Introduction

Relativistic heavy-ion collisions create a unique environment where a quark-gluon plasma with strong collectivity is formed [1-8], accompanied by the strongest known magnetic field generated by spectator protons from the colliding nuclei [9-16]. This environment provides an ideal laboratory for studying the topological properties of the QCD vacuum and anomalous chiral transport phenomena under extreme magnetic field conditions. The chiral magnetic effect (CME), which induces electric charge separation along the magnetic field direction in systems with chiral imbalances, is crucial for detecting these phenomena [17-19].

The charge-dependent azimuthal correlation

Numerous experimental observables have been employed to detect true CME signals while minimizing the background interference in Au+Au and isobar collisions. For this purpose, a two-plane measurement method utilizing charge-dependent azimuthal correlations relative to the spectator plane (SP) and participant plane (PP) was proposed [60, 61]. This method is based on the fact that background and CME signals exhibit different sensitivities or correlations to the two planes [62]. The STAR collaboration applied this method to quantify the fraction of the CME signal within the inclusive Δγ correlation in both Au+Au and isobar collisions. For Au+Au collisions at

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe the setup of the AMPT model with an initial CME signal and outline our two-plane method for extracting the fraction of the CME signal from the inclusive Δγ. Our model results are presented and compared with measurements from the STAR experiment in Sect. 3, in which we discuss the implications of our findings for the interpretation of the experimental data and possible physical sources. Finally, Sect. 4 summarizes the main conclusions of the study.

Model and method

The AMPT model with initial CME signal

The AMPT model is a multiphase transport framework designed to simulate the four main stages of relativistic heavy-ion collisions [65-67], which includes the following components:

(1) The HIJING model provides the initial conditions. The transverse density profile of the colliding nucleus is modeled as a Woods–Saxon distribution. Multiple scatterings among the participant nucleons generate the spatial and momentum distributions of minijet partons and soft excited strings. Using a string-melting mechanism, quark plasma is generated by melting the parent hadrons.

(2) Zhang’s parton cascade (ZPC) model simulates the parton cascade stage. The ZPC model describes parton interactions via two-body elastic scattering. The parton cross-section is calculated using leading-order pQCD for gluon–gluon interactions.

(3) A quark coalescence model combines two or three nearest quarks into hadrons to simulate hadronization.

(4) A relativistic transport (ART) model simulates the stage of hadronic rescatterings, including resonance decays and all hadronic reactions involving elastic and inelastic scatterings among baryon–baryon, baryon–meson, and meson–meson interactions.

Numerous previous studies have demonstrated that the AMPT model effectively describes various experimental observables in both large and small collision systems at the RHIC and LHC [65-74].

According to the methodology described in Ref. [75], we implemented a CME-like charge separation mechanism in the initial partonic stage of the AMPT model. The CME signal strength can be controlled by adjusting the percentage p, which defines the fraction of quarks participating in the CME-like charge separation. The percentage p is defined as follows:

Spectator and participant planes

The two-plane method utilizes distinct plane correlations, that is, the elliptical flow-driven background is predominantly correlated with the PP, whereas the CME signal exhibits a stronger correlation with the SP [60, 61]. The SP and PP can be reconstructed using the following equations:

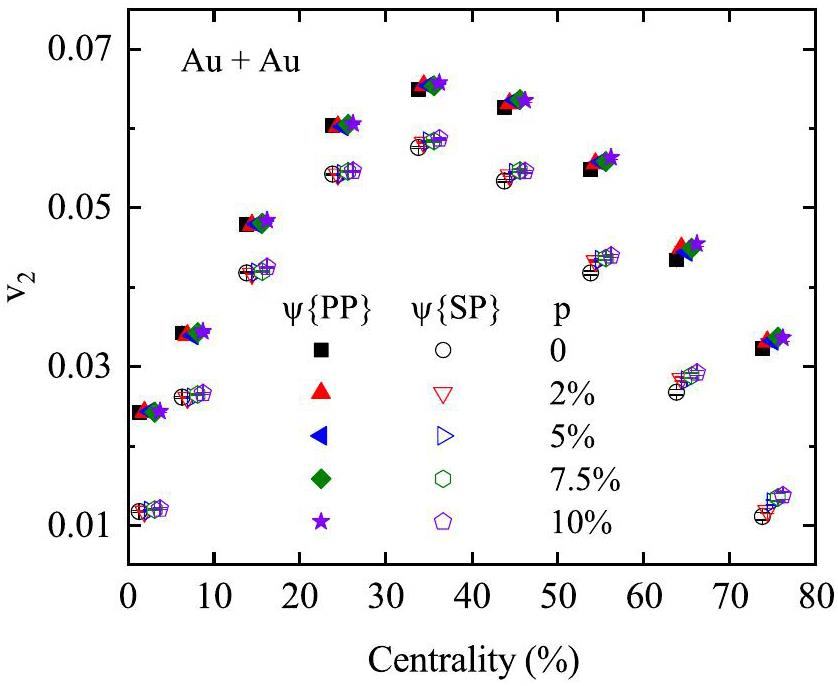

Figure 1 presents the centrality dependence of v2{PP} and v2{SP} for charged hadrons with 0.2<pT<2.0 GeV / c and |η|<1, obtained from the AMPT model with varying CME strengths in Au+Au collisions at

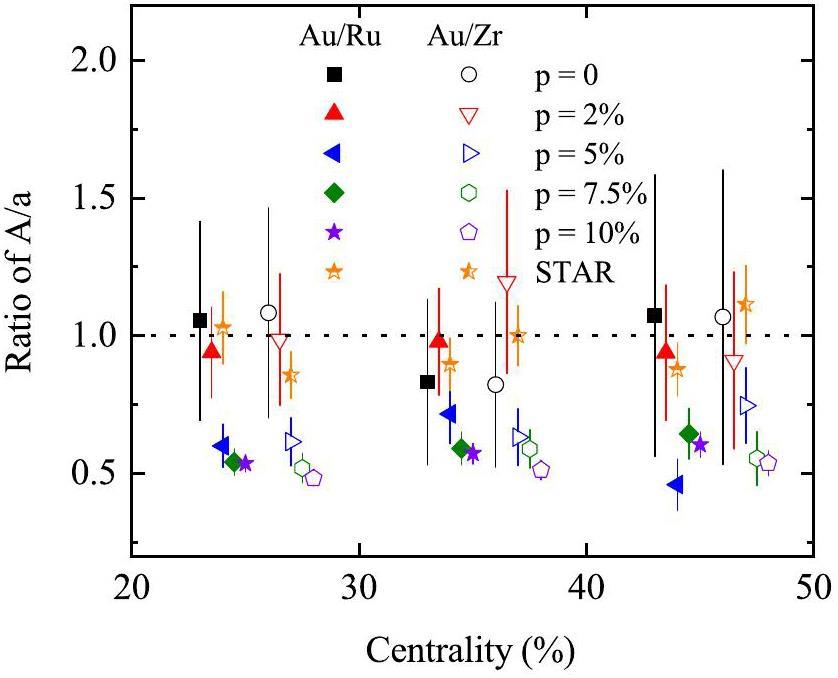

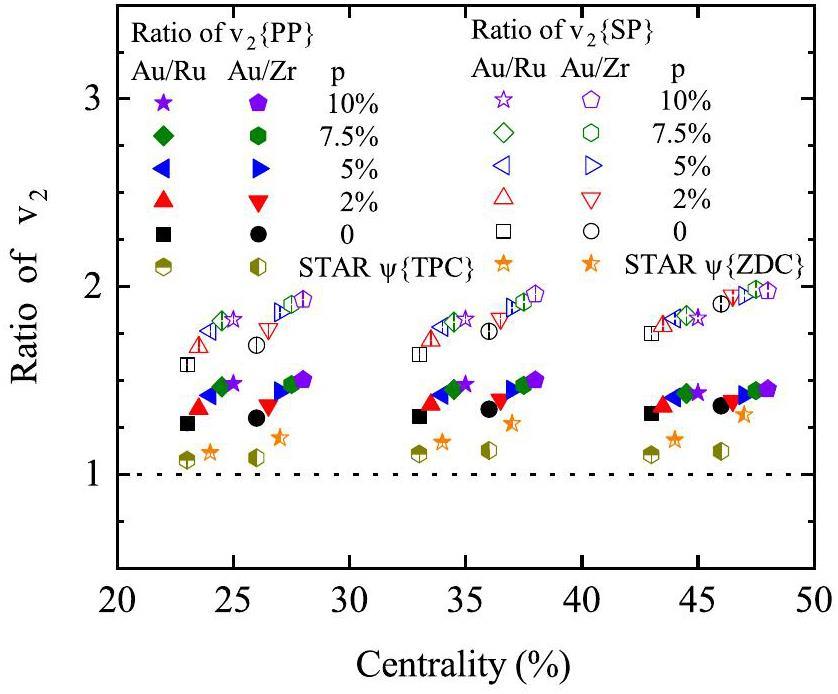

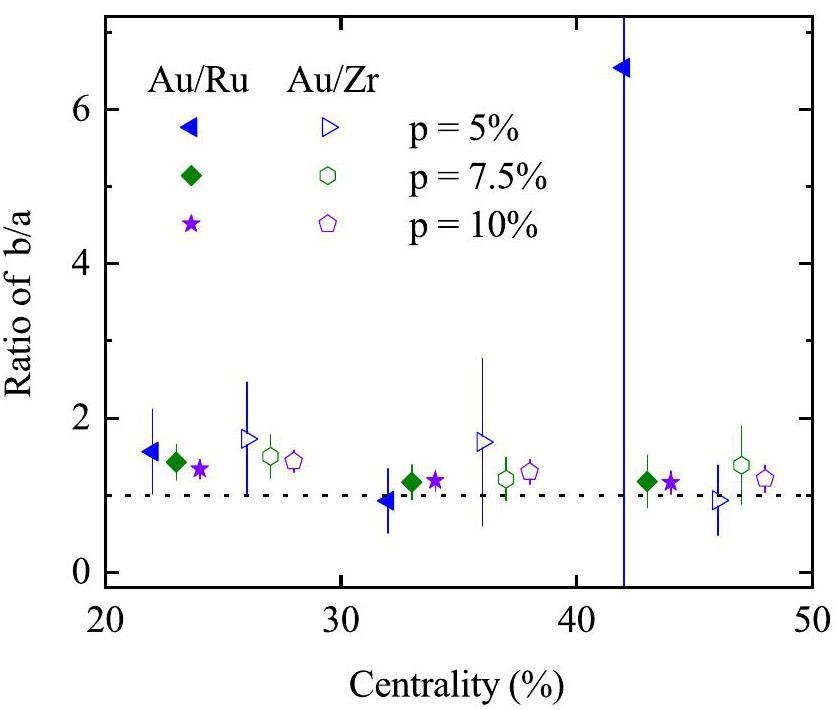

Figure 2 shows the ratios of v2{PP} and v2{SP} for Au+Au collisions relative to Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions. Note that all the calculations for the Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions were taken from Ref. [64]. Because the CME is more likely to occur at centrality bins of 20–50%, and to avoid large errors, the comparison is restricted to these centrality bins. The ratio of v2{PP} is larger than that of v2{SP}, which is consistent with the experimental trends. Compared with the experimental data, a relatively larger ratio in our results arises because the v2{PP} and v2{SP} values calculated from our isobar collision simulations are smaller than the experimental results. Similarly, the v2{PP} and v2{SP} ratios of Au+Au to Ru+Ru collisions are smaller than those of Au+Au to Zr+Zr collisions, reflecting the influence of the nuclear structure. This indicates that the v2{PP} and v2{SP} values for Ru+Ru collisions are larger than those for Zr+Zr collisions owing to the nuclear structure effect [54, 64]. In the 20–50% centrality bin, the changes in v2{PP} and v2{SP} values for Au+Au collisions are mere; however, in isobar collisions, the v2{PP} and v2{SP} values decrease with increasing p [64], resulting in an increase in the v2{PP} and v2{SP} ratio with the strength of the CME.

Two-plane method to extract fCME

This subsection presents the original two-plane method for detecting and extracting the fraction of the CME signal and its optimization using the AMPT model. The experimentally measurable CME observable, denoted as Δγ, consists of the CME signal and background effect. These background effects are predominantly attributed to the elliptic flow and non-flow effects, which originate from the resonance decays and jet correlations. Consequently, the experimentally measured observable with respect to different planes can be mathematically expressed as the sum of two components:

Results and Discussions

This section presents the AMPT model results, focusing on the charge-dependent azimuthal correlations for charged particles relative to both the SP and PP. For comparison with the measurements from the STAR experiment, we used kinetic cuts of 0.2<pT<2.0 GeV/c and |η|<1, which are consistent with the STAR experimental setup.

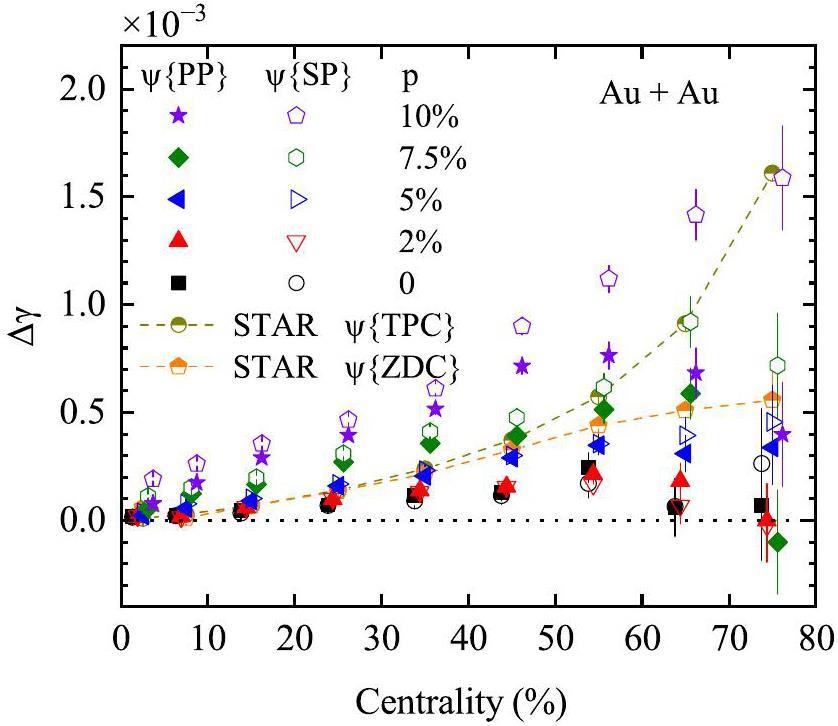

Figure 3 shows the centrality dependence of Δγ{PP} and Δγ{SP} from the AMPT model with varying CME strengths in Au+Au collisions at

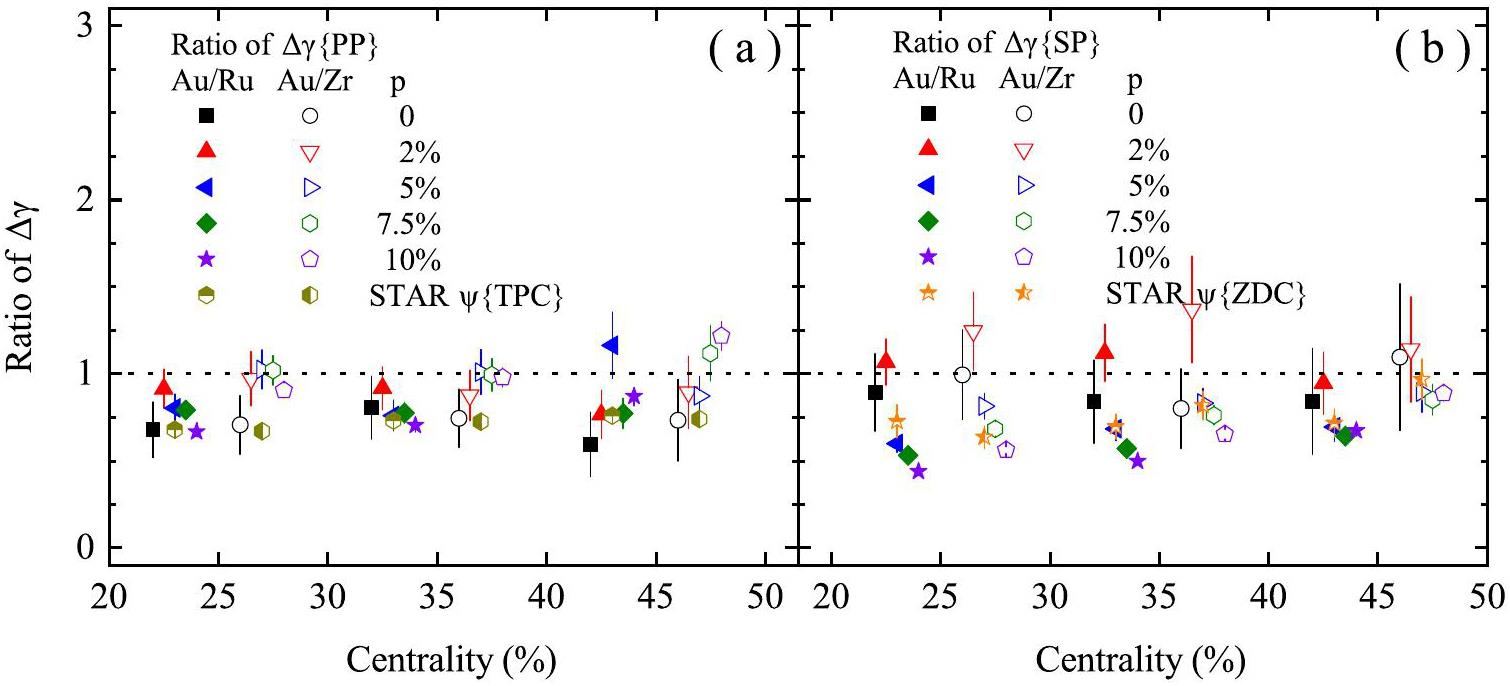

Figure 4(a) and (b) present the centrality dependence of the Δγ{PP} and Δγ{SP} ratios for Au+Au collisions relative to the Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions, respectively. Considering the effect of errors, both the experimental and theoretical results indicate that the Δγ value for Au+Au collisions is smaller than that for isobar collisions, because most of the ratios are less than one. For the ratio of Δγ{PP} in Fig. 4(a), the AMPT results without the CME signal agree closely with the experimental results, whereas for the ratio Δγ{SP} in Fig. 4(b), the AMPT results with the CME signal show better agreement with the experimental results. As the CME signal correlates more strongly with the SP than with the PP, we observe that the ratio of Δγ{SP} in Fig. 4(b) decreases with increasing CME strength. This suggests that Δγ{SP} in isobar collisions increases more rapidly than that in Au+Au collisions as the CME strength increases.

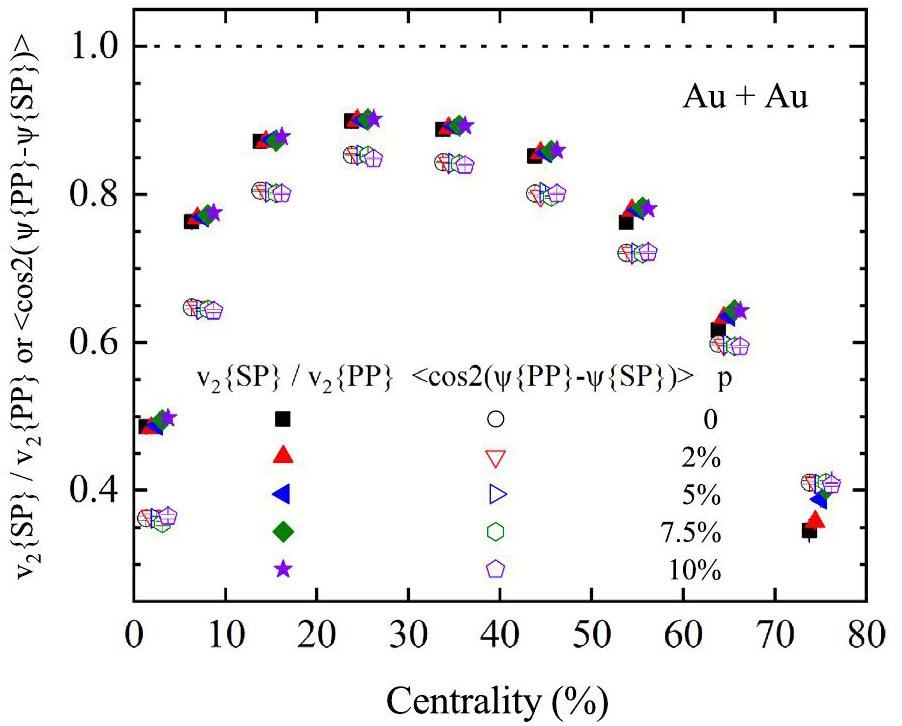

Figure 5 shows the centrality dependence of

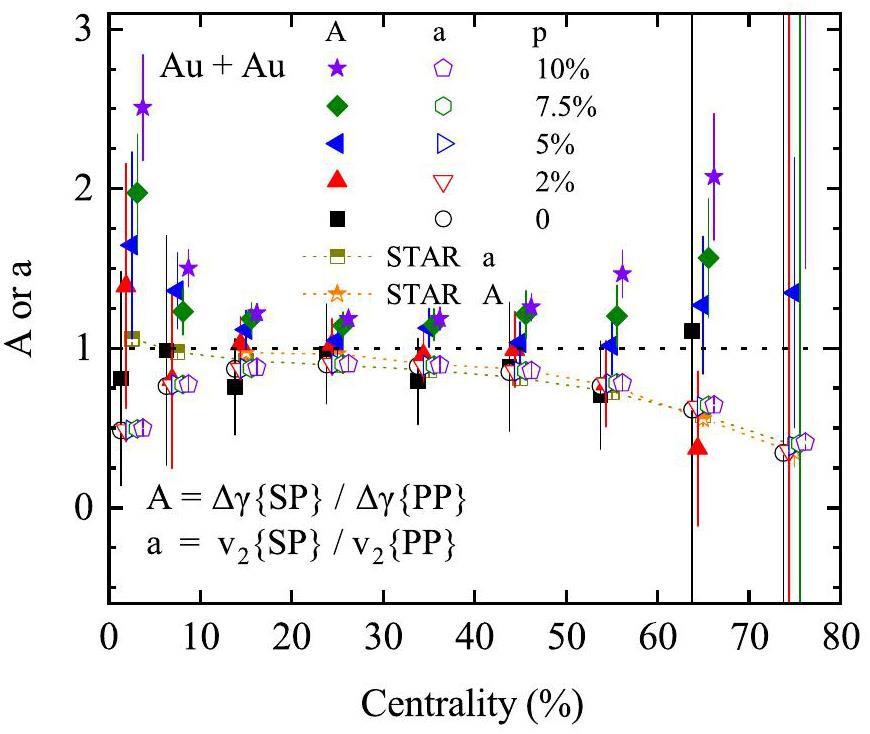

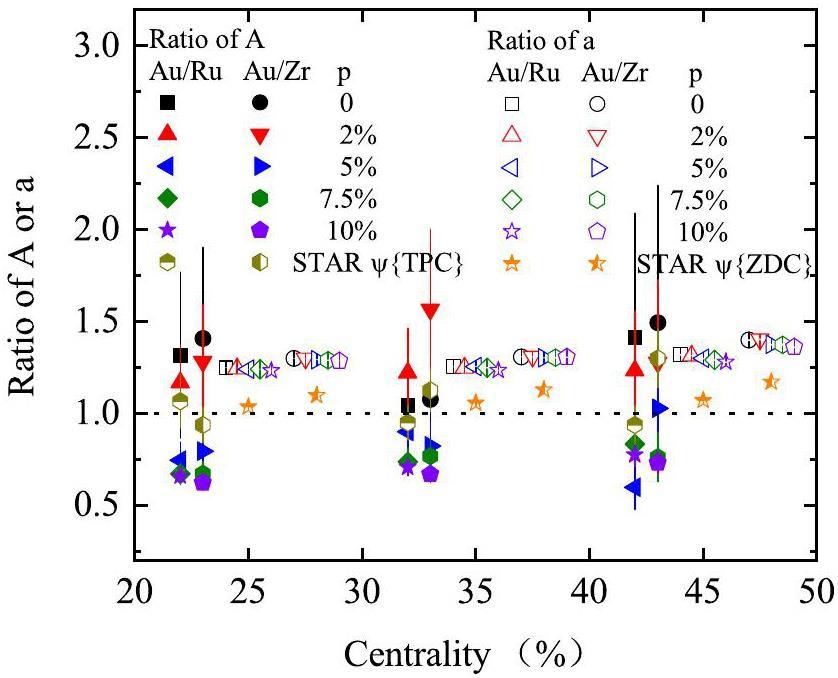

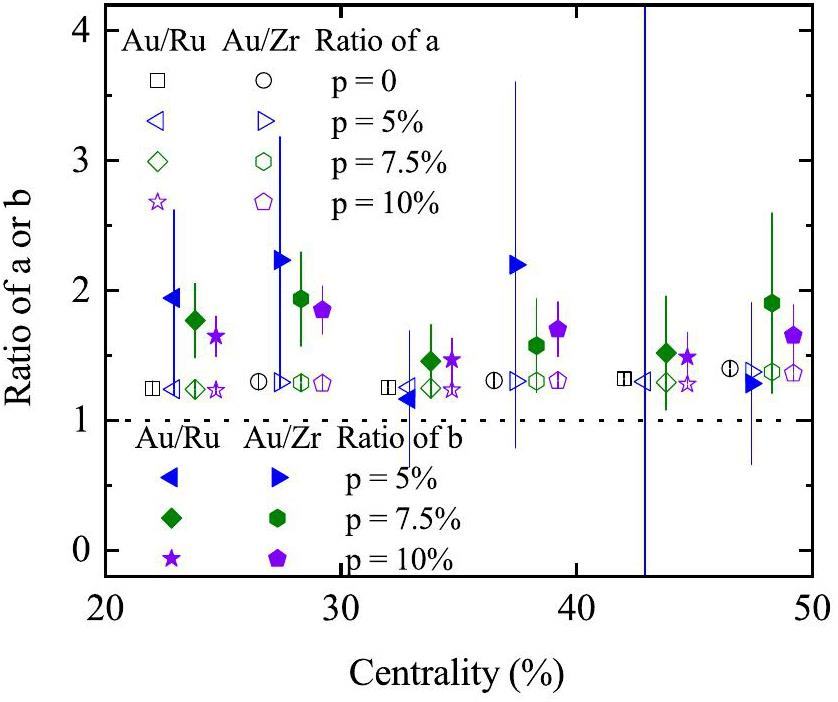

Figure 7 shows the centrality dependence of the A and a ratios for Au+Au collisions relative to Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions, respectively. The ratio of a remains nearly unchanged, which is consistent with the experimental data within error. An a ratio greater than one indicates that the

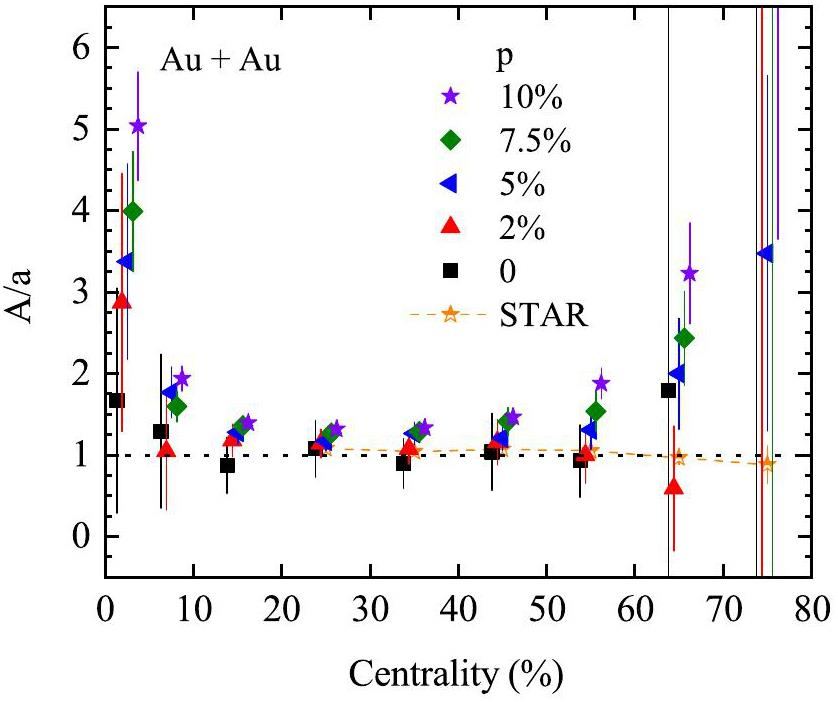

Figure 8 shows A/a as a function of the centrality predicted by the AMPT model with varying CME strengths. According to Eqs. (9) and (12), A/a values greater than unity indicate the presence of a CME signal within the Δγ observable. Focusing on mid-central collisions (20–50% centrality), where the CME effect is more measurable, A/a>1 is observed for all cases except when p=0 and p=2%. Notably, A/a increases with CME strength, suggesting that this ratio reflects the strength of the CME signal. The experimental data are closer to the cases with lower strengths of the CME signal.

Figure 9 shows the centrality dependence of the A/a ratios for Au+Au collisions relative to Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions. Focusing on mid-central collisions (20–50% centrality), the A/a ratios for the Au+Au and isobar collisions exhibit a trend similar to that of the A ratio shown in Fig. 7, driven by a smaller variation in a and larger variation in A. The experimental data are also closer to the cases with lower strengths of the CME signal.

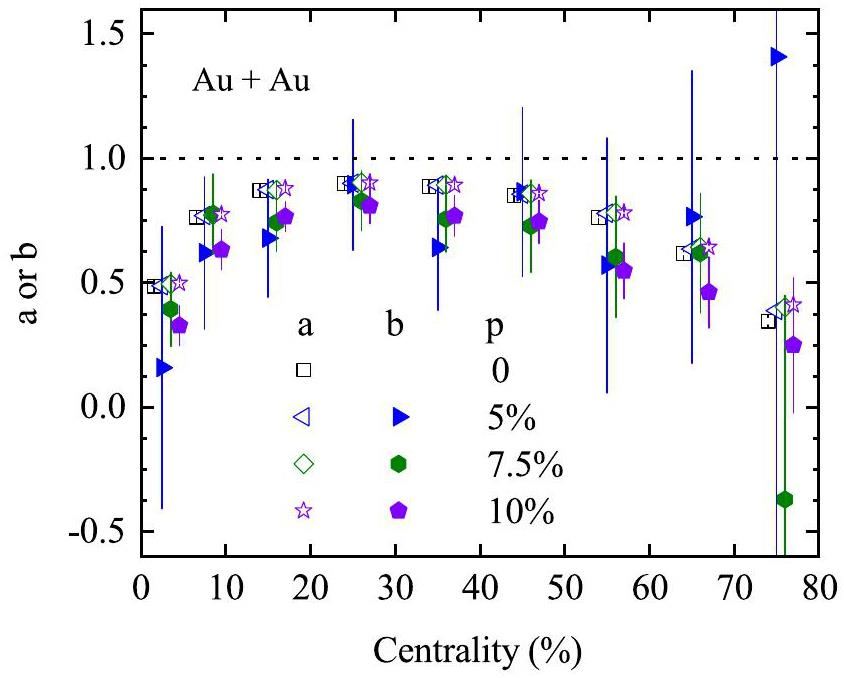

Figure 10 shows the centrality dependence of a and b calculated using Eq. (13), based on the AMPT model with varying CME strengths. Notably, a and b exhibit significant differences. In the 20–50% centrality bins, b remains consistently smaller than a. Moreover, a shows minimal dependence on CME strength, as presented in Fig. 5. By contrast, b reflects the capability of the PP method to capture the CME signal observed in the SP method. Although the statistical errors are substantial, b shows no significant variation with CME strengths, except for the 2% CME strength case, which is excluded because of its large statistical uncertainties.

Figure 11 shows the centrality dependence of the a and b ratios for Au+Au collisions relative to Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions, respectively, based on the AMPT model with various CME strengths. Focusing on the 20–50% centrality bins, the a ratio remains nearly unchanged and is smaller than the b ratio. The uncertainties of b ratios are large. According to Eq. (13), a larger b value indicates a smaller difference in the net CME strength between the two planes. Therefore, our results indicate that the difference is smaller in Au+Au collisions than in isobar collisions.

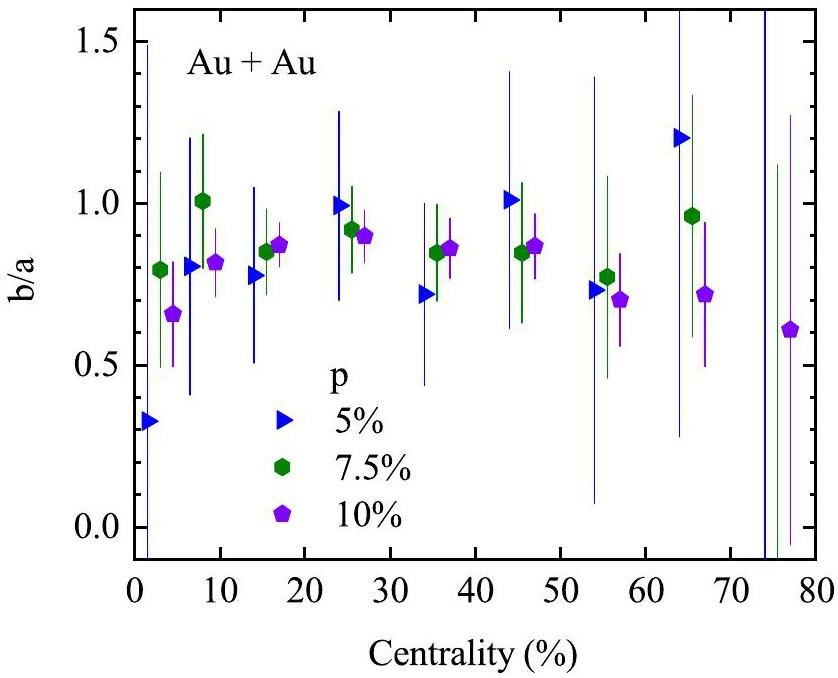

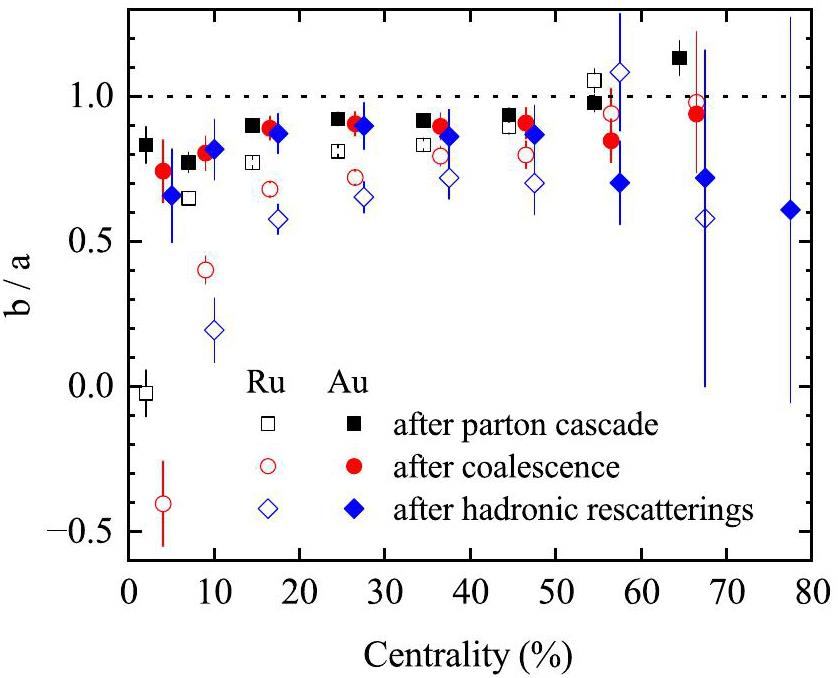

Figure 12 shows the centrality dependence of the b/a ratio as predicted by the AMPT model with varying CME strengths. Focusing on the 20–50% centrality bins in Au+Au collisions at

Figure 13 shows the centrality dependence of b/a for Au+Au collisions relative to Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions, respectively, based on the AMPT model with varying CME strengths. Because the value of

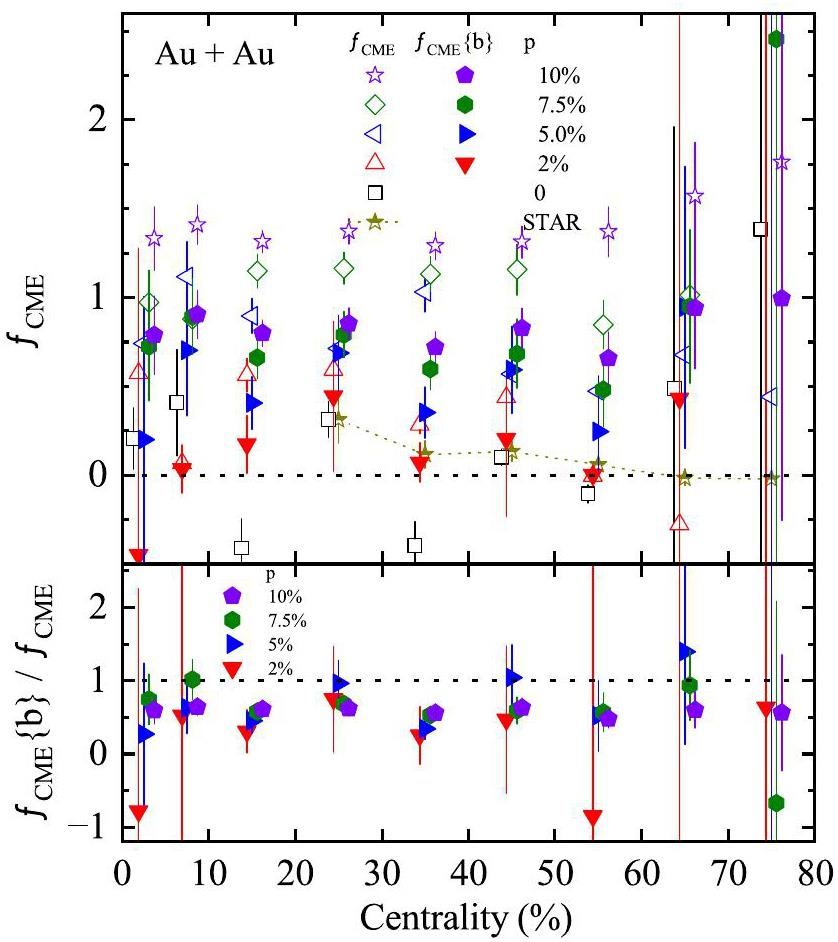

The upper panel of Fig. 14 shows the centrality dependence of the two types of fCME based on the AMPT model with varying CME strengths. The open and solid symbols represent fCME and fCME{b} calculated using Eqs. (9) and (12), respectively. Our results are consistent with the STAR experimental data [32], favoring the cases of p=0% and p=2%. Notably, for the 20–50% centrality bins, when

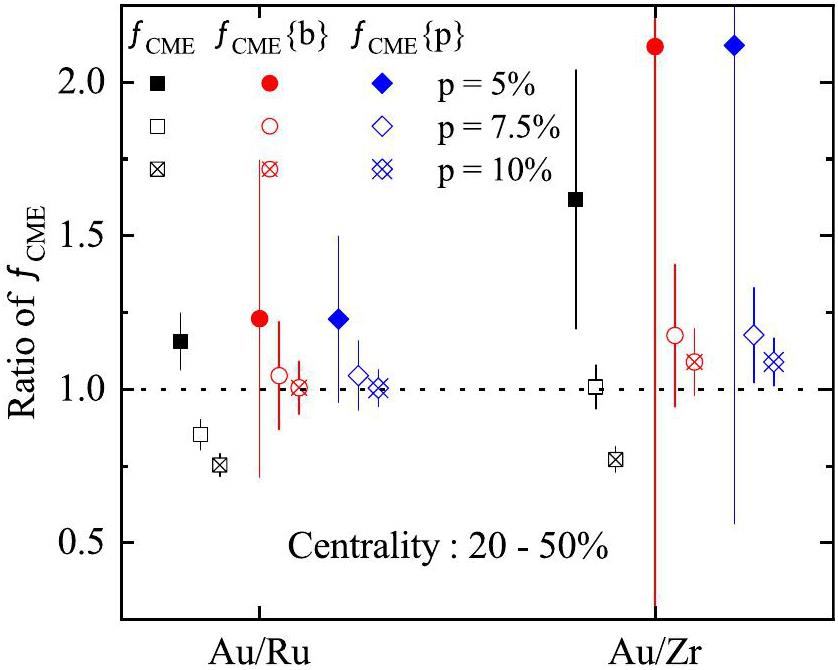

Figure 15 shows the fCME, fCME{b}, and fCME{p} ratios for Au+Au collisions relative to Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions, respectively, in the 20–50% centrality bins at

As the introduced CME signal strength increases, the ratios calculated using all the three methods decrease. This is because the A/a value increases more significantly in isobar collisions than in Au+Au collisions, leading to a reduction in the calculated ratios. It is also observed that the Au/Ru ratio is smaller than the Au/Zr ratio in the presence of CME signals, indicating that the fraction of CME signal is higher in Ru+Ru than in Zr+Zr.

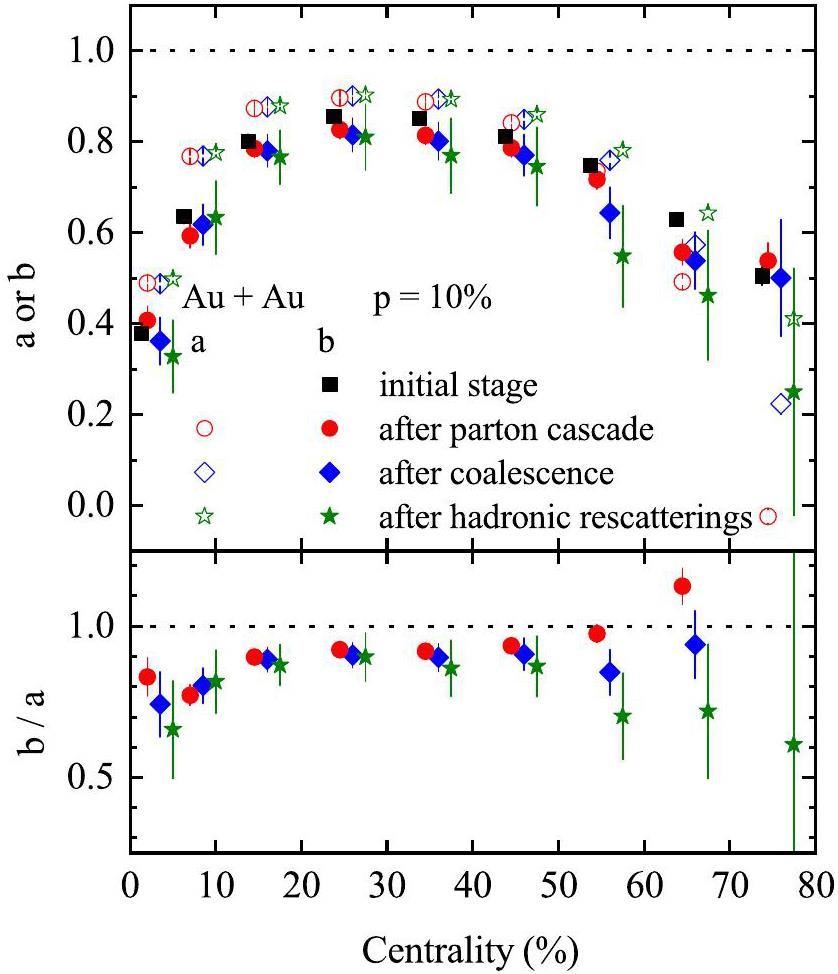

The preceding results demonstrate that the ratio b/a = 0.88(± 0.08) significantly influences the final result of fCME in the 20–50% centrality bins for Au+Au collisions. To elucidate the origin of this relationship, we investigated the evolution of a and b at different stages of the Au+Au collisions at

In Ref. [75], the authors demonstrated that the final-state interactions in relativistic heavy-ion collisions significantly suppress the initial charge separation, with a reduction factor reaching up to an order of magnitude. In our previous work [64], we found that, because of the anisotropic overlap zone, these interactions not only reduce the magnitude of the CME current but also alter its direction, resulting in a modified maximum current orientation. Figure 17 shows the centrality dependence of the b/a ratio in the Ru+Ru [64] and Au+Au collisions at

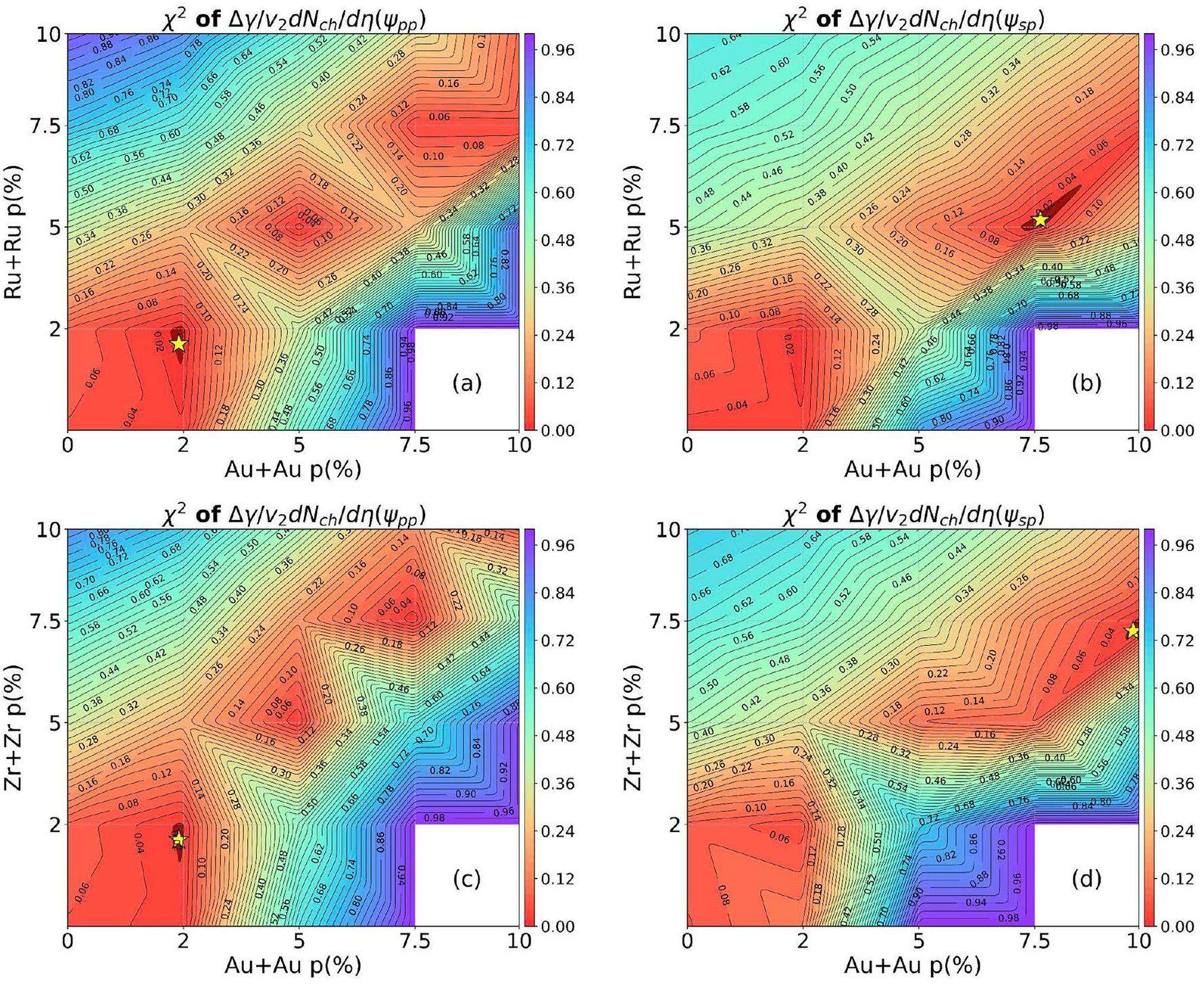

To constrain the CME strengths across Au+Au and isobar collisions simultaneously, we performed a chi-square analysis using the following method. We aimed to compare the CME observable between our results with different CME strengths and the experimental data for those three collision systems simultaneously. The chi-square for a CME observable O in centrality bin i is defined as follows:

Summary

Using a multiphase transport model with varying CME strengths, we extended our two-plane method analysis from isobar to Au+Au collisions, both at

Anisotropic transverse flow and the quark hadron phase transition

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Flow at the SPS and RHIC as a quark gluon plasma signature

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4783-4786 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.4783A flow paradigm in heavy-ion collisions

. Chin. Phys. C 42,Recent development of hydrodynamic modeling in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 122 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00829-zCollective flow and hydrodynamics in large and small systems at the LHC

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 99 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0245-4Anisotropic flow in high baryon density region

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01006-0Dynamically Exploring the QCD Matter at Finite Temperatures and Densities: A Short Review

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38,Properties of QCD matter: a review of selected results from ALICE experiment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01583-2Estimate of the magnetic field strength in heavy-ion collisions

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 24, 5925-5932 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217751X09047570Event-by-event fluctuations of magnetic and electric fields in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 710, 171-174 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.02.065Event-by-event generation of electromagnetic fields in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Electromagnetic fields in small systems from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Novel mechanism for electric quadrupole moment generation in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 792, 413-418 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.04.002Electromagnetic fields from the extended Kharzeev-McLerran-Warringa model in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 1011,A systematical study of the chiral magnetic effects at the RHIC and LHC energies

. Chin. Phys. C 44,Electromagnetic fields in ultra-peripheral relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 20 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01374-9Parity violation in hot QCD: Why it can happen, and how to look for it

. Phys. Lett. B 633, 260-264 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2005.11.075The Effects of topological charge change in heavy ion collisions: ’Event by event P and CP violation’

. Nucl. Phys. A 803, 227-253 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.02.298The Chiral Magnetic Effect

. Phys. Rev. D 78,Parity violation in hot QCD: How to detect it

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Azimuthal Charged-Particle Correlations and Possible Local Strong Parity Violation

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103,Observation of charge-dependent azimuthal correlations and possible local strong parity violation in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Fluctuations of charge separation perpendicular to the event plane and local parity violation in sNN=200 GeV Au+Au collisions at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Beam-energy dependence of charge separation along the magnetic field in Au+Au collisions at RHIC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113,Charge separation relative to the reaction plane in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Azimuthal correlations from transverse momentum conservation and possible local parity violation

. Phys. Rev. C 83,On the Charge Separation Effect in Relativistic Heavy Ion Collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Charge conservation at energies available at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and contributions to local parity violation observables

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Effects of Cluster Particle Correlations on Local Parity Violation Observables

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Global constraint on the magnitude of anomalous chiral effects in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Measurement of charge multiplicity asymmetry correlations in high-energy nucleus-nucleus collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Search for the Chiral Magnetic Effect via Charge-Dependent Azimuthal Correlations Relative to Spectator and Participant Planes in Au+Au Collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Search for the chiral magnetic effect in heavy ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 179 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0520-zExperimental searches for the chiral magnetic effect in heavy-ion collisions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 107, 200-236 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2019.05.001Search for CME in U+U and Au+Au collisions in STAR with different approaches of handling backgrounds

. Nucl. Phys. A 1005,CME — Experimental Results and Interpretation

. Acta Phys. Polon. Supp. 16, 1-A15 (2023). https://doi.org/10.5506/APhysPolBSupp.16.1-A15Two- and three-particle nonflow contributions to the chiral magnetic effect measurement by spectator and participant planes in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Chiral Magnetic Effects in Nuclear Collisions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 70, 293-321 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-030220-065203Progress on the experimental search for the chiral magnetic effect, the chiral vortical effect, and the chiral magnetic wave

. Acta Phys. Sin. 72,Event shape selection method in search of the chiral magnetic effect in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 848,Detecting the chiral magnetic effect via deep learning

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Testing the Chiral Magnetic Effect with Central U+U collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,Test the chiral magnetic effect with isobaric collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Upper limit on the chiral magnetic effect in isobar collisions at the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. Res. 6,Estimate of background baseline and upper limit on the chiral magnetic effect in isobar collisions at sNN=200 GeV at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Properties of the QCD matter: review of selected results from the relativistic heavy ion collider beam energy scan (RHIC BES) program

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01591-2Determine the neutron skin type by relativistic isobaric collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 819,Probing nuclear structure with mean transverse momentum in relativistic isobar collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Evidence of Quadrupole and Octupole Deformations in Zr96+Zr96 and Ru96+Ru96 Collisions at Ultrarelativistic Energies

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Scaling approach to nuclear structure in high-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Impact of Nuclear Deformation on Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collisions: Assessing Consistency in Nuclear Physics across Energy Scales

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Shape of atomic nuclei in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Probing triaxial deformation of atomic nuclei in high-energy heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Search for the chiral magnetic effect in collisions between two isobars with deformed and neutron-rich nuclear structures

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Impact of nuclear structure on the background in the chiral magnetic effect in 4496Ru + 4496Ru and 4096Zr + 4096Zr collisions at sNN=7.7∼200 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Imaging the initial condition of heavy-ion collisions and nuclear structure across the nuclide chart

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 220 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01589-wImpact of initial fluctuations and nuclear deformations in isobar collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01480-8Evolution of topological charge through chiral anomaly transport

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Exploring the chiral magnetic effect in isobar collisions through Chiral Anomaly Transport

. arXiv:2412.09130Varying the chiral magnetic effect relative to flow in a single nucleus-nucleus collision

. Chin. Phys. C 42,Importance of isobar density distributions on the chiral magnetic effect search

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Impact of magnetic-field fluctuations on measurements of the chiral magnetic effect in collisions of isobaric nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Anomalous Chiral Transport in Heavy Ion Collisions from Anomalous-Viscous Fluid Dynamics

. Annals Phys. 394, 50-72 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aop.2018.04.026Difference between signal and background of the chiral magnetic effect relative to spectator and participant planes in isobar collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 109,A Multi-phase transport model for relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Predictions for sNN=5.02 TeV Pb+Pb Collisions from a Multi-Phase Transport Model

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Further developments of a multi-phase transport model for relativistic nuclear collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00944-5Evolution of transverse flow and effective temperatures in the parton phase from a multi-phase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Azimuthal anisotropy relative to the participant plane from a multiphase transport model in central p + Au, d + Au, and 3He + Au collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Flow in small systems from parton scatterings

. Nucl. Phys. A 956, 745-748 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2016.01.057Improved Quark Coalescence for a Multi-Phase Transport Model

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Study on higher moments of net-charge multiplicity distributions using a multiphase transport model

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Dynamical development of proton cumulants and correlation functions in Au+Au collisions at sNN=7.7 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Probing fluctuations and correlations of strangeness by net-kaon cumulants in Au+Au collisions at sNN=7.7 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Effects of final state interactions on charge separation in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 700, 39-43 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2011.04.057Methods for analyzing anisotropic flow in relativistic nuclear collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 58, 1671-1678 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.1671Initial fluctuation effect on harmonic flow in high-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Parton collisional effect on the conversion of geometry eccentricities into momentum anisotropies in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Influence of initial-state momentum anisotropy on the final-state collectivity in small collision systems

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Search for the chiral magnetic effect with isobar collisions at sNN=200 GeV by the STAR Collaboration at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Azimuthally fluctuating magnetic field and its impacts on observables in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 718, 1529-1535 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.12.030Signatures of Chiral Magnetic Effect in the Collisions of Isobars

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125,Sensitivity analysis for observables of the chiral magnetic effect using a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Quantum color screening in external magnetic field

. Phys. Rev. D 107,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.