Introduction

The asymmetric fission mode in neutron-deficient 180Hg was discovered in 2010 via β decay of 180Tl [1]. For the fission of 180Hg, its splitting into two 90Zr fragments with magic N = 50 and semimagic Z = 40 is believed to dominate the fission process. However, unlike the initial theoretical prediction, 180Hg has been observed to fission asymmetrically, with heavy and light fragment mass distributions centered around A=100 and 80 nucleons, respectively, [1, 2].

Much theoretical research attention has been drawn to the puzzling fission behavior of 180Hg. For example, macroscopic-microscopic models [1, 3-6] and self-consistent microscopic approaches [7-9] have been used to analyze multidimensional potential energy surfaces (PESs). The presence of an asymmetric saddle point with a rather high ridge between the symmetric and asymmetric fission valleys is the main factor that determines the mass split in fission.

Calculations of fission-fragment yields have also been performed for 180Hg using the Brownian Metropolis shape-motion treatment [3, 5, 10], Langevin equation [11], scission-point model [4, 12-14], and random neck rupture mechanism [15], based on the PESs or scission configurations. The results are in approximate agreement with the experimental data, with a deviation of ∼ four nucleons for the peak positions. Several attempts have also been made to describe the fragment mass distribution of 180Hg in a fully microscopic manner, that is, the time-dependent generator coordinate method (TDGCM) based on covariant density functional theory (CDFT) [9]. The asymmetric peaks were reproduced very well, whereas a more asymmetric fission mode with AH ~ 116 was predicted, which was not observed in the experimental measurements.

In the theoretical study of nuclear fission, PES is an important infrastructure that describes the evolution of nuclear energy with its shape variations on its way from the initial configuration towards scission. In nuclear physics, there are generally two approaches to generating a PES. The first method is based on the historical liquid drop model [16-22] to the well-known macroscopic-microscopic model using parametrization of the nuclear mean-field deformation [23-33]. The other is based on microscopic self-consistent methods [34-43] or the constrained relativistic mean-field method [9, 44-50].

In the macroscopic-microscopic method, a predefined class of nuclear shapes is defined uniquely in terms of selecting appropriate collective coordinates, and a relatively smooth potential energy surface can be obtained. However, owing to limitations in computing resources, the microscopic calculation of the PES can only be performed within a limited number of deformation degrees of freedom. In the microscopic self-consistent method, higher-order collective degrees of freedom are incorporated self-consistently based on the variational principle. In fission studies, the quadrupole and octupole deformation (moments) constraints are natural and most often used to calculate microscopic PES.

However, several studies have shown that because of the absence of hexadecapole deformation (q40 or β4), PES may exhibit discontinuities in large deformation scission regions [51-55]. Ref. [56] investigated the role of the hexadecapole deformation in the PES calculation of 240Pu by applying a disturbance to β4. The results show that one can obtain a smooth 2-dimensional PES in (β2, β3) by parallel calculations with a suitable disturbance of the hexadecapole deformation.

But for asymmetric fission of 180Hg, there have been no reports about the effect of q40 or β4 on the PES of 180Hg. The self-consistent calculation in the quadrupole and octupole deformation spaces indicated that the PES of 180Hg exhibits a different behavior from that of 240Pu or 236U with an increase in the quadrupole moment [7, 9]. Thus, it is interesting to examine the influence of the hexadecapolepole moment on the PES of 180Hg under large deformations and analyze some properties of the scission configuration. In this study, we extend two-dimensional (q20, q30) constraint calculations to large deformation regions by adding q40 constraint to the microscopic PES calculation of 180Hg. The importance of q40 in the self-consistent calculation of the PES for 180Hg under large deformations was investigated. Moreover, the fission dynamics of 180Hg, total kinetic energies, and fragment mass yield distributions based on TDGCM [57] are described and discussed.

Theoretical framework

To study the static fission properties, PES was determined using Skyrme density functional theory (DFT). The dynamic process was further investigated using the TDGCM framework. In this section, we briefly explain these two methods. A detailed description of Skyrme DFT can be found in Ref. [58], and the formulations of the TDGCM can be found in Refs. [57, 59-61].

Density functional theory

In the local density approximation of DFT, the total energy of finite nuclei can be calculated from the spatial integration of the Hamiltonian density

The mean-field potential energy

The pairing correlation is often considered using the Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov (HFB) approximation in DFT [58]. In the case of the Skyrme energy density functional, a commonly adopted pairing force is the density-dependent surface-volume and zero-range potential, as given in Refs. [40, 64]:

The DFT solver HFBTHO(V3.00) [65] was used to generate the PESs, in which axial symmetry was assumed. 26 major shells of the axial harmonic oscillator single-particle basis were used, and the number of basis states was further truncated to 1140. In this work, Skyrme DFT with SkM* parameters [66] is adopted, which is commonly used for fission studies. For the strength of pairing,

Time-dependent generator coordinate method

Nuclear fission is a large-amplitude collective motion that can be approximated as a slow adiabatic process driven by several collective degrees of freedom. In TDGCM, the many-body wave function of the fissioning system takes the generic form

For fission studies, two collective variables, quadrupole moment

To describe nuclear fission, the collective space is divided into an inner region and an external region for the nucleus to stay as a whole and the nucleus to separate into two fragments, respectively. The scission contour, which is a hypersurface, was used to separate these two regions. The flux of the probability current passing the scission contour can be used to evaluate the probability of observing two fission fragments at time t. For the surface element ξ on the scission contour, the integrated flux

Results and discussion

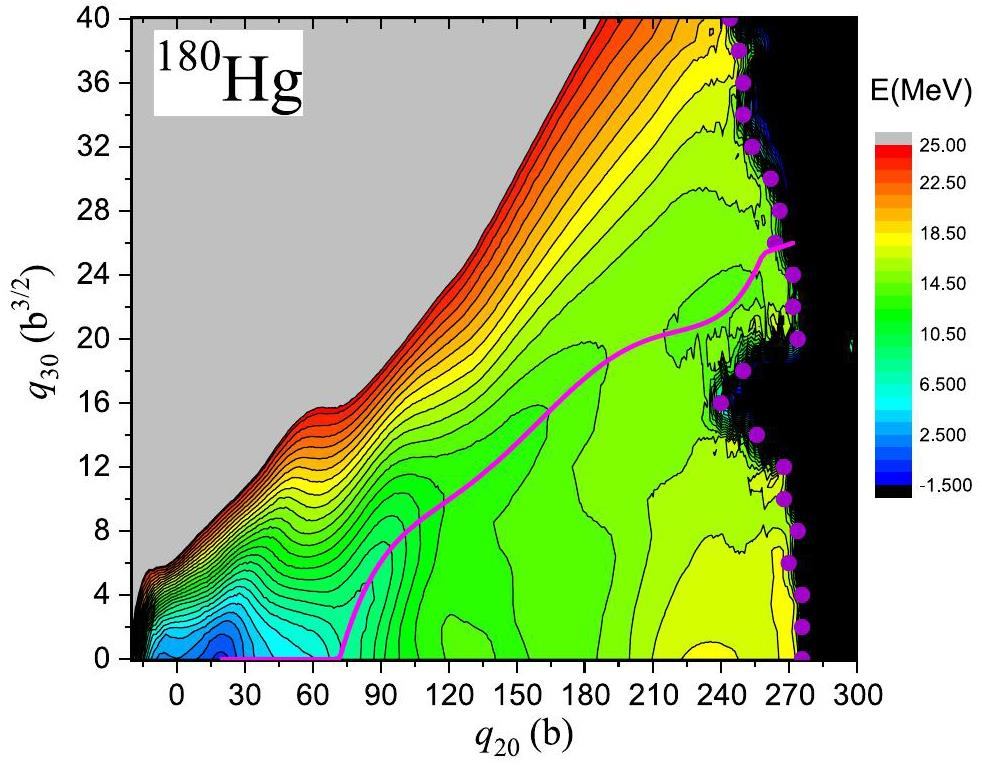

In the adiabatic approximation approach for fission dynamics, precise multidimensional PES is the first and essential step toward the dynamical description of fission. Figure 1 displays the PES contour of 180Hg obtained by the HFB calculation in the collective space of (q20, q30), where q20 ranges from - 20 b to 300 b and q30 ranges from 0 b 3/2 to 40 b3/2 with a step of Δq20 = 2 b and Δq30 = 2 b3/2. Overall, the PES pattern obtained in this work based on the DFT solver HFBTHO with the Skyrme SkM* functional is similar to that obtained using the symmetry unrestricted DFT solver HFODD [7] with the same functional and that obtained using covariant density functional theory with the relativistic PC-PK1 functional [9]. The static fission path starts from a nearly spherical ground state (q20 = 20 b, q30 = 0 b3/2), the reflection-symmetric fission path can be found for small quadruple deformations, and the reflection-asymmetric path branches away from the symmetric path for q20 = 100 b. One can see that unlike the PES of actinide nuclei, there is no valley toward scission for 180Hg, which undergoes a continuous uphill process until the mass asymmetric scission point with high q30 asymmetry.

In the (q20, q30)-constrained PES calculations by DFT, other degrees of deformation are obtained based on the variational principle. In Refs. [56, 55], it has been learned that at a given q20 and q30, there are two minima with different values of q40, and the minimum with a larger q40 disappears when q20 is large enough, which indicates the transition toward scission. Hexadecapole deformation is an important degree of freedom for the description of PES under large deformations. In particular, a disturbance of the hexadecapole deformation is required for a smooth and reasonable PES, as shown in Ref. [56]. Thus, in our work, at large quadrupole moments, that is, larger than

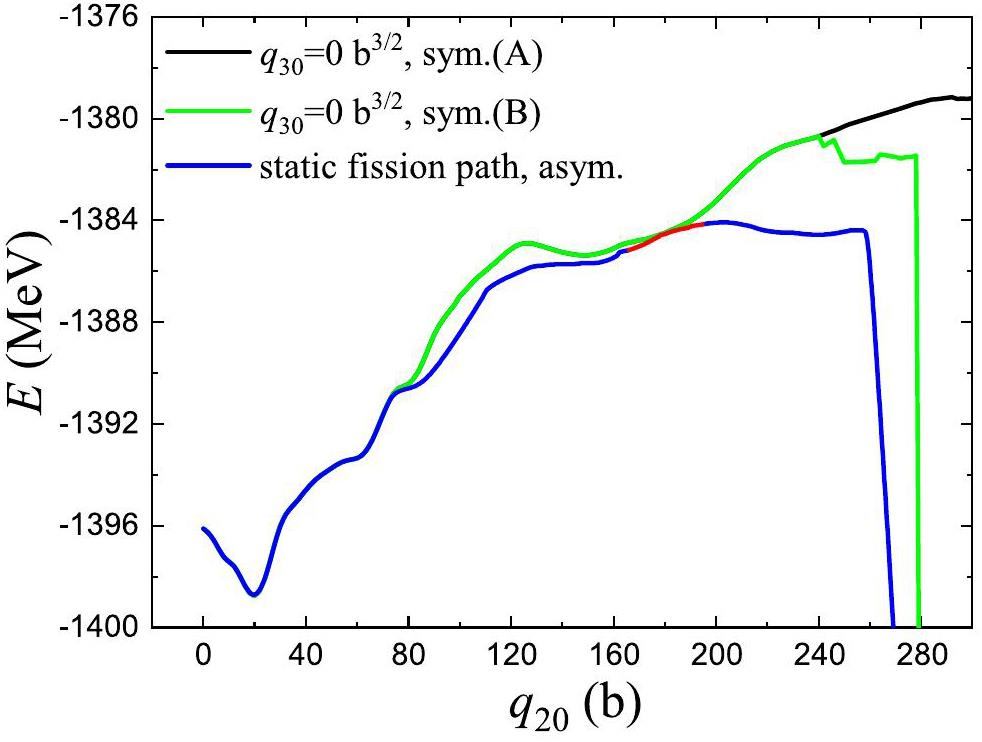

In Fig. 2, the energies of the static fission path as a function of quadruple moment q20 are shown. The symmetric (q30 = 0 b3/2) and asymmetric fission paths in 180Hg are given, respectively. It can be clearly observed that these energies increase with q20 steadily. At approximately q20 ~ 100 b, the asymmetric fission path starts to be favored in terms of energy compared to the symmetric fission path. The transitional valley that bridges the asymmetric and symmetric paths is shown in red in Fig. 2. Notably, this connection occurs at the deformation stage where the symmetric and asymmetric paths are nearly equivalent in energy. This characteristic of 180Hg was verified in Ref. [68] using the HFB-Gogny D1S interaction. From Fig. 2, for case (A), one can see that the energy of 180Hg increases continuously with q20, and that it is difficult to rupture even at very large elongations, for example,

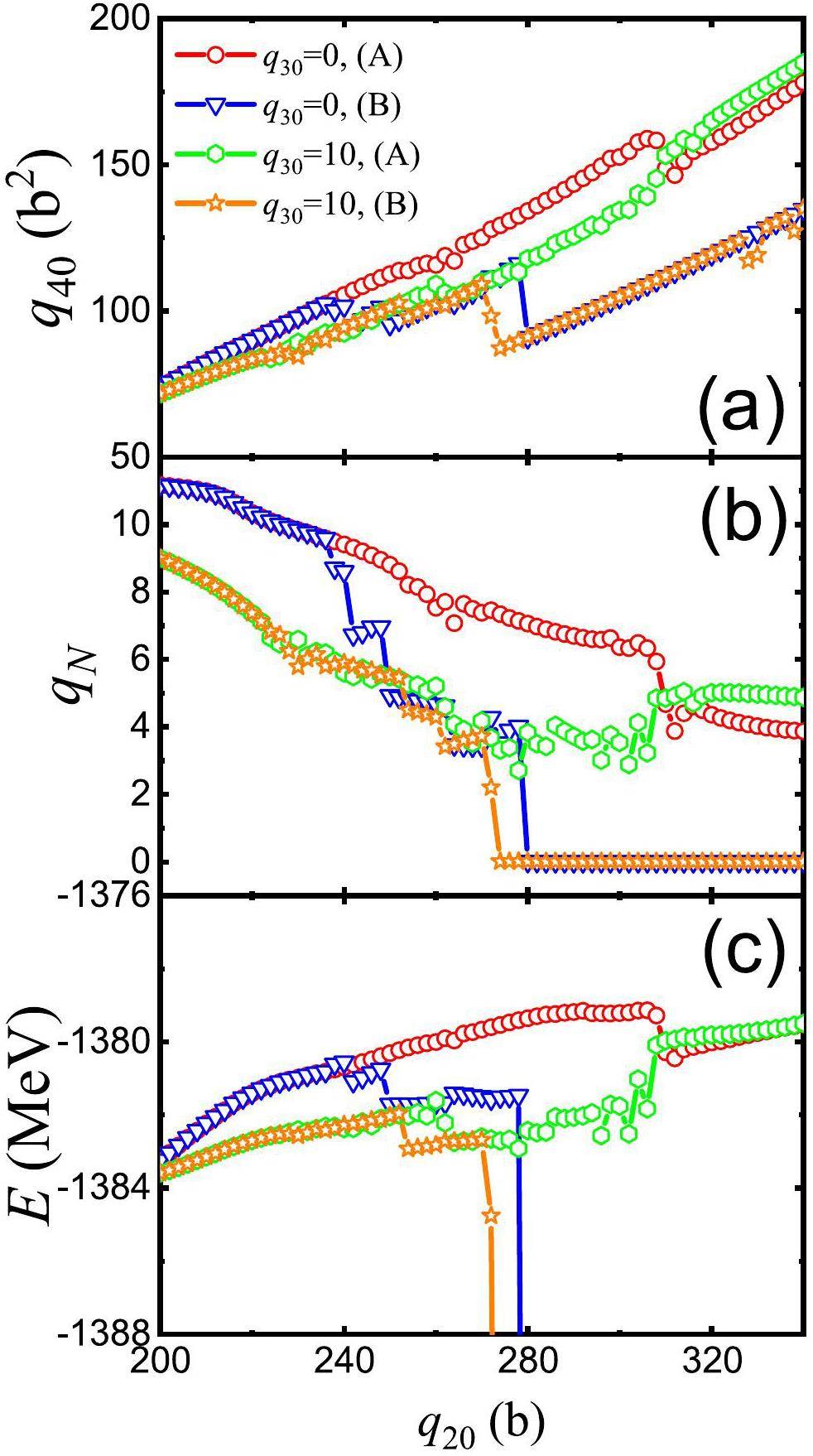

In Fig. 3, the hexadecapole moment (q40), the average particle number around the neck (qN), and the HFB energies are given as functions of q20 respectively, at a given q30. To investigate the role of q40, only the region with large q20 is shown. From Fig. 3(a), it can be seen that q40 increases nearly linearly until a very large q20 value, especially for case (A), in which q40 can become very large during elongation. After a “perturbative” constraint on q40, as the case (B) in the figure, the q40 value has sudden drop and then grow linearly. In studies of nuclear fission, qN is often adopted as an indicator of nuclear scission. For example, qN=4 was used for the determination of the scission line of 240Pu in Refs [40, 54, 69]. In Fig. 3(b), qN gradually decreases with q20. However, in case (A), the reduction in qN becomes rather slow with an increase in q20. In particular, at q20~340 b (

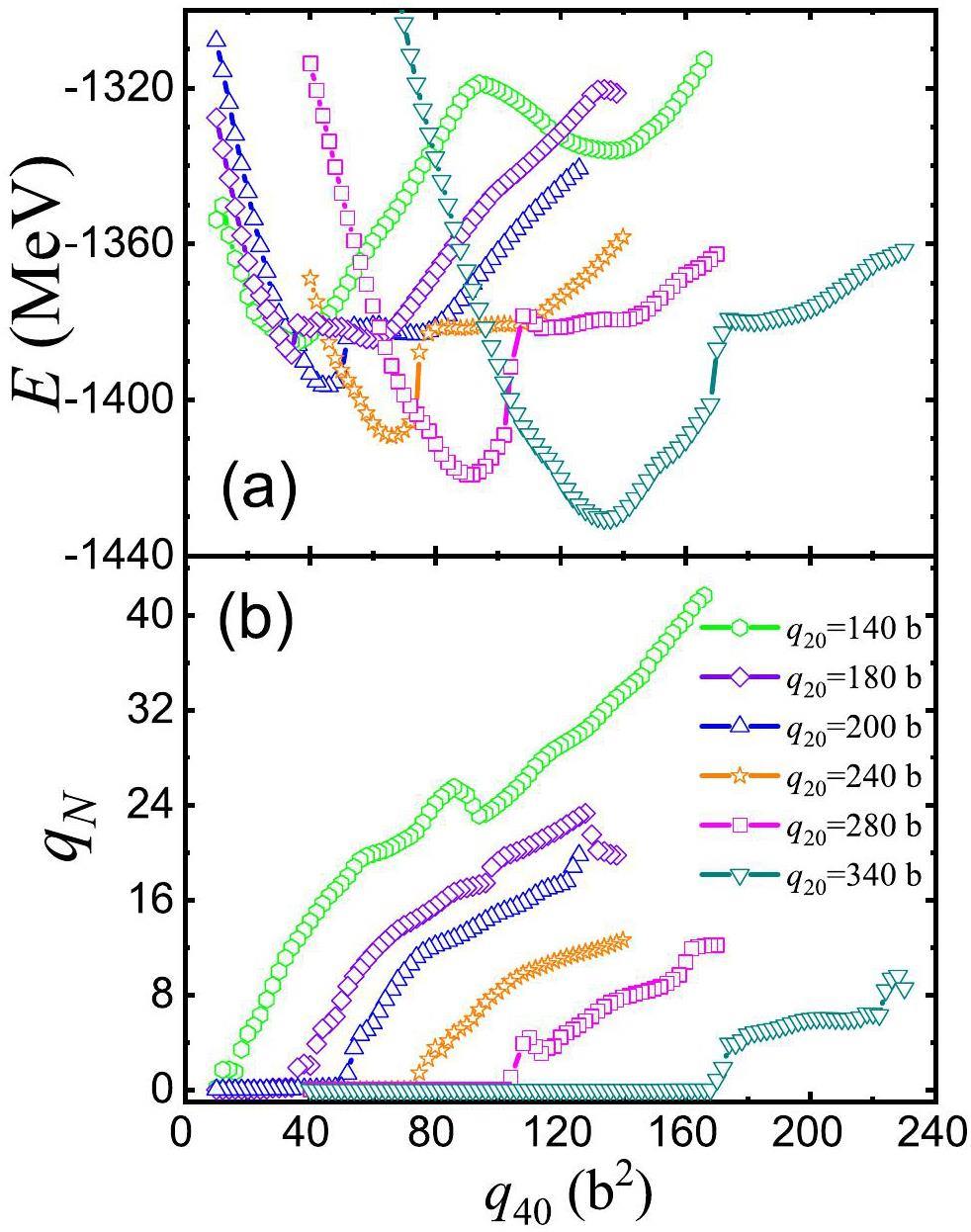

To investigate the role of q40 on PES, the HFB energies and qN against q40 at given q20 and q30 are plotted in Fig. 4, which were obtained through exact constrained calculations of q20, q30 and q40. In this figure, q30 is constrained to 0 b 3/2. The other q30 values were also tested, and the results were similar to those in Fig. 4. In Fig. 4(a), one can see that there are two local minima along q40 degrees of freedom, which correspond to distinct valleys on the multidimensional potential energy surface. In Ref. [56], a similar trend in 240Pu was found, and the minima related to the larger q40 disappeared with increasing quadruple deformation (at roughly

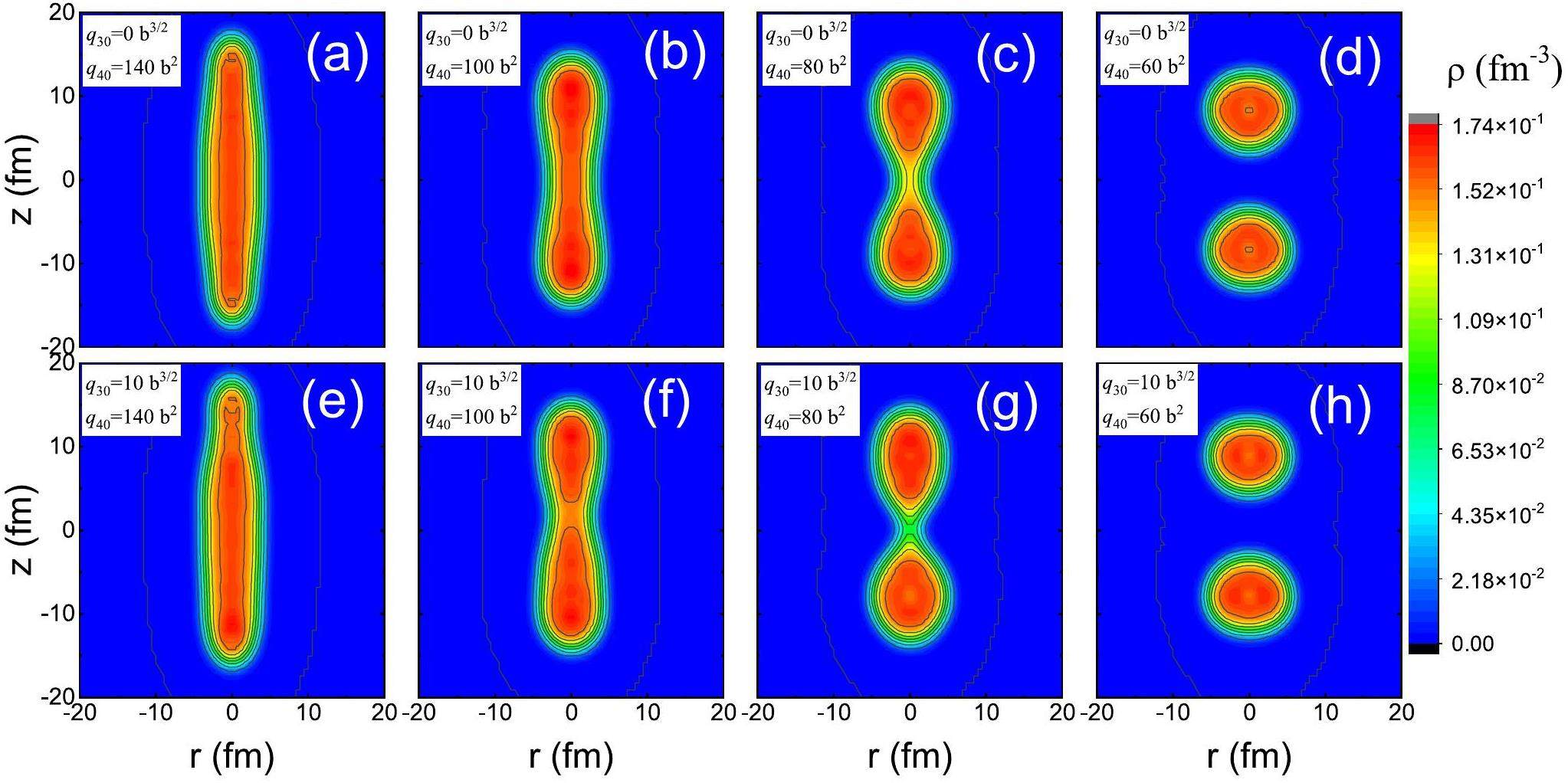

Several results of the (q20, q30, q40) constrained calculations are shown in Fig. 5 for the density distribution profiles of 180Hg. q20 is constrained to 240 b, and q40 changes from 140 b 2 to 60 b2 for q30 = 0 b3/2 and q30 = 10 b3/2 in the upper and lower panels, respectively. q40 degrees of freedom influenced the formation of neck and scission configurations. From the figure, it can be seen that, with a large q40, there is no neck in the nucleus, and the nucleus is stretched very long. For the calculation with only the (q20, q30) constraint, as in case (A) in Figs. 2 and 3, q40 has a very large value with an increase in q20 and thus, the nucleus cannot undergo scission. With a decrease in q40, the neck structure of the nucleus appears and becomes well separated when q40 has small values.

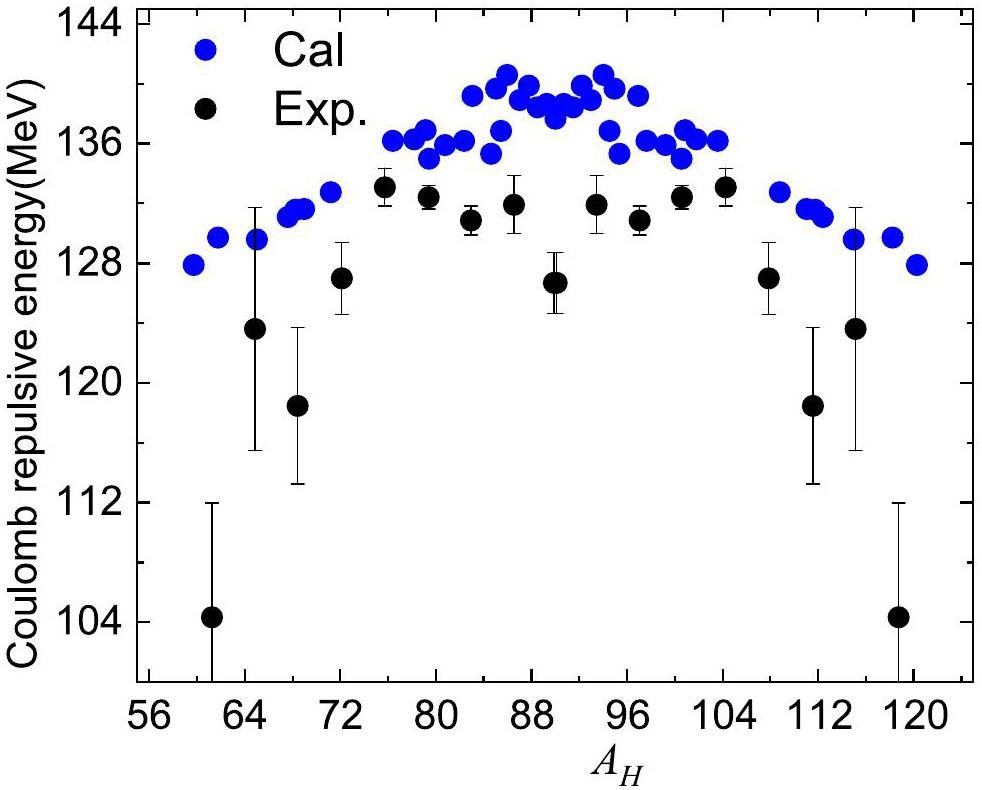

One of the most important quantities in induced fission is the total kinetic energy (TKE) carried out by the fission fragments. In this work, the total kinetic energy of the two separated fragments at scission point can be approximately estimated as the Coulomb repulsive interaction by using a simple formula

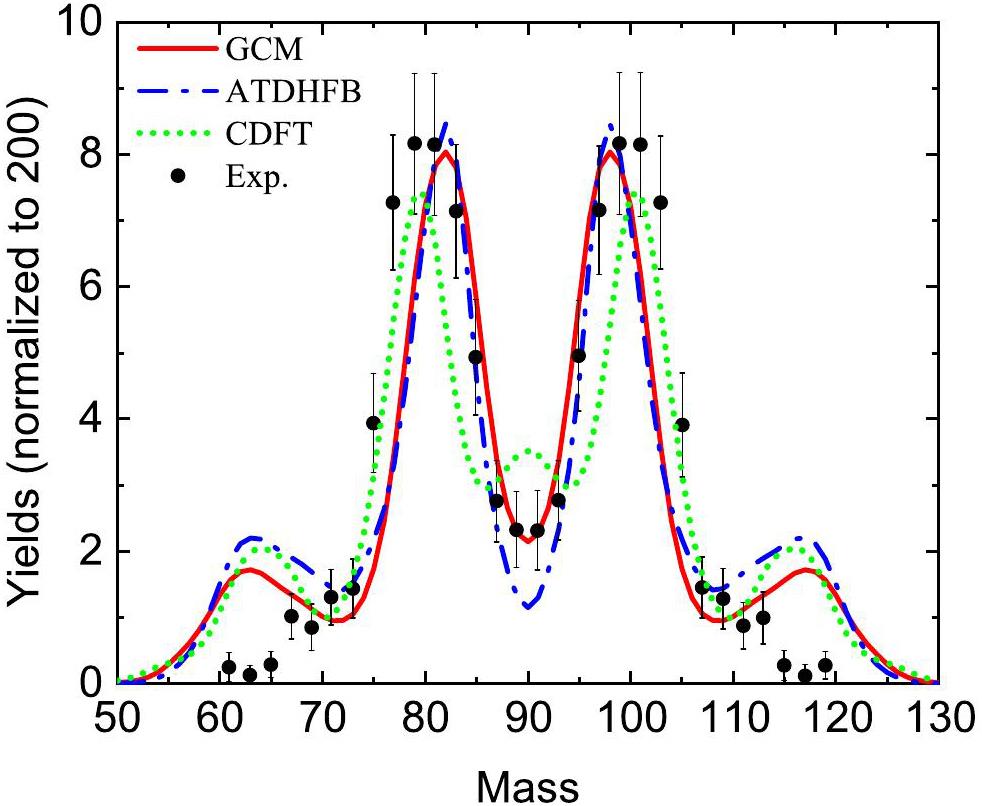

Finally, we performed TDGCM+GOA calculations to model the time evolution of the fission dynamics of 180Hg. Figure 7 shows the calculated mass distributions of the fission fragments of 180Hg compared with the experimental data [1, 2]. The theoretical results in the framework of covariant density functional theory (CDFT) using PES generated with the neck coordinate constraint qN from Ref. [9] are also given in the figure for comparison, denoted as “CDFT.” As one of the most important microscopic inputs of fission dynamic calculations, the mass tensor was calculated using the GCM or ATDHFB methods in the present work. The calculated mass distribution is generally similar when using the mass tensor by these two methods, and better agreement was obtained by using the GCM method for the height of asymmetric peaks and symmetric valleys. Overall, the calculations accurately reproduced the experimental data. The calculated peak position deviated by one unit from the experimental peak position. The results of CDFT show good asymmetric peak positions but overestimate the data and even predict a small peak for the symmetric valley. The deviation of the peak position from the data may have been caused by the mean-field potential. In the analysis of PES for 180Hg in Ref. [7], it was found that the mass of the optimum fission fragment at the static scission point varies by two units when using either the Skyrme force or the Gogny force. In the dynamic calculation results, discrepancies were observed in the peak positions between the results based on skyrme-DFT and CDFT. The tail of fission fragment distribution is sensitive to the approximation of the mass tensor in dynamic calculations. The width of the distribution becomes slightly wider when the GCM mass tensor is used. Moreover, a more asymmetric fission mode with AH ∼ 116–117 was predicted in both this work and the CDFT calculation. As explained in Ref. [9], this mode resulted from the use of the initial state with mixed angular momenta, whereas in the experiment, there were only certain values owing to the selection rule of electron capture of 180Tl. In the current study, these discrepancies from the data still exist as the initial state with mixed angular momenta.

Summary

In this study, the static fission properties and fission dynamics of 180Hg were investigated using Skyrme DFT and TDGCM, respectively. During the calculation of the multi-dimensional PES, it was found that the hexadecapole moment is crucial for obtaining a smooth PES and proper scission configurations; thus, it is essential for fission dynamic studies. For the calculation of PES with only the q20 and q30 constraints, nuclear rupture does not occur, even at a very large q20. Through calculations with q20, q30 and q40 constraints, it was found that a rather soft and flat minimum with a large hexadecapole moment still exists in the PES of 180Hg even with a very elongated shape, which hinders the transition to the lower energy minimum with a smaller q40. With the strategy of “perturbative” constraint of the collective freedom q40, the transition to the minimum corresponding to the nuclear rupture could happen naturally, and thus reasonable scission configurations can be obtained. From these scission configurations, the estimated distribution of the TKE reproduced the trend of the experimental data.

Based on the static PES calculation, the asymmetric fission channel is favored in 180Hg. Finally, the fission fragment yields were calculated using TDGCM. The calculated mass distributions also support asymmetric fission for 180Hg. This calculation agrees well with the experimental data. Moreover, a more asymmetric peak with AH ∼ 117 was predicted, which was also predicted by covariant DFT with the PC-PK1 parameter set [9].

New Type of Asymmetric Fission in Proton-Rich Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,β-delayed fission of 180Tl

, Phys. Rev. C 88,Contrasting fission potential-energy structure of actinides and mercury isotopes

. Phys. Rev.C 86,Mass distributions for induced fission of different Hg isotopes

. Phys.Rev. C 86,Calculated fission yields of neutron-deficient mercury isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 85,On shape coexistence and possible shape isomers of nuclei around 172Hg

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 128 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01737-wFission modes of mercury isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Excitation-energy dependence of fission in the mercury region

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Microscopic study on asymmetric fission dynamics of 180Hg within covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Calculated fission-fragment yield systematics in the region 74≤ Z ≤94 and 90≤ N ≤150

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Description of the two-humped mass distribution of fission fragments of mercury isotopes on the basis of the multidimensional stochastic model

. Phys. At. Nucl. 77, 167 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.91.044316Isospin dependence of mass-distribution shape of fission fragments of Hg isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Role of deformed shell effects on the mass asymmetry in nuclear fission of mercury isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Influence of octupole deformed shell structure on the asymmetric fission of mercury isotopes

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 244 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01456-7Fission fragment mass yield deduced from density distribution in the pre-scission configuration

. Phys. Scr. 90,Disintegration of Uranium by Neutrons: a New Type of Nuclear Reaction

. Nature (London) 143, 239 (1939). https://doi.org/10.1038/143239a0The Mechanism of Nuclear Fission

. Phys. Rev. 56, 426 (1939). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.56.426Evaluation of pre-neutron-emission mass distributions of neutron-induced typical actinide fission using scission point model

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Pre-neutron fragment mass yields for 235U(n,f) and 239Pu(n,f) reactions at incident energies from thermal up to 20 MeV

. Chin. Phys. C 47,Calculation of the energy dependence of fission fragments yields and kinetic energy distributions for neutron-induced 235U fission

. Chin. Phys. C 48,Verification of neutron-induced fission product yields evaluated by a tensor decompsition model in transport-burnup simulations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 32 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01176-5Theoretical analysis of long-lived radioactive waste in pressurized water reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00911-0Nuclear fission modes and fragment mass asymmetries in a five-dimensional deformation space

. Nature (London) 409, 785 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/35057204Manifestation of clustering in the 252Cf(fs) and 249Cf(n_th,f) reactions

. Nuclear Phys. A 624, 140(1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)00417-XStability of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Mass yields of fission fragments of Pt to Ra isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Pairing effects on the fragment mass distribution of Th, U, Pu, and Cm isotopes

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 173 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01316-xStudy of fission dynamics with a three-dimensional Langevin approach

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Analysis of nuclear fission properties with the Langevin approach in Fourier shape parametrization

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Influence of the neck parameter on the fission dynamics within the two-center shell model parametrization

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Calculation of fission potential energy surface and fragment mass distribution based on fourier nuclear shape parametrization

. Atomic Energy Science and Technology. 55, 2290-2299 (2021). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2021.youxian.0614 (in Chinese)Energy dependence of fission product yields in 235U(n,f) within the Langevin approach incorporated with the statistical model

. Chin. Phys. C 49,Fission barriers of Actinide isotopes in the exactly solvable pairing model

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 40, 502 (2023). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.40.2023013.Self-consistent calculations of fission barriers in the Fm region

. Phys. Rev. C 66,Triaxial angular momentum projection and configuration mixing calculations with the Gogny force

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Microscopic description of oblate-prolate shape mixing in proton-rich Se isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Fission modes of 256Fm and 258Fm in a microscopic approach

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Energy density functional analysis of the fission properties of 240Pu: The effect of pairing correlations

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Microscopic study of neutron-induced fission process of 239Pu via zero- and finite-temperature density functional theory

. Chin. Phys. C 47,Sensitivity impacts owing to the variations in the type of zero range pairing forces on the fssion properties using the density functional theory

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01422-4Energy and pairing dependence of dissipation in real-time fission dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Fission dynamics of compound nuclei: Pairing versus fluctuations

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Investigation of the impact of pairing correlations on the nuclear fission process based on the energy density functional theory

. Nucl. Phys. Rev 41, 127 (2024). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.41.2023CNPC84.Microscopic analysis of induced nuclear fission dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Fission dynamics, dissipation, and clustering at finite temperature

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Time-dependent density functional theory study of induced-fission dynamics of 226Th

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Microscopic description of nuclear shape evolution from spherical to octupole-deformed shapes in relativistic mean-field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Microscopic study of induced fission dynamics of 226Th with covariant energy density functionals

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Three-dimensional potential energy surface for fission of 236U within covariant density functional theory

. Chin. Phys. C 47,Microscopic self-consistent description of induced fission: Dynamical pairing degree of freedom

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Description of the multidimensional potential-energy surface in fission of 252Cf and 258No

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Numerical search of discontinuities in self-consistent potential energy surfaces

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 2035 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2012.05.001From asymmetric to symmetric fission in the fermium isotopes within the time-dependent generator-coordinate-method formalism

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Description of induced nuclear fission with Skyrme energy functionals: Static potential energy surfaces and fission fragment properties

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Microscopic analysis of collective dynamics in low energy fission

. Nucl. Phys. A 428, 23 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(84)90240-9Role of hexadecapole deformation in fission potential energy surfaces of 240Pu

. Nucl. Phys. A 1032,Fission fragment charge and mass distributions in 239Pu(n,f) in the adiabatic nuclear energy density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Self-consistent mean-field models for nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 121 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.75.121Time-dependent quantum collective dynamics applied to nuclear fission

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 63, 365 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-4655(91)90263-KMicroscopic and nonadiabatic Schrödinger equation derived from the generator coordinate method based on zero- and two-quasiparticle states

. Phys. Rev. C 84,FELIX-2.0: New version of the finite element solver for the time dependent generator coordinate method with the Gaussian overlap approximation

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 225, 180 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2017.12.00Local density approximation for proton-neutron pairing correlations: Formalism

. Phys. Rev. C, 69,Time-odd components in the mean-field of rotating superdeformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 1827 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.1827Microscopic theory of nuclear fission: a review

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79,Axially deformed solution of the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock-Bogolyubov equations using the transformed harmonic oscillator basis (III) hfbtho (v3.00): A new version of the program

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 220, 363 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2017.06.022Towards a better parametrisation of Skyrme-like effective forces: A critical study of the SkM force

. Nucl. Phys. A 386, 79 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90403-1Comparison of self-consistent Skyrme and Gogny calculations for light Hg isotopes

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 19, 787 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301310015230Fission of 180Hg and 264Fm: a comparative study

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 192 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01415-2Role of pairing correlations in the fission process

. Phys. Rev. C 108,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.