Introduction

Unlike power reactors, which are utilized to provide electricity, heat, propulsion, etc., research reactors [1, 2] are primarily used for scientific research, engineering tests, or other utilization potentials using neutrons, gamma, or other radiations [3-5]. The neutron flux is one of the most important parameters of a research reactor. Research reactors with the neutron flux 1014–1015 n/(cm2·s) or higher are commonly categorized as high flux reactors (HFRs) [6]. Notably, although pulsing reactors and pulsating reactors can provide these neutron flux values on a certain time scale, for instance, IBR-2 can provide an average fast neutron flux of 2.26×1017 n/(cm2·s) [7], they are beyond the range of the research reactors providing stable neutron fluxes as we discussed.

Compared with other research reactors, HFRs are designed with certain technical features to achieve a much higher level of fast or thermal neutron intensity, which plays an important role in the investigations of new fuel elements and materials science, theoretical and applied physics research, and production of rare isotopes. Testing materials for nuclear energy applications, fundamental physics research, and the production of industrial and medical isotopes are indispensable for high-level neutron fluxes. Based on these requirements, HFRs with one or more of these functions have been designed and constructed in different countries.

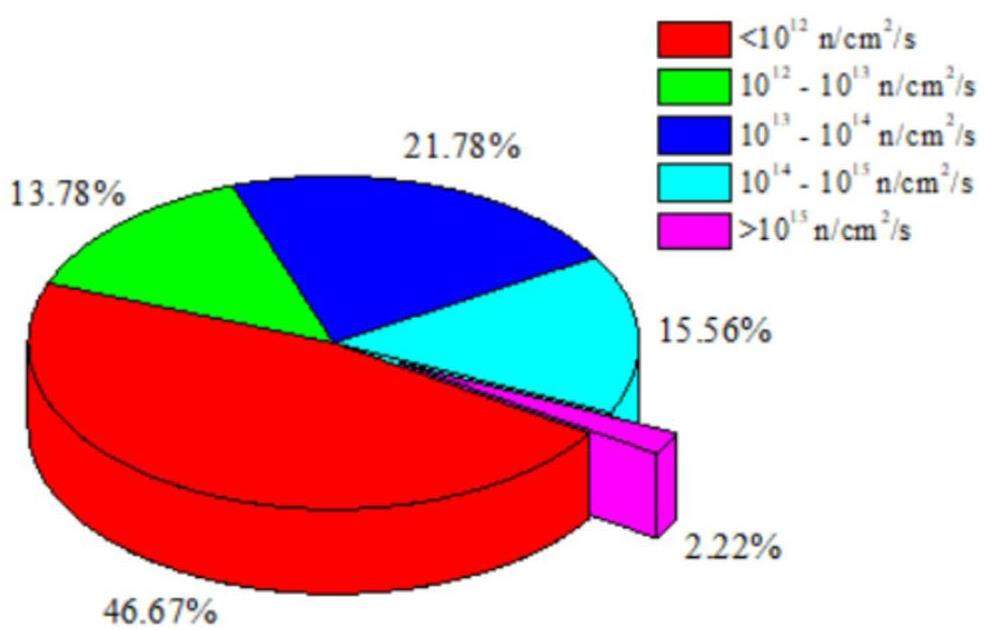

According to statistics related to research reactors on the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) website [8], 840 research reactors are distributed across 70 countries and regions worldwide. As shown in Table 1, most existing research reactors are being decommissioned or have already been decommissioned, and only 225 research reactors are operating. Presently, the country with the largest number of operational research reactors (including criticality experimental devices) is Russia (54 reactors), followed by USA (49 reactors), China (17 reactors), India (5 reactors), Germany (5 reactors), and Canada (4 reactors). Research reactors used worldwide are summarized in Fig. 1. Among of them, 40 (a proportion of 17.8%) have neutron fluxes higher than 1014 n/(cm2·s), which can be categorized into the scope of HFRs.

| Reactor status | Reactor number | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Operational | 226 | 54 |

| Under construction / Planned | 20 | 15 |

| Temporary /Extended / Permanent shutdown | 74 | 29 |

| Under decommissioning / Decommissioned | 520 | 37 |

| Total | 840 | - |

Most operational HFRs were built 50 years ago and face problems such as aging and decommissioning. Therefore, new and advanced HFRs must be developed in the near future. This paper reviews HFRs, including their historical development, technical features, and application areas. Therefore, we attempted to determine the future trend for developing new-generation HFRs.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the development history of HFRs. The technical features of HFRs, including the reactor core design, irradiation capability, and operating characteristics, are analyzed and summarized in Sect. 3. The main applications of HFRs are discussed in Sect. 4. Finally, the future trends for HFRs are discussed.

Historical development of high flux reactors

After the first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile 1 (CP-1), achieved its first criticality in 1942, humanity entered a new era of nuclear energy. In 1943, a CP-1 reactor, called CP-2, was reconstructed, which was fueled with natural uranium and moderated by graphite. The normal maximum power of CP-2 was 1 kW, and it could also operate at 5 or 10 kW for short periods in certain experiments [1]. CP-2 was considered the first research reactor, and early experiments performed in this reactor supported the development of subsequent reactors. Early research reactors included X-10, CP-3, LOPO, and HYPO [2]. These research reactors have been used to conduct extensive experimental programs related to reactor prototype design and the operating characteristics of this type of reactor. The operating power of these research reactors is typically in kW to MW range, with a low neutron flux.

With the development of nuclear energy, the demand for higher neutron fluxes for material testing and other applications gradually increased. In 1952, the Material Testing Reactor (MTR) [9], a research reactor in the United States, became critical. The power of this reactor was 40 MW with an average thermal neutron flux of 3×1014 n/(cm2·s). Based on the neutron flux level achieved by the MTR, this was the first true HFR.

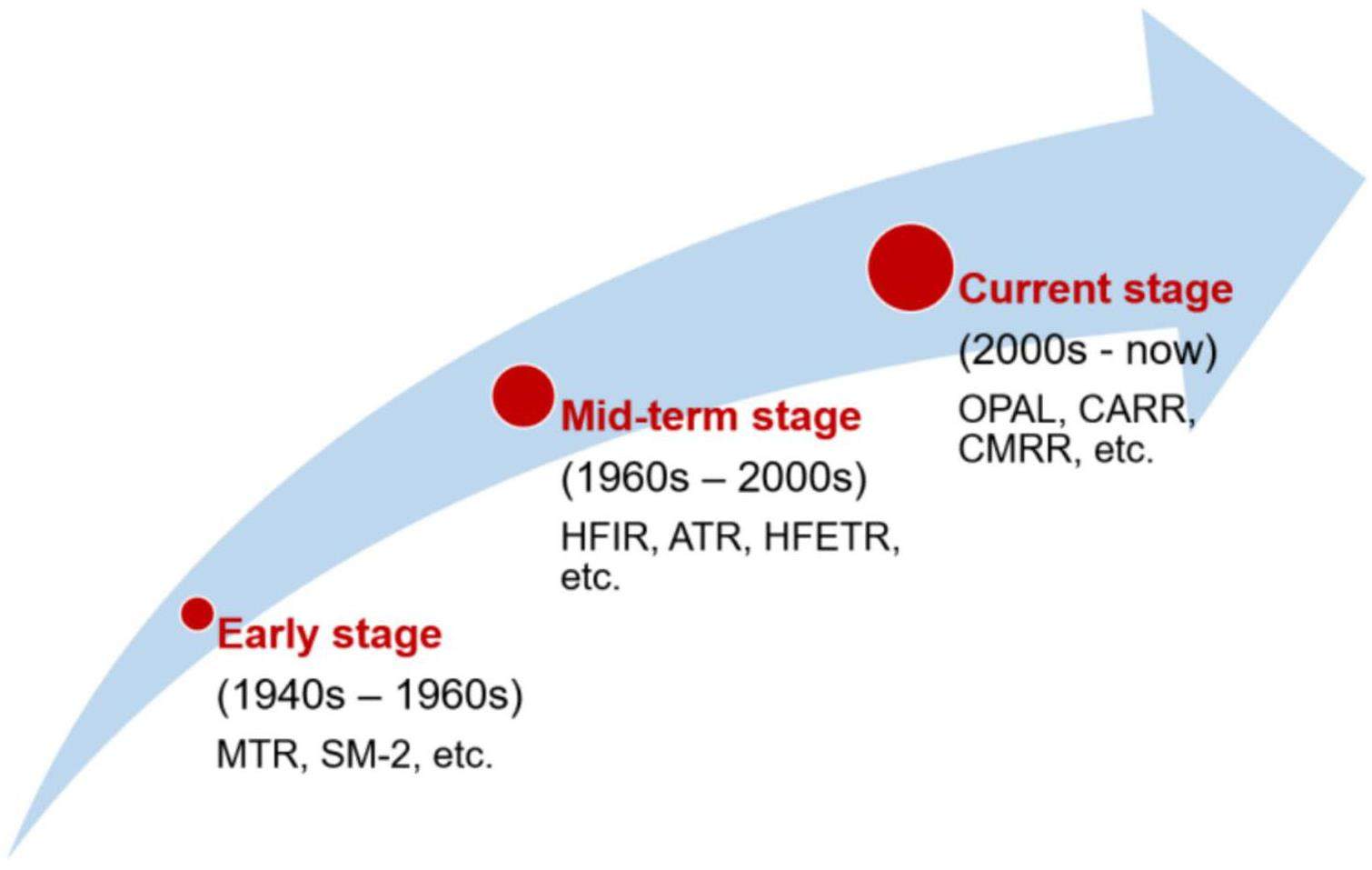

In the following decades, multiple HFRs were designed and constructed, including SM [10], High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) [11], Advanced Test Reactor (ATR) [12], High Flux Engineering Test Reactor (HFETR) [13], China Advanced Research Reactor (CARR) [14], and Open Pool Australian Light-water reactor (OPAL) [15]. Based on the technical development and advanced level, the historical development of the HFR can be roughly divided into the early stage (1940s–1960s), mid-term stage (1960s–2000s), and current stage (from the 2000s to present), as shown in Fig. 2.

The representative HFRs in different stages are summarized in Table 2 [2, 8, 16-24], which includes their power level, reactor type, status, fuel assembly, neutron flux, first criticality time, and estimated decommission time.

| Stage | Reactor | Country | Power (MWt) | Reactor type | Reactor status | Fuel assembly | Max. thermal neutron flux [n/(cm2·s)] | Max. fast neutron flux, n/(cm2·s) | Max. total neutron flux [n/(cm2·s)] | First criticality time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early stage | MTR | USA | 40 | tank type | decommissioned | HEU U-Al | 4.8×1014 | 5.3×1014 | - | 1952 |

| LVR-15 | Czech | 10 | tank type | operational | - | 1.5×1014 | 3.0×1014 | - | 1957 | |

| SM-2 | Soviet Union | 100 | vessel type | update to SM-3 | HEU UO2 | 5.0×1015 | - | - | 1961 | |

| Mid-term stage | HFR | Netherlands | 45 | tank-in-pool | operational | - | 2.7×1014 | 5.1×1014 | - | 1961 |

| BR-2 | Belgium | 100 | tank-in-pool | operational | HEU UAlx | 1.0×1015 | 7.0×1014 | - | 1961 | |

| HFIR | USA | 85 | tank type | operational | HEU U3O8-Al | 2.5×1015 | 1.0×1015 | 5.6×1015 | 1965 | |

| SAFARI-1 | South Africa | 20 | tank-in-pool | operational | - | 2.4×1014 | 2.8×1014 | - | 1965 | |

| ATR | USA | 250 | tank type | operational | HEU UAlx | 8.5×1014 | 1.8×1014 | 2.75×1015 | 1967 | |

| MIR | Soviet Union, Russia | 100 | pool/channels | operational | HEU UO2 | 5.0×1014 | 1.0×1014 | - | 1967 | |

| JMTR | Japan | 50 | tank | operational | LEU U3Si2-Al | 4.0×1014 | 4.0×1014 | 1.4×1015 | 1968 | |

| BOR-60 | Soviet Union, Russia | 60 | fast breeder | operational | UO2 - PuO2 | 2.0×1014 | 3.7×1015 | - | 1969 | |

| MARIA | Poland | 30 | pool type | operational | LEU U3Si2-Al, UO2-Al | 3.5×1014 | 1.0×1014 | - | 1974 | |

| HFETR | China | 125 | vessel type | operational | LEU U3Si2-Al | 6.2×1014 | 1.7×1015 | 2.3×1015 | 1979 | |

| SM-3 | Russia | 100 | pressure vessel | operational | HEU UO2 | 5.0×1015 | 2.0×1015 | - | 1992 | |

| Current stage | FRM-Ⅱ | Germany | 20 | pool type | temporary shutdown | U3Si2-Al | 8.0×1014 | 5.0×1014 | - | 2004 |

| OPAL | Australia | 20 | pool type | operational | U3Si2-Al | 2.0×1014 | 2.1×1014 | 5.0×1014 | 2006 | |

| CARR | China | 60 | tank-in-pool | operational | U3Si2-Al | 8.0×1014 | 6.0×1014 | 1.6×1015 | 2010 | |

| CMRR | China | 20 | pool type | operational | U3Si2-Al | 2.4×1014 | 3.7×1014 | - | 2013 | |

| RJH | France | 100 | pool type | under construction | U3Si2-Al | 5.5×1014 | 5.0×1014 | - | - | |

| MBIR | Russia | 150 | fast, power | under construction | MOX | - | 5.3×1015 | - | - | |

| VTR | USA | 300 | sodium cooled fast reactor | planned | metallic alloy fuel (HALEU, LEU+Pu, DU-Pu) | - | 4.0×1015 (E>0.1MeV) | 5.0×1015 | - |

In this section, the historical development of HFRs worldwide is described.

Early stage

The development of the HFR in the early stages spanned from the 1940s to the 1960s, and typical representatives include the MTR and SM-2. During this period, HFRs underwent significant technological improvements based on typical research reactors to achieve higher neutron fluxes and broader applications, such as the MTR-type fuel assembly and the method of obtaining ultra-high neutron flux in the reactor core.

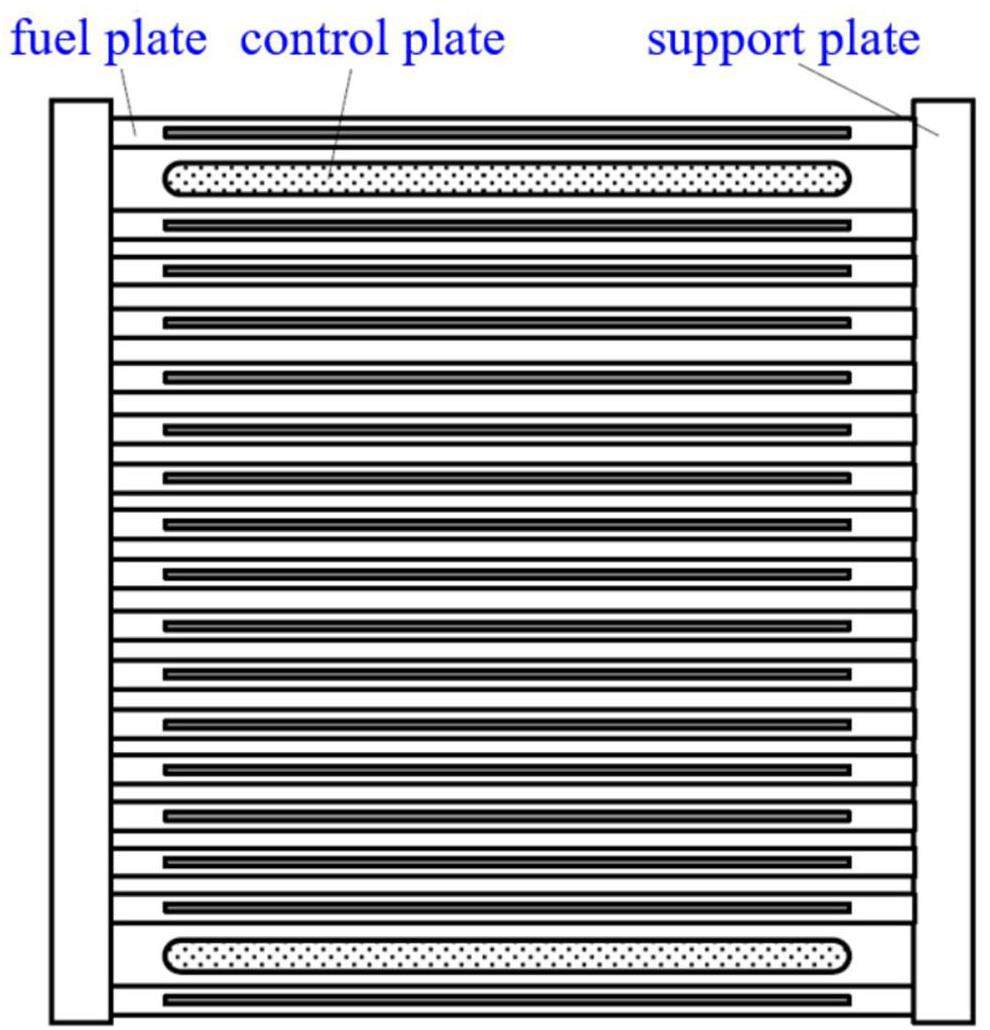

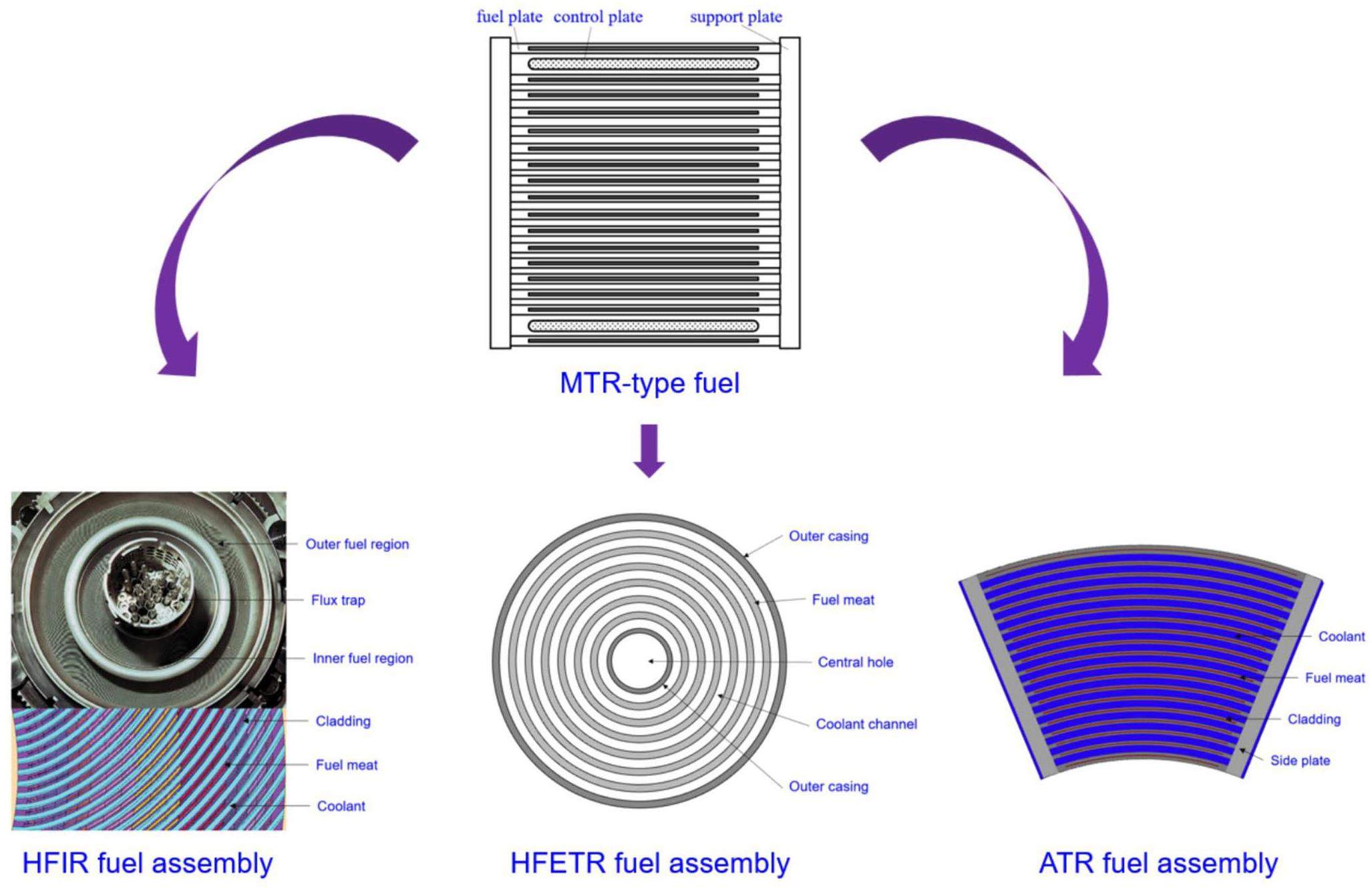

The design of MTR started in 1944 at the Oak Ridge National Lab (ORNL), USA, and was primarily used to satisfy the requirements of higher neutron flux in material irradiation tests. MTR achieved its first criticality on March 31, 1952. The reactor’s thermal power was 30 MW, and a highly enriched uranium (HEU) fuel was adopted. This reactor was cooled and moderated with light water, and beryllium and graphite were used as reflectors. The operating power of this reactor was increased to 40 MW in 1955 resulting in an average thermal neutron flux of 3×1014 n/(cm2·s), which maintained the highest neutron flux for many years. Plate fuel assemblies were utilized to permit a higher power density and sufficient cooling. This type of fuel consists of an aluminum–uranium mixture with aluminum as the cladding and is called an MTR-type reactor fuel [25]. The MTR-type fuel has a profound impact on the development of research reactor fuel assemblies, and many fuel assemblies used in later HFRs, such as CARR and JRR-3M, are based on this design scheme. A cross-sectional view of the MTR-type fuel assembly is depicted in Fig. 3. The irradiation application design of MTR was also flexible, with over 100 irradiation positions and six neutron beam tubes in the horizontal direction.

The SM-2 reactor [2, 22] was the first epithermal neutron spectrum research reactor with water as a moderator. It was a vessel HFR in the Soviet Union with a power of 100 MW. SM-2 had 15 vertical channels for radiation resistance testing, four vertical high-temperature channels for corrosion resistance testing, six vertical channels for the accumulation of transuranic elements and radioisotopes, and five horizontal channels. The construction of SM-2 began in January 1956 and achieved its first criticality on January 10, 1961. The power density of SM-2 was extremely high (the estimated average value was 2×103 MW/m3); therefore, an ultrahigh neutron flux was achieved in the in-core irradiation channels. At that time, the thermal neutron flux in SM-2 was 3.3×1015 n/(cm2·s) and thermal power was 50 MW. The construction of the SM-2 reactor and its successful operation motivated the construction of HFRs in the United States for hard neutron spectrum High Flux Beam Reactor (HFBR) and HFIR. The SM-2 reactor was characterized by the following features in its early design: high volumetric inhomogeneity coefficients (~6), deep reactivity losses owing to Xe-135 poisoning (> 4%), and significant burnup reactivity temperature losses. In 1965, the fuel element of SM-2 was changed from plate fuel to cruciform fuel. In 1974, the thermal neutron flux in the neutron flux trap was improved to 5.0×1015 n/(cm2·s), when the nominal thermal power was increased to 100 MW. From 1984 to 1987, the horizontal channel of the reactor was "closed." SM-2 was finally inherited by Russia and updated to SM-3 in 1991–1992, as discussed later.

Mid-term stage

The mid-term development stage of HFRs refers to the period from the 1960s to the 2000s. During this period, the HFR technology matured. Several high flux research reactors were successively built, including the ATR, HFIR, and HFETR.

Although MTR has consistently provided a high neutron flux, the pursuit of a higher neutron flux continued. Based on this background, an improved test reactor design effort began in 1955. The power level was increased; therefore, the neutron flux in the irradiation test position was higher, and experimental loops were installed for fuel irradiation. The new test reactor was called ETR, which was later renamed ATR [12]. The critical device of ATR (ATRC) went to its first criticality in 1964, and ATR was put into operation in 1967. ATR has a maximum power of 250 MW, and the maximum thermal and fast neutron flux are 1.0×1015 n/(cm2·s) (E < 0.625 eV) and 5.0×1014 n/(cm2·s) (E > 1 MeV), respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, arc-type fuel assemblies fabricated from UAlx fuel meat with HEU (90 wt%) were adopted, and the reactor core comprises 40 fuel assemblies. In contrast to the widely used control rods in other HFRs, rotation control drums were adopted by ATR [26], which aided in forming a relatively uniform axial power distribution. Nine neutron flux traps are enclosed by fuel assemblies in the reactor core, and a total of 77 irradiation channels with a diameter of 1.59–12.7 cm are distributed in the reactor.

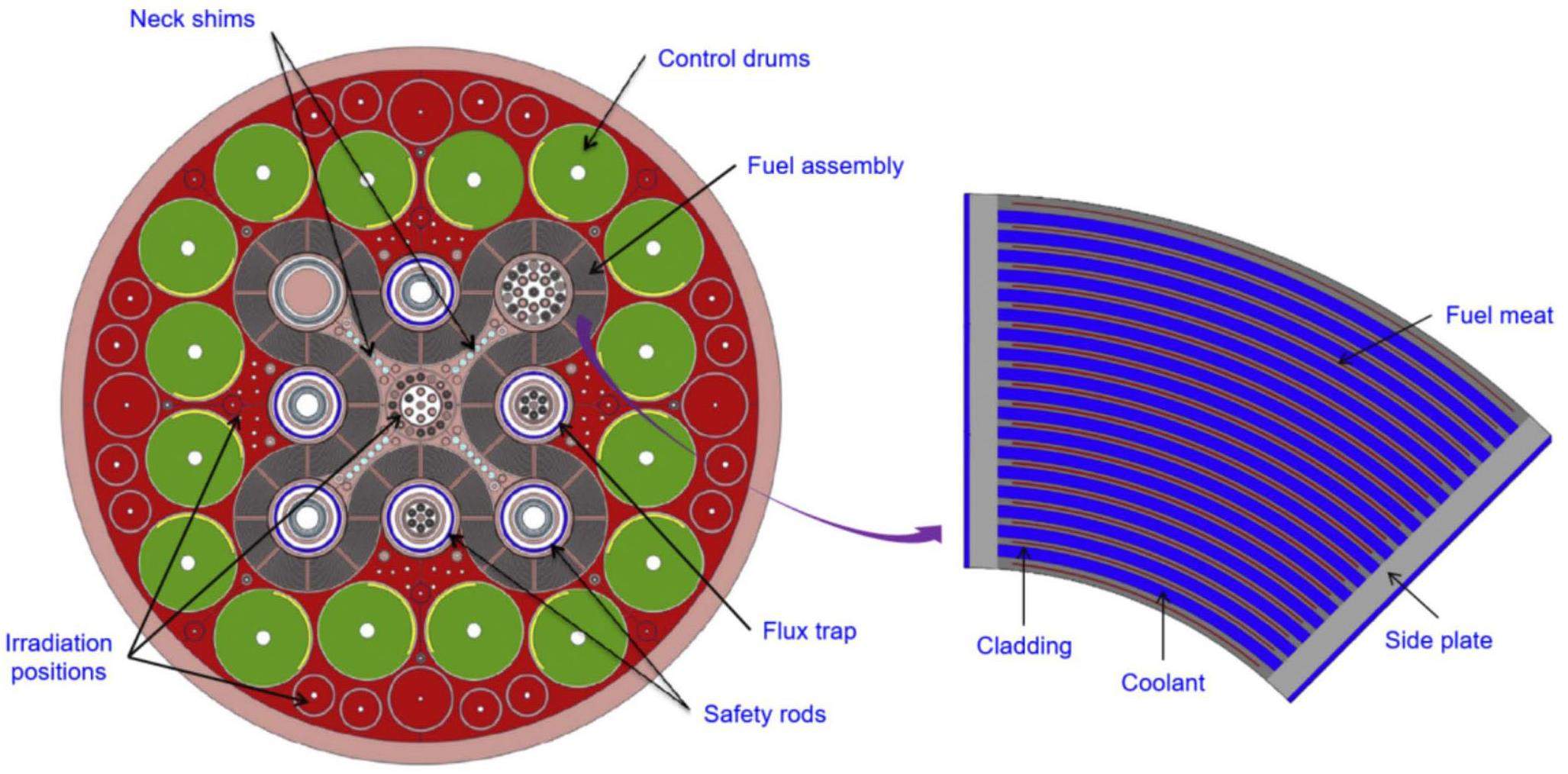

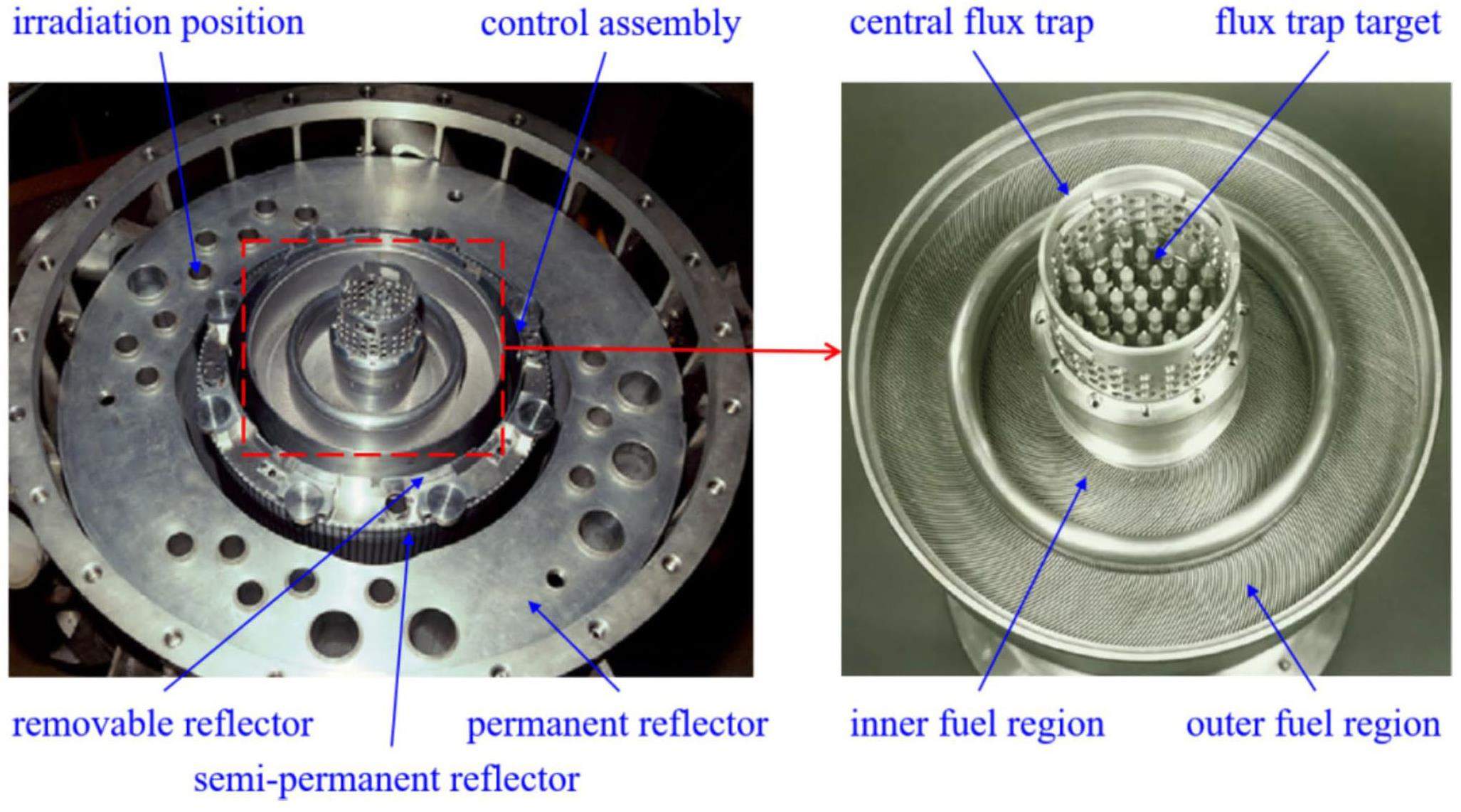

HFIR [27, 28] was founded in 1961 and reached its first criticality on August 25, 1965. A full-power operation was achieved in September 1966. The initial motivation for constructing HFIR was to generate significant and weighable quantities of heavy elements (Cm, Bk, Cf, Es, Fm, etc.), particularly 252Cf, to support the fundamental research and application of transplutonium elements. Therefore, a research reactor with an extremely high neutron flux was required, which is beneficial for accelerating the production efficiency of transplutonium nuclides, producing radioisotopes with high specific activity, and conducting material tests. HFIR is a light-water-cooled and moderated HFR with a rated power of 125 MW. As shown in Fig. 5, the reactor core consists of a series of concentric fuels, and the fuel region is divided into inner and outer fuel zones. A flux trap is located in the center of the reactor core, and the maximum total neutron flux achieves 5×1015 n/(cm2·s), which provides basic conditions for the production of transplutonium isotopes. In addition, various irradiation targets can be installed in the beryllium reflector, and four horizontal neutron beams can be used for neutron scattering and imaging.

HFETR [13, 28] is a versatile HFR in China, which is a vessel reactor with a design power of 125 MW. The reactor is composed of U3Si2-Al dispersion fuels and is cooled and moderated using light water. HFETR has the characteristics of high neutron flux, flexible reactor core layout, large irradiation space, and short irradiation period. The maximum thermal neutron flux is 6.2×1014 n/(cm2·s) (E < 0.625 eV), and the maximum fast neutron flux is 1.7×1015 n/(cm2·s) (E > 0.625 eV). The construction of this reactor, which was initiated in 1971, achieved its first criticality in 1979, and started high-power operation in 1980. In 2007, the transformation of HEU fuel into low enrichment uranium (LEU) fuel was completed for the HFETR [29], and 235U enrichment decreased from 90 wt% to 19.75 wt%. Over the past few decades, HFETR has continued to conduct irradiation research on fuel and materials for power reactors and radioisotope production for industrial and medical applications. This reactor is expected to be operational until 2028.

SM-2 was reconstructed and updated to SM-3 [22] between 1991 and 1992. The physical startup of SM-3 was conducted in December 1992 and the power startup in April 1993. This reconstruction project set the lifespan at 25 years. SM-3 removed the horizontal channels and added additional vertical experimental channels, including one central neutron flux trap, six channels in the active core, and 30 channels in the reflector. The maximum thermal neutron flux in SM-3 is 5.0×1015 n/(cm2·s) (E < 0.625 eV), which occurs in the central flux trap of the reactor core, and the maximum fast neutron flux is approximately 2.0×1015 n/(cm2·s) (E > 0.1 MeV). This reactor is primarily used for transplutonium nuclide production (10–25 mg 252Cf per year), nuclear fuel production, and material testing. From 2017 to 2020, a modernization update [30] on SM-3 was conducted, including the replacement of reactor internal structures, digital control, and protection systems, with an expected lifespan extension until 2040.

Current stage

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the development of nuclear energy and technology in various countries has increased the demand for HFRs. Several innovative HFRs, such as OPAL and CARR, have been designed and constructed. In addition, several HFRs have been planned and are being constructed for multipurpose applications.

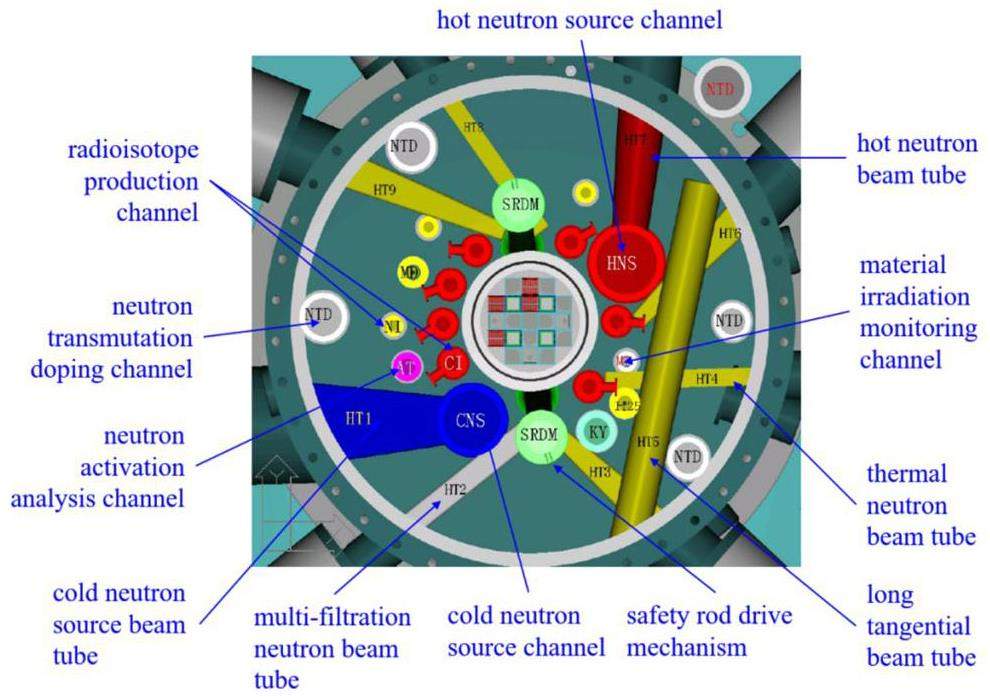

CARR [14] is an HFR with satisfactory performance and multiple applications. This reactor reached its first criticality in May 2010 and entered full-power operation in 2012. CARR is a tank-in-pool reactor enclosed by a slightly pressurized aluminum container and submerged in the reactor pool. With this structure, the reactor core would not be exposed, even under accident conditions. A cross-sectional view of the reactor core and surrounding reflector is shown in Fig. 6. The nominal operating power of CARR is 60 MW, and the reactor core is loaded with 21 fuel assemblies, using a U3Si2-Al dispersed fuel plate. The reactor is light-water-cooled and moderated, and a heavy-water tank is used as a reflector. It contains 25 vertical and 9 horizontal irradiation channels, which are almost entirely located in the reflector. Only a few channels are arranged near the boundary of the aluminum container in the reactor core. Applications of CARR include fuel and material irradiation tests, radioisotope production, neutron scattering and imaging, and neutron activation analyses.

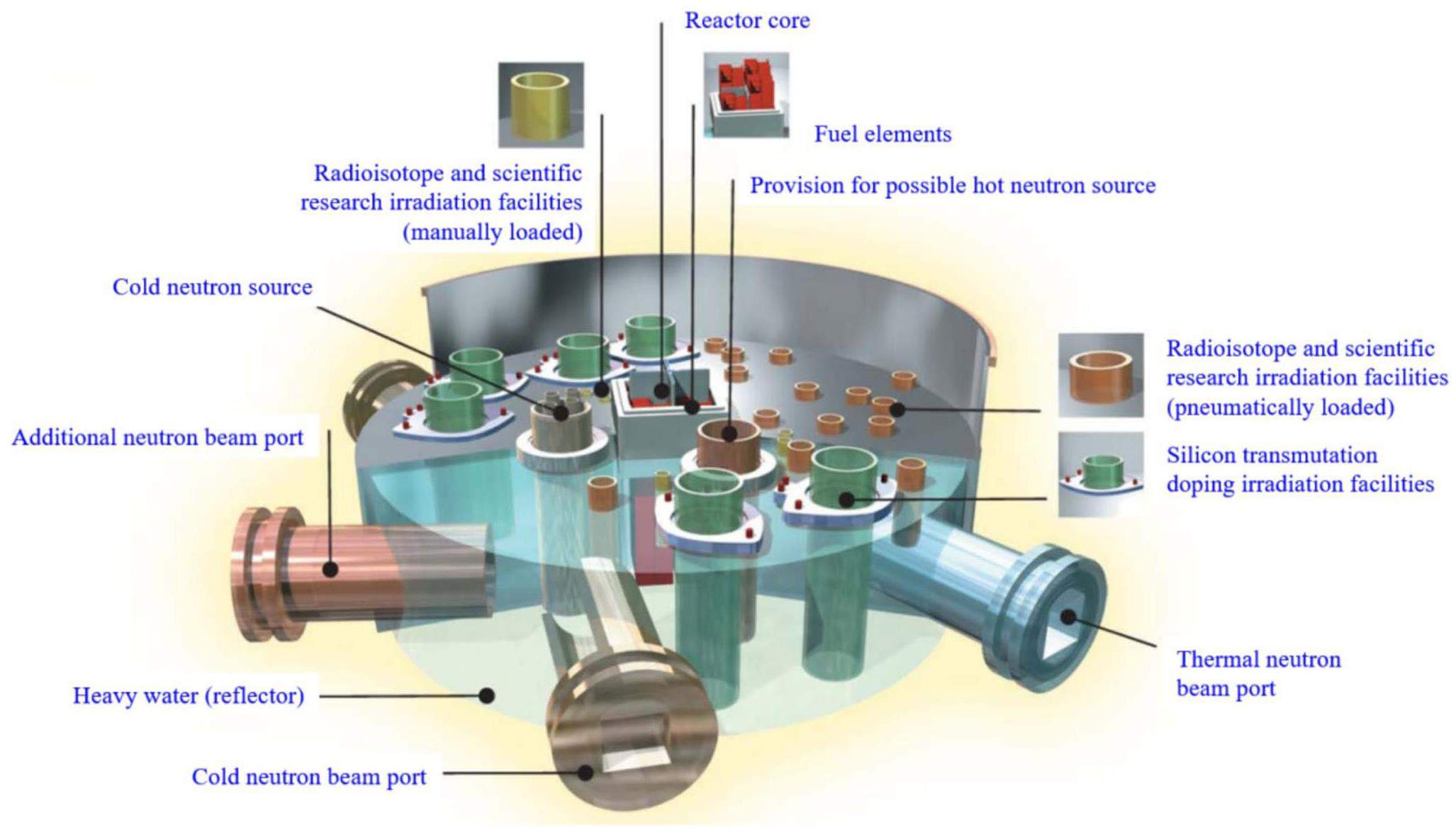

OPAL [15] is an open-pool HFR in Australia that achieved its first criticality on August 12, 2006. The nominal power is 20 MW, and a low enriched U3Si2-Al dispersion plate fuel is adopted with aluminum as the cladding. The reactor core is cooled and moderated using light water and surrounded by a heavy-water reflector. The maximum thermal neutron flux is 3.0×1014 n/(cm2·s) which appears in the irradiation position in the reflector, and the maximum fast neutron flux is 2.0×1014 n/(cm2·s). The reactor pool is connected to the service pool through a transfer canal. The layout of the reactor core and irradiation channel in the OPAL is shown in Fig. 7. Since its establishment, OPAL has become an important supplier of medical and industrial radioisotopes (such as 99Mo, 99mTc, 131I, 153Sm, 51Cr, etc.), a crucial testing platform for materials science and research, and a service provider for silicon transmutation doping [31].

The Jules–Horowitz Reactor (JHR) [32, 33] is a new HFR under construction in France. The nominal design power of the vessel-in-pool reactor is 100 MW. The reactor is fueled by cylindrical U3Si2-Al assemblies. The reactor core is cooled using light water in a slightly pressurized primary circuit, and a beryllium reflector is used. The reactor core and reflector also provide sufficient irradiation positions for fuel and material irradiation tests, offering instrumented and circuit irradiation test capabilities. The expected fast neutron flux in the irradiation position is 5.5×1014 n/(cm2·s) with energy above 1 MeV, corresponding to a radiation damage of 16 dpa per year. JHR also enables a high thermal neutron flux in the irradiation position, which can be used for radioisotope production. The reactor is planned to operate after 2030 and will enhance the irradiation research capability of fuel and materials in France and Europe.

To support the development of advanced fast reactors [34] in the scope of fourth-generation nuclear energy systems, USA, Russia, and China planned to build a new HFR with fast neutron spectra. Most of these are designed as liquid-metal fast reactors [23]. The Multi-Purpose Fast Research Reactor (MBIR) [35], designed by Russia, is a loop versatile high flux fast neutron reactor with an asymmetric active zone layout. The maximum neutron flux of MBIR can reach 5.3×1015 n/(cm2·s). Three experimental loops, three loop channels, and 14 material science assemblies are installed in the reactor. MBIR is designed to perform irradiation tests with Pb, Pb-Bi, Na, He, and molten salt, which can fulfill the development requirements of sodium fast-cooled and molten salt reactors. The designed lifespan of MBIR is 50 years, and it is expected to achieve its first criticality and operate by 2028. The Versatile Test Reactor (VTR) [24, 36] in USA is another high flux fast reactor with a power of 300 MW and a maximum neutron flux of 4.5×1015 n/(cm2·s). High flux fast neutron reactors typically utilize sodium metal or lead-bismuth alloys as coolants. In China, a concept of ultra-high flux fast neutron reactor (UFFR) [37] has been proposed to achieve a maximum neutron flux of 1016 n/(cm2·s) level.

Recently, the Tsinghua High Flux Reactor (THFR) was designed by Tsinghua University, China. THFR is a light-water-cooled reactor with good safety characteristics. Its maximum neutron flux achieves 5.7×1015 n/(cm2·s), and both of its thermal and fast flux can achieve 2.0×1015 n/(cm2·s), which is expected to provide a wide range of applications.

Design features of the high flux reactor

HFRs have technical features that differ from those of power reactors and other types of reactors. It not only includes a series of measures adopted to achieve sufficiently intensive neutron fluxes but also involves special technologies to improve irradiation capability, operational flexibility, and safety. In this section, the technical features of HFRs are analyzed in terms of reactor core design, irradiation capability, and operating characteristics.

Reactor core design

Reactor physics and thermal-hydraulic design

The fundamental design requirement of an HFR is to provide the necessary neutron flux conditions to irradiate samples at the lowest possible power and economic cost. To describe the law of realization of a high neutron flux using a homogeneous reactor as an example, the total neutron flux can be described as

Noting that the fission cross section is generally smaller in the fast energy range than in the thermal energy range, the total neutron flux is expected to improve if fission events are dominated by fast neutrons. However, moderated neutrons can contribute to reducing the critical fuel loading. These two contradictory aspects should be considered when designing HFRs.

Several HFRs adopt the design concept of inverse-neutron flux traps [38]. The reactor core is compact and undermoderated, and fast neutrons leak into the surrounding reflector area and are moderated such that a high thermal neutron flux is obtained in the reflector. The determination of the thermal neutron flux level depends on the objective of the study. In the example of the 244Cm production through the transmutation of 242Pu, the "bottleneck" for transmutation is the transition from 242Pu to 243Pu. When the characteristic burnup time is set as 1/(Φσc) ≤ 0.5 year, the neutron flux should be Φ ≥ 1/(σc×0.5 year) = 3.4×1015 n/(cm2·s).

An increase in the power density qV directly results in a higher neutron flux. For the thermal-hydraulic design, the heat released from fuel assemblies is a burden that significantly increases the cost of loop cooling. The main methods of increasing the allowed qV are to reduce the coolant temperature at the core inlet, increase the coolant velocity, and expand the heat exchange surface by using fuel elements with thin shapes, such as plates.

The first loop pressure of the HFR is significantly lower than that of the power reactor. For example, the operation pressure of SM-3 is 4.9 MPa [22]. On one hand, a relatively low pressure ensures that the experimental setup is under acceptable operating conditions; on the other hand, increasing the pressure increases the subcooling margin, delays the critical boiling transition, and promotes the growth of qV. In addition, a lower inlet temperature enables the coolant temperature to move further away from the melting point of the fuel cladding. The compromise results are that the subcooling margin is 70 to 200 ℃ and the coolant temperature in first loop does not exceed 100 ℃.

The coolant velocity is significantly higher than that of the power reactor. For example, the maximum of this value in SM-3 is 13.5 m/s [22] and in the HFIR is 15.5 m/s [11]. A high coolant velocity enhances the heat transfer between the coolant and cladding surface; however, it is primarily limited by flow-induced vibrations, thermal stresses on the cladding, and surface corrosion and erosion. The channels between plate-form fuels are generally narrow, and small disturbances during the flow produce reciprocal movements at high flow rates. On one hand, it increases the risk of fuel meltdown owing to deformation; on the other hand, the alternating deformation increases the fatigue of the fuel. Furthermore, the increased coolant velocity results in a more intensive dissolution of the active substances in the coolant towards the surface and tears off a part of the corrosion film from the surface, i.e., corrosion and erosion of the fuel cladding. Notably, owing to the high heat flow density, the oxide layer of the aluminum cladding dominates the non-negligible temperature margin. The thickness of the oxide layer increases progressively with prolonged operation, limiting the operating time of the reactor.

In summary, to determine the maximum qV of the designed HFR, the following aspects must be considered:

1) fuel element structure and heat transfer parameters;

2) determination of heat transfer conditions and critical heat flux;

3) temperature stresses at high energy densities per volume of the fuel element;

4) stability at high coolant velocities;

5) limitations imposed by corrosion and erosion on the fuel cladding.

Reactor body structure

The reactor body structure refers to the basic configuration of the reactor core, pressure vessel, reactor pool, and other reactor-affiliated facilities. The reactor body structure of an HFR can be roughly divided into three forms: pool, vessel (or tank), and vessel-in-pool (or tank-in-pool). The difference between the above reactor structures mostly lies in two aspects: whether the reactor core is enclosed in a pressure vessel (or other pressurized containers), and whether the reactor core vessel is submerged in a reactor pool. The pressurized vessel or tank aids in improving the reactor operating pressure, which enables a larger reactor core power density and thus a higher neutron flux. A reactor pool filled with water increases the reactor safety and facilitates convenient operation with irradiation targets and other test samples.

The open pool reactor structure is widely used, such as for MJTR and OPAL. For CARR, based on the pool reactor design scheme, the reactor core is contained in a slightly pressurized tank fabricated from aluminum. ATR and HFETR are vessel HFRs, whereas HFIR is a representative vessel-in-pool reactor, and the operating pressure is typically 2–3 MPa. The basic structure of a vessel-in-pool reactor improves the neutron flux level with satisfactory safety features, which is preferable for ultra-high-flux reactors. The design concept of inverse-neutron flux traps is typically adopted for pool HFR [38]. The reactor core is compact and undermoderated, and fast neutrons leak into the surrounding reflector area and are moderated such that a high thermal neutron flux is obtained in the reflector.

A pressure vessel is an important device that serves as a second safety barrier to prevent the leakage of radioactive materials. It also provides support and positioning for the internal structure of the reactor. Pressure vessels are typically made of austenitic stainless steel (such as 316LN), which has a higher toughness at various temperatures.

Fuel assembly

HFR systems are simpler than power reactors, and they typically operate at lower temperatures. The uranium fuel loading of an HFR is significantly lower than that of a power reactor. An HFR typically requires only a few kilograms of nuclear fuel. For example, the total 235U loading in the HFIR core is 9.4 kg.

However, HFR fuel assemblies may require uranium with a high enrichment of 20 wt% or higher. Historically, many HFRs used HEU fuels with enrichment higher than 90 wt%, such as HFIR, ATR, and SM-3. With HEU fuels, the absorption of 238U and other reactor core materials can be minimized, resulting in a more compact reactor core structure and a longer operating period. In addition, the utilization of HEU can significantly reduce the costs of HFRs, including fuel and construction costs. Although the unit price of natural uranium is lower than that of HEU (by approximately one-third), reactors using natural uranium require a much higher power increase to achieve the same neutron flux level as reactors using HEU, resulting in a much higher fuel burnup. In addition, the cost of the first fuel load must be considered. Based on an analysis by Bath [2], 235U contained in 1 t of natural uranium is about 30 times more expensive than 10 kg of HEU. Furthermore, the cost per unit mass of 235U increases significantly when enrichment exceeds 90%. Therefore, the Soviet Union used 90 wt% HEU, whereas the United States used 93 wt% HEU. Under the Reduced Enrichment for Research and Test Reactors (RERTR) [39] proposed in the 1970s, many HFRs were converted from HEU fuels to LEU fuels. In the HFETR, a U3Si2-Al dispersion fuel with an enrichment of 20 wt% was used to replace the UAl4 alloy fuel with an enrichment of 90 wt%, and the thickness of the fuel meat was adjusted accordingly.

Owing to the high burnup of the HFR, the fuel assembly should withstand radiation damage and accommodate the fission products well. The investigations and wide utilization of dispersion fuels, such as U-Al or U3Si2 [40], originate from research reactors, including HFR [2]. The dispersion fuel exhibited good compatibility with the aluminum matrix, high thermal conductivity, satisfactory capability to retain fission gases, and better fabricability.

Fuel cladding made of aluminum or zircaloy is adopted, which has high strength, a small neutron absorption cross-section, and better corrosion and radiation resistance performance. The U3Si2 fuel has been used to substitute the U-Al fuel under the RERTR project. To compensate for the decrease in 235U enrichment, the uranium density in the fuel assembly must be increased. For innovative LEU fuels [5], such as U-Mo alloys, the uranium density can reach 10 g/cm3 or higher.

HFRs often have an extremely high power densities in the reactor core, up to 1000 MW/m3 or higher. Plate or casing assemblies were widely used in almost all later HFRs [41] because of their better cooling performance (larger surface area-to-volume ratio), better mechanical and vibration stability (particularly the curved structure), and lower manufacturing difficulty (compared with cruciform fuels). The evolution of the plate fuel assembly in an HFR is shown in Fig. 8. Fuel plates are typically manufactured using a rolling process, whereas fuel bundles are typically processed using a coextrusion approach.

Coolant and moderator

Most HFRs use the forced circulation cooling mode, and coolant flows through the reactor core from top to bottom [42, 43]. Commonly used coolants include water and liquid metals, and typical moderators are light water, heavy water, and beryllium.

A large proportion of HFRs use light water as the coolant and moderator. Because of the strong shielding effect of light water on neutrons, the average free path of neutrons in light water is relatively short. When neutrons reach the irradiation channel from a fission event, a significant proportion of attenuation occurs in the neutron flux. In addition, the water layer in the thermal neutron channel has a strong shielding effect on fast neutrons. The average free path of neutrons in heavy water is longer than that in light water, which potentially contributes to a higher neutron flux.

Liquid sodium or lead bismuth is often adopted as the coolant in fast-neutron HFRs, such as VTR and MBIR. The satisfactory thermal performance of the liquid metal coolant guarantees efficient heat transfer from the fuel assemblies. The sodium-cooled HFR typically requires an intermediate loop, which also increases the system complexity. The boiling point of lead bismuth alloy is 1670 ℃ at atmospheric pressurized condition, which potentially improves the reactor’s inherent safety. The melting point of this type of alloy is relatively low (125 ℃), enabling the reactor to operate at low temperatures, reducing the requirements on structure materials. In addition, no significant volume change occurs in the process of transformation from solid to liquid, which is favorable for the frequent startup and shutdown of the reactor. For these reasons, the newly proposed fast-neutron HFR tends to adopt the lead bismuth alloy as a coolant [44]. However, some challenges in lead-bismuth-cooled reactors still exist, such as the corrosion of the fuel and structural materials.

Reflector

The presence of reflectors reduces the critical fuel mass and increases the neutron flux-to-power ratio. Common reflector materials include water, heavy water, beryllium, beryllium oxide, and graphite. Based on a single-group model for spherical reactors using different moderators and reflectors, Bath et al. [2] found two configurations that provide the largest ratio of maximum neutron flux and reactor power, i.e., reactors using water moderator and beryllium reflector (6.78×1010 n/(cm2·s·kW)), and reactors using heavy water as moderator and reflector (7.34×1010 n/(cm2·s·kW)).

Therefore, an HFR typically utilizes beryllium or heavy water as a reflector surrounding the reactor core to reduce neutron leakage from the reactor. The neutron absorption cross-section of beryllium or heavy water is smaller than that of light water, which results in a higher thermal neutron flux and enables the feasibility of irradiation experiments performed in the HFR. The arrangement of the irradiation channels in a heavy-water reflector is relatively convenient; however, adjusting the structure and position of the reflector is difficult. Moreover, the system structure related to heavy water is complex and requires higher maintenance costs, as well as sealing and cooling. Beryllium is also defective during long-term operations and shutdowns. It is prone to radiation swelling and embrittlement after being employed for decades [45] and beryllium poisoning during shutdowns [46]. To ensure safe operation of the reactor, radiation supervision and regular replacement of beryllium components are necessary.

Reactivity control mechanism

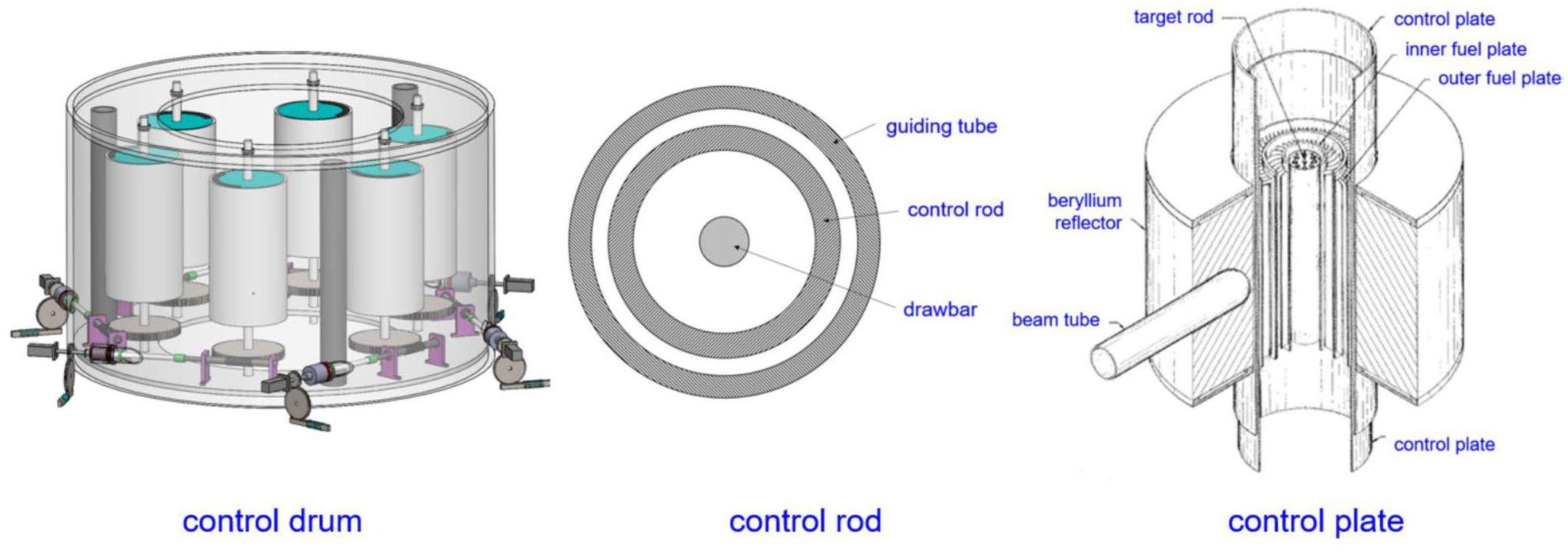

Reactivity control is the basis for reactor startups, shutdowns, and power adjustments. The reactivity control elements of HFRs typically include control rods, control plates, and rotation control drums [47], as shown in Fig. 9. The main distinctions between the various control elements are action modes, such as linear or rational movements. Most HFRs, such as HFIR and HFETR, adopt an in-core control rod or control plate, whereas only a few HFRs, such as ATR, use rotational control drums. Some have adopted a control mechanism that combines a control drum and control rod, with the control drum serving as the main approach.

Compared with the control rod in the core, the control drum installed in the reflector can reduce neutron absorption and flatten the axial power distribution. However, the control value was typically smaller than that of the control rod. The main technical parameters of the control drum include the rotation angle range (typically between 0° and 180°), rotation velocity, single-rotation limit, rotation position accuracy, quick reset time, temperature, pressure, and type of working medium.

A follower fuel assembly is typically adopted as the control element inserted into the reactor core. When the control element is withdrawn from the reactor core, the follower fuel element is inserted into the reactor core, which helps compensate for the reduced reactivity.

For a more convenient operation of the irradiation devices in the upper space of the reactor, the control drive motors of various control elements are typically located below the reactor core. CARR [14] has four compensation control rods in the reactor core and two safety rods in the heavy-water reflector adjacent to the reactor core. The driving mechanism of the compensation control rod is arranged at the bottom of the reactor core and adopts magnetic driving technology, which adopts hydraulic drive technology and uses diverse design principles that are different from those of the compensation control rod, which is conducive to avoiding common cause failures and improving reactor safety.

Hydrochemistry

The hydrochemical requirements of HFRs are less complex than those of power reactors owing to their lower coolant operating temperatures and shorter fuel lifetimes. An HFR is more concerned with maintaining a low level of radioactivity in the coolant than with scale formation [2]. This radioactivity is primarily sourced from reactive gases and radioisotopes dissolved in water. In addition to isotopes 19O and 41Ar, fluorine and nitrogen isotopes 13N and 16N also contribute to gas activity. Radioisotopes dissolved in water originate primarily from supplemental water and circuit materials. Sodium and calcium salts in the makeup water are irradiated to produce 24Na and 45Ca. Structural materials and fuel cladding enter the coolant owing to corrosion after prolonged irradiation.

In addition, the coolant should be slightly acidic to minimize aluminum cladding and beryllium corrosion.

According to Vladimirova [48], Russia proposed the following hydrochemical standards for the first loop of the research reactor:

· рН value at 25 °С, 5.0–6.5, ±1%;

· mass concentration of chloride ions, not more than 50.0 µg/kg, ±20%;

· mass concentration of aluminum, not more than 50.0 µg/kg, ±5%;

· mass concentration of iron, not more than 50.0 µg/kg, ±5%;

· total specific activity by fission products, not more than 2.5×107 Bq/L.

Irradiation capability

Irradiation facilities

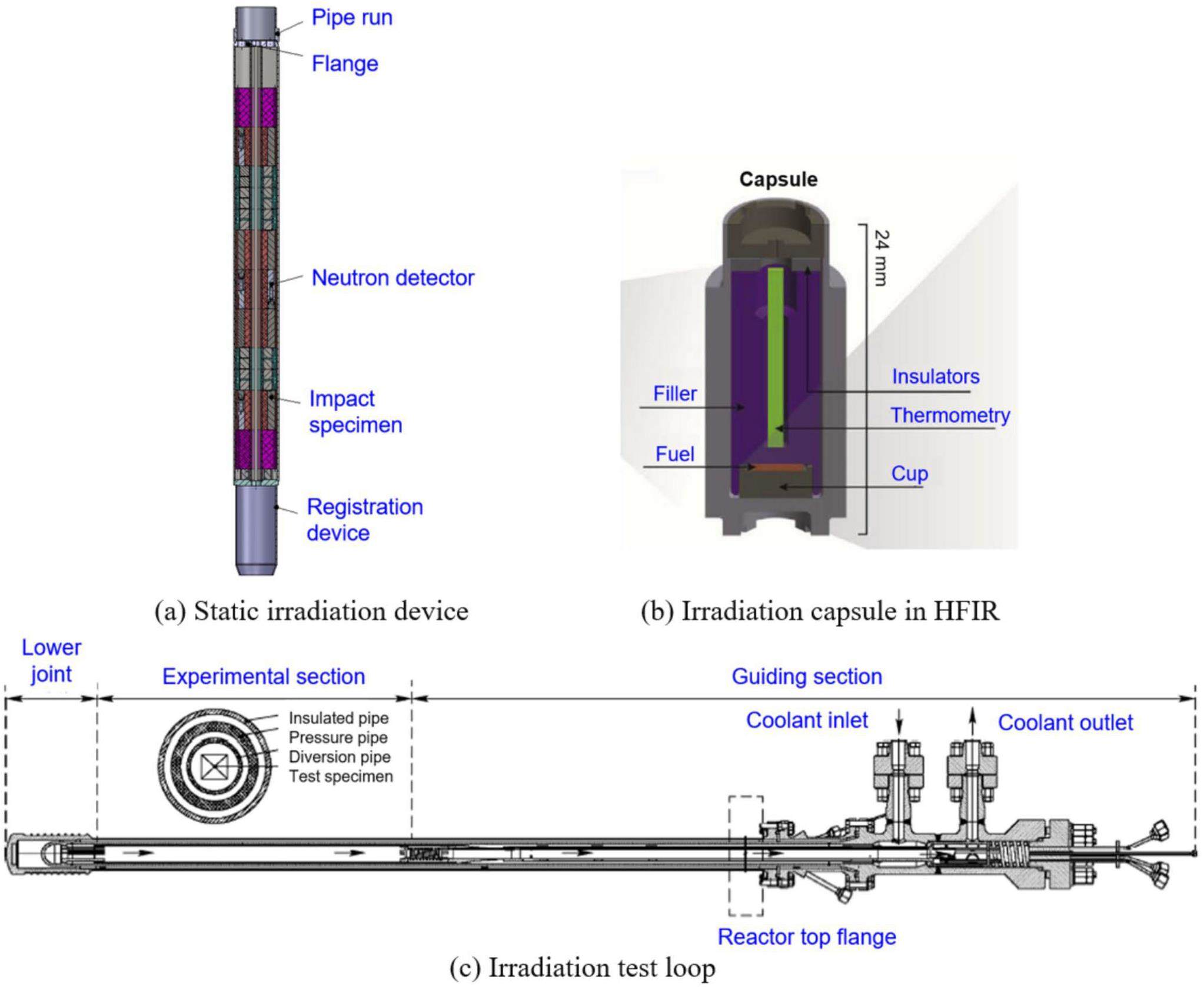

An HFR is primarily used for neutron irradiation. The capability and performance considered in the irradiation tests primarily include the neutron flux, neutron energy spectrum, irradiation space, irradiation time, temperature, pressure, gas environment, and online monitoring. The irradiation facilities [49-51] typically include static irradiation devices, instrumented irradiation devices, irradiation test loops, and rabbit test devices.

A static irradiation device is used to enclose and fix the irradiation test specimens, which are typically in the form of irradiation jars or tanks, frequently in an inert gas or water environment. A small irradiation jar can be arranged in the reactor core or reflector, and it can be designed with flexibility for insertion and uploading operations. Some samples with low heat generation are suitable for a closed irradiation device, whereas others may require coolant flow channels. The larger irradiation tank is located outside the reactor core to utilize the leaked neutrons.

Working conditions, such as the temperature of the static irradiation device, cannot be monitored during irradiation but only rely on reactor operation. Instead, the instrumented irradiation device provides the capability to monitor online irradiation parameters such as irradiation temperature, gas composition, coolant temperature, coolant pressure, and coolant velocity. It is equipped with various monitoring devices, including thermocouples, neutron detectors, flow meters, sampling tubes, pressure tubes, gas tubes, and electric heating elements. The temperature of an irradiated sample is the most commonly monitored and controlled parameter. Ensuring the temperature of the fuel sample does not exceed the safety limit is particularly important. In addition, equipment for monitoring neutron fluence is fundamental for irradiation testing of advanced reactor materials [52].

As shown in Fig. 10, the irradiation test loop was designed to simulate the actual operating conditions of the test specimens, which are typically utilized to irradiate nuclear fuel and materials with large heat generation. A typical design is a central neutron flux trap, which is utilized in the SM [22] and HFIR reactors [27]. Figure 10 (b) shows the small irradiation capsule utilized in HFIR for fuel irradiation tests; it is located in the flux trap irradiation position. The aim of designing this trap is to obtain a higher thermal neutron flux than that of the test loop in the active zone. Hence, these traps are often filled with light water [2]. The coolant of the test loop is isolated from the primary coolant, and the irradiation parameters, including pressure, temperature, and velocity, are controlled separately by the loop. The design and construction of an irradiation test loop are relatively complex. The Russian MIR.M1 reactor [17] has 11 experimental circuits, including water, steam, and gas test loops, which provide irradiation test environments for various reactors.

The rabbit test device can automatically and flexibly accomplish sample transportation, irradiation, and measurement. The rabbit system is composed of multiple rabbit capsules driven by a pneumatic or hydraulic transmission and controlled by an automatic or manual approach. This test facility enables irradiation samples to be inserted into or removed from the target area during reactor operation, making it suitable for producing radionuclides with short half-lives, neutron activation analysis (NAA), and nuclear data measurement.

Post irradiation examination

The facilities for post irradiation examination of irradiated nuclear fuel and materials are primarily used for transportation and temporary storage, cutting and dismantling, non-destructive testing of irradiation devices and samples, and post-irradiation inspection of spent fuel and materials. These include appearance and size analysis, weight measurement, burnup analysis, composition and microstructure analysis of irradiated samples, accident condition simulation, study of mechanical and thermal performance research, and special research performed according to user requirements. The post-irradiation facility [53, 54] primarily includes a hot cell and radioisotope processing device.

The cluster of hot cells is composed of heavyweight concrete hot cells, lead-shielded hot cells, and shielded glove boxes. The hot cell is often adjacent to the HFR, and transportation channels and waterways are connected to the reactor. An interface device is used to transport the irradiated fuel or material from an external transportation container to a temporary storage room in a hot cell. Special lifting facilities, master-slave robots, and power robots are used to conduct post-irradiation inspections of different types and structures of fuel elements and structural materials.

Postprocessing for radioisotope production involves irradiated target dissolution, radiochemical separation and purification, and radioactive waste transportation. Radioisotope processing facilities include hot cell lines and several glove boxes. Highly radioactive isotopes need to be processed in the hot cell, and relatively less radioactive isotopes can be utilized in glove boxes.

Operating characteristics

In an HFR, the operating power and period change frequently according to the requirements of specific experimental missions, leading to differential operating characteristics and safety standards [52].

The physical startup or first criticality is an important milestone in the construction of HFR [55]. Physical startup experiments can verify the theoretical design of the reactor and obtain basic physical parameters, such as the control rod worth and reactivity temperature coefficient, for subsequent operation. For instance, ATR has a critical testing device, ATRC, which is a 1:1 replicate of the reactor core. With the development of reactor physics analysis methods, the startup of an HFR can be accurately predicted using numerical simulations, which may substitute for the construction of critical experimental devices. The physical startup of CARR was entirely based on the theoretical results of physics calculation codes [56].

Beryllium blocks can produce high-energy neutrons through the (γ,n) reaction [57]. The strong background generated by the photoinduced neutron effect of beryllium is effective in overcoming blind spots when the HFR operates at high power for a period without the need for an additional neutron source to restart. However, the presence of photoexcited neutrons also increases the difficulty of extrapolating fuel elements during the initial fuel-loading procedure for criticality. In addition, the effects of beryllium poisoning [46] also must be considered. 9Be produces 6Li and 3He with strong thermal neutron absorption cross sections in fission reactions with fast neutrons. 3T from 6Li decays to 3He during reactor shutdowns, enabling a large accumulation of 3He. The longer the reactor has been in operation, the longer the shutdown, the larger the negative reactivity, and the shorter the allowable shutdown time [58]. The beryllium status must be monitored prior to startup.

In an HFR, the surface heat flux of the fuel assembly is large. As mentioned previously, the operating pressure and temperature of the coolant are relatively low, but the coolant flow speed is considerably high to ensure sufficient cooling capability. The irradiation test components or targets affect the reactivity and power distribution of the HFR core [59] and cause significant heat generation. Therefore, additional requirements exist for cooling the experimental equipment [60]. Because the coolant channel is narrow, blockage accidents in the coolant channel must be prevented during operation [61, 62].

Under high- or full-power operating conditions, the coolant of an HFR flows from top to bottom to cool the reactor core, driven by the primary pump. During low-power or shutdown operation, the reactor is cooled by natural circulation, and the coolant flows from bottom to top. This means that the coolant flow direction reverses, which results in zero coolant velocity during reversal, causing the convective heat transfer coefficient to decrease, resulting in deterioration of the heat transfer. The flow reversal effect [43] should be considered during the reactor shutdown.

Special attention should be given to various operations and experiments that may cause reactivity changes during operation. The reactivity disturbance value and rate should be accurately estimated. Irradiation test components should be considered part of the reactor, and their reactivities should be evaluated individually. Notably, when a large number of irradiated samples are placed in the irradiation channel, the neutron flux is significantly reduced owing to the large absorption, resulting in the failure of the irradiation channel. The operation of large reactivity components should be performed during shutdown cooling periods, whereas the manipulation of small reactivity components can be performed without reactor shutdown.

The lifespan of a vessel HFR depends primarily on the life of its pressure vessel, which is determined by the irradiation effect of fast neutrons (energy typically higher than 0.1 MeV). Early designed HFRs opted for the replacement of pressure vessels, such as the HFIR. The SM-3 reactor was constructed with a new pressure vessel inside the old one [22]. Therefore, monitoring the fast neutron fluence in pressure vessels is necessary during the lifespan of HFRs. HFETR uses SUS321 stainless-steel rods instead of aluminum rods in the outermost reflector to extend the life of the pressure vessel.

Applications of high flux reactors

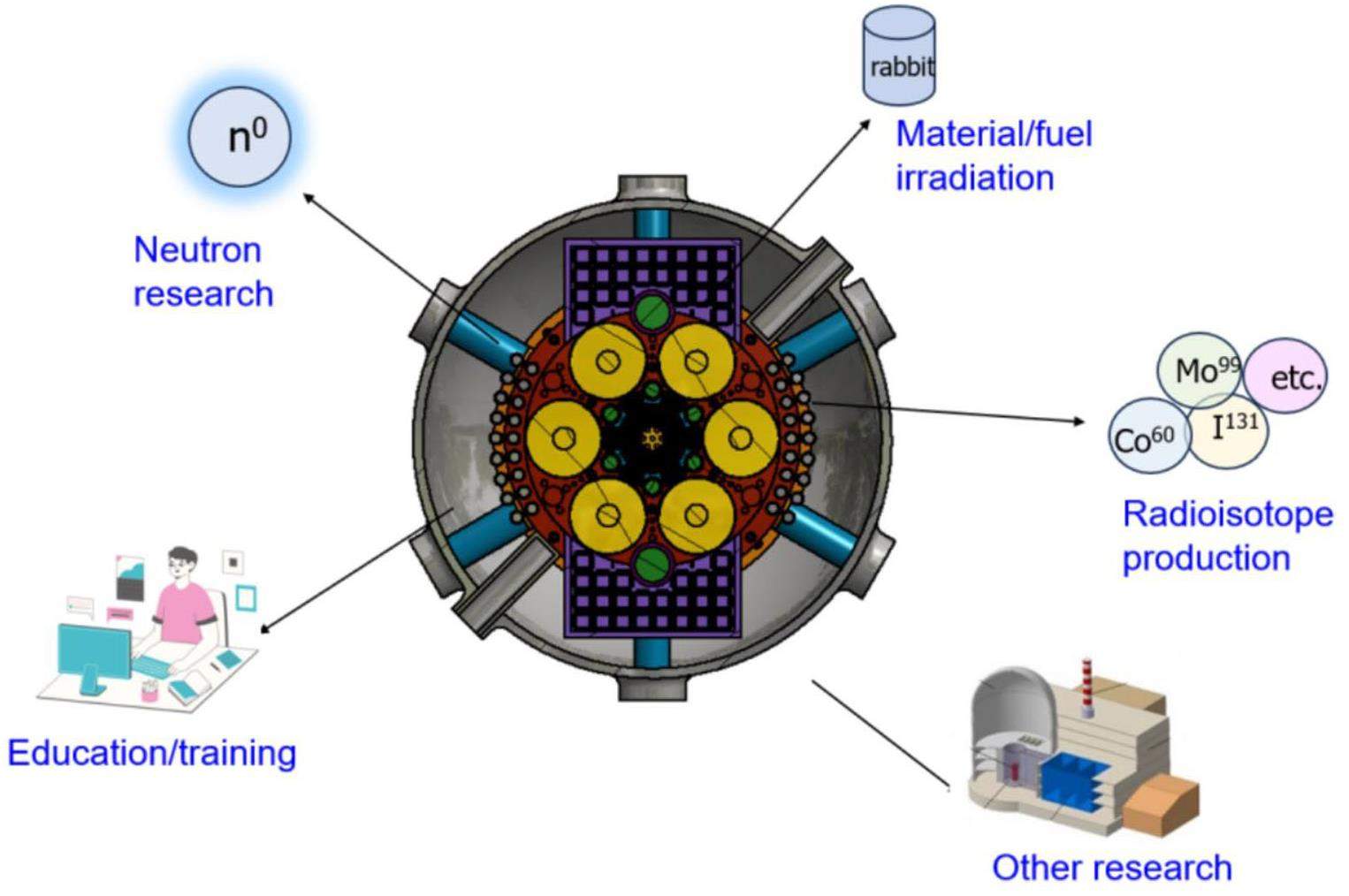

According to statistical data on the IAEA website [8], the applications of operational research reactors are summarized in Table 3. Because of its stronger irradiation capability and more complete experimental facility, the HFR typically has significant advantages over other research reactors in various application areas. As shown in Fig. 11, based on the demand and importance of irradiation missions, the HFR is primarily applied in nuclear fuel and material tests, radioisotope production for medical and industrial use, and neutron science research.

| Utilization | Reactor number |

|---|---|

| Radioisotope production | 80 |

| Material / fuel irradiation | 64 |

| Neutron scattering / imaging / NAA | 35 |

| Neutron therapy | 15 |

| Silicon doping / Gemstone coloration | 13 |

| Teaching / Training | 156 |

| Geochronology | 23 |

| Nuclear data provision | 15 |

| Other application | 113 |

Nuclear fuel and material tests

Fuel irradiation tests

To further satisfy the requirements for improving the efficiency, reliability, and safety of nuclear power plants, innovative fuel assemblies are continuously being developed to increase fuel burnup, extend refueling cycles, and enhance safety margins and reliability.

The technical parameters considered in nuclear fuel irradiation primarily involve the neutron flux [63, 64], neutron energy spectrum, channel dimension, gas environment, online monitoring, and fuel failure rate. The fuel irradiation test [65] is primarily conducted in the irradiation loop, which is completely sealed and isolated from the reactor core to prevent radiation contamination, even if the tested fuel assembly is damaged. A simulation of nuclear fuel behavior under transient and accident conditions can also be conducted for specific irradiation loops. During irradiation, the fission power of the fuel assemblies and the γ radiation increase the reactor core temperature. A fuel irradiation sample containing more fissionable materials requires higher cooling rates and larger experimental volumes, which should also be given more attention.

The existing HFRs used for fuel tests typically utilize thermal neutrons. Rod-bundle test fuel assemblies are adopted for the irradiation test of pressurized water-cooled reactor fuels. A 4×4 test assembly contains four guide tubes and 12 test fuel rods with different fuel densities, enrichments, and other parameters. The actual operating conditions of PWR fuel assemblies are simulated during the irradiation tests. From 2012 to 2014, HTR-PM fuel pebbles were irradiated in HFRs for qualification tests, with a total irradiation time of 355 EFPD [66]. Five fuel pebbles were fixed in the irradiation capsule, which was placed in the sweep loop irradiation test facility, and the central pebble temperature was maintained at 1050±50℃. The post irradiation examination showed satisfactory performance of the HTR-PM fuel pebbles, with no particle failure. The micro fuel test has also become an important application, such as that performed in HFIR [67]. The micro fuel sample can be encapsulated in a sealed target and placed in a basket through which the primary coolant flows without requiring an independent test loop.

With the development of advanced nuclear reactors, the demand for fast reactor fuel tests is increasing, e.g., U-Zr alloy, U-Pu-Zr alloy, UPuN, and MOX fuels. Therefore, an irradiation testing circuit suitable for fast reactor fuel irradiation should be constructed to satisfy the requirements of special working fluids, neutron fluence, and radiation damage dose.

Material irradiation tests

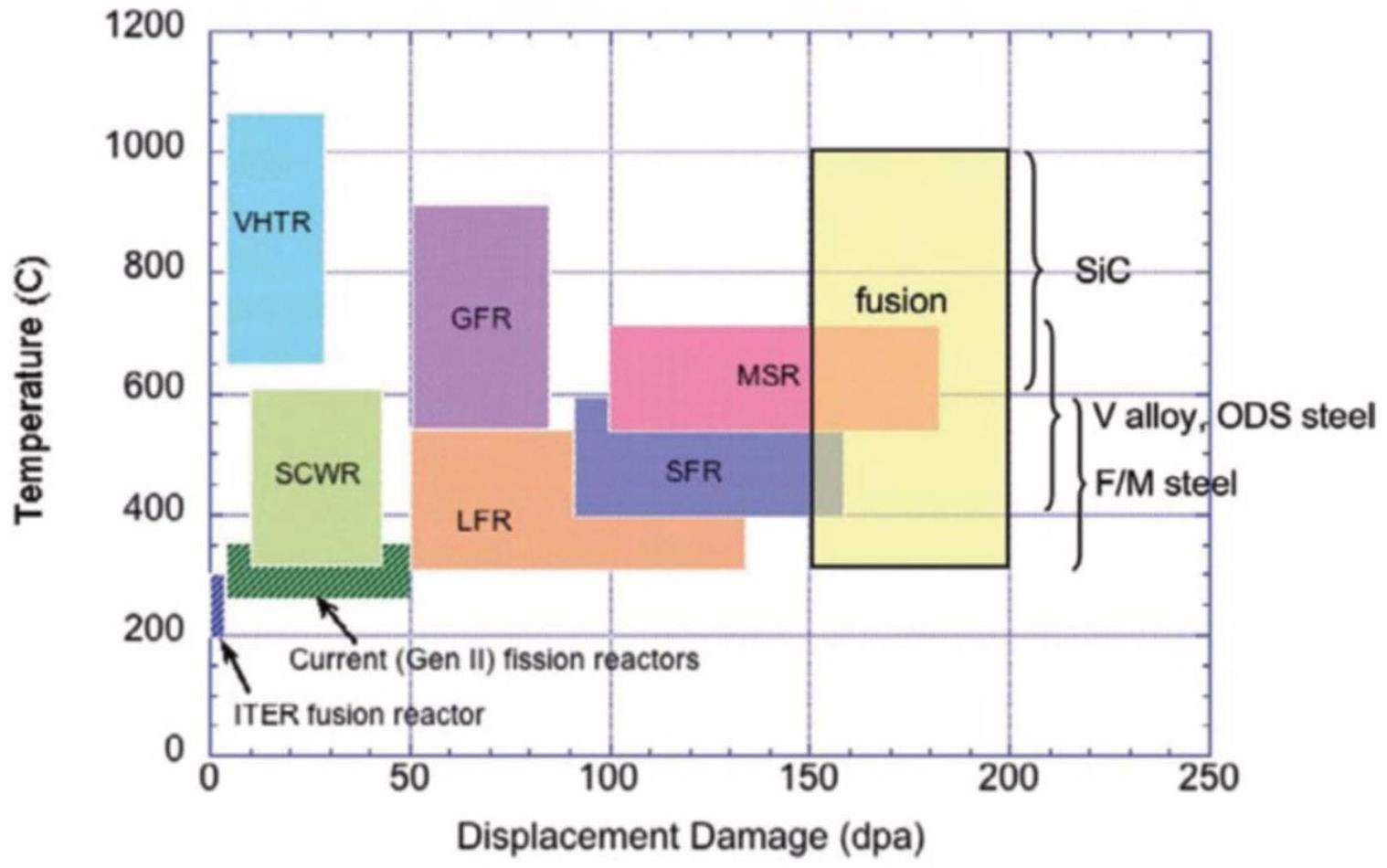

To achieve better technical specifications and safety, advanced nuclear energy systems typically use innovative materials with better radiation or corrosion resistance and the ability to withstand higher operating temperatures [68-70]. The irradiation temperatures and radiation damage required for different advanced nuclear energy systems [71] are shown in Fig. 12.

The irradiation temperatures required for advanced nuclear reactors, particularly the VHTR (650–1050 ℃), GFR (550–900 ℃), MSR (550–700 ℃), and fusion reactor (300–1000 ℃), are generally higher than those of the conventional fission reactors. The required radiation damage doses are also much higher, such as those in the fusion reactor (150–200 dpa), MSR (100–180 dpa), SFR (90–160 dpa), and LFR (50–130 dpa). To fulfill the irradiation requirements of the materials used in these innovative reactors, both the temperature and fast neutron fluence of the HFR should be improved.

For example, ATR is primarily used in fuel and material irradiation tests, and multiple material irradiation tests have been conducted [72]. Instrumented lead experiments are used to perform irradiation tests on structural materials, cladding, and fuel pins. Six pressurized water loops installed in the flux traps can be used for the irradiation of structural materials, cladding, tubing, and fuel assemblies. Materials and fuels for naval reactors, high-temperature gas-cooled reactors, and Magnox reactors have been irradiated using ATR [72]. The fuel assemblies used in the Soviet Union’s nuclear thermal propulsion were tested in the IVG.1M and IGR reactors [73].

Radioisotope production

Radioisotopes [74] have wide applications in industry, medicine, agriculture, and other related fields. Most industrial and medical radioisotopes, particularly neutron-rich radioisotopes with high specific activities, are produced by HFRs worldwide. Medical radioisotopes [75] are an important foundation of nuclear medicine, and their applications primarily include diagnostics (medical imaging) and therapy (radiation is used to kill cancer cells or lesions). Some transplutonium isotopes such as 238Pu, 241Am, 249Bk, 252Cf, etc., play an irreplaceable role in industry, non-destructive detection, aerospace heat sources, reactor startups, and scientific research. Several isotope-based radioactive sources are required in industrial and agricultural areas, including 60Co, 137Cs, and 191Ir.

The radioisotopes are primarily produced by neutron induced reactions (such as (n,γ), (n,α), (n,p), and (n, f)) occurring in irradiation targets. Most reactions involve radiative capture and fission reaction [74]. In the radiative capture method, the product and target nuclides belong to the same element; therefore, the chemical separation of the product nuclide from the target is frequently disabled, which reduces the specific activity of the product to some extent. Multiple types of radioisotopes can be obtained using the fission method, which facilitates the acquisition of carrier-free radioisotopes with high specific activity.

The preparation of radioisotopes involves several continuous processes [74], such as appropriate selection of target materials, target fabrication and encapsulation, irradiation in the reactor, transportation to the hot cell, target disassembly, radioisotope separation and purification, processing and source encapsulation, quality control, product packaging, and shipping. During the procedure of loading irradiation targets in the reactor core, the irradiation positions and periods were flexibly chosen according to the requirements for producing different types of radioisotopes on neutron fluxes and spectra. The preparation of radioisotopes requires radiochemical postprocessing of the irradiation targets, and radiochemical processing must be conducted in hot cells with the corresponding radiation protection requirements. Radioisotope products should also satisfy quality control requirements, and the specific activity, chemical purity, and radiochemical purity are the three main parameters for assessing the quality of radioisotope products. For medical radioisotopes, the production process requires the establishment of a QA/QC system and good manufacturing practices (GMP) requirements [76].

Rare isotopes production

Transplutonium elements (such as Pu, Am, Cm, Bk, Cf, Es, and Fm) include plutonium and its subsequent homologous elements in the periodic table. These nuclides are all prepared through artificial nuclear reactions owing to their limited production amount and rather difficult production process; they are also referred to as rare isotopes.

The radioisotopes produced in an HFR are closely related to the neutron flux level. The production of transplutonium nuclides [77-80], such as 249Bk, 252Cf, and 253Es, requires ultra-high thermal or resonant neutron flux. Industrial radioisotopes with long half-lives typically require long irradiation periods.

The production of transplutonium nuclides such as 252Cf is complex and technically challenging [81]. The conversion chain of 252Cf from 242Pu, 241Am, 244Cm, or other target nuclides involves a series of more than 10 neutron capture reactions. Intermediate nuclides such as 242Am, 245Cm, and 247Cm have large fission cross-sections, and the thermal neutron absorption cross-sections of 246Cm and 248Cm are relatively small, which results in a very low yield of 252Cf. Therefore, the production of 252Cf requires higher thermal neutron flux (the average thermal neutron flux is typically larger than 1.5×1015 n/(cm2·s)), and the fission losses during irradiation should be controlled as low as possible. Currently, only USA and Russia can produce transplutonium nuclides on an industrial scale. The maximum thermal neutron flux of HFIR and SM-3 are both larger than 5.0×1015 n/(cm2·s), and the irradiation targets are located in the central neutron flux trap in the reactor core. The production of 252Cf in the USA began in 1952 by irradiating 239Pu in MTR, and large-scale production was initiated in 1966 after the establishment of HFIR and REDC in ORNL. A total of 78 production activities for transplutonium nuclides were performed till 2019, and the accumulated production of 252Cf was 10.2 g while preparing 249Bk (1.2 g), 253Es (39 mg), 257Fm (15 pg; 1 pg=10-12 g) and other nuclides [79]. SM-3 was used for 252Cf production, and actinide oxide aluminum metal ceramic targets were adopted.

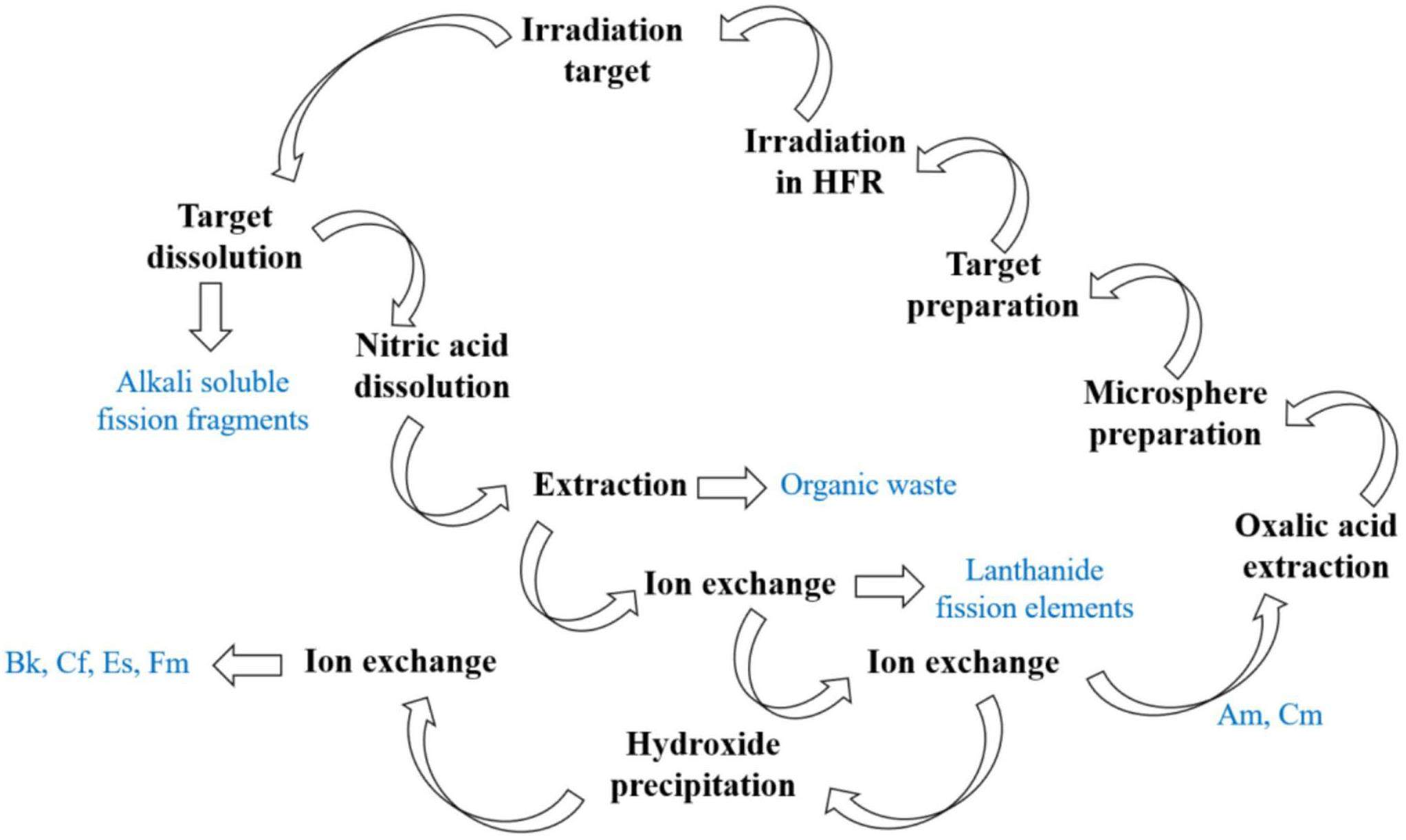

The preparation of transplutonium targets is one of the most important issues in transplutonium production. The flowchart is shown in Fig. 13. Irradiation target materials (plutonium, americium, and curium) are typically aluminum-based transplutonium oxides. This type of target aids in improving thermal conductivity and preventing the sintering of transplutonium oxide ceramics. The main approach for 252Cf production in large scale depends on irradiating 242Pu or mixed americium/curium targets. Owing to the large cross-sections of many target nuclei (such as 239Pu, 242Pu, 242Am, 244Cm, etc.), the target material density should be reduced to reduce the self-shielding effect of the target nucleus and heat released in the target during irradiation. The quality and safety of the fabrication and encapsulation process of the transplutonium target should be well controlled, which involves high-temperature and radiation-resistant target preparation technology and high-sealing welding technology for irradiation targets.

By analyzing the cross-sectional energy spectrum distribution of intermediate nuclides in the conversion chain of transplutonium nuclides, the neutron capture cross-sections of major nuclides, such as americium/curium are relatively large in the resonance energy region, which can increase the probability and yield of neutron absorption by transplutonium nuclides. This means that transplutonium production amounts can be further optimized by adjusting the neutron spectrum of the irradiation target to increase the capture-to-fission ratio [81-83].

Transplutonium targets typically operate continuously in the reactor for nearly six to eight months. The irradiated targets are uploaded from the reactor core and transported to hot cells for radiochemical reprocessing. The postprocessing primarily includes target dissolution, co-decontamination of transplutonium and lanthanide elements, separation of transplutonium and lanthanide elements, and transplutonium separation.

Medical isotopes production

Nuclear medicine [84] is one of the most important applications of radiation and nuclear technology. In contrast to external radiation therapy, radioactive materials are transported into organs to be examined or treated based on the patient’s metabolism. Radioisotopes for medical applications (such as 99Mo and 131I) form the basis of nuclear medicine and healthcare. Owing to the short half-life of radioisotopes, nuclides are difficult to store over a long term.

High or ultra-high neutron flux increases the efficiency of producing medical radioisotopes with high specific activity in a shorter time. The production of medical radioisotopes (such as 60Co, 63Ni, 89Sr, 90Y, and 177Lu) in an industrial scale typically requires a neutron flux larger than 1014 n/(cm2·s), and a higher neutron flux contributes to achieving higher specific activities. Short-lived medical radioisotopes frequently require online processing of irradiation targets. A broader neutron energy spectrum provides a more flexible selection for irradiating a radioisotope target with an appropriate neutron flux. The production of radioisotopes, which are fission products, typically involves two approaches: the fission-based method and radiative capture method (or activation method). OPAL was one of the earliest HFRs to use an LEU target for 99Mo irradiation. The fission method facilitates the acquisition of carrier-free medical radioisotopes with high specific activity. In addition, the radiative capture method is more sensitive to the neutron flux level; thus, the HFR has potential advantages for increasing the specific activity through the activation method.

The HFRs used for medical isotope production and supply include HFR (Netherlands), BR2 (Belgium), SAFARI-1 (South Africa), and OPAL (Australia). The main radioisotope products are 99Mo/99mTc, 177Lu, 89Sr, and 131I. In the coming years, several major medical radioisotope production reactors worldwide will encounter issues such as aging, shutdown, and decommissioning. After 2030, only OPAL and FRM-II will be able to supply medical isotopes on a large scale. The production capacity gap for medical radioisotopes remains significant with global shortages of 99Mo and 177Lu exceeding 10000 Ci/week and 50000 Ci/year, respectively. The global supply demand contradiction will further intensify, and important medical radioisotopes will face the risk of shortages. To satisfy the demands of radioisotope production, the Dutch government approved the construction of a novel HFR, PALLAS [85], in 2012 to replace the operating HFR in Peten. The PALLAS reactor will have a thermal power of 55 MW with a design lifespan of 40 years and will be primarily used for producing medical radioisotopes. Construction has already begun.

The irradiation periods of several radioisotopes with short half-lives are smaller than the refueling period, such as 99Mo, whose production reaches an equilibrium value after an irradiation period of 5–7 days. Excess irradiation will not increase the production amount and will increase the concentration of radioisotopes with long half-lives and high-level radioactivity. Therefore, online processing of the irradiation target, which involves pressure boundary sealing issues caused by the top opening of the pressure vessel, is required. The quality control limitations of radioisotope targets include the maximum reactivity disturbance limit, cooling flow limit, and γ heat release rate of the material.

Neutron science and experiments

Neutron scattering

Neutron scattering technology [86] is based on measuring and analyzing the changes in momentum energy after the interaction between thermal neutrons (or cold neutrons) and materials and can be used to study the microstructure and dynamics of materials. Cold neutrons are neutrons with energy levels of meV or lower that are suitable for neutron scattering, neutron imaging, and other applications. The neutron scattering involves neutron diffraction, large-scale structural scattering, inelastic scattering, and other effective means. [87, 88]. The typical neutron scattering spectrometers include small-angle neutron scattering, time-of-flight polarized neutron reflection, and cold-neutron triple-axis spectrometers.

The quality of the neutron beam emitted from the reactor core is related to the position and angle of the neutron beam channel, which should be determined during HFR design. A neutron scattering spectrometer would be selected based on the characteristics of the reactor core design. HFIR has four horizontal neutron beam tubes and 15 neutron scattering spectrometers [11].

Thermal neutron experimental spectrometers are typically arranged around the reactor core and utilize neutrons extracted from a horizontal neutron channel. Thermal neutron scattering spectrometers include neutron stress analysis, thermal neutron triaxial, and neutron diffraction spectrometers [89], etc. The moderating effect of the thermal neutrons increases the proportion of cold neutrons in the neutron energy spectrum. Cold neutrons with longer wavelengths are suitable for structural testing in the nanometer to submicron range, as well as for inelastic scattering measurements in the energy range below 10 meV. A mirror-structured guide tube can be used to guide the neutrons over long distances to suitable spectrometers at suitable positions. However, thermal neutrons cannot be released through a mirror-structured guide tube, which results in significant losses along the path. Ordinary cold neutron scattering spectrometers typically include small-angle neutron scattering spectrometers, time-of-flight polarized neutron spectrometers, and cold neutron triaxial spectrometers.

Neutron imaging

For neutron imaging [90, 91], the attenuation of the intensity of a neutron beam passing through an object is used to perform perspective imaging of the measured object. Therefore, the microstructure, spatial distribution, density, multiple defects, and other related information on the sample materials can be presented at a certain resolution.

Neutron imaging devices can be divided into fast neutron [92], thermal neutron [93], and cold neutron imaging devices [94]. Fast neutron imaging is suitable for the testing of large samples of various materials. The thermal neutron imaging device is located near the reactor core and has a high neutron flux, which is suitable for real-time imaging and large-scale sample testing. By selecting different filters and intercepting neutrons in different energy spectra, thermal neutron, epithermal neutron, and fast neutron imaging can be achieved. The cold neutron imaging facility in the cold neutron experiment hall has a low background and is suitable for application in high-resolution, symmetrical, and polarized neutron imaging. The non-destructive detection approach has significant technical advantages compared with X-rays and other traditional radiography technologies, which are suitable for imaging turbine blades, high-speed rail wheels, and nuclear fuel assemblies. In recent years, the combination of neutron imaging and digital technology as well as artificial intelligence has helped improve the imaging effect and achieve a wider range of applications [87].

Neutron activation analysis

NAA [95, 96] is a non-destructive nuclear analysis method that uses a neutron beam with a certain energy and current intensity to bombard the sample, resulting in the activation of the measured element into a radioactive nuclide and measurement of the characteristic ray energy and intensity released by the generated nucleus. The NAA technology has wide applications in physics, chemistry, materials, and energy. NAA can analyze multiple elements with high sensitivity, high accuracy, and low pollution, and is suitable for detecting samples in a wide range of sizes over a shorter period.

Compared with accelerator neutron sources and radioisotope neutron sources, the HFR neutron source has a high neutron fluence, large activation cross-section for most elements, satisfactory spatial uniformity of neutron flux, and simple nuclear reaction pathway, which results in a lower detection limit and higher sensitivity and accuracy. The reactor contains an NAA laboratory that is used to analyze samples irradiated in large pneumatic transport irradiation tubes for only a few minutes. They arrive at the laboratory within seconds from the reactor, and activation products with very short half-lives can be analyzed.

Other applications

In addition to the above major application fields, HFRs have extensive applications in other areas such as neutrino detection, silicon transmutation doping, and neutron therapy.

Neutrinos [97] are one among the most fundamental particles in nature. They participate only in weak and gravitational interactions, have minimal interactions with matter, and exhibit extremely strong penetrating abilities. Neutrino research has always been at the forefront of particle physics research, which can help us understand the origin of matter and the universe and reveal the physical principles of the internal structure and evolution of celestial bodies, such as the sun and supernovae. The HFR has a compact reactor core with intensive neutrons, which is suitable for detecting ultrashort baseline neutrino oscillations and accurately measuring reactor-based antineutrino spectra while providing support for the measurement of neutrino mass sequence [98-100]. In addition, performing basic physics research on neutrinos helps in understanding the nuclear reaction process inside fission reactors. PROSPECT [99] is a neutrino experiment facility installed in HFIR that is used to accurately measure the antineutrino spectrum of highly enriched uranium-fueled reactors and detect sterile neutrinos at an energy level of eV by searching for neutrino oscillations on a few-meter-long baseline.

Silicon transmutation doping [101-103] is widely used to dope silicon with phosphorus through the neutron capture reaction of 30Si(n,γ)31Si with subsequent beta decay to 31P. Irradiated silicon is used to produce high-quality semiconductors. Silicon doping primarily utilizes the thermal neutron flux, and the fast neutron and gamma fluxes should be as low as possible. Silicon doping does not have very high requirements for neutron flux levels, and the irradiation facility is simpler; however, a larger irradiation space is required to accommodate a silicon ingot with a diameter of 8–12 in. Therefore, this type of irradiation is suitable for use in pool HFRs, and a silicon ingot can be placed in the reflector surrounding the reactor core. Furthermore, the uniformity of the irradiation and neutron spectrum screens should be considered in the design of silicon-doping schemes.

The reactor based neutron therapy [104] is an important medical treatment approach, and the physical basis is neutron absorption reactions, such as 10B(n,α)7Li, 6Li(n,α)3H, or 157Gd(n,γ)158Gd. The radiation released through these reactions is typically in the MeV range and results in high linear energy transfer (LET). The resulting biological effects would be concentrated in the treated tissues. Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) [105] utilizes a thermal neutron beam to treat shallow tumors. Such facilities are typically located near hospitals. For the HFR, building a comprehensive therapy base for neutron therapy is appropriate. However, radiation protection and a more flexible arrangement should be considered.

Future trends

To satisfy the future research and development requirements for advanced nuclear power systems, newly designed HFRs are pursuing better performance in terms of the following aspects:

1) Higher technical parameters

The design of a novel HFR frequently requires higher technical parameters, including a higher neutron flux, wider energy spectrum range, and better irradiation performance. For a fast neutron spectrum irradiation, the fast neutron flux should typically lie in the range of 1012 to 1015 n/(cm2·s) with a radiation damage of 20–30 dpa per year. To achieve a higher neutron flux, the power density of the reactor core should be increased as much as possible at an appropriate power level; a compact reactor core structure is typically adopted. Additionally, the structural scheme of the reactor body, fuel assembly scheme, control approach, and coolant system should be determined. A broader neutron spectrum range is beneficial for various experiments such as radioisotope production and material irradiation tests [106]. The neutron spectrum of the irradiation device could be optimized by arranging neutron flux traps in the reactor core, selecting irradiation channel structures, and reasonably absorbing materials to improve neutron utilization in the irradiation experiments. Newly built HFRs are typically equipped with multiple irradiation test loops with different irradiation environments for material tests and improved online information collection capability of the irradiation device with accurate detection information on the temperature, pressure, and fission gas concentration to further enhance the irradiation capability of HFRs.

2) Higher nuclear safety characteristics

While pursuing higher technical specifications, the safety goals for building new HFRs are constantly improving, and higher nuclear safety standards must be satisfied to ensure the safety of reactors under normal operating and accident conditions. The reactor should be designed to have satisfactory inherent safety, which typically presents as a large negative reactivity temperature coefficient and strong self-protection capability. Innovative HFRs typically adopt passive safety systems and engineered safety facilities (primary pressure relief, safety injection, boron injection, containment isolation, and residual heat removal systems) to further improve the reactor safety and mitigate the consequences of accidents. The automation level of newly built HFRs should be appropriately improved to minimize the reliance on operators to avoid the impact of human factors on the safety of HFRs.

3) Comprehensive versatility

The comprehensive use of irradiation resources is an important challenge for the application of new HFRs and is also an optimal way to fully utilize the irradiation resources of HFRs. HFRs often prioritize one or more functions when considering other applications. For example, in HFRs dedicated to radioisotope production, targets are always arranged in irradiation channels with higher thermal neutron fluxes. The application of material irradiation tests and neutron beam extraction can also be considered as supplementary schemes. This design approach is beneficial for improving the neutron utilization efficiency. The design of an innovative HFR is typically recommended to satisfy the requirements of comprehensive versatility.

4) Application of innovative technology

The design and construction of an HFR is a complex system engineering project with high technical difficulty and a relatively long development cycle involving a combination of multiple disciplines such as nuclear physics, fluid mechanics, thermodynamics, structural mechanics, and control technology. The use of several new technologies, such as digital technology, can improve the efficiency of design and engineering construction [38]. Digital systems adopt technologies such as digital twins and model-based systems engineering (MBSE) to build a digital design platform, digital engineering construction and debugging platform, digital delivery platform, and intelligent operation platform, providing efficient digital support for the development of HFRs.

The following suggestions are proposed for the future development, design, and application of HFRs.

1) The main challenge in developing HFRs is improving the neutron flux while ensuring safety. A multipurpose HFR with the comprehensive utilization of irradiation resources is one of the development directions. The simultaneous development of various HFR types is recommended. For example, a water-cooled high flux thermal neutron reactor is suitable for producing radioisotopes, particularly rare nuclides, and can achieve ultra-high thermal neutron flux with a mature nuclear engineering foundation. To address the increasing demand for radiation damage to nuclear materials, a high flux fast-spectrum reactor is required, such as a sodium-cooled or lead bismuth-cooled reactor.

2) In the design of an HFR, the relationship between the reactor core design and primary technical parameters (such as neutron flux, radiation damage, and operation period) should be considered. The design procedure depends on the application requirements, which are suitable for establishing a goal-oriented design system. Reactor design should achieve the best parameters for specific applications. A high utilization rate in the HFR operation is also recommended.

3) To satisfy the irradiation requirements of advanced nuclear fuel and materials, the newly built system should fulfill special irradiation parameter requirements (such as high neutron flux, sufficient irradiation volume, and sufficient irradiation damage) with a specialized irradiation device. The irradiation test facility is recommended to operate with special media such as liquid metal, molten salt, and supercritical water. The irradiation experiment should be capable of online monitoring of irradiation test parameters and high reliability. The HFR should also be equipped with advanced postprocessing facilities to produce radioisotope products or perform fuel and material post-examinations. The irradiation test technology should match the reactor structure and specific irradiation test forms, including specimen partition layout, irradiation device design, irradiation parameter monitoring and control, and comprehensive irradiation environment control technologies. The irradiation test design should fully satisfy the irradiation index requirements of the specimens and ensure the safety of the irradiation tests and reactor operation. Owing to the demand for new irradiation tests, the development of irradiation test technologies with a wider range of applications, more measurement parameters, and indicator control capabilities with higher precision should be accelerated.

Research reactors: purpose and future

. International Atomic Energy Agency (2016)Modernization of the IBR-2 pulsed research reactor

. At. Energy 113, 29–38 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10512-012-9591-9SM reactor core modification solving materials-science problems

. At. Energy 93, 713–717 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A: 1021763815423Current status and application of the characteristics of HFETR

. Nuclear Power Engineering. 27. 5(S2), pp. 44-50+97 (1985). CNKI:SUN:HDLG.0.1985-02-004 (in Chinese)Design Features and Innovative Technologies of China Advanced Research Reactor (CARR)