Introduction

The measurements and theoretical analyses of single-nucleon removal reactions are of great value in studies on the single particle strengths of atomic nuclei, which are quantitatively represented by spectroscopic factors (SFs) [1]. It is well known that the SFs extracted from (e, e’p) and single-nucleon transfer reactions are found to be 30%-50% smaller than those predicted by the configuration-interaction shell model (CISM) [2, 3]. Such a reduction or quenching of SFs, represented by the quenching factors Rs, is supposed to originate from the limited model spaces and insufficient treatment of the nucleon-nucleon correlations in the traditional CISM [4, 5]. Unlike the results from (e, e’ p) reactions, from single-nucleon transfer reactions [6-8], and from (p, 2p) and (p, pn) reactions [2, 3, 9, 10], where the Rs values of different nuclei are nearly constant, the quenching factors from intermediate energy single-nucleon removal reactions are found to have an almost linear relationship with the proton-neutron asymmetry of the atomic nuclei, ΔS (

Owing to its simplicity, the optical limit approximation (OLA) is often used in the eikonal/Glauber model analysis of intermediate- and high-energy nuclear reactions [13, 15-19]. Only the first-order term for the expansion of the full Glauber phase shift is considered in the OLA. Higher-order interactions, such as nucleon-nucleon multiple scattering processes, are neglected [20]. In Ref. [21], B. Abu-Ibrahim and Y. Suzuki found that although the Glauber model with the OLA can reasonably reproduce the total reaction cross sections of some stable ions on 9Be, 12C, and 27Al targets, it failed to reproduce the reaction cross sections and elastic scattering angular distributions of unstable nuclei.

For this, they proposed calculating the projectile-target phase shifts using nucleon-target interactions in the Glauber model calculations. This so-called nucleon-target version of the Glauber model (NTG model) has been found to considerably improve the description of the reaction cross sections and elastic scattering angular distribution data [21-23]. However, to the best of our knowledge, application of the NTG model to the analysis of single-nucleon knockout reactions and its influence on the reduction factors of single particle strengths have not yet been studied. In this study, we investigated the extent to which the Rs values of single-nucleon knockout reactions change when the NTG model is used instead of the usual OLA. Because the NTG model includes multiple scattering effects in the phase-shift functions of the colliding systems with respect to the OLA, we expect this work to provide information about the extent to which multiple scattering effects affect the description of single-nucleon removal reactions using the Glauber model.

This paper is organized as follows: The NTG model and the OLA of the Glauber model are briefly introduced in Sect. 2. The results of our calculations are given in Sect. 3, which include 1) an examination of the NTG model regarding its reproduction of the elastic scattering and total reaction cross-section data. The cases studied are the angular distributions of 12C elastic scattering from a carbon target at incident energies from 30 to 200 MeV/u and the 12C + 12C total reaction cross sections from 20 to 1000 MeV/u, 2) detailed study of the NTG model on single-nucleon removal at different incident energies, the case studied here is the 9Be 19C, 18C)X reaction, and 3) the effects of the NTG model on the reduction factors of the single particle strengths. The cases studied are single-nucleon removal cross sections of carbon isotopes 9,10,12-20C on 9Be and carbon targets within 43-250 MeV/u incident energies. The range of ΔS covered in these reactions is from -26.6 to 20.1 MeV. All results are compared with those of the OLA calculations to elucidate the influence of multiple scattering effects on these reactions. Finally, the conclusions are presented in Sect. 4.

The NTG model and the OLA

The NTG model was introduced in Refs. [21, 22]. Details of its formulae can be found in Ref. [20]. For convenience, we have summarized the necessary ones here. Let us start with the phase-shift function of a nucleon-target system

Similar to the nucleon-nucleus case in Eq. (1), the nucleus-nucleus phase shift function,

The idea of the NTG model is to replace

The profile function ΓNN in both the OLA and NTG model calculations is parameterized in a Gaussian form:

Comparisons between the NTG model and OLA in Glauber model calculations

In Ref. [30], T. Nagashisa and W. Horiuchi demonstrated the effectiveness of the NTG by comparing the description of the total reaction cross sections using the full Glauber model calculation, the NTG model, and the OLA for cases of 12,20,22C on a 12C target at various incident energies. In this work, our main purpose was to study how much the single-nucleon removal cross sections (σ-1N) change when the NTG model is used instead of the OLA. Before calculating σ-1N, we first compared our calculations for the elastic scattering angular distributions and total reaction cross sections with the experimental data and with the predictions of the OLA. The calculations were made for the 12C + 12C system. Thus, we verified the effectiveness of the ΓNN parameters used in our calculations, which were further used in the calculations of σ-1N. Single-nucleon removal reactions were calculated using a modified version of the computer code MOMDIS [31].

Elastic scattering angular distributions and total reaction cross sections

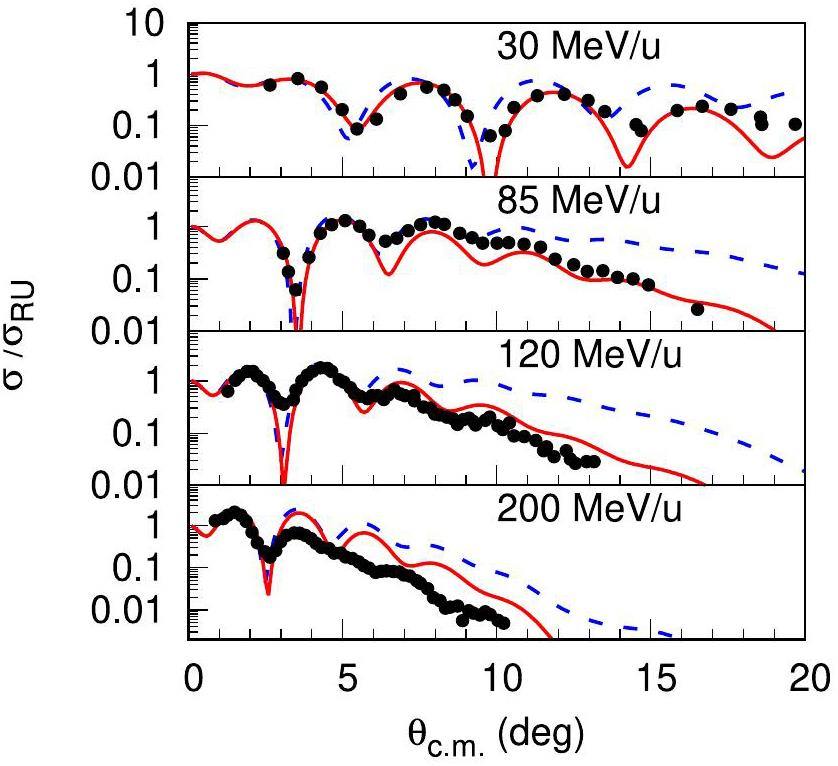

The angular distributions of 12C elastic scattering from a 12C target at 30, 85, 120, and 200 MeV/u were calculated with both the OLA and NTG model. The results are presented in Fig. 1 together with the experimental data. The dots are experimental data from Refs. [32, 33]. Clearly, the NTG improved the description of the 12C + 12C elastic scattering considerably with respect to the OLA, especially when the incident energy was below approximately 100 MeV/u. This is expected because the multiple scattering effect, which is included in the NTG model but not in the OLA, is more important at low incident energies than at higher incident energies. Note that other corrections owing to, for instance, the antisymmetrization of the projectile and target wavefunctions [34], Fermi motion of the nucleons in the colliding nuclei [35], and distortion of the trajectories [18] can also affect the low-energy cross sections. More complete calculations that consider these aspects together may be an interesting subject for the future.

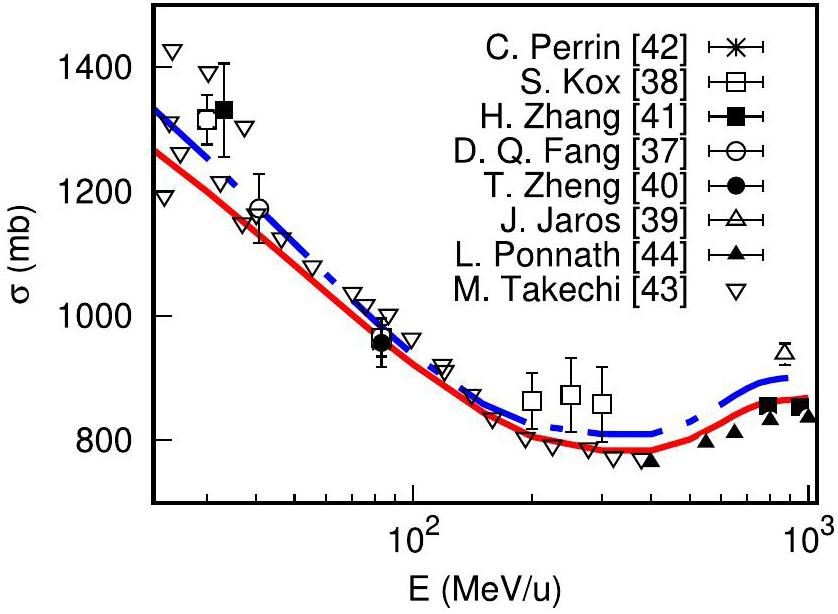

A comparison of the NTG and OLA predictions and the total reaction cross sections of the 12C + 12C system is shown in Fig. 2. The symbols represent experimental data from Ref. [36-43]. Again, we see that the results of the NTG model are in better agreement with the experimental data than those of the OLA, especially for incident energies of several tens of MeV/u and above, where most of the one-nucleon removal cross-sectional data were measured [12]. In both elastic scattering and total reaction cross section calculations, the proton and neutron density distributions of the 12C nucleus are taken to be a Gaussian form with a root mean square radius of 2.32 fm [12], which is very close to the

Note that the ΓNN parameters are the same in both the NTG and OLA calculations. The only difference between these two methods is that the former introduces multiple scattering effects in the calculation of the eikonal phase functions. The improvement provided by the NTG model in the description of elastic scattering angular distributions and total reaction cross sections suggests that nuclear medium effects, such as the multiple scattering effect studied here, should be considered in the Glauber model description of nuclear reactions induced by heavy ions. In the following section, we study how the NTG model could affect the theoretical predictions of the single-neutron removal cross sections and single particle strengths obtained from the experimental data.

Single-nucleon removal cross sections at different incident energies

In an inclusive single-nucleon removal reaction

Experimentally, single-nucleon removal cross sections are usually measured inclusively, that is, only the core nucleus b is measured without discriminating its energy states. Correspondingly, theoretical calculations for these measurements should also include the contributions from all the bound excited states of the core nucleus b [13], which corresponds to a summation of all the single-particle cross sections associated with all possible single particle wave functions:

To see how much difference the NTG model predicts in the single-nucleon removal cross sections with respect to the OLA, we study the (C19C, 18C) reaction on a 9Be target at 64, 100, 200, and 400 MeV/u incident energies. The excited states of the 18C nucleus, the associated single-particle wave functions, and their corresponding shell model predicted spectroscopic factors are taken to be the same as those in Ref. [15]. The single-particle wave functions are calculated with single particle potentials of the Woods–Saxon forms with the depths adjusted to provide the experimental separation energies of the valence nucleon. The radius and diffuseness parameters were taken to be r0=1.25 fm and

| Ex (MeV) | nlj | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 0.000 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.580 | 104.31 | 109.3 | 1.050 |

| 2.144 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.470 | 18.93 | 21.16 | 1.118 | |

| 3.639 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.104 | 3.53 | 3.98 | 1.127 | |

| 3.988 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.319 | 17.82 | 19.72 | 1.107 | |

| 4.915 | 3+ | 0d5/2 | 1.523 | 46.18 | 52.21 | 1.131 | |

| 4.975 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.922 | 27.83 | 31.46 | 1.130 | |

| Inclusive | 218.42 | 237.83 | 1.089 | ||||

| 100 | 0.000 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.580 | 87.58 | 90.14 | 1.029 |

| 2.144 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.470 | 17.95 | 19.13 | 1.066 | |

| 3.639 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.104 | 3.41 | 3.64 | 1.067 | |

| 3.988 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.319 | 16.43 | 17.44 | 1.061 | |

| 4.915 | 3+ | 0d5/2 | 1.523 | 45.05 | 48.24 | 1.071 | |

| 4.975 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.922 | 27.15 | 29.08 | 1.071 | |

| Inclusive | 197.57 | 207.67 | 1.051 | ||||

| 200 | 0.000 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.580 | 61.66 | 63.55 | 1.031 |

| 2.144 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.470 | 15.46 | 16.52 | 1.069 | |

| 3.639 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.104 | 3.01 | 3.23 | 1.073 | |

| 3.988 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.319 | 13.47 | 14.30 | 1.062 | |

| 4.915 | 3+ | 0d5/2 | 1.523 | 40.59 | 43.61 | 1.071 | |

| 4.975 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.922 | 24.48 | 26.31 | 1.075 | |

| Inclusive | 158.67 | 167.52 | 1.056 | ||||

| 400 | 0.000 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.580 | 54.76 | 57.04 | 1.042 |

| 2.144 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.470 | 14.61 | 16.00 | 1.095 | |

| 3.639 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.104 | 2.87 | 3.16 | 1.101 | |

| 3.988 | 0+ | 1s1/2 | 0.319 | 12.54 | 13.57 | 1.082 | |

| 4.915 | 3+ | 0d5/2 | 1.523 | 38.80 | 42.91 | 1.106 | |

| 4.975 | 2+ | 0d5/2 | 0.922 | 23.41 | 25.89 | 1.106 | |

| Inclusive | 146.99 | 158.57 | 1.079 |

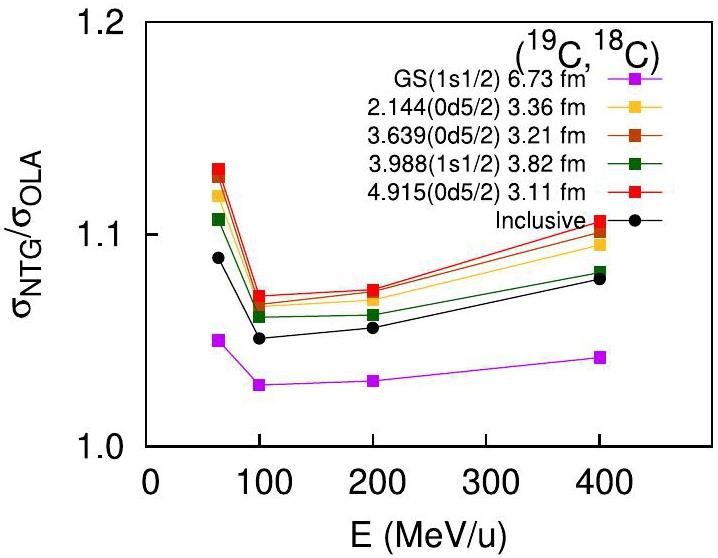

It is interesting to note the following:

1. The one-nucleon removal cross sections calculated with the NTG model are larger than those calculated with the OLA within the whole energy range from 50 to 400 MeV/u.

2. Such differences are larger at incident energies smaller than approximately 100 MeV/u, almost constant around 100-200 MeV/u, and increase slightly when the incident energy is larger than approximately 200 MeV/u,

3. The differences are also more significant when the root mean square radius of the single-particle wave function is smaller, which means that the NTG model is especially important for one-neutron removal cross sections of a given reaction when the single nucleon is tightly bound.

The same was observed for the other nuclei examined in this study. The difference between the NTG model and the OLA is in the core-target S-matrix, Sc, only. However, as expressed in Eqs. (18) and (19), we cannot separate Sc from Sv and the single-particle wave functions when calculating the single-nucleon removal cross sections. Thus, we cannot show how the NTG model affects the σ-1N values with respect to the OLA. In the following subsection, we discuss how the spectroscopic factors extracted from the experimental data and their reduction factors change when the NTG model is used instead of the OLA.

Reduction factors of single particle strengths

The spectroscopic factors in Eq. (22) are often obtained from configuration interaction shell model (CISM) calculations to determine one-nucleon removal cross sections. Owing to limited model spaces and insufficient treatment of nucleon-nucleon correlations, it is well known that CISM-predicted SFs are usually larger than the experimental ones. The reduction factors of the SFs, Rs, which are ratios of the experimental and theoretical SFs, are defined to quantify the differences. In the case of inclusive single-nucleon knockout reactions, the reduction factors are defined as the ratios between the experimental and theoretical cross sections [11, 12]:

We analyzed a series of single-nucleon removal reaction data by using the method described in the previous subsection. The details of these reactions, such as the target nuclei used and incident energies, are listed in Table 2. The theoretical predicted single-nucleon removal cross sections using the NTG and the OLA,

| Reaction | ΔSeff (MeV) | Target | Einc (MeV/u) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (20C, 19C) | -26.574 | C | 240 | 58(5) [51] | 47.55 | 51.88 | 1.22(11) | 1.12(10) |

| (19C, 18C) | -24.142 | Be | 57 | 264(80) [52] | 179.06 | 201.62 | 1.47(45) | 1.31(40) |

| -24.104 | Be | 64 | 226(65) [53] | 176.69 | 195.48 | 1.28(37) | 1.16(33) | |

| -23.754 | C | 243 | 163(12) [51] | 134.75 | 146.63 | 1.21(9) | 1.11(8) | |

| Average | -24.022 | 1.22(8) | 1.12(8) | |||||

| (18C, 17C) | -21.793 | C | 43 | 115(18) [49] | 103.20 | 128.70 | 1.11(17) | 0.89(14) |

| (17C, 16C) | -20.130 | C | 49 | 84(8) [49] | 92.80 | 109.70 | 0.91(9) | 0.77(7) |

| -20.121 | Be | 62 | 115(14) [52] | 87.80 | 100.77 | 1.31(16) | 1.14(14) | |

| -20.121 | Be | 79 | 116(18) [54] | 90.37 | 100.48 | 1.28(20) | 1.15(18) | |

| Average | -20.124 | 1.03(7) | 0.88(6) | |||||

| (15C, 14C) | -18.275 | C | 54 | 137(16) [49] | 180.56 | 196.44 | 0.76(9) | 0.70(8) |

| -18.242 | C | 62 | 159(15) [49] | 176.11 | 189.78 | 0.90(8) | 0.84(8) | |

| -18.169 | C | 83 | 146(23) [36] | 166.44 | 176.08 | 0.88(14) | 0.83(13) | |

| -17.879 | Be | 103 | 146(23) [53] | 142.52 | 149.89 | 0.98(3) | 0.94(3) | |

| Average | -18.155 | 0.95(3) | 0.90(0) | |||||

| 16C, 15C) | -18.055 | C | 55 | 65(6) [49] | 90.90 | 103.73 | 0.72(7) | 0.63(6) |

| -18.053 | C | 62 | 77(9) [49] | 89.78 | 101.10 | 0.86(10) | 0.76(9) | |

| -18.045 | Be | 75 | 81(7) [50] | 81.99 | 90.94 | 0.99(9) | 0.89(8) | |

| -18.094 | C | 83 | 65(5) [52] | 86.75 | 94.87 | 0.75(6) | 0.69(5) | |

| Average | -18.051 | 0.80(4) | 0.71(3) | |||||

| (14C, 13C) | -10.807 | C | 67 | 65(4) [49] | 133.284 | 148.61 | 0.49(3) | 0.44(3) |

| -10.800 | C | 83 | 67(14) [36] | 130.74 | 142.66 | 0.51(13) | 0.47(12) | |

| -10.767 | C | 235 | 80(7) [55] | 110.92 | 121.39 | 0.72(6) | 0.66(6) | |

| Average | -10.793 | 0.53(3) | 0.48(2) | |||||

| (12C, 11C) | 3.259 | C | 95 | 53(22) [56] | 102.21 | 111.06 | 0.52(22) | 0.48(20) |

| 3.266 | C | 240 | 60.51(11.08) [57] | 94.12 | 104.37 | 0.64(12) | 0.58(11) | |

| 3.265 | C | 250 | 56.0(41) [58] | 93.73 | 104.31 | 0.60(4) | 0.54(4) | |

| Average | 3.263 | 0.60(4) | 0.54(4) | |||||

| (10C, 9C) | 17.277 | Be | 120 | 23.4(11) [59] | 47.40 | 51.65 | 0.49(2) | 0.45(2) |

| 17.277 | C | 120 | 27.4(13) [59] | 49.72 | 54.36 | 0.55(3) | 0.50(2) | |

| Average | 17.277 | 0.52(2) | 0.48(2) | |||||

| (9C, 8B) | -12.925 | Be | 67 | 48.6(73) [60] | 62.77 | 66.67 | 0.77(12) | 0.73(11) |

| -12.925 | Be | 100 | 56(3) [61] | 58.77 | 59.72 | 0.95(5) | 0.94(5) | |

| Average | -12.925 | 0.92(5) | 0.90(5) | |||||

| (12C, 11B) | -2.237 | C | 230 | 63.9(66) [62] | 103.75 | 105.33 | 0.62(6) | 0.61(6) |

| -2.237 | C | 250 | 65.6(26) [58] | 102.93 | 105.36 | 0.64(3) | 0.62(2) | |

| Average | -2.237 | 0.63(2) | 0.62(2) | |||||

| (13C, 12B) | 13.523 | C | 234 | 39.5(60) [62] | 79.69 | 81.55 | 0.43(5) | 0.40(4) |

| (14C, 13B) | 12.830 | C | 235 | 41.3(27) [62] | 78.65 | 81.43 | 0.53(3) | 0.51(3) |

| (16C, 15B) | 18.303 | Be | 75 | 18(2) [50] | 60.23 | 62.50 | 0.30(3) | 0.29(3) |

| 18.303 | Be | 239 | 16(2) [63] | 56.86 | 58.45 | 0.28(4) | 0.27(3) | |

| 18.303 | C | 239 | 18(2) [62] | 54.57 | 55.87 | 0.33(4) | 0.32(4) | |

| Average | 18.303 | 0.30(2) | 0.28(2) | |||||

| (15C, 14B) | 20.134 | C | 237 | 28.4(28) [62] | 55.36 | 57.58 | 0.51(5) | 0.49(5) |

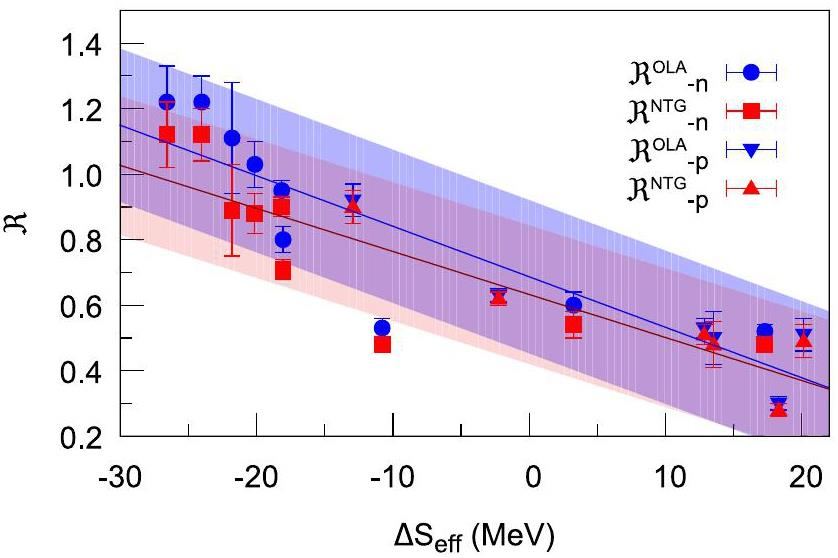

As shown in Table 2, σ-1N values predicted with the NTG model are generally larger than those predicted with the OLA. Thus, the

A closer examination of Fig. (4) shows that the differences between

Summary

The reduction in single particle strengths, represented by the reduction factors of single-nucleon spectroscopic factors extracted from experimental data with respect to the configuration interaction shell model predictions, is supposed to be related to the nucleon-nucleon correlations in atomic nuclei. Much theoretical and experimental effort has been devoted to this field of research. One of the open questions is why the reduction factors obtained from intermediate- and high-energy single-nucleon removal cross sections such as those compiled in Refs. [11, 12] show strong linear dependence on the neutron-proton asymmetry, whereas those of other types of reactions, such as (p, pN) and single-nucleon transfer reactions, do not [2, 3, 6, 9, 64, 65]. Because single-nucleon removal reactions were analyzed using the Glauber model, the validity of the Glauber model for such reactions is being questioned. In this respect, corrections to the Glauber model and an examination of their effects on single-nucleon removal cross sections are important.

In this study, we examined how the nucleon-target version of the Glauber model (the NTG model), which introduces multiple scattering of the constituent nucleons in the projectile and the target nuclei, can change the theoretically predicted single-nucleon removal cross sections with respect to the usual optical limit approximation, which does not contain multiple scattering effects. For this purpose, we first examined the NTG model in its reproduction of the elastic scattering angular distributions and the total reaction cross sections of the 12C + 12C system, and compared their results with the experimental data and those calculated with the OLA. The NTG model was found to improve the description of the elastic scattering angular distributions, particularly at lower incident energies. Both the elastic scattering and total reaction cross sections calculated in this work agree well with those reported in previous publications, for example, Refs. [21, 23, 30].

We then compared the predictions of the inclusive single-nucleon removal cross sections using the NTG model and OLA. The case studied is the 9Be (19C, 18C)X reaction within the incident energy range from 64 MeV/u to 400 MeV/u. The

Finally, we studied the extent to which the reduction factors of the single particle strengths obtained from single-nucleon removal reactions changed when the NTG model was used instead of the OLA. The cases studied are one-nucleon removal reactions induced by 9,10,12-20C isotopes on carbon and 9Be targets. On average, the reduction factors obtained with the NTG model were found to be less than those obtained with the OLA by 7.8%. We also found that the average differences in

Quenching of cross sections in nucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111,Quenching of single-particle strength in A=15 nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129,Independent particle motion correlations in fermion systems

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 981-991 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.69.981Self-consistent green’s function method for nuclei nuclear matter

. Progress in Particle Nuclear Physics 52, 377-496 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2004.02.038Proton–neutron asymmetry independence of reduced single-particle strengths derived from (p, d)reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 790, 308 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.01.034Experimental study of intruder components in light neutron-rich nuclei via single-nucleon transfer reaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-0731-ySystematic investigation of nucleon optical model potentials in (p, d) transfer reactions

. Chin. Phys. C 48,Quasifree (p, 2p) reactions on oxygen isotopes: Observation of isospin independence of the reduced single-particle strength

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120,Single-particle strength from nucleon transfer in oxygen isotopes: Sensitivity to model parameters

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Systematics of intermediate-energy single-nucleon removal cross sections

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Updated systematics of intermediate-energy single-nucleon removal cross sections

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Direct reactions with exotic nuclei

. Annual Review of Nuclear Particle Science 53, 219-261 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.53.041002.110406Multiple mechanisms in proton-induced nucleon removal at ~ 100 MeV/Nucleon

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,One- two-neutron removal from the neutron-rich carbon isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Core destruction in knockout reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 846,Neutron skin and its effects in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 211 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01584-1Nuclear radii from total reaction cross section measurements at intermediate energies with complex turning point corrections to the eikonal model

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Impact of initial fluctuations and nuclear deformations in isobar collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01480-8Scatterings of complex nuclei in the glauber model

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Utility of nucleon-target profile function in cross section calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Systematic analysis of reaction cross sections of carbon isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Multiple-scattering effects in proton- and alpha-nucleus reactions with Glauber theory

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 569,Proton-nucleus total cross sections in the intermediate energy range

. Phys. Rev. C 20, 1857-1872 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.20.1857Validation of elastic cross section models for space radiation applications

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. B 392, 74-93 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2016.12.009Review of particle physics

. PTEP 2022,Cross sections of removal reactions populating weakly-bound residual nuclei

. arXiv.2203.06058 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.06058Examination of the 22C radius determination with interaction cross sections

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Momdis: a glauber model computer code for knockout reactions

. Computer Physics Communications 175, 372-380 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2006.04.006Elastic inelastic scattering of 12C ions at intermediate energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 490 441-470 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(88)90514-3Elastic inelastic scattering of carbon ions at intermediate energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 424, 313-334 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(84)90186-6Elastic scattering and deuteron-induced transfer reactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 465, 83-122 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(87)90300-9Reaction cross sections at intermediate energies and Fermi-motion effect

. Phys. Rev. C 79,One-neutron halo structure in 15C

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Trends of total reaction cross sections for heavy ion collisions in the intermediate energy range

. Phys. Rev. C 35, 1678-1691 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.35.1678Nucleus-nucleus total cross sections for light nuclei at 1.55 2.89 Gev/c per nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 18, 2273-2292 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.18.2273Study of halo structure of 16c from reaction cross section measurement

. Nucl. Phys. A 709, 103-118 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(02)01043-6Measurement of reaction cross section for proton-rich nuclei (A<30) at intermediate energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 707, 303-324 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(02)01007-2Direct measurement of the 12C + 12C reaction cross section between 10 83 Mev/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 1905-1909 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.1905Reaction cross-sections for stable nuclei nucleon density distribution of proton drip-line nucleus 8B

. Eur. Phys. J. A 25, 217-219 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjad/i2005-06-078-0Measurement of nuclear interaction cross sections towards neutron-skin thickness determination

. Phys. Lett. B 855,α-nucleus optical potential in the double-folding model

. Phys. Rev. C 63,Breakup reactions of the halo nuclei 11Be 8B

. Phys. Rev. C 54, 3043-3050 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.54.3043Center-of-mass effects in single-nucleon knock-out reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 10, 543 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.10.543Quenching of single-particle strengths of carbon isotopes 9-12,14-20C with knockout reactions for incident energies 43-2100 Mev/nucleon *

. Chinese Phys. C 46,Determining the radii of single particle potentials with skyrme hartree fock calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 110,One-neutron removal reactions on light neutron-rich nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Nonsudden limits of heavy-ion induced knockout reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108,One-two-neutron removal reactions from the most neutron-rich carbon isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Single-neutron knockout reactions: Application to the spectroscopy of 16,17,19C

. Phys. Rev. C 63,Absolute spectroscopic factors from neutron knockout on the halo nucleus 15C

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Neutron removal reactions of 17C

. J. Phys. G. Nucl. Partic. 31, 39 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/31/1/004Single-neutron removal from 14,15,16C near 240 Mev/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Double-differential fragmentation cross-section measurements of 95 Mev/nucleon 12c beams on thin targets for hadron therapy

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Data analysis framework for radioactive ion beam experiments at the external target facility of hirfl-csr

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 37, 742 (2020). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.37.2019CNPC27Absolute spectroscopic factors from nuclear knockout reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Systematic study of p-shell nuclei via single-nucleon knockout reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Single-nucleon knockout cross sections for reactions producing resonance states at or beyond the drip line

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Mechanisms in knockout reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,One-proton removal from neutron-rich carbon isotopes in 12–16C beams near 240 mev/nucleon beam energy

. Phys. Rev. C 110,One-proton knockout from 16C at around 240 Mev/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Limited asymmetry dependence of correlations from single nucleon transfer

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Binding-energy independence of reduced spectroscopic strengths derived from (p,2p) (p,pn) reactions with nitrogen oxygen isotopes

. Phys. Lett. B 785, 511-516 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.08.058Cen-Xi Yuan is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.