Introduction

The performance of electron sources plays a key role in the development of high-brightness beam applications [1, 2], such as short-wavelength high-gain free electron lasers [3], ultrafast electron diffraction and microscopy [4, 5], inverse Compton scattering [6], injection of high-gradient advanced accelerators [7], and high-power THz generation [8]. To serve the fields of medicine, material science, and biology at the atomic and molecular scales, electron guns of different types, including continuous wave(CW) [9, 10] and pulsed [10] guns, are being continuously improved, enabling X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) to be applied to lasers with a higher photon energy, higher efficiency, and shorter pulse length. In various applications of photoinjectors, a concomitant challenge is to improve the brightness of the beams produced by the sources. At present, XFEL upgrades require higher beam quality. One direction is to provide a photon source at an extremely high photon energy (MaRIE XFEL) [11], and the other is to achieve an ultracompact XFEL [12] with a shorter footprint while maintaining the geometric emittance of the beam at a lower energy. At the Shanghai Soft X-ray Free-Electron Laser (SXFEL) facility [13], because of the demand for better beam performance and higher energy, photocathode electron guns with lower emittance, higher peak current, and lower energy spread should be urgently studied. In the research of photocathode guns, two problems exist that are worth paying attention to. One is the influence of the emittance of the multipole field introduced by the couplers, and the other is the suppression of microbunching instability by reducing the compression factor in the magnetic compression process [14, 15].

At present, the emittance and brightness of electron beams produced by photocathode injectors still have much room for improvement compared with the theoretical limits [16]. Therefore, photocathode radiofrequency (RF) electron guns should be studied as they show great potential for upgrading advanced light sources and FEL facilities. Pulsed RF electron guns are a category of electron sources that operate in the pulsed/burst mode. Compared with CW guns, they can provide a high pulse current, high brightness, short pulses, and low emittance [10, 17]. In RF photoinjectors, electrons are extracted from the material upon the absorption of photons, and a high electric field on the cathode can help reduce the emittance, particularly in the case of high charge emission due to the Schottky effect. Considering the limitations of S- and X-band electron guns, the C-band electron gun is promising for achieving better performance for the SXFEL. In addition, different coupler designs in the electron gun contribute to a more compact structure and better RF performance. Including the single-feed configuration, dual-feed configuration, four-port structure, and the use of a dummy waveguide in the Fermi II gun, the exploration of different coupling methods is also an important part of injector design [18-23].

With the development of RF technology and continuous research on breakdown physics, cryogenic structures using normal conducting technology have provided a new approach to achieve a higher gradient [24, 25]. It should be mentioned that in tests of X-band structures operating at 45 K, the enhanced quality factor (Q0) and significantly higher fields have been demonstrated, with surface fields approaching E0=500 MV/m [26]. Research on cooled copper, high-frequency structures, and different copper alloys has also confirmed that RF breakdown can be effectively reduced by changing the material parameters at low temperatures [27, 28]. Operating under cryogenic conditions significantly improves the cavity performance; however, lower temperatures result in a higher cryostat cost. Compared with the superconducting cavity at 4 K, the temperatures of cryogenic operation at a much lower cost were selected as 20 K in the KEK gun [29] and 77 K for the C3 structures using nitrogen [30]. It can be clearly observed in [31] that there is still a large reduction in the surface resistivity from 77 K to 40 K, which means there is much room to improve the quality factor. While the surface resistivity decreases quite slowly from 40 K to 20 K, the cryogenic gun at 40 K appears to have a similar performance and is less demanding for the cooling conditions of the cryostat. In addition, research on cathode materials with respect to the mean transverse energy (MTE) is also being conducted rapidly, such as the Cryogenic Cathode Testbed at PBPL [28]. In summary, structures in the cryogenic state have become a potential technical route for improving the gradient in e-gun design.

Based on the experimental results, a new structure of the C-band RF gun operating at 5712 MHz was designed to achieve a more compact injector layout. The TM02 mode in the cathode cell indicates that additional cavity structures and RF power-coupling schemes can be attempted. Owing to the stability and insensitivity of the TM02 mode, the installation error can be effectively reduced. The RF power in the cryogenic gun is considerably lower in the designed electron gun compared with those in room-temperature RF guns. In addition, the change in the performance of Cu at low temperatures is favorable for achieving a higher accelerating gradient and a higher-brightness electron beam. This paper presents the optimization of the RF design and beam dynamics of an electron gun. In Sect. 2, a comparison of the injectors based on the 1.6-cell, 2.6-cell, and 3.6-cell electron guns is presented. The final optimized results of the designed cryogenic injector for beam dynamics are also shown. In Sect. 3, the optimization of the RF design for the new gun, including the cavity design, local field, and multipole mode suppression, is presented. In Sect. 4, two novel coupling schemes are presented, and the basic simulation is completed. In Sect. 5, the necessary RF performance of the gun in the cryogenic state is analyzed and a subsequent experimental arrangement is introduced.

Beam dynamics

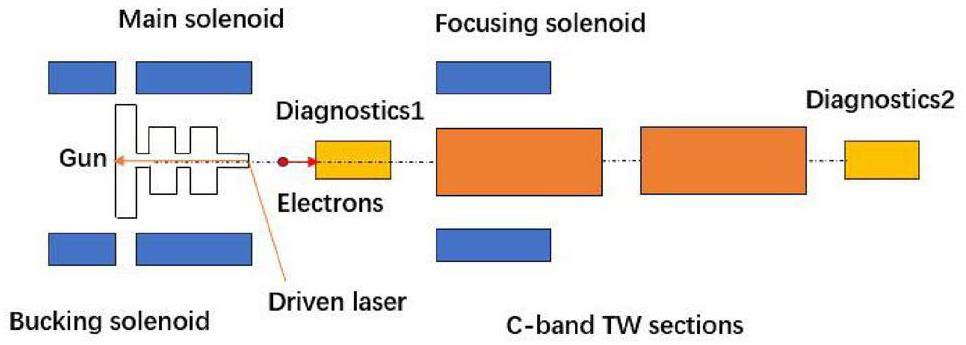

The structural design and beam dynamics of an electron gun should be iteratively optimized to obtain better beam quality [32]. The photoinjector consists of an electron gun, several solenoids, two C-band acceleration sections, and the necessary beam diagnostics sections, as shown in Fig. 1. An RF gun can generate an electron beam produced in a photocathode via laser irradiation. The C-band traveling-wave sections are responsible for accelerating the beam to a higher energy [33, 34]. In this study, the solenoids used to compensate for emittance growth were designed to wrap around the electron gun.

In this section, ASTRA [35] is used to simulate the beam dynamics of the electron gun. In this simulation, the necessary parameters of each component in the injector were scanned to obtain better performance of the C-band photocathode injector.

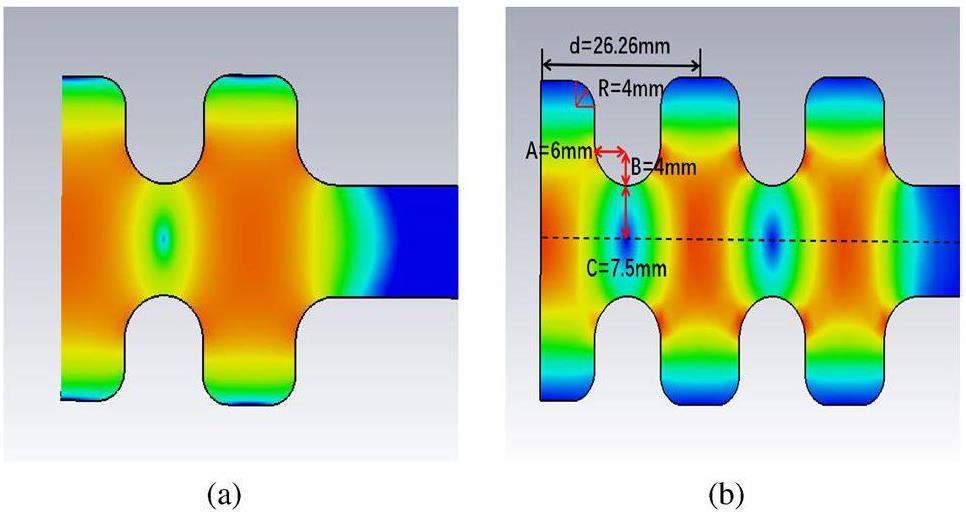

In theory, a higher cathode gradient can reduce the effect of the space-charge force on the beam such that a shorter initial electron bunch can be used for the same bunch charge, thus resulting in a higher peak current and brightness [36]. For C-band electron guns, the gradient that can be achieved at room temperature is 150 MV/m [37]. In this beam dynamics simulation, the desired gradient of the gun in the cryogenic state was selected to be 200 MV/m. Considering that the present S-band gun in the SXFEL uses 500 pC, 5 ps beams, different initial beam parameters were set in this simulation to observe the beam evolution in both the 1.6- and 2.6-cell guns, which are only different in cell numbers (Fig. 2). The specific scanning process is as follows. After setting the initial beam state, parameters including the gradient, position, and phase of the two TW structures are scanned with the two solenoids outside, finally obtaining beam states at the photoinjector exit. In this process, the optimization is mainly focused on the beam emittance, beam length, beam size, and energy spread. In addition, the MOEA algorithm [38, 39] based on ASTRA was used to obtain better optimization results. The input parameters for the beam dynamics optimization are listed in Table 1.

| Input parameters | 1.6-cell | 1.6-cell | 2.6-cell |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bunch charge (pC) | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Laser pulse FWHM (ps) | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Cathode gradient (MV/m) | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Electron gun phase (°) | -20~10 | -20~10 | -10~10 |

| TW section max gradient (MV/m) | 20~45 | 20~45 | 20~45 |

| TW section 1 phase (°) | -30~0 | -30~0 | -10~0 |

| TW section 1 position (m) | 0.5~2.0 | 0.5~2.0 | 0.5~2.0 |

| TW section 2 phase (°) | -30~0 | -30~0 | -10~10 |

| TW section 2 position (m) | 2.0~2.2 | 2.0~2.2 | 2.0~2.2 |

| Main solenoid magnetic field strength (T) | 0.04~0.4 | 0.01~0.28 | 0.3~0.4 |

| Main solenoid position (m) | 0.204~0.220 | 0.204~0.220 | 0.006 |

| Focusing solenoid magnetic field strength (T) | 0.1~0.5 | 0.1~0.5 | 0.01~0.28 |

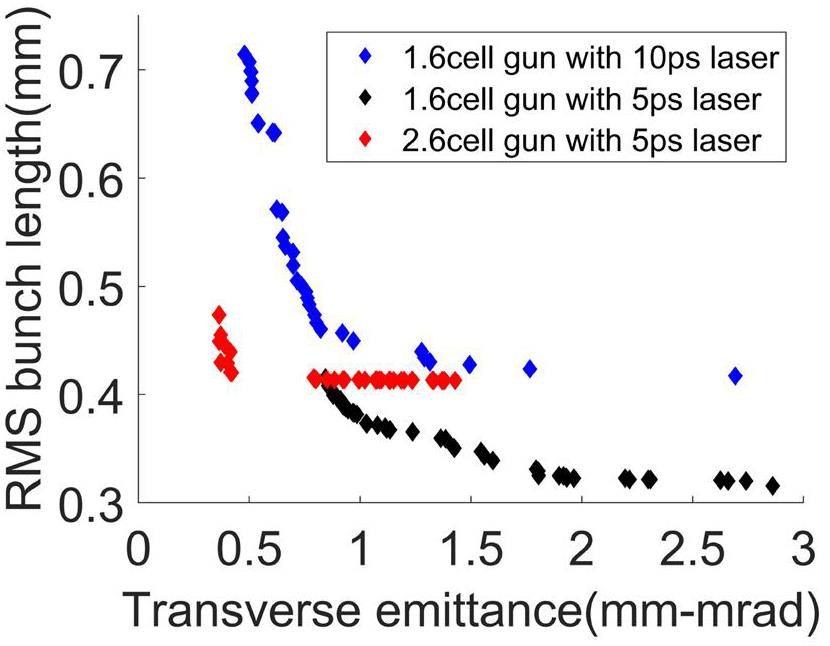

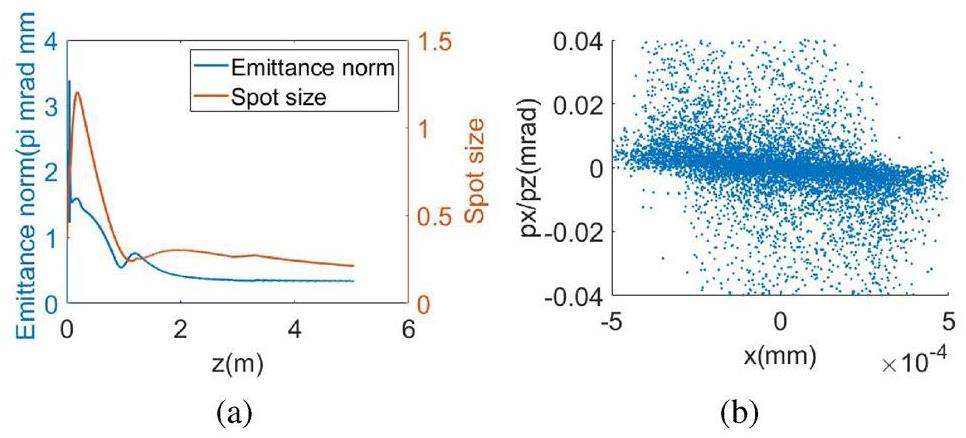

In Fig. 3, the beam dynamics performance in the 1.6-, 2.6-, and 3.6-cell [37] guns are compared. The 1.6-cell gun with a main solenoid can be optimized for multiple-beam simulations; however, it is difficult to use shorter bunches. The 2.6-cell gun with a main solenoid and a bucking solenoid has better beam parameters, which implies more sophisticated engineering. Compared to the existing S-band gun in the SXFEL, the C-band electron gun aims at lower emittance and higher cathode gradient. Considering that studies on 3.6-cell electron guns in the C-band at room temperature have already been conducted, the beam dynamics of injectors based on 1.6- and 2.6-cell electron gun structures under cryogenic conditions were investigated in this study. The dimensions in Fig. 2 describe the gun structure used to generate the microwave field for the beam dynamics simulation. First, the initial beam (500 pC, 5 ps) was tracked in the injector using a 1.6-cell gun. Through algorithmic optimization, it was found that it was difficult to achieve a low emittance below 0.8mmmrad because of the strong space-charge force. When only one TW section was added, reducing the emittance to an acceptable range seemed to require a more complicated optimization process despite having a short beam length. Then, the FWHM of the laser pulse was changed as 10 ps to repeat the process. After optimization, the emittance of the bunch was reduced to below 0.5mmmrad; however, the bunch length increased significantly. Finally, the beam dynamics of the injector based on the 2.6-cell gun was optimized using the initial beam (500 pC, 5 ps). The results showed that an injector with a 2.6-cell cryogenic gun can have a lower transverse emittance, close to 0.36mmmrad, and a shorter bunch length of 0.44 mm. Comparing the beam dynamics optimization results of the cryogenic injector with the previous design of a 3.6-cell gun injector at room temperature [37], it can be observed that the emittance of the bunch obtained by the cryogenic injector reached a low level, and further optimization will be carried out to obtain better results in the future. In the 5712 MHz electron gun, a reasonable laser pulse FWHM should be less than 5 ps, which means that the 1.6-cell model in the simulation is inadvisable. Therefore, the 2.6-cell structure was selected for the subsequent design. An acceptable working point was selected and further optimized. The final beam states at the photoinjector exit are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 2.

| Input parameters | 1.6-cell | 2.6-cell | 3.6-cell |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bunch charge (pC) | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Laser pulse FWHM (ps) | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Gradient (MV/m) | 200 | 200 | 150 |

| RMS laser size(mm) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.35 |

| Emittance on cathode (mm·mrad) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.28 |

| Beam energy (MeV) | 26.9 | 103 | 107 |

| Transverse emittance (mm·mrad) | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| RMS bunch length (mm) | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Mean slice emittance (mm·mrad) | 0.56 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

RF design

CST Microwave Studio [40] and SUPERFISH [41] were used to design the entire RF gun. In this design, the electric field along the z axis of the electron gun was balanced, adjacent modes were effectively separated, and the electric field on the cell walls was reduced.

Cavity Design

Based on a comparison of the beam dynamics, a 2.6-cell structure was adopted for further optimization. By adjusting the structural parameters of the gun, changes in important RF parameters, including the surface electric field and quality factor, were observed, which provide a valuable reference for the optimal design of electron guns.

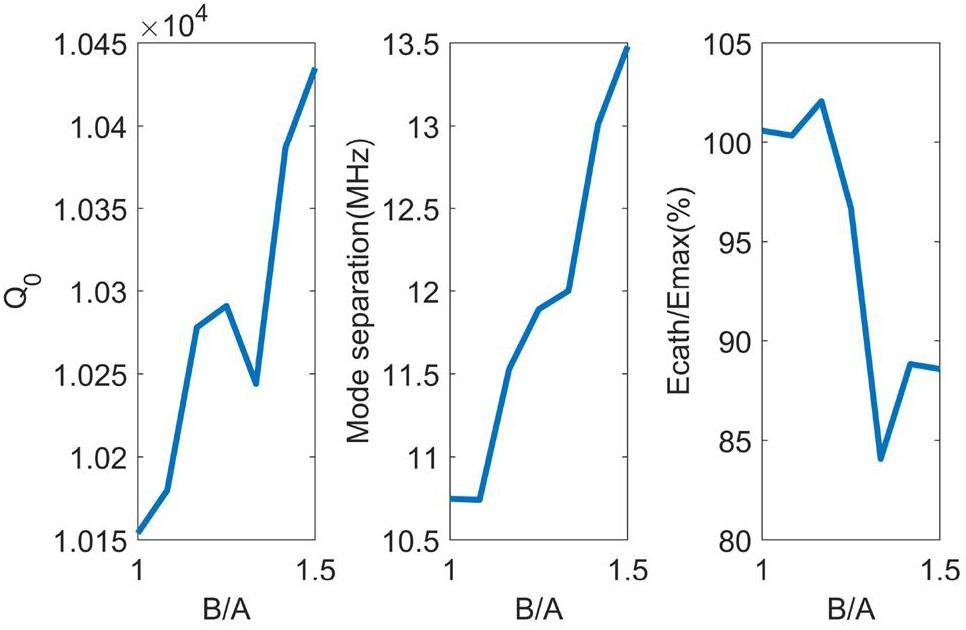

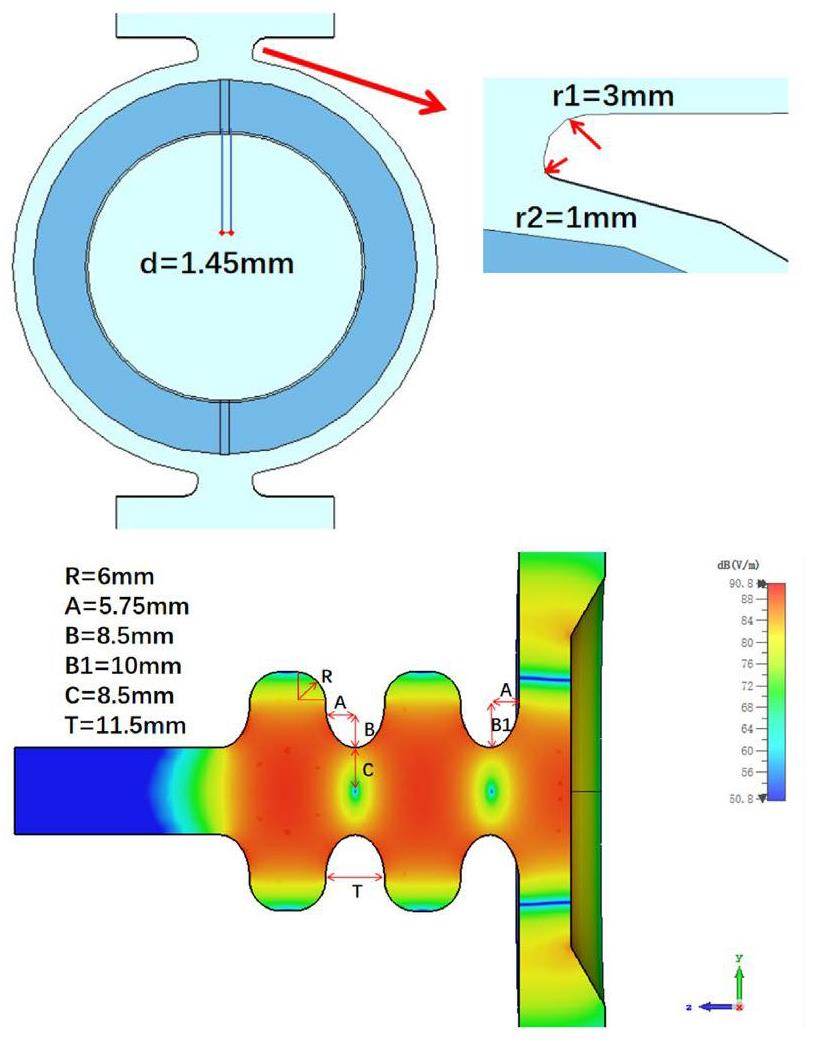

In Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, A represents the axis of the ellipse at irises along the z-axis, B represents the axis of the ellipse at irises along the radial direction, C and R are the beam hole radius and chamfer radius at the cell walls, Ecath represents the E field at the cathode, and Emax represents the maximum E field at the iris. Figure 2(b) shows that the electric field intensity at the iris is quite high in the electron gun operating in π mode. In the preliminary consideration of the RF breakdown rate and dark current emission phenomenon, it is necessary to optimize the shapes of the cell walls and iris to minimize both the surface electric and magnetic fields. In the design of the electron gun, the iris aperture and rounding were adopted to guarantee a higher shunt impedance and lower surface electric field. Meanwhile, the influence of the iris length between adjacent cavities on the coupling factor was also considered to maintain the mode separation within an acceptable range.

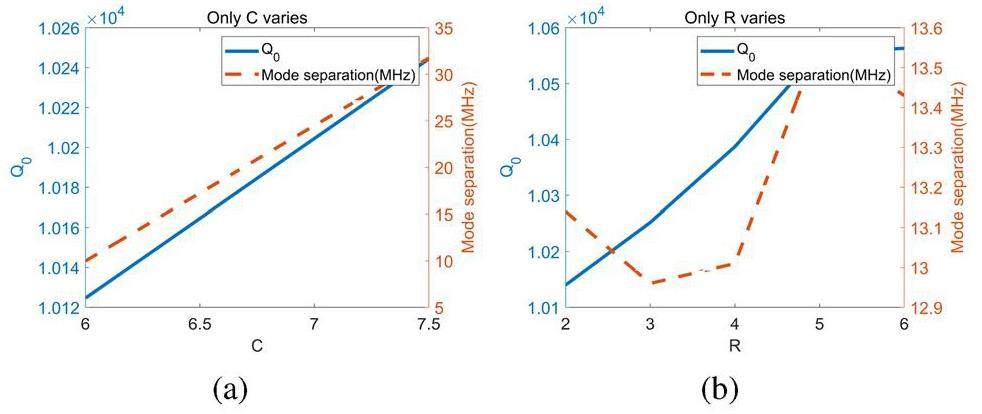

Figure 5 shows that each RF parameter has a better performance when the ratio of the horizontal and vertical axis of the ellipse contour is controlled near 1.3~1.4. This is because this ratio realizes a seamless connection between the rounding of the cell walls and iris aperture, which effectively increases the surface area, thus reducing the surface electric field and power loss. Because the field emission is exponentially related to the surface electric field, this helps reduce the contribution of the dark current at the iris. Based on the change in radius of the circular chamfer of the model shown in Fig. 6, it can be found that this design is useful to achieve a higher quality factor, which helps to reduce the RF power dissipation on the cell walls and the RF power needed.

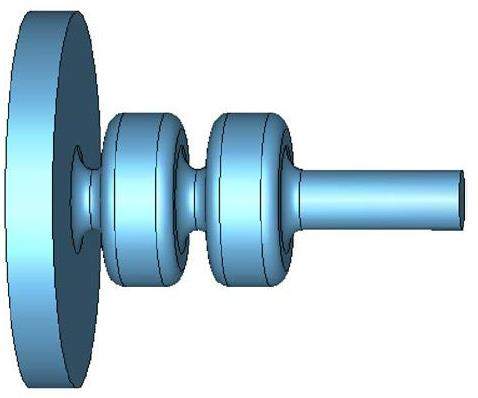

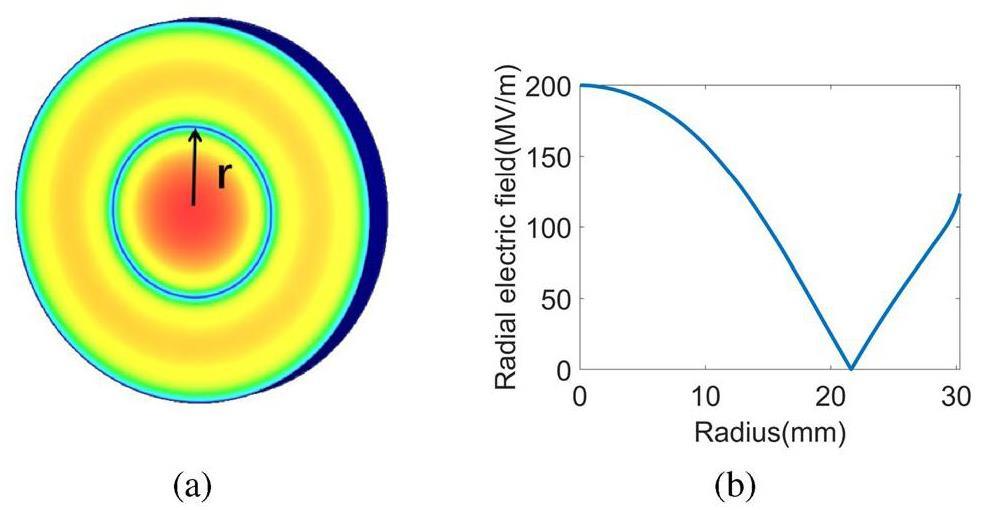

To reduce the error during installation and decrease the dark current at the cathode, a new electron gun with a TM02-mode cathode cell was designed. The optimized results can provide a reference for the full cells and later coupler designs. The new gun structure is shown in Fig. 7. In the TM02 mode, the radial electric field at the cathode plane is shown in Fig. 8. The minimum electric field was observed over a circular region of radius (r = 21.616 mm). Because field emission often occurs near the groove at the edge of the cathode plug (Cu plug), the edge of the cathode plug can be set at this position, which means that the electric field at the cathode edge can be effectively reduced, thereby reducing dark current generation. Because the cavity design still needs to consider the subsequent power-coupling factors, it is a continuous iterative process. Here, we propose a new electron gun structure, and the final optimized structural parameters are presented in the following section.

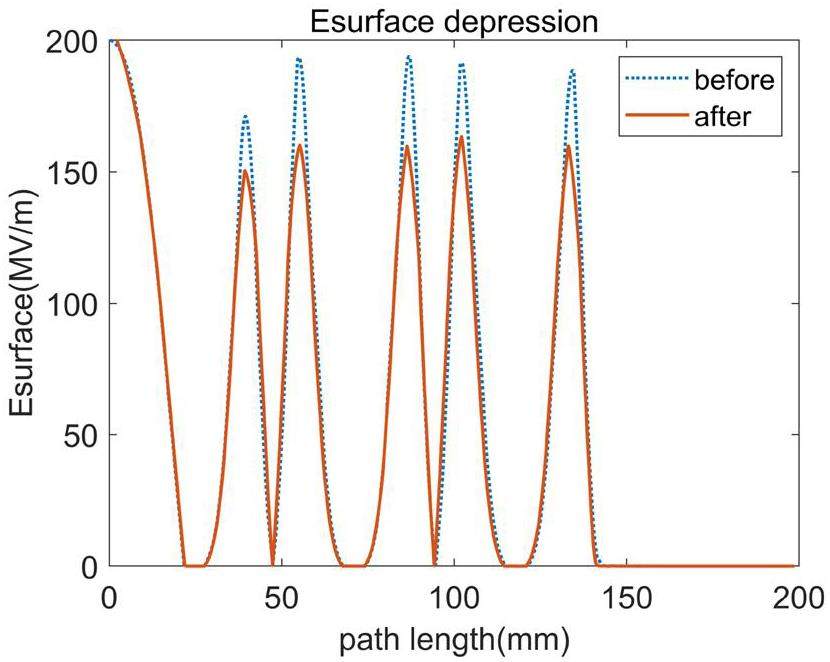

Suppression Of High Field On Surface

The gradient on the cathode of the electron gun was designed to reach 200 MV/m under the working conditions. Although the material has a higher hardness at low temperatures, it is necessary to consider the RF breakdown phenomenon, which may be caused by the high electric field on both the cathode and cell walls. To predict and analyze the performance of the structure at a high gradient, the modulated Poynting vector [42] was calculated as follows:

After optimizing the parameters (A, B, and C), the surface electric field was reduced, as shown in Fig. 9. Sc in the RF gun was estimated while working at room temperature, and the maximum Sc= 4.84 W/ m2, which is less than the 5 W/ m2 recommended in experimental studies [42]. The maximum Sc is located near the iris because of the reactive power flow oscillating along the electromagnetic field in each cycle of the standing wave structure. The maximum RF pulse heating was 19.98 K, which was less than the limit of 50 K at room temperature.

Coupler Design

In the accelerating structure, the RF power is generated by the power source and transmitted to the structure through a transmission path. Couplers are the components used to feed RF power from the waveguide network into the structure.

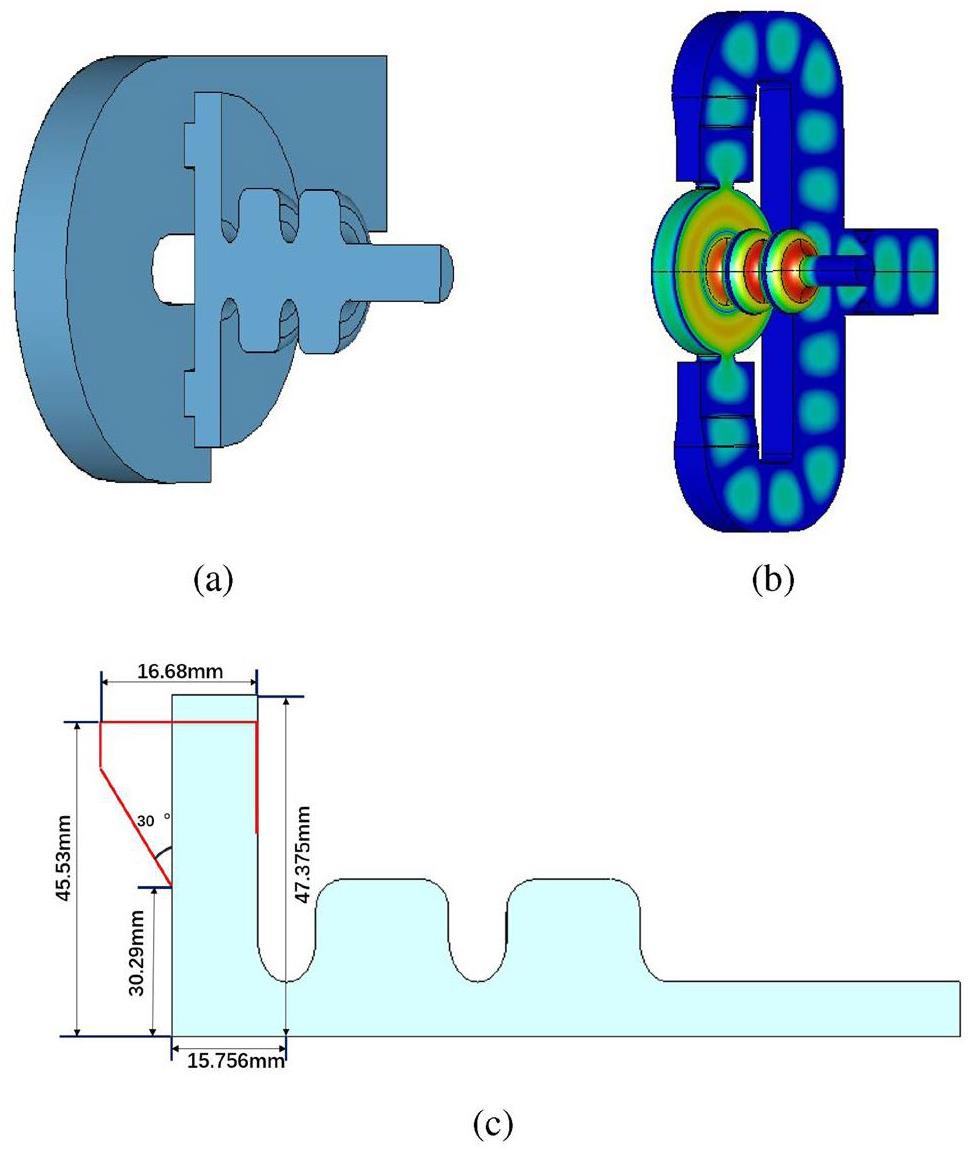

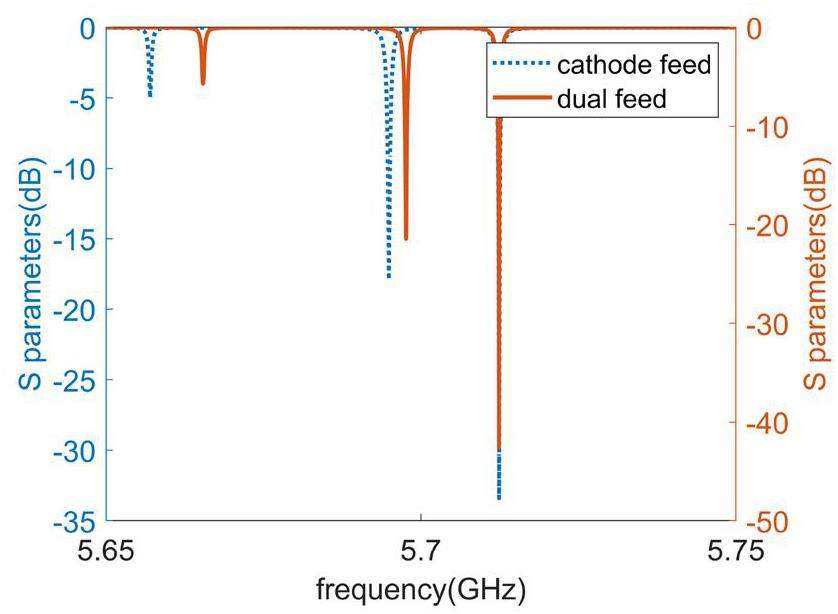

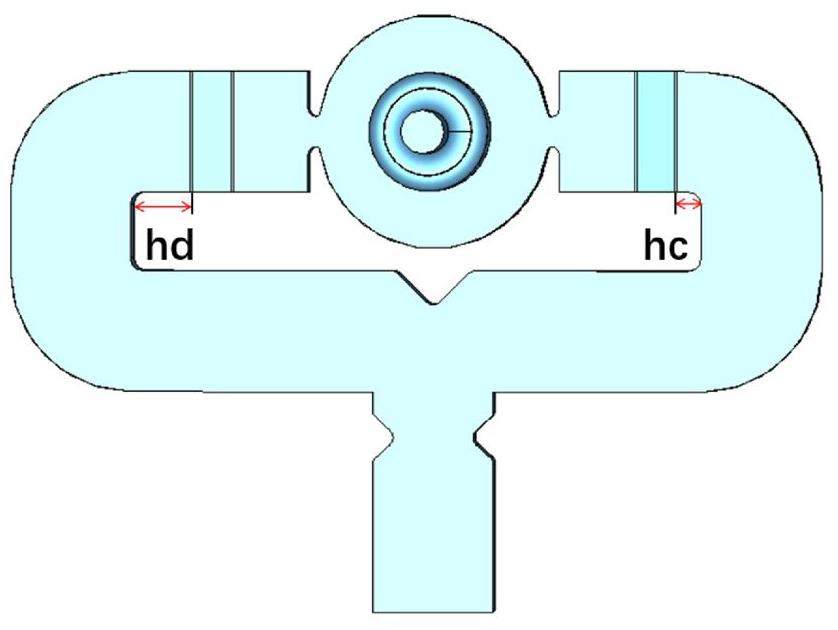

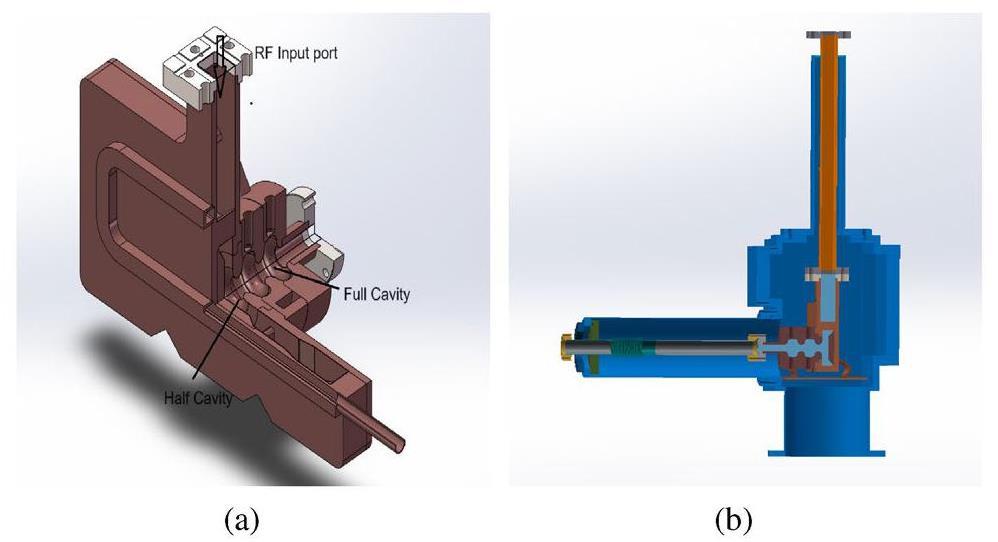

Coupler Design on the Cathode Cell

Considering factors such as beam dynamics and multipole field, it is innovative to feed RF power into the cathode cell by adjusting its shape and size rather than using the traditional coaxial coupling or inserting the coupler into the full cell. Feeding RF power into the cathode cell allows the solenoids to be placed closer to the cathode to achieve a better beam quality. However, owing to the limited size of the cathode cell, significant efforts have been made to explore the proper structure of the cathode cell working in the TM02 mode, with the other two full cells still maintaining the TM01 as their working mode. It is worth mentioning that the TM02 mode can achieve fewer errors during installation owing to its stability and insensitivity compared to the traditional TM01 mode. Therefore, we propose two designs, as shown in Fig. 10: one uses a J-shaped waveguide to directly insert the coupling holes into the plane where the cathode is located, and the other widens the outer contour of the cathode cell to place the coupling ports and feed RF power with a T-shaped waveguide. In contrast, the T-shaped waveguide coupling facilitates a cathode plug. Here, we selected the traditional dual-feed scheme for further optimization. The cathode feed scheme will be studied later as an alternative.

Because of the TM02 working mode in the cathode cell, these structures have more possibilities. In the selected scheme, the shape of the cathode plane can be optimized to accommodate alternative cathodes(Cu plugs). Relevant experiments have shown that the field emission occurring in the groove around the cathode plug is often the main contributor to the dark current [43]. Because the TM02-mode electric field has a minimum electric field in the radial direction of the cathode insertion position and exists in a circular profile, the edge of the cathode can be set at this profile to effectively reduce the field emission. After testing many coupler port shapes, a dual feed on the cathode cell with Z-coupling slots was adopted [18]. The length of the coupling slots was consistent with that of the wall of the cathode cell, and the required radius was easily fabricated. By adjusting the radius of the chamfers (r1,r2) at the coupling slots, the locally generated pulse heating can be controlled. To facilitate the power feed, an external waveguide was designed by connecting the coupler to a T-shaped waveguide structure through a transition section. By setting the two ports at the T-waveguide external power feed port and at the transition interface, the S21 parameter was adjusted to approximately -3 dB in working mode. Because the beam load was low, the coupling coefficient was set to 1 at the operating frequency of 5.712 GHz. Under this condition, the S11 parameter in the working mode is close to -35 dB, and power feeding is realized as shown in Fig. 11.

Optimization Of Multipole Mode

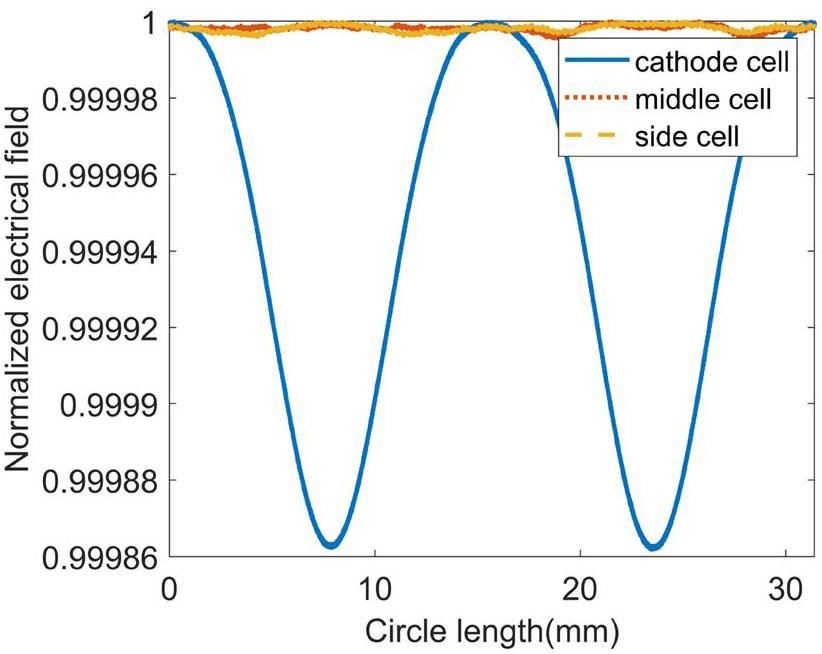

The axisymmetric structure of the cavity was destroyed by the addition of a coupler. Therefore, the electric and magnetic fields exhibit an uneven azimuthal distribution, which destroys the symmetry of the electron beam at the exit of the electron gun. To reduce the influence of the multipole components on the quality of the electron beam, the electric field along the beam axis in each cell in the electron gun was derived from a small circle to observe the multipole field introduced by the coupler ports.

The dual-feed scheme effectively reduced the dipole mode in the cathode cell. The shape of the racetrack gun shown in Fig. 12, which can suppress the quadrupole field, was adopted based on the TM02 mode cavity to reduce the influence on the transverse momentum and emittance of the beam.

Figure 13 shows that the multipole components are simulated on a circle with radius 5 mm and as can be observed, the multipole filed in the full cells is much weaker than that in the cathode cell. By optimizing the racetrack arc separation, d, the intensity of the quadrupole field was controlled to approximately 0.01 % in the gun. In addition, it is necessary to analytically evaluate the effect on beam quality. Considering that the strongest multipole field mainly exists in the cathode cell, the transverse momentum imparted to an electron beam by the RF field in the cathode cell was calculated using the Panofsky–Wenzel theorem [44, 45] as follows:

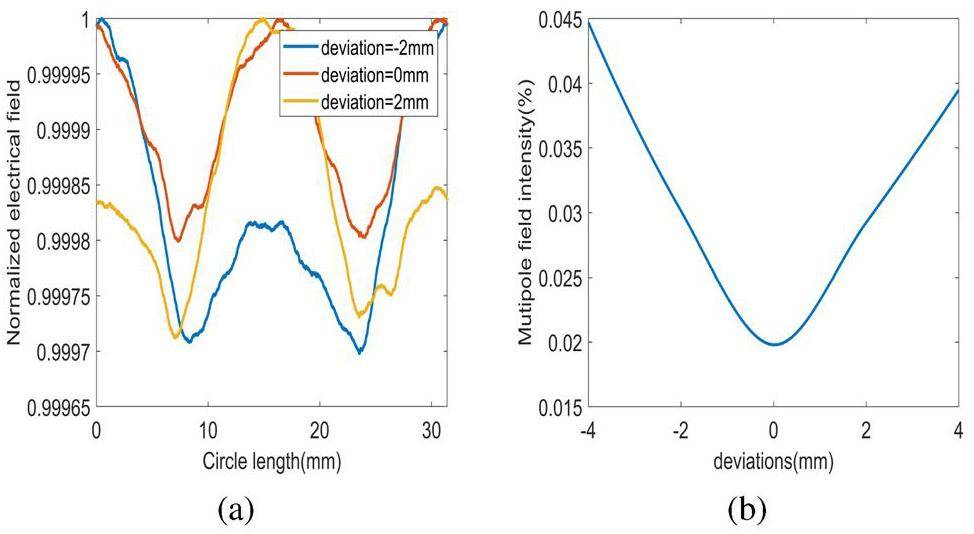

Finally, the T-shaped waveguide was changed to an asymmetrical waveguide to study its stability and insensitivity. Because the cathode cell of the TM01 mode is generally not used for power coupling, the influence on the microwave field inside the TM02 cathode cell from the length of the external waveguide is analyzed. In the optimized structure, hc = 10 mm. The electric field derived from the circle in the cathode cell was observed by varying hd as shown in Fig. 14. Figure 15 shows that the quadrupole field gradually transforms into the dipole field with the change of hd, which means that the millimeter-magnitude error caused by installation will affect the suppression effect of the multipole field. The deviations represent the error (hd-hc) that may have been introduced during the installation. The multipole field intensity introduced by the hd change is shown in Fig. 15. After the calculation, the suppression effect of the quadrupole field strength can still reach approximately 0.03 % within a range of variation in hd of 2 mm.

Analysis at Cryogenic State

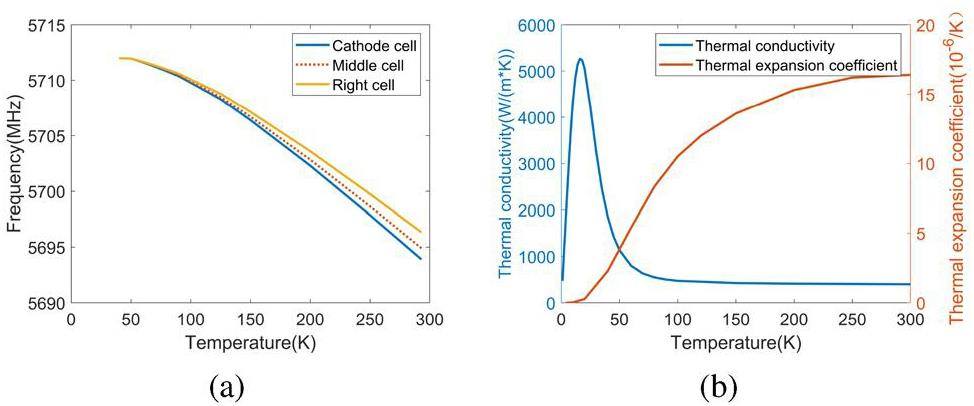

After completing the basic design of the RF structure, it is necessary to predict the performance of the gun at low temperatures. Considering the change in material conductivity, thermal expansion coefficient, and other parameters with temperature, as well as cooling conditions, the working temperature of the gun was changed from 293 K to 40 K in the simulation to predict the trend of displacement and frequency shift.

RF Properties under Low Temperatures

The RF performance of the electron gun structure needs to be tested after machining, and some of its key parameters must be predicted [34, 46-52]. To achieve gun operation below 40 K, the effect of cryogenic temperature on the RF properties of the cavities must be analyzed. Several important parameters must be considered as the temperature decreases. The first parameter is the residual resistivity ratio (RRR), which is often defined as the ratio of the resistivity of materials at room temperature and that at absolute zero. For copper with different RRRs (or purities), the resistivity is different at low temperatures. In the following calculations, RRR = 300 was selected to obtain the surface resistance of copper in a C-band gun operating at 5712 MHz.

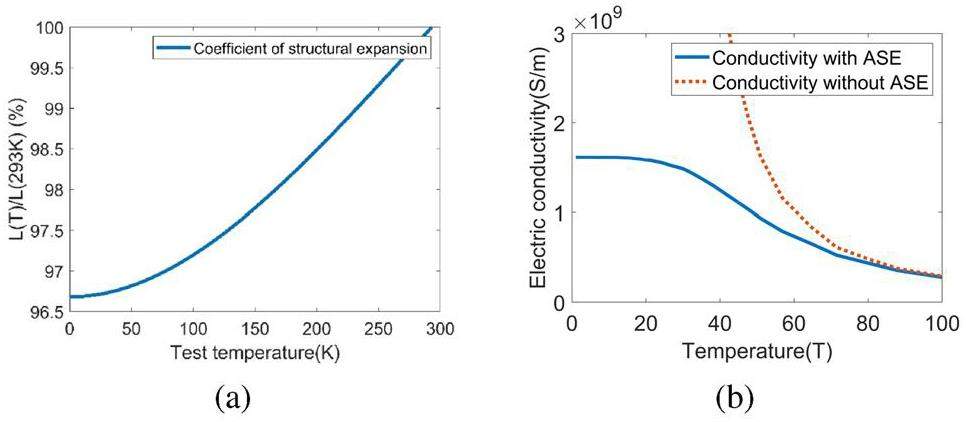

Considering that the conductivity of Cu also changes significantly with temperature, its relationship with the anomalous skin effect(ASE) [53] is calculated in Fig. 17. As the temperature decreases from 293 K to 40 K, the coefficient of thermal expansion decreases, whereas the frequency increases from 5693.51 MHz to 5712 MHz. The quality factor, shunt impedance, and peak RF power can be obtained with the electrical conductivity below 40 K. The parameters of the 2.6-cell electron gun are presented in Fig. 17 and Table 3.

| Condition | Room | Cryogenic |

|---|---|---|

| Working mode (MHz) | 5693.51 | 5712 |

| Q0 | 11473 | 52621 |

| Ez, cathode (MV/m) | 200 | 200 |

| Emax /Eacc | 88.59% | |

| Peak RF power (MW) | 17.244 | 3.761 |

| Max Sc (W/μm2) | 4.837 | |

| RF pulse length (μs) | 2 | 2 |

| Maximum RF pulse heating (K) | 19.98 | 4.85 |

Cryostat Considerations

To operate the gun in cryogenic state, a stable cryostat is required to maintain the gun structure at 40 K. Power was transmitted to the 2.6-cell electron gun through a T-shaped waveguide connected to the RF power source. The vacuum requirements of the cryogenic platform are 1×10-6 Pa at room temperature and 1×10-7 Pa at cryogenic temperatures, which can be provided by molecular and ion pumps. The engineering diagram and cryostat design of the 2.6-cell electron gun are illustrated in Fig. 18. In the near future, a 2.6-cell gun will be manufactured and tested on a low-temperature platform.

Conclusion

To provide electron beams with higher brightness for subsequent upgrades of the SXFEL, a cryogenic electron gun operating at 40 K was designed based on normal conducting technology to achieve a more compact injector while producing high-quality electron beams. In this study, the beam dynamics optimization (500 pC,5 ps at 200 MV/m) of the C-band electron gun was completed with the emittance minimized to 0.33mmmrad, and the beam length reached 0.47 mm. The structure of the cathode cell in the TM02 mode was exploited and adopted. In the RF design, the Sc parameter was optimized to 4.85 W/m2, and the pulse heating temperature rise was 19.98 K at room temperature. Using the dual-feed scheme and racetrack cavity shape, the intensity of the multipole field introduced by the coupler was reduced to approximately 0.01 %. At this point, the design of the electron gun was basically completed, which provides a theoretical basis for subsequent manufacturing and testing. In addition, research on the suppression of dark current will be conducted.

Development and simulation of a gridded thermionic cathode electron gun for a high-energy photon source

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 39 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01195-2First commissioning results of the coherent scattering and imaging endstation at the shanghai soft x-ray free-electron laser facility

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 33, 114 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01103-0Design of a compact c-band high brightness photoinjector for an ultra-fast electron diffraction

. Chinese Science Bulletin 58, 4577-4581 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-013-6079-5Photoinjector based mev electron microscopy

. 2011, p. 503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-013-6079-5High-brightness photo-injector with standing-wave buncher-based ballistic bunching scheme for inverse compton scattering light source

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 33, 44 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01025-xCommissioning the photocathode radio frequency gun: a candidate electron source for hefei advanced light facility

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 33, 23 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01000-6Generation of short thz bunch trains in a rf photoinjector

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 577, 409-416 (2007).Report on gun conditioning activities at pitz in 2013

. Proc. IPAC 14, 2962-2964 (2014). https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-IPAC2014-THPRO044High-brightness beam technology development for a future dynamic mesoscale materials science capability

. Instruments 3,. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments3040052An ultra-compact x-ray free-electron laser

. New Journal of Physics 22,Status of the sxfel facility

. Applied Sciences 7,.Suppression of microbunching instability in the linac coherent light source

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 7,Laguerre-gaussian mode laser heater for microbunching instability suppression in free-electron lasers

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Advances in bright electron sources

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 907, 209-220 (2018). Advances in Instrumentation and Experimental Methods (Special Issue in Honour of Kai Siegbahn). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.03.019Commissioning the linac coherent light source injector

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 11,Dual feed rf gun design for the lcls

.Design optimization of 3.9 ghz fundamental power coupler for the shine project

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 132 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00959-yA phenomenological model of the fundamental power coupler for a superconducting resonator

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 67 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01215-1Study of rf-asymmetry in photo-injector

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 574, 17-21 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.01.088Emittance growth due to multipole transverse magnetic modes in an rf gun

. Physical Review Special Topics-Accelerators and Beams 14,Recent advancements of rf guns

. Physics Procedia 52, 100-109 (2014). Proceedings of the workshop "Physics and Applications of High Brightness Beams:Towards a Fifth Generation Light Source". https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2014.06.015Thermally induced ultra high cycle fatigue of copper alloys of the high gradient accelerating structures

.. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-3346-4Design of a 162.5 mhz continuous-wave normal-conducting radiofrequency electron gun

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 31, 1-10 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00817-3High gradient experiments with x-band cryogenic copper accelerating cavities

. Physical Review Accelerators and Beams 21,Characterization of cold model cavity of cryocooled c-band 2.6-cell rf gun at 20 k

. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 874,A cool route to the higgs boson and beyond. the cool copper collider

. Journal of Instrumentation 18,Study and design of cryogenic accelerating structure and rf optimization of single cell for sxfel energy upgrading

. Radiation Detection Technology and Methods 6, 367-374 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-022-00341-5Beam dynamics optimization of very-high-frequency gun photoinjector

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 33, 116 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01105-yDesign, fabrication, and testing of an x-band 9-mev standing-wave electron linear accelerator

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 110 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01254-8Fabrication, tuning, and high-gradient testing of an x-band traveling-wave accelerating structure for vigas

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 33, 102 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01086-yDesign, fabrication and cold-test results of a 3.6 cell c-band photocathode rf gun for sxfel. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment

1003,Design of s-band photoinjector with high bunch charge and low emittance based on multi-objective genetic algorithm

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 41 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01183-6Cst studio suite, cst mircowave studio

. https://www.3ds.com/zh-hans/products/simulia/cst-studio-suiteNew local field quantity describing the high gradient limit of accelerating structures

. Physical Review Special Topics-Accelerators and Beams 12,Dark current studies of an l-band normal conducting rf gun

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 1010,Some considerations concerning the transverse deflection of charged particles in radio-frequency fields

. Review of Scientific Instruments 27, 967-967 (1956). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1715427Novel method to measure unloaded quality factor of resonant cavities at room temperature

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 29, 1-7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0383-3Measurement of the cavity-loaded quality factor in superconducting radio-frequency systems with mismatched source impedance

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 123 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01281-5Design optimization and cold rf test of a 2.6-cell cryogenic rf gun

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 97 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00925-8Beam test results of high q cbpm prototype for sxfel

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 28, 51 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0195-xFabrication and cold test of prototype of spatially periodic radio frequency quadrupole focusing linac

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 1-9 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00835-1Design of an efficient collector for the hiaf electron cooling system

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00949-0Simulation and photoelectron track reconstruction of soft x-ray polarimeter

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 67 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00903-0The theory and history of the anomalous skin effect in normal metals

. Physics Reports 288, 291-304 (1997). I.M. Lifshitz and Condensed Matter Theory. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(97)00029-XWen-Cheng Fang and Zhen-Tang Zhao are the editorial board members for Nuclear Science and Techniques and were not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.