Introduction

The nuclear mass or binding energy reflects complex nuclear forces that bind protons and neutrons together within a nucleus [1]. This fundamental quantity not only underlies nuclear stability [2] but also critically influences astrophysical phenomena, from nuclear reactions in stellar interiors [3] to the nucleosynthesis processes responsible for elemental production in the universe [4]. Consequently, the precise determination of nuclear masses is indispensable for advancing our understanding of nuclear structures [5] and has significant implications for nuclear astrophysics [6-8]. Thus, improved experimental precision and theoretical accuracy in nuclear mass evaluations not only deepens insights into fundamental research in nuclear physics [9] but also fosters progress in nuclear energy applications via both fusion and fission.

Global investments in rare isotope beam facilities–including the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL) [10] and the High Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF) at Huizhou [11], China, the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) in the USA [12], the Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory (RIBF) at RIKEN, Japan [13], the Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR) in Germany [14], the Rare isotope Accelerator complex for ON-line experiments (RAON) in Korea [15], and Isotope Separator and Accelerator in Canada (ISAC) [16]–have substantially advanced the production, identification, and investigation of nuclides far from the valley of stability. To date, experimental efforts have led to the identification of over 3300 nuclides [17], with mass measurements available for approximately 2500 of these [18-20]. By contrast, theoretical models predict the existence of approximately 7000–10000 nuclides [21, 22]. Given that the proton dripline has been established for isotopes with proton numbers

Extensive efforts have been devoted to reproducing measured nuclear masses and predicting those that are yet uncharted. Macroscopic-microscopic approaches exemplified by the finite-range droplet model (FRDM) [25] and the Weizsäcker-Skyrme (WS) model [26, 27] have achieved impressive accuracy in describing existing mass data; however, microscopic theories are widely accepted as offering superior predictive capabilities [28, 29]. In this context, density functional theory has emerged as a powerful framework for a unified description of nearly all nuclides across the nuclear chart [30-38]. Its relativistic extension, the covariant density functional theory (CDFT) [39], has been exceptionally successful in describing a variety of nuclear phenomena in both ground and excited states [39-48]. This success is largely attributable to the inherent advantages of CDFT, including the automatic incorporation of spin-orbit coupling [49, 50], natural explanation of pseudospin symmetry in the nucleon spectrum [51-53], spin symmetry in the antinucleon spectrum [53-55], and self-consistent treatment of nuclear magnetism [56, 57].

Within the framework of CDFT, the pairing correlations and continuum effects are taken into account self-consistently in the relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov (RCHB) theory [58, 59], making it capable of describing both stable and exotic nuclei [58, 60-65]. A pioneering application of RCHB theory is the construction of the first relativistic nuclear mass table incorporating continuum effects, in which the existence of 9035 bound nuclei with

Thus, it is natural to propose an upgraded mass table that incorporates not only continuum effects but also nuclear deformation degrees of freedom. This can be realized by employing the deformed extension of the RCHB theory, that is, the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum (DRHBc) [66-69]. Axial deformation, pairing correlations, and continuum effects are considered microscopically and self-consistently in the DRHBc theory, which lays an important foundation for its great success [45, 70, 71]. In pursuit of a high-precision mass table [72], a point-coupling version of the DRHBc theory was developed [73, 74] for combination with the density functional PC-PK1 [75], which is probably the most successful density functional for describing nuclear masses [37, 44, 76]. The DRHBc mass table project, now in progress for over six years, has successfully completed the sectors for even-even [77] and even-Z [78] nuclei. Impressively, the root-mean-square (RMS) deviation of the DRHBc calculated masses from the latest Atomic Mass Evaluation (AME2020) data is approximately 1.5 MeV, positioning it among the most accurate density-functional descriptions for nuclear masses. Moreover, lots of relevant studies on halo phenomena [79-89], nuclear charge radii [90-92], shape evolution [93-96], shell structure [97-103], decay properties [104-107], and other topics [108-113] based on the DRHBc mass table underscore its value as a resource that extends far beyond a mere data repository [114].

In this work, inspired by the recent progress in nuclear mass measurements that provide new data beyond AME2020 or reduce the uncertainties of existing data, we further examined the predictive power of the DRHBc mass table using the new mass data. On the theoretical side, a new point-coupling density functional, PC-L3R, has recently been proposed, whose performance is even better than that of PC-PK1 in describing the masses of spherical nuclei [115]. Our second motivation is to test the accuracy of PC-L3R in describing the masses of deformed nuclei when combined with DRHBc theory. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The point-coupling DRHBc theory, relativistic density functionals PC-PK1 and PC-L3R, and numerical details are introduced in Sect. 2. DRHBc descriptions with PC-PK1 and PC-L3R for the new masses are presented and compared with those from other density functionals in Sect. 3. Finally, a summary is given in Sect. 4.

Theoretical framework

The point-coupling density functional theory starts from the Lagrangian density,

| Coupling constant | PC-PK1 | PC-L3R |

|---|---|---|

| αS (MeV-2) | -3.96291×10-4 | -3.99289×10-4 |

| βS (MeV-5) | 8.6653×10-11 | 8.65504×10-11 |

| γS (MeV-8) | -3.80724×10-17 | -3.83950×10-17 |

| δS (MeV-4) | -1.09108×10-10 | -1.20749×10-10 |

| αV (MeV-2) | 2.6904×10-4 | 2.71991×10-4 |

| γV (MeV-8) | -3.64219×10-18 | -3.72107×10-18 |

| δV (MeV-4) | -4.32619×10-10 | -4.26653×10-10 |

| δTV (MeV-2) | 2.95018×10-5 | 2.96688×10-5 |

| δTV (MeV-4) | -4.11112×10-10 | -4.65682×10-10 |

Starting from the Lagrangian density (1), the Hamiltonian can be derived via the quantization of the Dirac spinor field in the Bogoliubov quasiparticle space, and the energy functional can be constructed as its expectation with respect to the Bogoliubov ground state. The relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov equation obtained by performing the variation of the energy density functional with respect to the generalized density matrix and neglecting the exchange terms reads

The calculations in this study were performed using the same numerical details as those used to construct the DRHBc mass table [73, 74, 77]. Specifically, the pairing strength V0=-325 MeV fm3, saturation density ρsat = 0.152 fm-3, and pairing window was set to 100 MeV. The Dirac Woods-Saxon basis space was determined by an energy cutoff of

Results and discussion

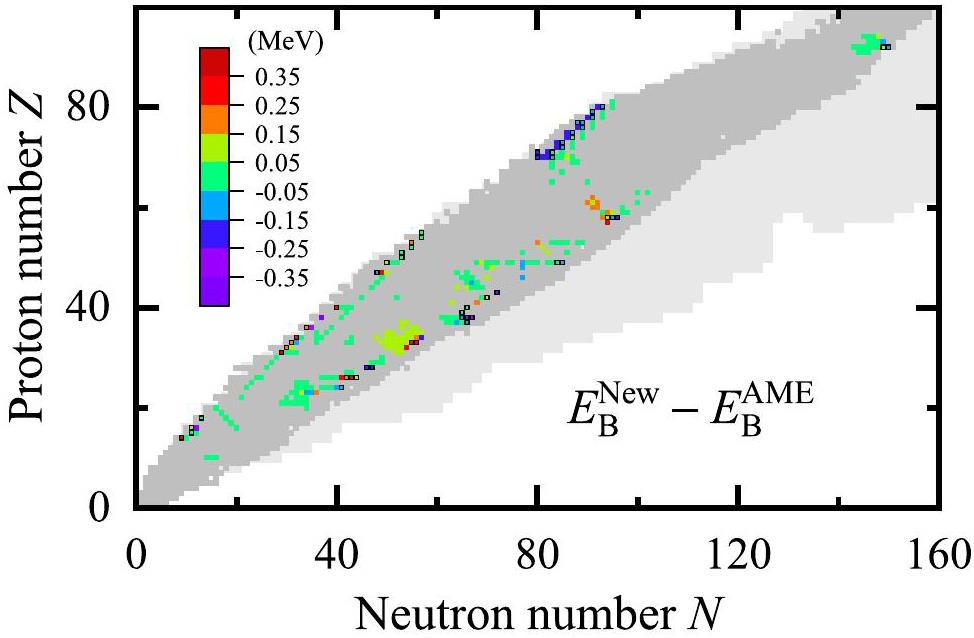

We have collected the newly measured masses of 296 nuclides from 40 references [120-159], published between 2021 and 2024 (subsequent to the release of AME2020) and summarized in Table 2. The sources and measurement methods for the new experimental data are presented in Table 3. The corresponding mass values in AME2020, which contained 241 experimentally measured values and 55 extrapolated empirical values (labeled #), are listed in Table 2 for comparison. The differences between the new data and the AME2020 values are also given in Table 2 and are scaled by colors in Fig. 1. The nuclides with only empirical values in AME2020 are highlighted by black squares in Fig. 1. Among these 296 mass data, 247 in AME2020 are consistent with new measurements with deviations smaller than 0.15 MeV. The RMS deviation between the new and AME2020 experimental data is σ=0.0984 MeV, and after including the empirical values in AME2020, σ becomes 0.1178 MeV.

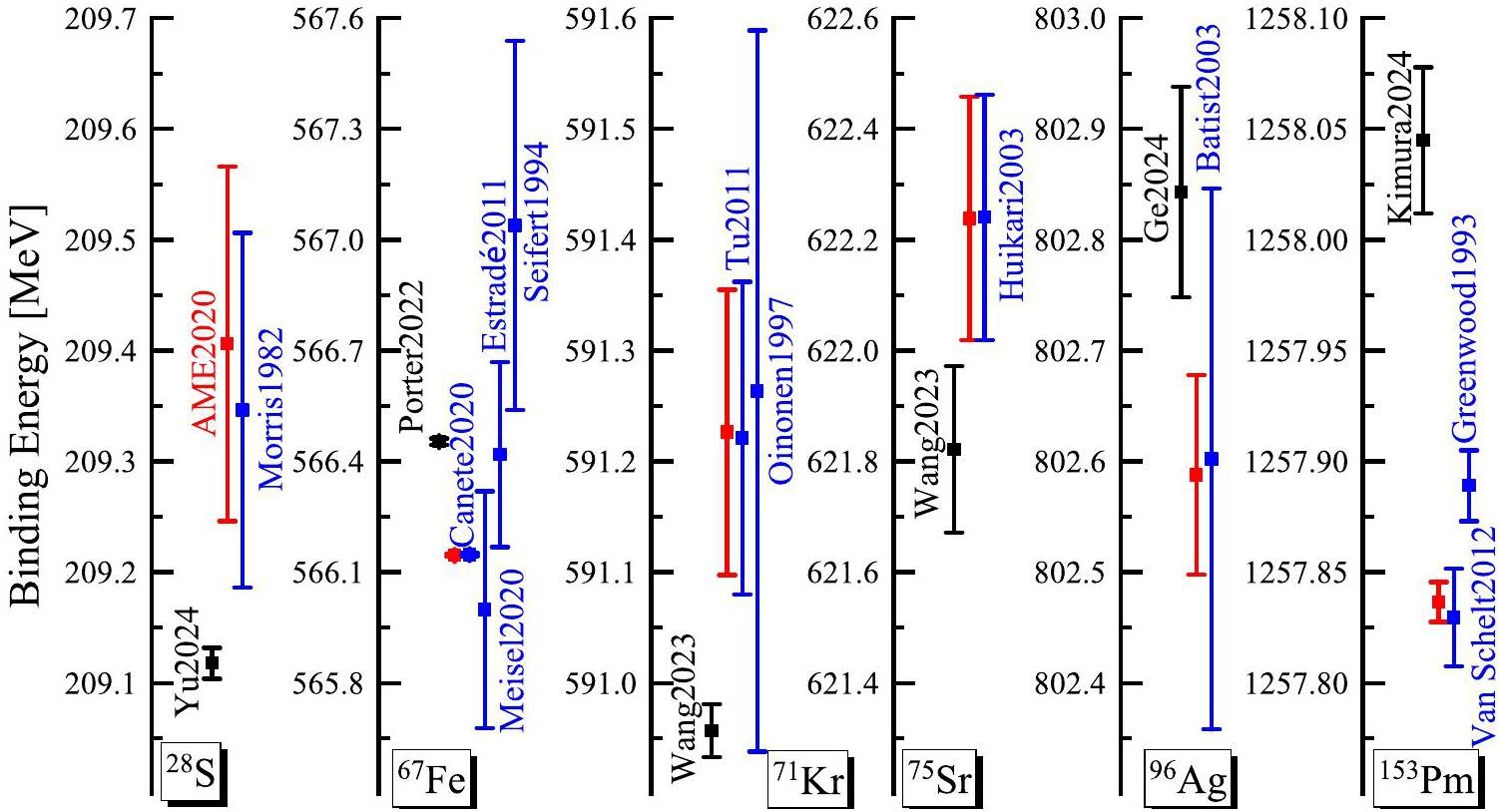

Most of the deviations between the new and AME2020 experimental data lie within experimental uncertainties. Nevertheless, even after considering the experimental uncertainties, disagreement still arises for 73 nuclides, which are labeled in bold in Table 2. Among these 73 data, the smallest difference, 0.00055 MeV, occurs between the upper bound of the new data and the lower bound of the AME2020 data for 111Ag, while the largest one, 0.29516 MeV, occurs between the lower bound of the new data and the upper bound of the AME2020 data for 67Fe. It is important to note that newly measured masses are not necessarily more accurate than those in previous evaluations. Systematic biases or experimental uncertainties may affect the measured values depending on the specific setup and techniques employed. Notably, for 23 nuclides, the central values of the newly reported masses deviated from those in AME2020 by more than 200 keV. Among the 23 nuclides exhibiting discrepancies exceeding 200 keV, 12 cases (23Si, 74Ni, 86Ge, 89As, 91Se, 70Kr, 104Sr, 105Sr, 109Nb, 72Tc, 151La, and 151Yb) show overlapping uncertainty ranges between the new measurements and AME2020 values, indicating potential consistency within experimental uncertainties. For 5 nuclides (69Fe, 60Ga, 88As, 66Se, and 80Zr), while the central value discrepancies also exceed 200 keV and uncertainty ranges do not overlap, the AME2020 masses are extrapolated values. Although such empirical estimates, based on trends in the mass surface and available experimental constraints, are often validated by subsequent measurements, deviations from true mass values may arise, for example, for nuclides exhibiting abrupt changes in shell structure. Finally, for 6 nuclides (28S, 67Fe, 71Kr, 75Sr, 96Ag, and 153Pm), the central values differ by more than 200 keV, the uncertainty ranges do not overlap, and both the new and AME2020 masses are based on experimental data. The cases are compared in Fig. 2, along with earlier measurements referenced in AME2020. The observed discrepancies may arise from differences in the measurement techniques. For 28S, its mass was derived from an indirect measurement in 1982 [160], whereas a recent result was obtained from a direct measurement using

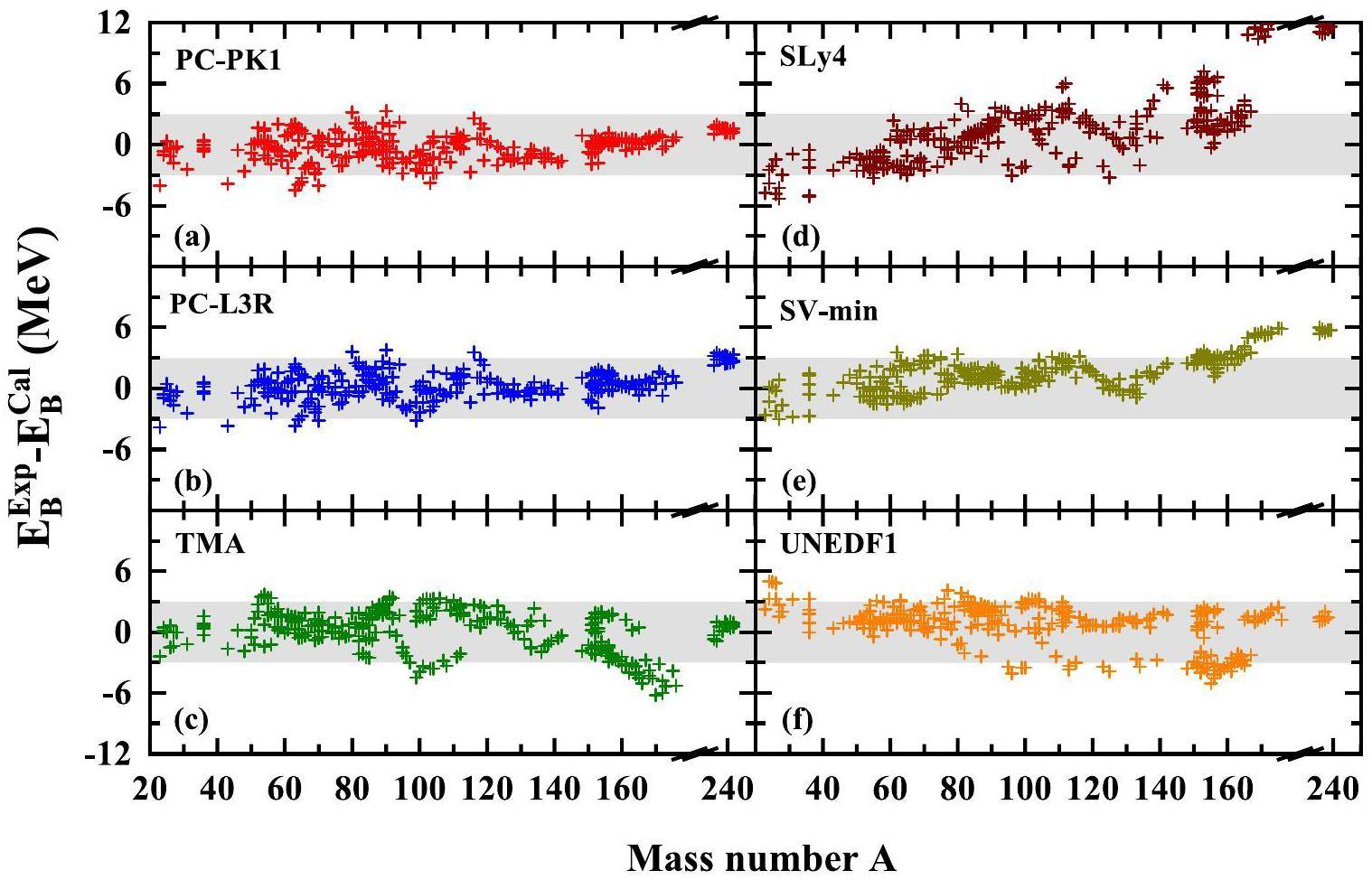

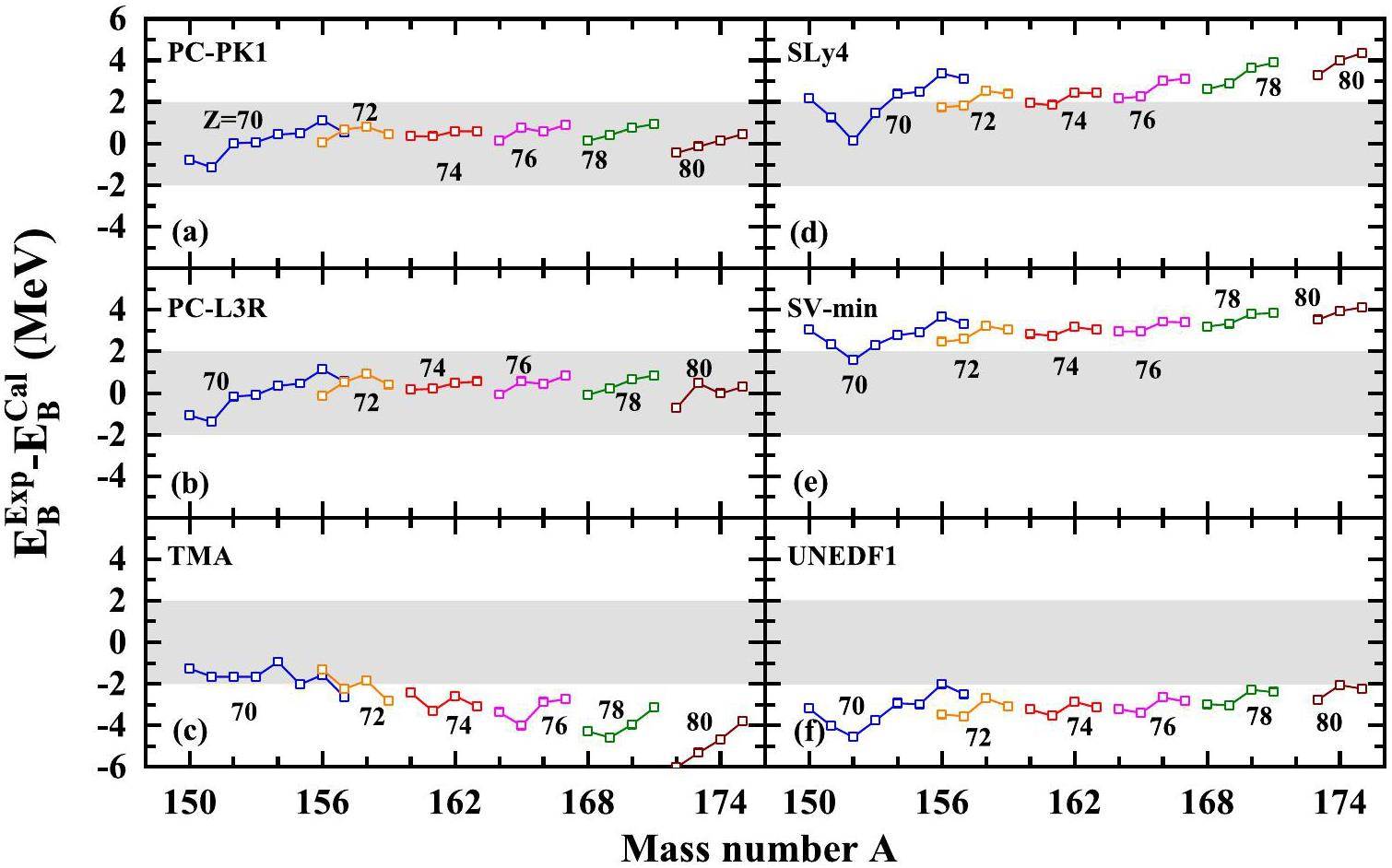

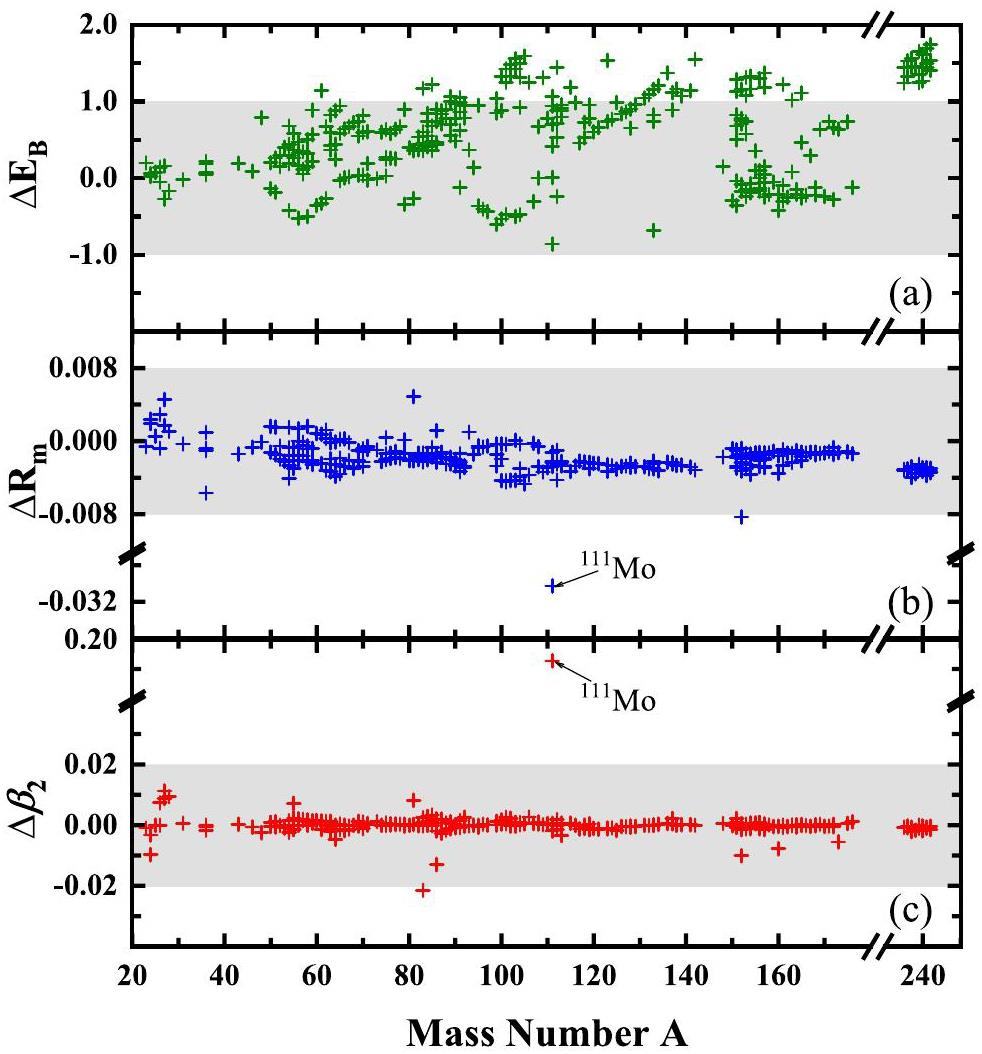

The DRHBc calculations for the 296 nuclides were performed with the density functionals PC-PK1 [75] and PC-L3R [115], and the deviations of the resulting nuclear masses from the experimental data are plotted in Figs. 3(a) and 3(b). For comparison, we also show the mass differences between the new data and the results from the relativistic mean-field plus Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (RMF+BCS) calculations with TMA [32] and the non-relativistic Skyrme Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov (HFB) calculations [171] with SLy4 [172], SV-min [173], and UNEDF1 [174], respectively, in Figs. 3(c)–(f), respectively. It can be seen that both the DRHBc calculations with PC-PK1 and PC-L3R reproduce the data fairly well within a deviation of 3 MeV, despite a few exceptions. The RMF+BCS calculations with TMA can achieve a similar level of accuracy for nuclides with A<150, but for heavier nuclides, an overestimation of up to 6 MeV arises. In contrast, the Skyrme HFB calculations with SLy4 significantly underestimated the data in the heavy-mass region, with deviations for several nuclides above 10 MeV. The results from the Skyrme HFB calculations with SV-min also exhibited a certain underestimation in the heavy mass region. Although the Skyrme HFB results with UNEDF1 improve the description in

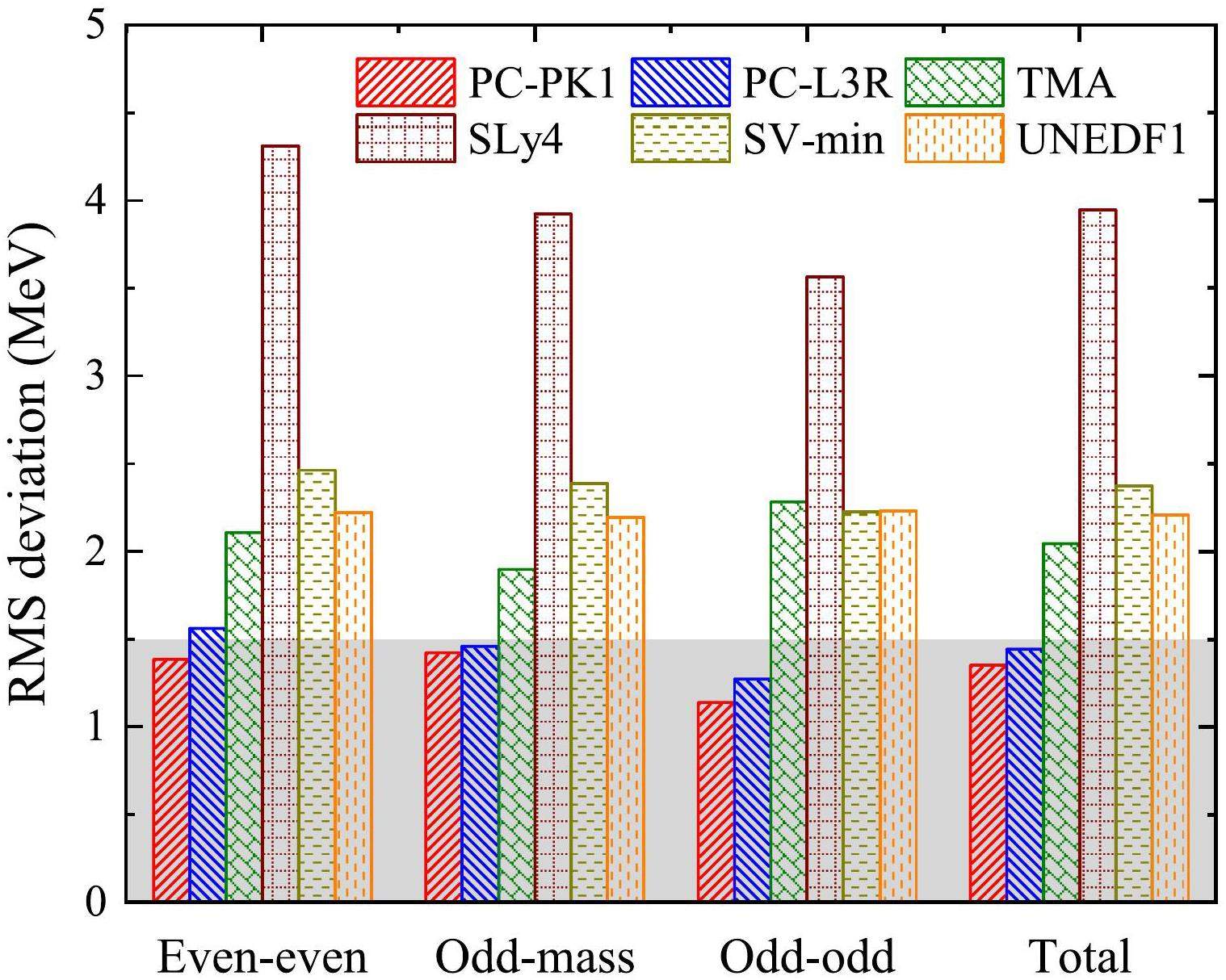

For further comparison, we show in Fig. 4 the RMS deviations between the 296 new mass data points and the above theoretical results. The RMS deviations for even-even, odd-mass, and odd-odd nuclei are also computed and presented separately in Fig. 4. It can be found that both the DRHBc descriptions with PC-PK1 and PC-L3R can achieve accuracies better than 1.5 MeV for all datasets, with the exception of DRHBc+PC-L3R for even-even nuclei. In contrast, the accuracies in the other four density functional descriptions were generally worse than 2 MeV. Overall, the odd-even effects on the accuracy are not very significant in the DRHBc results, with a slightly better description for odd-odd nuclei. However, this is not the case for the RMF+BCS description, which obviously deteriorates for odd-odd nuclei. Furthermore, DRHBc descriptions with PC-PK1 and PC-L3R for odd nuclei are expected to be improved by strictly incorporating nuclear magnetism [87]. Instead of self-consistent calculations, Skyrme HFB results for odd nuclei were obtained from interpolations using the masses and average pairing gaps of neighboring even-even nuclei [171]. As expected, the Skyrme HFB descriptions with SV-min and UNEDF1 showed marginal odd-even differences. In contrast, it seems strange that from even-even to odd-mass, and then to odd-odd nuclei, the SLy4 description gradually improves. It should also be noted that the number of mass data points here is not large enough to confirm whether the odd-even features observed in these theoretical results are common across the nuclear chart. Finally, the accuracies in describing the 296 new masses–1.35, 2.04, 3.95, 2.37, and 2.21 MeV for PC-PK1, TMA, SLy4, SV-min, and UNEDF1, respectively–are found to be generally consistent with those obtained for all available masses of even-Z nuclei: 1.43 MeV for PC-PK1, 2.06 MeV for TMA, 5.28 MeV for SLy4, 3.39 MeV for SV-min, and 1.93 MeV for UNEDF1 [78]. Moreover, even within the spherical RHB framework, PC-PK1 and PC-L3R are the only two relativistic density functionals that reproduce the experimental masses with RMS deviations below 8 MeV [22, 175]. Given the superiority of PC-PK1 and PC-L3R, a complete DRHBc mass table including both even-Z and odd-Z nuclei is desirable in the near future, and further large-scale DRHBc+PC-L3R calculations are worth pursuing.

One can see from Fig. 3 that the superiority of PC-PK1 and PC-L3R is mainly due to the better description of nuclei with A>150 compared to other density functionals. Therefore, a detailed comparison of the isospin dependence of nuclear masses in this region is necessary. In Fig. 5, the mass differences between the theoretical and experimental values are presented for even-Z nuclei with

For a quantitative comparison, the differences between the DRHBc results for PC-PK1 and PC-L3R for binding energies

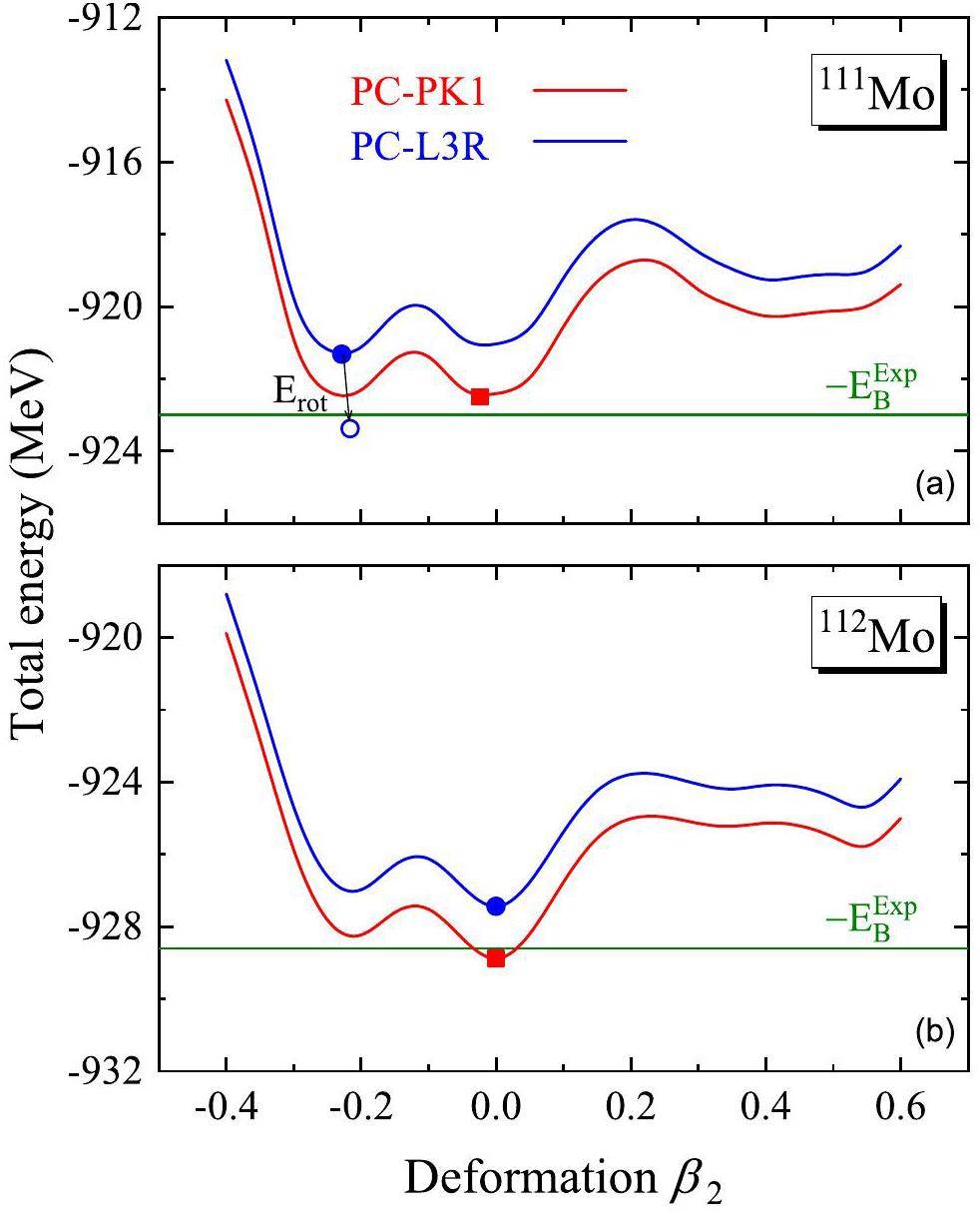

To understand the large deviations between the PC-PK1 and PC-L3R results for 111Mo, in Fig. 7, the potential energy curves (PECs) of 111Mo from the constrained calculations with PC-PK1 and PC-L3R are shown. For comparison, the corresponding results for the neighboring isotope 112Mo are also shown. The ground state is shown with the filled square (circle) from the calculations with PC-PK1 (PC-L3R). As demonstrated in Refs. [73-75], for PC-PK1, the rotational correction plays an important role in improving the mass description of the deformed nuclei. Therefore, the ground state, after including the rotational correction energy Erot is also presented with an open symbol. Considering that the cranking approximation adopted to calculate Erot in Eqs. (14) is not suitable for spherical and weakly deformed nuclei, we only calculate Erot when |β2|>0.05 and take it as zero when |β2|<0.05. A more appropriate treatment for the correction energies in the nuclei with |β2|<0.05 can be achieved using the collective Hamiltonian method [176] in future work.

For 111Mo in Fig. 7(a), in both PECs from the calculations with PC-PK1 and PC-L3R, there are three minima, that is, one near-spherical minimum and two well-deformed minima. In each curve, the difference between the oblate and near-spherical minima is within 0.25 MeV, whereas the excitation energy of the prolate minimum is approximately 2 MeV. The ground state from the PC-PK1 calculations is the near-spherical minimum with β2=-0.024, whereas the ground state from the PC-L3R calculations is the oblate minimum with β2=-0.216. This corresponds to the large

For 112Mo, the shape of the PEC is similar to that for 111Mo, still exhibiting three minima. However, here the ground states from both PC-PK1 and PC-L3R are the spherical minima, while the excitation energies of the oblate and prolate minima are about 0.5 and 3 MeV, respectively. In both results from PC-PK1 and PC-L3R, the significant differences in deformations and the small differences in total energies indicate the shape coexistence in 111,112Mo.

Summary

In this study, the newly measured masses for 296 nuclides from 40 references published between 2021 and 2024, subsequent to the release of the latest Atomic Mass Evaluation, were compiled. Although most of the new data are consistent with AME2020, for 73 nuclides, the deviations exceed the uncertainties. The new masses were calculated using the DRHBc theory with the PC-PK1 and PC-L3R density functionals and compared with the results from RMF+BCS calculations with TMA and Skyrme HFB calculations with SLy4, SV-min, and UNEDF1. The DRHBc calculations with both PC-PK1 and PC-L3R reproduce the data fairly well, with an RMS deviation below 1.5 MeV, demonstrating a clear advantage over other models in mass predictions. Taking the even-Z nuclei with

These results strengthen confidence in the DRHBc predictions of nuclear masses. Continued progress would benefit from additional experimental mass measurements and establishment of a complete DRHBc mass table with PC-PK1. Moreover, large-scale DRHBc calculations using PC-L3R are highly promising. To further improve the mass description, the inclusion of triaxial deformation, rigorous treatment of nuclear magnetism, and beyond-mean-field extensions such as collective Hamiltonian approaches are being pursued within the DRHBc framework.

Masses of exotic calcium isotopes pin down nuclear forces

. Nature 498, 346-349 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12226Direct mapping of nuclear shell effects in the heaviest elements

. Science 337, 1207-1210 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1225636Energy production in stars

. Phys. Rev. 55, 434-456 (1939). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.55.434Synthesis of the elements in stars

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 29, 547-650 (1957). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.29.547Recent trends in the determination of nuclear masses

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 1021-1082 (2003).Nuclear structure aspects in nuclear astrophysics

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 54, 535-613 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2004.09.002Nuclear masses in astrophysics

. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 349-350, 181-186 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2013.03.016The impact of individual nuclear properties on r-process nucleosynthesis

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 86, 86-126 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2015.09.001Physics opportunities of the nuclear excitation by electron capture process

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 146 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01717-0Present status of HIRFL complex in Lanzhou

. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1401,Status of the high-intensity heavy-ion accelerator facility in China

. AAPPS Bulletin 32, 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-022-00064-1Long-awaited accelerator ready to explore origins of elements

. Nature 605, 201-203 (2022).Nuclear physics with RI Beam Factory

. Front. Phys. 13,All the fun of the FAIR: fundamental physics at the facility for antiproton and ion research

. Phys. Scr. 94,Overview of the Rare isotope Accelerator complex for ON-line experiments (RAON) project

. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2586,Physics with reaccelerated radioactive beams at TRIUMF-ISAC

. J. Phys. G 38,The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear physics properties

. Chin. Phys. C 45,The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (I). Evaluation of input data, and adjustment procedures

. Chin. Phys. C 45,The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references

. Chin. Phys. C 45,The limits of the nuclear landscape

. Nature 486, 509 (2012).The limits of the nuclear landscape explored by the relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 121-122, 1-215 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2017.09.001New isotope 220Np: Probing the robustness of the N=126 shell closure in neptunium

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Location of the neutron dripline at fluorine and neon

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations: FRDM(2012)

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 109-110, 1-204 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.10.002Surface diffuseness correction in global mass formula

. Phys. Lett. B 734, 215-219 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2014.05.049Properties of the drip-line nucleus and mass relation of mirror nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01633-9Predictive power for superheavy nuclear mass and possible stability beyond the neutron drip line in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Odd-even differences in the stability peninsula in the 106≤Z≤112 region with the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 110,A systematic study of even-even nuclei up to the drip lines within the relativistic mean field framework

. Nucl. Phys. A 616, 438-445 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)00115-2Ground-sate properties of even-even nuclei in the relativistic mean-field theory

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 71, 1-40 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.1998.0795Masses, deformations and charge radii-nuclear ground-state properties in the relativistic mean field model

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 113, 785-800 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.113.785Skyrme-Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov nuclear mass formulas: Crossing the 0.6 MeV accuracy threshold with microscopically deduced pairing

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,First Gogny-Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov nuclear mass model

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,Nuclear landscape in covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Lett. B 726, 680-684 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.09.017Global performance of covariant energy density functionals: Ground state observables of even-even nuclei and the estimate of theoretical uncertainties

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Global study of beyond-mean-field correlation energies in covariant energy density functional theory using a collective Hamiltonian method

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Nuclear landscape in a mapped collective Hamiltonian from covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Relativistic mean field theory in finite nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 37, 193-263 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6410(96)00054-3Relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory: Static and dynamic aspects of exotic nuclear structure

. Phys. Rep. 409, 101-259 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2004.10.001Relativistic continuum Hartree Bogoliubov theory for ground state properties of exotic nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 57, 470-563 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2005.06.001Relativistic nuclear energy density functionals: Mean-field and beyond

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 66, 519-548 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2011.01.055Progress on tilted axis cranking covariant density functional theory for nuclear magnetic and antimagnetic rotation

. Front. Phys. 8, 55-79 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-013-0287-yHalos in medium-heavy and heavy nuclei with covariant density functional theory in continuum

. J. Phys. G 42,Multidimensionally constrained covariant density functional theories nuclear shapes and potential energy surfaces

. Phys. Scr. 91,Towards an ab initio covariant density functional theory for nuclear structure

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 109,Relativistic density functional theory in nuclear physics

. AAPPS Bulletin 31, 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-021-00001-8Relativistic field theory of superfluidity in nuclei

. Z. Phys. A 339, 23-35 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01282930Toward a bridge between relativistic and nonrelativistic density functional theories for nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Pseudospin as a relativistic symmetry

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 436-439 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.436Pseudospin symmetry in relativistic mean field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 58, R628-R631 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.R628Hidden pseudospin and spin symmetries and their origins in atomic nuclei

. Phys. Rep. 570, 1-84 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2014.12.005Spin symmetry in the antinucleon spectrum

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91,Test of spin symmetry in anti-nucleon spectra

. Eur. Phys. J. A 28, 265-269 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2006-10066-0A relativistic description of rotating nuclei: the yrast line of 20Ne

. Nucl. Phys. A 493, 61-82 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(89)90532-0A relativistic theory of superdeformations in rapidly rotating nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 511, 279-300 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(90)90160-NRelativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov description of the neutron halo in 11Li

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3963-3966 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3963Relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory with both zero range and finite range Gogny force and their application

. Nucl. Phys. A 635, 3-42 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00178-XGiant halo at the neutron drip line

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 460-463 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.460Giant neutron halo in exotic calcium nuclei

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 19, 312 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/19/3/308The relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov description of charge changing cross-section for C,N,O and F isotopes

. Phys. Lett. B 532, 209-214 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(02)01574-5Magic numbers for superheavy nuclei in relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory

. Nucl. Phys. A 753, 106-135 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.02.086Proton radioactivity in relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Systematic study of elastic proton-nucleus scattering using relativistic impulse approximation based on covariant density functional theory

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 160 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-01072-xNeutron halo in deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Odd systems in deformed relativistic Hartree Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 29,Influence of pairing correlations on the size of the nucleus in relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Shape decoupling effects and rotation of deformed halo nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 41, 75-85 (2024). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.41.2023CNPC56Recent progress on halo nuclei in relativistic density functional theory

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 41, 191-199 (2024). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.41.2023CNPC28Towards a high-precision nuclear mass table with deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Chin. Sci. Bull. 66, 3561-3569 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2020-1601Deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum with a point-coupling functional: Examples of even-even Nd isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum with a point-coupling functional. II. Examples of odd Nd isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 106,New parametrization for the nuclear covariant energy density functional with a point-coupling interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Crucial test for covariant density functional theory with new and accurate mass measurements from Sn to Pa

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum, I: Even-even nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 144,Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum, II: Even-Z nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 158,Shrunk halo and quenched shell gap at N=16 in 22C: Inversion of sd states and deformation effects

. Phys. Lett. B 785, 530-535 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.08.071Effects of pairing, continuum, and deformation on particles in the classically forbidden regions for Mg isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Study of ground state properties of carbon isotopes with deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Nucl. Phys. A 1003,Quasifree neutron knockout reaction reveals a small s-orbital component in the borromean nucleus 17B

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Deformed two-neutron halo in 19B

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Study of the deformed halo nucleus 31Ne with Glauber model based on microscopic self-consistent structures

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 65,Missed prediction of the neutron halo in 37Mg

. Phys. Lett. B 844,Collapse of the N=28 shell closure in the newly discovered 39Na nucleus and the development of deformed halos towards the neutron dripline

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Nuclear magnetism in the deformed halo nucleus 31Ne

. Phys. Lett. B 855,A unified description of the halo nucleus 37Mg from microscopic structure to reaction observables

. Phys. Lett. B 849,Toward a unified description of the one-neutron halo nuclei 15C and 19C from structure to reaction

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 251 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01464-7Nuclear charge radii and shape evolution of Kr and Sr isotopes with the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Odd-even shape staggering and kink structure of charge radii of Hg isotopes by the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Lett. B 847,Charge radii and their deformation correlation for even-Z nuclei in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 112,Prolate-shape dominance in atomic nuclei within the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Nuclear shape evolution of neutron-deficient Au and kink structure of Pb isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Bubble nuclei with shape coexistence in even-even isotopes of Hf to Hg

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Shape coexistence and neutron skin thickness of Pb isotopes by the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Evolution of N=20,28,50 shell closures in the 20≤Z≤30 region in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Chin. Phys. C 48,Shell structure and shape transition in odd-Z superheavy nuclei with proton numbers Z=117, 119: Insights from applying deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Magic number N=350 predicted by the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum: Z=136 isotopes as an example

. Particles 7, 1078-1085 (2024).Exploring the neutron magic number in superheavy nuclei: Insights into N=258

. Particles 7, 1086-1094 (2024).Examination of possible proton magic number Z = 126 with the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Particles 8, 2 (2025).Shell structure evolution of U, Pu, and Cm isotopes with deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in a continuum

. Particles 8, 19 (2025).Ground-state properties and structure evolutions of odd-A transuranium Bk isotopes from deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 111,One-proton emission from 148-151Lu in the DRHBc+WKB approach

. Phys. Lett. B 845,α-decay half-lives for even-even isotopes of W to U

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Triaxial shape of the one-proton emitter 149Lu

. Phys. Lett. B 856,Calculation of α decay half-lives for Tl, Bi, and At isotopes

. Particles 8, 42 (2025).Possible bound nuclei beyond the two-neutron drip line in the 50≤Z≤70 region

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Possible existence of bound nuclei beyond neutron drip lines driven by deformation

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Odd-even differences in the stability “peninsula” in the 106≤Z≤112 region with the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Symmetry energy from two-nucleon separation energies of Pb and Ca isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Inner fission barriers of uranium isotopes in the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Chin. Phys. C 48, 1-8 (2024).Determining the ground state for superheavy nuclei from the deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Particles 7, 1139-1149 (2024).Selected advances in nuclear mass predictions based on covariant density functional theory with continuum effects

. AAPPS Bulletin 35, 13 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-025-00153-xThe optimized point-coupling interaction for the relativistic energy density functional of Hartree-Bogoliubov approach quantifying the nuclear bulk properties

. Phys. Lett. B 842,Nuclear ground state observables and QCD scaling in a refined relativistic point coupling model

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Self-consistent Hartree description of deformed nuclei in a relativistic quantum field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 36, 354-364 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.36.354Microscopic justification of the equal filling approximation

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Improved high-precision mass measurements of mid-shell neon isotopes

. Nucl. Phys. A 1033,Nuclear structure of dripline nuclei elucidated through precision mass measurements of 23Si, 26P, 27,28S, and 31Ar

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133,High-precision mass measurement of 24Si and a refined determination of the rp process at the A=22 waiting point

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Mass measurement of 27P to constrain type-I x-ray burst models and validate the isobaric multiplet mass equation for the A=27,T=32 isospin quartet

. Phys. Rev. C 108,First Penning trap mass measurement of 36Ca

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Investigating nuclear structure near N=32 and N=34 Precision mass measurements of neutron-rich Ca, Ti, and V isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Precision mass measurements of neutron-rich scandium isotopes refine the evolution of N=32 and N=34 shell closures

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Bρ-defined isochronous mass spectrometry: An approach for high-precision mass measurements of short-lived nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Study of the N=32 and N=34 shell gap for Ti and V by the first high-precision multireflection time-of-flight mass measurements at bigRIPS-SLOWRI

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Summit of the N=40 island of inversion: Precision mass measurements and ab initio calculations of neutron-rich chromium isotopes

. Phys. Lett. B 833,Mapping the N=40 island of inversion: Precision mass measurements of neutron-rich Fe isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Erratum: Precision mass measurements of 67Fe and 69,70Co: Nuclear structure toward N=40 and impact on r-process reaction rates [Phys. Rev. C 101, 041304(R) (2020)]

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Mass measurements towards doubly magic 78Ni: Hydrodynamics versus nuclear mass contribution in core-collapse supernovae

. Phys. Lett. B 833,Mass measurement of upper fp-shell N=Z−2 and N=Z−1 nuclei and the importance of three-nucleon force along the N=Z line

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Mass measurements of 60−63Ga reduce x-ray burst model uncertainties and extend the evaluated T=1 isobaric multiplet mass equation

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Mass measurements of neutron-rich A≈90 nuclei constrain element abundances

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Isochronous mass measurements of neutron-deficient nuclei from 112Sn projectile fragmentation

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Identification of a potential ultralow-Q-value electron-capture decay branch in 75Se via a precise Penning trap measurement of the mass of 75As

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Mass measurements show slowdown of rapid proton capture process at waiting-point nucleus 64Ge

. Nat. Phys. 28, 1-7 (2023).Mass measurements of As, Se, and Br nuclei, and their implication on the proton-neutron interaction strength toward the N=Z line

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Examining the nuclear mass surface of Rb and Sr isotopes in the A≈104 region via precision mass measurements

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Precision mass measurements in the zirconium region pin down the mass surface across the neutron midshell at N=66

. Phys. Lett. B 856,Precision mass measurement of lightweight self-conjugate nucleus 80Zr

. Nat. Phys. 17, 1408-1412 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-021-01395-wFirst direct mass measurement for neutron-rich 112Mo with the new ZD-MRTOF mass spectrograph system

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Mass measurements of neutron-rich nuclei near N=70

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Investigating the effects of precise mass measurements of Ru and Pd isotopes on machine learning mass modeling

. Phys. Rev. C 110,First application of mass measurements with the rare-RI ring reveals the solar r-process abundance trend at A=122 and A=123

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,High-precision mass measurements of neutron deficient silver isotopes probe the robustness of the N=50 shell closure

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133,High-precision Penning-trap mass measurements of Cd and In isotopes at JYFLTRAP remove the fluctuations in the two-neutron separation energies

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Mass measurements of 99-101In challenge ab initio nuclear theory of the nuclide 100Sn

. Nat. Phys. 17, 1099-1103 (2021).High-precision measurements of low-lying isomeric states in 120-124In with the JYFLTRAP double Penning trap

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Mass measurements of neutron-rich indium isotopes for r-process studies

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Direct mass measurements to inform the behavior of 128mSb in nucleosynthetic environments

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Precise mass measurements of A=133 isobars with the Canadian Penning trap: Resolving the Qβ- anomaly at 133Te

. Phys. Lett. B 858,Mass measurements in the 132Sn region with the JYFLTRAP double Penning trap mass spectrometer

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Comprehensive mass measurement study of 252Cf fission fragments with MRTOF-MS and detailed study of masses of neutron-rich Ce isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Searching for the origin of the rare-earth peak with precision mass measurements across Ce–Eu isotopic chains

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Exploring the limits of existence of proton-rich nuclei in the Z=70−82 region

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Mass measurements of neutron-deficient Yb isotopes and nuclear structure at the extreme proton-rich side of the N=82 shell

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Discovery of new isotope 241U and systematic high-precision atomic mass measurements of neutron-rich Pa-Pu nuclei produced via multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Target mass dependence of isotensor double charge exchange: Evidence for deltas in nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 25, 3218-3220 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.25.3218Precision mass measurements of 67Fe and 69,70Co: Nuclear structure toward N=40 and impact on r-process reaction rates

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Nuclear mass measurements map the structure of atomic nuclei and accreting neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Time-of-Flight Mass Measurements for Nuclear Processes in Neutron Star Crusts

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107,Mass measurement of neutron-rich isotopes from 51Ca to 72Ni

. Z. Phys. A 349, 25-32 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01296329Direct Mass Measurements of Short-Lived A=2Z−1 Nuclides 63Ge, 65As, 67Se, and 71Kr and Their Impact on Nucleosynthesis in the rp Process

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106,βdecay of the proton-rich Tz=−1/2 nucleus, 71Kr

. Phys. Rev. C 56, 745-752 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.56.745Mirror decay of 75Sr

. Eur. Phys. J. A 16, 359-363 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2002-10103-0Isomerism in 96Ag and non-yrast levels in 96Pd and 95Rh, studied in β decay

. Nucl. Phys. A 720, 245-273 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(03)01093-5Mass measurements near the r-process path using the Canadian Penning Trap mass spectrometer

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Measurement of β- end-point energies using a Ge detector with Monte Carlo generated response functions

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 337, 106-115 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(93)91142-AA Skyrme parametrization from subnuclear to neutron star densities Part II. Nuclei far from stabilities

. Nucl. Phys. A 635, 231-256 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00180-8Variations on a theme by Skyrme: A systematic study of adjustments of model parameters

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Nuclear energy density optimization: Large deformations

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Nuclear ground-state properties probed by the relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov approach

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 156,Beyond-mean-field dynamical correlations for nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in continuum

. Chin. Phys. C 46,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.