Introduction

Atomic nuclei are self-bound quantum many-body systems, and a key goal in modern nuclear physics is to solve these systems using first principles. To achieve this, one can compute the ground-state and excited-state energies along with their corresponding wavefunctions, either in coordinate space or within a specific basis, such as the harmonic oscillator basis.

Methods in the coordinate space are typically represented by various Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) techniques, including diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) and the related Green’s function Monte Carlo (GFMC) [1-4]. These methods have proven to be successful in accurately determining the properties of light nuclei. However, a major obstacle of these methods is the Fermion sign problem: due to the antisymmetry property of the many-body wavefunction, the wavefunction necessarily contains both positive and negative amplitudes, which cannot be directly sampled using a probability distribution. Techniques such as the fixed-node approximation or constrained-path method are often employed to mitigate the sign problem [2, 4]. A key challenge in these methods is the requirement for a trial wavefunction that approximates the true wavefunction as closely as possible.

Configuration interaction (CI) methods, including the configuration interaction shell model (CISM) [5, 6] and no-core shell model (NCSM) [7, 8], provide direct and accurate frameworks for solving quantum many-body systems in basis space. However, the configuration space grows exponentially with the number of particles, making it computationally infeasible to store all the configurations in memory. To address this issue, one can truncate the configuration space using methods such as particle-hole truncation or ħω truncation. Despite these techniques, many configurations are still required to achieve converged results, which is impossible for large-dimension systems.

An alternative approach is the post-Hartree-Fock methods [9], which offers polynomial complexity. These include perturbative approaches, such as Many-Body Perturbation Theory (MBPT) [10-13], and non-perturbative approaches, such as the in-medium similarity renormalization group (IMSRG) [14-16] and Coupled Cluster (CC) [17, 18]. However, all of these approaches rely on truncation schemes, which may introduce inaccuracies, particularly in strongly correlated systems. Efforts to improve the accuracy by going to higher-order truncations [19, 20] are in progress. However, computational cost remains a significant challenge.

In 2009, Booth et al. developed a full configuration interaction quantum Monte Carlo method for quantum chemistry calculations [21]. This method samples wavefunctions in the configuration space, allowing the storage of only a small subset of important configurations that are often several orders of magnitude smaller than those in the full configuration space. Moreover, by utilizing signed walkers and walker annihilation, FCIQMC can avoid the Fermion sign problem and converge to the exact wavefunction without requiring prior knowledge of its nodal structure.

FCIQMC has been successfully applied to a range of systems [21-23], including both molecular and condensed matter systems, and has proven to be particularly effective for strongly correlated systems [24, 25]. Given its strengths, it shows promise for nuclear structure calculations. In this study, we developed a C++ code implementing FCIQMC, considering the symmetry properties of nuclear systems.

Several other quantum Monte Carlo methods also operate in configuration space, including the Monte Carlo shell model (MCSM) [26, 27], which constructs the basis by evolving in the auxiliary field and then diagonalizes the Hamiltonian using that basis; and the configuration interaction Monte Carlo (CIMC) [28, 29], which, despite its similar name to FCIQMC, uses a guiding wavefunction to perform a "fixed-node approximation" in configuration space. It is important to note that, although these methods share some similarities, they are fundamentally distinct from one another.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we introduce the theory and algorithm of FCIQMC and its enhanced variant. In Sect. 3, we present the benchmarking results with shell model calculations for Fe isotopes in the pf-shell and for an artificially constructed strongly correlated system. We also tested large-space calculations using examples of Mg isotopes in the full sdpf shell.

The Full configuration interaction quantum Monte Carlo

The CI method aims to solve the Schrödinger equation

Instead, the FCIQMC method samples wavefunctions in the configuration space. To achieve this, we use the projection method instead of the diagonalization method to obtain the ground-state wavefunction Ψ0 using the following operator:

Similar to QMC methods in coordinate space, the coefficient Ci can be either positive or negative, making it impossible to sample them directly as a probability distribution. In the FCIQMC method, this issue is addressed by introducing the so-called walkers, which are distributed across various determinants. The number of walkers in

During the warm-up period, we maintain a constant shift

When the imaginary time evolution reaches equilibrium, which means that the total walker number is almost stable, and the shift S fluctuates only slightly around the ground state, we begin the statistical period. We continued the equilibrium evolution for several steps and performed statistics to evaluate the ground-state energy. The shift parameter S can be used to evaluate the ground-state energy, and we can also use the local time energy:

The remaining challenge is the evolution of the imaginary time Schrödinger equation, Eq. (7) stably and effectively, which is key to the FCIQMC calculation. Every Δτ evolution is performed in the following three steps [21]:

The spawning step: For each walker in determinant

For a single excitation, we first select an occupied orbital (labeled a) from

For double excitation, we first select two occupied orbitals labeled by a and b. Similar to the single excitation discussed above, each selection of a pair of occupied orbitals has an equal probability. Then, we identify all pairs of unoccupied orbitals that have the same parity, total spin projection m, and total isospin projection tz as those of the two-body state formed by the a and b orbitals. From this set of unoccupied orbital pairs, we randomly selected one pair with an equal probability. As in the single-excitation case, the generation probability pgen(j|i) is determined by the product of the probabilities associated with selecting the pair of occupied orbitals and the pair of unoccupied orbitals.

In each spawning attempt, we performed either a single or double excitation chosen with probabilities psingle and

Diagonal death/cloning step: For each walker in determinant

The annihilation step: Collect all walkers in the same determinant (including the spawned walkers), and annihilate pairs of walkers with opposite signs until only walkers with the same sign remain in the determinant. This step is necessary to prevent exponential growth of walkers [21].

This algorithm can be easily extended to a Hamiltonian with three-body interactions, although we did not incorporated it in the present computational code. The only modification is that the spawning step should include triplet excitation.

The original FCIQMC [21], as described above, can work for some systems, but requires a minimum walker number that can be very large in certain cases. For example, with our code, we found that in sd and pf shells, the converged evolution requires a walker number that is almost equal to the dimension of a full configuration calculation which is due to the sign problem. During Monte Carlo evolution, some determinants may randomly acquire a small number of walkers with opposite signs to the main wavefunction [32]. These components of the wavefunction can spread in subsequent steps, which requires a large total walker number to adequately suppress them.

Deidre Cleland et al. showed that the walker number required for coverage can be dramatically reduced using initiator truncation [24]. In this method, one defines some important determinants as initiators and restricts non-initiator walkers from spawning to unoccupied determinants. In this way, we align the signs of the walkers in the small walker-number determinants with those in the large walker-number determinants, which helps to suppress the sign problem. This method is referred to as initiator FCIQMC (i-FCIQMC) [24]. The original Hamiltonian is truncated as follows:

Another improvement over the original FCIQMC method is the use of the floating-point walker number [33], which enhances the stability of the evolution and reduces the statistical error of the results. However, the floating-point walker approach can result in a large number of determinants being occupied by a small number of walkers. To reduce memory usage, a walker number cutoff Nocc was introduced [33]. In this method, if the walker number Ni is less than Nocc, it is either replaced by Nocc with a probability of

The i-FCIQMC method can also be used to obtain excited states [34]. In this respect, several parallel imaginary-time evolutions were performed. After each Δτ evolution, we used the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization to obtain the orthogonal components of the wavefunction.

Calculations and discussions

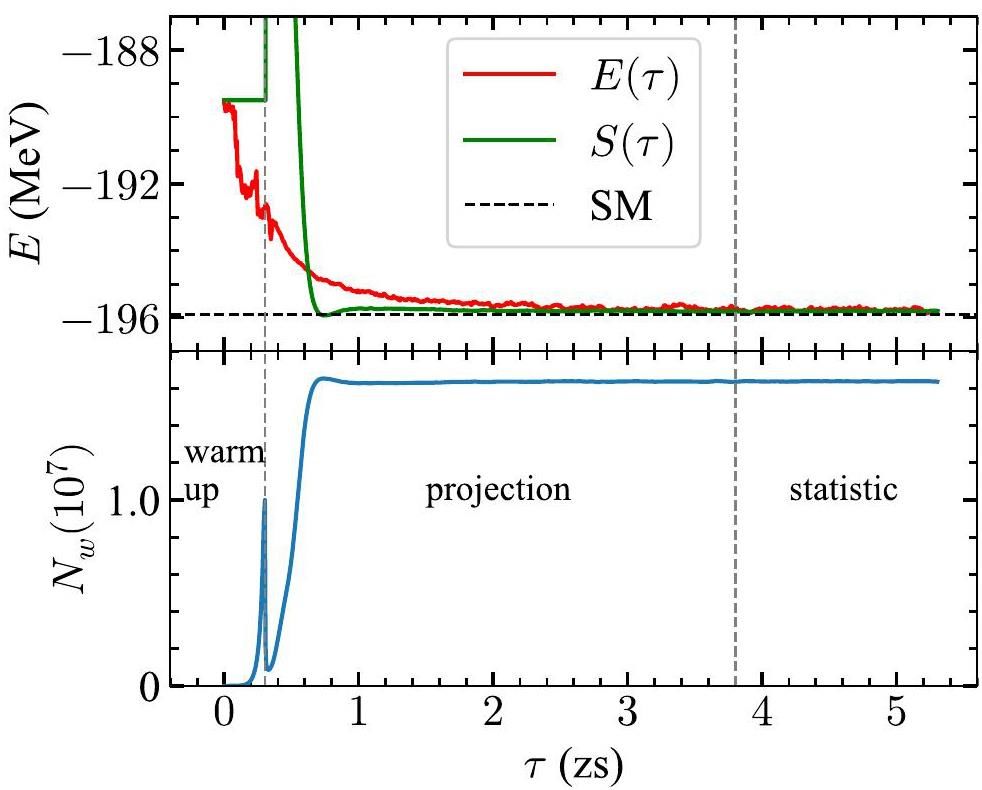

We first benchmarked our computations with the standard shell model calculations for the Fe isotopes with the pf-shell interaction GXPF1A [35] using the code kshell [31]. As a detailed example, the Monte Carlo evolution of 56Fe is shown in Fig. 1. During the warm-up period, the total walker number increased rapidly. When the total walker number reaches the preset limit (it is 107 in 56Fe), the shift S starts to vary according to Eq. (8). In the present study, we made a small modification based on those in Ref. [24], which means that we do not apply initiator truncation in the warm-up period, whereas initiator truncation is used in the subsequent periods. With initiator truncation, the total walker number drops temporarily, but increases again. As time progresses, the system reaches equilibrium and the shift S should be stable around the expected ground-state energy. After that, we continued the evolution for a few more steps and performed statistical analysis to extract the ground-state energy. In the 56Fe calculation, we used

The equilibrium walker number and evolution time can vary across systems, and there is no fixed ratio between the equilibrium walker number and the preset warm-up limit. The time required for projection and statistical periods can also vary from system to system. The preset walker number and evolution time can be optimized through a trial run with a smaller walker number and empirical judgment.

Table 1 presents our i-FCIQMC calculations of the Fe isotopes with the GXPF1A interaction benchmarked with the standard shell model calculations with the same interaction. The i-FCIQMC calculations gave almost the same results as the full pf configuration SM calculations, demonstrating the validity of the i-FCIQMC applied to calculations of the nuclear structure. In Table 1, we also show the mean walker number in equilibrium, which is smaller than the dimension of the full configuration SM calculation. Using our current implementation, the i-FCIQMC method achieves these results with a memory requirement that is to 1-2 orders of magnitude smaller than that of the SM calculations.

| isotope | SM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46Fe | 3.1/3.5 | -56.667 | -56.619(21) | -56.643(36) |

| 48Fe | 5.2/5.8 | -91.006 | -90.927(22) | -90.968(40) |

| 50Fe | 6.2/7.2 | -122.878 | -122.668(4) | -122.644(44) |

| 52Fe | 7.2/8.0 | -152.129 | -152.018(2) | -152.004(14) |

| 54Fe | 7.1/8.5 | -175.731 | -175.673(2) | -175.669(6) |

| 56Fe | 7.2/8.7 | -195.900 | -195.802(4) | -195.758(27) |

| 58Fe | 7.2/8.5 | -213.424 | -213.304(3) | -213.303(29) |

| 60Fe | 7.3/8.0 | -228.135 | -228.102(5) | -228.084(14) |

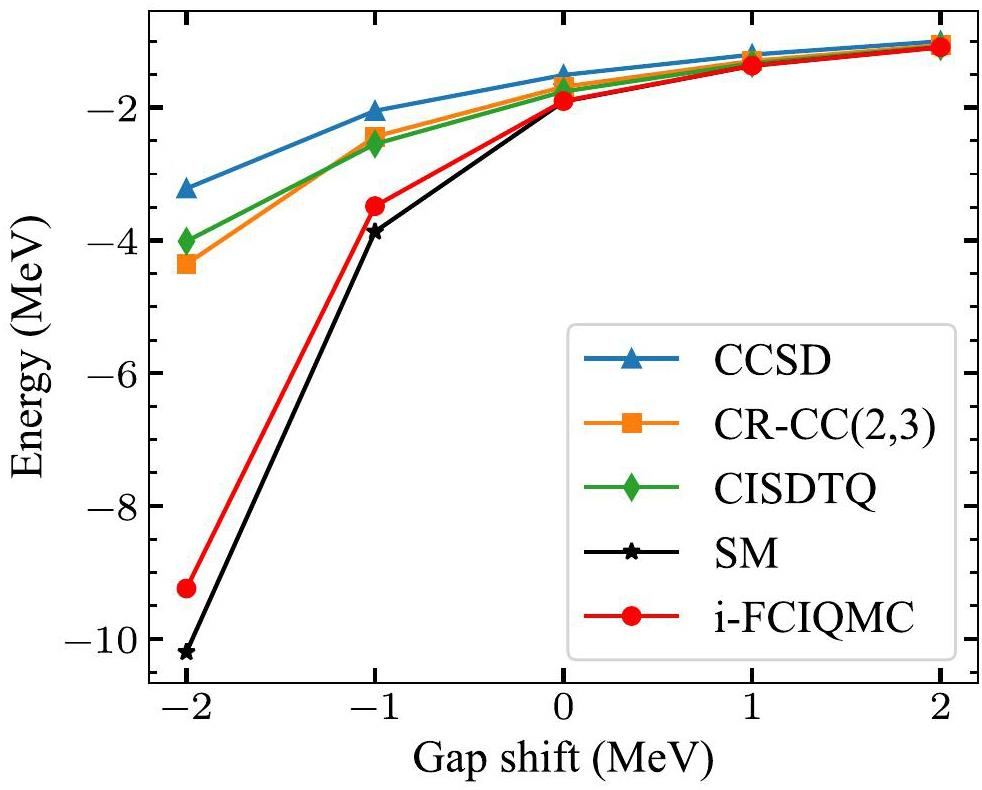

FCIQMC is applicable to strongly correlated systems, whereas other methods do not work well. In Ref. [37], Horoi et al. demonstrated that for a strongly correlated system, the CC calculation may yield significantly unbound energies compared with the full configuration SM calculation. In Ref. [37], the correlations in 56Ni were enhanced by decreasing the shell gap between 0f7/2 and 1p3/2 orbitals. The i-FCIQMC method was applied to the same systems and the results are shown in Fig. 2, along with the results from the CC methods, CISDTQ (configuration interaction singles, doubles, triplets, and quadruples), and full configuration SM. The calculated energies are relative to the reference energy of -203.800 MeV, which is consistent with Ref. [37]. The statistical uncertainties in the i-FCIQMC calculations were negligible and are therefore not displayed in the figure. We used approximately 108 walkers for each state, which is the current limit of our computations.

In the CC methods, the ground state is expressed as

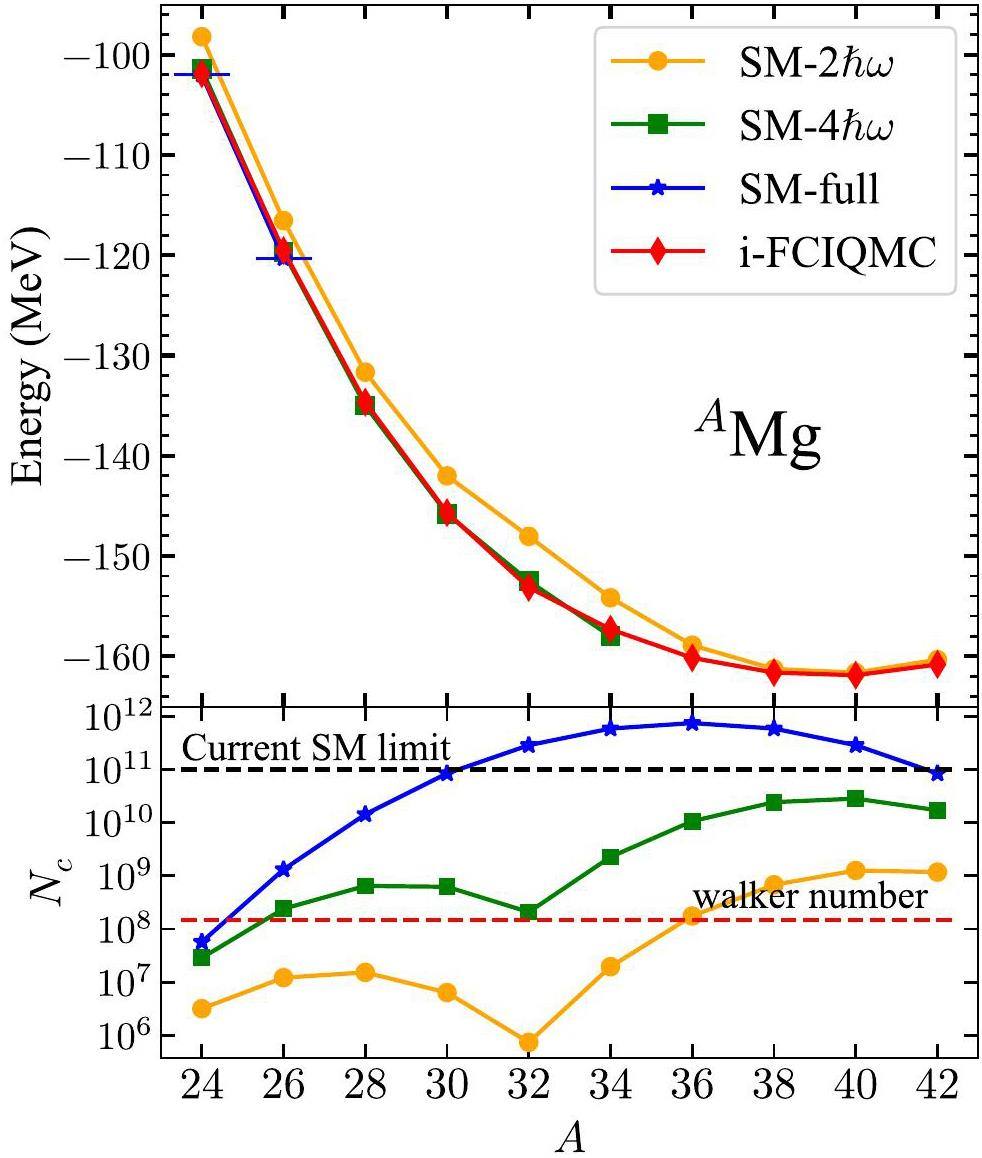

We have went to a larger model space for the sdpf shell. Using the sdpf-mu interaction [40], we calculated Mg isotopes with a total walker number of

In i-FCIQMC calculations with approximately 108 total walker number, only 10-20 GB of memory is required, demonstrating its significant potential for nuclear structure calculations in the configuration space. One of the major challenges in shell model calculations is the prohibitive memory cost in large model spaces. In contrast, i-FCIQMC requires a much smaller configuration space dimension compared to full configuration shell model calculations. Furthermore, unlike shell model calculations, i-FCIQMC does not require storing hundreds of Lanczos vectors, which significantly reduces the memory usage. The current i-FCIQMC implementation is parallelized using OpenMP, and MPI parallelization has been implemented for electron calculations [42]. In the future, we plan to further optimize the code with more efficient parallelization techniques, enabling the calculation of larger total walker numbers.

Summary

In this study, we applied the FCIQMC method to nuclear structure calculations and demonstrated its effectiveness in nuclear many-body systems. According to our code, the original FCIQMC method requires a large total walker number to converge, which makes it impractical for nuclear structure calculations. However, we showed that the initiator FCIQMC method performs well in these calculations.

Our i-FCIQMC computations were benchmarked with full configuration shell model calculations with a focus on Fe isotopes in the pf shell. The results confirmed the validity of our i-FCIQMC computations. For 56Ni, using the shell-gap-shifted GXPF1A interaction, the i-FCIQMC method produced more accurate results than those obtained with Coupled Cluster calculations, highlighting its strength in handling strongly correlated systems. Additionally, we performed large-space calculations for Mg isotopes in the sdpf shell, demonstrating the capability of i-FCIQMC to calculate large-space many-body systems.

Review of quantum Monte Carlo methods and their applications

. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 394, 75-85 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-1280(96)04821-XQuantum Monte Carlo methods for nuclear physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1067-1118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.1067Quantum Monte Carlo Methods in Nuclear Physics: Recent Advances

. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 69, 279-305 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-101918-023600Atomic Nuclei From Quantum Monte Carlo Calculations With Chiral EFT Interactions

. Front. Phys. 8, 117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.00117The shell model as a unified view of nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 427-488 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.77.427Recent progress in configuration interaction shell model

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 32,Recent developments in no-core shell-model calculations

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 36,Ab initio no core shell model

. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 69, 131-181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2012.10.003Realistic effective interactions for nuclear systems

. Physics Reports 261, 125-270 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(95)00012-6Ab initio nuclear many-body perturbation calculations in the Hartree-Fock basis

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Hartree Fock many-body perturbation theory for nuclear ground-states

. Physics Letters B 756, 283-288 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.03.029Ab initio gamow shell-model calculations for dripline nuclei

. Nucl. Tech. 46 (2023). https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2023.hjs.46.080012In-Medium Similarity Renormalization Group For Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106,The In-Medium Similarity Renormalization Group: A novel ab initio method for nuclei

. Physics Reports 621, 165-222 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.12.007Progress in ab initio in-medium similarity renormalization group and coupled-channel method with coupling to the continuum

. NUCL SCI TECH 35, 215 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01585-0Ab initio coupled-cluster approach to nuclear structure with modern nucleon-nucleon interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Coupled-cluster computations of atomic nuclei

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 77,In-medium similarity renormalization group with three-body operators

. Phys. Rev. C 103,In-medium similarity renormalization group with flowing 3-body operators, and approximations thereof

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Fermion Monte Carlo without fixed nodes: A game of life, death, and annihilation in Slater determinant space

. J. Chem. Phys. 131,Full configuration interaction perspective on the homogeneous electron gas

. Phys. Rev. B 85,Towards an exact description of electronic wavefunctions in real solids

. Nature 493, 365-370 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11770Communications: Survival of the fittest: Accelerating convergence in full configuration-interaction quantum Monte Carlo

. The Journal of Chemical Physics 132,Breaking the carbon dimer: The challenges of multiple bond dissociation with full configuration interaction quantum Monte Carlo methods

. The Journal of chemical physics 135,Monte Carlo shell model for atomic nuclei

. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 47, 319-400 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-6410(01)00157-0Benchmarks of the full configuration interaction, Monte Carlo shell model, and no-core full configuration methods

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Configuration-interaction Monte Carlo method and its application to the trapped unitary Fermi gas

. Phys. Rev. A 88,Quantum Monte Carlo calculations in configuration space with three-nucleon forces

. Phys. Rev. C 107,BIGSTICK: A flexible configuration-interaction shell-model code

, http://arxiv.org/abs/1801.08432 (2018)Thick-restart block Lanczos method for large-scale shell-model calculations

. Computer Physics Communications 244, 372-384 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2019.06.011Emergence of Critical Phenomena in Full Configuration Interaction Quantum Monte Carlo

, arXiv:1209.4023 [cond-mat, physics:physics] (2012)Semi-stochastic full configuration interaction quantum Monte Carlo: Developments and application

. The Journal of Chemical Physics 142,An excited-state approach within full configuration interaction quantum Monte Carlo

. J. Chem. Phys. 143,Shell-model description of neutron-rich pf-shell nuclei with a new effective interaction GXPF 1

. Eur. Phys. J. A 25, 499-502 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjad/i2005-06-032-2Error estimates on averages of correlated data

. J. Chem. Phys. 91, 7 (1989)Coupled-Cluster and Configuration-Interaction Calculations for Heavy Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,Single-reference, size-extensive, non-iterative coupled-cluster approaches to bond breaking and biradicals

. Chemical Physics Letters 418, 467-474 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2005.10.116Two new classes of non-iterative coupled-cluster methods derived from the method of moments of coupled-cluster equations

. Molecular Physics 104, 2149-2172 (2006), publisher: Taylor & Francis _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/00268970600659586.Shape transitions in exotic Si and S isotopes and tensor-force-driven Jahn-Teller effect

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Ground-state properties of light 4 n self-conjugate nuclei in ab initio no-core Monte Carlo shell model calculations with nonlocal N N interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Linear-scaling and parallelisable algorithms for stochastic quantum chemistry

. Molecular Physics 112, 1855-1869 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/00268976.2013.877165Fu-Rong Xu is an editorial board member/editor-in-chief for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.