INTRODUCTION

Transuranic isotopes [1] are isotopes of elements with atomic numbers greater than uranic (element 92), such as californium-252 (252Cf), curium-242 (242Cm), americium-241 (241Am), and plutonium-238 (238Pu). These isotopes are widely used in industry, agriculture, medicine, and national defense [2]. For example, 252Cf, with its high neutron source intensity and continuous energy spectrum, is used as a neutron source for reactor startup [3]; 238Pu, characterized by its long half-life, high thermal power density, and easy shielding of α-decay, is employed as radioactive heat sources [4], and 241Am, a high-quality low-energy gamma source, is utilized in smoke detectors and isotope thickness gauges [5]. Currently, only the United States and Russia possess stable production capabilities for transuranic isotopes. However, during the past 60 years, the United States has only produced 10.2 grams of 252Cf [6]. Therefore, transuranic isotopes are scarce strategic materials.

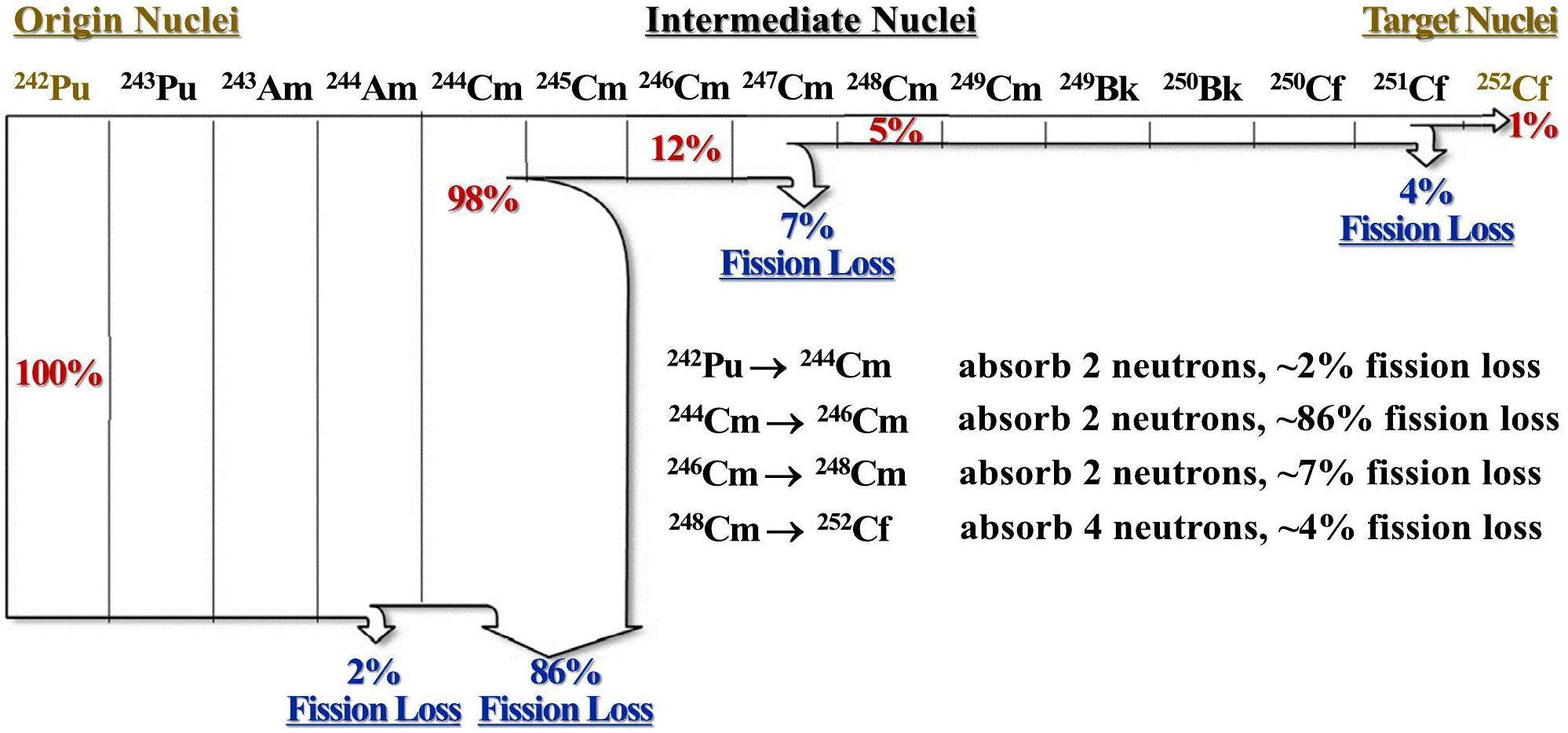

Transuranic isotopes are primarily produced through reactor irradiation, but this process faces the challenges of low nuclide conversion rates and high production costs [7]. Taking the production of 252Cf through the irradiation of 242Pu as an example, as shown in Fig. 1, this process requires 242Pu to absorb ten neutrons continuously without undergoing fission reactions. Otherwise, all previous efforts would be wasted. However, the nuclide conversion chain consists of neutron-rich nuclides, which are prone to fission reactions, leading to fission losses of up to 99% [8]. Neutrons of different energy regions have different capacities for inducing various nuclear reactions, and regulating the neutron spectrum can control the nuclear reaction process [9]. Therefore, by adjusting the neutron spectrum within the irradiation channel, fission losses can be reduced, and the production efficiency of transuranic isotopes can be increased by up to 65 times [10]. However, this process faces two challenges: (1) determining the optimal neutron spectrum for transuranic isotope production and (2) determining how to construct the optimal neutron spectrum.

Regarding the first challenge, the research team at Shanghai Jiao Tong University conducted studies to identify the optimal neutron spectrum for transuranic isotope production. (1) Rapid diagnostic method [10]: The relationship between production efficiency and neutron spectrum was established, and the concept of energy spectrum total value replaced burnup calculation for efficient evaluation of irradiation schemes. However, this method can only consider the initial neutron spectrum and nuclide composition of the initial target, resulting in theoretical flaws. (2) Key nuclide analysis method [11]: The most negative nuclides (key nuclides) during the entire irradiation period were found, and the production efficiency was improved by suppressing the nuclear reactions of these key nuclides. However, this method fails to consider the dynamic evolution of the neutron spectrum and still has theoretical flaws. (3) Subgroup-burnup and extreme-burnup analysis methods [12]: The values of neutrons in different energy ranges for transuranic isotope production were quantified, and all nuclides and all neutron spectra throughout the entire irradiation period were considered. However, the results of these two methods are influenced by reactor parameters (neutron flux and irradiation duration), limiting their universal applicability. (4) Optimal spectrum database [13]: Genetic algorithms and point burnup calculations were combined to search for the theoretically optimal neutron spectrum under different irradiation durations and neutron fluxes, which comprehensively answers the first question from a scientific perspective.

Regarding the second challenge, neutron spectrum regulation is difficult because neutrons are electrically neutral, unlike charged particles, such as electrons and protons. Current research on this topic is still in its nascent stages and is characterized by four defects: (1) a narrow energy range for neutron spectrum regulation, (2) low spectral resolution during the regulation process, (3) large deviation between the actual and target spectra, and (4) poor universality in terms of the source and target spectra. For example, based on the findings of the first challenge, the research team at Shanghai Jiao Tong University adopted spectrum filtering technology [11] for neutron spectrum regulation, thereby enhancing the production efficiency of transuranic isotopes. However, this method can only reduce the neutron flux at a single energy point or within a narrow energy range, limiting its spectral regulation capabilities. Muhrer [14] proposed the “golden rule” to define the relationship between the neutron moderation effect and the hydrogen content in the moderating material, which can guide the process of neutron moderation. However, the neutron spectrum resolution that can be achieved using this process is low. Scherr and Tsvetkov [15] relied on manual experience to adjust the materials and geometric dimensions of the regulation modules to match the reactor spectrum to the target spectrum. However, this iterative trial-and-error method struggles to ensure the accuracy of the regulation results and is labor intensive. Cao [16] suggested an inverse correction method for spectrum regulation; however, it is constrained by the low precision of spectrum calculations and the limitations of the regulation modules, which restrict the achievable target spectra. Therefore, technology capable of achieving high-precision and high-universality neutron spectrum regulation across the full energy range with high spectral resolution remains lacking.

A method for high-resolution neutron spectrum regulation across the full energy range is proposed. It can be applied to improve the yield of transuranic isotopes by optimizing the neutron spectrum. The remainder of this article is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, the methods are introduced. The applications are discussed in Sect. 3. Section 4 concludes the article.

Methods

Rapid Calculation of Neutron Spectrum

A genetic algorithm [17] was employed for neutron spectrum optimization. A large number of irradiation schemes are screened, necessitating a rapid algorithm for calculating the neutron spectrum, where a previously proposed method [18] was adopted.

Assuming that a neutron with energy Ei undergoes a nuclear reaction with a non-absorbing nuclide, the energy of the neutron then changes to

To consider absorption reactions, each row of the matrix is normalized,

Equation (4) makes the sum of each row of Rk less than 1.0, causing the norm of V1 also to be less than 1.0, where Eq. (3) fails to yield a stable neutron spectrum. In this case, V0 is used to supplement the reduction in V1 after each iteration,

To consider the presence of multiple nuclides in a material, the spectrum response matrices of each nuclide are used to form a spectrum response matrix of this material,

To consider different geometries, the leakage of neutrons is calculated because some neutrons fly out of the system without reaction. The probability pi of a neutron not undergoing a collision can be derived based on the exponential decay law,

High-Resolution Spectrum Regulation

Equation (8) indicates that the response relationship of neutron spectra is correlated with the isotopic composition of the materials. Therefore, the neutron spectrum can be modulated by altering the isotopic composition within a spatial region. The spectrum response matrices of 423 isotopes were built, and the full energy range was divided into 238 energy bins [19] to enhance the spectral resolution and precision of neutron spectrum regulation.

The source neutron spectrum (n energy bins) is denoted as ψin = {x1, x2, · ·· ·, xn}, and the output neutron spectrum is denoted as ψout = {y1, y2, · ·· ·, yn}. A stable output neutron spectrum can be obtained from the iterative convergence of Eq. (3),

Combining Eqs. (12) and (13), one obtains

Yield Maximum with Optimal Spectrum Regulation

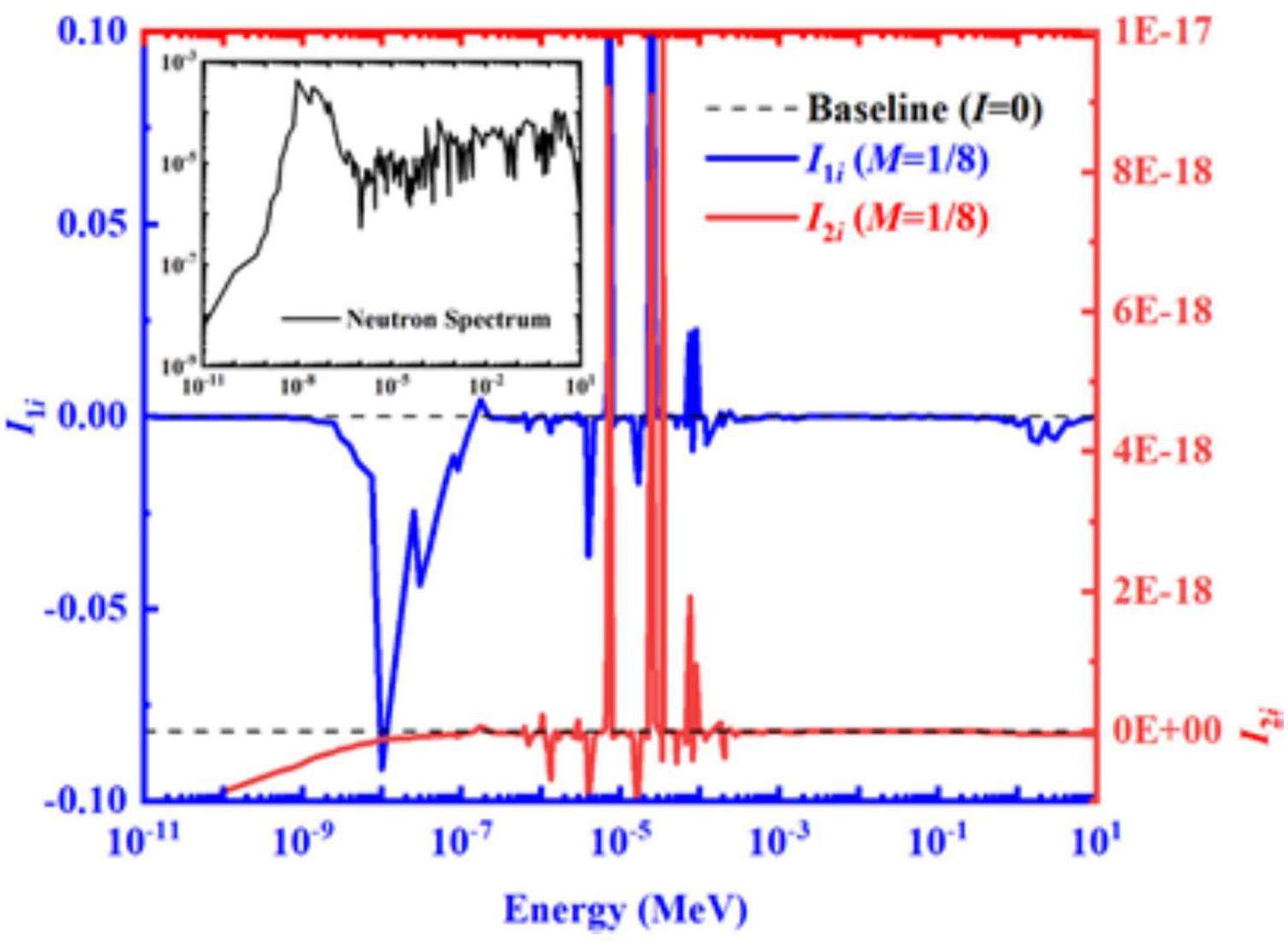

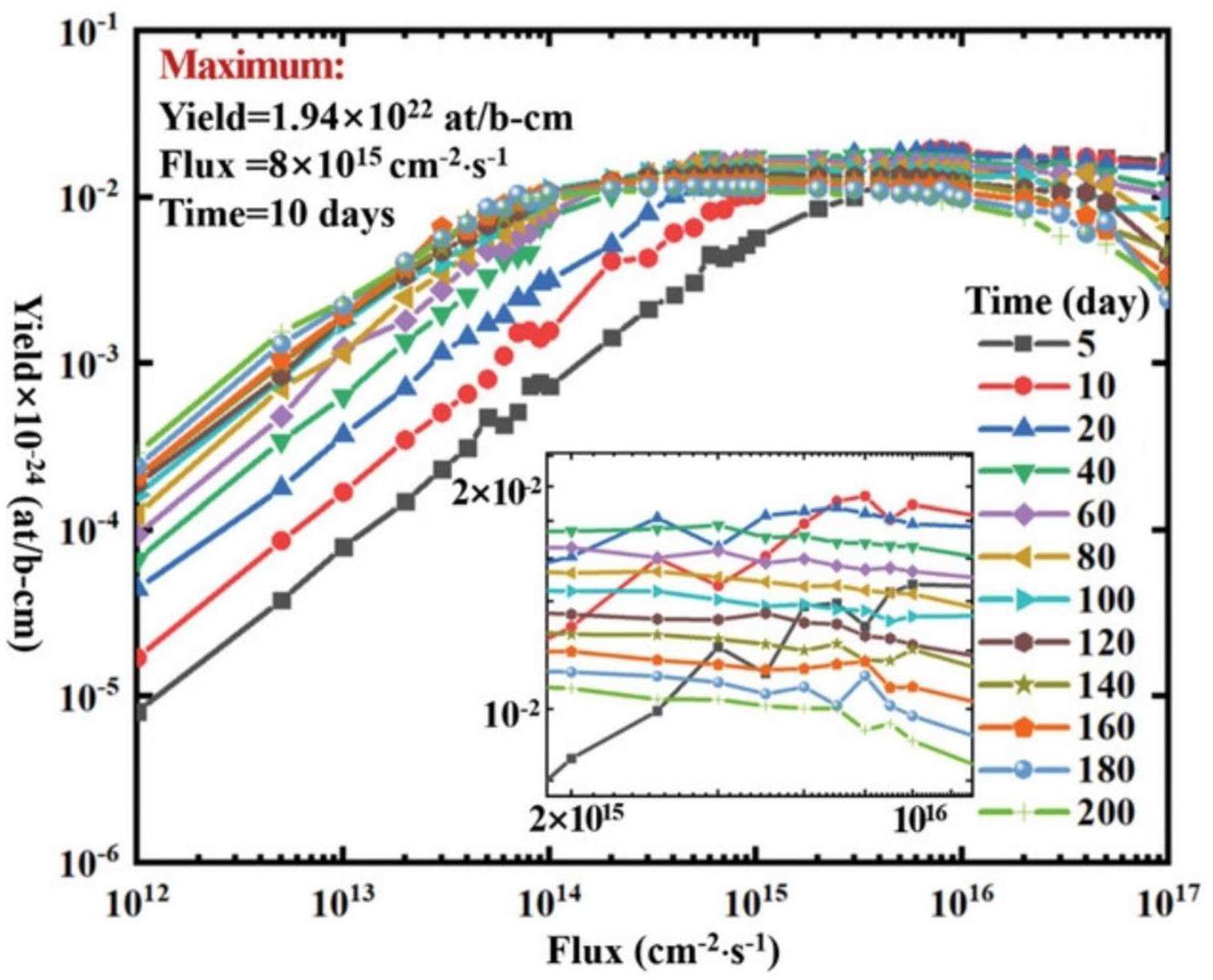

Previous studies have demonstrated that transuranic isotope production can be improved greatly by neutron spectrum optimization and have provided the importance curves that quantify the values of neutrons in various energy bins for the production of transuranic isotopes [12], as shown in Fig. 2. To determine the optimal neutron spectrum further, a genetic algorithm was employed to build an optimal spectrum database that provides the optimal neutron spectra under different neutron fluxes and irradiation durations [13]. The theoretical maximum yields of 238Pu under different irradiation conditions are shown in Fig. 3. Therefore, once this optimal neutron spectrum is constructed within the target, the yields of transuranic isotopes can be maximized.

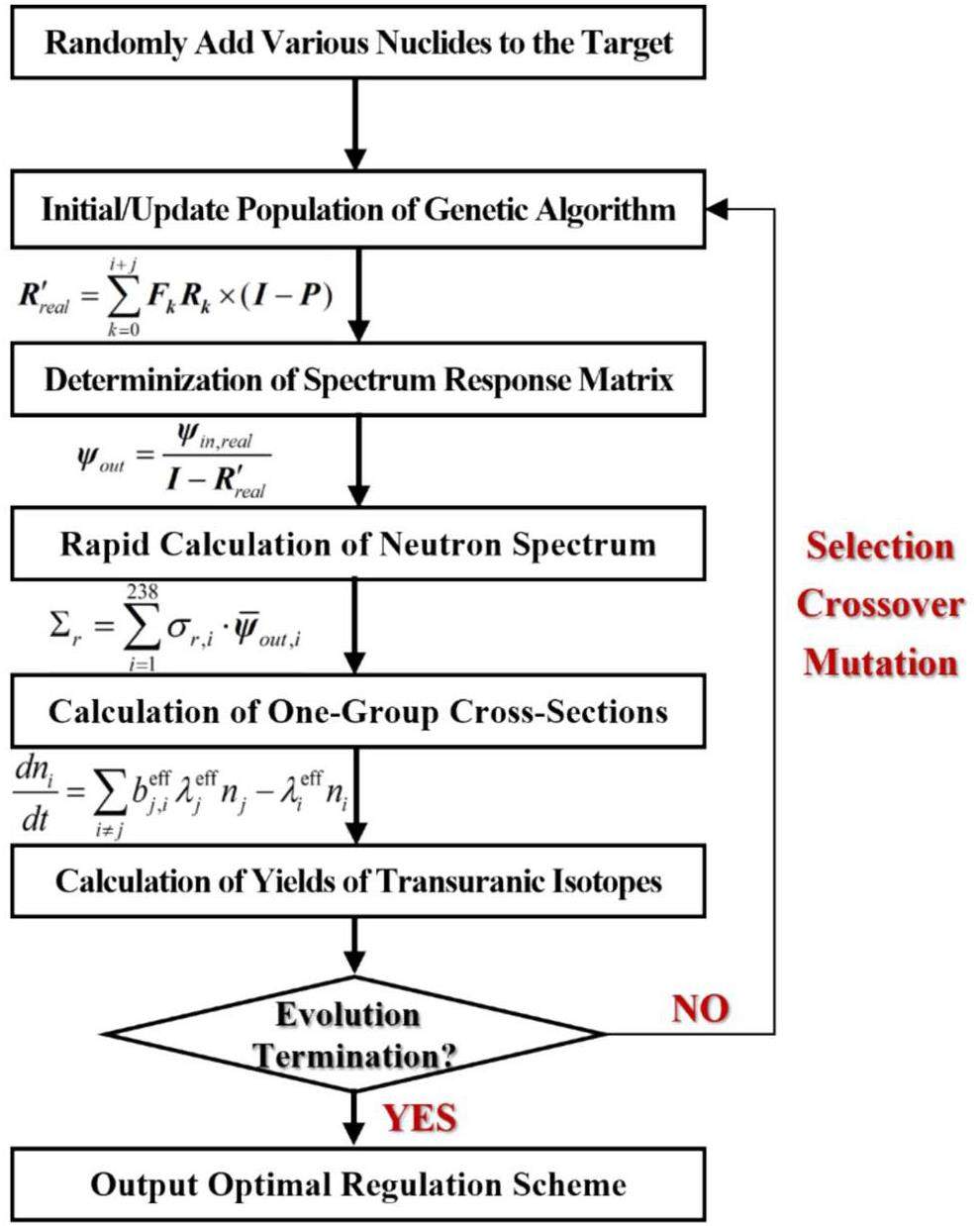

To construct the optimal neutron spectrum inside the target based on an initial irradiation scheme, it is necessary to build a spectrum response matrix that converts the initial neutron spectrum into the optimal one. However, it is impossible to construct the optimal neutron spectrum using only the spectrum response matrices of these 423 nuclides. Therefore, a genetic algorithm is employed to search for the optimal proportions of these 423 nuclides, such that the neutron spectrum inside the target is closest to the optimal one, thereby maximizing the yields of transuranic isotopes. As shown in Fig. 4, the specific calculation process is as follows.

(1) Constructing the initial population for the genetic algorithm: Various nuclides are randomly added to the target, constructing different neutron spectrum regulation schemes. Assuming that there are originally i types of nuclide in the target, the spectrum response matrix inside the target at this time is

(2) Calculation of the neutron spectrum inside the target: In the case of a known fixed source term, the neutron spectrum can be directly calculated using Eq. (14). However, because the incident neutron spectrum of the irradiation channel also changes after the target material is modified, the incident neutron spectrum must be updated according to the nuclide composition of the target. Linear interpolation is used to provide the incident neutron spectra for various nuclide compositions inside the target, as shown in Fig.5.

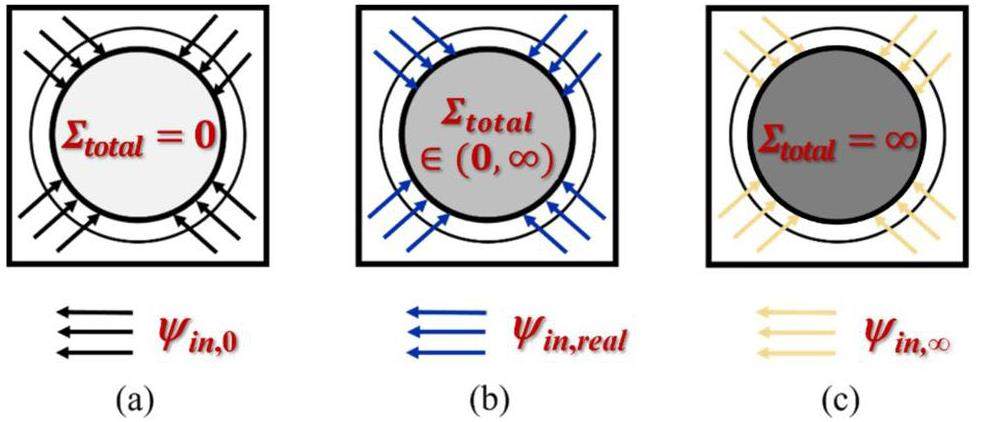

To accomplish this, one first must determine two initial source terms: the incident neutron spectra ψin,0 and ψin,∞ when the cross sections of the material in the irradiation channel are zero and infinity, respectively. Then, the non-collision probability P in Eq. (9) is used as the interpolation factor to calculate the incident neutron spectrum for different nuclide compositions inside the target,

After the spectrum response matrix of the target and incident initial neutron spectrum are determined, the neutron spectrum inside the target can be quickly calculated using the following equation:

(3) Calculating the yields of transuranic isotopes: To meet the high computational demand of the genetic algorithm, the yields of transuranic isotopes are calculated by solving the burnup equation [20, 21],

The one-group macroscopic cross sections ∑r of a neutron spectrum needed by the point burnup calculation are calculated by

(4) Performing evolutionary operations on the population: With the yield of transuranic isotopes as the optimization objective, the population is screened, crossed, and mutated to obtain a new population. Step (2) is then repeated until the evolution of the population is completed.

(5) Outputting the optimal neutron spectrum regulation scheme: The optimal neutron spectrum regulation scheme is described in terms of the types and proportions of nuclides added to the target, along with the yields of transuranic isotopes under this optimal scheme and its enhancement effect compared with the original production scheme.

The nuclear data, such as decay data, cross-section data, and fission yield data required for the neutron spectrum and burnup calculation in this study, all originate from ENDF/B-VII.1 [9]. The spatial self-shielding effect of the target can be considered during neutron energy spectrum calculation.

AApplications

State-of-the-Art Irradiation Scheme

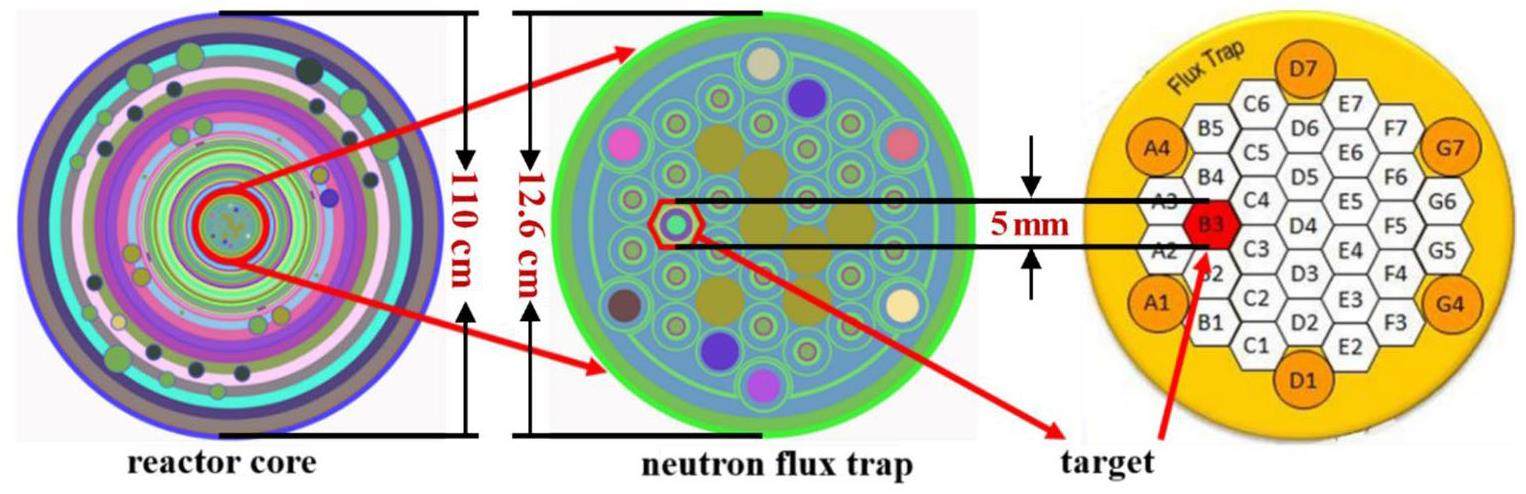

The High-Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) [22] is currently the primary facility for transuranic isotope production, accounting for 70% of the global 252Cf supply. HFIR has a steady-state neutron thermal flux of 2.5 × 1015 cm−2·s−1 and a refueling cycle of 25 days. HFIR and the target are modeled using the RMC code [23–25], as shown in Fig. 6.

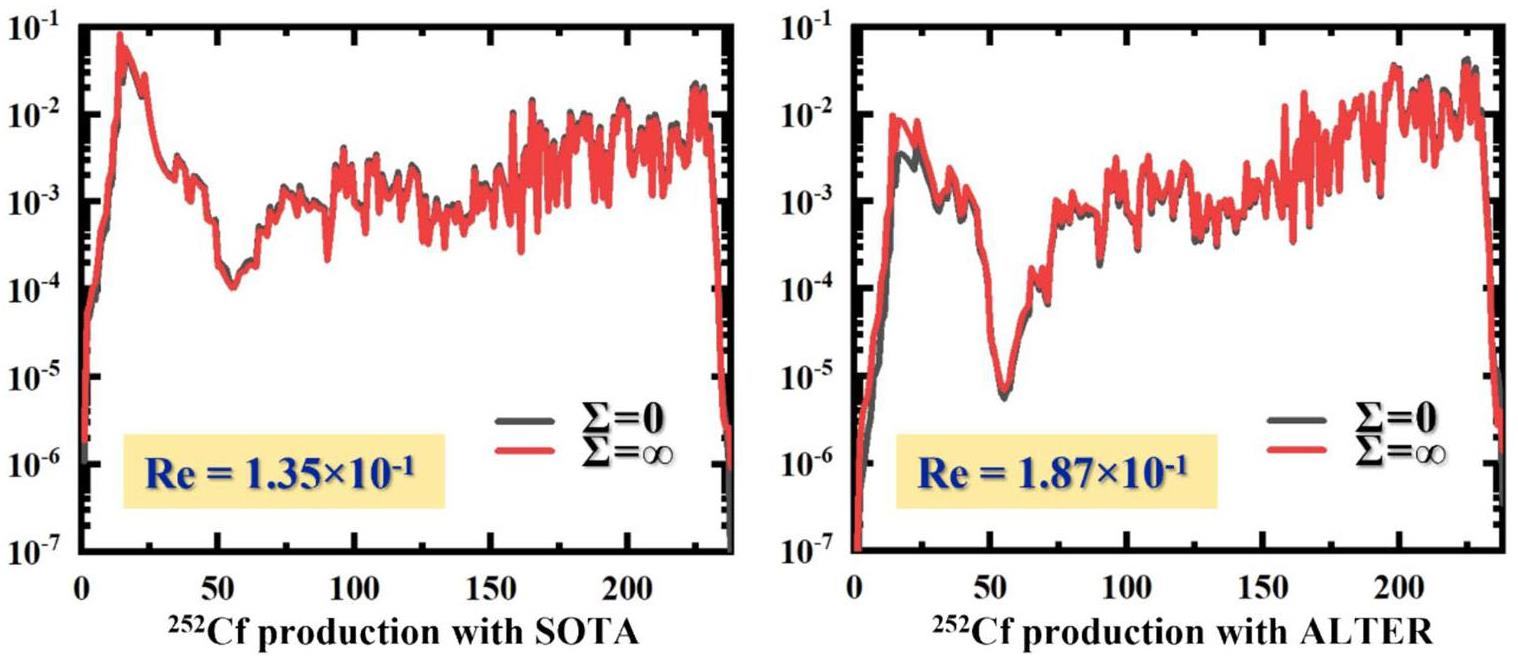

The volumetric neutron spectrum inside the target is changed by adding various nuclides to it. The state-of-the-art irradiation scheme (called “SOTA”) employs a target with a diameter of 5 mm, whereas the diameter of the reactor is 110 cm, resulting in an extremely narrow range for neutron spectrum regulation. For comparison, an alternative irradiation scheme (called “ALTER”) was envisioned in which targets are placed throughout the entire neutron flux trap. In this hypothetical scenario, the diameter of the target is 12.6 cm, which has a larger range of neutron spectrum regulation than SOTA. Monte Carlo simulations were employed to obtain the incident neutron spectra when the cross sections of the target are zero and infinity. Furthermore, based on Eqs. (19) and (20), the adjustable range of the neutron spectrum for 252Cf production using the two irradiation schemes was calculated, as shown in Fig.7. The average relative deviation (Ave.Re) of the neutron spectrum is used to measure its adjustable range,

Table 1 presents the Ave.Re of the incident neutron spectra, the volumetric neutron spectrum inside the target for 252Cf and 238Pu (two types of target) production when the cross sections of the target are zero and infinity.

| Scheme | Incident | 252Cf | 238Pu (237Np) | 238Pu (241Am) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOTA | 1.38 × 10−1 | 1.35 × 10−1 | 7.53 × 10−2 | 1.01 × 10−1 |

| ALTER | 2.14 × 10−1 | 1.87 × 10−1 | 2.22 × 10−1 | 2.30 × 10−1 |

As shown in Fig. 7 and Table 1, the range for neutron spectrum regulation is small, which makes neutron spectrum optimization extremely difficult. The HFIR irradiation scheme of transuranic isotope production, which is currently the optimal irradiation scheme available, is chosen as the initial approach in this study. If the research presented in this paper can further enhance these state-of-the-art irradiation schemes through neutron spectrum regulation, the significance of our work can be demonstrated.

In the subsequent analysis, the neutron spectrum within the flux trap and target is adopted as the starting point for neutron spectrum regulation. The neutron flux for point burnup calculations is 2.5 × 1015 cm−2·s−1, with a burnup time of 25 days, which is divided into 10 subburnup steps. During the calculation process, the genetic algorithm is first used to search for and identify the 20 most important nuclides for enhancing the yield of transuranic isotopes. The concentrations of these 20 nuclides are then optimized. Hence, in the next section, the addition of these 20 most important nuclides for yield improvement is discussed.

Volumetric Neutron Spectrum Regulation for 252Cf Production

The target for 252Cf production is a mixture of plutonium, americium, and curium [26, 27], whose nuclide components are listed in Table 2. The calculation procedure outlined in Fig. 4 was used to optimize the neutron spectrum for the SOTA and ALTER irradiation schemes.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16O | 3.68 × 1021 | 56Fe | 7.66 × 1019 | 242mAm | 1.33 × 1017 |

| 27Al | 4.72 × 1022 | 57Fe | 1.74 × 1018 | 243Am | 1.18 × 1020 |

| 40Ca | 7.38 × 1019 | 58Fe | 2.27 × 1017 | 242Cm | 3.71 × 1016 |

| 42Ca | 4.69 × 1017 | 238Pu | 1.86 × 1018 | 243Cm | 2.61 × 1017 |

| 43Ca | 9.56 × 1016 | 239Pu | 1.66 × 1017 | 244Cm | 3.60 × 1020 |

| 44Ca | 1.44 × 1018 | 240Pu | 3.51 × 1019 | 245Cm | 8.44 × 1018 |

| 46Ca | 2.65 × 1015 | 241Pu | 1.12 × 1016 | 246Cm | 1.11 × 1021 |

| 48Ca | 1.19 × 1017 | 242Pu | 4.63 × 1017 | 247Cm | 3.14 × 1019 |

| 54Fe | 5.06 × 1018 | 241Am | 3.29 × 1019 | 248Cm | 2.46 × 1021 |

For the SOTA irradiation scheme, the yield of 252Cf after 25-day irradiation of this target in HFIR is 1.33 × 1018 atom/cm3. After the nuclides listed in Table 3 are added to the target, a maximum yield of 1.49 × 1018 atom/cm3 can be achieved, a 12.16% increase compared with the original SOTA irradiation scheme.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | 5.14 × 1020 | 73Ge | 5.25 × 1020 | 140La | 4.93 × 1020 |

| 9Be | 4.51 × 1020 | 74Ge | 5.04 × 1020 | 200Hg | 4.45 × 1020 |

| 36Ar | 5.20 × 1020 | 101Ru | 5.20 × 1020 | 204Hg | 4.72 × 1020 |

| 38Ar | 4.88 × 1020 | 105Ru | 4.45 × 1020 | 206Pb | 5.25 × 1020 |

| 58Ni | 5.25 × 1020 | 102Pd | 5.14 × 1020 | 208Pb | 5.20 × 1020 |

| 59Ni | 1.06 × 1019 | 106Pd | 5.25 × 1020 | 209Bi | 5.25 × 1020 |

| 65Cu | 5.09 × 1020 | 136Ce | 5.09 × 1020 |

For the ALTER irradiation scheme, the yield of 252Cf after 25-day irradiation of this target in HFIR is 1.15 × 1017 atom/cm3. After the nuclides listed in Table 4 are added to the target, a maximum yield of 1.77 × 1017 atom/cm3 can be achieved, which is a 54.54% increase compared with the original ALTER irradiation scheme.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | 1.59 × 1019 | 12C | 5.25 × 1020 | 33S | 5.14 × 1020 |

| 2H | 4.72 × 1020 | 15N | 4.56 × 1020 | 34S | 4.98 × 1020 |

| 3H | 4.93 × 1020 | 17O | 4.83 × 1020 | 36S | 5.20 × 1020 |

| 4He | 4.77 × 1020 | 28Si | 4.88 × 1020 | 37Cl | 5.25 × 1020 |

| 7Li | 4.77 × 1020 | 29Si | 4.56 × 1020 | 40Ar | 5.20 × 1020 |

| 9Be | 4.35 × 1020 | 30Si | 5.20 × 1020 | ||

| 11B | 5.04 × 1020 | 32S | 4.51 × 1020 |

The nuclides listed in Tables 3 and 4 are added to the target by dispersion, with the density of the added nuclides not exceeding 1% of the initial nuclide density of the target. After the addition of the nuclides, the density of the original nuclides in the target decreases accordingly. Meanwhile, in this study, a high-resolution neutron spectrum regulation method, achieved by adjusting the proportions of these 423 nuclides within a certain spatial region, was developed. Theoretically, the more the nuclides that can be used for neutron spectrum regulation, the higher the regulation capability. However, many nuclides are unstable and extremely expensive, which makes them difficult to use in practical engineering applications. Therefore, it is recommended that readily available nuclides or natural elements be adopted to develop neutron spectrum regulation schemes in practical engineering.

Volumetric Neutron Spectrum Regulation for 238Pu Production

238Pu is produced by the in-reactor irradiation of americium-241 (241Am) [28, 29] or neptunium-237 (237Np) [30, 31], with the nuclide components of the targets listed in Table 5. Experience has shown that the in-reactor irradiation of 237Np facilitates a higher yield of 238Pu, whereas the in-reactor irradiation of 241Am facilitates a higher abundance of 238Pu. Therefore, these two irradiation methods are currently the practical solutions adopted, and analyses of both methods were conducted.

| AmO2 | NpO2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

| 16O | 5.11 × 1022 | 16O | 4.97 × 1022 |

| 241Am | 2.55 × 1022 | ||

| 242Am | 2.04 × 1017 | 237Np | 2.49 × 1022 |

| 243Am | 1.06 × 1019 | ||

In-reactor irradiation of 241Am

For the SOTA irradiation scheme, the yield of 238Pu after 25-day irradiation of the AmO2 target in HFIR is 3.11 × 1020 atom/cm3. After the nuclides listed in Table 6 are added to the target, a maximum yield of 3.92 × 1020 atom/cm3 can be achieved, a 25.84% increase compared with the original SOTA irradiation scheme.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 184W | 7.43 × 1020 | 205Ti | 7.51 × 1020 | 226Ra | 7.13 × 1020 |

| 198Hg | 7.28 × 1020 | 204Pb | 6.74 × 1020 | 225Ac | 7.28 × 1020 |

| 200Hg | 7.28 × 1020 | 206Pb | 7.36 × 1020 | 230Th | 7.59 × 1020 |

| 201Hg | 7.51 × 1020 | 207Pb | 7.59 × 1020 | 232Th | 7.59 × 1020 |

| 202Hg | 7.43 × 1020 | 208Pb | 7.51 × 1020 | 234Th | 7.28 × 1020 |

| 204Hg | 7.28 × 1020 | 209Bi | 7.13 × 1020 | ||

| 203Ti | 7.59 × 1020 | 224Ra | 7.13 × 1020 |

For the ALTER irradiation scheme, the yield of 238Pu after 25-day irradiation of the AmO2 target in HFIR is 1.14 × 1019 atom/cm3. After the nuclides listed in Table 7 are added to the target, a maximum yield of 2.08 × 1019 atom/cm3 can be achieved, an 81.83% increase compared with the original ALTER irradiation scheme.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 164Er | 7.51 × 1020 | 202Hg | 7.13 × 1020 | 208Pb | 7.05 × 1020 |

| 168Er | 7.59 × 1020 | 204Hg | 7.59 × 1020 | 209Bi | 7.05 × 1020 |

| 180Hf | 7.20 × 1020 | 203Ti | 7.13 × 1020 | 226Ra | 7.05 × 1020 |

| 184W | 7.36 × 1020 | 205Ti | 7.43 × 1020 | 230Th | 7.13 × 1020 |

| 198Hg | 6.90 × 1020 | 204Pb | 7.28 × 1020 | 232Th | 7.28 × 1020 |

| 200Hg | 7.51 × 1020 | 206Pb | 6.82 × 1020 | ||

| 201Hg | 7.43 × 1020 | 207Pb | 7.36 × 1020 |

In-reactor irradiation of 237Np

For the SOTA irradiation scheme, the yield of 238Pu after 25-day irradiation of the NpO2 target in HFIR is 2.99 × 1021 atom/cm3. After the nuclides listed in Table 8 are added to the target, a maximum yield of 3.21 × 1021 atom/cm3 can be achieved, a 7.53% increase compared with the original SOTA irradiation scheme.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170Er | 7.38 × 1020 | 201Hg | 7.30 × 1020 | 207Pb | 7.08 × 1020 |

| 180Hf | 6.78 × 1020 | 202Hg | 7.38 × 1020 | 208Pb | 6.33 × 1020 |

| 180W | 6.93 × 1020 | 204Hg | 6.70 × 1020 | 209Bi | 6.63 × 1020 |

| 184W | 7.38 × 1020 | 203Ti | 6.56 × 1020 | 224Ra | 7.30 × 1020 |

| 186W | 6.70 × 1020 | 205Ti | 7.15 × 1020 | 232Th | 7.23 × 1020 |

| 198Hg | 7.30 × 1020 | 204Pb | 6.85 × 1020 | ||

| 200Hg | 6.93 × 1020 | 206Pb | 6.85 × 1020 |

For the ALTER irradiation scheme, the yield of 238Pu after 25-day irradiation of the NpO2 target in HFIR is 2.56 × 1020 atom/cm3. After the nuclides listed in Table 9 are added to the target, a maximum yield of 4.32 × 1020 atom/cm3 can be achieved, a 68.74% increase compared with the original ALTER irradiation scheme.

| Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) | Isotopes | Number density (atom/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 146Nd | 7.23 × 1020 | 200Hg | 6.93 × 1020 | 206Pb | 5.66 × 1020 |

| 150Nd | 6.63 × 1020 | 201Hg | 7.23 × 1020 | 207Pb | 7.30 × 1020 |

| 160Gd | 7.38 × 1020 | 202Hg | 6.93 × 1020 | 208Pb | 7.08 × 1020 |

| 168Er | 6.26 × 1020 | 204Hg | 7.38 × 1020 | 209Bi | 7.30 × 1020 |

| 180Hf | 6.78 × 1020 | 203Ti | 7.23 × 1020 | 226Ra | 6.85 × 1020 |

| 184W | 6.93 × 1020 | 205Ti | 7.30 × 1020 | 232Th | 6.70 × 1020 |

| 198Hg | 7.38 × 1020 | 204Pb | 7.38 × 1020 |

Comparison and Analyses

The yields of these irradiation schemes are compared in Table 10, showing that the volumetric neutron spectrum regulation method proposed can enhance the production of transuranic isotopes. Even for the state-of-the-art irradiation schemes that are currently optimal, one can still improve their efficiencies. Furthermore, the spectrum optimization schemes proposed are simple and feasible, requiring only the dispersion of various nuclides inside the target without the need to modify reactor design or irradiation channel parameters, making them highly practical for engineering applications.

| Scheme | Original (atom/cm3) | Optimal (atom/cm3) | Promotion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOTA | 252Cf | 1.33 × 1018 | 1.49 × 1018 | 12.16 |

| 238Pu (241Am) | 3.11 × 1020 | 3.92 × 1020 | 25.84 | |

| 238Pu (237Np) | 2.99 × 1021 | 3.21 × 1021 | 7.53 | |

| ALTER | 252Cf | 1.15 × 1017 | 1.77 × 1017 | 54.54 |

| 238Pu (241Am) | 1.14 × 1019 | 2.08 × 1019 | 81.83 | |

| 238Pu (237Np) | 2.56 × 1020 | 4.32 × 1020 | 68.74 |

A comparison between the SOTA irradiation scheme and the ALTER irradiation scheme reveals the following conclusions. (1) The SOTA irradiation scheme consistently outperforms the ALTER irradiation scheme, demonstrating the significance of neutron spectrum regulation for transuranic isotope production. (2) The larger the range for neutron spectrum regulation, the more pronounced the promotion in enhancing transuranic isotope production. Therefore, the volumetric neutron spectrum regulation method proposed can identify and construct an optimal neutron spectrum within a limited range. The calculated results provided only cover a narrow range and fail to reflect the overall physical process. In this study, only the effectiveness of this regulation scheme and its technical value are emphasized, without delving into its physical significance in detail. If further increasing the production of transuranic isotopes is required, merely altering the nuclide composition of the target is insufficient. At this point, modifications to the reactor design are necessary to broaden the regulation range of the neutron spectrum within the irradiation channels. This will be explored in planned future research.

CONCLUSION

Transuranic isotopes are scarce strategic materials primarily produced through the in-reactor irradiation of targets; however, they face the challenge of low production efficiency. Optimizing the volumetric neutron spectrum inside the target can enhance the production of transuranic isotopes. A neutron spectrum regulation method was proposed to construct the optimal volumetric neutron spectrum inside the target and apply this method to producing transuranic isotopes, improving their production efficiency.

The new method utilizes a genetic algorithm to search for the optimal neutron spectrum regulation scheme, which is divided into four modules. (1) Neutron spectrum perturbation module: This module alters the neutron spectrum inside the target by dispersing various nuclides throughout it, thereby constructing diverse neutron spectra. (2) Neutron spectrum calculation module: Leveraging the spectrum response matrices, this module swiftly obtains the neutron spectrum inside the target on a timescale of seconds. (3) Neutron spectrum valuation module: Employing the burnup calculation method, this module obtains the yield of transuranic isotopes under various neutron spectra, evaluating the fitness of each scheme. (4) Intelligent optimization module: Based on the selection, crossover, and mutation operations of the genetic algorithm, this module evolves the neutron spectrum regulation schemes to determine the optimal one.

Optimizations were performed starting from the production schemes of the HFIR. The production schemes for 252Cf and 238Pu were optimized. The optimized schemes enhance the production efficiency of 252Cf by 12.16% and increase the production efficiencies of 238Pu by 25.84% and 7.53%. Because these schemes are currently the optimal ones available, these efficiency improvements demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Furthermore, the neutron spectrum was optimized solely by dispersing nuclides within the target, without modifying the reactor design, which is an advantage from the engineering viewpoint. However, many nuclides are unstable and extremely expensive, which makes them difficult to use in practical engineering applications. Therefore, it is recommended that readily available nuclides or natural elements be adopted to develop neutron spectrum regulation schemes in practical engineering.

Production of Cf-252 and other transplutonium isotopes at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

. Radiochim. Acta, 108(9), 737-746 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1515/ract-2020-0008Production of energetic 232U, 236Pu, 238Pu, 242Cm, 248Bk, 250Cf, 252Cf and 252Es radioisotopes for use as nuclear battery in thin targets via particle accelerators

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 166,Production, distribution and application of Californium-252 neutron sources

. Appl. Radiat. Isot., 53, 785-792 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-8043(00)00214-1Initial phase of Pu-238 production in Idaho National Laboratory

. Appl. Radiat. Isot., 169,Evaluation of radiation safety for ionization chamber smoke detectors containing Am-241

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1285,US Heavy Actinide Production at Oak Ridge National Laboratory–Ongoing Actinide Partitioning and Transmutation Programs

. Proceedings of the Sixteenth Information Exchange Meeting on Actinide and Fission Product Partitioning and Transmutation (IEMPT),Increasing transcurium production efficiency through directed resonance shielding

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 60, 267-273 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2013.05.018Optimization of transcurium isotope production in the High Flux Isotope Reactor

. Doctoral Dissertation,ENDF/B-VII.1 Nuclear data for science and technology: Cross sections, covariances, fission product yields and decay data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 112(12), 2887-2996 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2011.11.002Rapid diagnosis method for transplutonium isotopes production in high flux reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 44 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01185-4Neutron spectrum optimization for Cf-252 production based on key nuclides analysis

. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 214,Spectrum importance model for heavy nuclei synthesis in reactors: Taking 252Cf as an example

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 57(6), (2025) 103426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2024.103426Optimal irradiation spectrum database for 238Pu production

. Adv. Sci. 10995 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/ADVS.202410995Urban legends of thermal moderator design

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A, 664(1), 38-47 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2011.10.018Design strategies for LWR and VHTR test environments in a fast spectrum reactor

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 120, 219-235 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2018.05.046An adaptive optimization reverse regulation method for neutron spectrum based on standardized response module

. Fusion Eng. Des. 163,Evolutionary Algorithms and Neural Networks

. Studies in Computational Intelligence, 780. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93025-1_4High-resolution rapid calculation method of neutron spectrum based on energy response

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 57(7),Analysis of major group structures used for nuclear reactor simulations

. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering,Development of the point-depletion code DEPTH

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 258, 235-240 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2013.01.007Development of a MCNP and ORIGEN2 based burnup code for molten salt reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 65 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0070-1Modeling of the high flux isotope reactor cycle 400 with KENO-VI

. Trans. Am. Nucl. Soc. 104(1) (2011). https://www.ans.org/pubs/transactions/article-12169/RMC – A Monte Carlo code for reactor core analysis

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 82, 121-129 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2014.08.048Hybrid windowed networks for on-the-fly Doppler broadening in RMC code

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32(6), 62 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00901-2Forced propagation method for Monte Carlo fission source convergence acceleration in the RMC

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00868-0Simulation and experimental study of a random neutron analyzing system with 252Cf neutron source

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 22(1), 39-46 (2011). https://doi.org/10.13538/j.1001-8042/nst.22.39-46The problem of large-scale production of plutonium-238 for autonomous energy sources

. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1689,Fast pulse sampling module for real-time neutron-gamma discrimination

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 84 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0595-1Design studies for the optimization of 238Pu production in NpO2 targets irradiated at the high flux isotope reactor

. Nucl. Technol. 206, 1182-1194 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/00295450.2019.1674594Theoretical analysis of long-lived radioactive waste in pressurized water reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00911-0The authors declare that they have no competing interests.