Introduction

Bentonite is often selected as an engineering barrier in a high-level radioactive waste (HLW) repositories due to its low hydraulic conductivity, which leads to a diffusion-controlled process for radionuclide transport [1-4]. The effective diffusion coefficient (De), a critical parameter in the safety assessment of repositories, describes the diffusion behavior of radionuclides in porous media [5-7]. Under complex disposal conditions, De is affected by the properties of radionuclides, such as diffusing species and adsorption properties [8]; the characteristics of bentonite, such as compaction, pore structure, and physical and chemical properties [3, 9, 10]; and the porewater chemistry, such as pH and ionic strength [11-14]. Over the few decades, considerable attention has been devoted to determining the De of radionuclides in compacted bentonite [1, 8, 15-17].

Predicting the De of radionuclides is both challenging and crucial due to the non-linear and complex interactions among radionuclides, porewater, and bentonite[2, 3]. Machine learning (ML) models are valuable tools for this task because they can manage complex and high-dimensional data. Various ML models, such as the light gradient boosting machine (LGBM), extreme gradient boosting (XGB), categorical boosting (CatB), support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and artificial neural networks (ANN), have been applied to predict the De of radionuclides in compacted bentonite [18-21]. Radionuclide diffusion datasets were compiled from experimental data published in the literatures and a radionuclide diffusion database established by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA-DDB). These datasets included numerous input features ranged from 3 to 16 and the data size ranged from 293 instances to 956 instances [19-21]. It is worth mentioning that the JAEA-DDB collected over 5000 instances from radionuclide diffusion experiments spanning 1982 to 2009 [22]. However, the instances increased with decreasing input features, primarily due to the missing data, resulting in a potential impact on the accuracy and reliability of the ML model explanations.

The issues caused by missing data are a pervasive concern in databases [23, 24]. Missing data can lead to suboptimal outcomes, reduce predictive performance, and even result in misleading conclusions [25, 26]. For instance, the dry density and rock capacity factor have been reported as the two most influential factors in predicting the De [20, 21]. In contrast, Wu et al. (2024) observed that the ion diffusion coefficient in water and dry density were the top-two contributors. This discrepancy can be attributed to an insufficient number of instances in the datasets used. Therefore, a comprehensive dataset is essential to provide a more reliable analysis of the diffusion mechanisms.

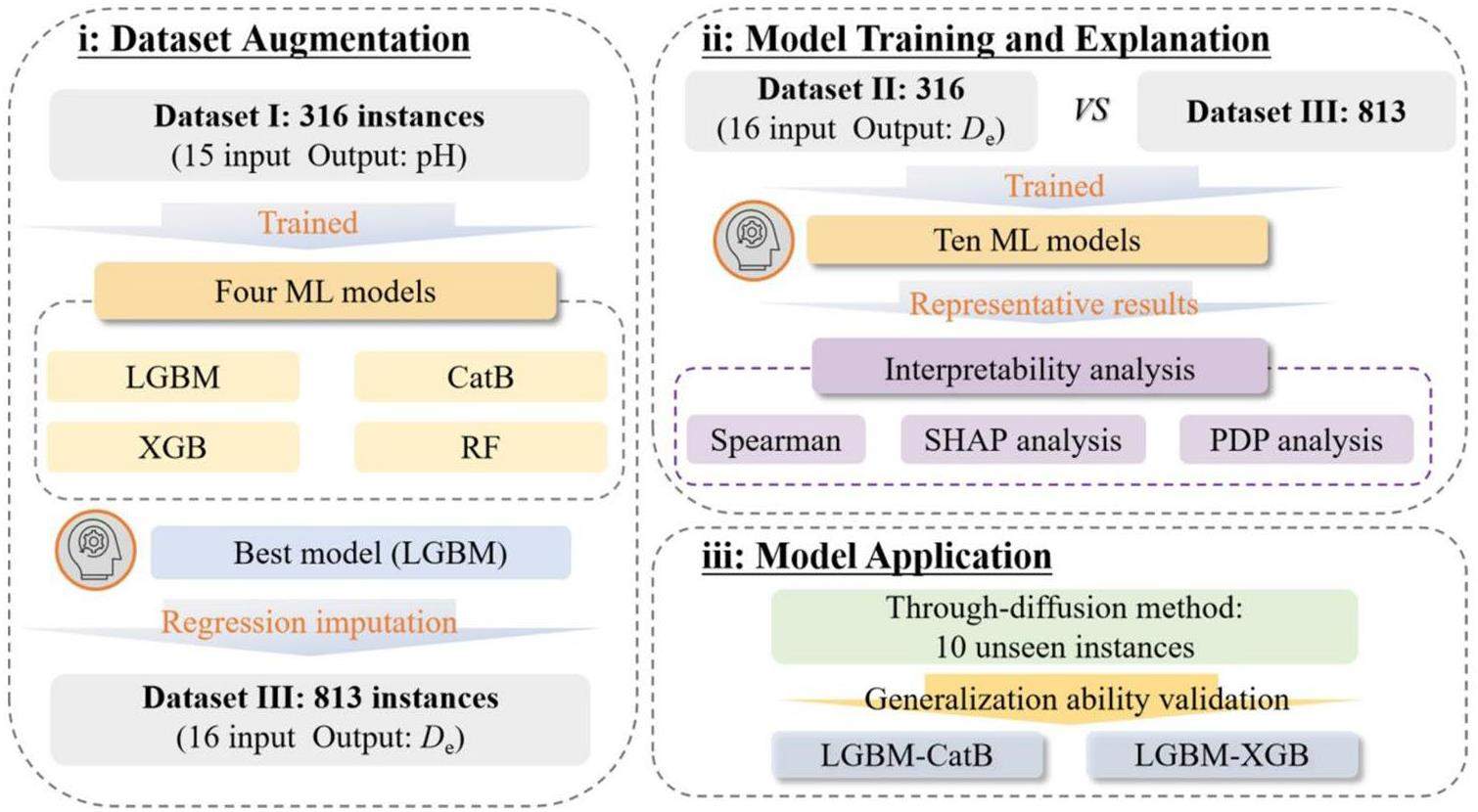

This study presents a novel, comprehensive radionuclide diffusion dataset with micro-mesoscopic features using ML models as regression imputation techniques. Firstly, the LGBM was employed as a regression-based missing data imputation method to impute over 60% of the missing data. Subsequently, ten ML models, including three ensemble ML algorithms (LGBM-CatB, LGBM-XGB, and LGBM-RF), four decision-tree algorithms (LGBM, CatB, XGB, and RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and two neural networks (ANN and deep neural network (DNN)), were trained, optimized, and tested by five-fold cross-validation to predict De values. Finally, through-diffusion experiments were conducted to measure the diffusion parameters of EuEDTA- and HCrO4- in compacted bentonite, including De, rock capacity factor, accessible porosity, total porosity, and distribution coefficient, to evaluate the generalization of the trained ML models. The goal was to develop predictive models that exhibit high accuracy, strong robustness, and clear interpretability for radionuclide diffusion studies, which are crucial for the safety assessment of HLW repositories.

Materials and Methods

Material

Ba-bentonite was prepared by modifying Gaomiaozi (GMZ) bentonite with a BaCl2 solution. The mass percentage of BaCl2 in modified bentonite was 5%. The detailed procedures for this modification has been previously described [16]. Wyoming bentonite powder had the grain dry density of 2760 kg/m3, montmorillonite content of 0.85, external surface area of 38 m2/g, and cation exchange capacity of 78.7 meq/100g [27, 28]. Ba-bentonite powder had the grain dry density of 2710 kg/m3, montmorillonite content of 0.78, external surface area of 27.3 m2/g, and cation exchange capacity of 58.7 meq/100 g [16].

All the solid chemicals were purchased from Aladdin. The pH values of the NaCl solution were adjusted to 5.0 ± 0.1 and 7.0 ± 0.1 for EuEDTA- and HCrO4- diffusion experiments, respectively. A stock solution of EuEDTA- was prepared by dissolving a measured amount of EuNO3. 6 H2O in 200 mL of a solution mixed with 0.6 mol/L NaCl and 0.01 mol/L EDTA. Similarly, a stock solution of HCrO4- was prepared by dissolving a measured amount of K2Cr2O7 in 200 mL of 0.5 mol/L NaCl solution. The initial concentrations of HCrO4- and EuEDTA- were 1.8 × 10-3 mol/L and 5.7 × 10-4 mol/L, respectively, with corresponding pH values of 5.3 ± 0.1 and 6.8 ± 0.1. The uncertainty in the pH was determined based on the standard deviation derived from the five source solutions for HCrO4- and EuEDTA-. Excess EDTA ensured the complete complexation of Eu(III).

Through-diffusion method

A through-diffusion method was used to measure the diffusion parameters of EuEDTA- and HCrO4- in compacted bentonites. The experiments were operated under ambient conditions, with pH 5.3 ± 0.1 and a temperature of 25 ± 3 3 °C for EuEDTA- diffusion, and pH 6.8 ± 0.1 and a temperature of 15 ± 3 °C for HCrO4- diffusion. The bentonite powder was compacted into cylindrical blocks with dry densities in the range of 1200-1800 kg/m3. The powder, with an initial water content of approximately 5%, was calculated to weigh between 7.8 g and 11.4 g for the preparation of the bentonite blocks. During the weighing process and preparation of bentonite blocks in the experimental procedure, approximately 0.3 g of bentonite powder was lost. This loss represents the primary source of uncertainty in the compacted dry density. Table 1 summarizes the experimental conditions used in diffusion experiments. After the compacted bentonite blocks were mounted in the diffusion setups, they were saturated for five weeks with NaCl solution in the diffusion cells. The diffusion experiments lasted 90 days for EuEDTA- and 25 days for HCrO4-.

| Experimental conditions | Detailed information | |

|---|---|---|

| Anion | EuEDTA- | HCrO4- |

| Bentonite type | Ba-bent. | Wyoming |

| Initial concentration (× 10-3 mol/L) | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 1.80 ± 0.10 |

| Ionic strength (mol/L) | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Dry density (kg/m3) | 1300-1700 | 1200-1800 |

| pH (-) | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.1 |

| Temperature (°C) | 25 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 |

| Block dimension (cm) | ||

| Volume of source reservoir (mL) | 200 | |

| Volume of target reservoir (mL) | 10 | |

Cr and Eu concentrations were measured using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (Optima 7000DV, PerkinElmer, USA). Data processing was performed using Fitting for diffusion parameters software to calculate diffusion parameters such as the De, rock capacity factor, distribution coefficient, total porosity, and accessible porosity. Further details regarding the experimental setup, operational steps, and data processing are available in previous studies [17, 29].

Data

Data compilation

The datasets were gathered from the JAEA-DDB and 16 published resources, covering the period from 1982 to 2024. The dataset comprised 16 input features and 324 experimental instances, including 304 instances obtained from Wu et al. (2024) and 20 experimental instances from three other studies [17, 20, 27]. Notably, the absence of pH values in 514 instances of the JAEA-DDB resulted in a significantly reduction in data size. To address this, regression imputation techniques using ML models were applied to predict the pH values based on a dataset of 324 instances, thereby expanding the dataset to 838 instances.

The dataset included 16 input features, which were categorized into three groups: (i) porewater properties, comprising the ionic strength (I), temperature (T), and pH; (ii) bentonite properties, including the montmorillonite content (m), external surface area (Aext), dry density (ρd), grain density (ρs), total porosity (εtot, and montmorillonite stacking number (nc); and (iii) radionuclide properties, encompassing the ion diffusion coefficient in water (Dw), molecular weight (MW), ion molar conductivity (λ), ionic radius (r), ionic charge (z), distribution coefficient (Kd), and rock capacity factor (α).

Data preprocessing

The presence of outliers can reduce the predictive accuracy of ML models. To address this issue, the Mahalanobis distance (MD) method was employed to identify and remove outliers. The cutoff point (di) is given as:

Three datasets were used to enhance the prediction of radionuclide diffusion. An overview of the features and instances of each dataset is summarized in Table 2. Dataset I included 15 input features, with pH as the output feature. To ensure the data quality and reduce noise, eight instances were removed using the MD method. This process yielded Dataset I, comprising 316 instances. The statistical details of Dataset I are presented in Table S1 of the supporting information. Datasets II and III comprised 16 input features, including the basic features (15 input features of Dataset I) and pH. The output feature for Datasets II and III was the De. Dataset III, comprising 813 instances, was obtained after removing 17 instances. It is noteworthy that these datasets comprised parameters at the micro-mesoscopic level. Specifically, the montmorillonite stacking number and ionic radius were classified as microscopic parameters, whereas the other parameters were considered as mesoscopic.

| Dataset | Input feature | Input number | Output feature | Instance number | Dataset Link |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset I | Basic features: | 15 | pH | 316 | https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.j00186.00710 |

| (i) Porewater: I, T. | |||||

| (ii) Bentonite: m, Aext, ρd, ρs, εtot, nc. | |||||

| (iii) Radionuclides: Dw, r, z, λ, MW, Kd, α. | |||||

| Dataset II | Basic features and pH | 16 | De | 316 | |

| Dataset III | Basic features and pH | 16 | De | 813 |

Imputation methods

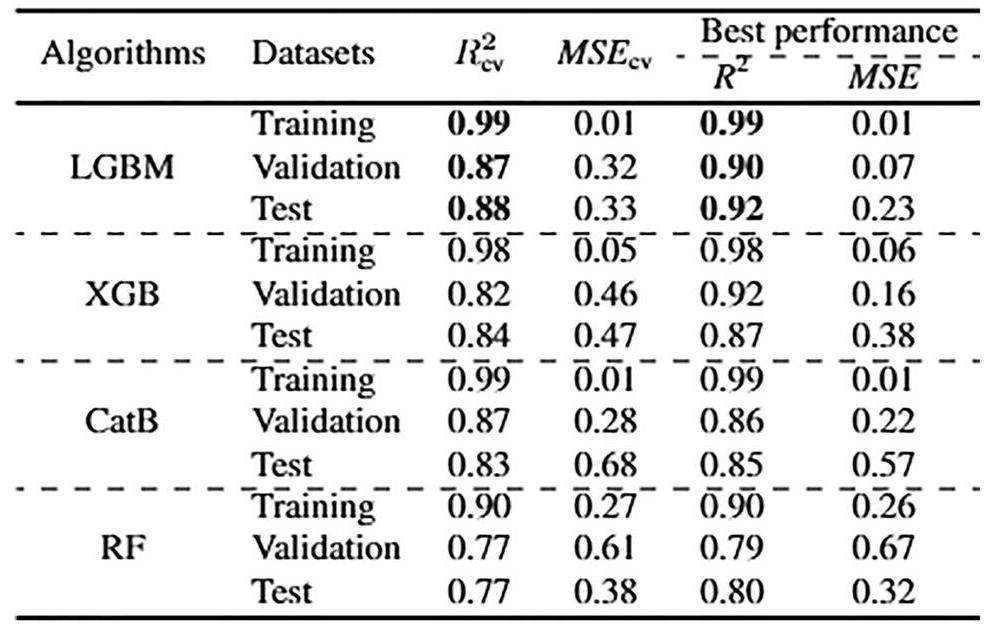

Four decision-tree models, namely LGBM, CatB, XGB, and RF, were used as regression imputation methods to predict the pH values of Dataset I. LGBM exhibited superior predictive accuracy compared with the other models. This was consistent with the results of our previous study [21]. Dataset III was established by incorporating additional 514 instances with Dataset II using the LGBM for data imputation. Table S2 of the supporting information summarizes the statistical results of the input and output features for Dataset III.

Methodology

The De values of radionuclides in compacted bentonite were predicted using ten ML models, including three ensemble ML algorithms (LGBM-CatB, LGBM-XGB, and LGBM-RF), four decision-tree algorithms (LGBM, CatB, XGB, and RF), SVM, and two neural networks (ANN and DNN). Ensemble ML models combine the strengths of multiple individual models to enhance overall predictive performance and stability, offering a promising solution to the challenges of bias and variance in individual models [30]. Since LGBM exhibited superior predictive performance compared with the other models, it was combined with CatB, XGB, and RF to predict the De using a voting regressor method from the scikit-learn package [20, 31]. The voting regressor simultaneously applies multiple regression models to the same dataset, thereby optimizing the final output by synthesizing the prediction results of each model. During the training process, the system can adjust the weight distribution according to the performance of each model. The final prediction result

Figure 1 illustrates a workflow diagram for developing ML models to predict the De values of radionuclides in various compacted bentonites. This study was organized into three parts: (i) Dataset augmentation: Missing pH values were predicted using decision-tree algorithms, thereby refining the radionuclide diffusion dataset. (ii) Model training and explanation: Ten ML models were employed to train prediction models with high predictive accuracy. The diffusion mechanism was analyzed using Spearman, Shapley additive explanations (SHAP), and partial dependence plots (PDP). (iii) Model application: The De values of EuEDTA- and HCrO4- in compacted bentonites were measured using a through-diffusion method, which was employed to evaluate the generalization capability of the best ML models.

Model development and evaluation

The datasets were randomly divided into a training set consisting of 80% of the instances and a test set containing the remaining 20%. Since data processing using logarithmic transformation and min-max normalization exhibited an insignificant impact on the predictive accuracy in predicting the De of radionuclides in bentonite [19], logarithmic transformation was applied to the features, such as the ionic radius, ion diffusion coefficient in water, and De, owing to their significantly larger magnitudes compared to other features. A five-fold cross-validation method was used to reduce the risk of overfitting. Therefore, the 80% training data was further subdivided into a pretraining (80% of the training data) and a validation (20% of the remaining training data) datasets to pretrain the ML models and optimize the hyperparameters. The PSO technique was used to optimize the hyperparameters.

The predictive performance was evaluated by the coefficient of determination (R2), and mean square error (MSE). These metrics are given as follows:

Results and Discussion

Model development

Regression imputation for predicting pH

Handling missing data is a crucial step affecting the quality and reliability of the data analysis. Various regression imputation techniques have been applied to impute missing data, such as ANNs, multivariate imputation by chained equations, k-nearest neighbors, time-series deep learning models, generative broad Bayesian imputation, principal component analysis imputation, and simple arithmetic averages. These methods have been applied to datasets with missing data percentages ranging from 0 to 80% [24, 26, 32-36]. Generally, three types of missing data mechanisms are recognized: missing completely at random, missing at random, and missing not at random [23]. Each mechanism presents different challenges and implications for imputation, highlighting the importance of identifying the underlying pattern of missingness before selecting an appropriate imputation strategy.

The JAEA-DDB database collected data from the literatures and reports covering 1982 to 2009. The instances have been derived from various diffusion experimental methods and numerous researchers. The absence of pH values in 514 instances within the JAEA-DDB database can be explained that these researches ignored the importance of pH values in their studies. In the JAEA-DDB database, missing data primarily resulted from ignoring or inadequately measuring the parameters that related to the radionuclide diffusion. The missing mechanism in the JAEA-DDB database was assumed to be missing completely at random, corresponding to a non-continuous missingness. Based on the selected 16 input features, more than 60% of the dataset (514 instances) lacked pH values. Decision-tree models were employed to predict the missing pH values to augment the dataset and enhance the robustness of the ML models. Specifically, LGBM, CatB, XGB, and RF were employed to predict the pH values of Dataset I.

The predicted performances are summarized in Table 3. The LGBM exhibited superior robustness compared with the other models. For instance, the

|

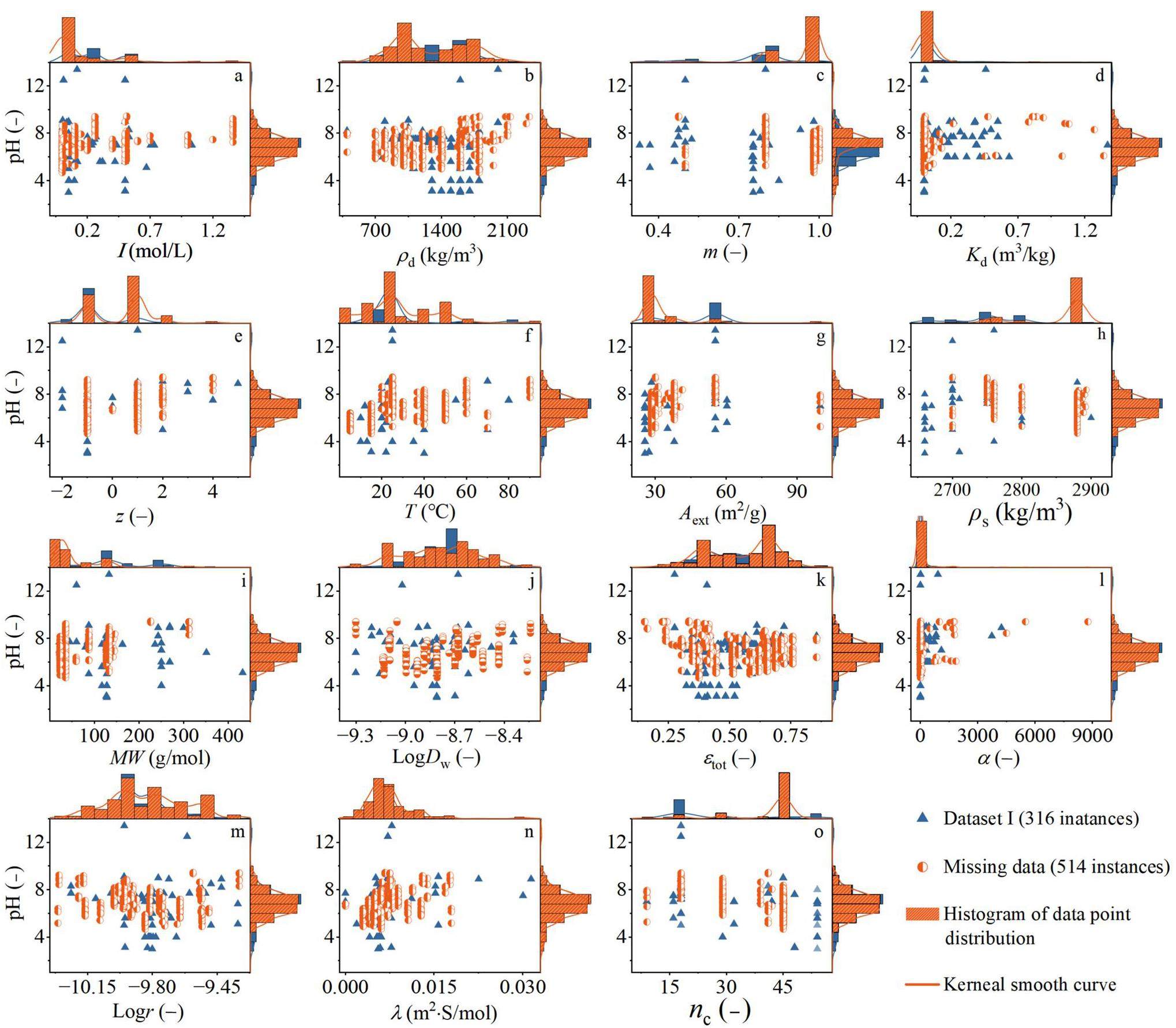

Figure 2 exhibits the data distribution and characteristics of the relationship between pH and each input feature. Blue and orange represent the data distributions of Dataset I and the imputed 514 instances, respectively. It clearly demonstrates a non-linear relationship between the pH and each input feature. The predicted pH values ranged from 5.0 to 9.0, exhibiting a Gaussian type distribution.

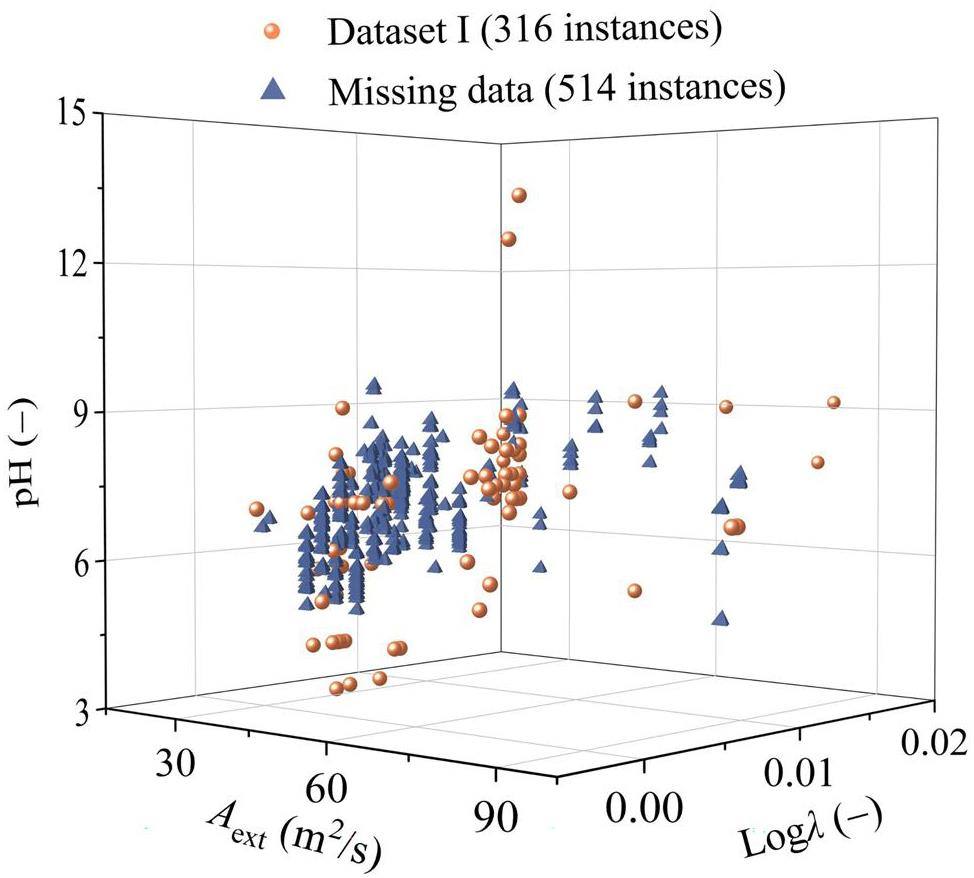

pH is an important porewater parameter that influences both the radionuclide species and surface charge of clay [37]. Figure 3 shows the pH dependence on the external surface area and ion molar conductivity, which are associated with the bentonite and radionuclide properties, respectively. Dataset I exhibits that the pH values ranged from 3.0 to 13.4. The predicted pH values are concentrated in the range from 5.0 to 9.0, suggesting a close adherence to a normal distribution of porewater for Dataset III.

Model development for radionuclide diffusion

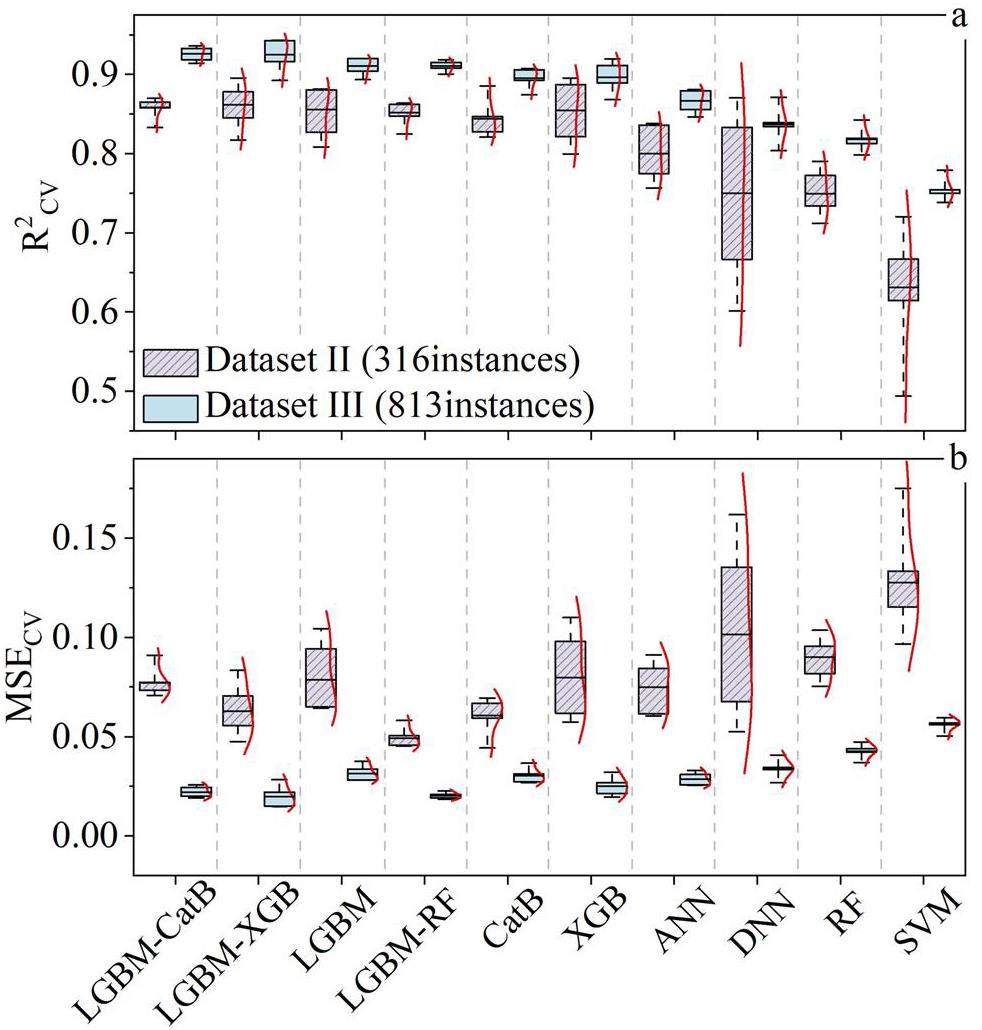

Ten ML models, namely LGBM-CatB, LGBM-XGB, LGBM-RF, LGBM, CatB, XGB, RF, ANN, DNN, and SVM, were used to predict the De values of radionuclides in compacted bentonite. Figure 4 shows the performance metrics of the ML models for the test datasets of Dataset II and III using the optimal hyperparameters tuned with PSO techniques (Table S4 in the supporting information). The performance metrics were assessed using five-fold cross-validation. The red lines represent the smooth kernel curve of the distribution of performance metrics. The black lines within and outside the box plots denote the mean values and standard deviations of the performance metrics, respectively, with a lower standard deviation indicating strong robustness of the ML models. The detailed performance metrics for the training, validation, and test datasets are listed in Table S5 of the supporting information.

As the number of instances increased from 316 (Dataset II) to 813 (Dataset III), the performance metrics of all ML models improved significantly, as evidenced by the higher

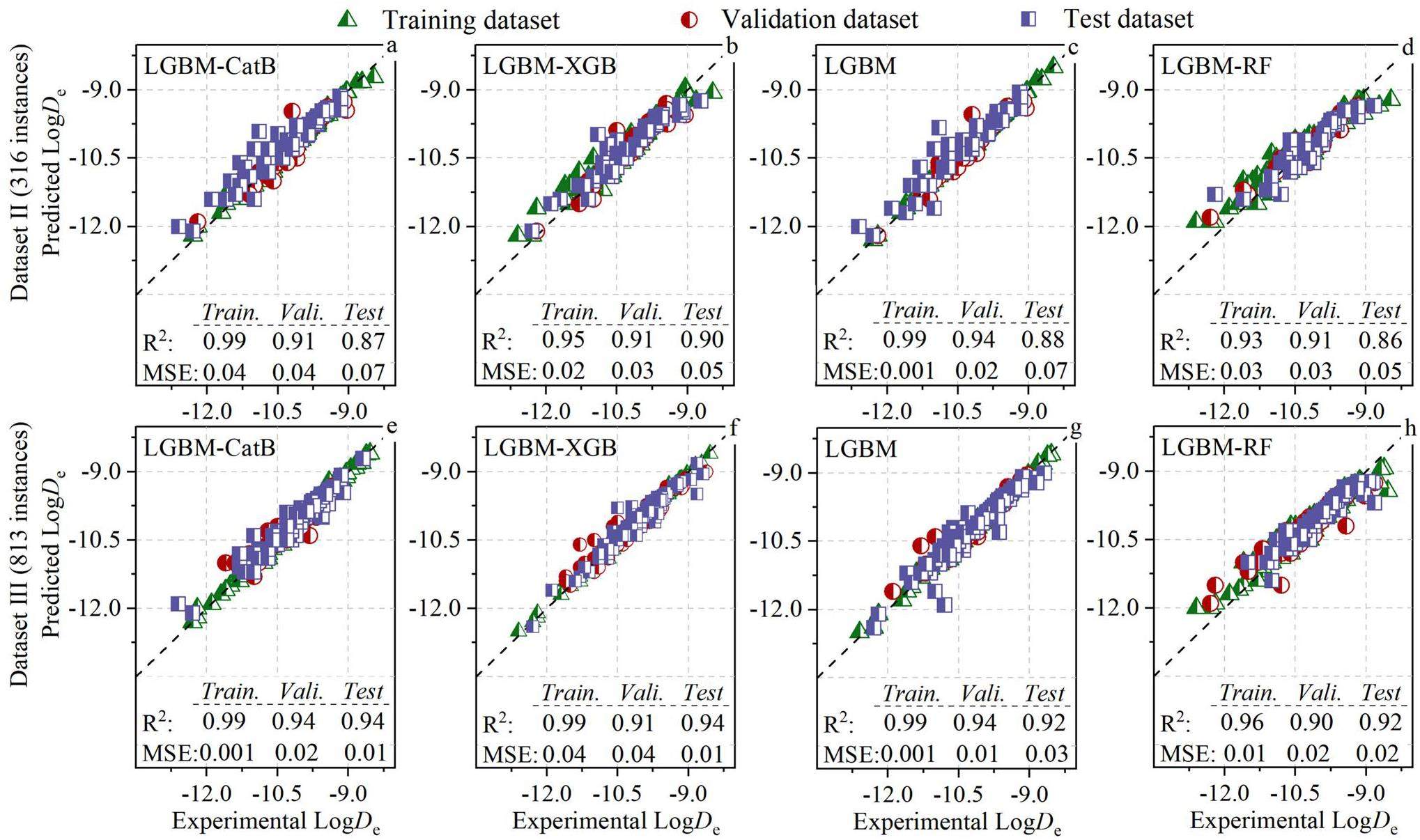

Figure 5 shows the regression plots comparing the experimental and predicted De values for the training (green triangle), validation (red circle), and test (purple square) datasets of Datasets II and III, using the LGBM-CatB, LGBM-XGB, LGBM, and LGBM-RF algorithms. These algorithms were selected owing to their excellent predictive accuracies. The plots reveal a close alignment between the experimental and predicted De values with the slope line, underscoring the effective simulation capability of these ML models for predicting radionuclide diffusion processes. The performance metrics of the best-performing models are shown in Fig. 5. Notably, the ML models applied to the test dataset of Dataset III outperformed those applied to Dataset II. This disparity can be attributed to the augmentation of instances in Dataset III, which facilitates the models’ ability to capture complex relationships within the data more effectively. For Dataset III, the ranking of models was as follows: LGBM-CatB (R2 = 0.94) ≈ LGBM-XGB (R2 = 0.94) > LGBM (R2 = 0.92) ≈ LGBM-RF (R2 = 0.92). These results indicate that both LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB exhibit high predictive accuracy.

Sensitivity analysis

Spearman and Shapley additive explanation analyses

ML models can uncover predictive principles through analysis techniques that rank the importance of influencing factors in predictions, such as feature importance and SHAP analysis [19, 21, 43, 44]. Additionally, Spearman analysis, a non-parametric statistical method, assesses the monotonic relationship between two variables by correlating ranked data. These approaches provided valuable insights into the consistency and strength of the relationships within a dataset. It worthy notes that the reliability of these analytical techniques is intrinsically linked to the quality of the data used. Increasing the dataset size enhances the depth, broadness, and reliability of the ML models.

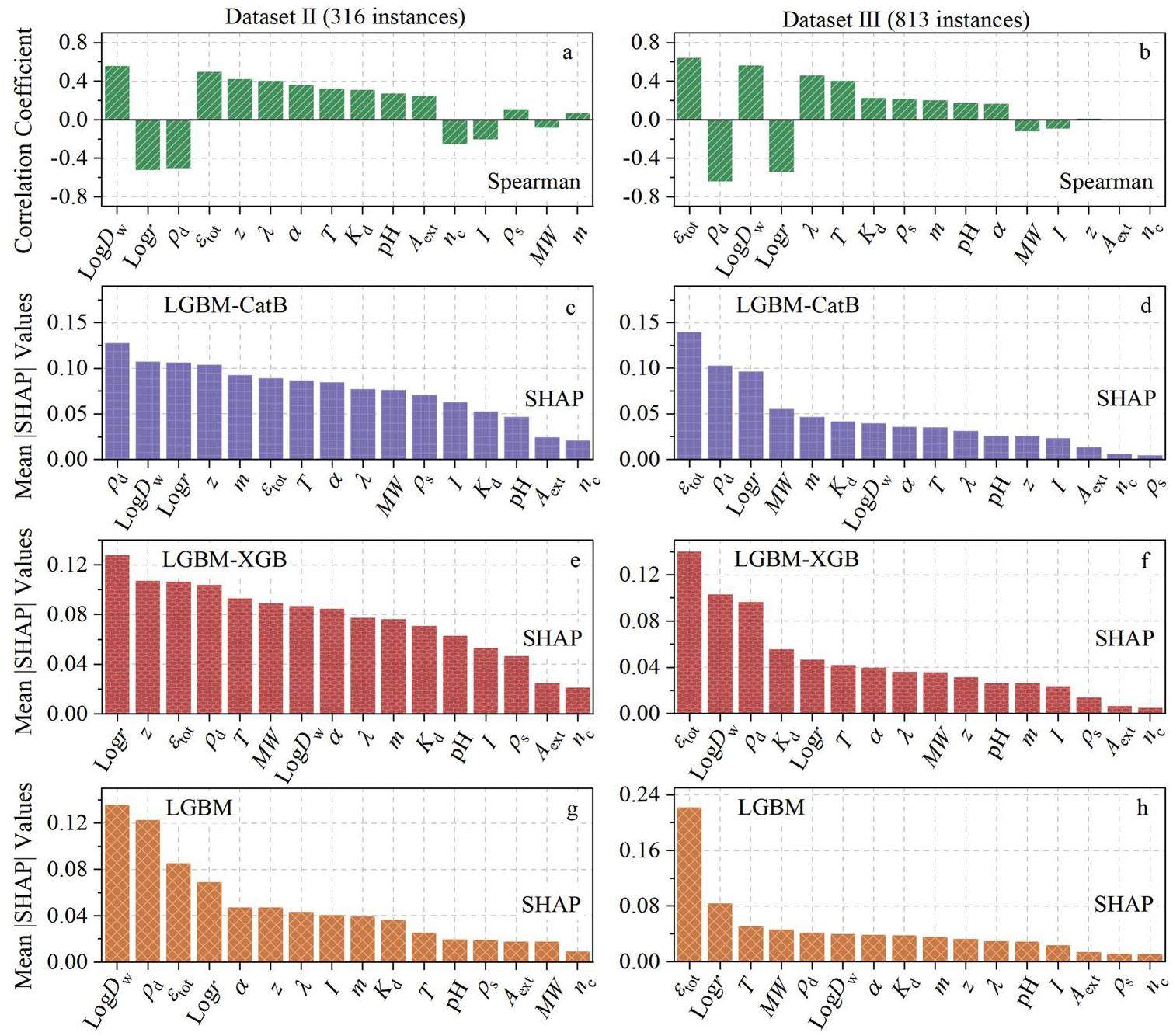

Spearman correlation and SHAP analysis techniques were employed to analyze the correlation and importance of the input features, presenting intuitively global interpretations of the ML models (Fig. 6). The features were ranked from left to right according to their correlation and contribution to the prediction. The Spearman correlation analysis revealed that the most influential factor among the 16 input features was the ion diffusion coefficient in water for Dataset II, and the total porosity for Dataset III. This feature exhibited a positive correlation with De (Figs. 6a and b). This is consistent with the previous findings [19] and Archie’s law [31, 45].

In the case of Dataset II, the SHAP analysis revealed that the most important input features varied across different ML models: the compacted dry density for LGBM-CatB, ionic radius for LGBM-XGB, and ion diffusion coefficient in water for LGBM (Figs. 6c, e, and g). Notably, only the SHAP results for LGBM were consistent with the Spearman correlation analysis. This discrepancy can be attributed to differences in the feature importance assessment and prediction mechanisms inherent to each ML algorithm. As the number of instances increased from 316 (Dataset II) to 813 (Dataset III), both Spearman and SHAP analyses identified the total porosity as the primary contributor, which is consistent with Archie’s law [31, 45]. The total porosity for radionuclide diffusion in compacted bentonite blocks is expressed as a percentage of the total interconnected pore space within the blocks. A higher total porosity implies greater availability of transport pathways. These findings suggest that larger datasets may reduce the discrepancies between ML models in terms of feature importance assessment and prediction mechanisms.

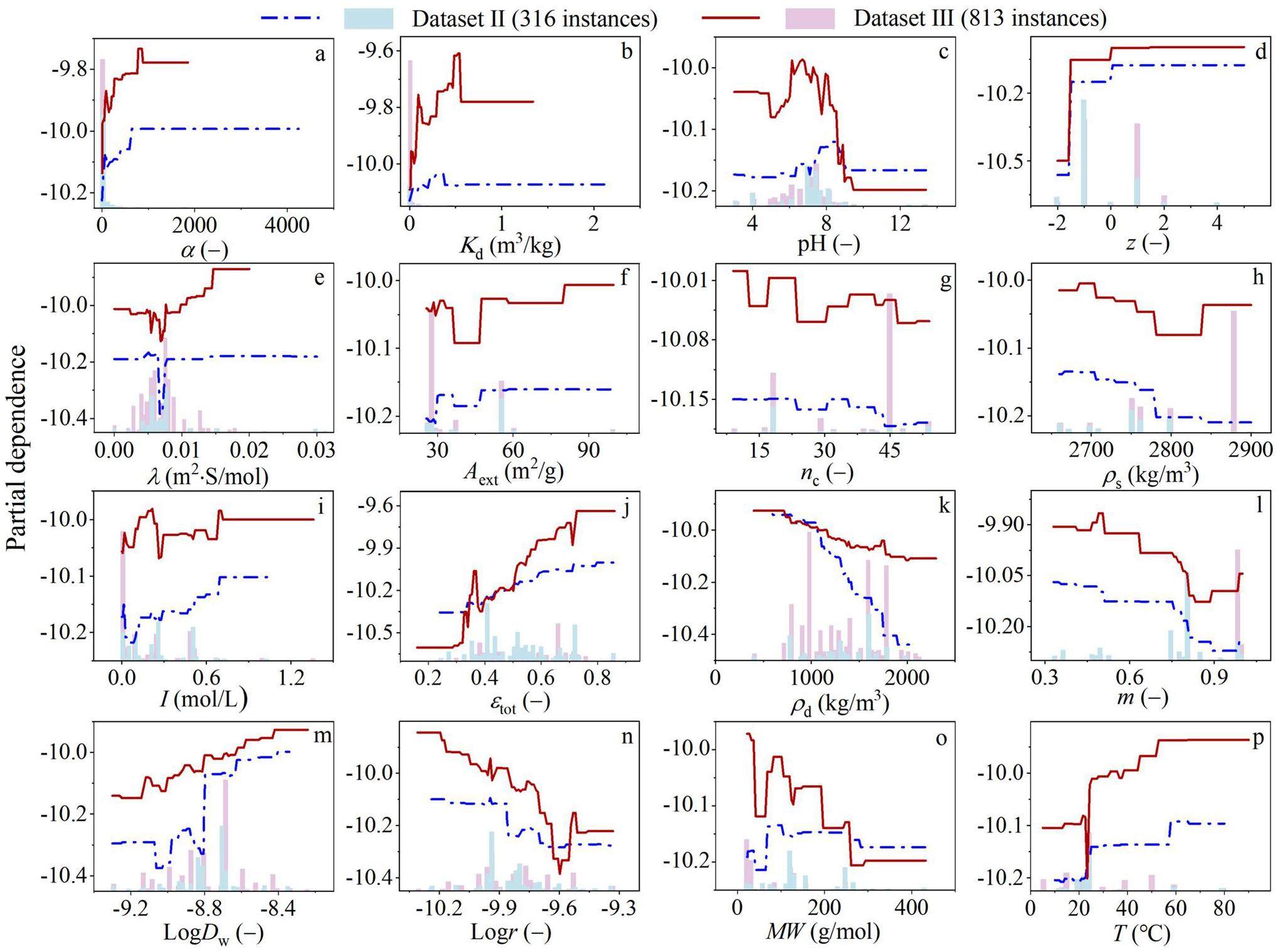

Partial dependence plots

The dependence of De on the 16 input features has been discussed in our previous study [19]. However, some relationships may remain unclear due to the limited size of the dataset. To address this, PDP analysis was performed to visually represent the univariate correlations and examine the influence of the size of the dataset on these relationships (Fig. 7). The histograms and lines correspond to the data distribution and correlation with each input feature and the PDP. Generally, a more concentrated data distribution generally leads to more accurate analytical results. These findings indicate that Dataset III, which was larger than Dataset II, exhibited more continuous PDP curves, suggesting a more stable and clear relationship between the features and De.

Figures 7a and b shows that both the rock capacity factor and distribution coefficient exhibit a clear positive correlation with the prediction for Dataset III. This finding is consistent with studies on radionuclides diffusion in crystalline rocks [46] and sodium montmorillonite [47]. Consistently, Fig. 7d illustrates the positive impact of ionic charge, where cations exhibit a higher De than neutral species, and anions display lower De values. This is consistent with previous studies, which attributed the differences in diffusion mechanisms to electrostatic interactions between the radionuclide species and charged bentonite surfaces [3]. Specifically, cation diffusion is controlled by surface diffusion effects, whereas anions diffusion is driven by anionic exclusion effects [47, 48].

pH values in the range from 6 to 9 negatively influence the prediction for Dataset III, whereas a peak was observed at approximately pH 8 for Dataset II (Fig. 7c). The negative effect of Dataset III might be more convincing because of its larger data size. Figure 7e shows a positive impact on the prediction when ion molar conductivity exceeded 0.01 m2⋅ S/mol for Dataset III. However, the relationships among the external surface area, montmorillonite stacking number, grain density, and ionic strength remained unclear for both Datasets II and III (Figs. 7f-i). This lack of clarity can be attributed to data dispersion, despite the larger dataset size.

In the case of remaining input features, such as the total porosity, ion diffusion coefficient in water, and temperature, exhibited positive impacts on the prediction, whereas the dry density, montmorillonite content, ionic radius, and molecular weight showed negative impacts (Figs. 7j-p). The positive influences of the total porosity and ion diffusion coefficient in water could be explained by Archie’s law [16, 45], whereas the positive impact of temperature followed the Arrhenius equations [49-51]. The detailed explanations are provided in our previous studies [19, 21]. It is worth mentioning that a negative influence of ionic radius was observed at Logr < -9.6 (2.5 Å). This positive relationship can be attributed to the limited data for species with ionic radius above 2.5 Å. Overall, the univariate correlation results visualized using the PDP technique align with the diffusion laws observed in the experiments and diffusion mechanisms derived from the numerical models. This consistency underscores the reliability of the interpretation capabilities of the ML models.

Diffusion experiments and model application

Anionic radionuclides with long half-life are important for the safety evaluation of HLW repositories because of their high diffusivities. A through-diffusion method was employed to measure the diffusion parameters of EuEDTA- and HCrO4- in compacted bentonites at compacted dry densities ranged from 1200 kg/m3 to 1800 kg/m3. Their De values were predicted using LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB to test the generalization ability.

Determination of the diffusion parameters using diffusion experiments

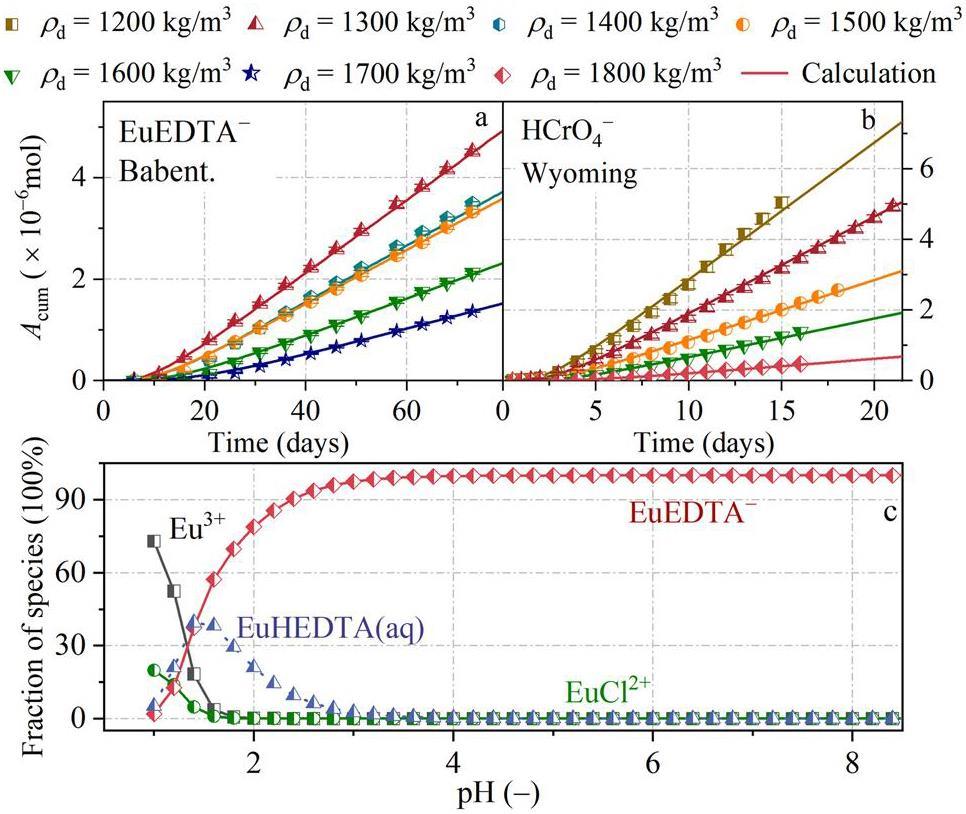

Figure 8 shows the breakthrough curves of EuEDTA- and the species distribution of Eu-EDTA complexes. Acum denotes the accumulated mass of EuEDTA- and HCrO4- that penetrated a 1.2 cm thick bentonite block to reach the sample reservoirs. The data show that the accumulated mass increased with decreasing dry density, which is consistent with the general understanding that lower dry density facilitates radionuclide diffusion through porous media [3, 5]. The pH was maintained at 5.3 ± 0.1 during the Eu(III) diffusion experiments. Simulations using Vision MINTEQ indicated that Eu(III) exists as a mixture of species, including Eu3+, EuHEDTA(aq), EuEDTA-, and EuCl2+, in 0.6 mol/L NaCl solution (Fig. 8c). EuEDTA- was the main species at pH above 2.0. It indicates that this study measured the diffusion parameters of EuEDTA- in compacted Ba-bentonite.

Table 4 summarizes the diffusion parameters of HCrO4- and EuEDTA-, including De, rock capacity factor, accessible porosity, total porosity, and distribution coefficient. Both De and distribution coefficient are important parameters in the safety assessment of repositories, whereas the other parameters play a crucial role in elucidating the diffusion mechanism. The error in the compacted dry density measurement was primarily attributed to a loss of approximately 0.3 g during the preparation of bentonite blocks. Both HCrO4- and EuEDTA- are monovalent anions that can’t access the interlayer pores of compacted bentonite [17, 21]. The rock capacity factor of HCrO4- was lower than the total porosity, indicating that the accessible porosity was equal to the rock capacity factor. This suggests that the predominant diffusion path of HCrO4- was through the free pores of compacted bentonite. In contrast, EuEDTA- exhibited an adsorptive behavior similar to that of simulated trivalent actinide complexes, such as AmEDTA- and CmEDTA-, with the rock capacity factor being higher than the total porosity. The distribution coefficient, Kd, of EuEDTA- was calculated as follows:

| ρd (kg/m3) | mbent (g) | De (× 10-11 m2/s) | Da (× 10-11 m2/s) | α (-) | εacc | εtot (-) | Kd (× 10-4 m3/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EuEDTA- in Ba-bentonite | |||||||

| 1300 ± 45 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.33 ± 0.01# | 0.52 | 6.7 ± 0.6 |

| 1400 ± 45 | 9.3 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.31 ± 0.01# | 0.48 | 5.6 ± 0.6 |

| 1500 ± 46 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.30 ± 0.01# | 0.45 | 4.7 ± 0.5 |

| 1600 ± 46 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.26 ± 0.01# | 0.41 | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| 1700 ± 47 | 11.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.19 ± 0.01# | 0.37 | 4.2 ± 0.3 |

| HCrO4-in Wyoming bentonite | |||||||

| 1200 ± 46 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.57 | - |

| 1300 ± 52 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 0.3 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.53 | - |

| 1500 ± 45 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.46 | - |

| 1600 ± 47 | 10.2 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.42 | - |

| 1800 ± 47 | 11.4 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.1 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.35 | - |

All diffusion parameters decreased with increasing dry density for both EuEDTA- and HCrO4-. The distribution coefficient of EuEDTA- ranged from 4.2 × 10-4 m3/kg to 6.7 × 10-4 m3/kg, which is lower than the range reported for EuEDTA- in hard rock clay (1.3 × 10-3-3.2 × 103- m3/kg) [52] and for CeEDTA- in compacted Zhisin bentonite (0.8 × 10-3-1.2 × 10-3 m3/kg) [17]. The distribution coefficient of EuEDTA- was lower than that of Eu3+, indicating that EDTA facilitated the diffusion of Eu(III), thereby reducing the retardation capacity of the bentonite barrier [52, 53]. This observation is consistent with the diffusion behavior of CeEDTA- and CoEDTA2- [17, 19, 31].

Model application

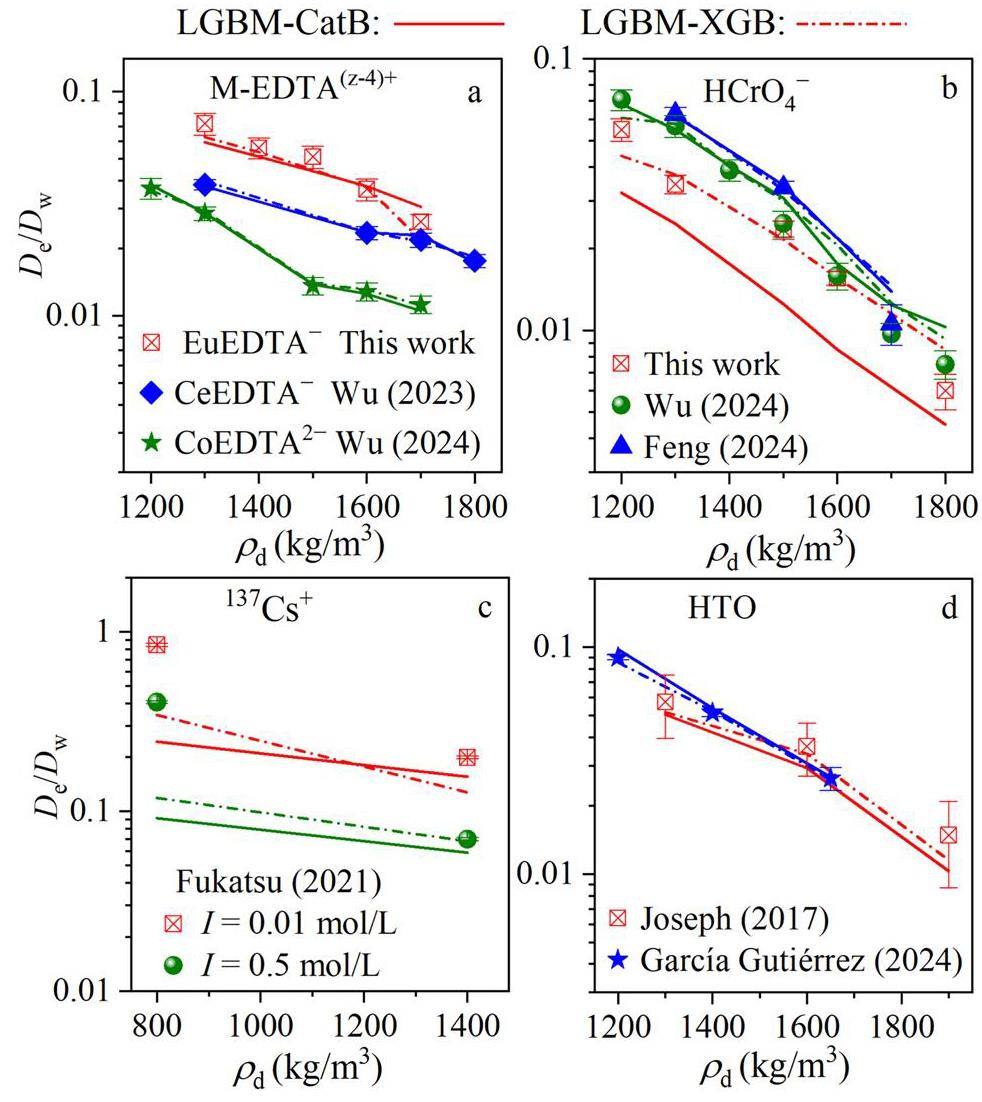

The LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB models were employed to predict the De of HCrO4- in compacted Wyoming bentonite and EuEDTA- in compacted Ba-bentonite, which were compared with published diffusion experimental results for HCrO4- and the simulated actinides CeEDTA- and CoEDTA2- [17, 19, 21]. Additionally, both models were used to predict the De of radionuclide cation 137Cs+ and neutral species HTO [8, 54, 55] (Fig. 9). It shows that De/Dw decreased with increasing compacted dry density, which is consistent with the result of previous studies [3, 5, 45]. In this study, the Dw value for metal-EDTA complexes was assumed to be 5.0 × 10-10 m2/s [56]. The De of EuEDTA- was observed to be higher than those of CeEDTA- [17]. and CoEDTA2- [19]. The LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB models successfully predict De, as evidenced by the good agreement with the experimental De values (Fig. 9a).

Figure 9b shows that the De of HCrO4- in compacted Wyoming bentonite is lower than that in Anji bentonite [19] and GMZ bentonite [21], likely due to the higher montmorillonite content. LGBM-CatB slightly underestimated De for HCrO4- in Wyoming bentonite, with the predicted De values being 25%-47% lower than the experimental De. Although this discrepancy is less pronounced than the predictions for HCrO4- in GMZ and Anji bentonites using LGBM and PSO-LGBM, the difference was reported to be 9%-27% [19, 21]. This performance is significantly superior to that predicted using Archie’s law, according to which the predictive De values were 1.0 to 1.5 orders of magnitude higher than the experimental results [45].

Figure 9c shows that the predicted De values of 137Cs+ are consistent with the experimental results at a compacted density of 1400 kg/m3. However, a significant underestimation was observed at a compacted density of 800 kg/m3, with a difference of approximately four times. This can be explained by the limited number of experimental data points available for this density in the dataset, which comprised only 58 instances, accounting for approximately 7% of the total dataset. It indicates that additional diffusion experiments for 137Cs+ should be conducted at a compact density of approximately 800 kg/m3 to facilitate the identification of diffusion patterns using ML models. Figure 9d illustrates that both the LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB models accurately predict the De of HTO. Under similar experimental conditions, the De in Wyoming bentonite (red squares) was higher than that in FEBEX bentonite (blue pentagrams), primarily because of the lower montmorillonite content, with m = 0.85 for Wyoming bentonite and m = 0.92 for FEBEX bentonite [54, 55].

Notably, the experimental diffusion data from this study, as well as from the 137Cs+ [8] and HTO [54, 55] diffusions, were not included in the test datasets, highlighting the strong generalization ability of both LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB models. The generalization ability of LGBM-XGB was superior to that of LGBM-CatB, indicating that model selection plays a crucial role in accurately predicting radionuclide diffusion in complex geological environments. Given that HLW repositories have been designed to operate for over 10,000 years, the prediction of radionuclide diffusion in bentonite barriers must consider the complex coupling effects among radionuclides, porewater, and bentonite under intrinsic disposal conditions. Current diffusion datasets remain insufficient for safety assessments of bentonite barriers owing to limitations in data size and dimensionality. Therefore, additional diffusion experiments should be conducted to enhance the dimensionality and scale of the datasets.

Conclusion

A radionuclide diffusion dataset comprising 16 input features and 813 instances, was developed using regression imputation machine learning (ML) methods. Ten ML algorithms were employed to predict the effective diffusion coefficient (De) of radionuclides in compacted bentonite. The light gradient boosting machine (LGBM)-extreme gradient boosting (XGB) and LGBM-categorical boosting (CatB) algorithms surpassed the other ML models, achieving R2 values of 0.94 based on the imputed dataset. This improvement indicates that the imputed dataset enabled the ML models to achieve high predictive performance and strong robustness.

The generalizability of the LGBM-CatB and LGBM-XGB models was evaluated by applying them to predict the De values of EuEDTA- in compacted Ba-bentonite and HCrO4- in compacted Wyoming bentonite. Both models exhibited excellent predictive accuracy for EuEDTA-, whereas LGBM-CatB slightly underestimated De for HCrO4- in Wyoming bentonite, with predicted De values 25%-47% lower than the experimental De. This indicates that the generalization ability of LGBM-XGB surpassed that of LGBM-CatB.

It has been widely accepted that the quality and quantity of datasets play a crucial role in the predictive performance of ML models. However, a significant number of experimental diffusion results were excluded from the diffusion datasets due to incomplete or missing data. To address this limitation, additional experiments are necessary to comprehensively characterize the properties of porewater and bentonite. These experiments should include but are not limited to mineral composition, elemental, and particle size analyses.

Cesium transport in Czech compacted bentonite: Planar source and through diffusion methods evaluated considering non-linearity of sorption isotherm

. Appl. Clay Sci. 245,A model for describing advective and diffusive gas transport through initially saturated bentonite with consideration of temperature

. Eng. Geol. 323,Relevance of diffuse-layer, Stern-layer and interlayers for diffusion in clays: A new model and its application to Na, Sr, and Cs data in bentonite

. Appl. Clay Sci. 244,Adsorption characteristics of strontium by bentonite colloids acting on claystone of candidate high-level radioactive waste geological disposal sites

. Environ. Res. 213,Diffusion coefficients and accessible porosity for HTO and 36Cl in compacted FEBEX bentonite

. Appl. Clay Sci. 26, 65-73 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2003.09.012Machine learning-driven prediction of phosphorus adsorption capacity of biochar: Insights for adsorbent design and process optimization

. J. Environ. Manage. 369,Pore-scale modeling of water and ion diffusion in partially saturated clays

. Water Resour. Res. 60,Diffusion of tritiated water, 137Cs+, and 125I- in compacted Ca-montmorillonite: Experimental and modeling approaches

. Appl. Clay Sci. 211,Role of interlayer porosity and particle organization in the diffusion of water in swelling clays

. Appl. Clay Sci. 207,Importance of interlayer equivalent pores for anion diffusion in clay-rich sedimentary rocks

. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 1998-2006 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b03781Ion concentration caused by an external solution into the porewater of compacted bentonite

. Phys. Chem. Earth. 29, 119-127 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pce.2003.11.004Porewater chemistry in compacted bentonite: Application to the engineered buffer barrier at the Olkiluoto site

. Appl. Geochem. 74, 165-175 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2016.09.010Porewater chemistry of Opalinus clay revisited: Findings from 25 years of data collection at the Mont Terri Rock Laboratory

. Appl. Geochem. 138,Effect of the pore water composition on the diffusive anion transport in argillaceous, low permeability sedimentary rocks

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 213, 40-48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2018.05.001Modeling diffusion and adsorption in compacted bentonite: a critical review

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 61, 293-302 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7722(02)00128-6Restriction of Re(VII) and Se(IV) diffusion by barite precipitation in compacted bentonite

. Appl. Clay Sci. 232,Experimental and modeling study of the diffusion path of Ce(III)-EDTA in compacted bentonite

. Chem. Geol. 636,Application of machine learning to study the effective diffusion coefficient of Re(VII) in compacted bentonite

. Appl. Clay Sci. 243,Predicting anion diffusion in bentonite using hybrid machine learning model and correlation of physical quantities

. Sci. Total Environ. 946,Application of machine learning in predicting the apparent diffusion coefficient of Se(IV) in compacted bentonite

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 333, 5811-5821 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-024-09637-wUnveiling the Re, Cr, and I diffusion in saturated compacted bentonite using machine-learning methods

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 93 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01456-8Missing data imputation using utility-based regression and sampling approaches

. Comput. Meth. Prog. Bio. 226,A comparative analysis of missing data imputation techniques on sedimentation data

. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15,Is replacing missing values of PM2. 5 constituents with estimates using machine learning better for source apportionment than exclusion or median replacement?

Environ. Pollut. 354,Enhancing environmental data imputation: A physically-constrained machine learning framework

. Sci. Total Environ. 926,Analyzing porosity of compacted bentonite via through diffusion method

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 333, 1185-1193 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-024-09368-yAnion diffusion in compacted clays by pore-scale simulation and experiments

. Water Resour. Res. 56,New Strategies for constructing and analyzing semiconductor photosynthetic biohybrid systems based on ensemble machine learning models: Visualizing complex mechanisms and yield prediction

. Bioresour. Technol. 412,Predicting the diffusion of CeEDTA- and CoEDTA2- in bentonite using decision tree hybridized with particle swarm optimization algorithms

. Appl. Clay Sci. 262,Generative broad Bayesian (GBB) imputer for missing data imputation with uncertainty quantification

. Knowl. Based Syst. 301,Imputation of missing values in well log data using k-nearest neighbor collaborative filtering

. Comput. Geosci. 193,Machine learning aids imputation of missing petrophysical data in Iraqi reservoir

. J. Pet. Technol. 76, 58-61 (2024). https://doi.org/10.2118/0824-0058-JPTAdvanced machine learning for missing petrophysical property imputation applied to improve the characterization of carbonate reservoirs

. Geoemgry Sci. Eng. 238,Deep sequence model-based approach to well log data imputation and petrophysical analysis: A case study on the West Natuna Basin, Indonesia

. J. Appl. Geophy. 218,Co-transport of U(VI) and gibbsite colloid in saturated granite particle column: role of pH, U (VI) concentration and humic acid

. Sci. Total Environ. 688, 450-461 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.395Machine learning the nuclear mass

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 109 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00956-1Machine learning approach for investigating chloride diffusion coefficient of concrete containing supplementary cementitious materials

. Constr. Build. Mater. 328,Classification of superconducting radio-frequency cavity faults of CAFE2 using machine learning

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 104 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01685-5Unveiling the migration of Cr and Cd to biochar from pyrolysis of manure and sludge using machine learning

. Sci. Total Environ. 885,Identifying descriptors for promoted rhodium-based catalysts for higher alcohol synthesis via machine learning

. ACS catalysis. 12, 15373-15385 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.2c04349Prediction of the first 2+ states properties for atomic nuclei using light gradient boosting machine

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 21 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01613-zApplication of machine learning in ultrasonic pretreatment of sewage sludge: Prediction and optimization

. Environ. Res. 263,A modified version of Archie’s law to estimate effective diffusion coefficients of radionuclides in argillaceous rocks and its application in safety analysis studies

. Appl. Geochem. 59, 85-94 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2015.04.002Through diffusion experiments to study the diffusion and sorption of HTO, 36Cl, 133Ba and 134Cs in crystalline rock

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 222, 101-111 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconhyd.2019.03.002Diffusion and sorption of Cs+, Na+, I- and HTO in compacted sodium montmorillonite as a function of porewater salinity: Integrated sorption and diffusion model

. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 132, 75-93 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.02.004A coherent approach for cation surface diffusion in clay minerals and cation sorption models: Diffusion of Cs+ and Eu3+ in compacted illite as case examples

. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 274, 79-96 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2020.01.054Reactive transport modeling of diffusive mobility and retention of TcO4-in Opalinus clay

. Appl. Clay Sci. 251,Activation energy for diffusion of chloride ions in compacted sodium montmorillonite

. J. Contam. Hydrol. 35, 67-75 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7722(98)00116-8Activation energies of the self-diffusion of HTO, 22Na+ and 36Cl- in a highly compacted argillaceous rock (Opalinus clay)

. Appl. Geochem. 20, 961-972 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2004.10.007Adsorption and retarded diffusion of EuIII-EDTA- through hard clay rock

. J. Hydrol. 544, 125-132 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2016.11.014Perturbation induced by EDTA on HDO, Br- and EuIII diffusion in a large-scale clay rock sample

. Appl. Clay Sci. 105, 142-149 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2014.12.004Influence of temperature and dry density coupled effects on HTO, 36Cl, 85Sr and 133Ba diffusion through compacted bentonite

. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 176,Long-term diffusion of U(VI) in bentonite: Dependence on density

. Sci. Total Environ. 575, 207-218 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.005Effect of the formation of EDTA complexes on the diffusion of metal ions in water

. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 71, 4416-4424 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2007.07.009The authors declare that they have no competing interests.