Introduction

Exploring the quantum chromodynamic (QCD) phase structure is one of the most important topics in high-energy nuclear physics. Simulations using lattice QCD revealed that the transition from the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) phase to the hadron phase is a crossover at the vanishing baryon chemical potential (μ∼eq 0) [1-4]. However, effective theories based on QCD predict that this is a first-order phase transition at a finite chemical potential [5-10]. Therefore, it is natural to conjecture the existence of a critical QCD point between the crossover and first-order phase transitions [11, 12].

The characteristic features of the critical point are long-range correlation and large fluctuations. After being created in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, the QGP fireball scans the QCD phase diagram during the evolution process and may reach a critical region. Such fluctuating effects may affect the final observations of heavy-ion experiments. It was conjectured that non-monotonic behavior as a function of the collision energy can be regarded as a signature of the critical point [13-15]. The first-phase Beam Energy Scan (BES-I) program at the RHIC was used to scan the QCD phase diagram by tuning the collision energy [16]. Preliminary measurements of the net proton multiplicity fluctuations showed such non-monotonic behavior with an energy range of 7.7 GeV to 200 GeV [17, 18]. However, the statistics of the BES-I program are insufficient to conclude the observation of non-monotonic behavior, and much higher statistics are required in the second phase of BES and FIX target measurements (see, e.g., Refs. [19, 20] for reviews).

Theoretically, the QGP fireball created in relativistic heavy-ion collisions is a complex system, and several factors may affect the final behavior of net proton multiplicity fluctuations. For instance, owing to the rapidly expanding effect, multiplicity fluctuations may deviate from the equilibrium fluctuations. By considering the dynamic effects induced by an expanding QGP fireball, it was found that the magnitude of the fluctuations could be suppressed [21, 22], the sign could be reversed [23], and the maximum of the fluctuations could be moved from the critical point [24]. Therefore, remarkable progress has been made in the development of dynamic models near the QCD critical point. For example, the dynamics of conserved variables (charge, net-baryon) have been developed [25-29] and the non-monotonic behavior of the fluctuations with respect to the increasing rapidity acceptance window has been observed [25, 28, 29]. Please see e.g., Refs. [30-36] for recent reviews.

In particular, the signs of multiplicity fluctuations are important for exploring the phase structure in heavy ion experiments. A comparison of the magnitudes of the signs can be regarded as a more obvious signature of the phase transition [14, 37]. It predicted the nontrivial behavior of the signs of higher-order cumulants or moments of conserved quantities near the QCD critical point [14, 37]. By developing a dynamic model near the QCD critical point, it was found that critical slowing-down effects may flip the signs of higher-order cumulants [23]. Remarkably, the fourth-order cumulants (or kurtosis) of multiplicity fluctuations in these conserved dynamical models are typically negative [26-29]. This is difficult to achieve using only critical slowing-down effects. This is because the corresponding memory effects preserve the sign of static kurtosis above the phase transition curve, which is not always negative [23]. Thus, the sign of kurtosis is not yet fully understood in a comprehensive and complex simulation of conserved dynamic models. This work focuses on studying the impacts of one of the factors in the conserved dynamic simulation, that is, finite size effects, on the sign of kurtosis. In a realistic detection experiment with a finite acceptance range, only part of the system is collected. This corresponds to the finite size of the system, and the kurtosis is obtained within a finite volume in dynamical models. To understand the typically negative kurtosis near the critical point in dynamically conserved models, this work is dedicated to pointing out that the finite size of the detected system may also modify the sign of the kurtosis by considering the finite volume when calculating the multiplicity fluctuations in a static system.

Multiplicity fluctuations within finite size system

Near the phase transition, the thermal variables (this work focuses on the baryon density nB) strongly fluctuate, and the corresponding partition function can be written in the Ginzburg-Landau form [26-29]:

The second-order baryon number susceptibility was proportional to the two-point correlator.

Higher-order susceptibilities are important observables for searching the QCD critical point because they are more sensitive to the correlation length, and their signs are more obvious than the magnitudes considering the complex system in relativistic heavy-ion collisions [13, 37]. The fourth-order susceptibility is given by:

Parameterization and discussion

To evaluate the various orders of cumulants (or susceptibilities) near the QCD critical point, the behavior of the correlation length ξ and coupling constants λ3 and λ4 is considered. Lattice QCD suffers from sign problems at large chemical potentials [12] and the results of effective theories based on QCD depend on the input parameters. However, a system near the QCD critical point is believed to belong to the same universality class as the three-dimensional (3D) Ising model [44-46]. Therefore, the equations of state and coupling constants near the QCD critical point can be mapped using the 3D Ising model.

Specifically, in the conserved dynamic model [26-29], the coupling constants are related to the net-baryon susceptibility in the zero-mode limit:

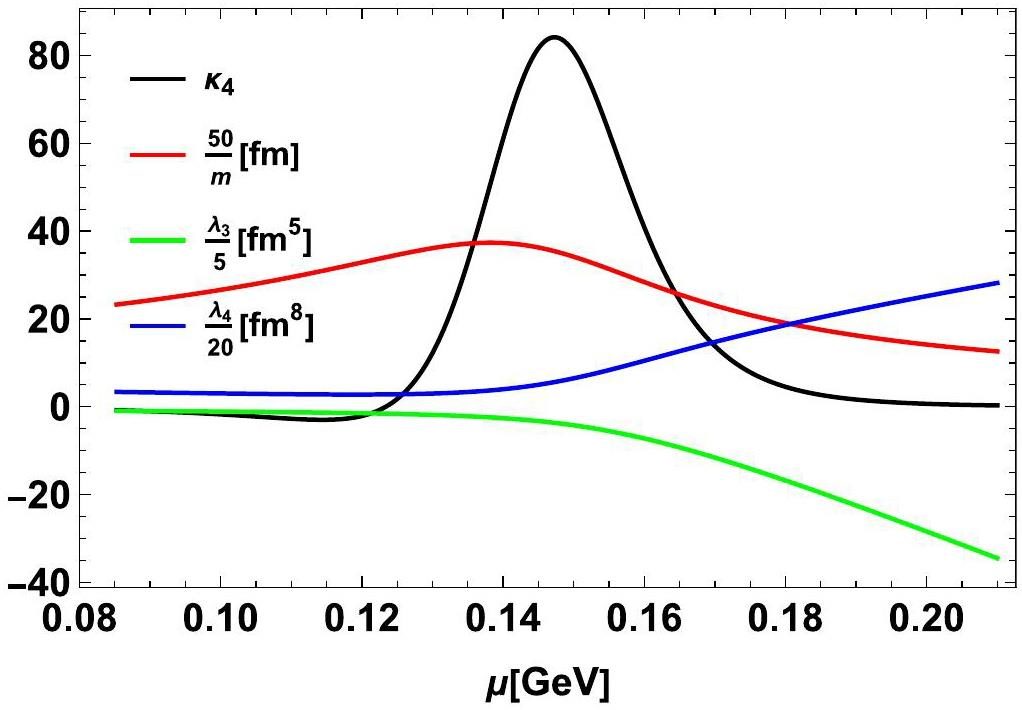

This work is dedicated to understanding the sign of kurtosis in the dynamics of the conserved net-baryon near the QCD critical point. The coupling constants are constructed by mapping from the 3D Ising model, as in Refs. [26-29]. Figure 1 shows the coupling constants with the temperature T=0.138 GeV, below the phase transition curve. The fourth-order net-baryon susceptibility constructed using the Ising model has a small negative value on the crossover side (small μ) and becomes positive on the first-order side (large μ). As expected, the coupling constant

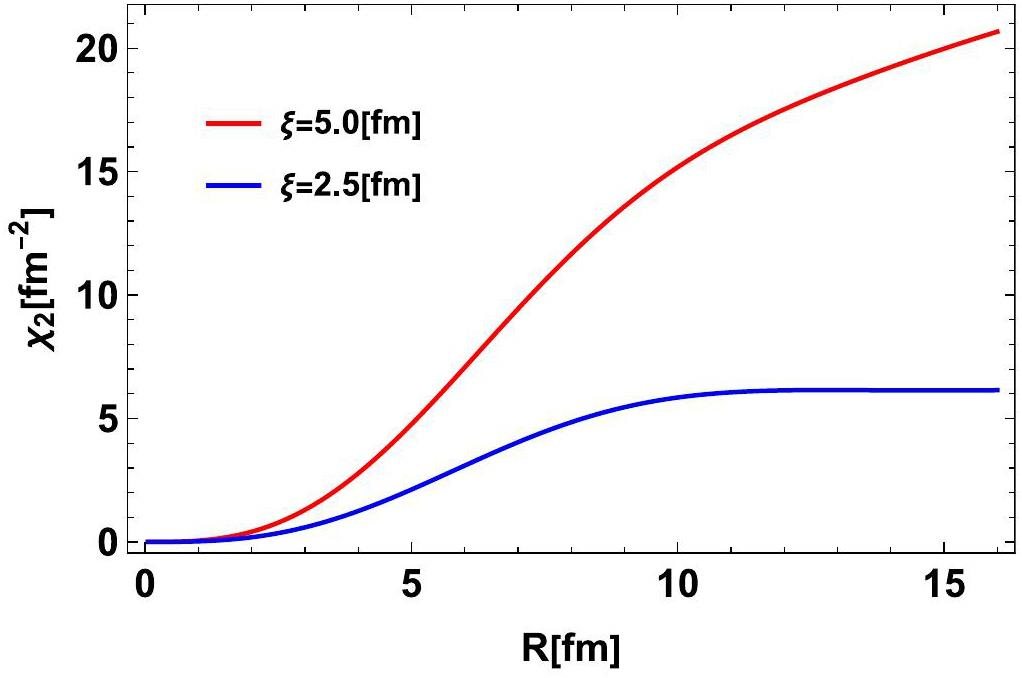

The second-order (4) and fourth-order (9) susceptibilities within the finite system were evaluated using a Monte Carlo integration algorithm. Because the knowledge of the diffusion constant D and surface tension K near the QCD critical point is limited, they are set to D=1 fm-1 and K=1 fm4, respectively, and the evolution time t is chosen as t=10 fm. These were treated as free parameters. As shown in Eq. (7), the dynamical factor

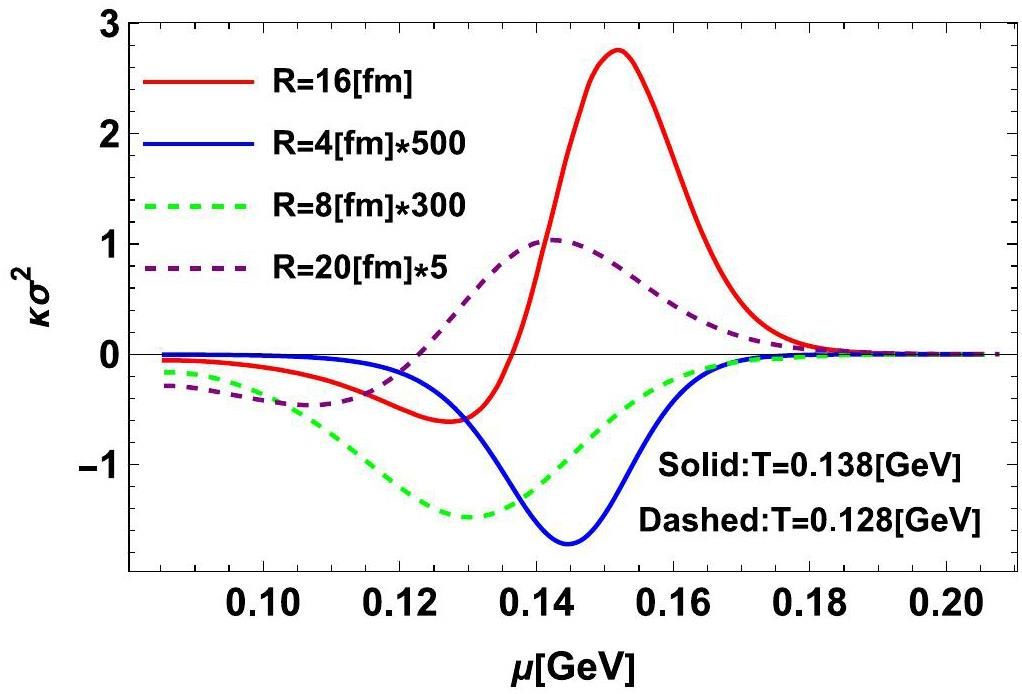

Figure 3 presents the kurtosis

Conclusion and Outlook

In summary, the signs of higher-order multiplicity fluctuations play an important role in exploring QCD phase transitions. In a simulation of the dynamics of the conserved net-baryon density near the QCD critical point, it was found that the kurtosis of the net-baryon is typically negative [26-29]. To understand negative kurtosis in conserved dynamical models, this study focuses on the sign of the kurtosis obtained within a finite system, which corresponds to only part of the system being detected. It was found that the multiplicity fluctuations (or magnitude of correlation function D_ij) are suppressed with decreasing system size when the scale of the system is small comparing correlation length. This property, called acceptance dependence, results in a negative contribution from the fourth-order coupling term λ4 (proportional to

This work focuses on the finite-size effects on the sign of kurtosis within a static system without considering dynamic modeling in a realistic experimental context. Based on the dynamical model near the QCD critical point (e.g., based on hydrodynamic model [26-29] or transport model [47-52]), the realistic finite size of the QGP fireball, as well as the finite detector acceptance window, requires proper consideration in future studies of higher-order net-proton multiplicity fluctuations. In addition, such an analysis can be performed using other possible observable critical points, such as the light nuclei yield ratio [53-56].

The Order of the quantum chromodynamics transition predicted by the standard model of particle physics

. Nature 443, 675-678 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05120Thermodynamics of strong-interaction matter from Lattice QCD

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 24,Hot-dense Lattice QCD: USQCD whitepaper 2018

. Eur. Phys. J. A 55, 194 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12922-0Lattice QCD and heavy ion collisions: a review of recent progress

. Rept. Prog. Phys. 81,QCD at finite temperature and chemical potential from Dyson–Schwinger equations

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 105, 1-60 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2019.01.002The phase diagram of dense QCD

. Rept. Prog. Phys. 74,The phase diagram of nuclear and quark matter at high baryon density

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 72, 99-154 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.05.003QCD at finite temperature and density within the fRG approach: an overview

. Commun. Theor. Phys. 74,QCD phase structure at finite temperature and density

. Phys. Rev. D 101,Properties of the phase diagram from the Nambu-Jona-Lasino model with a scalar-vector interaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 166 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01559-2Signatures of the tricritical point in QCD

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 4816-4819 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.4816QCD Phase Diagram and the Critical Point

. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 153, 139-156 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.153.139Non-Gaussian fluctuations near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,On the sign of kurtosis near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107,Using higher moments of fluctuations and their ratios in the search for the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. D 82,Search for the QCD critical point with fluctuations of conserved quantities in relativistic heavy-ion collisions at RHIC: An overview

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 112 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0257-0Nonmonotonic Energy Dependence of Net-Proton Number Fluctuations

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Cumulants and correlation functions of net-proton, proton, and antiproton multiplicity distributions in Au+Au collisions at energies available at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Properties of the QCD matter: review of selected results from the relativistic heavy ion collider beam energy scan (RHIC BES) program

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01591-2Experimental study of the QCD phase diagram in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Slowing out-of-equilibrium near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. D 61,Hydrodynamical evolution near the QCD critical end point

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Real time evolution of non-Gaussian cumulants in the QCD critical regime

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Dynamical critical fluctuations near the QCD critical point with hydrodynamic cooling rate

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Dynamical evolution of critical fluctuations and its observation in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Diffusive dynamics of critical fluctuations near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. D 99,Modeling the diffusive dynamics of critical fluctuations near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. D 102,Critical net-baryon fluctuations in an expanding system

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Dynamics of the conserved net-baryon density near QCD critical point within QGP profile

. [arXiv:2406.12325 [nucl-th]].Fluctuations of conserved charges in relativistic heavy ion collisions: An introduction

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 90, 299-342 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2016.04.002Mapping the Phases of Quantum Chromodynamics with Beam Energy Scan

. Phys. Rept. 853, 1-87 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2020.01.005Dynamics of critical fluctuations: Theory – phenomenology – heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 1003,Dynamically Exploring the QCD Matter at Finite Temperatures and Densities: A Short Review

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38,The BEST framework for the search for the QCD critical point and the chiral magnetic effect

. Nucl. Phys. A 1017,The QCD phase diagram and Beam Energy Scan physics: a theory overview

. International Journal of Modern Physics E 33,Critical dynamical fluctuations near the QCD critical point

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Third moments of conserved charges as probes of QCD phase structure

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103,Revealing baryon number fluctuations from proton number fluctuations in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Relation between baryon number fluctuations and experimentally observed proton number fluctuations in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Acceptance dependence of fluctuation measures near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Correlated fluctuations near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Energy Dependence of Moments of Net-Proton and Net-Charge Multiplicity Distributions at STAR

. PoS CPOD2014, 019 (2015). https://doi.org/10.22323/1.217.0019Remarks on the Chiral Phase Transition in Chromodynamics

. Phys. Rev. D 29, 338-341 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.29.338Application of the renormalization group to a second order QCD phase transition

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 7, 3911-3925 (1992). [erratum: Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 7, 6951 (1992)] https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217751X92001757Static and dynamic critical phenomena at a second order QCD phase transition

. Nucl. Phys. B 399, 395-425 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(93)90502-GDynamical development of proton cumulants and correlation functions in Au+Au collisions at sNN=7.7 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Higher Moments of Net-Baryon Distribution as Probes of QCD Critical Point

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Cumulants of net-proton, net-kaon, and net-charge multiplicity distributions in Au + Au collisions at sNN=7.7, 11.5, 19.6, 27, 39, 62.4, and 200 GeV within the UrQMD model

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Explore the QCD phase transition phenomena from a multiphase transport model

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 62, 11012 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-018-9272-4The influence of hadronic rescatterings on the net-baryon number fluctuations

. [arXiv:2402.12823 [nucl-th]].Transport model study of conserved charge fluctuations and QCD phase transition in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Searching for QCD critical point with light nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01231-1Light nuclei production as a probe of the QCD phase diagram

. Phys. Lett. B 781, 499-504 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.04.035Probing QCD critical fluctuations from light nuclei production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 774, 103-107 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.09.056Light nuclei production and QCD phase transition in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. 46,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.