Introduction

In recent years, an increasing number of high-intensity proton or heavy- ion accelerators have been proposed, are under construction, or have begun operate worldwide for various scientific and industrial applications. For such high-intensity accelerators, studies on the mechanism of intense beams and the control of beam losses are of key importance for machine design and operation. One of the most important contributors to beam quality degradation is the formation of a beam halo driven by space charge [1-13]. The main driven source of the beam halo is parametric resonance, which causes severe beam losses (see, for example, [14-16]). Uncontrolled beam losses can cause severe consequences such as the residual activation of beam pipes, quenching of superconducting magnets, vacuum degradation, and radiation damage to insulation materials [17-20]. One of the most widely employed approaches for studying beam halos is the particle-core model (PCM) [21-30]. Compared with particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations, the PCM method is an analytical tool for investigating beam dynamics, particularly for the mechanism of beam halo formation, without requiring much particle tracking, which can be time-consuming. In this model, the dynamic behavior of an intense beam core is described by the evolution of the beam envelopes [31, 32]. The motion of a single particle is affected by the space charge of beam–core mismatch oscillations [33-38]. This becomes more complicated for high-intensity hadron synchrotrons, where the combined effect of space charge and dispersion plays a role in the motion of circulating beams [39-43]. To analyze beam halo formation in circular machines, the conventional PCM method must be generalized to include dispersion.

In this paper, we investigate the dynamics of halo particles in the presence of both moderate and strong space charge, where 2:1 and higher-order resonances or even chaos exist. Furthermore, based on the generalization of the conventional PCM method to a case with the dispersion effect for high-intensity synchrotrons, a novel “1:1 parametric resonance” driven by the dispersion mode is identified. We also explain the damping effect observed by Ikegami et al. [39] from the perspective of the oscillation modes. For beams with large mismatch oscillations, we discuss the high- and low-order resonances driven by the high- and low-order beam-core oscillation modes.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Following this introduction, we briefly discuss the fundamentals of the PCM method in Sect. 2. The single-particle dynamics of round and elliptical beams are investigated in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we generalize the PCM method to include dispersion, and the 1:1 parametric resonance driven by the dispersion mode is discussed in detail. An analysis of the high-order modes in the large beam mismatch oscillation is presented in Sect. 5. Finally, the summary is presented in Sect. 6.

Fundamentals

In the PCM, beams are assumed to have a uniform spatial density in the transverse plane (KV distribution) because the dynamics of a single particle are insensitive to the details of the beam-core distribution. An envelope approach is employed to describe the mismatch oscillations of the beam core. Beam halo formation is driven by the space-charge interaction between the collective envelope oscillation modes and single particles.

Beam-core oscillations

Let us begin with a coasting beam propagating through a uniformly focusing structure. Such a structure can be used to describe the average dynamic behavior of beams in an alternating gradient focusing channel [31] (i.e., the smooth approximation method). For simplicity, henceforth, we neglect any impedance effects caused by the beam pipe and all the chromatic terms. We adopt x and y to represent the transverse degrees of freedom in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively, and s the longitudinal coordinate. The “pseudo” Hamiltonian of the beam envelope oscillation in such a transport system is

The envelope equations in Eq. (2), which are typically employed to describe the oscillatory motion of the beam core, can be converted into a dimensionless form with a set of dimensionless variables, defined by

The corresponding dimensionless form of the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) and envelope equations in Eq. (2) can be respectively expressed as

Single-particle motion with space charge of beam cores

In the presence of space charge, the horizontal motion of a test particle is governed by

For particles inside the beam core, the wavenumber becomes minimum: Substituting Eqs. (8) and (12) into Eq. (16), we obtain

However, when the test particle is far from the beam core, the space charge can be neglected (μx = 0), and Eq. (17) becomes

In the PCM, particles move periodically inside and outside the beam core. In particular, when the wavenumbers of a test particle and beam core satisfy

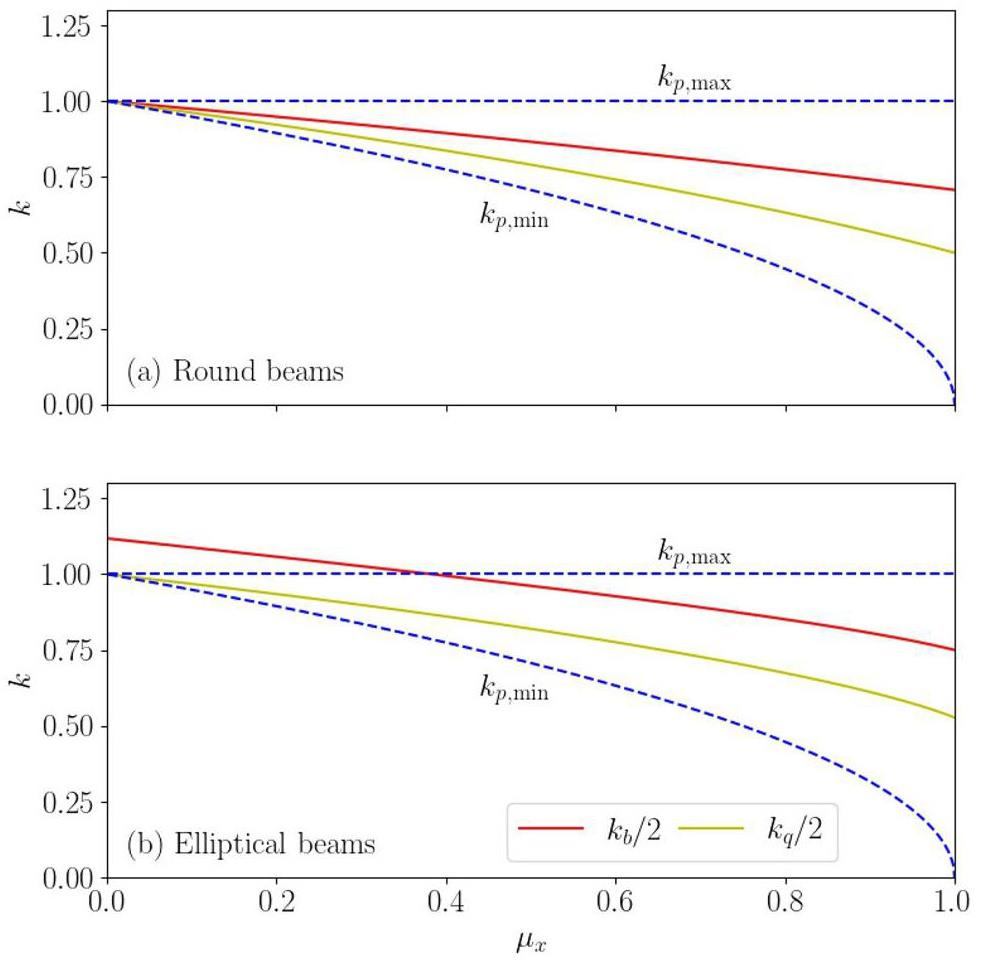

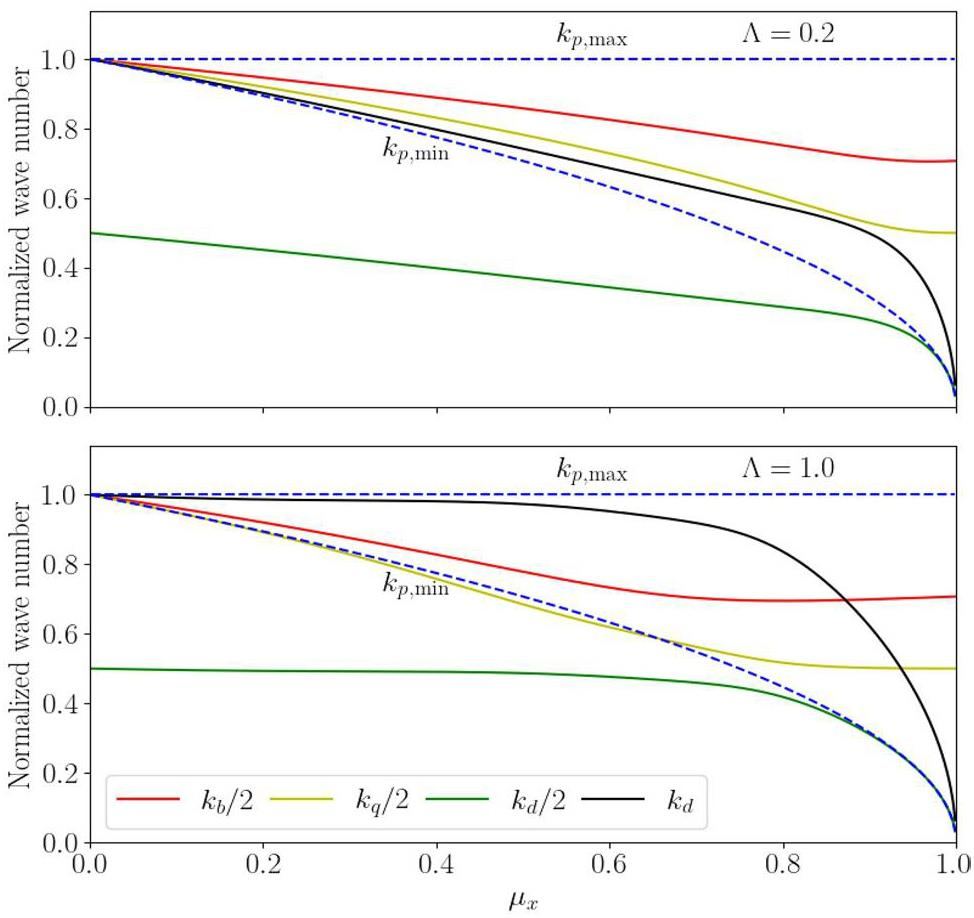

To illustrate this, we plot the wavenumbers as functions of the beam current (in units of the normalized space-charge tune depression μx defined in Eq. 5) by solving Eqs. (16) and (17) for two representative cases: round and elliptical beams. In Fig. 1, the blue dashed lines represent the two limits of the single-particle wavenumber

Figure 1a shows that for round beams, kp,min < kq/2, kb/2 < kp,max always holds as the beam current increases from the zero space charge limit (μx = 0) to the extreme space charge limit (μx = 1.0), indicating that both envelope modes can resonate with the test particle and drive the 2:1 parametric resonance. In comparison, for the elliptical beams shown in Fig. 1b, we obtain kp,min < kq/2, kb/2 < kp,max when μx > 0.39, which implies that the breathing mode can drive the 2:1 parametric resonance in the range of μx > 0.39. For μx < 0.39, we have kp,min < kq/2 < kp,max and kb/2 > kp,max. In this case, the 2:1 parametric resonance can only be driven by the quadrupole mode.

Resonance and chaos in the beam halo

In the presence of space charge, the motion of the particles around the beam core is periodic. When resonance occurs, the particles can absorb energy from the beam core and experience a much larger contour, forming halo particles. Furthermore, particles exhibit chaotic behavior with the superposition of different modes under a strong space charge. In this section, the 2:1 and higher-order parametric resonances and chaos in the beam halo formation are investigated in detail.

Round beams in the breathing mode

Let us consider a round beam traveling in a symmetric focusing channel with initial equal mismatch perturbations on x and y, for example ξ(0) = ξ(0) = 0.05, to excite a breathing mode on the beam (i.e., an in-phase pattern and 5% mismatch; the quadruple mode is absent here). We select four single particles with different initial (dimensionless) horizontal displacements,

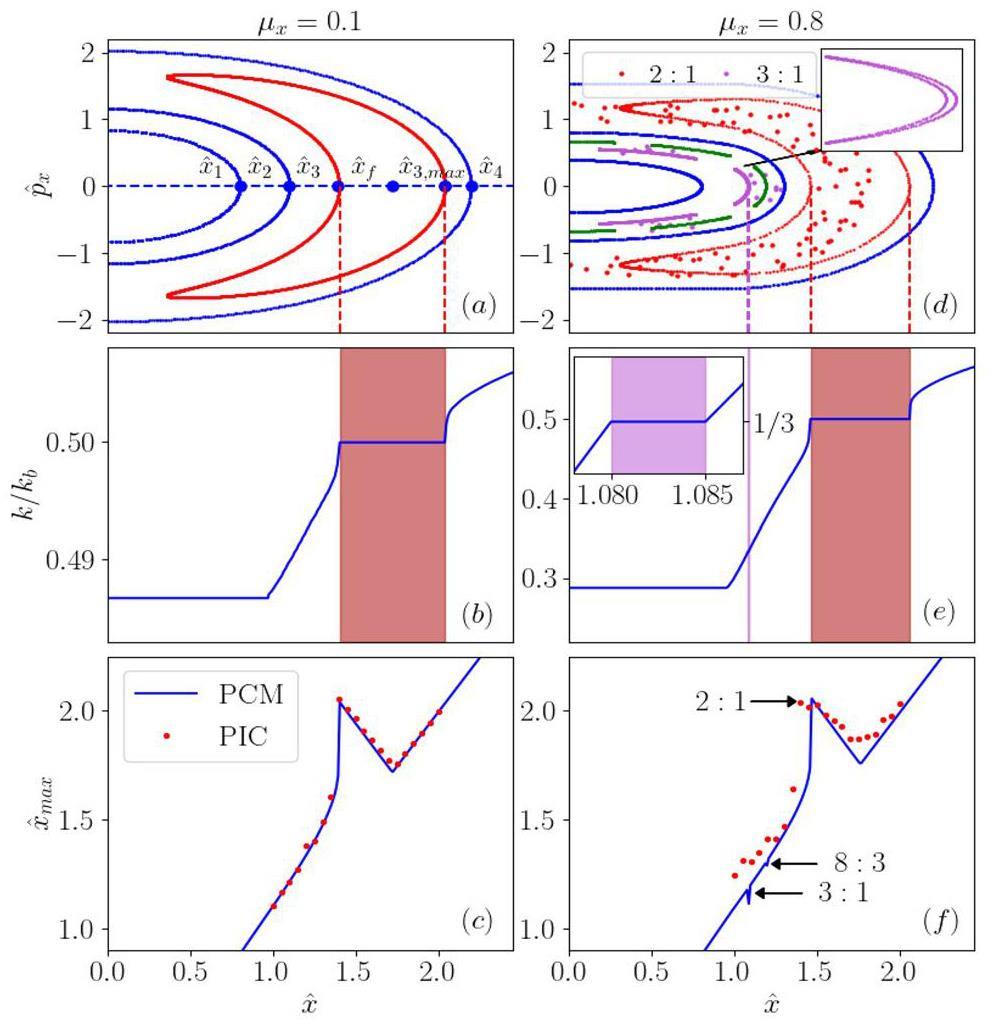

First, we analyze the moderate space charge case μx = 0.1. For the two test particles with initial positions

The “lock” of the wavenumber of the third particle in Fig. 2b is a typical characteristic of the parametric resonance. Within the resonance island (red contour in Fig. 2a), the wavenumber is equal to half of the wavenumber of the breathing mode (k = kb/2) in Fig. 2b. In comparison, the wavenumber increases outside the resonance region with a larger initial position (

PIC simulations were conducted using the PyORBIT code to support the above numerical results and analysis. In the simulation, a constant-focusing channel with 16 “equal cells” was employed. The main parameters used in the simulation are summarized in Table 1. The space charge solver is based on the fast Fourier transform (FFT) method [44]. The simulation results for the maximum displacement of the particles as a function of the initial displacement atμx = 0.1 are shown in Fig. 2c. The simulation results were in good agreement with the numerical solutions.

| Parameters | Round beam | Elliptical beam |

|---|---|---|

| Length per cell (m) | 14.2 | 14.2 |

| Phase advance in x (deg) | 108 | 100 |

| Phase advance in y (deg) | 108 | 112 |

| RMS emit. in x (mm·mrad) | 30 | 30 |

| RMS emit. in y (mm·mrad) | 30 | 30 |

| Beam intensity (particle numbers) | 1.18 × 1010 (μx = 0.1) | 1.07 × 1010 (μx = 0.1) |

| 20.0 × 1010 (μx = 0.8) | 7.05 × 1010 (μx = 0.5) | |

| 17.5 × 1010 (μx = 0.8) |

Second, with an enhanced space charge (μx = 0.8), the motion of single particles becomes more complicated, as shown in Fig. 2d–f (right). Compared with the moderate space charge case (μx = 0.1), three small islands are observed in addition to the 2:1 resonance island in Fig. 2d. A closer examination of Fig. 2e reveals that in the region of

PIC simulations with μx = 0.8 were also performed. As shown in Fig. 2d, the particles were trapped within the 2:1 resonance island (shown as red dots). The purple dots around the three islands indicate that the particles gathered around the 3:1 resonance island because of the weak 3:1 resonance. The simulation results for the maximum particle displacement are shown in Fig. 2f. These results agreed with the numerical calculations.

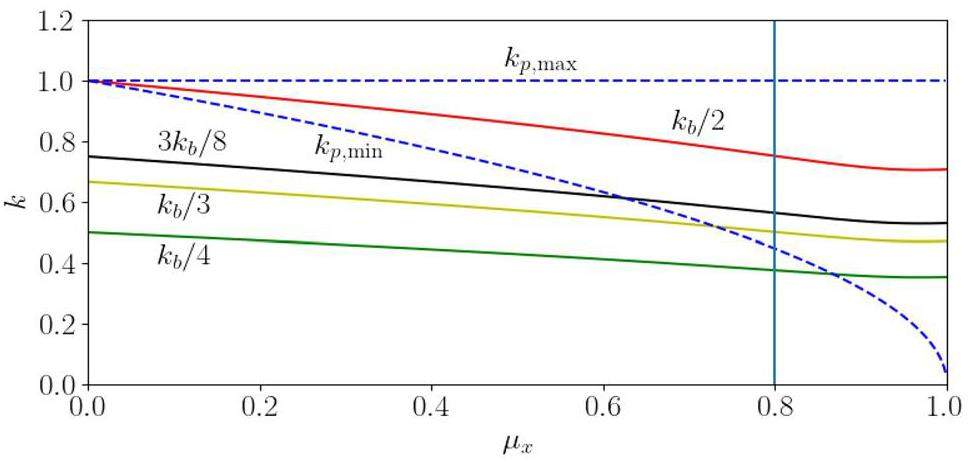

An interesting question may be raised as to whether the 4:1 parametric resonance exists and contributes to the beam halo for a strong space charge withμx = 0.8. As shown in Fig. 3, we obtain kb/4 < kp,min when μx = 0.8, indicating that a 4:1 or higher parametric resonance cannot be excited. In comparison, the condition kp,min < kb/3 < 3kb/8 < kp,max is satisfied when μx = 0.8, which supports the occurrence of the 3:1 and 8:3 resonance islands shown in Fig. 2.

Round beams with mixed modes

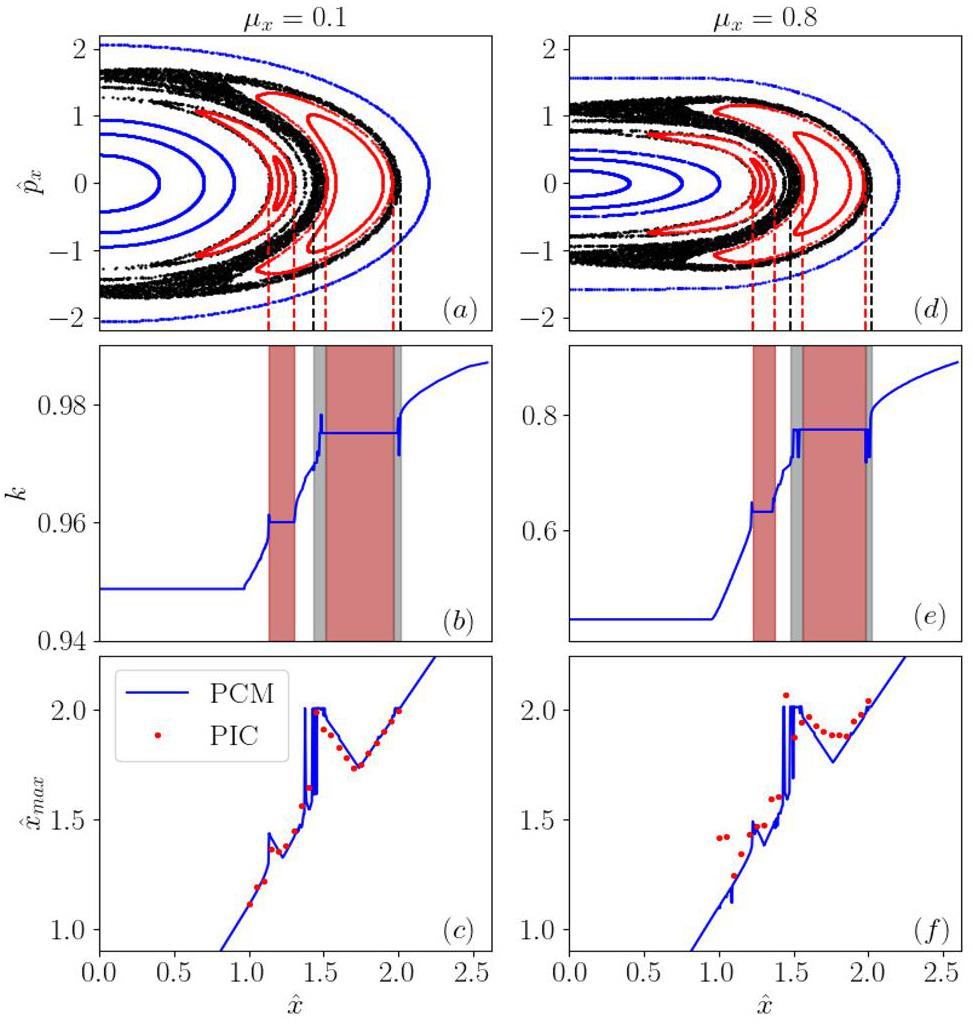

In this subsection, we consider a round beam perturbed withξ(0) ≠ξ(0), which can simultaneously drive both the breathing and quadrupole modes. The motion of single particles affected by the space charge of the two modes is obtained and plotted on a Poincaré map in Fig. 4, which shows that both modes can drive the 2:1 parametric resonance when the wavenumber of the test particle k satisfies k = kq/2 and k = kb/2, respectively.

Furthermore, a chaotic phenomenon appears in the mixed modes, as indicated by the black region in Fig. 4a and d. In contrast to the characteristic “lock of the wave-number” of the parametric resonance, when chaos occurs, the wavenumber of the test particle is random, as shown in Fig. 4b and e.

PIC simulations were performed for the mixed modes, and the results are indicated in Fig. 4c and f using red dots. With a moderate space charge (μx = 0.1), the simulation results for the maximum displacements agreed with the numerical calculations.

Note that the disagreement between the simulation result and numerical calculation becomes observable in the strong space charge case, as shown in Figs. 2f and 4f. We attribute this to the disturbance of the uniform particle distribution during self-consistent particle tracking, resulting in different wavenumbers of single particles from the PCM.

Elliptical beams

In the following, we discuss the case of elliptical beams, i.e., r ≠ 1. The wavenumbers as functions of the normalized space charge tune depression μx are numerically obtained and shown in Fig. 1b, where η = 1.25 and r = 0.9. For a moderate space charge (μx = 0.1), only the quadrupole mode can induce the 2:1 resonance.

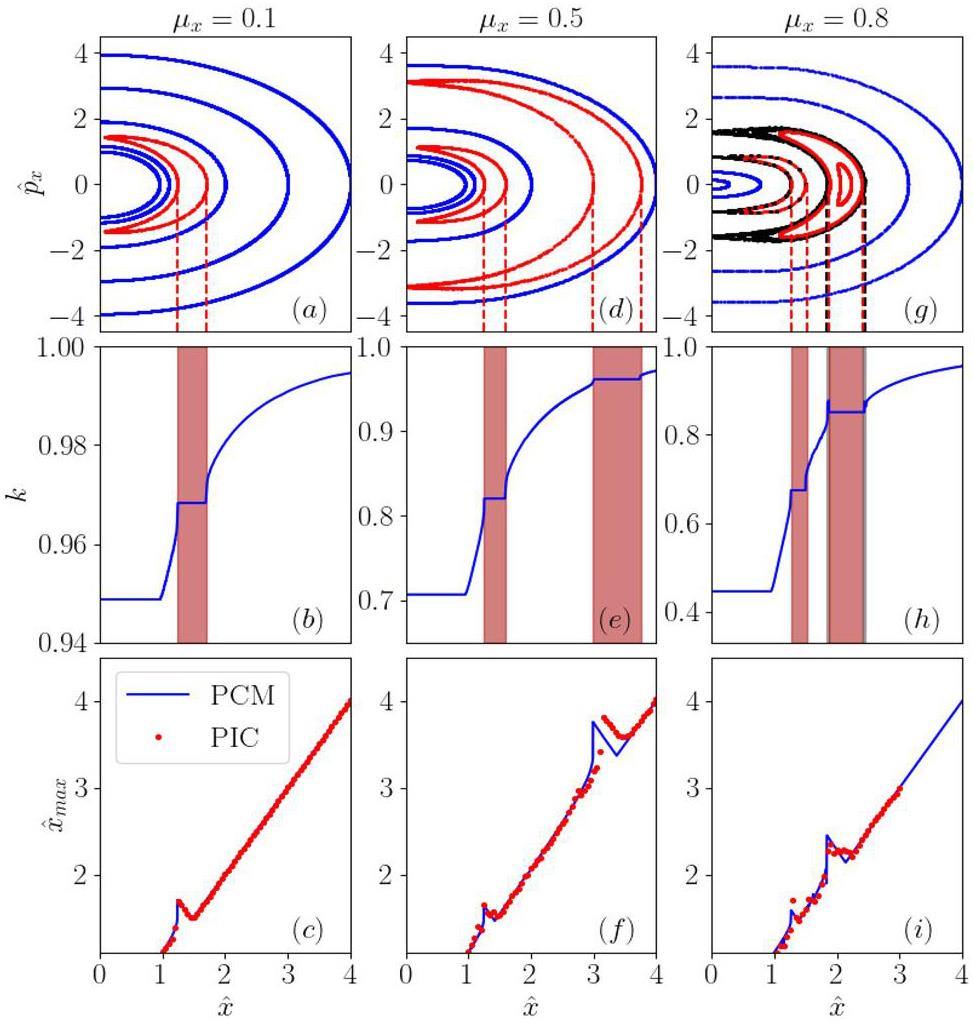

The motions of single particles affected by the space charge of the two modes in the elliptical beams are obtained and plotted on a Poincaré map in Fig. 5. The characteristic “lock of the wavenumber” is shown in Fig. 5b. For μx ≥ 0.5, two resonance islands appear, as shown in Fig. 5d and g, which are driven by the quadrupole and breathing modes, respectively. The locks of the two modes are shown in Fig. 5e and h. Furthermore, Fig. 5d and g shows that as space charge increases, the two resonance islands approach each other. With strong space charge (μx = 0.8), as shown quadrupole modes are closer to each other, which causes chaotic phenomena around the two adjacent resonant islands (shown as black dots).

PIC simulations were performed for the mixed modes in elliptical beams using the parameters listed in Table 1. The simulation results for the maximum displacements are shown in Fig. 5c, f, and i using red points. The simulation results were in good agreement with the numerical calculations.

Beam halo formation in high‑intensity synchrotrons

In this section, we investigate beam halo formation driven by the resonant interaction between single particles and the beam core in high-intensity synchrotrons, in which the combined effect of space charge and dispersion has been considered [39-43]. Hence, the conventional PCM is generalized to include dispersion. Note that the mechanism of the beam halo formation discussed here differs from space charge structural resonances, which are driven by high-order terms in the space charge potential [45-50].

Generalized PCM with dispersion

For beams traveling in a constant-focusing bending channel, the transverse beam dynamics can be described by the envelope equation set with the dispersion function, given by [2, 51]

Based on the dimensionless parameters defined in Eq. (4), the Hamiltonian in Eq. (25) can be rewritten as

We further introduce the “dispersion strength”

The dimensionless form of the dispersion-modified envelope equation set can be obtained from the Hamiltonian in Eq. (28) as follows:

However, in the presence of space charge and dispersion, the motion of a single particle is governed by

An interesting question may be raised: Can the dispersion mode excite the 2:1 parametric resonance and induce a beam halo, as in the case of the two envelope modes discussed in Sec. 3? To analyze this problem, we plot the (half) wavenumber of the dispersion mode and the two envelope modes in Fig. 6, where the corresponding parameters are Λ = 0.2, η = 1.0, R = 0.978 and Λ = 1.0, η = 1.0, R = 0.688. Figure 6 shows that the half wavenumber of the dispersion mode is always below the lower limit of the test particle, indicating that the dispersion mode cannot induce a 2:1 resonance. Moreover, by inspecting the figure, we observe k,min < kd < kp,max, implying the dispersion mode can generate a “1:1” parametric resonance on single particles.

In the following, we first demonstrate the mechanism of the 1:1 parametric resonance under the combined effect of dispersion and space charge and then show the damping effect on the beam halo formation owing to the moving stably fixed point (SFP) of single particles.

Dispersion-induced 1:1 parametric resonance

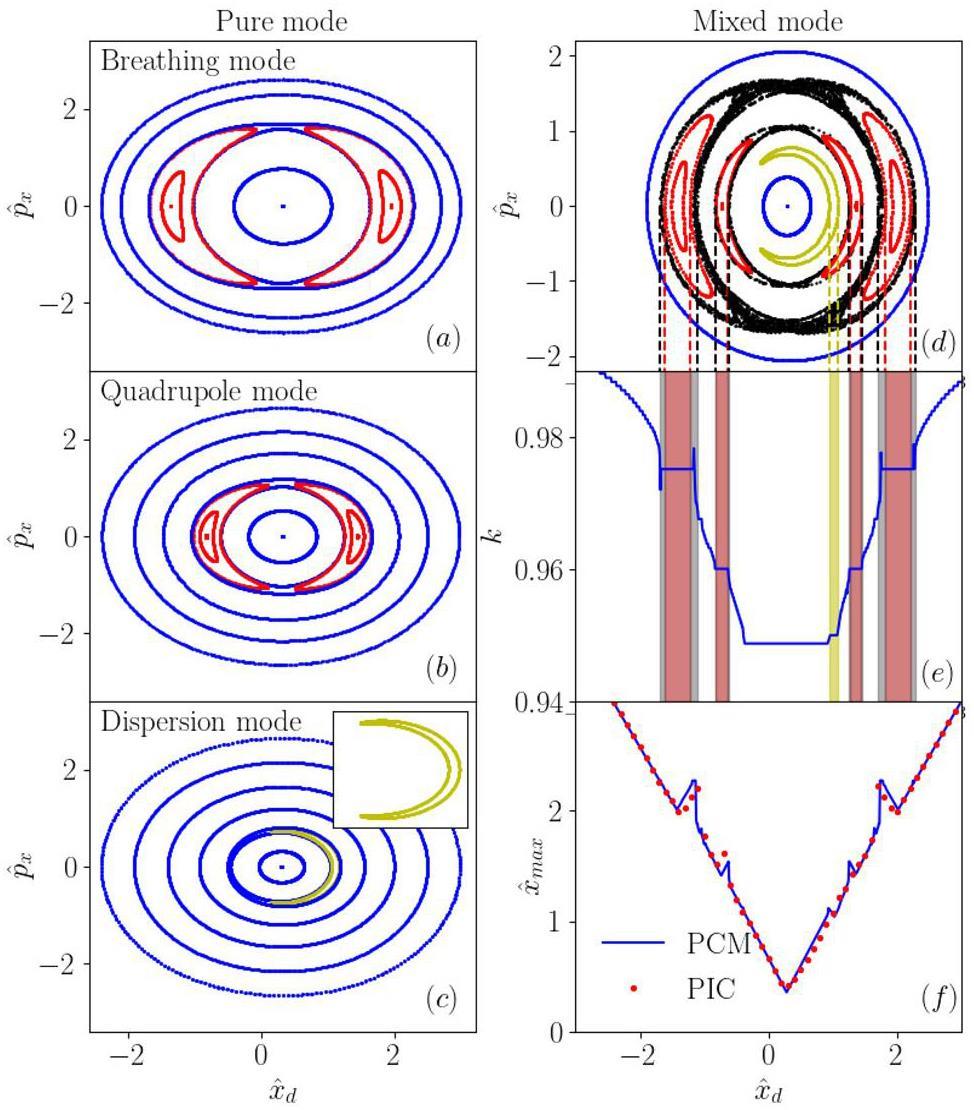

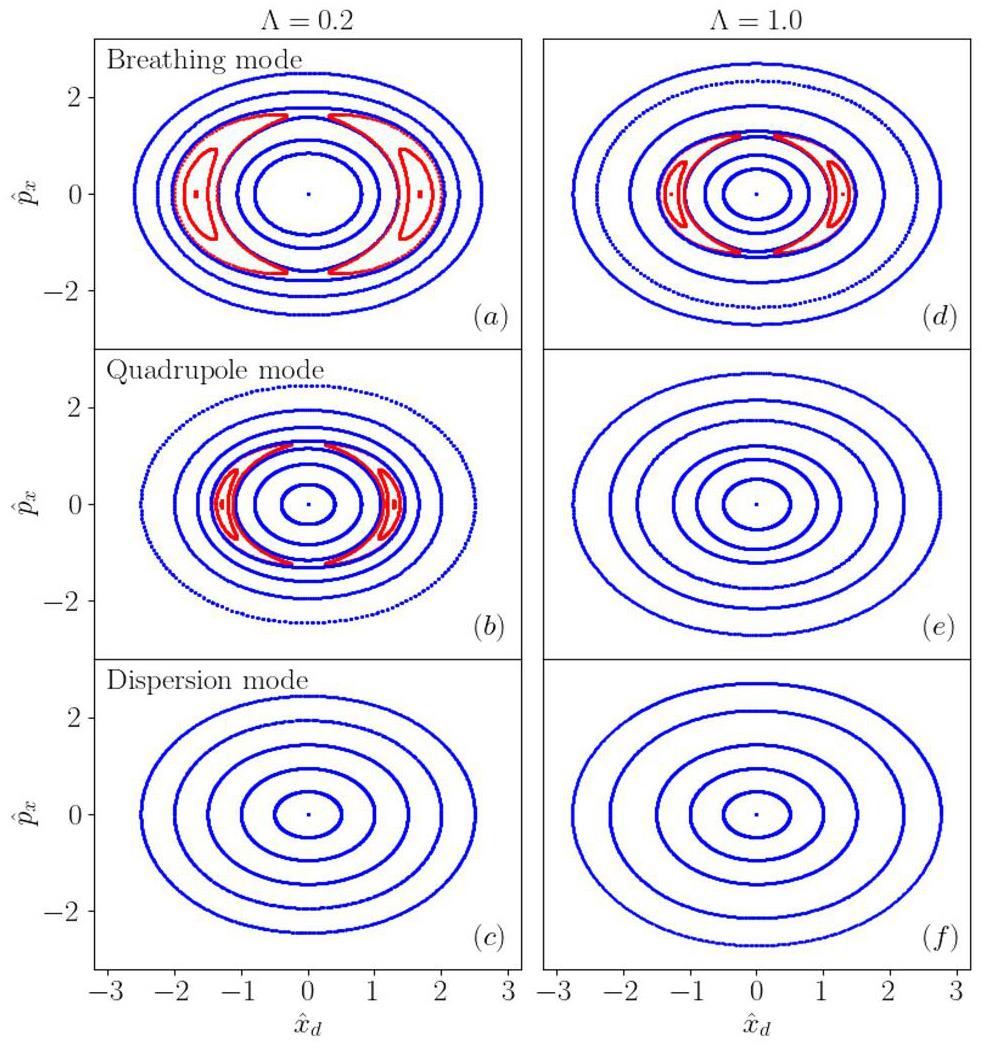

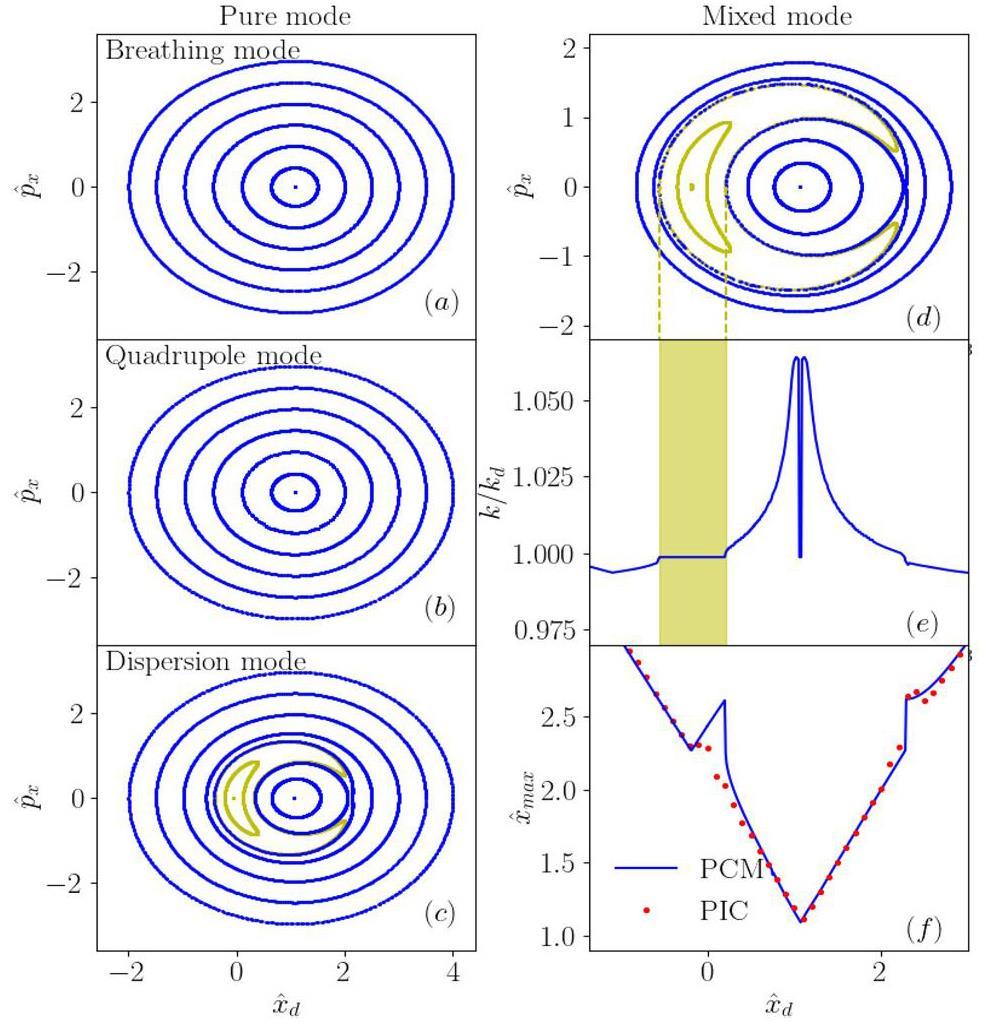

First, we consider the case of pure modes, in which only one of the breathing, quadrupole, or dispersion modes exists in the beam-core oscillation pattern. This can be achieved by setting the coefficients Dij = 0 in Eq. (35).

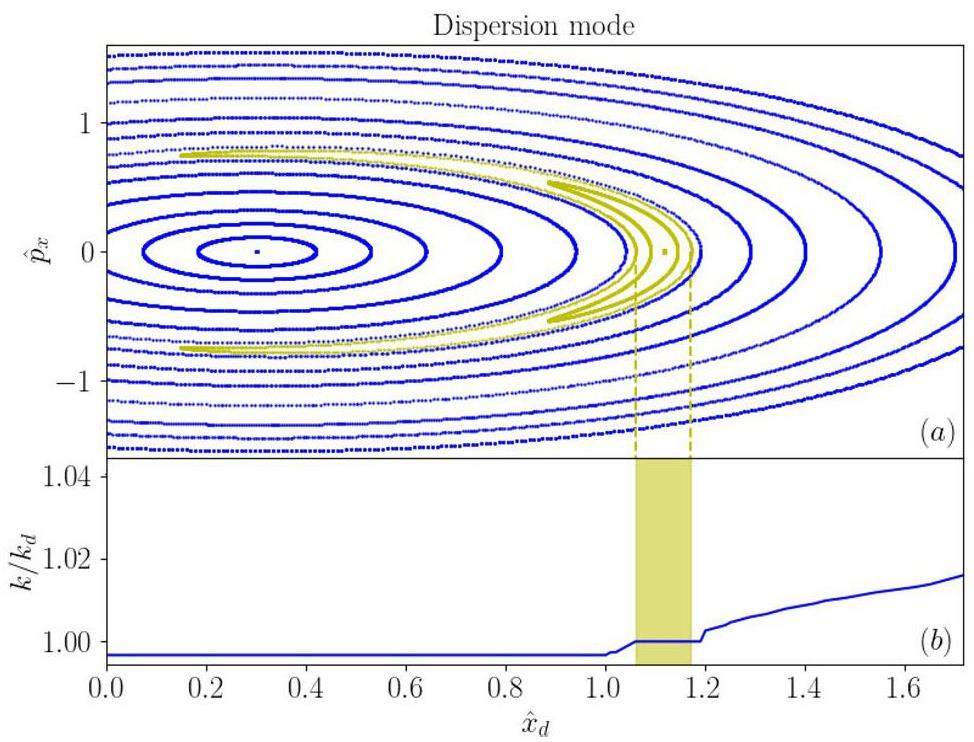

The parametric resonances for the beam halo formation in the presence of space charge and dispersion can be analyzed using the dispersion-modified PCM in Eqs. (31), (36), and (37). As shown in Fig. (7), two resonant islands are observed in panels (a) and (b), indicating the occurrence of a 2:1 resonance driven by the (pure) breathing and (pure) quadrupole modes. In the presence of the dispersion mode, a “crescent moon” island is observed, as shown in panel (c). Compared with the resonant islands in panels (a) and (b), only one island exists in panel (c), which is identified as the 1:1 resonance induced by the dispersion mode.

To better illustrate the 1:1 resonance, we plot the Poincaré section and normalized wavenumber of single particles in Fig. 8 (i.e., enlarged plot in Fig. 7(c)). We observe that in the “crescent moon” island, the wavenumber of single particle is locked and equal to wavenumber of the dispersion mode (marked as the yellow shaded area in Fig. 8(b)). This is a clear proof to support the “crescent moon” island in the Poincaré section is a 1:1 parametric resonance driven by the dispersion mode.

Next, we analyze the mixed mode, in which the breathing, quadrupole, and dispersion modes exist simultaneously. As shown in Fig. 7(d), driven by the mixed modes, the 2:1 resonance driven by the two envelope modes and the 1:1 resonance induced by the dispersion mode exist. Furthermore, chaos is observed around the resonant islands. Panel (e) presents the corresponding wavenumbers of the three modes. Similar to the results shown in Fig. 4 in Sect. 3, the locking of the wavenumbers indicates the 2:1 and 1:1 parametric resonances, which agrees with the resonant islands in panel (d). When chaos occurs, the wavenumber becomes random.

PIC simulations were conducted using the parameters of the Λ=0.2 case, as shown in Table 2. The simulation results are shown in Fig. 7(f). The simulation results of maximum displacements were in good agreement with the numerical calculations using the generalized PCM with dispersion.

| Parameters | Λ=0.2 case | Λ=1.0 case |

|---|---|---|

| Length per cell (m) | 14.2 | 14.2 |

| Phase advance in x (deg) | 108 | 108 |

| Phase advance in y (deg) | 108 | 108 |

| Bending radius (m) | 36.3 | 36.3 |

| RMS momen. spread (%) | 0.192 | 0.96 |

| RMS emit. in x (mm⋅mrad) | 30 | 30 |

| RMS emit. in y (mm⋅mrad) | 30 | 30 |

| Intensity (particle numbers) | 1.22×1010 (μx=0.1) | 2.17×1010 (μx=0.1) |

Alleviation of the beam halo using strong dispersion

Motion of single particles with zero momentum deviation

We assume single particles with zero momentum deviation for the synchronous particles (

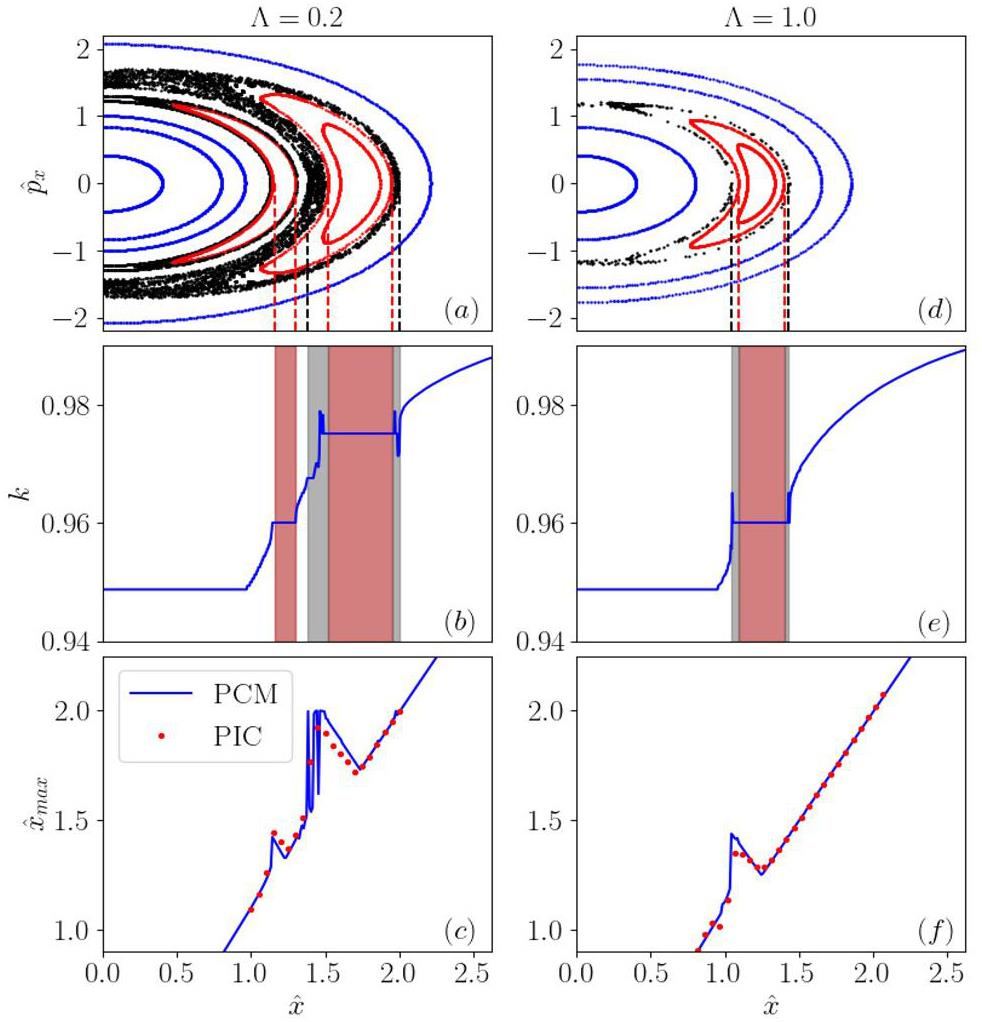

The Poincaré sections of single particles with

The Poincaré sections for the mixed mode case are shown in Fig. 10. The chaos existed around the resonance islands driven by mixed modes. Compared with Fig. 10(a), we observe the chaos in Fig. 10(d) weakens as the dispersion strength increases (Λ = 1.0). The wavenumbers of single particles with different initial positions are shown in in Fig. 10(b) and (e), where the red and gray shadows represent the resonance and chaos, respectively. PIC simulations were performed for Λ = 0.2 and Λ = 1.0 using the parameters listed in Table 2. The simulation results for the maximum displacements are shown in Fig. 10(c) and (f). The simulation results were in good agreement with the PCM calculations.

Motion of single particles with large momentum deviation

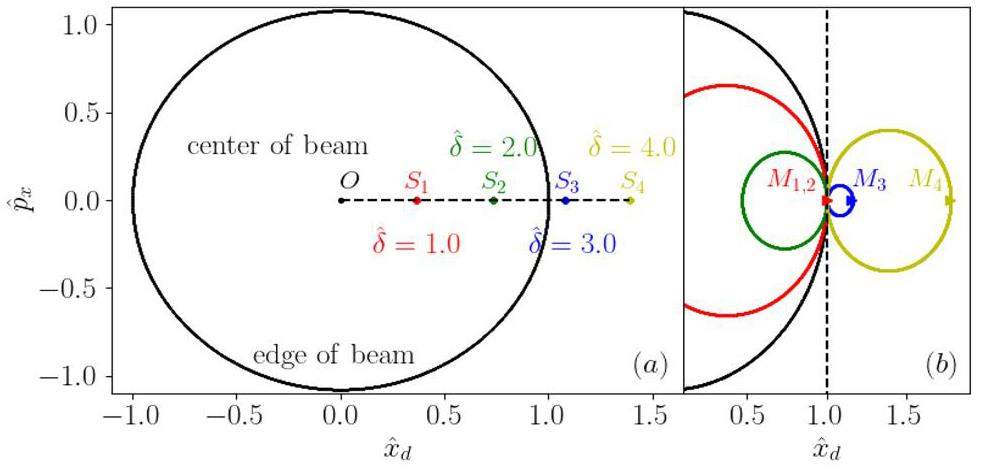

For the single particles with large momentum deviation, the SFP can “move” out of the beam core in the presence of the dispersion effect. As an example, we plot four SFPs with different momentum deviations in phase space in the panel (a) of Fig. 11. We set Λ = 1.0 for the beam core. We observe that with

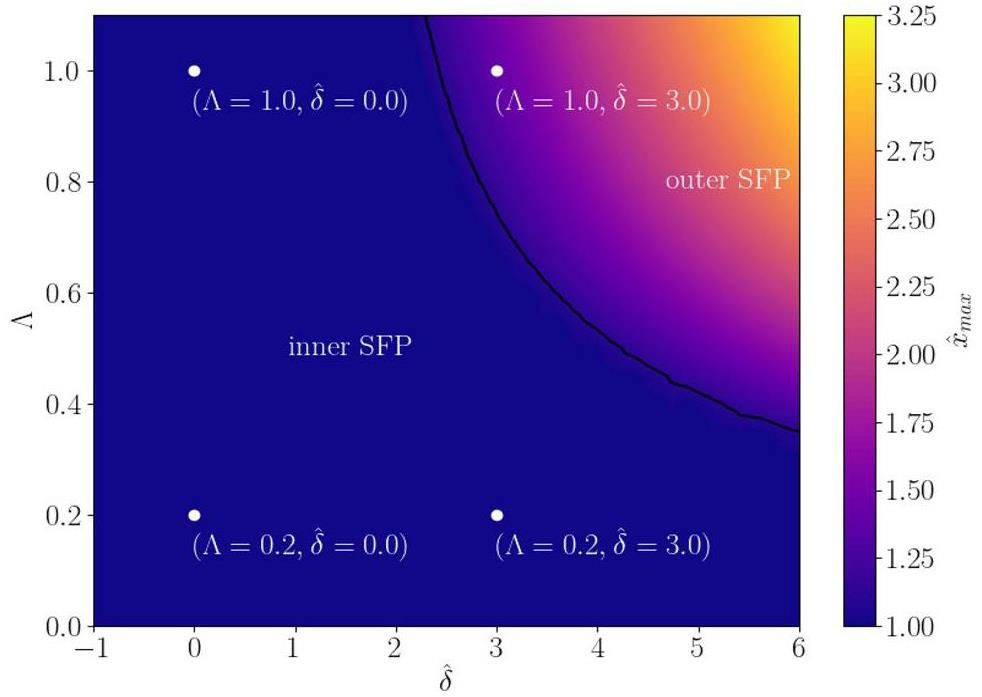

For a more illustrative discussion, the scanning of the maximum excursion of an edge particle is shown in Fig. 12. The scan is performed by varying the dispersion strength of the beam core Λ and the momentum deviation ratio of the single particle

Figure 12 shows that, for single particles with SFPs inside the beam core, the condition

PIC simulations were conducted using the parameters listed for Λ=1.0, as shown in Table 2, and the simulation results are shown in Fig. 13(f). The simulation results of the maximum displacements agreed closely with the numerical calculations based on the dispersion-modified PCM.

High-order mode in large mismatch oscillations

The analysis of the beam halo formation in the preceding sections is based on perturbation theory, where single-particle oscillations with small amplitudes are considered and high-order terms are neglected. In this section, we investigate single-particle motion driven by the mismatch oscillation of the beam core with a large amplitude, in which high-order oscillation modes are considered. An interesting question is whether these high-order oscillation modes can induce a beam halo. Note that high-order modes in the large mismatch discussed here should be distinguished from the high-order resonances of the low-order modes. For example, the 8:3 resonance shown in Fig. 2 is an eighth-order resonance driven by low-order (breathing) modes.

For simplicity, we consider a round beam travelling in a symmetrical focusing channel. In this case, the envelope equation for the beam core (Eq. (7)) can be expressed as

However, the equations of motion for single particles in Eqs. (16) and (17) can be approximated using a cubic term [22]:

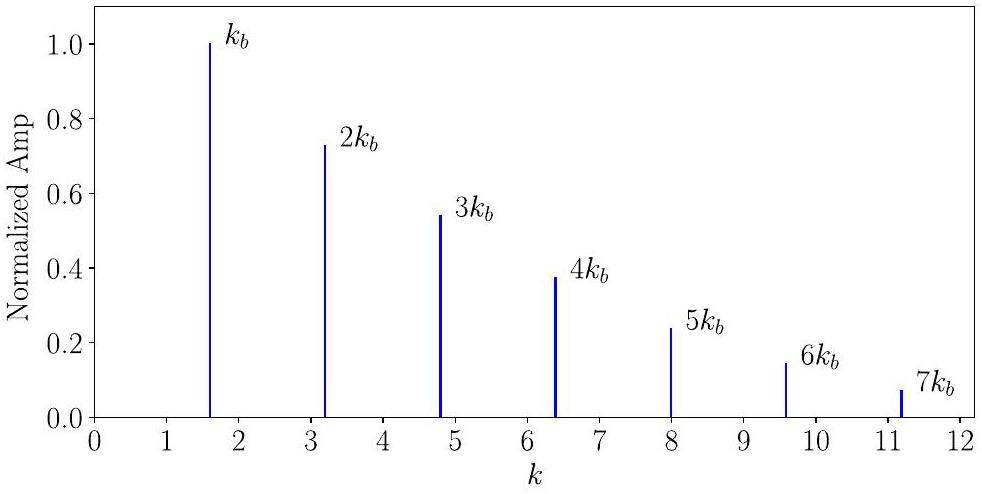

For example, we numerically solve Eq. (38) with the initial condition

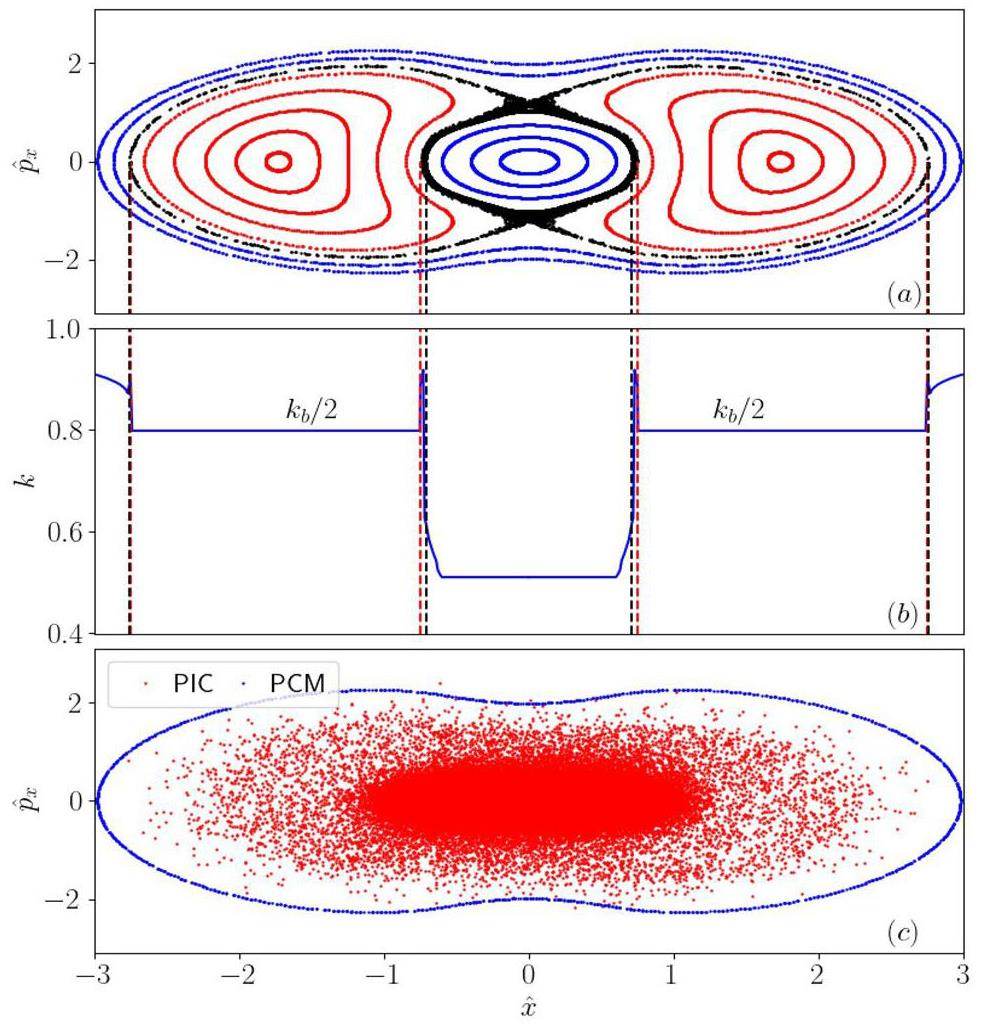

The Poincaré section and corresponding wavenumbers of single particles with different initial positions under 40% mismatch are calculated using Eqs. (38) and (40), as shown in Fig. 15(a) and (b), respectively. Within the 2:1 resonance islands, we obtain

A PIC simulation was conducted based on the parameters of the “round beam” shown in Tab. 1. In the simulation, an initial KV distribution of 200,000 macro particles was tracked for 500 turns, and the results are shown in Fig. 15(c). A “peanut” shape of the halo particle distribution was observed in the simulation result, agreeing with the contour of the Poincaré section, which was numerically calculated using Eqs. (16), (17), and (38).

Based on closer observation in Fig. 15(a), we observe the chaotic regions exist around the resonance islands (black). The physical mechanism of chaos formation can be analyzed as follows. To clarify the flow of the following text, we distinguish two types of particle-core resonances:

1. Low-order particle-core resonances driven by high-order beam oscillation modes (be proved not existing in Eq. (44));

2. High-order particle-core resonances driven by low-order beam oscillation modes.

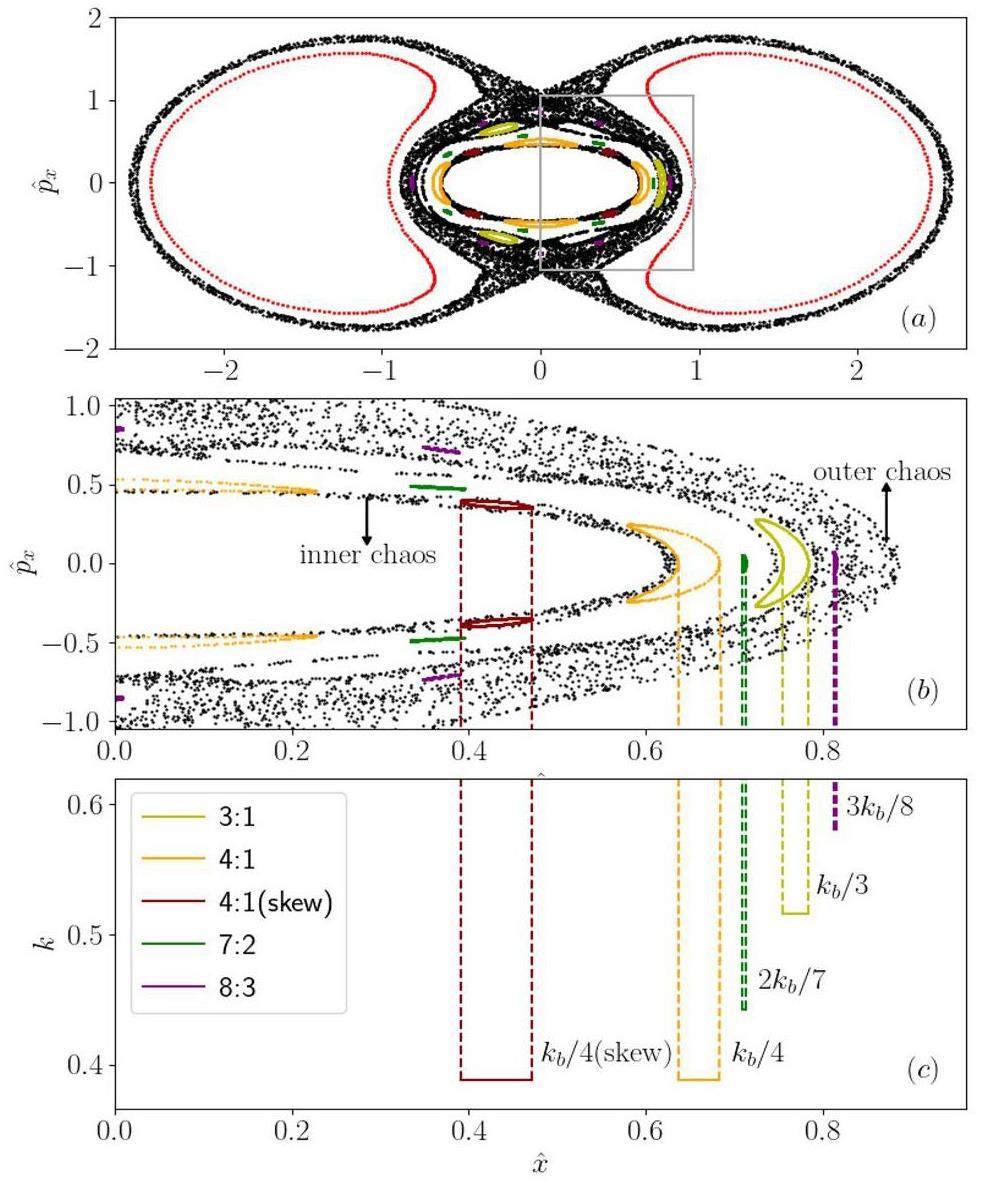

In the former case, high-order modes cannot induce low-order resonances, as discussed using Eq. (44). To analyze the latter case, we use a perturbation method with a large mismatch of 40% (

A detailed observation on Fig. 16 shows that the chaos region can be divided into inner and outer regions. The “outer chaos” is caused by the mixture of the 2:1 resonance and the higher order resonance, such as the 3:1 (yellow) and 8:3 (purple) resonances. In comparison, the “inner chaos” is closer to the beam core and much weaker. We attribute it to the fact that the inner chaos is caused by the mixture of high-order resonances, the 4:1 and the “skew” 4:1 as shown Fig. 16. The outer chaos is driven by the lowest order (2:1) resonances and is thus much stronger.

Summary

We have analyzed beam halo formation driven by the parametric resonance between single particles and the beam core in high-intensity synchrotrons. In the absence of dispersion, we observe several high-order resonances in addition to the 2:1 resonance. Moreover, chaos exists with a mixture of parametric resonances and can be weakened by the asymmetry of elliptical beams. In the presence of the combined effect of space charge and dispersion, we find that the dispersion mode can drive the 1:1 parametric resonance and discussed its physical mechanism in detail. In addition, we demonstrated that the beam halo can be alleviated by a large dispersion. For large-mismatch oscillations, we proved that higher-order modes exist; however, they are unable to drive 2:1 parametric resonance.

We expect that the 1:1 parametric resonance will have implications for the design and operation of high-intensity synchrotrons. Furthermore, the role of synchrotron motion in beam halo formation warrants further investigation.

Nonlinear resonances and chaotic behavior in a periodically focused intense charged-particle beam

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 2195 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.2195Dispersion-Induced Beam Instability in Circular Accelerators

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Envelope instability and the fourth order resonance

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams. 17,Chaotic behavior and halo development in the transverse dynamics of heavy-ion beams

. Fusion Eng. Des. 32–33, 159-167 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-3796(96)00464-4Nonlinear resonance and envelope instability of intense beam in axial symmetric periodic channel

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 813, 13-18 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.12.056Longitudinal instability caused by long drifts in the C-ADS injector-I

. Chinese Phys. C 37,Transport characteristics of space charge dominated multi-species deuterium beam in electrostatic low energy beam line

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29(4), 51 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01104-zSimulation of high-intense beam transport in electrostatic accelerating column

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 26(6),Simulation of a low energy beam transport line

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 23(2), 83-89 (2012) https://doi.org/10.13538/j.1001-8042/nst.23.83-89Half-integer resonance caused by dc injection bump magnets and superperiodicity restoration in high-intensity hadron synchrotrons

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 26,Bunched beam envelope instability in a periodic focusing channel

. J. Phys: Conf. Ser 1067,Physics design of an accelerator for an accelerator-driven subcritical system

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 16,Classification of space-charge resonances and instabilities in high-intensity linear accelerators

. J. Korean Phys. Soc 72, 1523-1530 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3938/jkps.72.1523Higher order mode beams mitigate halos in high intensity proton linacs

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 20,Beam Loss in Linacs

. arXiv:1608.02456 (2016). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1608.02456Beam loss mechanisms in high-intensity linacs

, in Proceedings of ICFA Advanced Beam Dynamics Workshop on High-Intensity and HighBrightness Hadron Beams (Beam-intensity limitations in linear accelerators

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci 28, 2408-2412 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.1981.4331708Discussion of 90 stopband in low-energy superconducting linear accelerators

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33(9), 121 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01104-zAn approach to fundamental study of beam loss minimization. Paper Presented at the AIP Conference Proceedings

. American Institute of Physics 480, 21-30 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.59501Image-charge effects on the envelope dynamics of an unbunched intense charged-particle beam

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams. 6,Particle-core model for transverse dynamics of beam halo

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 1,Beam halo studies using a three-dimensional particle-core model

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 73, 1247 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.3.064201Chaotic dynamics driven by particle-core interactions

. Phys. Plasmas 28, 09310 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0056306Three-dimensional envelope instability in periodic focusing channels

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 21,Space Charge Induced Collective Modes and Beam Halo in Periodic Channels

.Analytical treatment of particle–core interaction

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 618, 37-42 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2010.02.125Simulation on control of beam halo-chaos by power function in the hackle periodic-focusing channel

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 19(6), 325-328 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-8042(09)60012-9Particle-core analysis of beam halo formation in anisotropic beams

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 435, 284 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(99)00565-3Particle-in-cell simulation study on halo formation in anisotropic beams

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 345, 454 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(00)00474-5Particle Orbits in Quadrupole–Duodecapole Halo Suppressor

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 770, 169-176 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.09.085Rms envelope equations with space charge

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci 18, 1105-1107 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.1971.4326293Chaotic behaviour and halo formation from 2D space-charge dominated beams

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 345, 405 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(94)90490-1Halo formation and emittance growth in the transport of spherically symmetric mismatched bunched beams

. Phys. Plasmas 22,Halo formation in three-dimensional bunches

. Phys. Rev. E 58, 4977 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.58.4977Hamiltonian formalism for halo investigation in high-intensity beams

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 561, 166 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2006.01.020Analytic Model for Halo Formation in High Current Ion Linacs

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1247 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.1247Effect of space charge on linear coupling and gradient errors in high-intensity rings

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 6,Particle-core analysis of dispersion effects on beam halo formation

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 2,Coherent dispersion effects in 2D and 3D high-intensity beams

. Phys. Plasmas 30,rms Envelope Equations in the Presence of Space Charge and Dispersion

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 96 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.96Space-Charge Dominated Beams in Synchrotrons

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5133 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.5133Simulations of beam envelope dynamics in circular accelerators

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 18,Space charge induced resonance excitation in high intensity rings

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 6,Sixth-Order Resonance of High-Intensity Linear Accelerators

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114,Fourth order resonance of a high intensity linear accelerator

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 12,Structure resonances due to space charge in periodic focusing channels

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 21,Structure resonance crossing in space charge dominated beams

. Phys. Plasmas 26, 5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5061774Interplay of space-charge fourth order resonance and envelope instability

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 832, 43-50 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.06.036Space charge dynamics in high intensity rings

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 2,China’s first pulsed neutron source

. Nature Materials 15(7), 689-691 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4655China Spallation Neutron Source: Design, R&D, and outlook

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 600, 10 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2008.11.017