Introduction

High-brightness photocathode electron guns play an important role in various applications, including free-electron lasers (FELs) [1-6], energy recovery linacs (ERLs) [7-9], and ultrafast electron diffraction (UED) [10-12]. As one of the major limitations for high-brightness operation, the dark current from the gun, originating from the field emission on the inner walls of its accelerating structure, has attracted considerable attention [13-33]. This current is undesirable for stable operation. Particularly, for accelerators operated in continuous-wave (CW) mode, a large amount of dark current may limit the overall performance and long-term reliability of the accelerators [15].

Direct-current (DC), very-high-frequency (VHF), and superconducting radio-frequency (SRF) guns are the primary types of electron guns designed for CW free-electron laser (CW FEL) applications that require high-repetition-rate operation. Table 1 summarizes typical guns used in CW applications. DC electron guns exhibit remarkable performance in GHz repetition rate operations with an extremely low dark current. The cathode surface field, which reaches several megavolts per meter, allows DC high-voltage electron guns to achieve an exceptionally low dark current, typically in the picoampere (pA) range [19, 21]. For instance, JAEA reported an accurate measurement of only 50 pA for the dark current in their DC gun [25]. Normal-conducting (NC) VHF electron guns operate effectively in the MHz CW regime, producing high-brightness beams. Research on VHF guns has been actively conducted at institutions such as Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), SLAC [27, 30], Tsinghua University [32], the Shanghai High Repetition Rate XFEL and Extreme Light Facility (SHINE), and the Shanghai Advanced Research Institute (SARI) [33]. At SLAC, the dark current of the VHF gun was successfully reduced to 2.6 μA at a distance of 1.5 m using a collimator. At ZJLAB and SARI, dark current suppression was achieved by employing a precisely over-inserted plug, which decreased both the electric field intensity and dark current transmission ratio. Experiments with the ZJLAB/SARI VHF gun demonstrated a substantial dark current reduction, lowering it to the level of background noise (~ 1 nA) using a 0.3–0.6 mm over-inserted plug at 870 kV. Additionally, implementing a 0.5-mm over-inserted plug in the SHINE VHF gun significantly reduced the dark current from 570 to 2 nA at 810 kV. SRF electron guns can operate at higher energies with low dark currents. The SRF gun-II developed at HZDR, which uses a 3.5-cell TESLA-type cavity as its accelerating unit, has been reported to generate a 3.5-MeV beam with dark currents on the order of 100 nA [31]. The QWR electron gun at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) can generate a 1–1.5-MeV electron beam with a dark current at the pA level [26]. Although the dark current can be reduced via collimators or fast kickers [20, 22, 33], low-dark-current photocathode guns are highly desired, especially for high-brightness CW operation.

| Parameter | Gun energy | Gradient on the photocathode | Demonstrated emittance | Dark current |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornell DC gun | 0.4 MeV | 4.4 MV/m | ~0.4 μm @100 pC | pA level |

| JAEA DC gun | 0.5 MeV | 5.8 MV/m | N/A | 50 pA |

| SLAC VHF gun | 0.65 MeV | 17.5 MV/m | ~0.5 μm @50 pC | μA level |

| THU VHF gun | 0.78 MeV | 27 MV/m | 0.429 @50 pC; 0.853 @100 pC | 2 nA (SHINE) |

| ZJLAB/SARI VHF gun | 0.87 MeV | 19.8 MV/m | N/A | 1 nA |

| BNL SRF gun | 1–1.5 MeV | 18 MV/m | ~0.3 μm @100 pC | pA level |

| HZDR SRF gun-II | 3.5 MeV | 14 MV/m | 2 μm @200 pC | 100 nA |

| PKU DC-SRF gun | 1.8–2.4 MeV | 6 MV/m | 0.4 @50 pC; 0.54 @100 pC | 2.8–177 pA |

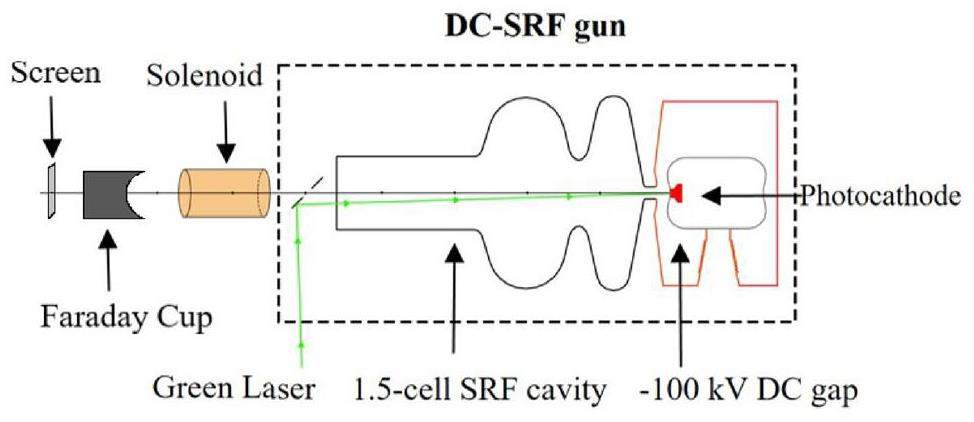

The DC-SRF gun, a DC and SRF combined photocathode electron gun developed at Peking University [34-39], is expected to operate in CW mode with a dark current below 1 nA. It can generate electron beams with a repetition rate of 1 MHz or higher, an average current of up to a few mA, and an energy of a few MeV. The photocathode is located in the DC gap and is therefore separated from the SRF cavity. This not only avoids cavity contamination from the semiconductor materials but also greatly diminishes the dark current arising from the insertion of the photocathode plug into the cathode nose of the electron gun. The DC-SRF gun has undergone three development stages: the prototype (DC-SC), first generation (DC-SRF-I), and second generation (DC-SRF-II). The DC-SRF-II gun operates at a DC voltage of 100 kV and an SRF cavity gradient of approximately 14 MV/m. It employs a K2CsSb photocathode and the 515-nm drive laser has a longitudinal quasi-plateau distribution with a length of 20–30 ps. Simulation studies have shown that the bunch length was at the 10 ps level. The gun has recently achieved stable CW operation [39], delivering a few MeV electron beam at 1 and 81.25 MHz repetition rates, with an average current of up to 3 mA and a dark current several orders of magnitude lower than current normal conducting CW guns. In this paper, we present a comprehensive investigation of the dark current of the DC-SRF-II gun from both simulation and experimental perspectives. Our study findings provide an efficient method for dark-current analysis that accurately reveals the formation of dark current in the DC-SRF gun, laying a solid foundation for gun performance improvement. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief description of the DC and SRF hybrid structure, along with the internal electric field distribution. Section 3 presents the experimental results, covering the conditioning of the DC electrodes and SRF cavity, as well as the dark current measurement results. Section 4 presents the analysis and discussion based on field-emitted electron tracking and experimental data fitting. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

DC-SRF Hybrid Structure and Electric Field Distribution

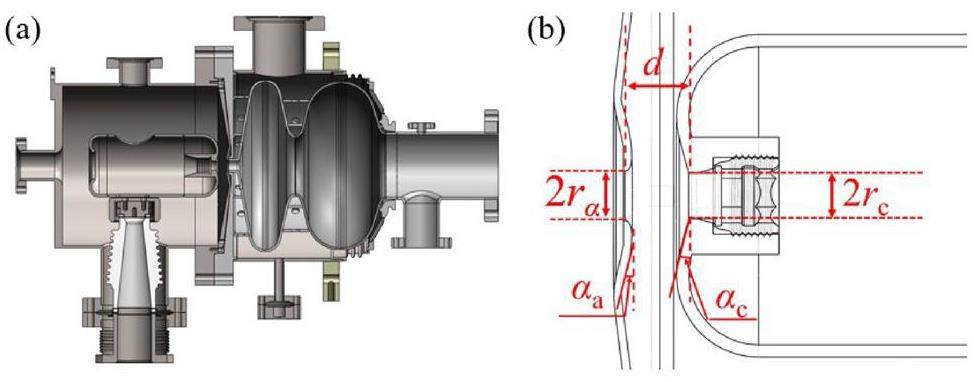

The acceleration structure of the DC-SRF-II gun is illustrated in Fig. 1(a), which comprises a pair of DC high-voltage electrodes, referred to as the “DC gap” hereon, and a 1.3-GHz 1.5-cell SRF cavity connected by a short 11-mm-long drift tube. The DC gap adopts a cathode column-anode plate design whose geometry is characterized by the parameters illustrated in Fig. 1(b). The cathode side has a hole with a radius of rc = 5.5 mm, where the photocathode plug is located, while the anode side has a hole with a radius of ra = 6 mm, which allows for no-loss electron beam transport. The distance between the two holes (d) is 15.5 mm, over which a voltage of 100 kV is exerted. Around the holes, the cathode surface has an inclination angle of

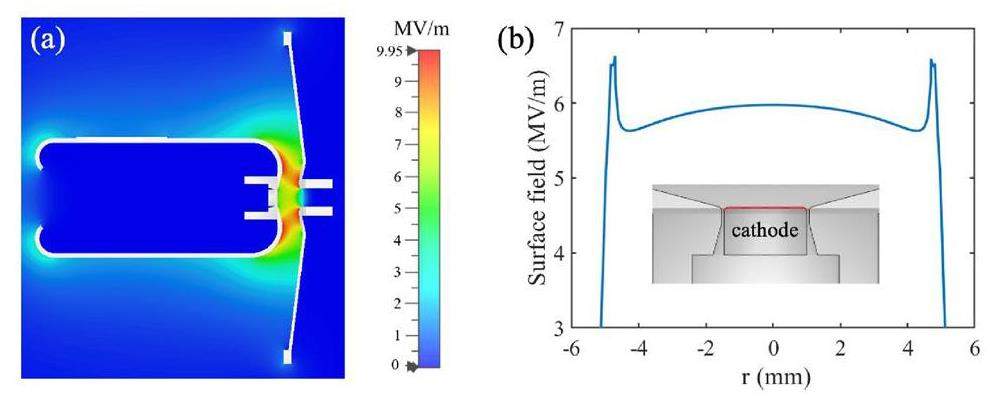

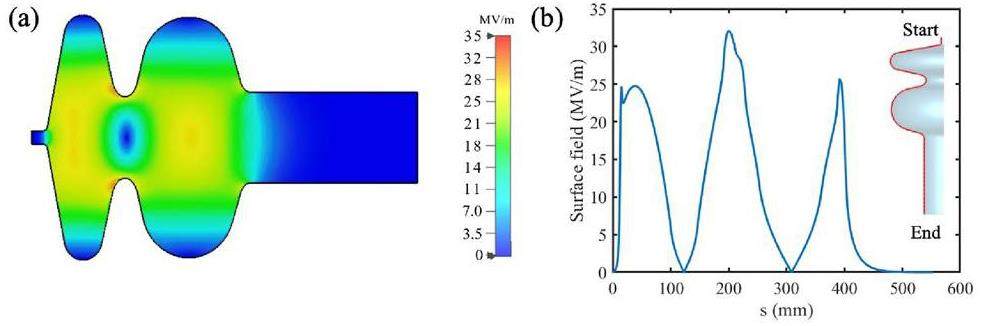

The electric field distribution in the DC gap is shown in Fig. 2(a), where the maximum gradient is restricted to within 10 MV/m to reduce the risk of discharge when the gun operates at a DC voltage of 100 kV. Special attention is paid to the cathode plug area, for which the electric field is shown in Fig. 2(b). It can be seen that the field gradient is 6 MV/m within the central region of the cathode plug. Peaks can also be observed at the edges of the cathode plug; however, they do not cause problems because the field (less than 6.7 MV/m) remains within a relatively safe range.

The SRF cavity comprises a specially designed half-cell and a TESLA-type full cell, which accelerates the 100-keV electron beam from the DC gap to approximately 2 MeV. The half-cell has a conical back wall with an inclination angle of 10.5° and an entrance iris with a radius of 6 mm, which is connected to the DC gap using a short drift tube, as shown in Fig. 3(a). When the SRF cavity operates with an accelerating gradient (

The cathode column, composed of 316L stainless steel, is mounted on a conical reverse ceramic, whereas the anode plate, composed of pure titanium, is detachable from the SRF cavity. This design allows independent polishing and cleaning of the electrodes, thereby improving the operating voltage. The SRF cavity is manufactured from large-grain niobium plates and undergoes a series of post-treatments, including buffered chemical polishing (BCP), high-pressure rinsing (HPR), and high-temperature annealing. The DC electrodes and SRF cavity were assembled in a Class-100 clean room to reduce dust particle contamination.

Experiments

DC electrodes conditioning

The DC components were first conditioned to eliminate field emission at the expected operating voltage of 100 kV, for which the DC-SRF hybrid structure was vacuumized to approximately 1 × 10-5 Pa, while the cryostat was vacuumized to approximately 1 × 10-4 Pa. To avoid high-voltage discharge-induced damage, all vacuum gauges were turned off during conditioning; instead, the ion pump current readouts were used to measure the vacuum. Therefore, the ion current of the pump for the SRF cavity serves as a monitoring signal for arcing (vacuum breakdown) events between the cathode and anode.

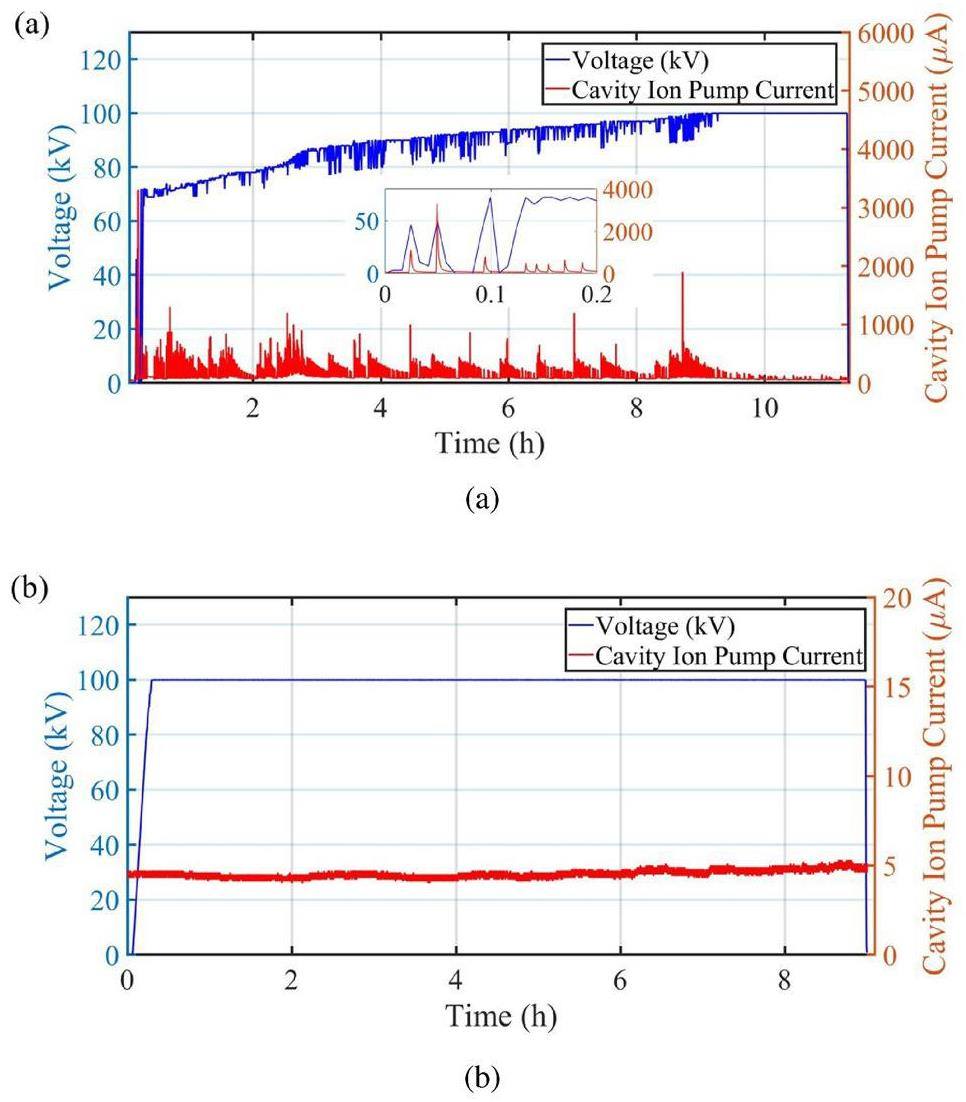

Figure 4(a) shows the recorded DC voltage and vacuum signal during conditioning. The voltage increased to 70 kV in less than 10 min. During this initial stage, interlock protection was triggered by the arcing signal from the DC gap only a few times. Voltage ramping slowed above 72 kV when arcing started to occur frequently. Approximately 160 min were required to reach a voltage of 86 kV. During this second stage, the voltage was only decreased by a few kV when the interlock protection was triggered, as no significant temperature increase was observed from the temperature probes attached to the vacuum chamber of the DC components.

During the third stage, the voltage increased from 86 to 100 kV for more than 6 h. The ramping step was set to 1 kV and the maximum voltage decrement for interlock protection was increased to 10 kV. Finally, the voltage was maintained at 100 kV for approximately 2 h, with the ion current stabilized at the background level. Notably, no arcing was observed at the high-voltage cable junctions in the cryostat during the entire conditioning process.

A 9-h operation test was performed after the DC-SRF-II gun had cooled down. As illustrated in Fig. 4(b), the DC voltage was very stable, and the vacuum signal was at the background level. This indicates that conditioning effectively reduces the number of field emitters in the DC gap, which is a crucial step for achieving low-dark-current operation in the DC-SRF gun.

SRF cavity conditioning

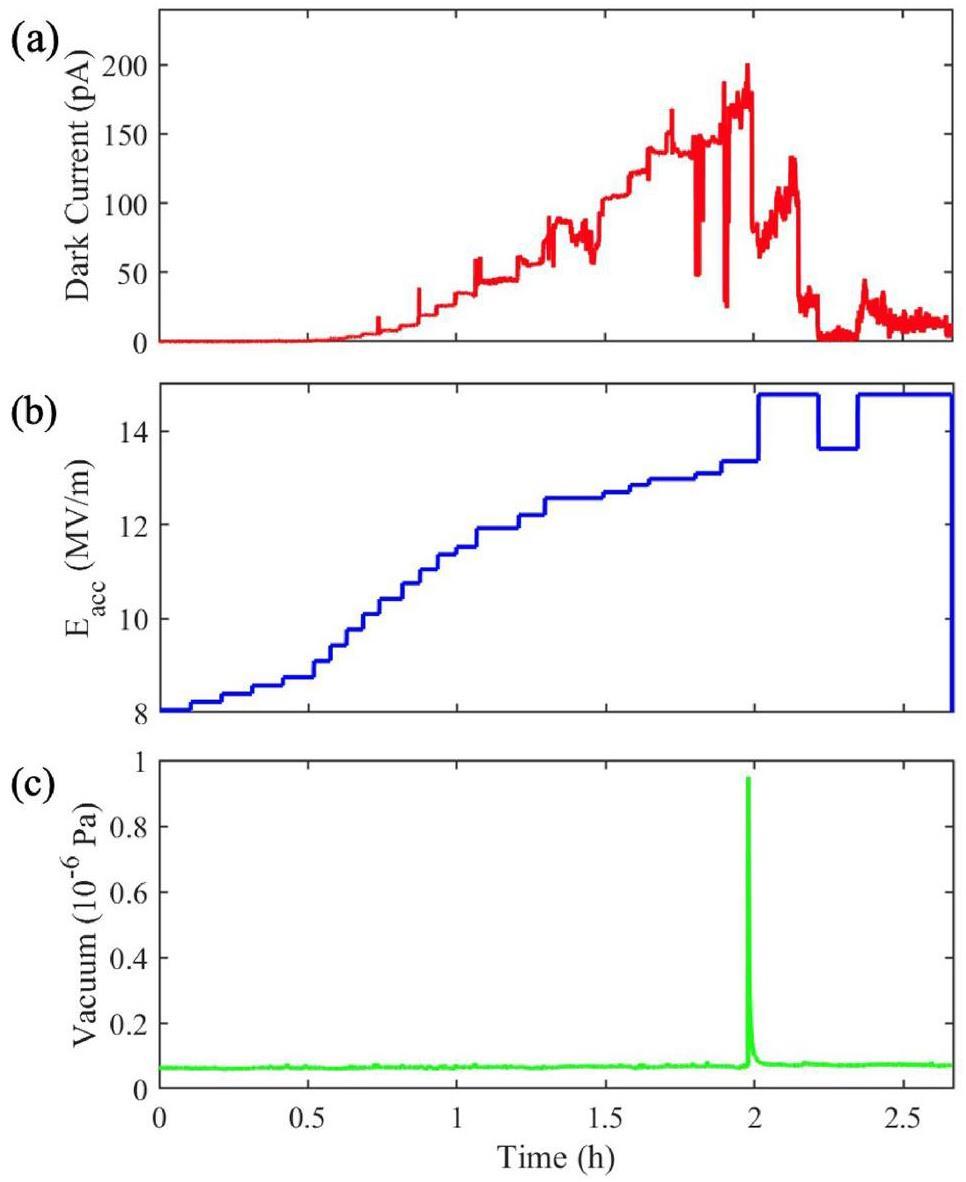

RF conditioning was performed after cooling the SRF cavity. For hardware safety considerations, the SRF cavity was operated in pulsed mode with a duty cycle of 10%. During conditioning, the DC voltage was set to zero and only the dark current from the SRF cavity was monitored. The beamline for the RF conditioning and dark-current study is shown in Fig. 5, which mainly includes a solenoid lens, Faraday cup (FC), and yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) screen, which are located 1.0, 1.3, and 1.5 m downstream from the photocathode, respectively. The field-emitted electrons are focused by the solenoid and collected by the FC. The FC signal, representing the dark current, is recorded by a picoammeter with a 0.1-pA resolution. The YAG screen, along with a 45° reflection mirror and a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera, was used for electron imaging.

Figure 6 shows the monitoring results of the dark current and cavity vacuum during the RF conditioning process. Upon increasing the accelerating gradient to 9.1 MV/m, a weak dark current of 1 pA was initially detected, and a subtle image was observed on the YAG screen. As the gradient continued to increase, the dark current exhibited stepwise growth, reaching a maximum of 201 pA at a gradient of 13.4 MV/m. Subsequently, a fluctuation in the cavity vacuum was observed for the first time, increasing from

Subsequently, the cavity gradient was increased to 14.8 MV/m, 10% higher than the desired value for nominal DC-SRF-II gun operation. The dark current gradually increased to 134 pA and then rapidly decreased to 30 pA. Then, the cavity gradient was decreased to 13.6 MV/m, and the dark current decreased to a few pA. Finally, the gradient was set back to 14.8 MV/m, where the dark current eventually remained at a lower level, with an average value of approximately 14 pA.

Dark current measurements

Measurements were conducted to separately evaluate the dark current originating from the DC gap and the SRF cavity. To accurately measure the dark current originating from the DC gap, the SRF cavity was operated in CW mode with a lower accelerating gradient (close to 10 MV/m), at which a detectable dark current was not generated. The DC voltage was set to 100 kV, and the solenoid field was scanned over a wide range. The picoammeter readout consistently remained at zero throughout the scanning process, indicating that the dark current from the DC gap was less than 0.1 pA and could be neglected in the experiments.

To measure the dark current originating from the SRF cavity, the RF was switched to pulse mode with a 10% duty cycle to ensure RF system safety. The cavity accelerating gradient was scanned between 10 and 14.8 MV/m. At each step, the solenoid field was initially scanned to maximize the picoammeter readout, after which 90 data points were collected, and the average was recorded.

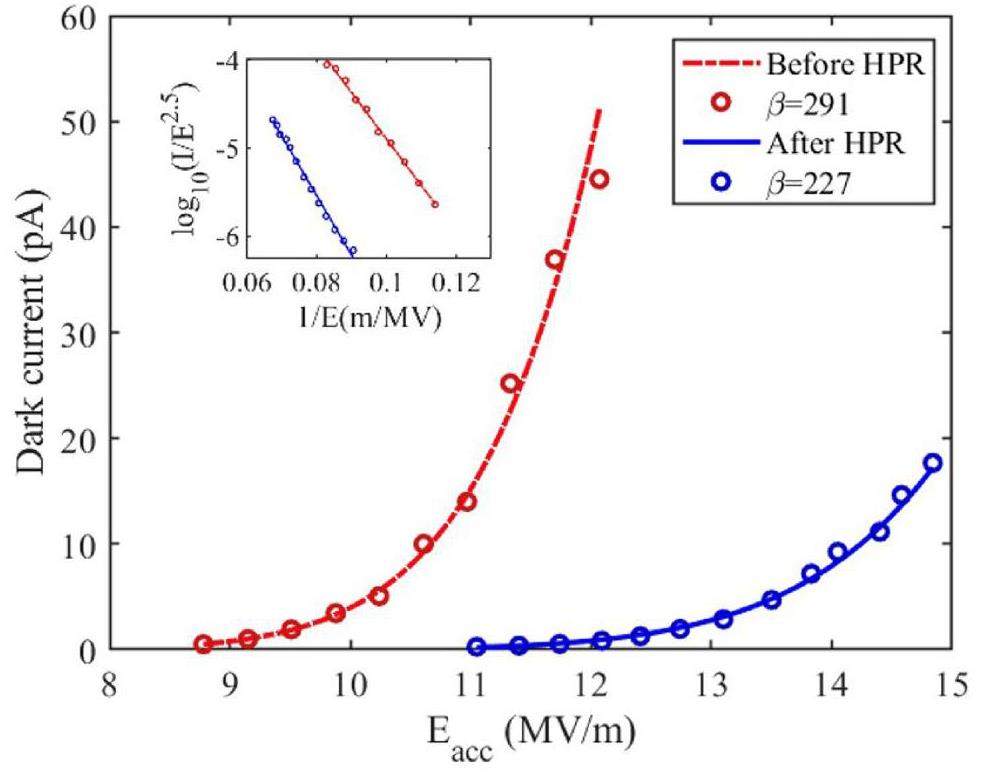

A dark current of 0.28 pA was first detected at an accelerating gradient of 11.1 MV/m. As the gradient increased, the dark current exhibited an exponential growth, reaching a maximum of 17.7 pA at 14.8 MV/m (see the blue line and circles in Fig. 7). This corresponds to a dark current of 177 pA for CW operation, considering the linear dependency of the dark current on the RF duty factor.

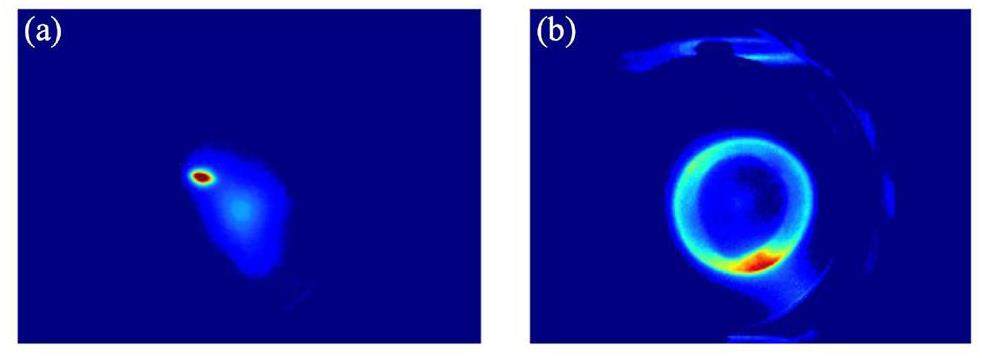

Figure 8 shows images of the field-emitted electrons captured on the YAG screen at different solenoid currents, where the SRF cavity gradient was 11.3 MV/m (corresponding to an

Additional experiments were conducted to measure the energy spectrum of the field-emitted electrons using a

Analysis and Discussion

Field-Emitted Electron Tracking

Numerical simulations were conducted to analyze the dark current using CST [40]. The CST Eigenmode Solver was first used to simulate the three-dimensional RF field within the SRF cavity. Particular attention was paid to the regions near the cavity irises, where the mesh was locally refined to enhance the RF field resolution. The simulation used tetrahedral meshes with 80 cells per wavelength. Local refinement in the iris region was applied with a maximum step size of 0.1 mm, and the total mesh count was 30 million. By applying magnetic boundary conditions, the final number of mesh cells used for the simulation was 7.5 million. This ensured accurate field mapping in regions susceptible to field emission. The obtained RF field was then imported into a particle-tracking solver for field-emitted electron tracking.

Following our experimental results, the cavity gradient

The initial electron energy was set to 4.3 eV, according to the work function of niobium [41], and a 100% energy spread was assumed to account for variations in the emission energies. The emission angles range from 0° to 90°, allowing for a broad potential electron trajectory distribution. In addition, the surface secondary electron emission coefficient (SEC) for niobium was incorporated from the CST database, providing a more realistic depiction of the emission behavior under RF fields.

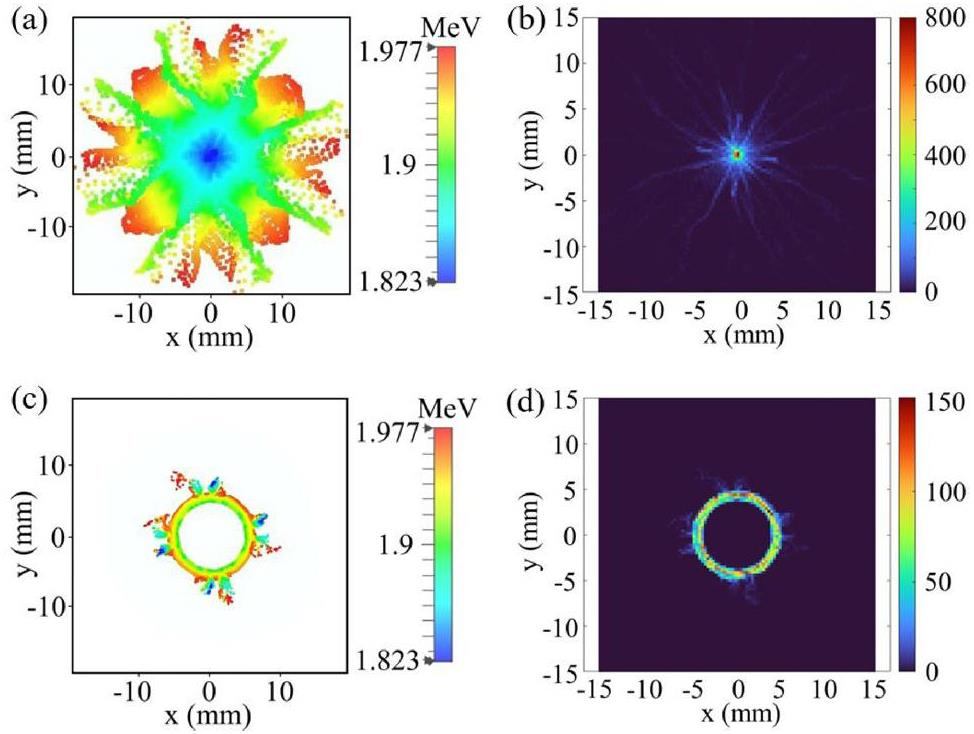

First, we tracked the electrons emitted from the entrance iris of the half-cell. The simulation results showed that only electrons emitted within a phase range of -105 to 45 were able to transport to the beamline. When an appropriate solenoid field was applied, a portion of the electrons could be focused on the YAG screen. Figs. 9(a, b) and (c, d) illustrate the spatial/transverse distributions of the electrons for solenoid fields of 480 and 640 Gs, respectively. The energy of the electrons arriving at the YAG screen was between 1.82 and 1.98 MeV. When the solenoid field was 480 Gs, the lower-energy electrons were focused on a spot (Figs. 9(a) and (b)), similar to that in Fig. 8(a). As the solenoid field increased to 640 Gs, a large number of higher-energy electrons converged, forming a ring (see Figs. 9(c) and (d)) with inner and outer radii of 3.8 and 4.8 mm, respectively. This is similar to the dark-current ring shown in Fig. 8(b), which has inner and outer radii of 3.6 and 4.7 mm, respectively.

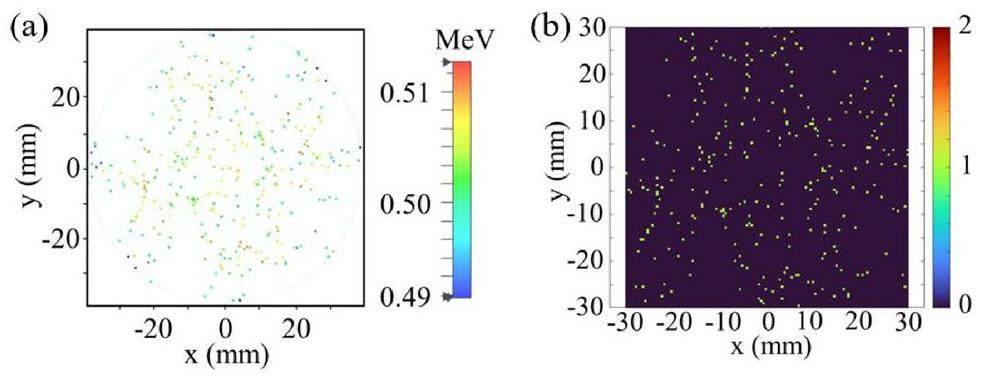

Then, we investigated the acceleration and transport of electrons emitted from the downstream side of the full-cell entrance iris. In this case, higher-energy electrons have large divergence angles owing to stronger RF defocusing. Electrons with energies higher than 0.8 MeV were scraped by the SRF cavity wall due to RF defocusing and the cavity geometry, while those with energies between 0.52 and 0.8 MeV were scraped by the beam pipe. Only a small amount of electrons with energy within 0.45–0.52 MeV could transport to the YAG screen position. Nevertheless, these electrons were overfocused in a solenoid field of 480 Gs (see Fig. 10). This suggests that the field-emitted electrons from the downstream side of the full-cavity entrance iris were not the source of the diffuse spots observed in Fig. 8(a).

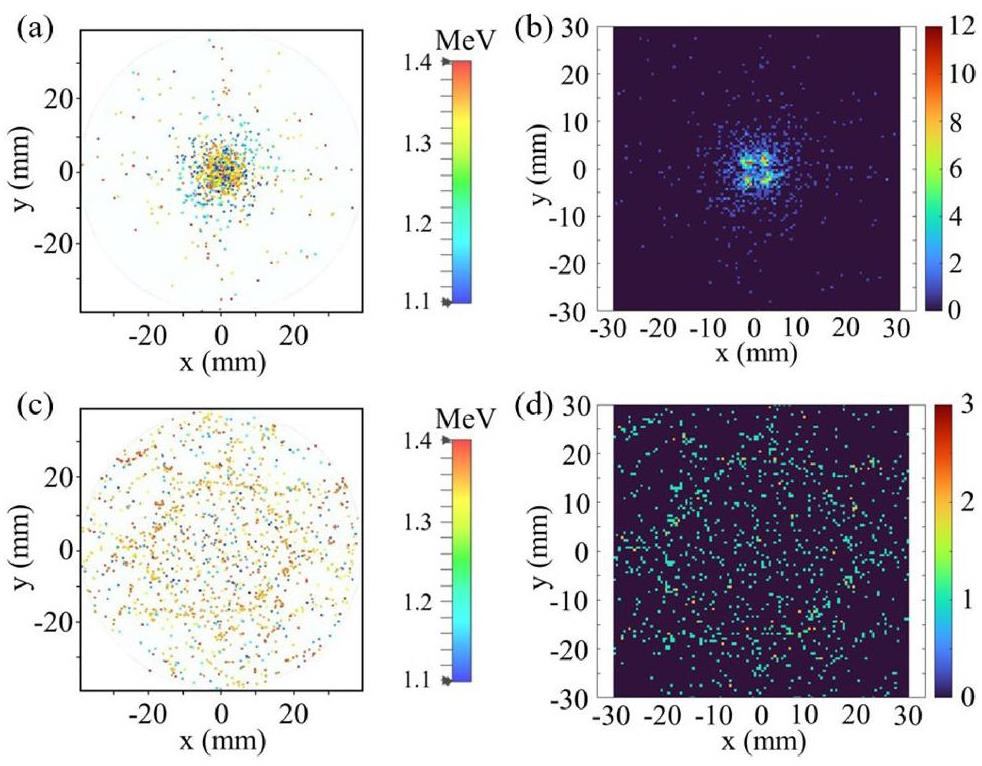

Finally, we tracked the electrons emitted from the upstream side of the full-cell entrance iris, where the maximum surface field occurred, as shown in Fig. 3(b). The simulation results indicate that only electrons emitted in the phase between 200° and 220° had a chance to arrive at the beamline. These electrons initially moved upstream toward the back wall of the half-cell, and the velocity decreased to zero. Then, the electrons underwent acceleration and moved downstream, reaching energies between 1.1 and 1.4 MeV at the SRF cavity exit. At a solenoid field of 480 Gs, a portion of the electrons could be focused on a 4-mm-radius area, as shown in Figs. 11(a) and (b). This aligns with the diffuse spots observed in Fig. 8(a). When the solenoid field increased to 640 Gs, the electrons became overfocused and were subsequently dispersed, as shown in Figs. 11(c) and (d). This explains why we could only observe the ring-shaped profile shown in Fig. 8(b) at 640 Gs.

In summary, the dark current observed in the experiment can be attributed to two distinct sources: the entrance iris of the half-cell (referred to as “A”) and the upstream side of the full-cell entrance iris (referred to as “B”). At a solenoid field of 480 Gs, the lower-energy portion (~ 1.8 MeV) of the electrons emitted from A was focused and formed a bright spot in Fig. 8(a), whereas the electrons (1.1~ 1.4 MeV) emitted from B were focused and formed a diffuse spot. At a solenoid field of 640 Gs, the higher-energy portion (~1.9 MeV and above) of the electrons from A was focused and formed the ring shown in Fig. 8(b), which depicts the shape of the half-cell entrance iris of the SRF cavity. However, the electrons from B became overfocused and dispersed. Note the displacement of the centers of the two spots in Fig. 8(a), which was caused by the misalignment of the solenoid with the SRF cavity.

Experimental Data Fitting

According to the F-N theory[42], the dark current due to the field emission from the SRF cavity can be evaluated as

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Φ (eV) | 4.3 |

| κ | 1.65 |

The fitting results for the dark current measurements of the SRF cavity in Sect. 3.3 are illustrated in Fig. 7. For comparison, we also included the results of an earlier measurement where the SRF cavity was accidentally exposed to air a few times, leading to poor surface conditions. As a result, the cavity operated only at a gradient below 12 MV/m because of concerns regarding the radiation induced by field-emitted electrons. The dark current measured at this gradient was 44.5 pA (10% duty cycle). For improved performance, the DC-SRF gun was disassembled and subjected to HPR. After reassembly, the cavity operational gradient was increased to 14.8 MV/m, as mentioned earlier. The field enhancement factors obtained from the fit before and after HPR were 291 and 227, respectively, indicating a significant improvement in the surface conditions of the SRF cavity. It is worth noting that the correlation coefficients for the F-N linear fitting were 0.998 and 0.997, respectively. The good agreement between the measured datasets and Eq. (1) validates the theoretical model, which assumes that the measured dark current is mostly emitted from the entrance iris of the half-cell. Additionally, the measured dark current was only a portion of the electrons emitted from the cavity surface. The field emission in the SRF cavity was higher, as indicated by the simulation results.

Summary

In summary, in this paper, we present both experiments and simulations of the dark current from a high-brightness DC-SRF photocathode gun. Benefitting from the design, conditioning of the DC electrodes and SRF cavity effectively eliminated the field emitters, enabling the DC-SRF gun to operate at the designed DC voltage and SRF cavity gradient. This laid a solid foundation for the high-performance operation of the DC-SRF-II gun. Particularly, CW operation with a dark current several orders of magnitude lower than that of current normal-conducting CW guns was achieved. Our experimental and simulation results are in good agreement, demonstrating that the dark current during operation primarily originates from the field emission at the entrance iris of the SRF cavity. These electrons exhibited a ring-shaped distribution and could be effectively eliminated using an aperture in the beamline. Additionally, careful processing of the SRF cavity (including HPR) and improving the cleanliness of the assembly environment could further decrease the dark current to obtain a clean high-brightness electron beam for various applications.

First lasing and operation of an Ångström-wavelength free-electron laser

. Nature Photonics 4, 641-647 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2010.176Linac Coherent Light Source: The first five years

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88,Review of fully coherent free-electron lasers

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 160 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-0732-xA MHz-repetition-rate hard X-ray free-electron laser driven by a superconducting linear accelerator

. Nature Photonics 14, 391-397 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-0607-zA compact and cost-effective hard X-ray free-electron laser driven by a high-brightness and low-energy electron beam

. Nature Photonics 14, 748-754 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-00712-8First commissioning results of the coherent scattering and imaging endstation at the Shanghai soft X-ray free-electron laser facility

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 114 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-0146-1The JLab high power ERL light source

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 557, 9-15 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2006.01.122Energy-recovery linacs for energy-efficient particle acceleration

. Nature Reviews Physics, 5, 708-716 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04678-1CBETA: first multipass superconducting linear accelerator with energy recovery

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125,Ultrafast atomic view of laser-induced melting and breathing motion of metallic liquid clusters with MeV ultrafast electron diffraction

. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119,Mega-electron-volt ultrafast electron diffraction at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86, 7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4929430Ultrafast electron diffraction with megahertz MeV electron pulses from a superconducting radio-frequency photoinjector

. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4937199Secondary electron emission in a photocathode RF gun

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 8, 3 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.8.033501Measurement and analysis of field emission electrons in the LCLS gun

. in Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Particle Accelerator Conference (PAC), pp. 1299-1301 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1109/PAC.2007.4440702Dark current transport in the FLASH linac

, in Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Particle Accelerator Conference (PAC), pp. 956-958 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1109/PAC.2007.4440757Dark current monitor for the European XFEL

. in Proceedings of DIPAC (2011). https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-DIPAC2011-MOPD49Surface-emission studies in a high-field RF gun based on measurements of field emission and Schottky-Enabled photoemission

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 20 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.204802Dark current in superconducting RF photoinjectors—measurements and mitigation

. in Proceedings of the 53rd ICFA Advanced Beam Dynamics Workshop on Energy Recovery Linacs (ERL2013), pp. 75-79 (2013).Demonstration of low emittance in the Cornell energy recovery linac injector prototype

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams, 16,Experimental studies of dark current in a superconducting rf photoinjector

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 17, 4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.17.043401Operational experience with nanocoulomb bunch charges in the Cornell photoinjector

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 18,Dark current studies on a normal-conducting high-brightness very-high-frequency electron gun operating in continuous wave mode

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 18,In situ observation of dark current emission in a high gradient rf photocathode gun

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117,Measurement of internal dark current in a 17 GHz, high gradient accelerator structure

. Phys. Rev. Acc. Beam. 22,Operational experience of a 500 kV photoemission gun

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 22,High-brightness continuous-wave electron beams from superconducting radio-frequency photoemission gun

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Commissioning of the SLAC Linac Coherent Light Source II electron source

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 24,Dark current studies of an L-band normal conducting RF gun

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 1010,In situ mitigation strategies for field emission-induced cavity faults using low-level radiofrequency system

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 140 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-0146-1Overview of CW electron guns and LCLS-II RF gun performance

. Front. Phys. 11, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1150809Superconducting radio frequency photoinjectors for CW-XFEL

. Front. Phys. 11, (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1166179Design, fabrication, and beam commissioning of a 216.667 MHz continuous-wave photocathode very-high-frequency electron gun

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 26,Experimental demonstration of dark current mitigation by an over-inserted plug in a normal conducting VHF gun

. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.01754, (2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.01754Research on DC-RF superconducting photocathode injector for high average power FELs

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 475, 564-568 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(01)00498-9Experimental investigations of DC-SC photoinjector at Peking University

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 528, 321-325 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2004.03.068Primary beam-loading tests on DC–SC photoinjector at Peking University

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 557, 138-141 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2006.01.0863.5-cell large grain niobium superconducting cavity for a DC superconducting RF photoinjector

. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 13,Stable operation of the DC-SRF photoinjector

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A, 798, 117-120 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.07.025High-brightness megahertz-rate beam from a direct-current and superconducting radio-frequency combined photocathode gun

. Phys. Rev. Res. 6,CST Studio Suite 2020

, http://www.cst.com, 2020.Improving the work function of the niobium surface of SRF cavities by plasma processing

. Appl. Surf. Sci. 369, 29-35 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.01.089Report No. SLAC-PUB-7684

,