Introduction

Superheavy elements with an atomic number Z higher than 103 follow the actinide series in the periodic table. Investigations of these elements are crucial in the field of nuclear physics and chemistry [1], e.g., to elucidate the influence of relativistic effects on their chemical properties. Due to the low production rates and short nuclear lifetimes of superheavy elements, our knowledge of their properties is limited. Nonetheless, the quest for discovery and understanding of these elusive elements remains a fascinating and challenging area of current research [2]. However, the inability of existing chemistry-setups to efficiently capture and study shorter-lived isotopes limits further progress in SHE research. Addressing this bottleneck is essential for advancing our understanding of SHE chemistry and physics. In typical SHE study setups, the products of complete fusion reactions are either directly implanted into a detector installed at the focal plane of a physical recoil separator (see, e.g., [3] for a current setup at the TASCA separator at GSI) for radioactive decay measurements or are extracted through a vacuum window into a gas stopping cell, where they are decelerated in a series of collisions with the buffer gas atoms. There are two main classes of such setups: Buffer Gas Cells (BGC) [4] and Recoil Transfer Chambers (RTC) [5], differentiated by the presence or absence of guiding electrical fields.

Chemical studies of superheavy elements [6] often probe the interaction strength of a single atom or molecule with a solid, ideally well-defined surface. To meet strict efficiency requirements, detector arrays like the Cryo-Online Multidetector for Physics and Chemistry of Transactinides (COMPACT) [7, 8] have been developed. These arrays feature detector diodes coated with materials such as gold or silicon dioxide. Two detector arrays are connected together to form a gas-tight enclosure, which is at the same time a chromatography channel for introducing superheavy elements with a carrier gas. For chemical studies, a relatively fast and efficient stopping and extraction of energetic residues from heavy-ion fusion reactions into the aforementioned chemistry setup was typically achieved using RTCs, which rely solely on gas flow extraction. RTCs have been widely used in experiments with elements up to 114Fl [9] and provide high efficiency for chemically non-reactive volatile species [10]. However, it usually takes almost one second to extract 50% of the recoils, even in advanced RTCs [11]. This extraction time significantly exceeds the half-lives [12] of all known isotopes of elements beyond 115Mc and also of the most accessible Mc isotope, 288Mc, and thus prohibits their efficient chemical study. Decades ago, the Ion-Guide Isotope Separation On-Line (IGISOL) technique demonstrated that the swift transport of ions of any element can be achieved by preserving the recoil ion charge and manipulating it with electric fields [13, 14]. A variety of BGCs have since been developed [15] to enable fast and efficient extraction of ions. Different kinds of BGCs find many applications for the thermalization of fast multi-charged ions and their extraction as secondary ion beams [16-21], as well as for studies of the heaviest elements [22-24]. First on-line chemistry studies with accelerator-produced radionuclides extracted from a BGC have recently demonstrated the feasibility of this approach [25]. The achieved extraction time of 55(4) ms would be fast enough for efficient studies of 115Mc, 116Lv, and 117Ts with currently known isotopes. For each of these elements, at least one isotope with a half-life of at least around 50 ms is known. In offline studies, the extraction efficiency was 35(3)% [26] due to the rather low maximum gas pressure of this BGC, which provided insufficient stopping power to thermalize ions across the whole kinetic energy range behind the entrance vacuum window. To overcome the limited stopping power and provide even faster extraction times, a novel concept of high-pressure Universal high-density gas stopping Cell (UniCell) was proposed by Varentsov and Yakushev in Ref. [27]. Therein, initial simulation studies suggested that extraction times as short as 2 ms could be achieved. The article also included a concept of an interface (RF-ejector) to guide ions emerging from UniCell to a downstream COMPACT detection setup at ambient pressure by means of an electric field. However, computational simulations of the RF-ejector have not yet been reported.

In this paper, we expand on the previous work. Besides further detailed optimizations on UniCell, we explored solutions, complementary to the RF-driven ejector interface, which might electromagnetically interfere with the detector setup. Notably, we suggest the Ion Transfer by Gas Flow (ITGF) device. Its carefully designed geometry prevents ions, even in the absence of electric fields, from encountering the wall and aims at unity efficiency while retaining fast extraction time. Together with the optimized UniCell, this approach represents a significant step toward overcoming the current limitations in SHE research. In Sect. 2, we present gas-dynamic and Monte-Carlo ion trajectory simulations to optimize the UniCell setup for efficient ion extraction and define the source of ions for the subsequent ITGF simulations, which are provided in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, conclusions and an outlook are given.

UniCell

UniCell setup

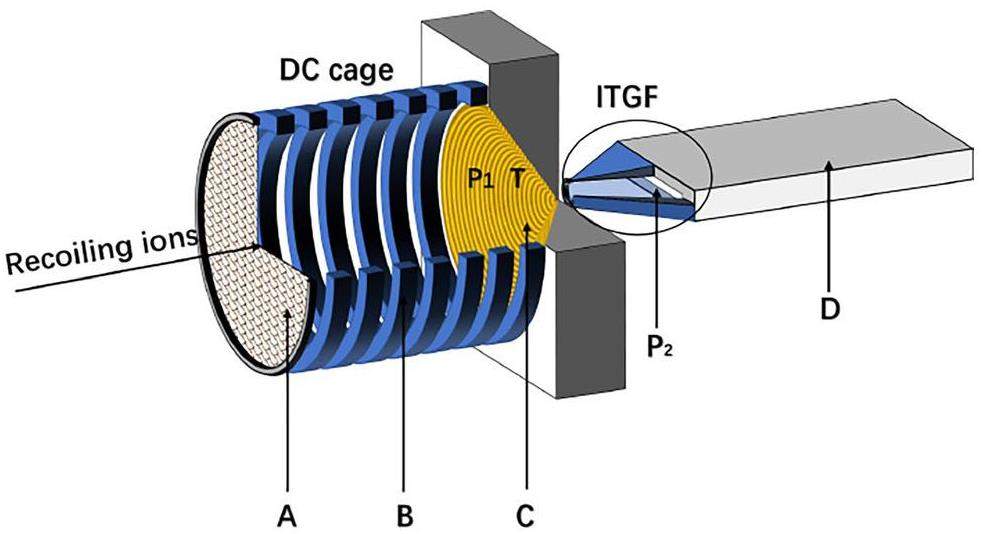

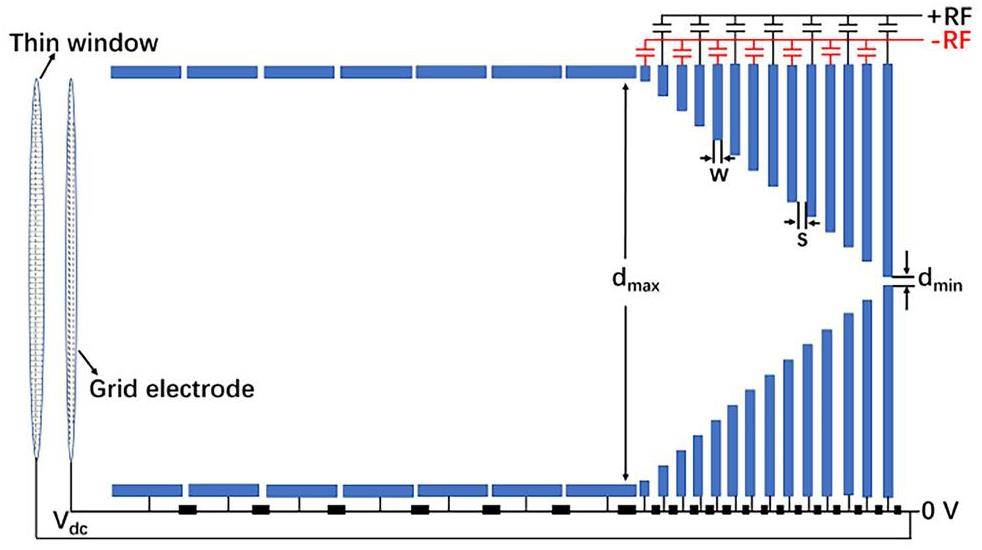

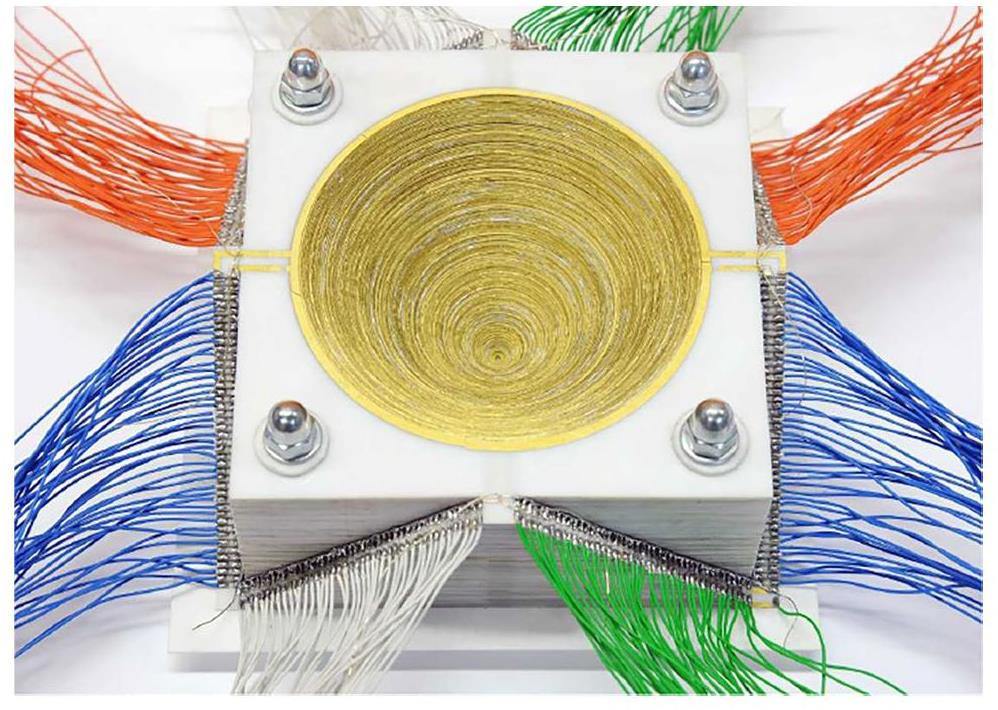

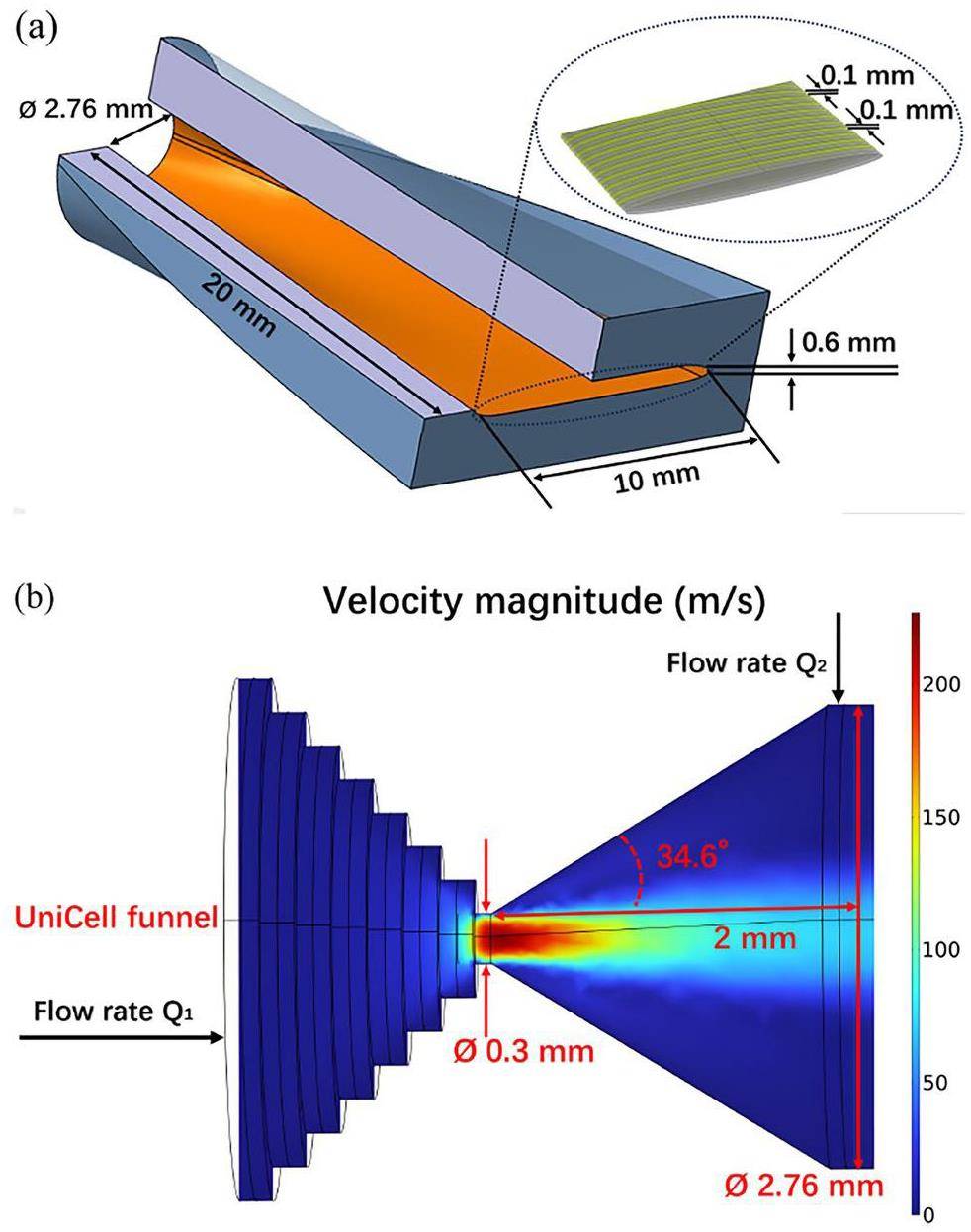

The UniCell setup and working principle were first presented in Ref. [27]. For the convenience of the reader, a brief summary is provided within this section, along with the implemented modifications and the geometry used in simulations. An overview of the setup is sketched in Fig. 1. The main components of UniCell include a direct current (DC) cage and an atmospheric pressure ion funnel, to which a DC gradient and a specific radio-frequency (RF) signal at first appearance are applied. The sophisticated ion funnel, which poses the biggest engineering challenge, has meanwhile been built and undergoes electrical testing. The remainder of the setup is under construction. Energetic ions enter the DC cage through a vacuum window and are thermalized in helium gas at ambient temperature and pressure. The DC gradient guides the ions through the DC cage and funnel. Subsequently, they enter the ITGF and reach the defined COMPACT detector. The DC cage consists of 7 cylindrical electrodes, each with a length of 8 mm and an inner radius of 35 mm. Considering the distance between neighboring ring electrodes of 2 mm, the total length of the DC cage is 70 mm. The ion funnel was fabricated from 352 stacked zirconia sheets with a thickness of w = s = 0.1 mm (see Fig. 2) each. On every second plate, a 10 μm-thick gold ring, produced by the sintering of gold nanoparticles and surrounding the circular opening in the center, serves as an electrode. The intermediate zirconia sheets ensure electrical insulation. A circular cut-out in the center gradually decreases from a maximum diameter of dmax = 70 mm to a minimum of dmin = 0.3 mm. The thin window is mounted on a supporting grid and connected to the ground. The potential of the grid electrode behind the window (see Fig. 2) is the same as that of the first electrode in the DC cage; both are set to a high voltage (e.g., Vdc = 1010.5 V) for the case when the DC gradient is equal to 100 V cm-1. The schematic of the electronic layout and of the supply of the cage and the funnel by DC and RF power are shown in Fig. 2.

To prevent ions from striking the funnel surface, a 180° phase-shifted RF signal is applied between adjacent electrodes. The resulting electric force FRF [15] in the vicinity of the electrodes repels ions and is given by

Ion stopping range

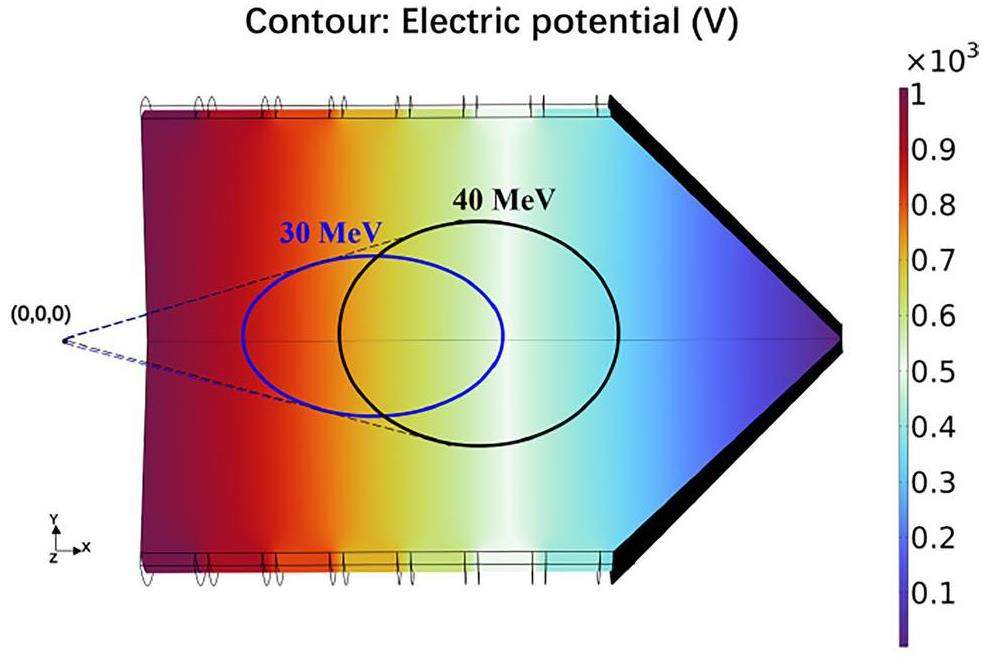

Ions are thermalized by collisions with the buffer gas within the DC cage after travelling through a thin window. SRIM [28] was used to estimate their stopping range. In this work, we estimated the stopping range of the ions of 293Lv and 293Ts; their kinetic energy after production by the 48Ca-induced fusion reactions [29] and their separation in a gas-filled recoil separator ranges between 30 MeV and 40 MeV. In simulations with SRIM, the atomic number is limited to 92 (i.e., uranium). To assess the range of the heavier ions of interest, we used uranium with a mass of 293 in the SRIM simulation and applied the energy conversion outlined in Ref. [30]. The window material was selected to be Mylar with a thickness of 3.5 μm. Reference [31] shows an estimation of the ion stopping range simulated by SRIM. Within this work, the primary focus is on the effectiveness of the DC cage’s longitudinal length in stopping recoil ions. Ions from the TASCA separator have the highest probability to originate from the central axis, while the exact radial image size depends on the separator settings. Therefore, the ion stopping range simulations are based on all ions emerging from a point source (coordinate zero, cf. Fig. 4). In our case, simulations for 30 - 40 MeV ions traveling through a thin window predict stopping within the DC cage, with their final depth distribution also following a Gaussian shape. Through simulations, for 30 MeV ions, the ions’ longitudinal (x-axis) stopping range within 5σ (standard deviation) is calculated to be between +8.75 mm and +34.35 mm, and the lateral projected range along the y-axis is between -9.81 mm and +9.69 mm, as illustrated in Fig. 4 (blue circle). For 40 MeV ions, the ions’ longitudinal (x-axis) stopping range within 5σ is in the range from +21.45 mm to +46.35 mm, and the lateral range along the y-axis is in the range from -10.82 mm to +10.98 mm, as shown in Fig. 4 (black circle). The simulation results confirm that the envisaged length of the DC cage (70 mm) is expected to be sufficient to thermalize all ions of interest.

Extraction efficiency for UniCell

COMSOL Multiphysics version 6.1 [32] is a commercial finite element package that allows users to build complex models in an advanced graphical user interface. Further advantages of COMSOL are its ability to couple different physical effects in the same model and the comprehensive built-in library of meshing tools, numerical solvers and post-processing tools. It includes the AC/DC Module and the Particle Tracing Module, where the “Electrostatics” and “Laminar Flow” interfaces are used to evaluate the electric potential distribution and gas dynamics within the UniCell. The electrical potential distribution obtained in our simulation is shown in Fig. 4. For the average DC field strength of 100 V cm-1, the potential difference between adjacent electrodes was 100 V in the DC cage and 2 V in the funnel. At a mean flow rate of 10 mbar L s-1, the maximum gas flow velocity, which occurs near the nozzle, was calculated to be about 227 m/s. As will be discussed in the following Sect. 3, the gas flow velocity in other locations in UniCell is negligible compared to the ion velocity resulting from electric forces. Thus, the simulation is based on the precondition that the buffer gas within the UniCell volume is considered stationary.

The trajectory simulation of ions with 40 MeV initial energy moving in the DC + RF field was performed using SIMION 8.2.0.11 [33], where the final positions obtained from the SRIM simulation were used as the initial positions for SIMION simulations. The size of the grid elements used in our model is 0.01 mm, which is sufficiently small for the electrodes. The following parameters were commonly used for all simulations: helium gas pressure P1=1 bar, gas cell temperature T=300 K, ion mass M=293 u, and RF frequency f = 5 MHz. The mutual Coulomb repulsion among ions is neglected due to the low production rate of superheavy elements and byproducts entering UniCell, which leads to negligible ion density. The statistical diffusion simulation (SDS) model was used to efficiently simulate the high-pressure atmosphere. The SDS model utilizes a combination of a viscous Stokes’ law drag force and a superimposed diffusion effect [34]. The reduced ion mobility in helium was assumed to be K0=17.37 cm2V-1s-1 [35].

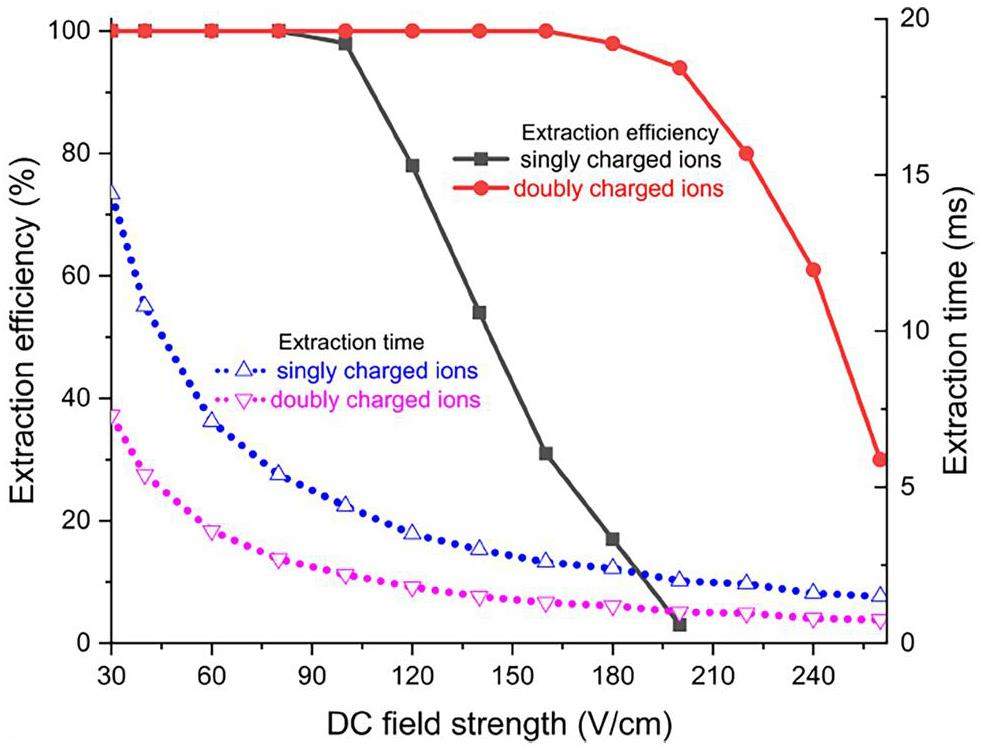

Simulations were performed within a range of the DC field strengths between 30 V cm-1 and 260 V cm-1. Ions are typically extracted from BGCs in a charge state of 1+ or 2+ [36]. In each simulation, the trajectories of 100 ions were calculated after convergence studies. It was found that beyond the number of 100 simulated ions, a further increase in ion number does not significantly affect the averaged simulation observables. The fractions of all ions injected into the UniCell and the ITGF, passing through the device without wall encounters and emerging from its outlet, are given as extraction efficiency. The detailed ion trajectories are shown in Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material. As shown in Fig. 5, when the RF voltage Vpp = 200 V, the extraction time gradually decreases with increasing DC field strength. While a short extraction time is desired, ion losses occur at elevated fields above ≈ 100 V cm-1. However, quantitative extraction is predicted to be independent of the ion charge state at lower field strengths. If a charge state higher than 1+ can be retained, field strengths up to ≈ 200 V cm-1 can be applied without significant loss. At the optimum DC field strength of 100 V cm-1, the corresponding mean extraction times of singly and doubly charged ions are 4.4 ms and 2.2 ms, respectively. The difference in extraction efficiency between singly and doubly charged ions, as shown in Fig. 5, can be attributed to the difference in the force exerted by the electric field. In particular, the RF-Force FRF (Eq. (1)), preventing ions from striking the electrodes, scales quadratically with the ion charge. Thus, high extraction efficiencies for doubly charged ions can be achieved even at an elevated DC field strength and resulting higher ion velocities.

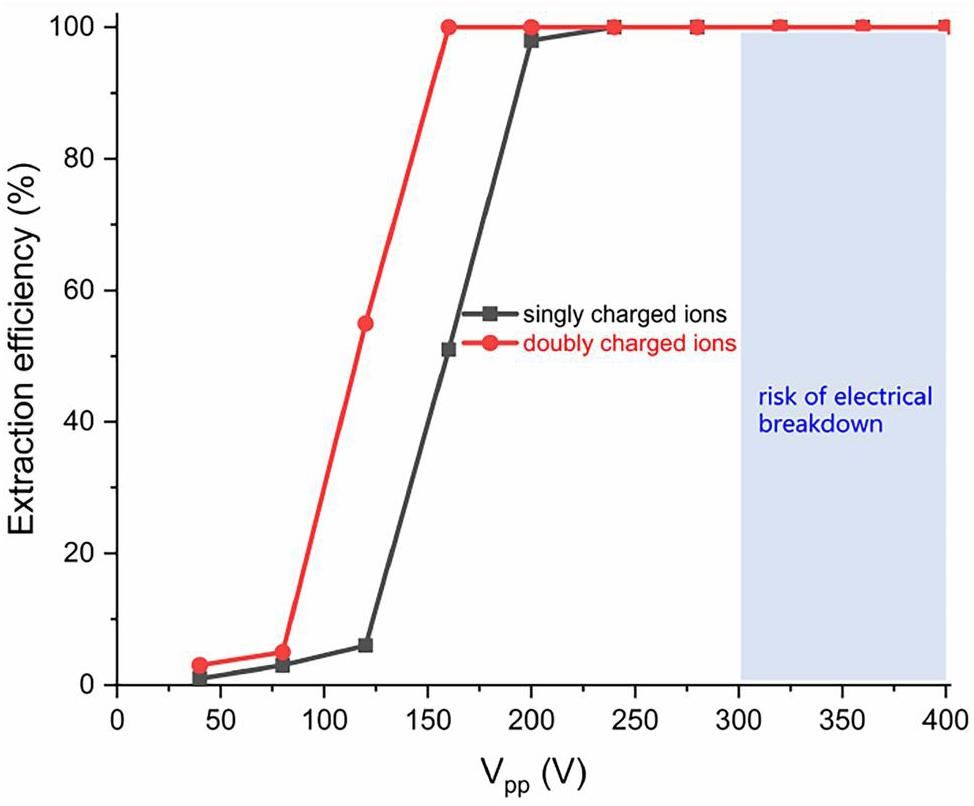

Figure 6 indicates that the extraction efficiency also depends on Vpp. When the DC field strength E=100 V cm-1, the extraction efficiency increases with Vpp. Values of at least Vpp≈200 V result in a predicted extraction efficiency of ≈100% for singly charged ions, while the threshold Vpp is 160 V for doubly charged ions. We note here that the breakdown voltage between the neighboring electrodes has to be taken into account. The breakdown voltage for the UniCell funnel at the above-mentioned conditions should be higher than 300 V, which is the value of the breakdown voltage found for a gap distance of 0.13 mm, an RF frequency of 13 MHz, and a pressure of ≈ 1 bar [37]. As the breakdown voltage is expected to increase with decreasing frequency [38, 39], the desired voltage of Vpp = 200 V to reach quantitative extraction at our design frequency of 5 MHz is expected to be within a range that allows stable operation.

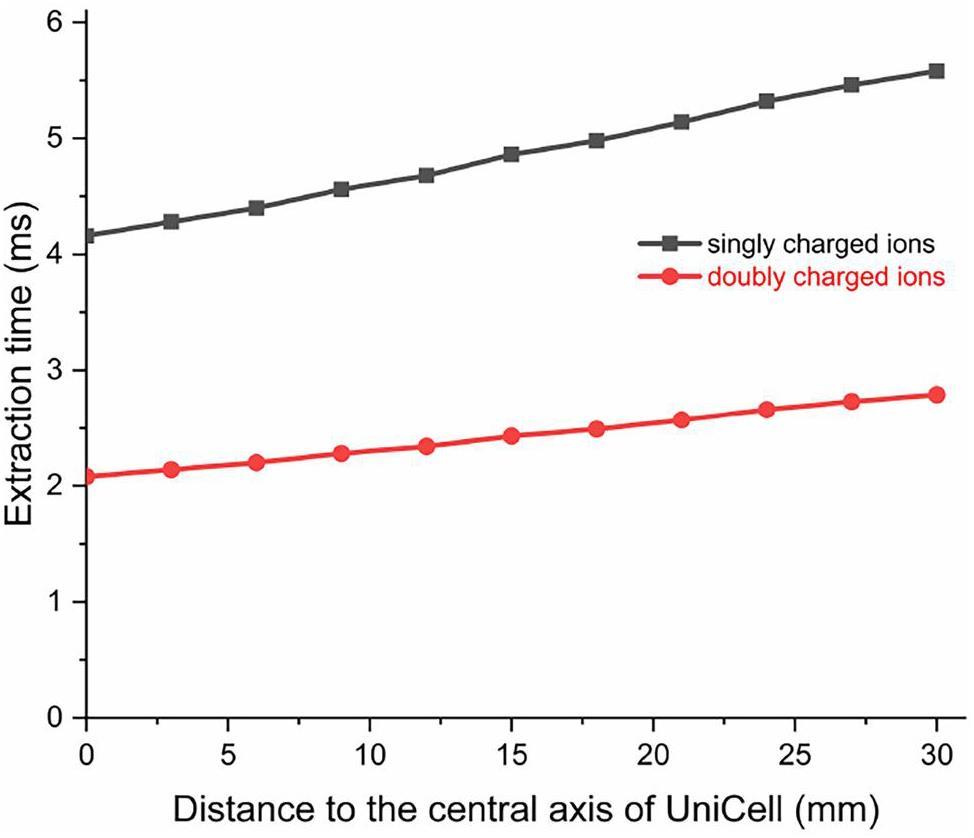

The trajectory analysis resulted in the extraction time distribution as a function of the radial stopping position given in Fig. 7 for the thermalized ions inside the DC cage. Extraction times between 2 ms and 6 ms were obtained. As expected, the flight times for thermalized singly charged ions are almost twice as long as those for doubly charged ions. When the initial positions of the thermalized ions are closer to the central axis of the UniCell, the extraction time is shorter. In addition, the difference between the SRIM simulation assuming a point source of ions and the realistic image size of the ions from the TASCA separator in the UniCell should be taken into account. The farther the initial positions of the thermalized ions are from the central axis of the UniCell, the longer the extraction time will be, with a maximum difference of approximately 1.5 ms for singly charged ions. If the ions are released from different locations within the DC-cage (such as the distance is close to the edge of the first electrode of the DC-cage), the ions can also be effectively transported at the current simulation settings (such as E = 100 V cm-1 and Vpp = 200 V). The maximum extraction time is about 6 ms.

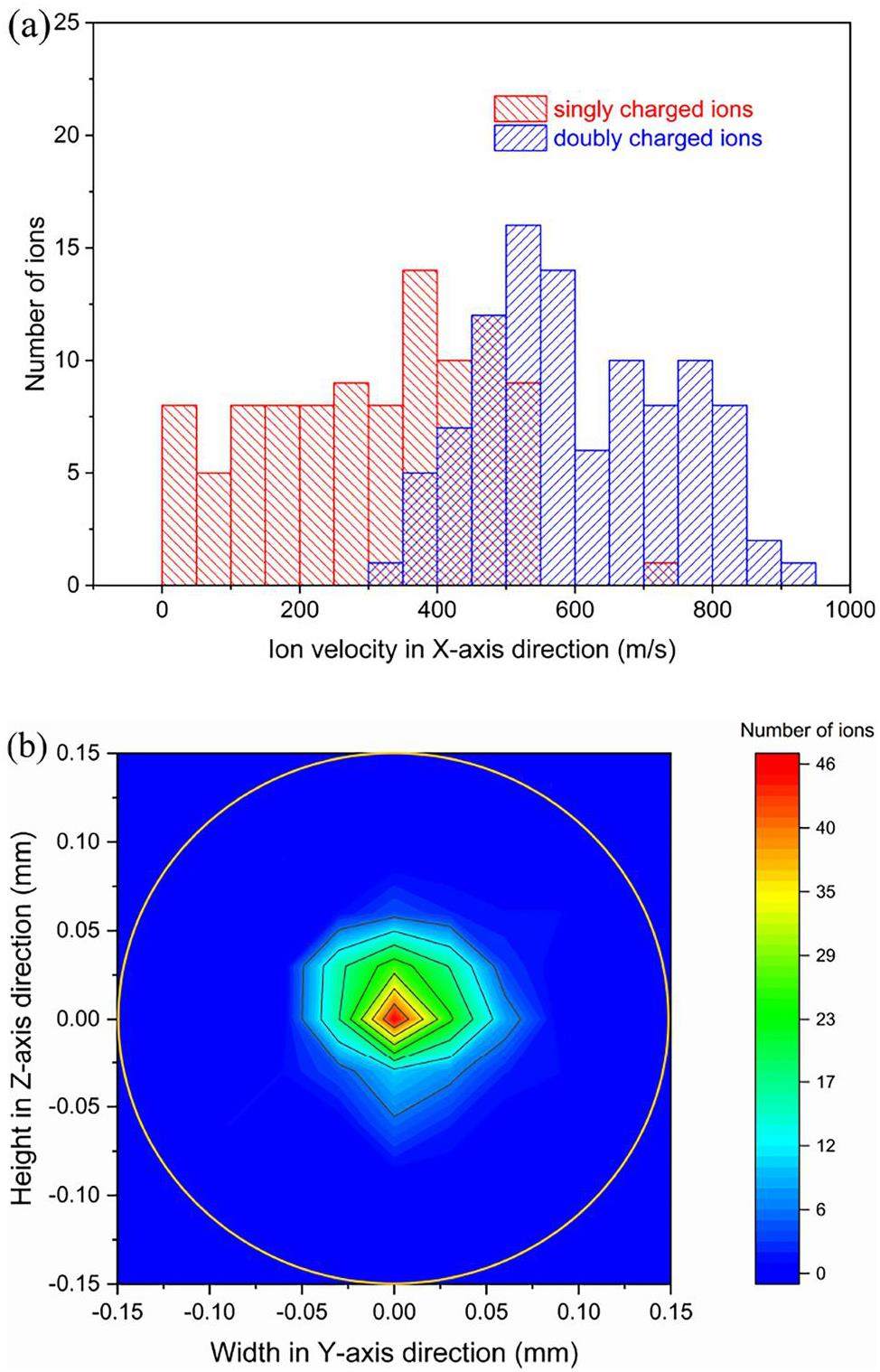

Through these optimizations, the following parameter values of UniCell were chosen for further studies on ion trajectories through the remaining setup: DC field strength E = 100 V cm-1, RF voltage Vpp = 200 V, and RF frequency f = 5 MHz. When the ions arrive at the nozzle, they have rather broad velocity distributions with mean velocity values of about 330 m/s and 630 m/s for ions in the 1+ and 2+ charge states, respectively, as shown in Fig. 8a. Figure 8b shows that the positions of all ions near the nozzle are focused within a circle with a radius well below 0.15 mm. This resembles the size of the funnel exit opening. These velocities and positions are used as the initial conditions for subsequent simulations of the ions’ propagation through the ITGF.

Ion Transfer by Gas Flow (ITGF) device

ITGF geometry

To ensure fast and efficient ion transfer from UniCell to a gas chromatography detector array for chemical studies, an RF-driven ejector to mitigate diffusion losses was proposed by Varentsov and Yakushev [27], but no ion-transport simulations were performed. In the present work, we investigate if an adapted geometry can be found, that allows guiding ions solely by gas flow without the need of time-varying electric fields. It is desirable to reduce electromagnetic interference in the detector array, which was shown to render the registration of decay events difficult [25]. Here, the Ion Transfer by Gas Flow (ITGF) device is put forward (Fig. 9a), and the results of numerical studies are presented in this section. The entrance of the ITGF is coupled to the UniCell nozzle; the entrance has a circular shape with an inner radius of 1.38 mm, which accepts the full distribution of ions behind the nozzle (cf. Fig. 8b). The cross-section transforms smoothly towards the exit of the ITGF, into narrow elliptical slit with a cross-section of 10 mm × 0.6 mm. This matches the cross-section of the miniCOMPACT detector array [40, 41]. The geometry of the inner ITGF channel changes along the ITGF while the channel cross-section stays essentially constant (see the geometrical parameters in the Supplementary Materail). The ions are only dragged by gas flow through this ITGF. In chromatography applications, the resolution depends on the gas flow rate [42]. To enable experiments with low gas flow rates, where diffusion losses are inevitable unless the ions are confined by electric fields, a design with an additional supply of sheath gas and an RF electrode structure was studied. For the latter case, the width of the electrodes and the thickness of the insulators between electrodes were each taken to be 0.1 mm, similar to the UniCell structure, as shown in Fig. 9a.

The ITGF interface is connected to the UniCell via a nozzle with a length of 2 mm. The half-angle of the diverting cone is chosen to be 34.6° in order to ensure a smooth connection (Fig. 9b). The maximum gas velocity at the nozzle exit is calculated to be 227 m/s-1.

Extraction efficiency from the ITGF

Extraction efficiency with gas flow only

Considering the UniCell and ITGF filled with helium gas near ambient temperature and pressure, the mean free path is calculated to be about 0.12 μm. The Knudsen number in the nozzle is calculated to be less than 0.01. The Reynolds number at the nozzle is calculated to be about 233. Therefore, it is a laminar flow inside the ITGF, which is consistent with the situation in Ref. [27]. The ITGF geometry was modeled using COMSOL in 3D. The coupling of the two interfaces, “Laminar Flow” and “Particle Tracing for Fluid Flow,” was used not only for gas flow simulation in the ITGF but also for the simulation of ion trajectories dragged by the gas flow in the ITGF. Here, “Compressible Flow (Mach < 0.3)” was selected as the compressibility of the gas. The boundary condition of the wall was “freeze”, which means that ions colliding with the wall are considered lost. The gas flow Q1 emerges from the UniCell. An additional sheath gas flow Q2 (see Fig. 9b) can be applied between the UniCell and the ITGF (Supplementary Material Fig. S2). The additional gas can be: i) a non-reactive sheath gas like He or Ar, ii) a reactive gas like H2 or O2 to form a chemical compound with the extracted ions, or iii) a mixture of both.

The particle tracing for the fluid flow interface was used to simulate the trajectory of each ion in the field of a propagating background fluid. The ion motion is governed by a combination of the Stokes drag force and the Brownian force; the Stokes drag force FD is proportional to the difference between fluid velocity u and ion velocity v and was implemented as

The gas flow between UniCell and ITGF is restricted by the UniCell outlet orifice, so uniform pressure distributions are mostly obtained within the UniCell (P1) and ITGF volumes (P2). Within the ITGF, a lower pressure is maintained by a vacuum pump. The resulting flow rate (Q1) varies with the differential pressure (

| Flow rate Q1 (mbar L s-1) | Flow rate Q2 (mbar L s-1) | Vmax (m/s) | Vend (m/s) | t (ms) | P2 (bar) | Extraction efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0 | 48 | 1 | 29 | 0.99 | 2% |

| 6 | 0 | 136 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 0.98 | 15% |

| 10 | 0 | 227 | 6 | 1.3 | 0.95 | 34% |

| 10 | 10 | 227 | 12 | 0.7 | 0.95 | 38% |

| 15 | 0 | 350 | 19 | 0.5 | 0.88 | 56% |

| 20 | 0 | 502 | 35 | 0.3 | 0.76 | 68% |

| 20 | 10 | 502 | 45 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 80% |

| 20 | 20 | 502 | 52 | 0.2 | 0.76 | 90% |

Extraction efficiency with gas flow and electrical fields

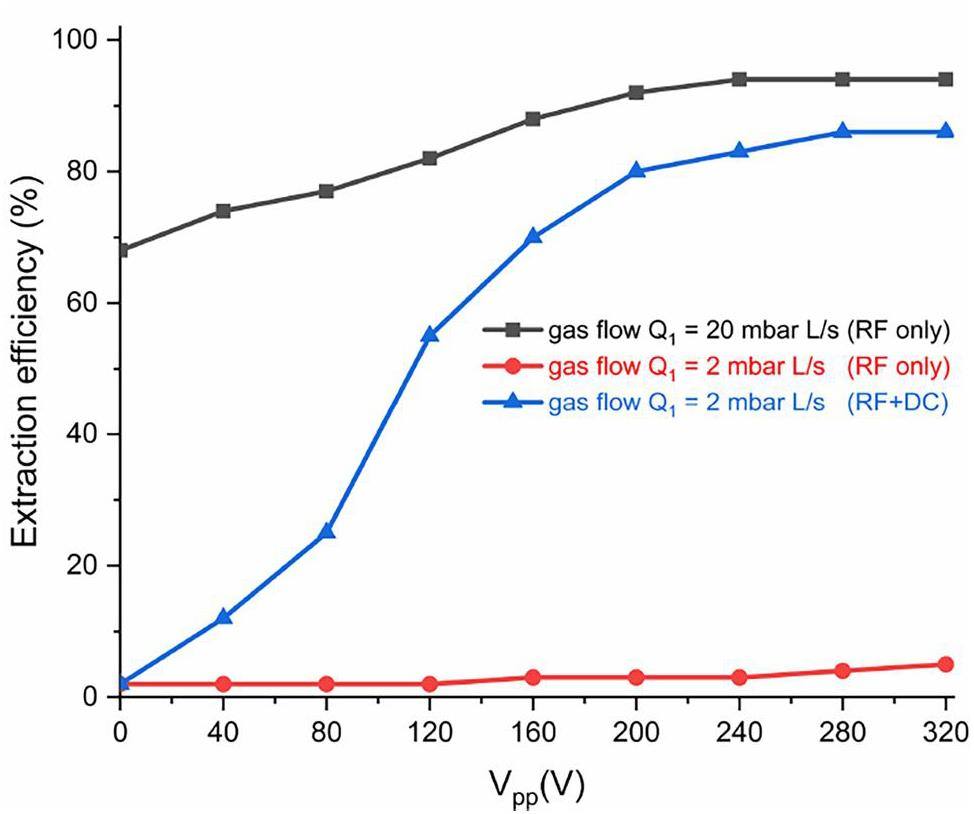

To further increase the ITGF extraction efficiency, the application of an RF signal with f = 5 MHz and Vpp up to 320 V to the ITGF electrode structure was considered, which is expected to reduce diffusion losses. However, at very low flow rates (e.g., Q1=2 mbar L s-1), the extraction efficiency of the ITGF still does not exceed a few percent. A significantly larger extraction efficiency was obtained by a combination of the RF field and a DC gradient. If the DC field strength of E = 100 V cm-1 is additionally applied to the ITGF electrodes, the extraction efficiency increases to 84%. At sufficiently large flow rates (e.g., Q1=20 mbar L s-1), the RF-only configuration with Vpp = 240 V can reach 94% extraction efficiency (see Fig. 10). Thus, when the gas flow is not sufficient for effective ion transport, implementing an RF field with a DC field allows for increased extraction efficiency.

Extraction efficiency with gas flow using diffusion loss evaluation

To assess the accuracy of the COMSOL simulation, the time-dependent diffusion displacement and subsequent losses were estimated. The mean squared lateral diffusional displacement

Conclusions and outlook

In this paper, we have introduced an ITGF device, which was designed to enable swift and efficient ion transfer of superheavy elements from the UniCell BGC to a detector array. Our numerical studies predict almost quantitative extraction and the total time (UniCell extraction time + ITGF transport time) to be well below the lifetimes of known isotopes of the elements of interest, 116Lv and 117Ts. Through our detailed simulations, the optimum DC field strength of the UniCell was found to be 100 V cm-1 at an RF peak-to-peak voltage of Vpp = 200 V at a frequency of 5 MHz. A flow rate of more than 20 mbar L s-1 required to ensure an extraction efficiency of 90% for an ITGF connected with UniCell. If lower flow rates are required by the experiment, the application of RF and DC fields in the ITGF should be considered. The UniCell and ITGF are currently under construction at GSI. The next step is the offline commissioning at GSI. This is foreseen to include: 1) application test of an RF peak-to-peak voltage of Vpp = 200 V at a frequency of 5 MHz, and 2) evaluation of the effectiveness of the repulsive force of the funnel-shaped RF electric field at a 100 V cm-1 DC electric field strength. Special attention will be given to the supply of purified gas and the characterization of efficiency degradation by gas impurities. The optimum operating parameter values obtained within this work serve for the detailed planning of the layout of the UniCell + ITGF setup and will be used as initial parameters in the upcoming commissioning. In the following project phase, a vacuum interface will be developed which will allow coupling UniCell to devices that e.g., allow mass measurements. We are confident that this setup will contribute to enhancing the performance of existing gas stopping setups and facilitate the development of new systems.

Foreword

. Nucl. Phys. A 944, 1-2 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2015.11.004The quest for superheavy elements and the limit of the periodic table

. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6. 86-98 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-023-00668-yFusion reaction 48Ca + 249Bk leading to formation of the element Ts (Z=117)

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Genealogy of gas cells for low-energy RI-beam production

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 317, 450-456 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.08.062Heavy-ion-induced production and physical preseparation of short-lived isotopes for chemistry experiments

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 551, 528-539 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2005.05.077Advances in the Production and Chemistry of the Heaviest Elements

. Chem. Rev. 113, 1237-1312 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1021/cr3002438Superheavy element flerovium (Element 114) is a volatile metal

. Inorg. Chem. 53, 1624-1629 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/ic4026766Online chemical adsorption studies of Hg, Tl, and Pb on SiO2 and Au surfaces in preparation for chemical investigations on Cn, Nh, and Fl at TASCA

. Radiochim. Acta. 106, 949-962 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1515/ract-2017-2914On the adsorption and reactivity of element 114, flerovium

. Front. Chem. 10,The recoil transfer chamber—An interface to connect the physical preseparator TASCA with chemistry and counting setups

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 638, 157-164 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2011.02.053First study on Nihonium (Nh, Element 113) chemistry at TASCA

. Front. Chem. 9,Chemical studies of elements with Z≥104 in gas phase

. Nuclear Phys. A 944, 640-689 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2015.09.012Nucl. Instrum. Helium-jet ion guide for an on-line isotope separator

. Methods Phys. Res. 179, 533-539 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(81)90179-8Ion guide method for on-line isotope separation

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 26, 384-393 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-583X(87)90783-XSlow RI-beams from projectile fragment separators

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 204, 570-581 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-583X(02)02151-1A Simple Printed Circuit Board–Based Ion Funnel for Focusing Low m/z Ratio Ions with High Kinetic Energies at Elevated Pressure

. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 30, 1813-1823 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-019-02241-3Design, construction and cooling system performance of a prototype cryogenic stopping cell for the Super-FRS at FAIR

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 770, 87-97 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.09.075The CARIBU gas catcher

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 376, 246-250 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2016.02.050Ion transfer from an atmospheric pressure ion funnel into a mass spectrometer with different interface options: Simulation-based optimization of ion transmission efficiency

. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 30, 372-378 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7451Ambient Pressure Ion Funnel: Concepts, Simulations, and Analytical Performance

. Anal. Chem. 92, 15811-15817 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02938The science case of the FRS Ion Catcher for FAIR Phase-0

. Hyperfine Interact. 240, 73 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10751-019-1597-4Developments for resonance ionization laser spectroscopy of the heaviest elements at SHIP

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 383, 115-122 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2016.06.001The performance of the cryogenic buffer-gas stopping cell of SHIPTRAP

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 463, 280-285 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2019.05.009The cryogenic gas stopping cell of SHIPTRAP

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 338, 126-138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2014.08.004Rapid extraction of short-lived isotopes from a buffer gas cell for use in gas-phase chemistry experiments, Part II: On-line studies with short-lived accelerator-produced radionuclides

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 507, 27-35 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2021.09.004Rapid extraction of short-lived isotopes from a buffer gas cell for use in gas-phase chemistry experiments. Part I: Off-line studies with 219Rn and 221Fr

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 995,Concept of a new Universal High-Density Gas Stopping Cell Setup for study of gas-phase chemistry and nuclear properties of Super Heavy Elements (UniCell)

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 940, 206-214 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2019.06.032Synthesis of the heaviest elements in 48Ca-induced reactions

. Radiochim. Acta 99, 429-439 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1524/ract.2011.1860High-precision mass spectrometry of nobelium, lawrencium and rutherfordium isotopes and studies of long-lived isomers with SHIPTRAP

.Gas phase chemical studies of superheavy elements using the Dubna gas-filled recoil separator – Stopping range determination

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 268, 28-35 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2009.09.062Design and implementation of a new electrodynamic ion funnel

. Anal. Chem. 72, 2247-2255 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac991412xZero-field mobilities in helium: highly accurate values for use in ion mobility spectrometry

. Int. J. Ion Mobil. Spectrom. 15, 21-29 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12127-011-0079-4A Novel Method for the Measurement of Half-Lives and Decay Branching Ratios of Exotic Nuclei with the FRS Ion Catcher

.Radio frequency and DC high voltage breakdown of high pressure helium, argon, and xenon

. JINST 15,Characterization of the electrical breakdown for DC discharge in Ar-He gas mixture

. Vacuum. 169,Discharge phenomena of an atmospheric pressure radio-frequency capacitive plasma source

. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 20-28 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1323753Doubly magic nucleus 108270Hs162

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97,Nuclear structure and reaction studies near doubly magic 270Hs

. Radiochim. Acta. 100, 75-83 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1524/ract.2011.1874A Comparison of Brownian and Turbulent Diffusion

. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 13, 47-53 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829008959423Dispersion and Deposition of Spherical Particles from Point Sources in a Turbulent Channel Flow

. Aerosol Sci. Tech. 16, 209-226 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829208959550The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01772-7.