Introduction

Molten salt reactors (MSRs) are the only liquid fuel reactors among the Generation IV nuclear reactors, where the fissile and fertile fluorides (i.e., UF4, ThF4, and PuF3) are dissolved into the molten fluoride salt [1-3]. MSRs have received increasing attention worldwide owing to their significant advantages, such as good neutron economy, less nuclear waste, no water cooling, online post-processing of fission products, and low pressure at high temperature [4-8]. Molten fluoride salt is used as a nuclear fuel and heat transfer fluid medium because of its good neutron properties and excellent thermophysical properties, which play a critical role in the design of nuclear cores, thermal hydraulic calculations, nuclear reactor safety analysis, and the entire operation of nuclear reactors [9-13]. Relevant fluoride salts, which are essential for the design, research, and development of heat transfer media for MSRs must be explored thoroughly.

Molten BeF2-based salt is considered one of the most promising heat transfer media and nuclear fuel salt carriers for MSRs due to its favorable thermal neutron-capture cross-section (<1 barn) and thermophysical properties [14-17]. LiF-BeF2 is the classic coolant and nuclear fuel medium for the MSRs at Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics in China [18] and Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in the U.S. [19]. The LiF-BeF2 system has been extensively investigated by many researchers. The phase diagram information of the LiF-BeF2 system was first determined through thermal analysis and thermal gradient quenching by Roy et al. [20], and Moore et al. [21]. Later, the liquidus of the LiF-BeF2 phase diagram with a 0.12–0.58 mole fraction of BeF2 was again measured through the electromotive force method by Romberger et al. [22]. The thermochemical properties (i.e., the activity coefficient [23] and mixing enthalpy of the liquid phase [24]) of the LiF-BeF2 system were experimentally investigated using the electromotive force and single-unit microcalorimeter methods, respectively. The LiF-BeF2 system was first optimized using Redlich-Kister polynomials by Meer et al. [25], and the thermophysical properties (i.e., the melting point [26], specific heat capacity [17, 27], density [17, 28], viscosity [28-31], vapor pressure [32], thermal conductivity [10], and local structure [33-36]) have been thoroughly studied by performing experimental measurements and theoretical calculations. Compared with the LiF-BeF2 system, the NaF-BeF2 system has not been reported on as thoroughly. The phase diagram of the NaF-BeF2 system was measured based on the differential thermal analysis techniques, high-temperature X-ray diffraction, and the quenching method by Roy et al. [37]. The thermodynamic database of the NaF-BeF2 system was later built based on the substitutional solution model by Wu et al. [38]. Only limited experimental data regarding the properties of NaF-BeF2 (i.e., the melting point [10], density [39], viscosity [39], specific heat capacity [17], vapor pressure [40], activity coefficient [41], and local structure [42]) have been reported. The thermophysical properties of the NaF-BeF2 system were solely calculated using first-principles molecular dynamics by Liu et al. [43]. For the KF-BeF2 system, limited thermodynamic property information has been obtained [17, 21, 44, 45]. Only the phase equilibria information [21, 46] and a few thermophysical properties [39] for the RbF-BeF2 system have been experimentally determined, and only the experimental phase diagram of the CsF-BeF2 system has been determined by thermal analysis [47]. Until now, little other experimental or theoretical information about the AF-BeF2 (A = K, Rb, and Cs) system has been available, although this information is foundational for the design and operation of processes utilizing molten fluoride salts. Studying the thermodynamic characteristics of the AF-BeF2 (A = K, Rb, and Cs) system only through experimental measurements is also challenging owing to the difficulty and uncertainty of high-temperature experiments with highly toxic BeF2. Calculation of phase diagrams (CALPHAD) is one of the most effective techniques for studying the phase equilibria behavior of multi-component systems based on minimal experimental data. Due to its high accuracy and universality, ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) is a powerful tool for investigating the interionic forces, local structures, and physio-chemical properties of multi-component systems and has been successfully applied to the LiF-BeF2 [48-50], NaF-BeF2 [43, 51], and KF-NaF-AlF3 [52] systems, among others. In the present work, phase diagrams calculations and AIMD were employed to investigate the thermodynamic and kinetics characteristics of the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system.

The thermodynamic calculations for the KF-BeF2, RbF-BeF2, CsF-BeF2, KF-CsF, and RbF-CsF systems were performed using the CALPHAD technique based on experimental data and theoretically calculated values. A substitutional solution model was used to depict the liquid and solid solution phases, and compound energy formalism was employed to describe the intermediate phases, i.e., ABeF3, A2BeF4, A3BeF5, and ABe2F5 (A = K, Rb, and Cs). The results showed that the thermodynamically calculated values for the KF-BeF2, RbF-BeF2, CsF-BeF2, KF-CsF, and RbF-CsF systems agreed well with the experimental data. Finally, a set of self-consistent and reliable thermodynamic databases was obtained. Additionally, the liquidus projection and invariant points of the corresponding ternary systems of the KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system were calculated. Furthermore, the melting temperatures with the corresponding compositions, radial distribution functions (RDFs), coordination numbers (CNs), angular distribution functions (ADFs), and diffusion coefficients of the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system were calculated using AIMD. The results showed that the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 (3.50-28.92-21.78-45.80 mol% or 1.80-35.42-52.40-10.38 mol%) system is one of the most promising candidate coolants for MSRs in terms of thermodynamics and kinetics. The thermodynamic parameters of the KF-BeF2, RbF-BeF2, CsF-BeF2, KF-CsF, and RbF-CsF systems were firstly built using the CALPHAD technique. The kinetic characteristics of the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 (3.50-28.92-21.78-45.80 mol% or 1.80-35.42-52.40-10.38 mol%) system were also first obtained in this study using AIMD. These are important fundamentals for thoroughly exploring heat transfer media and nuclear fuel carriers for MSRs. This work provides guidelines for the screening and optimization of molten salts in the nuclear energy field.

Literature evaluation

KF-BeF2 system

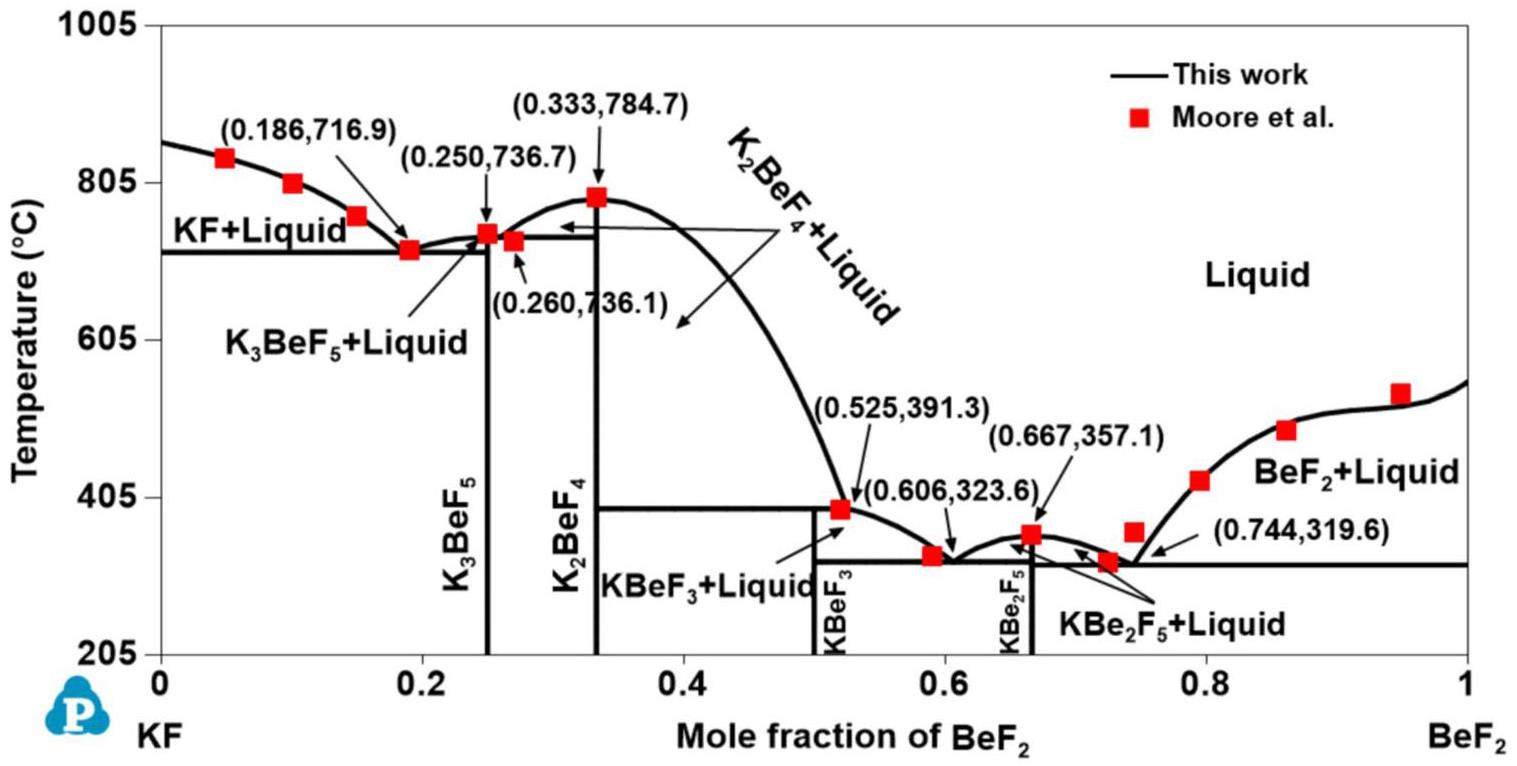

The phase equilibrium information of the KF-BeF2 system has been reported by three groups of investigators using thermal analysis. The experimental phase diagram of the KF-BeF2 system was first established by Borzenkova et al. [44]. Four intermediate phases—K3BeF5, K2BeF4, KBeF3, and KBe2F5—were detected in the KF-BeF2 system, where only three compounds—K3BeF5, K2BeF4, and KBeF3—were stable from room temperature to the melting temperature, whereas KBe2F5 was decomposed into KBeF3 and BeF2 at 278.0 °C. Afterwards, the KF-BeF2 system was experimentally determined by Moore et al. [21] at ORNL. The four compounds were again discovered, where K3BeF5, K2BeF4, and KBe2F5 were melted congruently at 740.0 °C, 787.0 °C and 353.0 °C, whereas KBeF3 was melted incongruently at 405.5 °C; these findings are substantially different from those of Borzenkova et al. [44]. Thus, four eutectic reactions (

RbF-BeF2 system

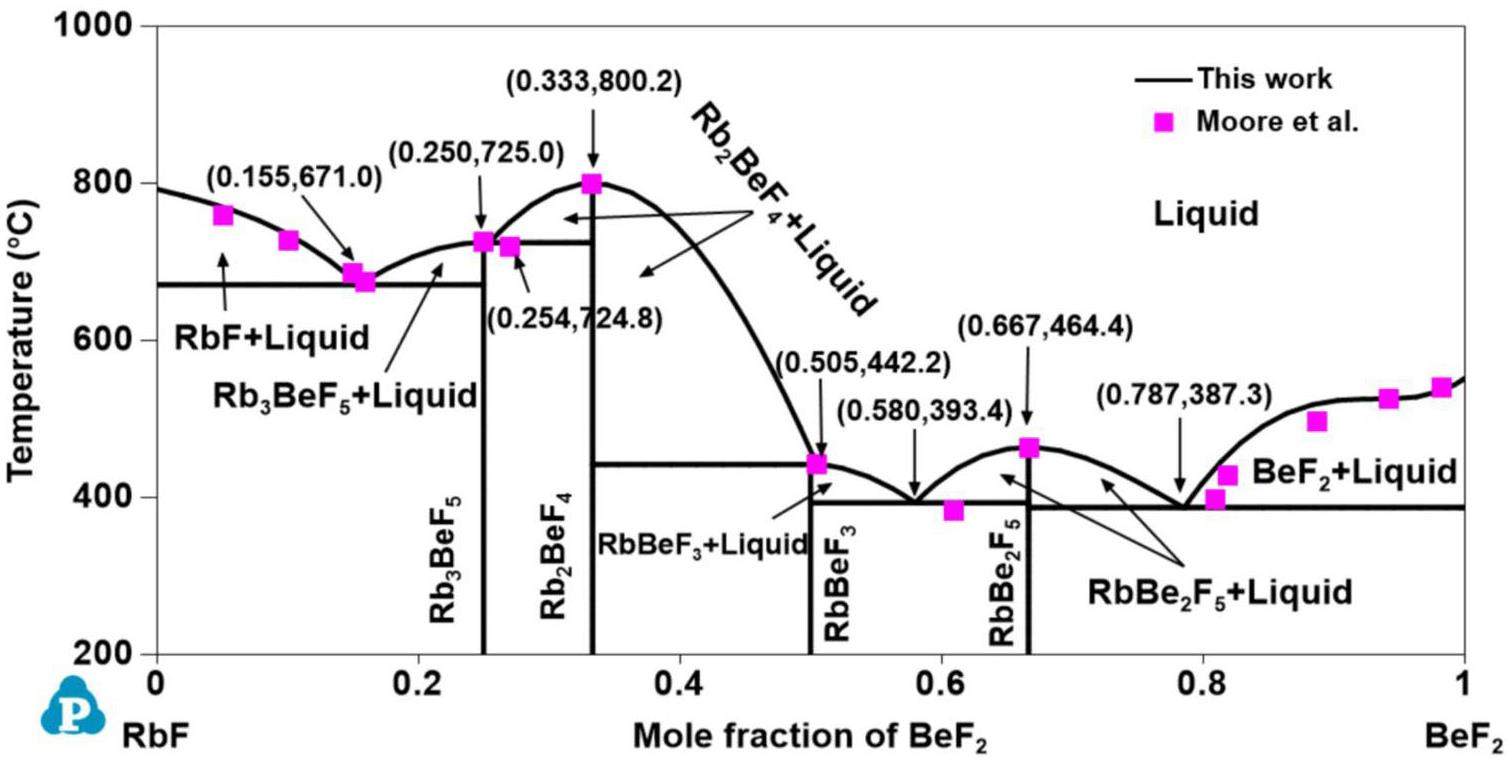

A phase diagram of the RbF-BeF2 system was constructed by two groups of investigators using thermal analysis. Grebenshchikov [46] first established the entire phase diagram of the RbF-BeF2 system, in which four intermediate phases—Rb2BeF4, Rb3Be2F7, RbBeF3 and RbBe2F5—were detected. Three compounds—Rb2BeF4, RbBeF3, and RbBe2F5—were stable and congruently melted separately at 792.0 °C, 464.0 °C, and 451.0 °C, whereas Rb3Be2F7 was unstable and decomposed to Rb2BeF4 and RbBeF3 when the temperature was higher than 423.5 °C. In addition, Rb2BeF4 and RbBe2F5 are not simple stoichiometric compounds and have a certain solid solubility. Eventually, four eutectic reactions (

CsF-BeF2 system

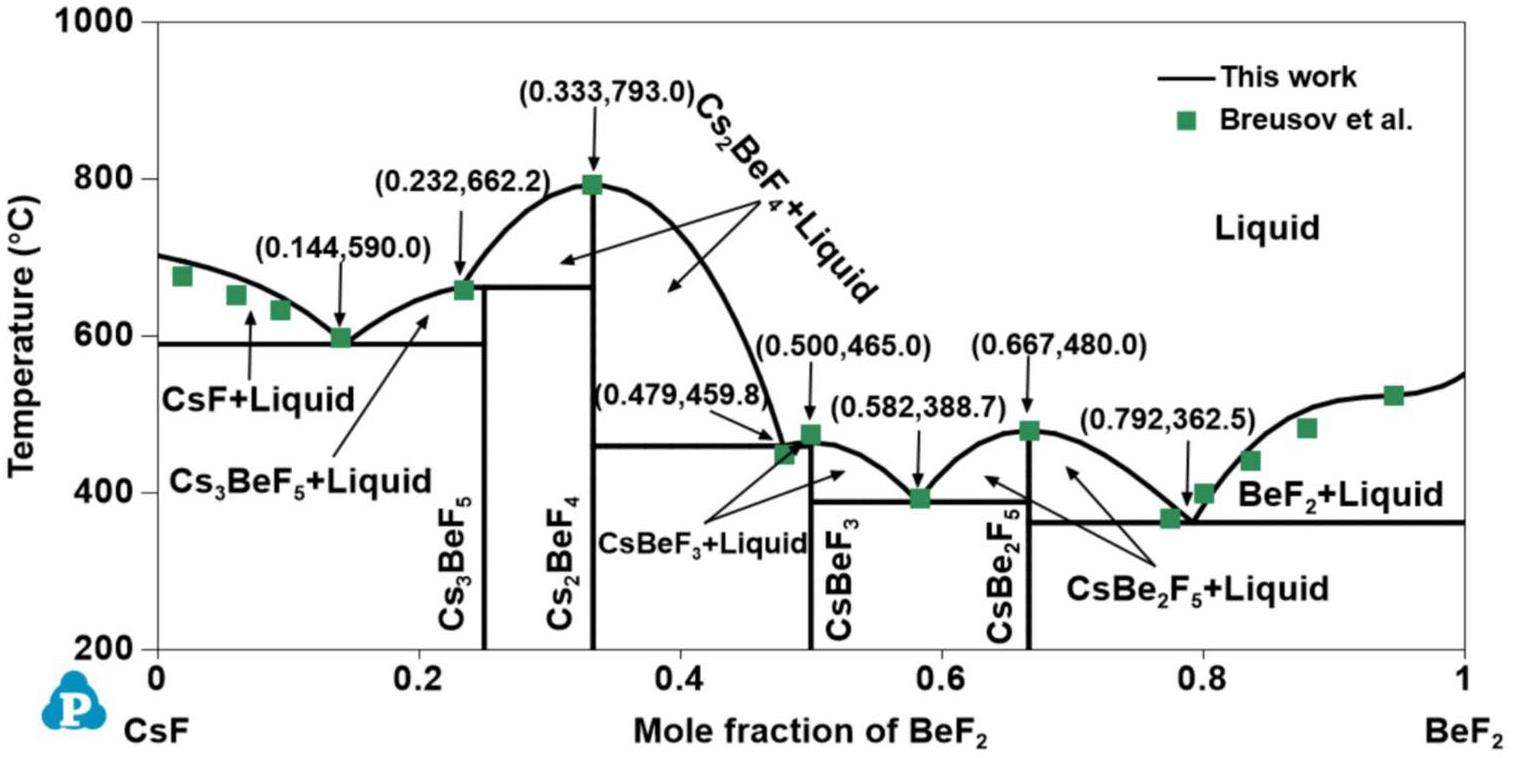

Only Breusov et al. [47] reported the phase equilibrium information of the CsF-BeF2 system using thermal analysis. The CsF-BeF2 system contains four intermediate compounds—Cs3BeF5, Cs2BeF4, CsBeF3 and CsBe2F5—where Cs2BeF4, CsBeF3, and CsBe2F5 were discovered to melt congruently at 793.0 °C, 475.0 °C, and 480.0 °C, respectively, but Cs3BeF5 melted incongruently at 659.0 °C. Four eutectic reactions (

KF-CsF system

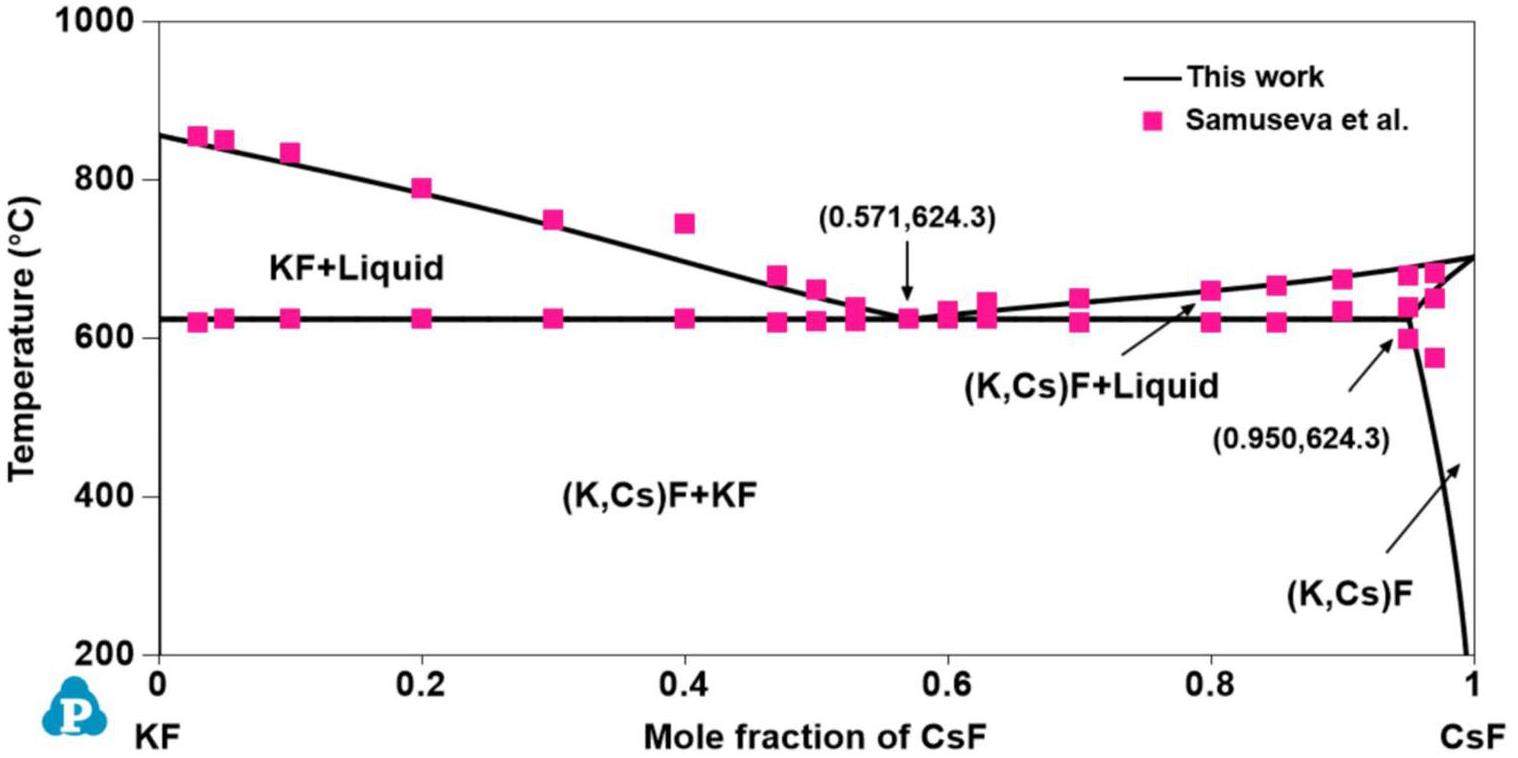

The phase diagram of the KF-CsF system was solely obtained by Samuseva et al. [53] through thermal analysis. This system is eutectic with one eutectic point located at 625.0 °C and 0.570 mol CsF. In addition, the limited solid solubility of KF in CsF is 0.15 mol at 625.0 °C. To date, few thermochemical studies of the KF-CsF system have been reported. A substitutional solution model was used to optimize the KF-CsF system based on experimental data from Samuseva et al. [53].

RbF-CsF system

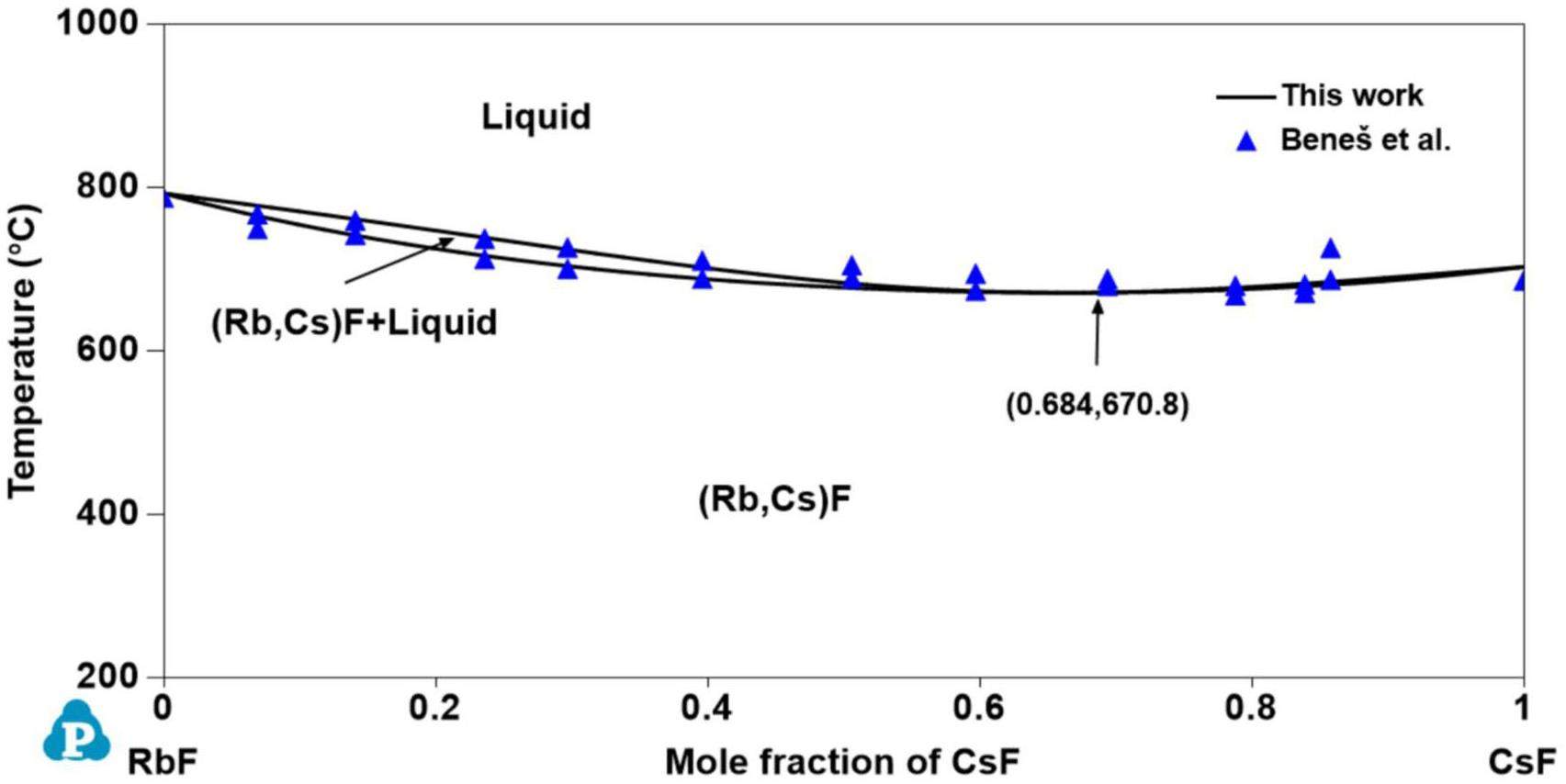

The phase diagram of the RbF-CsF system was investigated by Samuseva et al. [53] and Beneš et al. [54] using thermal analysis. The phase diagram reported by Samuseva et al. [53] shows a temperature minimum for the solidus without a corresponding minimum for the liquidus, which violates the phase rule. The liquidus of the RbF-CsF system was optimized by Sangster and Pelton [55] based on the liquidus experimental data of Samuseva et al. However, there was a significant deviation between the calculated phase diagram and liquidus experimental data obtained by Samuseva et al.

Subsequently, new measurements of the solidus and liquidus equilibria of the RbF-CsF system were obtained by Beneš et al. [54]. The phase diagram of the RbF-CsF system was first constructed using a quasi-chemical model based on the measured experimental data, where the calculated phase diagram agreed well with the experimental values. In this study, the RbF-CsF system was calculated using the substitutional solution model to maintain the consistency of the model. The experimental data from Beneš et al. were used to optimize the RbF-CsF system in the present work.

KF-RbF system

The KF-RbF system is isomorphous with a minimum point in the liquidus curve, which was systematically evaluated and optimized by Yin et al. [56]. The thermodynamic parameters obtained in that study were directly adopted in the present work.

Sub-ternary systems

Little relevant information has been reported to date for the ternary KF-RbF-BeF2, KF-CsF-BeF2, RbF-CsF-BeF2, and KF-RbF-CsF systems. These ternary systems were investigated in this study based on the thermodynamic parameters of the binary systems using model extrapolation.

Methods

Thermodynamic optimization

The PanOptimizer module included in the PANDAT software, which is a C/C++ software package for optimizing thermodynamics and thermophysical properties, was used to optimize the thermodynamic parameters. The weighted least-squares technique was adopted during the optimization process, and a trial-and-error method was used to regulate the optimization weight factor until the optimized value agreed well with the experimental phase equilibrium data and the theoretically calculated value.

Thermodynamic model

Pure component

The Gibbs energy function of the pure component is described as follows, and the corresponding coefficients of the pure component are listed in Table 1:

| Compound | Gibbs energy (J) | Temp. (K) |

|---|---|---|

| KF (Solid) | –581,701.002+245.661T–45.982ln(T) –0.007T2 | 298.15–2000 |

| KF (Liquid) | –567,937.997+372.694T–66.944Tln(T) | 298.15–2000 |

| RbF (Solid) | –563,090.817+158.256T–33.330Tln(T) –0.019T2–251,040.000T–1 | 298.15–1500 |

| –558,571.051+313.921T–58.994Tln(T) | 1500–1663 | |

| RbF (Liquid) | –546,097.480+300.480T–58.994Tln(T) | 298.15–1066 |

| –297,259.229–607.417T+47.292Tln(T) –0.002T2–73,360,164.000T–1 | 1066–1200 | |

| –544,409.532+298.957T–58.994Tln(T) | 1200–1663 | |

| CsF (Solid) | –569,380.712+229.686T–46.685Tln(T) –0.009T2 | 298.15–2000 |

| CsF (Liquid) | –565,929.140+405.902T–74.057Tln(T) | 298.15–2000 |

| BeF2 (Solid) | –1,041,405.769+271.945T–47.363Tln(T) –0.017T2 | 298.15–1300 |

| –1,029,550.268+331.677T–60.000Tln (T) | 1300–1301 | |

| BeF2 (Liquid) | –848,170.113–1703.462T+188.684Tln(T) –1,415,912.346T–1-5.801T1.5+26,373.417T0.5–74,606.149ln(T) | 298.15–2000 |

| –990,282.352+304.240T–60.000Tln(T) –0.010T2 | 2000–2001 |

Solution phase

The solution phase, that is, the liquid phase of the AF-BeF2 (A = K, Rb, and Cs) and A′F-CsF (A′ = K and Rb) systems, and the solid solution phase of the A′F-CsF (A′ = K and Rb) system, were thermodynamically described using the substitutional solution model, where the Gibbs free energy is expressed as follows:

Intermediate phase

The intermediate phases, that is, KBeF3, K2BeF4, K3BeF5, KBe2F5, RbBeF3, Rb2BeF4, Rb3BeF5, RbBe2F5, CsBeF3, Cs2BeF4, Cs3BeF5, and CsBe2F5, were thermodynamically described by the compound energy formalism, in which the Gibbs free energy is expressed as follows:

| Compd. | Etot (eV/atom) | Etot (kJ/mol) | Compd. | Etot (eV/atom) | Etot (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF | –5.822 | –560.775 | RbBeF3 | –16.745 | –1612.878 |

| RbF | –5.710 | –549.987 | Rb2BeF4 | –22.911 | –2206.787 |

| CsF | –5.662 | –545.364 | Rb3BeF5 | –28.620 | –2756.678 |

| BeF2 | –10.545 | –1015.694 | RbBe2F5 | –27.320 | –2631.462 |

| KBeF3 | –16.780 | –1616.250 | CsBeF3 | –16.825 | –1620.584 |

| K2BeF4 | –23.016 | –2216.901 | Cs2BeF4 | –22.932 | –2208.810 |

| K3BeF5 | –28.836 | –2777.483 | Cs3BeF5 | –28.593 | –2754.078 |

| KBe2F5 | –27.328 | –2632.233 | CsBe2F5 | –27.416 | –2640.709 |

Theoretical prediction of formation enthalpy

The formation enthalpies of the intermediate compounds ABeF3, A2BeF4, A3BeF5, and ABe2F5 (A = K, Rb, and Cs) were predicted based on the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), which is a high-throughput database includess many DFT energies of compounds. The formation enthalpy was used as the initial value to optimize the sub-binary systems of the KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system. The relevant calculated equations of the formation enthalpy are as follows based on the DFT single-point energy of the corresponding compounds:

AIMD

AIMD simulations were used to investigate the structure and properties of KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 systems with two different proportions (i.e., 3.50-28.92-21.78-45.80 mol% and 1.80-35.42-52.40-10.38 mol%), which are denoted as Mixtures 1 and 2, respectively, in the following sections. The initial simulation systems for the molten salts were constructed using a random insertion method, based on the densities predicted in the previous section. Mixtures 1 and 2 consisted of 140 atoms (2 K, 17 Rb, 12 Cs, 26 Be, and 83 F) and 118 atoms (1 K, 20 Rb, 29 Cs, 6 Be, and 62 F) atoms, respectively. Because the temperature has little effect on the structure of molten salts [58], only the 650 °C was investigated in this study.

AIMD based on DFT was performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package [59-62]. The exchange-correlation energy was described using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional of the generalized gradient approximation [63, 64]. The electron–ion core interactions were described by the projector-augmented plane-wave [65] method, and an energy cutoff of 600 eV for the plane-wave expansion of the wave functions was used. The Г point was chosen to sample the Brillouin zone [66]. A time step of 1.0 fs and a simulation temperature of 650 °C were used for all AIMD simulations, and the convergence criterion for the total energy was set at 10–5 eV.

The simulation process was as follows. First, 5 ps simulations for the two systems were conducted in an NPT ensemble with a Langevin thermostat to optimize the cell volumes using the method of Parrinello and Rahman [67, 68]. The corresponding equilibrium volumes were then obtained from the average of the last 3000 steps. Finally, 15 ps simulations for the two systems based on the equilibrium volumes were performed in an NVT ensemble with a Nosé thermostat [69, 70]. The systems reached equilibrium within 2 ps, and the structures and properties of the molten salt systems were obtained by analyzing the last 10,000 steps of the simulation.

The partial RDF is important for describing the atomic configuration in liquid systems and is defined as the probability of finding another atom at a distance

Results and discussion

Binary system

All phase diagrams were plotted using the PanPhaseDiagram module of the PANDAT software based on the optimized thermodynamic parameters listed in Table 3. The calculated phase diagrams will be discussed in the following section. The optimized formation enthalpies of the intermediate compounds from the sub-binary systems of the KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system and the calculated values from the OQMD are shown in Table 4. The calculated formation enthalpy agrees with most values from the OQMD, although some deviation between them exists owing to the different temperatures used (i.e., the values in the OQMD were obtained at 0 K, and the present optimized data were acquired at 298.15 K). Table 5 compares the calculated values of the key invariant points with the experimental data of the sub-binary systems of the KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system.

| Systems | Phases | Models | Thermodynamic Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| KF-BeF2 | Liquid | (KF, BeF2)1.0 | |

| K3BeF5 | (KF)3.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| K2BeF4 | (KF)2.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| KBeF3 | (KF)1.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| KBe2F5 | (KF)1.0(BeF2)2.0 | ||

| RbF-BeF2 | Liquid | (RbF, BeF2)1.0 | |

| Rb3BeF5 | (RbF)3.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| Rb2BeF4 | (RbF)2.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| RbBeF3 | (RbF)1.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| RbBe2F5 | (RbF)1.0(BeF2)2.0 | ||

| CsF-BeF2 | Liquid | (CsF, BeF2)1.0 | |

| Cs3BeF5 | (CsF)3.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| Cs2BeF4 | (CsF)2.0(BeF2)1.0 | ||

| CsBeF3 CsBe2F5 | (CsF)1.0(BeF2)1.0 (CsF)1.0(BeF2)2.0 | ||

| KF-CsF | Liquid | (KF, CsF)1.0 | |

| Halite | (KF, CsF)1.0 | ||

| RbF-CsF | Liquid | (RbF, CsF)1.0 |

| Binary system | Compounds | OQMD (kJ/mol) | This work (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KF-BeF2 | K3BeF5 | –39.780 | –67.039 |

| K2BeF4 | –79.656 | –40.000 | |

| KBeF3 | –79.464 | –34.842 | |

| KBe2F5 | –40.069 | –32.022 | |

| RbF-BeF2 | Rb3BeF5 | –47.197 | –90.700 |

| Rb2BeF4 | –91.119 | –61.540 | |

| RbBeF3 | –91.022 | –47.850 | |

| RbBe2F5 | –50.086 | –53.400 | |

| CsF-BeF2 | Cs3BeF5 | –59.526 | –98.868 |

| Cs2BeF4 | –102.388 | –70.000 | |

| CsBeF3 | –102.292 | –54.730 | |

| CsBe2F5 | –63.956 | –64.208 |

| System | Reaction | Invariant point | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF-BeF2 | T/°C | |||

| Liquid→K3BeF5+KF | 716.8 | 0.186 | [*] | |

| 720.0 | 0.190 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→K3BeF5 | 736.7 | 0.250 | [*] | |

| 740.0 | 0.250 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→K2BeF4+K3BeF5 | 736.1 | 0.260 | [*] | |

| 730.0 | 0.270 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→K2BeF4 | 784.7 | 0.333 | [*] | |

| 787.0 | 0.333 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid+K2BeF4→KBeF3 | 391.3 | 0.525 | [*] | |

| 390.0 | 0.520 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→KBeF3+KBe2F5 | 323.6 | 0.606 | [*] | |

| 330.0 | 0.590 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→KBe2F5 | 357.1 | 0.667 | [*] | |

| 358.0 | 0.667 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→BeF2+KBe2F5 | 319.6 | 0.744 | [*] | |

| 323.0 | 0.725 | Moore et al. | ||

| RbF-BeF2 | Reaction | T/°C | Reference | |

| Liquid→RbF+Rb3BeF5 | 671.0 | 0.155 | [*] | |

| 675.0 | 0.160 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→K3BeF5 | 725.0 | 0.250 | [*] | |

| 725.0 | 0.250 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→Rb2BeF4+Rb3BeF5 | 724.8 | 0.254 | [*] | |

| 720.0 | 0.270 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→Rb2BeF4 | 800.2 | 0.333 | [*] | |

| 800.0 | 0.333 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid+Rb2BeF4→RbBeF3 | 442.2 | 0.505 | [*] | |

| 442.0 | 0.505 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→RbBeF3+RbBe2F5 | 393.4 | 0.580 | [*] | |

| 383.0 | 0.610 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→RbBe2F5 | 464.4 | 0.667 | [*] | |

| 464.0 | 0.667 | Moore et al. | ||

| Liquid→BeF2+RbBe2F5 | 387.3 | 0.787 | [*] | |

| 397.0 | 0.810 | Moore et al. | ||

| CsF-BeF2 | Reaction | T/°C | Referencec | |

| Liquid→CsF+Cs3BeF 5 | 590.0 | 0.144 | [*] | |

| 598.0 | 0.140 | Breusov et al. | ||

| Liquid+Cs2BeF4→Cs3BeF5 | 662.2 | 0.232 | [*] | |

| 659.0 | 0.235 | Breusov et al. | ||

| Liquid→Cs2BeF4 | 793.0 | 0.333 | [*] | |

| 793.0 | 0.333 | Breusov et al. | ||

| L→CsBeF3+Cs2BeF4 | 459.8 | 0.479 | [*] | |

| 449.0 | 0.480 | Breusov et al. | ||

| Liquid→CsBeF3 | 465.0 | 0.500 | [*] | |

| 475.0 | 0.500 | Breusov et al. | ||

| Liquid→CsBeF3+CsBe2F5 | 388.7 | 0.582 | [*] | |

| 393.0 | 0.584 | Breusov et al. | ||

| Liquid→CsBe2F5 | 480.0 | 0.667 | [*] | |

| 480.0 | 0.667 | Breusov et al. | ||

| Liquid→BeF2+CsBe2F5 | 362.5 | 0.792 | [*] | |

| 367.0 | 0.775 | Breusov et al. | ||

| KF-CsF | Reaction | T/°C | Reference | |

| Liquid→KF+(K,Cs)F | 624.3 | 0.571 | [*] | |

| 625.0 | 0.570 | Samuseva et al. | ||

| Halite→(K,Cs)F#1+(K,Cs)F#2 | 624.3 | 0.950 | [*] | |

| 625.0 | 0.850 | Samuseva et al. | ||

| RbF-CsF | Reaction | T/°C | Reference | |

| Liquid→RbF+CsF | 670.8 | 0.684 | [*] | |

| 673.85 | 0.726 | Beneš et al. | ||

| 677.85 | 0.750 | Beneš et al. | ||

Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 show the calculated phase diagrams of the AF-BeF2 (A = K, Rb, and Cs) and A′F-CsF (A′ = K and Rb) systems with the corresponding experimental data [21, 47, 53, 54]. As clearly observed from Fig. 1, the calculated value of the KF-BeF2 system shows a high level of consistency with the experimental data from Moore et al., especially for the invariable point. For instance, the congruent melting temperatures of K3BeF5, K2BeF4, and KBe2F5 at 736.7 K, 784.7 K, and 357.1 K, respectively, are in excellent agreement with the experimental values of 740.0 K, 787.0 K, and 358.0 K, respectively [21]. As shown in Fig. 2, good agreement exists between the calculated values of the RbF-BeF2 system and the experimental data from Moore et al., except for some small deviation in the liquidus of the BeF2 end member. Similarly, the calculated melting temperatures of the intermediate phases Rb3BeF5, Rb2BeF4, and Rb2BeF4 at 725.0 K, 800.0 K, and 464.0 K, respectively, are nearly equal to the experimental values of 725.0 K, 800.2 K, and 464.4 K, respectively [21]. As shown in Fig. 3, the calculated phase diagram of the CsF-BeF2 system is in good agreement with the experimental data from Breusov et al. [47], although some slight deviation is present on the rich-BeF2 side. In particular, the calculated values of the key invariant points (i.e., 598.0 °C and 0.140 mol BeF2, 793.0 °C and 0.333 mol BeF2, and 480.0 °C and 0.667 mol BeF2) are almost the same as the experimental data (590.0 °C and 0.144 mol BeF2, 793.0 °C and 0.333 mol BeF2, and 480.0 °C and 0.667 mol BeF2), as shown in Table 5. As notably demonstrated by Fig. 4, the present calculated phase diagram of the KF-CsF system is in satisfactory agreement with the experimental data from Samuseva et al. [53], where the present calculated eutectic point of 624.3 °C and 0.571 mol CsF is almost the same as the experimental point of 625.0 °C and 0.570 mol CsF. The optimized solid solution point of 624.3 °C and 0.950 mol CsF also agrees well with the experimental point of 625.0 °C and 0.850 mol CsF. Fig. 5 displays the optimized phase diagram of the RbF-CsF system, where the optimized value corresponds well with the experimental data from Beneš et al. [54]. The present optimized minimum temperature on the liquidus (670.8 °C) agrees with the experimental results from Beneš et al. (677.85 °C and 673.85 °C).

Ternary system

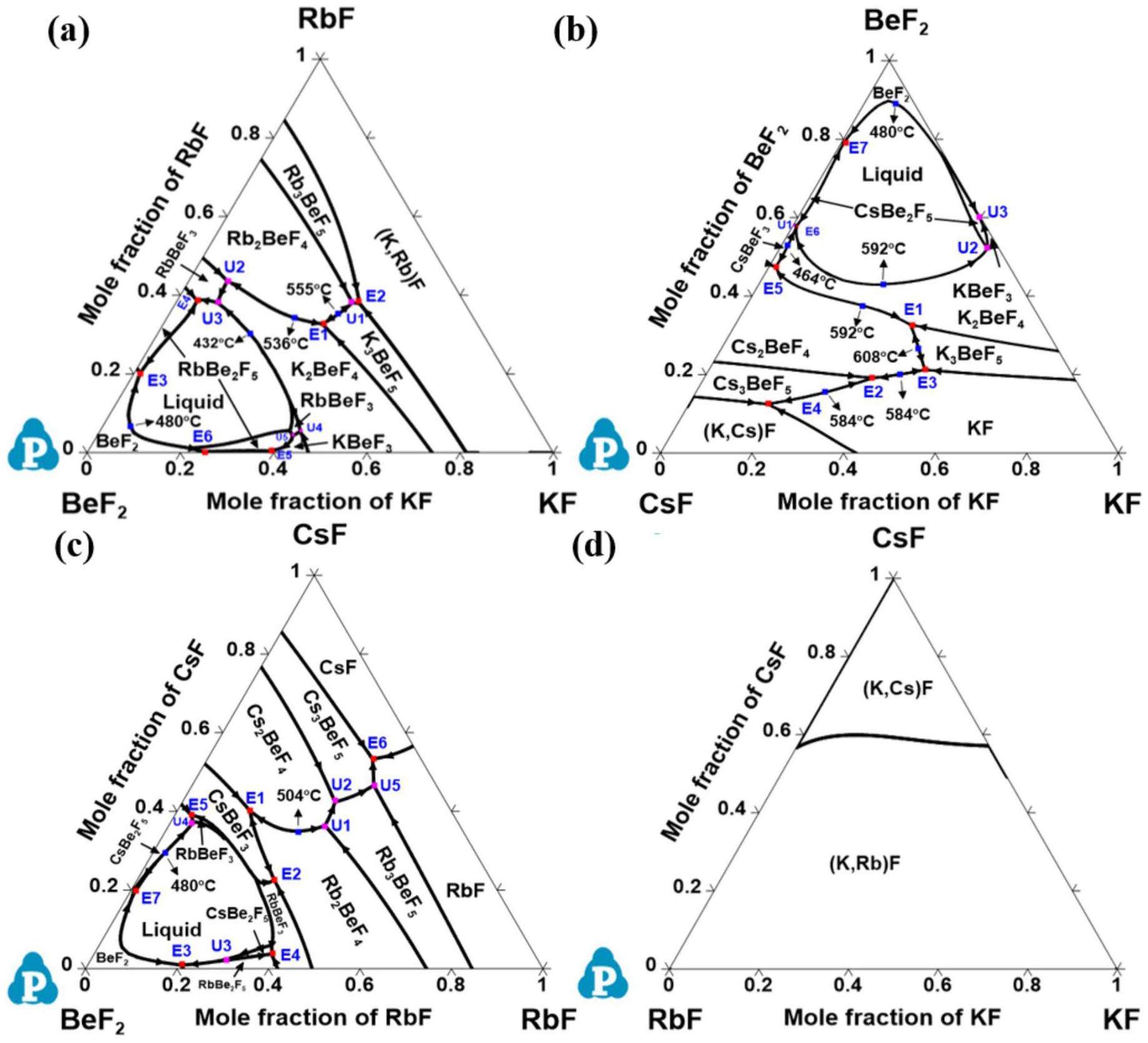

The liquidus projections of the ternary BeF2-KF-RbF, BeF2-CsF-KF, BeF2-CsF-RbF, and CsF-KF-RbF systems were calculated based on the thermodynamic parameters of the binary system using an extrapolation model. Figs. 6(a–d) show the liquidus projections of these ternary systems with the primary phases and temperatures formed during the solidification process. In Fig. 6(d), no ternary invariant point is observed for the CsF-KF-RbF system because of the inherent properties of its sub-binary system, that is, KF-RbF and RbF-CsF are isomorphous systems with a minimum in the liquids. The BeF2-KF-RbF system shown in Fig. 6(a) is characterized by six eutectic and five transition reactions, and the BeF2-CsF-KF system features seven eutectic reactions and three transition reactions, as shown in Fig. 6(b). The BeF2-CsF-RbF system is also characterized by seven eutectic reactions, but has five transition reactions, as depicted in Fig. 6(c). The results show that complex reactions can occur in the BeF2-KF-RbF, BeF2-CsF-KF, and BeF2-CsF-RbF systems during the solidification process. The detailed invariant reactions and temperatures of the BeF2-KF-RbF, BeF2-CsF-KF, BeF2-CsF-RbF, and CsF-KF-RbF systems are listed in Table 6.

| Ternary system (A-B-C) | Reaction type | Temp. (°C) | χA | χB | χC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeF2-KF-RbF | 537.7 | 0.3322 | 0.3405 | 0.3273 | |

| 529.1 | 0.2402 | 0.3786 | 0.3812 | ||

| 526.8 | 0.2258 | 0.3950 | 0.3792 | ||

| 423.3 | 0.4809 | 0.0823 | 0.4368 | ||

| 404.4 | 0.5298 | 0.0896 | 0.3806 | ||

| 382.3 | 0.7861 | 0.0128 | 0.2011 | ||

| 382.1 | 0.5703 | 0.0427 | 0.3870 | ||

| 378.0 | 0.5154 | 0.4309 | 0.0537 | ||

| 371.4 | 0.5376 | 0.4193 | 0.0431 | ||

| 321.7 | 0.6064 | 0.3892 | 0.0044 | ||

| 318.0 | 0.7442 | 0.2528 | 0.0030 | ||

| BeF2-CsF-KF | 597.7 | 0.3276 | 0.2907 | 0.3817 | |

| 578.9 | 0.1917 | 0.4399 | 0.3684 | ||

| 573.4 | 0.2126 | 0.3164 | 0.4710 | ||

| 553.3 | 0.1248 | 0.7035 | 0.1717 | ||

| 453.5 | 0.4746 | 0.5108 | 0.0146 | ||

| 392.6 | 0.5189 | 0.0282 | 0.4529 | ||

| 385.0 | 0.5240 | 0.0253 | 0.4507 | ||

| 383.9 | 0.5214 | 0.0250 | 0.4536 | ||

| 383.2 | 0.5239 | 0.0247 | 0.4514 | ||

| 359.8 | 0.7631 | 0.0056 | 0.2313 | ||

| BeF2-CsF-RbF | 495.0 | 0.2946 | 0.3639 | 0.3415 | |

| 469.8 | 0.2428 | 0.4240 | 0.3332 | ||

| 446.2 | 0.7025 | 0.0191 | 0.2784 | ||

| 409.1 | 0.4399 | 0.4016 | 0.1585 | ||

| 400.6 | 0.4746 | 0.2257 | 0.2997 | ||

| 387.8 | 0.5635 | 0.0597 | 0.3768 | ||

| 386.2 | 0.1366 | 0.4665 | 0.3969 | ||

| 383.4 | 0.7871 | 0.0098 | 0.2031 | ||

| 382.8 | 0.5745 | 0.0377 | 0.3878 | ||

| 374.9 | 0.5734 | 0.3894 | 0.0372 | ||

| 369.5 | 0.1057 | 0.5336 | 0.3607 | ||

| 359.4 | 0.7922 | 0.2018 | 0.0060 | ||

| CsF-KF-RbF | 624.3 | 0.5716 | 0.4284 | - | |

| 450.0 | 0.5664 | - | 0.4336 |

Quaternary system

The quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system was further investigated in terms of the thermodynamic databases of its sub-binary systems using an extrapolation model. The component proportions of the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system were predicted based on its melting temperature. Table 7 shows the detailed melting point data with the corresponding component proportions; the melting temperature is not higher than 450.0 °C, which is a commonly acceptable temperature for the coolant in an MSR. As shown in Table 7, 10 kinds of KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 systems with different proportions were obtained through the thermodynamic calculations, where the content of BeF2 varies from approximately 10 to 60 mol%. BeF2-based molten salts commonly have much higher viscosities when the BeF2 content of the molten salt is high (especially when the BeF2 content is greater than 50 mol%). Therefore, the proportion of BeF2 should be maintained within an acceptable range for practical applications. Thus, the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 systems labeled No. (1)–(9) were chosen as relatively appropriate heat transfer media for MSRs based on the melting temperature (Tm.p. ≤ 450 °C) and viscosity (i.e., BeF2 content ≤ 50 mol%). The local structures of the KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 molten salts with different portions will be further discussed based on first-principles calculations in the following section.

| Ternary system (A-B-C) | No. | Temp. (°C) | χA | χB | χC | χD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 | (1) | 450.0 | 0.0180 | 0.3542 | 0.5240 | 0.1038 |

| (2) | 450.0 | 0.3814 | 0.0043 | 0.0200 | 0.5943 | |

| (3) | 450.0 | 0.0200 | 0.0365 | 0.3816 | 0.5619 | |

| (4) | 378.7 | 0.0102 | 0.0368 | 0.3854 | 0.5676 | |

| (5) | 394.0 | 0.0806 | 0.3565 | 0.0347 | 0.5282 | |

| (6) | 450.0 | 0.1665 | 0.3232 | 0.0314 | 0.4789 | |

| (7) | 450.0 | 0.0327 | 0.1533 | 0.3885 | 0.4255 | |

| (8) | 431.5 | 0.0257 | 0.1544 | 0.3913 | 0.4286 | |

| (9) | 402.6 | 0.0350 | 0.2892 | 0.2178 | 0.4580 | |

| (10) | 450.0 | 0.0658 | 0.2800 | 0.2108 | 0.4434 |

RDFs

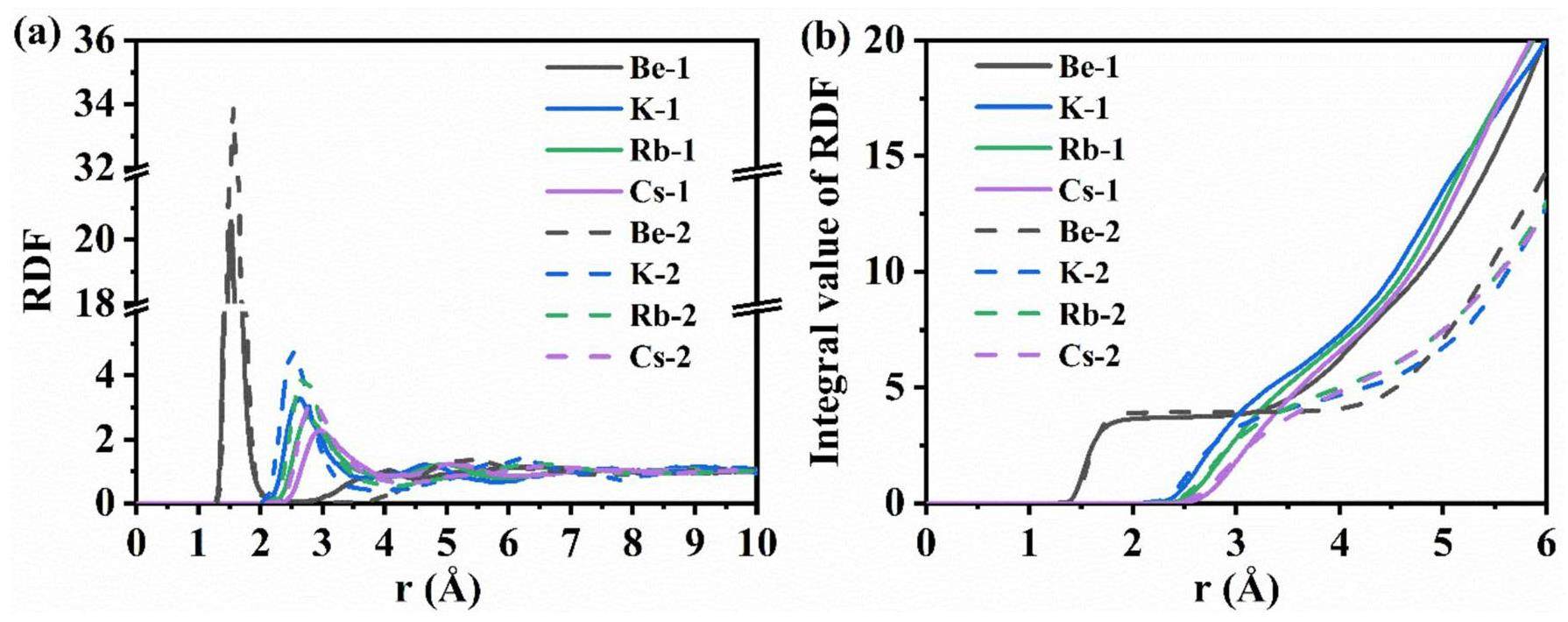

In the AIMD calculations, the NPT ensemble simulations revealed that the equilibrium densities of Mixture 1 (KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2, 3.50-28.92-21.78-45.80 mol%) and Mixture 2 (KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2, 1.80-35.42-52.40-10.38 mol%) at 650 °C were 2.22 g/cm3 and 2.72 g/cm3, respectively. Fig. 7(a) presents the RDFs of the Be-F, K-F, Rb-F, and Cs-F ion pairs in the two molten salt systems. These systems exhibit some similar features. The RDFs for all cation–anion pairs have sharper and stronger first peaks, indicating an ordered arrangement of F– around Be2+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+. As the distance increases, the fluctuations of the RDFs gradually decrease and tend towards 1, reflecting the short-range order and long-range disorder in the microstructure of the molten salt systems. The highest first peak is observed for the Be-F ion pair, with the peak valley being almost zero, indicating a strong interaction between Be2+ and F–. This finding suggests that F– has more difficulty escaping from the coordination shell of Be2+ compared to those of other cations. The relative interaction strength of the cations with F– in the same system can be inferred from the heights of the first peaks for each ion pair as follows: Be2+ > K+ > Rb+ > Cs+. This correlates with the average charge of the cations, and a higher charge results in stronger interactions with F–. Be2+ has the highest valence state and the smallest ionic radius among the cations, resulting in the strongest interaction. K+, Rb+, and Cs+ have the same valence state, and their interaction strength with F– decreases with increasing ionic radius: Cs+ > Rb+ > K+.

The first peak of the RDF of each ion pair in Mixture 1 is lower than that in Mixture 2, indicating a more ordered arrangement of F– around the cations in Mixture 2. The first peak position of the RDF typically represents the average bond length of the ion pair (Table 8). The peak positions of Be-F, K-F, Rb-F, and Cs-F in Mixture 1 are 1.55, 2.63, 2.77, and 2.95, respectively, and 1.57, 2.51, 2.69, and 2.83 in Mixture 2. With decreasing Be2+ content in Mixture 2, the average bond length of the Be-F ion pairs remains relatively unchanged, which is attributed to the strong interaction between Be2+ and F-. The Be–F bond length is almost the same as that in the LiF-BeF2 system [48]. The peak positions for the other cation–anion pairs decrease significantly in Mixture 2 compared to those in Mixture 1. The bond length also reflects the strength of the ion pairs; shorter bond lengths indicate stronger interactions between the same ion pairs. Thus, the interactions between the cations and F– in Mixture 2 are stronger than those in Mixture 1. Because the concentration of Be2+ is higher in Mixture 1, F– preferentially binds with Be2+, thereby weakening its interactions with the other cations.

| Mixture 1 | Mixture 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First peak | Rcut | CNs | First peak | Rcut | CNs | |

| Be-F | 1.55 | 2.45 | 3.72 | 1.57 | 2.43 | 3.93 |

| K-F | 2.63 | 3.69 | 6.14 | 2.51 | 3.61 | 4.23 |

| Rb-F | 2.77 | 3.97 | 6.73 | 2.69 | 3.93 | 4.89 |

| Cs-F | 2.95 | 4.11 | 7.03 | 2.83 | 4.09 | 5.01 |

CNs

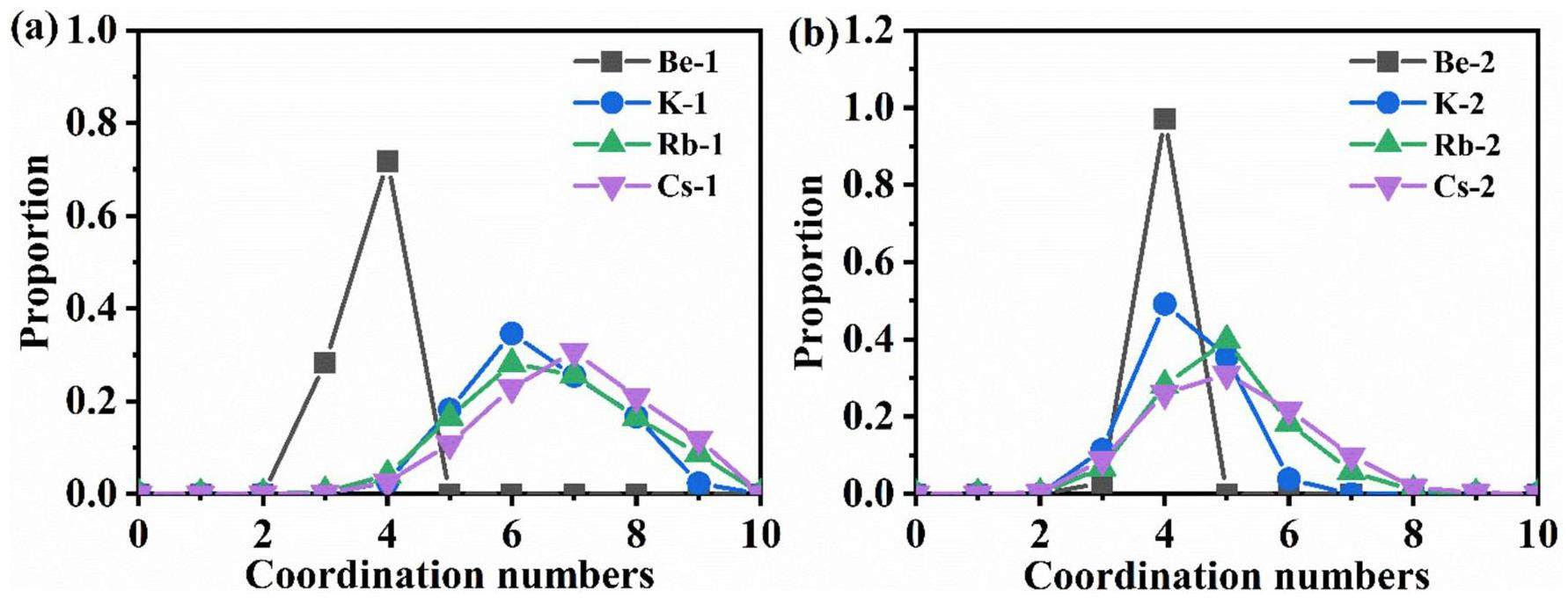

The CNs were obtained by integrating the RDFs of the ion pairs. Fig. 7(b) shows the integral values of the RDF for the Be-F, K-F, Rb-F, and Cs-F pairs in the two molten salt systems. In general, the values corresponding to Rcut in Fig. 7(b) are the CNs, and the calculated CNs for each cation are listed in Table 6. In Mixture 1, the CNs of Be2+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+ are 3.72, 6.14, 6.73, and 7.03, respectively, and in Mixture 2, they are 3.93, 4.23, 4.89, and 5.01, respectively. Except for Be2+, the CNs of the other cations in Mixture 1 are larger than those in Mixture 2, which is mainly owing to the higher concentration of F– in Mixture 1. Additionally, for the K-F, Rb-F, and Cs-F ion pairs, the integral curves do not exhibit a clear plateau near Rcut, as is present for the Be-F pair. Therefore, these cations can localize F– within a certain range, but there are no compact complex structures as Be2+. Furthermore, the proportions of CNs for all cations within the Rcut were calculated to study the coordination preference with F–, as shown in Fig. 8. Be2+ predominantly forms 4-fold coordination structures in both systems, like in the LiF-BeF2 system, where Be2+ is dominated by [BeF4]2– [48]. For the K-F, Rb-F, and Cs-F ion pairs, the coordinated structures in their first coordination shells range from 2-fold to 9-fold. The 6-fold and 7-fold coordination structures account for the largest two portions in Mixture 1, whereas the 4-fold and 5-fold structures account for the largest portions in Mixture 2.

ADFs

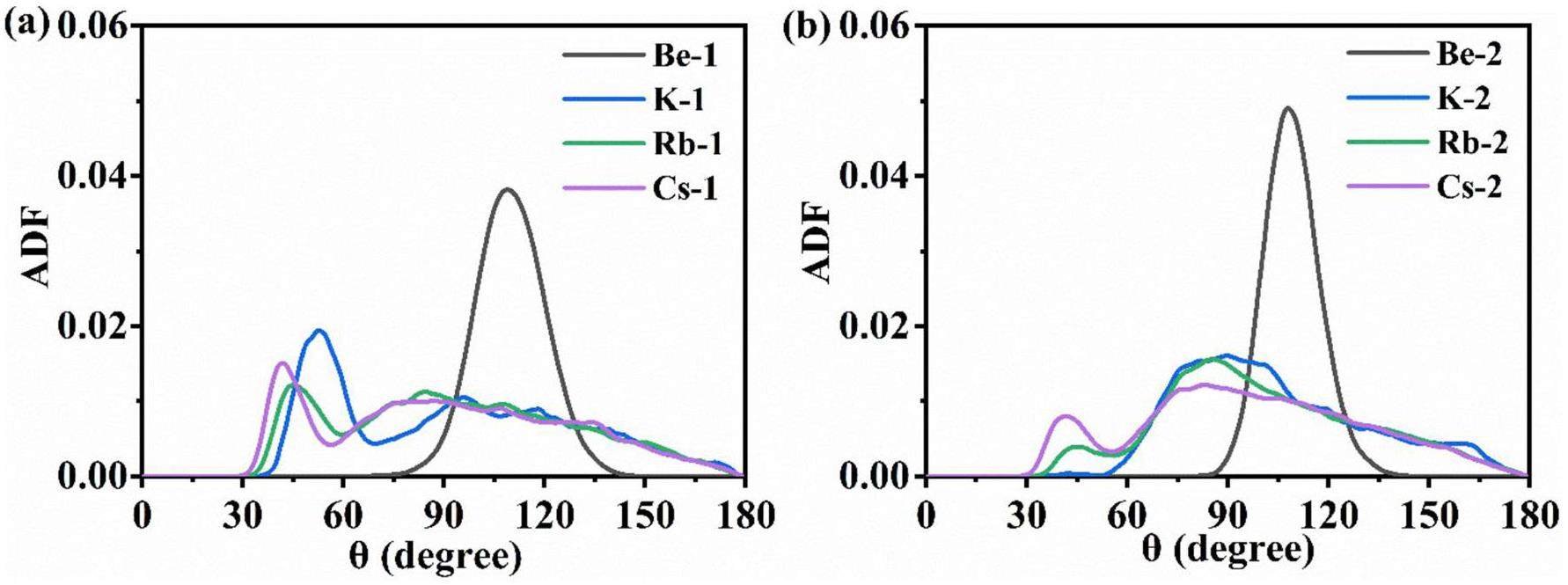

To describe the three-body correlations of the ions in the molten salt systems further, the ADFs of F-Be-F, F-K-F, F-Rb-F, and F-Cs-F were calculated, as shown in Fig. 9. The angle of F-Be-F is mainly distributed in the range of 90°–130° both in Mixtures 1 and 2, with the maximum peak at approximately 109°. This corresponds to the slightly distorted tetrahedral [BeF4]2–, consistent with that in the LiF-BeF2 system [1]. For the F-K-F, F-Rb-F, and F-Cs-F pairs, the angle distribution range is wide and different from that for the F-Be-F pair in both Mixtures 1 and 2, and various coordination structures ranging from 2-fold to 9-fold exist, as shown in Fig. 9. This is because K+, Rb+, and Cs+ do not form compact ion structures with F–.

Diffusion coefficient

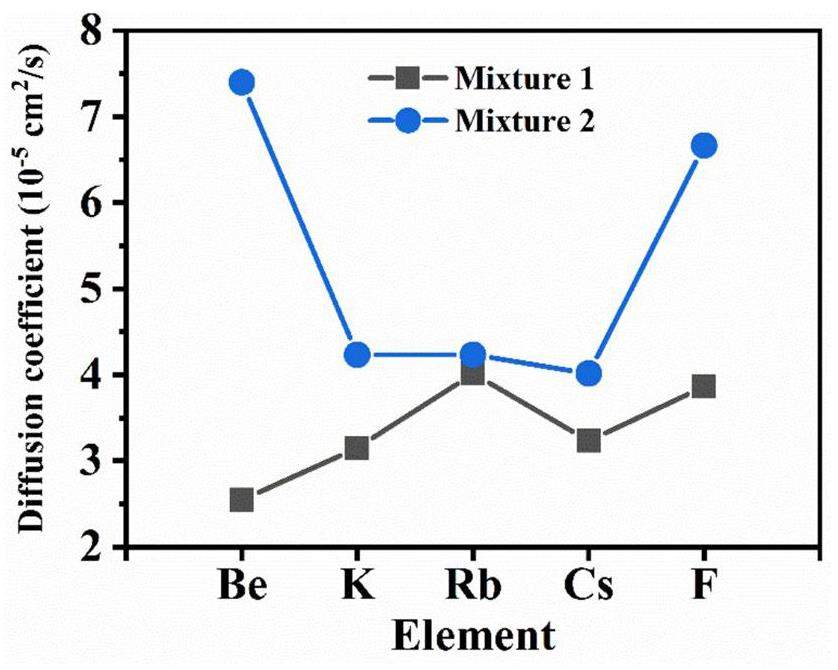

The diffusion coefficients of the ions were calculated using Eqs. (12) and (13), as illustrated in Fig. 10. The diffusion coefficients of Be2+, K+, Rb+, Cs+, and F– in Mixture 2 are

Conclusions

The binary (KF-BeF2, RbF-BeF2, CsF-BeF2, KF-CsF, and RbF-CsF), ternary (BeF2-KF-RbF, BeF2-CsF-KF, BeF2-CsF-RbF, and CsF-KF-RbF), and quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 systems were thermodynamically calculated using the CALPHAD technique. Furthermore, the RDFs, CNs, ADFs, and diffusion coefficients of the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system were calculated using AIMD. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

(1) A set of self-consistent and reliable thermodynamic databases for the KF-BeF2, RbF-BeF2, CsF-BeF2, KF-CsF, and RbF-CsF systems was established.

(2) The liquidus projections and invariant points of BeF2-KF-RbF, BeF2-CsF-KF, BeF2-CsF-RbF, and CsF-KF-RbF systems were obtained.

(3) The melting temperatures (Tm.p. ≤ 450 °C) for quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 systems with different compositions were obtained.

(4) The interaction strength between cations and anions in the system followed the order Be-F > K-F > Rb-F > Cs-F. The CNs of all cations were determined.

(5) A high Be2+ concentration can reduce the diffusion coefficients of the ions, especially Be2+ and F–.

The present study is the first of its type, to the best of our knowledge, and the results show that the quaternary KF-RbF-CsF-BeF2 system with the proportion 3.50-28.92-21.78-45.80 mol% or 1.80-35.42-52.40-10.38 mol% is one of the most promising candidate coolants for MSRs in terms of thermodynamics (i.e., Tm.p. ≤ 450 °C with appropriate viscosity) and kinetics (i.e., suitable local structure and diffusion coefficient). This work not only drastically enriches the databases of molten salts, but also provides direct guidelines for screening and optimizing molten salts in the nuclear energy field.

Burnup optimization of once-through molten salt reactors using enriched uranium and thorium

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-00995-2.The molten salt reactor (MSR) in generation IV: Overview and perspectives

. Prog. Nucl. Energy 77, 308-319 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2014.02.014.Corrosion behaviour of 316H stainless steel in molten FLiNaK eutectic salt containing graphite particles

. Corros. Sci. 160,A technology roadmap for generation IV nuclear energy systems

.Molten Salt Reactors-History, Status, and Potential

. Nuclear Applications and Technology 8, 107-117 (1970). https://doi.org/10.13182/NT70-A28619.A neutronics-thermal coupling-based rapid assessment method for molten salt reactor fuel draining system

. Appl. Therm. Eng. 270,Preparation and characterization of graphene-nanosheet-reinforced Ni-17Mo alloy composites for advanced nuclear reactor applications

, Materials 18, 1061 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18051061.Neutron/Gamma radial shielding design of main vessel in a small modular molten salt reactor

. J. Nucl. Eng. 4, 213 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/jne4010017.Review of thermophysical property methods applied to fueled and un-fueled molten salts

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 146,Evaluating physical properties of molten salt reactor fluoride mixtures

. J. Fluor. Chem. 130, 30-37 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluchem.2008.07.018.Thermodynamic properties and phase diagrams of fluoride salts for nuclear applications

. J. Fluor. Chem. 130, 22-29 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluchem.2008.07.014.The effect of corrosion product CrF3 on thermo-physical properties of FLiNaK

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 53, 61-68 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2015.1026859.Research status of electrolytic preparation of rare earth metals and alloys in fluoride molten salt system: a mini review of china

. Metals 14, 407 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/met14040407.Thermodynamic study of LiF–BeF2–ZrF4–UF4 system

. J. Alloys Compd. 452, 110-115 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.01.184.Fuel Cycle of the LiF–BeF2 Molten Salt Actinide Burner Reactor

. Phys. At. Nucl. 86, 1894-1901 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778823080276.Thermodynamic analysis of LiF–BeF2 and KF–BeF2 melts by a structural model

. J. Fluor. Chem. 130, 336-340 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluchem.2008.12.008.Use of the Soft-Sphere Equation of State to predict the thermodynamic properties of the molten salt mixtures LiF–BeF2, NaF–BeF2, and KF–BeF2

. Prog. Nucl. Energy 68, 188-199 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnucene.2013.06.008.Corrosion behavior of GH3535 alloy in molten LiF–BeF2 salt

. Corros. Sci. 199,Experience with the molten salt reactor experiment

. Nuclear Applications and technology 8, 118-137 (1970). https://doi.org/10.13182/NT8-2-118.Fluoride Model Systems: IV, The Systems LiF-BeF2 and PbF2-BeF2

. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 37, 300-305 (1954). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1954.tb14042.x.Phase Diagrams of Nuclear Reactor Materials. ORNL report No. 2548

,New electrochemical measurements of the liquidus in the lithium fluoride-beryllium fluoride system. Congruency of lithium beryllium fluoride (Li2BeF4)

. J. Phys. Chem. 76, 1154-1159 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1021/j100652a012.Electromotive force study of molten lithium fluoride-beryllium fluoride solutions

. Inorg. Chem. 8, 201-207 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1021/ic50072a004.Enthalpies of mixing in liquid beryllium fluoride-alkali fluoride mixtures

. Inorg. Chem. 8, 207-212 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1021/ic50072a005.A miscibility gap in LiF–BeF2 and LiF–BeF2–ThF4

. J. Nucl. Mater. 344, 94-99 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2005.04.023.Estimation of Melting Points for Some Binary and Tertiary Fluoride Molten Salts

. Fusion Sci. Technol. 66, 322-336 (2014). https://doi.org/10.13182/FST13-694.Reactor Chemistry Division Annual Progress Report for Period Ending December 31, 1965, ORNL report No. 3913

.Viscosity and density in molten BeF2–LiF solutions

. J. Chem. Phys. 50, 2874-2879 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1671478.Molten-salt reactor program semiannual progress report, ORNL report No. 4449

,Reference Correlations for the Viscosity of Molten LiF-NaF-KF, LiF-BeF2, and Li2CO3-Na2CO3-K2CO3

. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 48,The Viscosity of Molten Salts Based on the LiF–BeF2 System

. Russ. J. Non-Ferrous Met. 63, 276-283 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3103/S1067821222030117.The Thermodynamic and physical properties of beryllium compounds. I. enthalpy and entropy of vaporization of beryllium fluoride

. J. Phys. Chem. 67, 36-40 (1963). https://doi.org/10.1021/j100795a009.A First-Principles Description of Liquid BeF2 and Its Mixtures with LiF: 2. Network Formation in LiF−BeF2

. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 11461-11467 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1021/jp061002u.Structure and transport properties of LiF–BeF2 mixtures: Comparison of rigid and polarizable ion potentials

. J. Chem. Sci. 124, 261-269 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12039-012-0225-5.A new approach for coupled modelling of the structural and thermo-physical properties of molten salts

. Case of a polymeric liquid LiF-BeF2. J. Mol. Liq. 299,Raman and theoretical studies on structural evolution of Li2BeF4 and binary LiF-BeF2 melts

. J. Mol. Liq. 325,Fluoride Model Systems: III, The System NaF–BeF2 and the Polymorphism of Na2BeF4 and BeF2

. J. Am. Ceram. 36, 185-190 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1953.tb12864.x.Thermodynamic Evaluation of NaF-MFn(M=Be, U, Th) Systems for Molten Salt Reactor

. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 34, 457-463 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40242-018-7398-5.Molten Salts: Volume 4, Part 1, Fluorides and Mixtures Electrical Conductance, Density, Viscosity, and Surface Tension Data

. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 3, 1-115 (1974).Vapor Pressures and Molecular Composition of Vapors of the Sodium Fluoride-Beryllium Fluoride System

. J. Phys. Chem. 62, 453-457 (1958). https://doi.org/10.1021/j150562a020.Thermodynamics of the LiF–NaF–BeF2 system at high temperatures

. Fluid Phase Equilib. 255, 1-10 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fluid.2007.01.041.HT-NMR Studies of the Be–F Coordination Structure in FNaBe and FLiBe Mixed Salts

. JACS Au 4, 2211-2219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacsau.4c00177.Mapping relationships between cation-F bonds and the heat capacity, thermal conductivity, viscosity of molten NaF-BeF2

. J. Mol. Liq. 354,Thermal and X-ray analysis of the KF-BeF2 system

. Zbur. Neorg. Kbirn. 1, 2071-2082 (1956).KF-BeF2 system

. Zh. Neorg. Khim. 9, 2042 (1964).Investigation of the Phase Diagram of the RbF-BeF2 System and of Its Relationship to the BaO-SiO System

. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 114, 316-319 (1957).Thermal and X-ray phase analysis of the system CsF-BeF2 and its interrelationship with MeF and BeF2 systems

. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 118, 935-937 (1958).Temperature-dependent properties of molten Li2BeF4 Salt using Ab initio molecular dynamics

. ACS omega 6, 19822-19835 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c02528.First-principle investigation of the structure and vibrational spectra of the local structures in LiF–BeF2 Molten Salts

. J. Mol. Liq. 213, 17-22 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2015.10.053Diffusion behaviors of HF in molten LiF-BeF2 and LiF-NaF-KF eutectics studied by FPMD simulations and electrochemical techniques

. J. Nucl. Mater. 572,Influence of ZrF4 additive on the local structures and thermophysical properties of molten NaF-BeF2

. J. Mol. Liq. 393,Molecular simulation of translational and rotational diffusion of Janus nanoparticles at liquid interfaces

. J. Chem. Phys. 142,System CsF-KF and Cs-RbF

. Zh. Neorg. Khim. 10, 1270-1272 (1965).Density functional theory, molecular dynamics, and differential scanning calorimetry study of the RbF-CsF phase diagram

. J. Chem. Phys. 13,Phase Diagrams and Thermodynamic Properties of the 70 Binary Alkali Halide Systems Having Common Ions

. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 16, 509-561 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.555803.Thermodynamic description for the NaF-KF-RbF-ZnF2 system

. J. Fluor. Chem. 217, 90-96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfluchem.2018.09.008.Thermodynamic optimization of the constitutive binaries of the LiCl/RbCl/CaCl2-NaCl-UCl3-PuCl3 systems

. Calphad 77,Development of Deep Potentials of Molten MgCl2–NaCl and MgCl2–KCl Salts Driven by Machine Learning

. ACS Appl. Mater. 15, 14184-14195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c19272.First-principles study on the diffusion behavior of Cs and I in Cr coating

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 100 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01460-y.Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set

. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15-50 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0.Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set

. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169-11186 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169.Adhesion property of AlCrNbSiTi high-entropy alloy coating on zirconium: experimental and theoretical studies

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 141 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01508-z.Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation

. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 46, 6671-6687 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.46.6671.Ernzerhof, Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865-3868 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865.Projector augmented-wave method

. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 50, 17953-17979 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953.Special points for Brillouin zone integrations'a reply

. Phys. Rev. B 16, 1748-1749 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.16.1748.Crystal Structure and Pair Potentials: A Molecular-Dynamics Study

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1196-1199 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.1196.Computer ‘‘experiment’’ for nonlinear thermodynamics of Couette flow

. J. Chem. Phys. 78, 3297-3302 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.445195.Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions

. Phys. Rev A. Gen. Phys. 31, 1695-1697 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.31.1695.A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods

. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 511-519 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.447334.Chemical states of corrosion products in liquid lead from ab initio molecular dynamics

. J. Nucl. Mater. 599,Molecular dynamics simulations of CaCl2–NaCl molten salt based on the machine learning potentials

. Sol. Energy Mater Sol. Cells 254,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.