Introduction

Standard Model (SM) [1, 2] of particle physics, including the unified electroweak (EW) and quantum chromodynamics (QCD) theories, has successfully explained nearly all experimental results in the microscopic world. However, several open questions remain, such as the baryon asymmetry of the universe, dark matter, neutrino masses, and the number of fermion flavors.

The Beijing Electron-Positron Collider II (BEPCII) and the Beijing Spectrometer (BESIII) [3] constitute the only multi-GeV

STCF will operate at a center-of-mass energy of 2-7 GeV with a peak luminosity exceeding

For instance, the weak decays of Λ and Ξ hyperons provide promising channels for searching for new sources of CP violation [7-9]. Additionally, hyperon samples at STCF can be used to measure time-like nucleon and hyperon form factors for Q2 values up to 40 GeV2 [5]. However, reconstructing the trajectories of long-lived particle decay products is challenging, as these particles may decay inside or outside the inner tracker, resulting in a limited number of hits recorded.

The Kalman Filter (KF) [10] algorithm is commonly used for tracking in HEP and nuclear physics [11]. The Combinatorial Kalman Filter (CKF) [12, 13] is an extended version of the KF, in which measurements are progressively added during track propagation, guided by an initial estimate of the track parameters (the seed). The CKF accounts for magnetic field effects and material interactions during propagation, thereby enabling it to resolve hit ambiguities in high-density tracking environments. Consequently, CKF has been deployed in experiments such as ATLAS [14] and CMS [15], where thousands of tracks may be present in a single event. It also served as the primary track-finding algorithm in the Belle II experiment [16]. More recently, the CKF algorithm developed at Belle II has been adapted [17] to study tracking performance at the Circular Electron-Positron Collider (CEPC) [18].

Despite its advantages, a known limitation of KF-based tracking algorithms is their dependence on the quality of the seeding algorithm, which may result in reduced performance for long-lived particles. A track-finding algorithm based on the Hough Transform, previously used in the Belle II [19] and BESIII experiments [20], was recently developed for STCF [21]. Its performance has been studied primarily for prompt particles without vertex displacement, showing promising results and strong robustness against local hit inefficiencies. However, tracking efficiency at low transverse momentum may deteriorate in the presence of background hits.

The A Common Tracking Software (ACTS) [22, 23] is an emerging open-source toolkit for HEP and nuclear physics experiments. It offers detector-agnostic, framework-independent, modular algorithms for track and vertex reconstruction. The strong performance of KF and CKF algorithms within ACTS has been demonstrated through their adoption in experiments such as FASER [24], sPHENIX [25], and several R&D projects at STCF [26] and BESIII [27]. Notably, ACTS has shown general applicability across various types of tracking detectors [28]. However, its performance in reconstructing long-lived particles has not yet been studied in detail.

In this study, we evaluate the tracking performance at STCF using a fully gaseous tracking system comprising a μ-RWELL [29]-based inner tracker and a drift chamber. We investigate the combination of the Hough Transform and the ACTS CKF to enhance track finding for long-lived particles.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the STCF detector. Section 3 introduces the tracking workflows using different algorithms. Section 4 presents the tracking performance for a benchmark process involving long-lived particles at STCF. Section 5 offers concluding remarks.

STCF detector

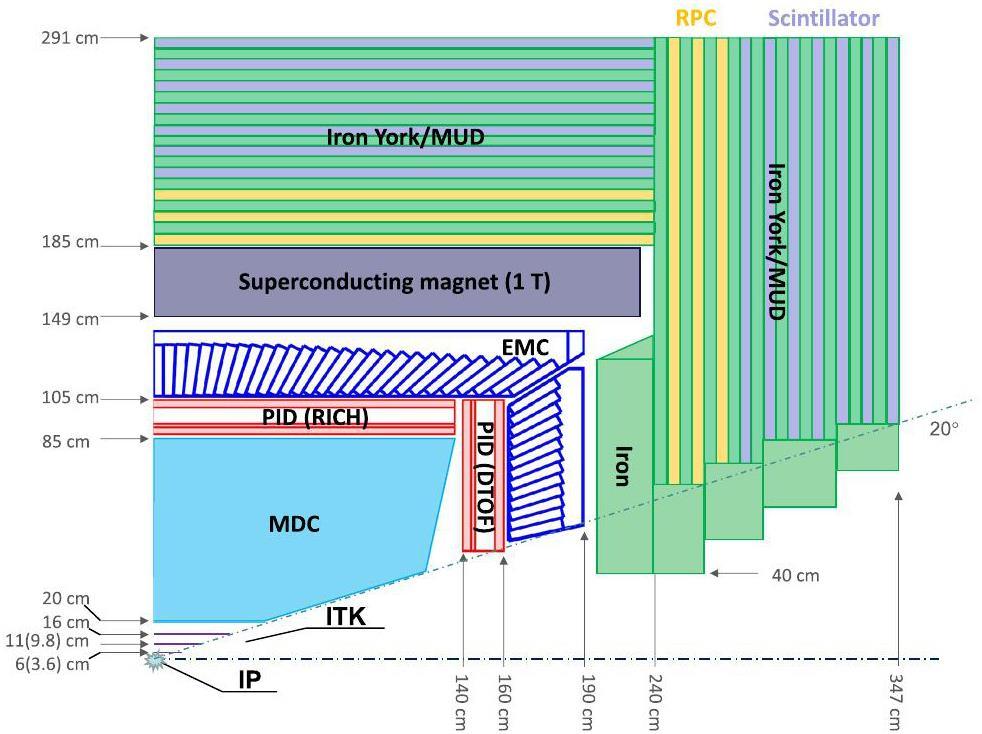

The STCF detector [5] provides comprehensive coverage of the solid angle surrounding the collision point, as illustrated in Fig. 1. It consists of a tracking system composed of an Inner Tracker (ITK) and a Main Drift Chamber (MDC), along with a ring-imaging Cherenkov (RICH) detector [30] and a DIRC-like Time-of-Flight (DTOF) detector [31] for particle identification in both the barrel and endcap regions. Additionally, the detector includes a homogeneous electromagnetic calorimeter (EMC) [32], a superconducting solenoid magnet generating a 1 Tesla axial magnetic field, and a Muon Detector (MUD) positioned at the outermost layer of the system.

To ensure optimal tracking efficiency for low-momentum charged particles, the ITK covers a polar angle range of 20° to 160° (i.e. |cosθ| < 0.94) and consists of three layers of low-material-budget silicon or gaseous detectors, using either MAPS- or μ-RWELL-based technology [29]. This study focuses on the μ-RWELL-based ITK, where the three layers are placed at inner radii of 60, 110, and 160 mm, respectively. Each layer has a thickness of approximately 6.5 mm and provides a spatial resolution of about 100 μm in the r-ϕ direction and approximately 400 μm in the z direction.

For the MAPS-based ITK, the radii of the three silicon layers are 36, 98, and 160 mm, respectively, and a hit resolution of 30 μm × 180 μm is assumed. Unless otherwise specified, ITK refers to the μ-RWELL-based configuration by default.

At the core of the STCF tracking system, the Main Drift Chamber (MDC) operates with a He/C3H8 (60/40) gas mixture and features a square-cell structure with a superlayer-wire arrangement. The superlayers alternate between stereo layers (“U” or “V”) and axial layers, each composed of six layers. The MDC consists of eight superlayers in the configuration AUVAUVAA, totaling 48 layers, with inner and outer radii of 200 mm and 850 mm, respectively. It provides spatial resolutions ranging from 120 μm to 130 μm.

Track reconstruction using combined Hough Transform and CKF

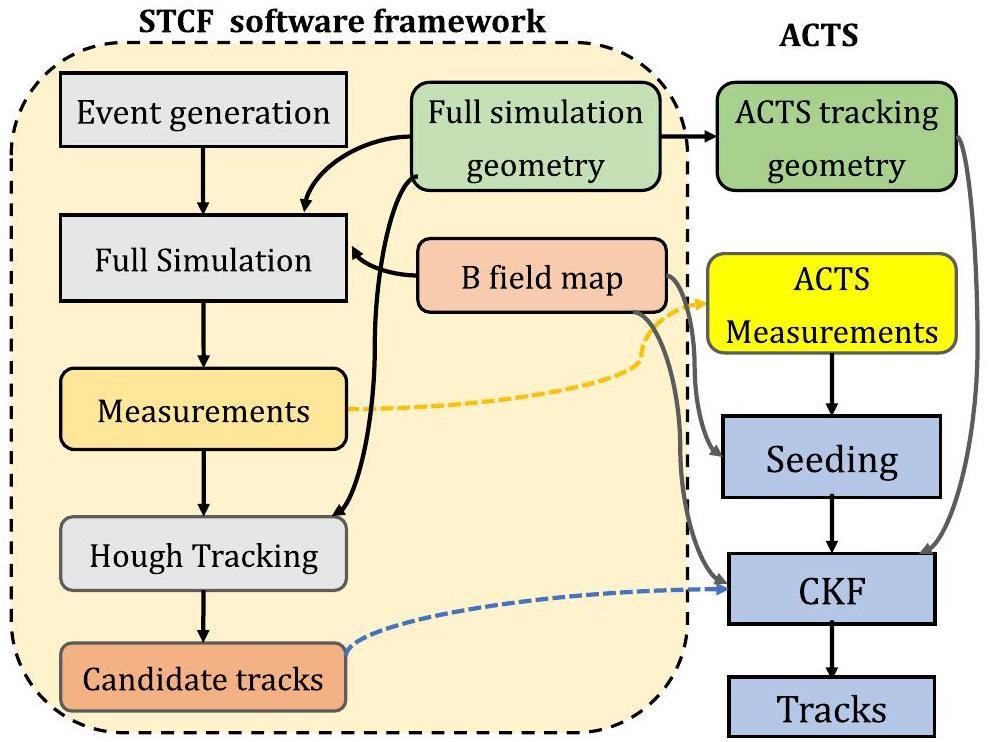

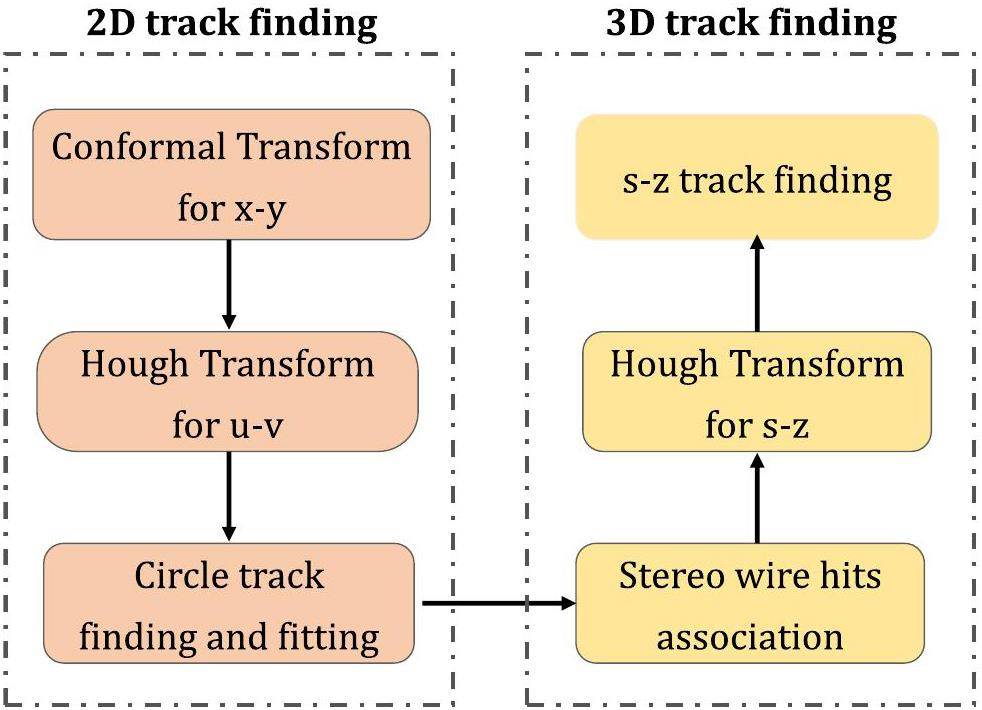

The workflow for track reconstruction using the combined Hough Transform and ACTS CKF is illustrated in Fig. 2. The ACTS CKF is used to identify track candidates by performing track fitting, guided by initial track parameters provided by either the ACTS seeding algorithm or the Hough Transform algorithm developed within the STCF offline software.

Interface between STCF offline software and ACTS

The offline software system of the Super Tau-Charm Facility (OSCAR) [33, 34] serves as the event-processing framework for STCF. It provides core services for data handling and a suite of application tools for event generation, simulation, reconstruction, and physics analysis. For simulation, τ-charm physics processes generated by KKMC [35] are incorporated into OSCAR, and particle decays are modeled with EvtGen, as used in the BESIII experiment [36] – both integrated into the framework.

The STCF detector geometry is defined using the Detector Description Toolkit (DD4hep) [37], with geometric parameters stored in compact XML [38] files. To comprehensively simulate particle interactions with the detector, Geant4 [39] is integrated into OSCAR for full simulation. A track-finding algorithm based on the Hough Transform was developed for use within OSCAR.

The interface between OSCAR and ACTS enables conversion of experimental geometry, measurements, and initial track estimates into ACTS-compatible representations. Geometry plugins in ACTS facilitate this conversion from DD4hep or TGeo [40] formats into ACTS’s internal geometry description. For the ITK, the readout units in each μ-RWELL layer are converted into sensitive cylindrical surfaces. For the MDC, each sense wire in a drift cell is transformed into a line surface.

Dedicated material mapping tools within ACTS are employed to project detailed material properties onto auxiliary internal surfaces of the ACTS geometry. Two ROOT [41]-based readers were developed to convert simulation data: one extracts simulated hits from the full simulation and converts them into ACTS measurements with detector resolution taken into account; the other converts the initial track parameter estimates from the Hough Transform into ACTS track parameters.

ACTS seed finding

The seeding algorithm in ACTS identifies a minimal set of measurements that provide the global (x, y, z) coordinates for a particle to initiate the track-finding process. Without a seed, a track cannot be reconstructed; hence, the goal is to identify at least one seed per particle within the detector acceptance.

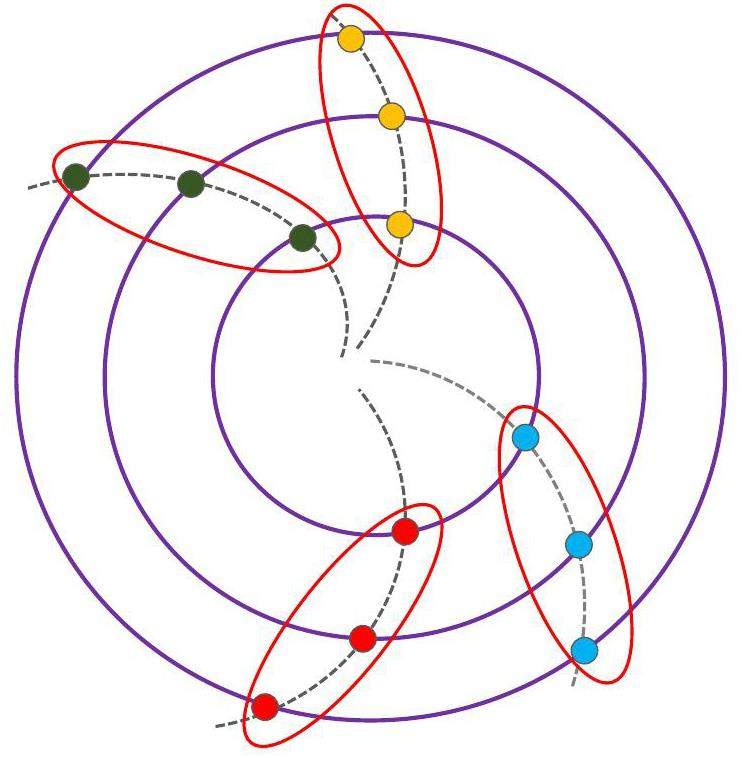

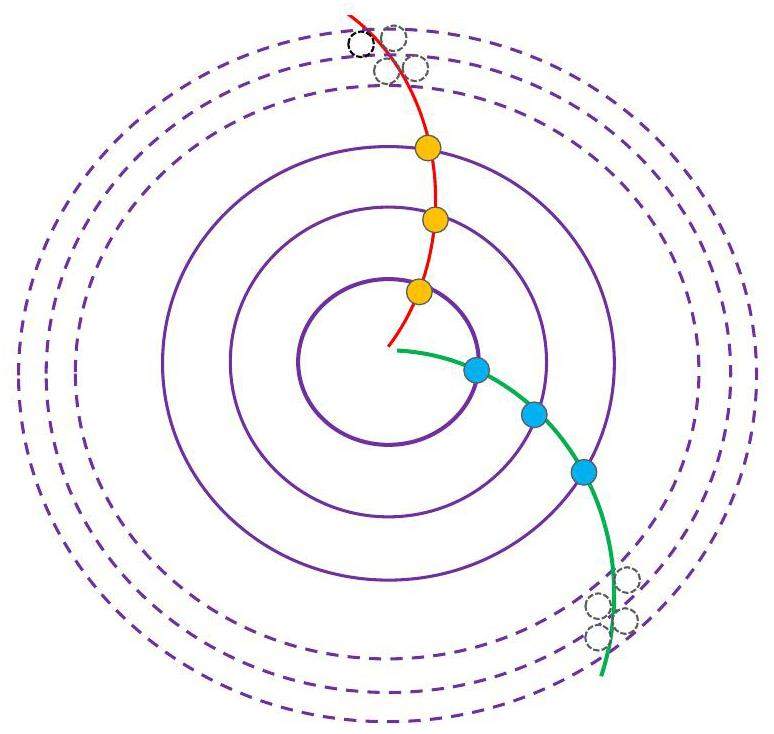

In a uniform magnetic field along the global z-axis, the helical trajectory of a charged particle can be accurately defined using three measurements, forming a seed. At STCF, seeds are generated by combining one compatible measurement from each of the three ITK layers, as shown in Fig. 3. For each seed candidate, the curvature and center of the projected circle on the x-y plane are determined using the Conformal Transform [42, 43]. These parameters are then used to compute the transverse momentum and transverse impact parameter, which must meet criteria optimized for relevant physics processes.

Additionally, the bending of the seed in the r-z plane must remain below a threshold optimized based on the effects of the magnetic field and multiple scattering. For further details on ACTS seeding, see Ref. [44].

Track finding with Hough Transform

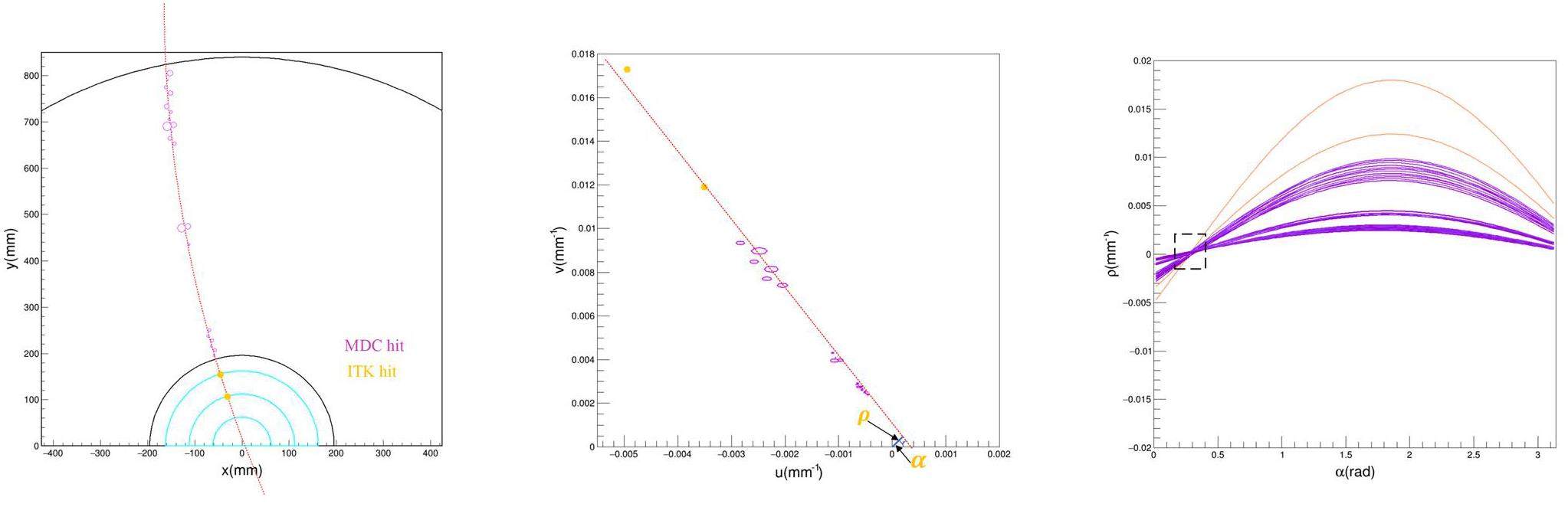

The principle of the Hough Transform for tracking is illustrated in Fig. 4. In the presence of a magnetic field along the global z axis, the projection of a track onto the transverse x-y plane forms a circle, while its projection onto the s-z plane (where s is the path length in the x-y plane) forms a straight line. The Conformal Transform converts the circular projection of a track that passes through the origin into a straight line in the conformal u-v space. A drift circle tangent to the projected track is also transformed into another circle tangent to the line in the u-v space.

For displaced tracks with a small but nonzero transverse impact parameter d0 (compared with the projected track radius in the x-y plane), the trajectory of the transformed measurements (points or drift circles) in the conformal space can be approximately represented by a straight line, as shown in the middle panel of Fig. 4.

The Hough Transform operates on the principle that a straight line in either the geometrical or conformal space can be described by two parameters: the angle θ of its normal and its algebraic distance ρ from the origin. A point with coordinates (u, v) on the line can be mapped to a sinusoidal curve in Hough space using:

The track-finding workflow using the Hough Transform in OSCAR is illustrated in Fig. 5. First, measurements from the ITK and MDC axial wires are used to reconstruct 2D track projections in the x-y plane, followed by circle fitting to extract their parameters. These 2D tracks are then associated with candidate measurements from MDC stereo wires. The z-position and path length s at each stereo wire are simultaneously estimated. Since each stereo wire yields two possible z-position solutions and may include incorrectly assigned hits, a second application of the Hough Transform is used to identify tracks in the s-z plane. Further details can be found in Ref. [21].

Track finding with ACTS CKF

Beginning with a set of initial track parameters, the ACTS CKF uses the ACTS track propagator to search for compatible measurements on a given surface through KF track fitting, as illustrated in Fig. 6. This iterative process, also referred to as track-following, associates the best-matching measurement with the track and updates the track parameters accordingly for continued propagation.

Performance studies

Monte-Carlo samples

The decay process

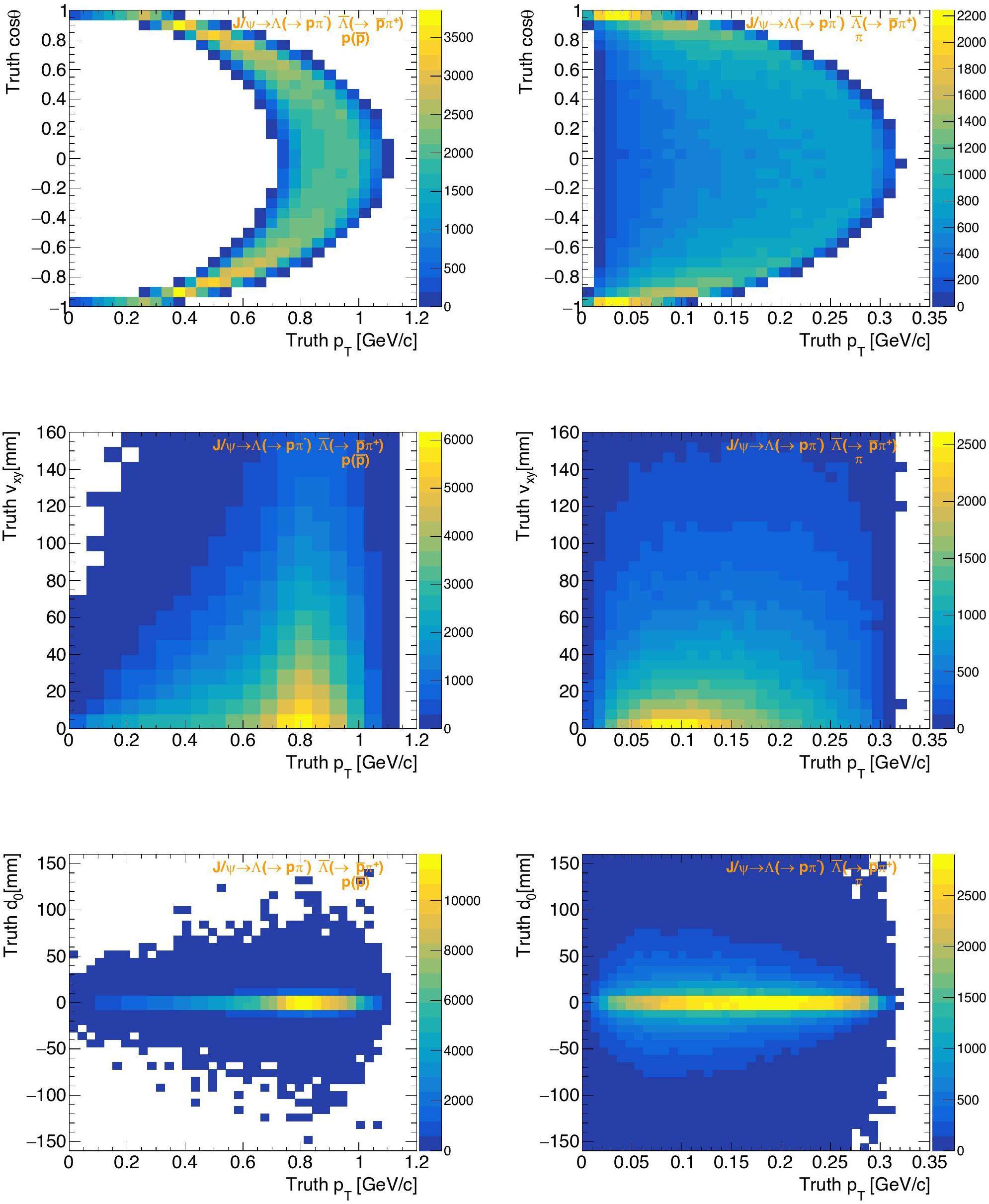

Figure 7 shows the 2D distributions of cosθ versus pT, vertex displacement in the x-y plane Vxy versus pT, and transverse impact track parameter d0 versus pT, for protons (and anti-protons), denoted as

A significant fraction of particles decay outside the first layer of the ITK. However, most reconstructed tracks have d0 values smaller than the radius of the first ITk layer, especially for

Following event generation, Geant4 was used to simulate hits from final-state particles, which originated from primary interactions and traversed the STCF tracking system under a uniform 1 T magnetic field. Detector measurements were then obtained by applying Gaussian smearing to the simulated hit positions, using zero mean and widths determined by the detector resolution.

Track-finding performance

The performance of track finding – comprising seed finding using either the ACTS seeding algorithm or the Hough Transform algorithm in the first stage, and track following using ACTS CKF in the second stage – was studied.

Considering the acceptance of the STCF tracking system, only truth particles with pT above 50 MeV/c and |cosθ| below 0.94 were included in the performance evaluation. This evaluation involves identifying the primary particle [22] of a seed or a track, i.e., the simulated particle contributing the most hits to that seed or track.

The seeding process serves as the initial step in track finding using the CKF and ideally should provide seeds for all particles within the detector acceptance. The ACTS seeding efficiency is defined as the fraction of particles within the acceptance region whose seeds are matched to hits originating from the same particle in all three ITK layers. For the Hough Transform, seeding efficiency is defined as the fraction of seeds with at least 50% of hits originating from the same primary particle.

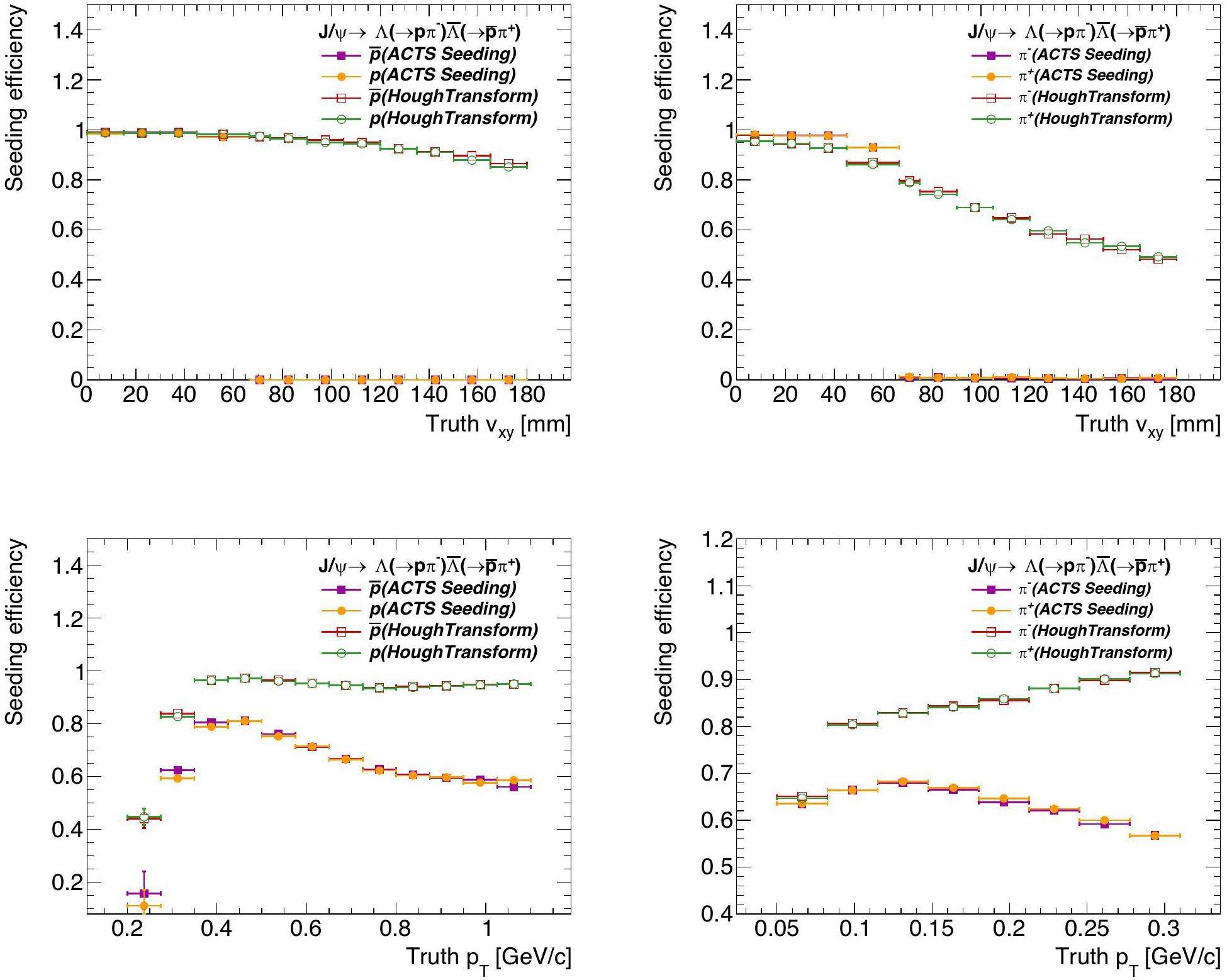

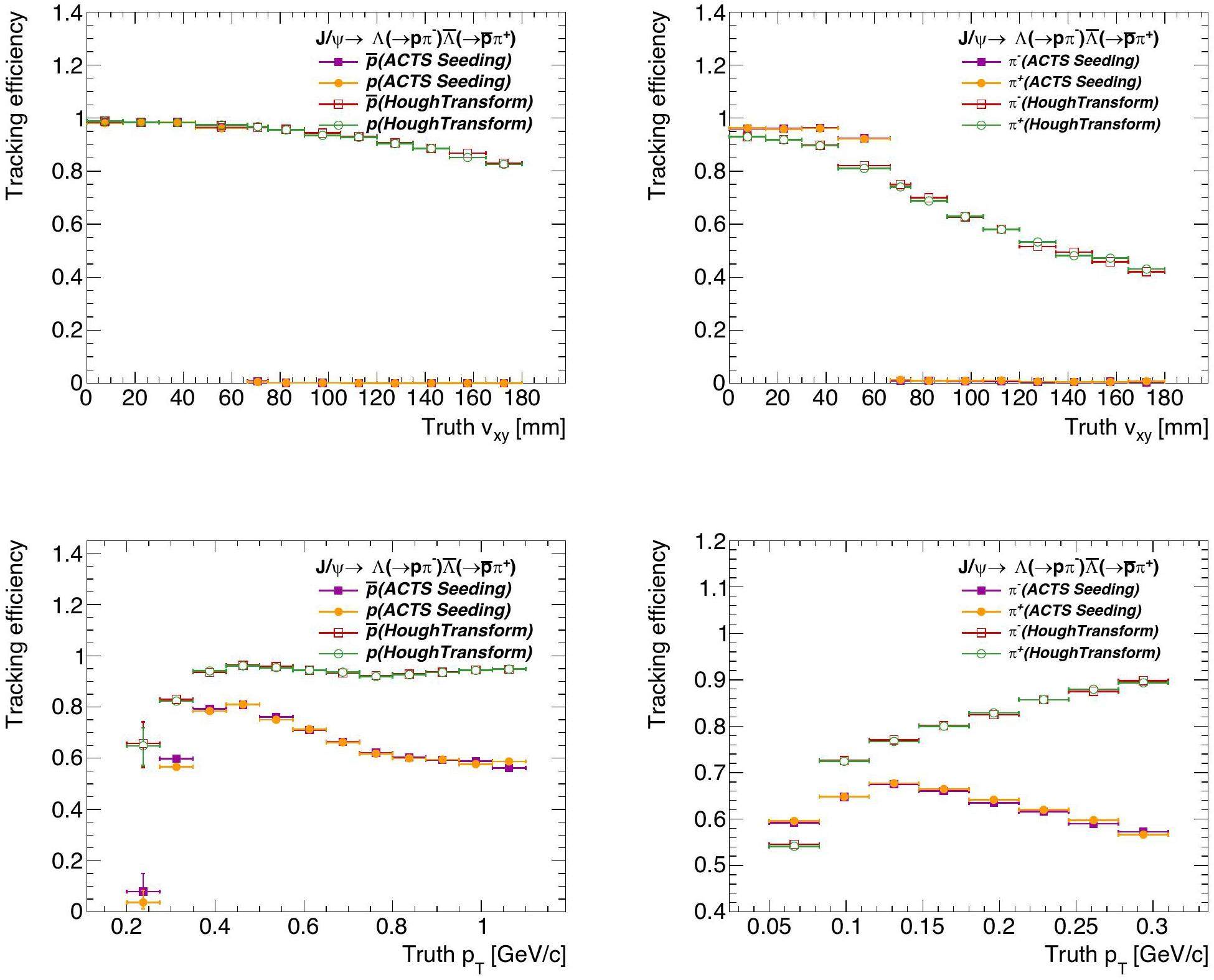

ACTS seeding is only possible for tracks from particles that produce hits in all three ITK layers, which corresponds to a vertex displacement below 66.5 mm. A comparison of the efficiencies of ACTS seeding and the Hough Transform as a function of vertex displacement in the x-y plane (Vxy) is shown in Fig. 8 (top panels). ACTS seeding efficiency approaches 100% when there are at least three ITK measurements. In particular, ACTS seeding provides higher efficiency than the Hough Transform for π with small Vxy. However, ACTS efficiency drops sharply to zero if fewer than three ITK hits are present, highlighting a key limitation for long-lived particles. In contrast, the Hough Transform, functioning as a global tracking algorithm, shows reduced sensitivity to the number of ITK layers traversed.

Figure 8 (bottom panels) shows seeding efficiency as a function of particle pT. The Hough Transform achieves over 90% efficiency for

Reconstructed tracks are required to have at least five measurements and reconstructed |cosθ| < 0.94. A track is matched to its primary particle if at least 50% of its hits originate from that particle (track purity). A track not matched to its primary particle is labeled as fake. If multiple tracks match the same simulated particle, the one with the highest purity is considered the true track, and others are labeled as duplicates.

Track reconstruction efficiency is defined as the fraction of simulated particles (with at least five hits in the detector acceptance) that are matched to reconstructed tracks. The fake rate is the fraction of fake tracks among all reconstructed tracks. The duplication rate is the fraction of particles with at least one duplicate track among those with five or more simulated hits.

Figure 9 shows the tracking efficiency as a function of particle Vxy and pT. As expected, tracking efficiency using ACTS seeding with CKF drops to zero when Vxy exceeds 66.5 mm. In contrast, tracking with the Hough Transform and CKF shows weaker dependence on Vxy, achieving above 80% for

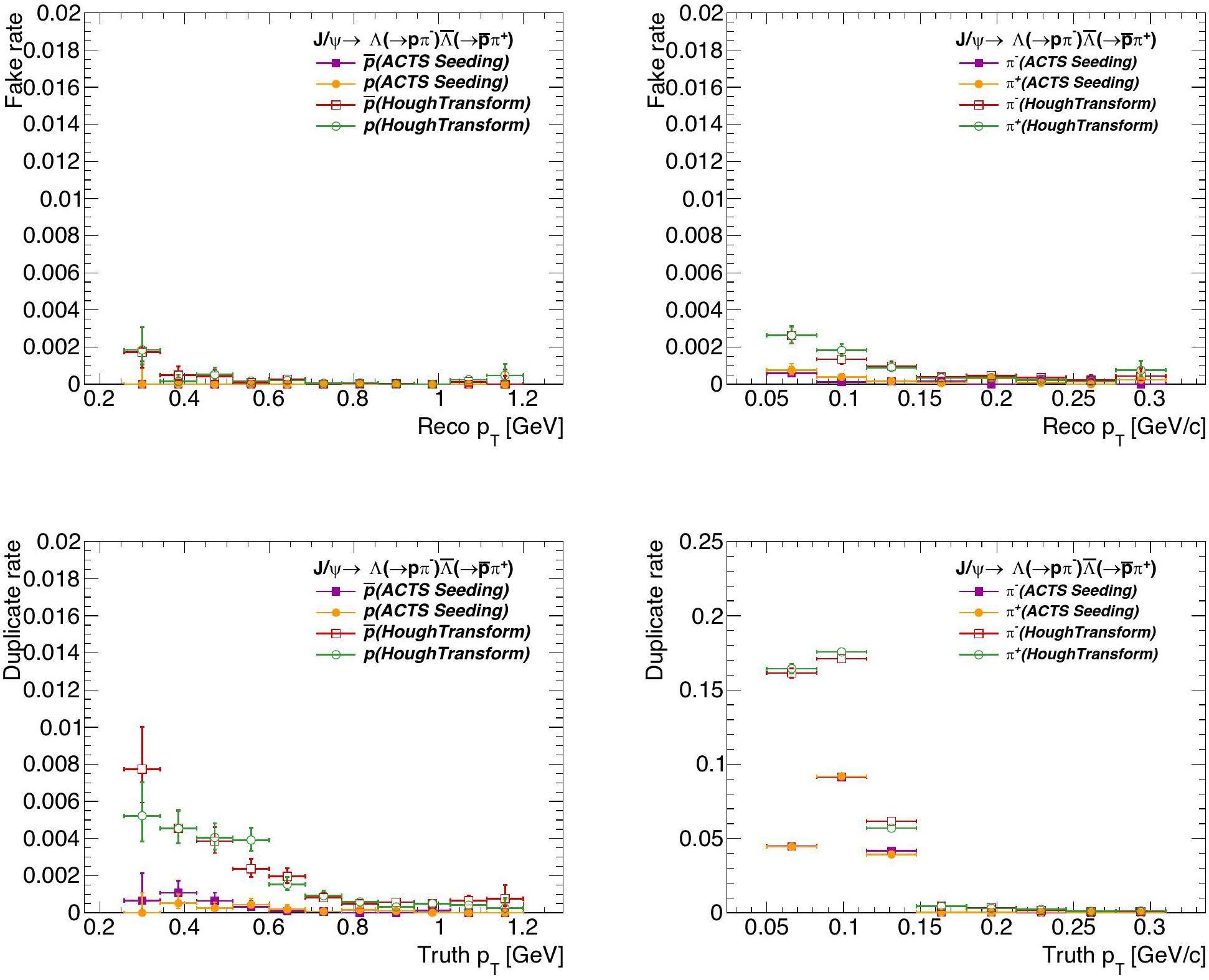

Figure 10 presents the fake and duplicate rates for the two seeding strategies. The fake rate remains below 0.4%. A non-negligible number of duplicate tracks appear for particles with pT below 150 MeV/c due to looping trajectories in the magnetic field. ACTS seeding yields lower fake and duplicate rates compared to Hough Transform seeding.

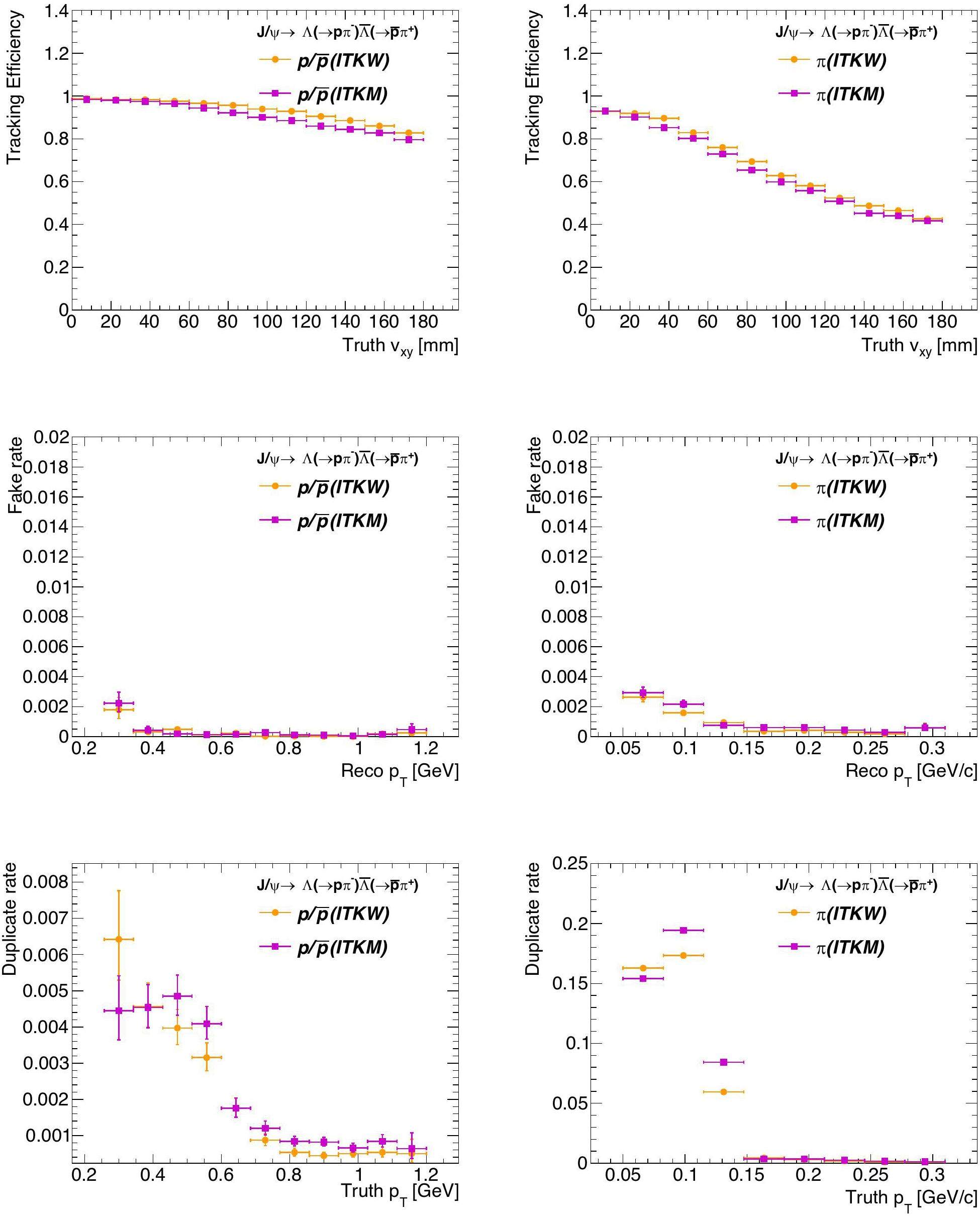

The tracking performance of an alternative MAPS-based ITK was compared to that of a μ-RWELL-based ITK for long-lived particles. Figure 11 shows the tracking efficiency, fake rate, and duplication rate using the combined Hough Transform and ACTS CKF for both designs. Due to its smaller radii in the first two layers, the MAPS-based ITK is less effective for long-lived particles and shows slightly lower tracking efficiency than the μ-RWELL-based ITK. However, fake and duplicate rates are similar between the two designs.

Conclusion

Processes involving long-lived particles offer opportunities to probe CP violation, strong interactions, and related phenomena at the future STCF. However, achieving high-performance track reconstruction for long-lived particles presents significant challenges for the STCF tracking system. The CKF is one of the most widely used track-finding algorithms in HEP experiments, and its performance is highly dependent on that of the seeding algorithm.

For long-lived particles, CKF using traditional seeding strategies – typically based on measurements from the inner detectors – exhibits considerable performance degradation. In this study, we evaluate for the first time the combined performance of the Hough Transform as a seeding algorithm for the ACTS CKF within the STCF offline software framework. The performance was assessed using simulated events of

The results demonstrate that CKF seeded by the Hough Transform achieves improved efficiency compared to traditional seeding approaches, particularly for particles with large vertex displacements. Specifically, tracking efficiency using the combined Hough Transform and CKF reaches approximately 80% for protons and antiprotons with above 350 MeV/c, and over 70% for π with pT above 85 MeV/c, with negligible fake track rates. Duplicate tracks are observed mainly for particles with pT below 150 MeV/c, which tend to exhibit looping trajectories.

Future enhancements, such as extending the 2D Hough space to a 3D Hough space – where track projections in the x-y plane not passing through the origin are described using three dedicated parameters – are anticipated to further improve tracking efficiency for long-lived particles at STCF and similar facilities.

The standard model of particle physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, S96-S111 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.71.S96Design and construction of the BESIII detector

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 614, 345-399 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.12.050Super Tau-Charm Facility of China

. PHYSICS 49, 513-524 (2020). https://doi.org/10.7693/wl20200803STCF conceptual design report (Volume 1): Physics & detector

. Frontiers of Physics 19, 14701 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-023-1333-zDesign of bunch length and charge monitor based on cavity resonator for injector of Super Tau-Charm Facility

. NUCLEAR TECHNIQUES 47,. https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2024.hjs.47.100204Status of CP violation in hyperon decays

. Physics Letters B 272, 411-418 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(91)91851-LCP violation from supersymmetry in hyperon decays

. Nuclear Physics A 684, 710-712 (2001). Few-Body Problems in Physics. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)00469-9Polarization and entanglement in baryon–antibaryon pair production in electron–positron annihilation

. Nature Physics 15, 631-634 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0494-8A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems

. Journal of Basic Engineering 82, 35-45 (1960). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3662552Applying the Kalman filter particle method to strange and open charm hadron reconstruction in the STAR experiment

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 158 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01320-1Software Performance of the ATLAS Track Reconstruction for LHC Run 3

. Computing and Software for Big Science 8, 9 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41781-023-00111-yCMS tracking performance in Run 2 and early Run 3. Tech. rep., CERN, Geneva

(2024). arXiv:2312.08017, https://doi.org/10.22323/1.448.0074Track finding at Belle-II

. Computer Physics Communications 259,Simulation and reconstruction of particle trajectories in the CEPC drift chamber

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 35, 128 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01497-zThe Circular Electron Positron Collider

. Nature Reviews Physics 1, 232-234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-019-0047-1Track reconstruction at the first level trigger of the Belle II experiment

. (Low transverse momentum track reconstruction based on the Hough transform for the BESIII drift chamber

. Radiation Detection Technology and Methods 2, 20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-018-0052-4Global track finding based on the Hough transform in the STCF detector

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 1075,A Common Tracking Software Project.

. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41781-021-00078-8FASER experiment: An introduction and research progress

. Chinese Science Bulletin 69, 1025-1033 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1360/TB-2023-1034Implementation of ACTS into sPHENIX track reconstruction

. Computing and Software for Big Science 5,. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24997-7_6Implementation of ACTS for STCF track reconstruction

. Journal of Instrumentation 18,Simulation study of BESIII with stitched CMOS pixel detector using acts

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01353-6Application of ACTS for gaseous tracking detectors

. Modern Physics Letters A 39,Fabrication and performance of a μRWELL detector with Diamond-Like Carbon resistive electrode and two-dimensional readout

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 927, 31-36 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2019.01.036Study of hybrid micropattern gaseous detector with CsI photocathode for Super Tau-Charm facility RICH

. Journal of Instrumentation 18,Imaging-based likelihood analysis for the STCF DTOF detector

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 1049,A light yield enhancement method using wavelength shifter for the STCF EMC

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 1050,Design and development of the core software for STCF offline data processing

. Journal of Instrumentation 18,Design and development of STCF offline software

. Modern Physics Letters A 39,Coherent exclusive exponentiation for precision Monte Carlo calculations

. Phys. Rev. D 63,Event generators at BESIII

. Chinese Physics C 32, 599 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/32/8/001DD4hep: A Detector Description Toolkit for High Energy Physics Experiments

. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 513,Extensible markup language

. World Wide Web Journal 2, 29-66 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4302-0187-8_6Geant4—a simulation toolkit

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 506, 250-303 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8The ROOT geometry package

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 502, 676-680 (2003). Proceedings of the VIII International Workshop on Advanced Computing and Analysis Techniques in Physics Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)00541-2ROOT — An object oriented data analysis framework

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 389, 81-86 (1997). New Computing Techniques in Physics Research V. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(97)00048-XFast circle fit with the conformal mapping method

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 270, 498-501 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(88)90722-XTrack reconstruction using the TSF method for the BESIII main drift chamber

. Chinese Physics C 32, 565-571 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/32/7/011The authors declare that they have no competing interests.