Introduction

Nucleon clustering is fundamental in the study of nuclear structures and reactions [1-4]. In particular, the clustering effect plays a crucial role in understanding cluster radioactivity and α decay in both heavy and superheavy nuclei. Although α decay has been observed in laboratories for over a century, recent experiments have directly demonstrated the formation of α clusters at the surface of heavy nuclei using

Studies on few-body correlations in nuclear matter (medium) have demonstrated that the α correlation is highly sensitive to nucleon density, owing to the Pauli exclusion principle [4, 11-16]. This α correlation becomes prominent only when the medium density is below a critical threshold of approximately one-fifth the saturation density, known as the Mott density. Above this density threshold, α correlation is suppressed owing to the antisymmetrization of the many-body wave function for the entire fermion system [12, 16].

Consequently, the formation of α clusters in a finite nucleus is confined to the nuclear surface, where nucleon density is relatively low. As the α cluster moves from the surface toward the residual daughter nucleus, it experiences increasing Pauli blocking from the surrounding nucleons (see Eq. (45) in Ref [12]). This Pauli blocking weakens the binding of the α-like quartet (α correlation), resulting in the expansion of the cluster, a phenomenon referred to as a medium effect. When the medium density exceeds the Mott density, the α correlation vanishes and the quartet transitions from a bound α-cluster state to single-nucleon states [12, 13, 16]. Therefore, α clusters rarely form in the interior of heavy nuclei.

Based on the aforementioned experimental and theoretical findings, the α cluster in the α-daughter configuration of an α emitter is expected to experience a pocket-like potential at the nuclear surface during its center-of-mass motion [12, 17-20]. Our recent study investigated the correlation between this pocket structure and the α-clustering effect [21]. We developed a pocket-type dynamical double-folding potential that incorporates both the surface-medium effect and interior Pauli repulsion for α decay. The improved α-nucleus potential results in a surface pocket geometry beyond the critical radius that marks the Mott density, thereby concentrating the α-cluster wave function at the nuclear surface beyond this radius in a self-consistent manner.

In this study, we assess the reliability of the pocket-type DDFP model further by extending the calculations of α-decay half-lives to a broader range of even-even nuclei with

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we present the theoretical framework of the pocket-type DDFP and half-life calculations. In Sect. 3, we present the results and discuss the α-nucleus potential, α-decay half-lives, and nuclear charge radii. Finally, a summary is provided in the last section.

Theoretical framework

In the cluster models for α decay, the relative motion between the α cluster and daughter nucleus is described as two-body dynamics. The α cluster interacts with the daughter nucleus via the α-nucleus potential, which can be expanded as

r1 and r2 are the intrinsic coordinates of the daughter nucleus and the α-cluster, respectively, and s=R+r2-r1 is the vector between the interacting nucleons. A notable distinction in the DDFP formalism, compared with the conventional double-folding formalism, is the incorporation of the surface medium effect within the dynamical density distribution of the α cluster

The effective nucleon-nucleon (NN) interaction VN is crucial for double-folding potentials because it significantly influences the geometry of the derived potential. It was observed that strong repulsive behavior for VN in the region of large-density overlaps is essential for simulating the Pauli blocking experienced by the α cluster, which leads to a pocket-type potential [17, 21, 29]. Here, we adopt the density-dependent Migdal NN interaction [21, 30, 31]

The α decay width was calculated using a two-potential approach (TPA) [33]. Within the TPA framework, the tunneling problem is divided into bound-state and scattering-state problems. The decay width is expressed in terms of the bound-state wave function

Finally, the decay half-life was calculated using the following equation:

Results and discussions

The pocket-type DDFP and the α-decay half-life calculations

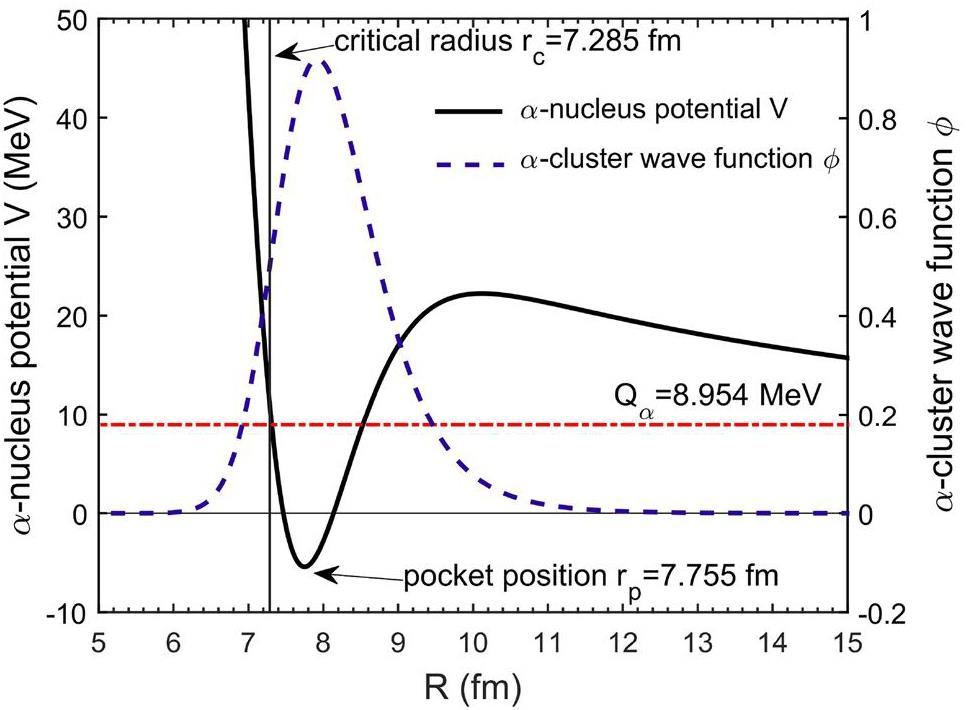

As mentioned in Sect. 1, α-clustering primarily occurs at the surface of heavy nuclei where the nucleon density is below the Mott density. This is illustrated by the pocket-type DDFP, as depicted in Fig. 1. A pocket-like geometry is formed in the surface region beyond the critical radius rc which corresponds to the Mott density. This feature enables the formation of a quasi-bound state for the α-daughter system, and the α cluster is located at the pocket center. Conversely, within the internal region (R<rc), Pauli repulsion suppresses the α correlation, preventing the formation of the α-cluster state. Consequently, the strongly repulsive core in the α-nucleus potential effectively inhibits the α cluster, as illustrated by the amplitude of the α-cluster wave function. The first classical turning point is close to the critical radius rc. This classical turning point marks the boundary of the classical forbidden region, within which the amplitude of the α-cluster wave function undergoes rapidly reduction. A comparable reduction in α-clustering is expected when the medium density surpasses the Mott density; specifically, when the cluster moves into the interior of the daughter nucleus, crossing the critical radius. Therefore, the positions of the first classical turning point and the critical radius are expected to be close to each other. Our calculations indicate that the average distance between these two positions was 0.085 fm for the 129 α emitters studied, reinforcing the universality of this phenomenon.

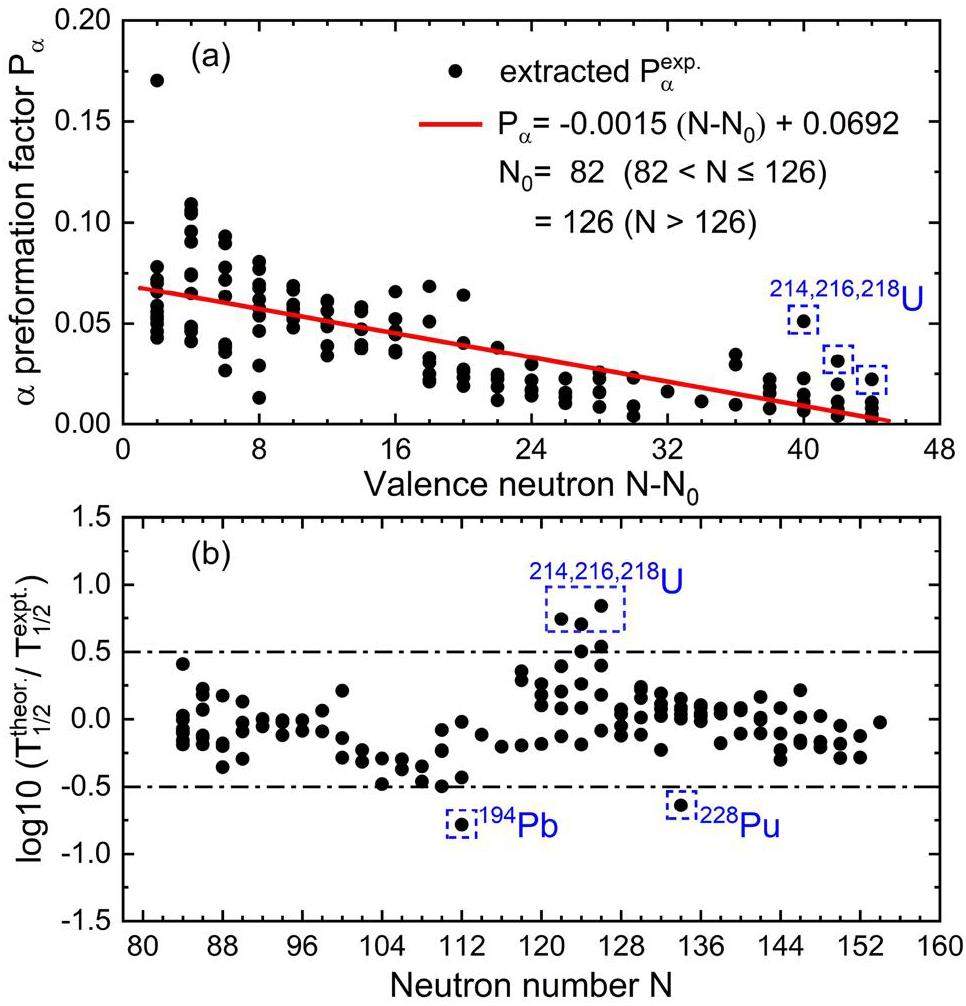

Utilizing this pocket-type DDFP model, we investigated the ground state-to-ground state α transitions in even-even nuclei ranging from Nd to Cf. To calculate the decay half-lives using Eq. (9), the Pα factor is required as a theoretical input. Because the Pα factor is strongly correlated with the shell structure, a precise description of Pα during the shell evolution is crucial for reliable half-life calculations. However, a direct evaluation of the exact Pα within a microscopic formalism is challenging because of the complexity of many-body problems. Alternatively, the value of Pα can be estimated phenomenologically from well-established Pα systematics derived from experimental half-lives

In Fig. 2(b), the deviations between the theoretical and experimental half-lives are plotted (denoted by black circles) on a logarithmic scale as a function of the neutron number of the parent nucleus. The agreement between the theoretical and experimental results was systematically evaluated using the average deviation, defined as

In addition to the ground-state-to-ground-state α decay discussed above, testing the performance of the proposed model in estimating the α-decay half-lives between the excited states would be valuable. For instance, we calculated the half-life of the favored α transition from the first isomeric state of 139Po

Nuclear charge radii estimated by the pocket-type DDFP model

Within the double-folding framework, the density distribution of the daughter nucleus is involved in constructing the α-nucleus potential. Consequently, deducing the nuclear charge radius of the daughter nucleus from its density distribution is feasible once the α-nucleus potential is determined using experimental decay data. For instance, in Ref. [22, 23], the charge radii of the daughter nuclei were determined using both the experimental half-lives and decay energies within the framework of a generalized density-dependent cluster model (GDDCM). In an extention of this approach, Ref. [24] improved the GDDCM (labeled GDDCM*) by considering the neutron skin structure, differences between proton and neutron density distributions, and a more refined α preformation factor. This modification provides a better description for the charge radii. To a certain extent, the accuracy of the deduced charge radii serves as an additional test of the effectiveness of the model in describing α-nucleus interactions.

As described in Sect. 2, the diffuseness parameter a in the density distribution of the daughter nucleus is determined by ensuring that the pocket-type DDFP, within the TPA framework, can support a bound state with its eigenvalue matching the experimental α-decay energy. Therefore, the pocket potential embodies both α-decay dynamics and information from the decay energy. This is linked to the density distribution and the surface diffuseness property a of the daughter nucleus through a double-folding procedure. Once the value of a is determined in the calculation, we obtain not only the α-nucleus potential for half-life calculations, but also the density distribution of daughter nuclei. Therefore, the RMS charge radius of the daughter nucleus can be calculated as follows:

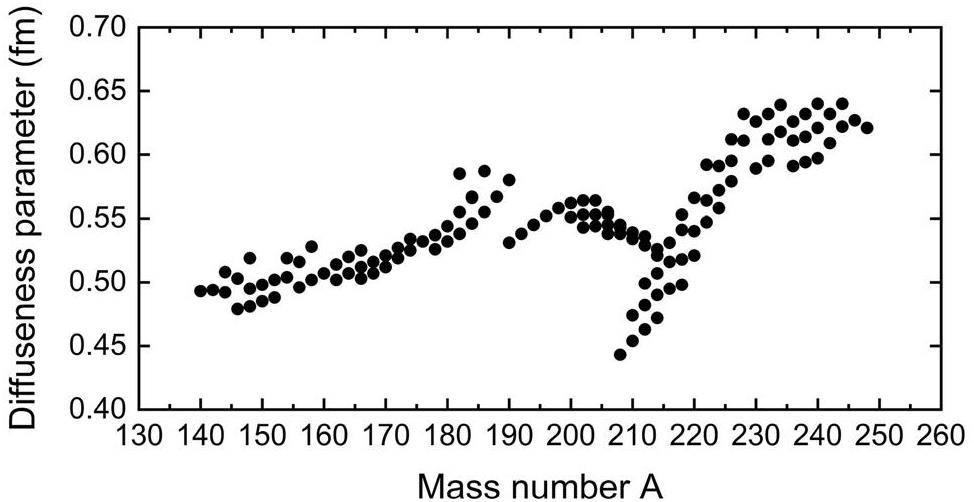

The diffuseness parameters determined using the double-folding procedure are shown in Fig. 3. The diffuseness parameters of the daughter nuclei generally fluctuate around the average value of

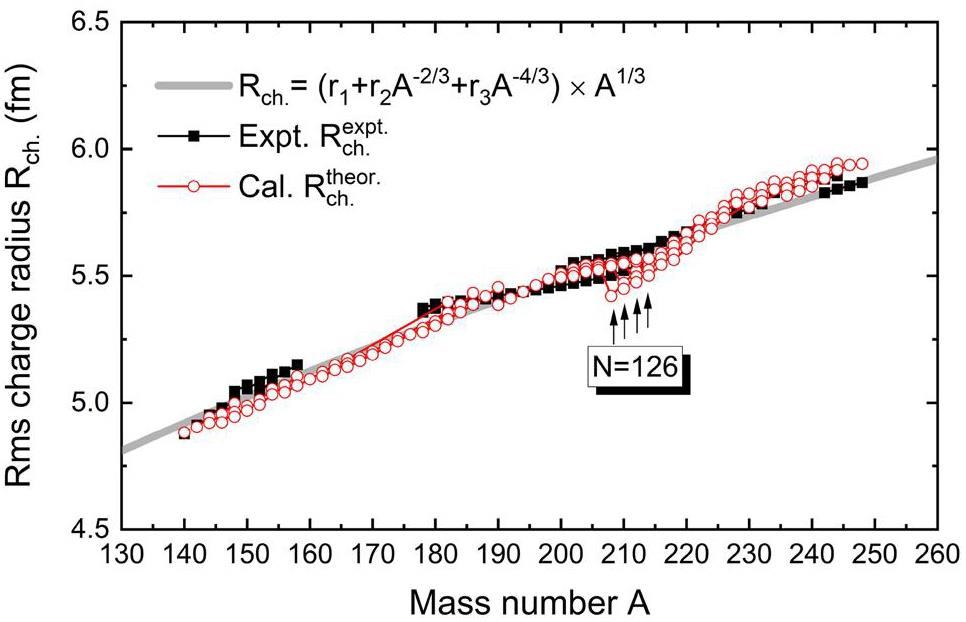

In Fig. 4, we present the calculated charge radii of the daughter nuclei with Z=58-96 and the corresponding experimental values obtained from Ref. [44, 45]. The empirical relationship between the charge radius and the mass number is indicated by the gray line for reference.

In addition, the charge radii of the pocket-type DDFP and previous GDDCMs can be quantitatively compared [22, 24]. Table 1 lists the standard deviations σch. of the nuclear charge radii for these models compared with the experimental data from [44, 45]. Notably, although the DDFP relies solely on the experimental decay energy and reduces one free parameter by avoiding the input of empirical Pα, it yields a more accurate description for the charge radii. Specifically, the standard deviation is reduced by 67.3% compared to GDDCM and by 53.3% compared to GDDCM*. This significant improvement underscores the significance of the α-clustering features in the mechanism of α decay, particularly the medium effect and the strong Pauli repulsion, which make the pocket-type DDFP a more realistic description of the involved α-nucleus interaction.

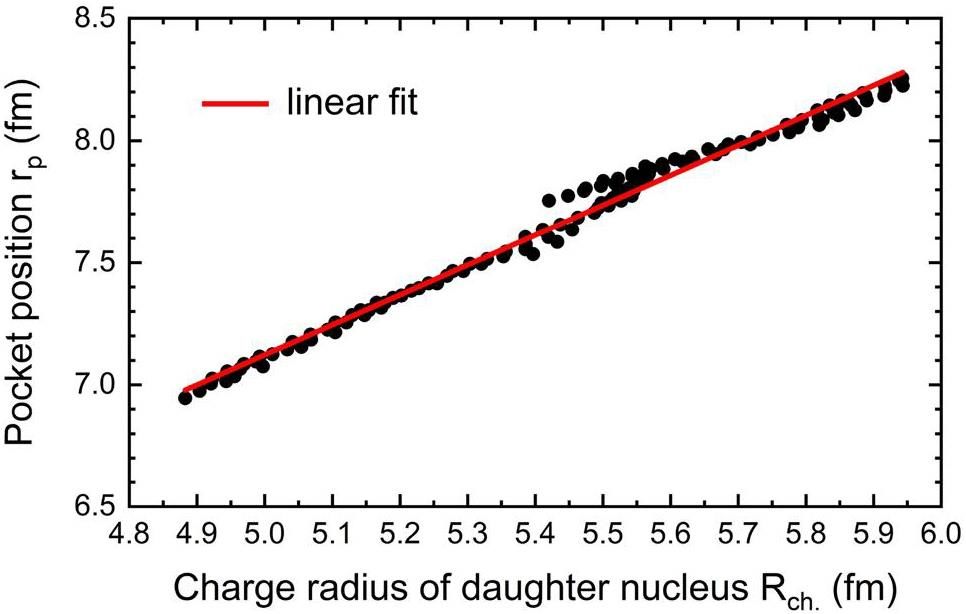

Having determined the charge radii, it is instructive to investigate the correlation between the charge radii of the daughter nuclei and the pocket positions rp of the α-nucleus potentials (see Figs. 1 for 212Po). As seen in Fig. 5, the pocket position is linearly correlated with the charge radius of the daughter nucleus with a correlation coefficient of 0.9885. This finding was expected, because both quantities are related to the spatial extent of the density distribution of the daughter nucleus. The pocket position corresponds to the region where the α cluster is most likely to form, and is located at the nuclear surface with a nucleon density below 1/5 of the saturation density. If the daughter nucleus had a broader density distribution, the pocket position would shift away from the core region, which would yield a larger charge radius. Therefore, the correlation between these quantities embodies the α-clustering feature of the pocket-type potential.

In addition to the α-decay models, theoretical approaches based on mean-field models have proven to be very effective in describing nuclear structural properties, including nuclear charge radii [40, 50-57]. For instance, the deformed relativistic Hartree–Bogoliubov method accurately reproduced the charge radii of 369 even-even nuclei with Z=8-96 achieving a standard deviation

Summary

This study employed the pocket-type dynamical double-folding α-nucleus potential (DDFP) to calculate the α-decay half-lives for 129 even-even nuclei with Z=60-98. The experimental half-lives were accurately reproduced, with an average discrepancy factor of 1.521, thereby demonstrating the precision of DDFP in describing α decay. Moreover, the determination of the DDFP enabled the estimation of the nuclear charge radii from the density distributions of the daughter nuclei. As an improvement over our previous cluster models, DDFP achieves a more accurate description of charge radii with fewer parameters and relies soley on the experimental α-decay energies. The standard deviation between the theoretical and experimental charge radii for 84 even-even nuclei with Z=58-96 is 0.0420 fm, which represents a 53.3% reduction relative to previous calculations [24], although it remains larger than that of some microscopic calculations based on mean-field theories. Notably, the present model provides an approach for estimating the nuclear charge radius from α-decay data, provided that the experimental decay energy is available. It is expected that the accuracy of DDFP can be further improved by refining the density distribution of the daughter nuclei, such as including the differences between the proton and neutron density distributions and considering nuclear deformations. Overall, the strong agreement between theoretical and experimental charge radii serves as further validation of the accuracy of DDFP for α-decay calculations.

The systematic structure-change into the molecule-like structures in the self-conjugate 4n nuclei

. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. E 68, 464-475 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.E68.464Alpha-clustering effects in heavy nuclei

. Front. Phys. 13,Effects of α-clustering structure on nuclear reaction and relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Kinetic approach of light-nuclei production in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Formation ofα clusters in dilute neutron-rich matter

. Science 371, 260-264 (2021). https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.abe4688Absolute alpha decay width of 212Po in a combined shell and cluster model

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 37-40 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.37Cluster-configuration shell model for alpha decay

. Nucl. Phys. A 550, 421-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(92)90017-EMicroscopic description ofα-like resonances

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Shell-model representation to describeα emission

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Alpha decay as a probe for the structure of neutron-deficient nuclei

. Rev. Phys 1, 77-89 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revip.2016.05.001Experimental determination of in-medium cluster binding energies and mott points in nuclear matter

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108,Nuclear clusters bound to doubly magic nuclei: The case of 212Po

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Four-particle condensate in strongly coupled fermion systems

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3177-3180 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.3177Light nuclei quasiparticle energy shifts in hot and dense nuclear matter

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Composition and thermodynamics of nuclear matter with light clusters

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Alpha-like correlations in 20Ne, comparison of quartetting wave function and THSR approaches

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 89 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01305-7Improved nucleus-nucleus folding potential with a repulsive core due to the change of intrinsic kinetic energy

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 45,Theoretical investigation ofα-like quasimolecules in heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Cluster mean-field description ofαemission

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Alpha-clustering and related phenomena in medium and heavy nuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 210 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-01105-5α clustering from the formation of a pocket structure in theα-nucleus potential

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Nuclear charge radii of heavy and superheavy nuclei from the experimentalα-decay energies and half-lives

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Tentative probe into the nuclear charge radii of superheavy odd-mass and odd-odd nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Improved evaluation of nuclear charge radii for superheavy nuclei

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 45,Improved double-foldingα-nucleus potential by including nuclear medium effects

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Significant improvement of half-life calculation of decays by considering the nuclear medium effect

. Phys. Lett. B 795, 554-560 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.06.045Isotopic trends of nuclear surface properties of spherical nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Polarization of the nuclear surface in deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Effect of the pauli exclusion principle on the potential of nucleus-nucleus interaction

. Phys. Atom. Nuclei 74, 1142 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778810070070Effective nucleus-nucleus potential for calculation of potential energy of a dinuclear system

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 5, 191-216 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301396000098Quasiparticles in the theory of the nucleus

. Sov. Phys. Usp. 10, 285 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1070/PU1967v010n03ABEH003247Nuclear charge-density-distribution parameters from elastic electron scattering

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 36, 495-536 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-640X(87)90013-1Decay width and the shift of a quasistationary state

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 262-265 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.262Reduced alpha transfer rates in a schematic model

. Phys. Rev. C 36, 456-459 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.36.456Shell and blocking effects inα-transfer reactions

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 15, 465 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/15/4/010α-decay studies of the exotic n=125, 126, and 127 isotones

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Analytic expressions forα particle preformation in heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Isospin asymmetry dependence of theα spectroscopic factor for heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 84,α-decay reduced width of 194Pb and low-spin levels in 194Tl populated in 194Pb βdecay

. Phys. Rev. C 36, 1529-1539 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.36.1529Half-life of 228Pu andα decay of 228Np

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Alpha-decay for heavy nuclei in the ground and isomeric states

. Nucl. Phys. A 832, 198-208 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2009.10.082α-decay near the shell closure from ground and isomeric states

. Nucl. Phys. A 866, 1-15 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2011.07.002α preformation factors of medium-mass nuclei and the structural effects in the region of crossing the z=82 shell

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Table of experimental nuclear ground state charge radii: An update

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 99, 69-95 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2011.12.006Compilation of recent nuclear ground state charge radius measurements and tests for models

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 140,Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic hartree-bogoliubov theory in continuum, i: Even-even nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 144,Charge radius isotope shift across the n=126 shell gap

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Predictions of the decay properties of the superheavy nuclei 293, 294 119 and 294, 295120

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Neutron skin thickness and its effects in nuclear reactions

. Nucl. Tech. 46,First gogny-hartree-fock-bogoliubov nuclear mass model

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,consistent theory of finite fermi systems and radii of nuclei

. Phys. Atom. Nuclei 74, 1277 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778811090109Local variations of charge radii for nuclei with even z from 84 to 120

. Commun. Theor. Phys. 75,Analysis of parity-violating electron scattering on deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Improved description of nuclear charge radii: Global trends beyond n=28 shell closure

. Phys. Rev. C 109,α-decay half-lives for even-even isotopes of w to u

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Wavefunction matching for solving quantum many-body problems

. Nature (London) 630, 59-63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07422-zDeformed halo nuclei and shape decoupling effects

. Nucl. Tech. 46,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.