Introduction

The nuclear charge radius RC is a fundamental property of atomic nuclei and plays a crucial role in research on nuclear structures [1]. It provides insights into various phenomena, including shape coexistence [2], neutron skin [3-5], proton halo [6], shell structure [7], odd-even staggering [8, 9] and nuclear matter saturation [10]. There are two main experimental methods for measuring RC. One directly determines RC through experiments such as muonic atom X-ray spectroscopy (

Many theoretical models have been developed to study RC, from macroscopic formulas to sophisticated microscopic approaches. First, a conventional approach to estimate RC is a semi-empirical formula based on the A1/3 law or the Z1/3 dependence of the liquid drop model, improved by introducing effects such as shell structure, isospin, and odd-even nuclear effects [22-24]. Subsequently, local-relation-based models determine RC from the properties of neighboring nuclei [25-28], with prominent examples being the Garvey-Kelson relation [29, 30] and mirror nuclei relation [31, 32]. Additionally, more sophisticated mean-field nuclear structure models offer self-consistent descriptions of RC and other nuclear properties. Examples include the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov (HFB) models [33-36], relativistic mean-field (RMF) models [37-41], and relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov (RHB) models [42-44]. Recent studies in Refs. [45, 46] have systematically calculated properties such as nuclear binding energy, charge radii, and electric quadrupole moment based on the deformed RHB theory in continuum. Finally, a class of ab initio approaches, such as the no-core shell model (NCSM), starts from realistic nucleon interactions and provides a precise description of RC by solving the many-body Schrödinger equation or the corresponding self-consistent field equations [47, 48]. Theoretical models have achieved significant advancements, reducing root-mean-square errors to below 0.05 fm and providing satisfactory descriptions of the unique behaviors of RC in isotope chains. However, as the accuracy requirements for calculations increase, the complexity of theoretical models also increases significantly.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) techniques have been widely applied in nuclear physics [49, 50], including nuclear mass studies [51-59], charge density distributions [60, 61], nuclear decay [62-66], and nuclear reactions [67-69], particularly for predicting RC [70-75]. Initially, the ML method was applied to train the experimental values of RC, independent of the theoretical models. As early as 2013, researchers have utilized artificial neural networks (ANN) to predict RC by directly generating a formula [70]. Subsequently, to incorporate the strengths of the theoretical models, ML techniques were employed to refine them by estimating the residuals between the theoretical and experimental values of RC. Early work in 2016 proposed a Bayesian neural network (BNN) with a single hidden layer to optimize these predictions [71]. Later, multiple research groups significantly enhanced the robustness of BNN by introducing physical effects and adding input features [72-74]. Notably, the naive Bayesian probability (NBP) classifier, which applies Bayesian theory and k-means clustering, reframes the prediction of RC as a classification task. This approach demonstrated strong extrapolation capabilities and provided uncertainty in prediction [75, 76].

Recently, the application of the continuous Bayesian probability (CBP) estimator and the Bayesian model averaging (BMA) further improved the reliability of nuclear mass descriptions [77]. Unlike the NBP method, which discretizes the residuals δ of the theoretical model, the CBP estimator considers δ as a continuous variables. By combining the Bayesian framework with kernel density estimation (KDE), the CBP estimator derives a posterior probability density function (PDF) of δ for the target nuclei. This method demonstrates a robust predictive performance and can explain intrinsic numerical relationships. Moreover, the BMA method combines the predictive strengths of different theoretical models across distinct regions of the nuclear chart, further improving overall performance [78-80].

This study combines the CBP estimator and BMA method to optimize the predictions of RC. The initial theoretical values of RC were calculated separately using the HFB, RHB, and semi-empirical liquid drop models. First, the global optimization capability of the CBP estimator was evaluated by comparing its predictions with experimental data from the 2013 compilation of nuclear charge radii [16]. Subsequently, its extrapolation capability was investigated using the learning set from the 2004 compilation [11] to predict RC for nuclei newly reported in the 2013 compilation. After optimization using the CBP estimator, to further improve the predictive accuracy for nuclei near the drip line, the BMA method was applied to assign weights to each model based on their predictive performance on the benchmark nuclei. The benchmark nuclei selected in this study are 49K [81], 38Ca [82], 100Cd, 119Cd [83], 201Po [84], and 233Ra [85]. Finally, we predict RC of the Ca and Sr isotopic chains using the CBP estimator in combination with the BMA method to verify the ability of this approach to capture the physical effects on RC. The approaches proposed in this study can be used to investigate RC of unknown nuclei, with potential applications in the study of other nuclear properties.

This paper is structured in three sections: Sect. 2 introduces the theoretical framework of the CBP and BMA methods. Section 3 presents the results of these methods. Section 4 provides the summary of this study.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework offers detailed procedures and formulas for a continuous Bayesian probability (CBP) estimator and the Bayesian model averaging (BMA). A method for evaluating the predictive performance and a formula for quantifying the uncertainties are also presented.

The continuous Bayesian probability method

In the CBP estimators, the residuals δ of RC are treated as continuous variables and their posterior PDFs are derived from Bayesian theory. The estimated residuals, which are used to correct the theoretical models, can then be calculated from the posterior PDFs.

For continuous multivariate variables, given a set of features or variables

According to Eq. (1), event Y represents the continuous residual δ. Events Xi correspond to the proton number Zt and neutron number Nt of the target nucleus. It is assumed that Zt and Nt are independent of other variables. Thus, the posterior PDF can be expressed as

When determining the likelihood PDF and prior PDF, a weight function is introduced to account for the local relationship between neighboring nuclei:

Bayesian model averaging

Even after refinement by the CBP estimator, individual models often fail to comprehensively account for all physical phenomena, owing to their varying strengths and weaknesses in different regions of the nuclear chart. To consider the advantages of different models in the isotopic and isotonic chains, Bayesian model averaging (BMA) was introduced [86].

The BMA method is based on the Bayesian theorem, and assigns weights to each model by assessing its predictive performance. Specifically, given a set of K candidate models

Results

In this section, the theoretical values of RC are initially calculated using the HFB model with SLy4 parameterization, RHB model with the PC-PK1 parameter set [87], and three-parameter semi-empirical formula of Sheng et al. [88]. Notably, the RHB model is based on the relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory, and incorporates nucleon intrinsic electromagnetic structure corrections [89, 90]. Subsequently, the initial results were refined by employing the CBP estimator and BMA method. The entire set comprises 892 nuclei with proton numbers Z>3 sourced from the 2013 charge radii compilation [16]. The global optimization and extrapolation capabilities of the CBP estimator are evaluated, followed by an analysis of the extrapolation performance of the approach that combines the CBP and BMA methods.

Global optimizations of the CBP estimator

The theoretical RC values of 892 nuclei were calculated using three models, and the raw residuals

| Methods | HFB | RHB | Sheng | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBP | σpre | 0.040 | 0.047 | 0.042 |

| σpost | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.016 | |

| 60.0% | 63.8% | 61.9% | ||

| NBP | σpost | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.023 |

| 50.0% | 55.3% | 45.2% |

As shown in Table 1, the standard deviations σpre for the spherical HFB, RHB, and semi-empirical formulas are approximately 0.04 fm. However, the deformed mean-field theories give a standard deviation of approximately 0.03 fm [41, 42]. After refining using the CBP estimator, the standard deviations σpost for both spherical models are further reduced to approximately 0.016 fm, representing an improvement of approximately 60%. This improvement demonstrates the advantages of the CBP estimator. The CBP estimator can introduce deformation effects into the calculations of spherical theoretical models using statistics, thereby improving the description of RC for deformed atomic nuclei.

To illustrate the progress achieved by the CBP method, Table 1 presents the optimization performance of the NBP method for comparison. The NBP method is a discrete Bayesian probabilistic approach that employs the k-means algorithm to determine the cluster centers δi, which are then used to refine the theoretical models. For the three models, the improvement rate of the CBP method is approximately 10% higher than that of the NBP method. This arises from the CBP estimator treating residuals as continuous variables and obtaining the estimated residual value δem by integrating the posterior PDF over the entire residual distribution, rather than using a discrete posterior probability, as in the NBP method. The CBP estimator accounts for all possible residual contributions, thereby achieving a higher degree of optimization and demonstrating a clear advantage.

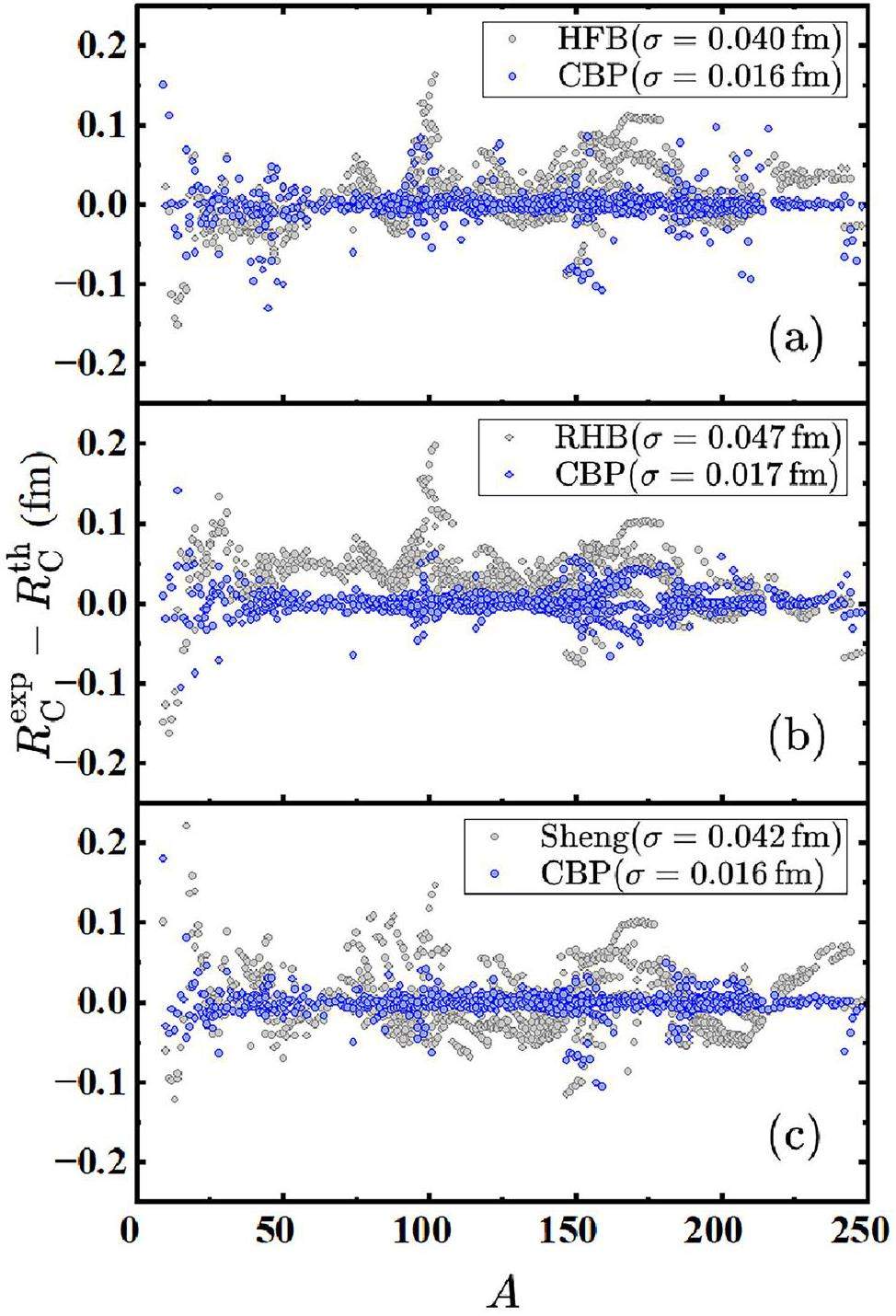

To further illustrate the performance of the CBP estimator across the different models and regions, Fig. 1 presents the raw residuals (gray dots) from the HFB model, the RHB model and the semi-empirical formula, along with the corrected residuals (blue dots) after applying the CBP estimator. It is evident that after CBP optimization, the residuals for all three theoretical models were remarkably reduced across most regions. This improvement can be attributed to the CBP estimator framework. Based on the global description of theoretical models, the CBP estimator utilizes a statistical approach to further capture the local correlation effects among nuclei with identical proton or neutron numbers. The introduction of the weight function ensures that only nuclei in close proximity to the target nucleus on the nuclear chart significantly influence the prediction, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of the CBP estimator to local correlation effects. Therefore, the CBP estimator is more effective in regions where local correlations are stronger, and the distribution of δpre is more regular, such as regions with pronounced shell effects.

In regions 60<A<90, 120<A<140, and 215<A<240 in Fig. 1a; 45<A<90, 110<A<140, and 220<A<240 in Fig. 1b; and 80<A<95, 110<A<145, and 210<A<240 in Fig. 1c, where theoretical model predictions exhibit similar accuracy and the distribution of δpre is highly regular, the CBP estimator achieves substantial improvements, considerably reducing the residuals. In particular, for nuclei with mass numbers around A=100, A=150, and A=190, where proton-neutron residual interactions and other physical effects lead to large δpre, the CBP method markedly enhances the predictive accuracy by statistically accounting for these interactions and effects. However, for light nuclei, where δpre exhibits greater variability owing to relatively low nucleon numbers, the optimization effect of the CBP estimator is comparatively limited. As more charge radii of light nuclei are precisely measured in experiments, the predictive performance of the CBP estimator for light nuclei can be further enhanced.

Extrapolating capabilities of the CBP estimator

Model extrapolation was essential for the acquisition of unknown data. In this section, we evaluate the extrapolation performance of the CBP estimator. The learning set comprised 790 nuclei with proton numbers Z > 3 from the 2004 charge radii compilation [11], while the validation set included 102 experimental charge radii added between 2004 and 2013. The bandwidth parameters

| Models | Learning set | Validation set | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σpre | σpost | σpre | σpost | |||

| HFB | 0.040 | 0.017 | 57.5% | 0.038 | 0.021 | 44.7% |

| RHB | 0.046 | 0.017 | 63.0% | 0.052 | 0.025 | 51.9% |

| Sheng | 0.042 | 0.018 | 57.1% | 0.043 | 0.026 | 39.5% |

According to Table 2, the standard deviations of RC calculated using the HFB, RHB, and semi-empirical formulas are approximately 0.040 fm for both the learning and validation sets. This consistency indicates that the initial theoretical models possess considerable extrapolation capabilities, which are more beneficial for the CBP estimator in predicting unknown regions. After applying the CBP estimator, the standard deviations for all three models in the learning set decreased to less than 0.020 fm, achieving an improvement of approximately 60% compared to the initial results. In the validation set, the standard deviations were slightly greater than 0.020 fm, with improvement rates of approximately 45% for the three models. The steady improvement rates across both the learning and validation sets demonstrate the robust extrapolation capabilities of the CBP estimator.

The optimization rates for all three models in the validation set were lower than those in the learning set. This phenomenon can be explained by the CBP framework: the Bayesian formula accounts for statistical correlations among nuclei with the same proton and neutron numbers, whereas the weight function considers local relationships among neighboring nuclei. Most nuclei in the validation set were positioned near the drip line, where fewer neighboring nuclei were represented in the learning set, thereby diminishing the performance of the CBP estimator. As more RC values were measured experimentally, the extrapolation ability of the CBP estimator was expected to improve significantly.

The results in Table 2 indicate that the CBP estimator demonstrates excellent extrapolation capabilities. The HFB, RHB and semi-empirical formulas provide the overall trends of RC variations. By inheriting the advantages of theoretical models and incorporating local correlation characteristics between nuclei, the CBP estimator captures the physical effects that are not reflected in theoretical models, leading to reliable corrections of RC. Consequently, for nuclei lacking experimental data, the CBP estimator can offer precise and robust predictions.

Comprehensively factoring in the results of different models using the BMA method

After optimization using the CBP estimator, specific models exhibited optimal predictive performance in distinct regions, especially for nuclei far from the β-stability line. This study introduces the BMA method to integrate these strengths. The BMA method assigns weights based on the predictive performance of different models for the benchmark nuclei. To balance the predictive discrepancies between the theoretical models across different regions of the nuclear chart, the benchmark nuclei selected for the BMA method were 49K, 38Ca, 100Cd, 119Cd, 201Po, and 233Ra, which cover a wide range of the nuclear chart, including from light nuclei to heavy nuclei, and from proton-rich regions to neutron-rich regions. These selected nuclei are located near the edges of the nuclear chart and are outside the 2013 charge radii compilation, making them particularly valuable for benchmarking extrapolation capabilities.

After obtaining the corrected residuals

| Models | 49K | 38Ca | 100Cd | 119Cd | 201Po | 233Ra | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFB | 0.017 | -0.003 | -0.017 | 0.007 | 0.007 | -0.006 | 0.49 |

| RHB | -0.015 | 0.010 | 0.008 | -0.006 | -0.017 | 0.009 | 0.38 |

| Sheng | 0.013 | 0.013 | -0.014 | 0.010 | 0.018 | -0.011 | 0.13 |

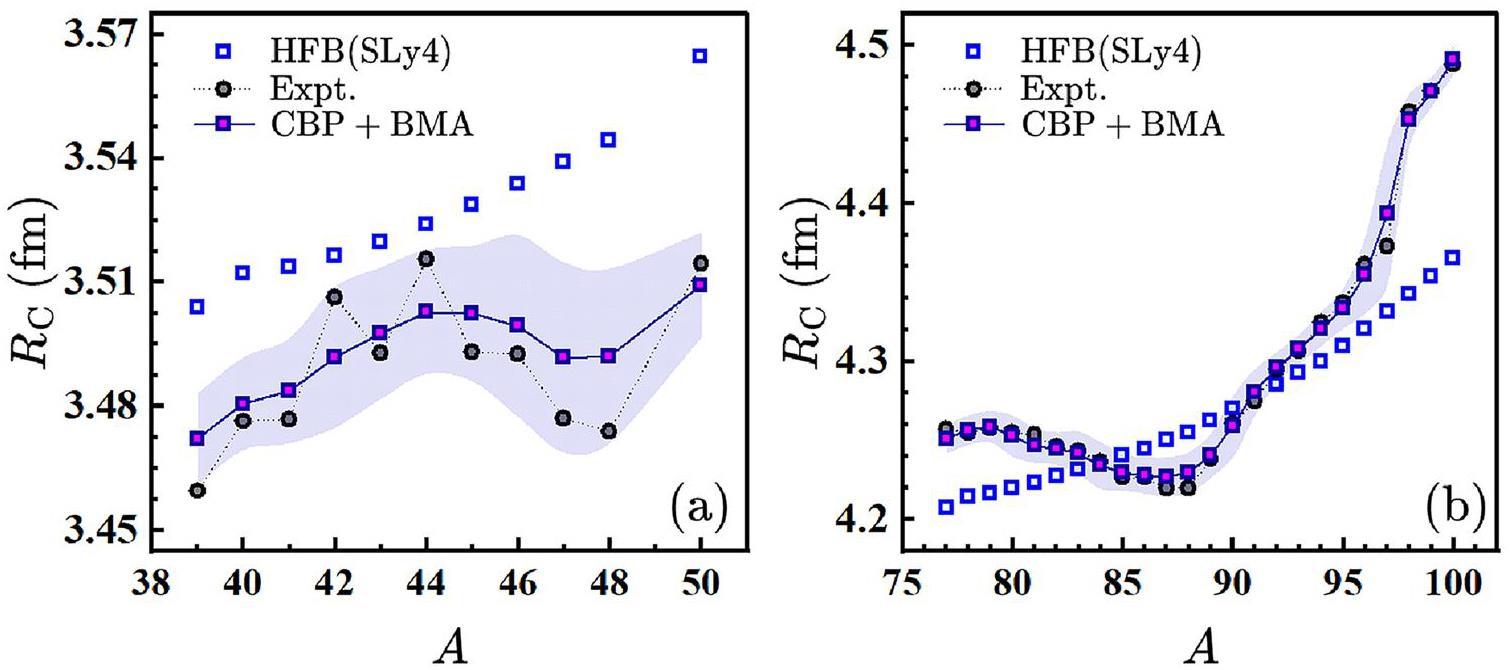

Analysis of the trend of variation in charge radii within isotopic chains reveals many important and interesting physical phenomena. This study combines the CBP and BMA methods to predict the RC of the Ca and Sr isotopic chains, illustrating the capability of this approach to capture the physical effects within the isotopic chains. The calcium isotopic chain serves as a distinctive nuclear system for investigating interactions between protons and neutrons inside the nucleus [91-93]. In the stable isotope region of the Ca chain, 40Ca and 48Ca both exhibit a large number of protons and neutrons, and their RC values are nearly identical. Owing to the change in the nuclear structure associated with shell closure, a kink in RC at N = 28 is observed. For 20 < N < 28, the trend of RC follows a parabolic shape, and the odd-even staggering effect on RC is particularly pronounced. For neutron-rich nuclei with N > 28, RC exhibited a strong increase.

Figure 2a presents the predicted charge radii

The experimental charge radii in Fig. 2a clearly show the shell effect and odd-even staggering. However, the odd-even staggering is diluted in the RC predicted using the CBP estimator combined with the BMA method. This is because the calculation of the CBP estimator relies on nuclides with the same proton number Z or neutron number N, which leads to a weakening of the odd-even staggering effect. The introduction of the BMA method combines the results of the three models, further diluting the odd-even staggering effect.

In addition to Ca isotopes, the charge radii of Sr isotopes also exhibit prominent shell effects [94]. The Sr isotope chain extends from the valley of stability at 88Sr, where isotopes show a spherical shape, to the strongly deformed isotopes on either side of the stability line. As the nucleus approached the neutron shell closure at N=50 from the neutron-deficient side, RC gradually decreased. At N=50, it exhibited a kink, after which it began to increase. When N reached 60, a sudden increase in RC was observed, corresponding to an experimental transition from a near-spherical shape to a strongly deformed configuration [95]. The refined predictions

Summary

This study combined the continuous Bayesian probability (CBP) estimator with Bayesian model averaging (BMA) to refine RC predictions from the HFB, RHB, and semi-empirical formulas. In global optimization, the CBP estimator achieved an improvement of approximately 60% for all three models. In extrapolation, it demonstrates an improvement rate of approximately 45%. These results indicate that, based on sophisticated theoretical models, the CBP estimator can provide accurate predictions of RC in the unknown regions of the nuclear chart. To enhance the predictive accuracy for nuclei near the drip line, the BMA method was subsequently employed to assign weights to each model based on their predictive performance for the benchmark nuclei. By combining the CBP estimator with the BMA method, the standard deviation is further reduced, and the physical phenomena on RC such as shell effects in the Ca and Sr isotopic chains, are accurately captured.

The improvements achieved by the proposed method are attributed to the theoretical frameworks of the CBP estimator and the BMA method. According to the CBP estimator framework, a continuous posterior probability density function (PDF) was generated to obtain the estimated residuals for the target nucleus. The Bayesian formula captures the statistical relationships among nuclei with the same proton or neutron number, whereas the weight function accounts for the local correlations among neighboring nuclei. The theoretical models provide the overall trend of RC, and the CBP estimator reliably refines these theoretical results through statistical techniques. Thus, the BMA method combines the strengths of different models across various regions of the nuclear chart, leading to further refinement of the results.

In summary, the CBP and BMA methods were effectively employed to predict the nuclear masses and charge radii, demonstrating considerable predictive accuracy. The methodologies developed in this work can be further extended to estimate charge radii in regions far from the β-stability line, and are equally applicable to the exploration of other nuclear properties, including nuclear reactions and decay processes.

Self-consistent mean-field models for nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 121-180 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.75.121Shape coexistence in atomic nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1467-1521 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1467Trends of Neutron Skins and Radii of Mirror Nuclei from First Principles

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Neutron skin and its effects in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01584-1Analysis of parity-violating electron scattering on deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Masses and Charge Radii of 17-22Ne and the Two-Proton-Halo Candidate 17Ne

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101,Evolution of shell structure in exotic nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92,Measurement and microscopic description of odd-even staggering of charge radii of exotic copper isotopes

. Nat. Phys. 16, 620-624 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-0868-yOdd-even staggering and shell effects of charge radii for nuclei with even Z from 36 to 38 and from 52 to 62

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Δisobars and nuclear saturation

. Phys. Rev. C 97,A consistent set of nuclear rms charge radii: properties of the radius surface R(N,Z)

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 87, 185-206 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2004.04.002Elastic electron scattering from light nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 47, 245-318 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-6410(01)00156-9First Observation of Electron Scattering from Online-Produced Radioactive Target

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Nuclear Ground State Charge Radii from Electromagnetic Interactions

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 60, 177-285 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.1995.1007Nuclear Charge Radius of 12Be

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108,Table of experimental nuclear ground state charge radii: An update

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 99, 69-95 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2011.12.006Compilation of recent nuclear ground state charge radius measurements and tests for models

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 140,Nuclear Charge Radii of Silicon Isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132,Nuclear Charge Radius of 26mAl and Its Implication for Vud in the Quark Mixing Matrix

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Surprising Charge-Radius Kink in the Sc Isotopes at N=20

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Deformation versus Sphericity in the Ground States of the Lightest Gold Isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Isospin and Z1/3-dependence of the nuclear charge radii Eur

. Phys. J. A 13, 285-289 (2002) https://doi.org/10.1007/s10050-002-8757-6Simple formula for nuclear charge radius

. Z. Phys. A 348, 169-172 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01291913Shell and isospin effects in nuclear charge radii

. Phys. Rev. C 88,New charge radius relations for atomic nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Predictions of nuclear charge radii

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Local relations of nuclear charge radii

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Evaluation of nuclear charge radii based on nuclear radii changes

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Garvey-Kelson relations and the new nuclear mass tables

. Phys. Rev. C 77,Garvey-Kelson relations for nuclear charge radii

. Eur. Phys. J. A 46, 379-386 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2010-11051-8Improved mass relations of mirror nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 157 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01501-6Correlations between charge radii differences of mirror nuclei and stellar observables

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Systematic study of deformed nuclei at the drip lines and beyond

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Further explorations of Skyrme-Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov mass formulas. XVI. Inclusion of self-energy effects in pairing

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Simple corrections in theoretical models of atomic masses and nuclear charge radii

. Phys. Rev. C 106,New extended method for Ψ’ scaling function of inclusive electron scattering

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 66,Relativistic Mean Field Theory for Deformed Nuclei with Pairing Correlations

. Prog. Theor. Phys 110, 921-936 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.110.921Nucleon momentum distribution of 56Fe from the axially deformed relativistic mean-field model with nucleon-nucleon correlations

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 64,Accuracy of the mean-field theory in describing ground-state properties of light nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Influence of single-particle energy on inclusive electron scattering

. J. Phys. G 50,Effects of nucleon-nucleon short-range correlations on inclusive electron scattering

. Phys. Rev. C 105,The limits of the nuclear landscape explored by the relativistic continuum Hartree–Bogoliubov theory

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 121-122, 1-215 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2017.09.001Strutinsky shell correction energies in relativistic Hartree-Fock theory

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Nuclear charge radii and shape evolution of Kr and Sr isotopes with the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree–Bogoliubov theory in continuum, I: Even–even nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 144,Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree–Bogoliubov theory in continuum, II: Even-Z nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 158,Ab Initio Nuclear Thermodynamics

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125,Ab initio no core shell model

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 69, 131-181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2012.10.003Colloquium: Machine learning in nuclear physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94,Machine learning in nuclear physics at low and intermediate energies

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 66,Bayesian approach to model-based extrapolation of nuclear observables

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Beyond the proton drip line: Bayesian analysis of proton-emitting nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Comparative study of radial basis function and Bayesian neural network approaches in nuclear mass predictions

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Nuclear mass predictions with machine learning reaching the accuracy required by r-process studies

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Predicting nuclear masses with the kernel ridge regression

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Nuclear mass predictions based on a convolutional neural network

. Phys. Rev. C 111,Nuclear mass based on the multi-task learning neural network method

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01031-zMachine learning the nuclear mass

. Nuc. Sci. Tech. 32, 109 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00956-1Nuclear mass predictions using machine learning models

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Prediction of nuclear charge density distribution with feedback neural network

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01140-9Global prediction of nuclear charge density distributions using a deep neural network

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Comparative study of neural network and model averaging methods in nuclear β-decay half-life predictions J

. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 51,Bayesian optimization approach to model-based description of α decay

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Predictions of nuclear β-decay half-lives with machine learning and their impact on r-process nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Nuclear β-decay half-life predictions and r-process nucleosynthesis using machine learning models

. Phys. Rev. C 111,Predicting β-decay energy with machine learning

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Optimizing multilayer Bayesian neural networks for evaluation of fission yields

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Bayesian approach to heterogeneous data fusion of imperfect fission yields for augmented evaluations

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Bayesian evaluation of charge yields of fission fragments of 239U

. Phys. Rev. C 103,An artificial neural network application on nuclear charge radii

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 40,Nuclear charge radii: density functional theory meets Bayesian neural networks

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 43,Novel Bayesian neural network based approach for nuclear charge radii

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Nuclear charge radii in Bayesian neural networks revisited

. Phys. Lett. B 838,Investigation of the difference in charge radii of mirror pairs with deep Bayesian neural networks

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Predictions of nuclear charge radii and physical interpretations based on the naive Bayesian probability classifier

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Improved naive Bayesian probability classifier in predictions of nuclear mass

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Novel Bayesian probability method in predictions of nuclear masses

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Uncertainty quantification of mass models using ensemble Bayesian model averaging

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Neutron Drip Line in the Ca Region from Bayesian Model Averaging

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Uncertainty quantification of mass models using ensemble Bayesian model averaging

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Charge radii of neutron-deficient 36K and 37K

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Proton superfluidity and charge radii in proton-rich calcium isotopes

. Nat. Phys. 15, 432-436 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0416-9From Calcium to Cadmium: Testing the Pairing Functional through Charge Radii Measurements of 100-130Cd

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Charge radii of odd-A Po isotopes

. Phys. Lett. B 719, 362-366 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.01.043g, Laser-spectroscopy studies of the nuclear structure of neutron-rich radium

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Nuclear mass predictions with the naive Bayesian model averaging method

. Nucl. Phys. A 1043,New parametrization for the nuclear covariant energy density functional with a point-coupling interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 82,An effective formula for nuclear charge radii

. Eur. Phys. J. A 51, 40 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2015-15040-1Finite-nuclear-size effect in hydrogenlike ions with relativistic nuclear structure

. Phys. Rev. A 107,Impact of intrinsic electromagnetic structure on the nuclear charge radius in relativistic density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Unexpectedly large charge radii of neutron-rich calcium isotopes

. Nat. Phys. 12, 594-598 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3645Charge radii of Ca isotopes and correlations

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Radial and orbital decomposition of charge radii of Ca nuclei: Comparative study of Skyrme and Fayans functionals

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Nuclear Charge Radii of 78-100Sr by Nonoptical Detection in Fast-Beam Laser Spectroscopy

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 2607-2610 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.60.2607Nuclear charge radii and shape evolution of Kr and Sr isotopes with the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 108,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.