Introduction

L-forbidden M1 transitions have been reported in many odd-mass nuclei, involving pairs of low-lying excited and ground states of single particle nature with the orbital angular momenta differing by two units, such as g7/2-d5/2, s1/2-d3/2, and p3/2-f5/2 [1]. The corresponding orbitals are typically close to each other outside the shell closure. In principle, the M1 transition between them is forbidden. The observation of these non-zero transition strengths indicates the M1 transition of L-forbidden nature beyond a single-particle scheme.

The effective g-factor is necessary to explain the observed magnetic momentum or M1 transition strength. From a physics perspective, such effective operators originate from core polarization and the meson exchange effect [2, 3]. Compared with the spin and orbital terms, the tensor term of the effective M1 operator is almost negligible when a magnetic momentum is produced, as mentioned in Refs. [2-4]. However, in the L-forbidden M1 transition, the tensor term (

Meanwhile, the core-excitation, especially when crossing Z = 50 or N = 50 shells [5, 6], increases the number of single-particle orbitals contributing to the M1 transition. However, the quantitative influence of the core polarization effect on the effective g-factor has not yet been elucidated, particularly the tensor term. The L-forbidden M1 transitions in odd-mass isotopes along the N = 82 isotonic chain are potential tools for investigating an effective M1 operator.

The adopted lifetime of the first excited state in 139La [7] was determined in previous experiments conducted using the β decay channel from either 139La or 139Ce. However, because of material limitation, most experiments use two stilbene scintillators to measure the time differences between β-rays and conversion electrons, yielding a half-life of 1.50(10) ns in both cases Refs. [8, 9]. An alternative method is using stilbene and plastic crystals to measure the time difference between conversion electrons and KX-rays, as mentioned in Refs. [10, 11], yielding half-lives of 1.47(6) ns and 1.60(4) ns, respectively. Although the aforementioned experiments employed the best available instruments, the lack (or insufficiency) of energy-resolving power limited the operations of the detectors, accounting for possible uncertainties in the background subtraction. Currently, LaBr3 detectors are widely used for γ-ray spectroscopy [12-15]. Owing to its excellent time and energy resolution, the LaBr3 detector together with plastic scintillators is a potential tool for determining the lifetime of the first excited state in 139La via β–γ time-difference measurement, an operation that was previously impossible. This novel measurement technique could eliminate the γ-ray background and be applied to investigate complex β-decay channels. Moreover, it could analyze radioactive isotopes such as 133Sn, 135Te, and 137Xe or determine the lifetime of the first excited states in 133Sb, 135I, and 137Cs via β–γ time-difference measurement.

This study experimentally performed β–γ measurement to determine the first excited state in 139La using LaBr3 and plastic scintillators. Based on the experimental results, a comprehensive shell-model study on the L-forbidden M1 transition was conducted, focusing on the effect of core-excitation. Experimental details and results are presented in Sect. 2, and the discussion is presented in Sect. 3.

Experimental Setup and Result

The experiment was conducted using the Back-n white neutron beamline [16-21] located at the China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS) [22]. The Back-n beamline uses backstreaming white neutrons from the spallation target at CSNS, delivering an intense flux of over ~ 107cm-2s-1 at the experimental hall, which is 55 m away from the spallation target. With a proton beam power of 100 kW, the Back-n neutron energy ranges from 0.3 eV to several hundreds of megaelectron volts. Three natural Ba targets (71.689% of 138Ba) with diameters of 30 mm were placed on the beamline; one target was 3-mm thick, and the others were 5 mm-thick.

During irradiation, 139Ba was mainly produced in the 138Ba(n,γ) reaction. Given that the β-decay half-life of 139Ba is 82.93 ± 0.09 minutes [7], the irradiation time on the beamline was approximately 4 h. After irradiation, the beam was stopped and the targets were displaced to another location for off-beam decay measurement, which lasted 4 h; after which, all the samples were irradiated for 4 h. The procedure was repeated several times. In this experiment, both the irradiation and measurement times were 20 h.

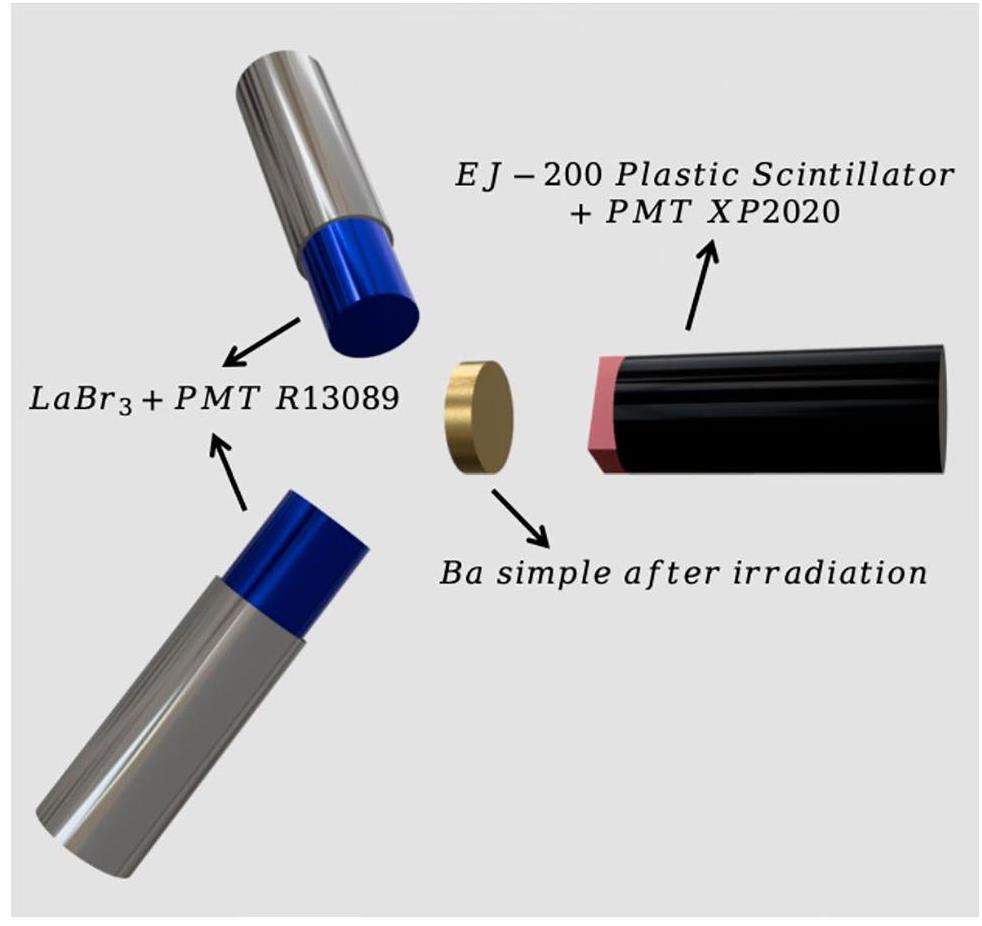

As shown in Fig. 1, for off-line measurement, one plastic scintillator and two LaBr3 detectors were installed on the samples to detect β and γ rays, respectively. A 2 mm-thick EJ-200 plastic scintillator of size 3 cm×4 cm, coupled with XP2020 photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), was used. The crystal of each LaBr3 has a diameter of 2 in (50.8 mm) and length of 3 in (76.2 mm). The signal from each LaBr3 crystal was captured using Hamamatsu PMT R13089, whose anode output has a typical rise time of 2 ns, suitable for fast-timing measurement. The signals from all three detectors were transmitted to a Pixie-16 module from XIA LLC, which is a 14-bit 500 MHz Digital Pulse Processor [23]. To improve the time resolution, a CFD algorithm was applied to detect the zero-crossing of a pulse by subtracting the scaled and delayed copies of the fast-filter pulse in the general-purpose digital data acquisition system (GDDAQ) developed by Peking University. Detailed information on GDDAQ and related CFD logic can be obtained in Ref. [23],

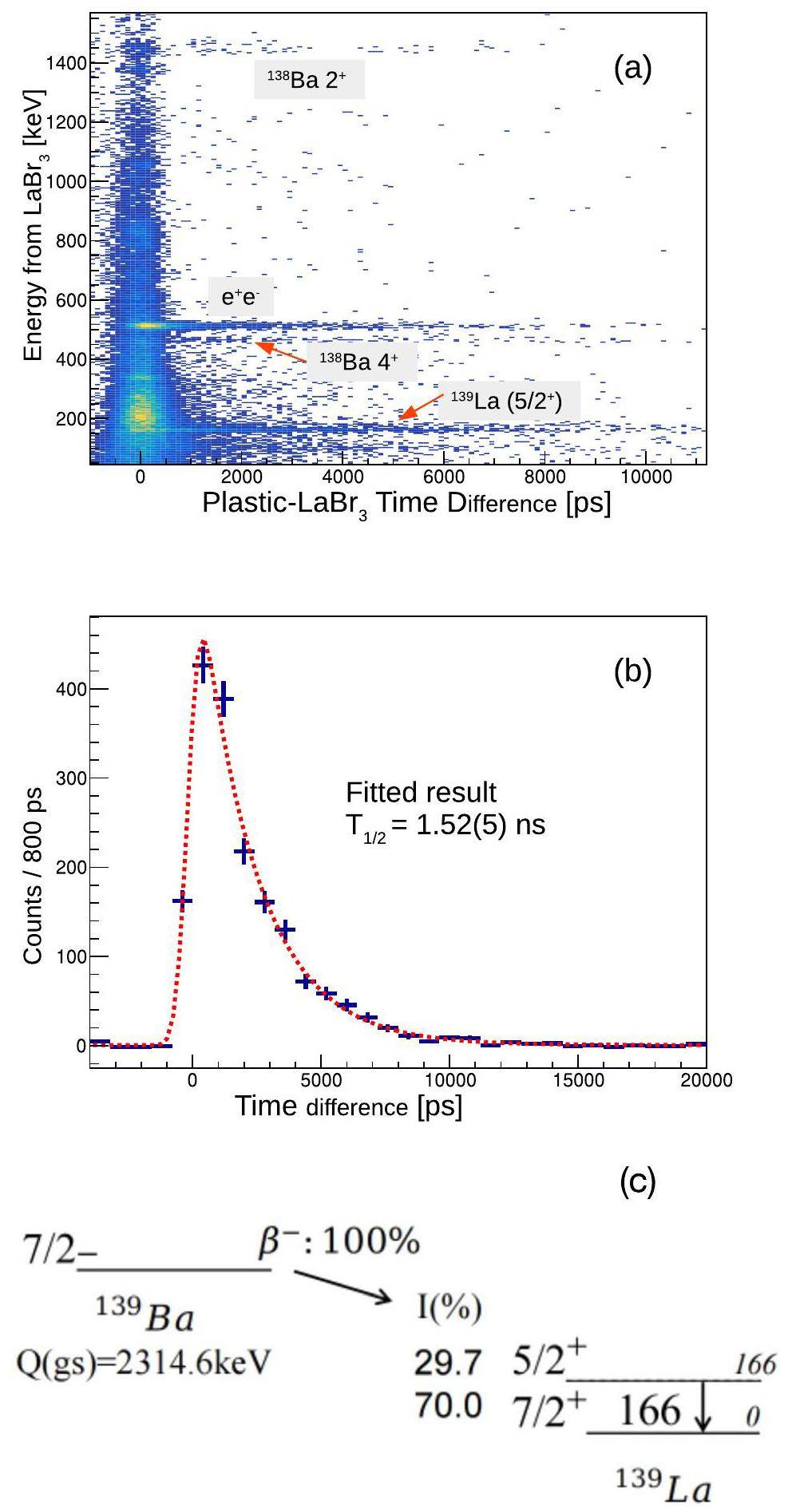

Figure 2(a) shows a two-dimension plot of the β–γ time difference vs γ-ray energy. Following the β decay, three γ lines at 166, 462, and 1436 keV were observed in addition to the 511 keV transition, corresponding to the decay of the first excited state in 139La [7] and

When high-energy neutrons impinge on 138Ba, 139Ba is produced with an excitation energy higher than the proton separation energy (9316(9) keV [7]), producing 138Cs using proton evaporation channels. The ground state of 138Cs has a β-decay half-life of 32.5(5) min [24] and most of the β-decay branches feed on excited states higher than the

The following paragraph focuses on the 139Ba → 139La β-decay channel. The β-decay channel has been extensively investigated [7-11]. The branching ratio information reveals that approximately 70% would directly populate the ground state in 139La without emitting γ rays. The strongest among the remaining branches feeds the first excited state in 139La with a ratio of 29.7 %, and all the remaining branches only account for 0.3 % of the decay strength. Consequently, most of the measured β–γ coincidence events are related to the ground state of 139Ba β decay to the

The fitting function includes the contributions of both prompt response functions and the exponential decay component. Detailed information about the fitting can be obtained in Ref. [15] and references therein. In the current experiment, owing to the excellent energy resolution of LaBr3, the 166-keV transition can easily be selected, facilitating background subtraction, as shown in Fig. 2, an operation that was impossible in the 1960s.

Shell-Model Investigation and Discussion

Shell model calculations have been performed to investigate the nature of the L-forbidden M1 transition in 139La. To examine the effect of core-excitation, the model space comprises π 0g9/2, 0g7/2, 1d5/2, 1d3/2, 2s1/2, 0h11/2 and ν 0h11/2, 0h9/2, 1f7/2, 1f5/2, 2p3/2, 2p1/2, 0i13/2 orbitals. The proton (neutron) core-excitation across the Z = 50 (N = 82) shell can be achieved by exciting protons (neutrons) from the π 0g9/2 (ν 0h11/2) orbital to higher orbitals.

The effective Hamiltonian is based on the nuclear force VMU+LS [26], which comprises a Gaussian central force, a π + ρ meson-exchange tensor force, and an M3Y spin-orbit force [27]. The VMU+LS force has been employed in the psd [28], sdpf [29], pfsdg regions [30], and nearby regions around 132Sn [31, 32] and 208Pb [4, 33-35]. Recently, VMU+LS had been employed to investigate the level structure of nuclei around 132Sn and 208Pb [36, 37] in a unified manner. Specifically, the separation and excitation energies, as well as the nuclear level densities of

1. Influence of effective g-factor on lifetime prediction

In this study, B(M1) calculation employed effective g-factors of

The theoretical predictions of the

| Core-excitation | B(M1) [ |

B(E2) [e2fm4] | B(M1)* [ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 2.2×10-5 | 309.8 | 0.938 | 142.3 | 97.5 | 1.5×10-3 | 4.5 |

| p1 | 6.9×10-4 | 9.9 | 0.478 | 279.5 | 9.5 | 3.5×10-3 | 1.9 |

| n1 | 2.8×10-4 | 24.6 | 0.802 | 166.5 | 21.5 | 2.5×10-3 | 2.7 |

| p1n1 | 1.3×10-3 | 5.4 | 0.348 | 383.9 | 5.3 | 4.6×10-3 | 1.5 |

The calculation in the previous paragraph did not include the tensor term in the effective g-factor [43, 44]. Meanwhile, the tensor part, exhibiting a slight influence on the magnetic moments around the 132Sn region, as reported in Ref. [41, 42], is essential for the L-forbidden M1 transition strength because the

2. Detailed investigation on M1 matrix element

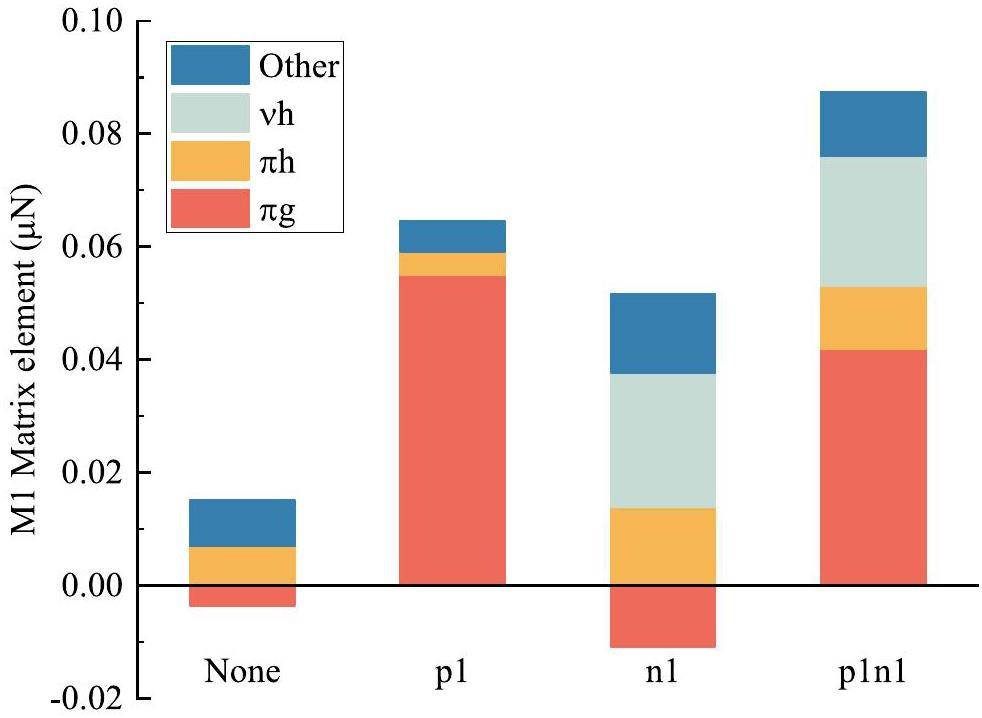

Furthermore, we analyzed the difference in the M1 matrix element, particularly for the high-J component, between different core-excitation conditions. The decomposition of the M1 matrix element is shown in Fig. 3. First, the inclusion of proton core-excitation significantly enhances the contribution from the π g7/2 and g9/2 shells.

Neutron core-excitation introduces a strong component from νh orbitals similarly. In the one-proton-one-neutron core-excitation condition, all the corresponding components are available, whereas the major components originate from the spin-flip orbitals on both sides of the Z = 50 (g7/2 and g9/2) and N = 82 (h11/2 and h9/2) shells.

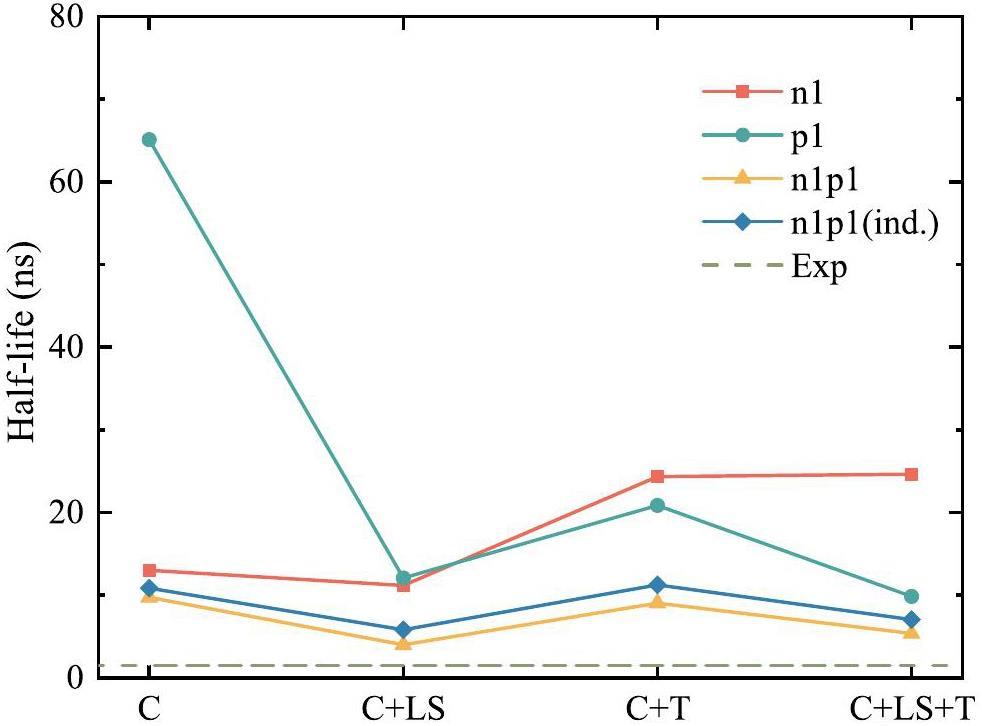

Herein, we aim to investigate the influence of the different components, including central, spin-orbit, and tensor parts, of effective interaction on the M1 transition strength, as shown in Fig. 4. The different nuclear-force components exhibited different behaviors with changes in the core-excitation truncation. In the p1 case, introducing the central force increases the half-life of the

The significant difference between the p1 and n1 cases indicates that the tensor and spin-orbit forces contribute differently in both cases. This was unexpected because, as shown in Fig. 3, within the M1 matrix element, the πg component exhibits constructive and deconstructive interference with the other components in the p1 and n1 cases, respectively. Moreover, the νh component exists in the n1 case but not in the p1 condition, initiating a different situation when spin-orbital or tensor forces are generated. This observation is supported by the n1p1 case, in which the νh component is also a dominant contributor among the matrix elements, and the calculated half-life does not change significantly when spin-orbit and tensor forces are generated; a situation that is similar to the n1 case.

The n1p1(ind.) case, which is evaluated by considering n1 and p1 as independent branches, estimates an overall longer half-life than the "n1p1" condition. However, both cases exhibit similar tendencies. This implies that a consistent interference would be observed between the proton and neutron core-breaking components and that such an interference term between the proton and neutron configurations would not be sensitive to the nuclear force component. Changes in M1 transition strengths with respect to various nuclear forces reflect the modification of effective single-particle energies to adjust the configurations for both

Conclusion

This study measured the lifetime of the first excited state in 139La using a state-of-the-art LaBr3 + plastic scintillator array in a digital data-acquisition system. Compared with previous measurements that used stilbene or plastic scintillators, the proposed measurement effectively separates the background contribution in the gamma line spectrum owing to the high energy resolution of LaBr3. To measure the lifetime of the (

Systematics of l-forbidden m1 transitions

. Nucl. Phys. 60, 666-671 (1964). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(64)90102-6Magnetic multipole moments and transition probabilities of single-particle states around 208pb

. Nucl. Phys. A 209, 535-556 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(73)90845-2Shell-model study on spectroscopic properties in the region “south” of 208Pb

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Novel shape evolution in sn isotopes from magic numbers 50 to 82

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,An alternative viewpoint on the nuclear structure towards 100Sn: Lifetime measurements in 105Sn

. Phys. Lett. B 845,Nuclear data sheets for A = 139

. Nucl. Data Sheets 138, 1-292 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2016.11.001The half-life of the 163 kev excited state in 139 Lanthanum

. Physica 21, 601-602 (1955). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-8914(55)90708-4Orbital momentum forbidden magnetic dipole transitions in some odd proton nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. 1, 281-301 (1956). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(56)90095-5Measurements of M1 and E2 transition probabilities in Te125, I127, Xe129, Cs133, La139 and Pr141

. Nucl. Phys. 68, 352-368 (1965). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(65)90652-8Adaptation of a long-lens beta-ray spectrometer for the measurement of short nuclear lifetimes

. Nukleonika 15, 649-59 (1970).Intrinsic background radiation of LaBr3(Ce) detector via coincidence measurements and simulations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 99 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00812-8Monte carlo simulation for performance evaluation of detector model with a monolithic LaBr3(Ce) crystal and sipm array for γradiation imaging

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 107 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01081-3New lifetime measurements in 109Pd and the onset of deformation at N=60

. Phys. Rev. C 92,A method for picosecond lifetime measurements for neutron-rich nuclei: (1) outline of the method

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 280, 49-72 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(89)91272-2Studies of back-streaming white neutrons at CSNS

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 621, 91-96 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2010.06.097Measurement of the neutron beam profile of the back-n white neutron facility at CSNS with a micromegas detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 957,Back-n white neutron source at CSNS and its applications

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00846-6Measurement of the neutron-induced total cross sections of natPb from 0.3 ev to 20 MeV on the back-n at CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01370-z10B-doped MCP detector developed for neutron resonance imaging at back-n white neutron source

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 142 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01512-3In-beam gamma rays of CSNS back-n characterized by black resonance filter

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01553-8China’s first pulsed neutron source

. Nat. Mater. 15, 689-691 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4655A general-purpose digital data acquisition system (GDDAQ) at Peking university

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 975,Nuclear data sheets for A=138

. Nucl. Data Sheets 146, 1-386 (2017).Novel features of nuclear forces and shell evolution in exotic nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,Interactions for inelastic scattering derived from realistic potentials

. Nucl. Phys. A 284, 399-419 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(77)90392-XShell-model study of boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes with a monopole-based universal interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Shape transitions in exotic si and s isotopes and tensor-force-driven jahn-teller effect

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Large-scale shell-model calculations for unnatural-parity high-spin states in neutron-rich Cr and Fe isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Isomerism in the "south-east" of 132Sn and a predicted neutron-decaying isomer in 129Pd

. Phys. Lett. B 762, 237 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.09.030Monopole effects, core excitations, and β decay in the A = 130 hole nuclei near 132Sn

. Chinese Phys. C 43,New alpha-emitting isotope 214U and abnormal enhancement of alpha-particle clustering in lightest uranium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,New isotope Th 207 and odd-even staggering in α-decay energies for nuclei with Z > 82 and N < 126

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Fine structure ofα decay in 222Pa

. Chinese Phys. C 45,Recent shell-model investigation and its possible role in nuclear structure data study

. EPJ Web of Conf. 239, 04002 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023904002Recent progress in configuration-interaction shell model

. Int. J Mod. Phys. E 23,Shell-model-based investigation on level density of xe and ba isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Quenching of spin matrix elements in nuclei

. Phys. Rep. 155, 263-377 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(87)90138-4Magnetic dipole moments near 132Sn: new measurement on 135I by NMR/ON

. Nucl. Phys. A 644, 277-288 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00597-1Magnetic moments of the 21+ states around 132Sn

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Core polarization for l-forbidden m1 transitions in light nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 351, 54-62 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(81)90544-3The authors declare that they have no competing interests.