Introduction

The illicit proliferation of special nuclear materials (SNMs) enables terrorists to acquire weapons of mass destruction. The conventional scanning systems deployed at national borders typically use X-rays to obtain the density distribution of the scanned object and cannot differentiate SNMs from other high-density metals, such as lead, tungsten, and bismuth. Therefore, efforts have been made to realize on-site, nondestructive identification of SNMs. SNM detection methods can be categorized as passive and active. Passive interrogation detects naturally emitted γ-rays or neutrons from the radioactive decay of SNMs [1-4]. However, this technique is unsuitable for detecting shielded objects because the intensities and energies of the spontaneous radiation are relatively low. In contrast, active interrogation employs an external radiation source and effectively overcome such limitations. The response was optimized by adjusting the energy and intensity of the interrogation radiation source. The primary radiation sources for interrogation were neutrons, muons, and photons. Neutron fission reactions with fissile materials characterized by both high penetrability and cross sections have been extensively researched [5-8]. However, in the context of radiation safety, neutrons are difficult to handle and the neutron capture reactions induced in nearly all materials generate an additional radiation background, which hinders signal discrimination. Furthermore, neutron-generation devices such as spallation neutron sources or nuclear reactors typically require large areas and are thus unsuitable for widespread applications. Muon scattering tomography technology based on cosmic-ray muons for detecting SNMs has also been extensively investigated [9-11]. However, muon-generation devices are complex, expensive, and unsuitable for broad usage. Photons are often preferred over neutrons and muons because of their lower induction of radioactivity in most materials. To date, photon-induced reactions can be used to detect explosives [12] and identify SNMs based on nuclear resonance fluorescence(NRF) [13-15]. However, owing to the narrow resonance width of NRF reactions (∼meV), γ-ray sources with high spectral and temporal intensities are required to obtain sufficient signals within a reasonable irradiation time. These limitations necessitate the development of photofission-based SNM detection methods.

Photofission is the process in which a fissile nucleus splits into two fragments (light and heavy) after absorbing an incident photon, accompanied by the instantaneous emission of prompt neutrons and prompt γ rays. The radioactive fragments decay into stable nuclides, releasing delayed γ rays. As the thresholds for most photonuclear reactions are typically above 7 MeV, background radiation from photofission is relatively low. Currently, most research on identifying SNMs based on photofission has focused on 235,238U and 239Pu. These studies identified and quantitatively analyzed certain nuclides [16-20] and constructed an analysis algorithm for the delayed γ energy spectrum of SNMs in simulations [21, 22]. Additionally, the use of delayed γ-ray ratios for SNM differentiation, which was first proposed by Hollas et al. [23] has received considerable attention. Finch et al. [24] utilized three high-purity germanium (HPGe) detectors to distinguish between 235,238U and 239Pu. Nevertheless, the high cost and neutron damage of HPGe detectors make them vulnerable to fission reactions, hindering the repeated implementation and practical applications of this method. Therefore, a detection method that can be widely applied to isotopes is of great significance. Methods for identifying a broader range of SNMs including 233,235,238U, 239-242Pu, and 232Th, are required. The existence and identification of additional isotopes of U, Pu, and Th must be considered to effectively manage SNMs.

The rapid development of high-intensity γ-ray facilities in China has presented new opportunities for photofission research. Recently, the Shanghai Laser Electron Gamma Source beamline at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility was completed and is in operation, providing additional platforms for fields such as photonuclear physics [25, 26]. Moreover, laser-driven γ ray sources can reach extremely high intensities and offer a wide range energies. γ rays with intensities above 1019/s (108/shot, above 4 MeV) were generated using the 200 TW laser facility at the Compact Laser Plasma Accelerator (CLAPA) Laboratory [27], where significant photonuclear research has been conducted [28-33]. Laser-driven γ-ray sources can be miniaturized and are well-suited for widespread use in customs and railway security. These emerging quasi-monoenergetic γ-source devices [34, 35] and high-intensity γ-ray facilities provide broad application prospects for photofission research and SNM identification.

In this work, we systematically investigated methods to identify the elements and isotopes of SNMs by detecting delayed γ-rays from photofission fragments. Geant4 [36] simulations were performed on the photofission of SNM isotopes, including 233,235,238U, 239-242Pu, and 232Th. To identify the potential fragment ratios suitable for SNM identification, the mass and charge yield distributions of photofission fragments induced by monochromatic γ sources and their delayed γ spectra recorded by an HPGe detector were obtained. The yields of fission fragments were calculated according to the delayed γ spectrum. The ratios of three high-yield fission fragments, 138Cs, 94Y, and 89Rb, were selected as identification values to differentiate between the SNMs. Additionally, the dependence of the fragment ratios on incident γ-ray energy was investigated. The count rates of delayed γ rays with energies above 3 MeV recorded by a LaBr3 detector were calculated and used to rapidly detect the presence of nuclear material within the scanned object. This comprehensive approach provides better understanding and control of SNMs.

Method

The fission fragments of different fissile nuclei exhibited variations, and the charge and mass yield distributions shifted towards larger masses as the mass of the fissile nucleus increased. Hence, the yield ratios of the fission fragments may be employed as identification parameters to distinguish between different fission nuclei. In reality, the fragment yields must be calculated from the detected delayed γ-ray spectra according to parameters such as the delayed γ-ray intensity, detection efficiency, and attenuation in the target. Consequently, simulations of delayed γ-ray detection are necessary to obtain insight into the identification of SNMs.

The Geant4 photofission module developed in our laboratory was employed to simulate the detection of delayed γ-rays from photofission fragments [37, 38]. In this module, the mass and charge yield distributions of the fission fragments are based on the Bohr-substitution Gorodisskiy model [38, 39]. The model describes the characteristics of photofission reaction products from actinides, such as prompt neutrons, prompt photons, and fission fragments. The results have been extensively benchmarked against available experimental data and showed good agreement. In addition, the G4RadioactiveDecay physics was implemented in our code to model the delayed γ emissions from fission fragments and simulate the photofission process of SNMs in this study.

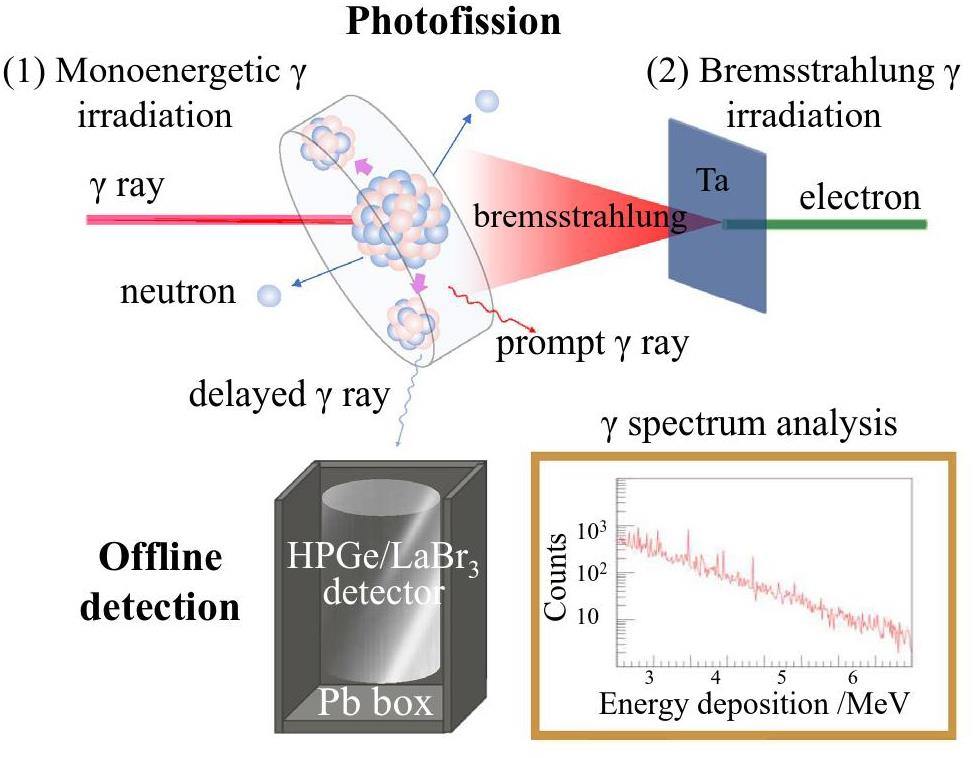

An illustration of the simulation setup is shown in Fig. 1. The monoenergetic γ source or the bremsstrahlung γ source was obliquely incident at 45° on eight types of 1-cm-thick SNM targets, resulting in photofission reactions. A LaBr3 detector with a size of 8 cm × 16 cm was placed perpendicular to the γ beam and parallel to the target to detect γ rays. Owing to the high detection efficiency of LaBr3 detectors, the count rate of fission γ rays above 3 MeV was obtained, which instantly indicated the presence of SNMs. HPGe detectors, which have high resolution, are suitable for measuring and analyzing the peak structure of complex delayed γ-spectra. Five minutes after the fission reaction, an HPGe detector with a relative efficiency of 80% was used to detect the delayed γ-rays from the fragments. The counts of characteristic γ peak of most high-yield product nuclides was determined using the delayed γ spectrum of photofission products measured by the HPGe detector. The yield of the fission fragments was calculated using γ ray counts, detection efficiency simulations, and self-absorption corrections. The yield ratio, which serves as an identification characteristic for differentiating SNMs, was obtained by screening the most differentiated identification values for each SNM and their uncertainties. Furthermore, the count rates of delayed γ rays with energies above 3 MeV were used to identify nuclear materials.

The fragment yields are determined by factors such as the incident photon energy, beam intensity, target nucleus number, and photofission cross section. The fission of a heavy nucleus predominantly produces 600–800 different isotopic fragment species. Therefore, fission fragments with high yields, measurable half-lives, and significant counts of delayed γ rays must be carefully selected. To optimize the yields of the fission products, considering information on the photofission cross section in TENDL-2019 [40], a monoenergetic γ source with energies around 14 MeV was selected because it offered almost the maximum cross sections for uranium, plutonium, and thorium. 109 incident γ-rays were employed for the isotopes of uranium, plutonium, and thorium in Geant4 simulations. Regarding the measurable half-lives, the minute to hour order was suitable for detection. In conclusion, by identifying the characteristic values presented herein, we determined the yield ratios associated with each unique fission nucleus that was significantly different from other fission nuclei.

Results

Mass and Charge Yield Distribution

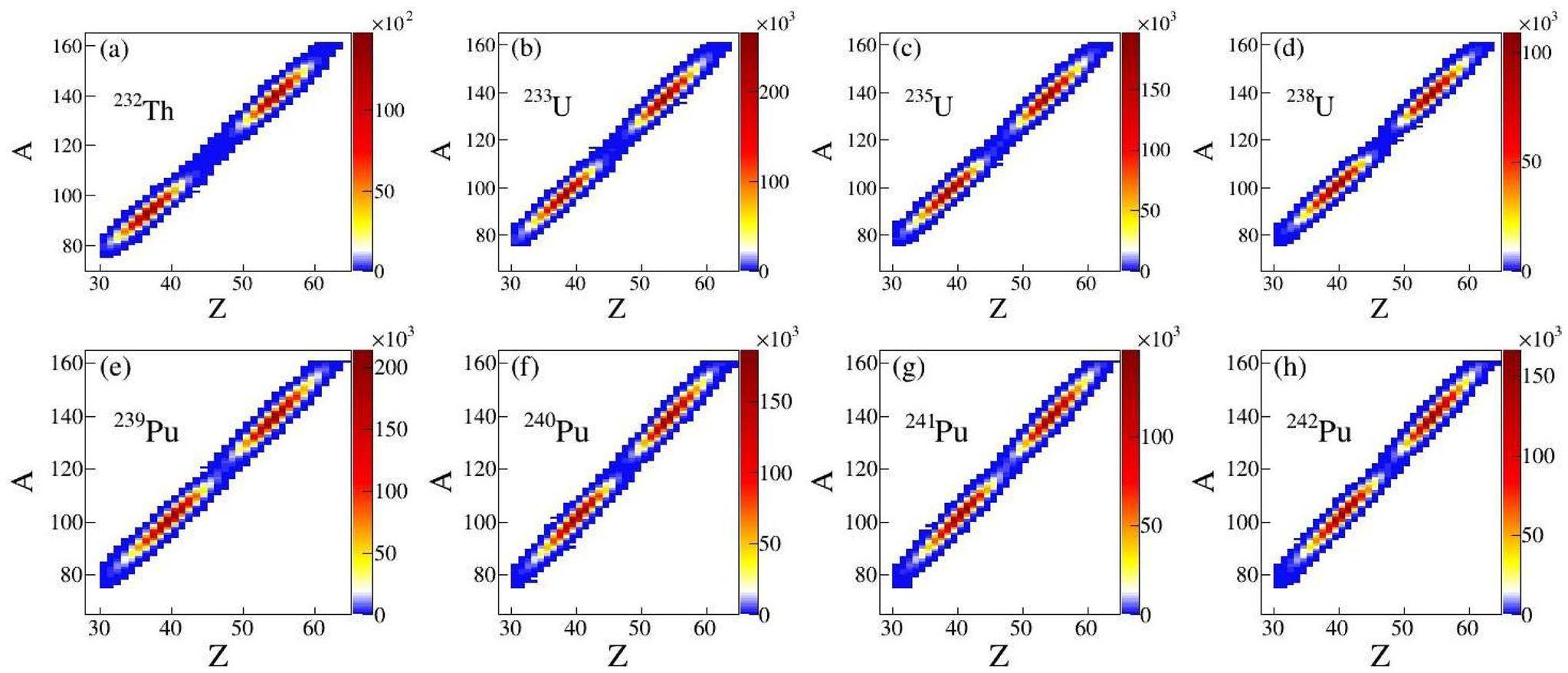

Figure 2 shows the mass and charge yield distributions of the fission fragments from the eight selected SNMs at an incident γ-ray energy of 14 MeV. The number of neutrons and protons in the fission fragments were 40–90 and 25–65, respectively. Typically, the nuclides located in the two peak areas of the figures represent the high-yield fragments; the proton numbers of lighter fragments are primarily concentrated within 36–46, while those of heavier fragments are concentrated within 50-60. Differences in the high-yield fragments among U, Pu, and Th were observed (Fig. 2). Figure 2(b-d) show that the overall fragment yield decreases with increasing target mass numbers for the isotopes of 233,235,238U. For 239-242Pu isotopes, the decrease in fragment yields with the target mass number is less linear, as shown in Fig. 2(e-h). Moreover, the mass and charge yield distributions of the eight selected isotopes exhibited discrepancies. These features indicate that fragment yields and ratios can be used to discriminate between SNMs. After a comprehensive analysis of the mass and charge yield distributions, a preliminary candidate list of high-yield fragments that might be suitable for use in further SNM discrimination was identiified: 86Se, 89Rb, 94Y, 95Y, 98Y, 102Nb, 129Sb, 132I, 132Cs, 138Cs, and 138Xe. These high-yield fragments were selected as preliminary screening results to aid the subsequent search for characteristic peaks in the complex delayed γ spectrum and served as a basis for choosing the measurement time of the HPGe detector.

Delayed γ-ray Spectrum

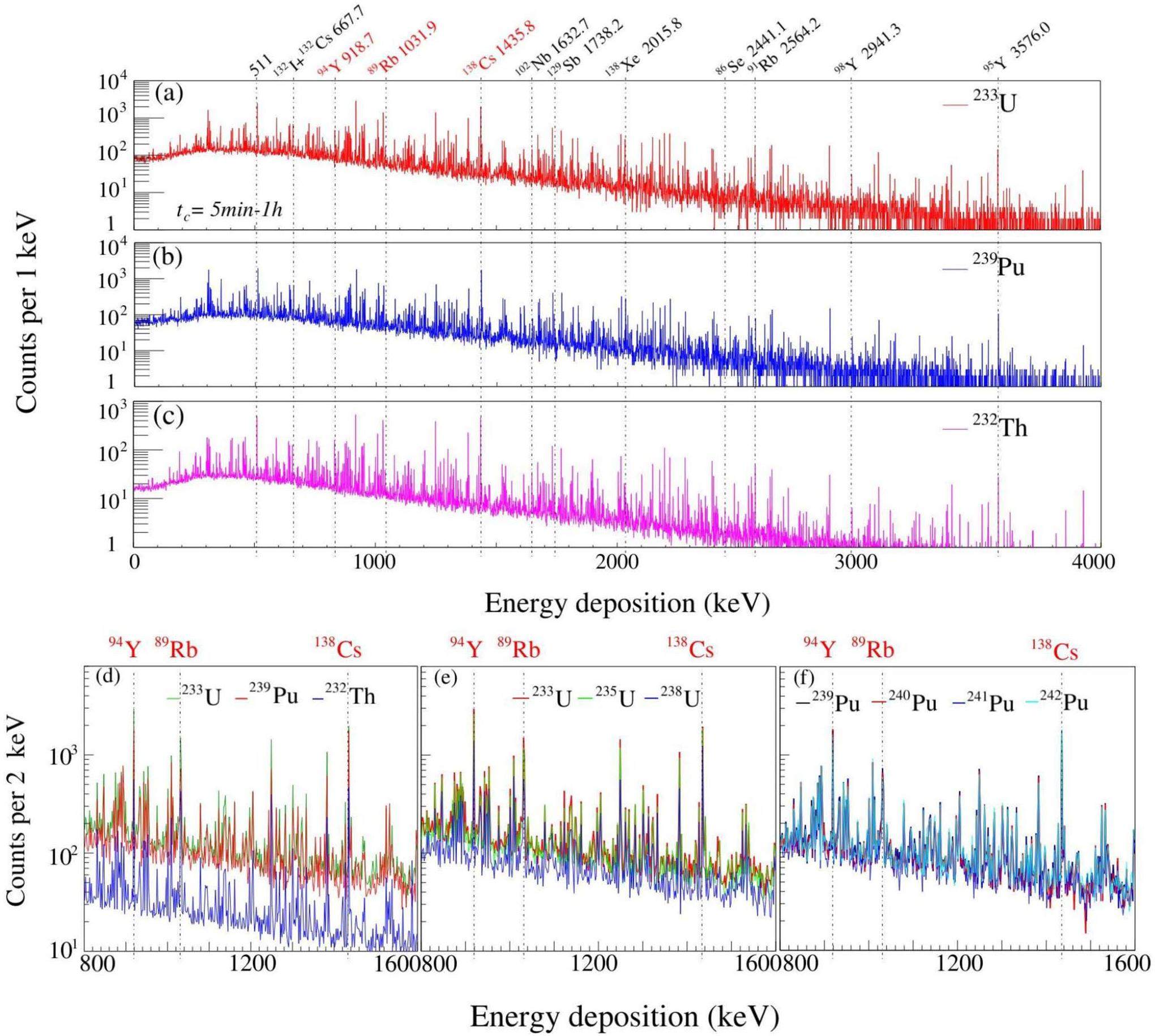

The typical delayed γ-ray spectra from the fission fragments of 233U, 239Pu, and 232Th recorded by the HPGe detector are shown in Fig. 3. Gamma spectra with energies below 511 keV are complex because of the characteristic peaks from multiple sources and thus, are excluded from the analysis. The data acquisition time was varied from 5 min to 1 h after irradiation. As shown in Fig. 3(a-c), the energies of the delayed γ signals are mostly below 4 MeV. The corresponding characteristic peak counts of the fission fragments range from a few hundred to over a thousand and have good statistical errors within the achievable γ source flux. The detection efficiency of high-energy γ above 4 MeV is low; thus, it is not shown or analyzed in detail.

After the initial screening of the candidate fragment nuclides, secondary screening requires a clean source for the characteristic peak (with no other characteristic peaks present within 1 keV) and with significantly different counts for different fission nuclei. For instance, the γ peaks of 132I and 132Cs possess the same energy (667.714 keV) (Fig. 3(d-f)), which is close to the γ peak 668.536 keV of 130I. All three fragment nuclides have relatively high yields and non-negligible characteristic peak counts. When the resolution of the detector is insufficient, the overlap of these neighboring peaks affects the fragment yield determination. Furthermore, although the characteristic peaks of the candidate fragments such as 95Y and 129Sb exhibited relatively large signals, their net counts did not differ significantly among the eight SNMs. Therefore, these characteristic peaks (indicated by black tags at the top of Fig. 3), were not usable as identification fragments. After filtering these unusable candidate signals, three fragments, 94Y, 89Rb, and 138Cs, were identified as usable fragments for SNM discrimination; the corresponding magnified spectra of the signal peaks of the three fragments of the eight SNMs are shown in Fig. 3(d)–(f), respectively. The decay information for the three fragments is presented in Table 1. Furthermore, a detailed analysis of the statistical sources of the characteristic peaks is presented in Table 1 to better reflect the actual detection results. It describes two aspects: the delayed γ peaks of other nuclides with energies close to the characteristic peaks (where the resolution of the detector is insufficient) and some neutron-rich nuclei that undergo β decay to the identified nuclides within the detection time. For example, for the nuclide 94Y, which has a half-life of 18.7 minutes, the nuclides 94Sr, 94Rb, 94Kr, and 94Br produce 94Y through β decay within the detection time. The yield of 94Y calculated from the counts of the characteristic peaks is the sum of the yields of these nuclides. The last column of Tab. 1 indicates the productivities of the fragments of interest (the probability of one γ photon generating this nuclide at 14 MeV), which provides a quantitative standard for the high yield of fragments. These nuclides formed three pairs of fragment identification ratios: 94Y/89Rb, 138Cs/98Rb, and 138Cs/94Y, among which the first required the shortest measurement time.

| Fragments for identification | γ Energy (branch) | Parent nucleus | Half-life | Decay mode(branch) | Productivity (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 138Cs | 1435.77 keV (76.3%) | 32.84 min | 0.527812 | ||

| 138Xe | 14.14 min | β-(100%) | 0.000222 | ||

| 138I | 6.303 s | β-(100%) | 0.000181 | ||

| 138Te | 1.46 s | β-(100%) | 0.000018 | ||

| 138Sb | 314 ms | β-(100%) | 0.0000002 | ||

| 89Rb | 1031.92 keV (63%) | 15.39 min | 0.451795 | ||

| 89Br | 4.348 s | β-(100%) | 0.000067 | ||

| 89Se | 0.41 s | β-(100%) | 0.000139 | ||

| 89Se | 1.51 s | β-(100%) | 0.000063 | ||

| 89As | 200 ms | β-(100%) | 0.000003 | ||

| 94Y | 918.74 keV (56%) | 18.7 min | 0.706307 | ||

| 94Sr | 75.3 s | β-(100%) | 0.000120 | ||

| 94Rb | 2.704 s | β-(100%) | 0.000241 | ||

| 94Kr | 212.0 ms | β-(100%) | 0.000115 | ||

| 94Br | 70.0 ms | β-(100%) | 0.000006 |

Yield Analysis

Considering the differences in the actual detection conditions, such as measurement time variations and interrogation source energy, this study utilized the yield ratio as a convenient and generalized basis for SNM identification. Based on the delayed γ spectra recorded by the HPGe detector, the characteristic γ counts were calculated by subtracting the background±1 keV around the peak from the gross counts. The specific values of the counts and yield ratios are listed in Table 2. The yields were then calculated from the net counts, considering the delayed γ-ray intensity, detection efficiency, and target attenuation. The uncertainties in the yields and their ratios were obtained by performing least-squares fitting of the statistical error of the counts. As shown in Table 2, the net counts of 89Rb are lower than those of 94Y and 138Cs; thus, the relative uncertainty of the yield ratios involving 89Rb is higher than that of 138Cs/94Y.

| Fissile nucleus | Net counts | Yield ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 138Cs | 89Rb | 94Y | 138Cs / 89Rb | 138Cs / 94Y | 94Y / 89Rb | |

| 233U | 1788 | 1350 | 1731 | 1.168±0.04 | 0.747±0.03 | 1.563±0.06 |

| 235U | 1567 | 1126 | 1556 | 1.324±0.05 | 0.837±0.03 | 1.582±0.06 |

| 238U | 1130 | 505 | 776 | 1.953±0.10 | 1.207±0.06 | 1.618±0.09 |

| 239Pu | 1603 | 625 | 1032 | 2.207±0.10 | 1.124±0.04 | 1.963±0.10 |

| 240Pu | 1506 | 573 | 1026 | 2.416±0.12 | 1.210±0.05 | 1.996±0.10 |

| 241Pu | 1344 | 487 | 831 | 2.509±0.13 | 1.322±0.06 | 1.898±0.11 |

| 242Pu | 1635 | 500 | 856 | 2.906±0.15 | 1.546±0.07 | 1.880±0.11 |

| 232Th | 424 | 407 | 325 | 1.014±0.06 | 1.067±0.06 | 0.950±0.06 |

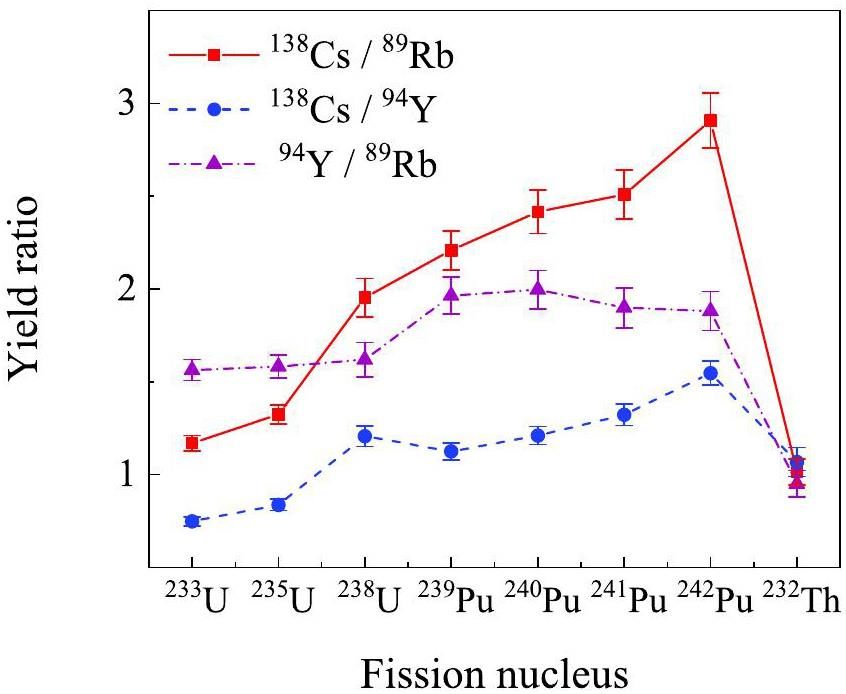

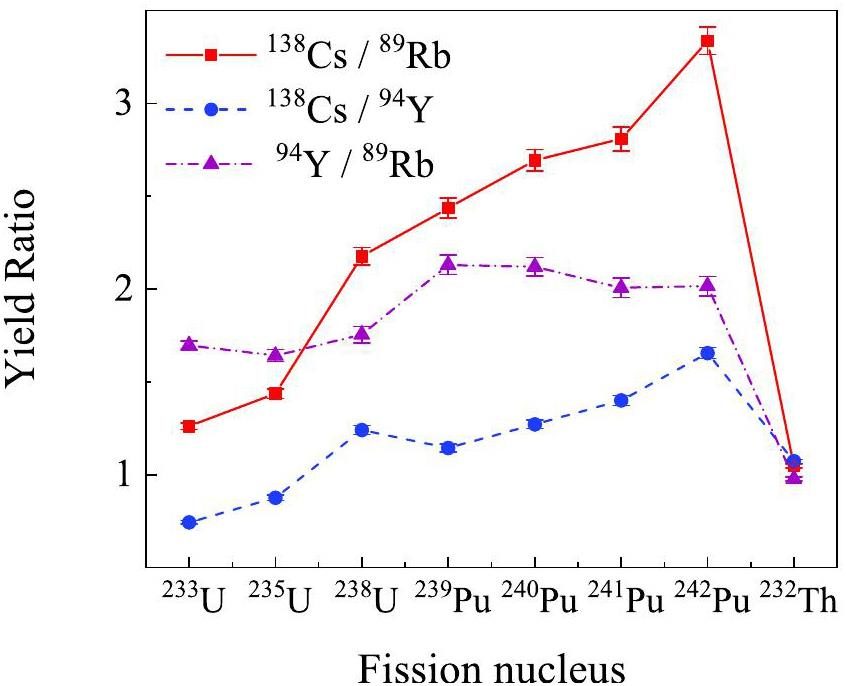

The yield ratios of the three pairs of nuclides comprising the selected fragment nuclides 138Cs, 94Y, and 89Rb were used as indicators to identify the selected SNM isotopes (Fig. 4). The confidence level was calculated to determine whether they could be distinguished from each other within the uncertainty. The yield ratio of 138Cs/89Rb differs significantly among the SNMs and can be used to distinguish the other seven nuclides except for 239-241Pu, with a high confidence level above 99.5%. Although the 94Y/89Rb ratio does not exhibit significance among the isotopes of U, Pu, and Th, it can be used for quick elemental identification. For the isotopes of Pu, the yield ratio of 138Cs/94Y is the most suitable for isotopic discrimination. This pair of nuclides exhibits the smallest uncertainty in the yield ratio and highlights the most noticeable differences among the fission nuclei, especially for 239-241Pu. However, the 138Cs/94Y ratios of 240,241Pu are similar and cannot be distinguished. When the total number of incident γ-rays increases to 1011, the isotopes of Pu can be distinguished by the yield ratios of 138Cs/89Rb and 94Y/89Rb with a high confidence level above 99.5%. Moreover, 138Cs has a half-life of 33 min, and thus, requires a longer measurement time.

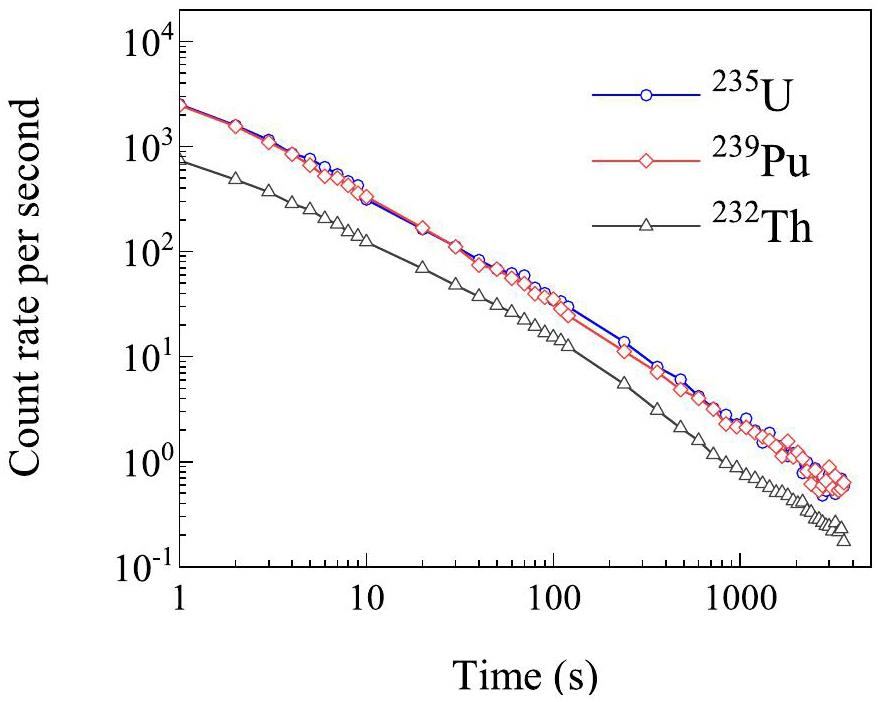

High Energy γ Counting Rate

High-energy γ rays above 3 MeV have high penetration capabilities, which have been observed intensively in the aforementioned delayed γ-ray spectra of photofission fragments of SNMs. For common shielding materials such as Pd and Bi, the photofission (or photoinduced spallation) thresholds are typically above 100 MeV, which are much larger than those of SNMs. When irradiated by a γ beam with an energy of approximately 14 MeV, these high-Z benign materials do not undergo photofission, but rather common photonuclear reactions such as (γ, xn). The delayed γ-rays typically released from the reaction residuals are mostly less than 3 MeV. Consequently, delayed γ-rays above 3 MeV from photofission may serve as an effective basis for determining the presence of nuclear materials. The γ counts above 3 MeV resulting from fragment decay were recorded using a LaBr3 detector. Figure 5 shows the change in the counting rate of the three elements U, Pu, and Th within 1-1000 s of measurement time. As shown in Fig. 5, the count rates of the three SNM elements exhibit differences that are within the error range, which is unsuitable for distinguishing between them. Because nuclear materials primarily generate high-energy γ-rays, these results provide supporting data for identifying whether they are SNMs.

Discussion and Summary

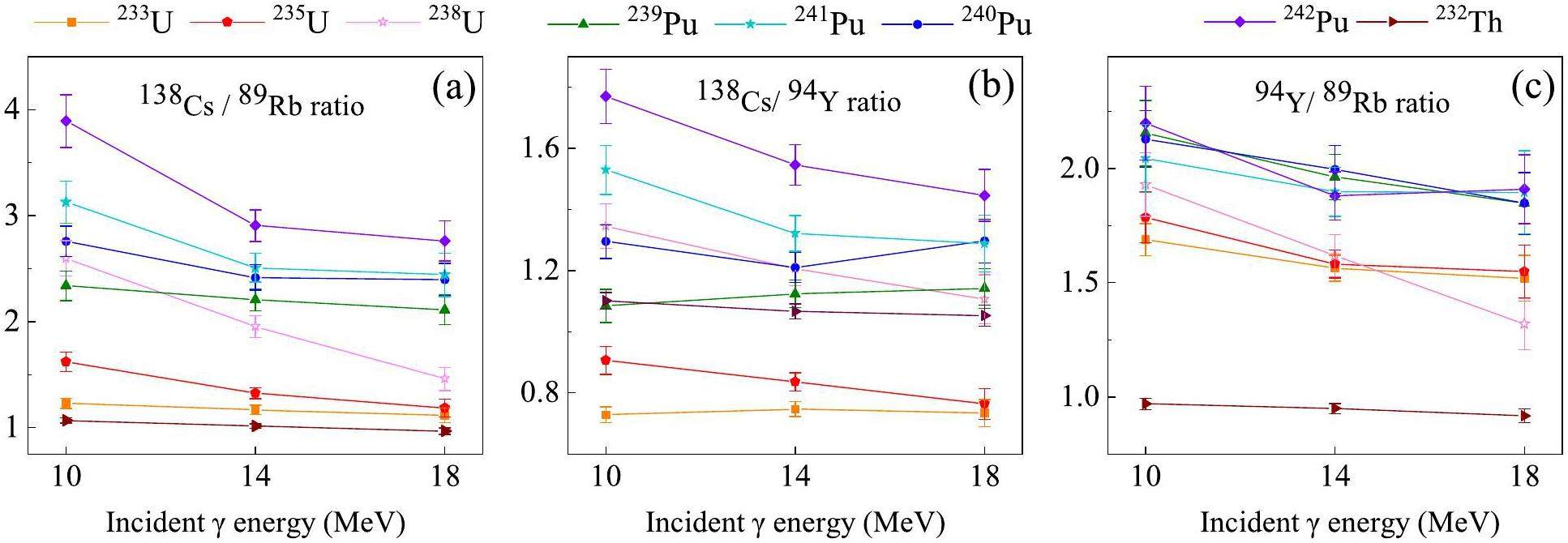

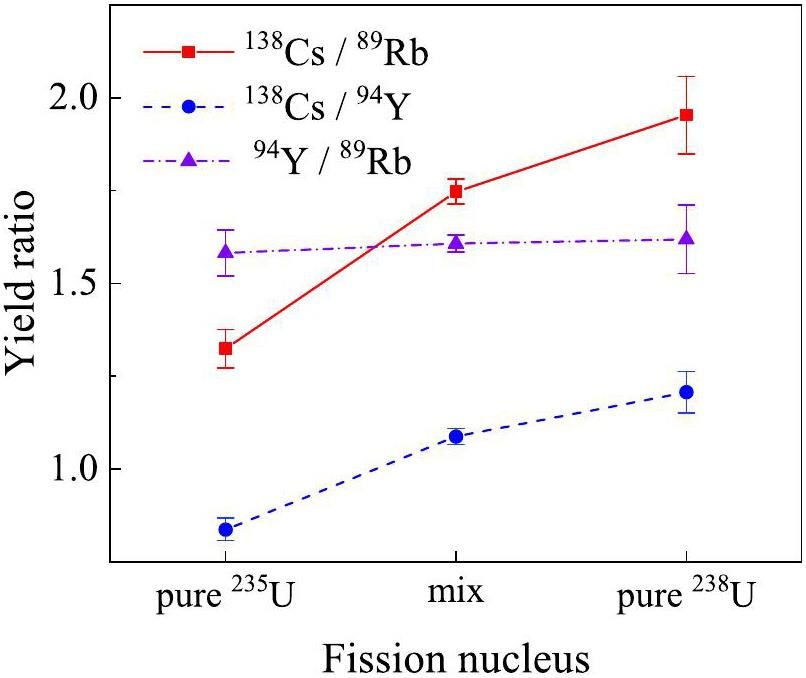

The variation trends of the three pairs of yield ratios at incident photon beam energies of 10 MeV to 18 MeV are illustrated in Fig. 6. The yield ratio is considerably dependent on the fission nucleus. As the energy increases, the yield ratio of 138Cs/89Rb exhibits diminishing differences across various fission nuclei, while those of 138Cs/94Y and 94Y/89Rb demonstrate relatively weak dependence on the incident photon beam energy. Therefore, the method of distinguishing fission nuclei by yield ratio remains effective when γ rays of other energies are incident. When the interrogation source is a bremsstrahlung beam, as illustrated in Fig. 7, the identification method proposed in this paper remains applicable [24]. The yield ratios of the three pairs of nuclides exhibit a good identification effect, and the specific values are consistent with previous results. Because a small proportion of γ rays effectively triggers fission reactions in bremsstrahlung, higher-intensity electrons were used to simulate this process. The yield ratios of the eight nuclides are more distinguishable under beams of higher intensities, leading to improved recognition and higher reliability. Moreover, we discuss the identification under a monoenergetic γ beam of 14 MeV for a mixture of uranium isotopes in nuclear fuel, where 235U and 238U accounts for 20% and 80%, respectively. The yield ratios are presented in Fig. 8. Thus, the yield ratios of 138Cs/89Rb and 138Cs/94Y can identify the mixture as comprising 235U and 238U. Furthermore, the relative abundances of these isotopes depend linearly on the yield ratios. Thus, the detection method remains effective for distinguishing and quantifying isotopes in mixed compositions, thereby extending its applicability to real-world scenarios.

This study provides an identification method for SNM by utilizing the yield ratios of photofission fragments to differentiate among U, Pu, Th, and their isotopes. Photofission was simulated using the self-added photofission module in Geant4, which supplied information on the fission fragments. In the mass and charge yield distribution and decay spectra of fission fragments, the measurable product nuclides with high yields and differences in SNMs were selected. SNMs were identified through the yield ratio of nuclides, in which 239-241Pu require a higher-intensity γ beam to increase the confidence of the results. The yield ratios of the selected product nuclides at different incident photon beam energies showed good stability and discrimination. The identification method was equally effective in the photofission induced by bremsstrahlung. Hence, the proposed identification method is minimally affected by the light source, providing considerable feasibility and reliability for widespread applications of real SNM detection in the future. In addition, our laboratory successfully detected short-lived isotopes with a half-life of 40 ms, thereby providing an experimental and theoretical foundation for the rapid identification of SNMs in future.

Passive neutron detection for interdiction of nuclear material at borders

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 584, 383-400 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.10.026Special nuclear material detection with a mobile multi-detector system

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 663, 55-63 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2011.10.011An enhanced method of neural network algorithm with multi-coupled gamma and neutron characteristic information for identifying plutonium and uranium

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 996,Fissile material isotopic composition by γ-ray spectra

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 449, 500-504 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(99)01472-2Identification of fissile materials from fission product gamma-ray spectra

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 417, 405-412 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(98)00781-5Fission-product gamma-ray line pairs sensitive to fissile material and neutron energy

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 592, 463-471 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2008.04.032Distinguishing fissions of 232Th, 237Np and 238U with beta-delayed gamma-rays

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 304, 11-15 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.03.054Identification of short-lived fission products in delayed gamma-ray spectra for nuclear material signature verifications

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 978,Experimental validation of material discrimination ability of muon scattering tomography at the TUMUTY facility

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 120 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0649-4A novel reconstruction algorithm based on density clustering for cosmic-ray muon scattering inspection

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 53, 2348-2356 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.01.014Material discrimination using cosmic ray muon scattering tomography with an artificial neural network

. Radiat. Detect. Technol. Methods. 6, 254-261 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-022-00319-3Proof-of-principle Study of Explosive Detection Based on Nuclear Resonance Absorption

. Atom. Energ. Sci. Tech. 56, 258-264 (2022). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2022.youxian.015Rapid interrogation of special nuclear materials by combining scattering and transmission nuclear resonance fluorescence spectroscopy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 84 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00914-xIsotope-sensitive imaging of special nuclear materials using computer tomography based on scattering nuclear resonance fluorescence

. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16,Nuclear resonance fluorescence drug inspection

. Sci. Rep. 11, 1306 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80079-6Feasibility study of fissile mass quantification by photofission delayed gamma rays in radioactive waste packages using MCNPX

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 840, 28-35 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.09.047New measurements of cumulative photofission yields of 239Pu, 235U and 238U with a 17.5 MeV bremsstrahlung photon beam and progress toward actinide differentiation

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 1040,Identification and differentiation of actinides inside nuclear waste packages by measurement of delayed gammas

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 57, 2862-2871 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2010.2064334Identification of actinides inside nuclear waste packages by measurement of fission delayed gammas

. IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Records 2, 909-913 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1109/NSSMIC.2006.355994Isotopic identification of photofissed nuclear materials in stainless steel containers using delayed amma-rays

. Probl. Atom. Sci. Tech. 5, 103-109 (2022). https://doi.org/10.46813/2022-141-103Novel algorithm for detection and identification of radioactive materials in an urban environment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 154 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01304-1Radionuclide identification method for NaI low-count gamma-ray spectra using artificial neural network

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 54, 269-274 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.07.025Analysis of fissionable material using delayed gamma rays from photofission

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 24–25, 503-505 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-583X(87)90695-1Measurements of short-lived isomers from photofission as a method of active interrogation for special nuclear materials

. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15,The SLEGS beamline of SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01469-3Commissioning of laser electron gamma beamline SLEGS at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 87 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01076-0Generation of ~400 pC electron bunches in laser wakefield acceleration utilizing a structured plasma density profile

. Phys. Plasmas 30,Ultra-short lifetime isomer studies from photonuclear reactions using laser driven ultra-intense γ-ray

. (2023). arxiv: 2402.15187197Au(γ, xn; x = 1 ∼ 7) reaction measurements using laser-driven ultra-bright ultra-fast bremsstrahlung γ-ray

. (2023). arxiv: 2209.13947New measurements of 92Mo(γ, n) and (γ, 3n) reactions using laser-driven bremsstrahlung γ-ray

. Front. Phys. 11,Effective extraction of photoneutron cross section distribution using gamma activation and reaction yield ratio method

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 170 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01330-zGeneration of medical isotopes 47Sc, 67Cu through laser induced (γ, p) reaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 206 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01550-xCross section measurements of 27Al(γ, x)24Na reaction as monitors for laser-driven bremsstrahlung γ-ray

. Nucl. Phys. A 1043,Thick-target yield of 17.6 MeV γ ray from the resonant reaction 7Li(p, γ)8Be at Ep = 441 keV

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 529, 56-60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2022.08.005New measurement of thick target yield for narrow resonance at Ex=9.17 MeV in the 13C(p,γ)14N reaction

. Chin. Phys. B 28,Geant4—a simulation toolkit

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. B 506, 3 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8Geant4 development for actinides photofission simulation

. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 1062,A general framework for describing photofission observables of actinides at an average excitation energy below 30 MeV

. Chinese Phys. C 46,Systematics of fragment mass yields from fission of actinide nuclei induced by the 5–200 MeV protons and neutrons

. Ann. Nucl. Energ. 35, 328-245 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2007.06.002J.-Ch. TENDL: Complete Nuclear Data Library for Innovative Nuclear Science and Technology

. Nucl. data sheets 155, 1-55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2019.01.002Xue-Qing Yan is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.