Introduction

In 1928, α-decay was first described as a quantum mechanical tunneling effect by Gurney and Condon [1] and Gamow [2]. Within Gamow’s picture, the α cluster is preformed in the parent nucleus before it travels through a potential barrier. α-decay has been used as an important tool for understanding nuclear structure. Experimentally, because α-decay is the dominant decay mode of superheavy nuclei, detecting α-decay chains of synthesized superheavy nuclei (SHN) is an important method for identifying them. Consequently, α-decay remains a prominent and active area of study in nuclear physics [3-5].

Many empirical formulas have been proposed to study α-decay half-live. The earliest law for α-decay half-lives was formulated by Geiger and Nutall [6], which states that the logarithm of α-decay half-lives log

In Refs. [23-30], the authors demonstrated that the deformation of nuclei plays an essential role in α-decay. The total energy, fission barrier, and Coulomb interaction of nuclei have been recalculated by incorporating deformation effects. The penetration probability of α particles is affected by the deformation effects [31]. The deformation and orientation of the daughter nucleus can change the slope and intercept of the linear relationship between

Recently, machine learning (ML) algorithms have been used as powerful alternative tools for studying and predicting complex data in nuclear physics [34, 35]. In nuclear structure, ML is used to predict nuclear masses, binding energies, charge radii, etc. [36-49]. ML is a valuable tool for constructing predictive models for nuclear reactions. These models help describe and infer important nuclear reaction data, such as refining the description of reaction data, exploring the initial state of nuclei and reaction geometry, and understanding the reaction mechanism and phase transition [50-53]. Additionally, ML has several advantages in nuclear experiments and the study of dense matter properties [54-59]. Motivated by these advancements, we applied ML to investigate α-decay half-lives of known and unknown nuclei, demonstrating the advantage of this approach in studying α-decay half-lives. In this study, the XGBoost model, which is a powerful and efficient ML algorithm based on gradient boosting decision trees, was employed to further reduce the deviations between experimental and calculated α-decay half-lives of nuclei with

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, a theoretical method for deducing the improved formula and XGBoost model is presented. The results and discussion are presented in Sect. 3. Finally, a brief summary is presented in the final section.

Theoretical framework

Improved formula incorporating deformation effect

In 1928, α-decay was described as a quantum tunneling phenomenon through the potential barrier. In the framework of the semiclassical approximation, the α-decay width (or decay constant) is given by

The deformed Coulomb potential [25, 60] is given by

Similarly, F2 can be expressed as

To compare the calculated results from Eq. (16) with those obtained when the quadrupole deformation of the daughter nuclei is not taken into account, Eq. (16) becomes

Methodology of eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) for α-decay half-lives

The XGBoost algorithm is an ensemble ML algorithm that operates within a gradient boosting framework. It utilizes gradient-boosted decision trees, a technique that significantly enhances performance and speed compared with traditional methods. This algorithm efficiently handles classification, regression, and ranked objective functions and offers a more effective solution than its counterparts, such as Decision Trees (DTs) and Random Forests (RFs). In gradient boosting, a series of weak learners or models are combined to create a robust final model, which is derived by considering the weighted sum of all learned models. XGBoost excels in handling small-to-medium-sized, structured, or low-dimensional datasets, making it suitable for various ML problems.

In contrast to the regularized greedy forest model, XGBoost introduces a unique regularized learning objective. This objective is notable for its simplicity, which enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of the model. The predictive function of XGBoost, a key component of this approach, is expressed as follows:

To address overfitting, a penalty function is introduced to regularize the learning weights as follows:

In the context of α-decay half-lives, XGBoost considers the experimental α-decay half-lives as the ground truth and learns from the residuals between these data and the predictions made by the empirical formulas in Eqs. (17) and (16). This residual-based learning allows the model to implicitly account for missing physical factors, such as shell effects. The input features include the quadrupole deformation values (β2) of the daughter nucleus derived from the WS4 and FRDM models, along with the reduced mass (μ) of the α-core system, proton numbers (Zd, Zc) of the daughter nucleus and α cluster, α-decay energy, and other relevant nuclear properties. These features allow the model to identify complex correlations, such as those related to magic and sub-magic numbers, that are not encoded in empirical formulas. Owing to these advantages, XGBoost enhances the ability to capture nonlinear relationships and systematic discrepancies, particularly in regions where empirical formulas typically fail, such as near-shell closures. The XGBoost model is formulated as

Results and discussion

Nuclear deformation effect on α-decay half-lives with improved formula

In this study, the α-decay half-lives of 675 nuclei were extracted, including 183 even-even nuclei, 188 even Z-odd N nuclei, 178 odd Z-even N nuclei, and 126 odd Z-odd N nuclei. The experimental α-decay half-lives, spins, and parities were obtained from the evaluated properties table NUBASE2020 [65], and the α-decay energy was obtained from the evaluated atomic mass table AME2020 [66]. The quadrupole deformation values of the daughter nuclei in Eq. (16) were obtained from the WS4 [67] and FRDM [68] mass models. For different nuclei types, the parameters in Eqs. (17) and (16) were obtained by fitting the experimental α-decay half-lives. The fitting coefficients are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. Note that the parameters in Table 1 are fitted by the experimental α-decay half-lives of the nuclei with an absolute quadrupole deformation of less than 0.1. The parameters in Tables 2 and 3 were fitted using the experimental α-decay half-lives of all nuclei.

| Nuclei | a | b | d | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Even Z-even N | 0.4052 | -1.5073 | 0 | -12.1265 |

| Even Z-odd N | 0.4101 | -1.5008 | 0.04556 | -12.6194 |

| Odd Z-even N | 0.4181 | -1.4863 | 0.05270 | -14.0310 |

| Odd Z-odd N | 0.4163 | -1.4782 | 0.04998 | -13.6438 |

| Nuclei | a | b | c1 | c2 | d | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Even Z-even N | 0.4124 | -1.5354 | -0.0072 | 0.1536 | 0 | -12.2610 |

| Even Z-odd N | 0.4138 | -1.4461 | -0.0032 | 0.0693 | 0.0453 | -14.4611 |

| Odd Z-even N | 0.4148 | -1.4657 | -0.0059 | 0.1316 | 0.0507 | -14.1217 |

| Odd Z-odd N | 0.4145 | -1.4866 | 0.0074 | -0.0178 | 0.0511 | -13.2610 |

| Nuclei | a | b | c1 | c2 | d | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Even Z-even N | 0.4117 | -1.5500 | -0.0067 | 0.1527 | 0 | -11.8213 |

| Even Z-odd N | 0.4140 | -1.4474 | -0.0031 | 0.0647 | 0.0453 | -14.4561 |

| Odd Z-even N | 0.4146 | -1.4723 | -0.0061 | 0.1420 | 0.0511 | -13.9411 |

| Odd Z-odd N | 0.4176 | -1.4695 | -0.0020 | 0.0946 | 0.0516 | -14.0118 |

To precisely compare the different formulas, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the nuclei can be calculated as follows:

| Eq. (17) | Eq. (16) | Ref. [8] | Ref. [13] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclei | σ1 | σ2 | σ3 | σ4 | σ5 | No. of nuclei |

| Even Z-even N | 0.406 | 0.363 | 0.368 | 0.376 | 0.375 | 183 |

| Even Z-odd N | 0.475 | 0.445 | 0.445 | 0.668 | 0.457 | 188 |

| Odd Z-even N | 0.469 | 0.412 | 0.409 | 0.653 | 0.425 | 178 |

| Odd Z-odd N | 0.472 | 0.432 | 0.439 | 0.634 | 0.475 | 126 |

| Total | 0.456 | 0.413 | 0.415 | 0.589 | 0.428 | 675 |

When the quadrupole deformation of the daughter nuclei in Eq. (16) is taken from the WS4 mass model, the σ values decrease from 0.406 to 0.363 for even Z-even N nuclei, from 0.475 to 0.445 for even Z-odd N nuclei, from 0.469 to 0.412 for odd Z-even N nuclei, and from 0.472 to 0.432 for odd Z-odd N nuclei. A similar trend was observed when the quadrupole deformation values were taken from the FRDM model. Among all subsets, the σ values for even Z-even N nuclei were the lowest, with σ1, σ2, and σ3 values of 0.406, 0.363, and 0.368, respectively. This can be attributed to the fact that in the α-decay of even Z-even N nuclei, the angular momentum l carried away by the α particle is always zero, eliminating the ambiguity in determining l, which is not true for other subsets. For the total dataset, the σ2 and σ3 values, when compared with the σ1 value from Eq. (17), decrease from 0.456 to 0.413 and 0.415, respectively. From the σ values, including deformation effects in the empirical formula does not significantly improve describing experimental α-decay half-lives.

Additionally, by fixing the parameters a, b, d, and h in Eq. (17), the deformation-related parameters c1 and c2 are independently fitted by the experimental α-decay half-lives. Using this approach, Eq. (16) produces σ= 0.419 and 0.421 with the quadrupole deformation values obtained from WS4 and FRDM, respectively. Compared with the values of σ2 and σ3 shown in Table 4, their σ values are higher. Hence, the results calculated from Eq. (16), where the parameters of Eq. (16) are fitted using the experimental α-decay half-lives of all nuclei, will be used in the subsequent discussions on XGBoost optimization and the prediction of α-decay half-lives for superheavy nuclei.

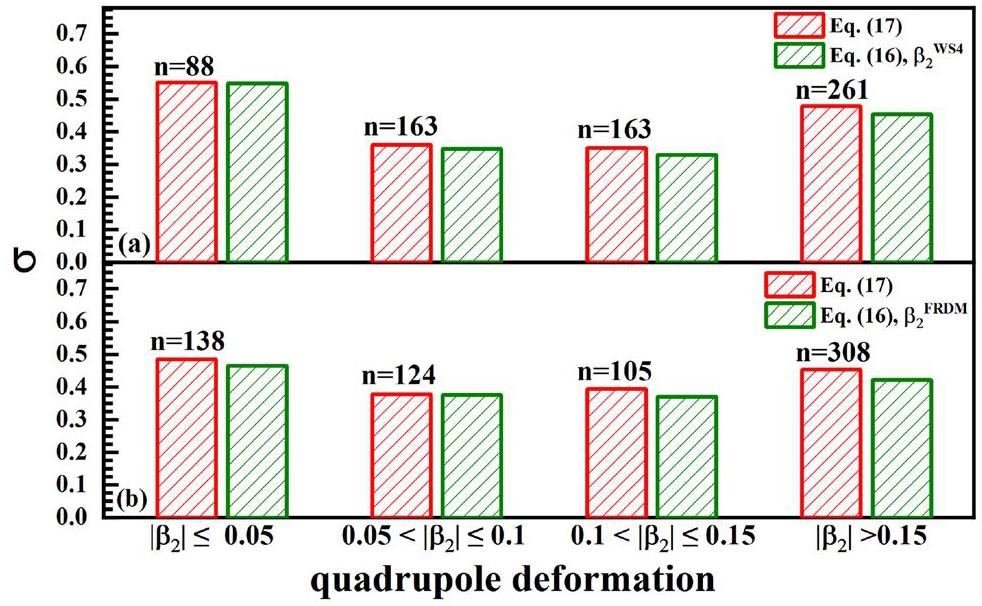

In Fig. 1, the σ deviations of Eqs. (17) and (16) across different quadrupole deformation regions are presented, with the deformation values derived from the WS4 and FRDM models, respectively. For nuclei with small deformations (

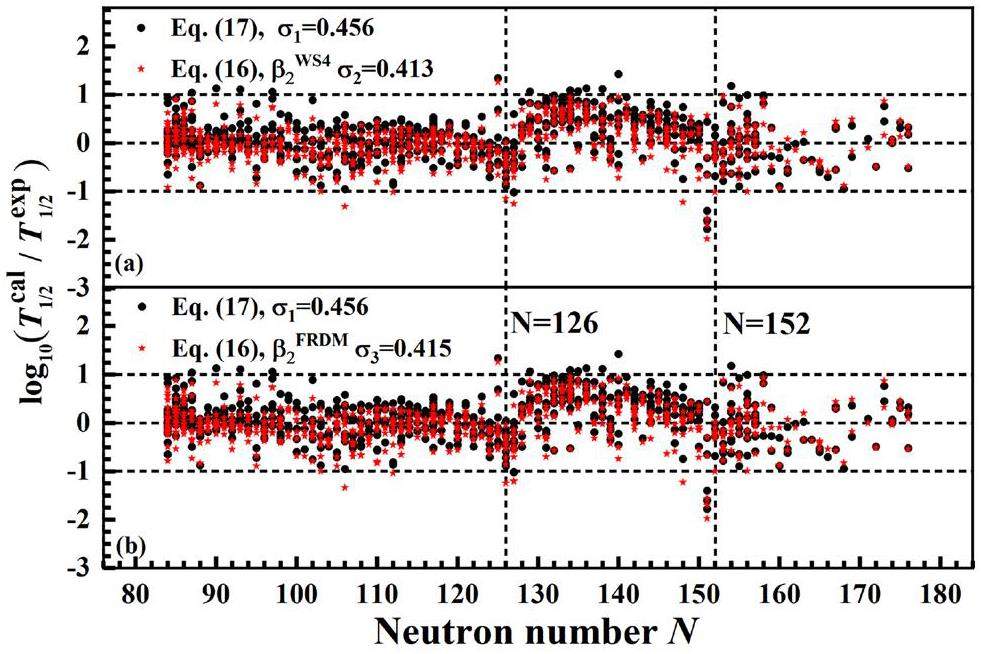

Using the RMSD as an indicator of the accuracy of the formula provides only a rough estimate of its performance. For a more detailed insight, Fig. 2 presents the logarithmic deviations between the experimental data and the results calculated using Eqs. (17) and (16). In Fig. 2(a), the black circles and red stars represent the deviations for Eqs. (17) and (16), respectively, using the deformation values from the WS4 model [67]. Similarly, Fig. 2(b) presents the same analysis using the deformation values from the FRDM model [68]. Points closer to zero indicate better agreement with experimental data, and evidently, the deviations of Eq. (16) (red stars) are more concentrated near zero than those of Eq. (17) (black circles) for both models. A notable feature in Fig. 2 is the large deviations observed near neutron numbers N = 126 and N = 152, where both formulas exhibit significant discrepancies from the experimental data. Previous studies identified N = 126 and N = 152 as magic and sub-magic numbers, respectively [69-71]. These deviations can be attributed to shell effects associated with these neutron numbers, which are not explicitly accounted for in either Eq. (17) or (16). To address this issue, in the following sections, we explore using the XGBoost algorithm to further reduce the σ values of empirical formulas, including nuclei near the magic and sub-magic numbers.

To gain further insight into the deformation effect on α-decay half-lives, we compared the improved formula of Eq. (16) with other formulas [8, 13]. The experimental data used in this study differ from those in Refs. [8] and [13]. The parameters of the empirical formulas in Refs. [8, 13] were recalibrated using the experimental data obtained in this study. This recalibration resulted in σ values of 0.589 and 0.428, respectively, which were lower than the original σ values of 0.779 and 0.429 with the parameters obtained from Refs. [8] and Ref. [13], respectively. The recalibrated σ values for the four subsets and total dataset are displayed in the fifth and sixth columns of Table 4, respectively. As indicated in the table, the improved formula of Eq. (16) exhibits smaller σ values for the entire set of data than those of the other formulas [8, 13]. This indicates that the improved formula, which incorporates the deformation effect, can be used to study α-decay half-lives.

Study on α-decay half-lives with eXtreme Gradient Boosting

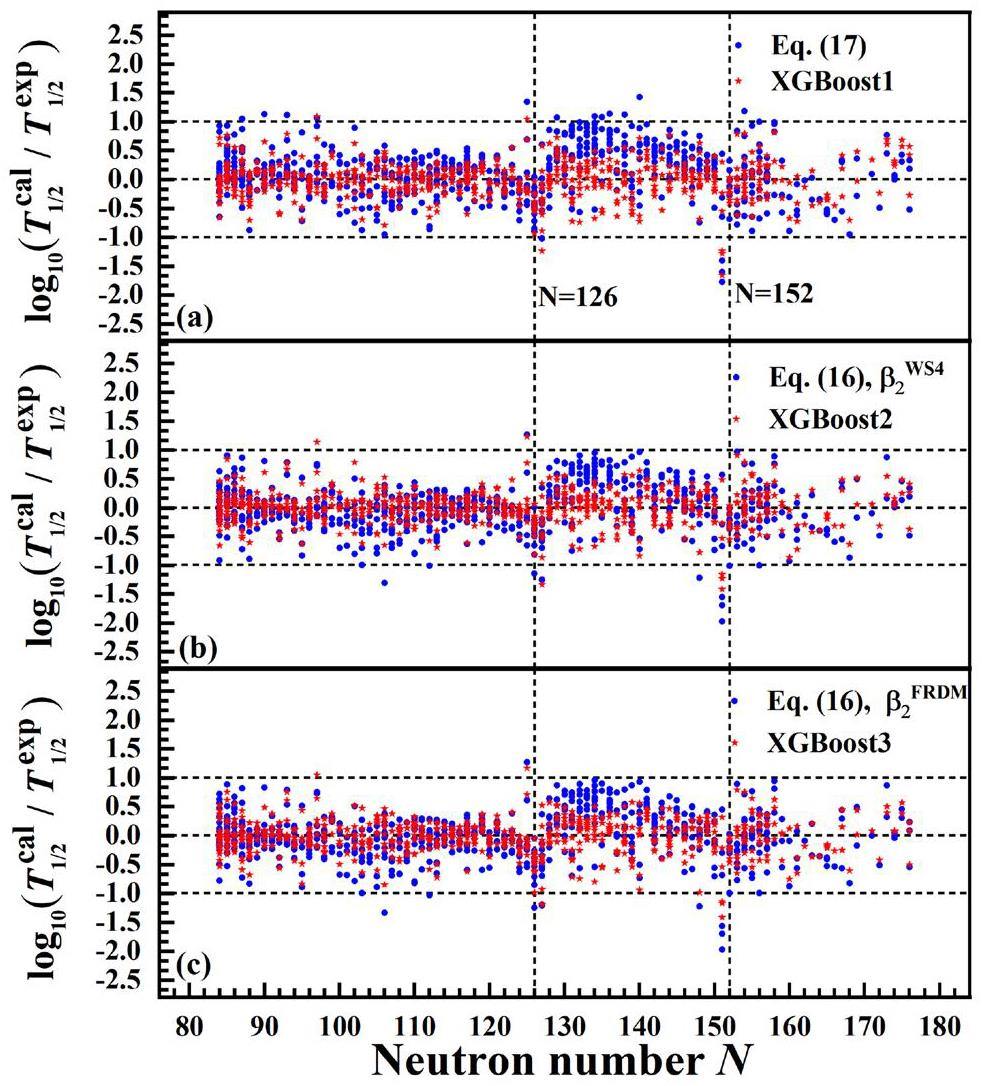

In this study, we built three XGBoost models to further improve the prediction accuracy of α-decay half-lives, denoted as XGBoost1, XGBoost2, and XGBoost3. For the XGBoost2 and XGBoost3 models, the quadrupole deformation values of the daughter nuclei were obtained from the WS4 and FRDM models, respectively. Additionally, in the XGBoost models, the physical terms of Eqs. (17) and (16) were used as inputs, and the residuals between the calculated and experimental α-decay half-lives served as the output.

The experimental data for 675 nuclei were extracted and divided into two sets: the training set (540 nuclei) and testing set (135 nuclei). The corresponding σ values calculated using the formulas and XGBoost1, XGBoost2, and XGBoost3 models are presented in Table 5. The σ values of the XGBoost1, XGBoost2, and XGBoost3 models show an obvious decrease compared with those of Eqs. (17) and (16) for the training and testing sets. For the entire set, the σ values of XGBoost1, XGBoost2, and XGBoost3 models reduced from 0.456 to 0.316, from 0.413 to 0.295, and from 0.415 to 0.302, respectively. This indicates that XGBoost models can further reduce the deviation between the calculated and experimental α-decay half-lives.

| inputs | σ (training set) | σ (testing set) | σ (entire set) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eq. (17) | - | 0.462 | 0.418 | 0.456 |

| XGBoost1 | (Qα, μ, Zc, Zd, l) | 0.310 | 0.346 | 0.316 |

| (Eq. (16), |

- | 0.427 | 0.345 | 0.413 |

| XGBoost2 | (Qα, μ, Zc, Zd, l, |

0.288 | 0.318 | 0.295 |

| (Eq. (16), |

- | 0.430 | 0.345 | 0.415 |

| XGBoost3 | (Qα, μ, Zc, Zd, l, |

0.301 | 0.308 | 0.302 |

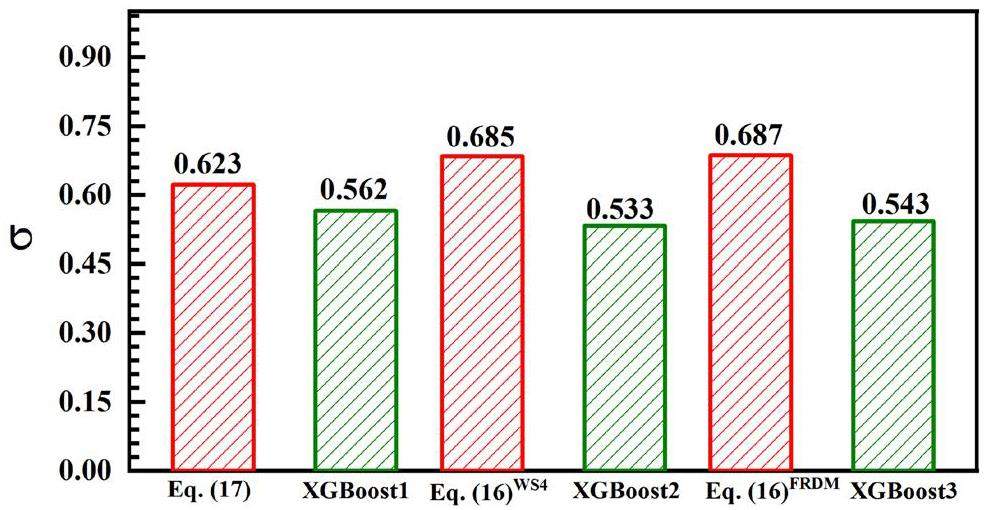

The deviations between the experimental data and results calculated using the empirical formula (blue circles) and XGBoost models (red stars) are illustrated in Fig. 3. As shown in Fig. 3, the majority of blue circles are scattered in the range of ± 1, suggesting larger deviations. By contrast, most red stars fall within the range of ± 0.5, indicating a closer alignment to the zero line. For nuclei near the neutron magic number N = 126 and sub-magic number N = 152, the deviations obtained by XGBoost models are smaller than those from the empirical formulas in Eqs. (17) and (16). To further quantify these differences, Fig. 4 shows the σ values in Eq. (17), Eq. (16), and the XGBoost models (XGBoost1, XGBoost2, and XGBoost3) for nuclei with N=125, 126, 127, 151, 152, and 153. The comparison shows that the σ values for the XGBoost models were reduced from 0.623 to 0.562, from 0.685 to 0.533, and from 0.687 to 0.543, respectively, indicating better consistency with the experimental data than with the empirical formulas. For these nuclei, the larger deviations of the empirical formulas can be attributed to their lack of consideration of shell effects. By contrast, the XGBoost models effectively capture missing physical effects, such as shell effects, by learning from the residuals between the empirical formulas and experimental data. Consequently, the XGBoost models further reduced the deviations for nuclei near the neutron magic number N = 126 and sub-magic number N = 152, providing more accurate predictions.

Predictions of α-decay half-lives of nuclei with Z = 117, 118, 119, and 120

Using the improved formula of Eq. (16), along with the XGBoost2 and XGBoost3 models, we predict the α-decay half-lives of SHN with Z = 117, 118, 119, and 120. In Table 6, the first column lists the α-decay, followed by the α-decay energy and quadrupole deformation of the daughter nuclei (columns 2-5), obtained from WS4 [67] and FRDM [68] mass models, respectively. The spin and parity values of the parent and daughter nuclei in the nuclear ground state were taken from Ref. [72]. Because of challenges in determining the spin and parity of doubly odd SHN, we assume that the minimum angular momentum l carried away by the α particle is zero. As shown in the eighth to last columns, the decimal logarithms of α-decay half-lives, calculated using the improved formula Eq. (16), are shown as

| α transition | l | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 279Ts→275Mc | 13.36 | 12.97 | 0.1792 | 0.198 | 2 | -5.734 | -5.391 | -4.904 | -4.306 |

| 280Ts→276Mc | 13.42 | 12.79 | 0.1825 | 0.198 | 0 | -4.876 | -5.454 | -4.097 | -4.388 |

| 281Ts→277Mc | 13.21 | 12.32 | 0.1822 | 0.198 | 2 | -5.440 | -5.619 | -3.633 | -3.525 |

| 282Ts→278Mc | 13.00 | 12.59 | 0.1803 | 0.032 | 0 | -4.039 | -4.495 | -4.376 | -4.512 |

| 283Ts→279Mc | 12.86 | 12.96 | -0.0141 | -0.011 | 2 | -5.150 | -4.800 | -5.402 | -4.909 |

| 284Ts→280Mc | 12.66 | 12.65 | -0.0239 | 0.021 | 0 | -5.023 | -5.008 | -4.548 | -4.447 |

| 285Ts→281Mc | 12.42 | 12.45 | 0.0404 | 0.032 | 2 | -4.123 | -4.319 | -4.240 | -4.287 |

| 286Ts→282Mc | 12.24 | 12.18 | -0.0573 | 0.064 | 0 | -4.385 | -4.455 | -3.357 | -3.201 |

| 287Ts→283Mc | 12.02 | 12.11 | -0.0719 | 0.064 | 2 | -3.403 | -3.743 | -3.441 | -3.446 |

| 288Ts→284Mc | 11.95 | 12.01 | 0.0618 | 0.064 | 0 | -2.743 | -3.121 | -2.976 | -3.170 |

| 289Ts→285Mc | 11.96 | 11.98 | 0.0707 | 0.064 | 2 | -3.076 | -2.888 | -3.152 | -2.743 |

| 290Ts→286Mc | 11.81 | 11.85 | 0.0676 | 0.075 | 0 | -2.364 | -2.774 | -2.567 | -2.752 |

| 291Ts→287Mc | 11.69 | 11.75 | -0.1016 | 0.064 | 2 | -2.647 | -2.806 | -2.630 | -2.549 |

| 292Ts→288Mc | 11.72 | 11.71 | 0.0654 | 0.064 | 0 | -2.178 | -2.141 | -2.282 | -2.021 |

| 293Ts→289Mc | 11.60 | 11.40 | 0.062 | 0.064 | 2 | -2.255 | -2.294 | -1.805 | -1.565 |

| 294Ts→290Mc | 11.35 | 11.29 | 0.0544 | 0.053 | 0 | -1.363 | -1.204 | -1.306 | -0.965 |

| 295Ts→291Mc | 11.27 | 11.55 | -0.0729 | -0.042 | 2 | -1.570 | -1.741 | -2.312 | -2.218 |

| 296Ts→292Mc | 11.48 | 11.64 | -0.062 | -0.042 | 0 | -2.678 | -2.359 | -2.511 | -2.007 |

| 297Ts→293Mc | 11.59 | 11.76 | -0.0555 | -0.021 | 2 | -2.363 | -2.621 | -2.786 | -2.712 |

| 298Ts→294Mc | 11.49 | 11.86 | -0.0392 | -0.021 | 0 | -2.523 | -2.811 | -2.956 | -3.001 |

| 299Ts→295Mc | 11.43 | 11.86 | -0.0334 | -0.021 | 2 | -1.951 | -1.686 | -3.021 | -2.512 |

| 300Ts→296Mc | 11.53 | 11.88 | -0.0319 | -0.011 | 0 | -2.536 | -2.401 | -2.964 | -2.679 |

| 301Ts→297Mc | 11.59 | 11.93 | -0.0276 | -0.011 | 2 | -2.323 | -1.957 | -3.166 | -2.612 |

| 302Ts→298Mc | 12.20 | 12.75 | -0.0154 | -0.011 | 0 | -3.959 | -4.070 | -4.891 | -4.898 |

| 303Ts→299Mc | 12.75 | 12.74 | -0.0087 | 0 | 2 | -4.918 | -4.509 | -4.918 | -4.417 |

| 304Ts→300Mc | 12.52 | 12.82 | -0.0145 | 0 | 0 | -4.642 | -5.088 | -4.988 | -5.366 |

| 305Ts→301Mc | 12.06 | 12.69 | -0.0214 | 0 | 2 | -3.413 | -3.229 | -4.813 | -4.475 |

| 306Ts→302Mc | 11.58 | 12.40 | -0.0277 | 0.011 | 0 | -2.629 | -2.864 | -4.046 | -4.195 |

| 307Ts→303Mc | 10.90 | 12.24 | -0.0466 | 0.011 | 1 | -0.785 | -0.473 | -4.026 | -3.480 |

| 308Ts→304Mc | 10.33 | 11.49 | -0.0575 | 0.021 | 0 | 0.375 | 0.186 | -1.908 | -1.883 |

| 309Ts→305Mc | 9.99 | 10.80 | -0.1822 | -0.011 | 3 | 2.346 | 2.788 | -0.048 | 0.579 |

| 310Ts→306Mc | 9.73 | 10.37 | -0.1855 | 0.044 | 0 | 0.974 | 1.273 | 1.115 | 1.415 |

| 311Ts→307Mc | 9.42 | 10.15 | -0.2 | 0.054 | 2 | 3.924 | 3.842 | 1.488 | 1.311 |

| 312Ts→308Mc | 9.05 | 9.78 | -0.2111 | 0.065 | 0 | 2.968 | 2.905 | 2.923 | 2.805 |

| 281Og→277Lv | 13.77 | 13.15 | 0.1787 | 0.186 | 5 | -5.274 | -5.254 | -4.129 | -3.825 |

| 282Og→278Lv | 13.49 | 13.12 | 0.1799 | 0 | 0 | -6.582 | -6.431 | -6.335 | -5.864 |

| 283Og→279Lv | 13.32 | 13.20 | 0.1792 | 0.032 | 7 | -3.262 | -3.395 | -3.171 | -3.062 |

| 284Og→280Lv | 13.21 | 13.56 | -0.0262 | 0 | 0 | -6.475 | -6.502 | -7.191 | -7.133 |

| 285Og→281Lv | 13.05 | 13.24 | 0.0363 | 0.032 | 0 | -5.399 | -5.362 | -5.788 | -5.692 |

| 286Og→282Lv | 12.89 | 13.05 | 0.0479 | 0.053 | 0 | -5.698 | -5.463 | -6.066 | -5.741 |

| 287Og→283Lv | 12.77 | 12.96 | 0.056 | 0.064 | 0 | -4.820 | -4.884 | -5.204 | -5.084 |

| 288Og→284Lv | 12.59 | 12.86 | -0.0765 | 0.064 | 0 | -5.257 | -5.026 | -5.662 | -5.215 |

| 289Og→285Lv | 12.56 | 12.76 | 0.0711 | 0.075 | 0 | -4.370 | -4.664 | -4.787 | -4.914 |

| 290Og→286Lv | 12.57 | 12.68 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 0 | -5.008 | -4.771 | -5.273 | -4.896 |

| 291Og→287Lv | 12.39 | 12.55 | 0.075 | 0.075 | 2 | -3.728 | -3.781 | -4.075 | -3.934 |

| 292Og→288Lv | 12.21 | 12.39 | 0.0735 | 0.075 | 0 | -4.248 | -4.392 | -4.671 | -4.676 |

| 293Og→289Lv | 12.21 | 12.34 | 0.0711 | 0.075 | 2 | -3.344 | -3.807 | -3.624 | -3.867 |

| 294Og→290Lv | 12.17 | 12.37 | 0.0687 | 0.064 | 0 | -4.163 | -3.963 | -4.649 | -4.223 |

| 295Og→291Lv | 11.88 | 11.92 | 0.0617 | 0.064 | 0 | -2.857 | -3.270 | -2.962 | -3.192 |

| 296Og→292Lv | 11.73 | 12.28 | 0.0532 | -0.073 | 0 | -3.176 | -3.102 | -4.703 | -4.420 |

| 297Og→293Lv | 12.08 | 12.38 | -0.0789 | -0.063 | 0 | -3.385 | -3.801 | -4.055 | -4.241 |

| 298Og→294Lv | 12.16 | 12.49 | -0.0651 | -0.042 | 0 | -4.279 | -3.902 | -5.112 | -4.549 |

| 299Og→295Lv | 12.02 | 12.51 | -0.0507 | -0.021 | 2 | -2.968 | -2.939 | -4.044 | -3.709 |

| 300Og→296Lv | 11.93 | 12.51 | -0.0441 | -0.011 | 0 | -3.733 | -3.926 | -5.093 | -5.066 |

| 301Og→297Lv | 12.00 | 12.56 | -0.0396 | 0 | 2 | -2.903 | -3.012 | -4.138 | -4.000 |

| 302Og→298Lv | 12.02 | 12.62 | -0.0336 | 0 | 0 | -3.923 | -3.913 | -5.305 | -5.175 |

| 303Og→299Lv | 12.58 | 13.38 | -0.0197 | 0 | 4 | -3.566 | -3.666 | -5.179 | -5.227 |

| 304Og→300Lv | 13.10 | 13.39 | -0.0136 | 0 | 0 | -6.232 | -5.888 | -6.863 | -6.450 |

| 305Og→301Lv | 12.89 | 13.45 | -0.0188 | 0 | 2 | -4.837 | -4.617 | -5.950 | -5.621 |

| 306Og→302Lv | 12.46 | 13.35 | -0.0264 | 0 | 0 | -4.906 | -5.248 | -6.785 | -7.042 |

| 307Og→303Lv | 11.90 | 12.57 | -0.0397 | 0.011 | 2 | -2.690 | -2.802 | -4.152 | -4.016 |

| 308Og→304Lv | 11.18 | 12.10 | -0.0484 | 0 | 0 | -1.893 | -1.810 | -4.168 | -3.900 |

| 309Og→305Lv | 10.70 | 11.07 | -0.0584 | 0.022 | 2 | 0.359 | 0.422 | -0.626 | -0.288 |

| 310Og→306Lv | 10.41 | 10.74 | -0.1812 | 0.044 | 0 | 0.268 | 0.534 | -0.795 | -0.415 |

| 311Og→307Lv | 10.08 | 9.98 | -0.2049 | -0.042 | 2 | 2.177 | 2.561 | 2.441 | 2.917 |

| 312Og→308Lv | 9.74 | 10.05 | -0.207 | 0.055 | 0 | 2.406 | 1.999 | 1.131 | 0.706 |

| 313Og→309Lv | 8.63 | 9.72 | -0.2135 | 0.066 | 0 | 6.890 | 7.432 | 2.925 | 3.570 |

| 285119→281Ts | 13.60 | 14.06 | 0.0304 | 0 | 2 | -5.998 | -5.813 | -6.979 | -6.712 |

| 286119→282Ts | 13.42 | 13.75 | 0.0401 | 0.043 | 0 | -5.494 | -5.914 | -6.112 | -6.442 |

| 287119→283Ts | 13.26 | 13.37 | 0.0524 | 0.064 | 2 | -5.288 | -5.535 | -5.497 | -5.466 |

| 288119→284Ts | 13.20 | 13.57 | -0.0751 | 0.075 | 0 | -6.040 | -5.900 | -5.620 | -5.264 |

| 289119→285Ts | 13.13 | 13.47 | -0.0845 | 0.075 | 2 | -5.310 | -5.027 | -5.656 | -5.025 |

| 290119→286Ts | 13.04 | 13.31 | 0.0721 | 0.075 | 0 | -4.465 | -4.804 | -5.117 | -5.316 |

| 291119→287Ts | 13.02 | 13.24 | 0.0773 | 0.075 | 2 | -4.773 | -4.409 | -5.215 | -4.657 |

| 292119→288Ts | 12.87 | 13.08 | 0.0776 | 0.086 | 0 | -4.073 | -3.611 | -4.610 | -4.013 |

| 293119→289Ts | 12.69 | 12.92 | 0.0746 | 0.075 | 2 | -4.099 | -3.580 | -4.581 | -3.869 |

| 294119→290Ts | 12.70 | 12.85 | 0.0739 | 0.075 | 0 | -3.731 | -3.474 | -4.187 | -3.790 |

| 295119→291Ts | 12.73 | 12.94 | 0.0732 | 0.075 | 2 | -4.191 | -4.541 | -4.620 | -4.776 |

| 296119→292Ts | 12.45 | 12.98 | 0.0733 | 0.075 | 0 | -3.191 | -3.550 | -4.452 | -4.671 |

| 297119→293Ts | 12.40 | 12.90 | -0.0856 | -0.073 | 2 | -3.716 | -3.561 | -4.890 | -4.418 |

| 298119→294Ts | 12.69 | 13.09 | -0.0806 | -0.073 | 0 | -5.037 | -5.387 | -5.335 | -5.430 |

| 299119→295Ts | 12.74 | 13.08 | -0.0721 | -0.052 | 2 | -4.453 | -4.813 | -5.218 | -5.312 |

| 300119→296Ts | 12.55 | 13.04 | -0.0601 | -0.032 | 0 | -4.559 | -4.939 | -5.048 | -5.185 |

| 301119→297Ts | 12.40 | 13.08 | -0.0494 | -0.032 | 0 | -3.977 | -4.229 | -5.474 | -5.483 |

| 302119→298Ts | 12.40 | 13.05 | -0.0431 | 0 | 0 | -4.096 | -4.639 | -4.925 | -5.282 |

| 303119→299Ts | 12.39 | 13.11 | -0.0355 | 0 | 2 | -3.632 | -3.256 | -5.147 | -4.523 |

| 304119→300Ts | 12.91 | 13.86 | -0.02 | 0 | 0 | -4.972 | -4.737 | -6.519 | -6.215 |

| 305119→301Ts | 13.40 | 13.86 | 0.0147 | 0 | 2 | -5.650 | -5.384 | -6.607 | -6.250 |

| 306119→302Ts | 13.18 | 13.92 | -0.0198 | 0 | 0 | -5.525 | -5.464 | -6.631 | -6.501 |

| 307119→303Ts | 12.76 | 13.39 | -0.0287 | 0 | 0 | -4.721 | -5.152 | -6.012 | -6.358 |

| 308119→304Ts | 12.04 | 12.17 | -0.0396 | 0.011 | 0 | -3.247 | -2.919 | -2.970 | -2.456 |

| 309119→305Ts | 11.35 | 11.70 | -0.0508 | 0 | 3 | -0.836 | -1.338 | -1.722 | -2.005 |

| 310119→306Ts | 10.86 | 10.67 | -0.0616 | -0.032 | 0 | -0.517 | -0.651 | 0.666 | 0.752 |

| 311119→307Ts | 10.76 | 10.32 | -0.1895 | 0 | 0 | 0.098 | 0.171 | 1.315 | 1.434 |

| 312119→308Ts | 10.56 | 9.90 | -0.1936 | -0.397 | 0 | -0.908 | -0.512 | 1.916 | 2.463 |

| 313119→309Ts | 9.37 | 10.06 | -0.2055 | 0.066 | 2 | 4.825 | 5.333 | 2.398 | 2.812 |

| 314119→310Ts | 8.97 | 9.55 | -0.2136 | -0.407 | 0 | 3.896 | 4.091 | 3.085 | 3.233 |

| 315119→311Ts | 8.65 | 9.36 | -0.2137 | -0.406 | 1 | 7.318 | 7.005 | 4.635 | 4.535 |

| 316119→312Ts | 8.67 | 9.20 | -0.2369 | -0.406 | 0 | 7.050 | 6.877 | 5.404 | 5.308 |

| 317119→313Ts | 9.20 | 9.06 | -0.4273 | -0.416 | 3 | 5.859 | 5.518 | 6.462 | 6.180 |

| 287120→283Og | 13.84 | 13.96 | -0.0531 | 0.043 | 4 | -5.595 | -5.706 | -5.729 | -5.590 |

| 288120→284Og | 13.71 | 13.85 | -0.0663 | 0.064 | 0 | -7.039 | -7.317 | -7.068 | -7.147 |

| 289120→285Og | 13.69 | 13.75 | -0.0797 | 0.075 | 0 | -6.253 | -6.497 | -6.213 | -6.227 |

| 290120→286Og | 13.68 | 13.75 | -0.0872 | 0.075 | 0 | -7.028 | -6.996 | -6.852 | -6.641 |

| 291120→287Og | 13.48 | 13.87 | -0.096 | 0.075 | 2 | -5.586 | -6.056 | -6.164 | -6.394 |

| 292120→288Og | 13.44 | 13.78 | 0.0788 | 0.086 | 0 | -6.222 | -6.226 | -6.874 | -6.743 |

| 293120→289Og | 13.37 | 13.65 | 0.0786 | 0.086 | 2 | -5.206 | -4.958 | -5.741 | -5.304 |

| 294120→290Og | 13.22 | 13.49 | -0.1098 | 0.086 | 0 | -6.132 | -5.759 | -6.338 | -5.857 |

| 295120→291Og | 13.25 | 13.46 | 0.0762 | 0.075 | 2 | -4.954 | -4.862 | -5.386 | -5.101 |

| 296120→292Og | 13.32 | 13.59 | 0.0752 | 0.075 | 0 | -5.989 | -6.199 | -6.554 | -6.624 |

| 297120→293Og | 13.12 | 13.65 | 0.0751 | 0.075 | 0 | -4.970 | -5.153 | -6.021 | -6.065 |

| 298120→294Og | 12.98 | 13.24 | -0.0863 | 0.064 | 0 | -5.595 | -5.896 | -5.915 | -6.019 |

| 299120→295Og | 13.23 | 13.73 | -0.0849 | -0.084 | 0 | -5.343 | -5.652 | -6.325 | -6.379 |

| 300120→296Og | 13.29 | 13.70 | -0.075 | -0.063 | 0 | -6.233 | -6.400 | -7.155 | -7.105 |

| 301120→297Og | 13.04 | 13.62 | -0.065 | -0.042 | 2 | -4.654 | -4.944 | -5.800 | -5.842 |

| 302120→298Og | 12.87 | 13.55 | 0.0382 | -0.032 | 0 | -5.155 | -5.582 | -6.773 | -7.067 |

| 303120→299Og | 12.79 | 13.51 | -0.0448 | -0.011 | 2 | -4.104 | -3.690 | -5.556 | -4.860 |

| 304120→300Og | 12.74 | 13.55 | -0.0355 | 0 | 0 | -4.999 | -5.520 | -6.684 | -7.019 |

| 305120→301Og | 13.26 | 14.26 | -0.0214 | 0 | 2 | -5.060 | -4.988 | -6.954 | -6.729 |

| 306120→302Og | 13.77 | 14.28 | 0.0139 | 0 | 0 | -6.971 | -6.621 | -8.042 | -7.641 |

| 307120→303Og | 13.50 | 13.62 | 0.0191 | 0 | 4 | -4.873 | -4.879 | -5.125 | -5.078 |

| 308120→304Og | 12.95 | 12.96 | -0.0297 | 0 | 0 | -5.426 | -5.655 | -5.503 | -5.616 |

| 309120→305Og | 12.14 | 11.77 | -0.0416 | -0.021 | 0 | -2.932 | -3.279 | -2.053 | -2.157 |

| 310120→306Og | 11.48 | 11.29 | -0.0527 | 0 | 0 | -2.063 | -1.779 | -1.673 | -1.204 |

| 311120→307Og | 11.18 | 10.76 | -0.1882 | -0.397 | 2 | -0.300 | -0.385 | 0.877 | 1.003 |

| 312120→308Og | 11.20 | 10.71 | -0.1933 | -0.397 | 0 | -1.344 | -1.316 | -0.251 | -0.074 |

| 313120→309Og | 11.01 | 10.50 | -0.194 | -0.407 | 2 | 0.160 | 0.431 | 1.648 | 2.098 |

| 314120→310Og | 10.74 | 10.33 | -0.2019 | -0.407 | 0 | -0.043 | 0.109 | 0.961 | 1.208 |

| 315120→311Og | 9.41 | 10.16 | -0.2323 | -0.407 | 0 | 4.792 | 5.516 | 2.425 | 2.993 |

| 316120→312Og | 9.17 | 9.94 | 0.3893 | -0.416 | 0 | 4.035 | 3.735 | 2.277 | 2.114 |

| 317120→313Og | 9.91 | 9.83 | -0.4157 | -0.416 | 3 | 3.757 | 4.187 | 4.041 | 4.669 |

| 318120→314Og | 9.91 | 9.66 | -0.425 | -0.416 | 0 | 2.772 | 2.722 | 3.266 | 3.408 |

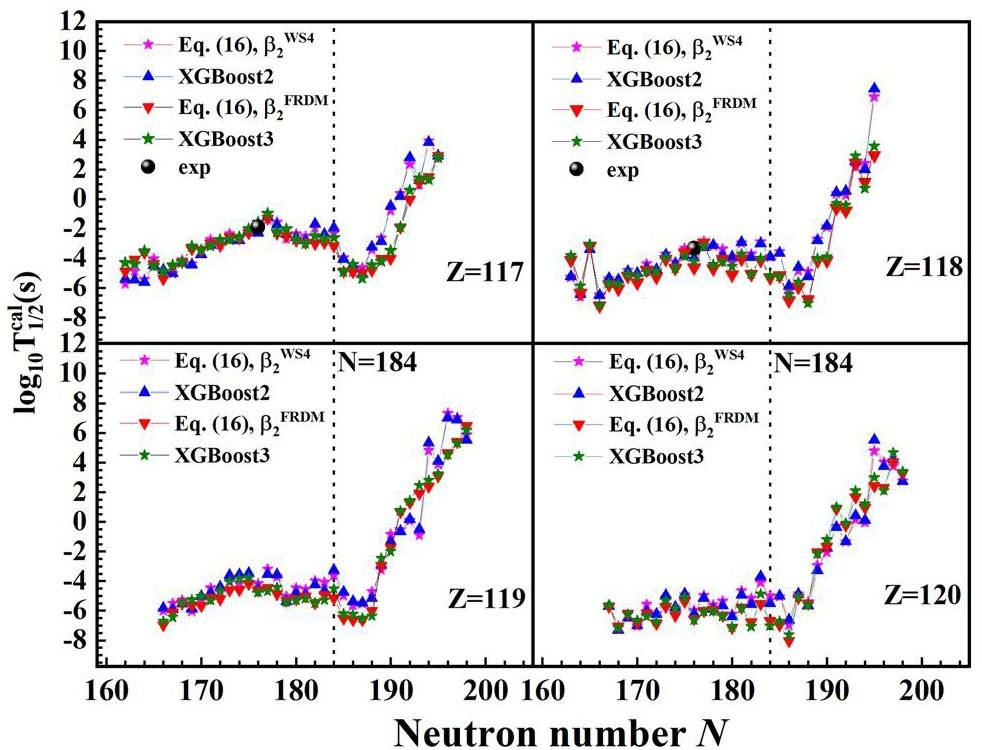

The calculated α-decay half-lives of the nuclei with Z = 117, 118, 119, and 120 are plotted in Fig. 5, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, the calculated α-decay half-lives for 293Ts, obtained using the improved formula (

Summary

In summary, this study investigated the impact of deformation effects on α-decay half-lives using an improved formula within the WKB framework. By incorporating the quadrupole deformation of the daughter nucleus into the Coulomb potential, the improved formula provides a refined description of the α-decay half-lives of nuclei with

Wave mechanics and radioactive disintegration

. Nature 122, 1476-4687 (1928). https://doi.org/10.1038/122439a0Zur quantentheorie des atomkernes

. Z. Phys. 51, 204-212 (1928). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01343196Clustering in nuclei: progress and perspectives

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 216 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01588-xPossibilities for the synthesis of superheavy element Z = 121 in fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 95 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01452-yProduction of neutron-rich actinide isotopes in isobaric collisions via multinucleon transfer reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 160 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01314-zLVII. the ranges of the α particles from various radioactive substances and a relation between range and period of transformation

. Philos. Mag. 22, 613-621 (1911). https://doi.org/10.1080/14786441008637156Alpha emission and spontaneous fission through quasi-molecular shapes

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 26, 1149-1170 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/26/8/305Analytic expressions for alpha-decay half-lives and potential barriers

. Nucl. Phys. A 848, 279-291 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.09.009Nuclear systematics of the heavy elements-II lifetimes for alpha, beta and spontaneous fission decay

. J. Ino. Nucl. Chem. 28, 741-761 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1902(66)80412-8Unified formula of half-lives forα decay and cluster radioactivity

. Phys. Rev. C 78,New geiger-nuttall law for α decay of heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Universal decay law in charged-particle emission and exotic cluster radioactivity

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103,Improved empirical formula forα-decay half-lives

. Phys. Rev. C 101,α-decay half-lives: Empirical relations

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Alpha decay calculations with a new formula

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 44,New empirical formula forα-decay calculations

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 27,Nuclear isospin asymmetry inα decay of heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Alpha-decay for heavy nuclei in the ground and isomeric states

. Nucl. Phys. A 832, 198-208 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2009.10.082Systematic calculations ofα-decay half-lives with an improved empirical formula

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 42,Influence of nuclear isospin and angular momentum onα-decay half-lives

. Nucl. Phys. A 983, 310-320 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2018.10.091α-decay systematics for superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Unfavoredα decay from ground state to ground state in the range 53 ≤ Z ≤91

. Phys. Rev. C 85,The nuclear deformation and the preformation factor in the α-decay of heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 934, 110-120 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2014.12.001Cluster radioactivity within the collective fragmentation approach using different mass tables and related deformations

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 35 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00023-0Calculations of α-decay half-lives for heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Global calculation of alpha-decay half-lives with a deformed density-dependent cluster model

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Enhanced α decays to negative-parity states in even-even nuclei with octupole deformation

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Density-dependent parametrizations in B3Y-Fetal NN interaction: Application to alpha decay

. Int. J. Theo. Phys 54, 74 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13538-024-01453-7Systematic study of αdecay half-lives for even–even nuclei within a deformed two-potential approach

. Commun. Theor. Phys. 74,Properties of Z = 114 super-heavy nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 55 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00899-7Theoretical calculations of the nuclear deformation effects on α-decay half-lives for heavy and super-heavy nuclei

. J. Phys. G 48,Study of alpha-decay half-lives with deformed, oriented daughter nuclei

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 24,Effect of nuclear deformation on the potential barrier and alpha-decay half-lives of superheavy nuclei

. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 28,Colloquium: Machine learning in nuclear physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94,Machine learning in nuclear physics at low and intermediate energies

. Sci. China. Phys. Mech. 66,Random forest-based prediction of decay modes and half-lives of superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01354-5An artificial neural network application on nuclear charge radii

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 40,A study on ground-state energies of nuclei by using neural networks

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 63, 172-175 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2013.07.039Nuclear charge radii: density functional theory meets bayesian neural networks

. J. Phys. G 43,Bayesian approach to model-based extrapolation of nuclear observables

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Nuclear mass predictions based on bayesian neural network approach with pairing and shell effects

. Phys. Lett. B 778, 48-53 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.01.002Predictions of nuclear β-decay half-lives with machine learning and their impact on r-process nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Modified empirical formulas and machine learning for α-decay systematics

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 48,Nuclear mass predictions with machine learning reaching the accuracy required by r-process studies

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Study on nuclear α-decay energy by an artificial neural network with pairing and shell effects

. Symmetry 5, 1006 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/sym14051006Deep learning approach to nuclear masses and α-decay half-lives

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Nuclear masses learned from a probabilistic neural network

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Novel Bayesian neural network based approach for nuclear charge radii

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Reliable calculations of nuclear binding energies by the gaussian process of machine learning

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 105 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01463-9Target dependence of isotopic cross sections in the spallation reactions 238U + p and 9Be at 1 AGeV *

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Application of kernel ridge regression in predicting neutron-capture reaction cross-sections

. Commun. Theor. Phys. 74,Application of machine learning in the determination of impact parameter in the 132Sn+124Sn system

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Determining impact parameters of heavy-ion collisions at low-intermediate incident energies using deep learning with convolutional neural networks

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Bayesian analysis on interactions of exotic nuclear systems

. Phys. Lett. B 807,Determining the temperature in heavy-ion collisions with multiplicity distribution

. Phys. Lett. B 814,The QCD EoS of dense nuclear matter from Bayesian analysis of heavy ion collision data

. arXiv e-prints arXiv:2211.11670 (2022)., https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.11670Bayesian inference of the symmetry energy of superdense neutron-rich matter from future radius measurements of massive neutron stars

. Astrophys. J 899, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aba271Linear regression and machine learning for nuclear forensics of spent fuel from six types of nuclear reactors

. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19,Reconstruction of the event vertex in the PandaX-III experiment with convolution neural network

. J. High. Engergy. Phys. 2023, 200 (2023). arXiv:2211.14992, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP05(2023)200α-decay half-lives, α-capture, and α-nucleus potential

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 95, 815-835 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2009.06.003Penetration factor in deformed potentials: Application to αdecay with deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Interaction barriers, nuclear shapes and the optimum choice of a compound nucleus reaction for producing super-heavy elements

. Phys. Lett. B 67, 257-261 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(77)90364-1Proximity potential for deformed, oriented collisions and its application to 238U + 238U

. Phys. Rev. C 31, 1179 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.31.1179Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. KDD ’16

, (The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear physics properties *

. Chin. Phys. C 45,The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (ii). tables, graphs and references*

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Surface diffuseness correction in global mass formula

. Phys. Lett. B 734, 215-219 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2014.05.049Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations: Frdm(2012)

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 109-110, 1-204 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.1995.1002Spontaneous fission half-lives of heavy and superheavy nuclei within a generalized liquid drop model

. Nucl. Phys. A 906, 1-13 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2013.03.002Superheavy nuclei in the relativistic mean-field theory

. Nucl. Phys. A 608, 202-226 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(96)00273-4Spontaneous-fission half-lives of deformed superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 1871-1880 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.1871The authors declare that they have no competing interests.