Introduction

The neutron total cross section is a critical foundation of neutron-induced reaction cross section data, which supports nuclear data evaluation [1], nuclear energy development utilization [2], and nuclear physics [3]. In the low-energy range, precise neutron total cross section data are equally important for the advancement of neutron Bragg-edge transmission imaging and charge-radius determination [4]. Achieving high-quality neutron total cross section measurements depends critically on the availability of a high-performance neutron source and advanced neutron cross section spectrometers. The back-streaming white neutron beamline (Back-n [5]) at the China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS), which covers an energy range from approximately 0.3 eV to 300 MeV, is a facility that offers an excellent platform for conducting high-level neutron total cross section measurements [6, 7]. The neutron total cross section spectrometer (NTOX) installed on the Back-n comprises a multi-layer fission ionization chamber (FIXM) in which four 235U fission cells and four 238U fission cells are used for neutron detection using the time-of-flight (TOF) technique [8, 9]. However, the fission cross sections of 235U and 238U exhibit strong resonance effects in the eV–keV energy range, which can significantly decrease the accuracy and increase the experimental uncertainty in neutron total cross section measurements for nuclides with resonance peaks in the same energy region.

In recent decades, neutron total cross section measurements at large white neutron sources have primarily employed gas detectors (such as fission chambers) and scintillator detectors (primarily lithium glass and lithium-doped inorganic scintillators). Among these, scintillation detectors have been widely utilized in most spectrometers and have demonstrated significant advantages in neutron total cross section measurements owing to their high detection efficiency, excellent time resolution, and high sensitivity to neutrons across specific energy ranges. At the Oak Ridge Electron Linear Accelerator (ORELA) in the United States, Li-glass and NE-110 scintillators have been used for neutron total cross section measurements in the eV–keV energy range and for energies above 20 keV, respectively, [10]. Owing to its sensitivity to thermal neutrons, the 6LiF/ZnS (Ag) scintillator has been employed for neutron total cross section measurements in the Photoneutron Source (PNS) at the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics (SINAP) using the TOF technique with a 6.2 m flight path [11].

For neutron energies below 1 MeV, 6Li-enriched scintillators are typically employed [12, 13]. At higher energy levels, plastic and liquid scintillators, such as NE213 and EJ-301, are typically used [14, 15]. For γ-ray-sensitive scintillators, pulse shape discrimination (PSD) can be utilized to separate γ-ray events and minimize their contribution to the background. Neutron/γ dual-mode detection scintillation crystals have emerged as significant research topics and applications over the past 20 years [16]. In particular, 6Li possesses a thermal neutron reaction cross section of 940 barns with a smooth cross section in the low-energy region and without the severe resonance effects observed in 235U and 238U [17]. Compared to common 6Li-enriched neutron scintillators, such as Li-glass, LiI:Eu, and LiF/ZnS:Ag, 6Li-enriched scintillators belonging to the elpasolite crystal family offer several advantages, including high light output, fast decay time, excellent energy resolution, and superior neutron/γ discrimination [18]. These characteristics enable dual-mode detection and discrimination of neutrons and γrays. The Cs2LiLaBr6 (CLLB) scintillator has recently attracted considerable attention. Therefore, considering the strong γ-ray interference on the Back-n beamline at the CSNS, a fast scintillator-based neutron total cross section (FAST) spectrometer was designed [19]. The Geant4 program was utilized for the physical design and detailed simulations of the high-6Li-enriched inorganic scintillator CLLB for neutron/γ dual-mode detection in the Back-n environment.

A side-readout square CLLB detector was recommended, and a prototype was constructed. The energy linearity, neutron/γ discrimination capability, and neutron detection efficiency of the prototype were evaluated using various standard gamma sources, the Pu-Be isotope neutron moderation source, and a DT neutron generator, respectively. All tests provided a preliminary validation of the reliability of the detector design.

In this study, the performance of the prototype was evaluated using wide-energy pulsed neutrons on the Back-n beamline at the CSNS. The beam test employed the TOF technique to determine the neutron energy and transmission method. The neutron/γ discrimination capability of the prototype was evaluated on the complex background of Back-n. The detector performance was assessed in terms of both detection efficiency and neutron total cross section measurements, and the results were compared with the data obtained by the NTOX spectrometer. The capability of the prototype for fast neutron detection was also examined.

Experiment

The square CLLB-based neutron spectrometer

Based on the physical design of the FAST spectrometer [19], a square CLLB scintillator with dimensions of 50.8 mm × 50.8 mm × 6 mm was constructed as a prototype. With a density of 4.2 g/cm3, the CLLB exhibits a high light yield of 40,000 photons/MeV and fast response [20]. It releases up to 4.78 MeV via the

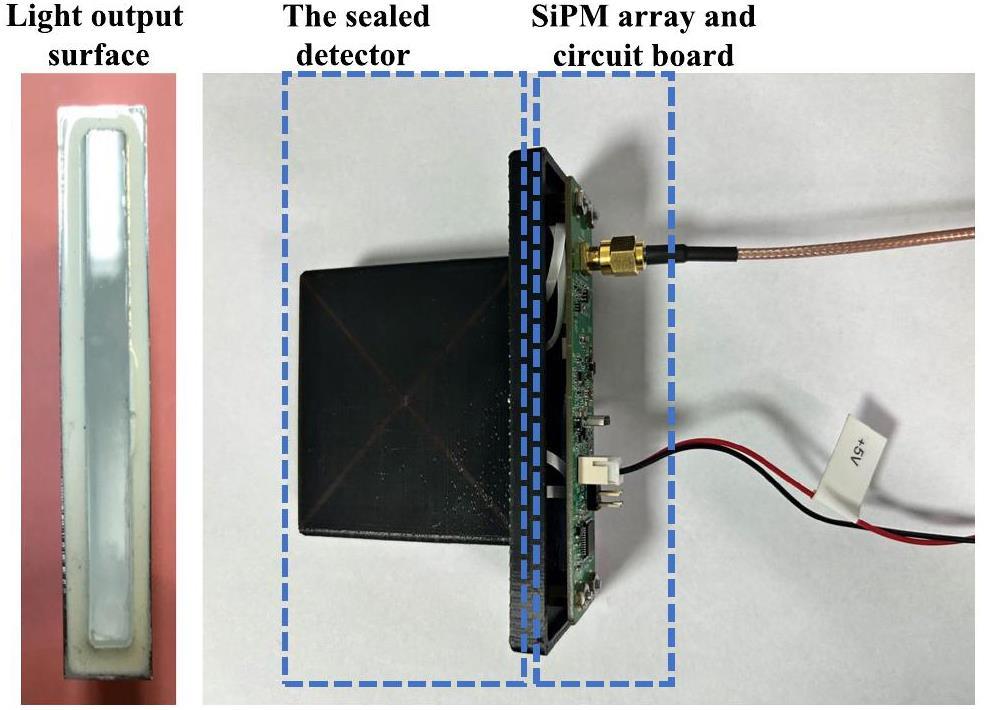

To protect the readout system from high-flux, high-energy neutrons and γ-ray irradiation, a side-readout method for the scintillator was employed, and a 1 × 8 array of 6 mm × 6 mm SiPM was assembled to match the shape and requirements of the light-output surface. The SiPM unit was an MPPC-S14160 provided by Hamamatsu, exhibiting a light response range of 270–900 nm and peak sensitivity at 450 nm. Additionally, the hygroscopic nature of the CLLB crystal leads to its degradation under ambient conditions when left unprotected, necessitating its packaging in aluminum shells with quartz windows affixed using a vacuum-grade epoxy. The structure of the prototype is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Neutron beam test on the Back-n Beamline

A beam test was conducted to evaluate the applicability of the prototype on the Back-n beamline. Neutrons were generated via spallation reactions induced by 1.6 GeV protons bombarding a target primarily composed of tungsten and tantalum at the CSNS [22, 23]. The prototype was tested by backstreaming neutrons along the path of an incident proton beam. During the test, the accelerator was operated at a proton beam power of approximately 140 kW. The incident proton pulse was configured in the double-bunch mode, with each bunch approximately 70 ns wide (rms) and separated by a 410 ns interval. It was accelerated via a Linac and synchrotron operating at a pulse repetition rate of 25 Hz.

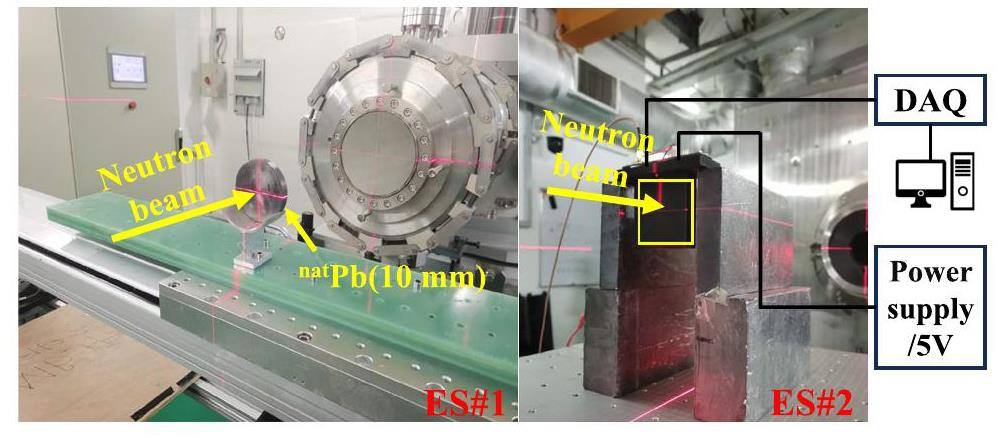

Considering the strong γ-flash and to reduce the background on the Back-n, two neutron shutter apertures with mechanical diameters of Φ3mm and Φ12mm were selected for this test. The dimensions of the incident surface of the scintillator were sufficient to cover the two mechanical sizes fully. To reduce the γ-ray radiation in the configuration with a Φ12mm mechanical aperture, a lead shield with a thickness of 60 mm was positioned in front of the neutron beam. To further test the prototype’s capability to measure the neutron total cross section, the neutron total cross section of natPb was measured using the transmission method [24], which is the same approach employed by the NTOX for measuring the neutron total cross section. There are two experimental stations along the Back-n beamline: end-station 1 (ES#1) and end-station 2 (ES#2), which have flight paths of approximately 55 and 76 m, respectively [5]. A high-purity natPb sample was placed at ES#1, and the prototype was set up at ES#2 to provide the neutron flight termination signal. The distance between the detector and sample was approximately 22 m, and there was a shielding door between the two experimental halls to minimize the impact of scattering neutrons from ES#1. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The prototype was connected to a 5 V low-voltage power supply, and the anode signal was directly fed into the data acquisition system (DAQ [25]), which employs a full-waveform digitization system developed for the Back-n facility. The DAQ features a high sampling rate of 1 GS/s, digital resolution of 12 bits, and a substantial sampling depth of 37 ms. It is capable of recording all signals within each pulse cycle with almost no system dead time, facilitating real-time waveform monitoring and data storage in binary format.

Analyses and Results

Raw data were processed offline using the ROOT framework [26]. This includes neutron/γ discrimination, determination of the neutron TOF, calibration of the precise neutron flight path, normalization of the data, and determination of the transmission spectrum of the sample to obtain the neutron total cross section.

Neutron/γ discrimination

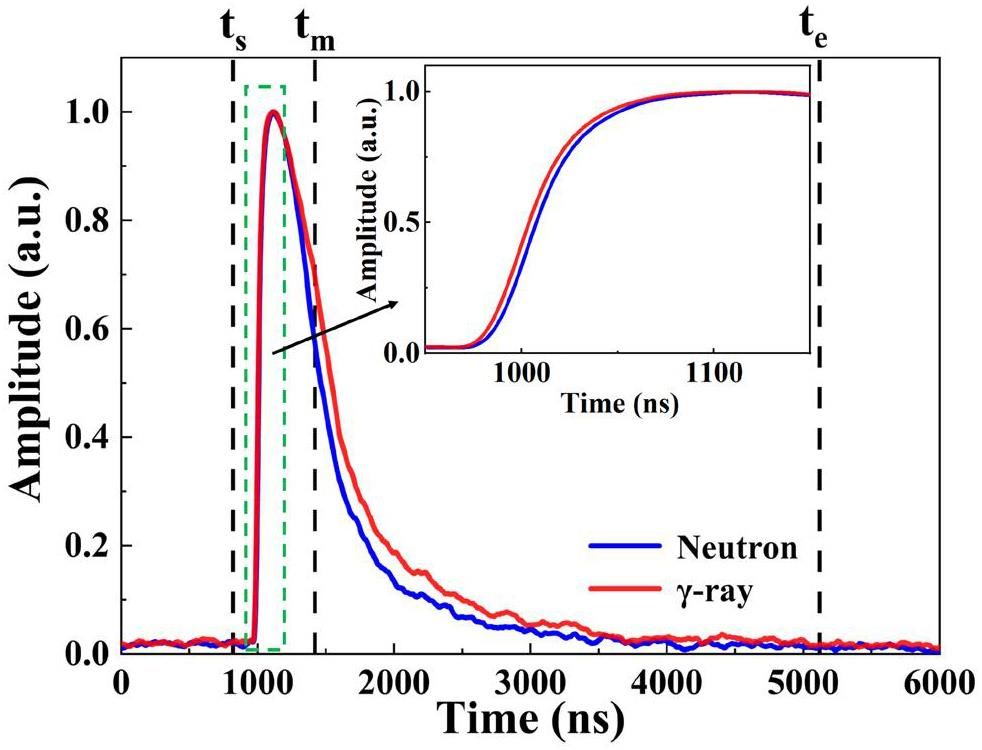

The dual-mode CLLB scintillator exhibited high sensitivity to γ-rays. Therefore, the exclusion of γ-ray signals from the detector output is essential for enhancing the accuracy of the neutron energy spectrum measurements. Figure 3 shows the typical signal waveforms of the neutrons and γ-rays detected by the CLLB scintillator with the normalized signal amplitude. A significant temporal distinction is observed between the two types of signals, with the neutron-excited pulses being faster than γ-ray-excited pulses in both the rise and decay tails of the CLLB scintillator. This temporal discrepancy allows using the charge comparison (CC) method to analyze the charge integration in every pulse, thereby enabling effective neutron/γ discrimination [27, 28]. The temporal difference is characterized using the CC Method, as shown in Eq. 1.

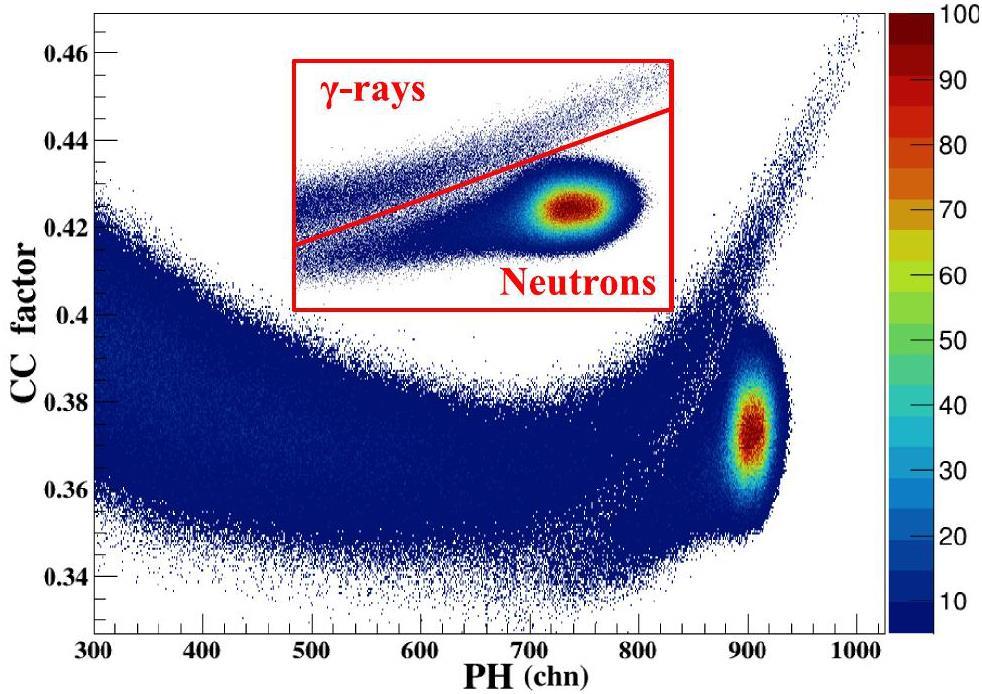

Figure 4 shows a typical pulse height–pulse shape discrimination (PH-PSD) 2D histogram for the prototype, illustrating the neutron/γ discrimination results. The neutrons and γ-rays were distributed in a manner that was not parallel to the coordinate axes in the PSD 2D histogram. Consequently, a specific discrimination line was used to calculate the value of the events relative to the discrimination line within the same energy interval. The discrimination line is given in Eq. 2.

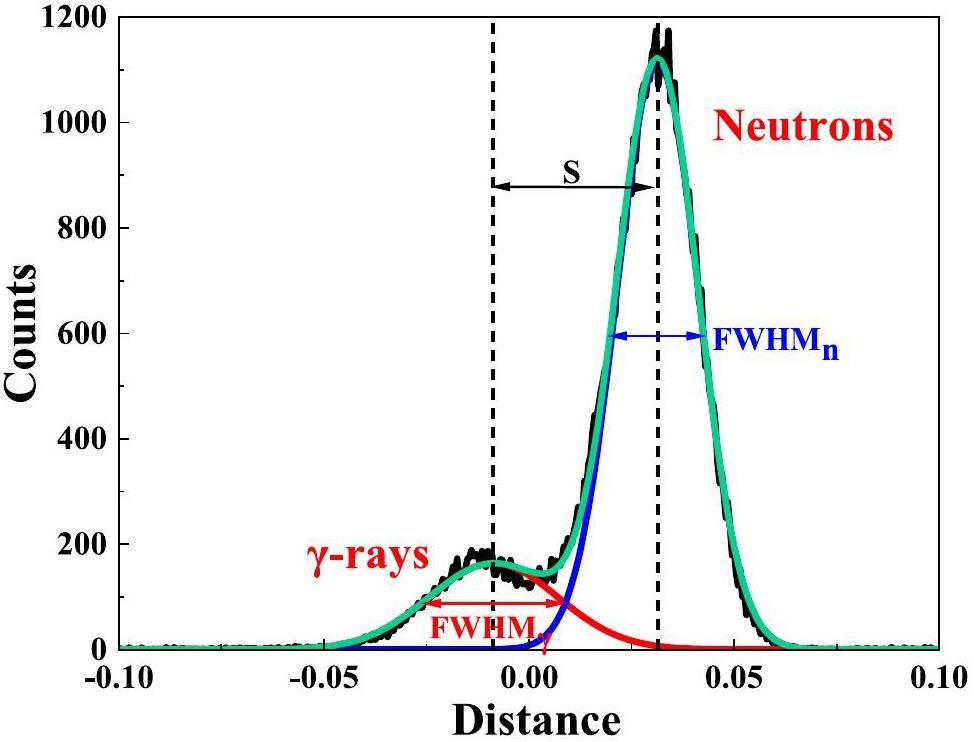

By calculating the distance of each event from the discrimination line, the events can be classified as either neutrons or γ-rays. Events with a distance greater than 0 were considered neutron events, whereas those with a distance less than 0 were considered γ-rays. Subsequently, a one-dimensional PSD histogram was obtained, with the vertical axis representing event counts and the horizontal axis representing the distance of the events from the discrimination line, as shown in Fig. 5. The figure of merit (FoM) factor was used to evaluate the effectiveness of neutron/γ discrimination [29]. The FoM factor is defined by Eq. 3.

The prototype achieved an FoM factor of 0.77 for neutron/γ discrimination using the CC method. The results indicate that the prototype demonstrates fair neutron/γ discrimination performance on the Back-n beamline.

Neutron detection efficiency

The detection efficiency of FIXM is relatively limited, requiring a substantial amount of time for neutron total cross section measurements. However, 6Li-enriched scintillators are generally recognized for their high detection efficiency. In the FAST spectrometer prototype, the abundance of 6Li in CLLB exceeded 95%, as determined through preliminary Monte Carlo simulations. Consequently, the detection efficiency of the developed prototype was analyzed and compared with that of FIXM across individual measurement units.

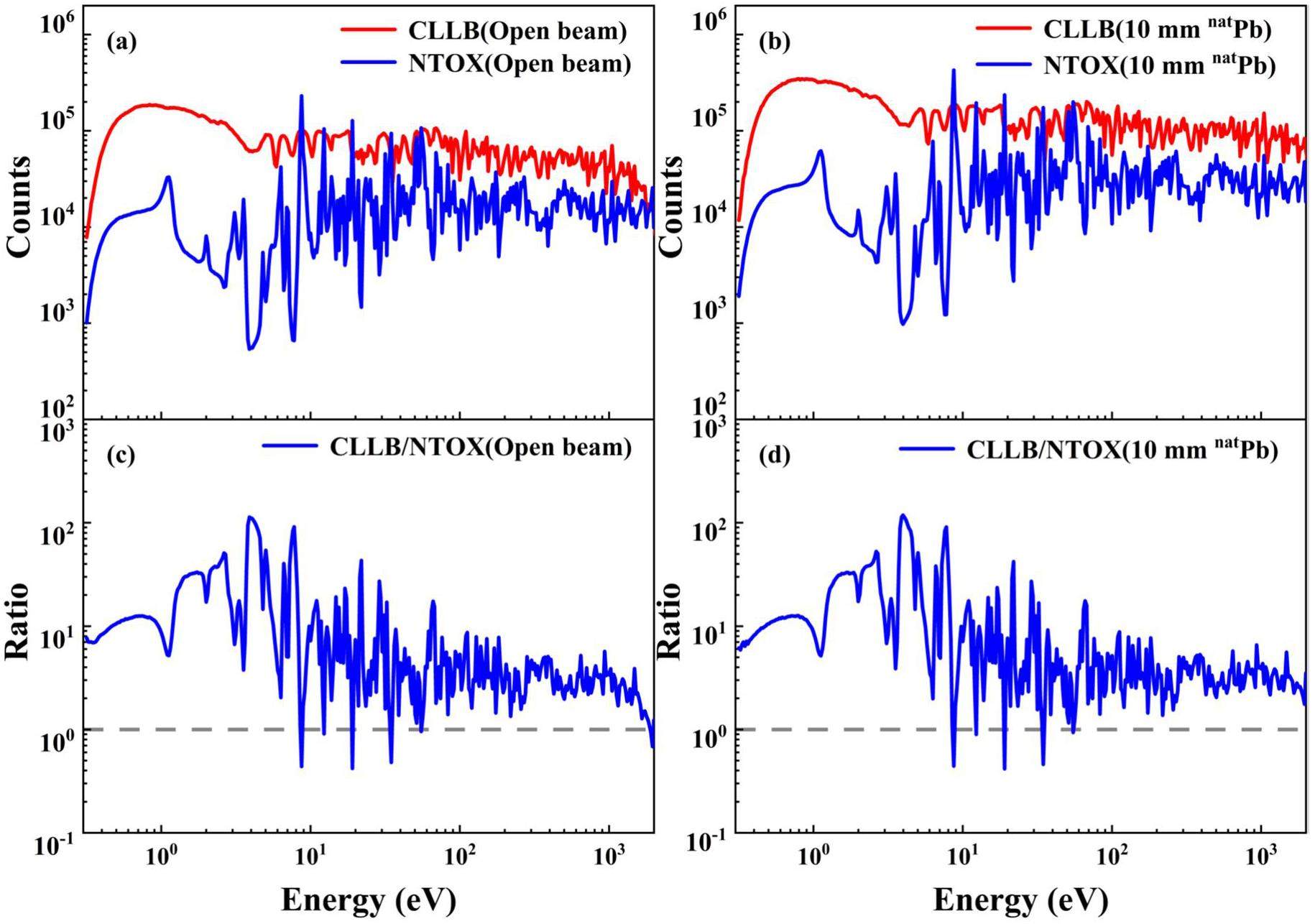

Xue et al. [30] obtained high-quality neutron total cross section data for natPb in the energy range of 0.3 eV to 20 MeV using the NTOX. In their experiment, the FIXM consists of eight cells in which four 235U fission cells (235U-1, 235U-2, 235U-4, and 235U-5) are used for low-energy neutron detection and four 238U fission cells (238U-1, 238U-2, 238U-4, and 238U-7) are used for fast neutron detection. By normalizing the accelerator power and measurement time used in the experiments with the prototype and NTOX, with the related parameters summarized in Table 1, normalized neutron spectra were obtained, as shown in Fig. 6. The results reveal that the detection efficiency of the prototype is higher than that of a single measurement unit of the FIXM in the energy range of 0.3 eV to 1 keV, although with a more flat response. This demonstrates that Li-enriched scintillators can effectively complement NTOX in the fission resonance energy range.

| Beam power (kW) | Time (hour) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without sample | 10 mm sample | ||

| CLLB | ~140 | 7 | 4 |

| NTOX | ~125 | 50 | 144 |

Capability of neutron total cross section measurement

Calibration of flight path

The neutron energy was determined using the TOF technique. Using the TCutg function in the CERN ROOT framework, neutron events can be extracted from the 2D histogram, and the TOF spectra and neutron energy spectra can be constructed. This requires precise knowledge of the neutron generation time and an accurate flight distance.

Each proton pulse bombarding the spallation target generates prompt high-intensity γ-rays (called γ-flash in the following) that travel at the speed of light and arrive at the detector within 300 ns before the neutrons [32]. Therefore, the time difference between the detected γ-flash and the measured neutron signal can be used to indirectly determine the neutron TOF [33]. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. 4.

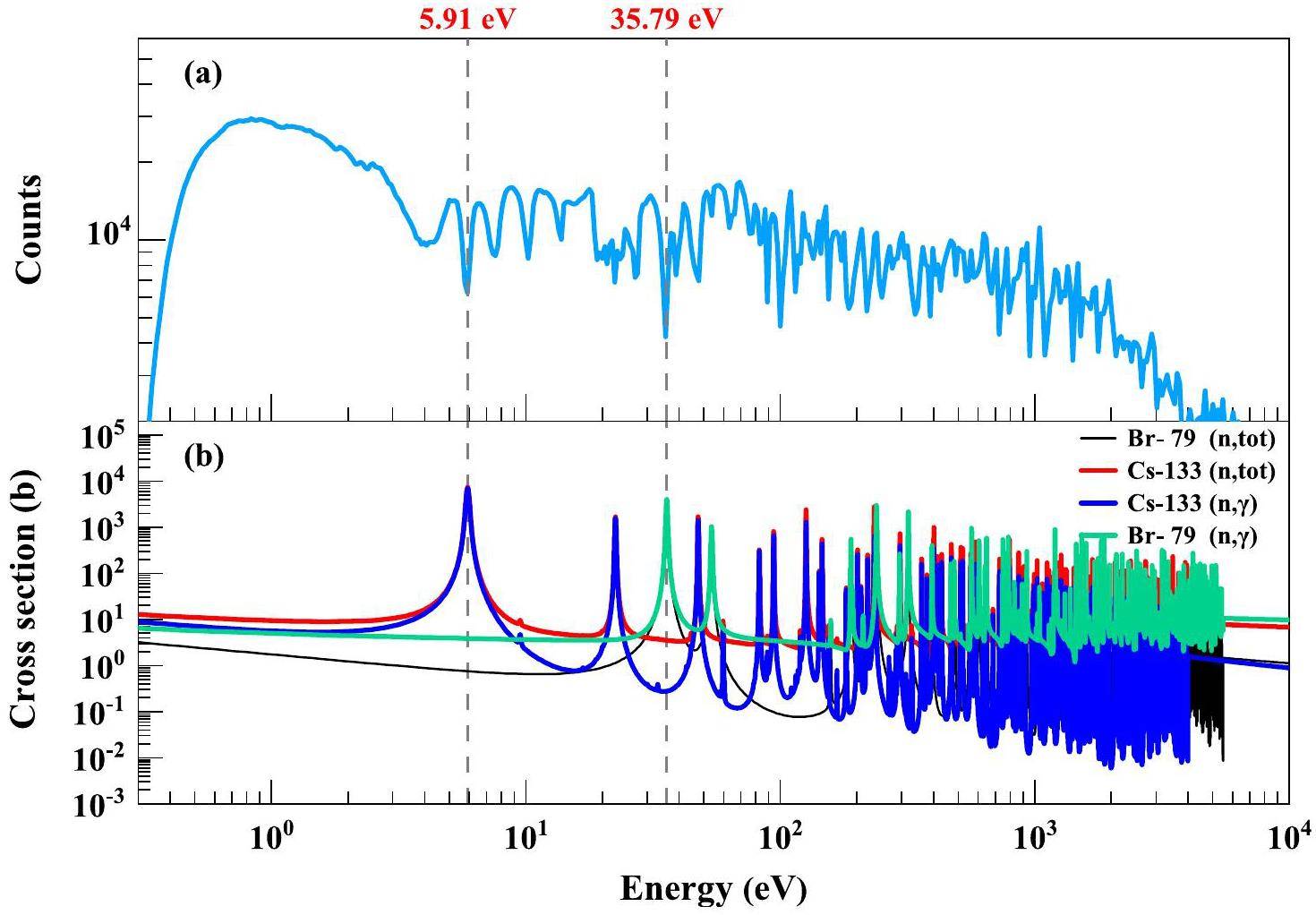

The energy spectra measured by the CLLB detector and the corresponding neutron-induced total and capture cross section for 133Cs and 79Br are shown in Fig. 7. Among the constituent nuclides of the CLLB scintillator, 133Cs at 5.91 eV and 79Br at 35.79 eV demonstrate significant neutron resonance capture effects, which compete with the

The flight distances of neutrons at energy points of 5.91 and 35.79 eV were obtained as 77.4732 and 77.4745 m, respectively. These results are consistent with the experimental geometry, and further validate the reliability of the TOF technique.

Transmission and neutron total cross section

The proton beam intensity was recorded simultaneously during the test and provided data proportional to the neutron yield, which could be used as a normalization parameter for the neutron transmission spectrum as a function of the neutron energy. The transmission T at incident neutron energy En is given by Eq. 6.

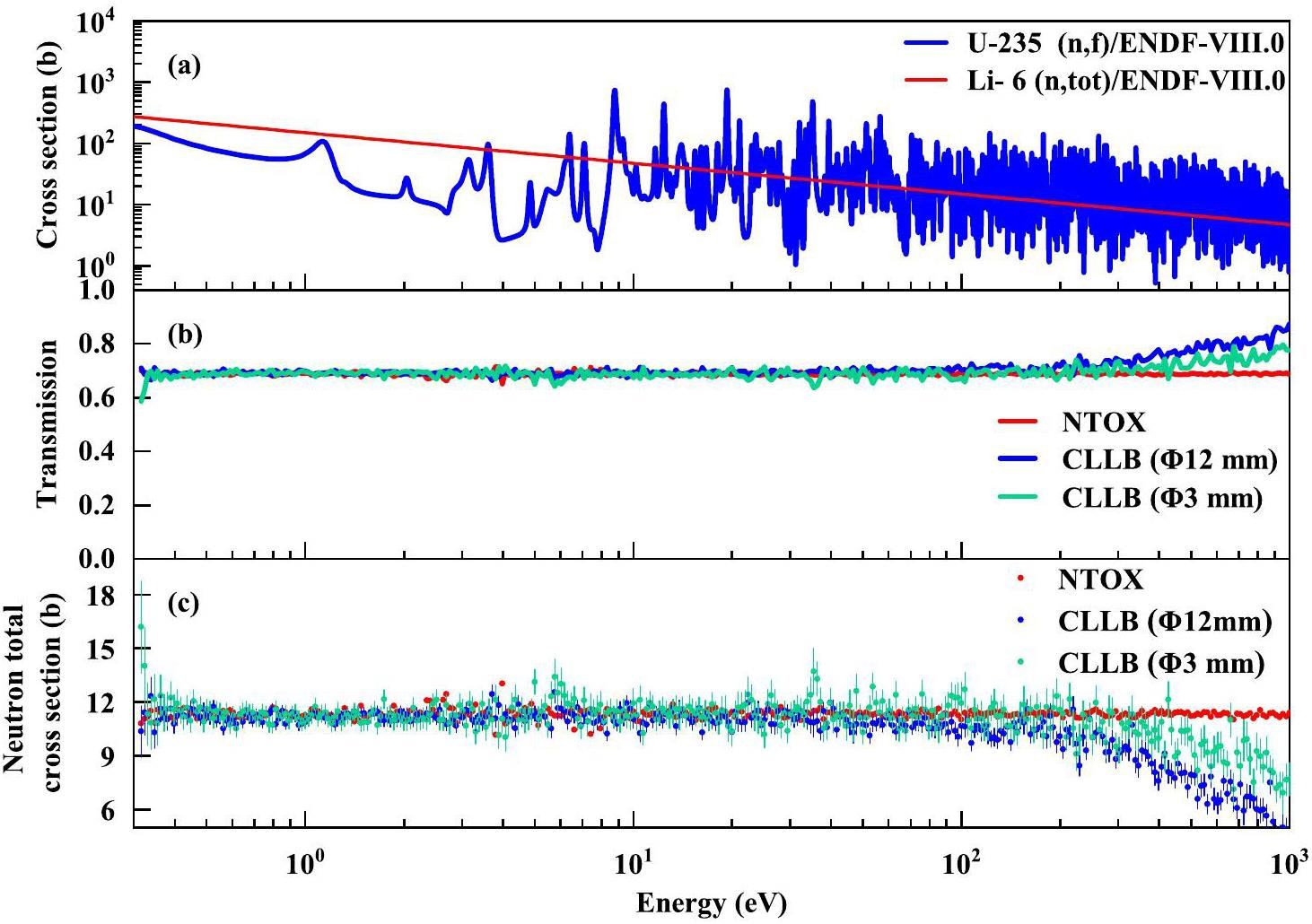

The neutron transmission of the sample was approximately 0.7 in the low-energy region. As shown in Fig. 8(b), a comparison of the neutron transmission spectra obtained by the NTOX and prototype is presented, which indicates that the data analysis is consistent with the experimental results. The neutron total cross section can be determined from the neutron transmission spectrum using Eq. 7.

Figure 8(a) shows the neutron total cross section of 6Li and the fission cross section of 235U. It can be observed that the 6Li cross section is smooth, unlike the strong resonances observed in 235U. Figure 8(c) presents a comparison of the neutron-induced total cross section measured with the prototype and that obtained by the NTOX spectrometer across the energy range of 0.3 to 100 eV. The experimental results were consistent. Based on the neutron beamline test on the Back-n, the prototype of the FAST spectrometer was shown to effectively measure the neutron total cross section in the low-energy region, complementing the data obtained from the NTOX within this energy range. It is anticipated that future improvements will enhance the accuracy and coverage of these measurements.

Discussion

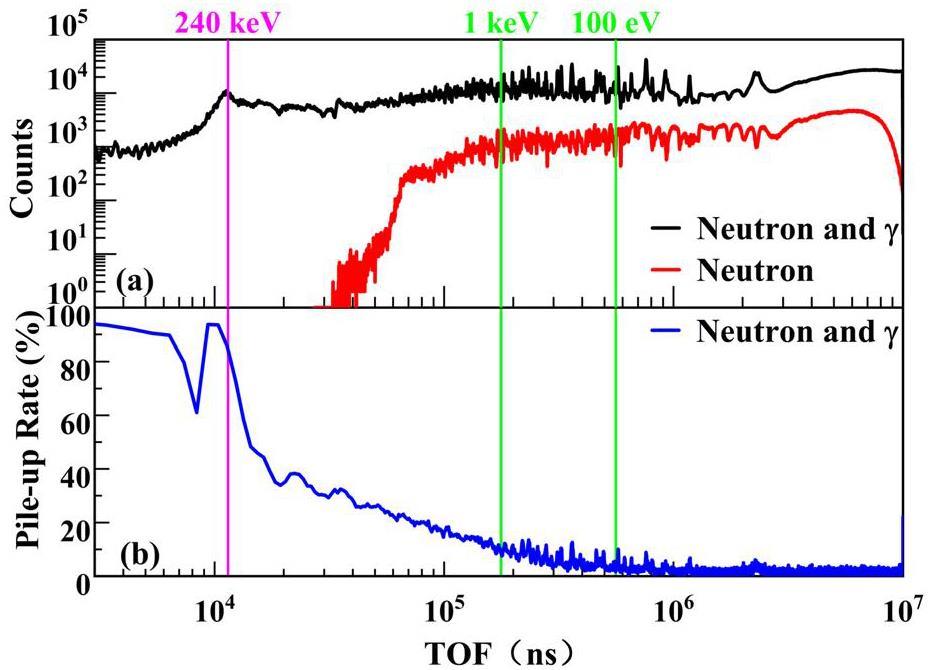

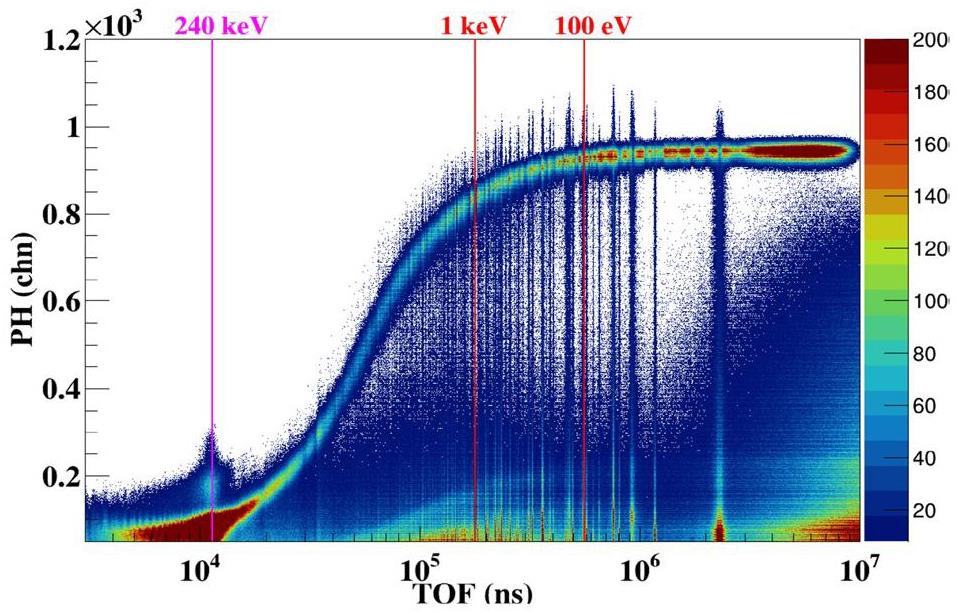

When comparing our work with previous studies, it is important to note that the prototype requires further investigation for high-energy neutron detection. Most scintillation detectors used on the Back-n beamline are inevitably affected by the intense γ-flash, characterized by an extremely high instantaneous flux rate, which results in pile-up signals in the detector upon arrival of the γ-flash. Figure 9(a) illustrates the TOF spectra for mixed neutron and γ-ray events as well as neutron-only events, showing relatively smooth profiles. The characteristic peak at 240 keV clearly resulted from the

A distinct band-like cluster is observed, which aligns with the expected characteristics of the neutron signals based on the reaction energy analysis in Fig. 10. This band was combined with that shown in Fig. 4 for the neutron/γ discrimination using the TCutg tool in the ROOT framework. As the TOF increases, the amplitude of the signals from the band-like cluster increases to a saturation level, indicating an energy release from the (n,α) reaction of 6Li. This phenomenon indicates that the light output of the scintillator was suppressed after irradiation from the high-intensity γ-flash. Some events then emitted rare fluorescence owing to the suppression and generated no signals beyond the threshold. This explains the lower counts in the high-energy region and the lower measured cross section shown in Fig. 8(c).

Two primary factors were hypothesized to contribute to these results and warrant further investigation. One of the reasons for detector malfunction is the strong γ-flash, which can cause the scintillator to fail within a short time. The prolonged signal output time induced by the γ-flash leads to a detector abnormal time of approximately 350 µs. Given the neutron flight path length of approximately 77.47 m, this abnormal time imposes a constraint on the maximum neutron energy, which is explored in this analysis (approximately 1 keV). Neutrons with energies exceeding this threshold experience suppressed scintillation efficiency, resulting in pulse amplitudes that are significantly reduced compared with those of lower-energy neutrons. As a consequence, this limitation may restrict the upper limit of the detectable neutron energy range of the prototype on the white neutron source to between 0.3 and 100 eV. Another factor is that the S14160 series SiPM from Hamamatsu may experience saturation under a high photon flux because the photon arrival intervals are shorter than the recovery time of the microcells in strong γ-ray radiation fields. Simultaneously, thermally generated photoelectrons cause dark counts, which are indistinguishable from actual photon events, further degrading the resolution of the CLLB scintillator coupled with the SiPM.

Conclusion

A prototype FAST spectrometer using a side-readout CLLB scintillator coupled with a SiPM array was developed. The prototype was tested using the broad-energy pulsed neutron beamline of the Back-n beamline at the CSNS. To observe the feasibility of the prototype for neutron total cross section measurements, natPb samples were carefully characterized. The test results obtained by the developed prototype showed good consistency with those measured by the NTOX in the 0.3 to 100 eV energy range, and the detection efficiency was significantly higher than that of the NTOX. Preliminary results indicate that the prototype can complement the NTOX for neutron total cross section measurements in the low-energy range. Further improvements are planned to extend the energy range coverage of the spectrometer.

In the future, a gated technique [36] will likely be applied to restore the prototype response and reduce interference from the γ-flash. This technique enables the CLLB scintillator to temporarily block or filter signals during the γ-flash-induced suppression of scintillation efficiency. By focusing on neutron detection, the suppression effects can be reduced and the energy range coverage capability of the FAST spectrometer for neutron total cross section measurements can be enhanced.

Newly Evaluated Neutron Reaction Data on Chromium Isotopes

. Nuclear Data Sheets. 173, 1-41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2021.04.002Neutron total cross section measurements of polyethylene using time-of-flight method at KURNS-LINAC

. J. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 57, 1-8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2019.1647894The neutron transmission of natFe, 197Au and natW

. Eur. Phys. J. A. 54, 81 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2018-12505-7New Measurement of the Charge Radius of the Neutron

. Physical Review Letters. 74, 2427-2430 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2427Back-n white neutron facility for nuclear data measurements at CSNS

. J. Instrum. 12, 1748-0221 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/12/07/P07022Back-n white neutron source at CSNS and its applications

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00846-610B-doped MCP detector developed for neutron resonance imaging at Back-n white neutron source

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 142 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01512-3Measurement of the neutron total cross section of carbon at the Back-n white neutron beam of CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 139 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0660-9A multi-cell fission chamber for fission cross-section measurements at the Back-n white neutron beam of CSNS

. Nucl. Instr. Methods A. 940, 486-491 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2019.06.014New Maxwellian averaged neutron capture cross sections for 35,37Cl

. Physical Review C. 65,Measurements of the total cross section of natBe with thermal neutrons from a photo-neutron source

. Nucl. Instr. Methods B. 410, 158-163 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00846-6The total cross section and resonance parameters for the 0.178 eV resonance of 113Cd

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods B, 267, 2345-2350 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2009.04.010Neutron transmission and capture measurements and resonance parameter analysis of neodymium from 1 to 500 eV

. Nuclear science and engineering. 153, 8-25 (2006). https://doi.org/10.13182/NSE06-A2590A system for differential neutron scattering experiments in the energy range from 0.5 to 20 MeV

. Nucl. Instr. Methods A. 620, 2-3 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2010.04.051Proton-recoil detectors for time-of-flight measurements of neutrons with kinetic energies from some tens of keV to a few MeV

. Nucl. Instr. Methods A. 575, 449-455 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.02.096Characterization of the new scintillator Cs2LiYCl6:Ce3+

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 11 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0342-4Nondestructive technique for identifying nuclides using neutron resonance transmission analysis at CSNS Back-n

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01367-8Advances in nuclear detection and readout techniques

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01359-0Conceptual design of a Cs2LiLaBr6 scintillator-based neutron total cross section spectrometer on the back-n beam line at CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 3 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01152-5Selected properties of Cs2LiYCl6, Cs2LiLaCl6, and Cs2LiLaBr6 scintillators

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 58, 333-338 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2010.2098045Measurement of the neutron flux of CSNS Back-n ES#1 under small collimators from 0.5 eV to 300 MeV

. Eur. Phys. J. A. 60, 63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01272-zMeasurement of Br(n,γ) cross sections up to stellar s-process temperatures at the CSNS Back-n

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 180 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01337-6Determination of resonance parameters and their covariances from neutron induced reaction cross section data

. Nuclear Data Sheets. 113, 3054-3100 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2012.11.005General-purpose readout electronics for white neutron source at China Spallation Neutron Source

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 89,ROOT—A C++ framework for petabyte data storage, statistical analysis and visualization

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 2499-2512 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2009.08.005Characterization of the neutron/γ-ray discrimination performance in an EJ-301 liquid scintillator for application to prompt fission neutron spectrum measurements at CSNS

. Radiat. Meas. 151,Performance of real-time neutron/gamma discrimination methods

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01160-5FPGA implementation of 500-MHz high-count-rate high-time-resolution real-time digital neutron-gamma discrimination for fast liquid detectors

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 136 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01441-1Measurement of the neutron-induced total cross sections of natPb from 0.3 eV to 20 MeV on the Back-n at CSNS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01370-zENDF/BVIII.0: the 8th major release of the nuclear reaction data library with CIELOproject cross sections, new standards and thermal scattering data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 148, 1-142 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2018.02.001In-beam gamma rays of CSNS Back-n characterized by black resonance filter

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01553-8New measurement of the neutron-induced total cross-sections of natCr in a wide energy range on the Back-n at CSNS

. Chinese Physics C. 48,Simulation and test of the SLEGS TOF spectrometer at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 47 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01194-3Measurement and analysis of the neutron-induced total cross-sections of 209Bi from 0.3 eV to 20 MeV on the Back-n at CSNS

. Chinese Physics C. 47,Development of gated fiber detectors for laser-induced strong electromagnetic pulse environments

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 58 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00898-8The authors declare that they have no competing interests.