Introduction

Advancements in beam quality and detection technology in the latest generation of radiation nuclear beam facilities have brought the study of reaction mechanisms induced by weakly bound nuclei in the Coulomb barrier energy region to the forefront of nuclear physics research [1, 2]. In contrast to the fusion processes involving strongly bound nuclei, the mechanisms triggered by weakly bound nuclei are complex because of their lower binding energies. This complexity is mainly exemplified by the extended nuclear matter distribution and breakup effect [3, 4]. The former, a static effect, results in a reduction in the average fusion barrier height, consequently enhancing the fusion cross-sections. The dynamic breakup of the projectile can diminish the flux of direct fusion reactions, leading to three distinct processes: (1) Sequential complete fusion (SCF), where all fragments resulting from the breakup fuse with the target; (2) incomplete fusion (ICF), where only some of the breakup fragments are absorbed by the target; and (3) no capture breakup (NCBU), where none of the breakup fragments are captured by the target. The reaction process, in which the entire projectile without breakup is captured by the target, is termed direct complete fusion (DCF). However, from an experimental perspective, differentiating between the fusion yields of SCF and DCF is challenging. As a result, only complete fusion (CF) cross-sections, including both DCF and SCF cross-sections, can be measured.

Over the last few decades, numerous experimental [5-8] and theoretical [9-11] studies have been conducted on fusion reactions involving weakly bound nuclei. The main objective of these studies was to investigate the influence of breakup on fusion reactions near the Coulomb barrier [12-14]. One of the most widely adopted approaches is to compare data with predictions from a single-barrier penetration model [15, 16] or a coupled channel model without breakup channels [17-19]. It has been demonstrated that the CF cross-sections are suppressed at energies near and above the Coulomb barrier [20, 21]. Thus far, the dependence of the suppression effect on the breakup threshold energy of the projectile has been revealed, and an empirical relationship between the suppression factors and threshold energies has been reported [22]. However, suppression phenomena with various target nuclei remain unexplained [14, 23] and no systematic behavior of the CF suppression factors has been observed in the relatively heavy-mass target region [1]. For light- and medium-mass targets, the behavior of the suppression factor has not been fully established because of the experimental difficulty in distinguishing residues from ICF and CF. Therefore, we extended a machine learning method to fusion reactions induced by weakly bound projectiles and analyzed the systematic behavior of suppression factors across various mass target regions.

Bayesian neural networks (BNNs), one of the commonly used machine learning methods, have been applied to various problems in nuclear physics, such as predicting atomic nuclear mass [24, 25], nuclear charge radii [26, 27], nuclear β-decay half-life [28], nuclear fission yields [29-31], spallation reactions [32-34], fragmentation reactions [35-37], and neutron nuclear reactions [38]. In this study, based on 475 experimental data points from 39 reaction systems induced by 6,7Li, 9Be, and 10B, a BNN was constructed to evaluate the CF cross-sections of weakly bound nuclei for the first time. A systematic analysis of the suppression effect at energies above the Coulomb barrier was also conducted. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the main characteristics of the proposed BNN method are briefly described. Prediction results are presented in Sect. 3. Section 4 presents a summary.

Model Descriptions

As a prominent machine learning technology, BNNs are highly effective for constructing novel models based on existing data. BNNs, which comprise a specific number of input units, hidden units of several layers, and output units, are capable of delivering high-quality predictions [39, 40]. This section presents a simple description of the BNN methodology. More detailed information can be found in [32, 35] and citations therein.

Bayesian learning sets the prior distribution of the model,

In this study, the dataset comprised the measured CF cross-sections in 39 reactions induced by 6,7Li, 9Be, and 10B, giving rise to 475 data points, as detailed in Table 1 [41-68]. Within this dataset, the incident energy of the reactions ranges from 0.67Vb to 2.06Vb, where Vb is the Coulomb barrier energy obtained from Akyüz-Winther nuclear potential and point-sphere Coulomb potential. The mass and charge of the target nuclei fall within the ranges of 64 ≤ At ≤ 209 and 2852, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, Zt ≤ 83, respectively. For model development, 380 data points (80% of all data) were randomly selected to form the training set, facilitating neural network learning and parameter optimization. The remaining 20% served as the test set to evaluate the prediction capabilities of the network. The input layer contains five parameters,

| Reaction | Ecm/VB | Nexp | FBNN | Fexp | Ref. | Reaction | Ecm/VB | Nexp | FBNN | Fexp | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6Li+64Ni | 0.85-2.06 | 15 | 0.87 | 0.88 | [41] | 7Li+159Tb | 1.07-1.66 | 5 | 0.71 | 0.73 | [57] |

| 6Li+90Zr | 0.82-1.65 | 8 | 0.67 | 0.7 | [17] | 7Li+165Ho | 0.86-1.69 | 10 | 0.79 | 0.74 | [15] |

| 6Li+94Zr | 0.89-1.68 | 5 | 0.52 | 0.49 | [7] | 7Li+197Au | 0.81-1.50 | 8 | 0.84 | 0.86 | [50] |

| 6Li+96Zr | 0.90-1.58 | 7 | 0.77 | 0.77 | [42] | 7Li+198Pt | 0.79-1.52 | 6 | 0.72 | 0.77 | [58] |

| 6Li+120Sn | 0.74-1.32 | 13 | 0.78 | 0.81 | [43, 44] | 7Li+205Tl | 0.82-1.31 | 10 | 0.77 | 0.74 | [59] |

| 6Li+124Sn | 0.83-1.70 | 15 | 0.72 | 0.66 | [45] | 7Li+209Bi | 0.83-1.67 | 21 | 0.75 | 0.77 | [53] |

| 6Li+144Sm | 0.79-1.58 | 11 | 0.55 | 0.54 | [46] | 9Be+89Y | 0.83-1.39 | 15 | 0.78 | 0.75 | [60] |

| 6Li+152Sm | 0.80-1.60 | 20 | 0.63 | 0.62 | [47] | 9Be+93Nb | 0.85-1.45 | 7 | 0.85 | 0.90 | [61] |

| 6Li+154Sm | 1.04-1.45 | 6 | 0.64 | 0.71 | [48] | 9Be+124Sn | 0.90-1.33 | 13 | 0.73 | 0.75 | [62] |

| 6Li+159Tb | 0.87-1.50 | 13 | 0.65 | 0.66 | [49] | 9Be+144Sm | 0.89-1.31 | 10 | 0.92 | 0.94 | [63] |

| 6Li+197Au | 0.84-1.35 | 16 | 0.61 | 0.60 | [50] | 9Be+169Tm | 0.93-1.33 | 12 | 0.78 | 0.80 | [64] |

| 6Li+198Pt | 0.67-1.14 | 10 | 0.75 | 0.75 | [51] | 9Be+181Ta | 0.94-1.34 | 13 | 0.66 | 0.68 | [65] |

| 6Li+208Pb | 0.92-1.28 | 20 | 0.67 | 0.69 | [52] | 9Be+186W | 1.08-1.40 | 4 | 0.59 | 0.57 | [66] |

| 6Li+209Bi | 0.83-1.53 | 14 | 0.65 | 0.68 | [53] | 9Be+187Re | 0.93-1.28 | 12 | 0.75 | 0.76 | [64] |

| 7Li+64Ni | 0.87-2.06 | 16 | 0.90 | 0.90 | [54] | 9Be+197Au | 0.83-1.17 | 12 | 0.78 | 0.70 | [67] |

| 7Li+93Nb | 1.29-1.63 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.75 | [55] | 9Be+208Pb | 0.88-1.24 | 16 | 0.78 | 0.79 | [53] |

| 7Li+119Sn | 0.72-1.30 | 15 | 0.93 | 0.94 | [43, 44] | 9Be+209Bi | 0.88-1.21 | 19 | 0.98 | 0.98 | [52] |

| 7Li+124Sn | 0.79-1.86 | 23 | 0.71 | 0.73 | [56] | 10B+159Tb | 0.91-1.66 | 16 | 0.87 | 0.87 | [57] |

| 7Li+144Sm | 0.88-1.59 | 14 | 0.63 | 0.63 | [18] | 10B+209Bi | 1.06-1.44 | 5 | 0.88 | 0.89 | [68] |

| 7Li+152Sm | 0.81-1.61 | 16 | 0.66 | 0.69 | [18] |

Results and Discussion

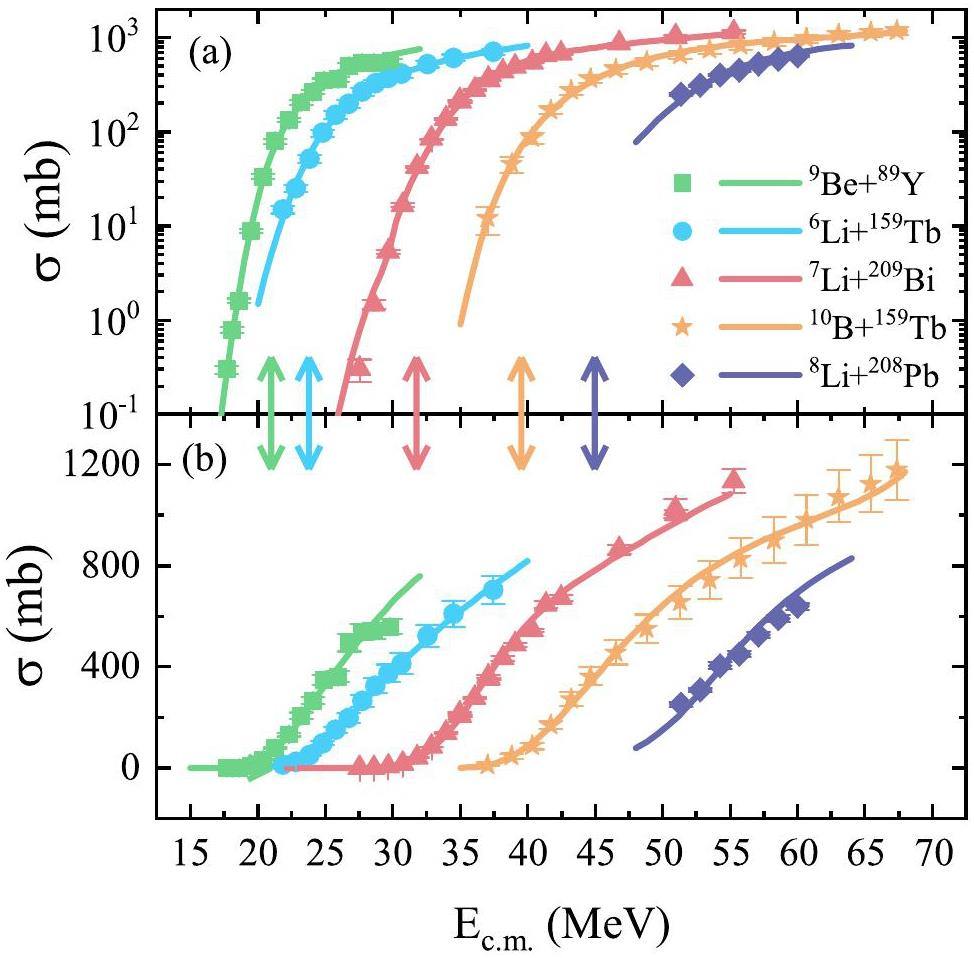

To verify the evaluation capacity of the BNN model, we performed a comparison between the predicted CF cross-sections and the experimental data, as depicted in Fig. 1. A logarithmic scale in Fig. 1(a) and a linear scale in Fig. 1(b) were adopted to compare the details of the cross-sections at sub-barrier and above-barrier energies, respectively. Taking the 6Li + 159Tb, 7Li + 209Bi, 9Be + 89Y, and 10B + 159Tb systems from the dataset as examples, the predicted results were in good agreement with the experimental CF cross-sections, both at sub-barrier and above-barrier energies. Furthermore, for the reaction system 8Li + 208Pb [69], which was not included in the dataset, the BNN model provided results consistent with the experimental data.

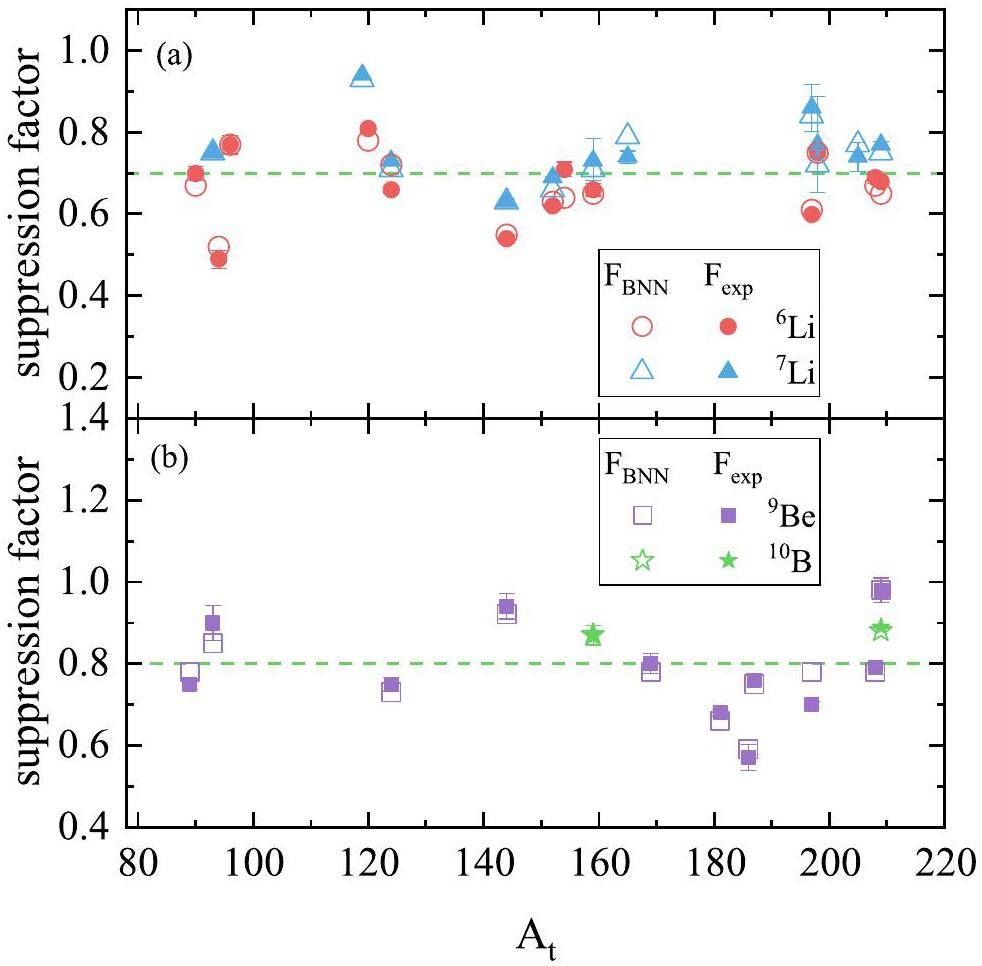

To further investigate the effects of the breakup channel on the fusion of weakly bound systems, a systematic analysis of the suppression factors of CF cross-sections at above-barrier energies is presented below. The suppression factors were obtained by fitting the CF cross-sections obtained from the BNN model or the experimental data using

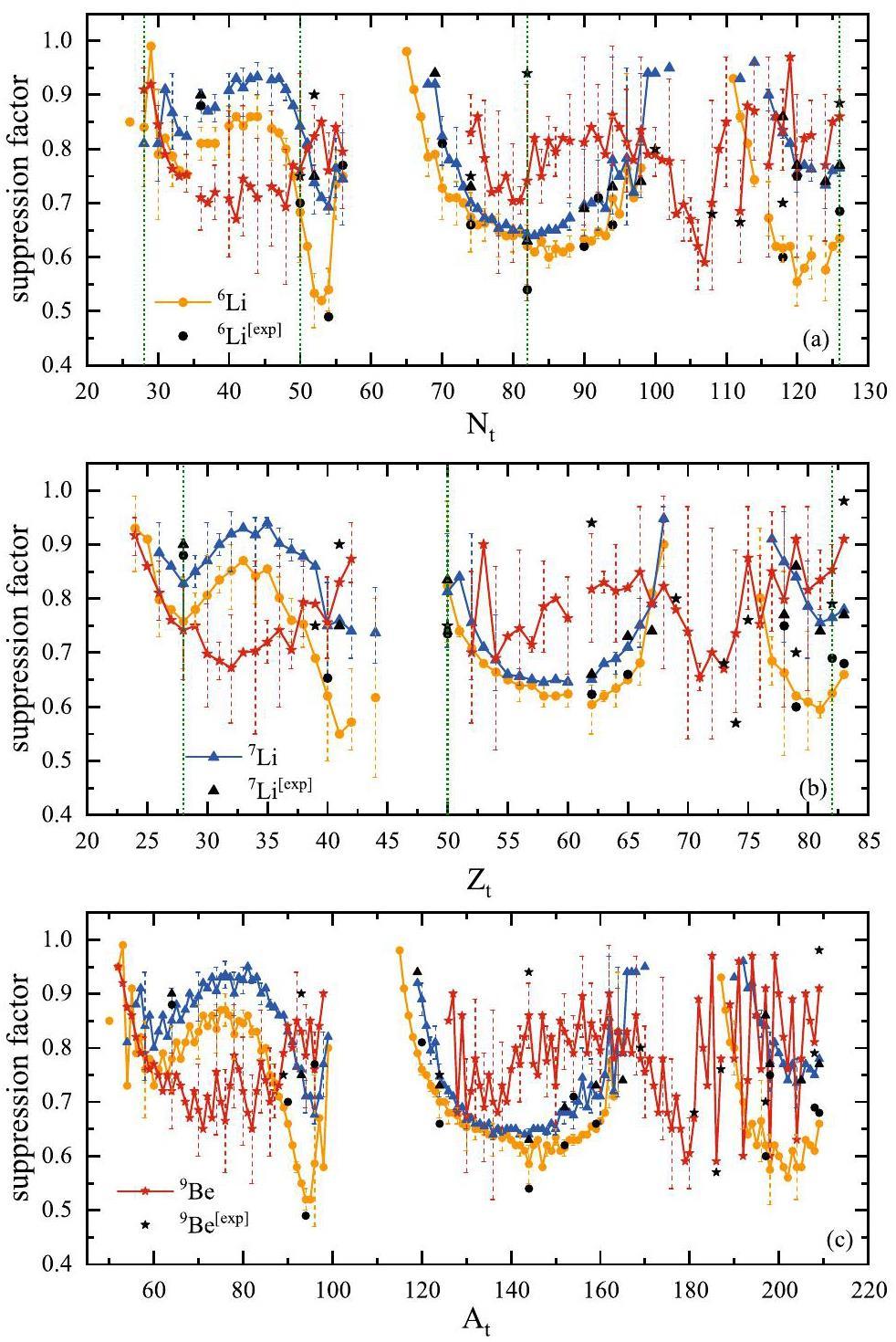

Next, we extended this BNN model to various mass regions of the target nucleus, including relatively light- and medium-mass targets. The CF cross-sections of 6,7Li and 9Be with the target nuclei along β stability line were predicted. The calculated suppression factors versus neutron, proton, and mass numbers of the targets are shown in Fig. 3. A surprising conclusion is that there is no suppression effect in the vicinity of At = 110 targets for 6,7Li and 9Be, and At = 180 targets for 6,7Li. This was derived from the overall trend of the available experimental data; further experimental CF cross-sections are necessary to verify this conclusion.

In Fig. 3, the solid symbols denote the mean suppression factors derived from the targets with identical neutron (a), proton (b), and mass (c) numbers. Dashed error bars indicate corresponding distribution ranges. Taking lead isotopes as an example, the predicted suppression factors of the BNN model for 7Li + 204,206,207,208Pb were 0.78, 0.77, 0.76, and 0.75, respectively. The mean suppression factor (0.765), upper limit of the error bar (0.78), and lower limit of the error bar (0.75) are located at Zt = 82 in Fig. 3(b). Consequently, the range of error bars indicates the dependence of the suppression effect on the isotone, isotope, and isobar target nuclei. The small error bars of 6Li and 7Li suggest weak dependence, whereas the suppression factors of 9Be exhibit strong dependence. Owing to this sensitivity to the number of nucleons in the target nucleus, there is a pronounced fluctuation in various target nuclei for 9Be. This makes it difficult to identify a systematic trend for 9Be.

For 6Li and 7Li, the consistent behavior of the mean suppression factor suggests that they possess a similar breakup mechanism, and the minimum values of the suppression factor occur near the target nuclei with a neutron-closed shell. Within the relatively light mass target region (

Summary

In this study, we investigated the complete fusion reactions of weakly bound nuclei using machine learning methods. A BNN was constructed based on 475 existing experimental complete fusion data points induced by 6,7Li, 9Be, and 10B. This model characterizes five input parameters (projectile and target information, and colliding energy), double hidden layers (16 + 16 neural units), and one output parameter (CF cross-section). The CF cross-sections predicted by this model exhibited excellent agreement with the experimental data, demonstrating the high-quality predictive capabilities of the model.

The suppression factors, defined as the ratio of the CF cross-sections predicted by BNN model to those calculated by a single-barrier penetration model at above-barrier energies, were systematically analyzed for weakly bound projectiles 6,7Li and 9Be with the target nuclei along the β stability line. The dependence behavior of the suppression effect was predicted across various mass-target regions, particularly for relatively light-mass targets. For 9Be, the suppression factors exhibited a marked sensitivity to the target nucleus, and no apparent systematic behavior was observed in either the heavy- or light-mass target regions. For 6Li and 7Li, the BNN model predicted less suppression in relatively light-mass targets compared to that observed for heavy-mass targets. Furthermore, the dependence in the light-mass target region was exactly opposite to that in the heavy-mass target region. These conclusions require further experimental and theoretical validation, as well as mechanistic explanations.

Recent developments in fusion and direct reactions with weakly bound nuclei

. Phys. Rept. 596, 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.08.001Physics of exotic nuclei

. Nat. Rev. Phys. 7, 21-37 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-024-00782-5The total reaction cross section of heavy-ion reactions induced by stable and unstable exotic beams: the low-energy regime

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 281 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00277-8Coupled-channels calculations for nuclear reactions: From exotic nuclei to superheavy elements

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 125,Breakup of the proton halo nucleus 8B near barrier energies

. Nat. Commun. 13, 7193 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34767-8Further investigation on the fusion of 6Li with 209Bi target at near-barrier energies

. Chin. Phys. C 48,Fusion and one-neutron stripping process for 6Li + 94Zr system around the Coulomb Barrier

. Chin. Phys. C 48,Complete and imcomplete fusion of 9Be + 169Tm, 187Re at near barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Relating Breakup and Incomplete Fusion of Weakly Bound Nuclei through a Classical Trajectory Model with Stochastic Breakup

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,Puzzle of complete fusion suppression in weakly bound nuclei: a trojan horse effect?

Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Unraveling the reaction mechanisms leading to partial fusion of weakly bound nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Reaction dynamics of weakly bound nuclei at near-barrier energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 834, 147c-150c (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2009.12.025Complete fusion enhancement and suppression of weakly bound nuclei at near barrier energies

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 39,Search for a systematic behavior of the breakup probability in reactions with weakly bound projectiles at energies around the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Angular Momentum and Cross Sections for Fusion with Weakly Bound Nuclei: Breakup, a Coherent Effect

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88,Experimental signatures for distinguishing breakup fusion and transfer in 7Li+165Ho

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Fusion reaction studies for the 6Li + 90Zr system at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Complete fusion in 7Li + 144,152Sm reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 88Non-frozen process of heavy-ion fusion reactions at deep sub-barrier energies

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 132 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01114-xSmall suppression of the complete fusion of the 6Li + 96Zr system at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Origins of imcomplete fusion products and the suppression of complete fusion in reactions of 7Li

, Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Systematic study of breakup effects on complete fusion at energies above the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Search for systematic behavior of incomplete-fusion probability and complete-fusion suppression induced by 9Be on different targets

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Nuclear mass predictions based on Bayesian neural network approach with pairing and shell effects

. Phys. Lett. B 778, 48 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.01.002Nuclear mass predictions with machine learning reaching the accuracy required by r-process studies

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Predictions of nuclear charge radii and physical interpretations based on the naive Bayesian probability classifier

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Nuclear charge radii in Bayesian neural networks revisited

. Phys. Lett. B 838,Predictions of nuclear β-decay half-lives with machine learning and their impact on r -process nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Bayesian evaluation of charge yields of fission fragments of 239U

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Bayesian Evaluation of Incomplete Fission Yields

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Optimizing multilayer Bayesian neural networks for evaluation of fission yields

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Isotopic cross-sections in proton induced spallation reactions based on the Bayesian neural network method

. Chin. Phys. C 44,A Bayesian-Neural-Network Prediction for Fragment Production in Proton Induced Spallation Reaction

. Chin. Phys. C 44,Bayesian evaluation of residual production cross sections in proton-induced nuclear spallation reactions

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 49,Precise machine learning models for fragment production in projectile fragmentation reactions using Bayesian neural networks

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Systematic behavior of fragments in Bayesian neural network models for projectile fragmentation reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Multiple-models predictions for drip line nuclides in projectile fragmentation of 40,48Ca, 58,64Ni, and 78,86Kr at 140 MeV/u

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 155 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01137-4Predictions for (n, 2n) reaction cross section based on a Bayesian neural network approach

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Colloquium: Machine learning in nuclear physics

, Rev. Mod. Phys. 94,Machine learning in nuclear physics at low and intermediate energies

. Science China: Physics, Mechanics, and Astronomy 66,Investigation of 6Li + 64Ni fusion at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Small suppression of the complete fusion of the 6Li + 96Zr system at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Fusion and decay dynamics of 6Li + 120Sn and 7Li + 119Sn reactions across the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Breakup and n -transfer effects on the fusion reactions 6,7Li + 120,119Sn around the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Fusion reaction studies for the 6Li + 124Sn system at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Suppression of complete fusion in the 6Li + 144Sm reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Fusion of 6Li with 152Sm: Role of projectile breakup versus target deformation

. Nucl. Phys. A 874, 14 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2011.10.004Coupling effects on the fusion of 6Li + 154Sm at energies slightly above the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Fusion of 6Li with 159Tb at near barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Fusion and quasi-elastic scattering in the 6,7Li + 197Au systems

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Exploring Fusion at Extreme Sub-Barrier Energies with Weakly Bound Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103,Partial fusion of a weakly bound projectile with heavy target at energies above the Coulomb barrier

. Eur. Phys. J. A 26, 73 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2004-10305-4Effect of breakup on the fusion of 6Li, 7Li, and 9Be with heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Probing the fusion of 7Li with 64Ni at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Investigation of large α production in reactions involving weakly bound 7Li

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Investigation of complete and incomplete fusion in the 7Li + 124Sn reaction near Coulomb barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Influence of projectile alpha- breakup threshold on complete fusion

. Phys. Lett. B 636, 91 (2006) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2006.03.051Role of the cluster structure of 7Li in the dynamics of fragment capture

. Phys. Lett. B 718, 931 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.11.064Fusion of 7Li with 205Tl at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Fusion of the weakly bound projectile 9Be with 89Y

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Study of 9Be fusion in 93Nb near the Coulomb barrier

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 64 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01296-5Fusion cross sections for the 9Be + 124Sn reaction at energies near the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Near-barrier fusion, breakup and scattering for the 9Be + 144Sm system

. Nucl. Phys. A 828, 233 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2009.07.008Complete and incomplete fusion of 9Be + 169Tm,187Re at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Complete and incomplete fusion in the 9Be + 181Ta reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Fusion and one-neutron stripping reactions in the 9Be + 186W system above the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Fusion of the Borromean nucleus 9Be with a 197Au target at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Suppression of complete fusion due to breakup in the reactions 10,11B + 209Bi

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Hindrance of complete fusion in the 8Li + 208Pb system at above-barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Chun-Wang Ma is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.