Introduction

To tackle the global energy crisis and mitigate environmental pollution, advancements in clean energy technologies have driven continuous progress in the global nuclear power industry [1]. However, the operation of nuclear power plants and the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel generate substantial amounts of radioactive liquid waste. These wastes contain not only fissile materials such as uranium and plutonium but also significant quantities of fission products such as cesium, strontium, palladium, and technetium, which remain highly radioactive [2, 3]. Ensuring the safe and effective treatment and disposal of these liquid wastes is critical for environmental protection and makes the separation and recovery of radioactive nuclides a pressing global challenge [4].Cesium-137 is particularly concerning owing to its high radioactivity, significant heat generation, and long half-life [5, 6]. Its chemical properties are similar to those of sodium and potassium, and it mainly exists as cesium ions in aqueous solutions. Cesium exhibits high mobility and bioaccumulation, which enables it to easily enter various environments and eventually accumulate in human bones and muscle tissues [7]. This bioaccumulation can lead to inflammatory diseases and cancers in various organs and cause irreversible damage. Cesium-137 recovered from radioactive waste liquids can serve as a gamma radiation source for medical applications [8]. Therefore, it is crucial to remove cesium-137 from radioactive wastewater efficiently and rapidly to enable subsequent treatment, minimize environmental and societal harm, and ultimately benefit humanity.

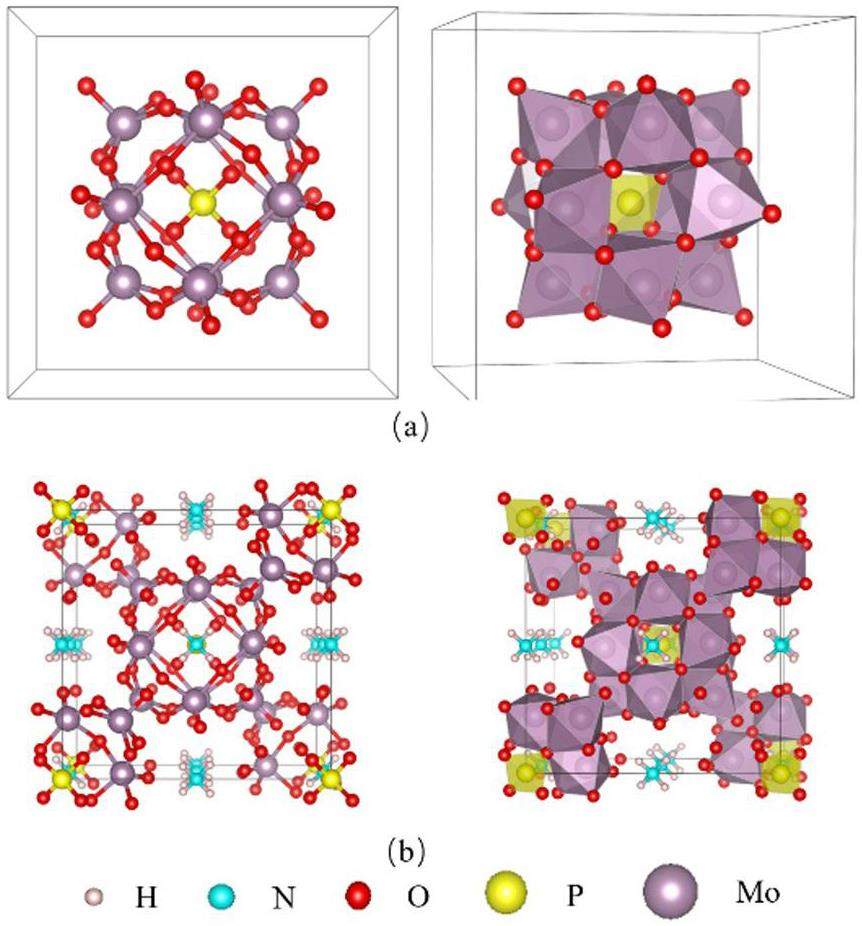

Over the past few decades, various techniques have been developed for the separation of cesium, including chemical precipitation [9], solvent extraction [10-13], and ion exchange [14-17]. While the precipitation method is well-established, it faces practical challenges, such as difficulties in solid–liquid separation in high-radiation environments. Solvent extraction is currently the most widely used method in the industry; however, it carries risks of radiation-induced degradation of solvents and diluents. This degradation can cause severe equipment corrosion and generate substantial amounts of secondary liquid waste. Ion exchange is an effective partitioning technology owing to its high selectivity, large adsorption capacity, simplicity of equipment, and low cost. Various ion exchangers have been studied, including zeolites [18], heteropoly acids [19, 20], ferrocyanides [21], Prussian blue analogs [22], titanium silicates [23], metal sulfides [24], metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [25], and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) [26]. Among these, ammonium phosphomolybdate (AMP), an inorganic ion exchanger with a Keggin structure composed of

Studies have demonstrated that synthesizing micro-nano-scale materials or incorporating metal ions into hybrid materials can significantly enhance their mechanical and adsorption properties [29]. Chattopadhyay et al. developed micronano zirconium phosphate, which improved both the mechanical properties and cesium separation efficiency in 137Cs–137mBa mixtures [30-32]. Taher Yousefi et al. incorporated cerium into phosphomolybdate, which resulted in higher distribution coefficients for ions such as Tl+, Pb2+, Th4+,

Chemical co-precipitation is a simple and cost-effective method for efficiently producing large quantities of micro-nano materials. In this study, we synthesized micro-nano-scale metal-hybridized AMP via the chemical co-precipitation technique. During synthesis, various concentrations of

Current research on AMP mainly focuses on modifications involving its loading onto various substrates, such as silica or alginate beads. However, this approach may reduce the adsorption capacity of the material due to challenges such as limited loading efficiency. The objective of this study is to directly hybridize multivalent Sn ions into AMP via a chemical co-precipitation method. This approach aims to modify the microstructure of AMP by increasing the charge density per unit volume, which preserves its high adsorption capacity while enhancing its overall adsorption performance. The study involves microscopic characterization and adsorption behavior analysis of the synthesized materials to confirm the successful preparation of Sn-doped AMP and identify the optimal material for further investigation. Additionally, we aim to analyze the fundamental factors contributing to the enhanced performance of the Sn-doped AMP series through experimental characterization and density functional theory (DFT) simulations. These simulations will model changes in energy structures during synthesis and adsorption processes and provide insight into the adsorption mechanism of cesium by Sn-doped AMP.

Experimental

Materials

The chemical reagents used in this study included phosphomolybdic acid (H3[P(Mo3O10)4]), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), tin dichloride (SnCl2), ferric chloride (FeCl3), tin tetrachloride (SnCl4), cesium nitrate (CsNO3), strontium nitrate (Sr(NO3)2), samarium trinitrate (Sm(NO3)3), lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO3)36H2O), gadolinium nitrate hexahydrate (Gd(NO3)36H2O), cerium nitrate (Ce(NO3)4), europium nitrate(Eu(NO3)3), dysprosium nitrate hexahydrate (Dy(NO3)36H2O), holmium nitrate pentahydrate (Ho(NO3)35H2O), thulium nitrate pentahydrate (Tm(NO3)35H2O), ytterbium nitrate (Yb(NO3)3), lutetium nitrate pentahydrate (Lu(NO3)35H2O), potassium niobate (KNbO3) and nitric acid (HNO3). These reagents were procured from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. All of the reagents had a purity of greater than 99.5%, except for SnCl4 (98%) and HNO3 (65.0%–68.0%).

Preparation of the Adsorbent

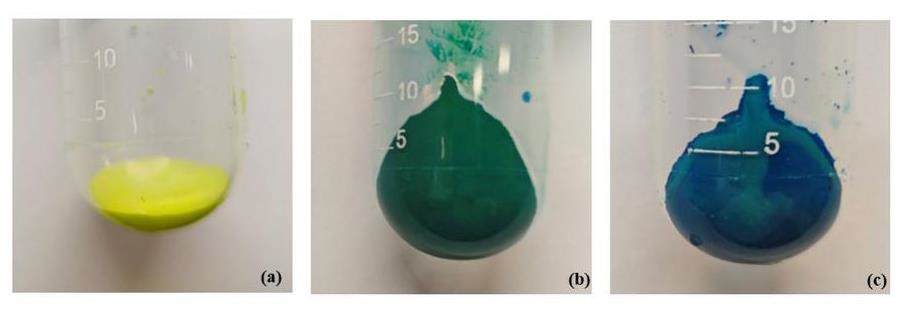

The SnIIxSnIVy(NH4)3-x-y[P(Mo3O10)4] was synthesized via a chemical co-precipitation method, which involved the gradual addition of a hybrid solution containing various components into a soluble solution to ensure uniform mixing and controlled precipitation [40]. First, 100 mL of a 0.05 mol/L phosphomolybdic acid solution was prepared in a beaker. A magnetic stirrer was placed in the beaker, and the solution was stirred at 500 rpm. Appropriate amounts of SnCl4, FeCl3, and SnCl2 hybrid element solutions were then added dropwise to the phosphomolybdic acid solution while maintaining stirring for 30 min. This ensured a complete reaction between the hybrid elements and phosphomolybdic acid. Finally, an adequate amount of NH4Cl solution was added to enhance the crystallization performance of the material. The solid–liquid mixture was allowed to stand and age for 24 h to facilitate the full development of the microcrystals of the hybrid material. After aging, the mixture was separated using a water aspirator and a Buchner funnel to remove any undeveloped or damaged particles. The material was then washed with deionized water and centrifuged to remove insoluble impurities. Finally, the centrifuged material was dried in a constant-temperature vacuum oven. The resulting adsorbent materials contained various hybrid elements and different hybrid contents. Specific data for each formulation are presented in Table 1 and undried samples are shown in Fig. 2 (In this study, x and y represent the number of ammonium ions replaced in each AMP).

| SnIIxSnIVy (NH4)3-x-y[P(Mo3O10)4] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample NO. | x | y | Whether to add Fe |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | No |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | No |

| 3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | No |

| 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | Yes |

| 5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | Yes |

| 6 | 0.15 | 0.15 | Yes |

| 7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | Yes |

| 8 | 0.4 | 0 | No |

| 9 | 0 | 0.4 | No |

| 10 | 0.2 | 0.2 | No |

Characterization

The surface morphology was examined using a scanning electron microscope (HITACHI, SU 8600, Japan) and a transmission electron microscope (JEOL, JEM-2100F, Japan). The composition and content of the adsorbent before and after adsorption were analyzed using an energy-dispersive spectroscope (FEI, NOVA NanoSEM 230, America). The unit cell size of the adsorbent was determined using a multifunctional X-ray diffractometer (BRUKER-AXS, D8 ADVANCE Da Vinci, German). The functional groups of the adsorbent were characterized using a Fourier transform infrared spectroscope (THERMO FISHER, Nicolet 6700, America). The thermal decomposition of the adsorbent was evaluated using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Perkin Elmer, TGA8000, America). The valence states and proportions of the main elements were investigated using an X-ray photoelectron spectroscope (AXIS Ultra DLD, Shimadzu, Japan).

Adsorption Experiments

Batch experiments were conducted to investigate the adsorption capacity and characteristics of the synthesized adsorbents for metal ions. First, the adsorption capacity for Cs and the stability of various materials were examined. The optimal hybrid material was then selected for studying the multi-ion adsorption selectivity. Additionally, the changes in isotherm models at different temperatures for this material were analyzed. Finally, the kinetics of various adsorbents were studied to assess the impact of hybridization on their adsorption rates. A specified amount of adsorbent was added to a glass bottle, followed by the experimental solution (with varying metal ion compositions and concentrations). The bottle was sealed and placed in a pre-set temperature-controlled shaking bath for oscillation. After ensuring complete adsorption (except for kinetic tests), the bottle was removed. The mixture was then filtered to separate the solid from the liquid, and the concentration of target radionuclides in the solution was measured. Unless otherwise specified, the experimental conditions were: V/m=100 cm3/g, T=25 ℃, pH=7. The concentrations of Cs and other metal ions were measured using an atomic absorption spectroscopy (Shimadzu, AA-660, Japan) and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscope (Shimadzu, ICPS-7510, Japan).

DFT Calculations

DFT is a powerful tool for accurately calculating and predicting the electronic properties of crystal structures. DFT avoids the need to solve complex multibody Schrödinger equations by assuming that the energy of the system can be expressed as a function of electron density, which significantly reduces computational load and saves time. In this study, DFT was employed to analyze the adsorption process and mechanism of the hybrid adsorbent for Cs. All of the calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio simulation package (VASP 6.2) with plane-wave spin-polarized periodic DFT methods. The projector augmented wave method was used to describe electron–ion interactions and electron exchange and correlation energies were treated using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation function. A cutoff energy of 500 eV, was applied, and the gamma grid was used for Brillouin zone sampling. First, the AMP model was optimized [42], with a force convergence threshold set to less than 0.05 eV/Å. Subsequently, the single-point energies of the system were calculated, with total energy convergence set to less than 10-6 eV.

Results and discussion

SEM TEM and EDS

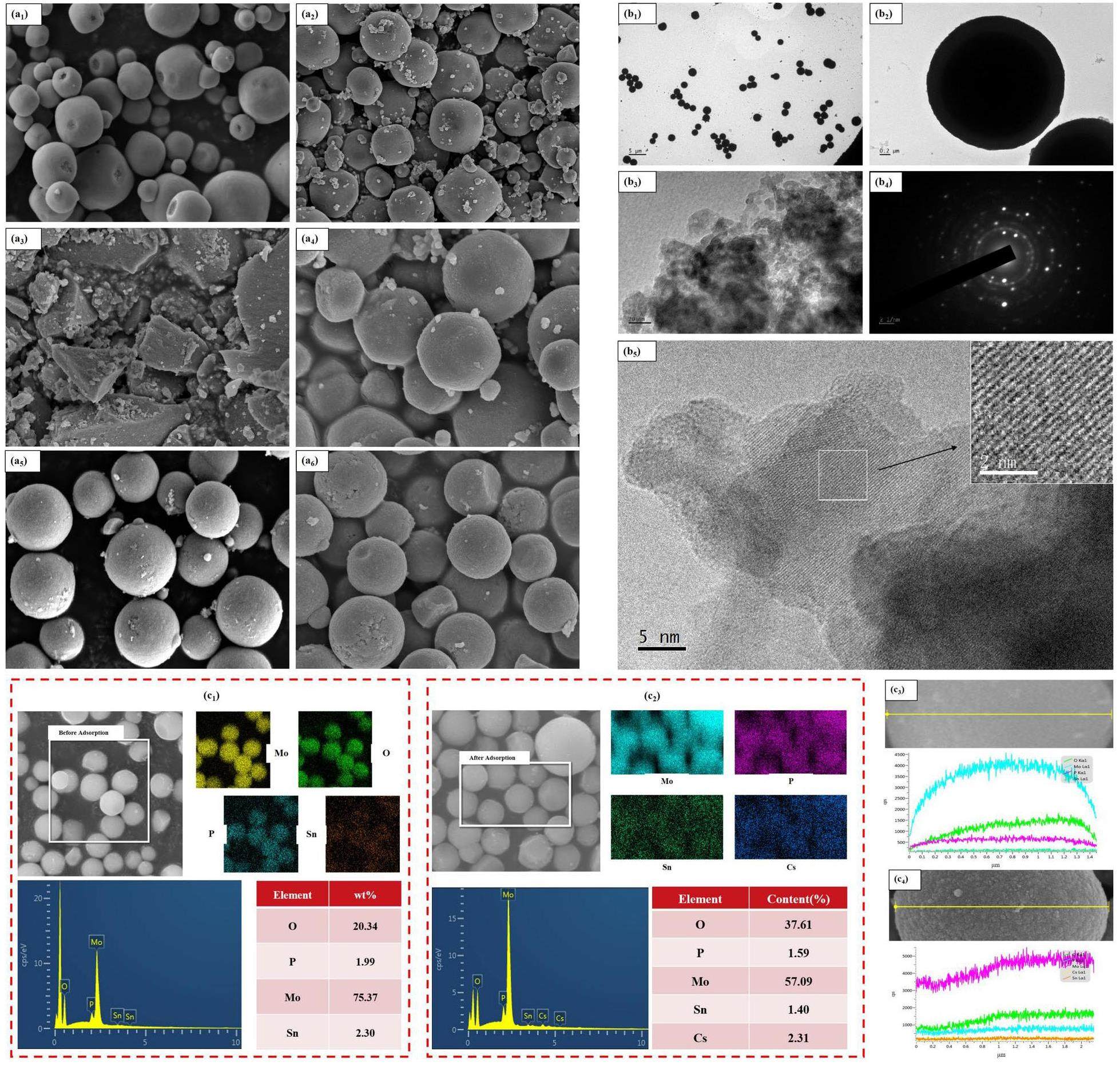

The microstructure of AMP and the SnIIxSnIVy(NH4)3-x-y[P(Mo3O10)4] series was initially examined via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). According to the SEM results, the synthesized AMP predominantly exhibited a cubic structure (Fig. 3a1), with most particles displaying surface defects that impair the mechanical properties of the material. After hybridizing with Sn(IV) alone (Fig. 3a2), the increase in unit volume charge was smaller, and owing to the absence of Fe, complete particles did not form because of the lack of copolymerization effects. Therefore, further investigation of this material will not be pursued. When Sn(IV) and Sn(II) were added simultaneously but without Fe (Fig. 3a3), due to a smaller increase in unit volume charge and the absence of Fe, no complete particles were formed due to the lack of copolymerization effects. Subsequent experiments will not involve further investigation of this material. With the simultaneous addition of Sn(IV) and Sn(II) but without Fe (Fig. 3a4), the material exhibited reduced defects, and the microscopic particles transitioned from a cubic to a spherical structure under the high unit volume charge. Finally, when Fe was added alongside Sn(IV) and Sn(II) (SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] with Fe) (Fig. 3a5), the copolymerization effect between Sn(II) and Fe(III) enhanced the crystallinity of the material, which resulted in well-formed spherical particles with intact surfaces and significantly improved mechanical properties. After adsorption of cesium ions, the microscopic spheres of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] with Fe (Fig. 3a6) showed no significant changes, which indicated that the material retained its stable fundamental structure throughout the adsorption process.

Further, the SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) hybrid material, which featured spherical microparticles, was further analyzed via a transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The TEM images reveal distinct lattice fringes with no noticeable disruptions or displacements, and the consistent spacing between parallel fringes confirms a typical face-centered cubic unit cell structure. The lattice spacing within the unit cell was uniformly distributed. The lattice spacing of the sample was determined to be 2.55 Å by measuring and averaging the spacing between multiple sets of parallel fringes (Fig. 3b5). Figure 3b4 sdisplays uniform reflection rings produced by the numerous brightened nanoscale grains of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe), as observed through selected area electron diffraction.

Electron dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was conducted on SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) to examine the elemental composition and proportions before and after adsorption. Surface scanning results (Figure 3c1 and c2) confirmed the presence of Sn both before and after adsorption, while Cs is detected only post-adsorption. These findings suggested that Sn was successfully hybridized into AMP and that the hybridized adsorbent retained its Cs adsorption capacity. In addition, there was no significant change in the Sn content or energy relative to Mo, which indicated that Sn does not directly react with Cs. Line scan results (Fig. 3c3 and c4) revealed a good overlap of characteristic peaks for Sn and Cs after adsorption and demonstrated that both elements coexisted in a similar form within the material and that a substitution reaction with ammonium ions occurred [43].

The Sn-doped-AMP

To identify the optimal hybrid adsorbent, a series of microstructural characterizations and batch adsorption experiments were performed on the Sn-doped AMP.

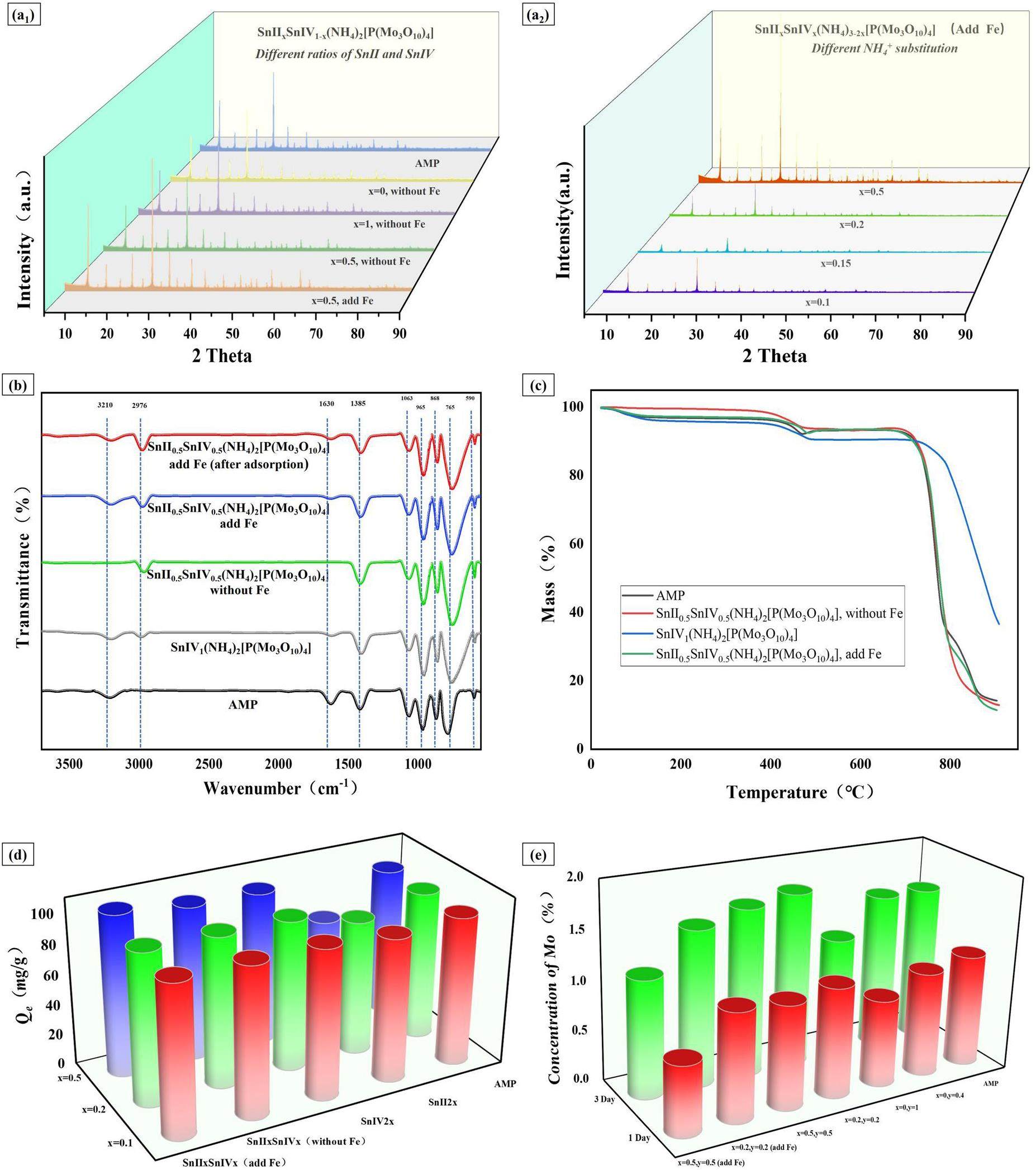

The crystalline structure of AMP and Sn-doped AMP was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD). The relative intensity and distinct peaks confirmed the good crystallinity of the products (Fig. 4a1). For the Sn-doped AMP, the diffraction peaks shifted to the right compared with those of AMP in the order of Sn(II) >Sn(II) + Sn(IV) > Sn(IV). This shift indicated a reduction in lattice constants, which was attributed to the smaller ionic radii of the hybrid elements compared with ammonium ions (ionic radii:

Furthermore, the effect of various hybrid concentrations ((

According to the Scherrer equation, the AMP samples exhibited an average particle size of 73.5 nm, while the hybridized samples showed a reduced average particle size ranging from 55 nm to 65 nm. This indicates a noticeable decrease in particle size due to hybridization.

Second, Figure 4b shows the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis results for AMP and the Sn-doped-AMP samples. Both AMP and Sn-doped-AMP exhibited characteristic peaks at 1063 cm-1 (O=P-OH groups), 965 cm-1 (Mo-O absorption), 868 cm-1 (Mo-O-Mo absorption), and 765 cm-1 (antisymmetric stretching vibration of

Third, Fig. 4c and Table 2 present the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) results for AMP and the Sn-doped-AMP, which showed that all four materials underwent three stages of decomposition. The first stage involved weight loss due to the release of crystalline water from the material. The second stage corresponded to the decomposition of ammonium ions into NH3 gas. In this stage, AMP exhibited a weight loss of 2.58%, while the Sn-doped-AMP showed a weight loss of approximately 1.6%, which aligned with theoretical values of 2.79% and 1.76%, respectively. The final weight loss stage resulted from the decomposition of phosphomolybdic acid into phosphorus and molybdenum compounds, leading to the destruction of the Keggin structure and loss of cesium adsorption capability [45]. Despite the similar pyrolysis processes, the thermal stability of the materials improved following hybridization. Notably, the SnII1(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] sample began releasing ammonia only at 765 ℃, whereas AMP initiated ammonia release at 710 ℃. The improved thermal stability is attributed to the enhanced interaction forces between the internal components of the molecules after hybridization, resulting in a significant increase in pyrolysis temperature compared to other materials.

| Sample | Pyrolysis stage | Temperature (°C) | Mass loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | The release of crystalline water | 25–465 | 8.78 |

| The decomposition of ammonium ions | 465–710 | 2.58 | |

| The decomposition of phosphomolybdic acid | 710–930 | > 77 | |

| SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (without Fe) | The release of crystalline water | 25–465 | 8.78 |

| The decomposition of ammonium ions | 465–710 | 2.58 | |

| The decomposition of phosphomolybdic acid | 710–930 | > 77 | |

| SnIV1(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] | The release of crystalline water | 25–465 | 8.78 |

| The decomposition of ammonium ions | 465–710 | 2.58 | |

| The decomposition of phosphomolybdic acid | 710–930 | > 77 | |

| SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) | The release of crystalline water | 25–465 | 8.78 |

| The decomposition of ammonium ions | 465–710 | 2.58 | |

| The decomposition of phosphomolybdic acid | 710–930 | > 77 |

Fourth, a comparison of the adsorption capacities of various adsorbents was conducted. Adsorption capacity experiments involved using 50 mg of each hybridized material with a 1200 ppm Cs aqueous solution (Fig. 4d). the main components of the samples from various hybrid formulations still showed a high degree of similarity to AMP, which resulted in adsorption capacities comparable to those of AMP. However, the adsorption capacity of all materials increased with the doping amount, except for those hybridized with Sn(II) alone. Linking this with the SEM results, it can be inferred that the increase in adsorption capacity is due to the transition of the material’s microstructure from cubes to polyhedra and eventually to spheres, which led to an increase in the specific surface area. Compared with AMP, the SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) exhibited the highest adsorption capacity of 106.8 mg/g, which represented an increase of approximately 10%. In contrast, the decreased adsorption capacity of the Sn(II)-doped AMP could be attributed to the presence of Sn(II) alone, which lacked the high charge of Sn(IV) to enhance material performance. Additionally, it did not form a stable crystal configuration through copolymerization with Fe(III).

Finally, stability is a crucial factor for the practical use of materials. To assess this, chemical stability experiments were conducted on several hybrid materials with good adsorption capacities by immersing the materials in distilled water and measuring the Mo leaching rate at various time intervals.(SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe))demonstrated excellent stability, with Mo leaching rates of 0.69% and 1.18% after 1 and 3 days, respectively (Fig. 4e). These values were significantly lower than those of AMP, which indicated that the copolymerization effect of

According to the experimental results, the SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe), which retained the effective Keggin structure and exhibited good thermal stability, demonstrated the highest adsorption capacity and excellent chemical stability among the various Sn-doped-AMP materials. Therefore, it was selected as the hybrid material for subsequent in-depth research.

The SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) hybridized material

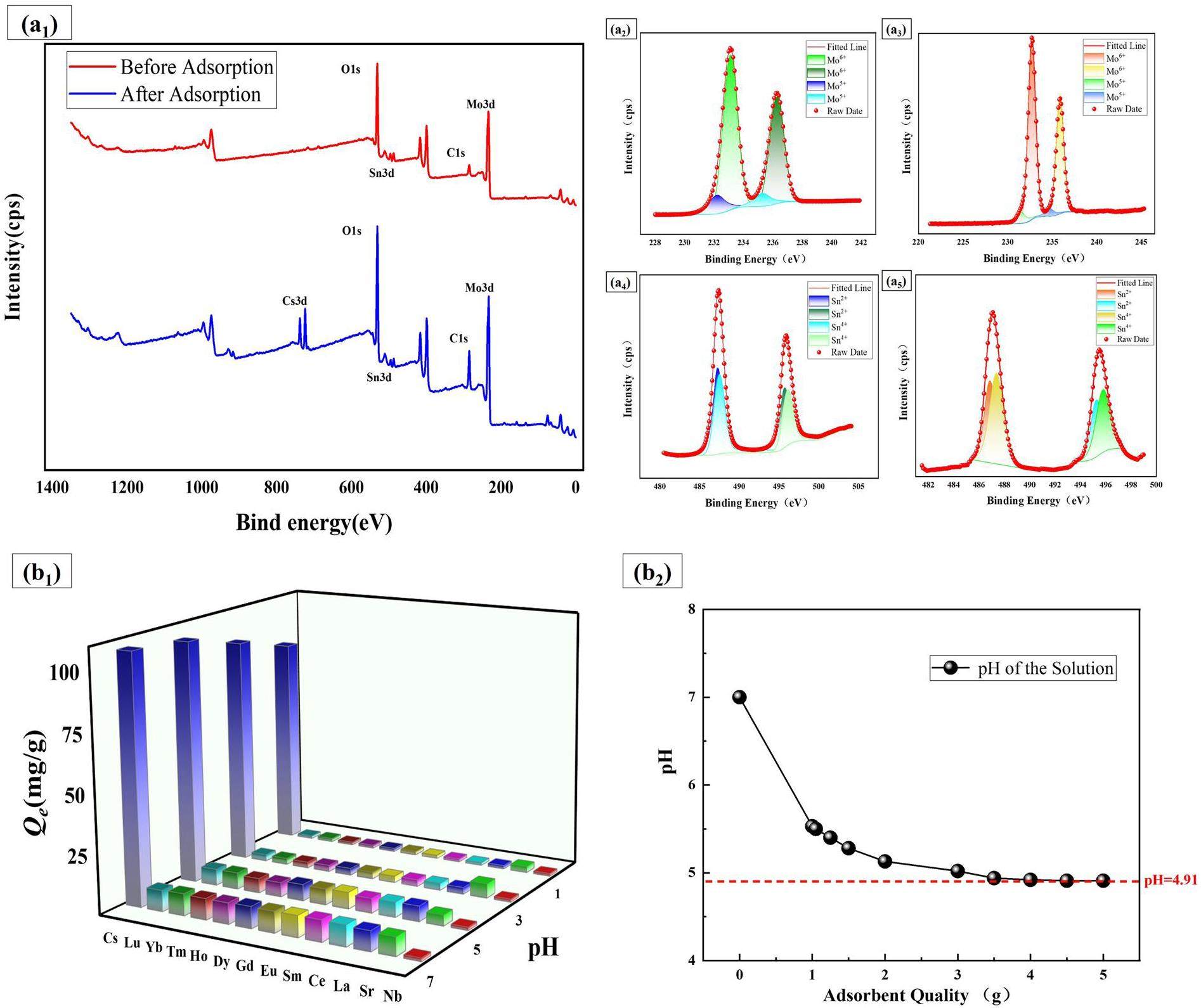

First, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted to investigate the adsorption mechanism of Cs on SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe). Figure 5a1 shows the full spectrum of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) before and after Cs adsorption. Distinct Cs 3d peaks were observed, which confirmed the successful adsorption of Cs onto the hybrid material. Additionally, no Fe-related peaks were detected in the full spectra before or after adsorption. This absence was attributed to the small ionic radius of Fe(III), which might prevent it from forming stable products with the Keggin structure of AMP. Further peak deconvolution of the main elements revealed no significant changes in their binding energies.

Figures 5a2 and a3 display the high-resolution Mo 3d spectra. Before adsorption, the binding energies for Mo were 233.11 eV, 236.26 eV (Mo6+, as well as 232.19 and 235.27 eV (Mo5+), with corresponding proportions of 51.17%, 35.30% (Mo6+) and 8.00%, 5.52% (Mo5+), respectively. After adsorption, the binding energies shifted to 232.72 eV, 235.87 eV (Mo6+) and 231.53 eV, 234.76 eV (Mo5+), with proportions of 53.27%, 36.72% (Mo6+) and 5.93%, 4.09% (Mo5+), respectively. The binding energies and peak area proportions for the various valence states of Mo showed no significant changes, which indicated that no redox reactions involving Mo occurred during the adsorption process.

Figures 5a4 and a5 present the high-resolution Sn 3d spectra. Before adsorption, the binding energies for Sn were 487.25 eV and 495.66 eV (Sn2+) and 487.49 eV, 496.10 eV (Sn4+), with proportions of 28.23%, 19.55% (Sn2+) and 31.33%, 20.89% (Sn4+), respectively. After adsorption, the binding energies shifted to 486.85 eV, 495.25 eV (Sn2+) and 487.39 eV, 495.79 eV (Sn4+), with proportions of 23.77%, 16.46% (Sn2+) and 35.69%, 24.08% (Sn4+), respectively. Similar to the Mo results, the binding energies and peak area proportions of the various valence states of Sn showed no significant changes, which confirmed the absence of redox reactions involving Sn during the adsorption process. Combined with the IR spectroscopy results, it can be concluded that the adsorption mechanism of Cs on the SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) mainly involved an ion-exchange reaction.

Second, radioactive wastewater contained various metal ions, which often interfered with each other during industrial processes, leading to a reduced adsorption capacity of the adsorbent for target radionuclides [46]. Therefore, it is essential to assess the adsorption selectivity of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe). SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) was introduced to mixed ion solutions at different pH values and adsorption capacity curves for various ions were plotted (Fig. 5b1). In mixed ion solutions at different pH values, SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) demonstrated a high adsorption capacity for Cs, with almost no adsorption of other metal elements in the solution (e.g., Sr, Eu). This result indicated that SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) retained good adsorption selectivity for cesium under various conditions. Additionally, as the pH decreased, the adsorption capacity of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) decreased, mainly owing to the competition between H+ and Cs+ during the adsorption process. The point of zero charge (PZC) pH value of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) was measured via the mass titration method [47]. As shown in the Figure 5b2, the PZC ofSnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) is 4.91. When the solution pH was lower than 4.91, a large amount of H+ ions accumulated on the surface of the adsorbent. The high concentrations of H+ ions could electrostatically interact with metal cations and reduce the adsorption capacity of the material [48, 49].

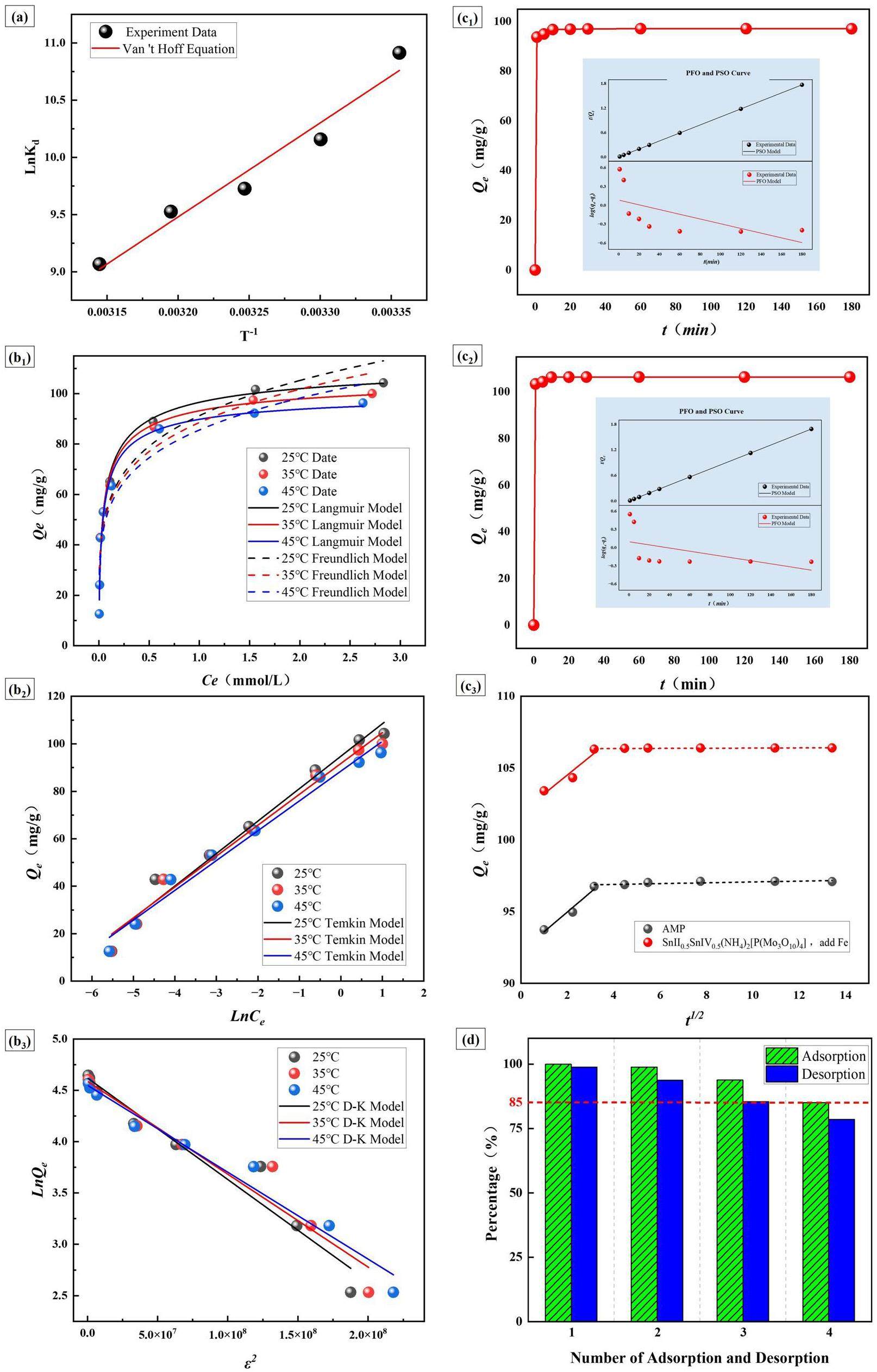

Third, to evaluate the effect of temperature on the adsorption process, the thermodynamic parameters of the adsorption reaction were calculated using the Van’t Hoff equation:

| Temperature (K) | ΔH (KJ/mol) | ΔS (KJ/mol · K) | TΔS (KJ/mol) | ΔG (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | -68.39 | -0.14 | -41.72 | -26.67 |

| 303 | -42.42 | -25.97 | ||

| 308 | -43.12 | -25.27 | ||

| 313 | -43.82 | -24.57 | ||

| 318 | -44.52 | -23.87 |

From the table, it can be observed that the ΔH value is negative, which indicated that the reaction is exothermic. The negative ΔS value suggests that the driving force of the reaction decreased with increasing temperature, which means the Kd value decreased as temperature rose [50]. Additionally, calculations revealed that the ΔG values for the adsorption reaction remain negative up to 215.48 ℃.

Fourth, the adsorption isotherms illustrated the relationship between the amount of adsorbate adsorbed by the adsorbent at equilibrium and the concentration of the target radionuclide in the solution. These isotherms can be used to identify specific adsorption mechanisms and calculate the saturated adsorption capacity of the adsorbent.

The Langmuir model assumes that the adsorption reaction is a monolayer adsorption process with constant adsorption energy. The fitting equation is:

The Freundlich model assumes that the adsorption occurs on a heterogeneous adsorbent surface with multiple layers of adsorption. The fitting formula is:

The Temkin model accounts for adsorbate-adsorbate interactions and assumes that the adsorption energy decreases linearly as the surface coverage increases. The fitting formula is:

The Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) model assumes that the adsorption process follows a porous filling mechanism with a Gaussian distribution of adsorption energies. The fitting equation is:

The nonlinear Langmuir and Freundlich fitting results for the hybrid materials at different temperatures are shown in Fig. 6b1, with the estimated isotherm parameters listed in Table 4. For all temperature conditions, the Langmuir model consistently provided better fits, with correlation coefficients (

| Experimental temperature | Isotherm model | Estimated isotherm parameters | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (H2O, pH=7) | |||

| 25 ℃ | Langmuir | Qm | 115.00 |

| KL | 5.25 | ||

| R2 | 0.9777 | ||

| Freundlich | KF | 91.27 | |

| 1/n | 0.21 | ||

| R2 | 0.9240 | ||

| Temkin | bT | 184.21 | |

| KT | 1152.64 | ||

| R2 | 0.9793 | ||

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | K | 29.71 | |

| E | 1297.50 | ||

| R2 | 0.9477 | ||

| Experimental data | Qm | 106.77 | |

| 35 ℃ | Langmuir | Qm | 108.78 |

| KL | 6.00 | ||

| R2 | 0.9751 | ||

| Freundlich | KF | 88.56 | |

| 1/n | 0.20 | ||

| R2 | 0.9180 | ||

| Temkin | bT | 196.83 | |

| KT | 1156.36 | ||

| R2 | 0.9749 | ||

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | K | 27.46 | |

| E | 1350.86 | ||

| R2 | 0.9441 | ||

| Experimental data | Qm | 100.06 | |

| 45 ℃ | Langmuir | Qm | 102.06 |

| KL | 7.34 | ||

| R2 | 0.9860 | ||

| Freundlich | KF | 85.59 | |

| 1/n | 0.20 | ||

| R2 | 0.9199 | ||

| Temkin | bT | 210.67 | |

| KT | 1157.69 | ||

| R2 | 0.9823 | ||

| Dubinin-Radushkevich | K | 23.23 | |

| E | 1468.05 | ||

| R2 | 0.9731 | ||

| Experimental data | Qm | 96.32 | |

However, in some cases, the best-fit model for adsorption materials cannot be determined solely by

In the Temkin model(Fig. 6b2), the correlation coefficient (

Fifth, the surface characteristics of the adsorbent directly influenced the adsorption rate, mainly due to the significant effect of diffusion resistance on ion transport during the adsorption process.

To describe the change in adsorption of the target nuclide over time, we selected the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) kinetic models, which corresponded to physical and chemical adsorption, respectively.

The PFO kinetic model was based on membrane diffusion theory and a physical adsorption model. The expressions for the nonlinear and linear PFO kinetic models are as follows:

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model is based on the membrane diffusion theory and a physical adsorption model. The expressions for the nonlinear and linear pseudo-first-order kinetic models include the following:

The PSO kinetic model represents a chemical adsorption process, where electrons are shared or transferred between the adsorbate and the adsorbent. The expressions for the two forms of the PSO kinetic model are as follows:

Figure 6c1, c2 show the adsorption rates of AMP and SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe), along with the fitted curves for the PFO and PSO models. As observed from the figure, the adsorption of AMP and SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) achieved uptake ratios of over 96% within 1 minute and reached equilibrium quickly. This indicates that, after hybridization, SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) retains the extremely high adsorption rate of AMP while improving its adsorption capacity. Table 5 presents the parameters of the fitted curves for AMP and the SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe). Both materials were best described by the PSO kinetic model, with correlation coefficients greater than 0.99. This suggested that the adsorption process of the hybrid materials was chemical in nature, which aligned with the XPS measurement results. Additionally, the PSO kinetic parameters of the hybrid materials were similar to those of AMP, which indicated that hybridization did not alter the kinetic properties of the material, which still retained a high adsorption rate. According to the fitting results, the equilibrium adsorption capacities of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) under these conditions were in close agreement with the experimentally measured values, which confirmed the accuracy of the model.

| Sample | Kinetic models | Estimated kinetic parameters | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (25 ℃ H2O 1500 ppm Cs) | |||

| AMP | PFO Model | k1 | 0.0086 |

| qe | 1.21 | ||

| R2 | 0.3876 | ||

| PSO model | k2 | 0.21 | |

| qe | 96.63 | ||

| R2 | 0.9999 | ||

| IPD model Stage 1 | kI | 1.37 | |

| C | 92.23 | ||

| R2 | 0.9647 | ||

| IPD model Stage 2 | kI | 0.029 | |

| C | 96.73 | ||

| R2 | 0.9743 | ||

| Experimental data | qm | 97.21 | |

| SnII0.5 |

PFO Model | k1 | 0.0061 |

| qe | 1.25 | ||

| R2 | 0.2599 | ||

| PSO model | k2 | 0.31 | |

| qe | 106.38 | ||

| R2 | 0.9999 | ||

| IPD model Stage 1 | kI | 1.31 | |

| C | 101.91 | ||

| R2 | 0.9568 | ||

| IPD model Stage 2 | kI | 0.0057 | |

| C | 106.35 | ||

| R2 | 0.9372 | ||

| Experimental data | qm | 106.82 | |

Furthermore, this study also investigated particle diffusion during the adsorption process of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) using the intraparticle diffusion model (IPD). The equation for the intraparticle diffusion model is as follows:

As shown in Fig. 6c3, the adsorption processes of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) and AMP for Cs can be mainly divided into two stages. The first stage is the relatively steep surface diffusion stage, during which Cs is rapidly adsorbed onto the surface of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe). However, it is noteworthy that the curve does not pass through the origin, indicating that internal diffusion is not the sole factor controlling the adsorption process [55]. The second stage is the more gradual internal diffusion stage, where, due to the occupation of a large number of adsorption sites on the surface and within the pores of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe), the adsorption process transitions to diffusion within the particles, resulting in a significant decrease in the adsorption rate and ultimately reaching equilibrium [56, 57].

Finally, desorption performance and reusability were crucial parameters for evaluating the effectiveness of adsorbents. In this experiment, a 500 ppm Cs solution was used for adsorption, and 3M NH4Cl was employed as the desorbent. The adsorption-desorption experiments were conducted at pH 7. After each adsorption, the adsorbent was immersed in 3M NH4Cl for desorption, followed by a new adsorption cycle. This process was repeated for a total of four cycles. As shown in Fig. 6d, the desorption rate did not reach 100% after each cycle, leading to a gradual decline in the adsorption efficiency of SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe). However, both the desorption rate in the third cycle and the adsorption rate in the fourth cycle remained above 85%, which indicated that SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) exhibited good reusability and could meet the demands of practical industrial applications.

DFT analysis

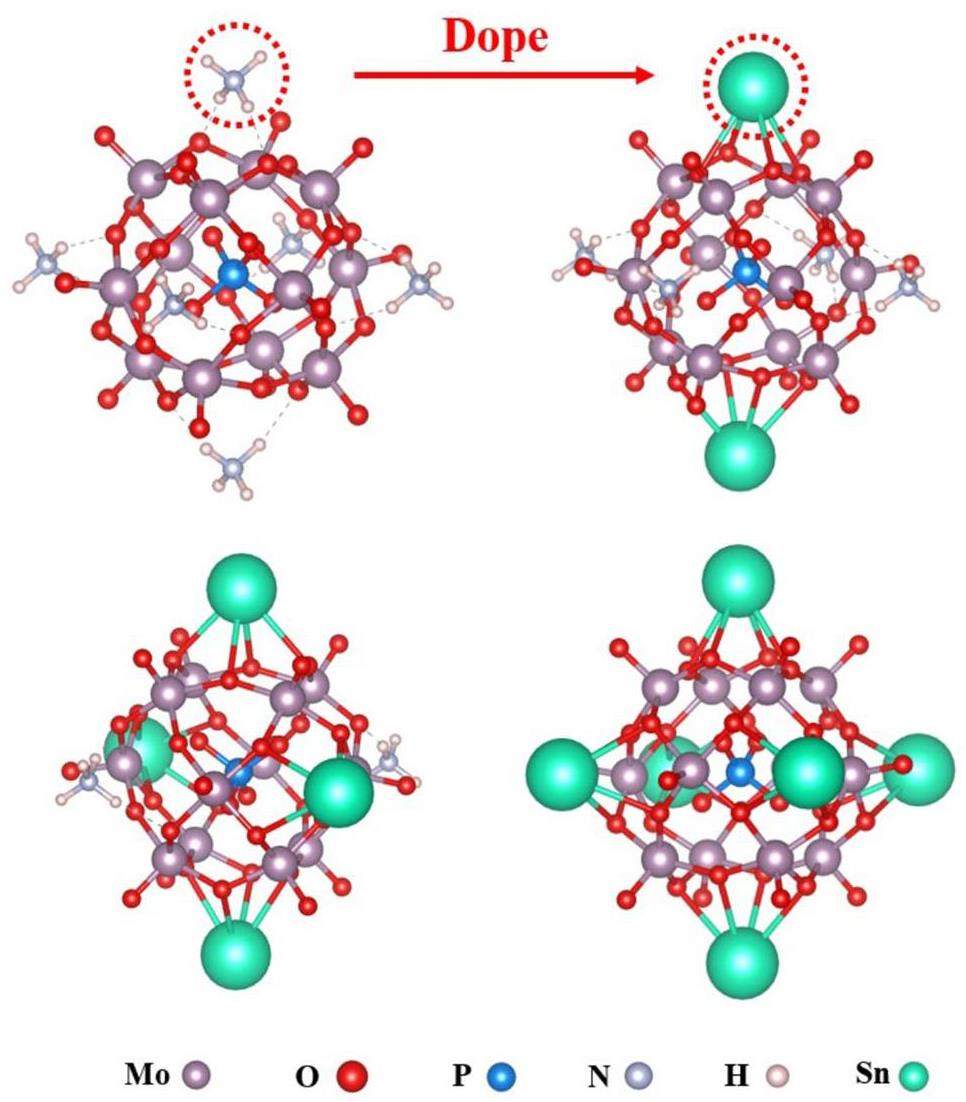

DFT simulations were performed to model the molecular structure of the synthesized hybrid materials and calculate their energy changes. First, the adsorption process was simulated by systematically replacing ammonium ion sites in AMP with other ions. When Fe atoms were introduced as substitutes, the model results failed to converge, which indicated that Fe could not directly react with AMP. This finding aligned with the microscopic characterization results obtained from EDS and XPS. A series of initial model structures for the hybrid materials were obtained by substituting ammonium ions with Sn atoms (Fig. 7). Table 6 lists the crystal structural parameters of AMP and SnIIxSnIVy(NH4)3-x-y[P(Mo3O10)4] after optimization. Calculations were performed to determine the cell parameters of each material, energy changes during synthesis, and energy changes during the adsorption process. Static calculations were conducted on energy changes to obtain the total free energy changes for each system. The energy calculation formula is as follows:

| Kind | Number of Sn | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | V (Å3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMP | 0 | 10.93 | 10.93 | 10.99 | 1313.19 |

| AMP-Sn1 | 1 | 11.03 | 10.08 | 11.07 | 1230.66 |

| AMP-Sn2 | 2 | 10.09 | 10.09 | 11.00 | 1120.05 |

| AMP-Sn3 | 3 | 10.22 | 10.22 | 10.22 | 1068.03 |

According to the DFT calculation results, when Sn ions replaced ammonium ions, the cell size of the crystals decreased, with the simulation results aligning with experimental findings. Additionally, based on the energy calculation results in Table 7, the substitution of Sn was a spontaneous exothermic reaction. The binding energy was lowest when only one Sn ion was substituted, which indicated that this configuration was the most stable. However, during subsequent adsorption processes, if two ammonium ions were replaced by Sn ions during synthesis, the reaction became endothermic and could not proceed spontaneously. Therefore, it was crucial to strictly control the Sn concentration and the drop rate of the solution during the synthesis of hybrid materials to ensure optimal hybridization conditions. According to previous research conducted by our group, two-thirds of the active ammonium ions in AMP underwent ion exchange reactions [58]. The hybrid material demonstrated optimal adsorption performance when one-third of the ammonium ions were substituted. This suggested that the non-active ammonium ions in AMP could be replaced by the hybrid element, which enhanced the stability and mechanical properties of the material while maintaining its adsorption capacity.

| Kind | Atom energy (eV) | Kind | Free energy (eV) | Binding energy (eV) | Adsorption energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo | -0.1948 | AMP | -505.917 | -502.6947 | - |

| O | -0.0180 | NH4+ | -20.8477 | -20.803 | - |

| P | -0.0308 | AMP-Sn1 | -486.373 | -483.187 | -1.288 |

| N | -0.01882 | AMP-Sn2 | -466.537 | -463.388 | -2.285 |

| H | -0.00637 | AMP-Sn1-Cs1 | -465.814 | -462.601 | -0.144 |

| Cs | -0.07209 | AMP-Sn1-Cs2 | -445.155 | -441.914 | -0.188 |

| Sn | -0.00728 | AMP-Sn2-Cs1 | -445.809 | -442.633 | 0.025 |

Conclusion

In this study, a series of Sn-doped AMP adsorbents were successfully prepared via the chemical co-precipitation method for the efficient removal of cesium from radioactive waste solutions. Through various characterizations, the best-performing adsorbent, SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe), was selected, and its adsorption mechanisms and performance were further investigated in detail. The SnII0.5SnIV0.5(NH4)2[P(Mo3O10)4] (add Fe) exhibited excellent chemical stability, adsorption selectivity and reusability for Cs. The adsorption of Cs follows a exothermic, monolayer chemisorption process, with a saturated adsorption capacity of 115 mg/g. DFT simulations revealed that following hybridization, Sn replaced an inactive ammonium ion in AMP and enhanced the performance of the remaining two active ammonium ions and hybrid molecules. This process improved both the stability and adsorption performance of the material. This work provides an effective approach for designing high-performance adsorbents for Cs separation. In addition, to meet the requirements property of hybrid material, more stringent synthesis control, such as types of hybridizing agent, reaction rate, aging time and son on is needed.

Sustainability-oriented prioritization of nuclear fuel cycle transitions in China: a holistic MCDM framework under uncertainties

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 158 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01504-3Extraction chromatography-electrodeposition (EC-ED) process to recover palladium from high-level liquid waste

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 175 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0327-3Theoretical analysis of long-lived radioactive waste in pressurized water reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00911-0New insight into the adsorption of ruthenium, rhodium, and palladium from nitric acid solution by a silica-polymer adsorbent

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 34 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-0744-6Removal of cesium from radioactive wastewater using magnetic chitosan beads cross-linked with glutaraldehyde

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 43 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0033-6Solidification performance and mechanism of typical radioactive nuclear waste by geopolymers and geopolymer ceramics: A review

. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 169,H2Ti6O13 Nanosheet/ Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) for the adsorption of cesium ions

. J. Solid. State. Chem. 324,The correlation between small papillary thyroid cancers and gamma radionuclides Cs-137, Th-232, U-238 and K-40 using spatially-explicit, register-based methods

. Spat. Spatio-Temporal. 47,The mechanism and behavior of cesium adsorption from aqueous solutions onto carbonated cement slurry powder

. J. Environ. Radioactiv. 272,Recovery of cesium ions from seawater using a porous silica-based ionic liquid impregnated adsorbent

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 54, 1597-1605 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.10.026The effect of temperatures and -ray irradiationon silica-based calix[4]arene-R14 adsorben tmodified with surfactants for the adsorption of cesium from nuclear waste solution

. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 103, 222-226 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2014.06.004Stable solidification of cesium with an allophane additive by a pressing/sintering method

. J. Nucl. Mater. 485, 39-46 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2016.12.029Cesium separation from radioactive waste by extraction and adsorption based on crown ethers and calixarenes

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 52, 328-336 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2019.08.001Rapid and selective removal of Cs+ and Sr2+ ions by two zeolite-type sulfides via ion exchange method

. Chem. Eng. J. 442,Prussian blue analogs-based layered double hydroxides for highly efficient Cs+ removal from wastewater

. J. Hazard. Mater. 410,Synthesis, characterization, and caesium adsorbent application of trigonal zinc hexacyanoferrate (II) nanoparticles

. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9,The behavior of cesium adsorption on zirconyl pyrophosphate

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 60 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0054-1Selective separation and recovery of cesium by ammonium tungstophosphate-alginate microcapsules

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 241, 4750-4757 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2011.03.031One-step direct synthesis of mesoporous AMP/SBA-15 using PMA as acid media and its use in cesium ion removal

. J. Nucl. Mater. 527,Ammonium molybdophosphate/metal-organic framework composite as an effective adsorbent for capture of Rb+ and Cs+ from aqueous solution

. J. Solid. State. Chem. 306,Composite Zn(II) Ferrocyanide/Polyethylenimine Cryogels for Point-of-Use Selective Removal of Cs-137 Radionuclides

. Molecules. 26, 4604 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26154604Efficient removal of Cs ion by electrochemical adsorption and desorption reaction using NiFe Prussian blue deposited carbon nanofiber electrode

. J. Hazard. Mater. 443,Selective removal of cesium and strontium by crystalline silicotitanates

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 312, 507-515 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-017-5249-3Metal chalcogenides as ion-exchange materials for the efficient removal of key radionuclides: A review

. Fundamental Research (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2023.10.022Zirconium based metal-organic framework as highly efficient and acid-stable adsorbent for the rapid removal of Sr2+ and Cs+ from solution

. 335,Solvothermally and non-solvthermally fabricated covalent organic frameworks (COFs) for eco-friendly remediation of radiocontaminants in aquatic environments: A review

. J. Organomet. Chem. 1005,Development of adsorption and solidification process for decontamination of Cs-contaminated radioactive water in Fukushima through silica-based AMP hybrid adsorbent

. Sep. Purif. Technol. 181, 76-84 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2017.03.019The effect of gamma irradiation on the physiochemical properties of Caesium-Selective ammonium phosphomolybdate-polyacrylonitrile (AMP-PAN) composites

. Clean Technol. 1, (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol1010020Dendrimer modified composite magnetic nano-flocculant for efficient removal of graphene oxide

. Sep. Purif. Technol. 307,Quinolinephosphomolybdate as ion exchanger: synthesis, characterization, and application in separation of 90Y from 90Sr

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 287, 55-59 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-010-0688-0Nanostructured zirconium phosphate as ion exchanger: synthesis, size dependent property and analytical application in radiochemical separation

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 85, 34-38 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.10.018Radioanalytical separation and size-dependent ion exchange property of micelle-directed titanium phosphate nanocomposites

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 299, 1565-1570 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-013-2815-1Cerium(III) molybdate nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and radionuclides adsorption studies

. J. Hazard. Mater. 215-216, 266-271 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.02.064.Synthesis of Cu-doped ZnS nano-powder by chemical co-precipitation process

. Mater. Today-Proc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.02.419Preparation of a CeO2–ZrO2 based nano-composite with enhanced thermal stability by a novel chelating precipitation method

. Ceram. Int. 47, 33057-33063 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.206Silver nanoparticles catalyzed electrochemical hydrodechlorination of dichloromethane to methane in N, N-Dimethylformamide using water as hydrogen donor

. Sep. Purif. Technol. 331,Morphological and microstructural evolutions of chemical vapor reaction-fabricated SiC under argon ion irradiation

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 541, 151-160 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2023.05.066Integrated sensing array of the perovskite-type LnFeO3 (Ln=La, Pr, Nd, Sm) to discriminate detection of volatile sulfur compounds

. J. Hazard. Mater. 413,FeIIIxSnIIySnIV1-x-yHnP(Mo3O10)4]·xH2O new nano hybrid, for effective removal of Sr(II) and Th(IV)

. 307, 941-953 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-015-4295-yStudies on the co-polymerization of Sn and Fe solutions

. CIESC Journal. 50, 262-266 (1999). https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0438-1157.1999.02.017 (in Chinese)Synthesis and high-temperature phase transformation behavior of Dy2O3–Sc2O3 co-stabilized ZrO2 powders prepared by cocurrent chemical coprecipitation

. Ceram. Int. 50, 22395-22404 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.03.340.Crystallographic study of the ammonium/potassium 12-molybdophosphate ion-exchange system

. J. Solid. State. Chem. 18, 191-199 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(76)90095-5Selective separation of Pd(II) through ion exchange and oxidation-reduction with hexacyanoferrates from high-level liquid waste

. Sep. Purif. Technol. 231,Template-free synthesis of MnO2 nanowires with secondary flower like structure: characterization and supercapacitor behavior studies

. Curr. Appl. Phys. 12, 193-198 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cap.2011.05.038Investigation of the mechanism and interaction of nitrogen conversion during lignin/glutamic acid co-pyrolysis

. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 183,Enhanced termination of zinc and cadmium ions from wastewater employing plain and chitosan-modified mxenes: synthesis, characterization, and adsorption performance

. Green. Ch. E. 5, 339-347 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gce.2023.08.003The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge

. X. Update. Adv. Colloid. Interfac. 5, 339-347 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gce.2023.08.003Radioactive cesium removal from nuclear wastewater by novel inorganic and conjugate adsorbents

. Chem. Eng. J. 242, 127-135 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.12.072Competitive adsorption of Pb(II) and phenol onto modified chitosan/vermiculite adsorbents

. J. Polym. Environ. 30, 4238-4251 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-022-02515-0Chitosan-vermiculite composite adsorbent: Preparation, characterization, and competitive adsorption of Cu(II) and Cd(II) ions

. J. Water Process. Eng. 59,Adsorption isotherm models: classification, physical meaning, application and solving method

. Chemosphere. 258,Development of chromatographic process for the dynamic separation of 90Sr from high level liquid waste through breakthrough curve simulation and thermal analysis

. Sep. Purif. Technol. 282,Synthesis of cubic mesoporous silica SBA16 functionalized with carboxylic acid in a one-pot process for efficient removal of wastewater containing Cu2+: Adsorption isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics

. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 382,Efficient separation of Cd2+ and Pb2+ by Tetradesmus obliquus: Insights from cultivation conditions with competitive adsorption modeling

. J. Water Process. Eng. 60,Rethinking of the intraparticle diffusion adsorption kinetics model: Interpretation, solving methods and applications

. Chemosphere. 309,From wastes to functions: A paper mill sludge-based calcium-containing porous biochar adsorbent for phosphorus removal

. J. Colloid. Interf. Sci. 593, 434-446 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.02.118Simultaneous adsorption of phosphate and tetracycline by calcium modified corn stover biochar: Performance and mechanism

. Bioresource Technology. 359,Selective separation and immobilization process of 137Cs from high-level liquid waste based on silicon-based heteropoly salt and natural minerals

. Chem. Eng. J. 449,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.