Introduction

The nuclear equation of state (EoS), particularly the symmetry energy, is essential in both nuclear physics and astrophysics [1-7]. In nuclear physics, the symmetry energy significantly affects the structure of finite nuclei, including the neutron-skin thickness of heavy nuclei [8]. In astrophysics, it influences the key properties of neutron stars, such as their masses and radii [3, 4], as well as their cooling processes [9]. Consequently, constraining the symmetry energy is an important challenge in nuclear physics.

Many experimental attempts have been conducted to constrain the symmetry energy around the saturation density ρ0 [10-23]. These include measurements of the dipole polarizabilities of 208Pb [14, 15], giant dipole resonance energies [13], isospin diffusion in heavy-ion collisions [11], isobaric analog states [19], and neutron skin thickness [12, 24]. Because of the extensive research on determining the symmetry energy, the constraint on the symmetry energy at saturation density is relatively precise, with a commonly accepted value of

In contrast, the symmetry energy at suprasaturation remains unclear. Many terrestrial experiments have been performed to extract information on symmetry energy at suprasaturation. In studies on heavy-ion collisions, the constraints on the suprasaturation density dependence of the symmetry energy have been obtained from analyses of the π-/π+ ratio [25-31] and n/p elliptic flows ratio [32, 33]. However, the symmetry energy at supurasaturation densities exhibit a large model dependence. This is caused by the difficulties in solving the transport models and extrapolating the finite excited nuclear system to infinite nuclear matter at zero temperature. Consequently, further progress in understanding and constraining the equations of state for nuclear matter at high densities is expected from analyses that incorporate the properties of neutron stars.

The mass measurement of the pulsar PSR J0740+6620 from the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer [34, 35] revealed a neutron star with a mass of

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review the theoretical aspects of RMF models, the EoS of a neutron star, and the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkov (TOV) equation. In Sect. 3, we present the results of the constraint on the symmetry energy obtained from the neutron star observations. Finally, the summary is presented in Sect. 4.

Model

Relativistic mean field

In this paper, we employ the framework of RMF models to extract information on the symmetry energy in symmetric nuclear matter (SNM) systems. RMF models provide a comprehensive description of both nuclear matter and finite nuclei and are widely used to study neutron star properties. To better categorize the parametrizations associated with RMF models, Ref. [53] defined three distinct types: (i) nonlinear, (ii) density-dependent, and (iii) point-coupling models.

The Lagrangians for the different RMF models are

1. Nonlinear (NL) model

As an example, we use the nonlinear RMF model to present the expressions of relevant quantities [51-53]. In the RMF model, meson fields can be replaced with their expectation values:

The binding energy per particle in asymmetric nuclear matter can be expressed as follows:

For SNM,

(i)165 nonlinear RMF models (E [61], ER [61], NL1 [51], NL3 [62], NL3-II [62], NL3* [63], NL4 [64], NLC [54], NLB1 [51], NLB2 [51], NLRA1 [65], NLS [66], P-067 [67], P-070 [67], P-075 [67], P-080 [67], GL1 [68], GL2 [68], GL3 [68], GL4 [68], GL5 [68], GL6 [68], GL7 [68], GL8 [68], GL82 [69], GL9 [68], GM1 [70], GM2 [70], GM3 [70], GPSa [71], GPSb [71], NLρA [72], NLρB [72], RMF301 [73], RMF302 [73], RMF303 [73], RMF304 [73], RMF305 [73], RMF306 [73], RMF307 [73], RMF308 [73], RMF309 [73], RMF310 [73], RMF311 [73], RMF312 [73], RMF313 [73], RMF314 [73], RMF315 [73], RMF316 [73], RMF317 [73], RMF401 [73], RMF402 [73], RMF403 [73], RMF404 [73], RMF405 [73], RMF406 [73], RMF407 [73], RMF408 [73], RMF409 [73], RMF410 [73], RMF411 [73], RMF412 [73], RMF413 [73], RMF414 [73], RMF415 [73], RMF416 [73], RMF417 [73], RMF418 [73], RMF419 [73], RMF420 [73], RMF421 [73], RMF422 [73], RMF423 [73], RMF424 [73], RMF425 [73], RMF426 [73], RMF427 [73], RMF428 [73], RMF429 [73], RMF430 [73], RMF431 [73], RMF432 [73], RMF433 [73], RMF434 [73], Q1 [74], G1 [74], G2 [74], SMFT2 [75], DJM [75], S271 [76], Z271 [76], SRK3M5 [77], HD [78],HC [78], MS1 [79], MS3 [80], XS [80], NLSV1 [81], NLSV2 [81], TM1 [82], PK1 [83], hybrid [84], Z271* [85], G2* [85], BKA20 [86], BKA22 [86], BKA24 [86], FSUGOLD [9], FSUGOLD4 [87], FSUGOLD5 [87], FSUGZ00 [88], FSUGZ03 [88], FSUGZ06 [88], IU-FSU [89], NL3V1 [90], NL3V2 [90], NL3V3 [90], NL3V4 [90], NL3V5 [90], NL3V6 [90], S271V1 [90], S271V2 [90], S271V3 [90], S271V4 [90], S271V5 [90], S271V6 [90], Z271S1 [90], Z271S2 [90], Z271S3 [90], Z271S4 [90], Z271S5 [90], Z271S6 [90], Z271V1 [90], Z271V2 [90], Z271V3 [90], Z271V4 [90], Z271V5 [90], Z271V6 [90], TM1* [91], BSR1 [92], BSR2 [92], BSR3 [92], BSR4 [92], BSR5 [92], BSR6 [92], BSR7 [92], BSR8 [92], BSR9 [92], BSR10 [92], BSR11 [92], BSR12 [92], BSR13 [92], BSR14 [92], BSR15 [92], BSR16 [92], BSR17 [92], BSR18 [92], BSR19 [92], BSR20 [92], BSR21 [92], SVI-1 [93], SVI-2 [93], SIG-OM [94], NLρδ A [72], NLρδ B [72]);

(ii) Nine density-dependent RMF models (TW99 [95], DD-ME1 [96], PKDD [83], DD-ME2 [58], DD [97], DD-F [98], DD2 [99], DDMEδ [59], DDRHρδ [59]);

(iii)6 point-coupling RMF models (FA3 [57], FA4 [57], FZ3 [57], VZ3 [57], PC-F1 [55], PC-F3 [55]).

Equation of state of a neutron star

For different density regions of a neutron star, different forms of the EoS are employed in this paper as follows.

(i) For the outer crust of a neutron star, the EoS provided by Baym, Pethick, and Sutherland (BPS) [100] is adopted for densities in the range

(ii) For the inner crust,

(iii) In the liquid core region, also referred to as the outer core (OC) region, the density range is

(iv) For the neutron star inner core (IC) region at a high density (ρ > ρOC), studies have incorporated exotic particles such as hyperons, Δs, quarks, and dark matter into the core of massive neutron stars at densities exceeding 3ρ0 [104-115]. However, owing to the significant uncertainties in the interactions between nucleons and exotic particles (e.g., hyperons, Δs, and quarks), and the unclear composition of the neutron star core, a polytropic EoS is employed instead of explicitly modeling all possible exotic particles. In this paper, a piecewise polytropic EoS of the form

In summary, the EoS of neutron star matter is

Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkov equation

The structure of a neutron star is obtained by solving the TOV equation derived from General Relativity [119-121]. The TOV equations are

The in-spiral phase of the two merging neutron stars creates strong tidal gravitational fields, resulting in the deformation of the multipolar structure of the star. The deforming effects are quantified through the tidal deformability parameter Λ, which relates the induced mass quadruple moment

The dimensionless deformability Λ is defined as follows:

Results and discussions

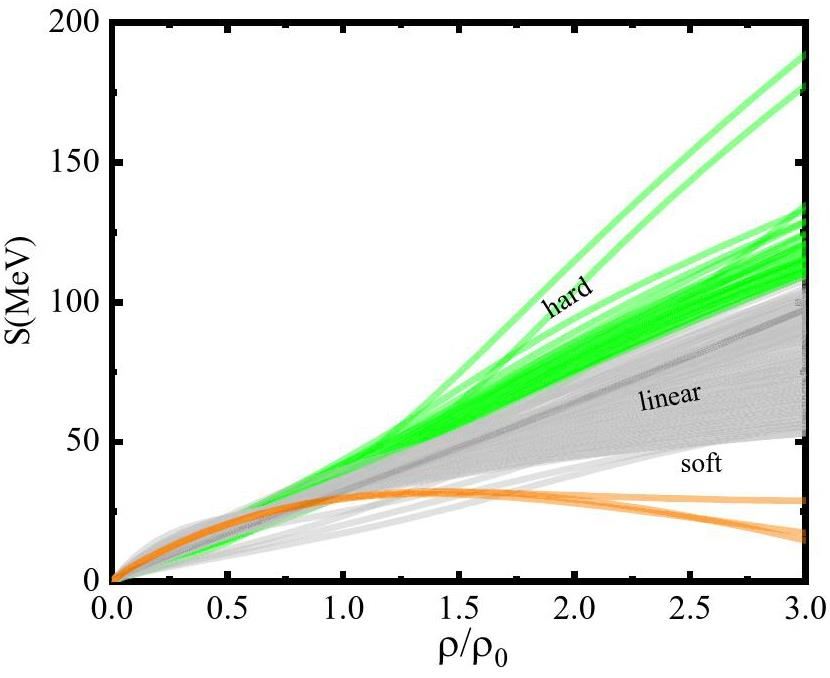

Generally, most RMF models are adjusted to describe nuclei and nuclear matter in the density region from near subsaturation density

In this paper, we use the observations of neutron stars to constrain the nuclear EoS at high densities

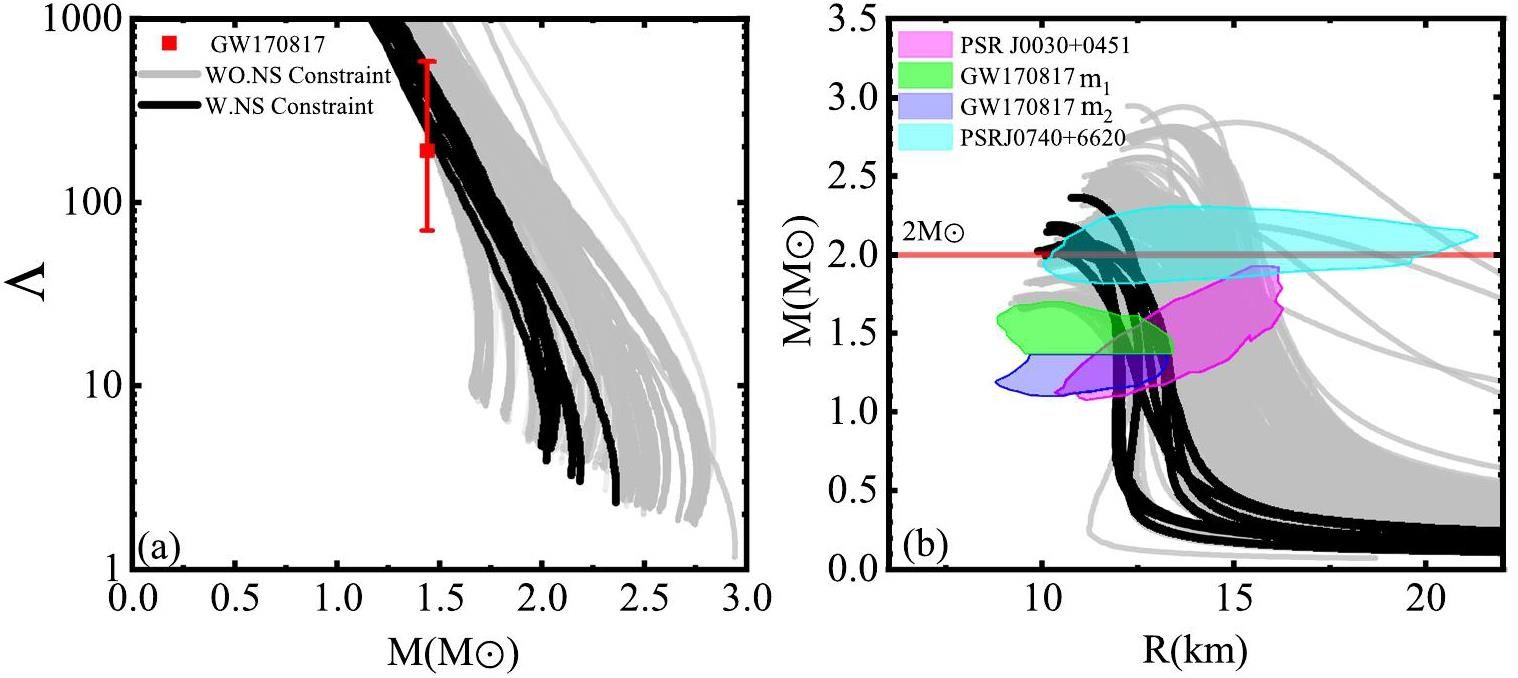

Our results for tidal deformability with the empirical values from GW170817 (red point) [41] are plotted in panel (a) of Fig. 2. The mass–radius relationship of neutron stars is shown in panel (b) of Fig. 2, where the pink shaded areas represent the region of the posterior distributions at 90% confidence the analysis from PSRJ0030+0451 [43], the blue shaded region is the posterior distribution at 95.4% confidence from PSR J0740+6620 [39], and the purple and green shaded areas denote the region of the posterior distributions at 90% confidence for GW170817’s lighter and heavier neutron stars [42], respectively. In Fig. 2, the gray lines represent the results for all the selected 180 RMF parameter sets, which are models without the constraint of the neutron star. With the constraint from the observables of neutron stars such as tidal deformability [41] and mass–radius relation around 1.4

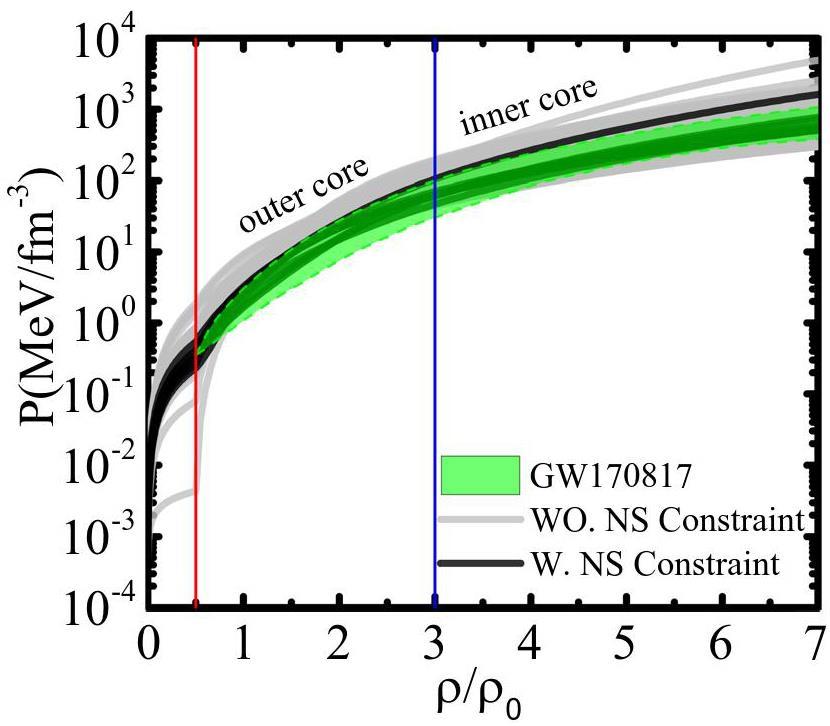

Figure 3 shows a comparison of the pressure–density relations between the empirical values from measurements of neutron stars and the RMF model calculations. The green shaded regions enclose the empirical pressure given by the “spectral” EoS inferred from the Bayesian analysis of the GW170817 data at a 90% confidence level, maintaining the lower limit of the maximum neutron star mass at 2

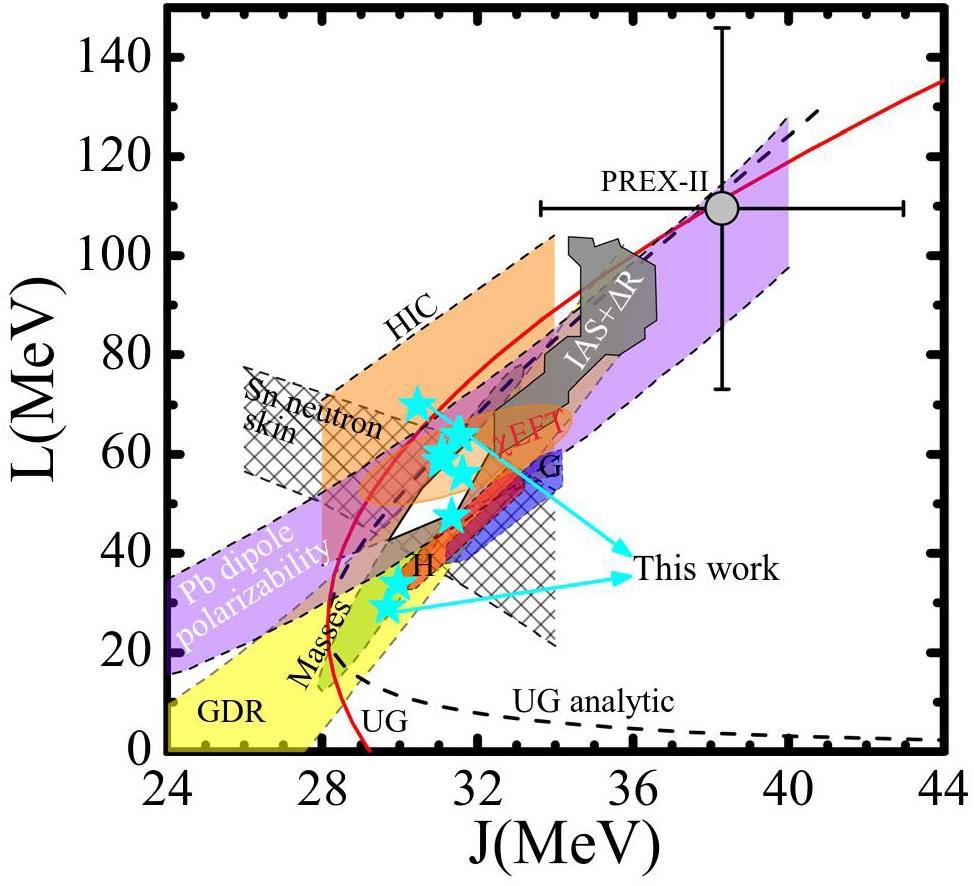

Figure 4 depicts the constraints on the J-L relation, which were compiled in [10, 130, 131]. In this paper, the symmetry energy J-L constraint from the neutron star observables based on the RMF models is shown as scattering points (cyan stars) with the range of symmetry energy at saturation

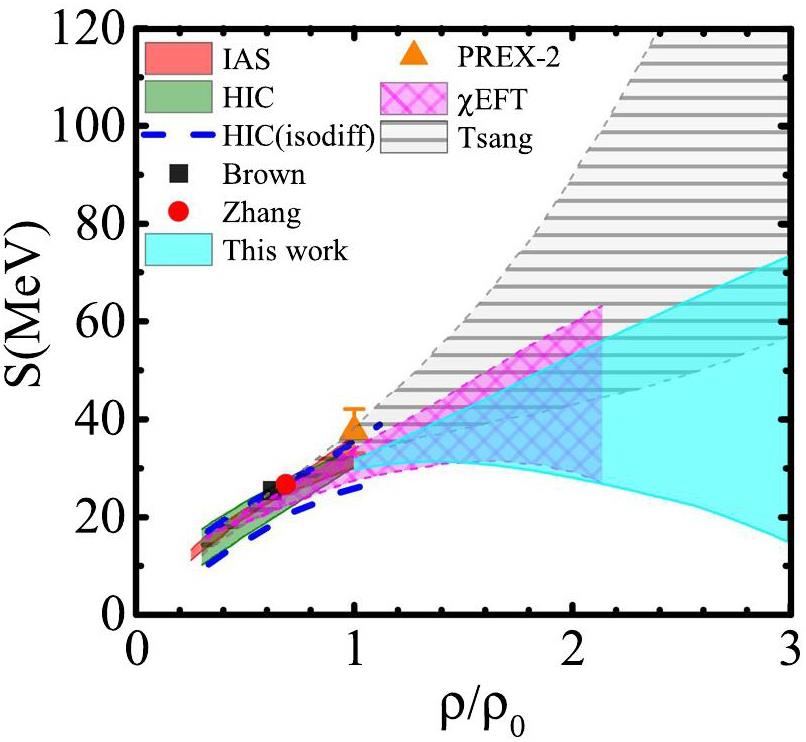

The symmetry energy at

Summary

We have extracted information on the symmetry energy at suprasaturation densities from astronomical observations using relativistic mean-field models. In this paper, we have employed 180 RMF parameter sets with incompressibility at the saturation density K0=200-300 MeV, which are suitable for describing the isoscalar monopole distribution strength in 209Pb. By combining the measurements of the 1.4 solar-mass neutron stars, such as tidal deformability (

In the next step, we will explore the entire parameter space of relativistic mean-field models using Bayesian inference with neutron star observational data, which can refine the parameter constraints and provide quantitative constraints on the EoS. Furthermore, the combination of constraints on the EoS from heavy-ion collision analyses (e.g.,

Isospin physics in heavy ion collisions at intermediate-energies

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 7, 147 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301398000087Determination of the equation of state of dense matter

. Science 298, 1592 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1078070The physics of neutron stars

. Science 304, 536 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1090720Neutron Star Observations: Prognosis for Equation of State Constraints

. Phys. Rep. 442, 109 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2007.02.003Isospin asymmetry in nuclei and neutron stars

. Phys. Rep. 411, 325 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2005.02.004Reaction dynamics with exotic beams

. Phys. Rep. 410, 335 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2004.12.004Recent progress and new challenges in isospin physics with heavy-ion reactions

. Phys. Rep. 464, 113 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2008.04.005Nuclear charge and neutron radii and nuclear matter: Trend analysis in Skyrme density-functional-theory approach

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Neutron-rich nuclei and neutron stars: A new accurately calibrated interaction for the study of neutron-rich matter

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95,How well do we know the neutron-matter equation of state at the densities inside neutron stars? A bayesian approach with correlated uncertainties

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125,Constraints on the density dependence of the symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,Density slope of the nuclear symmetry energy from the neutron skin thickness of heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 82,The Giant Dipole Resonance as a quantitative constraint on the symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 77,Complete electric dipole response and the neutron skin in 208Pb

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107,Electric dipole polarizability in 208Pb: Insights from the droplet model

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Nuclear energy density optimization

. Phys. Rev. C 82,The equation of state from observed masses and radii of neutron stars

. Astrophys. J. 722, 33 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/722/1/33The neutron star mass-radius relation and the equation of state of dense matter

. Astrophys. J. 765,Symmetry energy III: Isovector skins

. Nucl. Phys. A 958, 147 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2016.11.008Constraints on neutron star radii based on chiral effective field theory interactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,The maximum mass and radius of neutron stars and the nuclear symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Symmetry parameter constraints from a lower bound on neutron-matter energy

. Astrophys. J. 848, 105 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa8db9Neutron skins of atomic nuclei: per aspera ad astra

. J. Phys. G 46,Implications of PREX-2 on the equation of state of neutron-rich matter

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Circumstantial evidence for a soft nuclear symmetry energy at suprasaturation densities

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,A Systematic study of the pi-/pi+ ratio in heavy-ion collisions with the same neutron/proton ratio but different masses

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Symmetry energy and pion production in the Boltzmann-Langevin approach

. Phys. Lett. B 718, 1510 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.12.021Probing high-density behavior of symmetry energy from pion emission in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 683, 140 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.12.006Isospin-dependent pion in-medium effects on charged pion ratio in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 81,The impact of energy conservation in transport models on the π-/π+ multiplicity ratio in heavy-ion collisions and the symmetry energy

Phys. Lett. B 753, 166 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2015.12.015Modifications of the pion-production threshold in the nuclear medium in heavy ion collisions and the nuclear symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Symmetry energy from elliptic flow in 197Au+197Au

. Phys. Lett. B 697, 471 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2011.02.033Toward a model-independent constraint of the high-density dependence of the symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Relativistic Shapiro delay measurements of an extremely massive millisecond pulsar

. Nature Astronomy 4, 72-76 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0880-2Refined mass and geometric measurements of the high-mass PSR J0740+6620

. Astrophys. J. Lett. 915,GW190814: Gravitational waves from the coalescence of a 23 solar mass black hole with a 2.6 solar mass compact object

. Astrophys. J. Lett. 896,Towards understanding astrophysical effects of nuclear symmetry energy

. Euro. Phys. J. A 55, 117 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12780-8GW190814: Impact of a 2.6 solar mass neutron star on the nucleonic equations of state

. Phys.Rev.C 102,The radius of PSR J0740+6620 from NICER and XMM-Newton Data

. Astrophys. J. 918,Constraints on the phase transition and nuclear symmetry parameters from PSR J0740+6620 and multimessenger data of other neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Properties of the binary neutron star merger GW170817

. Phys. Rev. X 9,GW170817: Measurements of neutron star radii and equation of state

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Astrophys. PSR J0030+0451 Mass and Radius from NICER Data and Implications for the Properties of Neutron Star Matter

. Astrophys. J. Lett. 887,Bayesian inference of the symmetry energy of superdense neutron-rich matter from future radius measurements of massive neutron stars

. Astrophys. J. Lett. 899, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aba271Constraints on the symmetry energy and its associated parameters from nuclei to neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Equation of state constraints from nuclear physics, neutron star masses, and future moment of inertia measurements

. Astrophys. J. Lett. 901, 155(2020). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/abaf55Determination of the equation of state from nuclear experiments and neutron star observations

. Nature Astronomy 8, 328 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-023-02161-zInsights on Skyrme parameters from GW170817

. Phys. Lett. B 796, 1-5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.05.055Progress in constraining nuclear symmetry energy using neutron star observables since GW170817

. Universe 7, 182 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/universe7060182Impact of the neutron-star deformability on equation of state parameters

. Phys. Rev. C 102,The relativistic mean field description of nuclei and nuclear dynamics

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 52, 439 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/52/4/002Relativistic mean field in finite nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys 37, 193 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6410(96)00054-3Relativistic mean-field hadronic models under nuclear matter constraints

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Recent progress in quantum hadrodynamics

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 6, 515 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301397000299Nuclear ground state observables and QCD scaling in a refined relativistic point coupling model

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Density dependent hadron field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 3043 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.3043Relativistic point coupling models as effective theories of nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 627, 495 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)00598-8New relativistic mean-field interaction with density-dependent meson-nucleon couplings

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Relativistic mean field interaction with density dependent meson-nucleon vertices based on microscopical calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Correlating the giant monopole resonance to the nuclear matter incompressibility

. Phys. Rev. C. 66,Optimal parametrization for the relativistic mean-field model of the nucleus

. Phys. Rev. C 38, 390 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.38.390A New parametrization for the Lagrangian density of relativistic mean field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 55, 540 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.55.540The effective force NL3 revisited

. Phys. Lett. B 671, 36 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2008.11.070A New parameter set for the relativistic mean field theory

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 13, 75 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301304001758Structure of exotic nuclei and superheavy elements in a relativistic shell model

. Phys. Rev. C 63,The nonlinearity of the scalar field in a relativistic mean-field theory of the nucleus

. Z. Phys. A 329, 257 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01290231Nilsson parameters kappa and mu in the relativistic mean field models

. Phys. Rev. C 71,The hyperon composition Of neutron stars

. Phys. Lett. B 114, 392 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(82)90078-8Reconciliation of neutron star masses and binding of the lambda in hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 2414 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.67.2414Quark hadron phase transition and hybrid stars

. Z. Phys. A 352, 457 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01299764Neutron stars with the isovector scalar field

. Eur. Phys. J. A 25, 293 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2005-10095-1Parametrization of the relativistic (σ−ω) model for nuclear matter

Phys. Rev. C 82,A chiral effective lagrangian for nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 615, 441 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(96)00472-1Finite-nuclei calculations based on relativistic mean-field effective interactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 547, 447 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(92)90032-FNeutron star structure and the neutron radius of Pb-208

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5647 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.5647Semiclassical approximations in nonlinear sigma omega models

. Nucl. Phys. A 537, 486 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(92)90365-QAsymmetric nuclear matter in the relativistic mean field approach with vector cross interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Phase transitions in warm, asymmetric nuclear matter

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 2072 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.2072Relativistic models of the neutron-star matter equation of state

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Shell effects in nuclei with vector selfcoupling of omega meson in relativistic Hartree-Bogolyubov theory

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Relativistic mean field theory for unstable nuclei with nonlinear sigma and omega terms

. Nucl. Phys. A 579, 557 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90923-7New effective interactions in RMF theory with nonlinear terms and density dependent meson nucleon coupling

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Incompressibility of neutron-rich matter

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Low densities instability of relativistic mean field models

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Asymmetric nuclear matter and neutron-skin in extended relativistic mean field model

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Insensitivity of the elastic proton-nucleus reaction to the neutron radius of Pb-208

. Nucl. Phys.A 778, 10 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2006.08.004Effects of omega meson self-coupling on the properties of finite nuclei and neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Relativistic effective interaction for nuclei, giant resonances, and neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Constraining URCA cooling of neutron stars from the neutron radius of Pb-208

. Phys. Rev. C 66,Effects of new nonlinear couplings in relativistic effective field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 63,Non-rotating and rotating neutron stars in the extended field theoretical model

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Scalar-vector Lagrangian without nonlinear self-interactions of bosonic fields in the relativistic mean-field theory

. Phys. Lett. B 666, 140 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2008.07.005Sigma-omega meson coupling and properties of nuclei and nuclear matter

. Nucl. Phys. A 803, 159 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.02.296Relativistic mean field calculations with density dependent meson nucleon coupling

. Nucl. Phys. A 656, 331 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(99)00310-3Relativistic Hartree-Bogolyubov model with density dependent meson nucleon couplings

. Phys. Rev. C 66,Relativistic model for nuclear matter and atomic nuclei with momentum-dependent self-energies

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Constraints on the high-density nuclear equation of state from the phenomenology of compact stars and heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Composition and thermodynamics of nuclear matter with light clusters

. Phys. Rev. C 81,The Ground state of matter at high densities: Equation of state and stellar models

. Astrophys. J. 170, 299 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1086/151216Pulsar constraints on neutron star structure and equation of state

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 3362 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.3362Low mass neutron stars and the equation of state of dense matter

. Astrophys. J. 593, 463 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1086/376515Core-crust transition in neutron stars: predictivity of density developments

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Strange quark matter and compact stars

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 54, 193 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2004.07.001Exotic phases in neutron stars

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 17, 1635 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301308010659Quark deconfinement in high-mass neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Strangeness in nuclear physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88(3),Strangeness in nuclei and neutron stars

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 112,Equations of state for supernovae and compact stars

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89(1),Too massive neutron stars: The role of dark matter?

. Astropart.Phys. 37, 70 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.astropartphys.2012.07.006Neutron star matter with Δ isobars in a relativistic quark model

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Effects of dark matter on the nuclear and neutron star matter

. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc., 495, 4893 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa1435Hyperon puzzle: hints from quantum Monte Carlo calculations

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114,Extracting the hyperon-nucleon interaction via collective flows in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 851,Correlation of the hyperon potential stiffness with hyperon constituents in neutron stars and heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 853Constraints on a phenomenologically parameterized neutron-star equation of state

. Phys. Rev. D. 79,The Equation of State of Hot, Dense Matter and Neutron Stars

. Phys. Rep. 621, 127 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.12.005Constraining the high-density behavior of the nuclear symmetry energy with the tidal polarizability of neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. C 87Static solutions of Einstein’s field equations for spheres of fluid

. Phys. Rev. 55, 364 (1939). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.55.364On massive neutron cores

. Phys. Rev. 55, 374 (1939). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.55.374Relativistic tidal properties of neutron stars

. Phys. Rev. D 80,Tidal deformability of neutron stars with realistic equations of state and their gravitational wave signatures in binary inspiral

. Phys. Rev. D 81,Tidal love numbers of neutron and self-bound quark stars

. Phys. Rev. D 82,Neutron radii in mean field models

. Nucl. Phys. A 706, 85 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(02)00867-9Nuclear symmetry energy and core-crust transition in neutron stars: a critical study

. Europhys. Lett. 91, 32001 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/91/32001Constraining the symmetry energy at subsaturation densities using isotope binding energy difference and neutron skin thickness

. Phys. Lett. B 726, 234 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.08.002A way forward in the study of the symmetry energy: experiment, theory, and observation

. J. Phys. G 41,Relativistic description of dense matter equation of state and compatibility with neutron star observables: a bayesian approach

. Astrophys.J. 930, 17 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ac5d3cConstraints on the symmetry energy using the mass-radius relation of neutron stars

. Eur. Phys. J. A 50, 40 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2014-14040-yConstraining the symmetry parameters of the nuclear interaction

. Astrophys. J. 771, 51 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/771/1/51Isospin-dependent properties of asymmetric nuclear matter in relativistic mean-field models

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Constraints on the skyrme equations of state from properties of doubly magic nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111,Symmetry energy II: isobaric analog states

. Nucl. Phys. A 922, 1-70 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2013.11.005Constraining the density slope of nuclear symmetry energy at subsaturation densities using electric dipole polarizability in 208Pb

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Chiral interactions up to next-to-next-to-next-to-leading order and nuclear saturation

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Quantifying uncertainties and correlations in the nuclear-matter equation of state

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Probing the Symmetry Energy with Heavy Ions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 62, 427 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2009.01.001Incompressibility of Nuclear Matter from the Giant Monopole Resonance

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 691 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.691The authors declare that they have no competing interests.