Introduction

FLASH radiotherapy (RT) is a new technology that delivers radiation at ultra-high dose rates at orders of magnitude higher than those of conventional clinical RT [1, 2]. Recent results from preclinical studies with electron [3], photon [4-6], and proton [7-11] beams have shown that compared to conventional RT, FLASH RT can achieve similar tumor control while protecting normal tissues, which greatly increases the therapeutic window. However, for carbon ions, only a few laboratories can conduct these experiments. Compared with commercial proton RT instruments based on cyclotrons[12], heavy-ion accelerator technology has been greatly restricted[13, 14]. Because all currently operating carbon-ion treatment facilities use compact synchrotrons, they cannot satisfy the dose-rate requirements for FLASH treatment [15-17]. However, the protective mechanisms of FLASH RT remain unclear. Many studies have reported that the FLASH effect needs to be characterized not only by the average dose rate but also by the beam delivery parameters [18]. Therefore, accurate and fast beam monitoring and dosimetric determination are crucial for the potential clinical benefits of this new technology and the promotion of its clinical transformation[19-21]. Dosimetric protocols such as those proposed by the IAEA [22] and AAPM [23] recommend an ionization chamber (IC) for the reference dosimetry of therapeutic photons, electrons, protons, and heavy ion beams [24]. However, the ion recombination and space-charge effects in ICs have been widely investigated using FLASH RT dosimetry [25].

This is mainly due to the fact that the dose per pulse of the photon beam generated by flattening filter-free linear accelerators increases by approximately 0.8 mGy, and the electron beam used in the operation increases by 3–130 mGy, compared to the conventional photon beam generated by flat filter linear accelerators, which increases by approximately 0.3 mGy. In particular, the dose per pulse of FLASH RT increases by approximately 10–5000 mGy and requires the release of a large amount of dose in a very short time. Typically, the dose rate needs to be higher than 40 Gy/s.

The charge released in the IC is related to the absorbed dose. However, because of ion recombination, attachment, diffusion, and space-charge effects, the charge collected at the collector electrode is smaller than the charge released in the IC. In particular, at the ultrahigh dose rate of FLASH RT, a significant ion recombination effect is observed in the IC, and there is a large deviation in the direct application of the current standard protocol. In addition, to use the IC as a reference dosimeter at ultra-high dose rates, the effect of ion recombination must be reconsidered. Ion recombination is a complex phenomenon that depends on detector characteristics and several properties of the beam, including linear energy transfer (LET), particle type, mode of radiation (continuous, pulsed, or pulsed-swept), and fluence rate. Different theoretical models have been used to describe the collection efficiency in parallel-plate ICs for the two main types of recombination: initial and volume recombination. The initial ionization occurs between the ions created in the same ionization track. This is an independent phenomenon of the ionization current but depends on the ionization density within the track. The second is volume recombination, which occurs between ions originating from different ionization tracks and depends on the ionization current. Consequently, this depends on the beam fluence rate.

For heavy-ion therapy, especially for carbon ions with high LET, both initial and volume recombination have a negative impact on dose measurement. Different theoretical models have been used to describe the dose measurement deviation caused by the saturation effect of ion recombination in the IC. The Jaffe method cannot adequately describe the recombination effect of heavy ions at ultra-high dose rates. It has been proven that the two-voltage method is not suitable for dose-correction calculations for heavy ions. The Niatel model can describe both initial recombination and volume recombination; however, it depends on experimental data to determine the fitting parameters, and there is no experiment to prove that it can describe the saturation effect of carbon ions in the case of FLASH irradiation.

Boag et al. [26] assumed that before the formation of a uniform negative ion cloud, the moving distance of free electrons released in the chamber volume could be neglected, whereas the negative ion cloud drifted slowly through the uniform positive ion cloud, and the positive ion cloud moved in the opposite direction. However, in 1996, Boag et al. [27] used the probability e-ad of free electrons drifting d or longer in air before being attached to electronegative gas molecules. Immediately after a charged particle ionizes the medium between electrodes, there are no negative ions. Free electrons are collected at the anode, while the remainder form negative ions. Negative ions are then formed by the diffusion, drift, and attachment of free electrons to negatively charged gas molecules. The proportion of all the electrons that are not connected to the molecule is the free electron p, which is expressed by Eq. (1) [27]. Accordingly,

When positive and negative ions (including electrons) drift uniformly toward each other, the total number of ion recombinations can be calculated directly because the ion recombination rate generated in the entire overlap region is also uniform [27]. When the negatively charged cloud is initially non-uniform, the ion recombination rate changes throughout the overlap, causing the positive ion cloud to become non-uniform and making the number of recombinations more difficult to determine. Boag et al. [27] provided three approximate formulas,

However, Boag et al. [27] did not express a specific preference for adopting any of these three models under the given experimental conditions. Therefore, they recommended further investigation. Moreover, there is no systematic and comprehensive interpretation of the method and numerical calculation process for reducing ion recombination and space-charge effects in dose measurements under ultra-high dose rates. It has been proven that there is a large deviation at ultra-high dose rates. However, these models cannot accurately estimate the ion recombination correction factors. The lack of a generally accepted model for ultra-high dose rates to accurately measure the dose across a wide range of dose rates and doses remains an issue, especially in FLASH RT studies.

Therefore, in this study, we established a beam-monitoring and dose measurement system to meet the requirements of carbon-ion FLASH preclinical experiments based on the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL). Real-time online dose measurements and beam profile distributions were obtained by reducing the air pressure in the IC. The saturation effect was studied by varying the applied voltage in the FLASH IC. Under different beam currents (dose rates), considering the space charge, ion recombination, attachment, and diffusion effects in the process of carrier movement in the sensitive volume, a model was established based on physical phenomenology, and the correction factors were calculated using finite-element analysis. At the same time, the experimental data were used as the standard to verify and analyze them. This study aims to identify key technical problems and solutions for carbon-ion FLASH projects. Therefore, these detailed dosimetric parameters provide a methodological basis for preclinical FLASH experiments and play a crucial role in providing machine support for the study of carbon-ion FLASH-related mechanisms.

Material and methods

Irradiation terminal and beam line control system of accelerator

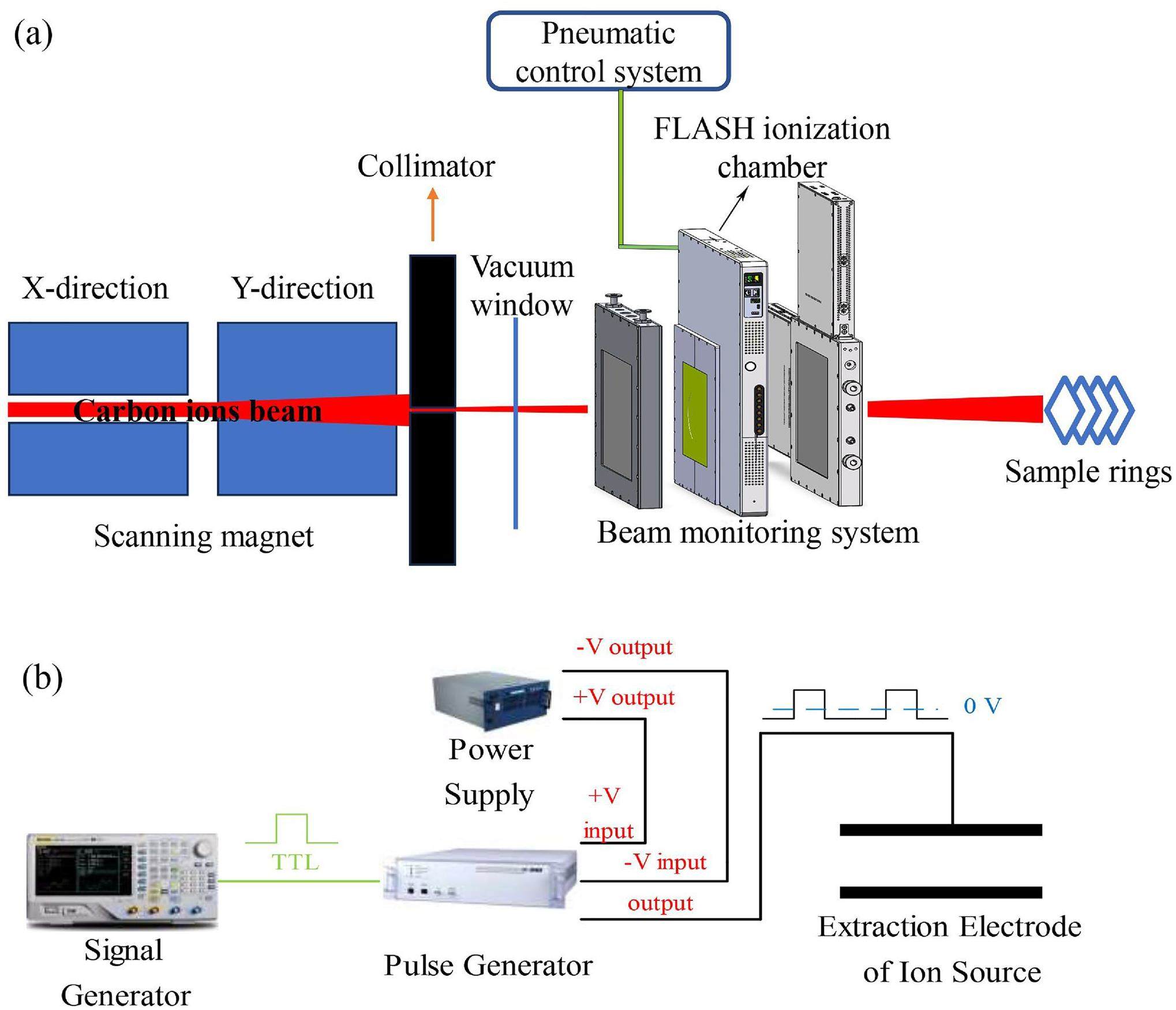

Figure 1a shows the passive beam delivery system installed on the shallow-seated (80.55 MeV/n carbon ions) FLASH irradiation terminal of the HIRFL. Because the accelerator can provide a constant beam current, the scanning magnet deflects the pencil beam quickly and continuously in a zigzag scanning manner to achieve transverse beam diffusion and generate a larger radiation field [31]. The X and Y directions are high- and low-frequency zigzag periodic current-driven magnets that control the target volume of irradiation by adjusting different frequencies in the X and Y directions. Thus, the magnetic scanning system guides the focused beam to draw the target volume at the center of the treatment terminal in a Lissajous or raster-like pattern depending on the difference between the fast and slow frequencies. The terminal monitoring system consisted of three large-area penetrating ICs (Fig. 1a): a dose IC, an integrated dose-position monitoring FLASH IC, and a position monitoring IC. The output signal of the FLASH IC was directly connected to the FEMTO variable-gain low-noise amplifier for I/V conversion, and a small current was directly converted into the available voltage. The data acquisition system was based on a National Instruments (NI) cRIO 9063 with a real-time operating system and an NI 9215 analog input card to achieve rapid acquisition. During the irradiation process, when the dose measured by the dose IC reached a set value, the automatic sample-change system changed to the next sample. If the position IC monitors that the beam profile uniformity does not meet the experimental requirements, the irradiation of the interlocking system is stopped [32, 33].

Through the chopper system, a pulse beam was generated and cut off, and the response accuracy reached the nanosecond level to satisfy the FLASH irradiation requirements. The beam-time structure adjusts the signal characteristics to excite the pulse generator by setting parameters such as the frequency, amplitude, and duty cycle of the pulse through the signal generator. The direct-current (DC) voltage generated by the high-voltage DC power supply enters the pulse generator and is modulated by the transistor-–transistor logic gate signal generated by the signal generator. The output voltage of the high-voltage power supply was compared with the set reference voltage. When the difference between the two reaches a specified threshold, the counter triggers the output pulse signal, and its output is loaded onto the ion source extraction electrode. When the carbon-ion beam is extracted, pulse modulation of the carbon-ion beam current is achieved. A schematic of this process is shown in Fig. 1b.

Physical process analysis

The FLASH IC is based on a parallel-plate IC. The chamber can be simplified as a high-voltage electrode, gas gap, and collection-signal electrode. The air gap thickness was 4 mm. Air was used as the working gas in the experiments. During the experiment, the entire sensitive volume was ensured to have a uniform electric field in the FLASH IC. Simultaneously, there is a high line-energy transfer of the radiation mass, such as carbon ions. We should consider not only volume recombination but also initial recombination based on the amorphous track structure theory [34, 35].

To this end, the following four-step procedure was implemented: (1) Electrons and cations are generated according to the intensity distribution of the ion beam and the resulting ionization density between the two electrodes with a gap size of d. (2) The corresponding charge is recombined according to the coefficients (recombination, attachment, and diffusion coefficients). (3) The electric field in the sensitive volume of the FLASH IC was calculated, and the superposition of the external electric field caused by the applied voltage and the internal electric field generated by the charge carrier was calculated. (4) The electron-ion pair drifts with the calculated electric field.

In the experiment, the particle current density

The finite-element method

The above equations (10–12) are coupled with the partial differential equations without analytical solutions. Therefore, we can obtain the numerical solutions by converting them into ordinary differential equations using a first-order upwind technique, as shown in Equation 15. To this end, the spatial derivative is first used to discretize the term, which produces an ordinary differential equation set (only the time derivative remains). The obtained system can then be integrated numerically [36]. The specific finite-element analysis method is introduced as follows:

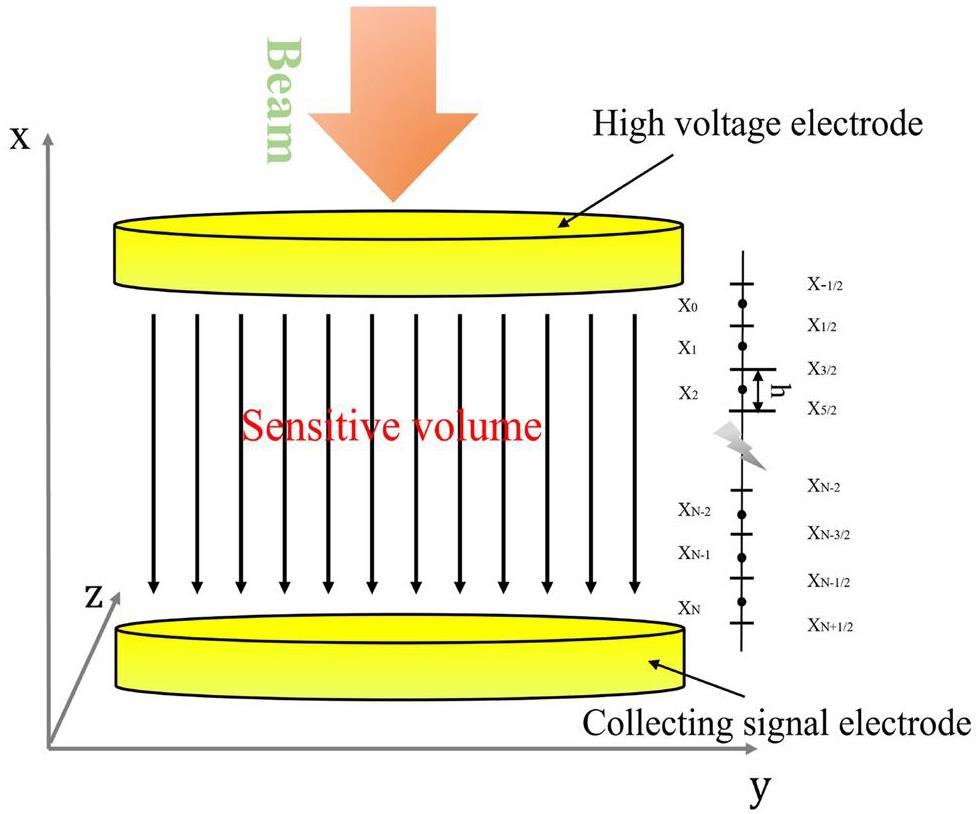

The ks values for the ion recombination and space-charge shielding effects were calculated. Equations (10)—(12) were solved using the finite-element method. The spatial first-order upwind technique was used to implement discretization in Equation (15), and the forward Euler method was used for time integration in Equations (20)–(21). For the numerical solution, the sensitive volume perpendicular to the electrode direction was divided into N bins of size h and two bins outside the sensitive volume (Fig. 2). The standard advection–diffusion reaction model deals with the time evolution of species in a flowing medium such as water or air. The mathematical equations describing this evolution are partial differential equations derived from mass balances. If

Parameters of the numerical solution

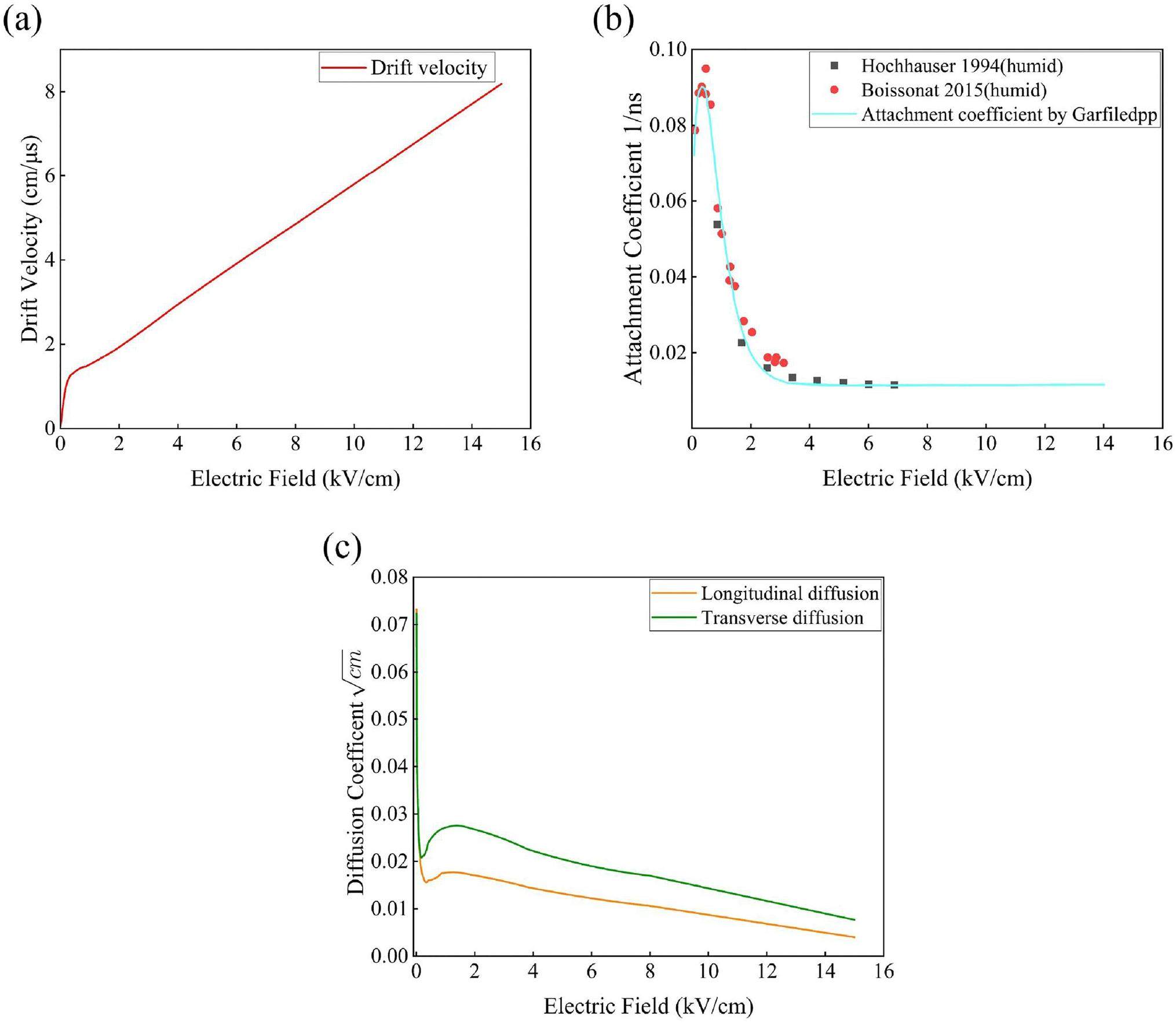

Air was used as the working gas in the experiment. The equation contains several physical parameters: recombination coefficient (α), electron attachment coefficient (γ), diffusion coefficient (D), and ion mobility (μi) (including positive ions, negative ions, and electrons). The electron drift velocity (Fig. 3a) and diffusion coefficient (Fig. 3c) under different electric field strengths were determined using the Garfield++ simulation. We used test data from Hochhäuser et al.[40] and Boissonnat et al. [41] for the spline interpolation to determine the electron attachment coefficient (Fig. 3b). Simultaneously, the positive and negative ion mobilities and diffusion coefficients were good approximation constants for the variation range of the electric field strength of the IC during the experiment. The specific parameters are listed in Table 1.

| Constant | Symbol | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive ion diffusion | D+ | cm2s-1 | 2.82E-2 |

| Negative ion diffusion | D- | cm2s-1 | 4.35E-2 |

| Positive ion mobility | μ+ | cm2V-1s-1 | 1.36 |

| Negative ion mobility | μ- | cm2V-1s-1 | 2.10 |

| Recombination constant (positive negative) | α | cm3s-1 | 1.3E-6 |

| Recombination constant (positive electron) | β | cm3s-1 | 0.4E-6 |

Experimental correction factor

A Faraday cup was used to calibrate the reference dose of the FLASH IC. A relevant description is provided in Ref. [33]. The liberated charges

Results

Dose measurement and profile monitoring of ionization chamber under low pressure

The beam current of the terminal was tested using a Faraday cup to ensure that the PTW Roos-34001 IC was within the normal working range. The extrapolation of the Faraday cup measurements at an ultra-high dose rate (approximately 50 Gy/s) demonstrates that the beam current can fulfill the requirements of FLASH irradiation. Considering the experimental field environment, the carbon-ion beam current at an ultra-high dose rate was measured by reducing the air pressure of the chamber. The replacement of the working gas (such as helium) can alleviate ion recombination but cannot obtain completely satisfactory results at ultra-high dose rates. Considering the experimental environment within the field, the beam current at an ultra-high dose rate was measured by reducing the air pressure within the chamber. The replacement of the working gas (for example, helium) can mitigate ion recombination; however, the results obtained at an ultra-high dose rate are not entirely satisfactory. The large-area real-time beam-monitoring system for carbon-ion FLASH irradiation is susceptible to the effects of reduced electrode plate spacing, owing to the limitations of processing technology and the accuracy of the electrode plate. Additionally, this reduction is prone to a “light” phenomenon, which results in irreversible damage to the detector.

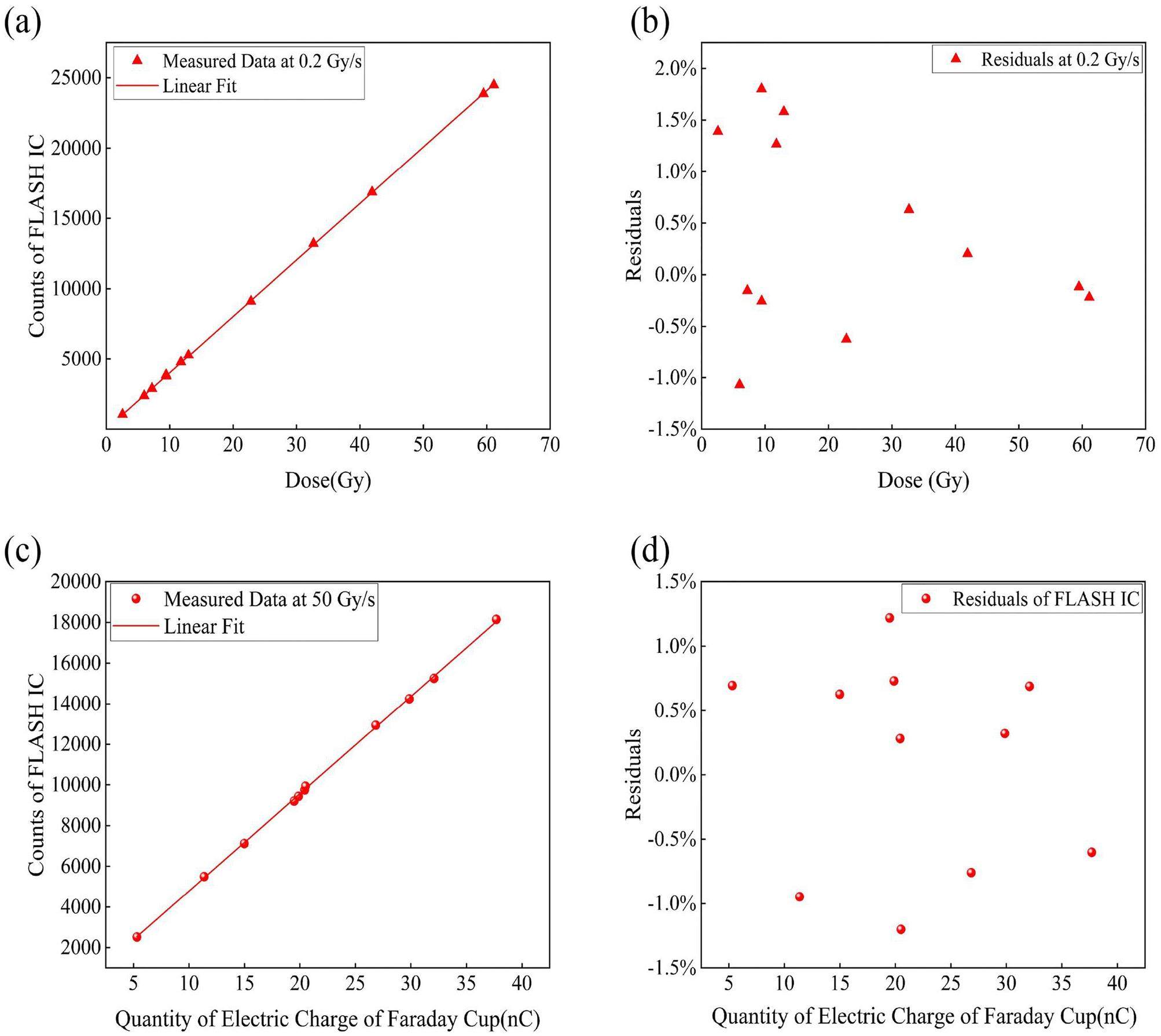

Figure 4(a) shows the dose measurement results of the FLASH IC at a dose rate of approximately 0.2 Gy/s under standard atmospheric pressure. The output of the PTW Roos-34001 IC was used as the reference dose. Fig. 4(b) shows the dose residuals of the FLASH IC. Under the condition of IC pressure of 10 mbar and a dose rate of approximately 50 Gy/s, the dose linear curve (Fig. 4c) and residual diagram (Fig. 4d) of the FLASH IC were obtained. A Faraday cup was used to verify the reference dose of the FLASH IC. The results in Fig. 4 show that the IC can simultaneously meet the beam monitoring and dose measurement requirements of carbon-ion irradiation under conventional clinical and FLASH RT. The residuals were less than 2%, and as the dose increased, the deviation gradually decreased and approached 0%, which meets the requirements for preclinical dose monitoring.

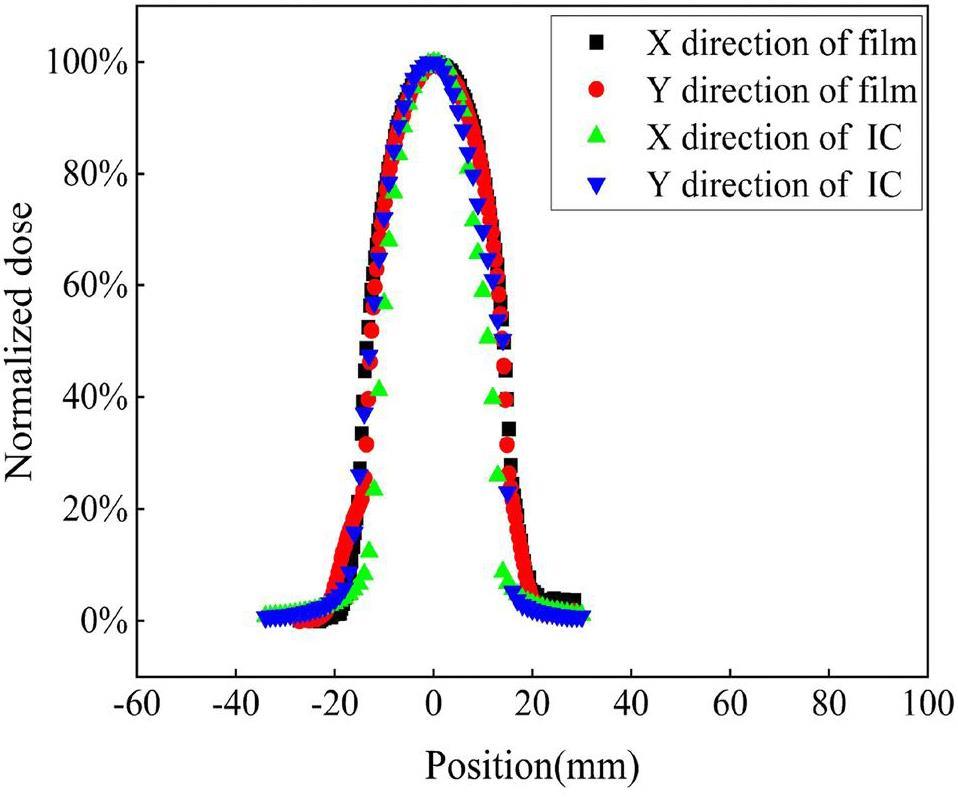

Figure 5 shows that the beam spot was adjusted to approximately 40 mm in diameter, and the beam profile was measured using the FLASH IC and EBT3 films. Because the beam was defocused at the measurement position and the film was placed on the lower surface of the FLASH IC, the results for the film were slightly larger. The FLASH IC can measure the position profile of carbon-ion beams at ultra-high dose rates. During the experiment, the beam-scanning system was adjusted so that different volume targets at the isocenter could be irradiated.

Measuring saturation curve and calculating correction factor

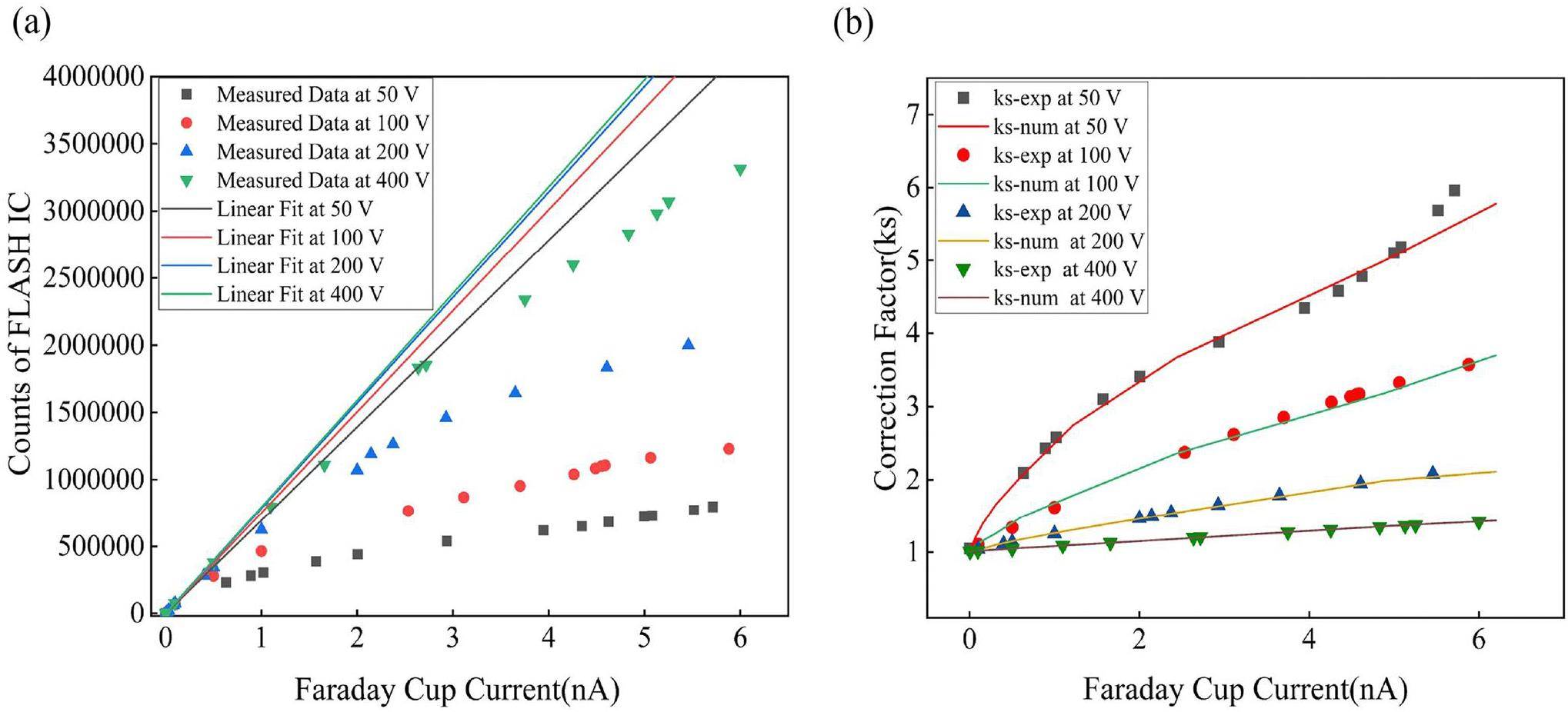

Figure 6a shows that the ion recombination effect at different dose rates was tested by increasing the polarization voltage of the IC. The response of FLASH IC was characterized by a Faraday cup monitoring the beam current to obtain the saturation curve using Eq. (23). The results showed that the recombination effect of ions decreased with increasing polarization voltage. Theoretically, the voltage can be increased in the ionization region to obtain a linear dose curve. However, owing to the high polarization voltage applied at the ultra-high dose rate, the IC will be “light”; thus, the maximum polarization voltage is set to 400 V. Figure 6b shows the correction factor obtained by experimental calculation and model calculation. The results indicate that the correction factor calculated using the model is in good agreement with the experimental results. During the experiment, when a higher polarization voltage was applied, such as 200 or 400 V, the maximum deviation in the results was less than 5%. However, when the polarization voltages were 100 V and 50 V, the maximum deviation was less than 10%.

Discussion

At present, the shallow-seated carbon-ion FLASH treatment device based on HIRFL can realize subtle modulation of the beam current through chopper control technology and can arbitrarily change the pulse width and repetition frequency. From the perspective of treatment devices, this has been proven to be sufficient for preclinical experiments. To ensure that beam position profile monitoring and dose measurement can be carried out in real time during the irradiation process, a large-area real-time monitoring FLASH IC and beam feedback control system with adjustable air pressure were designed.

Combined with previous work [33], Figs. 4(c) and (d) show that the method of reducing the chamber air pressure can satisfy the FLASH irradiation dose measurement of carbon ions at ultra-high dose rates. The essential reason for this is that when the air pressure in the chamber is reduced, the number of gas molecules is significantly decreased, which reduces the generation of electron-ion pairs and the probability of collision with particles; thus, the saturation effect is eliminated. In addition, with a decrease in gas molecules, the attachment, ion recombination, and space-charge effects are significantly reduced, whereas the mobility is significantly increased, which positively impacts accurate dose measurement. The method proposed in this paper can meet beam monitoring and dose measurement requirements at different dose rates. We found that increasing the polarization voltage did not improve the saturation effect at ultra-high dose rates. Therefore, a finite-element analysis method based on the drift, diffusion, attachment, and recombination of electron-ion pairs was proposed to perform dose correction on the saturation curve. Additionally, the experimental data were compared. When the beam current measured using the Faraday cup was less than 4 nA, the model correction was in good agreement with the experimental calculation results, and the maximum deviation was less than 2%, satisfying the dose monitoring requirements of the FLASH irradiation process. When the beam current was greater than 4 nA, the space-charge effect was significantly enhanced, which distorted the applied electric field. Although the influence of the space-charge effect on the results was considered in the model, the recombination coefficient between ions is generally determined by a semi-empirical formula that combines the model and experimental data, which is a very complex physical and chemical process [43]. The recombination coefficient (α) in the numerical calculation model is a variable that makes it difficult to determine whether it is found in the actual measurements or in this study. In this study, no better calculation method for the recombination coefficient was found; therefore, the analysis was due to the deviation introduced by its uncertainty.

For real-time monitoring of large-area doses, we adopted a more effective method of reducing the pressure in the IC to avoid ion recombination and space-charge effects. This work begins with the working principle of the IC, combines physical phenomena to analyze the initial recombination and volume recombination of carbon ions with a relatively high LET, and verifies this through experiments. To eliminate the influence of the saturation effects introduced during dose measurement, it is possible to reduce the sensitive volume from the detector design to reduce the ion drift path and reduce the drift time or improve the polarization voltage to increase the drift speed. Using a working gas with a higher average ionization energy can reduce the production of electron-ion pairs. Alternatively, a combination of the aforementioned methods may be employed. However, from the perspective of physical theory, it is evident that no single method can effectively eliminate the saturation effect. Because FLASH RT increases the dose rate by nearly three orders of magnitude compared to conventional RT, reducing the pressure from atmospheric pressure to less than 10 mbar can meet its requirements, and for electron beam FLASH irradiation with extremely high dose rates (>0×105 Gy/s), this method can meet the needs very well.

Conclusion

We conducted research on carbon-ion FLASH therapy based on the HIRFL shallow-seated irradiation terminal. A set of beam-monitoring control and dose measurement systems was developed and designed. A finite-element calculation method for the correction factor of the dose saturation curve based on physical phenomenology principles was proposed to realize related research under large-area FLASH IC at an ultra-high dose rate of carbon ions. Considering that the model accuracy of the relevant physical parameters is crucial to the results, its uncertainty leads to significant errors. In the future, we will systematically evaluate and determine physical parameters to reduce model deviation.

In this paper, ideas and methods for dose measurement based on carbon-ion FLASH irradiation are proposed. However, further experimental verification is required to study the biological mechanisms related to FLASH RT, including the effects of different radiation qualities, beam pulse structures, and other factors. Many unsolved problems remain in the field of FLASH. The experimental platform needs to be improved to obtain a higher and more stable average dose rate and to accurately adjust the different durations and repetition frequencies to provide more parameter studies for clinical trials of FLASH to better promote the clinical transformation of FLASH RT.

Design of a rapid-cycling synchrotron for flash proton therapy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 145 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01283-3FLASH radiotherapy

. Chinese Journal of Radiation Oncology 28, 11(2019). https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1004-4221.2019.11.014Dosimetric characterization of a novel UHDR megavoltage X-ray source for FLASH radiobiological experiments

. Sci. Rep. 14, 822(2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50412-wUltrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the differential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice

. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 245(2014). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aba4525FLASH radiotherapy using high-energy X-rays: Current status of PARTER platform in FLASH research

. Radioth Oncol. 190,First demonstration of the FLASH effect with ultrahigh dose rate high-energy X-rays

. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 166, 44-55 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2021.11.004Clinical Application of Proton Therapy Technology

. China Medical Devices 3, (2022). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-1633.2022.03.037Recent progress in pencil beam scanning FLASH proton therapy: a narrative review

. Therap. Radiol. Oncol. 6, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.11722Focused proton beam generating pseudo Bragg peak for FLASH therapy

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 1032,Proton linac-based therapy facility for ultra-high dose rate (FLASH) treatment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00872-4Research progress on several aspects of advanced high intensity cyclotron technology at CIAE

. Atomic Energy Science and Technology. 43, 129-146 (2009). (in Chinese)Development and application of compact high-current proton cyclotron at China Institute of Atomic Energy

. Atomic Energy Science and Technology 58, 465-474 (2024). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2024.youxian.0514 (in Chinese)Design of the extraction system of heavy ion medical cyclotron

. High Power Laser and Particle Beams. 11, 2911-2994 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3788/HPLPB20132511.2991 (in Chinese)Development and application of the first carbon ion therapy system in China

. Chinese Journal of Medical Instrumentation 46, 517-522 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-7104.2022.05.009 (in Chinese)Radial probe detector system in the cyclotron of Heavy Ion Medical Machine

. High Power Laser and Particle Beams 35,Development of FLASH radiotherapy and its application in cancer therapy

. China Cancer 31, 924-928 (2022). https://doi.org/10.11735/j.issn.1004-0242.2022.11.A012Design of a compact structure cancer therapy synchrotron

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 756, 19-22 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.04.050Faster and safer? FLASH ultra-high dose rate in radiotherapy

. The British journal of radiology. 1082, 91 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170628The effects of abnormal exposure on individual dose monitoring with TLD dosimeter

. Health Phys. 127, 730-733 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1097/HP.0000000000001874Development of a hybrid line dosimeter using lead (II) iodide and GdOS:Tb for dose monitoring in brachytherapy

. J. Instrum. 18, 9 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/18/09/P09042Design and optimization of a dedicated Faraday cup for UHDR proton dosimetry: Implementation in a UHDR irradiation station

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A 1064,AAPM’s TG-51 protocol for clinical reference dosimetry of high-energy photon and electron beams

. Med. Phys. 9, 26 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1118/1.598691Development of an ultra-thin parallel plate ionization chamber for dosimetry in FLASH radiotherapy

. Med. Phys. 49, 4705-4714 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15668Evaluation of two-voltage and three-voltage linear methods for deriving ion recombination correction factors in proton FLASH irradiation

. IEEE T. Radiat. Plas. Med. Sci. 6, 263-270 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/TRPMS.2021.3078885Ionization measurements at very high intensities

. British J. Radiol. 274, 601-611 (1952). https://doi.org/10.1259/0007-1285-23-274-601The effect of free-electron collection on the recombination correction to ionization measurements of pulsed radiation

. Phys. Med. Biol. 5, 41(1996). https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/41/5/005Kinetic theory and electric conduction through gases

. Nature 123, 675-676 (1929). https://doi.org/10.1038/123675a0A new model for volume recombination in plane-parallel chambers in pulsed fields of high dose-per-pulse

. Phys. Med. Biol. 22, 62 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/aa8985Heavy-ion conformal irradiation in the shallow-seated tumor therapy terminal at HIRFL

. Med. Biol. Eng. Comp. 11, 45 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-007-0245-3Advances in nuclear detection and readout techniques

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01359-0Preliminary study of low-pressure ionization chamber for online dose monitoring in FLASH carbon ion radiotherapy

. Phys. Med. Biol. 2, 69 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/ad13d0FLASH radiotherapy with carbon ion beams

. Med. Phys. 3, 49 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.15135Applications of amorphous track models in radiation biology

. Radiat. Environ. Biophys. 2, 38 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/s004110050142Über die von der molekularkinetischen Theorie der Wärme geforderte Bewegung von in ruhenden Flüssigkeiten suspendierten Teilchen

. 17, 549 (1905).The significance of the lifetime and collection time of free electrons for the recombination correction in the ionometric dosimetry of pulsed radiation

. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 27, 431 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/27/3/001Chambres d’ionisation en Protonthérapie et hadrontherapie

DissertationInitial recombination in a parallel-plate ionization chamber exposed to heavy ions

. Phys. Med. Biol. 12, 43 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/43/12/012The ion–ion recombination coefficient α: comparison of temperature- and pressure-dependent parameterisations for the troposphere and stratosphere

. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 22 (2022). https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-12443-2022The authors declare that they have no competing interests.