Introduction

Nuclear reactions play a significant role in energy generation and the synthesis of elements in the universe [1]. H, He, and a small amount of Li were produced by primordial nucleosynthesis in the first few minutes after the Big Bang [2-4]. During the stellar burning phases, elements up to Fe are produced by a series of charged-particle-induced nuclear reactions [5, 6], and their reaction rates are commonly hindered by the small Coulomb barrier tunneling probability at astrophysical energies, which makes direct measurements at the Gamow window extremely challenging [7-10]. The activation method is an alternative approach to measure the cross-section by irradiating the target and determining the number of reaction product nuclei separately [11]. It involves the use of an accelerator mass spectrometer [12] for direct counting or a low background γ spectrometer for the decay γ-rays with a known branching ratio [13]. If the reaction product nuclei are radioactive and have a suitable half-life, the activation method with offline decay γ-ray detection provides a portable solution to avoid the difficulties encountered in online direct measurement.

A γ spectrometer with high detection efficiency and low background is essential for this purpose. A low background can be achieved by active and passive shielding of cosmic and laboratory γ-rays [14, 15]. A well-type HPGe detector has an almost 4π geometry when placing the radioactive sample in the well bottom, thus making it ideal for achieving high detection efficiency and energy resolution simultaneously [16, 17]. This is vital for the upcoming astrophysical reaction measurements of

In this study, a low-background γ spectrometer called the Gamma spectrometer for Nuclear Activation Study (GNAS) was developed with a well-type HPGe detector and optimized multi-layer shielding with elaborately selected materials. A Monte Carlo simulation approach was applied to retrieve the intrinsic detection efficiency and correct for the TCS effect with a 137Cs monoenergetic source and online-produced 55,57,58Co sources. By simulating the HPGe detector response and comparing the simulated decay spectra with those measured from irradiated natural Fe samples, the intrinsic detection efficiency of the GNAS was obtained. An algorithm for the correction of the TCS effect was programmed using decay data from the ENSDF library and Nuclear Wallet Cards.

GNAS description

The GNAS is based on an ORTEC GWL series HPGe well-type detector with a low-background oxygen-free copper endcap and a high-purity aluminum well tube. The active volume of the germanium detector is 349 cm3, with a well 1.55 cm in diameter and 4.0 cm in depth. The detector is equipped with a low-background J-type cryostat and a remote preamplifier. Because it is near the 4π geometry for small radioactive samples, the detector has a high absolute counting efficiency for radiochemical analysis and low-level γ-ray spectroscopy.

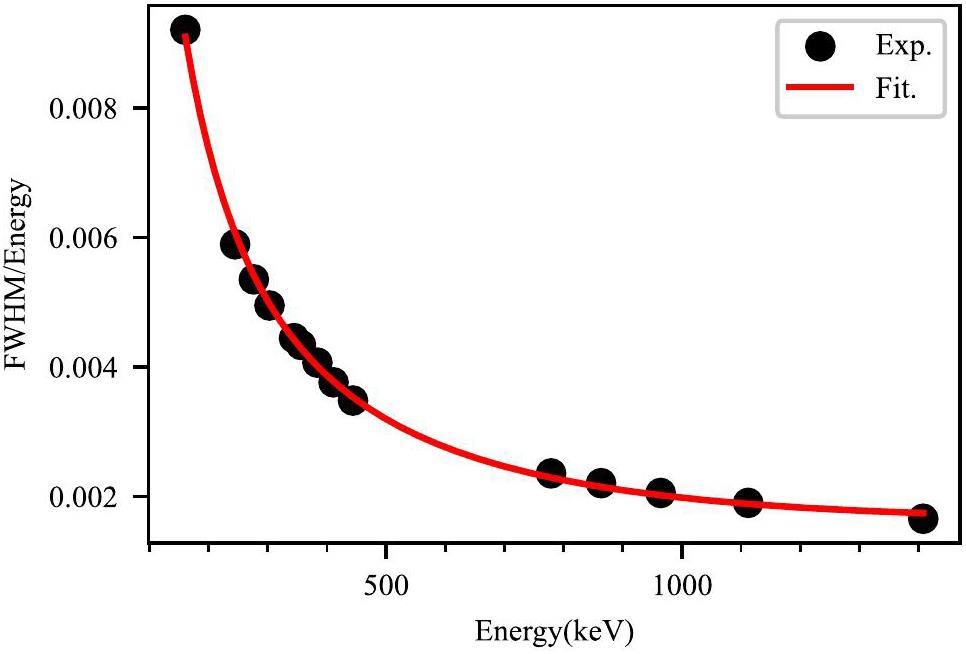

Figure 1 shows the energy resolution curve of the detector, defined as the ratio of the FWHM to γ energy, which was measured using a mixed γ radioactive source of 152Eu and 133Ba. The FWHM of the GNAS at 1408 KeV was 2.33 KeV, which is similar to that of other coaxial p-type HPGe detectors.

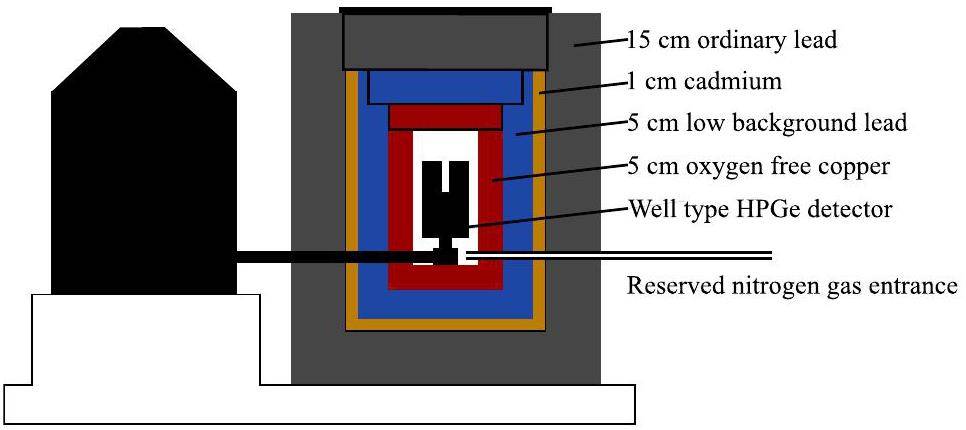

A schematic of the low-background γ spectrometer GNAS is shown in Fig. 2. The germanium detector is set in a chamber with a diameter of 12 cm and a height of 41 cm surrounded by 5 cm-thick high-purity oxygen-free copper. The copper layer is then enclosed by 5 cm-thick low background lead, 1 cm-thick cadmium, and 15 cm-thick ordinary lead. The cadmium layer is used to absorb the thermalized background neutrons [27]. The inner layer of the low-background lead and oxygen-free copper is used to shield the outside and secondary γ radiation from neutron absorption, respectively.

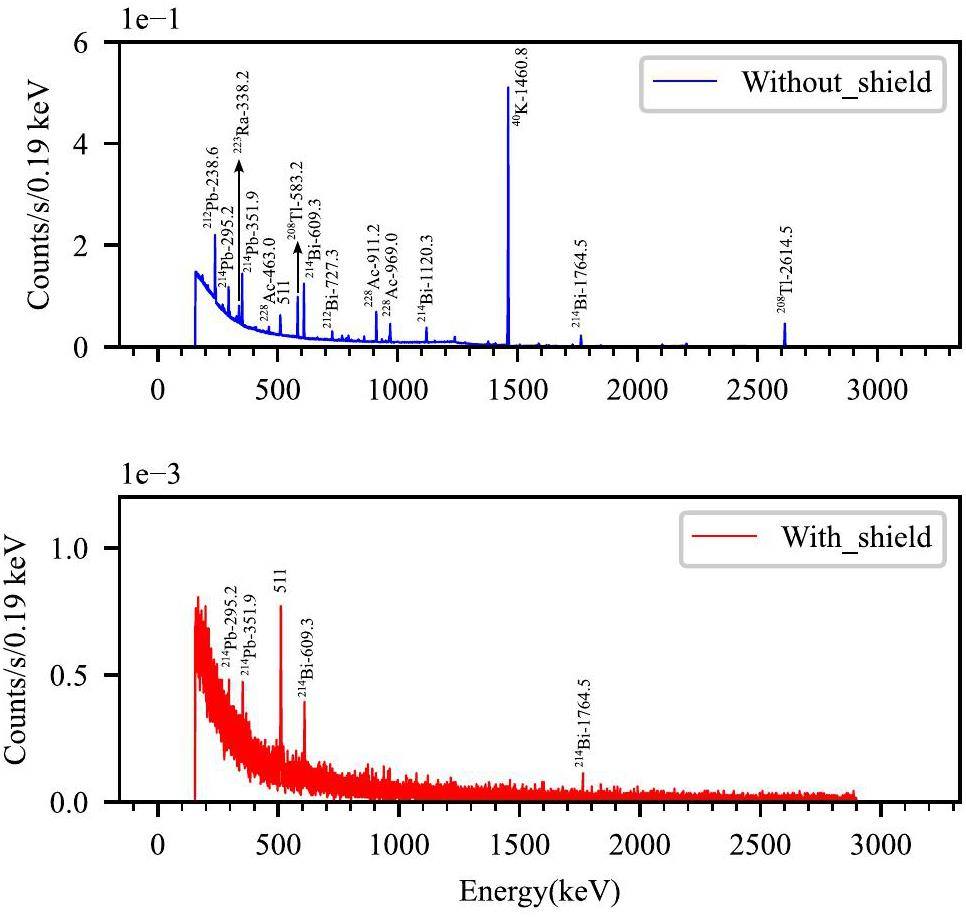

The background γ counting rate spectra with and without shielding are shown in Fig. 3. With the multi-layer shielding structure of the GNAS, its background counting rate in the energy range 195–2910 KeV decreased from 185.74 counts per second (cps) to 0.89 cps, a reduction rate of approximately 99.5%.

To measure offline the decay γ-rays from nuclear activation experiments, the energy range of interest for γ-rays typically does not exceed 3 MeV. In this energy range, the background γ spectrum is highly complex, as shown in Fig. 3. These γ-rays mainly originate from environmental radioactivity, including the natural radioactive series of 238U and 232Th, the single radionuclide 40K, and the background neutron-induced series [28]. With the multi-layer shielding structure of the GNAS, most background γ lines were reduced to an unnoticeable level. The γ lines at 295.2 KeV and 351.9 KeV arose from 214Pb, whereas those at 609.3 KeV and 1764.5 KeV arose from 214Bi, which originated from shielding materials and radon in the air [28-30]. The γ line at 511 KeV originated from the annihilation of positrons produced mainly by the high-energy environmental γ-ray-induced pair production in the germanium crystal.

The peak counting rates of the background γ lines of 214Pb and 214Bi with and without the shielding are listed in Table 1.

| Energy (keV) | Nuclide | Peak counting rate (Day-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With shield | Without shield | ||

| 295.2 | 214Pb | <137 | 40543(898) |

| 351.9 | 214Pb | 178(16) | 74423(845) |

| 511 | β+ | 1010(54) | 44137(759) |

| 609.3 | 214Bi | 131(13) | 83575(668) |

| 1120.3 | 214Bi | <86 | 26673(469) |

| 1764.5 | 214Bi | <36 | 25071(268) |

It is planned that the GNAS will be used at JUNA for activation experiments; therefore, it will be necessary to introduce nitrogen gas into the HPGe detector room to remove the natural radon background.

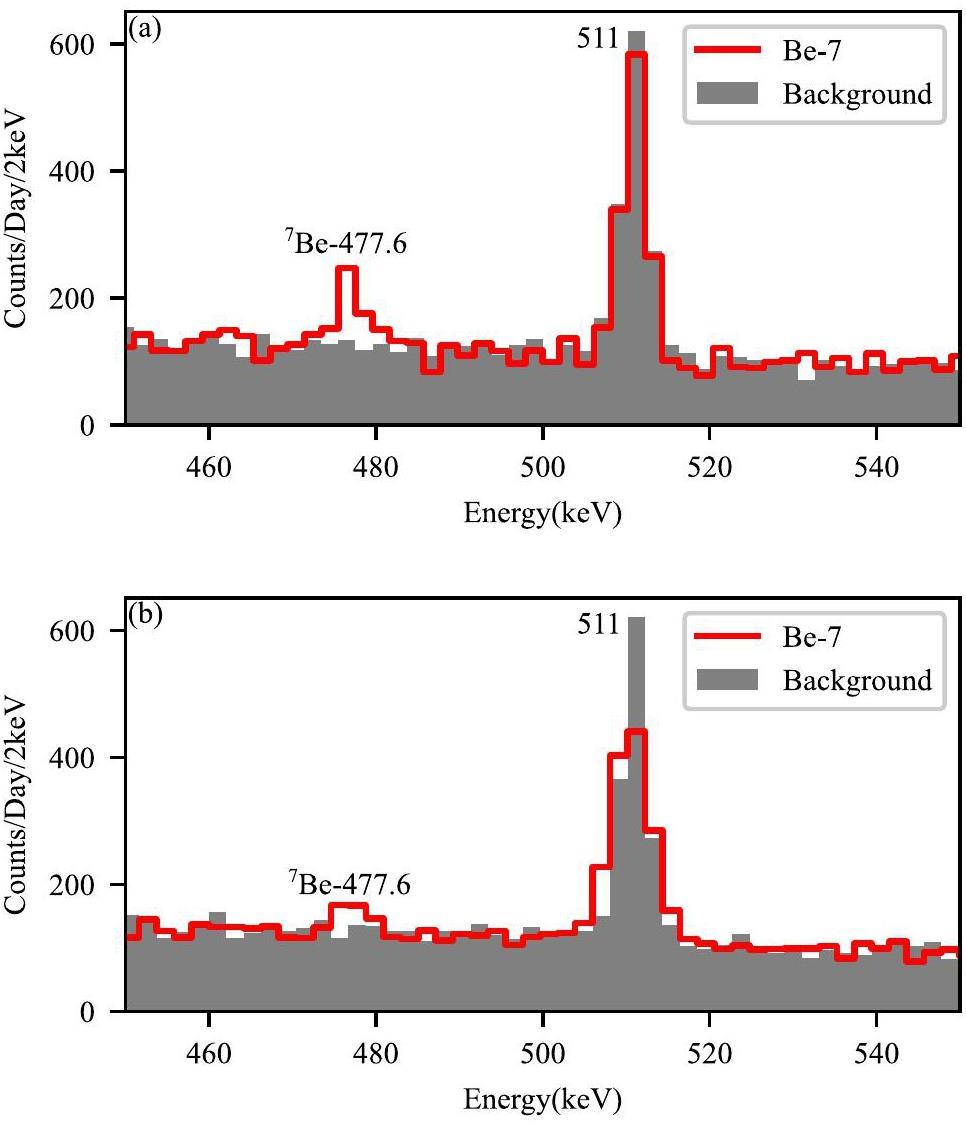

The significant decrease in the background and the blind well design of HPGe enhanced the sensitivity of the GNAS. Several low-activity 7Be samples were prepared using the

The counting rate of 477.6 keV γ-rays is 199(39) counts per day (cpd) in Fig. 4 and 94(47) cpd in Fig. 4b. For a sample with an activity as low as 0.044 Bq, which is less than 4.5 × 10-3 s-1 out of the emission rate of 477.6 KeV γ rays, the GNAS was still capable of distinguishing and evaluating its statistics, as shown in Fig. 4b.

True coincidence summing

The intrinsic FEP efficiency of a γ spectrometer is typically calculated using Eq. (1) and standard γ sources with known activities and γ branching ratios,

For two cascade γ-rays, there are three types of TCS: (1) both γ-rays deposit their full energies in the active volume of the HPGe detector; (2) one γ-ray deposits its full energy, whereas the other deposits only part of its energy; and (3) both γ-rays deposit only part of their energies. The first two types of summing events can significantly deflect the FEP statistics in the γ spectrum, which is represented by N(E) in Eq. (1). The third type of summing event contributes only to the Compton plateau in the spectrum, which is not directly attributed to the statistics of the FEPs.

Correction for TCS

Numerical methods have been developed to correct for TCS effects in γ-ray spectroscopy [32-35]. In recent years, Monte Carlo simulations have been intensively used to determine the detection efficiency and TCS correction of various customized γ spectrometers [36-39]. The ideal method for determining the intrinsic FEP efficiency of the GNAS is through a set of weak monoenergetic γ-ray sources [40-42], which in turn helps to determine the dimensional parameters of the HPGe detector for the simulation. For this purpose, a right-sized 137Cs source with an activity of only 601 Bq was fabricated. Because we did not have other weak monoenergetic γ-ray sources, several natural Fe targets were irradiated using a 4 MeV proton beam from the HI-13 tandem accelerator, and the activities of 55Co, 57Co, and 58Co were subsequently calibrated using a standard γ spectrometer [43]. Based on these γ sources, we developed a Monte Carlo simulation method using the Geant4 toolkit.

The primary task of the simulation was to determine the dimensional parameters of the well-type HPGe detector, with which the intrinsic FEP efficiency εinc could be directly simulated at the user-set γ-ray energies. The next step was to simulate real radioactive decay to correct the TCS effect numerically.

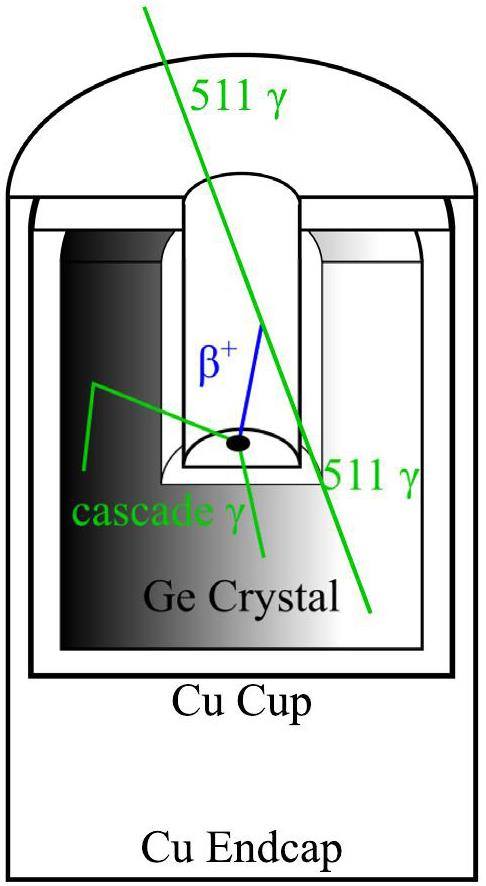

With Geant4, decay data can be generated from the G4RadioactiveDecayPhysics module based on the ENSDF library and Nuclear Wallet Cards. The G4EmLowEPPhysics package is used to describe low-energy polarized X/γ-ray transport [44]. A 55Co decay event at the bottom of the well and its interactions with the germanium crystal are schematically shown in Fig. 5. The emitted positron annihilated into two 511 keV γ-rays, whereas the 55Fe daughter nucleus deexcited by single or cascaded γ lines. The energy deposited in the detector by each decay was treated as a single signal; therefore, these γ-rays may partly or totally sum into a single γ line.

The HPGe dimensions provided by the manufacturer were optimized [40, 45] to reproduce the known activities of the 55,57,58Co spectrum, as listed in Table 2.

| Detector parameters | Manufacturer | Optimized |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal diameter | 79.3 mm | 79.3 mm |

| Crystal length | 77 mm | 79.5 mm |

| Dead layer thickness | 0.3 μm | 0.6 μm |

| Endcap thickness | - | 0.8 mm |

| Endcap-to-crystal distance | - | 10.3 mm |

| Well tube thickness | 1 mm | 0.65 mm |

| Well tube inner diameter | 15.5 mm | 15.5 mm |

| Well tube active depth | 40 mm | 40 mm |

| Coaxial hole diameter | - | 33.34 mm |

| Coaxial hole depth | - | 50 mm |

The dead layer and well tube thicknesses were found to significantly affect the efficiency in the low-energy region because of the absorption of γ lines. The dimensions of the crystals also affected the efficiency, owing to the solid angle and crystal thickness difference.

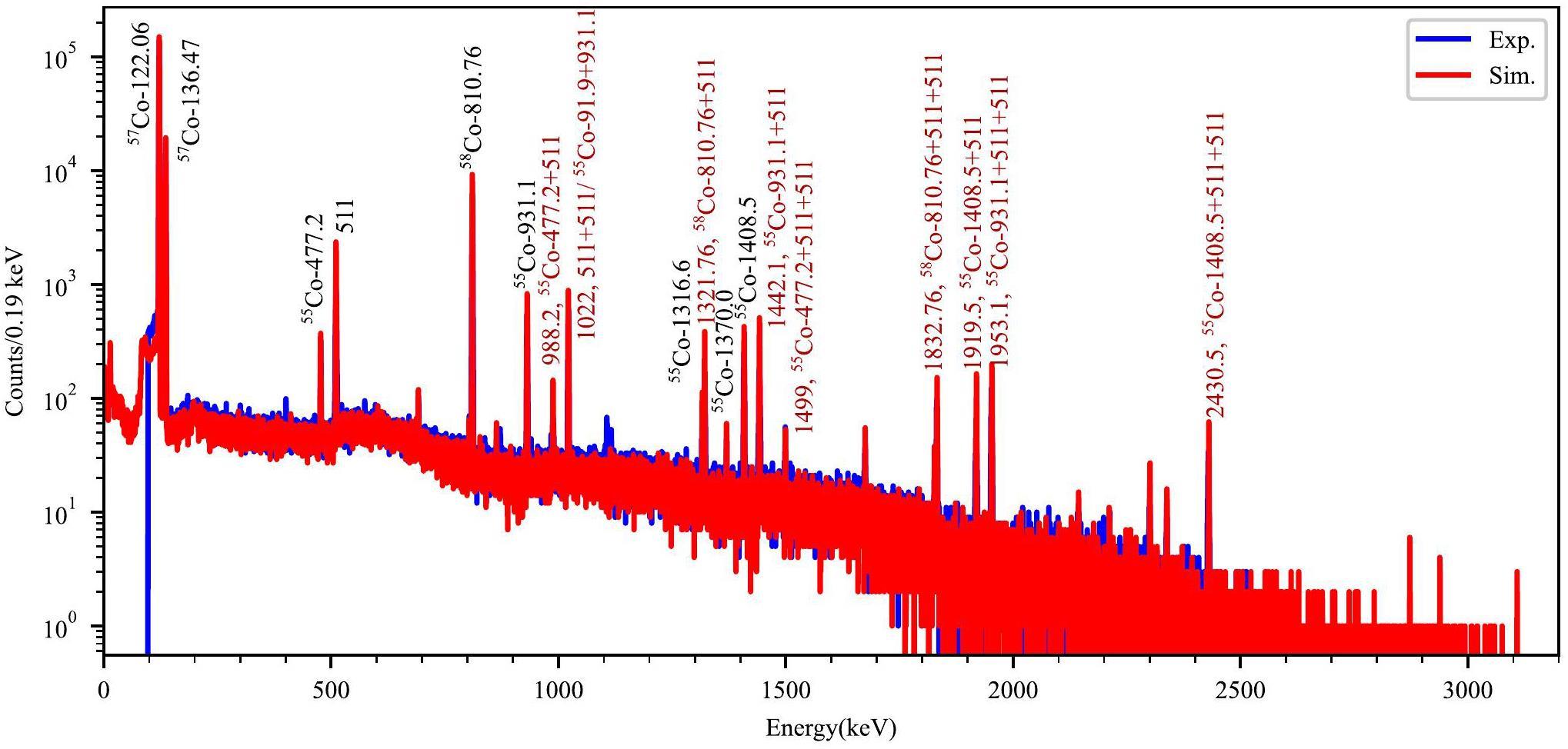

The dead layer and well tube thicknesses were preliminarily optimized to constrain the deviation between the simulated and experimental 137Cs statistics to within 10%. Subsequently, most parameters were varied in small steps and eventually constrained by the experimental spectra of the 55,57,58Co source to obtain the optimized values. For example, the simulated γ spectrum containing the calibrated 55,57,58Co activities was compared with the measured spectrum, as shown in Fig. 6. All FEPs and summing peaks were accurately reproduced in the simulation. For instance, the 1321.76 keV and 1832.76 keV γ-ray peaks, which were the summing peaks of 810.76 keV and one or two 511 keV γ-rays from 58Co, were well reproduced.

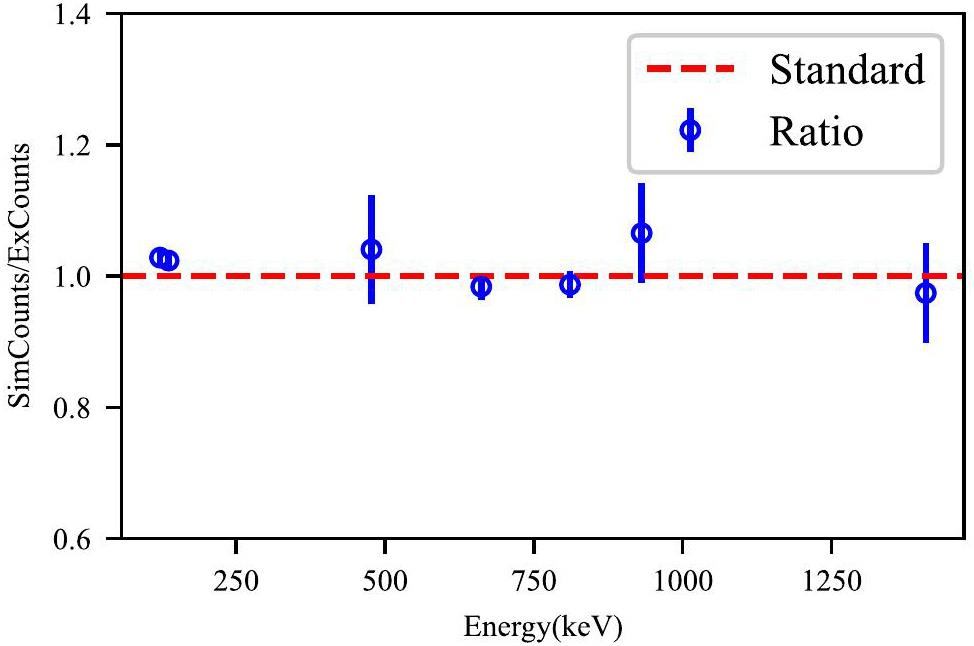

To evaluate the simulation uncertainty of the detector parameter optimization, the ratios of the simulated and experimental γ FEP areas for the 137Cs and 55,57,58Co sources are shown in Fig. 7. Most of the simulated FEP areas agreed with the experimental areas within a 5% margin of error. The γ lines with large deviations were mainly due to weak activities and uncertainties in the calibrated activity value. To reduce the uncertainty, a 65Zn (

Intrinsic efficiency and TCS correction factor

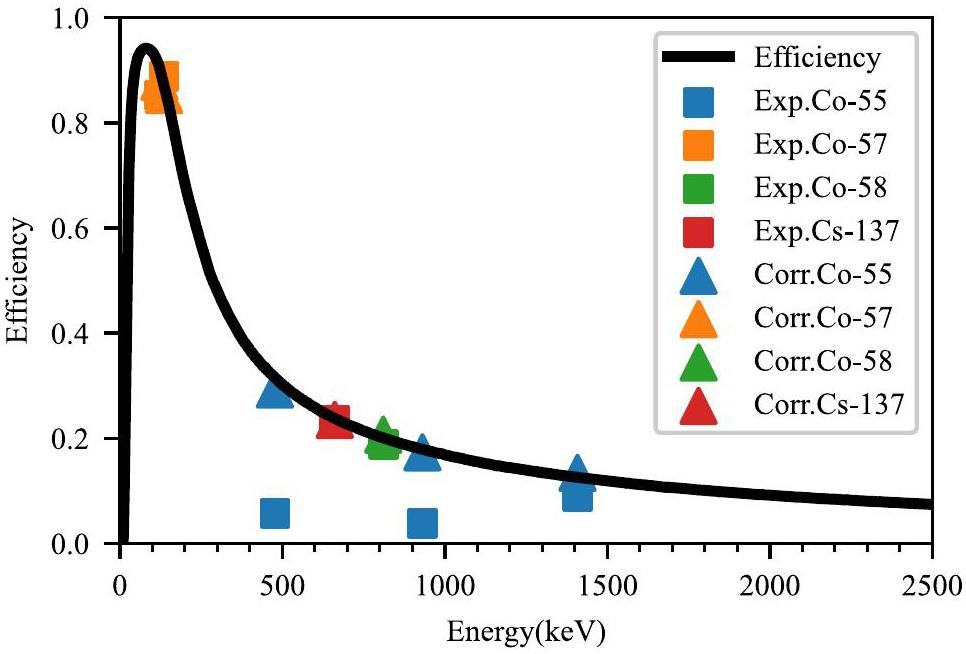

Using the optimized detector model, we calculated the intrinsic FEP efficiency of the GNAS using different energy steps of Geant4 simulations. The resulting efficiency curve is presented in Fig. 8. To illustrate the impact of TCS, the specific energy points from 137Cs and 55,57,58Co are marked. These points represent the efficiencies obtained directly from the measured FEP statistics according to Eq. 1 with and without correction for the TCS effect.

If we define a TCS correction factor as the ratio of the intrinsic FEP efficiency εinc to that without correcting for TCS εnc,

Detailed data are presented in Table 3, which lists the measured and simulated uncorrected FEP efficiencies as well as the TCS correction factor and intrinsic FEP efficiencies after TCS corrections. For certain γ-ray peaks, such as the 477.2 keV and 931.1 keV lines from 55Co, the TCS effect was particularly pronounced because of the cascade γ decay and high efficiency of the detector.

| Nuclide | Eγ (keV) | εexp | εsim | FTCS | εinc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 137Cs | 661.6 | 0.235(1) | 0.235(1) | 1 | 0.235(1) |

| 55Co | 477.2 | 0.057(3) | 0.061(6) | 5.1(5) | 0.3153(6) |

| 931.1 | 0.039(2) | 0.039(4) | 4.5(5) | 0.1788(4) | |

| 1408.5 | 0.089(5) | 0.083(8) | 1.5(1) | 0.1260(4) | |

| 57Co | 122.1 | 0.852(10) | 0.879(16) | 1.03(2) | 0.9063(10) |

| 136.5 | 0.889(11) | 0.913(17) | 0.96(2) | 0.8745(9) | |

| 58Co | 810.8 | 0.188(3) | 0.182(5) | 1.10(3) | 0.2007(4) |

For activation measurements in nuclear astrophysics at JUNA, when the produced radioactive nuclei decay through cascade γ-rays, TCS evidently deflects the real FEP statistics. With the newly developed Monte Carlo method, one can simulate the TCS correction factor by simply changing the decay nucleus together with the well-determined intrinsic detection efficiency curve of the GNAS.

Summary

A low-background γ spectrometer (GNAS) was installed for activation measurements within nuclear astrophysics. Using a multi-layer shielding structure, a background reduction of 99.5% was achieved, which enabled the detection edge of a low activity of 10-2 Bq with a high-efficiency well-type HPGe. A Monte Carlo simulation approach using Geant4 was developed to address the TCS effect. The optimized detector model ensured a good agreement between the simulated and experimental spectra. The intrinsic efficiency curve was determined, and the algorithm for TCS correction was programed using decay data from the ENSDF library and Nuclear Wallet Cards. The GNAS fulfills the requirements of the ongoing activation measurement of proton- and alpha-induced reactions in nuclear astrophysics on the ground and at the JUNA facility.

Synthesis of the elements in stars

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 29, 547-650 (1957). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.29.547Galactic abundance gradients and implications for nucleosynthesis

. Nucl. Phys. A 688, 411-413 (2001). Nuclei in the Cosmos. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)00740-0On the origin of the light elements (Z<6)

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 193-216 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.66.193Big bang nucleosynthesis: Present status

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88,Measurements of stellar and explosive nuclear astrophysics reactions

. Chinese Phys. C 32, 59-63 (2008).Thermonuclear astrophysics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 46, 755-771 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.46.755Experimental challenges in low-energy nuclear astrophysics

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1078,Novel thick-target inverse kinematics method for the astrophysical 12C+12C fusion reaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 208 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01573-4Direct measurement of the break-out 19F(p,γ)20Ne reaction in the china jinping underground laboratory (CJPL)

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01531-0Measurement of 19F(p,γ)20Ne reaction suggests CNO breakout in first stars

. Nature 610, 656-660 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05230-xThe activation method for cross section measurements in nuclear astrophysics

. Eur. Phys. J. A 55, 41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12708-412Stepped-up development of accelerator mass spectrometry method for the detection of 60Fe with the HI-13 tandem accelerator

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 77 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01453-xCross sections for proton-induced reactions on Pd isotopes at energies relevant for the γprocess

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Design of cosmic veto shielding for HPGe-detector spectrometer

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 109, 474-478 (2016). Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Radionuclide Metrology and its Applications 8-11 June 2015, Vienna, Austria. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2015.11.065Background radiation reduction for a high-resolution gamma-ray spectrometer used for environmental radioactivity measurements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 715, 112-118 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2013.03.024Response functions of a 4πsumming gamma detector in β-oslo method

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 68 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01058-2Improvement of accuracy of efficiency extrapolation method in 4πβ−γ coincidence counting

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 369, 383-387 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(96)80014-3The controversy 3/2+ state in 7Be and its effect on the 3He(α,γ)7Be reaction

. Nucl. Phys. A 1022,Recent progress in nuclear astrophysics research and its astrophysical implications at the china institute of atomic energy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 217 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01590-3First results from the underground nuclear reaction experiments in juna

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40,. https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/40/6/060401Underground laboratory juna shedding light on stellar nucleosynthesis

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 42 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01196-1Progress of underground nuclear astrophysics experiment juna in china

. Few-Body Syst. 63, 43 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00601-022-01735-3Preparation of large-area isotopic magnesium targets for the 25Mg(p,γ)26Al experiment at juna

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00800-yProgress of jinping underground laboratory for nuclear astrophysics (juna)

. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 59,Empirical relation between efficiency and volume of HPGe detectors

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 262, 439-440 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(87)90885-0Coincidence summing corrections in Ge(Li)-spectrometry at low source-to-detector distances

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 158, 471-477 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-554X(79)94845-6Spallation yield of neutrons produced in thick lead target bombarded with 250 MeV protons

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 342, 87-90 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2014.09.020The characteristics of a low background germanium gamma ray spectrometer at China JinPing underground laboratory

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 91, 165-170 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2014.05.022A novel method for simultaneous measurement of 222Rn and 220Rn progeny concentrations measured by an alpha spectrometer

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01570-7Experimental investigation on the radiation background inside body counters

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 20 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01004-2The large-scale modular BGO detection array (LAMBDA) design and test

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 207 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01574-3Coincidence summing in gamma-ray spectroscopy

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 290, 437-444 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(90)90561-JNumerical expressions for the computation of coincidence-summing correction factors in γ-ray spectrometry with HPGe detectors

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 68, 555-560 (2010). The 7th International Topical Meeting on Industrial Radiation and Radio isotope Measurement Application(IRRMA-7). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.10.024Calculation of true coincidence summing corrections for extended sources with efftran

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 69, 908-911 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.02.042Hybrid analytical method for calibrating a standard NaI(Tl) gamma-ray scintillation detector using a lateral hexagonal radioactive source

. AIP Adv. 12,The large-scale modular bgo detection array (lambda) design and test

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 207 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01574-3Summing coincidence correction for γ-ray measurements using the HPGe detector with a low background shielding system

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 880, 22-27 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.09.043True coincidence summing corrections in point and extended sources

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 289, 773-780 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-011-1126-7Monte carlo calculation of the efficiency calibration curve and coincidence-summing corrections in low-level gamma-ray spectrometry using well-type HPGe detectors

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 53, 57-62 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-8043(00)00114-7True coincidence summing correction for a BEGe detector in close geometry measurements

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 200,Calculation of coincidence summing correction factors for an HPGe detector using GEANT4

. J. Environ. Radioactiv. 158-159, 114-118 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvrad.2016.04.008Simulation approach to coincidence summing in γ-ray spectrometry

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 70, 1141-1144 (2012). Proceedings of the 8th International Topical Meeting on Industrial Radiation and Radioisotope Measurement Applications (IRRMA-8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.09.014Experimental study on background reduction ofγ-ray spectrometer using anticoincidence and thermal neutron shielding methods

. Nuclear Techniques 33, 501-505 (2010). https://www.hjs.sinap.ac.cn/zh/article/7235199/Recent developments in geant4

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 835, 186-225 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.06.125Coincidence summing corrections for a clover detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 763, 240-247 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.06.043The authors declare that they have no competing interests.