Introduction

Safety and reliability are the main issues in developing future advanced nuclear energies [1, 2]. However, structural materials are facing significant challenges, e.g., higher temperatures, higher neutron irradiation doses, and more corrosive environments, particularly as nuclear reactors advance toward fourth-generation concepts [2-4]. In addition to the complex operating environment, mechanical stress- induced local deformation is known to be a governing factor that complicates the behavior of in-reactor materials [5]. In the widest commercialized pressurized water reactor (PWR), irradiation-assisted stress corrosion cracking (IASCC) was recognized as the primary cause of failure of key components within the reactors [6-8]. Interest in elucidating the mechanism of IASCC has thus been continuous for more than half a century [9]. In contrast to the breath of studies on IASCC in PWRs, our knowledge about the synergistic effects of deformation and the operating environment on material properties remains limited for the Generation IV nuclear reactors [10].

The molten salt reactor (MSR) is one of the six most promising Generation IV fission reactors [11-13]. The GH3535 alloy (Ni- 17Mo- 7Cr) is specially developed as the main structural material of the MSR for its superior corrosion resistance to molten salt. Numerous studies have been performed to investigate the essential mechanism of property degradation of the GH3535 alloy under irradiation [14-16], molten salt corrosion [17, 18], and stress fields [19, 20], respectively. i) Previous research has highlighted the role of helium bubbles, which originally form owing to the transmutation reaction of neutrons with boron and nickel in the GH3535 alloy in the reactor [21]. The typical irradiation defects lead to swelling, hardening, and embrittlement of the GH3535 alloy [16, 22, 23]. ii) Specifically, in high-temperature molten salt environments, outward diffusion and coalescence of helium bubbles were observed [24-26], leading to the formation of holes on the surface of the alloy, which further accelerated the matrix corrosion of nickel-based alloys in fluoride molten salt. iii) Moreover, under mechanical loading, local deformation and dislocations are involved. Helium bubbles were elongated and necked after multiple dislocation cutting accompanied by internal surface diffusion. With further deformation, coalescence of adjacent bubbles led to the formation of void in the high bubble density zone, while fragmentation produced a bubble-free channel in the low bubble density zone [27, 28]. Radiation-induced dislocation loops were gradually fragmented or cleared by mobile dislocations, or annihilated by vacancies generated during irradiation to produce the defect-free channels. This process resulted in a sharp reduction in the number of dislocation loops [29, 30]. The above behaviors of helium bubbles under near serving condition may manifest diversification in the microstructure evolutions of alloys, degrade the properties of the GH3535 alloy, and further jeopardize the operation safety of MSRs. Thus, it is crucial to clarify the mechanism of helium bubble evolution under the complex environment combined with irradiation, molten salt corrosion and the stress field.

In this study, helium ion irradiation was carried out on the GH3535 alloy to introduce helium bubbles. Mechanical loading was applied to irradiated and unirradiated samples to achieve plastic deformation of 1%, 3%, 10%. Subsequently, all the samples were exposed to fluoride molten salt at 750 ℃ for 300 h. The Helium bubble evolution, microstructural variations, and elemental distributions before and after corrosion were analyzed in detail to investigate the synergistic effects of irradiation and deformation on corrosion performance. Furthermore, the mechanisms of the helium bubble migration were discussed in irradiated samples with different strains after molten salt corrosion, which helps us better understand and predict the long-term service performance of alloys in MSRs.

Materials and experimental methods

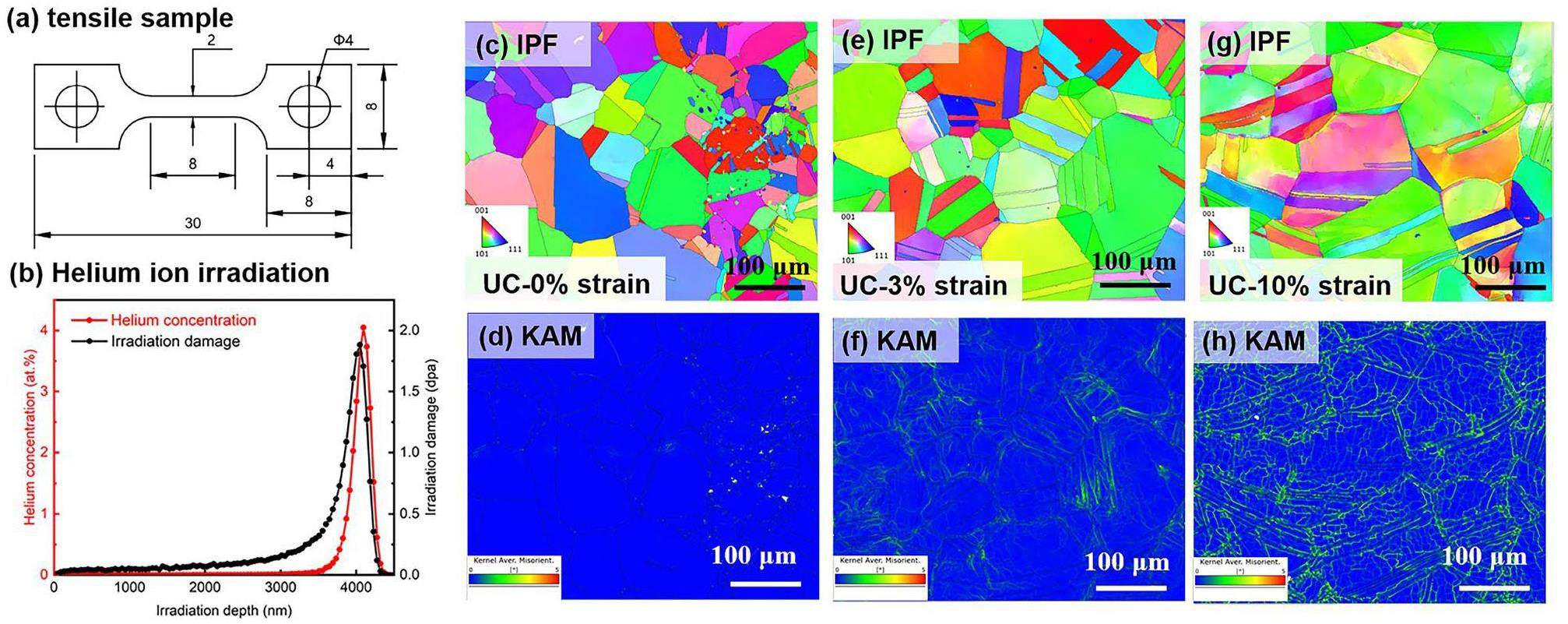

The GH3535 alloy was fabricated into dog-bone shaped tensile samples with a gage dimension of 8 mm × 2 mm × 1 mm (Fig. 1a). The tensile samples were mechanically polished to obtain a mirror- smooth surface. Electropolishing was performed in mixed solution with 10 vol% DI water, 40 vol% C3H8O3, and 50 vol% H2SO4 at 40 V for approximately 10 s to remove the surface stress layer.

Irradiation was performed on the tensile samples with 2.5 MeV helium ions to fluences of 1×1017 ions/cm2 at 750 ℃ using a 4 MV pelletron accelerator located at the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics, Chinese Academy of Science. The irradiation damage (dpa) and He concentration as functions of irradiation depth were calculated via the “Kinchin-Pease quick calculation” mode in the Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM) software (Fig. 1b). The maximum irradiation depth was about 4.5 μm from the surface. The peak He concentration was around 4.05 at.% at a depth of about 4.1 μm, and the peak irradiation damage was around 1.88 dpa at a depth of about 4.05 μm. The irradiated and unirradiated samples were stretched to real plastic strain of 1%, 3% and 10% respectively at a strain rate of 0.005/min, referenced as IC-1, IC-3, IC-10, UC-1, UC-3, and UC-10, respectively. Fig. 1(c)-(h) depict the inverse pole figure (IPF) map and kernel average misorientation (KAM) map of the GH3535 alloy followed by 0%, 3%, and 10% strain. With increasing strain, more grains underwent local deformation. And UC-10% had the greatest stress concentration, especially along grain boundaries.

A molten salt corrosion experiment was carried out on the unirradiated and irradiated tensile samples followed by different plastic strains. The samples were immersed in a dried high-purity graphite crucible filled with 148 g of purified FLiNaK (LiF-NaF-KF: 46.5-11.5-42 mol.%) salts at 750 ℃ for 300 h. The main alloying impurity elements were reduced to less than 10 ppm (1.94 ppm Fe, 2.52 ppm Cr, 9.76 ppm Ni), which was estimated by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The whole experimental process was carried out in an argon gas glove box with oxygen and water contents less than 5 ppm. Details of the suspension methods for samples are available in Ref. [31]. The irradiation-induced defects and the microstructures of the samples before and after molten salt corrosion were characterized by transmission electron microscope (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F20). TEM samples were prepared using a focused ion beam (FIB, FEI Helios nanolab 600). The thickness of all samples was calculated to be 70 nm by convergent beam electron diffraction (CBED) technique. The average size and the number density of helium bubbles were estimated over 5 regions of TEM images at 100 nm scale. The variation trend of alloying elements was measured by Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) using an electron probe micro-analyzer (EPMA, SHIMADZU EPMA-1720 H) for the samples after molten salt corrosion.

RESULTS

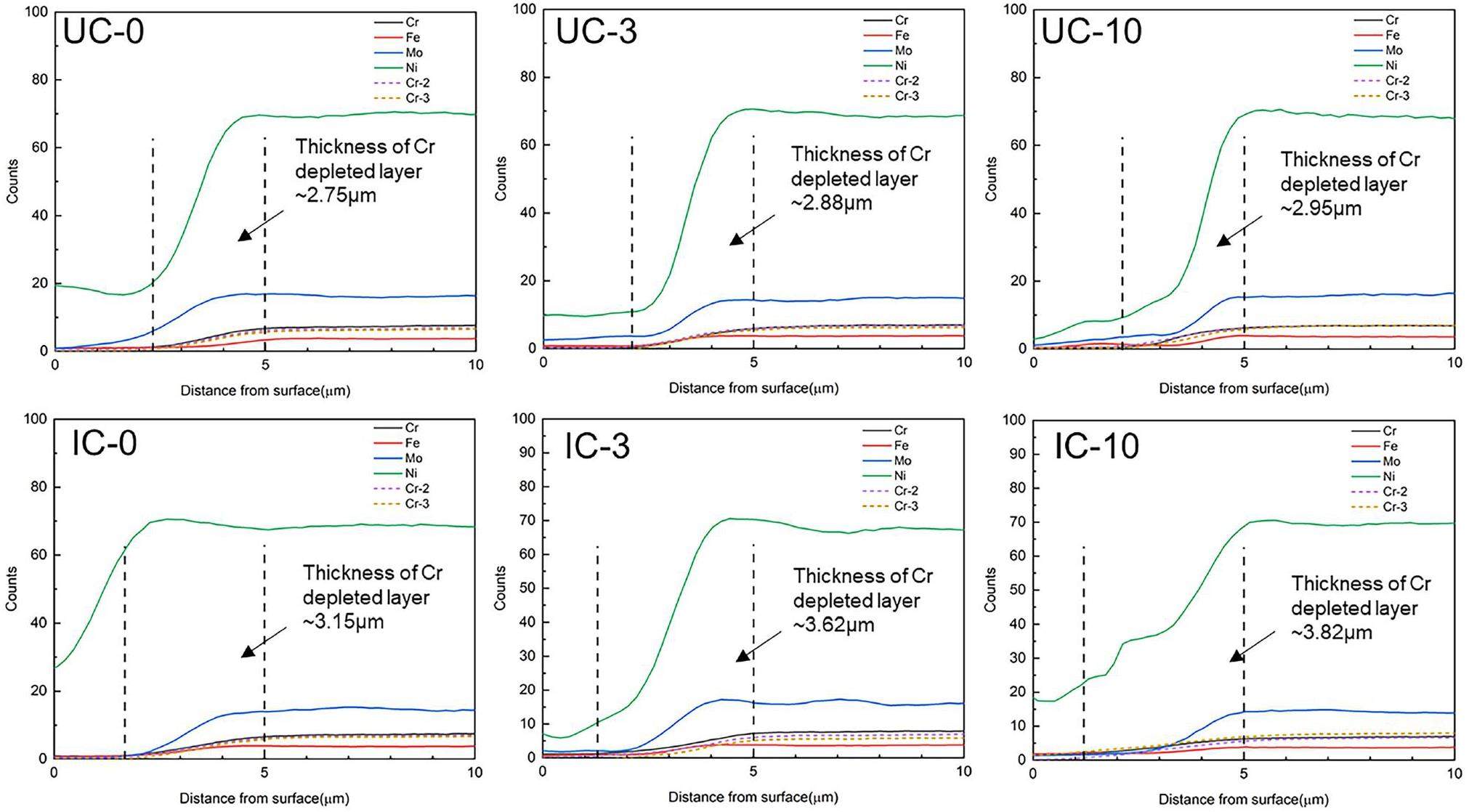

For molten salt corrosion, the thickness of the Cr depletion layer is used to characterize the corrosion properties of GH3535 due to the preferential corrosion of active alloying elements in the high-temperature molten salt, according to their Gibbs free energy of fluoride formation [32]. The distribution of main alloying elements with depth is obtained using EPMA line scans to evaluate the corrosion depth quantitatively in unirradiated and irradiated GH3535 alloys with 0%, 3%, and 10% tensile strain after corrosion (for short, UC-0, UC-3, UC-10, IC-1, IC-3, IC-10) as seen in Fig. 2. A sensibly decreased Cr content in the near-surface region was observed in all samples. The variation of Cr in three different regions on each sample are shown in Fig. 2. For all the un-irradiated samples, the average thickness of the Cr-depletion layer had no apparent distinctions as the applied strain increased. It can be ascribed to significant stress relaxation in the early stage of thermal exposure during 750 ℃ molten salt corrosion. The deformation formed in the sample after stress relaxation is insufficient to affect the diffusion rate of Cr [33, 34]. The Cr depletion depth of the IC-0 sample was 3.15 μm, which slightly increased than that of the UC-0 sample (2.75 μm), showing that irradiation promotes the corrosion of the alloy, and this value was 3.62 μm and 3.82 μm for IC-3 and IC-10 samples, respectively. It is evident that the thickness of the Cr deposition layer in IC-10 sample increase by 1.07 μm compared to the UC-0 sample, indicating irradiation followed by 10% strain promotes the corrosion of the alloy.

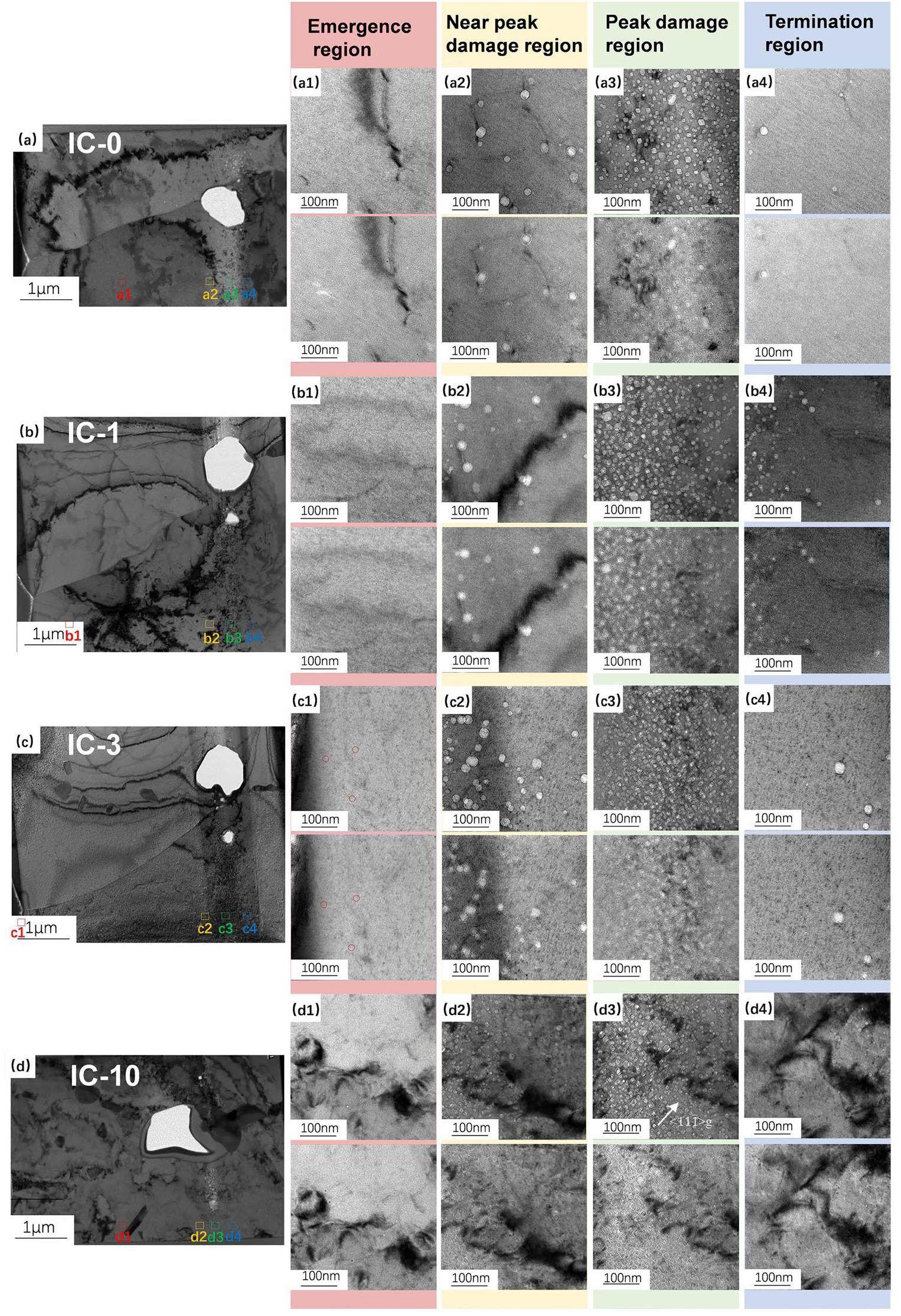

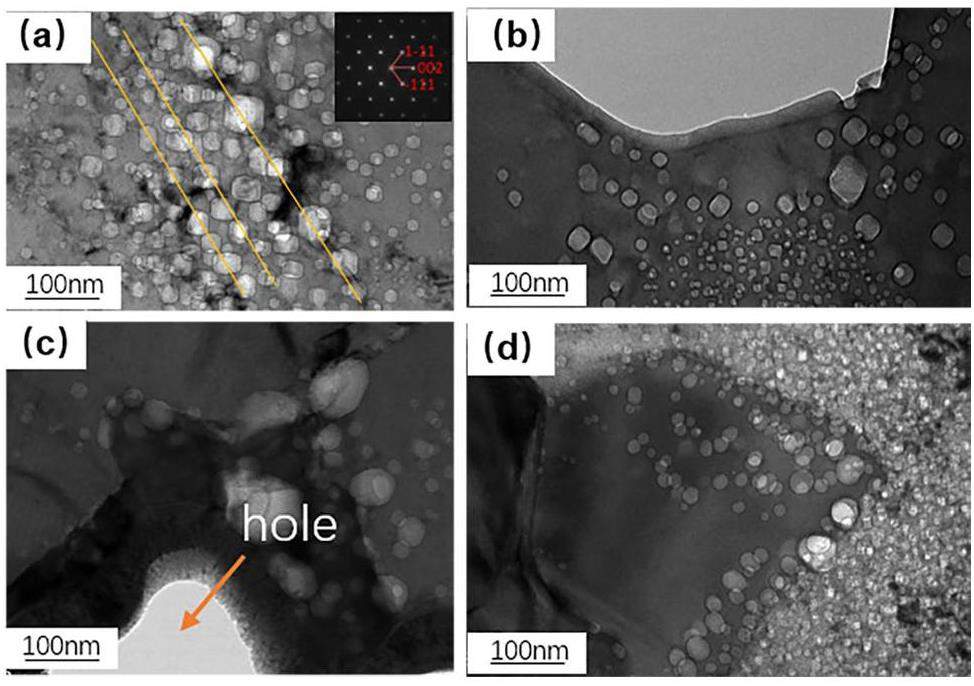

The microstructure evolution of helium-ion irradiated tensile samples was analyzed. Helium bubbles can be observed with the average size of 4.62 ± 0.64 nm and number density of 1.18×1023 /m3. No obvious variations in the mean size and density of helium bubbles with the increasing of plastic strain (see Supplementary material). Figures 3(a), (b), (c), and (d) show the cross-sectional TEM images of the irradiated GH3535 alloy followed by 0%, 1%, 3%, and 10% strain after corrosion (for short, IC-0, IC-1, IC-3, IC-10). It is obvious that a large hole was found at the peak damage region in IC-0 (Fig. 3a), IC-1(Fig. 3b), IC-3 (Fig. 3c), and IC-10 (Fig. 3d) samples, revealing that irradiation deteriorate molten salt corrosion. Figures 3 (a1-a4), (b1-b4), (c1-c4), and (d1-d4) show the helium bubble distribution in four representative regions of the IC-0, IC-1, IC-3, and IC-10 samples. In the beginning region (Fig. 3a1, b1, c1 and d1) where helium bubbles can be observed, the sizes of helium bubbles were small in all the four samples. The maximum size of helium bubbles emerges in the vicinity of the peak damage region, and these helium bubbles tend to grow along dislocations, as shown in the near peak damage region (Figs. 3a2, b2, c2, and d2). In the peak damage region, some helium bubbles have irregular shapes with quadrilaterals and polygons. In particular, helium bubbles are elongated along the

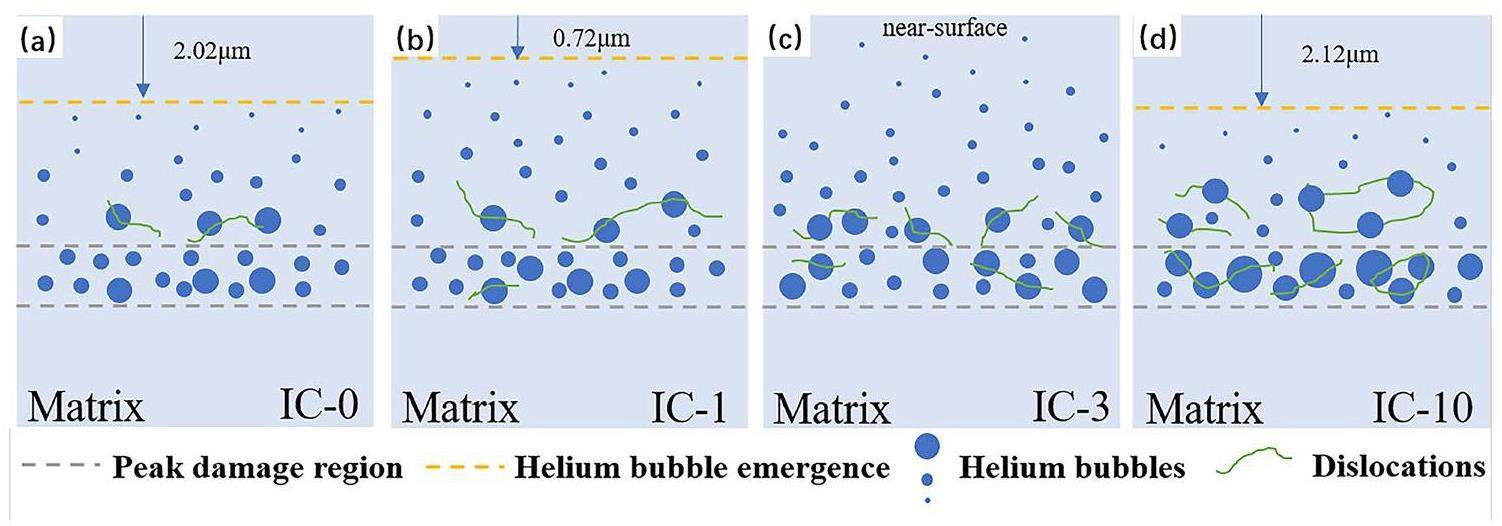

Helium bubbles in four typical regions are quantitatively analyzed for the irradiated alloys followed by different plastic strains. We calculate the depth at which helium bubbles begin to appear, the mean diameter of helium bubbles near and within the peak damage region, and the number densities of helium bubbles in the peak damage region, as shown in Table 1. The emergence depths of helium bubbles for all the samples (IC-0, IC-1, IC-3, IC-10) are less than that of the U-0 samples (3.41 μm). It is obvious that helium bubbles migrate toward the surface of the alloy. It is worth noting that helium bubbles move closer to the surface as the strain increases up to 3%, while they fall back for the IC-10 sample. The emergence depth of helium bubbles is similar between IC-10 and IC-0. In the near-peak damage region, the mean size of helium bubbles varies from 14.58± 6.79 μm for IC-0 to 19.97± 6.28 μm for IC-10, indicating a slight coarsening of the helium bubbles with increasing strain. In the peak damage region, the mean size of helium bubbles increases by more than 3 times, while the densities of helium bubbles decrease by an order of magnitude compared with those in the as-irradiated alloy, which can be attributed to the corrosion-induced oversaturated vacancies enhancing the migration of helium atoms [25]. In addition, there were no obvious differences in the average size and density of helium bubbles with increasing stress.

| Sample | IC-0 | IC-1 | IC-3 | IC-10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The depth at which helium bubbles begin to appear (μm) | 2.02 | 0.72 | near-surface | 2.12 |

| Helium bubbles mean diameter near the peak damage region (μm) | 14.58±6.79 | 17.10±6.80 | 18.35±6.07 | 19.97±6.28 |

| Helium bubbles mean diameter in the peak damage region (nm) | 10.1±2.83 | 12.86±3.47 | 12.9±2.69 | 13.88±3.63 |

| Helium bubbles densities in the peak damage region (m-3) | 4.74×1022 | 5.46×1022 | 5.2×1022 | 4.92×1022 |

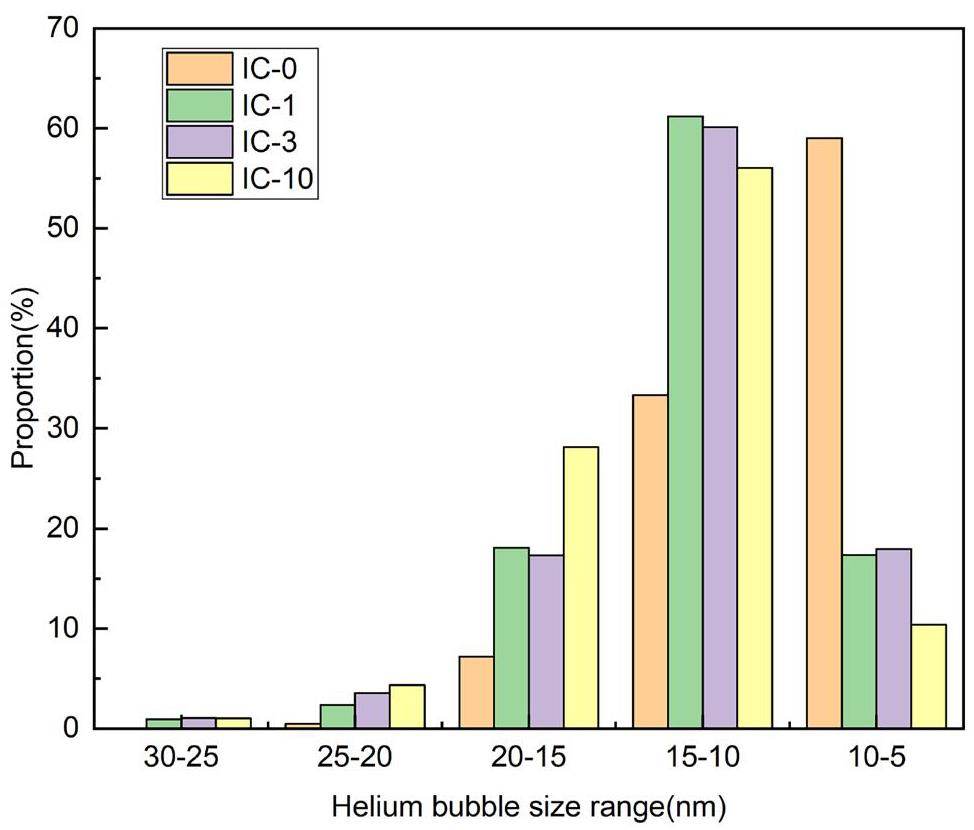

It can be seen in Fig. 3 that helium bubbles of peak damage region are not uniform in size after corrosion. Thus, we calculate the helium bubble size distribution of irradiated GH3535 alloy followed by different plastic strain after molten salt corrosion, as plotted in Fig. 4. Over 50% of the helium bubbles size are within the range of 5-10 nm for the IC-0 sample, while those are in the range of 10-15 nm for samples with applied strains. The proportion of small-sized helium bubbles (<10 nm) is higher for the IC-0 alloy (59.01%) than for the specimens after tensile deformation (17.38% for IC-1, 17.95% for IC-3, and 10.40% for IC-10). In addition, the proportion of large-size helium bubbles (>15 nm) is 7.66% for IC-0, 21.43% for IC-1, 21.92% for IC-3, and 33.56% for IC-10, respectively. These results indicate that helium bubbles tend to grow after applying plastic strain, and suggests synergic effects of irradiation and strain on the molten salt corrosion.

Discussion

The synergistic effect of irradiation and tensile strain on molten salt corrosion of GH3535 alloy

Based on the above results, the coupling effect of irradiation and strain accelerates the molten salt corrosion of GH3535 alloy, which can be mainly manifested in two aspects. First, the thickness of the Cr depletion layer of IC-10 (3.82 μm) increased by 40% compared with the UC-0 alloy (2.75 μm). Second, holes appeared in the peak damage region of the irradiated and strained alloys, and the proportion of large-size helium bubbles in irradiated sample followed by 10% strain (33.56%) was 4.4 times that of the irradiated alloy without plastic deformation (7.66%).

The formation of the cavity in the irradiated and stretched alloy can be attributed to the growth of the helium bubbles [25, 26]. These holes can become the initial location of cracking, accelerating corrosion and reducing the lifetime of the alloy in the reactor. The size of helium bubbles near the cavity is more prone to coarsening (Fig. 5(b)), and when they encounter with each other, further rupture into cavities. In addition, helium bubbles were observed to grow along the interface of precipitates (Figs. 5(c) and (d)), which is due to their role as defect sink [35]. On the other hand, plastic strain further promotes the growth of helium bubbles. According to the “deformation and coalescence” mechanism [36], bubbles will perform coalescence via the elongation in the direction of tensile stress loading. In this study, there was no significant change in the average size and density of helium bubbles with plastic strain increasing. This may be due to the fact that the bubbles are too dense, thus the statistical data is not obvious. However, large-size helium bubbles meaningfully increased in the irradiated and stretched samples after molten salt corrosion, possibly owing to the deformation and merging of some helium bubbles after tensile stress loading, and they grew rapidly after corrosion. Moreover, tensile strain introduces dislocation lines and networks, which also promote helium bubbles growth, as shown in Fig. 5(a).

Unexpected outward migration behavior of helium bubbles under different tensile strain in molten salt environment

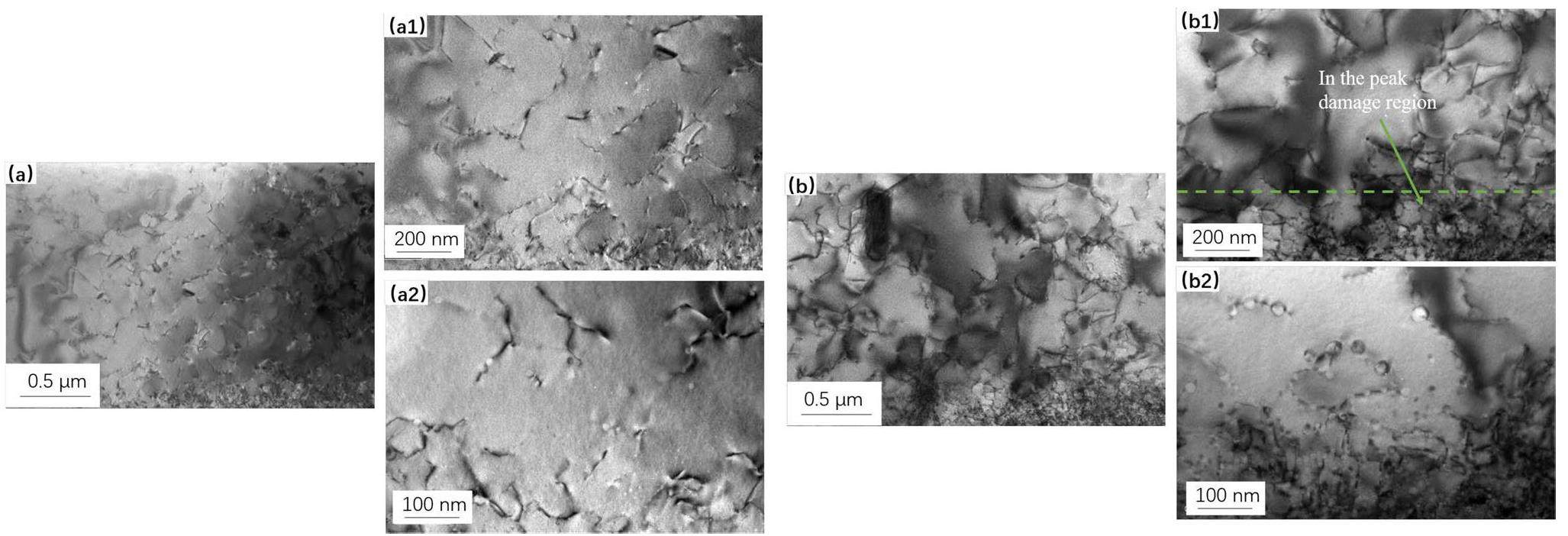

The growth and evolution of helium bubbles during thermal annealing can be explained by migration and coalescence (MC) and Ostwald ripening (OR) mechanisms [35]. Both mechanisms are dominated by oversaturated vacancies [37, 38]. In a high-temperature molten salt environment, the dissolution of alloy atoms leads to the formation of vacancies, which may promote the growth of helium bubbles and facilitate the outward migration of bubbles [25]. The migration of helium bubbles can provide more channels for the molten salt to diffuse into the alloy to accelerate the depletion of Cr, which are responsible for irradiation intensifying corrosion. In this study, an unexpected outward migration behavior of helium bubbles under different tensile strains was observed. Figure 6 shows the migration behavior of helium bubbles under different tensile strains in a molten salt environment. Helium bubbles move closer to the surface as the strain increases up to 3%, while the migration depth is less for the IC-10 sample than that of IC-3. Although helium bubbles slightly diffuse outward in the irradiated GH3535 alloy followed by 10% strain in the molten salt environment, this diffusion effect is limited. As we know, with the increasing of tensile strain, more dislocations and their network are introduced into the alloys. On one hand, they act as a fast diffusion channel to promote the Cr element diffusion, thus providing more vacancies combining with the helium atoms to enhance the outward migration of helium bubbles. On the other hand, in-situ TEM experiments on the evolution of helium bubbles have shown that helium bubbles would be pinned by dislocations to inhibit their long-range diffusion [39]. Moreover, it has been proven that high density dislocations can impact the nucleation and growth of He bubbles in the GH3535 alloy at high temperatures [40]. Thus, with the increasing tensile strain up to 10%, the tangled dislocations and their network pinned the diffusion of helium bubbles and decelerated their outward migration. As shown in Fig. 7, after corrosion, compared with the irradiated GH3535 alloy followed by 3% strain, there are still abundant dislocation networks and cells in irradiated GH3535 alloy followed by 10% strain, which is more obvious in the peak damage region, and helium bubbles migrate to these dislocations for coarsening. This is consistent with the result that large-size helium bubbles were meaningfully increased in the irradiated GH3535 alloy followed by 10% strain after molten salt corrosion.

Conclusion

The corrosion behavior of an irradiated and stretched GH3535 alloy in molten FLiNaK salt at 750 ℃ was investigated using TEM and EPMA to clarify the synergistic effects of irradiation and tensile deformation on corrosion. The conclusions are as follows:

(1) The thickness of the Cr depletion layers of the only corroded sample is 2.75 μm, of which is 3.82 μm, increased by 40%, for the alloy after helium ion irradiation followed by 10% plastic deformation.

(2) After molten salt corrosion, the proportion of large-size helium bubbles (>15 μm) increased with the applied strain.

(3) An unexpected outward migration behavior of helium bubbles under different plastic deformation was observed. Helium bubbles migrated closer to the surface as the strain increased up to 3%, while the migration depth declined when the strain reached 10%.

(4) The different evolution of helium bubbles is related to the competition between corrosion induced dissolution of elements, which provide abundant vacancies to feed the growth of helium bubbles, along with the pinning of dislocation on helium bubbles to inhibit their growth.

Previous studies have revealed that outward migration of helium bubbles promotes the corrosion of the GH3535 alloy in a high-temperature molten salt environment. The current results clearly emphasize the crucial role of plastic deformation. Although in this study the mechanical loading is not constant extension rate tensile, to simulate the working conditions in reactors, it still sheds light on the evolution of corrosion behavior of GH3535 in the complex environment combining irradiation, corrosion and local deformation. In future work, we will further explore and elucidate whether there is IASCC in structural materials of MSRs and the governing mechanisms.

Materials challenges in nuclear energy

. Acta Mater. 61, 735-758 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTAMAT.2012.11.004Materials challenges for generation IV nuclear energy systems

. Nucl. Technol. 162, 342-357 (2008). https://doi.org/10.13182/NT08-A3961Structural materials for Gen-IV nuclear reactors: Challenges and opportunities

. J. Nucl. Mater. 383, 189-195 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNUCMAT.2008.08.044Review on synergistic damage effect of irradiation and corrosion on reactor structural alloys

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 57 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01415-3Complexity of segregation behavior at localized deformation sites formed while in service in a 316 stainless steel baffle-former bolt

. Scr. Mater. 255,Insights into the stress corrosion cracking resistance of a selective laser melted 304L stainless steel in high-temperature hydrogenated water

. Acta Mater. 244,The role of grain boundary microchemistry in irradiation-assisted stress corrosion cracking of a Fe-13Cr-15Ni alloy

. Acta Mater. 138, 61-71 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTAMAT.2017.07.042A high-resolution characterization of irradiation-assisted stress corrosion cracking of proton-irradiated 316L stainless steel in simulated pressurized water reactor primary water

. Corros. Sci. 199,Progress in corrosion resistant materials for supercritical water reactors

. Corros. Sci. 51, 2508-2523 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORSCI.2009.07.007Environmental degradation of structural materials in liquid lead- and lead-bismuth eutectic-cooled reactors

. Prog. Mater. Sci. 126,Molten salt reactors: A new beginning for an old idea

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 240, 1644-1656 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NUCENGDES.2009.12.033The molten salt reactor (MSR) in generation IV: Overview and perspectives

. Prog. Nucl. Energy 77, 308-319 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PNUCENE.2014.02.014Molten salts and nuclear energy production

. J. Nucl. Mater. 360, 1-5 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNUCMAT.2006.08.017Micro/nano mechanical properties differences of shallow irradiation damage layer revealed by a combined experimental and MD study

. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 889,The effect of stress state and He concentration on the dislocation loop evolution in Ni superalloy irradiated by Ni+ & He+ dual-beam ions: In-situ TEM observation and MD simulations

. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 212, 77-88 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMST.2024.06.015A special coarsening mechanism for intergranular helium bubbles upon heating: A combined experimental and numerical study

. Scr. Mater. 147, 93-97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCRIPTAMAT.2018.01.006The high-temperature corrosion of Hastelloy N alloy (UNS N10003) in molten fluoride salts analysed by STXM, XAS, XRD, SEM, EPMA, TEM/EDS

. Corros. Sci. 106, 249-259 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.716Effect of grain refinement on the corrosion of Ni-Cr alloys in molten (Li,Na,K)F

. Corros. Sci. 109, 43-49 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORSCI.2016.03.027The tensile behavior of GH3535 superalloy at elevated temperature

. Mater. Chem. Phys. 182, 22-31 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MATCHEMPHYS.2016.07.001Effect of Long-term Thermal Exposure on Microstructure and Stress Rupture Properties of GH3535 Superalloy

. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 269-279 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMST.2014.07.021In-situ TEM investigation on the evolution of He bubbles and dislocation loops in Ni-based alloy irradiated by H2+ & H+ dual-beam ions

. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 138, 36-49 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMST.2022.07.054Structural materials for fission & fusion energy

. Mater. Today 12, 12-19 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-7021(09)70294-9Effects of compositional complexity on the ion-irradiation induced swelling and hardening in Ni-containing equiatomic alloys

. Scr. Mater. 119, 65-70 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCRIPTAMAT.2016.03.030Effects of bubbles on high-temperature corrosion of helium ion-irradiated Ni-based alloy in fluoride molten salt

. Corros. Sci. 125, 184-193 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORSCI.2017.06.027Corrosion-driven outward migration and growth of helium bubbles in a nickel-based alloy in high-temperature molten salt environment

. Corros. Sci. 153, 47-52 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CORSCI.2019.03.026Effects of He ion irradiation on the corrosion performance of alloy GH3535 welded joint in molten FLiNaK

. Corros. Sci. 146, 172-178 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.10.038Nanobubble fragmentation and bubble-free-channel shear localization in helium-irradiated submicron-sized copper

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 117 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.215501In situ micro tensile testing of He+2 ion irradiated and implanted single crystal nickel film

. Acta Mater. 100, 147-154 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.215501In-situ study of initiation and extension of nano-thick defect-free channels in irradiated nickel

. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 58, 114-119 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.03.057Stress sensitivity origin of extended defects production under coupled irradiation and mechanical loading

. Acta Mater. 248,Synergistic effect of irradiation and molten salt corrosion: Acceleration or deceleration?

. Corros. Sci. 185,Materials corrosion in molten LiF–NaF–KF salt

. J. Fluor. Chem. 130, 67-73 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFLUCHEM.2008.05.008Impact of dislocations and dislocation substructures on molten salt corrosion of alloys under plasticity-imparting conditions

. Corros. Sci. 176,Effect of SO22− ion impurity on stress corrosion behavior of Ni-16Mo-7Cr alloy in FLiNaK salt

. J. Nucl. Mater. 547,Helium accumulation in metals during irradiation–where do we stand?

J. Nucl. Mater. 323, 229-242 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNUCMAT.2003.09.001Coalescence mechanism of helium bubble during tensile deformation revealed by in situ small-angle X-ray scattering

. Scr. Mater. 158, 121-125 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCRIPTAMAT.2018.08.050Density and pressure of helium in small bubbles in metals

. J. Nucl. Mater. 111–112, 674-680 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3115(82)90288-4The formation of helium bubbles near the surface and in the bulk in nickel during post-implantation annealing

. J. Nucl. Mater. 170, 31-38 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3115(90)90323-FIn situ TEM observation of the evolution of helium bubbles in Hastelloy N alloy during annealing

. J. Nucl. Mater. 537,Effect of helium bubbles on the irradiation hardening of GH3535 welded joints at 650 ℃

. J. Nucl. Mater. 557,The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01769-2.