Introduction

Super-iron elements originate from the current focal points in nuclear astrophysics. Over 98% of heavy elements are formed through the slow neutron capture process (s process) [1] and fast neutron capture process (r process) [2]. However, certain stable nuclides cannot be produced by either the s or r processes, containing more protons and separated from s and r nuclei by unstable isotopes between 74Se and 194Hg, collectively known as p-nuclei, with "p" representing proton- rich nuclides, totaling 35 nuclei in all [3]. Despite their rarity and low abundance, the synthesis of p-nuclei involves a wide range of nuclei. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the P-process mechanism to gain a comprehensive understanding of nucleosynthesis. Cross-sectional and structural studies of these 35 p-nuclei provided valuable insights into the p-process mechanism. To gain a more precise understanding of celestial nuclear processes and related element synthesis, it is essential to study the nuclear mass, reaction cross-section, and decay properties [4].

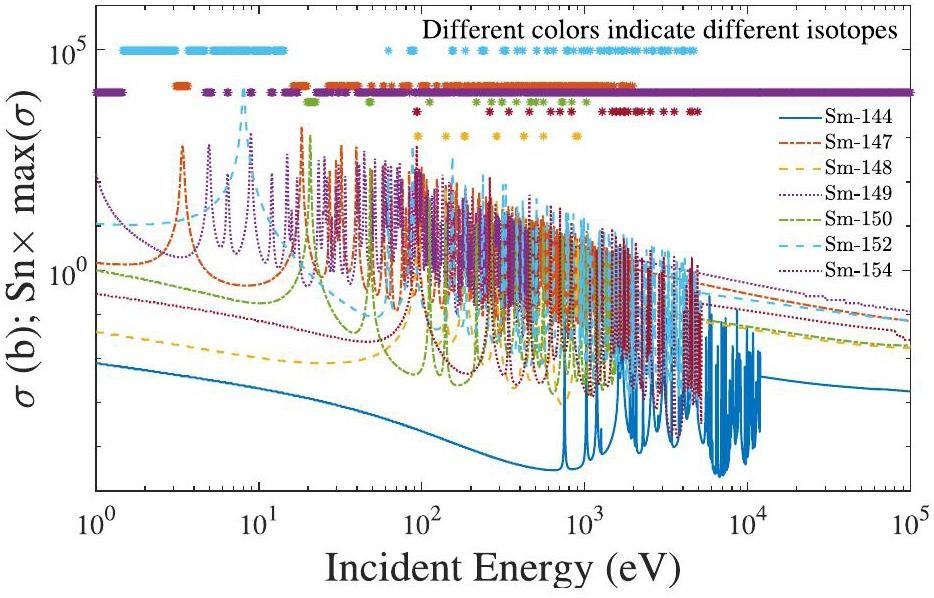

Natural Sm consists of eight stable isotopes, with 147,149Sm synthesized using the s process. Among these isotopes, 149Sm is exclusively produced by the s process because its stable neodymium isobars shield it from the contributions of the r process. The (n,γ) cross-sectional data for these isotopes provide valuable insights into the nucleosynthesis pathway in the samarium region. Furthermore, 235U is an important raw material for nuclear reactors [5]. As the operation of a nuclear reactor progresses, a multitude of fission-product nuclides are inevitably produced from the fission of fissile materials, such as 235U, some of which exhibit significantly high thermal neutron absorption cross-sections. Among these fission products, 149Sm, with a 1% yield from 235U fission, plays an important role in reactor neutronics because of its neutron-capture cross section [6].

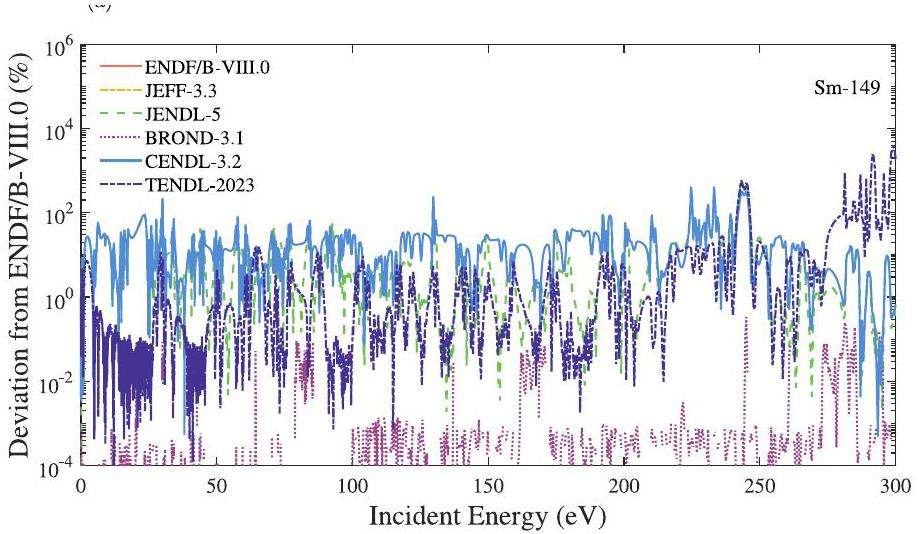

According to available nuclear evaluation databases such as ENDF B-VIII.0, CENDL-3.2, JENDL-4.0, JEFF-3.3, BROND-3.1, significant deviations were observed in the resonance peaks of the natSm (n,γ) cross-section data within the energy range of 1-300 eV. Figure 1 illustrates the deviation in neutron capture reaction data for 149Sm as reported in different evaluation databases compared to the ENDF/B-VIII.0 database. The deviation is calculated by

The China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS) is a large-scale multidisciplinary application platform based on high-power proton accelerators and is primarily utilized for material structure research through neutron scattering technology [7]. The CSNS accelerator comprises a 80 MeV hydrogen-negative-ion linear accelerator, a fast-cycle proton synchrotron accelerator with an energy of 1.6 GeV, and two proton beam transport lines [8]. The proton beam energy provided at the CSNS was 1.6 GeV, with a beam power of 100 kW(now in 180 kW) and a repetition frequency of 25 Hz. Tungsten targets of varying thicknesses were employed for the scattering reaction with protons, each wrapped in tantalum with a thickness of 0.5 mm and separated by cooling water layers measuring 1.5 mm [9, 10]. Upon impact of the proton beam on the tungsten target, the estimated neutron flux can reach 2.0×1016 cm-2s-1 [11-16].

In this study, the neutron capture cross-section of natural samarium was within the energy range of 20 to 300 eV at the back-streaming white neutron (Back-n) facility at the CSNS [17-22]. The natSm experiment was conducted in 2019, and a method that integrates a Monte Carlo simulation to ascertain the in-beam γ-ray background [23] was subsequently utilized to analyze samarium neutron capture cross-section data. The resonance parameters for each isotope within this energy range were derived using the SAMMY software. The experimental results clarified the differences in the 147,149Sm neutron resonance parameters in different evaluation databases under specific energies. For example, at 139.4 eV. The neutron resonance parameters Γn of the 147Sm isotope in the database of CENDL-3.2 and JENDL-4.0 are 69.1 meV, which is different from the ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.3, and BROND-3.1 databases; the values in these databases are uniformly 88 meV. The results of this study were 89.0 ± 8.8 meV. Additional results and detailed analyses are presented below.

Method and Material

Experimental Setup

A neutron capture experiment was conducted at end station 2 (ES#2) of the back-n beamline. The measurement utilized a detection system consisting of four C6D6 scintillation detectors, each with a diameter of 127 mm and length of 76.2 mm, housed within a 1.5-mm thick aluminum capsule, and coupled with a photomultiplier tube (ETEL 930 KEB PMT). For the measurement of the neutron capture reaction cross-section, the C6D6 detector offers several advantages [24]: (1) It exhibits low sensitivity to neutrons, which is crucial for eliminating background signals in the detection of the final state γ rays from the (n,γ) reaction. This insensitivity significantly reduces the neutron-induced background. (2) The C6D6 detector demonstrates a fast time response, with signal responses to neutrons and γ-rays on the order of nanoseconds. Coupled with the response time of the photomultiplier tube, this resulted in a rise time of approximately 10 ns for the entire anode signal, thereby improving the overall time resolution of the detection systems. (3) Through pulse height weighting technique (PHWT), the detection efficiency of C6D6 detectors can be independent of decay paths, multiplicity, and energy distribution of γ rays. The physical arrangement and Monte Carlo simulation reconstruction of the detector system and target are presented in Refs. [25], with the detailed layout parameters provided in Ref.[26]. The detector was placed opposite to the direction of the beam. This configuration minimizes the background interference from beam scattering, given that γ-rays emitted by neutron capture reactions are isotropic. The neutron flux was determined using a Li-Si detector based on the 6Li(n,α)3H reaction. The energy spectra were obtained from back-n collaboration, with an uncertainty of less than 8.0% for En < 0.15 MeV [27]. The Back-n data acquisition system (DAQ) employs a full-waveform data acquisition solution.

In this study, the TOF () method was used to determine the resonance energy of the neutrons. En is expressed as follows:

In the normal operating mode of a CSNS, there are two proton bunches with a time interval of 410 ns for each pulse, which has a repetition frequency of 25 Hz. Because of the superposition of the event distributions corresponding to the two bunches, the resolution of the TOF measurement at back-n is degraded by the double-bunch characteristics if the measured event distribution is used directly without unfolding, particularly in the higher neutron energy region [30]. In this study, we used the analytical method developed by the back-n collaboration to nearly recover the event distribution corresponding to a single proton bunch [31].

The experiment was conducted in May 2019 and involved the preparation of gold (197Au), carbon (natC), empty, and natural samarium (natSm) targets. A total beam time of approximately 49 h was used in this study. The 197Au(n,γ)198Au reaction, serving as a standard neutron capture cross section, was initially measured for 13 h at proton power levels ranging from 50.5–51.9 kW to validate previous findings [25], thereby ensuring the integrity of the experimental setup and data acquisition (DAQ). Subsequently, measurements were performed on the carbon and empty targets for 12 h and 8 h, respectively, to assess the neutron-scattering background and environmental interference under beam conditions. Throughout this period, the accelerator exhibited relatively stable performance with a beam power of approximately 50 kW and an uncertainty level below 2%. Finally, the natural samarium target was measured for 16 h at beam power levels between 48.3 and 50.5 kW. Details regarding the target parameters and measurement conditions are presented in Table 1, with diameter measurements obtained using Vernier calipers and the thickness determined by micrometer readings.

| Target | Impurities | Diameter (mm) | Thickness (mm) | Beam Power (kW) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| natSm | ω(Mo) = 0.002 % | ω(Tb) = 0.001 % | 50.00±0.02 | 1.000± 0.005 | 49.37±1.08 | |

| ω(Ca) = 0.005 % | ω(C) = 0.01 % | |||||

| ω (Si) = 0.01 % | ω(Mg) = 0.005 % | ω(Nb)=0.002 % | ||||

| ω(Al) = 0.005 % | ω(Cl) = 0.005 % | ω(Ta) = 0.002 % | ||||

| ω(La) = 0.001 % | ω(Ce)= 0.001 % | ω(Pr) = 0.002 % | ||||

| natC | < 0.100% | 50.00±0.02 | 1.000± 0.005 | 50.00±1.00 | ||

| 197Au | < 0.100% | 30.00±0.02 | 1.000± 0.005 | 51.20± 0.70 |

Weighting Function

The essence of data analysis is to obtain the counts of neutron capture reactions within the target, which are contingent on the detection efficiency and accuracy of the response of the detector to (n,γ) reactions. The efficacy of C6D6 scintillators in detecting prompt γ-ray cascades emitted during neutron capture reactions is contingent on the intricate de-excitation path of the compound nucleus. Consequently, it is imperative that the measured signals undergo the pulse-height weighting technique (PHWT), which renders the detection efficiency independent of the cascade γ-ray energies.

Typically, a high detection efficiency is sought after; however, for neutron capture reactions, a low detection efficiency is preferred owing to the phenomenon of γ radiation cascade emission. In the case of neutron-capture cascade emission, it is desirable to detect at most one γ ray in the cascade emission, making a low detection efficiency more suitable. Therefore, the detection efficiency of the capture reaction is approximately equal to the sum of the detection efficiencies of the capture reaction cascade γ.

For equation (4) to hold, it is necessary to perform mathematical control on the response function of the detection system to realize the relation in (3), which is a pulse-height weighting technique (PHWT). The PHWT was first proposed by Macklin and Gibbons and applied to the C6F6 detector to measure the neutron capture cross-section [32]. We anticipate that the energy of each group of cascaded γ-rays will be directly proportional to the weighted detection efficiency. The normalized detection efficiency manifests intuitively in the pulse-height spectrum (PH spectrum) counts. Consequently, the detection efficiency of the detector for γ can be characterized by analyzing the pulse-height spectrum. By introducing a weighted function number, we ensure that the following equation is satisfied:

The experimental capture yields were determined using a weighting function (WF) parameterized as a polynomial function of the γ-ray energy. WF can be expressed as

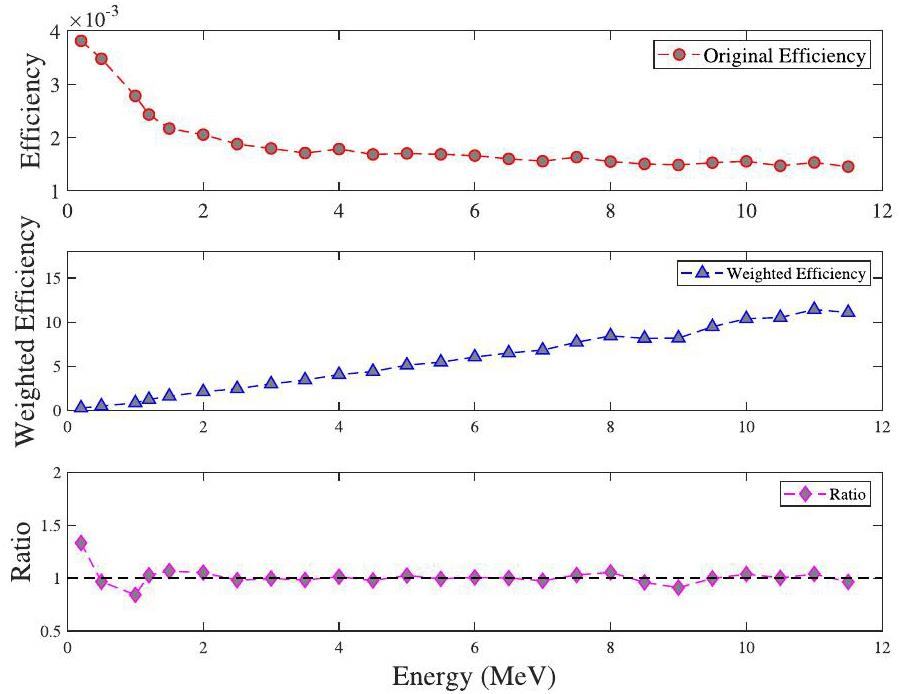

The energy deposition of different monoenergetic γ rays in the C6D6 detector layout [23] was simulated using the Geant4 Monte Carlo program [34, 35]. The original efficiency curves are presented in Fig. 2(a). Upon applying the weight function to the original efficiency curve, the linear relationship between the detection efficiency and energy is illustrated in Fig. 2(b), with the ratio of efficiency to energy in Fig. 2(c) approaching unity. Below 1.5 MeV, the weighted efficiency does not exhibit proportionality to the energy, necessitating the establishment of a threshold during PH spectrum processing to mitigate any impact from the failure of the weight function.

Background Analysis

To be effective, the WF must be applied to the net pulse-height spectrum. The key to obtaining the net pulse height spectrum is background deduction. For the neutron capture cross-section measurements with C6D6 detectors at back-n, the background composition was as follows [36]:

The background resulting from environmental activation and delayed γ rays is independent of the sample and time but relies solely on the experimental conditions. In this context, the background is determined by measuring an empty target without a beam to establish

The background caused by neutron scattering typically necessitates a target nucleus with a large neutron scattering cross section in the relevant energy range, while also requiring the neutron capture cross section of the target nucleus to be relatively flat to avoid interfering with the measurement of the Sm target. In this study, we used measurements of the carbon target under beam conditions to determine

In 2019, we failed to recognize the significance of the in-beam γ background, and consequently overlooked this aspect of the data. However, in 2022, we ascertained the general time structure of the in-beam γ background at the back-n facility using various in-beam γ ray experimental findings [23]. Subsequently, we propose a methodology for the comprehensive quantification of in-beam γ rays based on Geant4 simulation. By re-analyzing the 2019 natEr target experimental results using this approach, we obtained reliable outcomes that validated its efficacy. Furthermore, employing this method, we processed the 2019 natSm target experimental data to determine

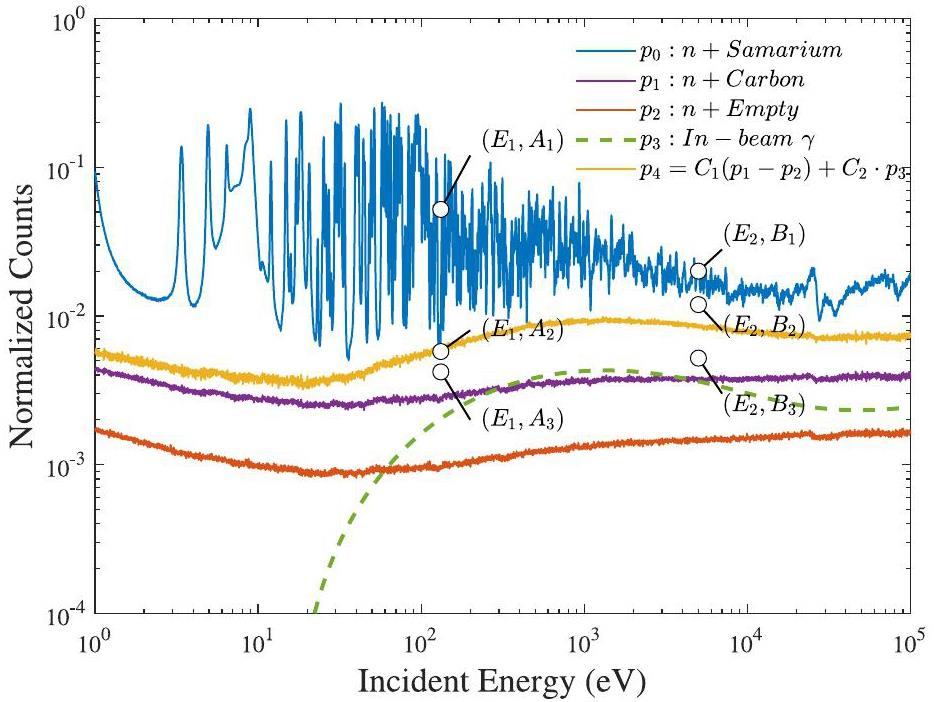

The normalized count spectrum is shown in Fig. 3. The lines

Let

Results and Discussion

Neutron Capture Yield

The net PH spectrum was derived by subtracting the background values. Following the application of WFs, the capture yield can be determined as follows:

Uncertainty

The uncertainty in the capture yield encompasses several contributing factors, as outlined in [26]: variability arising from the experimental conditions, data analysis, and statistical error.

The uncertainty arising from the experimental conditions includes variations in the energy spectrum and proton beam power, both of which directly affect the neutron flux at the target. This uncertainty is subsequently propagated into the yield through the term I in Eq. (9). According to the findings of the Back-n collaboration [27], the uncertainty associated with the energy spectrum in the Back-n ES#2 without a lead absorber ranges between 2.3% and 4.5% above 0.15 MeV and less than 8.0% below 0.15 MeV. The uncertainties stemming from the beam power are listed in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, in addition to Sm, the target material also contained trace quantities of other elements, and their contents varied from 0.001% to 0.01%. As the contents of these impurities are sufficiently low, their impact on the measurement results of the Sm neutron capture cross-section is less than 1%.

Uncertainties in the data analysis were primarily attributed to the PHWT method. In 2002, Tain et al. compared the neutron-width PHWT treatment results of a 1.15 keV peak in 56Fe with the experimental results, revealing a systematic error of 2.00%–3.00% [38]. This level of uncertainty can only be achieved if proper consideration is given to the threshold, conversion electrons, and γ-ray summing effects. Our simulation involved a complete reconstruction of the target and detector systems, while also incorporating a cascade γ emission program that included a model of the internal conversion processes. These efforts served to minimize additional uncertainty when applying PHWT to our results.

By contrast, the uncertainty stemming from the normalization method used to determine the absolute value of the term I in Eq. (9) affects the precision of the capture yield. The two normalization methods are provided in Refs. [26]: Gaussian fitting of one of the resonance peaks (typically, selecting the first peak in the experimental energy region for a natSm target is 3.4 eV). The normalized coefficient is calculated by comparing the fitted curve with evaluation data, and CENDL-3.2 database was utilized in this study. Another approach involves comparing energy bins individually. The normalized uncertainty varies for different targets and is less than 1.3%

The natSm experiment was concluded in 2019, and the experimental data for the in-beam γ-ray background were unfortunately not available. Therefore, we employed the methodology outlined in Ref. [36] to analyze the in-beam γ-ray background. The uncertainty within the energy range of 20–300 eV was less than 10.5%.

The statistical uncertainty of the experiment was less than 0.68%. All error sources and their estimates are summarized in Table 2.

| σ | Meaning | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Conditions | |||

| σ(BeamPower) | Uncertainty from beam power | see Table 1 | |

| σ(Target) | Uncertainty from impurities in the target | <1% | |

| σ(I2) | Uncertainty from energy spectra below 0.15 MeV | <8.00% | |

| Data Analysis | |||

| σ(PHWT) | Uncertainty from PHWT method | <3.00% | |

| σ(Normalized) | Uncertainty from normalized | <1.30% | |

| σ(In-Beam) | Uncertainty from counts of in-beam BKG | <10.5% | |

| Statistical error | |||

| σ(Statistic) | Uncertainty from mathematical statistics | <0.68% | |

Neutron Resonance Parameters

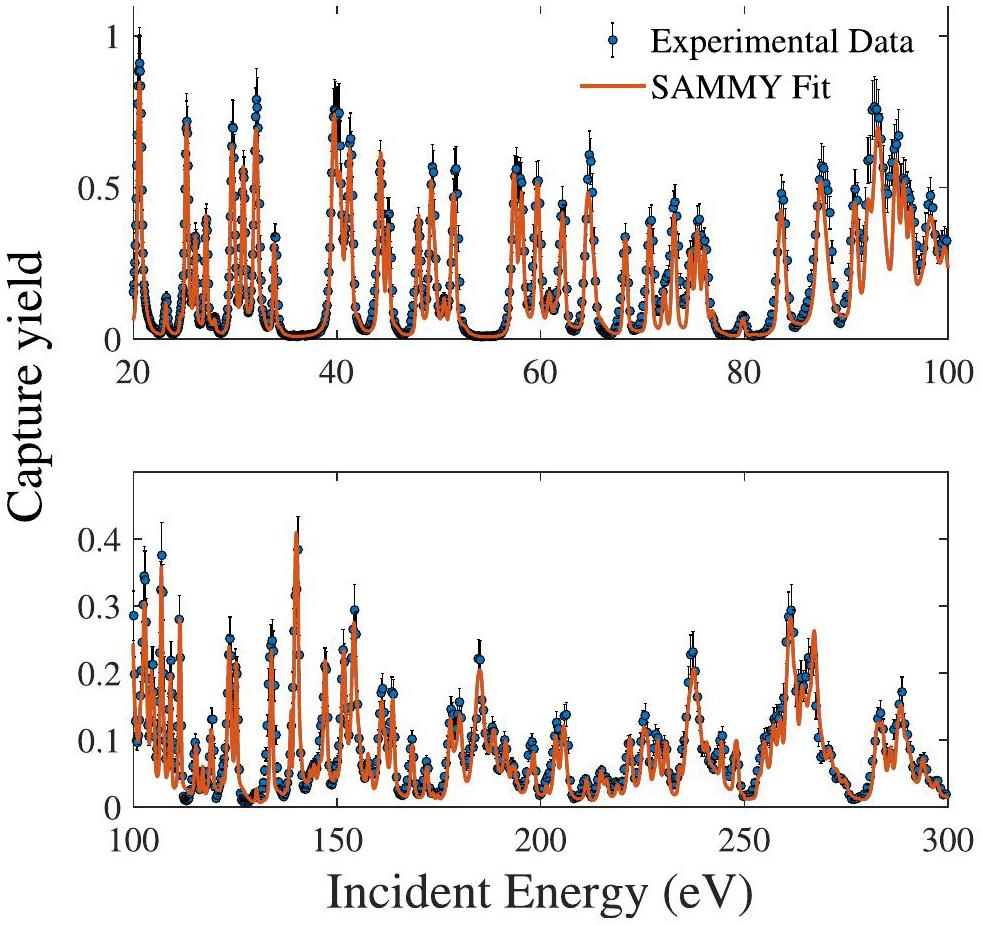

The neutron capture yield of a natural Sm target was measured within the resonance energy range of 1-300 eV. Capture yield data were obtained using Eq. 10 and subsequently fitted using the R-Matrix code SAMMY, accounting for various experimental effects such as Doppler broadening, self-shielding, and multiple scattering. The resonance parameters natSm(n,γ) were extracted accordingly. The fitting results are shown in Fig. 5. In the resonance energy region, each peak is attributed to a specific nuclide. Thus, the resonance information of each isotope can be extracted from the results of natural targets based on the resonance energy. Furthermore, Table 3 presents a detailed comparison of the differences between the different evaluation databases (DB#1-5 representing CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.3, JENDL-4.0, BROND-3.1).

| Mass | En (eV) | Γn | Γγ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present Work | DB#1 | DB#2 | DB#3 | DB#4 | DB#5 | Prensent Work | DB#1 | DB#2 | DB#3 | DB#4 | DB#5 | ||

| 147 | 107.0 | 46.8 ± 4.0 | 44.2 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 44.2 | 41.8 | 85.5 ± 8.0 | 69.0 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 82.0 | 82.0 |

| 139.4 | 89.0 ±8.8 | 69.1 | 88.0 | 88.0 | 69.1 | 88.0 | 72.9 ± 7.1 | 69.0 | 73.4 | 74.1 | 69.0 | 73.4 | |

| 241.7 | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 17.0 | 12.4 | 12.4 | 17.0 | 12.4 | 91.8 ± 9.2 | 69.0 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 91.0 | 91.0 | |

| 257.3 | 96.9 ± 6.5 | 73.0 | 98.3 | 98.3 | 73.0 | 98.3 | 78.1 ± 5.8 | 69.0 | 73.4 | 74.1 | 69.0 | 73.4 | |

| 149 | 23.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 0.9 | 7.9 | 73.8 ± 6.8 | 62.0 | 72.0 | 72.0 | 62.0 | 72.0 |

| 24.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 39.4 ± 3.9 | 62.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 62.0 | 40.0 | |

| 26.1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 51.7 ± 5.0 | 62.0 | 49.0 | 49.0 | 62.0 | 49.0 | |

| 28.0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 39.7 ± 4.0 | 62.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 62.0 | 40.0 | |

| 51.5 | 49.8 ± 3.2 | 42.3 | 41.8 | 41.8 | 42.3 | 41.8 | 70.2 ± 5.1 | 62.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 73.0 | 76.0 | |

| 75.2 | 26.5 ± 2.3 | 25.6 | 27.4 | 27.4 | 25.6 | 27.4 | 86.2 ± 8.4 | 62.0 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 85.0 | 85.0 | |

| 90.9 | 95.3 ± 8.8 | 84.1 | 83.6 | 83.6 | 84.1 | 83.6 | 83.1 ± 7.2 | 62.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 75.0 | |

| 125.3 | 36.4 ± 4.0 | 36.8 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 36.8 | 36.4 | 94.0 ± 9.8 | 62.0 | 94.0 | 94.0 | 94.0 | 94.0 | |

| 248.4 | 25.8 ± 2.6 | 39.7 | 36.6 | 36.6 | 39.7 | 36.6 | 82.0 ± 8.1 | 62.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 | 80.0 | |

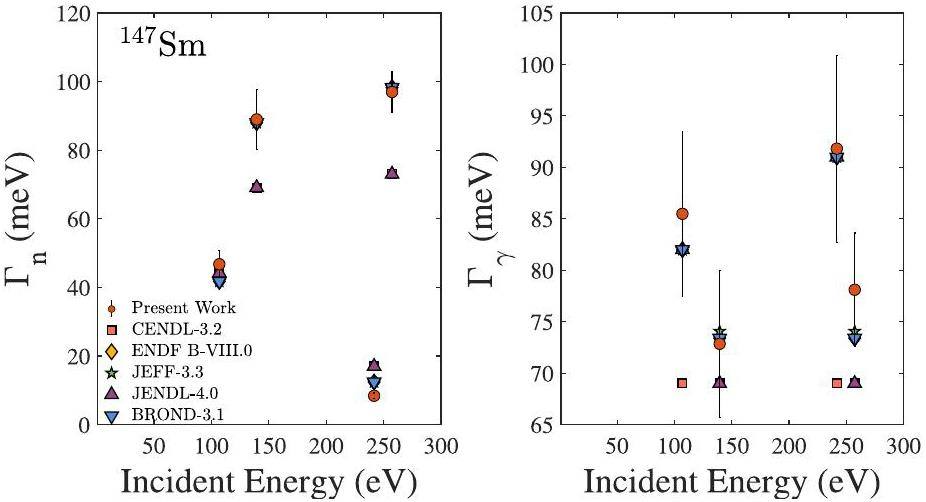

A comparison of the findings of the current study with those of various evaluation libraries is illustrated in Fig. 6 (147Sm) and Fig. 7 (149Sm). For the 147Sm isotope, the parameter Γn remains consistent at 107.0 eV across the different evaluation databases, and our experimental results agree with all of them. However, at the energy points of 139.4 eV, 241.7 eV, and 257.3 eV, the parameter Γn in the CENDL-3.2 database aligns with the JENDL-4.0 database but diverges from the ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.3, and BROND-3.1 For these energy points, our experimental results were consistent with the evaluations in the ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.3, and BROND-3.1 databases. The value of parameter Γγ for 147Sm in the CENDL-3.2 database is 69 meV at 107 eV compared to 82 meV in the other four databases; however, our current experimental result is 85.5 ± 8.0 meV.

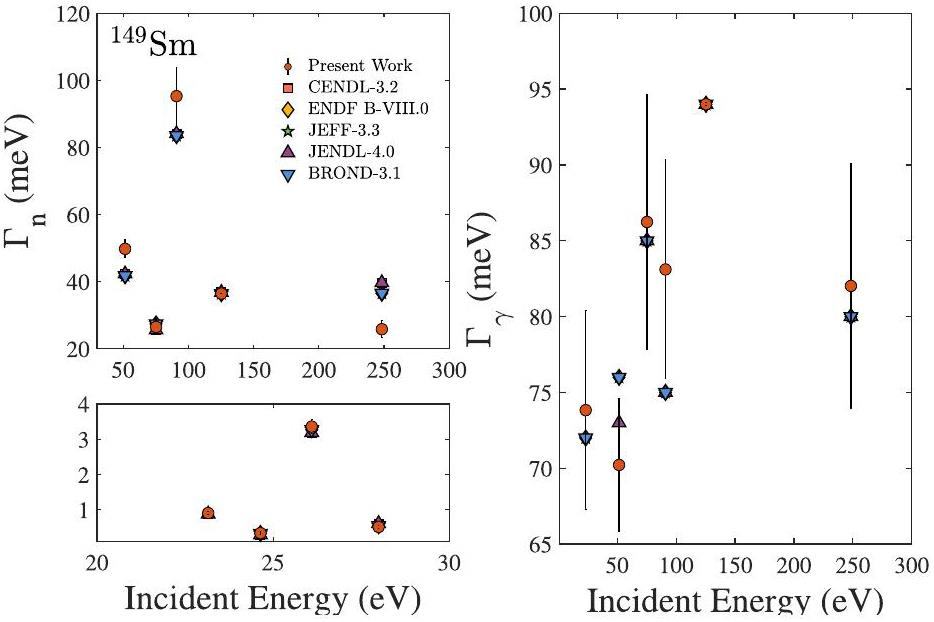

For the 149Sm isotope, the discrepancy in the parameter Γn across different evaluation databases was minimal, and the experimental findings aligned closely with the assessment databases at most energy levels. Specifically, our experiment yielded a value of 25.8±2.5 meV at an energy of 248.4 eV, whereas the four evaluation databases reported values ranging from 36.6 meV to 39.7 meV. The Γγ value in the CENDL-3.2 database aligns with that in the JENDL-4.0 database at the energy points 23.2, 24.6, 26.1, and 28.0 eV. However, it diverges from the evaluation databases of ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.3, and BROND-3.1. At the energy points of 51.5, 75.2, 90.9, 125.3, and 248.4 eV, the experimental results are consistent with those in the ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.0, JENDL-4.0, and BROND-3.1 databases.

Summary and Conclusions

The neutron capture cross-section of a natural samarium target was measured at the Back-n facility in the China Spallation Neutron Source. The environmental and neutron-scattering backgrounds were subtracted through experimental measurements, whereas the in-beam γ-ray background was removed by combining experiments and simulations. Subsequently, the neutron resonance parameters for various Sm isotopes from 20 to 300 eV were extracted using the SAMMY code based on the R-matrix theory. For the parameters Γn and Γγ in these energies of 147,149Sm, the percentages consistent with the results of the CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JEFF-3.3, JENDL-4.0, and BROND-3.1 database are 27%, 65%, 65%, 42%, and 58%, respectively. However, 27% of the results were inconsistent with those of the major libraries. This work enriches experimental data of the 147,149Sm neutron capture resonance and helps clarify the differences between different evaluation databases at the above energies.

The s process: Nuclear physics, stellar models, and observations

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83 157-193 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.83.157The r-process and nucleochronology

. Phys. Rep. 208, 267-394 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(91)90070-3The p-process of stellar nucleosynthesis: astrophysics and nuclear physics status

. Phys. Rep. 384 1-84 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(03)00242-4Nuclear astrophysics

. Phys. Atom. Nucl. 73 1460-1468 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1134/S106377881008020X233Pa (n,γ) cross section extraction using the surrogate reaction 232Th(3He, p)234Pa* involving spin-parity distribution

. Phys. Rev. C 109Neutronics analysis of a subcritical blanket system driven by a gas dynamic trap-based fusion neutron source for 99Mo production

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 49 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01206-2China’s first pulsed neutron source

. Nature materials. 15, 689-691 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat4655Feasibility of medical radioisotope production based on the proton beams at China Spallation Neutron Source

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01438-wMeasurement and analysis of the neutron-induced total cross-sections of 209Bi from 0.3 eV to 20 MeV on the Back-n at CSNS

. Chin. Phys. C. 47,Measurement of Br(n,γ) cross sections up to stellar s-process temperatures at the CSNS Back-n

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 180 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01337-6Introduction to the overall physics design of CSNS accelerators

. Chin. Phys. C. 33, 1(2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/33/S2/001An overview of design for CSNS/RCS and beam transport

. Sci. China. Ser. G. 54, 239-244 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-011-4564-xSimulation of a high energy neutron irradiation facility at beamline 11 of the China spallation neutron source

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 860, 24-28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.04.004Design and construction of CSNS drift tube linac

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 911, 131-137 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.10.034Large area 3He tube array detector with modular design for multi-physics instrument at CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01161-4The 6LiF-silicon detector array developed for real-time neutron monitoring at white neutron beam at CSNS

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 946,Detection of low-energy charged-particle using the ΔE-E telescope at the Back-n white neutron source

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 981,Measurement of the 159Tb(n,γ) cross section at the CSNS Back-n facility

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Measurement of the relative differential cross sections of the 1H (n,el) reaction in the neutron energy range from 6 MeV to 52 MeV

. Eur. Phys. J. A 57, 6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00313-7Conceptual design of a Cs2LiLaBr6 scintillator-based neutron total cross section spectrometer on the Back-n beam line at CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 3 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01152-5Back-n white neutron source at CSNS and its applications

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00846-6Detector development at the Back-n white neutron source

. Radiation-detection technology and methods. 7, 171-191 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-022-00379-5Experimental determination of the neutron resonance peak of 162Er at 67.8 eV

. Phys. Rev. C 106,The C6D6 detector system on the Back-n beam line of CSNS

. Radiation-detection technology and methods. 3, 52 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-019-0129-8Measurements of the 197Au(n,γ) cross section up to 100 keV at the CSNS Back-n facility

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 101 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00931-wNew experimental measurement of natEr(n, γ) cross sections between 1 and 100 eV

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Neutron energy spectrum measurement of the Back-n white neutron source at CSNS

. Eur. Phys. J. A 55, 115 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12808-1In-beam gamma rays of CSNS Back-n characterized by black resonance filter

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01553-8Monte-Carlo calculations of the energy resolution function with Geant4 for analyzing the neutron capture cross section of 232Th measured at CSNS Back-n

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1013,Measurement of the neutron total cross section of carbon at the Back-n white neutron beam of CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 139 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0660-9Double-bunch unfolding methods for back-n white neutron source at CSNS

. J. Instrum. 15, 03 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/15/03/P03026208Pb(n, γ) cross sections by activation between 10 and 200 keV

. Phys. Rev. 181, 1639 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.181.1639Measurement of 232Th(n,γ) cross section at the CSNS Back-n facility in the unresolved resonance region from 4 keV to 100 keV

. Chin. Phys. B 31,Geant4–a simulation toolkit

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250-303 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8Geant4 development for actinides photofission simulation

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1062,Measurements of the 107Ag neutron capture cross sections with pulse height weighting technique at the CSNS Back-n facility

. Chin. Phys. B 31,The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (I). Evaluation of the input data and adjustment procedures

. Chin. Phys. C. 45,Accuracy of the pulse height weighting technique for capture cross section measurements

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 39, 689-692 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2002.10875193Hong-Wei Wang and Chun-Wang Ma are the editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and were not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.