Introduction

Terahertz (THz) radiation, which is an electromagnetic wave within the frequency range of

Various methods exist for generating THz radiation depending on the specific implementation and application [3, 12, 13]. One of the most promising THz sources is accelerator-based coherent THz radiation from relativistic electron bunches [13]. With an electron-bunch length of hundreds of femtoseconds, the radiation emitted from all electrons in the bunch is coherently added and lies within the THz spectral range. The radiation intensity is high and proportional to the square of the number of electrons in the bunch. A convenient and effective method for generating coherent THz radiation is transition radiation (TR), which has been developed by several laboratories [14-18]. The short electron bunches provide a broadband THz-TR spectrum with a higher radiation intensity than conventional synchrotron and black-body radiation sources. This unique characteristic enables the use of THz TR as a THz-spectroscopy source, as reported in [19].

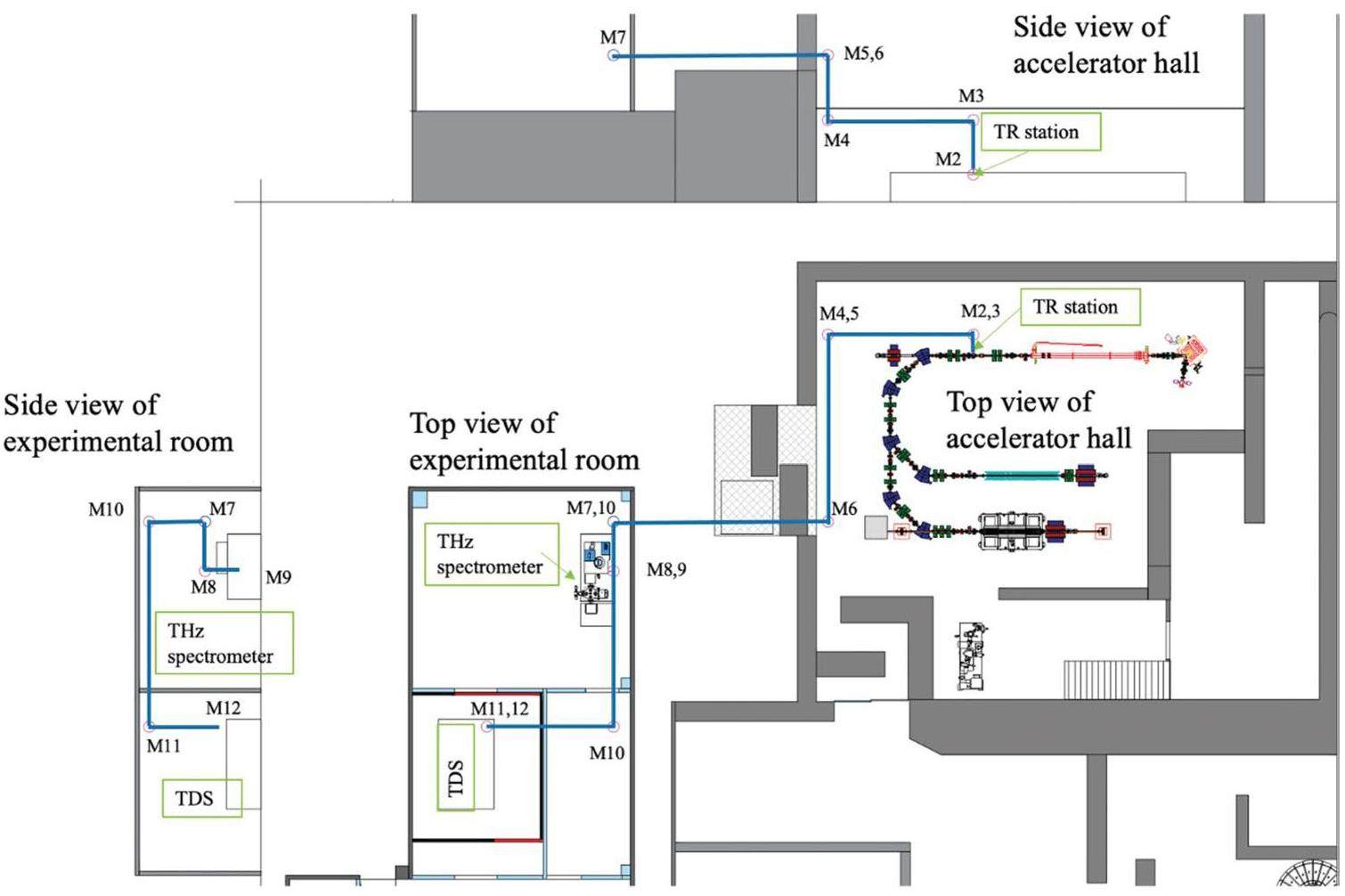

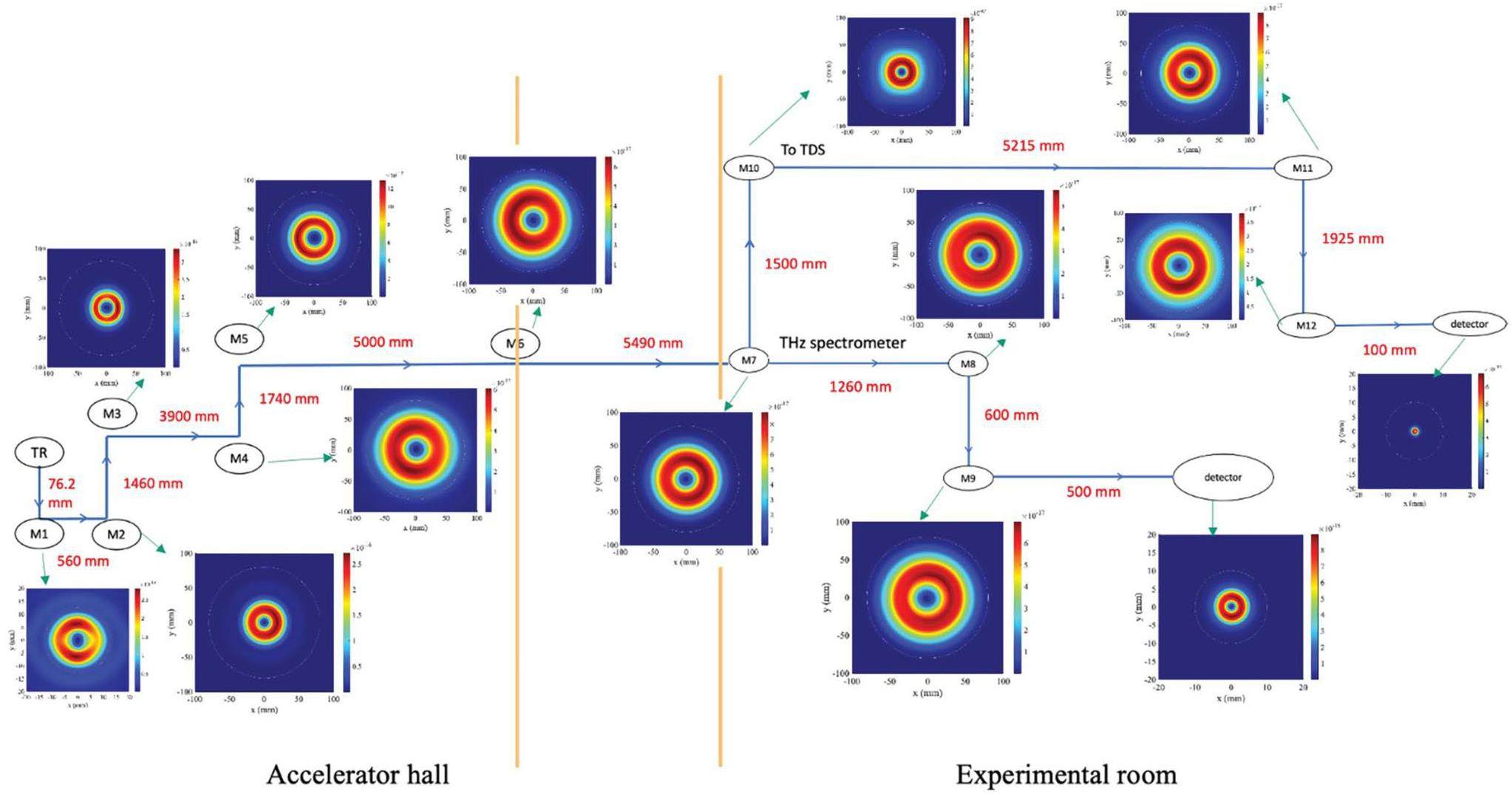

At the PBP-CMU Electron Linac Laboratory (PCELL), we successfully generated a coherent THz TR using an accelerator-based radiation source, which operated with an average electron-beam kinetic energy in the range of 8–12 MeV. Details regarding the radiation spectrum with an electron-beam energy as low as 8 MeV were reported and discussed in [20], and radiation generated in the 10–12 MeV range was employed to measure electron-bunch lengths as short as 180 fs [21]. Furthermore, THz TR derived from an 8-MeV electron beam has been used effectively for THz imaging, as reported in [22, 23]. With the recent upgrade of radio-frequency (RF) power systems, the energy of the electron beam will be boosted to 22 MeV, leading to the production of THz TR at this new energy level. As indicated by [14], the characteristics of the electron beam significantly influence TR properties. Thus, in this study, THz TR properties are investigated based on the new electron-beam characteristics. The THz TR generated in this new electron-beam energy range will be used as a source for THz spectroscopy and THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) at our facility. Several crucial aspects must be addressed to facilitate the design and development of spectroscopic systems. These include the generation of THz TR, characterization of TR properties, and transportation of TR from the accelerator hall to the experimental room. Figure 1 illustrates the layout of the accelerator hall, experimental room, and radiation transportation line and provides a visual overview of the configuration of the entire system.

This study focuses on the evaluation of coherent THz TR derived from short electron bunches with energies up to 22 MeV. To achieve this, electron-beam dynamics simulations are performed using the ASTRA code. The simulations are aimed at achieving electron beams with short bunch lengths and small transverse beam sizes, specifically at the TR station. The radiation properties, including the radiation spectrum, angular distribution (spatial distribution), and radiation polarization, are calculated. Furthermore, TR serves as a valuable tool for measuring the electron-bunch length using a Michelson interferometer. The properties of TR must be measured both before transportation and at the final experimental station to characterize its behavior. Subsequently, the TR spectrum is evaluated by considering factors such as the electron-beam distribution, radiator size, and Michelson-interferometer beam splitter. These considerations ensure an accurate assessment of the TR spectrum and its associated features. Finally, the THz-transportation design is presented as a guideline for the construction of a radiation-transport line.

Generation of coherent transition radiation from short electron bunches

At the PCELL facility, a train of electron bunches is generated from a thermionic cathode RF electron gun with a maximum kinetic energy of approximately 2–2.5 MeV. Subsequently, the electron bunches undergo further acceleration by a traveling-wave linac, reaching a kinetic energy of approximately 8–22 MeV. To achieve a bunch length on the femtosecond scale at the experimental station, the electron bunches are compressed using an alpha magnet and velocity bunching during linac acceleration. These short electron bunches are utilized to generate THz TR at an experimental station downstream of the linac section.

Generation and detection of transition radiation

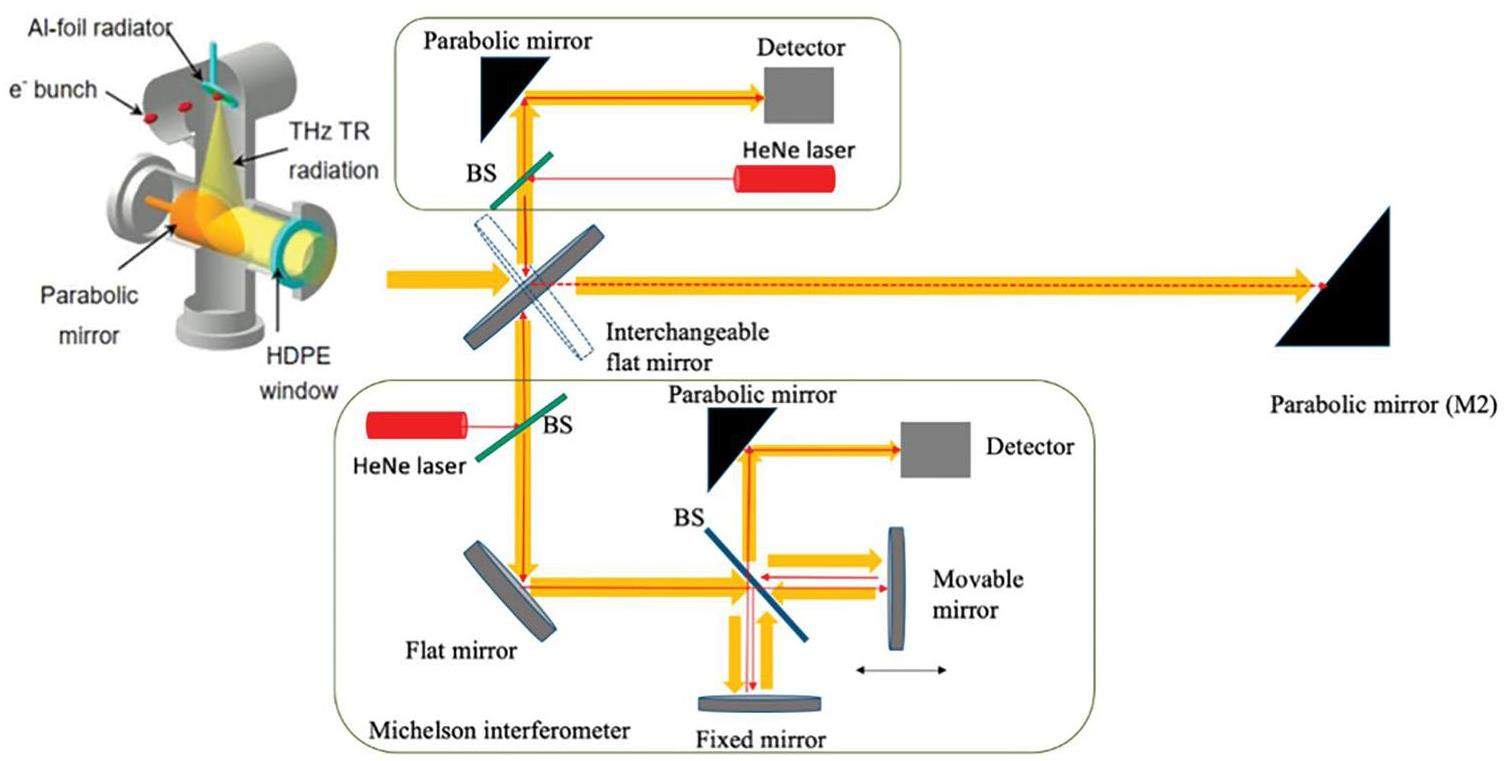

At the experimental station, an aluminum (Al) foil serves as the radiator. By tilting the radiator 45° relative to the electron-beam direction, backward transition radiation is emitted at the radiator surface and subsequently collimated by a parabolic mirror. The collimated radiation passes through a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) window, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The radiation then enters the measuring system for energy, power, transverse-profile, polarization, and spectral-range measurements. Because TR is directly related to the electron-bunch length, it is also employed to measure this parameter.

The Al-foil radiator has a thickness of 25 μm and diameter of 24 mm. THz radiation is generated at the interface between the vacuum and Al foil. In the THz regime, the relative dielectric constant of Al is approximately 1 × 105, which is significantly higher than that of vacuum (

Consequently, the radiation enters the measuring system and is divided into two parts using a flipable flat mirror. The first part involves the measurement of the radiation profile, energy, and power. The radiation profile is captured using a Pyrocam III camera featuring 124×124 sensor arrays with active dimensions of 1.24 cm ×1.24 cm. A parabolic mirror is employed to collimate the radiation onto the detector, with a diameter of 50.8 mm and focal length of 101.6 mm. Furthermore, the setup allows the measurement of radiation polarization. To achieve this, a wire-grid polarizer (Graseby-Space Model IGP223) with a 4-μm wire-grid photo-lithed onto a polyethylene substrate is used. By placing the polarizer in front of the Pyrocam III and rotating it, the polarization in various directions can be measured. The second part involves measuring the radiation spectrum and electron-bunch length using a Michelson interferometer. The details of the Michelson interferometer are described in Sect. 3.4. Following the characterization, the radiation is guided to the experimental room by another parabolic mirror (M2).

Optimization of electron-beam properties

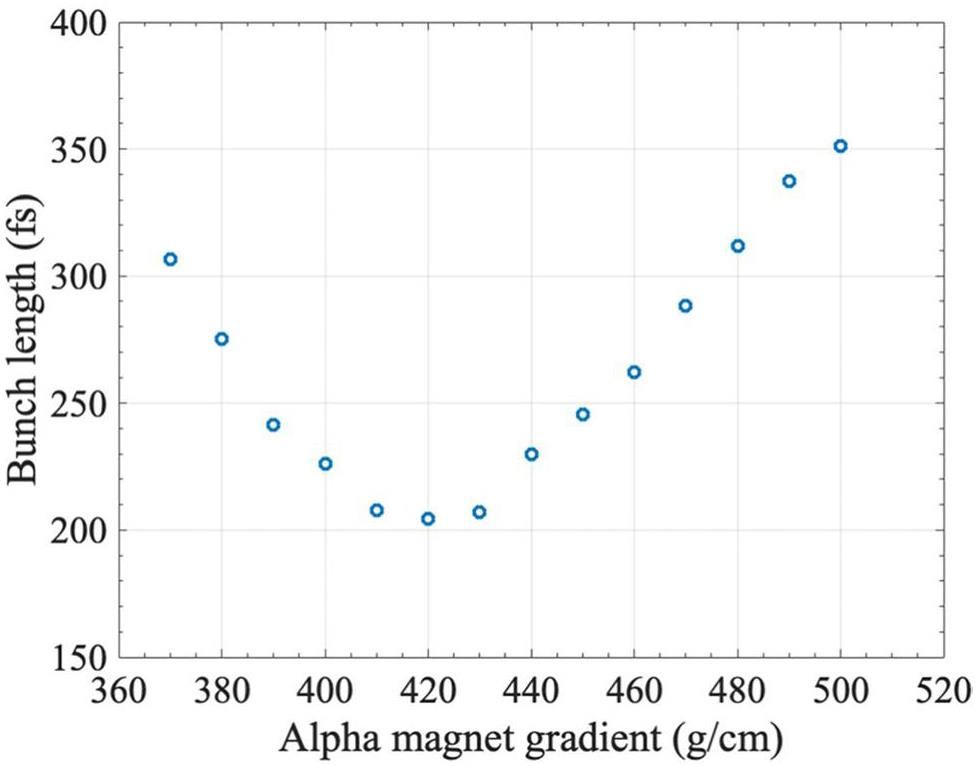

To optimize the electron-beam properties, A Space Charge Tracking Algorithm (ASTRA) software [24] was used to simulate the electron-beam dynamics throughout the accelerator system, starting from the RF gun to the TR experimental station. In our study, the space-charge effect was included in the simulation. We generated four million macroparticles at the cathode of the RF gun to initiate the simulation. These macroparticles were then separated into groups using a 2856 MHz RF wave, forming an electron bunch. Our simulation specifically focused on studying a single electron bunch, assuming that other electron bunches had similar characteristics. The electron bunch at the gun exit had an average energy of 1.92 MeV and a bunch charge of 160 pC. These electrons then traveled to the alpha magnet, which functioned as a magnetic bunch compressor. The beam had a bunch length of 69.2 ps at the entrance of the alpha magnet. Within the magnet, higher-energy electrons traveled a longer path than lower-energy electrons. Consequently, the lower-energy electrons eventually caught up with the higher-energy electrons at the designated position, which, in this case, was the experimental station. This process resulted in the compression of the electron bunch, leading to a shorter electron-bunch length. The alpha-magnet gradient was varied to obtain the shortest electron-bunch length at the experimental station. Additionally, the energy slit inside the alpha magnet was used to filter out low-energy electrons. This filtering process optimized the energy spread of the beam and enabled selective control of the bunch charge.

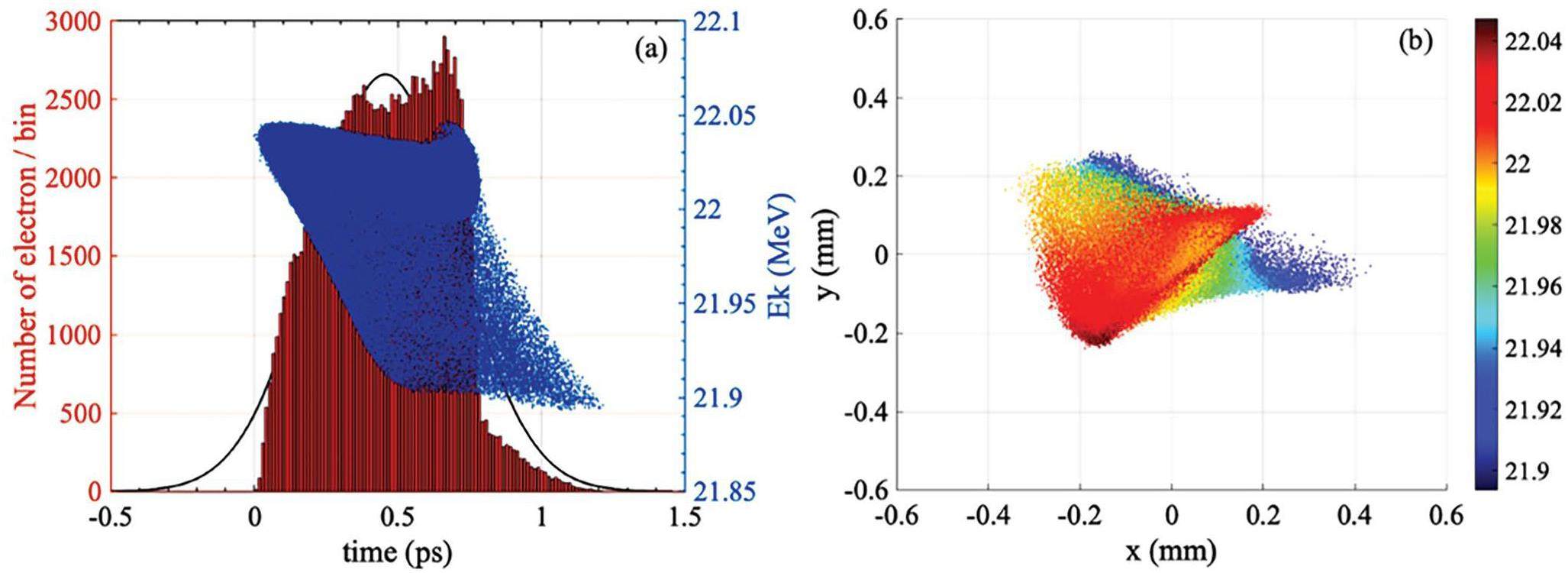

After exiting the alpha magnet, the beam traversed the three-meter linac and gained energy of up to 22 MeV. Subsequently, the size of the transverse electron beam at the TR station was measured using two quadrupole magnets. The performance of the alpha magnet was evaluated by varying its gradients, and the results showed that a gradient of 420 g/cm yielded the shortest bunch length of 200 fs at the TR station for an electron-beam kinetic energy of 22 MeV, as shown in Fig. 3. The simulated longitudinal and transverse electron-beam distributions at the TR station are shown in Fig. 4. The histogram provides a representation of the longitudinal shape of the electron beam and exhibits a root-mean square (RMS) value of 352 fs. To further characterize the beam profile, a Gaussian fit was applied to the histogram, yielding a standard deviation that matched the RMS value obtained from the histogram. The electron-beam parameters obtained from the simulations are listed in Table 1.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Beam kinetic energy (MeV) | 22 |

| Horizontal beam size (mm) | 0.11 |

| Vertical beam size (mm) | 0.09 |

| Bunch length (fs) | 352 (105.5 μm) |

| Bunch charge (pC) | 62.5 |

| Macropulse repetition rate (Hz) | 10 |

| Number of bunches | 2856 bunches per macropulse |

Transition-Radiation Characterizations

Transition radiation is generated when a charged particle passes through the interface between two media with different dielectric constants, such as from a vacuum to a perfect conductor. Radiation is emitted when a charged particle suddenly changes its velocity at the interface [1, 25, 26]. Using the measurement setup shown in Fig. 2, the radiation properties are characterized before being transported to the experimental room.

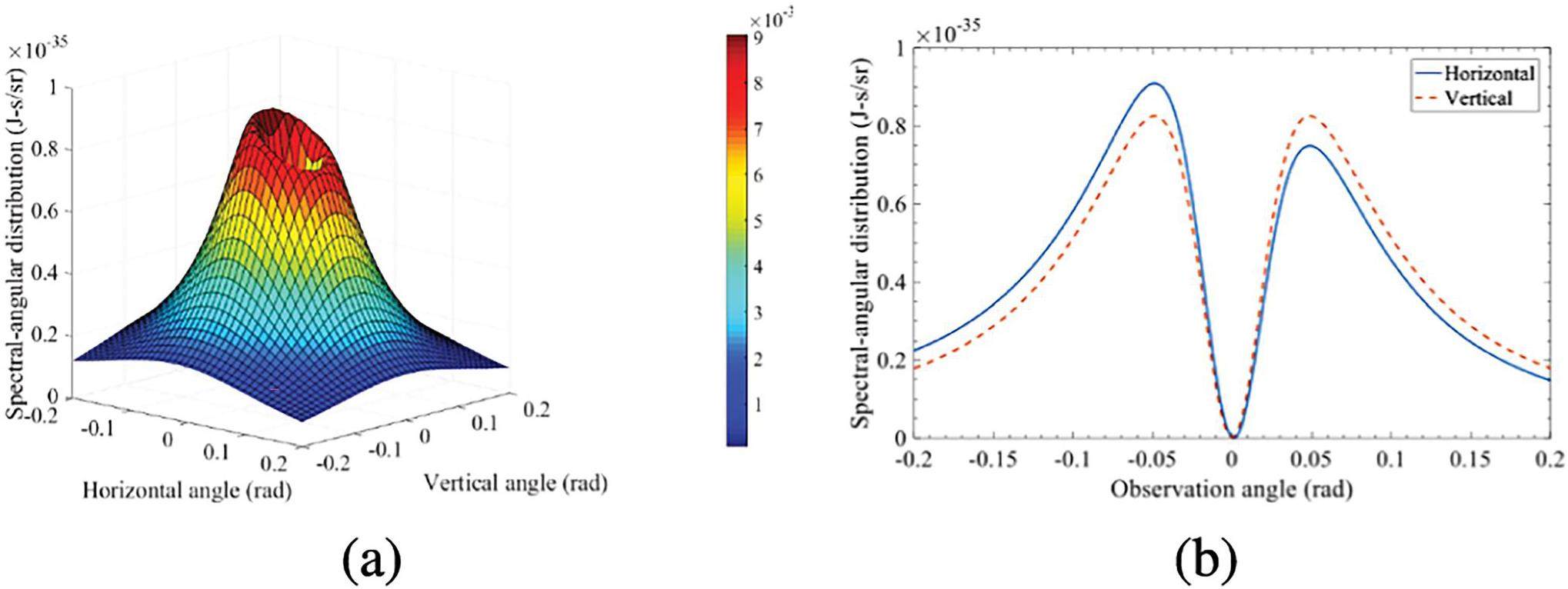

Angular distribution and polarization

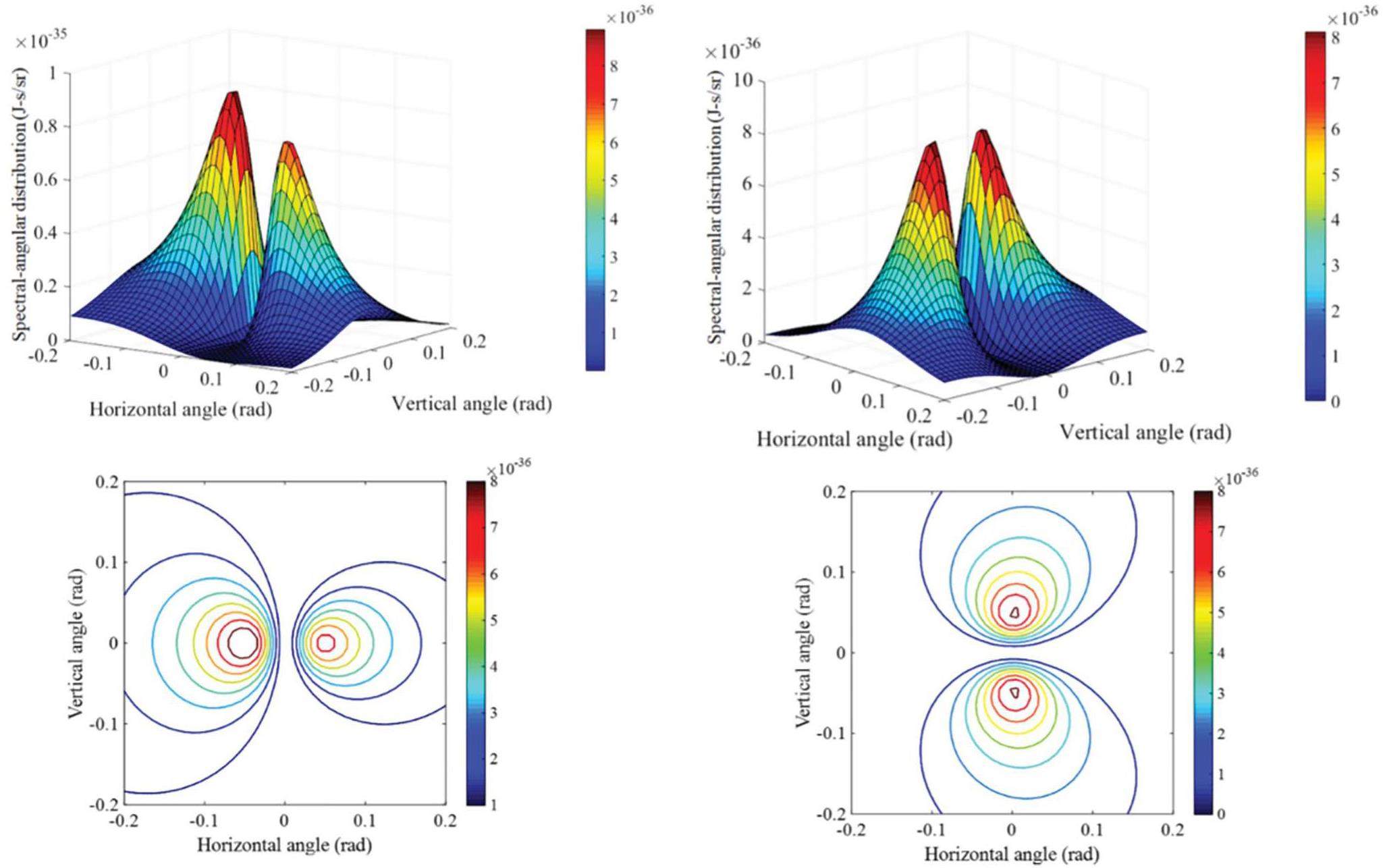

In our experimental setup, the incidence angle of the electron beam is 45° (ψ = 45°) with respect to the direction of travel. Backward TR radiation is then emitted perpendicularly. This radiation comprises two polarization components: parallel polarization, in which the electric field lies in the radiation plane, and perpendicular polarization, in which the electric field is perpendicular to the radiation plane. The spectral angular distribution of the TR generated from an electron with a kinetic energy of 22 MeV and its cross-section are shown in Fig. 5. The results indicate that no radiation is emitted at the center of the radiation distribution. The distribution reveals asymmetry in the horizontal angle. This asymmetry is clearly depicted in Fig. 5(b), which illustrates the cross sections of the spectral-angular distribution in the horizontal and vertical directions. The observed asymmetry in the distribution arises from the oblique incidence of electrons in the xz-plane. The radiation emitted near the interface exhibits a higher intensity than that emitted near the z-axis. The transition radiation exhibits radial polarization, as shown in Fig. 6. The polarization is asymmetric in the horizontal direction and symmetric in the vertical direction.

Effects of electron-bunch distribution

The radiation emitted by several electrons can be considered by adding all the radiation fields emitted by each electron in the bunch. The radiation intensity of each electron,

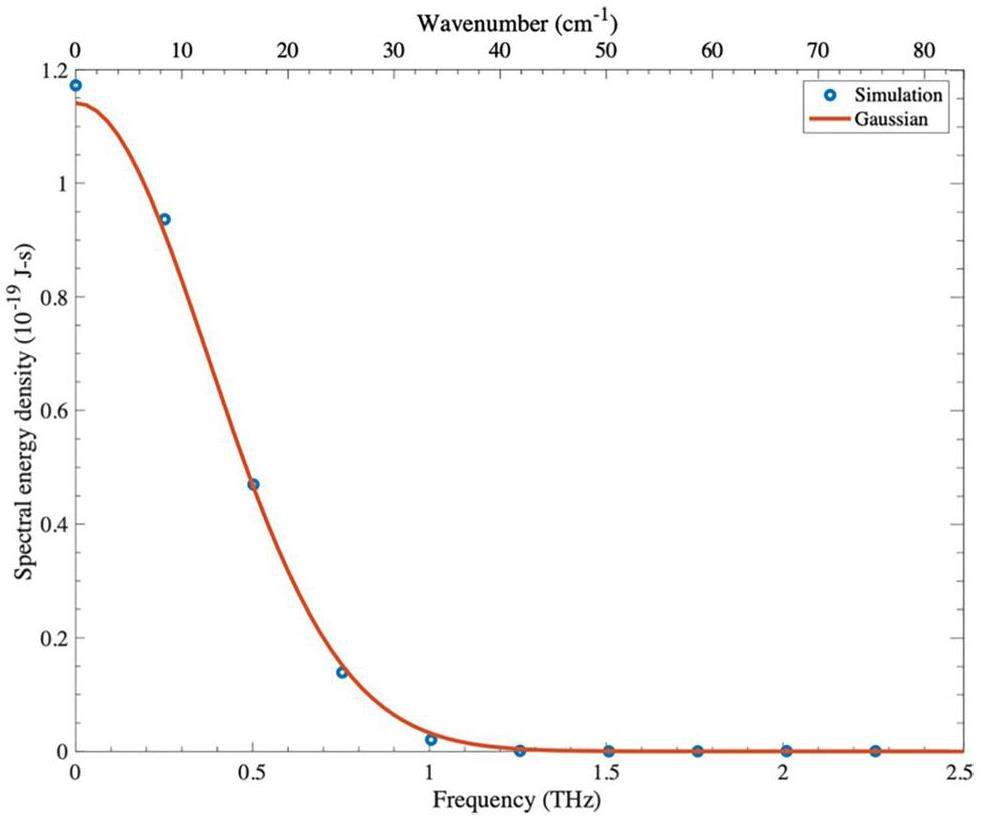

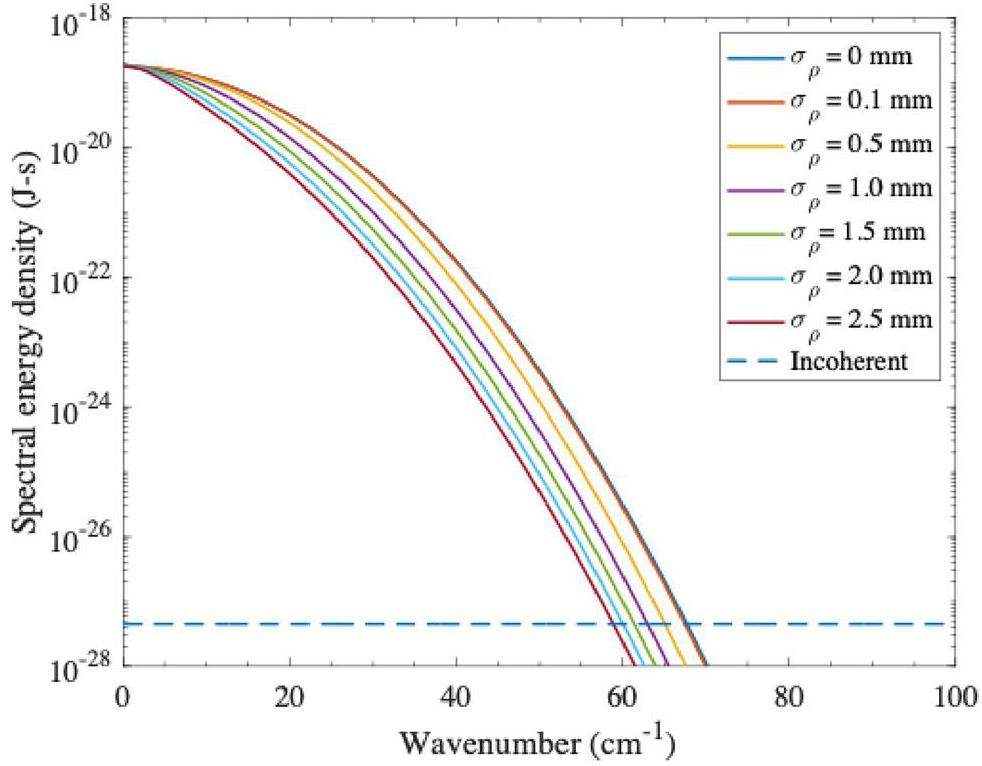

The influence of bunch distribution on the emitted radiation is investigated. To illustrate this phenomenon, a histogram representing the longitudinal distribution of the electron bunch is shown in Fig. 4(a), obtained from electron-beam-dynamics simulation. The coherent TR spectrum resulting from this bunch was analyzed and compared with a Gaussian distribution. By performing a Fourier transform on the longitudinal distribution of the simulated electron bunch, the resulting radiation spectrum was compared with that of a Gaussian bunch with a length of 352 fs (represented by its standard deviation, σz). The radiation spectra are shown in Fig. 7.

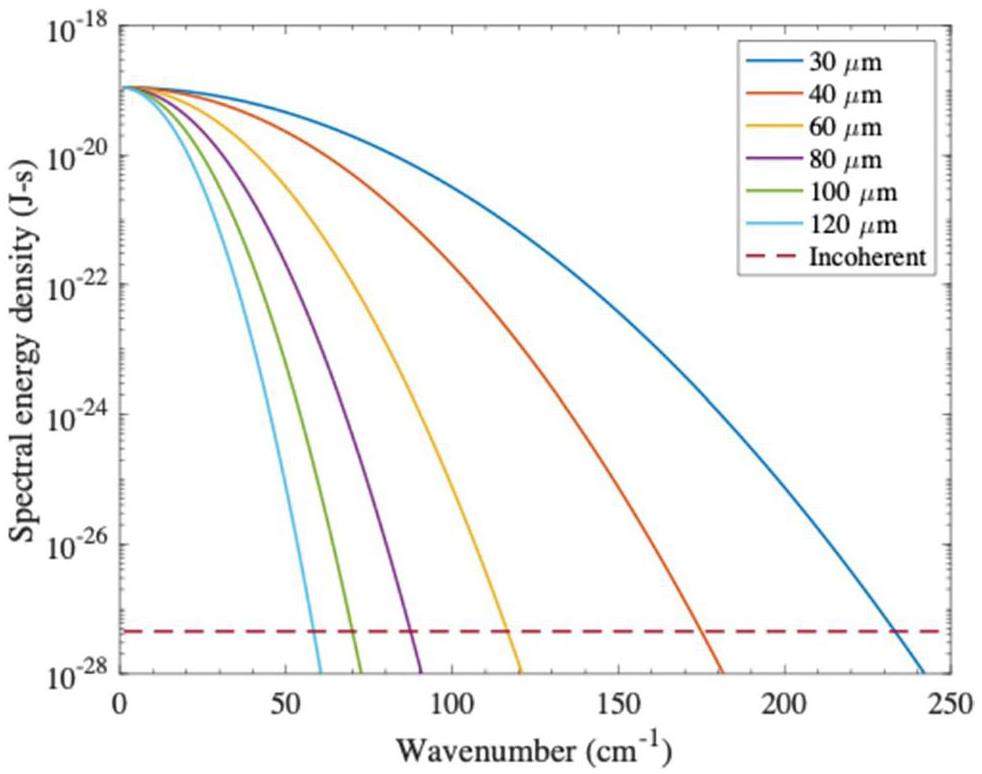

Based on the obtained results, the radiation spectrum of the simulated electron bunch aligns well with that of the Gaussian bunch. The spectral range covers up to approximately 2 THz or a wavenumber of 70 cm-1 for both the distributions. For simplicity, we assume a Gaussian spectrum for further investigation to explore the additional factors affecting the radiation spectrum. In this section, we focus on a scenario in which the electron beam has a kinetic energy of 22 MeV and bunch charge of 62.5 pC, as obtained from the simulations in Sect. 2.2. The bunch distribution is assumed to be Gaussian with an RMS width of 352 fs. The calculated coherent TR spectra for a 22-MeV electron beam at different bunch lengths are illustrated in Fig. 8. The effect of the transverse beam size was excluded.

The plots in Fig. 8 clearly show that a shorter electron-bunch length corresponds to a broader radiation spectrum. In our specific case, the simulated electron-bunch length (σz) is estimated at 105.5 μm (352 fs), which results in an emitted TR of up to 70 cm-1. Coherent radiation dominates when the electron-bunch length is equal to or shorter than the wavelength of the emitted radiation. Consequently, an increase in the electron-bunch length leads to a reduction in the coherent radiation at shorter wavelengths or higher wavenumbers, resulting in a narrower spectral range. However, by employing a shorter bunch length of 40 μm, we achieve a significantly broader spectral range extending up to 180 cm-1.

In a realistic scenario, the electron bunches also have a transverse size that contributes to the form factor [21, 27]. The coherent radiation is suppressed when the beam size increases. In this case, the transverse bunch distribution reduces the form factor for a particular radiation wavelength. As a case study, we considered an electron bunch with a Gaussian distribution in both the transverse and longitudinal directions with a form factor that can be expressed as

For an electron beam with a kinetic energy of 22 MeV, the radiation spectra, including the effect of the transverse size, are depicted in Fig. 9. Notably, these spectra were calculated within an acceptance angle of ±165 mrad (the angle at which the radiation is collected by the first parabolic mirror in our experimental setup) and for a fixed electron-bunch length of 105.5 μm. The effective transverse beam size, defined as

Effect of finite radiator size

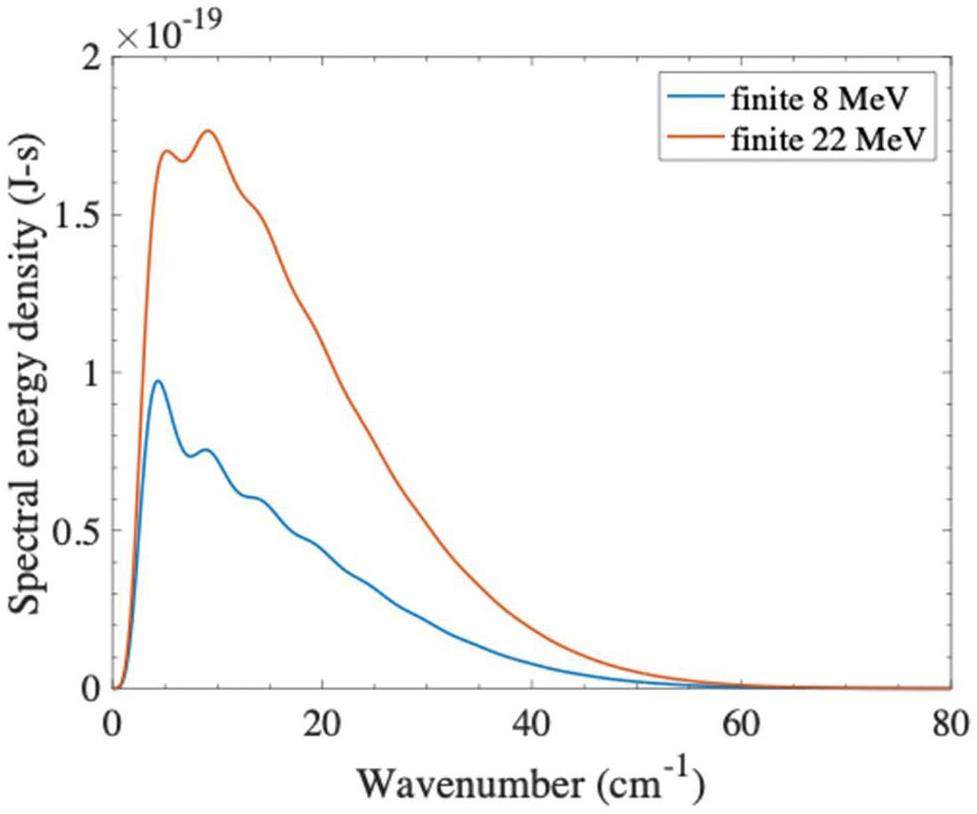

In previous sections, the radiator was assumed to be infinitely large. However, the influence of radiator size must be considered, as highlighted by Castellano et al. [28]. This effect becomes significant when the factor γλ exceeds the transverse dimension of the radiator, where γ is the Lorentz factor and λ is the radiation wavelength. To comprehensively analyze the total radiation spectrum, integration was performed over an acceptance angle of ±0.165 rad. A comparison between the electron bunches with kinetic energies of 8 and 22 MeV is presented in Fig. 10 by considering a radiator radius of 12 mm.

The results in Fig. 10 indicate that some parts of the low frequencies are suppressed owing to the effect of the size of the radiator. For an electron beam with a kinetic energy of 22 MeV, the radiation spectrum is suppressed at a frequency lower than 0.3 THz (10 cm-1). The same result was obtained for an electron kinetic energy of 8 MeV. This suppression is consistent with the experimental findings reported in [20]. More importantly, this frequency is the lower limit for designing radiation-transportation systems.

Effect of mirror in Michelson interferometer

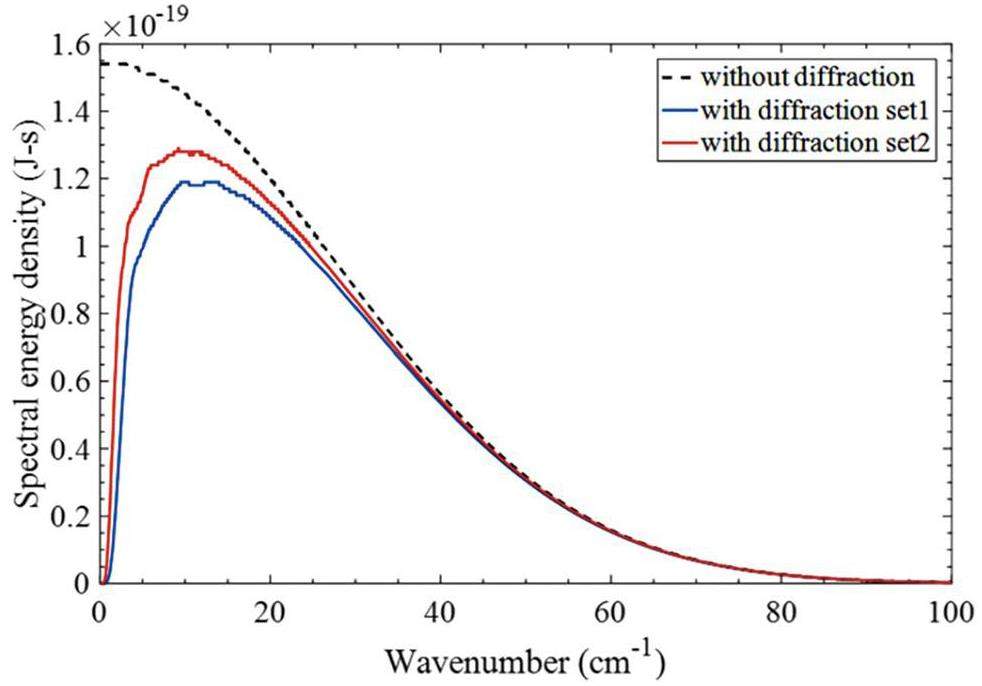

The Michelson interferometer serves as a tool for measuring both the radiation spectrum and electron-bunch length. However, when using an interferometer, the diffraction effect caused by a finite aperture during radiation propagation must be considered. Subsequently, optimizing the size of the mirrors used in the interferometer is essential to achieve the best performance of the system. Fraunhofer diffraction is employed to determine the energy transmission of the radiation passing through the Michelson interferometer, assuming circular apertures [29].

As depicted in Fig. 2, the radiation emitted from the first parabolic mirror (with a diameter of 25.4 mm) travels through the HDPE window before entering the Michelson interferometer. Subsequently, the radiation impinges on the flat mirrors with a diameter of 50.8 mm and is then reflected back to the beam splitter before being collected by another parabolic mirror onto the detector. The HDPE window is positioned at a distance of 76.2 mm away from the first parabolic mirror. A flat mirror M1 is situated inside the Michelson interferometer at a distance of 367.3 mm from the HDPE window. Moreover, the distance between the flat mirror M1 and parabolic mirror P2 is 215.9 mm.

The energy transmissions calculated based on the aforementioned setup illustrated in Fig. 11 indicates that radiation-energy density is suppressed at low frequencies when the effect of the mirrors in the Michelson interferometer is considered. In this figure, the diameters of the flat and parabolic mirrors are 50.8 mm and 25.4 mm for diffraction set 1 and 76.2 mm and 50.8 mm for diffraction set 2, respectively. The figure shows that doubling the size of the mirrors does not significantly decrease the energy density.

Effects of beam splitters

In a Michelson interferometer, a beam splitter divides the radiation into two paths, which are subsequently recombined to form an interferogram pattern. Conventionally, the reflectance and transmittance of a beam splitter were assumed to be constant across all frequencies. However, in the THz region, an appropriate beam splitter exhibits variations in reflectance and transmittance owing to multiple reflections within the beam-splitter materials [30]. This phenomenon can be predicted as follows. The total amplitudes of the reflection (R) and transmission (T) coefficients are defined as follows (Hecht, 2002):

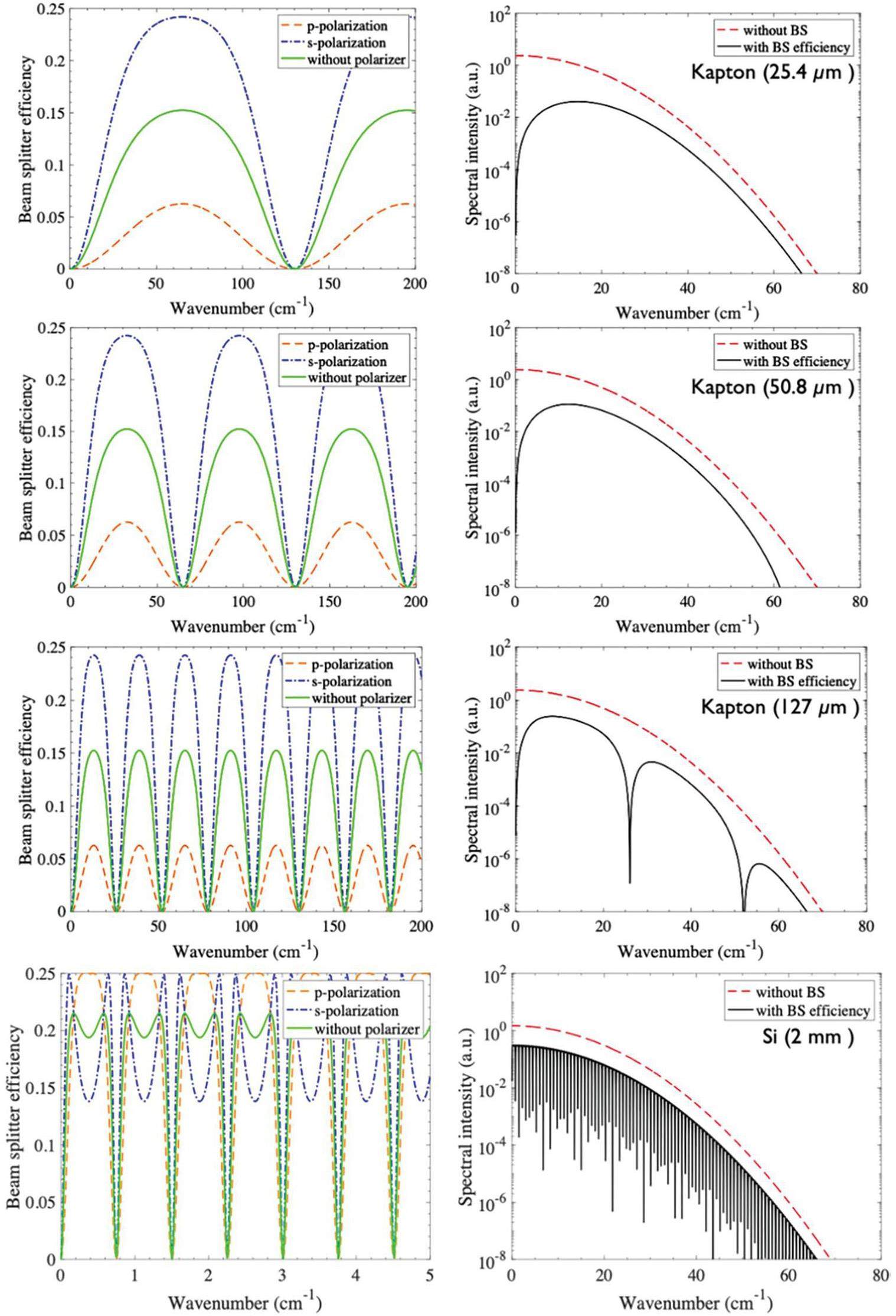

Beam splitter and radiation spectrum

The beam-splitter efficiencies of Kapton at various thicknesses are shown in Fig. 12 (left) and the corresponding effects on the radiation spectra are shown in Fig. 12 (right). The efficiency fluctuates across the frequency range, reaching zero at specific frequencies at which the interfering radiation from both surfaces of the beam splitter becomes destructive. For a 25.4-μm Kapton beam splitter (with

The efficiency of the Si beam splitter with a thickness of 2 mm is presented in Fig. 12. The calculated results indicate that the Si beam splitter offers higher efficiency for both p-polarized and s-polarized radiation, reaching a maximum value of 0.25 and an average value of approximately 0.21. Additionally, the Si beam splitter demonstrates good coverage at low frequencies, particularly below 0.5 cm-1 for a 2-mm thickness. However, because of the higher refractive index of Si and thickness of the beam splitter, zero efficiency is observed at closely spaced frequencies, as shown in Fig. 12. For the 2-mm Si beam splitter, the frequency spacing between zeros is at 0.75 cm-1, resulting in numerous sharp dips in the radiation spectrum. These are particularly noticeable when the spectral resolution is lower than the zero-frequency spacing of the Si beam splitter. In such cases, the radiation spectra contain an average beam-splitter response.

Following the investigation, the results showed that the Kapton beam splitter with a thickness of 25.4 μm is highly suitable for accurately measuring the radiation spectrum. This conclusion is based on the significant separation observed between the dips in the beam splitter. This considerable separation indicates that the Kapton beam splitter allows for more precise measurement of the radiation spectrum using a Michelson interferometer.

Beam splitter and bunch-length measurement

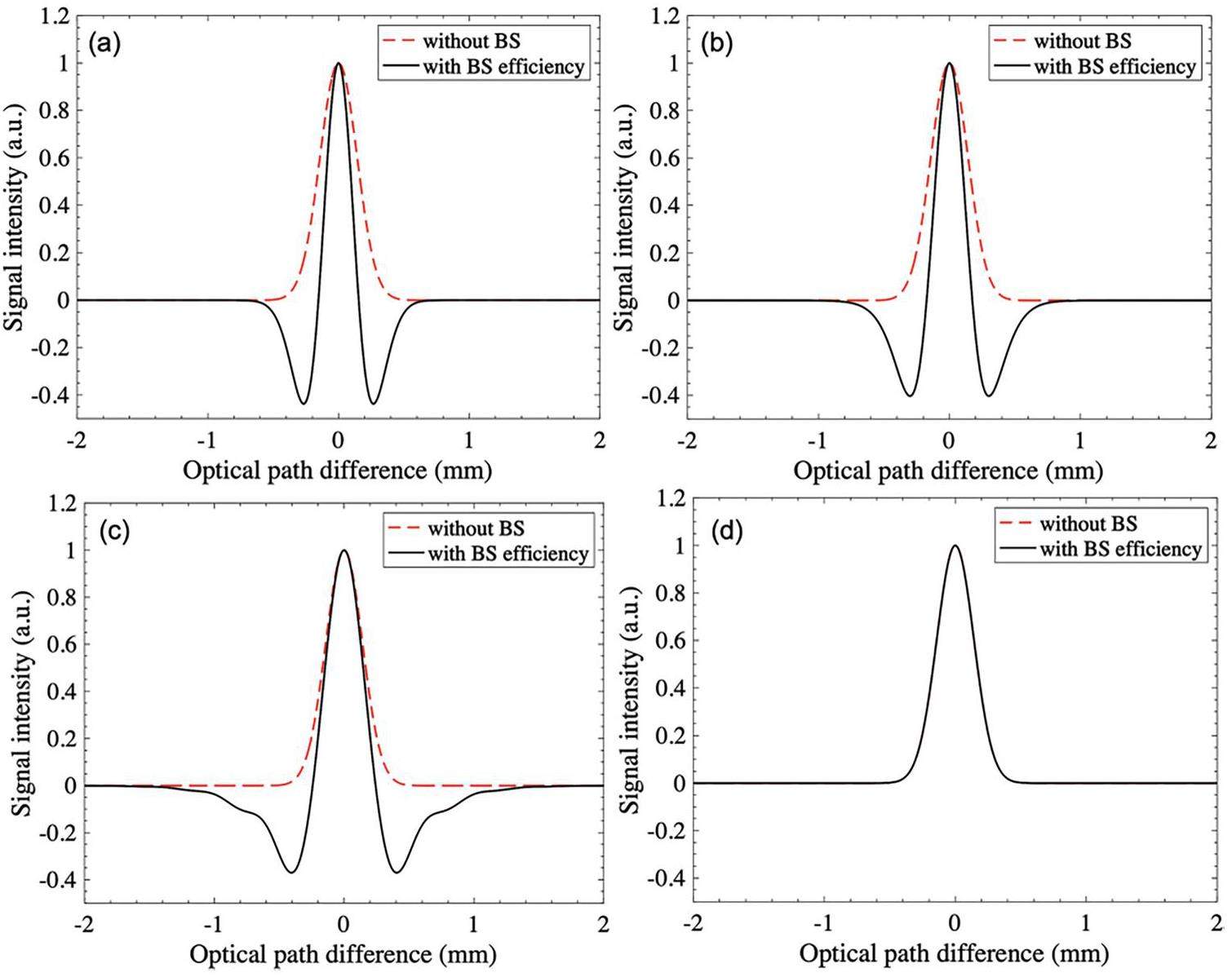

As mentioned previously, TR can be utilized to measure the electron-bunch length through autocorrelation using a Michelson interferometer. The interferogram obtained directly from the Michelson interferometer reflects the electron bunch-length characteristics. However, the effect of beam-splitter efficiency on the accuracy of these measurements must be considered. The efficiency of the beam splitter in the interferometer can introduce potential errors during the measurement process. According to the results presented in the previous section, the width of the interferogram cannot be directly used to determine the electron-bunch length, owing to the presence of beam-splitter interference. The intensity-suppression effect of the beam splitter leads to negative valleys in the interferogram, resulting in an artificially smaller interferogram width, as depicted in Fig. 13(a)–(c).

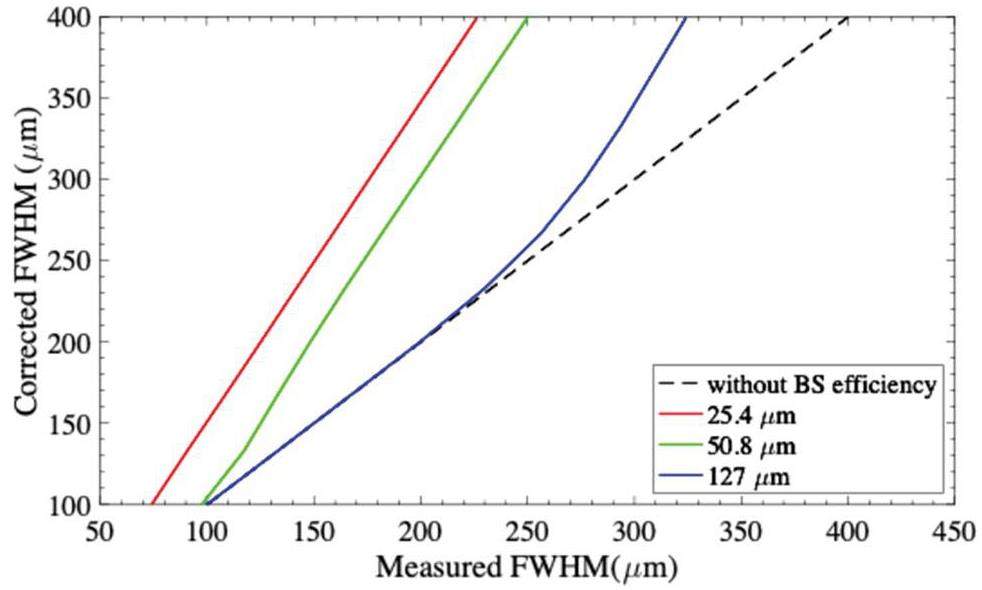

To investigate this effect further, the simulated interferogram is compared with a reference Gaussian interferogram. Simulated interferograms are obtained by applying the inverse Fourier transform to the radiation spectra. The reference interferogram is constructed using a Gaussian bunch distribution with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 334 μm, corresponding to an electron-bunch length of 105.5 μm.

By increasing the thickness of the beam splitter, the negative valleys move further away from the center burst (central positive intensity) of the interferogram. As a result, measuring the bunch length with a Kapton beam splitter requires a correction of the FWHM values. The FWHM of the measured interferograms corrected with the beam-splitter efficiency are shown in Fig. 14. When the beam-splitter thickness is equal to or exceeds twice the electron-bunch length, the measured FWHM of the interferogram accurately reflects the actual bunch length. The SUNSHINE facility also conducted a study on the impact of a beam splitter within the Michelson interferometer, with the aim of measuring the bunch length of 26-MeV electrons. This investigation is documented in [32]. The experimental results exhibit a trend similar to that observed in our calculations. In this study, a Kapton beam splitter with a thickness of 127 μm yields a measured bunch length that is close to the real value for a bunch length of 105.5 μm (FWHM = 334 μm). In the case of the Si beam splitter, the interferograms exhibit negative valleys far from the center burst. Because these negative valleys do not alter the appearance of the center burst, the width of the interferogram can be used to extract the bunch-length value directly. Regardless of the light absorption by the beam splitter, we can conclude that thick beam splitters are more suitable for bunch-length measurements than thin beams, as discussed above.

Radiation Transportation

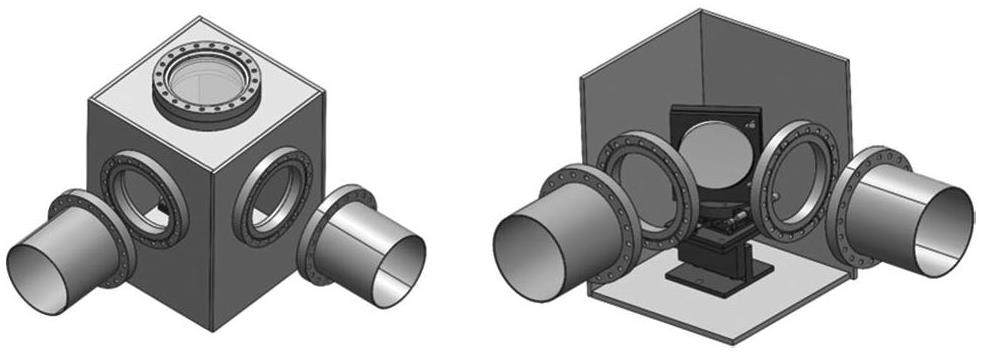

Our laboratory is currently developing THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) and a THz spectrometer that utilizes coherent TR as a source. However, the TR station is located inside the accelerator hall. Thus, access to the TR station is restricted during accelerator operations owing to radiation-safety protocols. Consequently, a transport line for the TR from the accelerator hall to the experimental room, spanning a total distance of approximately 27 m, is required. The main constraints for TR transportation are achieving the highest possible transmission efficiency and ensuring a minimal frequency response over a long transport line while accommodating broadband radiation. The layout of the accelerator hall, experimental room, and radiation transfer line are shown in Fig. 1. The mirror in the transport line will be placed inside the chamber, as illustrated in Fig. 15. To prevent radiation pulse-length elongation and absorption by humid air, the radiation is conveyed in a tube with a diameter of 200 mm, through which nitrogen gas flows. From the previous section, the spectral range of the TR is from 0.3 THz to 2 THz. This spectral range is used to design the radiation-transport line. Our objective is to establish separate transport lines for two distinct experimental stations: one for the THz spectrometer and the other for THz-TDS.

THz-radiation propagation through an optical system can be computed using a first-order approximation of the Gaussian beam formalism combined with the ABCD matrix method [33, 34]. The electric field of a Gaussian beam propagating along the z-axis can be expressed as

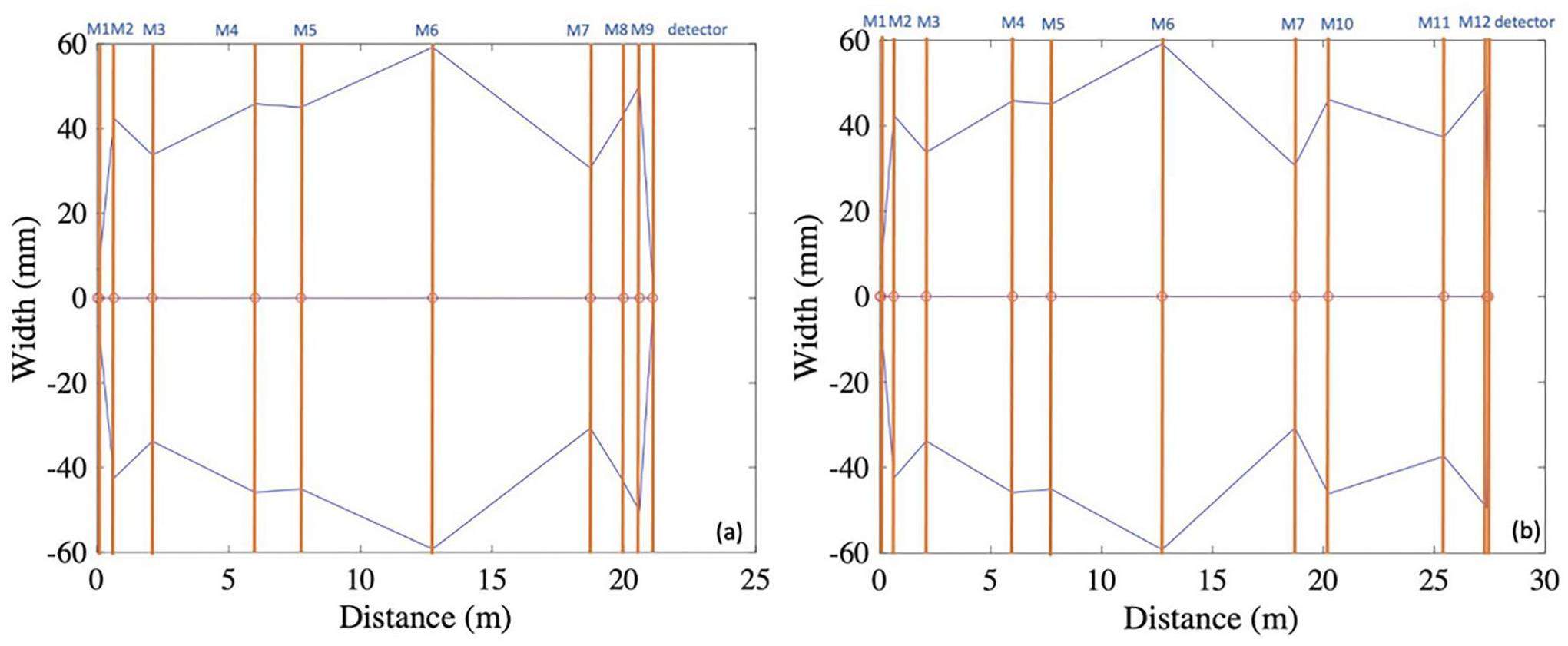

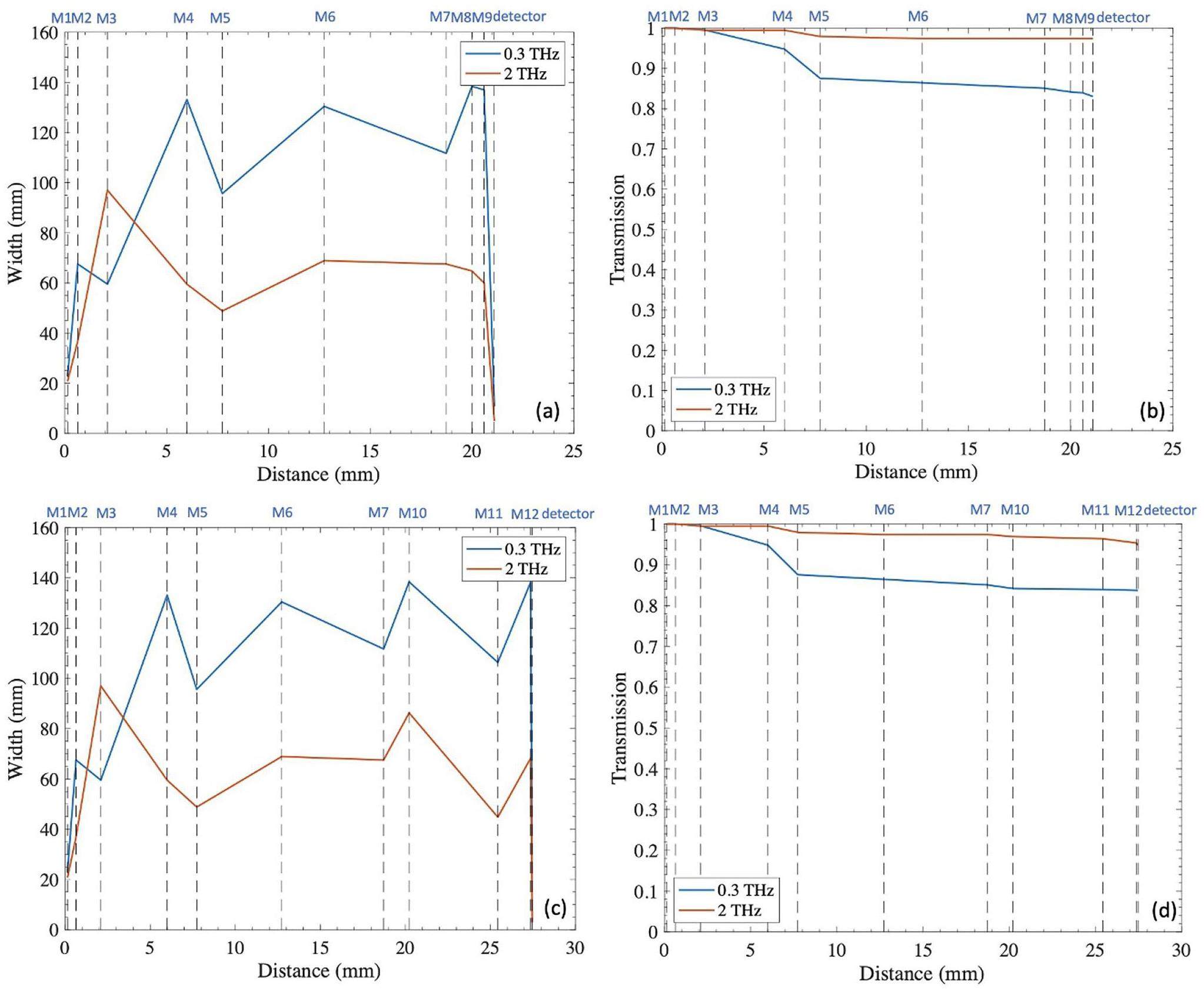

In the initial stage, the optical beamline is designed using ABCD matrices. Because of its large transverse size, our system is limited by its lowest frequency, which is 0.3 THz. The focal length of each mirror is varied to obtain a tight focus at the final position. The beam widths along this distance are shown in Fig. 16.

The diffraction effect significantly affects the transmission efficiency of THz transportation owing to the long wavelengths in the THz region. This effect can lead to the suppression of the radiation spectrum at long wavelengths, resulting in low transmittance. Consequently, when designing a THz transport line, the effects of diffraction must be considered. Thus, the THzTransport code developed by Schmidt at DESY [18] was used to address this issue. This code was designed to compute the generation of transition radiation from a screen of arbitrary size and shape, thereby facilitating the transportation of radiation through the transport line. By employing the Fourier-transform diffraction method, the code handles the propagation of electromagnetic radiation from one optical element to another. Subsequently, the 2D intensity distributions for each optical element were calculated. This code has been employed by several laboratories [17, 18, 35].

Coherent TR must be transported over a distance of 27 m to an experimental room outside the accelerator hall. The radiation has a broad frequency range from 0.3 to 2 THz. In the design of the beamline optics, attention is paid to the low-frequency range, where the diffraction effect is large and causes a large widening of the radiation beam. To address the strong diffraction-beam widening at frequencies below 1 THz, the first focusing element must be positioned closer to the radiation screen. Otherwise, the beam tube strongly suppresses the low-frequency components. The results of the focusing system are shown in Fig. 17. The mirror design parameters are listed in Table 2.

| Mirror | Position (mm) | Focal length (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| M1 (parabolic) | 76.2 | 72.6 |

| M2 (parabolic) | 636.2 | 450 |

| M3 (parabolic) | 2096.2 | 3000 |

| M4 (parabolic) | 5996.2 | 2500 |

| M5 (flat) | 7736.2 | - |

| M6 (parabolic) | 12736.2 | 3000 |

| M7 (flat) | 18726.2 | - |

| M8 (flat) | 19986.2 | - |

| M9 (parabolic) | 20586.2 | 450 |

| M10 (parabolic) | 20226.2 | 2500 |

| M11 (flat) | 25441.2 | - |

| M12 (parabolic) | 27366.2 | 101.6 |

The transport line reduces the maximum radius of the 0.3 THz beam to less than 160 mm. The THzTransport code was used to compute the 2D intensity distributions at the window and optical elements. The result of the TR-beam width at 0.3 and 2 THz is shown in Fig. 18(a,c). The transmission efficiency as a function of the frequency is shown in Fig. 18(b,d). The figures clearly show that the transmittance at low frequencies decreases rapidly with distance because of the widening of the TR angular distribution. This low frequency limits the use of radiation-transport systems. The transmittance is calculated as the ratio of the spectral-energy density at each element and in the vacuum window. Transmission is 80% at 0.3 THz. It increases to approximately 90% at higher frequencies. At frequencies below 0.3 THz, the transmission is low because of diffraction losses in the transport line. The TR transport line provides a broad bandwidth of 0.3–2 THz and pulse energy greater than 0.17 μJ. The spectral energy at the final focus of the transport line is very small at low frequencies because of the widening of the TR angular distribution and diffraction losses in the transport line.

Conclusion

Coherent THz-transition radiation will be generated at the PBP-CMU Electron Linac Laboratory using short electron bunches with kinetic energies in the range 8–22 MeV. The investigated radiation exhibits a high intensity and broadband spectrum, covering frequencies of up to 2 THz. This broad spectral range is facilitated by the small transverse size of the electron beam. The backward TR profile appears asymmetric along the horizontal direction because of the 45°-tilted radiator. The calculation of the radiation spectrum considers the longitudinal and transverse distributions of the electron beam, size of the radiator, and beam splitter.

Furthermore, the transition radiation must be transported from the accelerator hall to an experimental area. The design of the optical transport line was based on theoretical studies on the generation and propagation of transition radiation. Initially, Gaussian propagation combined with an ABCD matrix was used in the design. Subsequently, the THzTransport code was employed to investigate the diffraction of transition radiation along the optical transport line. The design objectives prioritized high transmission over a broad frequency range. The optical transport line was designed to transport frequencies as low as 0.3 THz to the final destination, ensuring a pulse energy greater than 0.17 μJ. After being transported to the experimental room, transition radiation will be implemented as a coherent light source for the THz spectrometer and THz time-domain spectrometer.

Terahertz technology

. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 50, 910 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1109/22.989974Cutting-edge terahertz technology

. Nat. Photonics 1, 97-105 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2007.3The 2017 terahertz science and technology roadmap

. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50,The 2023 terahertz science and technology roadmap

. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 56,Phase-sensitive reflective imaging device in the mm-wave and Terahertz regions

. J. Infrared Milli. Terahz. Waves 30, 1351-1361 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10762-009-9560-0Terahertz imaging: applications and perspectives

. Appl. Opt. 49, E48-E57 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.49.000E48Terahertz Spectroscopic Analysis of Lactose in Infant Formula: Implications for Detection and Quantification

. Molecules 27, 5040 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27155040The TeraFERMI Electro-Optic Sampling Set-Up for Fluence-Dependent Spectroscopic Measurements

. Condens. Matter 5, 8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat5010008Molecular polarizability investigation of polar solvents: water, ethanol, and acetone at terahertz frequencies using terahertz time-domain spectroscopy

. Appl. Opt. 59, 4775-4779 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.392780Matter manipulation with extreme terahertz light: Progress in the enabling THz technology

. Phys. Rep. 836, 1-74 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2019.09.002Intense terahertz radiation and their applications

. J. Opt. 18,Accelerator- and laser-based sources of high-field terahertz pulses

. J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 46Coherent transition radiation from short electron bunches

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 581, 874-881 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.08.155High-intensity far-infrared light source using the coherent transition radiation from a short electron bunch

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 528, 130 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2004.04.033Millijoule terahertz coherent transition radiation at LEBRA

. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 56,Generation, transport, and detection of linear accelerator based femtosecond-terahertz pulses

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82,Ultrabroadband terahertz source and beamline based on coherent transition radiation

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 12,A THz spectroscopy system based on coherent radiation from ultrashort electron bunches

. J. Infrared Milli. Terahz. Waves 39, 681-700 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10762-018-0491-5Coherent transition radiation from femtosecond electron bunches at the accelerator-based THz light source in Thailand

. Infrared Phys. Technol. 82, 387-391 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2018.06.013Femtosecond electron bunches, source and characterization

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 587, 130 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.12.023Accelerator-based terahertz transmission imaging at the PBP-CMU Electron Linac Laboratory in Thailand

. Infrared Phys. Technol. 100, 67-72 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infrared.2019.05.012Coherent THz transition radiation for polarization imaging experiments

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B, 464, 28-31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2019.11.027A Space Charge Tracking Algorithm (ASTRA) Version 3.0

, 2019. http://www.desy.de/mpyflo/Transition radiation and transition scattering

. Phys. Scr. 1982, 182 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/1982/T2A/024Spatial coherence in transition radiation from short electron bunches

. Jetp Lett. 103, 669-673 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0021364016110102Effects of diffraction and target finite size on coherent transition radiation spectra in bunch length measurements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 435, 297-307 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(99)00566-5Far-infrared thin-film beam splitters: calculated properties

. Appl. Opt. 14, 2473-2475 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.14.002473Broadband terahertz characterization of the refractive index and absorption of some important polymeric and organic electro-optic materials

. J. Appl. Phys. 109,Review and analysis of autocorrelation electron bunch length measurements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 568, 923-932 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2006.08.081Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy: Characterization of Nonlinear Crystals, Nanowires, 2D Gratings, Organic Liquids, and Polystyrene Particles

, Ph.D. thesis,Photon transport of the superradiant TeraFERMI THz beamline at the FERMI free-electron laser

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 23, 106-110 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577515021414The authors declare that they have no competing interests.