Introduction

The prospect of observing neutrinoless double-β (0νββ) decay is of great interest, as it would be the most feasible way to verify the Majorana nature of neutrinos, and thus demonstrate lepton-number violation [1-5]. In addition, the measurement of its half-life can provide access to the scale for the absolute neutrino mass and mass hierarchy, but it requires a reliable description of the underlying nuclear matrix elements (NMEs) governing the 0νββ decay [6, 7]. More practically, accurate values of NME are crucial for concluding a definitive choice and the amount of material required in complicated and expensive ββ-decay experiments. Because 0νββ decay involves unknown neutrino properties, such as the neutrino mass scale, the matrix element cannot be measured. On the other hand, it strongly depends on the underlying nuclear structures of the parent and daughter nuclei; hence, it must be calculated using nuclear structure methods. At present, NMEs obtained by various theoretical approaches differ by a factor of up to three [7, 8]. Therefore, reducing the uncertainty in matrix elements is a crucial goal for the nuclear structure community.

An important factor in diminishing the uncertainty is a better description of the ground-state (g.s.) wave functions for both parent and daughter nuclei. To achieve this goal, there are two main issues that need to be addressed: understanding the many-body correlations and the nucleon-nucleon interactions that are strongly relevant to the 0νββ decay NMEs. For the former issue, it was found that some collective correlations significantly influence the calculations of 0νββ decay matrix elements. In particular, matrix elements were suppressed when the ground states of the parent and daughter nuclei exhibited different intrinsic deformations. This suppression was originally investigated using axial quadrupole collectivity [9-12], and later extended to non-axial quadrupole [13] and octupole correlations [14]. It has also been noticed that the transition operators of ββ decay are sensitive to pairing correlations [11, 12, 15, 16]. The 0νββ decay would be favored if one considers like-particle pairing fluctuations [17], but is remarkably hindered by taking into account of proton-neutron (pn) pairing [18-21]. Thus, fully capturing the interplay among collective degrees of freedom is of particular importance for improving the accuracy of the 0νββ decay NMEs.

To unveil the interplay between collectivity and 0νββ NMEs, we need a nuclear structure method that can be applied to the investigation of 0νββ decay, and is capable of dealing with multiple collective correlations in an explicit way. The nuclear structure methods that are most commonly used in the 0νββ decay matrix-element calculations are the interacting shell model (ISM) [22-30], interacting boson model (IBM) [31-33], quasiparticle random phase approximation (QRPA) [18, 19, 34-43], and generator coordinate method (GCM) [10-14, 17, 20, 44, 45]. Among them, the socalled quantum number projected GCM (PGCM) [13, 44, 45] is appealing because it can treat fluctuations in multiple collective correlations explicitly on the same footing, providing a feasible way to evaluate the interference among different correlations. It has been shown that the inclusion of quadrupole and pn-pairing correlations in GCM calculations [13, 21, 44] significantly diminishes the large deviation in the 0νββ decay NMEs between the previous GCM and SM predictions. This indicates that the GCM approach captures most of the correlations around the Fermi surface, which are important for 0νββ decay.

The other key point is to improve the nucleon-nucleon interaction. To evaluate whether an effective interaction is reasonable for 0νββ NME calculations, it would be of particular interest to study the influence of a specific term on the interaction. It has been shown that the tensor force has a unique and robust effect on the single-particle energies of nuclei throughout the nuclear chart, and hence, changes the occupation of nucleons associated with the shell structure [46, 47]. Consequently, the tensor force interferes with the collective motion of the nucleons. For example, occupying specific orbits would provide a larger deformation-driving effect, inducing enhanced quadrupole collectivity. Changing the level density of single-particle orbits around the Fermi surface strongly affects the pairing correlations. Recently, the tensor force has been found to contribute significantly to the low-lying Gamow-Teller distribution, and hence makes a dramatic improvement in predicting single-β decay half-lives [48]. Therefore, it is very intriguing to evaluate the impact of the tensor force on collective correlations and the resulting effect on 0νββ decay.

To demonstrate the influence of tensor force, the tensor term should be incorporated into the effective interaction in an explicit and separable form. We propose an analysis of the influence of the tensor force on both the collectivity and the 0νββ decay NME for candidate nuclei 124Sn/Te,130Te/Xe, and 136Xe/Ba [5, 49, 50], by applying a PGCM calculation in conjunction with the effective Hamiltonian arising from the monopole-based universal interaction VMU [47] plus a spin-orbit force taken from the M3Y interaction [51]. The

The Model

Owing to the shell closure approximation, the 0νββ decay NME can be computed in terms of the matrix element of a two-body transition operator between the g.s. wave functions of the parent and daughter nuclei. Our wave functions were modified at short distances using a Jastrow-type short-range correlation (SRC) function in the parameterization of CD-Bonn [38]. A more detailed expression of the matrix element can be found in Ref. [18]. These many-body wave functions, which play a crucial role in the NME calculation, are provided by the GCM. We employed a shell-model effective Hamiltonian (Heff) in a valence space whose size is free to choose. In an isospin scheme, Heff can be written as the sum of one- and two-body operators:

With the effective Hamiltonian, the first step is to generate a set of reference states

We further solved the constrained Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov (HFB) equations for the Hamiltonian with linear constraints:

Once we obtain a set of HFB vacua constrained to various collective correlations, the GCM state can be composed of a linear superposition of the projected HFB vacua, given by

Effective Hamiltonian

The nuclear interaction V can be divided into the central part (VC), spin-orbit part (VLS), and tensor part (VT), as follows:

The monopole-based universal interaction, VMU [47], and the M3Y type spin-orbit interaction [51] (VMU+LS) are used to construct the effective Hamiltonian in the present work. VMU contains a central force in the Gaussian form (VC) and a bare

Results and discussion

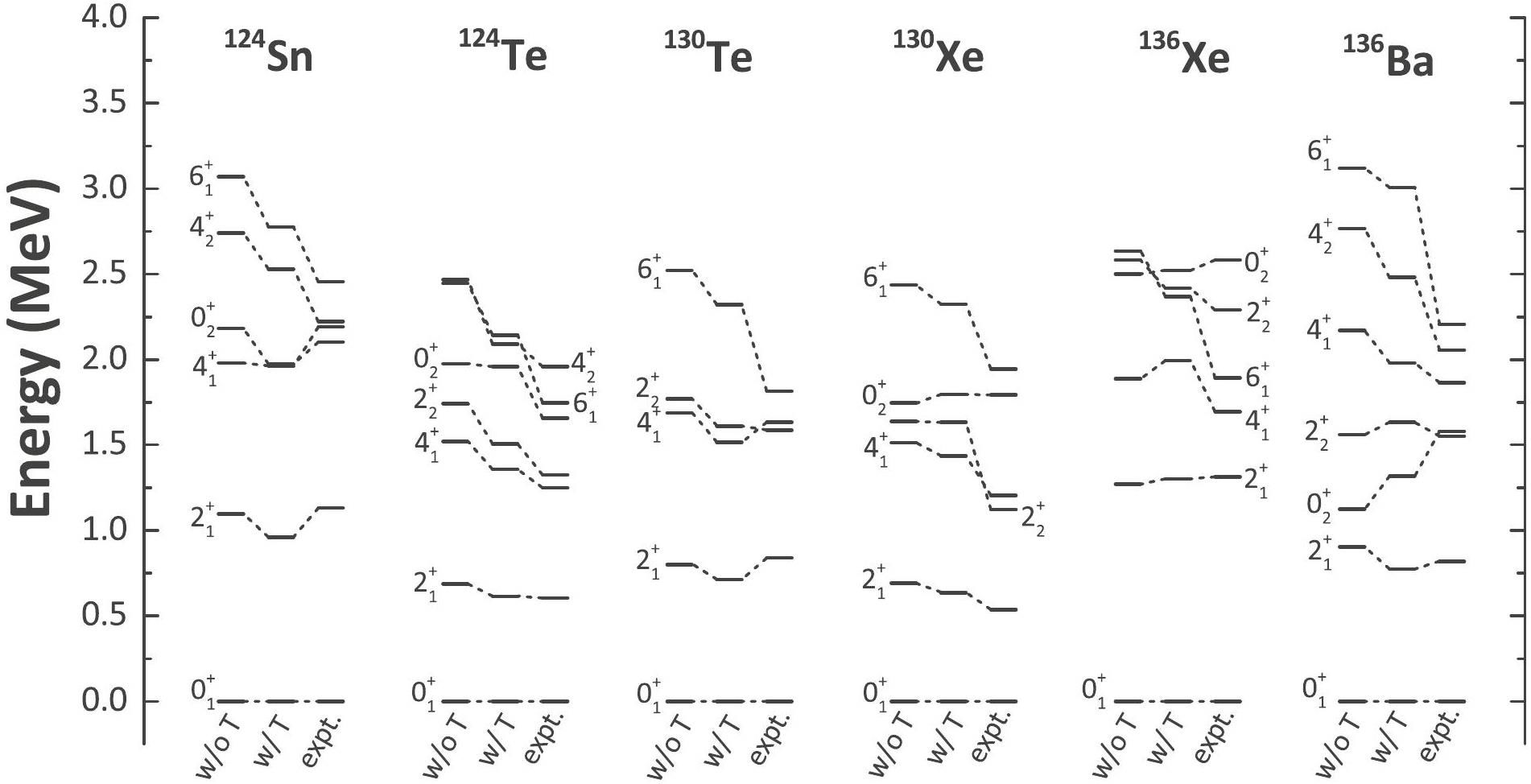

An important probe for deformation and associated collectivity is the γ-ray spectroscopy of the nucleus. Figure 1 shows the low-lying level spectra of 124Sn, 124Te, 130Te, 130Xe, 136Xe, and 136Ba obtained with or without the tensor term compared to the experimental data [55]. Although our calculated 6+ states are overestimated, most of the low-lying states obtained by our calculations, which include the tensor term, are in reasonable agreement with the experimental spectra. The overestimation of higher spin states could be due to the fact that the GCM calculations exclude vibrational motion and broken-pair excitation, while these two excitation modes may significantly lower the excited states, especially in the nearly spherical and weakly deformed nuclei. In general, the inclusion of the tensor term significantly improved the calculated spectra. The

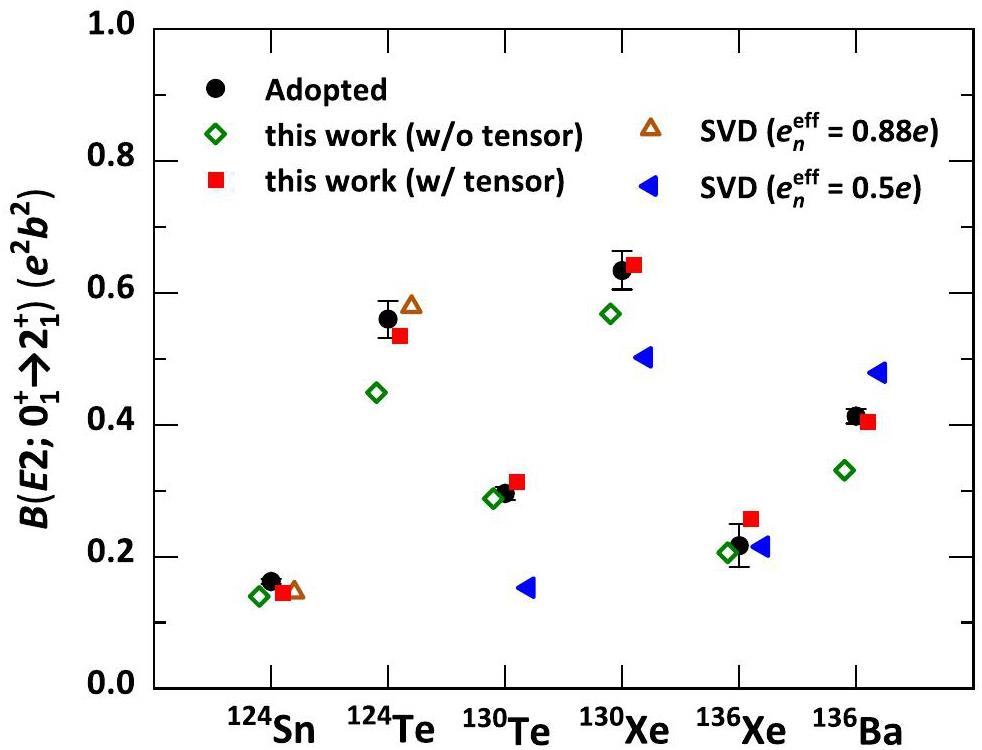

The reduced E2 transition probability,

Similar to low-lying γ-ray spectroscopy, incorporating the tensor force results in the enhancement of the quadrupole collective correlation and hence provides a better agreement with the experimentally adopted values of B(E2). It should be noted that the increase in quadrupole collectivity is more significant in daughter nuclei, that is, 124Te, 130Xe, and 136Ba. This leads to a larger deviation in the intrinsic deformation between the parent and daughter nuclei. The underlying physics will be discussed in more detail later in this paper.

We then computed the values of 0νββ decay matrix elements of 124Sn, 130Te, and 136Xe. In closure approximation, the 0νββ matrix element of a two-body transition operator is computed between the initial and final ground states. Assuming an exchange of a light Majorana neutrino with the usual left-handed currents, the matrix element is [18]

The results are listed in Table 1, where the Gamow-Teller, Fermi, and tensor contributions are shown. While the Fermi parts remain almost unchanged, the Gamow-Teller parts are drastically suppressed when the tensor force is considered. The total matrix elements given by the calculation, including the tensor force, are approximately 26 to 40% smaller than those of the calculation excluding the tensor force.

| M0ν | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 124Sn | w/o tensor | 3.56 | -0.64 | -0.061 | 3.91 |

| w/ tensor | 2.65 | -0.64 | -0.020 | 3.04 | |

| 130Te | w/o tensor | 4.29 | -0.75 | -0.064 | 4.70 |

| w/ tensor | 3.33 | -0.65 | -0.015 | 3.73 | |

| 136Xe | w/o tensor | 3.26 | -0.44 | -0.046 | 3.49 |

| w/ tensor | 2.17 | -0.50 | -0.009 | 2.48 |

The tensor part of the NME, although suppressed if the tensor force is included, is negligibly small. This is in accordance with other studies that used different nuclear structural methods [23, 33, 42]. Therefore, tensor contributions were neglected [17, 19, 37]. The small tensor contributions in the NME are mainly attributed to the fact that the tensor part is induced by high-order currents. Thus, the two-body matrix elements of the tensor 0νββ decay operator are much smaller than those of Gamow-Teller and Fermi matrices. Because the value is small and subtle, it is difficult to trace the origin of these numerical changes in tensor NME. The interference between the collective correlations and tensor contributions in the NME remains unclear. Further study of the tensor part of the NME is required in the future, but its negligible contribution may not affect the conclusions we present in this work.

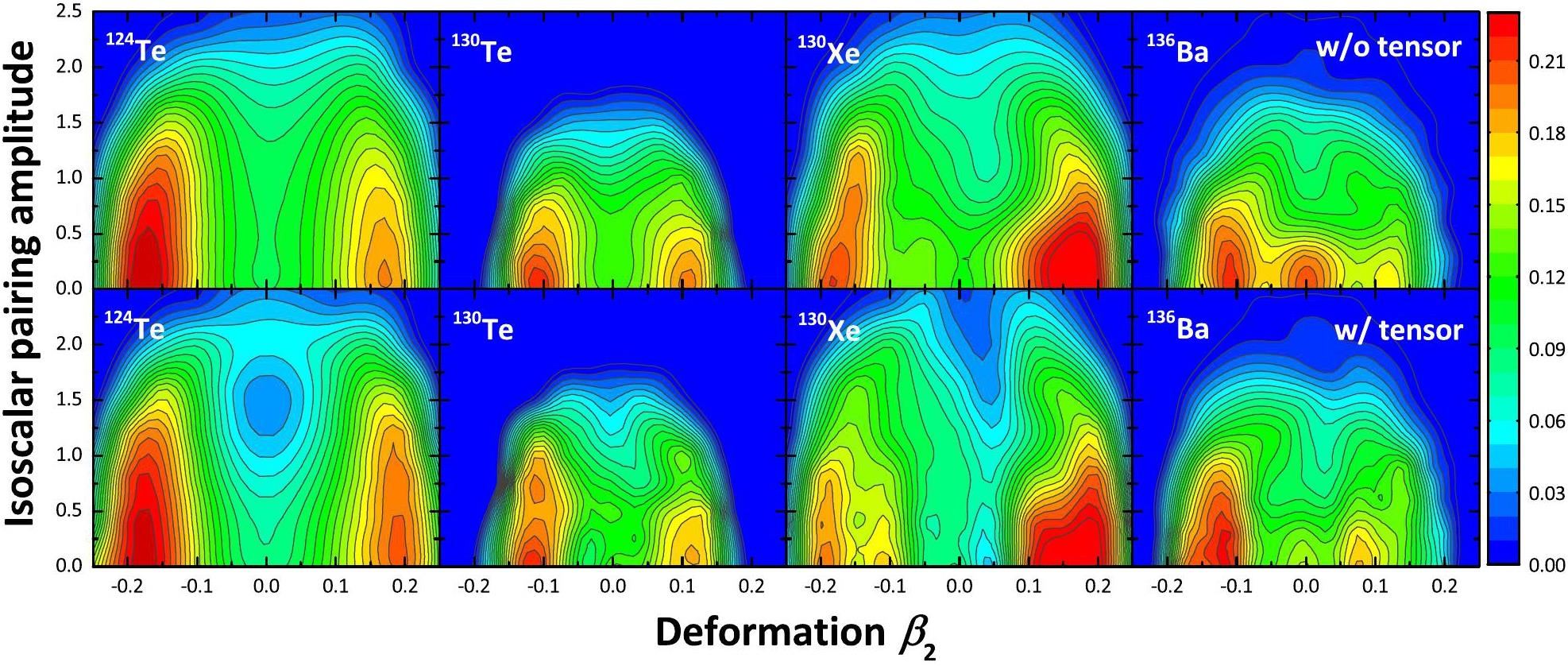

The influence of collective correlations on 0νββ nuclear matrix elements can be evaluated by the collective wave functions of the parent and daughter nuclei. The so-called collective wave functions are defined to account for the probability density of finding the state with a given expectation values of collective operators in Eq. (3). The detailed expression for the collective wave functions is given in the Eq. (18-19) of Ref. [53]. Note that the sum of collective wave functions is normalized to 1. When the probability density of finding the state with the specific deformation and isoscalar pairing amplitude increases, probability density of finding the state elsewhere would be suppressed consequently. Figure 3 shows the square of the collective wave functions against quadrupole deformation β2 and isoscalar pn pairing amplitude. Since the cases 124Sn and 136Xe lack valence protons and valence neutron holes, respectively, and hence cannot change pn pairing, the squares of the collective wave functions of these two nuclei are not displayed. It can be seen that the largest peaks of collective wave functions in these nuclei are pushed, to some different extent, to the region with larger quadrupole deformations and isoscalar pairing amplitude if the tensor force is incorporated. The most apparent case is 136Ba, where a subpeak appears at the sphericity in the calculation excluding the tensor force, but vanishes when we take the tensor force into consideration. Another interesting case occurs in 124Te. When the tensor force is included, the increase of the collective wave functions with large quadrupole deformation and larger isoscalar pairing forms a dip in the region with near spherical deformation and intermediate isoscalar pairing. Since 124Sn and 136Xe keep their characteristics of sphericity owing to the Z=50 and N=82 shell closure, respectively, the difference of deformations between all the parent and their daughter nuclei are enlarged. In addition, the collective wave functions obtained with inclusion of the tensor force spread more widely along with the isoscalar pairing, indicating stronger isoscalar pairing fluctuations. The effects of both quadrupole deformation and isoscalar pairing therefore strongly hinder the 0νββ matrix elements.

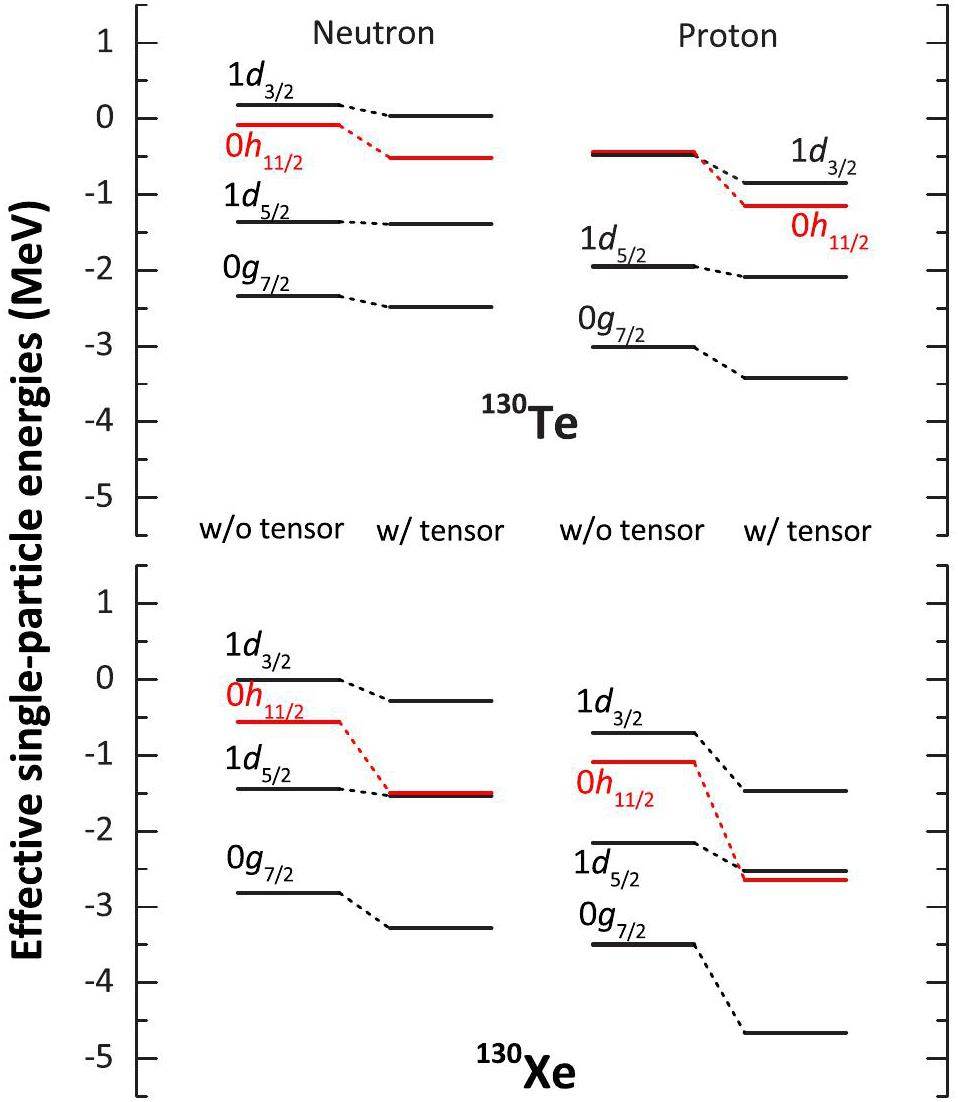

To unveil the underlying connection amongst tensor force, collectivity, and nuclear matrix elements for 0νββ decay, the HFB effective single-particle energies (ESPEs) for valence neutron and proton orbits in 130Te and 130Xe are exhibited in Fig. 4. In this work, the HFB single-particle energies are obtained by diagonalizing the HF Hamiltonian h in the HFB equation, which is constructed with the density matrix of the HFB solution. For simplicity, only the ESPEs at spherical shapes and with isoscalar pairing amplitude ϕ=0 are shown. Note that the ESPEs are plotted relative to the 2s1/2 orbits. The ESPE is changed by the tensor force itself, as well as by re-adjusting the one-body part of the effective interaction due to the exclusion of tensor force. By looking at relative ESPEs, one can partly remove the common change from re-adjusting the one-body part of the effective interaction and thus can check the tensor effect more directly.

Figure 4 shows that owing to the inclusion of the tensor force, all neutron (proton) valence orbits are lowered with respect to the neutron (proton) 2s1/2 orbit. Among them, the neutron and proton 0h11/2 orbits were shifted more significantly. Of particular interest, the neutron and proton 0h11/2 orbits were suppressed more drastically in 130Xe than in 130Te. It is a complex many-body effect resulting from monopole interactions produced by the tensor force among all valence nucleon orbits. According to the rules discussed in Refs. [46, 66], the monopole interaction produced by the tensor force between proton 0g7/2 and neutron 0h11/2 orbit is attractive. As two more protons in 130Xe mainly occupy the proton 0g7/2 orbit, the neutron 0h11/2 orbit decreases more remarkably than that in 130Te. Meanwhile, the monopole interactions between the proton 0h11/2 and neutron 0h11/2, and between the proton 0h11/2 and neutron 1d5/2 orbits are both repulsive. Because the two neutrons are mainly removed from the neutron 0h11/2 and 1d5/2 orbits in 130Xe when compared to 130Te, the repulsive effects are weakened, and thus the proton 0h11/2 orbit is pulled down more substantially. Similar results were observed for the 124Sn/Te and 136Xe/Ba.

For all investigated nuclei, the suppression of the proton 0h11/2 orbit lifts the proton Fermi surface, whereas the lowering of the neutron 0h11/2 orbit pulls the neutron Fermi surface down. The Fermi surfaces of both protons and neutrons lie closer to the 0h11/2 midshell if the tensor force is included. It should be noted that high-j orbits are expected to exhibit a large deformation-driving effect [67, 68]. Because the lowering of 0h11/2 orbit is more significant in the daughter nuclei of 0νββ decays, the deformation-driving effect is larger, resulting in a more remarkable enhancement of the quadrupole correlations in these nuclei.

In addition, the shift of the valence nucleon orbits induced by the tensor force would adequately affect the nucleon occupancies. The change in the ground-state nucleon occupancies in the 0νββ decays provides an unquestionably important constraint on the calculation of the 0νββ matrix element, as it directly determines which neutrons decay, which protons are created in the decay, and how their configurations are re-arranged [69].

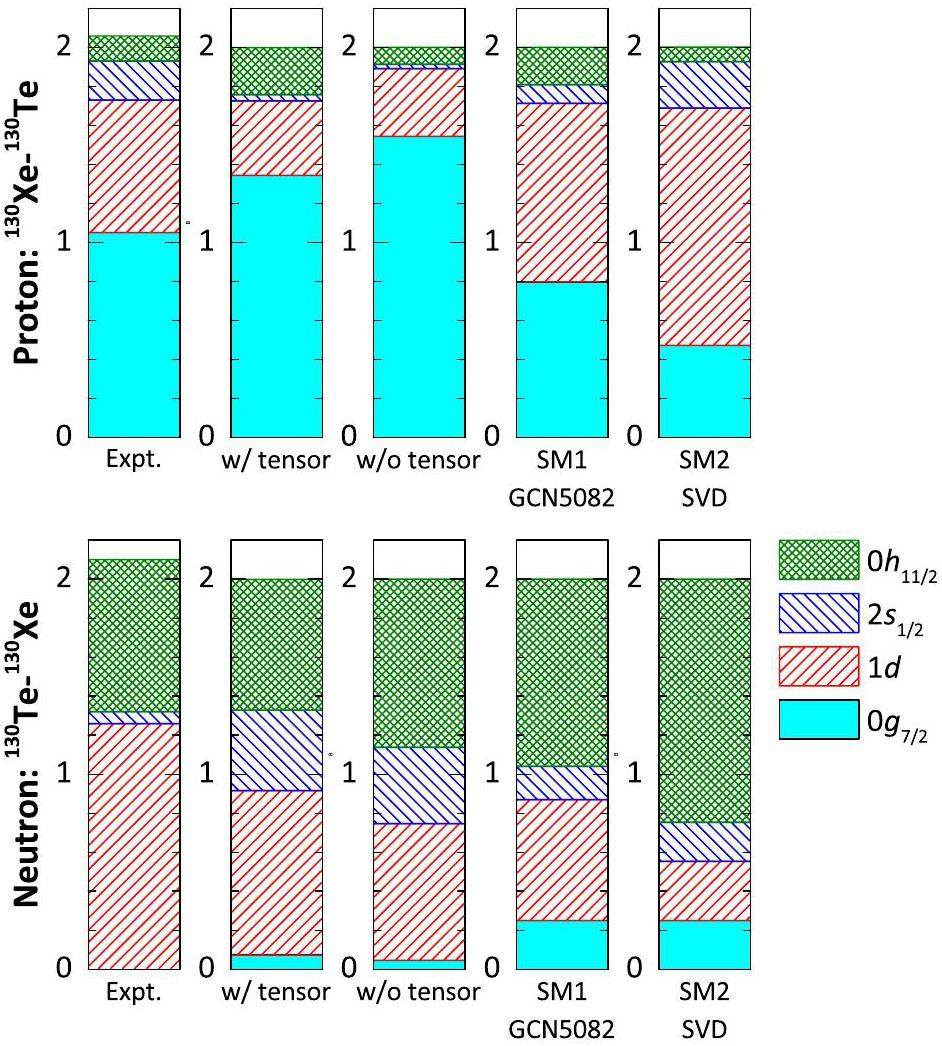

Recently, the proton occupancies and neutron vacancies of 130Te and 130Xe have been probed in single-nucleon transfer reactions to a level of precision corresponding to a few tenths of that of a nucleon [70, 71]. The total neutron vacancies measured are 4.16 for 130Te and 6.26 for 130Xe [70], the total proton occupancies are 1.89 for 130Te and 3.95 for 130Xe [71], which gives the total change in proton occupancies and neutron vacancies of 2.06 and 2.10, respectively. Note that, in a realistic nucleus, nucleons may occupy orbits above the valence space or unoccupied orbits frozen in the core. Therefore, the measured total proton occupancy and neutron vacancy slightly deviate from the expected values with respect to the valence space. Figure 5 shows our calculations describing the change in proton occupancies and neutron vacancies in the 0νββ decay of 130Te→130Xe system, compared to experimental data [70, 71] and two shell-model calculations using the GCN5082 interaction [23] and the SVD interaction [27]. Notwithstanding the notable discrepancies from the experimental values, our calculation qualitatively reproduces the two most important contributions of the valence orbits for the nucleons that switch from neutrons to protons. The largest change in proton occupancies occurs in the 0g7/2 orbit, and the second largest change occurs in the 1d orbit. Meanwhile, the largest change in neutron vacancies appears in the 1d orbit, and the second largest change is in the 0h11/2 orbit. Note that the inclusion of the tensor force improves the description of the change in occupation of nucleons. As shown in Fig. 5, our calculation that excludes the tensor force overestimates the change in the neutron vacancy of the 0h11/2 orbit. Taking into account the tensor force, the neutron 0h11/2 orbit is pulled down substantially and merges into the 1d5/2 subshell. It reduces the change of neutron vacancies in the 0h11/2 orbit but enhances the change in the 1d5/2 orbit, which is in accord with the measurement.

In Table 2, the calculated NMEs for the 0νββ decay of 124Sn → 124Te, 130Te → 130Xe, and 136Xe → 136Ba are compared with those given by ISM [23, 27, 28], QRPA [19, 40, 42], IBM2 [33], GCM in conjunction with the non-relativistic energy density functional (NR-EDF) [17], and relativistic energy density functional (R-EDF) [10]. In general, our M0ν’s are comparable with those obtained with the ISM, the QRPA from the Tübingen and Jyväskylä groups, and the IBM2, while the NR-EDF and R-EDF provide much larger values. The significantly large NMEs can be attributed to the lack of pn pairing correlation in the density energy functionals, either non-relativistic Gongny D1S [17] or relativistic PC-PK1 [10]. As previously mentioned, the pn pairing fluctuation would remarkably suppress the NMEs of 0νββ decays. The QRPA from the Chapel Hill group exhibited a noticeably small NME of 130Te → 130Xe decay. This is because their QRPA calculation was based on a single HFB minimum, which was spherical for 130Te and prolate for 130Xe. The sharp deformation difference between the parent and daughter nuclei suppressed the suppression of 0νββ NME. Our PGCM calculations adequately addressed the fluctuations in shape and pn pairing on the same footing. This would fix the above issues and provide a reasonable description of the 0νββ NMEs.

| Models | This work | ISM (St-Ma) | ISM (Mi) | QRPA (Tu) | QRPA (Jy) | QRPA (Ch) | IBM2 | NR-EDF | R-EDF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gA | 1.254 | 1.25 | 1.254 | 1.254 | 1.26 | 1.25 | 1.269 | 1.25 | 1.254 |

| 124Sn → 124Te | 3.04 | 2.62 | 2.00/2.15 | 2.56/2.91 | 5.30 | 3.19 | 5.79 | 4.33 | |

| 130Te → 130Xe | 3.73 | 2.65 | 1.79/1.93 | 3.89/4.37 | 4.00 | 1.37/1.38 | 3.70 | 6.41 | 4.98 |

| 136Xe → 136Ba | 2.48 | 2.19 | 1.63/1.76 | 2.18/2.46 | 2.91 | 1.55/1.68 | 3.05 | 4.77 | 4.32 |

Finally, it should be mentioned that we only discuss the NME of 0νββ decay from the ground-state of the parent nucleus to that of the daughter nucleus in this work. Actually, the decay to the low-lying excited states of the daughter nucleus should also be considered if it is allowed energetically. The NME of this process is strongly quenched by the phase-space factor in the standard light left-handed Majorana neutrino exchange mechanism [72, 73]. However, a considerable contribution to the NME from this process in the non-standard mechanism cannot be ruled out. Further study of 0νββ decay of NME to the lowest

Summary

An analysis of the influence of the monopole effect originating from the tensor force on both the collectivity and the nuclear matrix element of the 0νββ decay is presented for candidate isotopes 124Sn/Te,130Te/Xe, and 136Xe/Ba, using the generator-coordinate method with a shell-model effective interaction. We employ an effective Hamiltonian written in terms of the monopole-based universal interaction VMU plus a spin-orbit force taken from the M3Y interaction. The so-called monopole-based universal interaction consists of central and tensor forces explicitly, and hence, could clarify the effect of the tensor force by including or excluding the tensor-force term. The monopole effect arising from the tensor force is shown to have a significant influence on the quadrupole collectivity, nucleon occupancy, and 0νββ matrix element, which could be interpreted by the change in the shell structure owing to the novel feature of the tensor force. A better understanding and possible refinement of the tensor force would thus be of particular importance in reducing the theoretical uncertainty in the calculation of 0νββ nuclear matrix elements.

Double beta decay, Majorana neutrinos, and neutrino mass

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 481-516 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.80.481Gamma-, neutron-, and muon-induced environmental background simulations for 100Mo-based bolometric double-beta decay experiment at Jinping Underground Laboratory

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 135 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01299-9NνDEx-100 conceptual design report

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01360-7Sensitivity challenge of the next-generation bolometric double-beta decay experiment

. Research 7, 0569 (2024). https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0569Search for Majorana neutrinos exploiting millikelvin cryogenics with CUORE

. Nature 604, 53--58 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04497-4Neutrinoless ββ decay mediated by the exchange of light and heavy neutrinos: The role of nuclear structure correlations

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 45,Status and future of nuclear matrix elements for neutrinoless double-beta decay: a review

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80,Nuclear structure and double beta decay

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 39,Neutrinoless double-β decay of deformed nuclei within quasiparticle random-phase approximation with a realistic interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Systematic study of nuclear matrix elements in neutrinoless double-β decay with a beyond-mean-field covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Energy Density Functional Study of Nuclear Matrix Elements for Neutrinoless ββ Decay

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,Neutrinoless ββ decay nuclear matrix elements in an isotopic chain

. Phys. Lett. B 719, 174 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.12.063Neutrinoless double-β decay matrix elements in large shell-model spaces with the generator-coordinate method

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Octupole correlations in low-lying states of 150Nd and 150Sm and their impact on neutrinoless double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Suppression of the two-neutrino double-beta decay by nuclear-structure effects

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 3148 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.57.3148Nuclear structure effects in double-beta decay

. Phys. Rev. C 37, 731-746 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.37.731Shape and Pairing Fluctuation Effects on Neutrinoless Double Beta Decay Nuclear Matrix Elements

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111,Anatomy of the 0νββ nuclear matrix elements

. Phys. Rev. C 77,Large-scale calculations of the double-β decay of 76Ge, 130Te, 136Xe, and 150Nd in the deformed self-consistent Skyrme quasiparticle random-phase approximation

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Proton-neutron pairing amplitude as a generator coordinate for double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Testing the importance of collective correlations in neutrinoless ββ decay

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Influence of Pairing on the Nuclear Matrix Elements of the Neutrinoless ββ Decays

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100,Disassembling the nuclear matrix elements of the neutrinoless ββ decay

. Nucl. Phys. A 818, 139 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.12.005Shell model analysis of the neutrinoless double-β decay of 48Ca

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Shell model analysis of competing contributions to the double-β decay of 48Ca

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Shell-Model Analysis of the 136Xe Double Beta Decay Nuclear Matrix Elements

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Shell model studies of the 130Te neutrinoless double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Shell model predictions for 124Sn double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Large-Scale Shell-Model Analysis of the Neutrinoless ββ Decay of 48Ca

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116,Shell-model calculation of neutrinoless double-β decay of 76Ge

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Limits on Neutrino Masses from Neutrinoless Double-β Decay

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109,Nuclear matrix elements for double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 87,0νββ and 2νββ nuclear matrix elements in the interacting boson model with isospin restoration

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Additional nucleon current contributions to neutrinoless double β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 60,Uncertainty in the 0νββ decay nuclear matrix elements

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Short-range correlations and neutrinoless double beta decay

. Phys. Lett. B 647, 128 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2007.01.054Improved short-range correlations and 0νββ nuclear matrix elements of 76Ge and 82Se

. Phys. Rev. C 75,0νββ-decay nuclear matrix elements with self-consistent short-range correlation

. Phys. Rev. C 79,0νββ nuclear matrix elements and the occupancy of individual orbits

. Phys. Rev. C 79,0νββ and 2νββ nuclear matrix elements, quasiparticle random-phase approximation, and isospin symmetry restoration

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Arbitrary mass Majorana neutrinos in neutrinoless double beta decay

. Phys. Rev. D 90,Nuclear matrix elements for 0νββ decays with light or heavy Majorana-neutrino exchange

. Phys. Rev. C 91,0νββ-decay nuclear matrix element for light and heavy neutrino mass mechanisms from deformed quasiparticle random-phase approximation calculations for 76Ge, 82Se, 130Te, 136Xe, and 150Nd with isospin restoration

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Neutrinoless double-β decay of 124Sn, 130Te, and 136Xe in the Hamiltonian-based generator-coordinate method

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Union of rotational and vibrational modes in generator-coordinate-type calculations, with application to neutrinoless double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Evolution of nuclear shells due to the tensor force

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95,Novel Features of Nuclear Forces and Shell Evolution in Exotic Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,Impact of tensor force on β decay of magic and semimagic nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Determination of double beta decay half-life of 136Xe with the PandaX-4T natural xenon detector

. Research 2022,PandaX-xT–A deep underground multi-ten-tonne liquid xenon observatory

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 68,Interactions for inelastic scattering derived from realistic potentials

. Nucl. Phys. A 284, 399 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(77)90392-XTriaxial angular momentum projection and configuration mixing calculations with the Gogny force

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Configuration mixing of angular-momentum-projected triaxial relativistic mean-field wave functions

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Nudat 3.0

,” https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/nudat3/.Shell-model study of boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes with a monopole-based universal interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Shape transitions in exotic Si and S isotopes and tensor-force-driven Jahn-Teller effect

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Large-scale shell-model calculations for unnatural-parity high-spin states in neutron-rich Cr and Fe isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Isomerism in the “south-east” of 132Sn and a predicted neutron-decaying isomer in 129Pd

. Phys. Lett. B 762, 237 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.09.030Shell-model study on spectroscopic properties in the region “south” of 208Pb

. Phys. Rev. C 106,New α-emitting isotope 214U and abnormal enhancement of alpha-particle clustering in lightest uranium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,New isotope 207Th and odd-even staggering in α-decay energies for nuclei with Z > 82 and N < 126

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Shell-model explanation on some newly discovered isomers

. EPJ Web Conf. 239, 04002 (2020). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.37.2019CNPC18Recent progress in configuration-interaction shell model

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 32, 12 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301323300035Tables of E2 transition probabilities from the first 2+ states in even-even nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 107, 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.10.001Novel Features of Nuclear Forces and Shell Evolution in Exotic Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,Collective oblate band in 131La due to the rotational alignment of h11/2 neutrons

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 984 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.984Deformation-driving properties of the vi132[660]12+ intruder orbital for A≃130 nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 42 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.61.42Nuclear structure relevant to neutrinoless double β decay: 76Ge and 76Se

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100,Valence neutron properties relevant to the neutrinoless double-β decay of 130Te

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Change of nuclear configurations in the neutrinoless double-β decay of 130Te→130 and 136Xe→136 Ba

. Phys. Rev. C 93,0+→2+ neutrinoless ββ decay of 76Ge

. Nucl. Phys. A 484, 635 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(88)90313-2Nuclear matrix elements for the 0νββ(0+ → 2+) decay of 76Ge within the two-nucleon mechanism

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Cen-Xi Yuan is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.