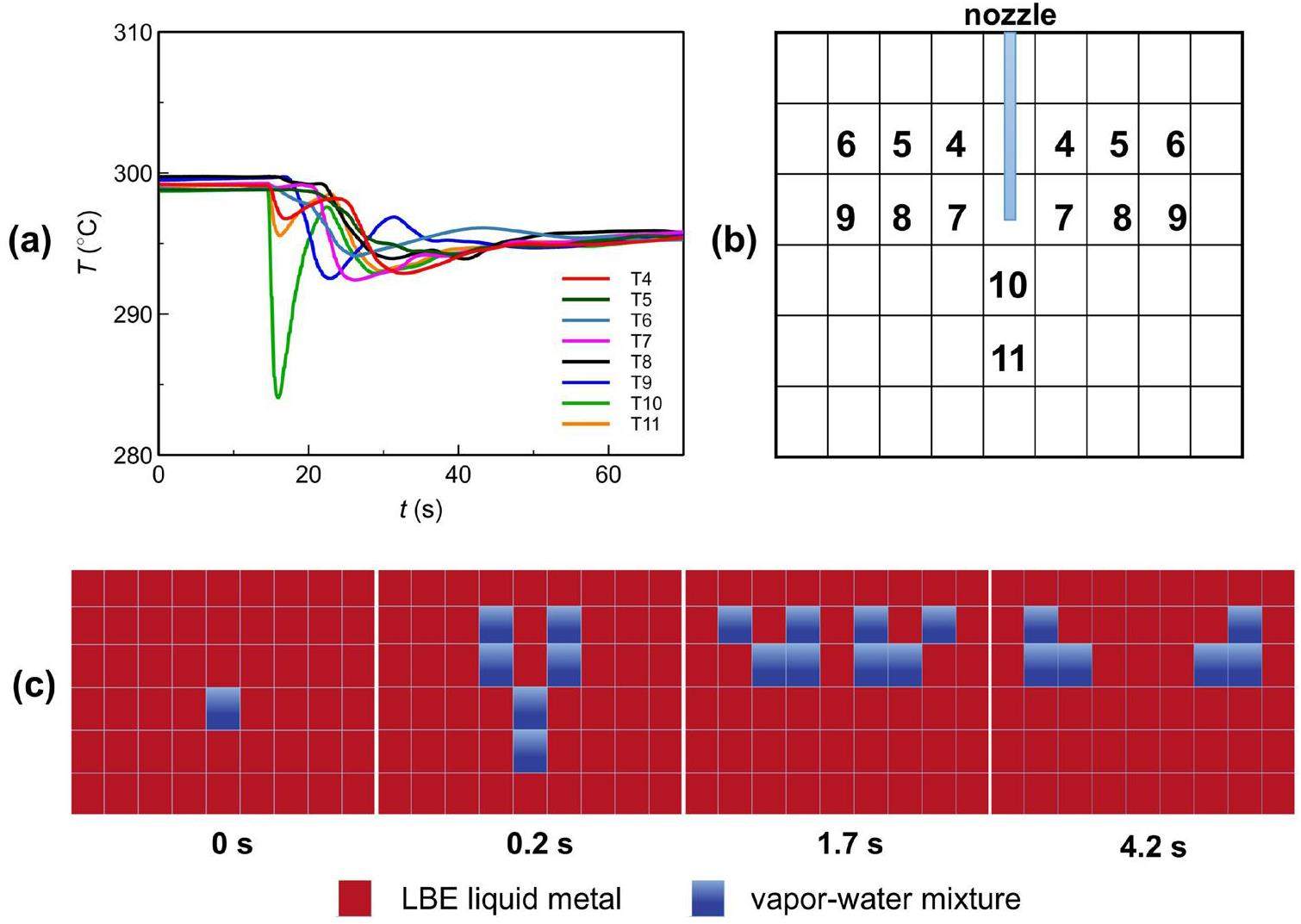

Figure 12a displays the typical temperature transient data during an LBE–water interaction. Figure 12b gives the distribution of the test points inside the liquid metal, with some of the points geometrically symmetrized. Figure 12c depicts the evolution of discrete phases at typical moments following the jet. The moment when the T10 started to fall was assumed as 0 s, and the subsequent phase evolution pictures are both based on this criterion.

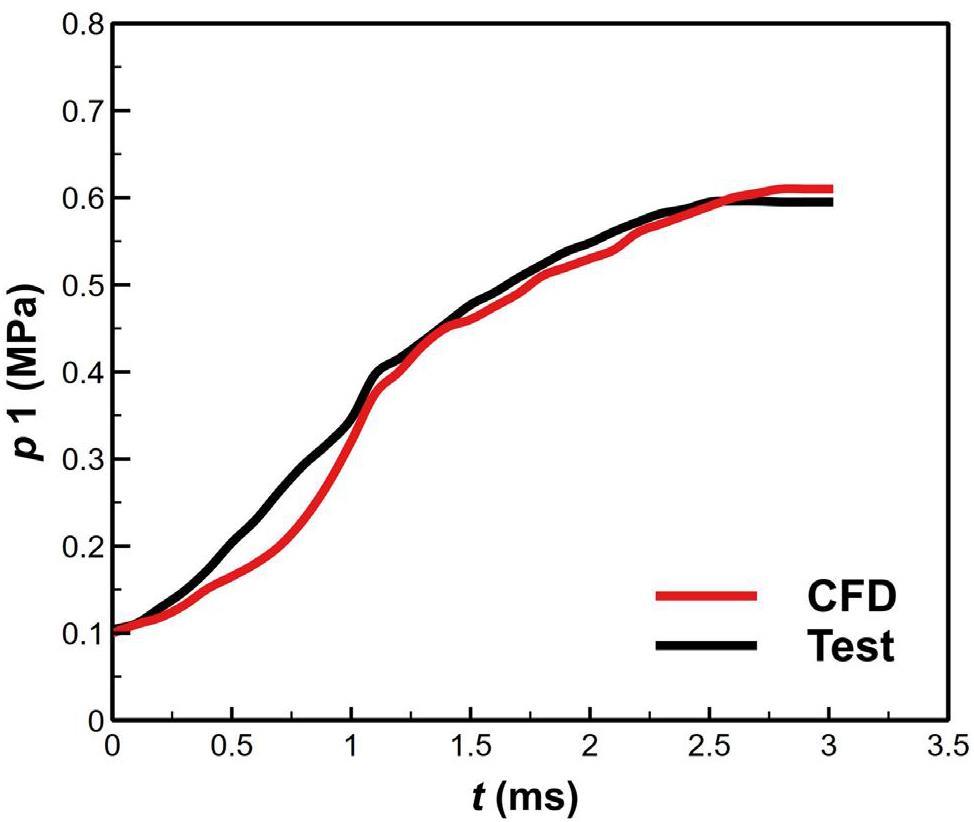

Figure 13 presents a comparison of the pressure at the p2 point obtained from the CFD with the test data. The data in the figure show that the results of the numerical simulation were in good agreement with the test data. The deviation was mainly observed in the flashing stage. This deviation resulted from neglecting the mass transfer of temperature-driven boiling during the flashing and from the bias in the calculation of flashing mass.

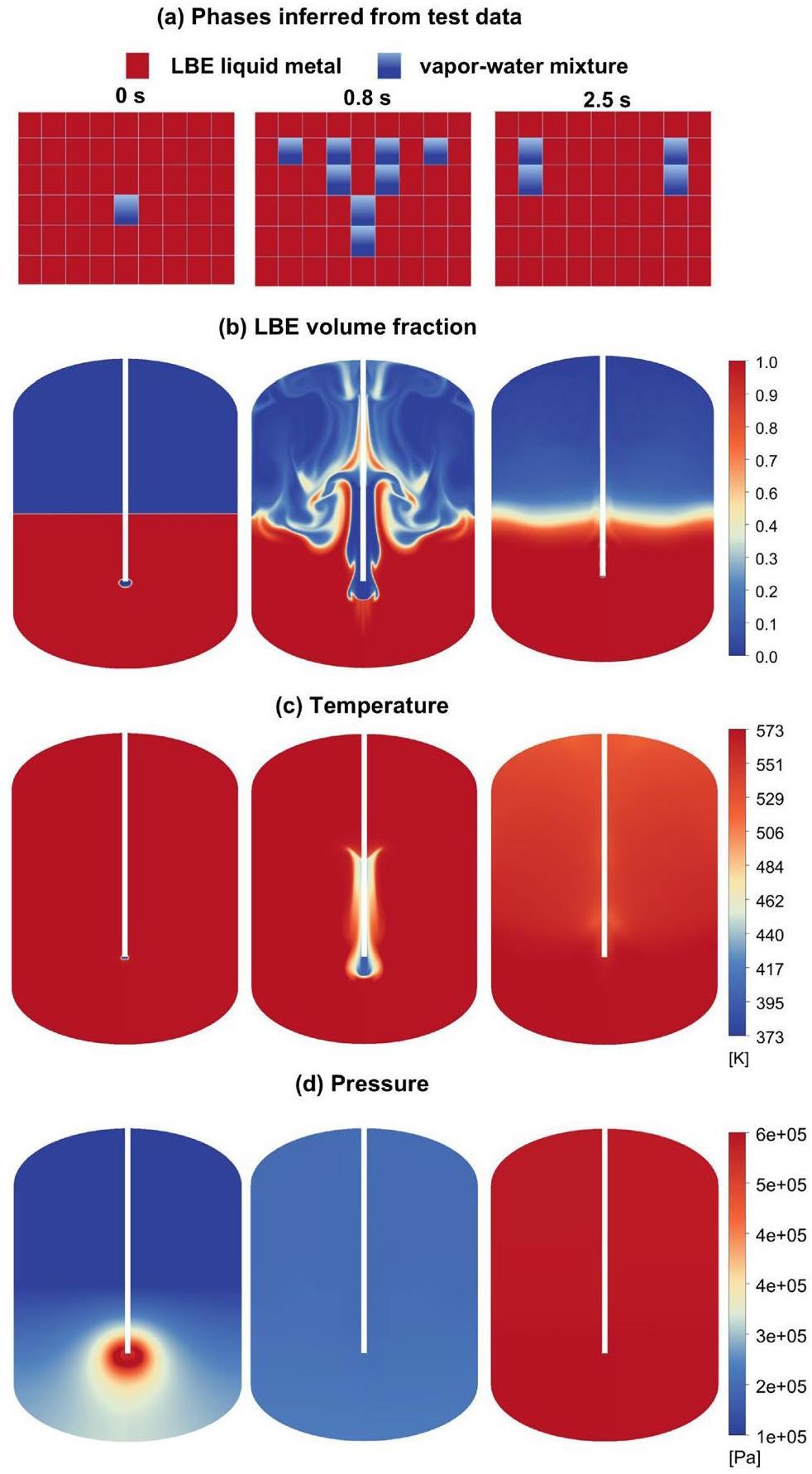

Figure 14 shows a comparison of the test and CFD regarding the discrete phase behavior. The figure also illustrates the temperature and pressure variations resulting from the LBE–water interaction. In the test, the moment when the probe T10 near the nozzle started to drop was defined as 0 s. The instantaneous impact of the jet on the molten pool generated pressure peaks, as shown in Fig. 14d. The continued phase change increased the pressure within the molten pool.

A large cavity region was formed in the liquid metal melt pool after approximately 0.2 s. Subsequently, the temperatures at the two test points T10 and T11 in the vertical direction rose after the jet stopped (2 s), signaling the departure of discrete phases from the region. A large amount of water boiled during the direct contact between the hot and cold fluids, and the main stream of the discrete phases started to float with the action of buoyancy. At the stable stage, numerous bubbles began to float upward and exit the LBE pool. The discrete phase was heated immediately upon injection into the molten pool, broke through the liquid surface, and entered the cover gas chamber. The temperature of the cover gas decreased slightly after mixing with the vapor generated by the phase change.

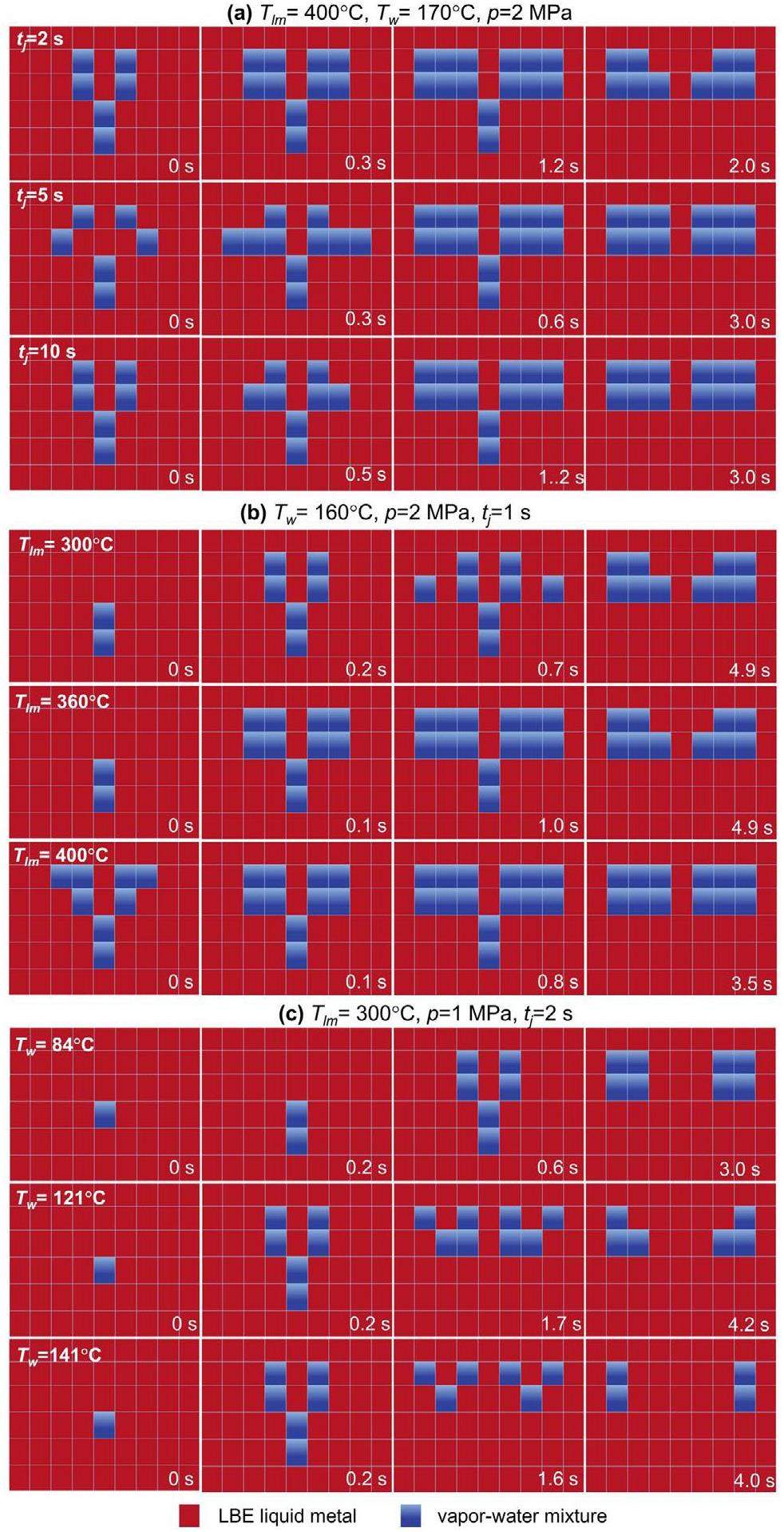

Figure 15 compares the diffusion of the discrete phases for different pressures. Because the evolutionary process varied for each condition, instead of sorting by fixed time intervals, we present key moments when the discrete phase behavior changed as typical snapshots. Figures 15b, c illustrate the fact that as the jet pressure increased, the phase evolution process accelerated noticeably and the cavities emerged earlier, a reduction from 0.2 s to 0.1 s and 0 s. In addition, according to Dinh’s theory [34], the proportion of vapor generated due to decompression boiling was correlated with the initial specific entropy of water. Consequently, increasing the jet pressure led to a higher proportion of vapor after decompression boiling. This led to larger discrete phase regions. For example, at 2 MPa, the flanking discrete phase region was substantially larger than in the other two low-pressure cases. Nonetheless, the phase evolution process remained similar, progressing through three stages: large cavity formation, flanking diffusion, and stable up-floating.

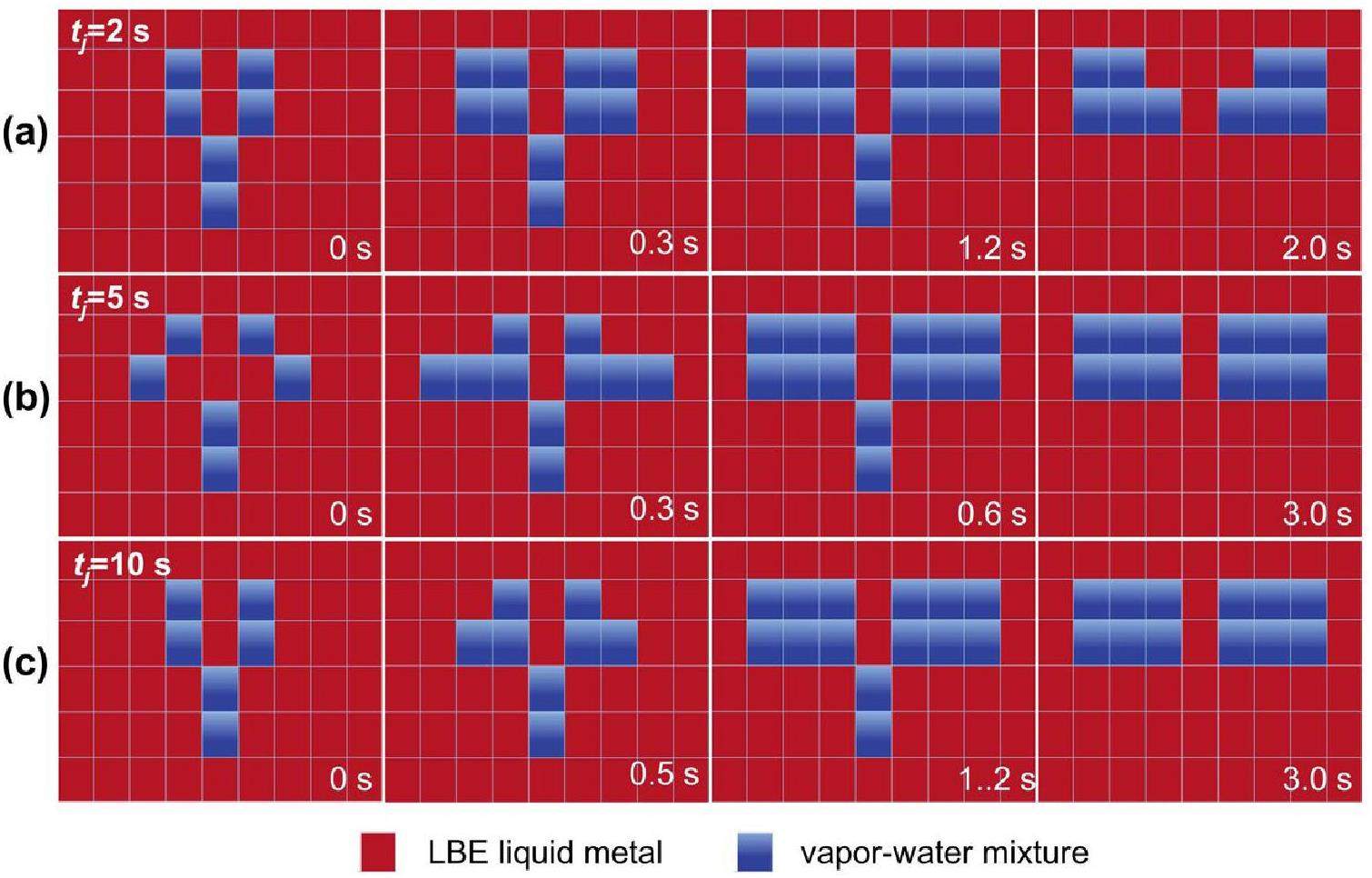

Figure 16a compares the phase evolution at various jet times. The cavity appeared at 0 s for tj=2 s, followed by the phases of flanking diffusion and steady up-floating in sequence, similar to Fig. 15. With the increasing jet time, the water entering the melt pool also increased, but the effect on the flow pattern was small. Additionally, as the jet time increased, the heat transfer between the water and the liquid metal increased. For example, the average temperature drops in the molten pool were 10.12 ℃, 11.0 ℃, and 13.2 ℃, respectively. It is worth noting that the set jet time was not equal to the actual spray time. The set jet time was determined by the open valve time of the solenoid valve V5, while the actual spray time was influenced by both the pipeline pressure and the test section pressure. This circumstance has been discussed by the authors in a previous paper [32]. Furthermore, a larger diffusion area of flanking increased the likelihood of capturing discrete phases by LBE. Figure 16b illustrates the effect of the melt pool temperature on the phase evolution. The overall evolution process was relatively similar, with the appearance of a large cavity at 0.1–0.2 s. After approximately 1 s, the jet stopped, and the flanking diffusion was generated. The rise in the melt pool temperature accelerated the temperature-driven phase transition but had minimal impact on the overall flow pattern evolution. The experimental results indicated that the temperature of the LBE liquid metal had a lesser impact on the behavior of the discrete phases. The temperature of the liquid metal could affect the boiling behavior at the microscale. When temperatures exceed the Leidenfrost temperature, bubble nucleation boiling may transition to film boiling, leading to a decrease in the heat transfer capacity. However, high-pressure water jets entering a molten pool can induce a significant churning effect, disrupting a gas film. Therefore, with the combined influence of the dual effects, the phase evolution in the temperature range of this study was less sensitive to the melt pool temperature.

The results for different water temperatures are presented in Fig. 16c. No decompression boiling occurred at 84 ℃. Consequently, cavity emergence at 0.6 seconds was significantly delayed compared to the other two decompression boiling cases (0.2 s). Water, being much denser than vapor, caused the water jets to penetrate deeper. However, the mode of phase change at this point was primarily temperature-driven boiling, so the expansion of the vapor-water mixed discrete phase was much slower.

Therefore, after the interaction between the LBE and the water, the evolution of the cavity composed of vapor–water mixture within the liquid metal mainly exhibited a V-shaped diffusion. The formation of a cavity in the liquid metal of the vapor–water mixture was a typical example of a negative buoyancy jet, for which the direction of buoyancy is opposite to the direction of jet momentum. The evolution of this type of cavity is governed by the interplay among the inertial forces, drag, gravity, and buoyancy, such that:

According to the principle of conservation of momentum, the change in the momentum of the jet is equal to the vector sum of the external forces.

Therefore, the maximum depth of the jet can be expressed as:

According to the analysis of jet penetration depth, for a low-density steam–water mixture jet impacting a high-density liquid metal, the jet will reach its maximum penetration depth because of the effect of buoyancy. This behavior contrasts with the case of a high-density jet entering a low-density medium, such as a liquid metal jet entering water, for which the jet penetrates directly to the bottom of the container.

Regarding the evolution of the cavity caused by the impact of the flashing vapor–water mixture on the liquid metal pool, the jet penetration depth was relatively small due to the density difference, and buoyancy dominated the upward and lateral diffusion of the mixture, resulting in an upper-wide and lower-narrow cavity shape resembling a V-shape. Furthermore, the larger the density difference was, the more pronounced the lateral expansion of the V-shaped cavity was. Conversely, if the liquid metal were to be jetted into water, the cavity might even take an inverted V-shape (lower-wide and upper-narrow) due to insufficient buoyancy. In summary, for the negative buoyancy jets, the V-shaped cavity was formed as a result of mechanical competition between jet inertia and buoyancy.

Conclusions

In this study, experiments and numerical simulations were combined to investigate the migration behavior of the discrete phases following the interaction between LBE liquid metal and water. Based on the temperature transient law and numerical simulation method for lead–water interaction with multi-physical processes, we inferred the evolution behavior of the vapor-water discrete phases resulting from interactions with varying thermal parameters.

High-pressure subcooled water jet lead bismuth liquid metal is a complex interaction which is dominated by three physical mechanisms. Depressurized flash evaporation provides the initial major contribution to pressurization. Once the pressure in the melt pool exceeds the saturation pressure of the initial water temperature, the flash vaporization ends, and the temperature-driven boiling begins. Finally, when the valve closes or the internal pressure matches the jet pressure, the driving force dissipates.

The discrete phases in this study exhibited a V-shaped diffusion in the molten pool after the end of the jet and then entered the stable floating stage, with small differences in the different working conditions. Furthermore, the phase evolution process was consistent, progressing through three stages: cavity formation, flanking diffusion, and stable up-floating. Longer and higher pressures markedly increased the perturbation after the interaction, leading to the more complex migration behavior of the discrete phases. The higher vapor mass fraction after decompression boiling resulted in a larger area for the diffusion of the discrete phases, in which the decompression boiling was mainly influenced by the initial water pressure and temperature. Additionally, the temperature of the LBE liquid metal and the jet time had less impact on the behavior of the discrete phases. This study provides an important reference for a deeper understanding of SGTR accidents and the validation of the numerical simulation of complex multi-physics processes in multi-phase flows.

Development and application of a multi-physics and multi-scale coupling program for lead-cooled fast reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01008-yPreliminary design of a medium-power modular lead-cooled fast reactor with the application of optimization methods

. Int. J. Energy Res. 42, 3643-3657 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/er.4112Numerical simulation of lead-bismuth alloy solidification in lead-water reaction

. Nuclear Power Eng. 43, 7-14 (2022). https://doi.org/10.13832/j.jnpe.2022.03.0007An experimental review of steam generator tube rupture accident in lead-cooled fast reactors: Thermal-hydraulic experiments classification and methods introduction

. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 160,CFD analysis of a CiADS fuel assembly during the steam generator tube rupture accident based on the LBEsteamEulerFoam

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 157 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01312-1Study on severe accident mitigation measures for the development of PWR SAMG

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 17, 245-251 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-8042(06)60046-8Analysis of steam generator tube rupture accidents for the development of mitigation strategies

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 54, 152-161 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.07.032Experimental investigation on pressure-buildup characteristics of a water lump immerged in a molten lead pool

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 35 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01188-1Coupled modeling of neutronics and thermal-hydraulics processes in LFR under SG-leakage condition

. Nucl. Energy Technol. 9, 85-92 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3897/nucet.9.99154Visualization experiment on interface fragmentation behavior of molten LBE with water

. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 49(A review of research progress in heat exchanger tube rupture accident of heavy liquid metal cooled reactors

. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 109, 1-8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2017.05.034Investigation of single bubble rising velocity in LBE by transparent liquids similarity experiments

. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 108, 204-213 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2018.05.011Experimental investigation and SIMMER-III code modelling of LBE-water interaction in LIFUS5/Mod2 facility

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 290, 119-126 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2014.11.016Experimental study on fragmentation behaviors of molten LBE and water contact interface

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 26, 120-124 (2015). https://doi.org/10.13538/j.1001-8042/nst.26.060601Experimental investigation on the characteristics of molten lead–bismuth non-eutectic alloy fragmentation in water

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 115 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01097-9Synchrotron radiation X-ray imaging of cavitation bubbles in Al–Cu alloy melt

, Ultrason. Sonochem. 21, 1275-1278 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2013.12.024Euler–Euler modeling and X-ray measurement of oscillating bubble chain in liquid metals

. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 110, 218-237 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2018.09.011Experimental study on bubble rising process in stagnant liquid metals

. Journal Cent. South Univ. (Science Technol.) 52, 294-302 (2021). https://doi.org/10.11817/j.issn.1672-7207.2021.01.030Visualization and measurement of subcooled water jet injection into high-temperature melt by using high-frame-rate neutron radiography

. Nucl. Technol. 139, 205-220 (2002). https://doi.org/10.13182/NT02-A3314.M3-D shape and velocity measurement of argon gas bubbles rising in liquid sodium by means of ultrafast X-ray CT imaging

. Flow Meas. Instrum. 95,Study on the liquid metal flow field in FC-mold of slab continuous casting

. Adv. Manuf. 3, 212-220 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.10607UDV measurements of single bubble rising in a liquid metal Galinstan with a transverse magnetic field

. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 94, 201-208 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2017.05.001Three-dimensional numerical simulation of bubble rising in viscous liquids: A conservative phase-field lattice-Boltzmann study

. Phys. Fluids. 31,Direct numerical simulation of bubble dynamics using phase-field model and lattice Boltzmann method

. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 11391-11403 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/ie303486yNumerical simulation of bubble rising behavior in liquid LBE using diffuse interface method

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 340, 219-228 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2018.09.041The development of SIMMER-III, an advanced computer program for LMFR safety analysis, and its application to sodium experiments

. Nucl. Technol. 153, 245-255 (2006). https://doi.org/10.13182/NT06-23D numerical study of LBE-cooled fuel assembly in MYRRHA using SIMMER-IV code

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 104, 42-52 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2017.02.009Implementation of the chemical PbLi/water reaction in the SIMMER code

, Fusion Eng. Des. 109, 468-473 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2016.02.080Numerical investigation on LBE-water interaction for heavy liquid metal cooled fast reactors

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 361,Numerical modeling of water jet plunging in molten heavy metal pool

. Mathematics. 12, 12 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/math12010012A sharp-interface model coupling VOSET and IBM for simulations on melting and solidification

. Comput. Fluids. 178, 113-131 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2018.08.027Experimental investigation on the interaction characteristics of lead‑bismuth liquid metal and water

. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 149,Multiphase flow phenomena of steam generator tube rupture in a lead-cooled reactor system: A scoping analysis

.Effects of gas velocity and break size on steam penetration depth using gas jet into water similarity experiments

. Prog. Nucl. Energy 98, 38 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2017.02.006Xiao-Jing Liu is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.