Introduction

X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectroscopy can acquire local structural information and is widely used in scientific research [1, 2], life sciences [3], and environmental studies [4–7]. The advent of synchrotron radiation in the 1970s significantly advanced the development of XAFS technology, allowing it to evolve into a distinct experimental technique integrated with synchrotron facilities [8, 9]. However, the experimental operation of synchrotron beams, which are critical to understanding the chemistry and local structure of new materials, faces challenges owing to their time-consuming nature. Moreover, the transportation of radioactive samples for in-situ synchrotron radiation XAFS experiments is complicated. Therefore, developing X-ray absorption spectrometers based on laboratory scenarios that are compatible with XAFS experimental conditions is urgently required.

X-ray energies and instruments can be classified into the following ranges: soft, tender, and hard [10, 11]. Currently, most laboratory spectrometers are hard X-ray absorption spectrometers (XAS). These spectrometers require crystal monochromators and operate with samples in air; thus, the light is attenuated. However, the absorption and scattering of X-rays by the air decreases significantly as the energy of the X-rays increases. For example, in the actinide field, although the M-absorption edge (3.3–4.0 keV) of the actinide element has a smaller energy broadening than the L-absorption edge (rendering it more sensitive to the valence state [12]), the absorption of X-rays by the air in this energy range is significant, and a satisfactory XAFS map cannot be obtained. This range requires a fully in-vacuum focusing crystal spectrometer.

Commonly used XAFS spectrometers based on laboratory X-ray sources have dispersive or scanning geometries. The spectrometer geometry and diffraction characteristics of the analyzer crystal affect the selection of photon energies and how effectively they are captured. X-ray detection is performed simultaneously across a spectrum of energies using dispersive spectrometers with the Von Hamos design. X-rays with different energies are diffracted at distinct locations on the surface of the crystal analyzer. Then the diffracted X-rays are directed towards a detector capable of spatially differentiating between X-rays with different energy levels. Scanning instruments utilizing the Rowland circle geometry offer an improved signal-to-noise ratio, but they require a more intricate mechanical design [13]. To maintain the Rowland condition, both the analyzer crystals and the detector are adjusted to change the Bragg angle. Silicon or germanium are commonly used as materials for the analyzer crystals, as multiple crystal reflections are required to cover the absorption edges relevant to various elements within the range of X-ray wavelengths. Prior to this work, numerous theoretical calculations of the energy resolution were conducted [14]. Therefore, this study focused on the introduction and application of a tender energy spectrometer.

This study introduces the first laboratory X-ray spectrometer capable of operating in the tender energy range. Specifically, the instrument is designed to facilitate XAFS research within the energy range of 2.0–9.0 keV. The spectrometer design is based on the Rowland circle geometry, and it features a polychromatic micro-focus X-ray source, Johann-type spherically bent crystal analyzer, and silicon drift detector (SDD).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2, outlines the design of the spectrometer and its setup for conducting XAFS measurements. Section 3 details the experimental setup. Section 4 introduces the performance of the proposed spectrometer. Section 5 presents an analysis of the results and advocates for the extensive utilization and further advancement of laboratory-based approaches. Finally, Section 6 provides a concise summary of the study.

Spectrometer design

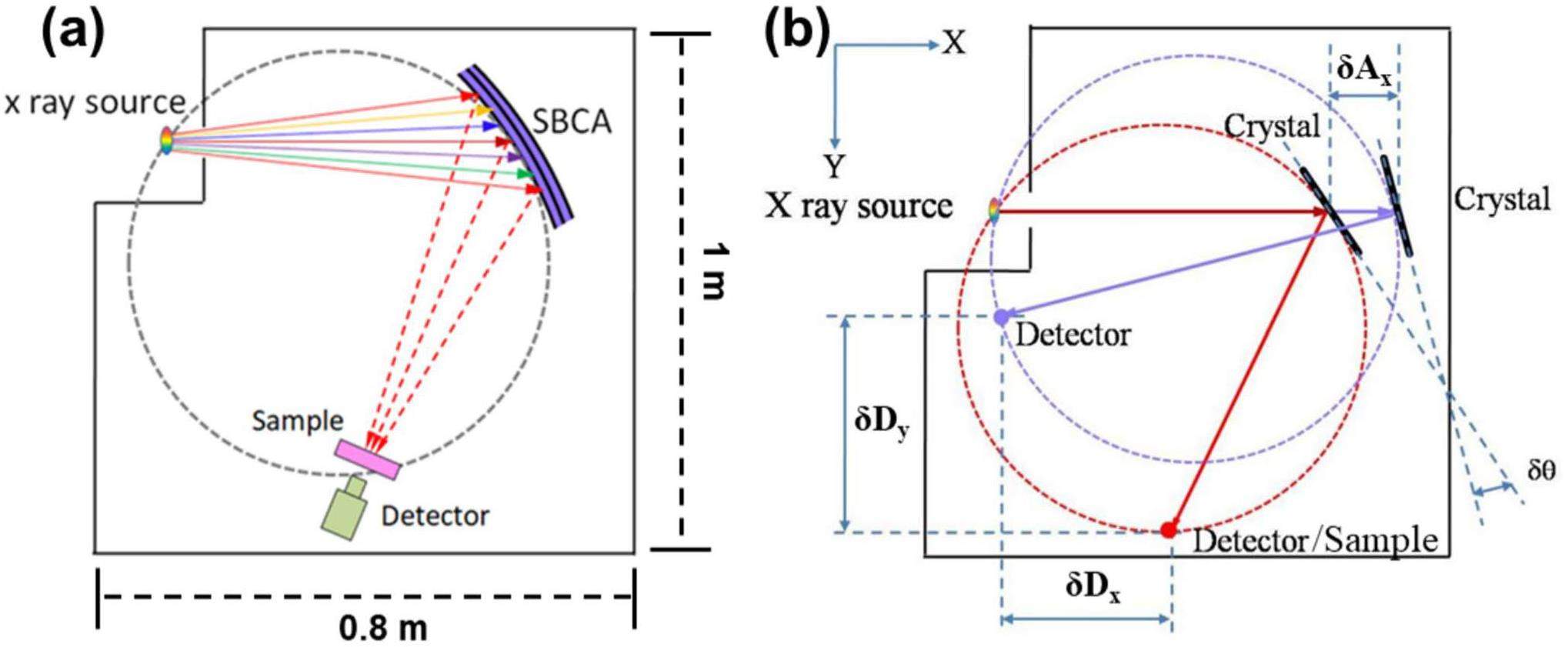

The spectrometer was equipped with a laboratory X-ray source, bent Johann-type spherical crystal monochromator, SDD, and vacuum chamber controlled by LabVIEW. Figure 1(a) shows a schematic of the main components.

X-ray source

The initial X-ray spectroscopy experiments were performed using hermetically sealed X-ray tubes [15]. Excillum, Inc. [16] has developed metal-jet X-ray tubes, which are conventional micro-focus tubes that utilize a liquid metal jet instead of a solid metal anode [15]. The metal jet supports a higher electron beam power, thereby generating a higher X-ray flux. Therefore, Excillum’s D2 was selected for laboratory XAFS measurements. The X-ray source was a high-purity liquid gallium jet anode. The size of the tube’s focal spot was 20 m × 80 m, which was transformed to a point source size of 20 m × 20 m at a take-off angle of 14.5°. The apex angle (opening angle) of the X-ray cone was approximately 8°, which covered a circular area 70 mm in diameter on the crystal. The maximum accelerating potential was 70 kV and the maximum current was 3.57 mA. The X-ray source window was a 50-μm thick beryllium window that transmitted 2-keV X-rays only half, and almost all (more than 82%) were above 3 keV.

Crystal

Johann-type spherically bent crystal analyzers (SBCAs) are used for monochromatizing and focusing polychromatic X-ray “bremsstrahlung” energy. To minimize the impact of strain fields resulting from spherical bending on the energy resolution, crystal wafers were sliced into strips 15 mm wide prior to being bonded with the glass concave substrate. These strips had an energy resolution similar to diced-bent crystals and also had a higher efficiency. All crystals were purchased from XRS LLC, Inc. [17]. The SBCAs had a bending radius of 500 mm and a surface diameter of 100 mm. To cover the widest possible working range within the 2.0–9.0 keV energy range and the spectrometer’s angular scanning range (55–80°), we are gradually expanding our collection of crystal analyzers. Currently, the available analyzer crystals include Si(111), Si(220), Si(311), Si (400), Si(331), Si(422), Si(533), Ge(110), and Ge(620). Table 1 provides an overview of the spectrometer crystals currently accessible, including their respective coverages within the first order of reflection across the working range and theoretical energy Darwin widths corresponding to those reflections. An energy gap exists between 2.4–3.2 keV because Si and Ge do not have crystal planes suitable for the intermediate energy range. Other crystalline materials (e.g., quartz) can cover this energy range; however, processing spherical quartz crystals remains challenging.

| Crystal | 2dhkl (nm) | Energy range (keV) | Darwin width (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Si(111) | 0.6271 | 2.007–2.413 | 0.23225–0.31464 |

| Si(220) | 0.3840 | 3.278–3.941 | 0.19729–0.23914 |

| Si(311) | 0.3275 | 3.844–4.621 | 0.11290–0.13513 |

| Si(400) | 0.2716 | 4.636–5.573 | 0.12183–0.14527 |

| Si(331) | 0.2492 | 5.052–6.073 | 0.07556–0.09003 |

| Si(422) | 0.2217 | 5.678–6.826 | 0.08856–0.10546 |

| Ge(440) | 0.2000 | 6.294–7.567 | 0.15628–0.18357 |

| Ge(620) | 0.1789 | 7.037–8.461 | 0.12471–0.14535 |

| Si(533) | 0.1656 | 7.600–9.137 | 0.03668–0.04367 |

Detector

For transmission XAFS measurements, the spectrometer was equipped with an Amptek Fast SDD, which effectively captured the intensity of the diffraction signal throughout the data collection process. The Amptek Fast SDD is a vacuum-compatible detector with excellent energy resolution that suppresses higher-order harmonics in the diffraction signal while minimizing the background noise. It features a 500-μm thick silicon sensor layer bonded to the top of the electronic layer, providing an effective area of 50 mm2. The SDD can achieve a counting rate of up to 1 × 106 counts/s with a peak time constant of 0.2 μs. The energy resolution was 123 eV at 5.9 keV. Integrated within the SDD was a two-stage Peltier cooling system designed to prevent heat buildup and ensure efficient operation.

Motors and movement

The X-ray source was kept stationary outside the vacuum chamber. The crystal analyzer was mounted on a motorized module that provided vertical and pitch angular adjustments for alignment as well as horizontal and rotational adjustments for energy scanning. The goniometer held the detector and was positioned on two linear stages, Dx and Dy, as shown in Fig. 1(b). The energy-scanning mechanism of the spectrometer followed the Bragg angle equation and trigonometric formulas, which defined the geometric requirements of the Rowland circle.

The X-ray source, sample, and bent crystal analyzer were arranged on a Rowland circle with diameter R. The detector was rigidly connected to the sample, which was always directed at the center of the spherical curved crystal by a mechanical linkage. For the tests, the sample was placed in front of the detector. Whenever the Bragg angle θ or energy changed, the position of the detector on the Rowland circle needed to be shifted. Both the angle and distance of the bent crystal analyzer were simultaneously adjusted. Using the position of the X-ray source as the origin of the coordinate system, the x-axis was defined as the direction from the source to the crystal, and the y-axis was defined as the direction from the source to the detector. The bent crystal moved exclusively along the x-axis. The spectrometer’s motor positions (Ax, Dx, and Dy) for a specific photon energy E (measured in eV) are given by

Vacuum chamber

The tender X-ray monochromator employed a custom vacuum chamber with a pressure of 10-6 mbar, which was achieved using a 700-L/s vacuum pump. To prevent mechanical deformation due to pressure differences, all the mechanical components were mounted on a separate sturdy steel plate within the vacuum chamber, ensuring that the diffraction plane was aligned. Owing to the volume limitations of individual components, achieving proximity during the operations proved challenging, resulting in vacuum chamber dimensions of 1 m × 0.8 m × 0.6 m and Bragg angles ranging from 55° to 80°.

Experimental setup

The XAFS measurements were conducted in transmission mode. The emission power and spot position of the metal-jet X-ray tubes were highly stable, allowing separate measurements of the transmitted and direct beams using the same detector. All tests were conducted using a laboratory tender XAFS spectrometer (SuperXAFS series).

To demonstrate the capabilities of the instrument, seven samples are shown in Table 2. Owing to spherical aberration, the focal lengths exhibited a significant difference along the vertical and horizontal directions of the detector. This discrepancy varied depending on factors such as the Bragg angle and crystal plane. The measurements indicated an approximate range of 4–6 mm for the vertical focal length and 1–2 mm for the horizontal focal length. For XAFS tests in transmission mode, high sample homogeneity is crucial in both laboratory and synchrotron radiation setups [18]. By placing a slit in front of the sample, the spot size can be adjusted accordingly. Additionally, a uniform 10-mm sample can be obtained by pressing, ensuring uniformity over the spot scale.

| Ti K edge | U M5 edge | Th M5 edge | Co K edge | Ni K edge | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption edge energy (eV) | 4966 | 3552 | 7709 | 8333 | |||

| Crystal analyzer | Si400 | Si220 | Si533 | Si444 | |||

| Reflection (n) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Bragg angle, θB (°) | 66.865 | 65.367 | 76.153 | 71.626 | |||

| Sample | rutile TiO2 | anatase TiO2 | Ti foil | UO2 | ThF4 | Co foil | Ni foil |

| Voltage (kV) / Current (mA) | 21/ 3.57 | 21/ 3.57 | 21/ 3.57 | 30/ 3.30 | 30/ 3.30 | 30/ 3.30 | 40/ 3.00 |

| Thickness (µm) | - | - | 6 | - | - | 4 | 6 |

| Monochromatic flux with sample (counts/s) | 1.30 × 105 | 1.30 × 105 | 1.50 × 105 | 1.40 × 105 | 2.10 × 105 | 2.48 × 105 | 2.50 × 105 |

| Energy Darwinian width (eV) | 0.13012 | 0.13012 | 0.13012 | 0.21433 | 0.2006 | 0.0371 | 0.04797 |

The test conditions for the samples are listed in Table 2. All metal foils were purchased from Exafs Materials, Inc. [19], and TiO2 was purchased from Aladdin, Inc. [20]. The beam intensity was measured both without the sample (I0) and with the sample (It). Each scan consisted of 350 energy points, a counting time of 5 s per point, and a motor delay time of 1 s per point. The minimum energy step was set as 0.1 eV. The dead time of all detectors was less than 25%.

Spectrometer performance

Monochromatic Flux

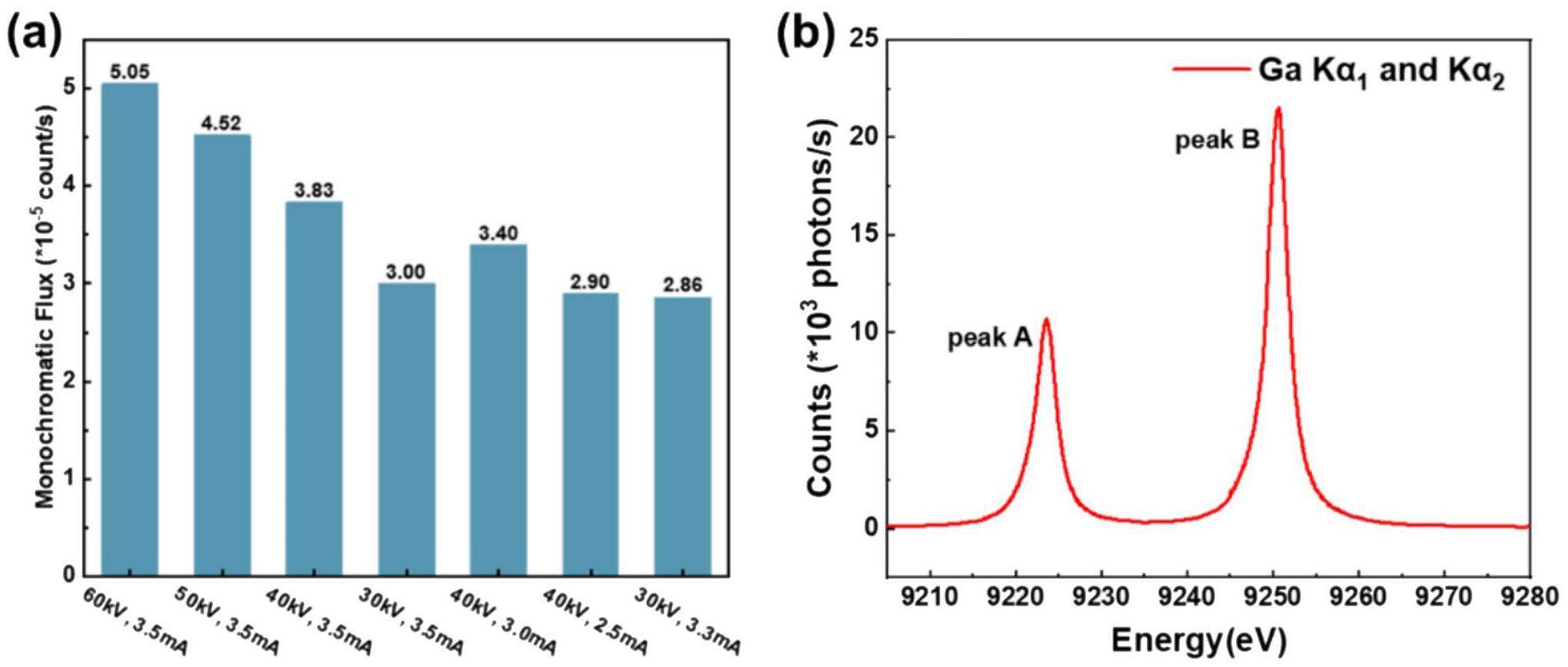

The monochromatic flux was tested with Ge (620) crystals in the energy range of 7040–7050 eV (Fig. 2(a)). When the voltage was held constant and the current was decreased, the counting rate decreased. The counting rates corresponding to the same power were similar. When the current was held constant and the voltage was increased, the counting rate increased, reaching a maximum at 60 kV, 3.5 mA, and 210 W (approximately 5 × 105 counts/s).

Energy Resolution

Directly evaluating the energy resolution of laboratory source systems is challenging. Two factors contribute to the total energy resolution: energy broadening corresponding to the core-hole lifetime and the intrinsic energy resolution of the spectrometer. To characterize the energy resolution of the spectrometer, we used the characteristic peaks of the X-ray source to obtain a strong signal. The X-ray source was operated at 120 W (40 kV, 3 mA) using a Si553 crystal monochromator. Figure 2(b) shows the test results: peaks A and B were fluorescence peaks for gallium Kα2 (9223.8 eV, Bragg angle 71.905°) and Kα1 (9250.6 eV, Bragg angle 71.403°), respectively. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of peaks A and B were 2.96 eV and 2.89 eV, respectively. The energy broadening corresponding to the core-hole lifetime of the Ga Kα2 and Kα1 peaks were 2.66 eV and 2.59 eV, respectively [21]. The final energy resolution of the instrument (△E) was 1.298 eV at 9223.8 eV and 1.28 eV at 9250.6 eV.

Additionally, we theoretically derived the instrument resolution for different energy ranges (Eq. 5). First, we obtained the value of △E1 for the crystal based on the tested value of △θ and the crystal energy at 71.905º. The value of △E1 is the difference between the energy resolution of the spectrometer and the energy Darwinian width (ΔED) of the crystal. In a laboratory spectrometer, different energy ranges correspond to different crystal diffraction planes. Therefore, Darwin width correction was applied to each diffraction plane to obtain the final instrument resolution (the Darwin width of each crystal at a Bragg angle of 71.905° was obtained from the XAS data for the elements). As shown in Table 3, the energy resolution ranged from 0.36 to 1.30 eV at 2.0 to 9.0 keV, covering the instrument’s energy range. The energy resolution is expressed as

| Crystal | Energy (eV) | ΔED | ΔE1 | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si(553) | 9223.8 | 0.02707 | 1.29572 | 1.296 |

| 9250.6 | 0.02715 | 1.28171 | 1.282 | |

| Si(422) | 5882.9 | 0.08275 | 0.82640 | 0.831 |

| Si(331) | 5234.3 | 0.07062 | 0.73529 | 0.739 |

| Si(400) | 4803.3 | 0.11389 | 0.67475 | 0.684 |

| Si(311) | 3982.7 | 0.10566 | 0.55947 | 0.569 |

| Si(220) | 3396.5 | 0.18496 | 0.47712 | 0.511 |

| Si(111) | 2079.9 | 0.22680 | 0.27985 | 0.360 |

Results and discussion

XANES

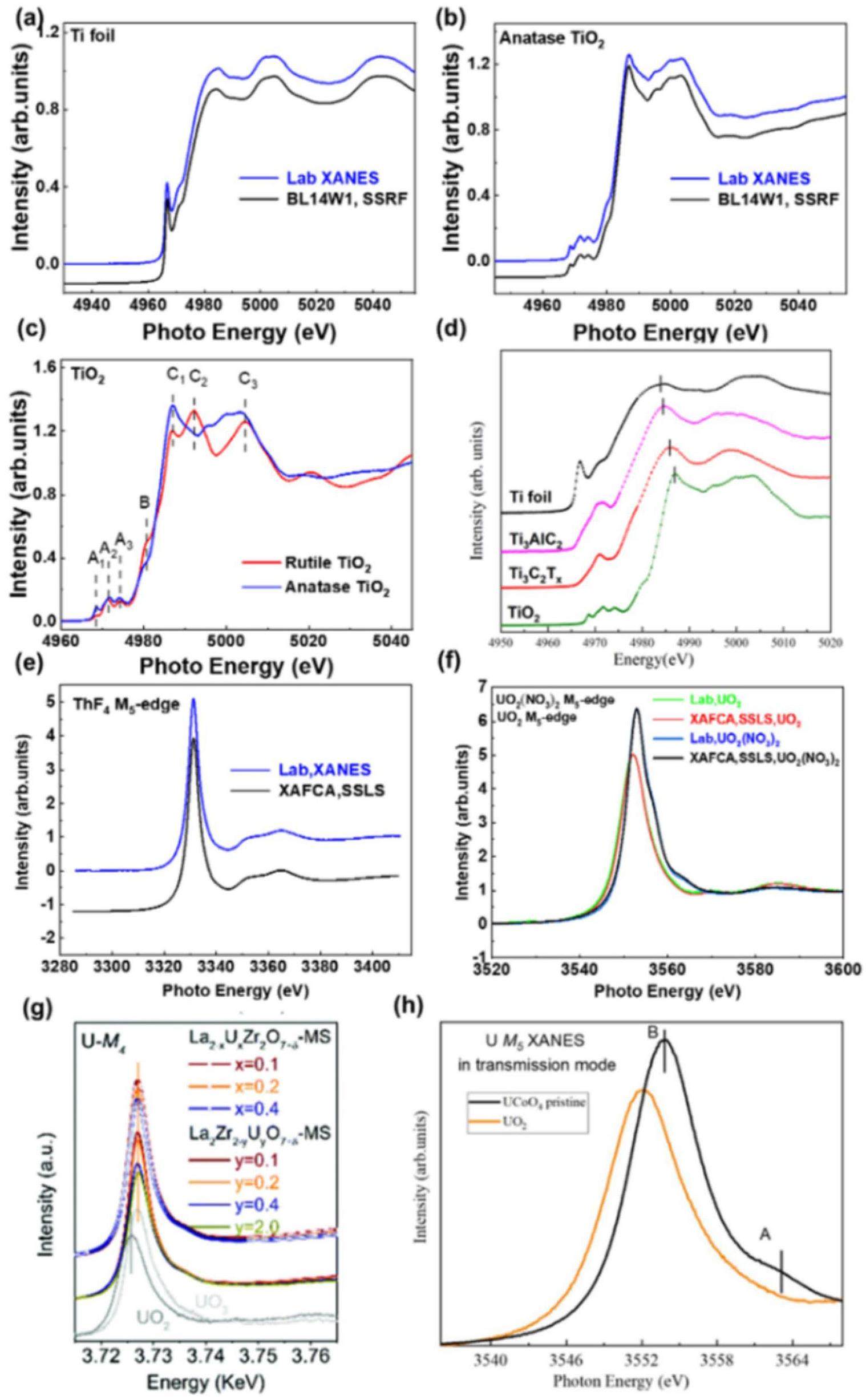

In Figs. 3(a) and (b), the normalized K-edge X-ray absorption near the edge structures (XANES) of the titanium foil and anatase TiO2 are shown alongside the synchrotron data from the BL14W1 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). All XAFS data were background removed and normalized using the software package Athena [22]. The Bragg angle, denoted as θ = 66.865°, was determined based on the first peak observed in the derivative spectrum of the Ti foil and assigned a value of 4966 eV. The consistency of the spectra shown in Fig. 3(a) suggests that the energy resolution of the laboratory monochromator was similar to that (1.0 eV) achieved using a double-crystal Si(111) monochromator for a synchrotron. Nevertheless, recognizing the inherent challenges associated with directly assessing the energy resolution in laboratory source systems is crucial, as it encompasses both the measurement of the FWHM and comprehensive characterization of the entire energy spectrum. The FWHM of the pre-edge peak of the Ti foil was approximately 1.2 eV. All features could be reproduced, demonstrating that the laboratory device was suitable for a wide range of applications.

The XANES spectra of the TiO2 in anatase and rutile forms is displayed in Fig. 3(c). The spectrum consisted of pre-edge components A1–A3, a distinctive shoulder B, and multiple peaks C1–C3. Other studies [26–28] have described the origins of these features. In the rutile TiO2 sample, features A1 and A2 appeared at lower energies compared to the anatase sample, whereas features B and C appeared at the same energies as those of the anatase.

In our previous study, we employed a tender X-ray monochromator to analyze MXene materials (a type of 2D material [29]), as shown in Fig. 3(d). We primarily focused on performing near-edge structural analysis of Ti3AlC2 and Ti3C2Tx materials (a type of MXene), particularly those pertinent to supercapacitor applications [23]. Building on these findings, we thoroughly investigated the structural attributes and valence changes.

Unlike the actinide L-edge, the M-edge of actinide elements exhibits less pronounced core energy level broadening and greater sensitivity to valence states. However, the M-edges of Th (3.3 keV) and U (3.5 keV) are outside the range of hard X-rays (> 5 keV) and have not been effectively tested using laboratory X-ray absorption spectrometers. However, these values are within the energy range suitable for tender X-ray monochromators. Accordingly, the Th and U M-edge absorption spectra were experimentally examined using a laboratory light source, as shown in Figs. 3(e) and (f).

Figure 3(f) shows the normalized XANES spectra of UO2 and UO2(NO3)2 along with the synchrotron data obtained from the XAFCA beamline at the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS). XAFS data were normalized using the Athena software package [22]. Compared to the XAFCA and SSLS data, the UO2(NO3)2 and UO2 spectra collected by the laboratory spectrometer showed a high degree of agreement, indicating that the energy resolution of the spectrometer was comparable to that of synchrotron radiation near 3.5 keV. All the observed features were reproducible, and this level of replication was adequate for most applications.

To support the nuclear energy sector’s efforts to immobilize actinide waste efficiently (Fig. 3(g)), we employed conventional U-M4 edge XANES spectra to test the valence state of uranium ions and their coordination environment in samples of U-doped La2Zr2O7 -MS [24]. In the regime of efficient catalysts (Fig. 3(h)), the XANES analysis revealed an upward shift in the U-M5 XANES spectra obtained from the transmission mode measurements of the UCoO4 catalysts [25], confirming the presence of U6+ and providing critical evidence of electronic structure modulation among polymetallic sites.

EXAFS

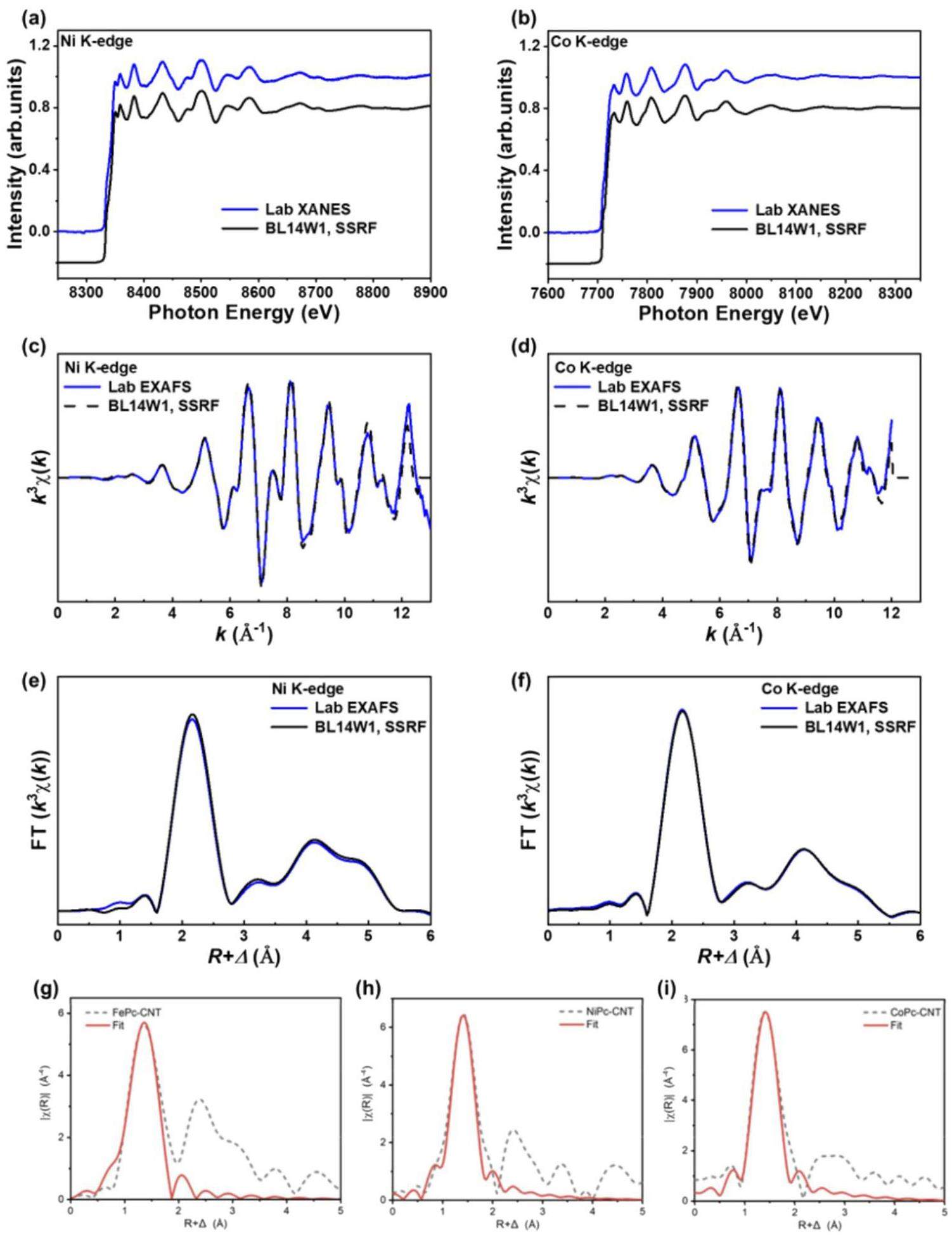

The Bragg angles ranged from 55° to 80°, allowing the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) measurements to extend up to or beyond 1000 eV above the absorption edge. Ni and Co foils were selected as samples for the different energy ranges. The XAFS data for these samples are shown in Fig. 4. Figures 4c and d show the k-space spectra of the two samples, and Figs. 4e and f display the R-space spectra. The EXAFS spectra obtained from the laboratory spectrometer and 14W1 beamline at the SSRF were comparable in their k-space oscillations (2 – 12 Å-1), as shown in Figs. 4(a-f). In the regime of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (Figs. 4g–i), the transition metal EXAFS of MPc (M=Fe, Co, Ni) catalysts supported on carbon nanotubes was analyzed using a tender X-ray monochromator [30]. The coordination number and bond length were ascertained via the fitting results, significantly contributing to the elucidation of the catalyst’s structure.

Conclusions and outlook

In this study, we presented the design and performance of a laboratory-based XAFS spectrometer that utilized an X-ray source. Laboratory investigations played a crucial role in preliminary characterizations of the materials prior to the synchrotron analysis. The enhanced configuration incorporated a focusing mirror and positioned the sample behind the detector, thereby enabling a broader energy range owing to the utilization of high-power X-ray sources and detectors with high counting rates. With accessible laboratory spectrometers, XAFS has the potential to become a standard sample characterization method, similar to other X-ray based experimental methods.

XAFS spectroscopy in catalysis research: AXAFS and shape resonances

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 6, 135-141 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1107/S0909049599002010Sintering-induced cation displacement in protonic ceramics and way for its suppression

. Nat. Commun. 14, 7984 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43725-xBiological X-ray absorption spectroscopy (BioXAS): a valuable tool for the study of trace elements in the life sciences

. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 18, 609-616 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2008.06.002Micro-beam XAFS reveals in-situ 3D exsolution of transition metal nanoparticles in accelerating hydrogen separation

. The Innovation Materials 2,Enhanced H2 permeation and CO2 tolerance of self-assembled ceramic-metal-ceramic BZCYYb-Ni-CeO2 hybrid membrane for hydrogen separation

. J. Energy Chem. 82, 47-55 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2023.03.027Suppressing structure delamination for enhanced electrochemical performance of solid oxide cells

. Small Methods 5,Key roles of initial calcination temperature in accelerating the performance in proton ceramic fuel cells via regulating 3D microstructure and electronic structure

. Small Struct. 5,Development of a laboratory EXAFS facility

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 49, 1658-1666 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1135340A new type of x-ray absorption spectrometer

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 50, 1020-1021 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1135970Applications of “tender” energy (1-5 keV) X-ray absorption spectroscopy in life sciences

. Protein Pept. Lett. 23, 300-308 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2174/0929866523666160107114505X-ray spectrometry

. Anal. Chem. 78, 4069-4096 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac060688jComments on core-hole lifetime effects in deep-level spectroscopies

. Phys. Rev. B 17, 929 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.17.929Modern X-ray spectroscopy: XAS and XES in the laboratory

. Coord. Chem. Rev. 423,Johann-type laboratory-scale x-ray absorption spectrometer with versatile detection modes

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 90,Collecting data in the home laboratory: evolution of X-ray sources, detectors and working practices

. Acta. Crystallogr. D 69, 1283-1288 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444913013619X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) studies of oxide glasses—a 45-year overview

. Materials 11, 204 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11020204Natural widths of atomic K and L levels, Kα X-ray lines and several KLL Auger lines

. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 8, 329 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555595ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537-541 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1107/s0909049505012719One-pot green process to synthesize MXene with controllable surface terminations using molten salts

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 27219-27224 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202110640Atomic controllable anchoring of uranium into zirconate pyrochlore with ultrahigh loading capacity

. Chem. Commun. 58, 3469-3472 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CC00576J5f covalency synergistically boosting oxygen evolution of UCoO4 catalyst

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 416-423 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c10311Ti K-edge XANES studies of Ti coordination and disorder in oxide compounds: Comparison between theory and experiment

. Phys. Rev. B. 56, 1809 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.56.1809X-ray absorption linear dichroism at the Ti K edge of anatase TiO2 single crystals

. Phys. Rev. B. 100,X-ray absorption linear dichroism at the Ti K-edge of rutile (001) TiO2 single crystal

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 27, 425-435 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1107/S160057752000051XFundamentals of MXene synthesis

. Nat. Synth. 1, 601-614 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-022-00104-6Electrocatalytic CO2 Upgrading to Triethanolamine by Bromine-Assisted C2H4 Oxidation

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62,Jian-Qiang Wang and Lin-Juan Zhang are editorial board members for Nuclear Science and Techniques and were not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.