Introduction

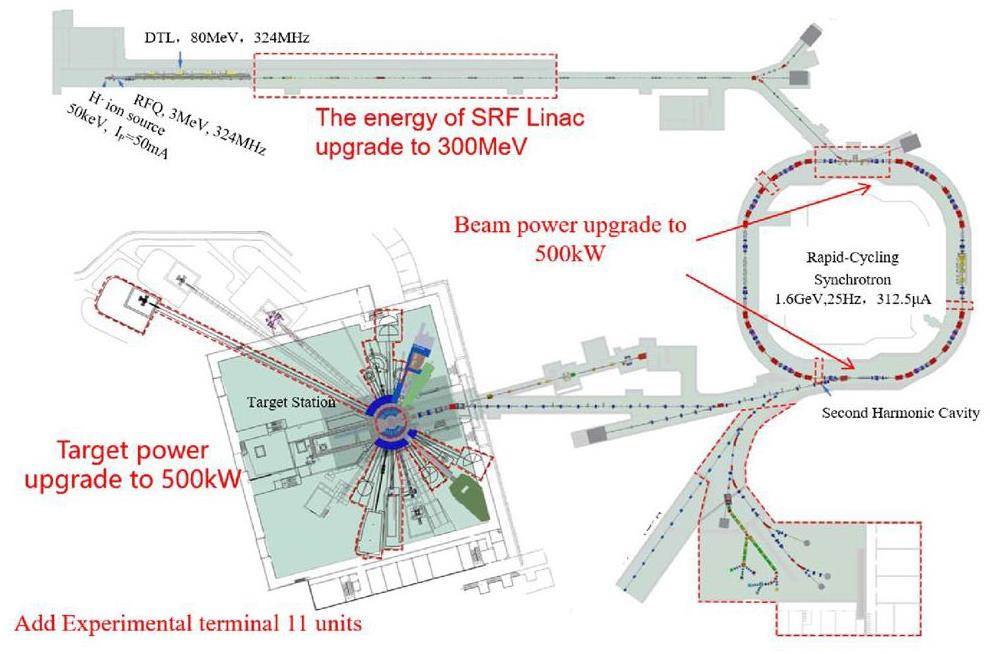

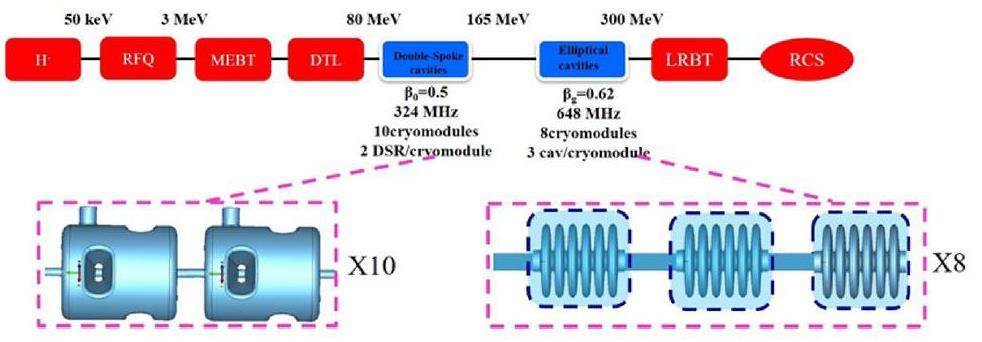

In the planned upgrade of the China Spallation Neutron Source Phase II (CSNS-II), a superconducting linear accelerator composed of double-spoke and elliptical cavities will be installed after the existing room-temperature drift tube linac (DTL) [1]. The beam energy of the linear accelerator will be increased from 80 to 300 MeV, and the peak beam current will be increased from 15 to 50 mA. Subsequently, the beam will be injected into the rapid cycling synchrotron (RCS) [2], which has added magnetic alloy cavities [3], where the proton beam power will increase from 100 to 500 kW and the average beam current will increase from 62.5 to 315 μA. Finally, the proton beam will be directed to the target station, which will have 11 additional beamlines for different experiments. The entire plan is shown in Fig. 1 [4, 5].

Owing to its high-velocity acceptance and high acceleration efficiency, the spoke cavity has strong advantages in low-beta proton accelerators. Currently, spoke superconducting cavities are widely used in the world’s major low-beta proton accelerators. For example, the ESS uses 13 double-spoke superconducting cavity cryomodules to boost the beam energy to 216 MeV. In a vertical testing, the maximum gradient reached 19 MV/m, with the highest Q value exceeding 6×1010. Most of the 13 double-spoke cavity cryomodules used in a horizontal testing achieved an acceleration gradient of 12 MV/m. After calibration, data from the tests indicated that the two cavities exceeded an acceleration gradient of 15 MV/m [6, 7]. The Proton Improvement Plan II project utilizes a resonator (SSR) with beta values of 0.22 and 0.47 to increase the proton energy to 185 MeV. In the horizontal testing, the maximum gradient of the SSR reached 11.2 MV/m [8].

Based on research on double-spoke cavities and experience in foreign engineering, the linac upgrade plan of CSNS-II involves the use of a double-spoke resonator (DSR) with

Double-Spoke Cavity Cryomodule

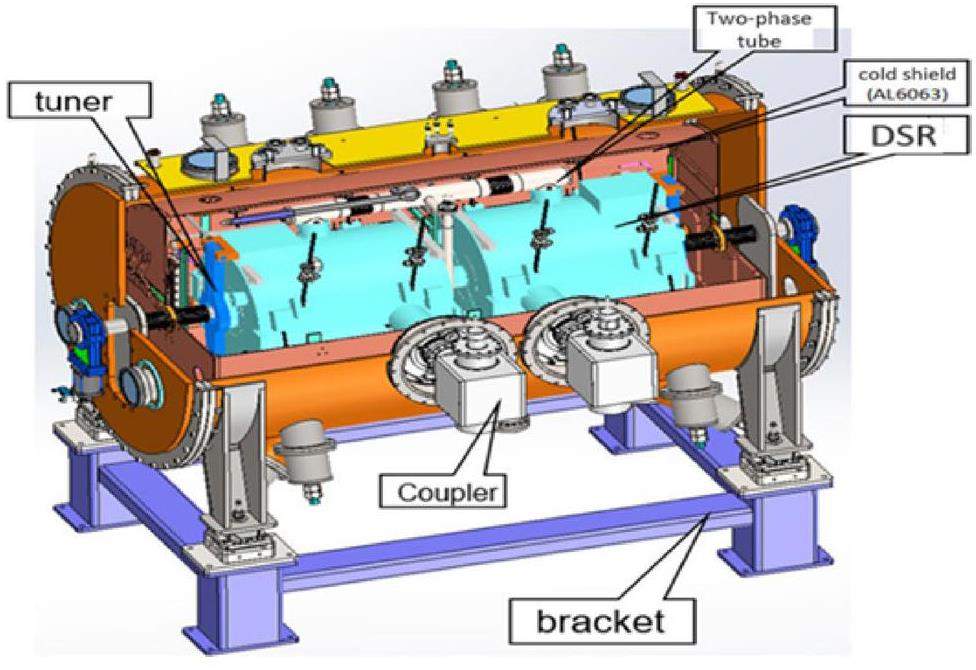

Before formal construction, a cryomodule prototype was constructed to verify the reliability of the performance of the superconducting cavity, the clean assembly and cold mass installation process of the cavity string, and the feasibility of the cryomodule [5]. This prototype included two double-spoke superconducting cavities, two tuners, two couplers with fixed Qe, two sets of magnetic shielding, a valve box, and a cryostat providing a 2 K cryogenic environment for the superconducting cavities. The entire project was undertaken by the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in collaboration with Beijing High-energy Racing Technology Co., Ltd., Ningxia Orient Superconductor Technology Co., Ltd., and Wuxi Innovative Low-Temperature Environment Equipment Technology Co., Ltd. IHEP designed the superconducting cavities and the overall cryomodule, the Beijing High-energy Racing company manufactured the superconducting cavities, Ningxia Orient Superconductor Technology Co., Ltd. supplied high-purity niobium materials and conducted the post-processing of superconducting cavities, and Wuxi Innovative Low-Temperature Environment Equipment Technology Co., Ltd. manufactured the cryostat and valve box.

Double-spoke Superconducting Cavity

RF Design

According to the beam dynamics requirements, the double-spoke superconducting cavity operates in a pulsed mode with a pulse repetition frequency of 25 Hz and a working resonant frequency of 324 MHz. The specific design parameters of the superconducting cavity are listed in Table 1 [4, 9].

| parameter | values |

|---|---|

| Frequency (MHz) | 324 |

| β0 | 0.5 |

| Aperture (mm) | 50 |

| Ep/Eacc | 4.1 |

| Bp/Eacc (mT/MV·m-1) | 9.2 |

| G/(Ω) | 120 |

| R/Q/(Ω) | 410 |

| Operating gradient (MV·m-1) | 7.3 |

| βinput | 0.389 |

| βoutput | 0.526 |

| Pulse width (μs) | 1200 |

| Repetition frequency (Hz) | 25 |

| Duty ratio (%) | 3 |

Field emissions and cavity thermal losses are critical elements for the performance of superconducting cavities [10]. Consequently, the maximum values of the surface electric and magnetic fields are critical [10]. For the accelerating gradient Eacc and quality factor Q of the superconducting cavity to be maximized, lower

The low-duty-ratio pulse state of the CSNS-II linac minimizes heat loss during normal operation, thus reducing the stringent requirements on

Generally, the spoke cavity has a considerable distribution of the transit time factor (TTF) [14]. Within the entire working range of the double-spoke superconducting cavity, the TTF ranges from 0.6 to 0.774, with a maximum TTF of 0.774 at β0 = 0.5. The TTF corresponds to the working energy range of the cavity (β0 from 0.389 to 0.526).

Field emission (FE) is widely recognized for its significant impact on cavity performance, and its effect depends on the quality of surface treatment and cleanliness inside the cavity. If not properly treated, radiation can result, and in severe cases, the cavity may quench. The resolution of this problem largely depends on surface treatment and meticulous cavity assembly [15].

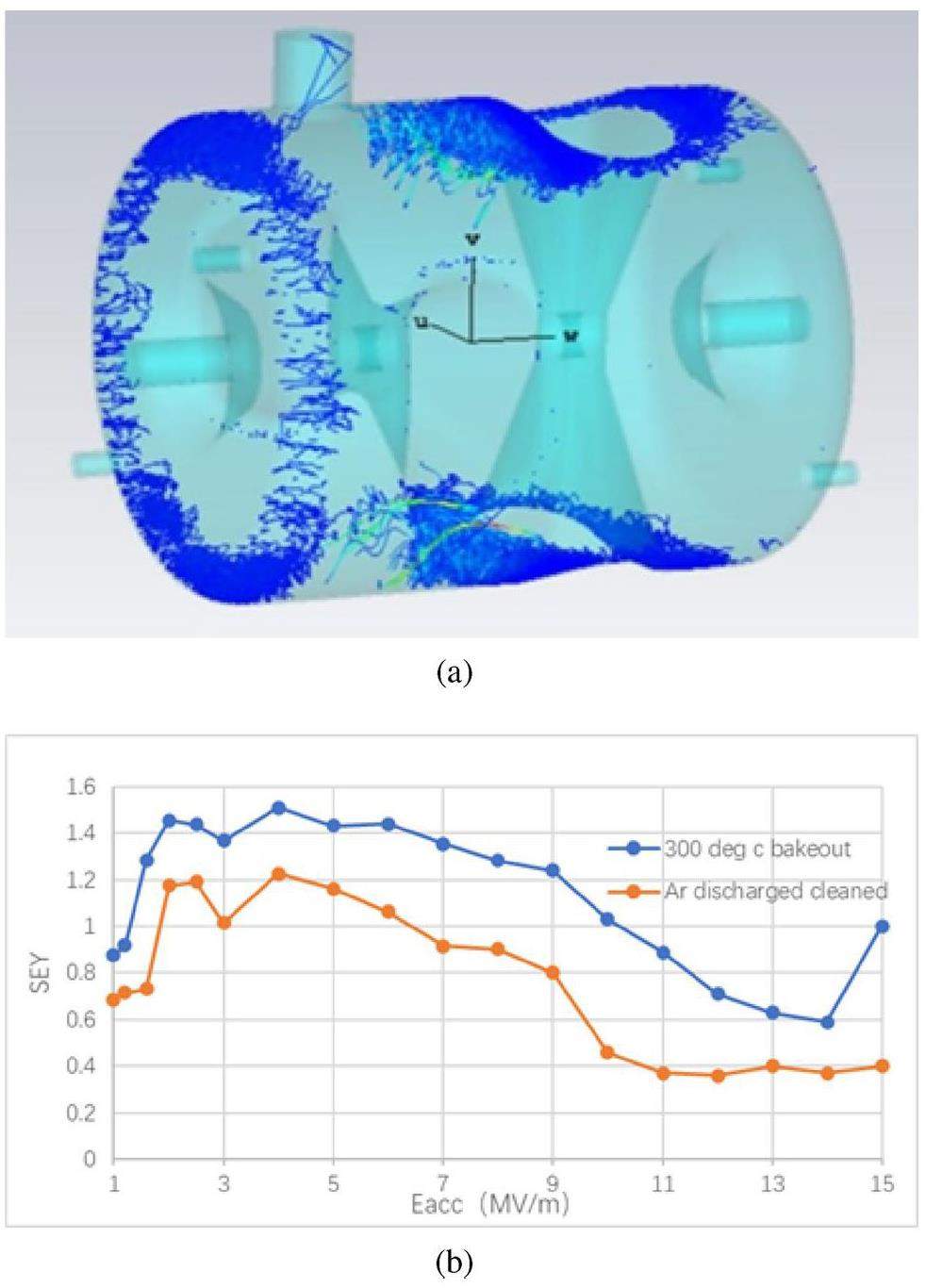

Multipacting (MP) also has a significant impact on the performance of superconducting cavities because the emitted electrons can absorb RF power from the electromagnetic field and collide with the microwave surface [9]. Under specific conditions, the excitation of secondary electrons may increase exponentially. Excessive secondary electrons can significantly absorb the RF power, resulting in a decrease in the electric field. This may cause overheating of the superconducting cavities, resulting in a decrease in Eacc or a thermal breakdown. Therefore, MP should be optimized in the design of superconducting cavities [16, 17].

In the electromagnetic design of the double-spoke cavity prototype, measures such as changing the radius of curvature at the end cap and attempting different niobium materials with diverse surface treatment recipes are used to conduct simulation optimization for MP to ensure that no hard MP exists in the cavity or only soft MP that can be eliminated by high-power conditioning exists [18].

These MP phenomena are located in the magnetic field region and are typically first-order two-point MP. Figure 3 depicts the MP location and significant variation in the secondary electron yield (SEY) values of different surface treatment recipes for a niobium material. At accelerating gradients of 2 and 4 MV/m and SEY below 1.2 with Ar discharged cleaned niobium material, empirical observations suggest that MP can be eliminated using power conditioning [19].

Mechanical Design

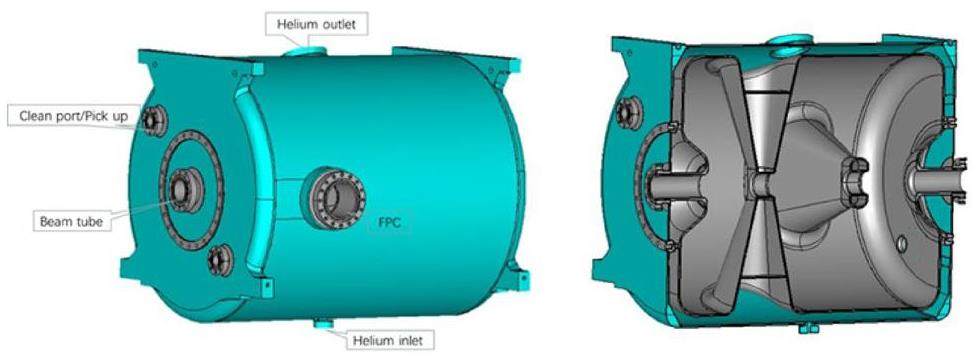

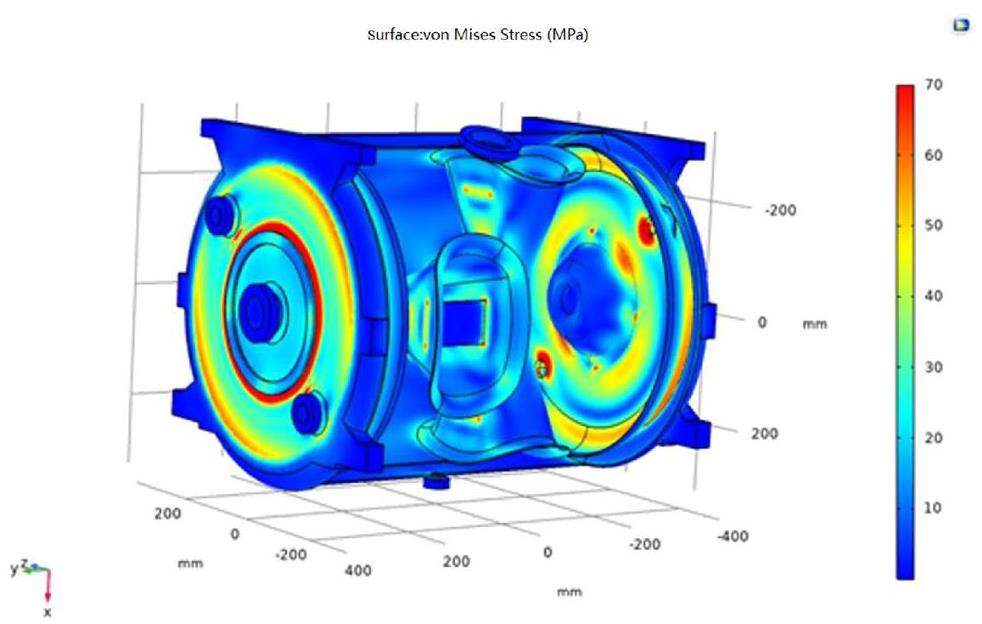

The superconducting cavity must be immersed in liquid helium to achieve a superconducting state and be connected to the helium vessel. Therefore, the design of the helium vessel is closely related to the performance of the superconducting cavity. The specific structure is shown in Fig. 4. The materials used in the various parts are as follows: the cavity is fabricated from high-purity niobium with a thickness of 3.2 mm and RRR = 300, the main material for the vessel is titanium with a thickness of 4 mm, and the end cap of the helium vessel has been locally optimized. The cavity and vessel are welded with a niobium-titanium alloy, and the flanges are created from the same material. The design of the helium vessel primarily considers the prevention of plastic deformation during vacuum leak testing at room temperature, helium pressure sensitivity, tuning sensitivity, Lorentz force detuning (LFD) factor, and mechanical resonant frequency [20, 21].

The multiphysics simulation software CST and COMSOL were used to analyze the mechanical design of the cavity. CST does not require high precision in geometric shapes and has a comparative advantage in electromagnetic simulations, whereas COMSOL demands higher accuracy in geometric models and is more likely to converge when solving the coupling of multiple physical fields [4].

The electromagnetic surface force is generated by the interplay between the induced current and electromagnetic field on the microwave surface of the superconducting cavity [10]. As the gradient increases, the Lorentz force increases accordingly, causing deformation of the cavity in the electric and magnetic field regions and resulting in a decrease in the resonant frequency. Because the superconducting cavity immersed in liquid helium has a very high quality factor Q0, fluctuations in the helium pressure directly affect the cavity’s resonant frequency. Therefore, the helium pressure sensitivity (df/dp) should be optimized. The cavity should have a sufficient tuning range to compensate for the detuning frequency during the surface treatment and titanium vessel welding. Mechanical vibration is another significant contributor to the detuning of the RF frequency.

External vibrations couple with the cavity, exciting the mechanical resonances that modulate the RF resonant frequency and induce ponderomotive instabilities. These translate into amplitude and phase modulations of the field and are particularly significant for a narrow RF bandwidth [10].

Forced oscillations can occur when external vibrations match the mechanical vibration frequencies of the cavity. Generally, the mechanical vibration frequency affecting the superconducting cavity RF frequency should fall outside the danger zone at frequencies below 100 Hz.

According to simulation and optimization calculations, the Lorentz force detuning coefficient of the double-spoke cavity is -12.56 Hz/(MV/m)2, its tuning capability is 100 kHz/10 kN, the helium pressure sensitivity is -0.773 Hz/mbar, and the mechanical vibration frequency affecting the superconducting cavity frequency is 171 Hz [4].

According to the properties of niobium, if the stress of the cavity during pressure leakage detection at room temperature exceeds the maximum stress of the material, plastic deformation of the cavity occurs. In this design, the maximum stress is located at the roots of the clean ports, as shown in Fig. 5. However, this small area may cause a slight change in frequency without significantly affecting the cavity. After the helium tank was welded, a vacuum test was performed, and the plastic deformation of the four rinsing ports was observed to cause the cavity frequency to decrease by only -31 kHz.

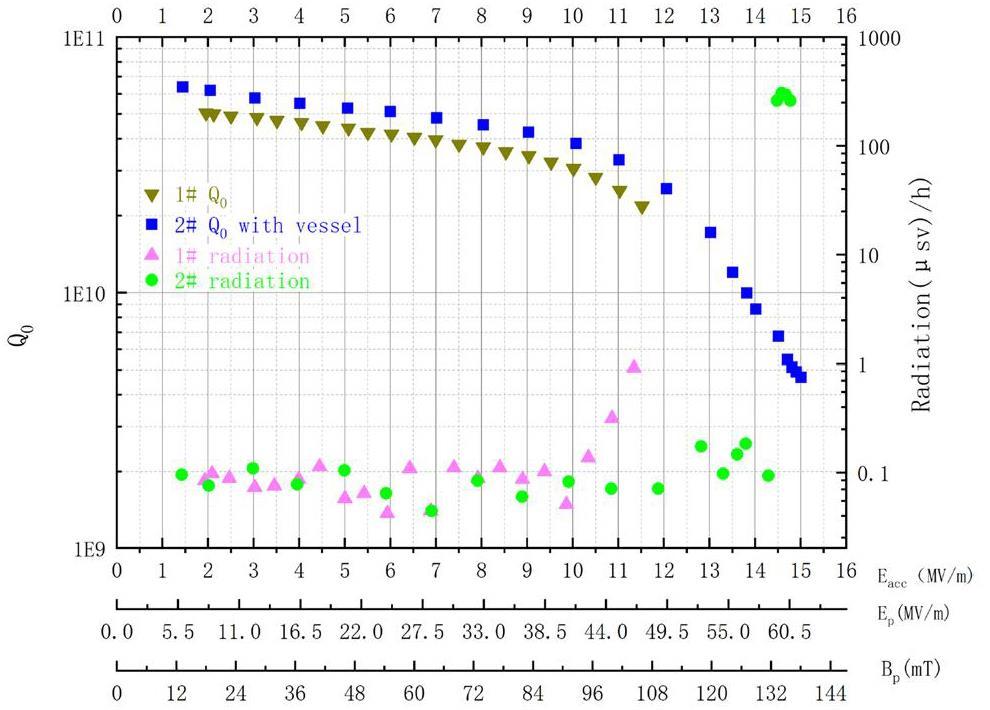

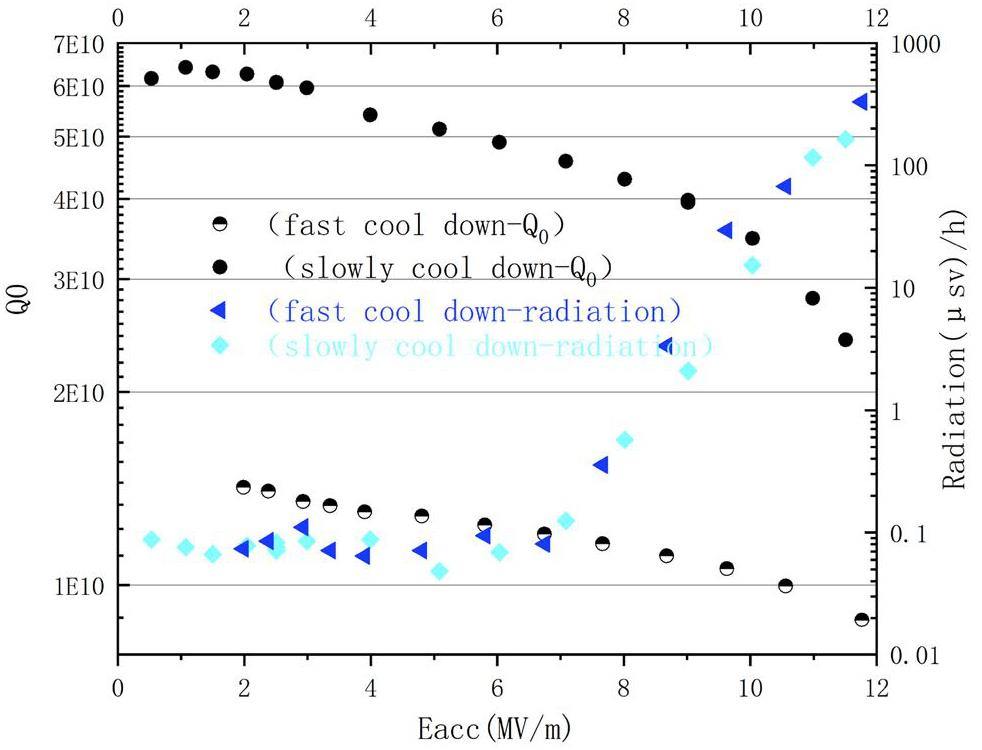

The manufacturing of the two double-spoke cavities was completed in March 2022 and January 2023 (Fig. 6), and post-processing including buffered chemical polishing (BCP) and high-pressure rinsing (HPR) was performed. The vertical tests of the two jacked cavities were performed in November 2022 and July 2023, respectively, at the Platform of Advanced Photon Source Technology R&D (PAPS), achieving maximum gradients of 11.6 and 15 MV/m, with Q0 ≥ 3× 1010 when Eacc ≤ 10 MV/m (Fig. 7).

Tuner

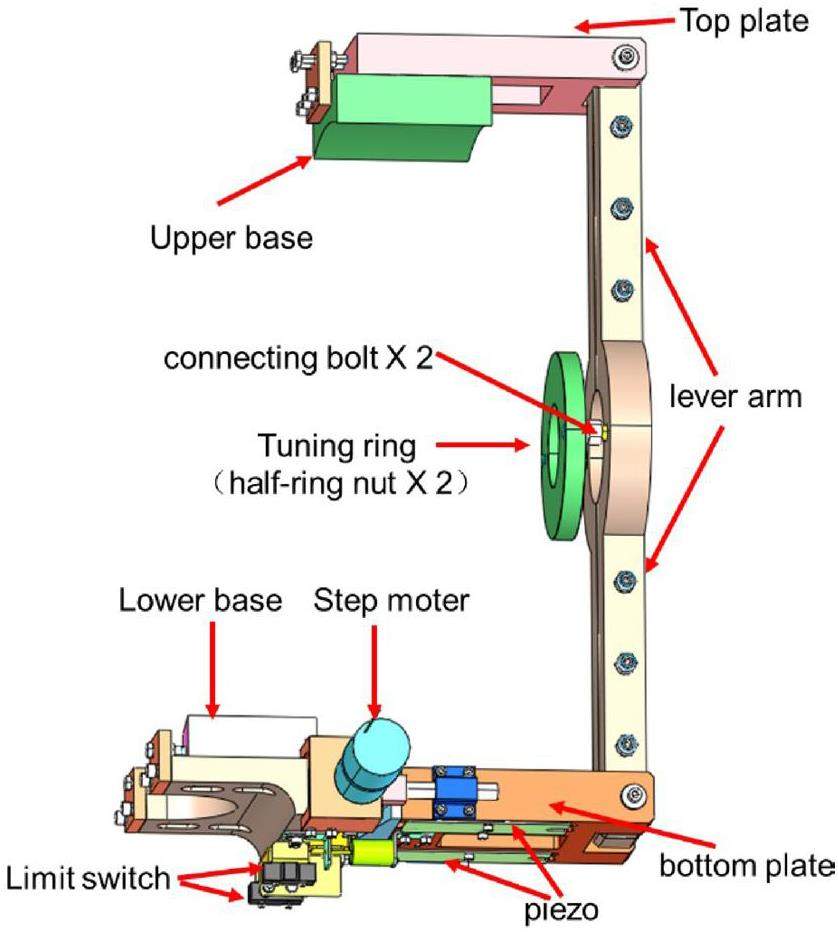

A tuner should be installed on the double-spoke cavity to compensate for the errors in the RF frequency of the superconducting cavity caused by manufacturing, cooling, surface treatment, titanium vessel welding, and Lorentz force detuning. Generally, the principle of tuning involves adjusting the volume of the inductance and capacitance of the acceleration gap. From Eq. 1,

The cone at the end cap is the most sensitive area. In this design, the tuning range is100 kHz/10 kN. The stepper motor stretches the beam tube of the superconducting cavity through the piezoelectric component and tuning force arm. The piezoelectric ceramic deforms differently under different voltages and can achieve axial deformation of the superconducting cavity. For enhanced tuning efficiency of the tuner, the stiffness of the force arm must be maximized to efficiently transmit force from the motor to the tuning ring. The design parameters are presented in Table 2.

| Parameter | Design |

|---|---|

| Slow tuning | |

| Frequency range (kHz) | 100 |

| Distance of motion (mm) | 0.93 |

| Resolution (Hz) | < 5 |

| Stiffness (2 K) (N/μm) | 20 |

| Operation temperature (K) | 5 |

| Fast tuning | |

| Frequency range (Hz) | 1000 |

| Resolution (Hz) | <5 |

| Operation temperature (K) | 5 |

| Response time (ms) | 1 |

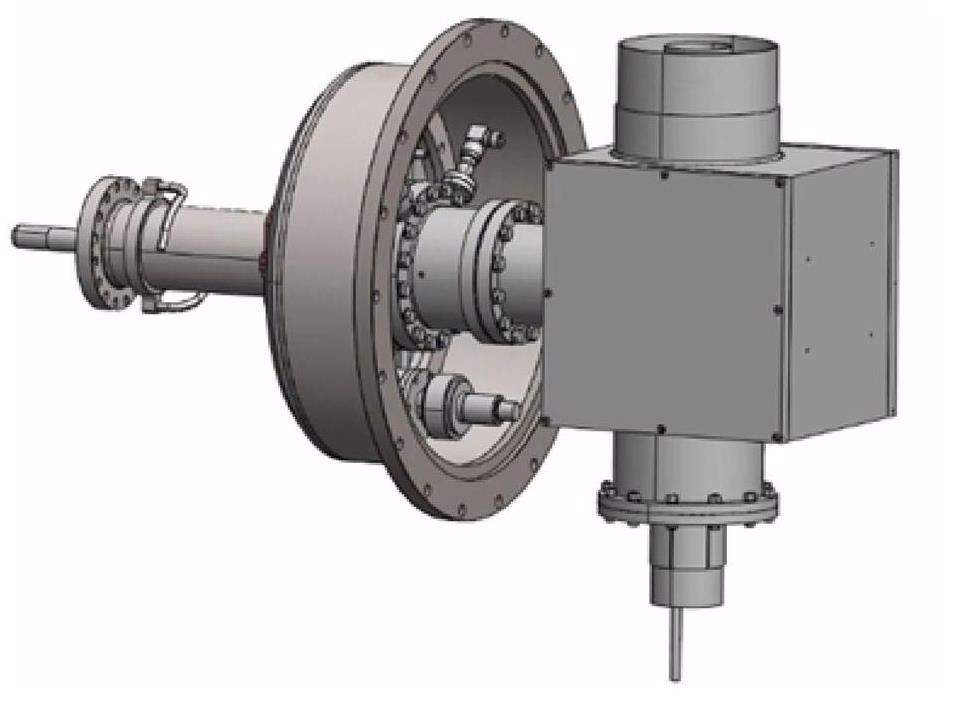

Fundamental Power Coupler

The fundamental power coupler (FPC) is an essential component of the superconducting cavity RF system and is responsible for transmitting the high-frequency power generated by the power source to the superconducting cavity. Another function is to isolate the high-vacuum environment inside the cavity from the atmosphere using a ceramic window [22]. Additionally, it provides a low-heat leak transitional connection from room temperature to 2 K to ensure a low-temperature environment of the superconducting cavity and minimize the impact on the cavity and beam performance as much as possible.

A coaxial-type power coupler with a single window was designed based on the design solutions for similar devices such as SNS, ESS, and J-PARC. Considering the power requirements of the double-spoke cavity and redundancy considerations for other systems, the design target for the coupler is to transmit 250 kW RF power with a duty cycle of 5.75%, satisfying the requirements for the installation of the superconducting cavity, reasonable heat loss, and safe long-term operation. The specific parameters are listed in Table 3 and an external view is shown in Fig. 9.

| Parameter | Design |

|---|---|

| RF Frequency (MHz) | 324 |

| RF peak power (kW) | 250 |

| Pulse width (ms) | 2.3 |

| Repetition frequency (Hz) | 25 |

| Operation temperature (K) | 5 |

| Qe | 2.3×105 |

| Coupler diameter (mm) | 80 |

| FPC angle | Horizontal |

| Assembly requirements | Clean assembly |

| Type | Coaxial-type |

| Ceramic window type | Coaxial disk |

| Coupling type | Electronic coupling |

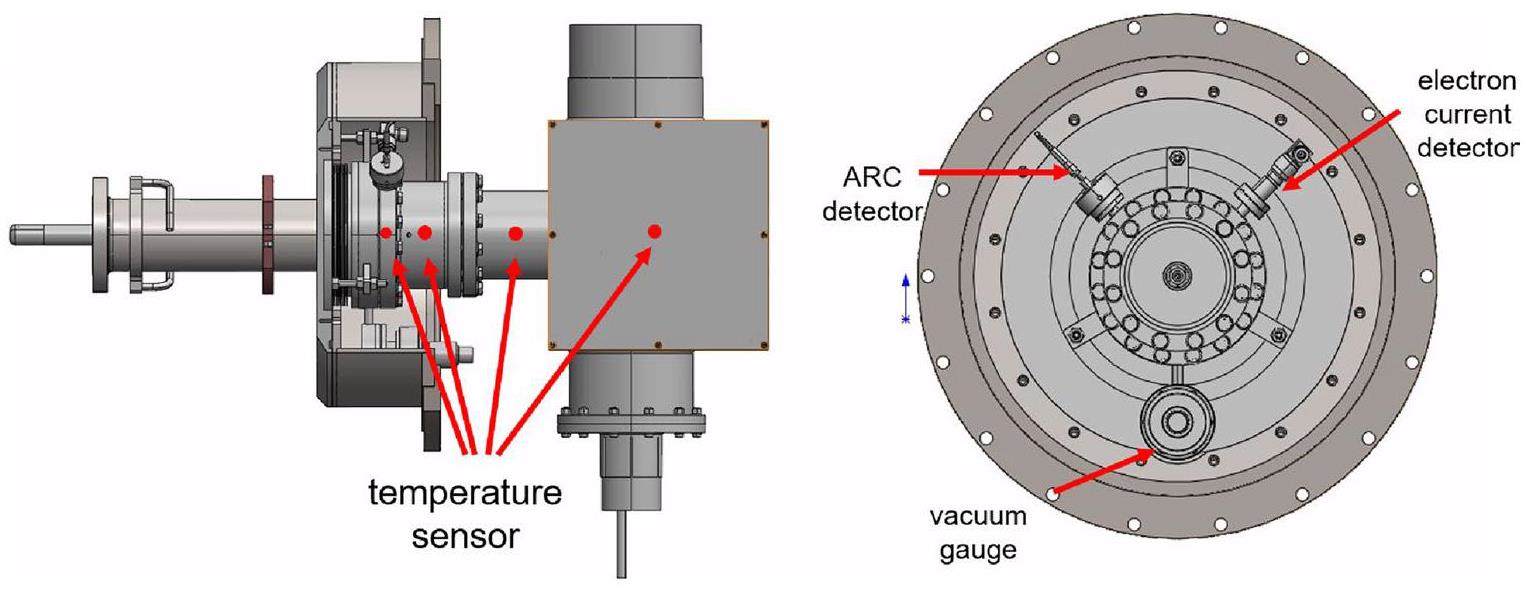

Considering the thermal load and mechanical strength of the coupler under normal operating conditions, we used stainless steel as the outer conductor, with the inner wall coated with several μm of copper. The inner conductor is composed of an oxygen-free copper pillar with a diameter of 22.8 mm, and compressed air is used for cooling inside the inner conductor. The coupler may experience MP phenomena during operation. An electron current detector, arc detector, and vacuum gauge were installed on the vacuum side of the ceramics to protect the ceramics from high-voltage breakdown, as depicted in Fig. 9. Because of the potential for MP phenomena in the coupler, a device for adding a DC bias voltage was retained in the design to suppress MP occurrence, and when necessary, a bias voltage can be added.

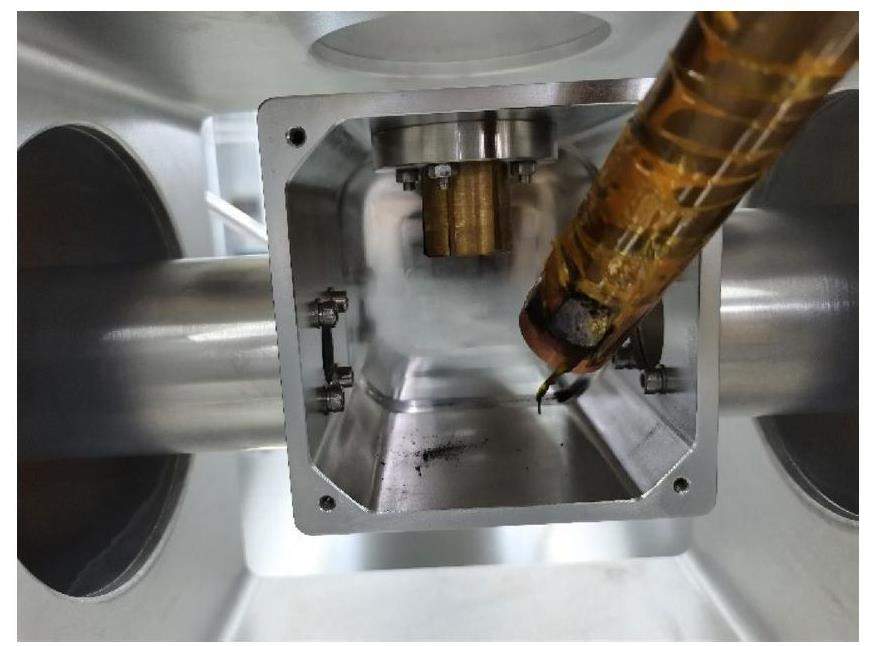

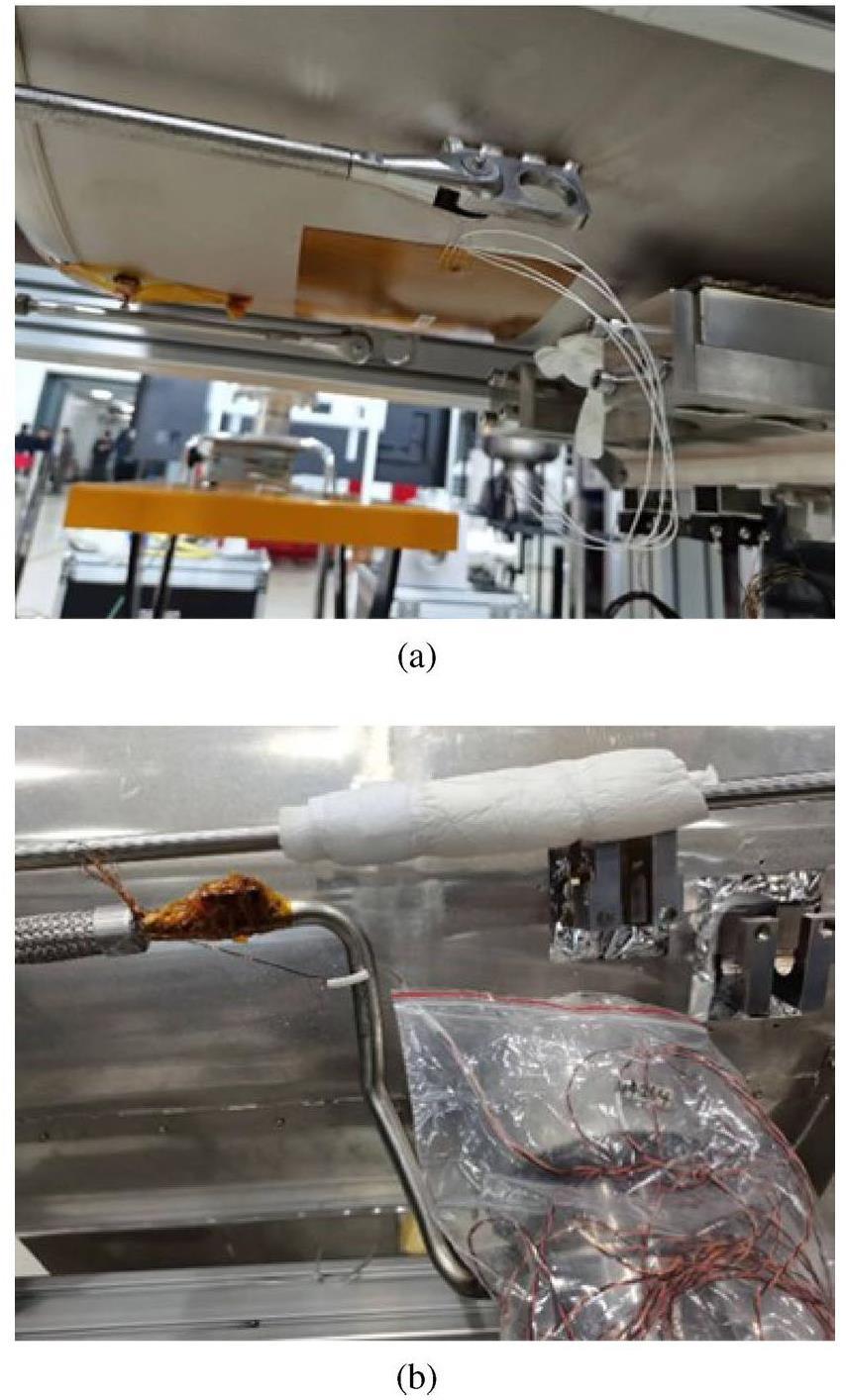

The coupler must undergo thorough cleaning to remove surface-attached dust in a Class 10 clean room before installation. First, the coupler must be subjected to high-power 400 kW traveling- and standing-wave conditioning to remove small spikes that are not easily found during the machining process, and the stability of the ceramic performance must be inspected [23, 24]. During the conditioning process, the temperature of the 1# inner conductor reached 60 degrees, whereas that of 2# increased by approximately 8 degrees. When the coupler was opened, the insulating film used to isolate the inner conductor from the fixed spring was damaged during conditioning (Fig. 10). Perhaps it was already damaged during installation. The film was then replaced with a thicker insulating film to resolve this problem.

Cryostat

The cryostat is the core component of the cryomodule, and it provides a low-temperature environment of 2 K for the superconducting cavity. To streamline the processing and assembly procedures of cryomodules during mass production and to ensure process quality control, we implemented a modular design for the structure of the low-temperature cryomodule [25].

The cryogenic mass of the superconducting cavity and helium vessel in the 2 K temperature zone adopts a rod support structure, which can satisfy the micro-adjustment requirements of the superconducting cavity at room temperature and 2 K. Considering the overall thermal load of the cryostat and quality control requirements for the manufacturing processes, a single-layer 50 K thermal shield structure design has been adopted. This design utilizes a direct cooling method with 40 K cold helium gas extracted from the refrigeration unit. The thermal shield is directly suspended in the 60 K thermal barrier section of the pull-rod support structure. This facilitates the introduction of a thermal barrier cold source through the pull-rod support structure and fully utilizes the excellent mechanical performance of the pull-rod structure. The coupler is mounted horizontally and is a thermally conductive cooling single-window coupler. The helium vessel component is equipped with multiple safety protections, such as a Class 2 safety valve and Class 1 rupture disc, and a vacuum safety valve (micro-positive pressure release) is set on the vacuum container. In the event of extreme overpressure, a Class 1 rupture disk is quickly activated for pressure relief. When the helium pressure reaches the warning pressure but not the extreme pressure, the Class 2 safety valve is activated for pressure relief. A structural diagram of the cryostat is shown in Fig. 11.

The cryostat and local valve box are connected using a set of 7-channel cryogenic pipeline. The pipe sections are equipped with a sleeve structure to facilitate installation and disassembly, enabling horizontal testing and installation within the tunnel. The cryostat was designed with optimized thermal-barrier structures and positions through material selection and structural setup to reduce the overall thermal load on the equipment. The design specifications for the double-spoke cavity cryostat are outlined in Table 4.

| Parameter | Design |

|---|---|

| Insulation vacuum (Pa) | <5×10-2 |

| Pressure capacity of vacuum Chamber (MPa) | 0.1–0.2 |

| Pressure leak rate requirement (Pa m3/s) | <10×-8 |

| Static heat load (W) | 20@2 K |

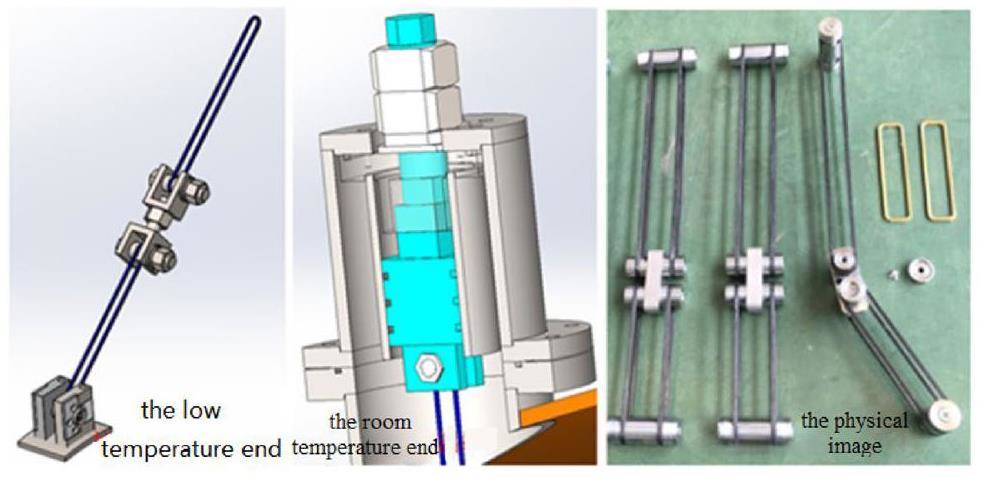

The rod support structure uses a carbon fiber composite material (CFRP, T300) primarily for transport and "self-centered" structural design to ensure that the helium vessel components are concentric at room temperature and low temperature. At the room-temperature end of the rods, three seal O-rings and spring structures were used to ensure sealability and enable helium vessel position adjustment at low temperatures. The installation of a thermal barrier in the middle of the rod support assembly can effectively reduce the thermal load by using the theoretically calculated thermal load of a single set of rods of 0.0025 W @ 4.5 K. Specific structures and actual photographs of the rods are shown in Fig. 12. A similar rod support structure has been successfully applied to the 3W1 superconducting wiggler and superconducting undulator [26-28]. Before the actual assembly, a low-temperature tension performance test was conducted on each set of pull rod components to ensure that the mechanical performance of the pull rods at low temperatures satisfied the design requirements. The test confirmed that each carbon fiber withstood a tensile force greater than 1.5 t.

To ensure the assembly quality and ultra-high cleanliness requirements of core components, such as the superconducting cavity string, beam pipes and couplers were cleaned and integrated in a class 10 clean room. When they were integrated, they were moved to a dedicated assembly fixture for the corresponding pipeline connection, assembly of tuners, magnetic shields, thermal shield components, rod components, two-phase pipe components, temperature sensor components, level gauge components, alignment components, and multilayer insulation packaging, and finally placed into the vacuum chamber. Maintenance holes for the vulnerable parts of the two tuners were provided at the bottom of the outer barrel of the vacuum chamber to facilitate future maintenance. The bottom support component enables the precise adjustment of the cryostat in all directions to satisfy the collimation requirements of the equipment.

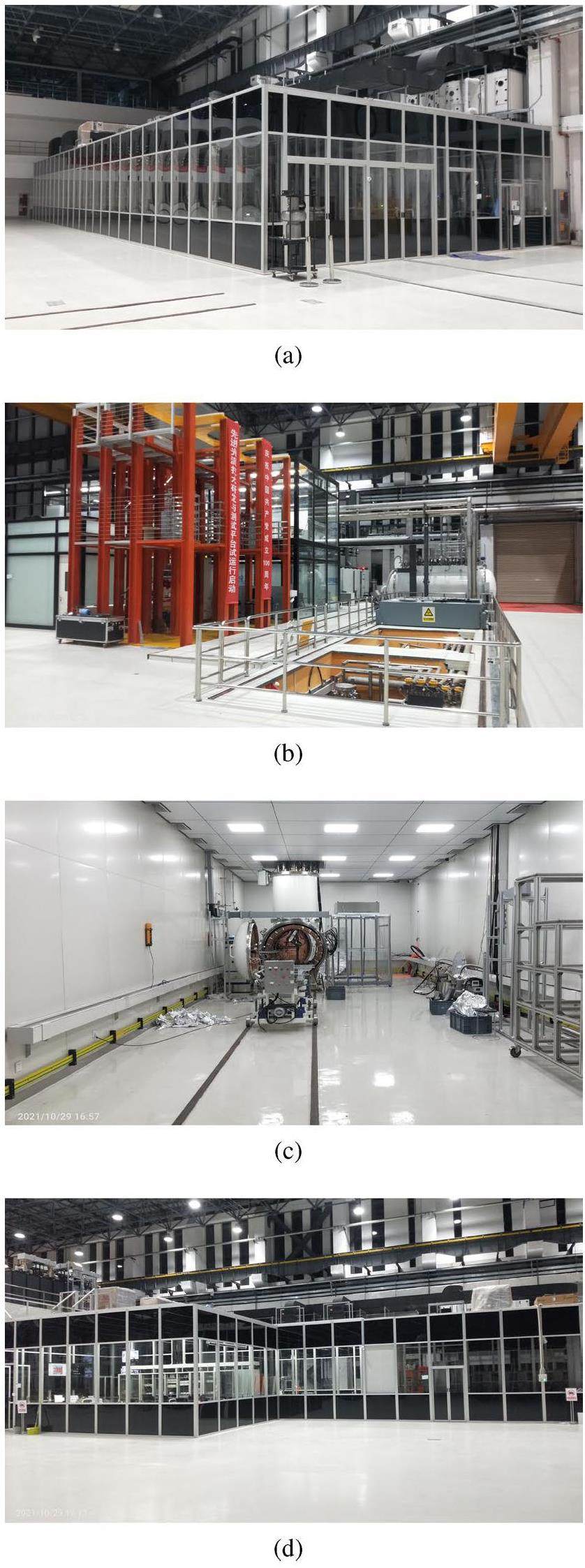

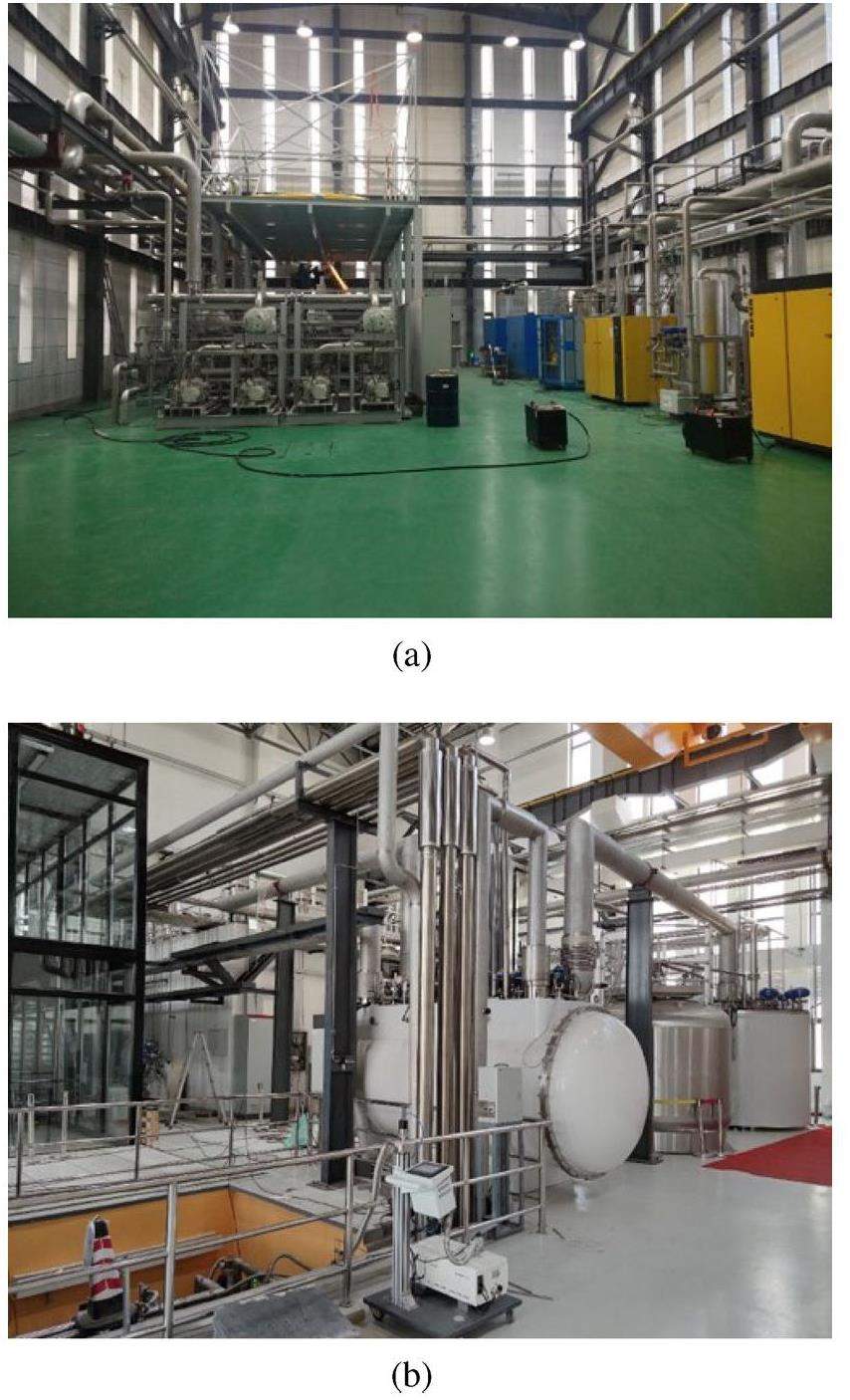

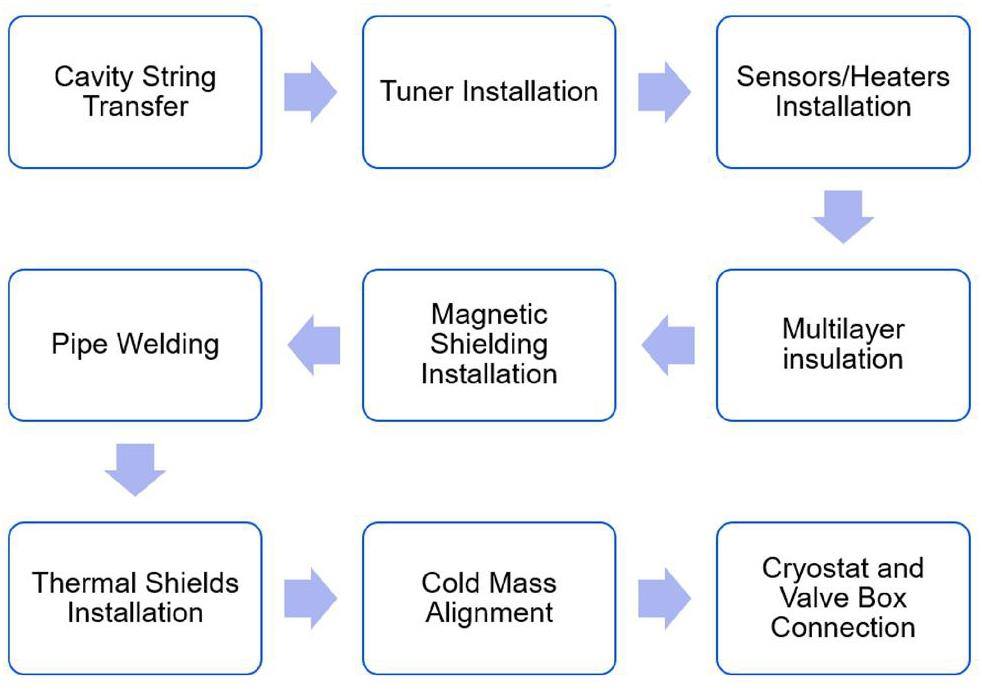

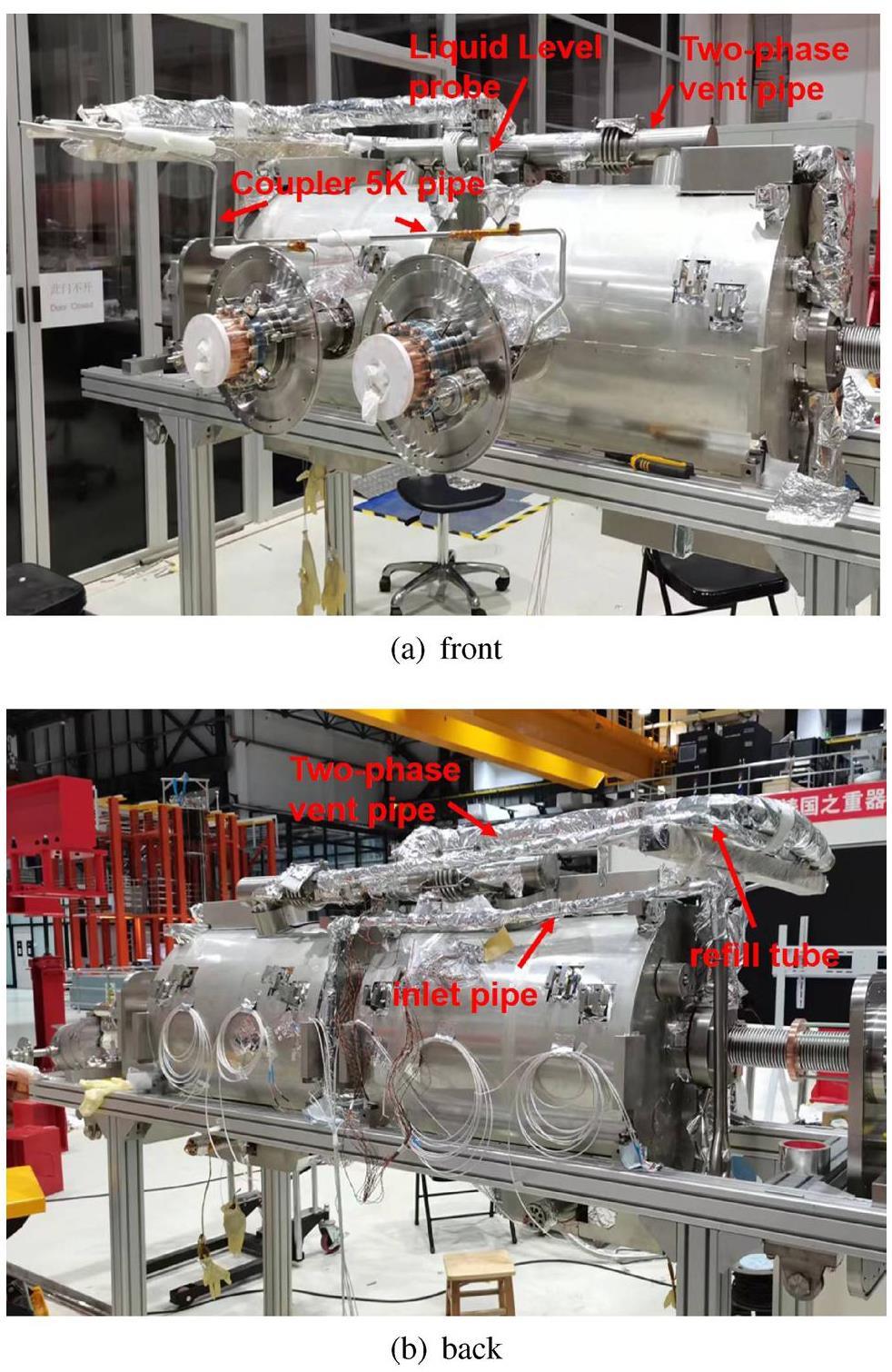

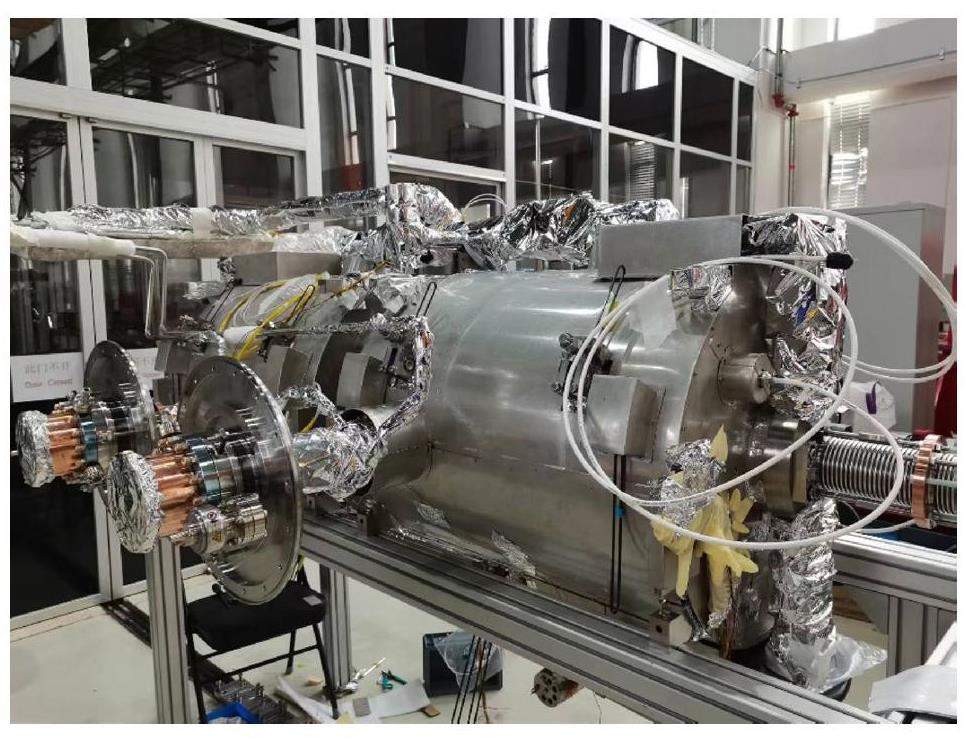

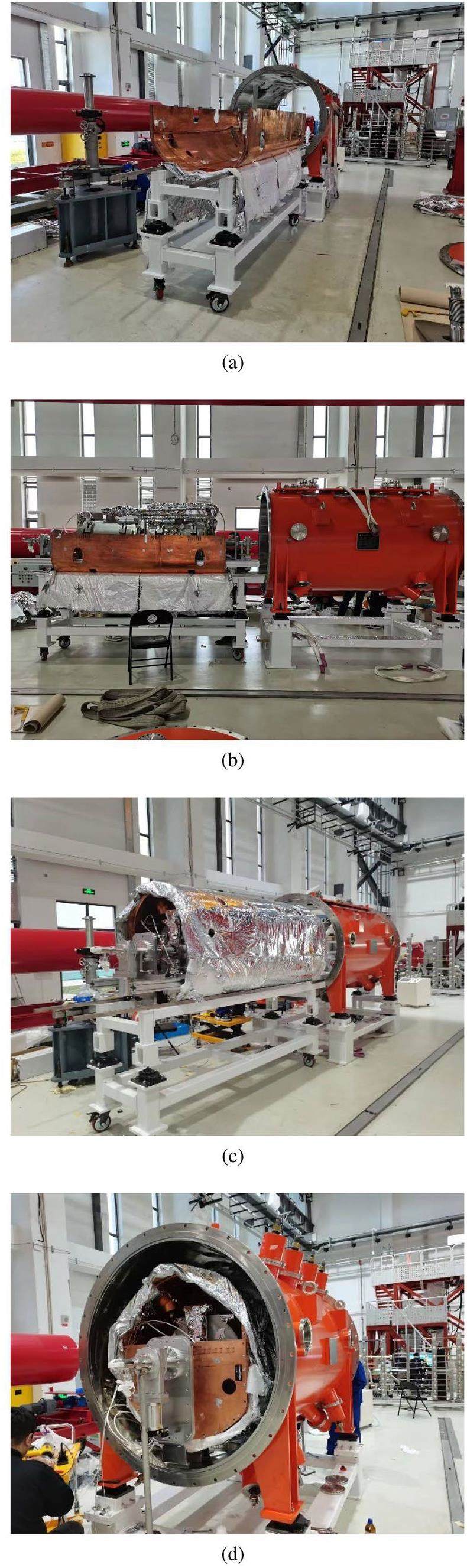

Cryomodule Installation

The cryomodule installation consisted of two steps: clean assembly of the cavity string and cold-mass installation of the cryostat. The clean assembly was performed at PAPS, which included a class 10 cleanroom, coupler assembly cleanroom, vertical test system with three vertical test dewars, horizontal test system with two horizontal test chambers (Fig. 13), and cryogenic system with a capacity of 300 W @ 2 K, as shown in Fig. 14 [29].

Clean Assembly of the Cavity String

Unlike vertical testing, horizontal testing of the superconducting cavity is an important method for verifying the performance of a superconducting cavity under actual working conditions other than beamless scenarios. The horizontal testing results were used to determine whether the performance of the superconducting cavity and cryomodule satisfied the normal working criteria. The horizontal testing system consists of a superconducting cavity cryomodule, power supply system, cryogenic system, low-level test system, power transmission system, and radiation protection system [20, 23].

Generally, the horizontal testing of the superconducting cavity is performed using a generic cryomodule for single-cavity horizontal testing. However, owing to limitations at the PAPS site, the interface between the generic cryostat and the double-spoke cavity is significantly different, requiring significant modifications to the generic cryostat. Furthermore, conflicts with the horizontal testing schedules for superconducting cavities in other projects should be considered. Considering the time constraints of the CSNS-II pre-research phase, we decided to build a dedicated cryostat for the horizontal testing of double-spoke cavities and to construct a valve box to match the cryogenic system with the cryostat.

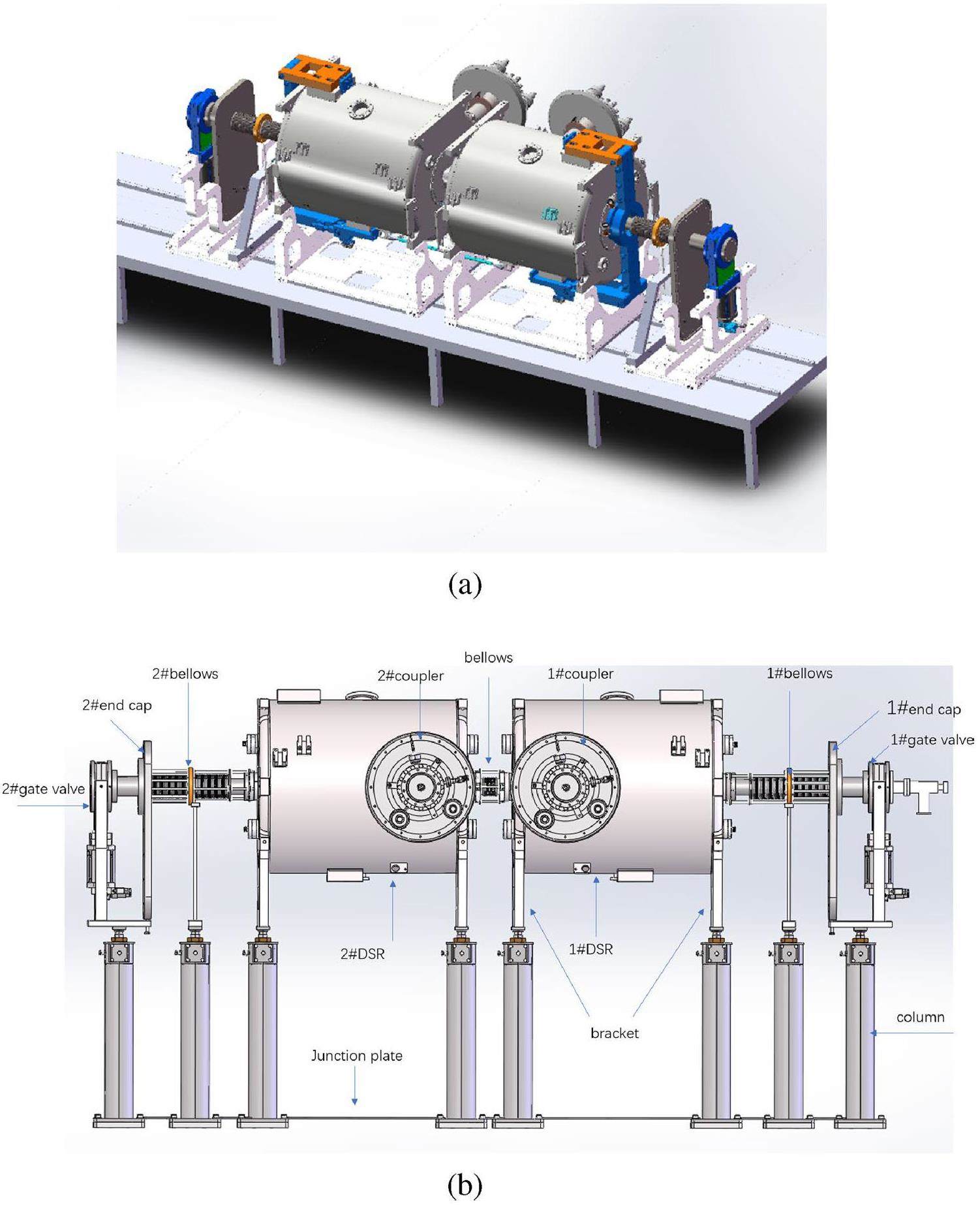

Depending on the physical design requirements of the beam dynamics, each double-spoke superconducting cavity cryomodule consists of two double-spoke cavities, two sets of 250 kW power couplers [30], one set of signal acquisition systems, one set of vacuum systems, one set of cryogenic pipelines, and one cryostat.

Design of the Double-Spoke Cavity String Assembly Fixture

In contrast to single-cavity vertical testing, the assembly of a superconducting-cavity cryomodule involves connecting two double-spoke cavities with bellows and assembling the couplers, end-cap bellows, and gate valves to form a cavity string. Numerous devices have increased the difficulty of clean assembly processes. Because the existing vertical testing fixture cannot satisfy the clean assembly requirements of a cavity string, a specific fixture must be designed for the assembly.

The design requirements for the cavity string fixture are as follows: 1. Satisfy the HPR requirements of a single-jacketed cavity. 2. Facilitate installation of the coupler. 3. Provide sufficient support to prevent tilting or swinging of heavy cavities. 4. Enable clean installation between cavities and between cavities and bellows. 5. Enable easy transportation out of the cleanroom.

Based on the design experience of the 325 MHz single-spoke cavity of the accelerator-driven subcritical systems (ADS) project [31-33], the Circular Electron Positron Collider (CEPC) 650 MHz two-cell elliptical cavity cryomodule [34-36], and the 1.3 GHz nine-cell elliptical cavity string assembly, the installation of the cavity string currently involves two methods: a. Cart-style fixture (Fig. 15 a). b. Column-style fixture (Fig. 15b).

Based on the comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of the two solutions, the cart-style fixture is generally used for cavities with relatively large weights, whereas the column-style fixture is more commonly used for lighter cavities. The single double-spoke cavity (with vessel and coupler) weight is approximately 200 kg, whereas the shear force on a single column on the double track is 200 kg/m, with a compression resistance of approximately 3-4 t. By using two columns to support one cavity, no problem occurs with the load-bearing capacity. Additionally, the column-style solution enables easier adjustments in various directions. Based on prior experience in assembling the nine-cell elliptical superconducting cavity strings, column-style solution was ultimately adopted.

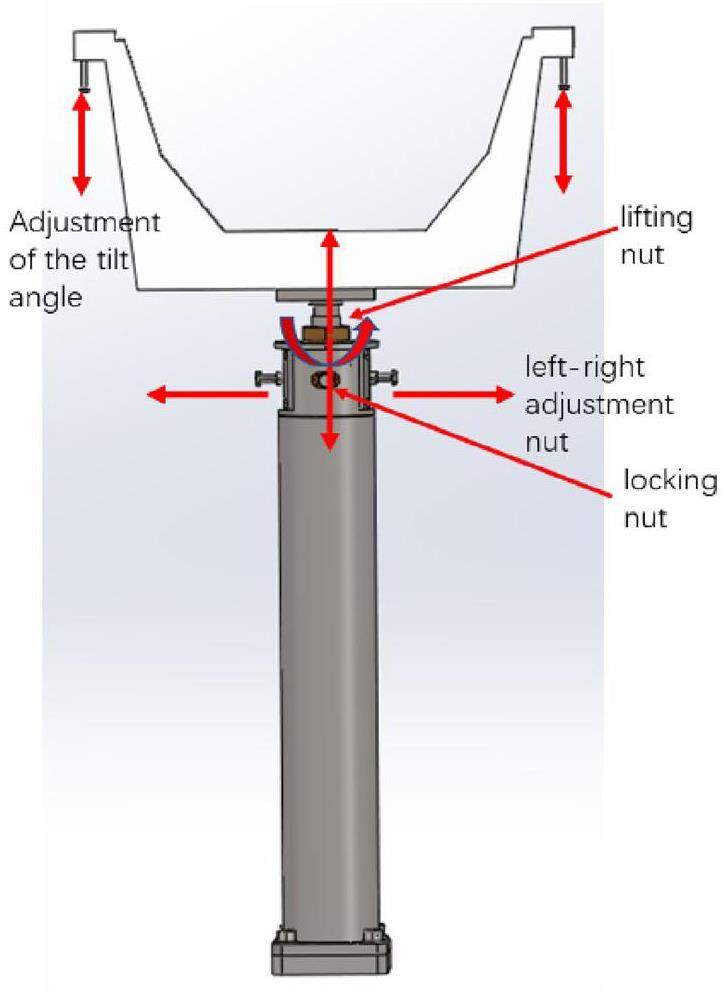

The design diagram of the column-style solution is shown in Fig. 16. A single column, combined with a cavity bracket, enables adjustments in the vertical, horizontal, rotational, and tilting angles, with the column mounted on sliders on the double track, fully satisfying the requirements for clean assembly of the cavity string. After the cavity string is assembled, steel plates will be used to connect the columns and fix the relative position of the string.

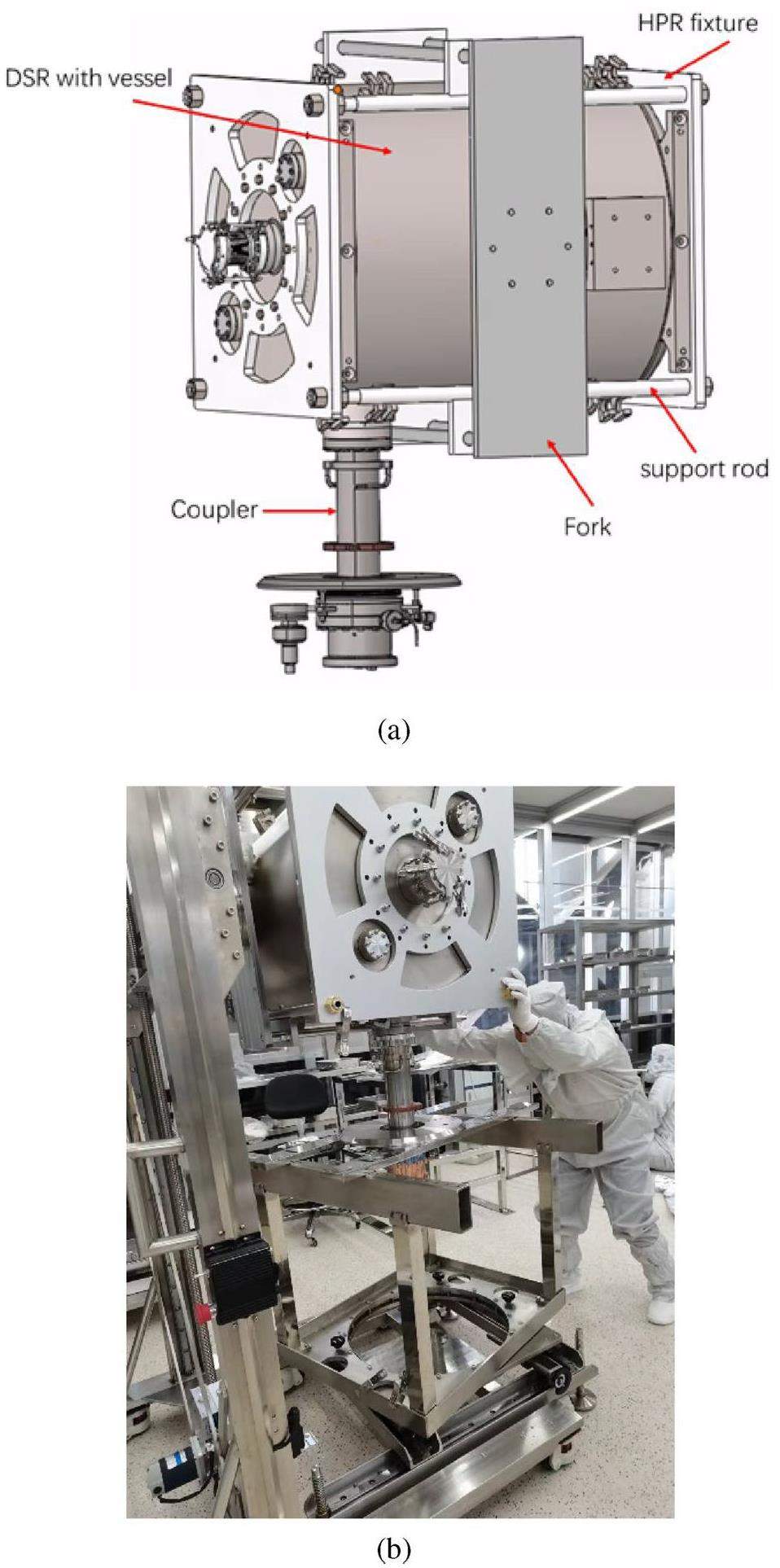

High Pressure Rinse (HPR) for Cavity

Before cavity string assembly, the microparticles had to be removed from the microwave surface to reduce the field emission caused by particle contamination to improve the performance of the entire cavity. The current common method uses high-purity water to wash the microwave surface. According to references [37, 38], the water pressure was set to 10 MPa with a flow rate of 16 L/min, and the electrical conductivity of pure water

Because the jacketed cavity weighs approximately 150 kg and the rinsing port has an eccentric design, if a cavity-rotated platform is used for the HPR process, additional counterweights are necessary, resulting in a total weight of approximately 200 kg. This places a significant load on the HPR platform and rotation system. During rotation, the relative movement of the cavity and spray rod may easily occur, presenting the possibility of collision and posing a significant safety risk to the cavity surface. Therefore, a platform for fixing the cavity and rotating the spray rod is employed to minimize the probability of these problems occurring during HPR, with two motors controlling the up-down and rotational movements of the spray rod. The actual installation is shown in Fig. 17.

Because of the close relationship between the HPR effect and the distance from the nozzle to the cavity wall, as well as the number of HPR repetitions [37], two rinsing ports are incorporated on each end cap when designing the cavity. During the actual HPR, each rinsing port and beam tube port must be rinsed to ensure no blind spots inside the cavity. Flushing at a certain point lasts for several seconds can cause localized oxidation of the cavity wall [37]. Therefore, during the rinsing process, the spray rod must rotate at a rate of 5 r/min and move up and down at a rate of 30 mm/min to avoid excessively long local rinsing times. The nozzle adopts a vertical spinning structure with nine nozzles of diameter 0.6 mm distributed in three layers, with three nozzles on each layer. The bottom layer of the nozzle sprays downwards at a 30-degree angle, the middle layer sprays horizontally, and the top layer sprays upwards at a 50-degree angle [4]. The three nozzle layers are evenly distributed in the horizontal plane to achieve the best rinsing effect.

Before the HPR process, the exterior surface of the cavity and flange-sealing surfaces should be wiped with a solution of Liquinox and rinsed with pure water. During cleaning of the exterior surface, the sealing surfaces of each flange must be carefully inspected to ensure that they are intact. Irregularities, scratches, or small dents should be promptly polished and cleaned to prevent vacuum leaks during clean assembly and horizontal testing. The entire cavity HPR process requires approximately 10 h for completion. After rinsing, each port is covered with a blind plate and secured using two clamps.

Installation of the Cavity Coupler

After the cavity HPR process, the coupler should be sealed and installed. Before installation, the coupler must undergo RF conditioning to verify whether the ceramic can withstand high-power applications and reduce the probability of pollution [39-41]. This is aimed at minimizing the likelihood of cavity contamination caused by outgassing during low-temperature testing. After conditioning, the interior surface of the coupler should be wiped clean with alcohol to ensure the absence of any particle residue before installation in the superconducting cavity.

To operate the cavity at 9 MV/m, which is optimized using beam dynamics, we adjusted Qe of the coupler to 5× 105 by modifying the seal ring thickness.

During installation, to prevent residual dust from the coupler from falling into the cavity and causing contamination, the coupler port of the cavity must be oriented downwards, and the coupler’s flange should be installed facing upward. This slowly lowers the cavity, enabling the flange of the cavity to gradually mate with the flange of the coupler. The screw hole position should be adjusted, and when the seal ring enters the sealing groove, the forklift should be stopped, and the coupler fixture should be slowly raised to ensure that the seal ring tightly fits into the sealing groove of the cavity. At this point, the four screws can be inserted symmetrically and slowly tightened, and the remaining screws should be inserted. The flange has a diameter of 130 mm and is secured using 16 stainless steel screws of M8 size. The screws should be tightened symmetrically to a torque of 6-10-15-21 N.m. When installed, the coupler should only be placed downwards or horizontally. Placing the coupler above the cavity is strictly prohibited. This process is illustrated in Fig. 18.

When the seal is intact, the cavity can be rotated by 90 degrees (with the coupler not facing upward), and the four wheels of the fixture can be installed on the HPR fixture base. The support rods of the fixture should be loosened and the coupler should be rotated horizontally by 90 degrees to be placed in the opposite direction of the forklift. The cavity can then be laid flat on the column of the cavity string with a forklift, and the base of the column should be secured using a connecting steel plate. Subsequently, the next cavity HPR and coupler installations can be performed.

Installation of the End Bellows Assembly

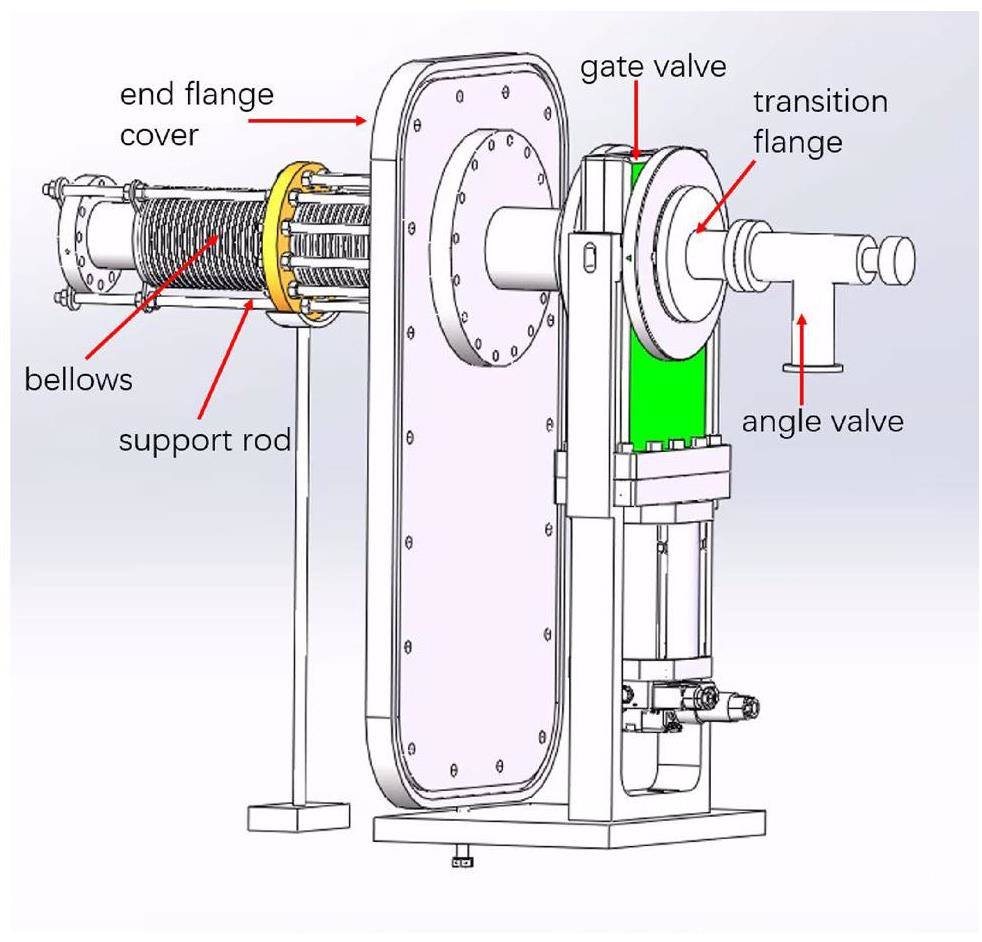

The end bellows serves as the transition section connecting the cavity string to the cryostat. It includes the bellows, the cryostat end-flange cover, gate valve, transition flange, angle valve, and other equipment (Fig. 19). Owing to the complex structure of the bellows, cleaning the internal dust completely is difficult. Therefore, before the clean assembly, it should undergo thorough ultrasonic cleaning, with special attention given to protecting the sealing edges during the ultrasonic treatment. Because the complex structure makes nitrogen blow-drying challenging, if necessary during the sealing test, a heat lamp should be used to accelerate vacuum extraction.

During installation, filtered nitrogen was used to thoroughly blow the interior of the bellows, gate valve, and transition flange until the particle counter reads zero. The bellows was supported at both ends with support rods during installation to prevent excessive stretching and deformation during vacuum pumping (Fig. 19). After the installation of the bellows assembly, it was placed on the cavity string assembly fixture and secured in place [42].

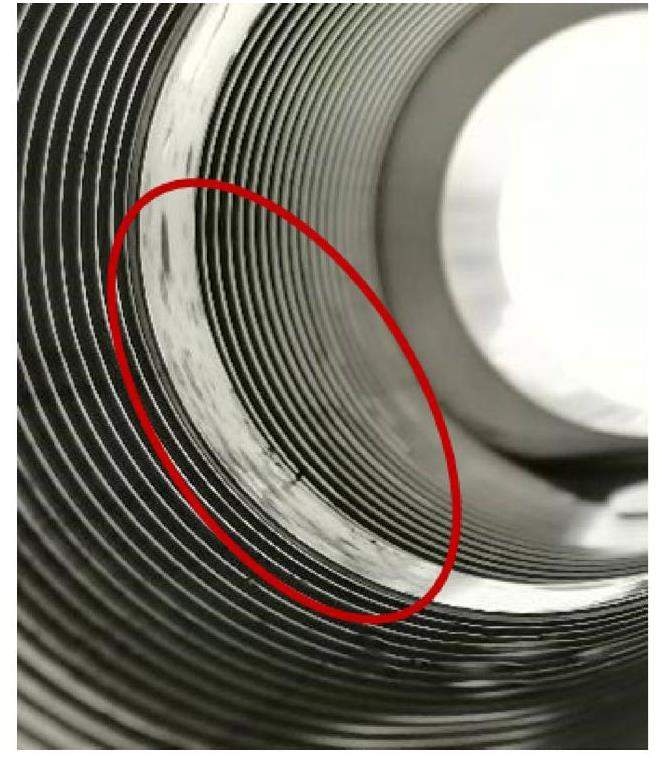

During the installation, some contaminants were observed inside the bellows after ultrasonic cleaning (Fig. 20), which cannot be removed through alcohol wiping and appear to be adhesive-like substances. The component was cleaned thoroughly after returning it to the factory.

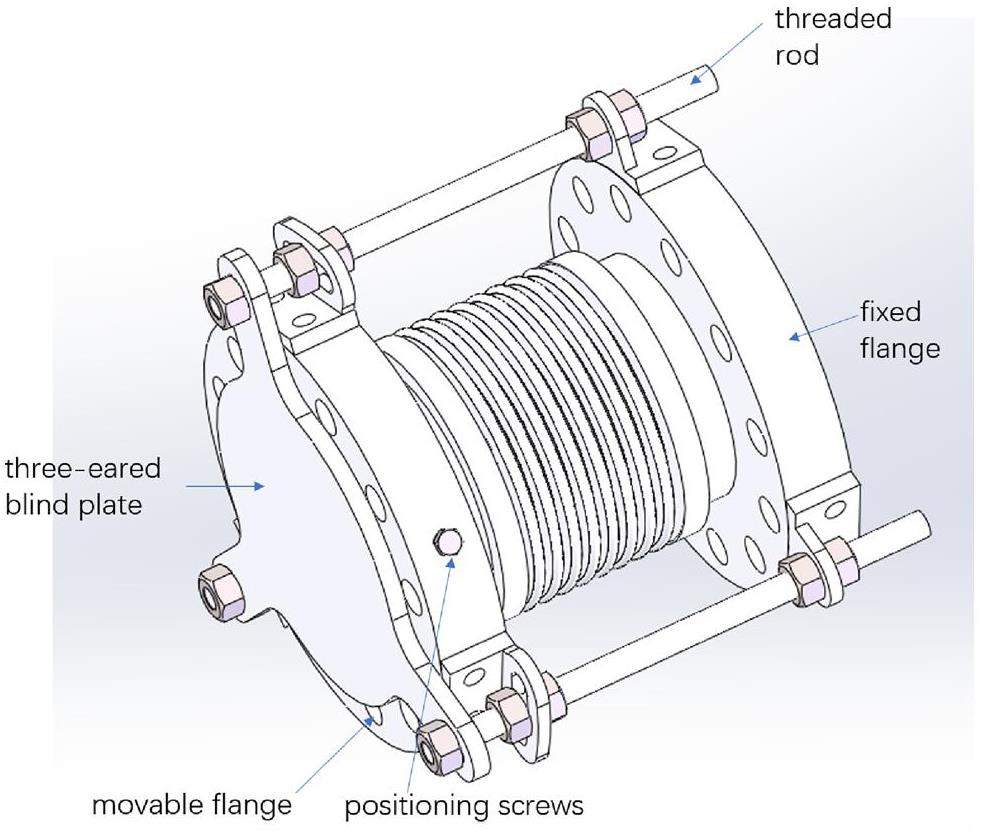

Assembly of the Cavity String

After placing the two cavities and two end-bellows components on the cavity string assembly fixture, the cavity string can be assembled. First, the two cavities should be aligned. The flange of the 1# cavity has a 100 mm long three-ear bellows (Fig. 21) for adjusting the distance between the two cavities, which is installed on the beam tube after the HPR of the 1# cavity. When aligning, the 1# cavity with the bellows should be moved slowly to the flange of the 2# cavity. The positioning screws of the bellows flange should be loosened to align the screw holes of the positioning flange with those of the 2# cavity flange until the bolts can pass freely through the screw holes, and then the positioning screws should be tightened. The sealing ring should be gently placed into the sealing groove of the 2# cavity flange, the blind plate on the bellows removed after 10 s, and then the 1# cavity slowly moved to tightly fit the two flanges together, pressed by hand. The half-ring nut is placed into the flange nut slot, and the screws are inserted and tightened with a torque of 6-11-16-20 N⋅ m. Finally, the steel plate between the pillars is fixed to prevent displacement between the two cavities.

Subsequently, the 1# end bellows component should be slowly moved to the outer side of the 1# cavity to the flange of the beam tube, and the bellows flange aligned with the cavity flange in the same manner as aligning both cavities, except that the half-ring nut must be replaced with the half-ring nut of the tuner, which is the tuning point of the tuner. The same operation should be performed to connect the 2# end bellows component to the 2# cavity. The complete assembly of the cavity string is shown in Fig. 22.

Pressure Leak Testing of the Cavity String

After the assembly of the cavity string was completed, evacuation and pressure leak testing on the cavity string to prevent vacuum leakage during low-temperature testing were necessary. Each cavity has a volume of 140 L, with a total of 280 L for the two cavities, and an additional 200 L for the associated vacuum tube, totaling 480 L. To prevent dust from adhering to the bellows from floating into the superconducting cavities owing to overly rapid pumping during evacuation, the vacuum should be slowly pumped at a rate of 1600 mL/min. Because the superconducting cavities were cleanly assembled immediately after HPR, they were still in a moist state, which prolonged the evacuation time. Based on the previous vacuum-pumping statistics, it took approximately 12 h to evacuate the cavity string.

The vacuum pumping and pressure leak detection equipment used in the clean room is an automated system that consists of a slow pumping system, controller, mechanical pump, molecular pump, and leak detector.

When the cavity is connected to automatic leakage detection equipment, a pumping program is initiated. The program automatically starts with a mechanical pump, molecular pump, leak detector, and various control valves. The first to start is the mechanical pump, and when the vacuum in the cavity falls below 30 Pa, the fast pumping phase begins with the automatic activation of the molecular pump. When the vacuum reaches 1×10-2 Pa, the leak detector begins operating. When the vacuum leak rate reaches 11×10-10 mbar·L/s, a helium gun can be used to perform leak detection on each sealing surface and ceramic by spraying helium gas. If the leak rate variation is less than 21×10-10 mbar·L/s above the background level, the cavity is considered leak-free. During the leak testing, the leak rate of the cavity string is 51×10-11 mbar·L/s, confirming that the cavity will not leak under 2K cryogenic environment.

After the vacuum leak detection of the cavity string, it can be moved out of the clean room to prepare for the next step of cryomodule assembly. Because the cavity string fixture uses a sliding rail system, moving the entire cavity string out of the clean room is very easy and convenient, which is a significant improvement over the previous CEPC 650 MHz superconducting cavity string Cart-style method.

Cold mass assembly of the double-spoke cavity cryostat

The cryostat assembly includes the installation of tuners, cryogenic pipes, sensors, multilayer insulation, a magnetic shield, a thermal shield, and a valve box. The entire process is shown in Fig. 23. The main assembly method involves mounting the cavity string with the associated equipment on a frame and then transporting it onto a horizontal transfer vehicle equipped with a pair of rails. After installing a thermal shield on the transfer vehicle, it was moved into the interior of the cryostat. Subsequently, the entire cavity string was suspended in a cryostat using 16 sets of carbon fibers.

Cavity String Transfer

Following the removement from the clean room, the cavity string must be transferred to a frame for the installation of the associated equipment. The first step is alignment, using the coupler center as a reference to determine the distance between the two cavities and fixing the spacing of the two cavities with two bottom connecting rods. Subsequently, the frame is secured to the eight pins of the two cavities through screws, and end-bellows assembly supports are installed on the frame. The frame is then lifted using a crane or lift, separating the cavity string from the eight columns, removing the column and its fixtures, and placing the frame flat on the ground after installing four support legs. Thus, the transfer from the cavity string fixture to the cryostat fixture is completed.

Tuner Installation

The tuner, a core component controlling the cavity frequency, is composed of slow-tuning mechanics controlled by a stepping motor and fast-tuning mechanisms controlled by piezoelectric ceramics (Pizeo) [43, 44]. The tuner is connected to the superconducting cavity through the upper and lower bases and a tuning ring. The movement of the tuning ring is driven by the outward movement of the lever arm, which changes the position of the tuning ring, thereby altering the displacement of the cavity beam tube flange and causing a change in the accelerating gap capacitance of the cavity, consequently increasing the resonant frequency of the cavity.

During installation, the top plate was first fixed to the upper base of the helium vessel, and the lever arm was then connected to the top plate through a connecting shaft. The bottom plate was then connected to the lower base of the helium tank and lever arm through a connecting shaft. During clean assembly of the cavity string, the tuning rings were fixed to the beam tube flanges of the superconducting cavity. Finally, the lever arm was secured to the tuning ring using two connecting bolts. To ensure that piezoelectric ceramics operate in the linear range, a certain preload must be applied to the lever arm. Additionally, an excessive preload that may cause plastic deformation of the cavity should be avoided. During the adjustment, the change in frequency must be constantly monitored. According to the test data, the cavity does not undergo plastic deformation at room temperature when the frequency increases by 10 kHz.

Installation of Cryogenic Pipes, Heaters, and Sensors

Before entering the cryostat, the cavity string must have cryogenic pipes installed, including the return gas pipe, topping-up pipe, inlet pipe, coupler 5 K cooling pipe, and liquid-level probe pipe [45] as shown in Fig. 24. Because these pipes operate at relatively low temperatures (2 K – 5 K), their sealing should be ensured. The inlet port connected to the helium tank and return gas pipe flange adopt an indium wire sealing scheme, whereas other areas where the pipes meet are welded. After each set of welds, room-temperature vacuum leak and low-temperature liquid nitrogen leak tests were conducted.

To monitor the temperature of superconducting cavities during the cooling and warming processes, appropriate temperature sensors [46] and heaters should be installed (Fig. 25). Four thin-film heaters, four cavity temperature sensors, four two-phase pipe temperature sensors, two topping-up pipe temperature sensors, two 5 K pipe temperature sensors, two tuner motor temperature sensors, two piezoelectric ceramic temperature sensors, two magnetic shielding temperature sensors, two coupler thermal anchor temperature sensors, two end-bellow thermal anchor temperature sensors, and two upper and lower cold shield temperature sensors must be installed in the two cavities. During installation, damage to the sensors must be carefully avoided. Different temperature sensors should be installed based on the installation process.

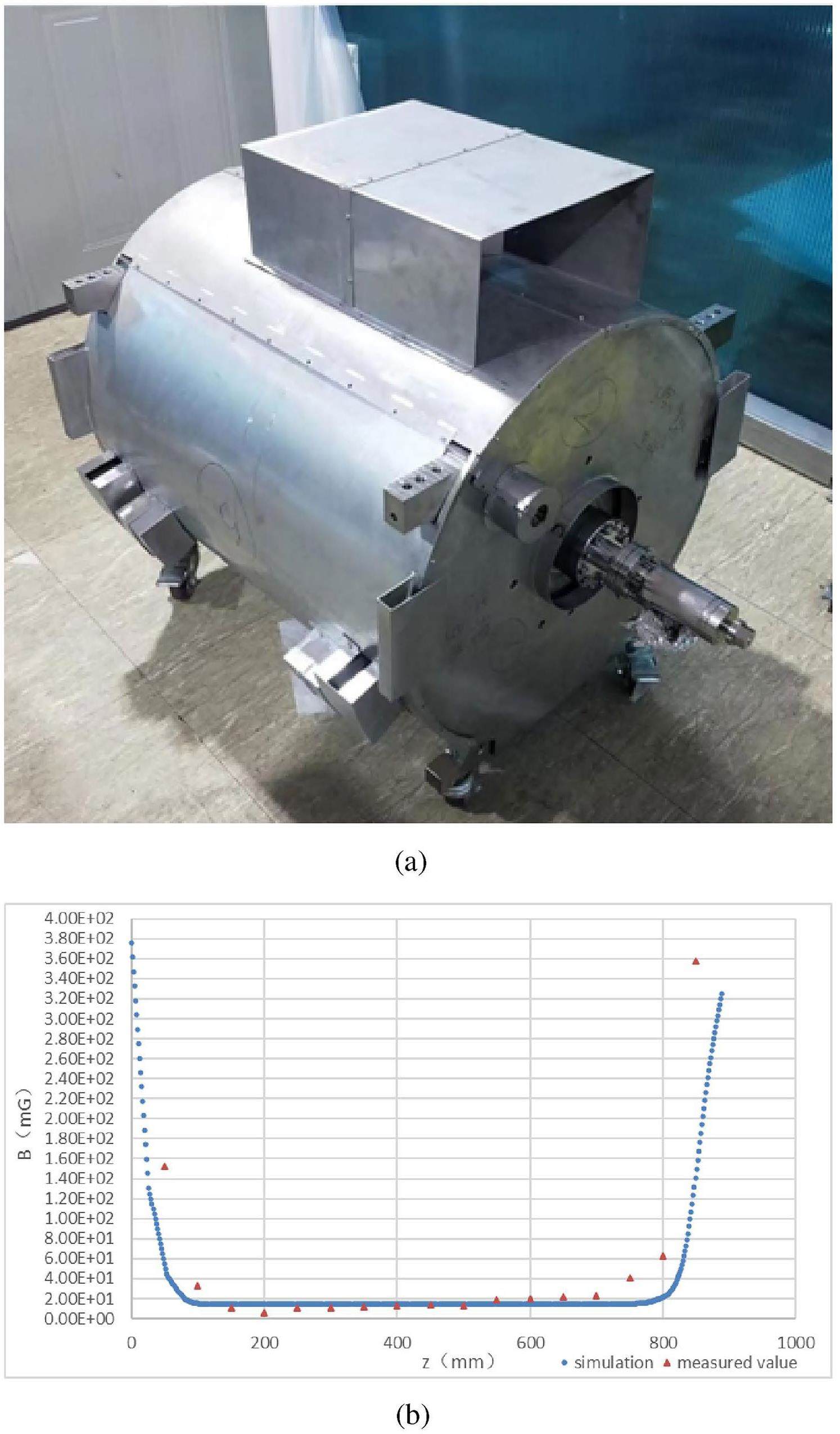

Installation of the Magnetic Shield

A magnetic shield is used to reduce the impact of the Earth’s magnetic field around the superconducting cavity. If the external magnetic field surrounding the cavity is extremely strong, the defective parts of the cavity will trap the magnetic field in the cavity wall when the cavity undergoes a superconducting transition at 9.2 K [47-49]. During operation, the surface resistance of the cavity causes heating or quenching. According to the previous design, to ensure that the residual magnetic field at the axial center of the cavity is less than 20 mG, the mechanical clearance of the magnetic shield should be minimized during installation.

After the completion of the magnetic shield production, a room-temperature test was conducted [50]. The magnetic shield was initially assembled without a cavity to maintain its hollow state for more precise measurements, and was aligned with the CSNS linac orientation. To ensure that external interference did not affect the results, we utilized a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) rod to support the test probe along the axis and performed measurements at 18 points spaced 50 mm apart from one end to another. A BELL 5180 Gaussian meter was used to conduct the measurements, and the measured values matched the simulated values, as shown in Fig. 26 [3].

After production of the magnetic shield, owing to local improvements in installation within the cryostat and the influence of cryogenic tooling, the magnetic shield must be partially modified during installation. A magnetic shield is installed after wrapping the cavities with multilayer insulation. Figure 27 shows the magnetic shield after installation.

Installation of the Cavity String and Thermal Shield

When the ancillary equipment for the cavity string is installed, it must be transferred to the cryogenic mass vehicle. Initially, a lower thermal shield [51] is placed on the cold-mass vehicle, as shown in Fig. 28.

Subsequently, the entire cavity string frame is placed within the lower thermal shield on the track. The low-temperature piping on the cavity string must be secured with G10 [52] rods, the cables must be organized, and the coupler thermal anchor must be connected to the lower thermal shield using copper-braided straps. When installing the copper-braided straps, indium sheets coated with thermally conductive grease are used on both sides to fill the gap between the two copper plates. Additional check washers are installed to prevent screw loosening and thermal conduction problems during cooling.

The third step involves connecting the upper thermal shield to the lower thermal shield and sealing the respective low-temperature piping. In the design, the piping of both components is tightly connected using vacuum coupling radius seal (VCR) connecters. After installation, a room-temperature vacuum leak test and liquid-nitrogen low-temperature leak test should be performed. During actual installation, we found that the sealing surface of the VCR is prone to damage, resulting in a higher probability of vacuum leaks at low temperatures. Consequently, the solution using the VCR connecter was discarded in favor of welding for the connection of low-temperature pipelines in the mass production of the cryostats in the future.

The entire thermal shield is completely wrapped in 30 layers of multilayer insulation [53], after which the entire cold mass is pushed into the cryostat along the track (Fig. 28).

Inside the cryostat, the cables of various sensors should be welded to the cryostat feedthrough and the thermal anchors of the bellows assemblies connected at both ends of the cavity string to the thermal shield using copper braided straps, following the same installation method described earlier. Next, the extended seven-channel pipes must be welded, and the internal pipe system of the cryostat must undergo vacuum testing. Finally, the large end cap of the cryostat should be covered, and the entire cryostat must undergo vacuum leak testing (Fig. 29).

Connection of the Cryostat and Valve Box

After the cryostat is installed, it must be connected to the valve box. In the design, the cryostat is placed on a horizontal test room flat track car and moved into the horizontal test room to connect to the valve box through a seven-channel low-temperature pipeline. Subsequently, vacuum testing is performed, cables are laid, and the room-temperature portion of the coupler are installed. When the cryostat and valve box are properly installed (Fig. 30), the gate valves at the cavity ends can be opened, and a vacuum can be drawn using ion pumps, achieving a static vacuum level in the cavity of the order of 10-7 Pa.

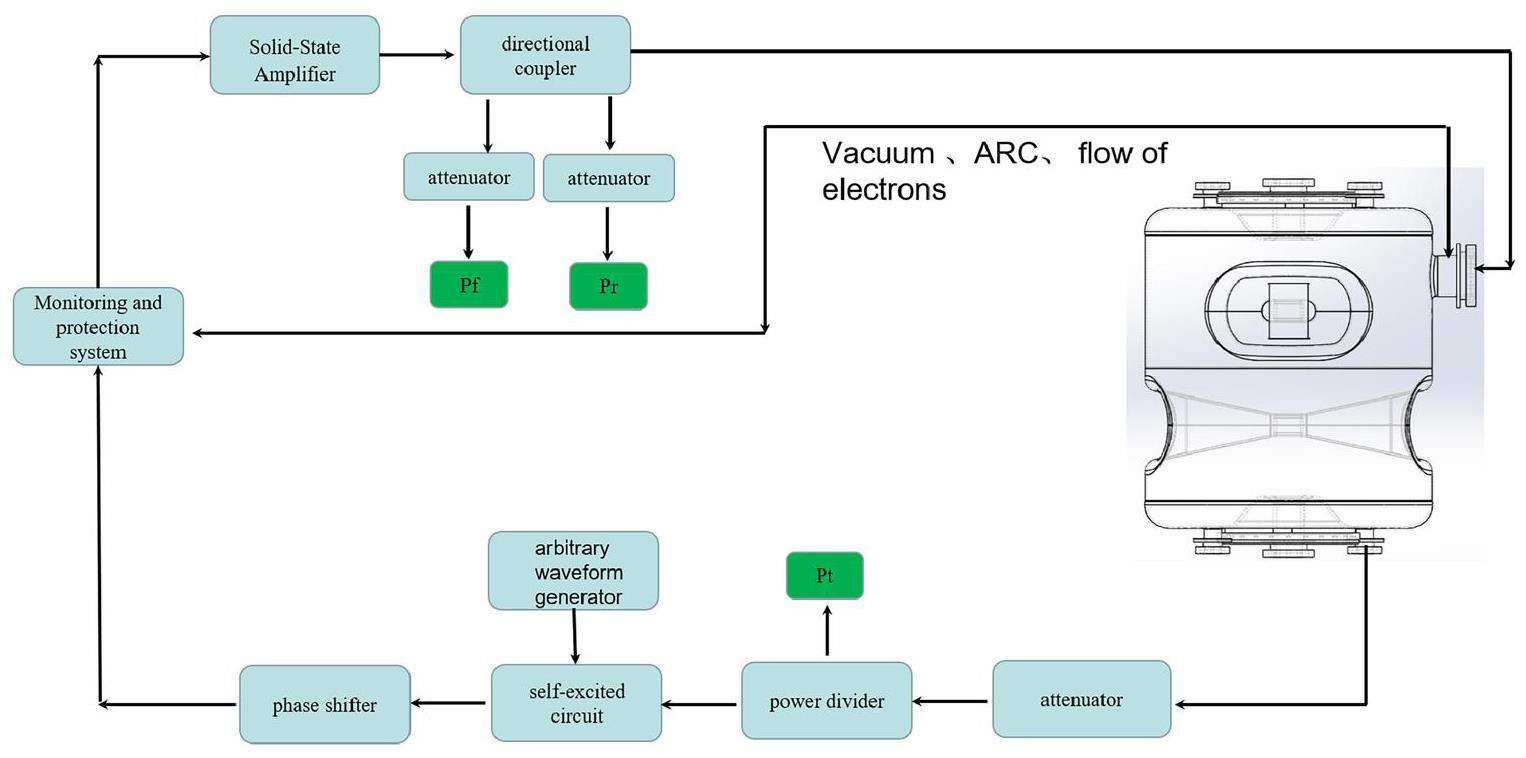

Installation of the Horizontal Test Power Source

The horizontal test of the double-spoke cavity cryomodule is driven by a 50 kW solid-state amplifier, which transmits the RF power to two couplers through waveguide and coaxial feeder. A three-stub tuner is added to the power transmission line to increase the power fed into the superconducting cavity, increasing the power at the coupler. The maximum output power of this power source in the CW mode is 50 kW, and that in the pulse mode with a repetition frequency of 25 Hz is 90 kW (Fig. 31).

Coupler Room-Temperature Conditioning

Although the coupler underwent high-power conditioning before installation, including 400 kW traveling and standing wave conditioning, exposure to the atmosphere after conditioning may result in gas release when the coupler is powered at low temperatures. The released gas may be adsorbed in the cavity wall owing to a "cold pump" effect, resulting in arcing in the cavity or a decrease of the Q factor, and even causing quenching [54-56]. Therefore, high-power conditioning should be performed on the coupler again before cooling [57, 58].

Based on the previous high-power conditioning performance, the coupler exhibits multiplication and requires a long conditioning time. Multiple sensors were installed on the coupler to complete the conditioning process successfully: eight temperature sensors, one arcing detector, one electron current detector, and one vacuum gauge. The eight temperature sensors were placed at the flange, ceramic, coaxial root, and rectangular cylinder on the atmospheric side of the coupler. The arc detector, electron current detector, and vacuum gauge were located on the vacuum side of the ceramic (Fig. 32).

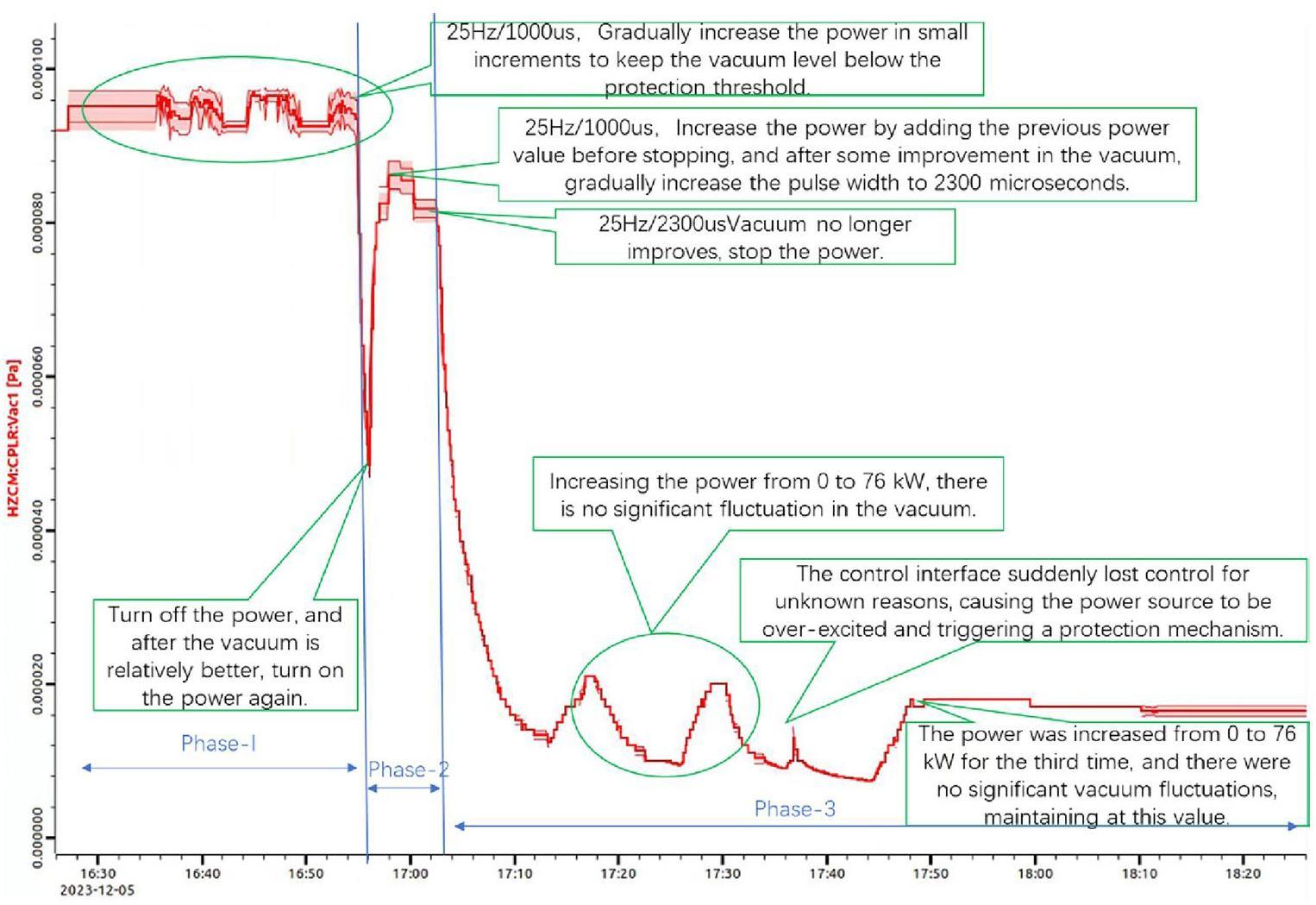

Eleven signals are all connected to the interlocking protection system. When the electron current detector, arc detector, or vacuum gauge triggers protection, the power source is immediately cut off. The initial protection threshold of the vacuum gauge was set as follows: upper limit 4.5×10-5 Pa, and lower limit 4.5×10-5 Pa. The initial vacuum level in the beam tube of the cavity is 1×10-6 Pa, and the readings of the vacuum gauges for both couplers are 1.5×10-5 Pa.

When the high-power conditioning of the coupler starts with a low pulse width and repetition rate, the power is gradually increased to the maximum, and then the duty cycle is gradually increased. The steps for the pulse width are 30, 50, 100, 200, 400, 1000 μs, 2000, and 2300 μs, and the steps for the repetition frequency are 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 25 Hz.

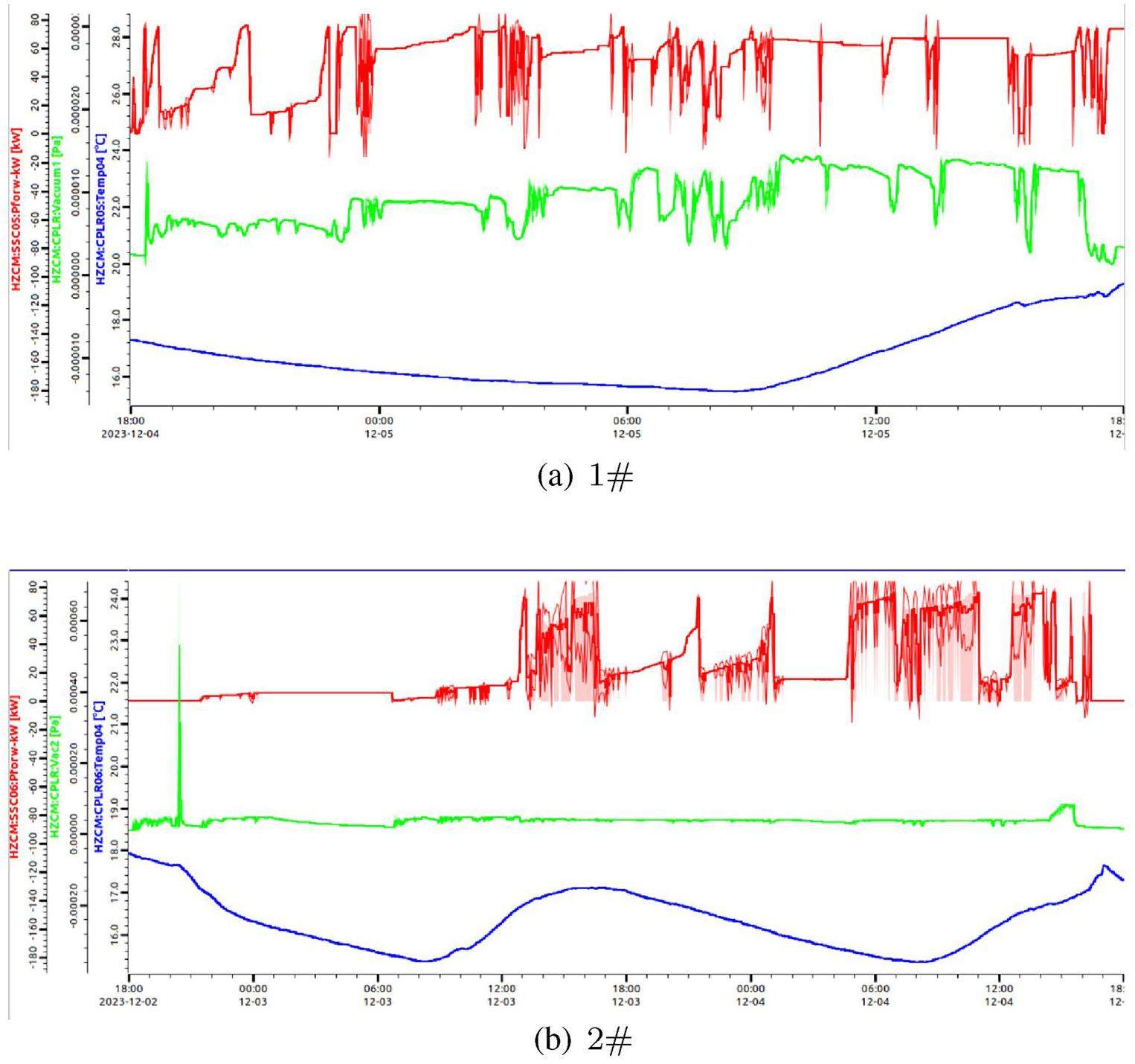

Because only one coaxial feed line is available for the coupler conditioning, the two couplers can only be conditioned in rotation. The conditioning of the #1 coupler required 48 h to complete the 76 kW power conditioning, and the #2 coupler required 24 h. The conditioning statuses of the two couplers are shown in Fig. 33a and 33b. The temperature fluctuated between 14.7-15.6 °C during the conditioning period.

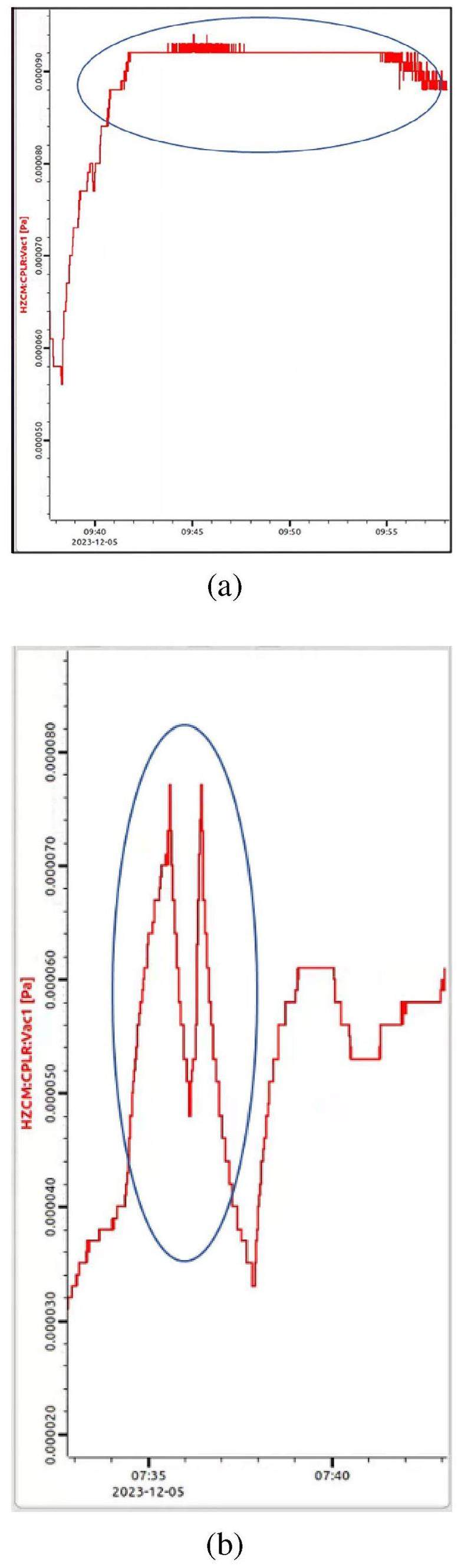

Fig. 34a shows that as the power increases to 66.5 kW, the vacuum level deteriorates, but stabilizes to a certain extent and gradually improves with the conditioning time. Fig. 34b shows that the rapid venting of the coupler causes a rapid deterioration in the vacuum level when the power reaches 57.9 kW, resulting in interlocking protection after reaching the threshold. If the same phenomenon occurs repeatedly, the duty cycle (pulse width or repetition rate) should be reduced appropriately and then gradually increased after conditioning at a lower duty cycle. The second phenomenon should be avoided as much as possible to improve the conditioning effect.

In addition to these two situations, a typical scenario occurs in which high-power venting is caused by MP, as shown in Fig. 35.

In this conditioning process, an MP induces a high-power exhaust. Two conditions are required for the occurrence of MP: 1. suitable field; 2. surface secondary electron emission coefficient.

First stage: In the MP-excited coupler exhaust state, although the vacuum exhibits an improving trend, no significant change occurs.

Second stage: After conditioning in the first stage, when the power is turned off and the field is changed, the secondary electron emission coefficient decreases. Residual gas is still present; therefore, when the power is turned on, the generated MP causes high-power exhaust, resulting in a slightly better vacuum level but no essential change.

Third stage: The vacuum level further improves, the residual gas is very low, and the secondary electron coefficient is further reduced, maintaining a relatively good vacuum level.

The MP power points for coupler 1# are 66-70 kW, and for coupler 2#, they are 13-20 kW and 30-40 kW. The power is gradually scanned from low to high, and when no significant change in the vacuum level is observed, the coupler is considered to be properly conditioned. Subsequently, a cooling operation is performed.

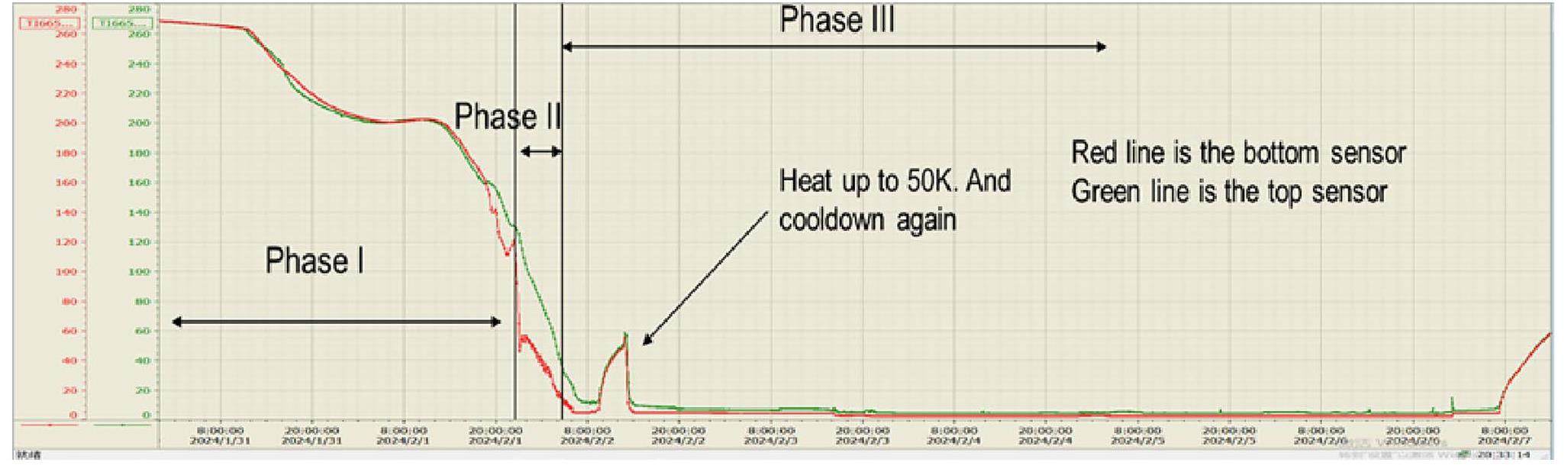

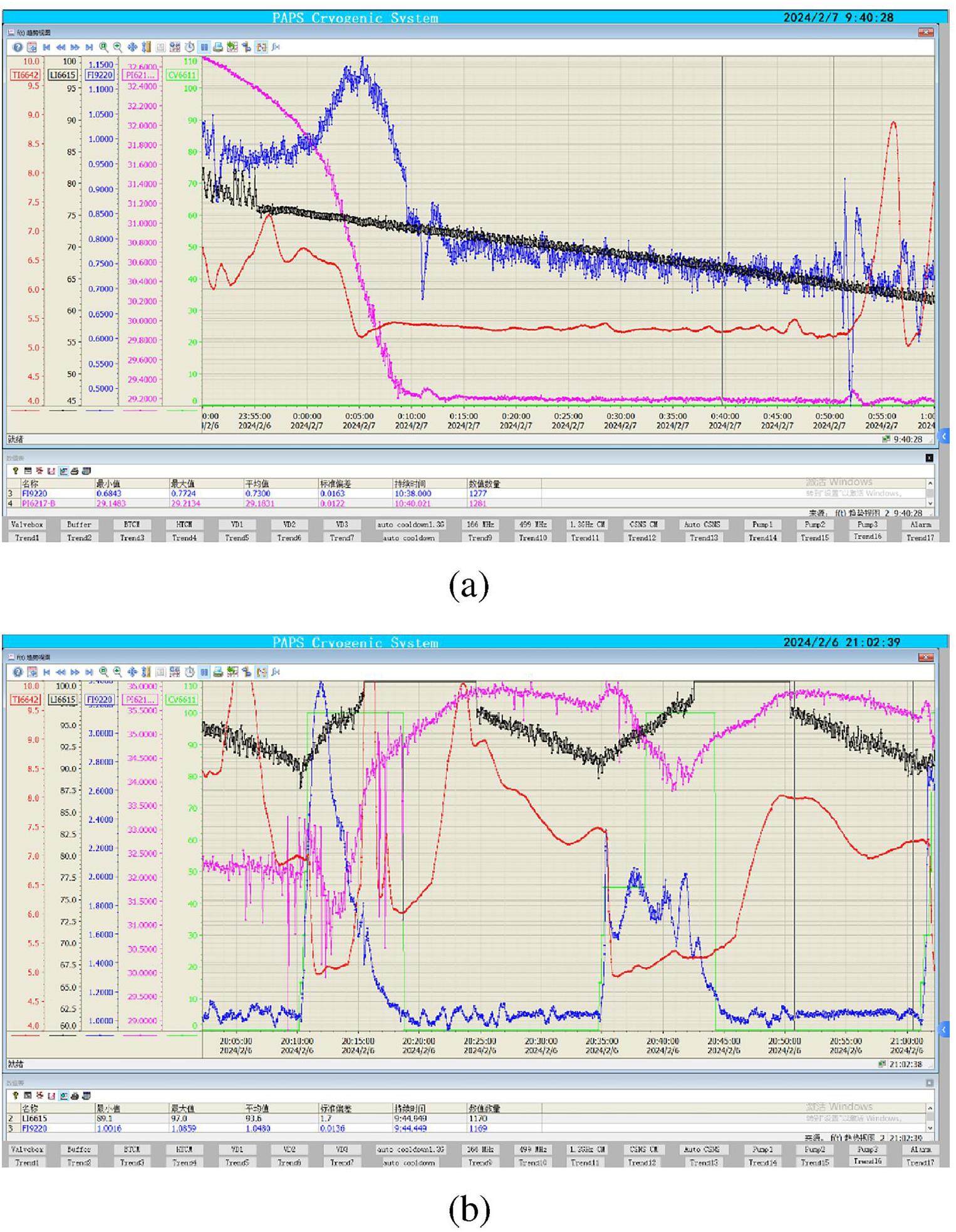

Cooling

Cooling was performed when the insulating vacuum in the cryostat exceeded 5×10-1 Pa. The cooling rate has a significant effect on the quality factor of the cavity [59, 60]. The entire cooling process was divided into three stages. Based on the results of the vertical test with the jacketed cavity, a slow cooling is required at the 9.2 K transition to reduce the temperature difference between the top and bottom of the double-spoke cavity and to release as much magnetic flux as possible, thereby improving Q0 of the cavity (Fig. 36) [4]. Therefore, after the first cooling to below 9.2 K, a slight reheating to 12 K is required before cooling again to improve the effectiveness of the magnetic flux release.

Stage 1: Cooling of the 40-80 K thermal shield and 3 bar at the 5 K mainline (from 300 to 120 K).

Stage 2: Transition zone cooling of 3 bar at the 5 K mainline (from 120 to 40 K).

Stage 3: Liquid-helium cooling at 3 bar at the 5 K mainline (from 40 K to the liquid-helium temperature region).

The cooling process is depicted in Fig. 37 and lasted for approximately 72 h. During the rewarming process, the control was not ideal, reaching 50 K, but the top-bottom temperature difference near the superconducting transition at 9.2 K was 9 K, which satisfied the cooling requirements.

Horizontal Test

Principle of testing

A self-excitation method was used during the horizontal test [61]. In the self-excited mode, when the power source is in CW mode and has a low acceleration gradient, τ1/2 is measured using the amplitude of the cavity field at the falling edge after cutting off the power. QL can be calculated using Eq. 2.

According to Eq. 3 [62]

Calibration

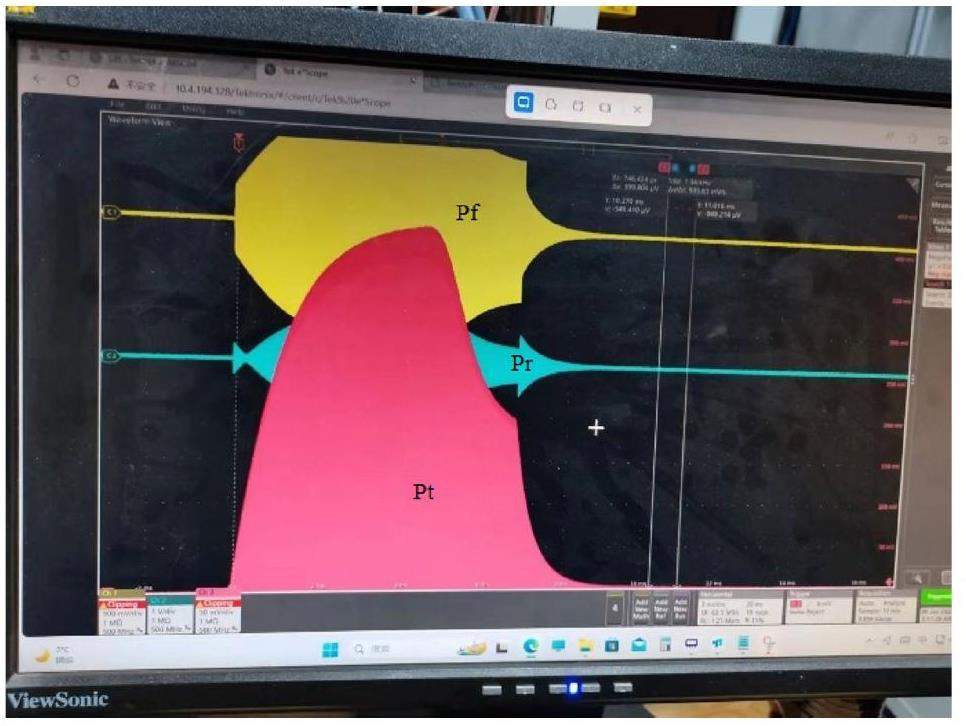

Before the test, the instruments, directional couplers, and cables should be calibrated. The instruments used for the horizontal test include an R&S network analyzer, Keysight E4417A power meter, Tektronix MSO64 oscilloscope, and Pfeiffer vacuum gauge.

Instrument calibration: First, all power meters are restored to their factory settings, and the probes are calibrated using a calibration source. Subsequently, the offset is set to 0.

Signal source calibration: The output of the signal source and power meter probe are connected using a one-meter-long coaxial cable. The output power of the signal source is set to P0=12 dBm, and the power meter reading is observed. The observed value is denoted as the calibrated power

Calibration of Pf and Pr cables: One end of the Pf and Pr cables is connected to the output cable of the signal source and the other end to the power meter. The output power of the signal source is set to P0=12 dBm, and the power meter (in dBm) readings Pin-line and Pr-line. The difference

Calibration of the Pt cable: One end of the Pt cable is connected to the output cable of the signal source and the other end to the power meter. The output power of the signal source is set to P0=12 dBm, and the power meter reading Pt-line is recorded. Next, the network analyzer is connected to the crymodule Pt port and S11 is read. Subsequently, the calibration factor Ct is calculated using Eq. 11.

| Cin (dB) | Cr (dB) | Ct (dB) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAV1# | 66.25 | 66.08 | 18.86 |

| CAV2# | 65.94 | 65.95 | 18.96 |

Owing to the high Q value and narrow bandwidth of the cavity at 2 K, it must be calibrated using a self-excited system. A schematic representation of this process is shown in Fig. 38.

During calibration, to avoid the impact of excessive power on the coupler’s antenna causing thermal effects and changes in Qe, the power is maintained below 1 kW. Calibration is performed three times, and the average is calculated. The calibration values for τ1/2 and QL are presented in Table 6.

| CAV1# | CAV2# | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (MHz) | 323.9960 | 323.9516 |

| First τ1/2 (ms) | 0.1638 | 0.1323 |

| First -6 dB time (ms) | 0.32 | 0.2608 |

| First QL | 481000 | 389000 |

| Second τ1/2 (ms) | 0.1638 | 0.133 |

| Second 6 dB time (ms) | 0.32 | 0.260 |

| Second QL | 481000 | 391000 |

| Third τ1/2 (ms) | 0.1638 | 0.132 |

| Third 6 dB time (ms) | 0.32 | 0.260 |

| T|hird QL | 481000 | 388000 |

| average QL | 481000 | 388000 |

| QL Standard deviation | 0 | 1510 |

| QL relative error | 0% | 0.39% |

Table 6 shows that the QL for cavity 1# is close to the set value of 5× 105, whereas QL for cavity 2# deviates significantly from the design value. Upon reviewing the alignment test data, we observed that the flange of the fundamental power coupler of cavity 2# is 5 mm lower than the design value, causing the antenna to penetrate too deeply into the cavity, resulting in a decrease in Qe.

The calibration results for Qt are presented in Table 7.

| CAV1# | CAV2# | |

|---|---|---|

| First Pf (w) | 198 | 603 |

| First Pr (w) | 170 | 556 |

| First Pt (mw) | 0.43 | 1.4 |

| First Qt | 8.82×1011 | 6.69×1011 |

| Second Pf (w) | 302 | 499 |

| Second Pt (mw) | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Second Qt | 8.63×1011 | 6.78×1011 |

| Third Pf (w) | 427 | 816 |

| Third Pt (mw) | 1 | 1.9 |

| Third Qt | 8.51×1011 | 6.66×1011 |

| Qt average | 8.66×1011 | 6.71×1011 |

| Qt standard deviation | 1.54×1010 | 6.17×109 |

| Qt relative error | 1.51% | 0.9% |

Accelerated Gradient Testing

After calibration, the power can be increased and the gradient can be tested. Because the superconducting cavity and main coupler operate in the pulsed mode, both the power source and power meter must be set to the pulsed operation mode. Owing to the limitations of the power source, the maximum test gradient can only reach the values listed in Table 8.

| Pf (W) | Eacc with Pf (MV/m) | Pt (W) | Eacc with Pt (MV/m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAV1 | 81067 | 11.5 | 218 | 12.7 |

| CAV2 | 76405 | 10.1 | 177 | 10.1 |

Because the maximum gradients for the two cavities in the vertical tests are 11.6 and 15 MV/m, respectively, to verify whether the gradients decrease during the horizontal tests, the power of the power source must be increased. To address this problem, we adopted the method of using a three-stub tuner to increase the power at the cavity coupler port. A WPS-R382 high-frequency phase shifter (Fig. 39), which operates based on the same principles as a three-stub tuner. It can be used as a phase shifter in a traveling wave network, and as a tuner for adjustments in a standing-wave network.

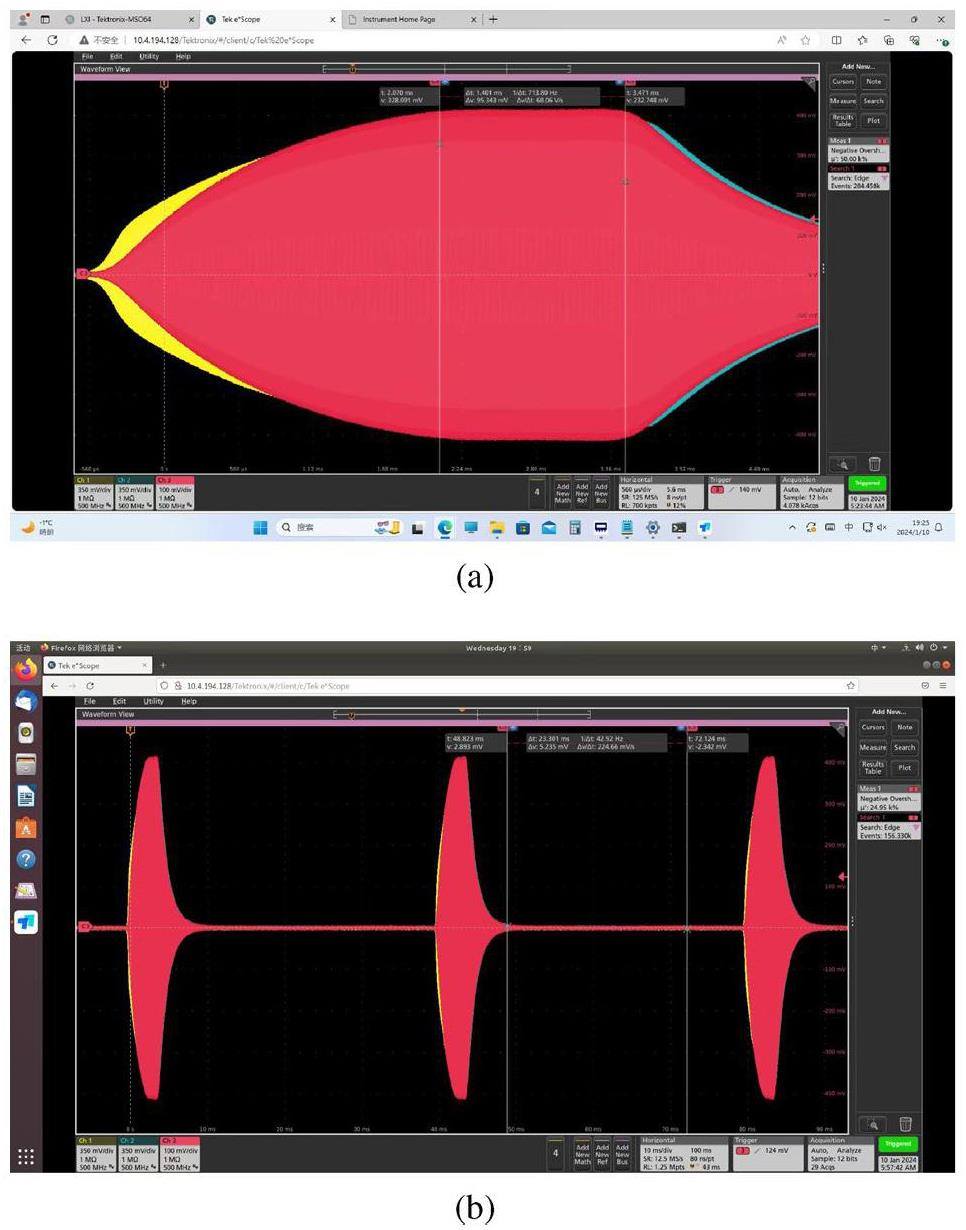

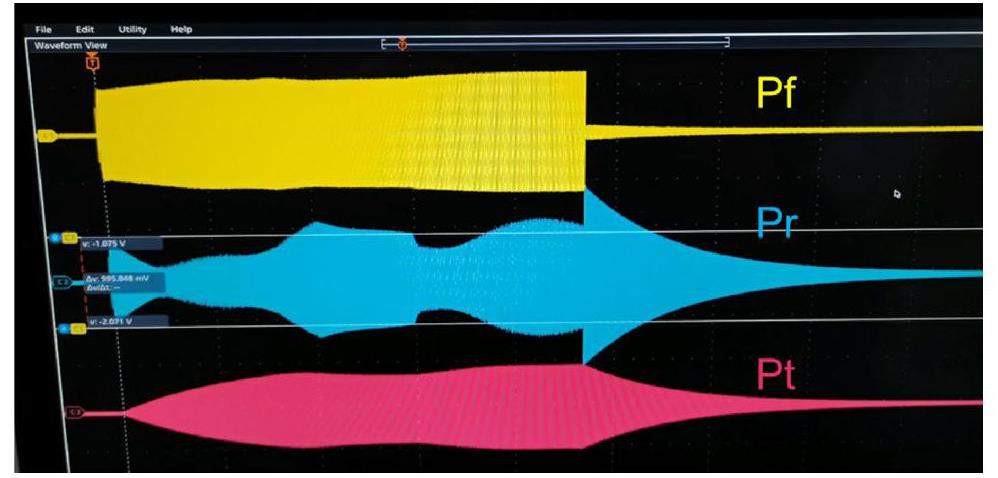

The three studs must be adjusted at a low power to prevent arcing. This operation is performed at a power of 1 kW. When the coaxial line is connected to the 1# cavity, the Pt signal of the cavity reaches its maximum when the depths of the 1# and 3# studs in the tuner are 115 mm and the depth of the 2# stud is 15 mm. The studs are then fixed, and the power at the coupler port is increased. After calculation, the maximum gradient reaches 12.8 MV/m. However, as the power is further increased, the superconducting cavity exhibits quenching. In Fig. 40, the red wave indicates the Pt signal, and the graph indicates that the cavity field waveform lacks a portion compared with the normal waveform. With a further increase in power, the superconducting cavity quenches completely.

When the coaxial line is connected to the 2# cavity, the 1# and 3# studs of the three-stub tuner need to be inserted into the tuner by 15 mm, whereas the 2# stud must be inserted using 120 mm to maximize Pt. The maximum gradient reaches 15.2 MV/m, and the dose is 42 μSv/h. However, the addition of a tuner significantly increases the equivalent Qe of the coupler, resulting in an excessively long build-up time, which fails to satisfy the requirements for a 25 Hz repetition rate. This problem can be solved by creating a waveform using an arbitrary waveform generator, enabling the cavity field to have a 1.4 ms flat top at a 25 Hz repetition frequency, as shown in Fig. 41.

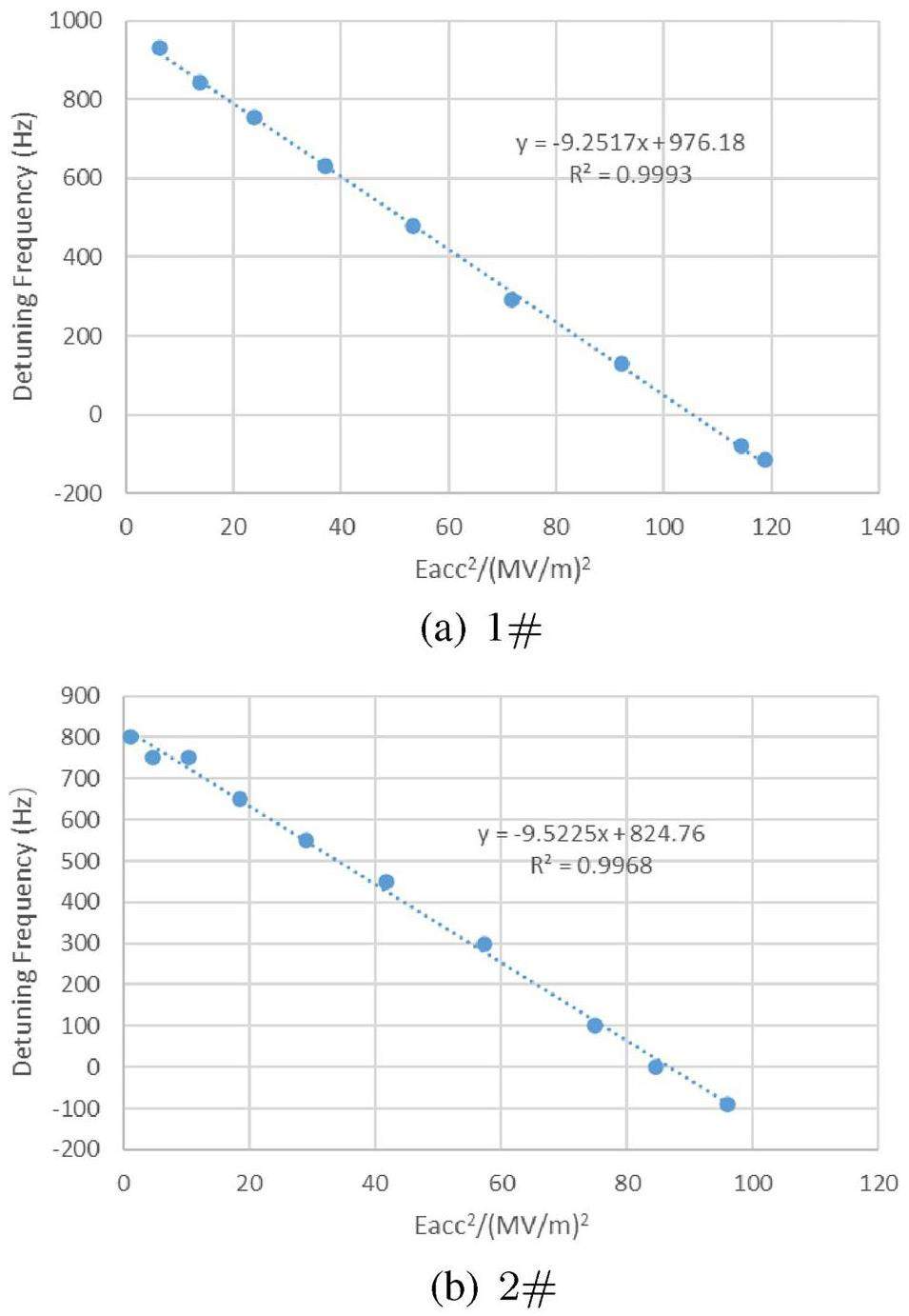

Lorentz Force Coefficient Test

The frequency of the superconducting cavity tends to decrease as the gradient increases. The detuning frequency has a linear relationship with the square of the accelerating gradient. By changing the accelerating gradient while maintaining helium pressure stability, the frequency variations were measured to fit the Lorentz force coefficient [63]. The Lorentz force detuning coefficients for the two cavities were determined to be -9.25 and -9.52 Hz/(MV/m)2, respectively (Fig. 42). The fitted values were superior to the theoretical calculations, -10.5 Hz/(MV/m)2.

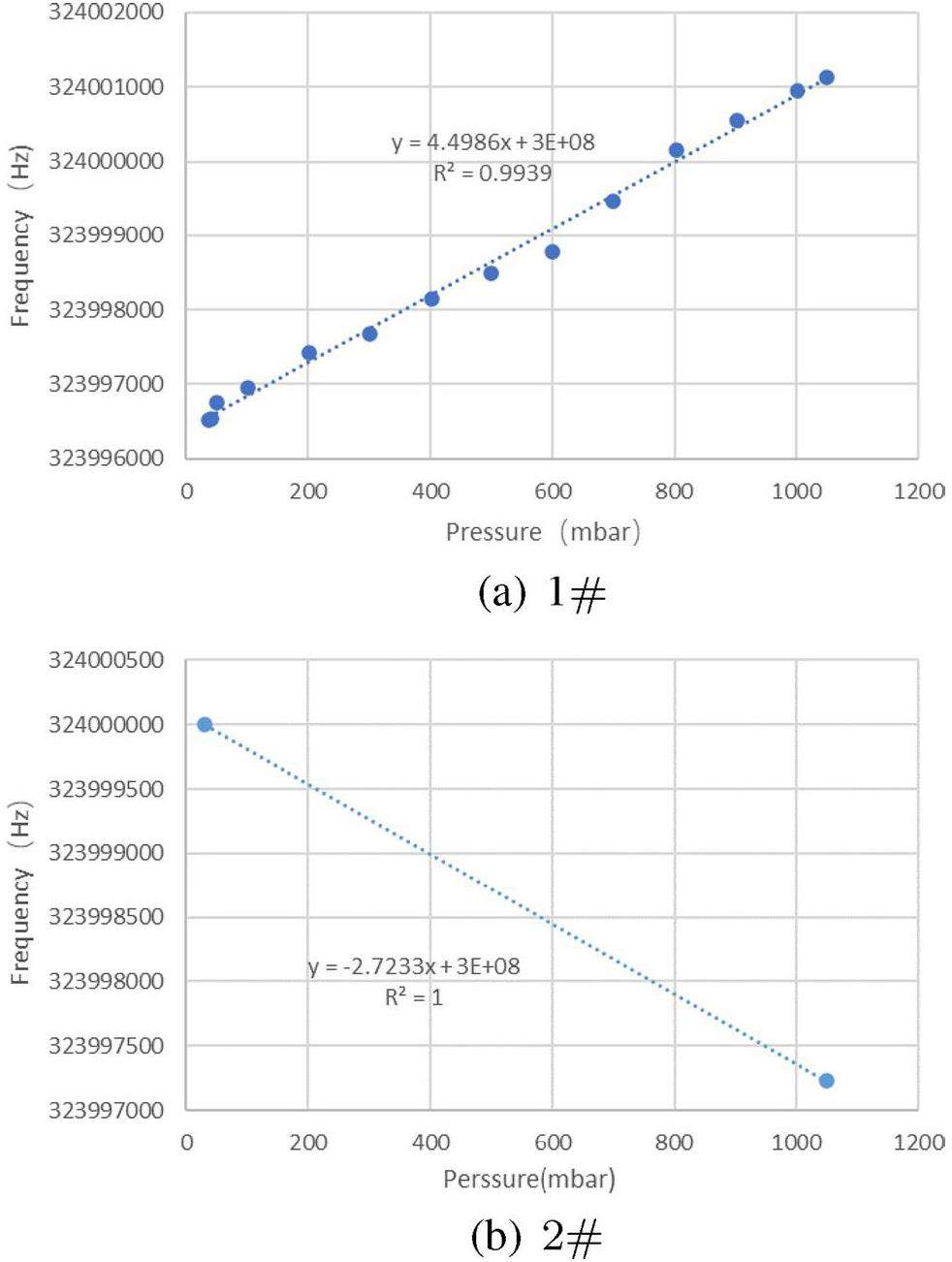

Helium Pressure Sensitivity Test

The cavity frequency changes were measured as the helium pressure increased from 31 to 1050 mbar. The fitted helium pressure sensitivities (df/dp) were determined to be 4.5 and -2.7 Hz/mbar, respectively (Fig. 43). However, it has a slight discrepancy with the theoretically calculated sensitivity of 3 Hz/mbar, which may be because the actual and theoretical boundary conditions are not completely identical, such as differences in the stiffness of the tuner or the pre-tension force of the tuner.

Dynamic Lorentz Force Detuning Study

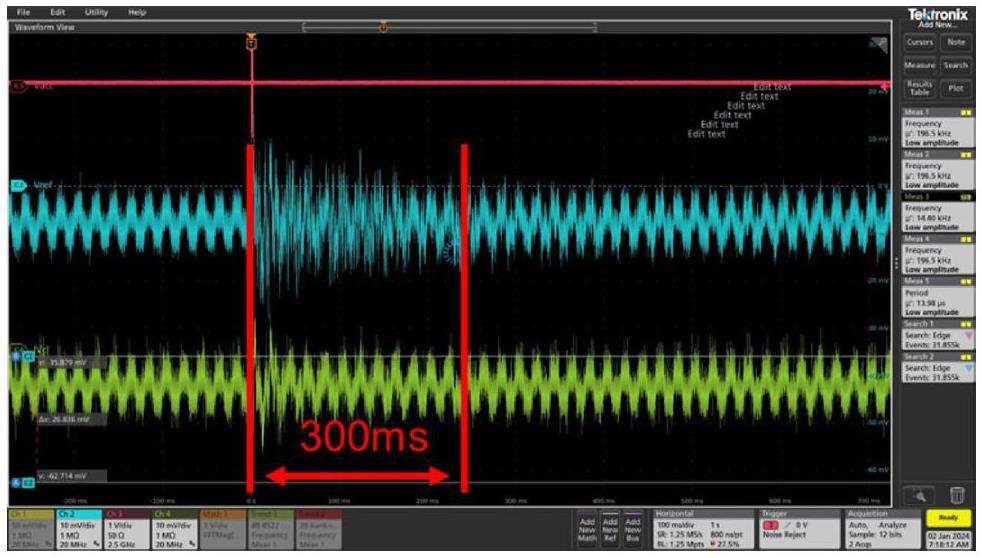

The key difference between the operation of a pulsed superconducting cavity and a CW superconducting cavity is that the pulsed cavity must consider dynamic Lorentz force detuning [39, 61, 64, 65], which can cause the superconducting cavity to operate unstably. The testing method involves applying a pulsed power to the cavity under test, changing the repetition frequency or pulse width, observing the variation in the two piezo measurement signals from the cavity (Fig. 44), and observing changes in the cavity field from Pt.

Figure 44 shows that after a pulse power is emitted, an oscillation of approximately 300 ms occurs. If the repetition frequency is less than 3 Hz, the oscillation naturally decays during the pulse period, and the cavity field does not sustain prolonged oscillations. However, if the repetition frequency exceeds 3 Hz, a certain probability of oscillation exists. Sustained oscillations in the cavity field are directly related to the pulse width and phase. Experimental evidence has shown that, for the 1# cavity, at a pulse repetition frequency of 47.5 Hz, a pulse width greater than 1.8 ms and a gradient greater than 8.6 MV/m, intense vibration occurs. For the 2# cavity, at pulse repetition frequencies of 38 and 40 Hz and a pulse width greater than 1.8 ms, intense vibration occurs at gradients greater than 8.6 MV/m, as shown in Fig. 45.

In the experiment, we observed that when oscillations occur, changing the repetition frequency, reducing the pulse width, or increasing the tension force of the tuner can contribute to the cavity exiting the oscillation state.

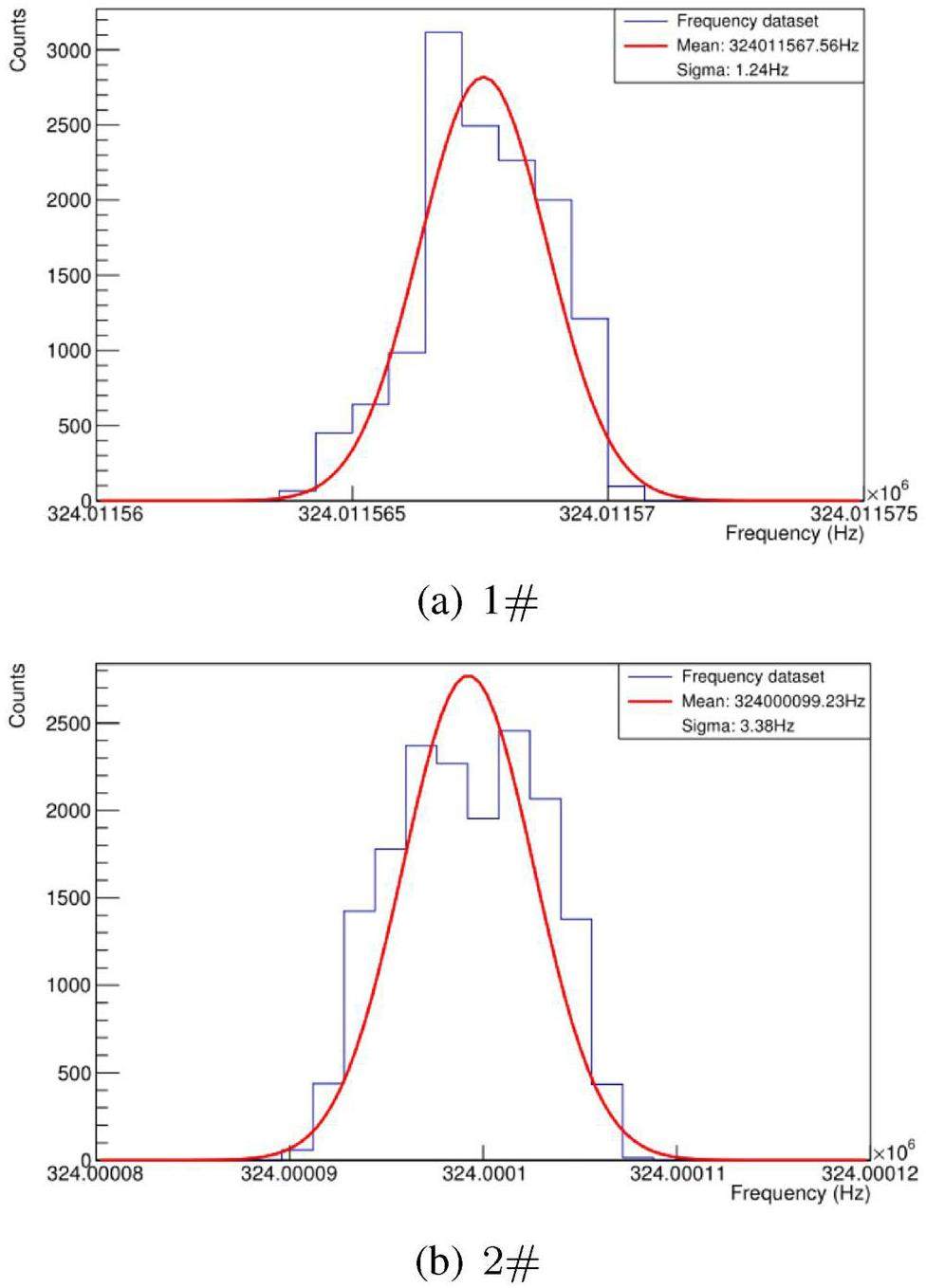

Microphone effect

External disturbances are among the most important factors affecting the normal operation of superconducting cavities. When the frequency of the external disturbance coincides with the natural mechanical frequency of the superconducting cavity, cavity vibrations can be amplified and unstable frequency oscillations can occur [66]. In the testing method, a high-frequency power is applied to the cavity, and the frequency offset is observed under working conditions using a spectrum analyzer [67]. This enables observation of the magnitude of interference from the external environment on the superconducting cavity (such as unstable helium pressure and external vibrations). Fig. 46 shows that the frequency variation within one sigma for both cavities is only 1-3 Hz.

Heat load test

An important performance indicator of a cryomodule is the measurement of static and dynamic heat loads. Static heat leakage refers to the thermal load of a cryomodule when it is not in operation, including the heat transmitted to the cryogenic system by the external environment through the cryomodule’s thermal insulation vacuum, thermal shield, and other equipment via radiation and heat conduction. Dynamic heat leakage refers to the thermal load of the cryomodule during operation [68], including the power loss of the superconducting cavity and the heat generated by high-power couplers.

The flow method is used to test the thermal load. After the entire cryomodule is cooled and the return gas flow stabilizes, the liquid injection valve is closed, and the average flow rate for 10 min is taken as the static flow rate fstatic. The total heat loss is then calculated based on the helium gas flow rate calibrated for the 1.3 GHz nine-cell superconducting cavity module at 1 g/s, which is equivalent to 23 W [69]. After testing, the flow rate of the double-spoke superconducting cavity cryomodule is 0.73 g, and the total static loss is calculated as 0.73×23=16.79 W (Fig. 47a).

When the dynamic heat leakage was measured, the superconducting cavity is powered to the rated gradient. After the flow rate stabilized, the average flow rate over 10 min was measured and recorded as the total flow rate ftotal. The dynamic flow rate fdynamic was calculated as ftotal - fstatic, and the dynamic heat load was calculated using the formula fdynamic× 23. Following this measurement, ftotal measured at 1.048 g/s (Fig. 47b), the dynamic heat load was calculated as (1.048-0.73)×23=7.73 W. However, the calculated value deviated significantly from the theoretical value. After the analysis, the main suspected cause was excessive heat leakage, perhaps from the coupler or the impact of the entire cryogenic mass not yet reaching the desired low temperature. Subsequently, when the coupler was dismantled, sparking was observed inside the coupler. This resulted in a strong suspicion that the excessive heat load from the coupler was caused by sparking. Plans were made to disassemble the cavity from the cryomodule for structural optimization.

Summary

The prototype double-spoke superconducting cavity cryomodule is the first of its kind in China, with a maximum horizontal test acceleration gradient of 15.2 MV/m, significantly surpassing the requirements of beam dynamics physics design. This paper elaborates on the installation process of the entire cryomodule, highlighting the problems encountered and the corresponding solutions. The main focus of cryomodule installation is to control the installation process and techniques. This installation serves as a preliminary research for the prototype of the cryomodule, providing a reference for future mass production. Subsequent optimizations of the installation process and components will be based on this foundation. Subsequently, dynamic heat leakage measurements will be conducted after the cryomodule is reinstalled. Testing has laid a solid foundation for the smooth construction of CSNS-II. Currently, CSNS-II has begun construction, and plans for mass production are being planned.

The design and construction of CSNS drift tube linac

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 911, 131-137 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.10.034An overview of design for CSNS/rcs and beam transport

. Science China Physics, Mechanics and Astronomy 54, 239-244 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-011-4564-xDevelopment of a large nanocrystalline soft magnetic alloy core with high μp Qf products for CSNS-II

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 99 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01087-xDevelopment of the double spoke cavity prototype for CSNS-II

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1062,Design, development and commissioning for high-intensity proton accelerator of china spallation neutron source

. Atom. Energy+ Sci. Technology 56, 1747-1759 (2022). http://www.aest.org.cn/CN/1000-6931/home.shtmlEss technology development at ipno and cea paris-saclay

.Production, test and installation of ess spoke, medium and high beta cryomodules

.PIII Project Overview and Status

,Design of the china spallation neutron source phase ii double spoke resonator

. High Power Laser and Particale Beams 35,High-Velocity Spoke Cavities

.RF design optimization for the SHINE 3.9 GHz cavity

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 73 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00772-zDevelopment of a superconducting radio frequency double spoke cavity for CSNS

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 988,Superconducting spoke cavities for high-velocity applications

. Phys. Rev. Spec. Top-Ac 16,Field emission from crystalline niobium

. Phys. Rev. Special Topics—Accelerators and Beams 12,Multipacting studies in elliptic SRF cavities

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 867, 128-138 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.06.003Suppression of multipactoring in superconducting cavities

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 24, 1101-1103 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.1977.4328862Systematical study on superconducting radio frequency elliptic cavity shapes applicable to future high energy accelerators and energy recovery linacs

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 19,Design optimization of a mechanically improved 499.8-MHz single-cell superconducting cavity for heps

. IEEE T. Appl. Supercon. 31, 1-9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2020.3045746Design study on medium beta superconducting half-wave resonator at IMP

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 1-7 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0081-yReview of ingot niobium as a material for superconducting radiofrequency accelerating cavities

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 774, 133-150 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.11.083Study and design of RF coupler for Chinese ADS HWR superconducting cavity

. Chinese Phys. C. 38,Manufacturing studies and rf test results of the 1.3 GHz fundamental power coupler prototypes

. Phys.Rev.Accel.Beams 25,Room-temperature test system for 162.5 MHz high-power couplers

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0531-9Commissioning and operation of the cryostat for 3W1 SC wiggler

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 96 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01232-0Design and research of cryostat for 3w1 superconducting wiggler magnet

. IEEE T. Appl. Supercon. 28, 1-6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2018.12372790380.Design, assembly, and Pre-commissioning of Cryostat for 3W1 Superconducting Wiggler Magnet

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 113 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00816-4Design, assembly, and pre-commissioning of cryostat for 3W1 superconducting wiggler magnet

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 113 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00816-4ADS Injector-I 2 K superfluid helium cryogenic system

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 39 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-0742-8High power RF tests on fundamental power couplers for the SNS project

[C]//Spoke cavity development and beam commissioning of 10 Mev spoke-based proton linac

. https://epaper.kek.jp/linac2018/talks/th2a02_talk.pdfStatus of the superconducting cavity development at ihep for the cads linac

, in:Commissioning experiences with the spoke-based CW superconducting proton linac

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 105 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00950-7Development and vertical tests of 650 MHz 2-cell superconducting cavities with higher order mode couplers

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 995,Ultrahigh accelerating gradient and quality factor of CEPC 650 MHz superconducting radio-frequency cavity

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 125 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01109-8RF design of 650-MHz 2-cell cavity for CEPC

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 1-10 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0671-6Analysis of high pressure rinsing characteristics for srf cavities

, in:Design and implementation of an automated high pressure water rinse system for frib srf cavity processing

, in:High power testing of the first ess spoke cavity package

, in:Rf conditioning and testing of fundamental power couplers for sns superconducting cavity production

, in:First high power test of the ESS double spoke cavity, 2017

. https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-SRF2017-THPB035Pressure Differential Gate Valve

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 20, 130-130 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.1973.4327062.Fast frequency tuner for high gradient sc cavities for ilc and xfel

, Ph.D. thesis,Design of 648 MHz superconducting cavity tuner for China Spallation Neutron Source phase II

. High Power Laser Part. Beams 35, 12 (2023). https://doi.org/10.11884/HPLPB202335.230227Comparative thermodynamic analysis of China Spallation Neutron Source second phase (CSNSII) SRF system cooling Scheme

. Appl. Therm. Eng. 230,Application of an Embedded TCP/IP Protocol in a Dewar Performance-Parameter Monitoring System of a Radio Receiver

. Astronomical Techniques and Instruments 8, 108-112 (2011).Magnetic flux expulsion effect of 1.3 GHz superconducting cavity

. High Power Laser Part. Beams 32,How is flux expulsion affected by geometry: experi-mental evidence and model

[C]//In Situ cryomodule demagnetization

. arxiv preprint arxiv:1507.06582, 2015. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1507.06582Magnetic shield for the 1.3 GHz cryomodule at ihep

,The ITER thermal shields for the magnet system: specific design assembly and structural issues

. Fusion Eng. Des. 66–68, 1049-1054 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-3796(03)00271-0The local helium compound transfer lines for the large hadron collider cryogenic system

. Aip Conf. Proc. 823, 1607-1613 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2202586Contamination and conditioning of the prototype double spoke cryomodule for European Spallation Source

. arXiv: Accelerator Physics 2020. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:218487325Development of fundamental power coupler for c-ads superconducting elliptical cavities

. Chinese Phys. C. 41,The Integration and RF Conditioning of the ESS Double-Spoke Prototype Cryomodule at FREIA

.High RF power tests of the first 1.3 GHz fundamental power coupler prototypes for the SHINE project

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-00984-5Room-temperature test system for 162.5 MHz high-power couplers

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0531-9T-maps taken during cool down of an srf cavity: a tool to understand flux trapping

, in:Cornell erl main linac 7-cell cavity performance in horizontal test cryomodule qualifications

, in:Dynamic Lorentz Force Detuning Studies in TESLA Cavities

[J/OL]. 2004. https://cds.cern.ch/record/82278Microphonics detuning in the 500 MHz superconducting cesr cavities

. IEEE 2, 1326-1328 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1109/PAC.2003.1289694.The resonant frequency measurement method for superconducting cavity with Lorentz force detuning

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 993,Lorentz force detuning analysis of the spallation neutron source (sns) accelerating cavities. LA-UR-01-5095, 2001

. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:54492898A study of dynamic lorentz force detuning of 650 MHz βg= 0.9 superconducting radiofrequency cavity

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 750, 69-77 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.03.005Elliptical superconducting rf cavities for frib energy upgrade

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 888, 53-63 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.01.001.Application of superconducting cavity tuner in dark photon Aip Conf Proc search

. Radiat. Detect. Technol. Methods 8, 1390-1396 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-024-00457-wCryogenic system design for HIAF iLinac

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 178 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0700-5High q and high gradient performance of the first medium-temperature baking 1.3 GHz cryomodule

, arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.01175 (2023)The authors declare that they have no competing interests.