Introduction

Modern nuclear physics has evolved into a field of increasing complexity, accompanied by the development of a wide range of theoretical models capable of describing diverse systems and observables with growing precision [1-5]. Rather than focusing solely on numerical predictions, it is increasingly important to deepen our understanding of the predictive capabilities and reliability of theoretical models, and to elucidate their connection with experimental observations. This shift in perspective has motivated the growing emphasis on uncertainty quantification in recent years [6-13], which not only provides quantitative measures of predictive reliability, but also allows the systematic constraint of model parameters through realistic experimental data. These advances ultimately lead to deeper insights into the interpretation of the observed nuclear phenomena.

Statistical methods have played a pivotal role in this paradigm shift. Although traditional frequentist approaches are widely used for parameter estimation and regression [9], the rise in machine learning (ML) techniques, particularly within the Bayesian framework, has opened new opportunities for model calibration, experimental design, and model mixing [14-20]. In contrast to classical frequentist statistics, Bayesian inference incorporates prior knowledge of a model and its parameters into posterior distributions, treating data as probabilistic ensembles rather than isolated points [21]. This framework is particularly advantageous for rigorous uncertainty quantification.

A key challenge in Bayesian analysis is the high computational costs associated with large-scale sampling. Millions or even billions of model evaluations are typically required to achieve convergence of posterior distributions. This is prohibitive for state-of-the-art nuclear models, which are often characterized by large Hilbert spaces and high-dimensional operators [22]. Efficient and accurate surrogate models are essential to address this bottleneck. Although Gaussian Process (GP) emulators have been applied in previous studies [8], their data-driven nature often limits physical interpretability. This limitation motivates the adoption of model-driven strategies, such as the reduced basis method (RBM), which has emerged as a powerful tool for reducing the computational cost of physics-informed simulations [23-25]. The RBM is particularly effective because it constructs low-dimensional approximations rooted in the fundamental dynamics of the system, such as the Schrödinger equation. Certain implementations of the RBM are mathematically similar to the variational principle [24], making them suitable for uncertainty analysis in linearly varying parameter spaces [19, 26-28]. Furthermore, the RBM enables effective extrapolation into regions that are inaccessible to direct high-fidelity computations [29].

One of the most cutting-edge directions in nuclear physics is the study of nuclei near driplines, which are considered open quantum systems. These exotic nuclei have attracted considerable attention because of their unique structural features [5, 30, 31], where continuum coupling and resonance degrees of freedom play central roles. Accurately describing such systems requires models that explicitly account for these continuum effects, which significantly increases the complexity of high-fidelity computations. At present, only a limited number of microscopic models are capable of treating resonant states in a consistent and unified framework [5, 32, 33], among which the Gamow Shell Model (GSM) and its variants [5] are prominent examples. To quantify or even improve the computational capabilities of these models, it is essential to advance our understanding of the dripline, and ultimately, the unified nuclear chart.

Although the ground states of stable nuclei can be accurately reproduced using a simple Galerkin RBM [26, 34], modeling open quantum systems presents new challenges. In such systems, exotic structural features and nonsmooth parameter dependencies significantly hinder the performance of standard RBM emulators, thereby complicating the large-scale sampling required for Bayesian inference. A key characteristic of dripline nuclei is the presence of resonant states, whose wavefunctions exhibit fundamentally different asymptotic behavior compared with bound states [35]. Developing reliable emulators for such resonance states remains a challenge. For example, Ref. [36] proposed an improved eigenvector continuation (EC) scheme to extrapolate resonance energies from a bound-state training subspace.

In this study, we employed an EC-based emulator to perform uncertainty quantification for the weakly bound nucleus 6Be within the Gamow coupled-channel (GCC) framework. To further address the asymptotic behavior of resonant wavefunctions, we apply a Lippmann–Schwinger (L–S) equation-based correction, aiming to construct an emulator that can extrapolate from the bound to resonant states and provide corrected wavefunctions within the reduced subspace.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce the three-body GCC model, Bayesian inference framework, and the construction of the EC emulator. In Sect. 3, we present the uncertainty quantification results for 6Be and the outcomes of the L–S correction scheme. Finally, a summary and outlook are provided in Sect. 4.

Methods

The three-body Gamow coupled-channel method

In this study, we focused on atomic nuclei that can be effectively described as three-body systems. Within the three-body GCC model, such systems are modeled as frozen cores with two valence nucleons. The corresponding Hamiltonian is given by

The nucleon-nucleon interaction between the two valence nucleons

In the GCC framework, the total three-body wave function is expressed in Jacobi coordinates, which is particularly advantageous for describing the asymptotic behavior of the system [33, 38]. The angular components are constructed using hyperspherical-harmonic oscillator basis functions, while the radial part—determined by a set of quantum numbers representing various configurations—is expanded using the Berggren basis [39, 40]. This basis is directly related to the incoming and outgoing momenta of free particles as well as the complex energy of the eigenstates, satisfying the orthogonality and completeness relationship [41]. The Berggren basis is a key feature of the GCC model, allowing it to treat scattering states, resonances, and bound states equally. This provides a universal framework for modeling the nuclear structure and scattering properties.

Bayesian inference framework

The basic philosophy of Bayesian inference is encapsulated by Bayes’ theorem, which in this context is expressed as:

However, the high computational cost of high-fidelity models, such as GCC, makes direct evaluations for every parameter sample prohibitive. To overcome this challenge, we employed an emulator based on the reduced-basis method, which offers a fast and accurate approximation of the original model. This emulator dramatically reduces the computational time while preserving the accuracy, thereby enabling efficient posterior sampling within a feasible timeframe.

The emulator

Intrinsically, the wavefunction exhibits several consistent properties as the parameters of the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) vary, assuming that the system remains linear. For example, when the total potential strength 𝑽 is sufficiently large, the system becomes tightly bound and the corresponding eigenstate wave function is spatially localized. By contrast, for a weak total potential strength, the system becomes loosely bound or unbound, and the wave function displays an extended asymptotic tail, which is characteristic of resonant states [35]. By leveraging these properties, one can avoid repeated diagonalization of the high-dimensional, high-fidelity Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) for each parameter set. Instead, the emulator algorithm learns the trajectory of the wave functions across the parameter space, thereby enabling efficient and accurate predictions. This is mathematically expressed as

This basis spans a low-dimensional subspace that effectively represents the main characteristics of the physical eigenstates, in stark contrast to the significantly larger dimensionality of the original free-particle basis. By inserting the reduced basis expansion into the Schrödinger equation, we obtain a projected Hamiltonian defined in this reduced subspace, with matrix elements given by

A central challenge in reduced-basis modeling is identifying the physically relevant eigenstate among many solutions of the reduced subspace. In contrast to high-fidelity calculations based on the Berggren basis—where the analytic structure of the complex energy plane facilitates clear classification of bound, resonant, and scattering states—the emulator’s eigenvalues are often irregularly distributed and do not exhibit distinct branch cuts. Consequently, additional selection criteria were required to isolate the target physical eigenstate.

One possible approach is to examine the eigenvector components on a principal-component basis. In theory, physically meaningful eigenstates should exhibit dominant contributions from the first few principal components, because these components are associated with localized structures in the configuration or momentum space. However, this strategy is hindered by the complexity of configuration mixing and the lack of direct physical interpretability of the individual principal components.

Given that the current reduced basis method (RBM) is mathematically equivalent to a variational approach [24], the physical eigenstate is expected to closely resemble the training basis. In contrast, spurious solutions—such as those corresponding to scattering-like states—typically show weaker projections onto this basis. To distinguish the target eigenstate robustly, we adopted an overlap-based method. In this approach, a reference wave function is selected in advance, and the overlap between this reference and each eigenfunction in the reduced subspace is computed as:

To improve the accuracy of the emulator’s approximation, we applied a wavefunction correction scheme inspired by the Lippmann–Schwinger equation [43] using the following iterative formula:

Model space and parameters

We selected the two-proton emitter 6Be as our test nucleus, which has been extensively studied [44-46]. The experimental energy of the 0+ state of 6Be has been reported to be 1.372 - 0.092i MeV.

In the GCC framework, the hyperangular configuration for 6Be is constructed as described in Ref. [33]. The quantum number set

To fit the experimental energy, we adjusted several nonaffine potential parameters and the Berggren basis contour. The nuclear force is primarily governed by six parameters, which we set as:

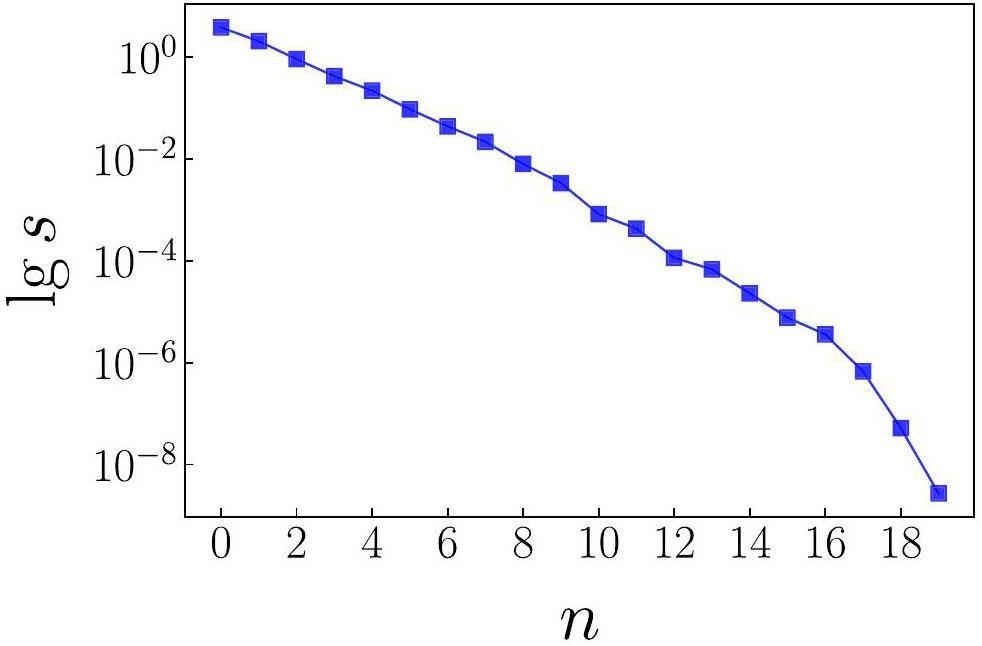

To maximize the accuracy of the emulator, both the bound and resonance states were included in the training subspace, although the target state was resonant. The training parameter is the strength of the total potential, which varies between [0.9, 1] for resonance states and [1.2, 2] for bound states, to obtain their corresponding wave functions. PCA is then performed on the 20 training vectors with a singular value accuracy of 10-15, which is close to the computational limitations of our current servers.

The standard deviation σmo was chosen empirically to ensure effective convergence of the probability distribution following previous studies, and was set to 0.25% of the corresponding experimental value [19, 27]. The error σex is negligible compared with the other sources of uncertainty. For the emulator error σem, we collected random samples and fitted their error distribution with a Gaussian function as well as the Berggren basis contour properties, ultimately determining its value to be 15% of the experimental value, as will be discussed in detail later. Prior studies employed uncertainty decomposition methods to address model deviations with improved precision [7]. However, given the much larger deviations in our emulator, we omitted such corrections from this analysis.

We assume that the prior distribution for parameter vector 𝒄 follows a multivariate normal distribution as follows:

Results and Discussions

Computational Performance of the Emulator

PCA is a powerful dimensionality-reduction technique that is particularly effective when the training space exhibits redundancy. To quantitatively assess this redundancy, we analyzed the singular values of the principal components and determined an appropriate cutoff for the subspace dimension. Fig. 1 shows the singular value spectrum of the dataset. Although resonance states feature abrupt changes in their asymptotic behavior compared with bound states, their key features can still be efficiently captured via PCA owing to similarities in the local structure of their wave functions. Specifically, the first component that captures the largest singular value in Fig. 1 resembles the shapes of the bound states. The second component corresponds to the average shape of a sharp peak in the resonance wave function in momentum space, as well as the oscillatory outgoing wave. The exponentially decaying weighted components are more similar to the free-particle basis, which is analogous to the Berggren basis.

The singular value analysis indicates that our training space sufficiently captures the high-fidelity properties. While both bound and resonance features are included, the emulation process primarily functions as an interpolation operator because the parameter variations are smooth. Therefore, it is more reasonable to estimate the error between the emulator and GCC using a statistical approach rather than providing σem point by point.

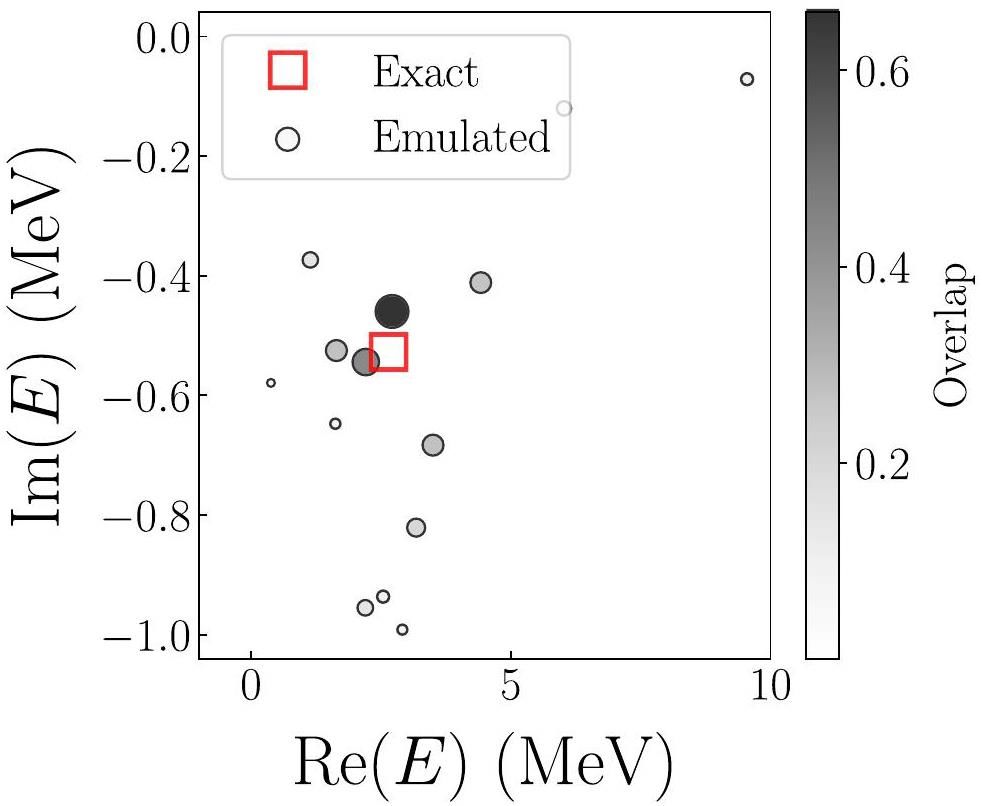

As discussed previously, isolating the target eigenstate within the emulator subspace is crucial. To achieve this, we employed an overlap technique, which is mathematically defined in Eq. (12). Figure 2 presents the overlap analysis for a representative parameter point given by [c0, c1, c2]T = [0.9, 0.8, 1.1]T. In this case, the reference wave function was chosen as the resonance state obtained using all potential strengths set to unity. This reference is sufficiently diffuse to suppress spurious overlaps with scattering-like states, which may otherwise introduce significant noise into the overlap calculation.

In Fig. 2, each circle corresponds to the eigenvalue of the emulator Hamiltonian in the reduced subspace. The size and color intensity of the circles represent the magnitude of overlap with the reference wave function. The largest overlap is associated with the emulator-predicted eigenstate, marked by the darkest circle, which yields an energy of

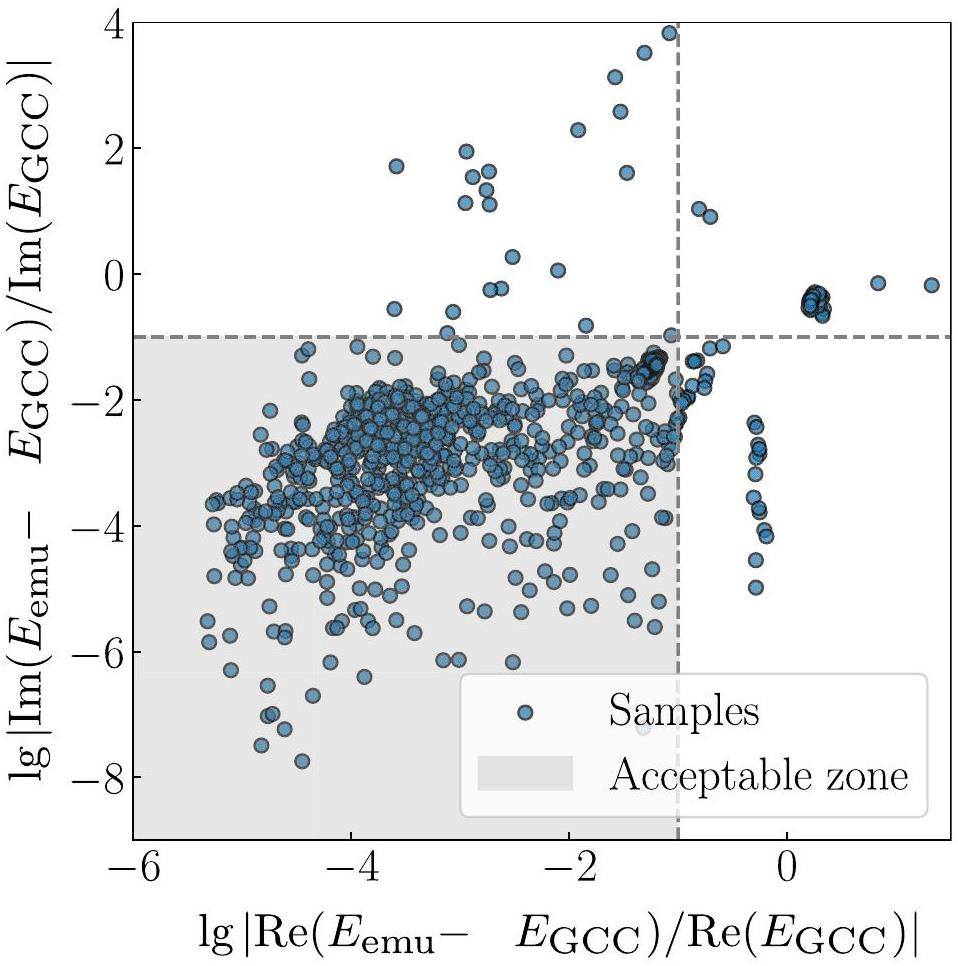

Assuming that the emulator error follows a normal distribution, we estimated it by sampling 1000 random parameter points. After excluding unphysical scattering-like states (102 invalid cases), we retained 898 valid samples for the analysis. The resulting relative error distributions are shown in Fig. 3, where over 90% of the predictions exhibited deviations below 10% in both the real and imaginary parts. The mean relative error is approximately 15%, demonstrating the overall robustness of the emulator. Relative errors provide a more consistent metric across varying energy scales than absolute deviations. In practice, because exact GCC results are unavailable during sampling, we use the experimental energy

The remarkable computational efficiency of the emulator is worth emphasizing. The diagonalization of the projected Hamiltonian requires only 5.26 × 10-3 s, which is nearly four orders of magnitude faster than the 36.6 s required for full high-fidelity GCC calculation. This acceleration enabled the use of an emulator for large-scale posterior sampling and uncertainty quantification.

Constraining potentials in 6Be

We investigated the 0+ ground state of 6Be by using our Bayesian analysis framework. Following a burn-in of 1,000 points and collection of 100,000 posterior samples, we achieved an acceptance rate of 36.7%. The entire computation was completed in approximately 3 h on a server, which would have required nearly four months without the use of the emulator.

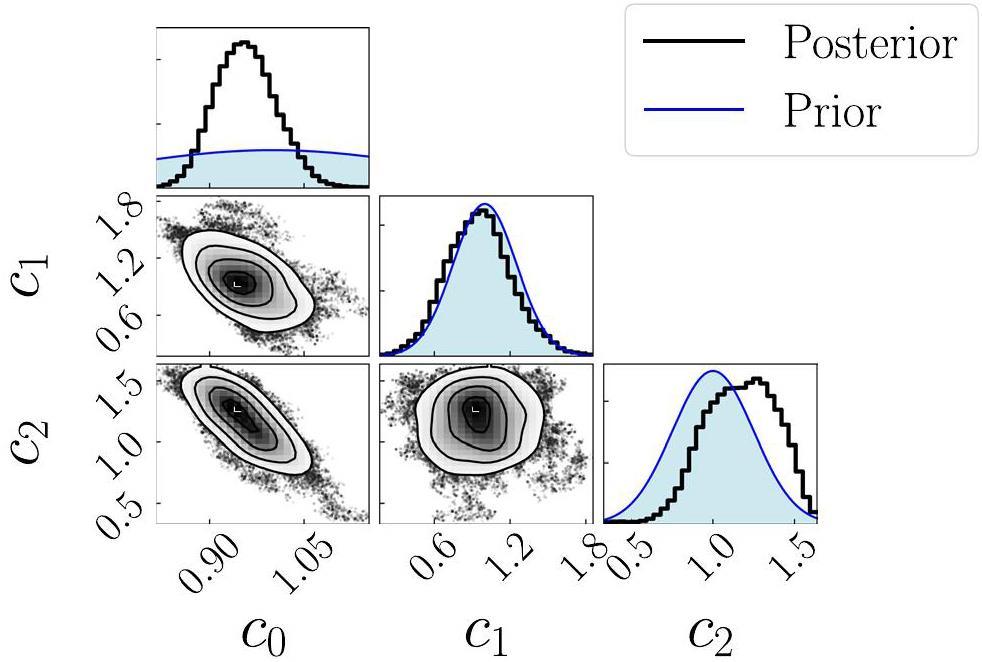

Figure 4 presents the posterior distributions for all three model parameters. Evidently, the central force strength c0 is strongly constrained by the data. In contrast, the spin-orbit strength c1 retains a distribution shape close to its prior value, suggesting limited sensitivity of the observable to this parameter in the current setting. The distribution of the nucleon-nucleon interaction strength c2 shows a moderate deviation from the prior value, which may be attributed to a negative correlation with the central force strength c0.

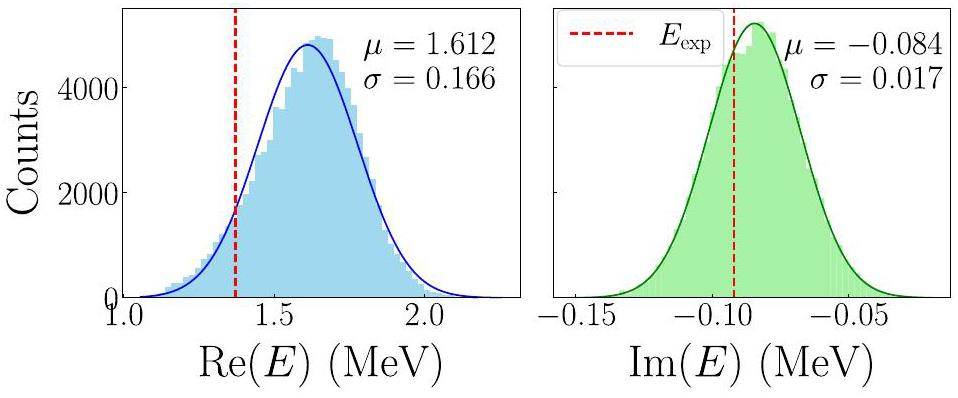

We further visualize the distribution of the calculated resonance energies under the sampled posterior parameters, as shown in Fig. 5. The peak values of the distributions exhibited noticeable deviations from the experimental resonance energies. This discrepancy may arise partly because the likelihood function is more sensitive to the imaginary part of energy, which is smaller than the real energy. Moreover, latent variables that are not directly sampled in this study, such as the diffuseness and radius parameters of the WS potential, also contribute to the overall model uncertainty.

We fitted the predicted energy distributions shown in Fig. 5 to Gaussian functions, extracting both the mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) values, which are indicated in the upper-right corner of each subplot. The predicted mean energies deviate by 17% (real energy) and 8% (imaginary energy) from the reference values. The energy deviations fall within approximately ± 1σ credible intervals, demonstrating the statistical consistency between the results of the emulator and the expected uncertainty distribution. Furthermore, this implies that emulators can be developed for other non-affine parameters in the future to investigate the overall impact of our model on multi-nucleon decay.

Correcting the emulated eigen-pair with L–S method

As discussed above, the (L–S) correction not only yields consistent improvements in both eigenvalues and wavefunctions, but also enables a natural extension of real-space training data to the complex energy plane.

Here, we examine the performance of our L–S correction method for two types of training spaces in the 6Be system: one composed of bound-state solutions, and the other of resonance-state solutions. We selected a representative parameter point, [c0, c1, c2] = [0.925, 1,1.4], drawn from the posterior distribution shown in Fig. 4. This parameter set corresponds to a resonance state that is close to the experimental value.

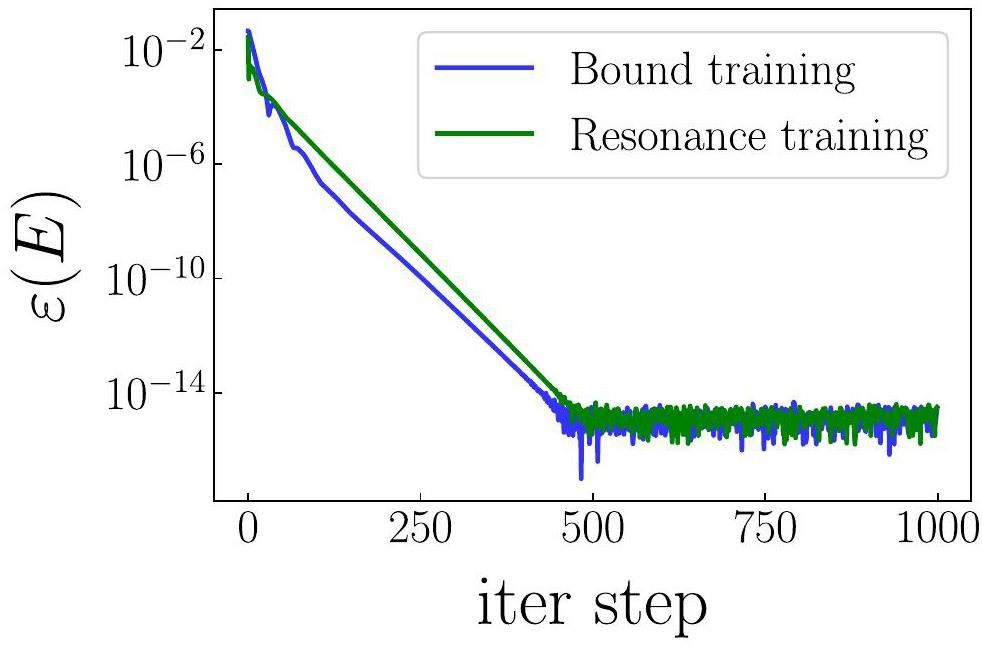

The maximum iteration step was set to 1000, and we defined ϵ(E) as the relative error of each step compared to the previous step. Figure 6 illustrates the convergence behavior of our iteration, whereas Table 1 lists the final corrected energy with high accuracy. The results demonstrate that the L–S correction can converge to nearly the same energy within a few hundred steps regardless of whether the training space consists of bound or resonance states. This is particularly beneficial for improving the extrapolation capability of the RBM, particularly when only bound high-fidelity solutions are available as a training subspace. In Table 1, the L–S correction significantly improved the energy accuracy, particularly the width, bringing it closer to the GCC high-fidelity value.

| Bound training | Resonance training | |

|---|---|---|

| 1.520-0.085(4)i | 1.520-0.085(4)i | |

| 2.394-0.008(4)i | 1.807-0.052(7)i | |

| 1.844-0.091(4)i | 1.844-0.091(4)i |

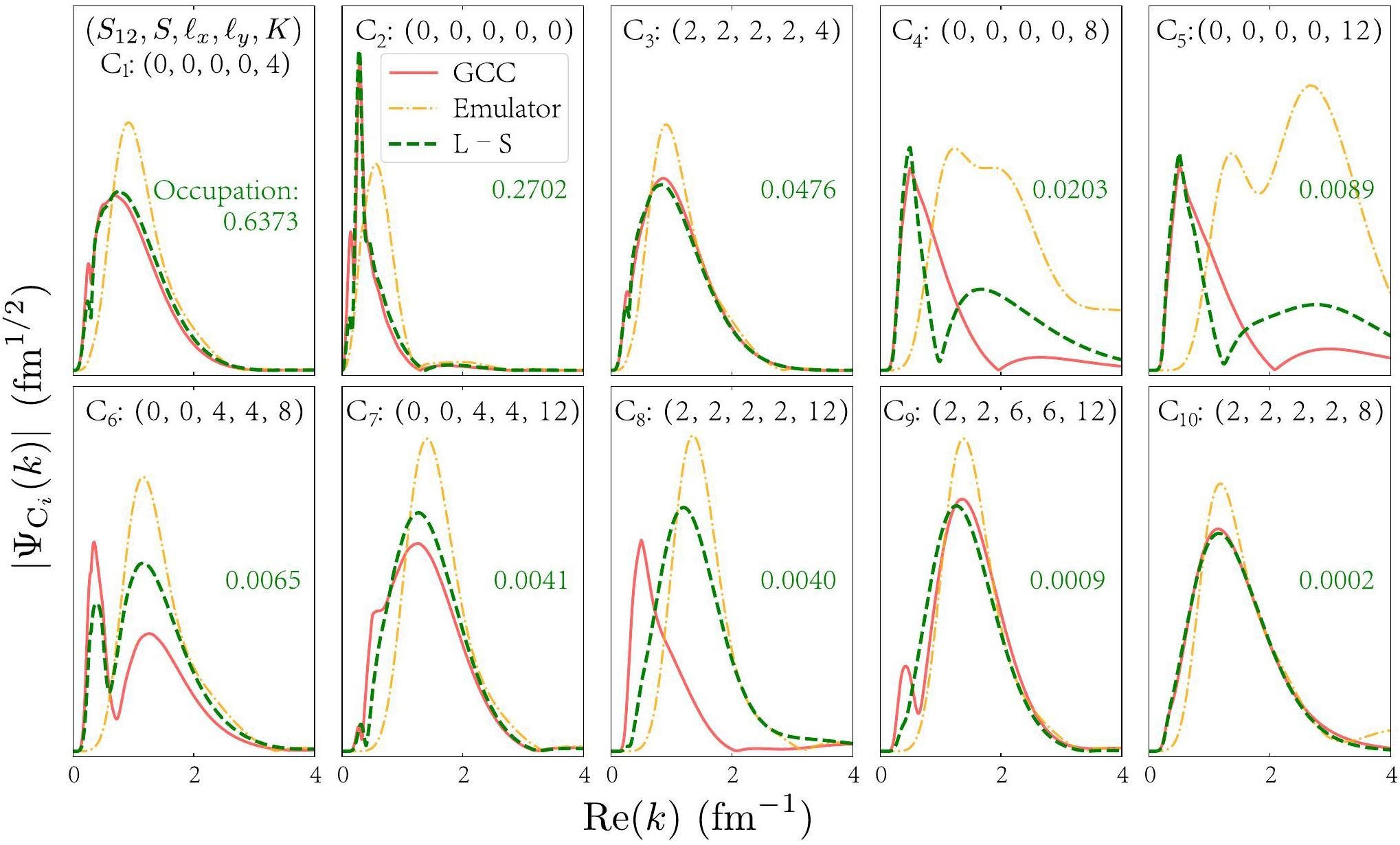

Remarkably, the L–S correction can restore the resonance energy even when the emulator subspace consists only of bound states, which do not exhibit oscillatory asymptotic behavior outside the nucleus in the resonance state. Fig. 7 illustrates how the wavefunction in momentum space is restored. The emulated wavefunction closely resembles that of the bound states, with small contributions from the low-momentum components and outer regions of the coordinate space. The dominant configurations, such as C1 and C2 with occupation probabilities exceeding 0.1 and quantum numbers K = 0 or 4, are well recovered, leading to an energy correction that closely approaches the resonance state. In contrast, configurations associated with higher K values (e.g., K = 8 and 12) exhibit larger deviations in the wavefunction shape compared with the high-fidelity results. These discrepancies are particularly pronounced at low momenta, particularly below 2 fm-1. This can be attributed to the fact that high-K configurations typically represent the subdominant components in the total wavefunction. As such, infinitesimal features such as inflection points on the momentum axis, which are not well captured by the original emulator, can lead to amplified errors in the correction process. Nevertheless, these results highlight that the L–S correction method can be an effective tool for extending the emulator to continuum physics. Further studies should be conducted in the future.

Summary

In this study, we developed a Bayesian uncertainty quantification framework for resonant states in open quantum systems by integrating an RBM emulator with a GCC model. The emulator was constructed using the EC technique with a training subspace that included both the bound and resonant components. To isolate physical resonance solutions from scattering-like background states, we introduced an overlap-based selection method that enables accurate and robust emulation of complex energy eigenvalues relevant to continuum structures.

We applied this framework to an unbound nucleus 6Be for the first time. The EC emulator demonstrated both accuracy and efficiency, achieving at least four orders of magnitude in computational speedup relative to full GCC calculations. Large-scale Bayesian sampling was completed within three hours, allowing us to identify key sensitivity patterns in the parameter space. In particular, we found that the central component of the nuclear force plays a dominant role in determining the resonance position, while the valence nucleon–nucleon interaction contributes a negatively correlated uncertainty. The relative uncertainties in the predicted real and imaginary energy components were 17% and 8%, respectively, indicating a greater sensitivity of the resonance widths to the interaction strength.

Furthermore, we explored the extrapolation of resonance properties from a bound-state training subspace by using a correction scheme based on the Lippmann–Schwinger equation. This method provides refined wavefunctions within the reduced subspace, and consistently improves the emulator’s output. The iterative correction converged to the machine precision (10-15) within 400 steps. The corrected energies closely approach the high-fidelity solutions regardless of whether the training subspace is bound or resonant. The corrected wavefunctions restored the dominant configurations well, particularly in the asymptotic region of the resonance states. Most of the remaining errors originate from higher-K configurations, where the L–S correction becomes suboptimal owing to the absence of relevant perturbative components in the initial emulated wavefunction used for the iteration. These findings not only enhance the practical predictive power of uncertainty quantification but also advance algorithmic methods for resonance modeling, contributing to the broader development of dripline nuclear physics. The GCC framework’s inherent ability to describe open quantum systems makes it ideal for extension to heavier two-nucleon emitters. To enable realistic applications for these nuclei, our future work will focus on incorporating effects such as core excitations and deformation into the uncertainty quantification.

Unified ab initio approaches to nuclear structure and reactions

. Phys. Scr. 91,Coupled-cluster computations of atomic nuclei

. Reports on Progress in Physics 77,Progress in ab initio in-medium similarity renormalization group and coupled-channel method with coupling to the continuum

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 215 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01585-0Error estimates of theoretical models: a guide

. J. Phys. G 41,Uncertainty decomposition method and its application to the liquid drop model

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Uncertainty quantification for nuclear density functional theory and information content of new measurements

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114,Quantified gamow shell model interaction for psd-shell nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Theoretical uncertainty quantification for heavy-ion fusion

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Ab initio predictions link the neutron skin of 208pb to nuclear forces

. Nat. Phys 18, 1196-1200 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01715-8Quantifying correlated truncation errors in effective field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Multiscale physics of atomic nuclei from first principles

. Phys. Rev. X 15,Iterative Bayesian Monte Carlo for nuclear data evaluation

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 50 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01034-wBeyond the proton drip line: Bayesian analysis of proton-emitting nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Local Bayesian Dirichlet mixing of imperfect models

. Sci. Rep. 13, 19600 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46568-0Bayesian analysis of nuclear equation of state at high baryon density

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 194 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01345-6Model orthogonalization and bayesian forecast mixing via principal component analysis

. Phys. Rev. Res. 6,Bayes goes fast: Uncertainty quantification for a covariant energy density functional emulated by the reduced basis method.,

Front. Phys. 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1054524 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.1054524Toward accelerated nuclear-physics parameter estimation from binary neutron star mergers: Emulators for the tolman-oppenheimer-volkoff equations

. Astrophys. J. 974, 285 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad737cRecent progress in Gamow shell model calculations of drip line nuclei

. Physics 3, 977-997 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/physics3040062Colloquium: Eigenvector continuation and projection-based emulators

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96,Model reduction methods for nuclear emulators

. J. Phys. G 49,Training and projecting: A reduced basis method emulator for many-body physics

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Rose: A reduced-order scattering emulator for optical models

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Eigenvector continuation as an efficient and accurate emulator for uncertainty quantification

. Physics Letters B 810,Eigenvector continuation with subspace learning

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Open problems in the theory of nuclear open quantum systems

. J. Phys. G 37,Unbound 28O, the heaviest oxygen isotope observed: a cutting-edge probe for testing nuclear models

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01373-wStudy of the 7be (p, γ) 8b and 7li (n, γ)8Li capture reactions using the shell model embedded in the continuum

. Nucl. Phys. A 651, 289-319 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(99)00133-5Structure and decays of nuclear three-body systems: the Gamow coupled-channel method in Jacobi coordinates

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Applications of reduced-basis methods to the nuclear single-particle spectrum

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Illustrations of loosely bound and resonant states in atomic nuclei

. Am. J. Phys. 90, 118-125 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1119/10.0007045Towards scalable bound-to-resonance extrapolations for few-and many-body systems

. (2024). arXiv:arXiv:2409.03116Systematic investigation of scattering problems with the resonating-group method

. Nuclear Physics 286, 53-66 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(77)90007-0Recent progress in two-proton radioactivity

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 105 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01091-1Three-body systems with Lagrange-mesh techniques in hyperspherical coordinates

. Phys. Rev. C 67,Quantum resonances in a complex-momentum basis

. Ph.D. thesis,On the use of resonant states in eigenfunction expansions of scattering and reaction amplitudes

. Nucl. Phys. A 109, 265-287 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(68)90593-9BUQEYE guide to projection-based emulators in nuclear physics

. Front. Phys. 10,A novel emulator for continuum physics: the insight into applications on realistic models (in preparation)

.Role of diproton correlation in two-proton-emission decay of the 6Be nucleus

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Three-body decay of 6Be

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Democratic decay of 6Be exposed by correlations

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109,Optimal scaling for various metropolis-hastings algorithms

. Statistical science 16, 351-367 (2001).The authors declare that they have no competing interests.