Introduction

Carbon fusion is the primary reaction in massive stars [1-4]. It also serves as an ignition reaction for Type Ia supernova explosions [5, 6] and X-ray superbursts [7, 8]. An accurate carbon–carbon fusion-reaction rate can reduce uncertainties in the nucleosynthesis of massive stars and the ignition condition in Type Ia supernova as well as contribute to resolving the ignition problem in superbursts [9, 10].

The carbon–carbon fusion reaction in stars occurs at energies below Ec.m.= 3.0 MeV, which is considerably below the Coulomb barrier at

Although the particle-gamma coincidence method and underground gamma-ray measurements can extend the measurement to even lower energies, the channels of charged particles decaying to the ground states of 23Na and 20Ne cannot be studied using these methods owing to the absence of gamma rays [18, 29]. We developed a novel technique based on a time-projection chamber (TPC) to measure the nongamma-ray-emitting channels 12C(12C,α0)20Ne and 12C(12C,p0)23Na. Our commissioning experiment using the 1024-channel prototype pMATE TPC (multi-purpose time-projection chamber for nuclear astrophysical and exotic-beam experiments) demonstrated that more than 99% of alpha contaminants from the natural environment may be rejected by this technique [30].

An ultrapure carbon target able to withstand beam powers exceeding 400 W is another important factor in carbon-fusion experiments [31, 32]. The background induced by the target impurities, primarily hydrogen and lithium isotopes, may be orders of magnitude higher than the reaction events of interest, limiting the experimental sensitivities. Therefore, obtaining high-purity carbon targets is important to achieve the desired sensitivity. In addition, the small 12C+12C fusion-reaction cross section at stellar energies requires high beam intensity and a long beam time on the order of weeks. Therefore, target stability is another important feature of carbon targets.

This study reports the first direct measurement of the 12C(12C,α0)20Ne reaction at Ec.m.= 2.22 MeV using the highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) target and our upgraded TPC-Si detector array. We also investigate the impact of radiation damage on the detected yield of charged particles such as protons and alpha particles. This study consists of four parts. The first part introduces the experimental setup. The second part describes the experimental method. The third part reports the study of the dependence of the detected yield of charged particles on the accumulated dose of the HOPG target. In the fourth part, we present the measurement of the thick target yield of 12C(12C,α0)20Ne at Ec.m.= 2.22 MeV using the HOPG target.

Experimental setup

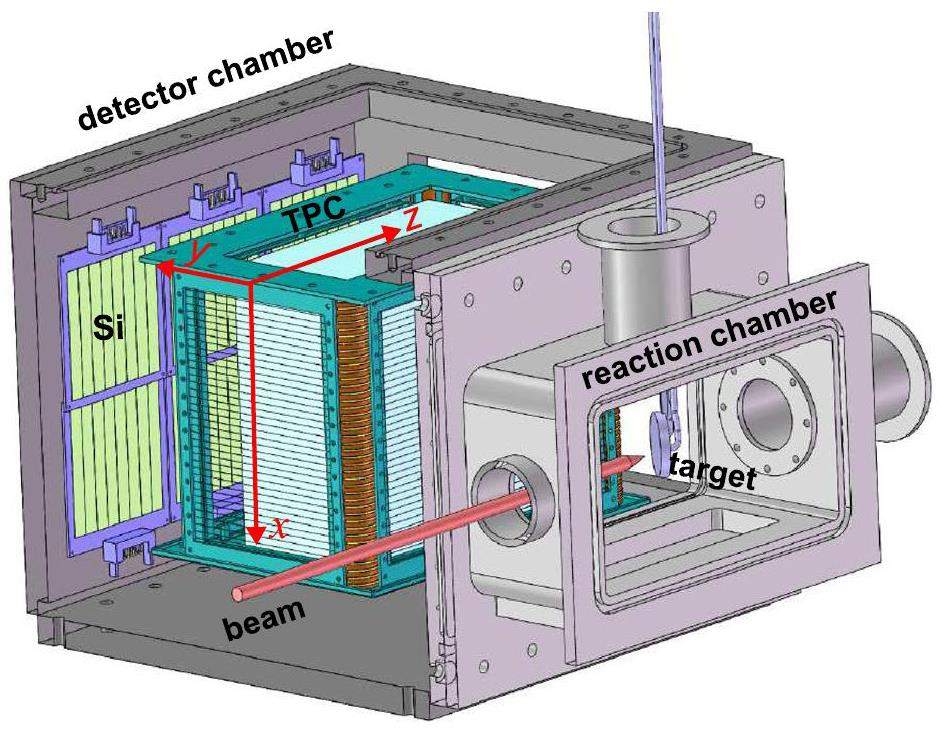

The experimental setup comprises a reaction chamber and detector chamber. A schematic of the setup is shown in Fig. 1. In the reaction chamber, a thick carbon target was mounted on water-cooled stainless-steel backing. The angle between the beam and normal directions of the target surface was set to 135°, allowing the light charged particles from the fusion reaction to be detected by the detectors. A water-cooled collimator with a diameter of 10 mm was installed 40 cm upstream of the target, and the beam spot on the target was limited to ∼10 mm.

Our detection system comprises a TPC and silicon-detector array. It was installed in the detector chamber filled with counting gas. A large-area Kapton foil with a thickness of 5 μm and an area of 7 cm × 21 cm was used to separate the gas in the detector chamber from the reaction chamber. The Kapton foil was coated with approximately 100-nm-thick aluminum to prevent charge accumulation and shield the silicon detectors from light coming from the beam spot on the carbon target. Two types of stainless-steel hexagonal meshes with transmittances of 77% and 90% were used to support the foil; the typical gas pressure varied from 50 mbar to 300 mbar.

The TPC has an active volume of 100mm(W)×200mm(L)×200mm(H). When the charged particles travel in the TPC gas region, they ionize the gas along their paths. The ionized electrons drift along the electric field towards the anode-readout plate, and an avalanche occurs. The primary and avalanche electrons are collected using an anode plate with rectangular pads.

The three-dimensional position can be determined by measuring the electron drift time. Further details of the TPC detector and its commissioning experiment are provided in Ref. [30, 33].

The silicon array consists of six silicon detectors (Hamamatsu, Japan) with thicknesses of 600 μm [34]. Each silicon detector has eight strips at the junction side in a direction parallel to the electric field of the TPC, dividing the scattering angle into a finer size. The total active area is 90.6 mm × 90.6 mm. The distance between the silicon array and TPC active region can be adjusted from 80 mm to 120 mm. The combination of the silicon detectors and TPC forms a

Experiments

A 2-mm thick HOPG target was bombarded by the 12C beam delivered by the low-energy high-intensity high-charge-state ion accelerator facility at the Institute of Modern Physics [35]. During the experiments presented in Sections 3 and 5, thick gas electron multipliers [36] were used for gas amplification, and the TPC chamber was placed at a scattering angle of 90. To study the reaction-yield variations using the HOPG target (Sect. 4), the TPC with MicroMegas amplification was used for stable operation at a low gas pressure [37, 38] and was placed at a scattering angle of 120. The gas type and pressure were selected to ensure that the charged particles could penetrate the TPC active volume and stop in the Si detectors while depositing sufficient energy in the gas to generate tracks.

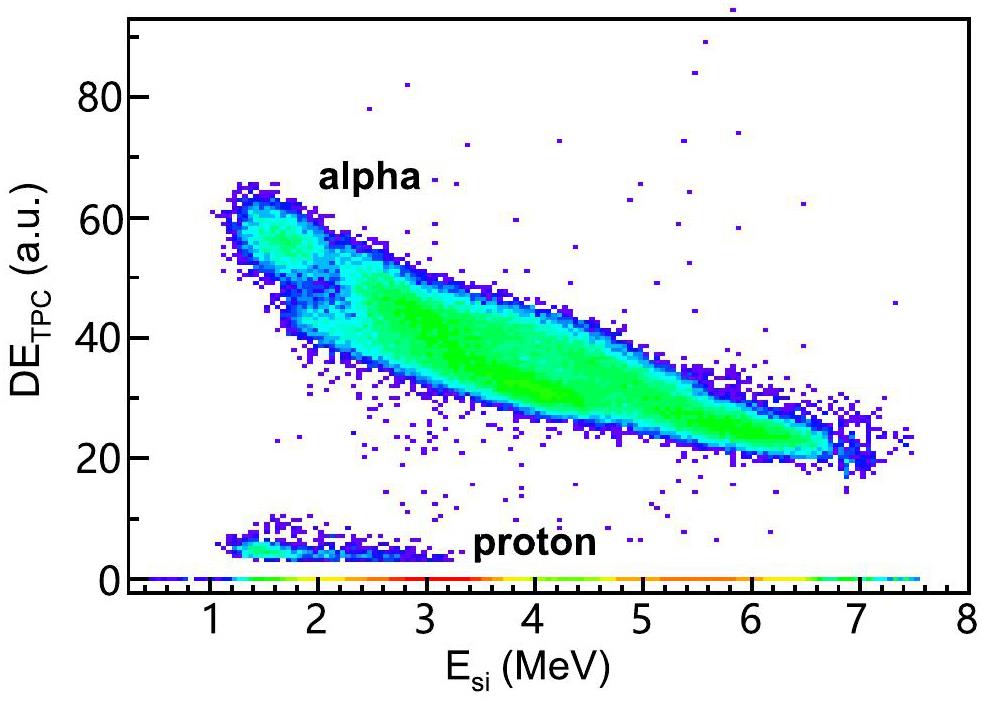

A typical DETPC-Esi spectrum measured at Ec.m.= 3.90 MeV is shown in Fig. 2. Here, DETPC and

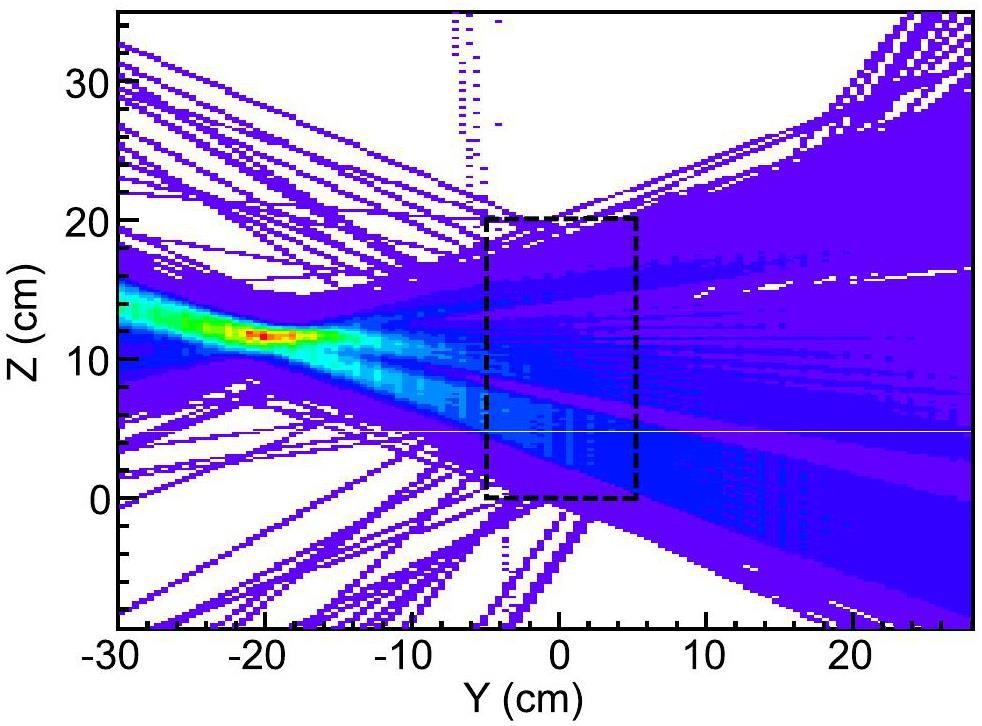

An important advantage of the TPC is its ability to track charged particles [30, 39]. The tracks of the alpha events can be traced back to the beam axis to check whether they originated from the beam spot on the reaction target. An example of track reconstruction in the pad plane (YZ plane) using the selected alpha events is shown in Fig. 3. Most tracks converged around the (-20 cm, 11 cm) point, which clearly defined the beam spot on the reaction target. All other events mostly originated from the natural radioactivity of the surrounding material. The alpha events from the beam spot could be further purified using the TPC drift time [30].

The alpha particles emitted from the target position were selected by gating their

Stability of the HOPG target

The HOPG target was composed of several graphene layers. After beam bombardment, the graphene layers on the surface were damaged and formed a flaky and wrinkled structure as shown in Fig. 5. This radiation damage modified the surface structure and may potentially affect the detection of low-energy charged particles, a phenomenon that has not yet been studied.

We studied the effect of intense beam irradiation on the HOPG target by measuring 12C+12C reaction yields. In the test, a 12C2+ beam at a relatively high energy of Ec.m.= 3.55 MeV was chosen to obtain sufficient statistics within a few minutes. The detector was placed at an angle of 120 ° at a gas pressure of 99 mbar. During charge accumulation, the beam was 12C2+ with a typical current of 40 ∼ 50 pμA. Two types of targets, 4-μm-thick diamond-like carbon (DLC) [40] and 2-mm-thick HOPG targets [41], were used to study the variations in the yields of the carbon–carbon fusion reaction as a function of the beam dose.

An infrared camera was used to monitor the maximum temperature of the target. The observations indicate that the beam spot size on the DLC and HOPG was approximately 1 cm2. With water cooling at the back of the target, the maximum temperature of the DLC surface stabilized at approximately 100 ℃. However, the surface temperature of the HOPG target quickly increased to ∼400 ℃ when the beam hit it. This difference might have been caused by the weak interlayer interactions between the individual graphene layers in the HOPG target [42, 41]. Such a structure led to a low through-plane thermal conductivity, which was more than two orders of magnitude lower than that of natural graphite. The formation of flaky and wrinkled structures after irradiation further reduced thermal conduction.

During measurements, the TPC was placed at 120. The detector chamber was filled with a gas mixture of 90% He, 5% CO2, and 5% Ar at a pressure of 100 mbar. As discussed in the previous section, the alpha yield was determined directly by selecting the alpha band in the

Q-value spectra of the alpha and proton channels

The reaction Q values for the proton (Qg.s.= 2.24 MeV) and alpha (Qg.s.= 4.62 MeV) channels were calculated using the following formulas:

To reduce the systematic error arising from energy-loss correction, only the events measured by the two silicon detectors in the middle were used.

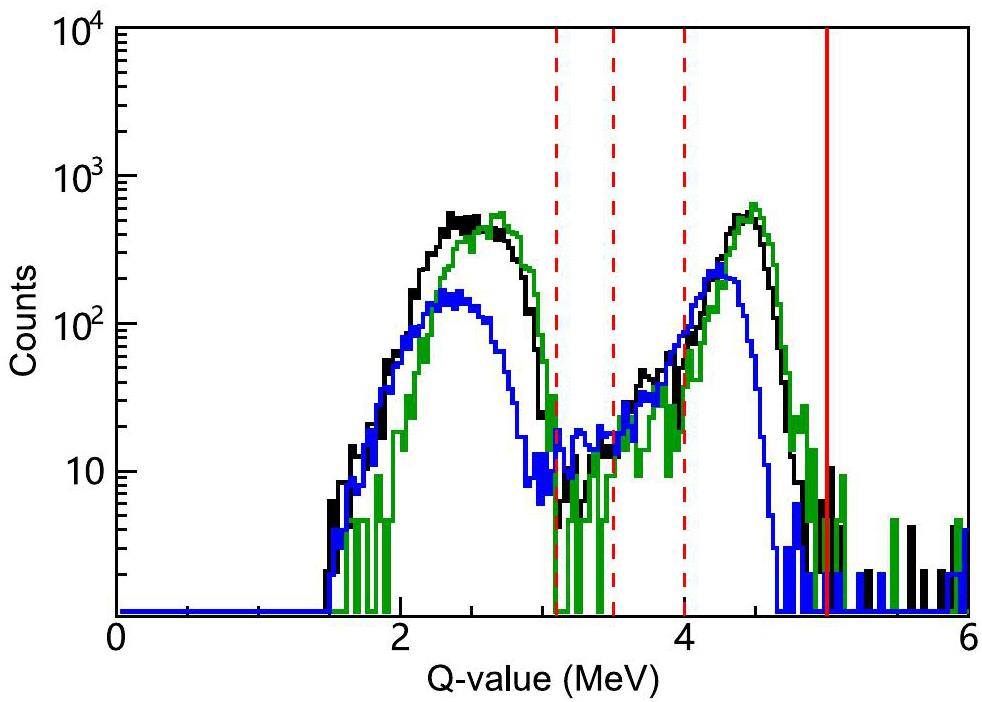

The Q-value spectra of 12C(12C,α)20Ne and 12C(12C,p)23Na at Ec.m.= 3.55 MeV are shown in Fig. 6 and 7, respectively. The green line in Fig. 6 shows the Q-value spectrum for 12C(12C,α)20Ne using the DLC target at a beam charge of 2.18× 104 μC. This spectrum was measured at the beginning of the beam irradiation. The α0 and α1 peaks were located at Q values of 4.62 MeV and 2.99 MeV, respectively. No noticeable change was observed in the Q-value spectrum during the subsequent charge accumulation on the DLC.

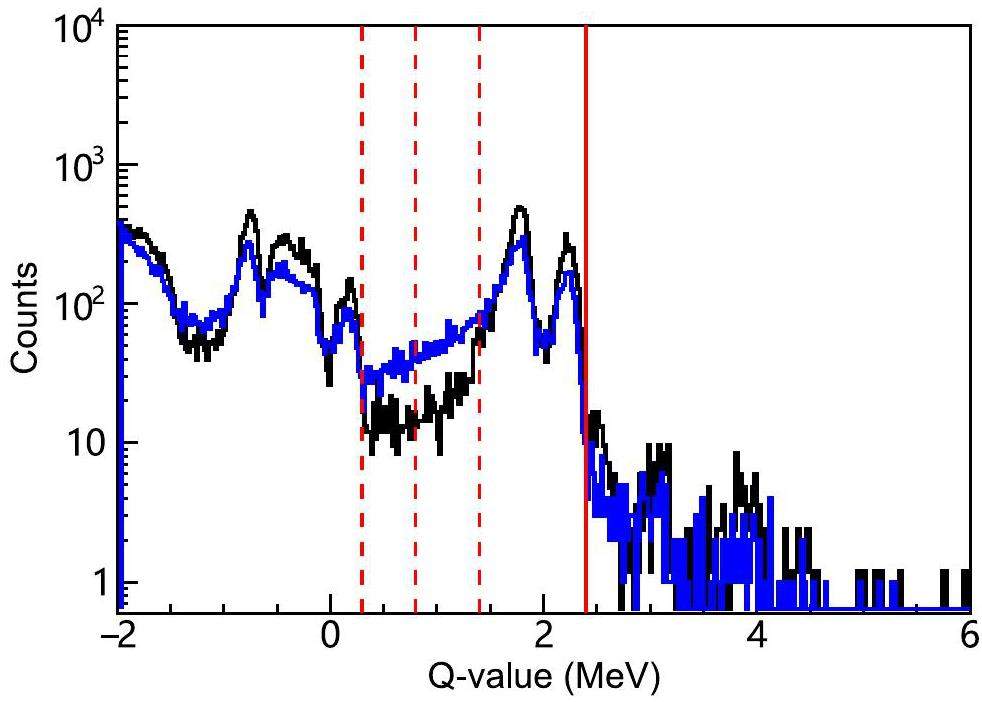

The black and blue lines shown in Fig. 6 represent the HOPG target with the accumulated charges of 4.82×104 μC and 4.94×106 μC, respectively. Comparing the shapes of the Q-value spectra of the HOPG and DLC targets, we can clearly observe a shift and broadening of the α0 and α1 peaks for HOPG as the beam dose increases. The black and blue lines shown in Fig. 7 represent the Q-value spectra for protons corresponding to 2.59×105 μC and 4.94×106 μC on the HOPG, respectively. The p0 and p1 peaks are located at Q values of 2.24 MeV and 1.80 MeV, respectively. The p0 and p1 peaks become broader and develop a longer tail towards the lower Q-value region after approximately 5 C of radiation.

Dependence of the measured alpha and proton yields on the beam dose

We investigated the dependence of the measured alpha and proton yields on the beam dose. The reaction yields were calculated by integrating the peaks of the protons and alpha particles in the Q-value spectra divided by the incident-beam particles.

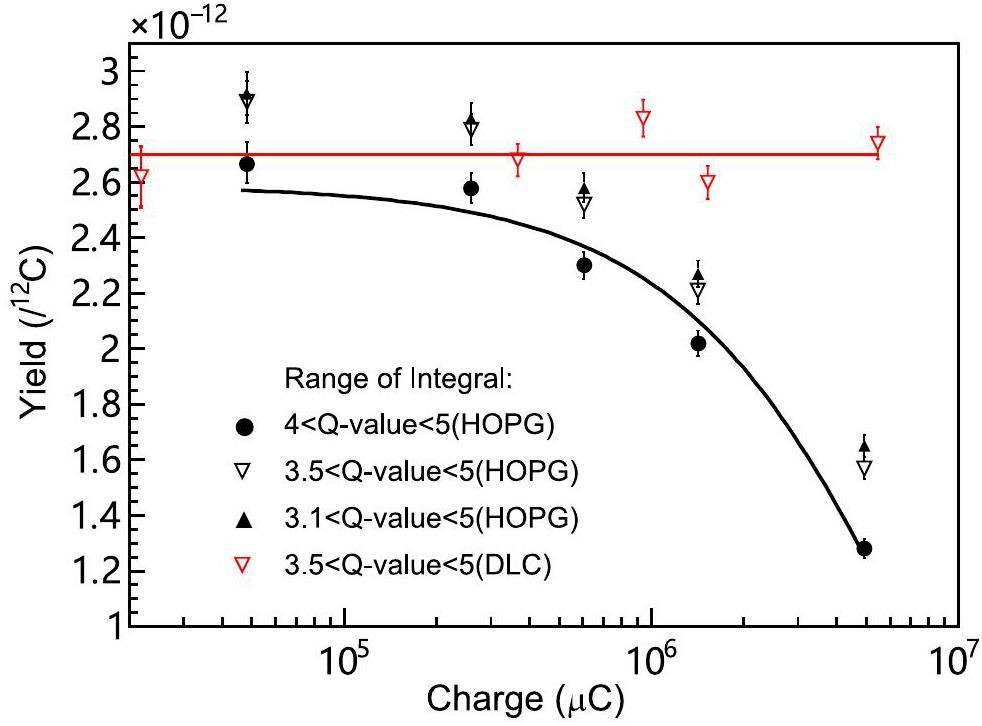

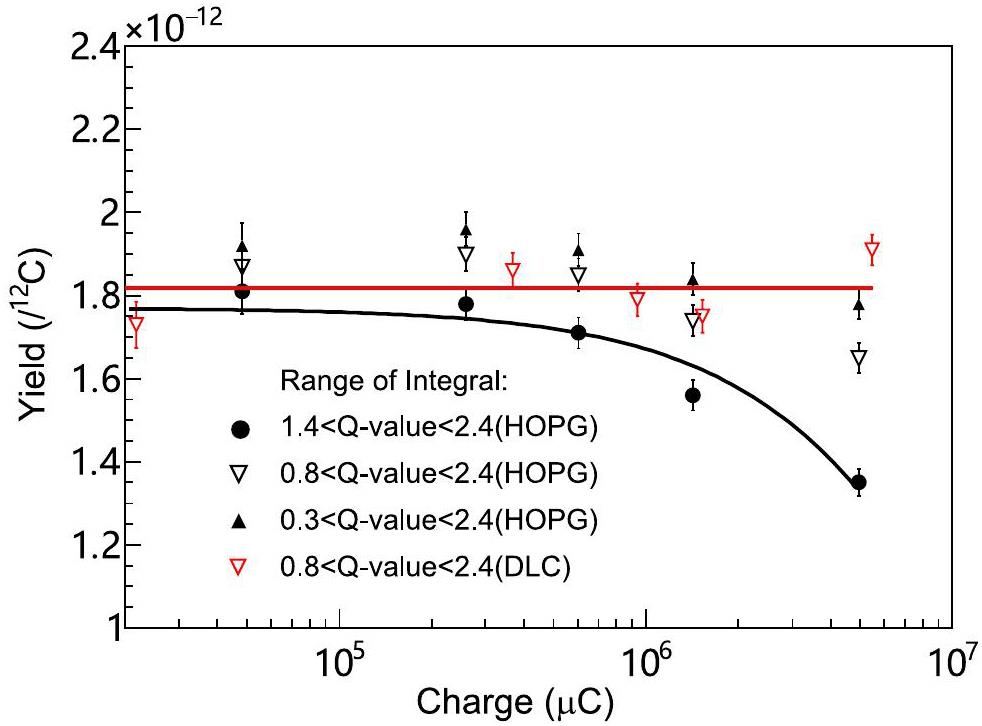

The yield variations in α0 and p0 + p1 are presented in Fig. 8 and 9, respectively, as a function of accumulated charge. For each channel, three different yields corresponding to different integral ranges in the Q-value spectra (indicated by red lines in Fig. 6 and 7) were obtained to account for the change in the Q-value spectra. With an increase in the charge on the HOPG, the yields of both α0 and p0 + p1 exhibited a notable decrease. This scenario worsened for the alpha-emission channels. The decreasing trend in the yield of α0 (4.0 MeV <Q-value <5.0 MeV)for HOPG can be fitted well by the following exponential function:

Based on the fitted yield curves shown in Fig. 8, the yield of α0 decreased by 34.9% when the dose reached 3.0×106 μC and by 51.5% when the dose reached 5.0×106 μC. To mitigate the broadening effect induced by beam irradiation, we employed two extended integral ranges: [3.5 MeV, 5.0 MeV] and [3.1 MeV, 5.0 MeV]. Compared with the integration within [4.0 MeV, 5.0 MeV], the alpha yields increased by 22.0(0.8)% and 28(1)%, respectively, when the dose reached 4.94×106 μC. The α0 yield obtained from the three integral ranges exhibited a similar trend as the accumulated charge increased from 0 C to ∼5 C.

For comparison, the same test was performed using the DLC target. The maximum beam dose reached 5.5×106 μC. The yield of α0 was approximately constant at 2.70× 10-12 /12C according to the fitted yield line, as shown in Fig. 8.

The DLC target contained a fraction of hydrogen. The yield difference for the DLC and HOPG targets at a nearly zero dose could be explained by the difference in stopping power.

Regarding the p0+p1 yield, the situation differed slightly. When the beam charge accumulated up to 5.0×106 μC, the yield decreased by 25% according to the fitted yield curve shown in Fig. 9. The decrease in the p0 + p1 yield could be reduced to 7.0(0.3)% if the integration range is increased to [0.3 MeV, 2.4 MeV].

Discussion

Based on the above analysis, the 12C(12C,α0)20Ne reaction yield in the HOPG target was significantly reduced under intense beam bombardment. The HOPG target surface was damaged and formed a flaky and wrinkled structure, whereas deeper HOPG layers were exposed to incident-beam particles. Some alpha particles from the fusion reaction were either stopped in the target or experienced more energy loss before escaping from the target surface, owing to the flaky and wrinkled structure. Consequently, the detected alpha Q-value spectrum was distorted and the integrated yield decreased as the beam dose increased.

Protons have better penetration power than alpha particles. For example, the stopping range of a 4-MeV proton in graphite materials is approximately 10 times longer than that of an α particle with the same energy [44]. This may be why the loss of the proton-reaction yield is less significant than that of the α particle. By increasing the integration limit in the Q-value spectrum, the effect on the proton-reaction yield was reduced to less than 10%, as shown in Fig. 9.

Notably, radiation damage is a very complex and combined process, depending not only on charge accumulation, but also on the areal power density, target cooling, and alpha energy. Very recently, Tan et al. discussed the dependence of radiation damage on beam energy [45]. Therefore, the fitted curve obtained in this study can only be applied to correct the yield obtained under conditions identical to our setup.

Measurement of 12C(12C,α0)20Ne at Ec.m.= 2.22 MeV

We also measured the 12C(12C,α)20Ne reaction at Ec.m.= 2.22 MeV using the HOPG target to test the target purity and sensitivity of the TPC-detection technique. The cross section at this energy was estimated to be only a few tens of picobarns, based on the extrapolation of CF88 [11, 13]. The 12C4+ beam intensity was approximately 15 pμA, and the total accumulated charge was 3.26×106 μC. The detector was placed at 90 degrees and filled with 95%He+5%CO2. Thick GEM-based readout pads were used. For the detection of α particles, the gas pressure in the TPC was optimized to 135 mbar.

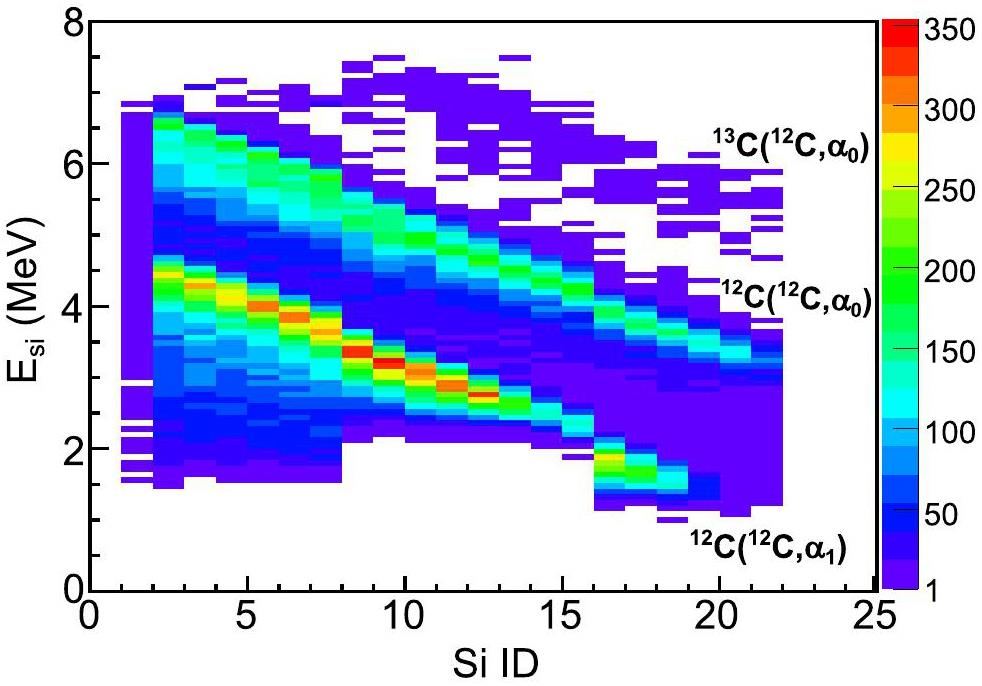

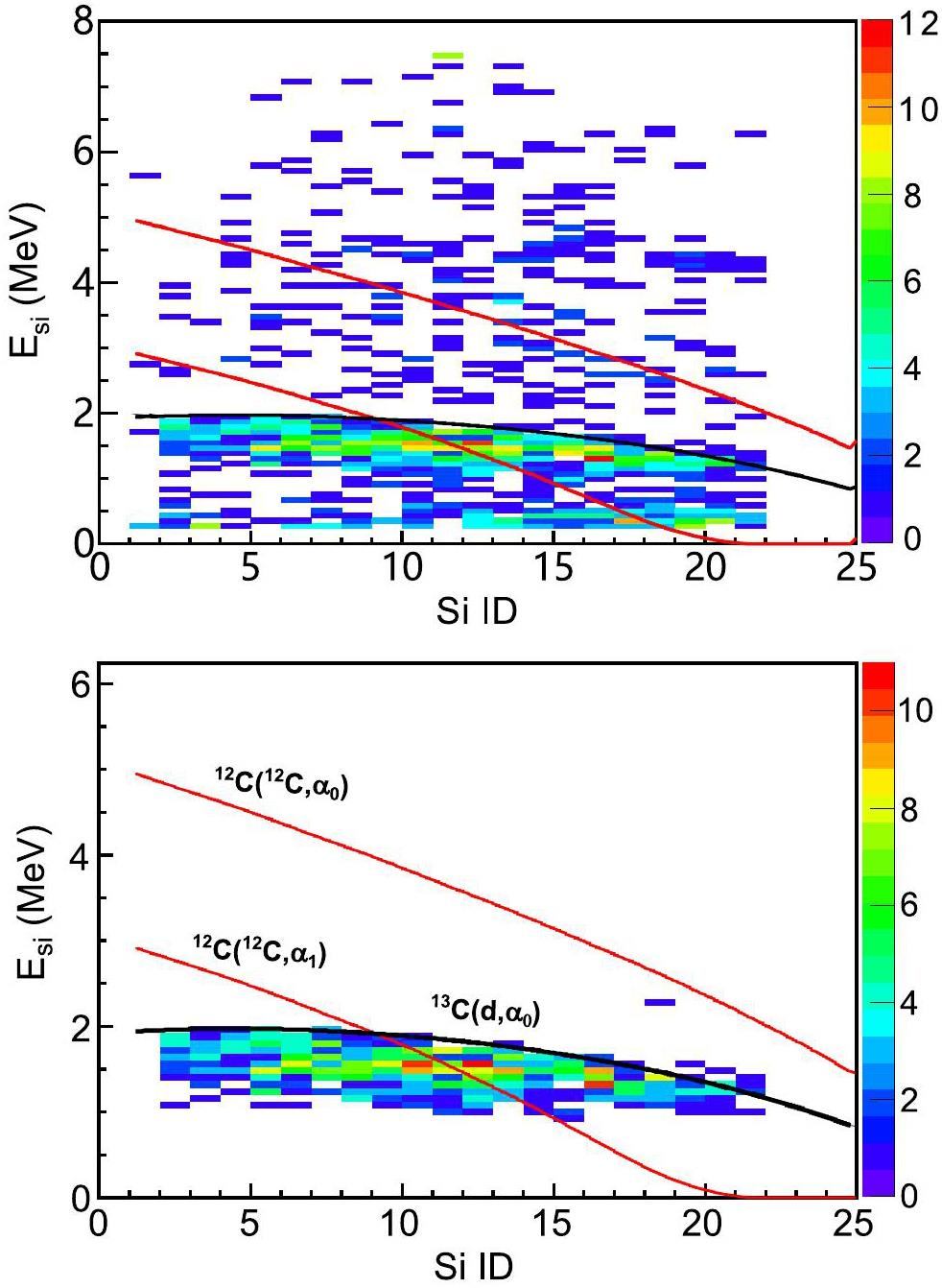

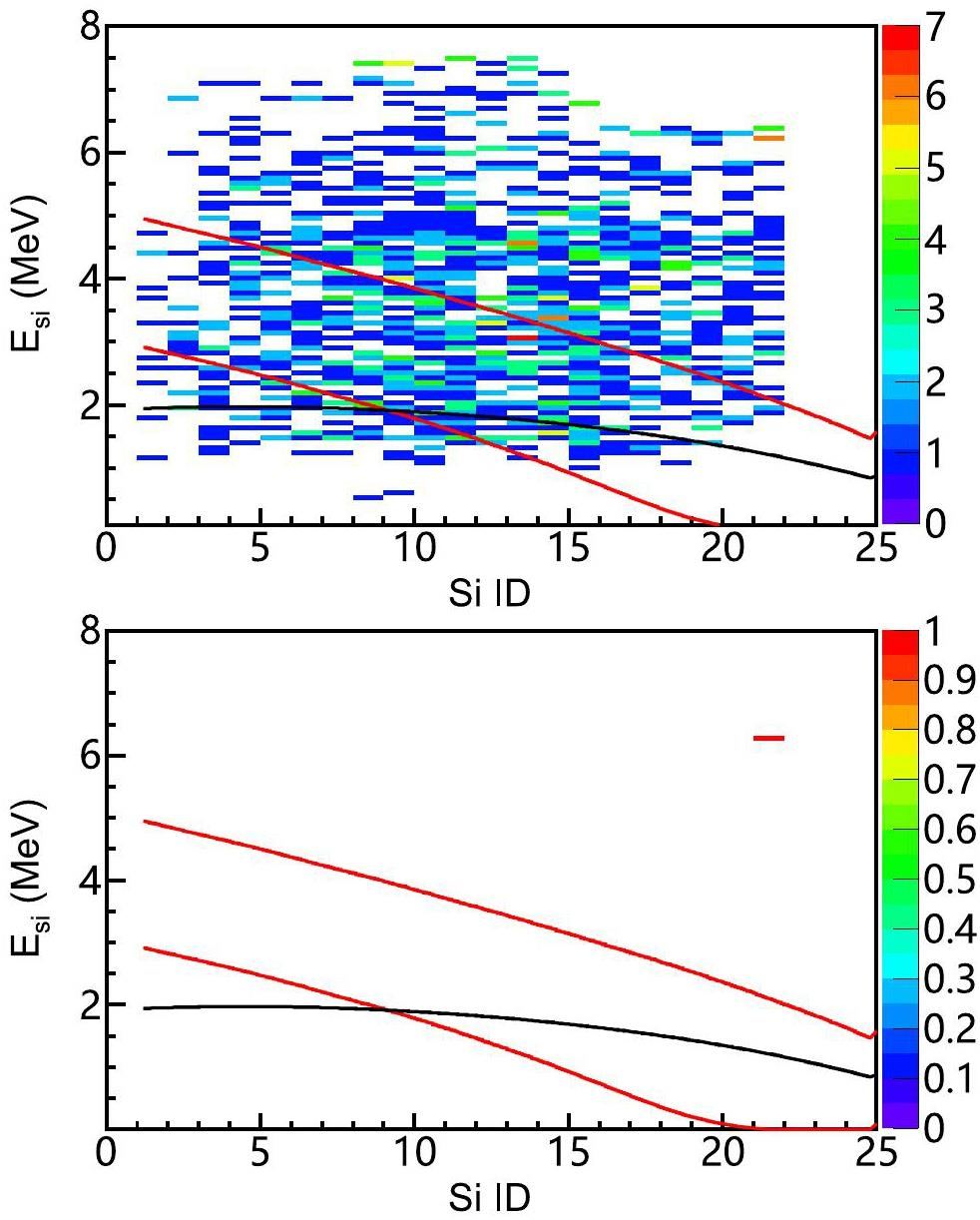

Using the same analysis procedure, we obtained the spectrum of the energy deposited in the silicon detectors versus the silicon-strip number for the alpha events. The results are shown in Fig. 10; the top figure is obtained by gating the alpha events in the

Conclusion

Ultrapure high-power carbon targets are essential for experimental studies of 12C+12C fusion reactions at stellar energies. HOPG has frequently been adopted as a reaction target in experiments because of its superior purity. In this study, we investigated the reaction-yield dependence on the accumulated beam dose on an HOPG target. Our results showed that the alpha yields were significantly reduced under intense beam bombardment. When the beam dose accumulated to 5 C, the decrease in the alpha yields was 51.5%. Moreover, shifts and broadening of the proton and alpha peaks were clearly observed. To obtain the absolute yield, a correction was required according to the beam dose on the target. Using the TPC-detection technique and HOPG target, we successfully extended the direct measurement of 12C(12C,α0)20Ne to Ec.m.= 2.22 MeV, which is within the Gamow window for the carbon burning of massive stars. The thick target yield was determined to be

Heavy ion fusion reactions in stars

. AIP Conf. Proc. 1947,The 12C+12C fusion reaction at stellar energies

. AIP Conf. Proc. 260, 01002 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202226001002Impact of the new 12C+12C reaction rate on presupernova nucleosynthesis

. Chin. Phys. C 47,Type Ia supernova explosion models

. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astr.. 38, 191-230 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.astro.38.1.191Underground laboratory JUNA shedding light on stellar nucleosynthesis

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 42 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01196-1Nuclear heating and melted layers in the inner crust of an accreting neutron star

. Astrophys. J. 531, 988 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1086/308487Superburst ignition and implications for neutron star interiors

. Astrophys. J. 614,Possible resonances in The 12C + 12C fusion rate and superburst ignitio

. Astrophys. J. 702, 660-671 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/702/1/660Implications of low-energy fusion hindrance on stellar burning and nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 76,The 12C+12C reaction and the impact in nucleosynthesis in massive stars

. Phys. Rev. C 762, 31 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/762/1/31Correlation between the 12C+12C, 12C+13C, and 13C+13C fusion cross sections

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Thermonuclear reaction rates V

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data. 40, 283-334 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-640X(88)90005-2Modified astrophysical S-factor of 12C+12C fusion reaction at sub-barrier energies

. Chin. Phys. C 44,First Direct Measurement of 12C(12C,n)23Mg at Stellar Energies

. Phys. Rev. C. 114,Measurement of the 12C(12C,p)23Na cross section near the Gamow energy

. Phys. Rev. C. 97,Experimental Investigation of the Stellar Nuclear Reaction 12C + 12C at Low Energies

. Astrophys. J. 157, 367 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1086/150073The 12C + 12C reaction at subcoulomb energies

. Zeitschrift für Physik A 303, 305-312 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01421528Experimental Measurements of the 12C + 12C Nuclear Reactions at Low Energies

. Phys. Rev. C. 7, 1280-1287 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.7.128012C+12C Fusion Reactions near the Gamow Energy

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,The 12C + 12C sub-coulomb fusion cross section

. Nucl. Phys. A 282, 181-188 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(77)90179-8Advances in the direct study of carbon burning in massive stars

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,New Measurement of 12C+12C Fusion reaction at astrophysical energies

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,on behalf of the LUNA Collaboration, The LUNA-MV facility at Gran Sasso

. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1342,Development of a low-background neutron detector array

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01030-0Progress of underground nuclear astrophysics experiment JUNA in China

. Few-Body Syst. 63, 43 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00601-022-01735-3Examining the fluorine overabundance problem by conducting Jinping deep underground experiment

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Nuclear astrophysics research based on HI-13 tandem accelerator

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Direct measurements of the 12C+12C reactions cross-sections towards astrophysical energies

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01233-6Studying the heavy-ion fusion reactions at stellar energies using Time Projection Chamber

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1016,Low energy beam induced background studies for a 12C(12C,p)23Na reaction cross section measurement

. In *Nuclei in the Cosmos*, 19 (2010). http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2010nuco.confE..19ZReduction of deuterium content in carbon targets for 12C + 12C reaction studies of astrophysical interest

. Eur. Phys. J. A 54, 132 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2018-12564-8Studies of the 2α and 3α channels of the 12C+12C reaction in the range of Ecm=8.9 MeV to 21 MeV using the active target Time Projection Chamber

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Construction and performance test of charged particle detector array for MATE

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 131 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01500-7Production of high intensity highly charged cocktail beams at LEAF

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1027,A successful application of thinner-THGEMs

. J. Instrum. 8,A thermal bonding method for manufacturing Micromegas detectors

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 989,A novel resistive anode using a germanium film for Micromegas detectors

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1031,A gaseous time projection chamber with Micromegas readout for low-radioactive material screening

. Radiation Detection Technology and Methods 7, 90-99 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-022-00364-yExcellent heat transfer and mechanical properties of graphite material with rolled-up graphene layers

. Carbon 208, 123-130 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2023.03.041Nanostructures and nanomechanical properties of ion-irradiated HOPG

. Carbon Lett. 31, 593-599 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42823-020-00183-5An efficient method for mapping the 12C+12C molecular resonances at low energies

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 126 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0652-9Website

. www.srim.org (accessedCoincident measurement of the 12C-12C fusion cross section via the differential thick-target technique

. Phys. Rev. C 110, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.110.035808Unified approach to the classical statistical analysis of small signals

. Phys. Rev. D 57, 3873 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.57.3873The authors declare that they have no competing interests.