Introduction

Regardless of the purpose of the ring, always in the case of two modes, when multiply charged heavy particles and one or two charged light particles are accelerated, the problem arises of what the magneto-optical structure should look like to satisfy all the conditions of stable motion for both types of particles. Multiply charged particles have a prevailing heating effect due to intrabeam scattering, and light particles have a greater chance of crossing through the transition energy. All of these effects are of great importance for colliders, where luminosity plays a decisive role. When developing a lattice that meets all requirements for differently charged particles, it is fundamentally important to have a retunable structure without introducing design differences. This structure is called dual-purpose or simple, dual.

In the NICA collider the dual magneto-optical lattice opens up the prospect of accelerating both heavy ions, such as gold, and light particles like protons and deuterons. The design of this lattice requires a different approach, owing to the varying charge-to-mass ratios involved.

Light particles

In a classical regular lattice, the transition energy is approximately equal to the betatron tune,

Transition energy

In general, the transition energy is determined by the momentum compaction factor

Superperiodic modulation

The equation for the dispersion function with biperiodic variable focusing [?]

First harmonic k=1 has a dominant influence, the condition is implemented for

For structure where the missing magnet technique is used, for one reason or another it can be also implemented (Fig. 2), but the dispersion at the edge of the arc must be suppressed [7]. The transition energy for the entire ring with straight sections is achieve γtr = 15.

Heavy‑ion mode

The lifetime of the beam luminosity in a collider experiment is achieved through the reduction of intrabeam scattering effects coupled with the application of stochastic and electron beam cooling techniques. This approach is particularly important for high-intensity ion beams. The temporal evolution of the emittance and momentum spread in the presence of cooling processes is governed by the following set of equations:

Stochastic cooling

Let’s consider stochastic cooling using the approximate theory developed by D. Mohl [8, 9]. Based on the main findings, the cooling rate can be determined using the following expression:

The maximum value of the frequency band is determined by the requirement that the “Schottky” beam bands do not overlap. In the simplest case, this can be expressed as

Equation (6) is derived for the coasted beam. The particle density of a single harmonic RF resonator is described by a Gaussian distribution:

To summarize, the effective number of particles depends on their distribution and is determined by their form-factor

Based on Eq. (8), asymptotic growth may occur in two scenarios:

1. slip-factor approaches the value

2. slip-factor approaches zero, mixing between the kicker to the pickup does not occur and Mkp→∞.

The efficiency of stochastic cooling depends on the properties of the magneto-optical structure. In classical “regular” lattices, transition energy is acquired through the horizontal frequency

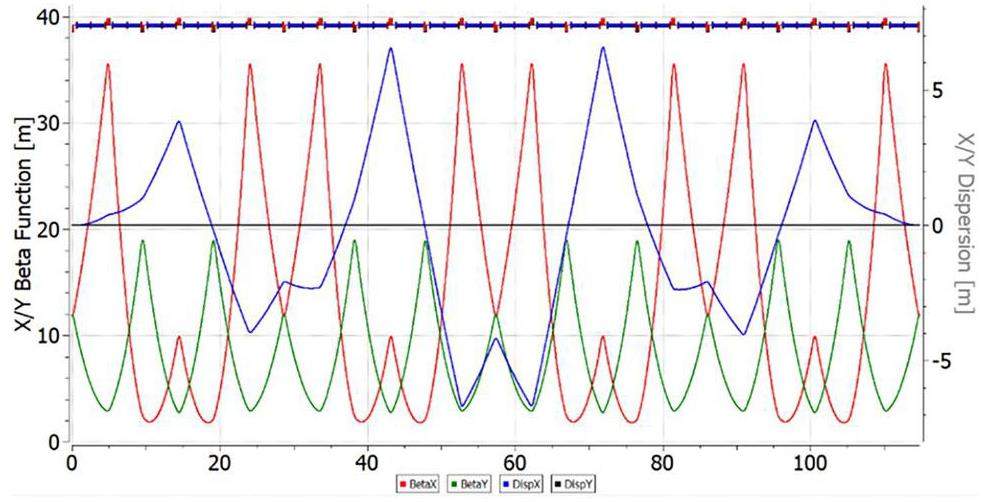

The behaviour of the β-functions and D the dispersion across the entire “regular” ring illustrates at Fig. 3 with γtr = 7. Straight sections, which remain constant in all lattices, are essential for analyzing the resonant characteristics of the entire structure. Their arrangement did not affect intrabeam scattering or transition energy. To suppress dispersion in the “regular” lattice, missing magnets technique implemented on both sides of the arc.

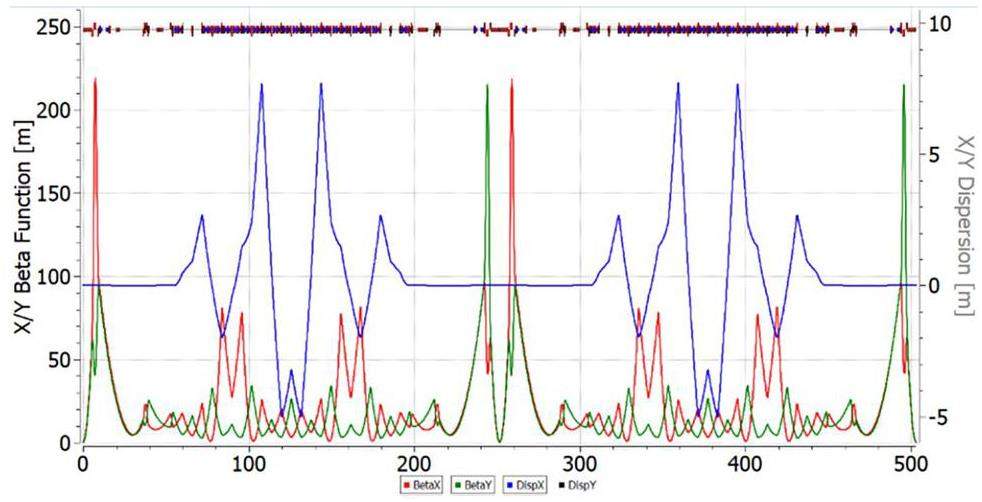

The “resonant” lattice is based on the principle of resonant modulation of the dispersion function and can be obtained from a “regular” one by introducing additional family of focusing quadrupoles. To suppress dispersion, two edge focusing quadrupoles on both sides of the arc or only two families of focusing quadrupoles on the arc can be used, when an integer number of betatron oscillations is reached.

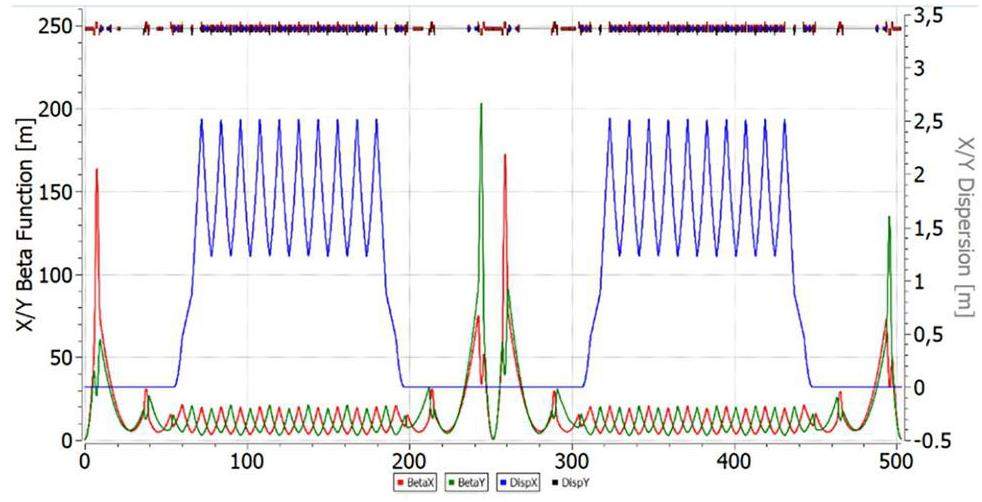

The case of a “combined” lattice, one arc operates in a regular mode, while the other employs resonant modulation (Fig. 4). This choice was based on the principle of compensation, as described by Eqs. 13 and 14, which requires a greater modulation depth of the quadrupoles than in purely “resonant” lattice with increased transition energy.

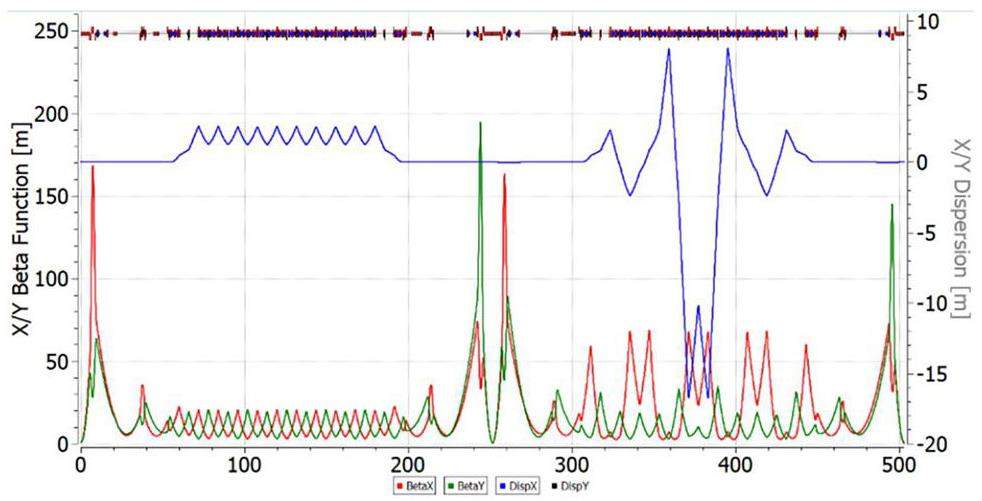

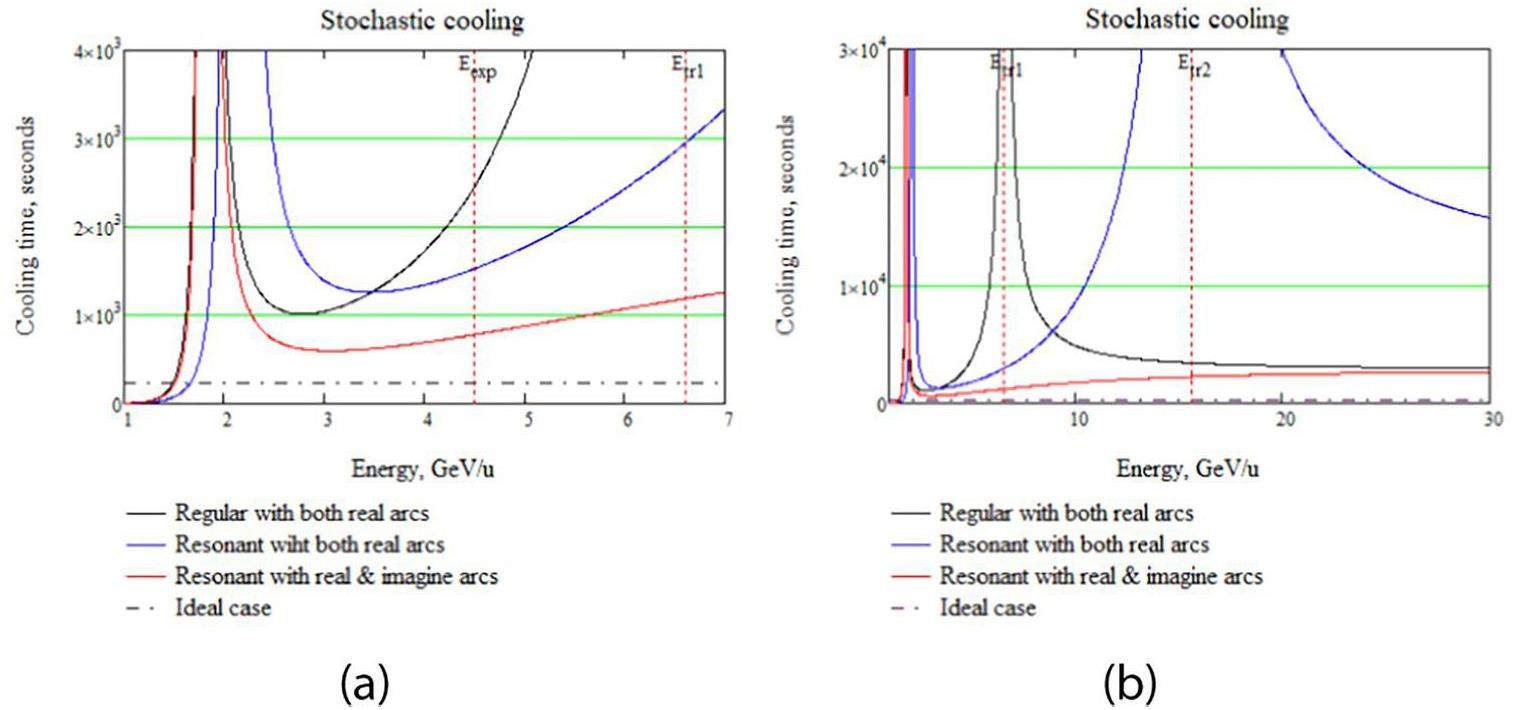

As illustrated in Fig. 5, “resonant” optics with increased transition energy up to γtr = 15, the second asymptotic is at higher energy compared to the “regular” lattice. In “combined” magneto-optics, the cooling efficiency is closer to the ideal value in a large energy range from 2.5 to 4.5 GeV/u, while in “regular” optics the cooling rate is almost two times lower at the most optimal point ~3 GeV/u. This behavior is explained by the absence of a second point of asymptotic growth.

Intrabeam Scattering

Intrabeam scattering represents a fundamental limitation on the beam lifetime in the collider. Consequently, the selection of an appropriate cooling technique depends on comparing its characteristic timescales with the rate at which the beam is heated owing to intrabeam scattering. This is derived from the fundamental principles that govern the process

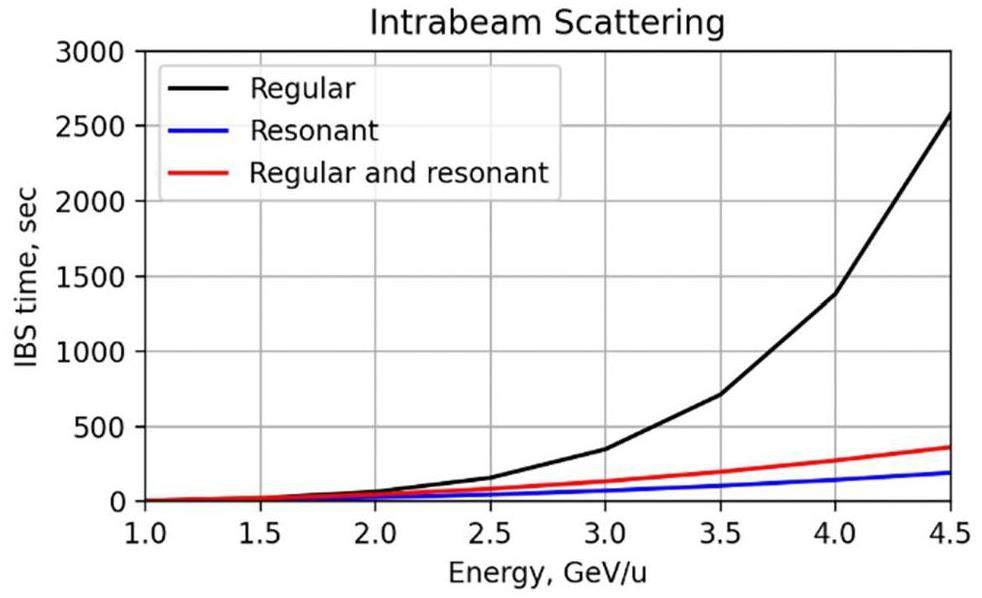

Unlike stochastic cooling, the IBS rate increases as decreasing energy

| Lattice | Regular | Resonant | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy, per nucleon (GeV/u) | 4.5 | 12.6 | 12.6 |

| Transition energy, γtr | 7 | 15 | i50 |

| Modulation depth | – | 25% | 45% |

| Cooling time at 4.5 GeV/u (s) | 2500 | 1500 | 800 |

| Heavy ions |

2500 | 400 | 250 |

| Protons |

1.8 × 104 | 4.5 × 103 | 7.9 × 103 |

| Tunes | 9.44/9.44 | 9.44/9.44 | 9.44/9.44 |

From the comparison of the IBS lifetime with the cooling time it can be concluded that in a regular lattice, stochastic cooling is able to balance intrabeam scattering in the energy range

Summary

The dual magneto-optical structure is proposed for accelerating both heavy ion and light particle beams, exemplified by the NICA facility. For light particles, owing to their charge-to-mass ratio, the experimental energy can rise above the lattice transition energy, which is optimal for heavy ions. Using dispersion modulation, transition energy increases or even reaches a complex value in a “resonant” lattice. However, owing to the modulation of β-function and D dispersion, the intrabeam scattering time decreases, which is crucial for multiply charged heavy particles. For this reason, a “regular” lattice with minimally modulated dispersion and β-function is optimal in the heavy-ion mode. Despite the fact that stochastic cooling in “regular” lattices is significantly weaker than in “resonant” and “combined” ones, it can compensate IBS effect.

No special changes are required to convert the “regular” lattice into a “resonant” one. This is sufficient to introduce only a separate family of quadrupoles.

Theory of “Resonant” lattices for synchrotrons with negative momentum compaction factor

. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 105, 988-997 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063776107110118Construction of “resonant” magneto-optical lattices with controlled momentum compaction factor

. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 105, 1141-1156 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063776107120060Particle accelerator

.Particle accelerator

.Magneto-optical structure of the NICA collider with high transition energy

. Phys. Atom. Nuclei. 84, 1734-1742 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778821100185Physics and technique of stochastic cooling

. Phys. Rep. 58, 75 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(80)90140-4The status of stochastic cooling

. Nuc. Inst. Methods Phys. Res. A 391, 164-171 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(97)00360-4Stochastic cooling in Fermilab

. Nuc. Inst. and Methods Phys. Res. A 391, 172-175 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(97)00358-6Beam cooling and related topics

.Beam-cooling methods in the NICA project

. Phys. Part. Nuclei Lett. 9, 322-336 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477112040206NICA cooling program

. Cybern. Phys. 3, 137-146 (2014) https://inspirehep.net/literature/1826533