Introduction

Multi-nucleon transfer (MNT) is considered a promising method for the production of neutron-rich heavy or superheavy nuclei, and has been studied in the field of low-energy nuclear reactions for several decades [1, 2]. Despite significant theoretical [3-7] and experimental [8-12] efforts, the mechanism of MNT remains unclear because of complex phenomena involving the transfer and/or transport of numerous nucleons.

Owing to the intricacies of the reaction mechanisms involved, the measurement of MNT products requires improved precision, placing higher demands on the equipment: i) good mass (A) and charge (Z) identifications for validation of various reaction channels; ii) a large acceptance for the detection of rare products that are far from the projectile or target, considering the steep decrease in cross-sections with an increasing number of transferred nucleons; iii) a good energy resolution for the distinction of a large number of energy levels populated in a specific reaction channel.

Several detection techniques have been developed for particle identification, such as measurement of time-of-flight (ToF) with a known flight distance. The relative uncertainty was drastically reduced with a long flight distance. As a mature method, the E-ToF technique, which measures energy and ToF simultaneously, has been widely used in studies of transfer reactions at energies near the Coulomb barrier [13]. The mass resolution, determined by energy and ToF measurements, reached σ = 0.2 amu. For binary reactions, the kinematic coincidence technique is an effective method for enhancing the energy and mass resolution, such as simultaneous ToF measurements of projectile-like ions and correlated scattering angles [14].

To further investigate the MNT reaction mechanism, a ToF spectrometer for heavy-ion reactions, called HiToF, was constructed at the HI-13 tandem accelerator of the Beijing Tandem Accelerator National Laboratory. Its design resembles that of PISOLO [15] at Laboratori Nazionali di Legnaro, but with a focusing system that includes a quadrupole triplet lens. The maximum solid angle covered by HiToF reached 20 msr. The HiToF is equipped with two micro-channel-plate detectors dedicated to time-of-flight measurements and a specially designed ionization chamber for energy measurement and charge identification on the focal plane. A test experiment has recently been conducted successfully, laying a solid foundation for further investigation of multi-nucleon transfer reactions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the detection system and ion optical elements. Section 3 presents the recent results of the 32S + 90,94Zr test experiment and Sect. 4 summarizes the results and our conclusions.

Spectrometer

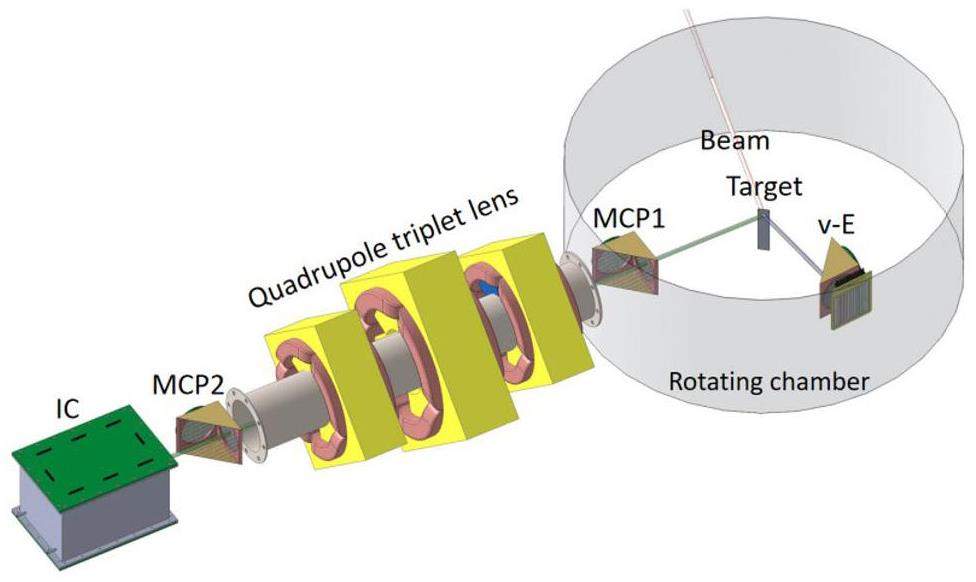

The HiToF spectrometer consists mainly of an adjustable detection system and an ion-optical system. It was connected to a steal-tape sealed rotating chamber with a diameter of 40 cm. The spectrometer can rotate with the chamber as the center, covering an angular range from -40° to 160°. A schematic of the spectrometer is shown in Fig. 1.

The detection system

The detection system includes a ToF measurement that mainly uses two microchannel plates (MCP1 and MCP2) and an energy measurement using a multisampling position-sensitive ionization chamber (IC) installed at the focal plane. A v-E detector, including an MCP and a double-sided silicon strip detector (DSSD) [16-18] is also installed at the complementary angle in the rotating chamber for the velocity and energy measurements of target-like ions.

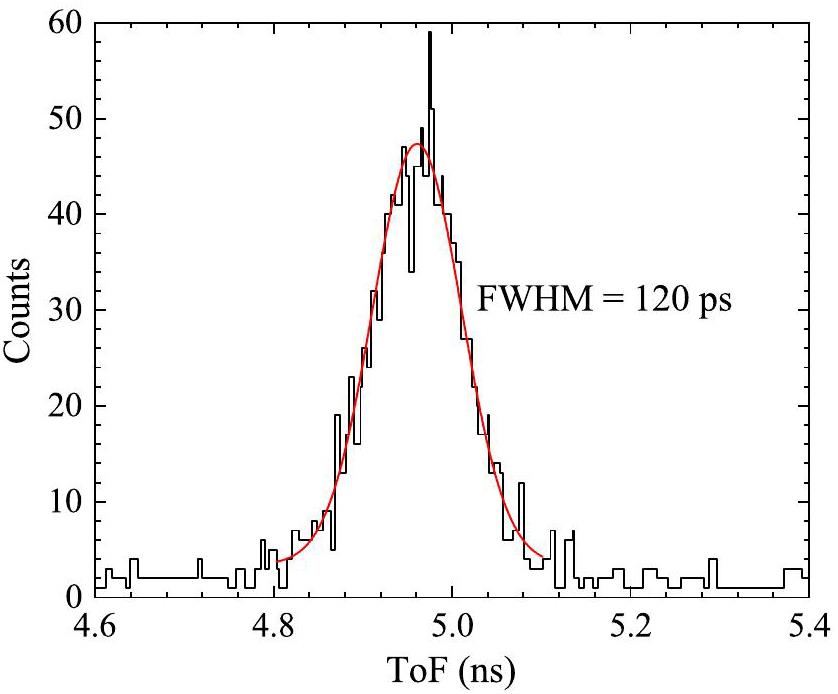

ToF measurement consists of two transmission-type detectors that have good timing properties, such as timing detectors made of microchannel plates [19-21]. Two timing detectors, each using a pair of microchannel plates with a diameter of 45 mm, were installed to provide the start and stop signals along a flight path. The stop detector was placed at a distance of 40 cm from the focal plane. In the test experiment described in Section 3, the start detector was set 40 cm from the target. However, the start detector can be placed closer to the targets to reduce relative inaccuracy with a longer flight distance. Note that both MCP detectors, which define the geometric solid angle for the entire spectrometer, can be replaced with a position-sensitive MCP [22, 23] to provide position information such that the track of the projectile-like ions after magnetic focusing can be reconstructed. The energy resolution can be further improved by using the ToF information of a specific particle. Figure 2 shows the result of the offline test at a short flight distance of 5 mm using a standard α source consisting of the isotope 241Am. The typical timing resolution was 120 ps.

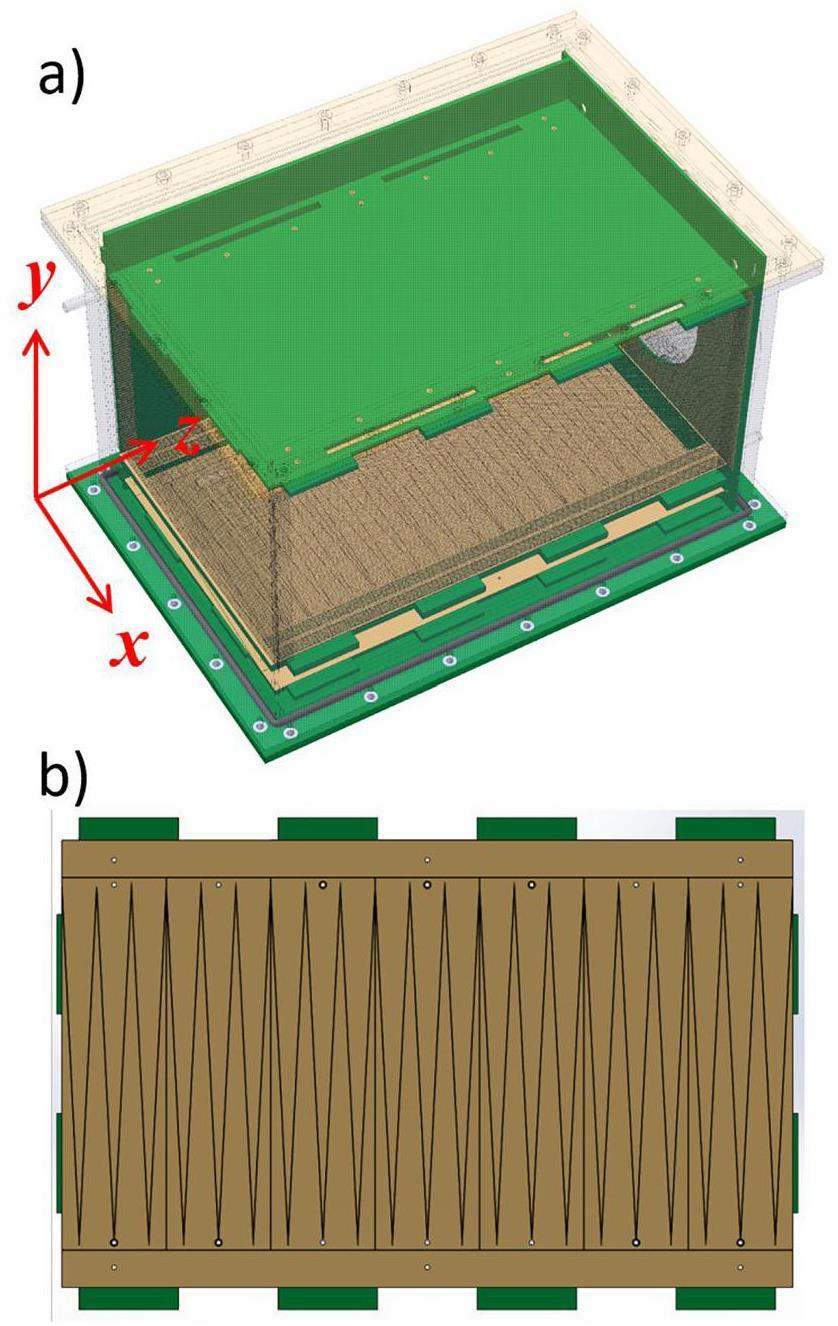

To improve the energy resolution for the experimental demands, a special IC with a transverse electric field was designed. The special design of the ionization chamber refers to conventional ionization chambers [24-27] and time projection chammbers [28-32]. The IC was constructed from printed circuit boards with dimensions of 300 mm × 200 mm × 200 mm, located at the focal plane. A length of 300 mm provided a broad energy range for Z identification. The circular entrance window of the IC, which is 100 mm in diameter, is positioned 18.3 cm away from MCP2 and is equipped with a 2-μm thick mylar foil. The large area of the entrance window provided a large acceptance for energy measurement. The grid consists of gold-plated tungsten wires with a radius of 0.08 mm, soldered 1 mm apart. The distance from the grid to the anode was 22 mm, and the spacing between the grid and the cathode was 136 mm. 67 equipotential rectangle shaped loop electrodes were evenly distributed along the plate with resistors of 1 MΩ to connect two adjacent electrodes.

This IC is designed with three-dimensional position resolution capabilities, allowing for precise ΔE-E and position detection. The energy resolution can be improved by the track reconstruction provided by the IC. Figure 3 shows the design details.

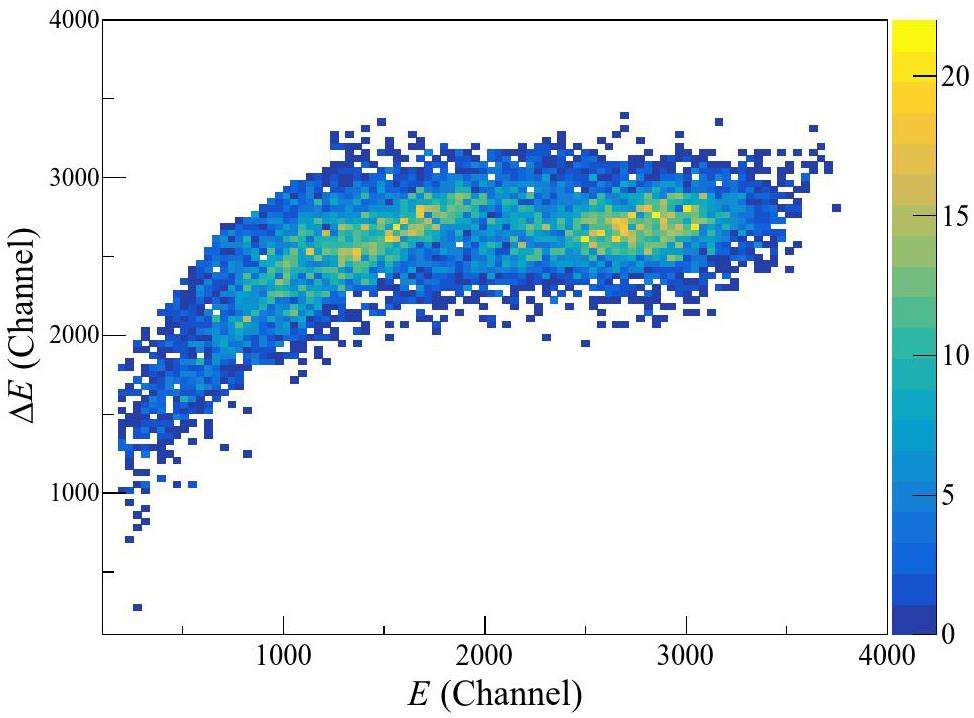

The anode of the IC is divided into seven sections, which can provide not only the energy loss ΔE and residual energy ER but also the trajectory (z-direction) of the entrance ion. Each section was divided into two wedge-shaped parts to determine the x-position using the charge-division method. The y-position is provided by the drift-time difference between the anode and cathode. The timing signal of MCP2 was also used as a reference for drift-time measurement. Typical x, y, and z position resolutions are approximately 1.0, 0.5 and 2.0 mm, respectively, primarily depending on the properties of the entrance ion, working gas, and high voltage supplied. A smart preamplifier (SPA) [33] was used for the signal readout of the IC. Figure 4 shows the results of the offline test using fission source 252Cf. The fission fragments of this source have a continuous energy spectrum mainly distributed around 105Mo and 140Xe. The energies of heavier fragments are typically lower than the Bragg peak energy; hence, the corresponding ΔE-E spectrum exhibits an upward trend. Lighter fragments with energies over the energy of the Bragg peak tend to be flatter in the spectrum. The working gas was 99.9% pure propane, at a pressure of 30 Torr. The operating voltages were 110 V for the anode and -308 V for the cathode.

Practical flight distances are constrained for many technical reasons, particularly solid angle considerations [34]. Because of optical focusing by the quadrupole triplet lens, the real flight distance of the projectile-like ions may deviate from the designated length between the start and stop detectors. For this reason, the x-y position information at the focal plane and the trajectory of the entrance ion provided by the IC can be used to correct the flight distance so that the relative inaccuracy of the ToF measurement is partly reduced.

The ion-optical system

The ion-optical system is designed to use a quadrupole triplet lens (Q1-Q2-Q3) to transport the entrance ions to the focal plane, which is approximately 2.70 m away from the target. Three quadrupole magnets Q1, Q2 and Q3 are equipped at 0.85, 1.35, 1.85 m from the target. The Q1 and Q3 quadrupoles have the same structure with an aperture of Φape = 100 mm and a maximum magnetic flux density of Bmax = 0.373 T. The Q2 quadrupole is located in the middle, with a reverse-phase current and an aperture Φape = 130 mm and a maximum magnetic flux density of Bmax = 0.636 T. Ions with a magnetic rigidity up to

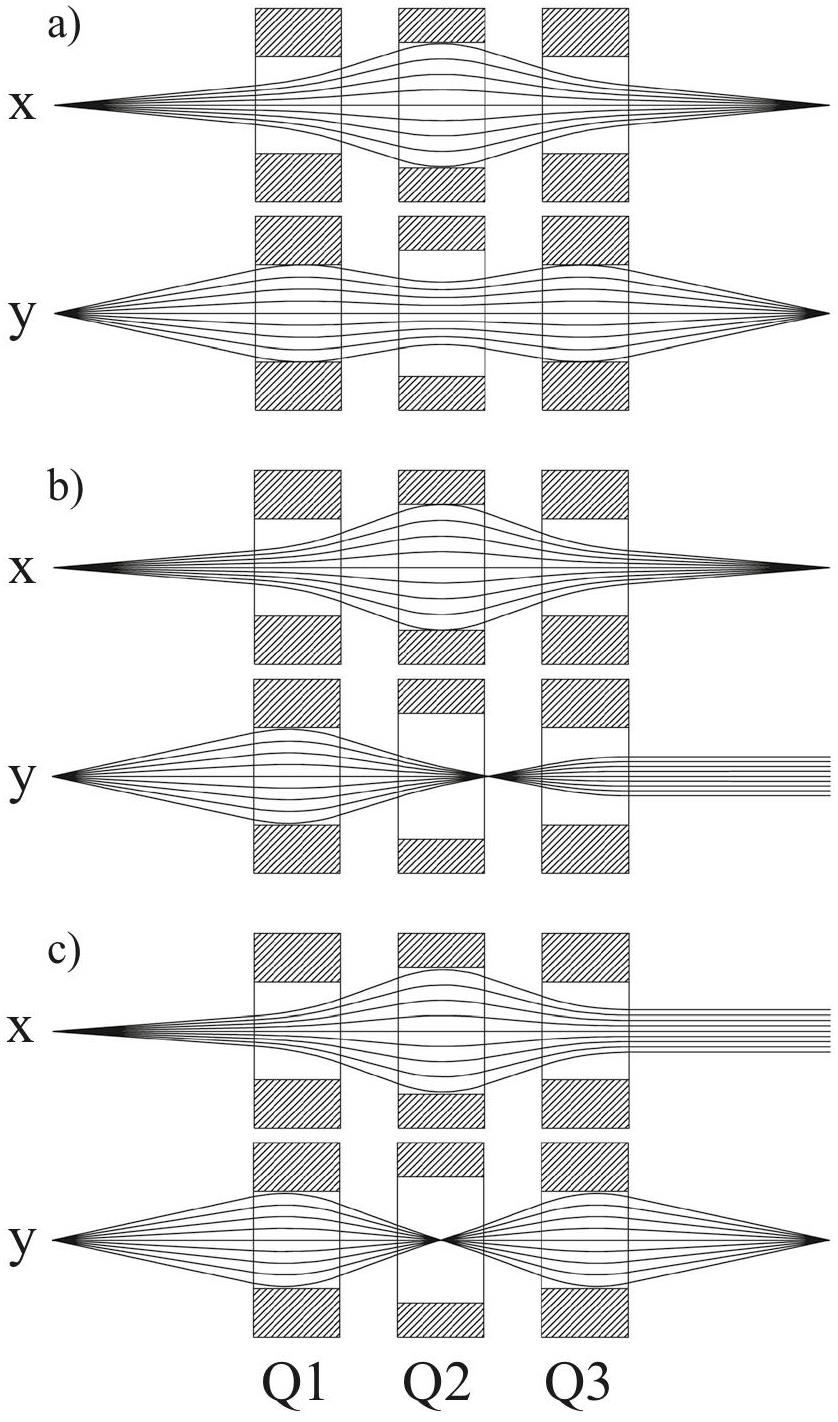

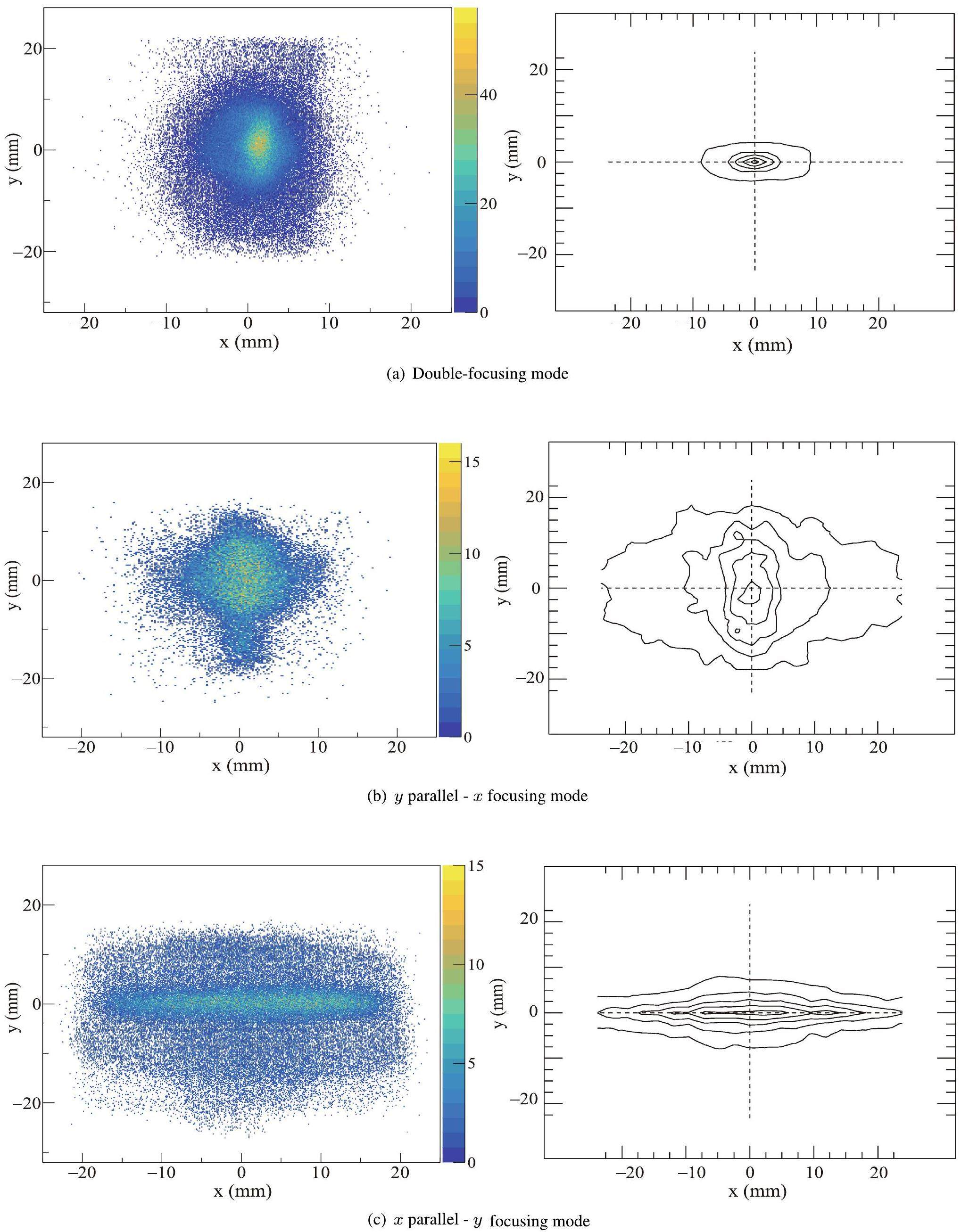

The HiToF spectrometer can be operated in three modes: a) both x and y focusing (double focusing), b) x focusing and y parallel, and c) x parallel and y focusing. The double-focusing operation mode, which provides the maximum solid angle, enhances the transmission efficiency, and mode c) offers a method for preserving the scattering angle information by focusing only perpendicular to the reaction plane [13, 34]. The solid angle of the spectrometer was confirmed by measuring the yield of all the quasi-elastic events on the focal plane as a function of the quadrupole field.

The corresponding ion trajectories calculated using GICOSY [35] are shown in Fig. 5. The setting of the quadrupole triplet lens is primarily determined by the mass, energy, and charge state of the entrance ion.

Performance of HiToF

An experiment on 32S + 90,94Zr at ELab = 135 MeV (approximately 15% above the Coulomb barrier) was conducted on the spectrometer to test its performance. The two targets consisted of 90ZrO2 and 94ZrO2 evaporated onto 25 μg/cm2 carbon backings with thicknesses of 104 μg/cm2 and 120 μg/cm2, respectively. The focusing performance of the magnets, performance of the detection system, and particle identification capability were tested in the experiment.

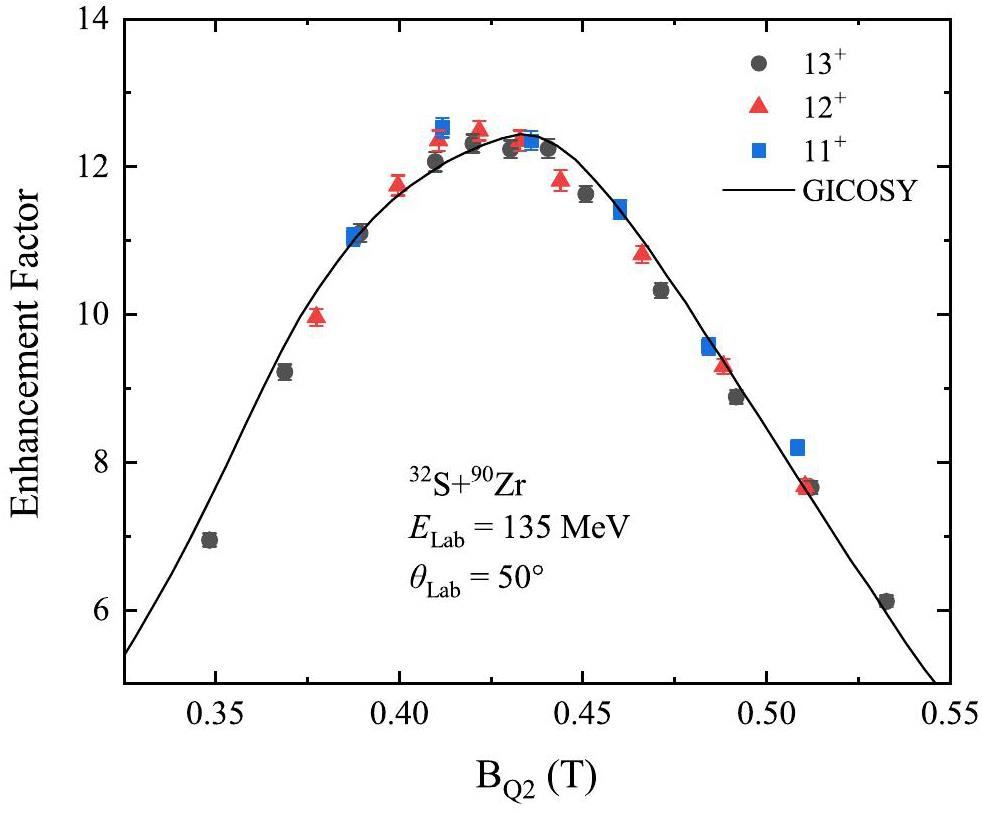

The transmission efficiencies were determined by measuring the product ions on the focal plane with and without a magnetic field. The magnetic fields for maximum transmission efficiencies B0 were set based on GICOSY calculations. Several magnetic fields close to B0 are also tested. As shown in Fig. 6, the enhancement factors of the yield ratios with and without quadrupole fields for the charge states of 11+, 12+, and 13+ in the double-focusing operating mode are in good agreement with the GICOSY calculations. In this case, the magnetic field setting for the maximum transmission efficiency is BQ2/BQ1 = 1.678, with BQ1 = BQ3.

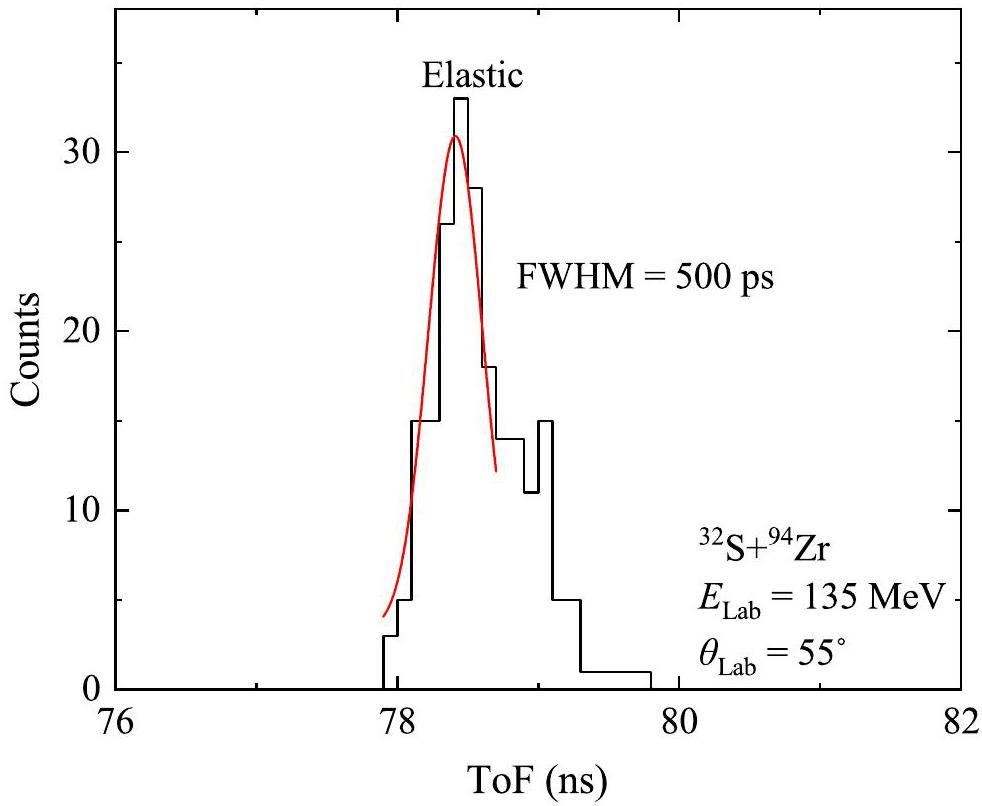

In the experiment, the ToF was measured between the two MCP detectors at a flight distance of 1.9 m. ToF measurement is influenced by a number of factors such as spectrometer isochronism, target thickness inhomogeneity, energy straggling in the target, imperfect software corrections, and finite resolutions of the ToF detectors [18]. As shown in Fig. 7, the FWHM of the main peak of particle 32S without a magnetic field was 500 ps. The ToF of the focused ions was also affected by the uncertainty in the flight distance owing to the large solid angle.

Different magnetic fields are required for particles of different energies, masses, and charge states. In addition, three operating modes of focus were tested. [Double-focusing mode]

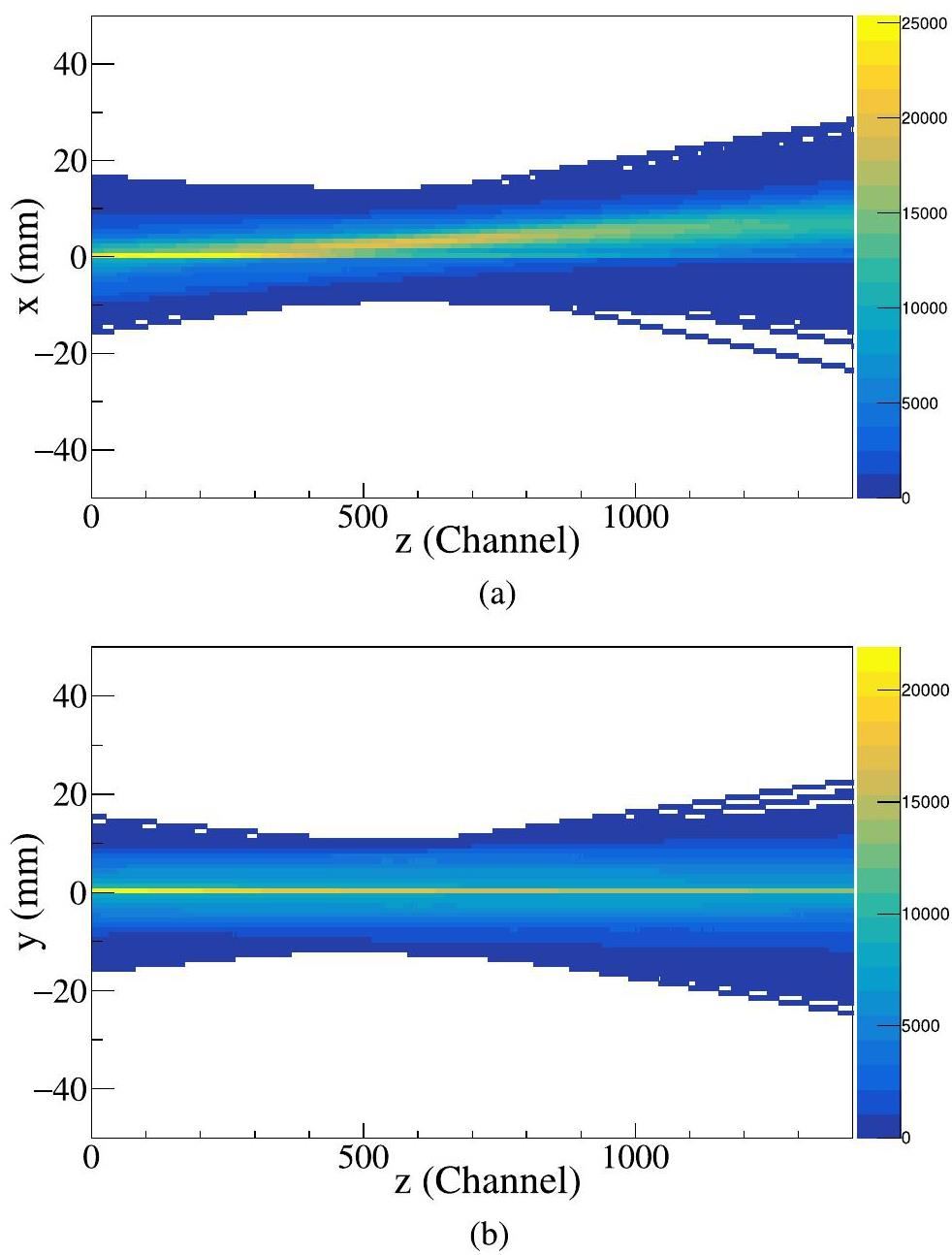

For the test experiment, we redistributed the seven sections of the IC anode into three parts: two, two, and three sections. Propane was used as the working gas for ionization within the pressure range of 50–70 Torr. In Fig. 8, we show the tracking results provided by the IC, which are useful for more precise energy detection. Using the method described in Sect. 2, the images of the x-y distributions on the focal plane for the three focusing modes are shown in Fig. 9, which are consistent with the distribution results calculated by GICOSY. In this case, the magnetic field settings BQ2/BQ1 of different focusing modes (a), (b), and (c) are 1.678, 1.32, and 1.577, respectively, with BQ1 = BQ3. The results in Fig. 9 verify the position resolution capability of the IC and focusing performance of the quadrupole triplet lens.

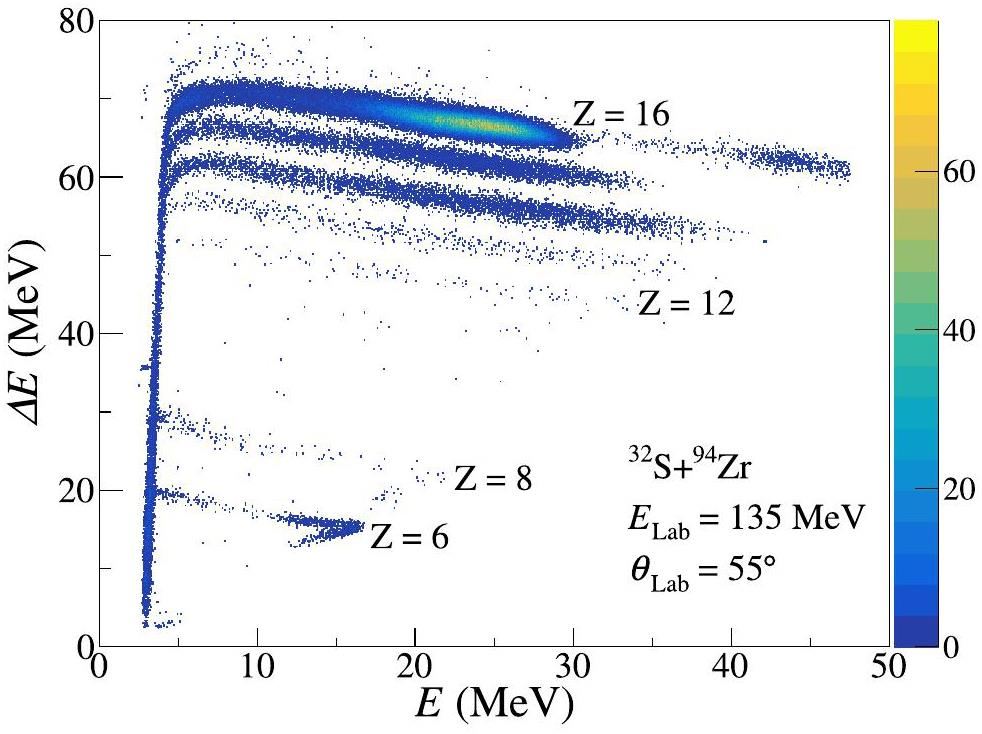

The large effective solid angle and good charge and mass resolution provide opportunities for measuring the cross sections of weak reaction channels. The ΔE-E measurement, shown in Fig. 10, precisely identifies different elements. The populated product isotopes at Ebeam = 135 MeV extended from Z = 12 (4 proton stripping) to Z = 16. The lower-energy particles observed were elements C (Z = 6) and O (Z = 8) on the target backings.

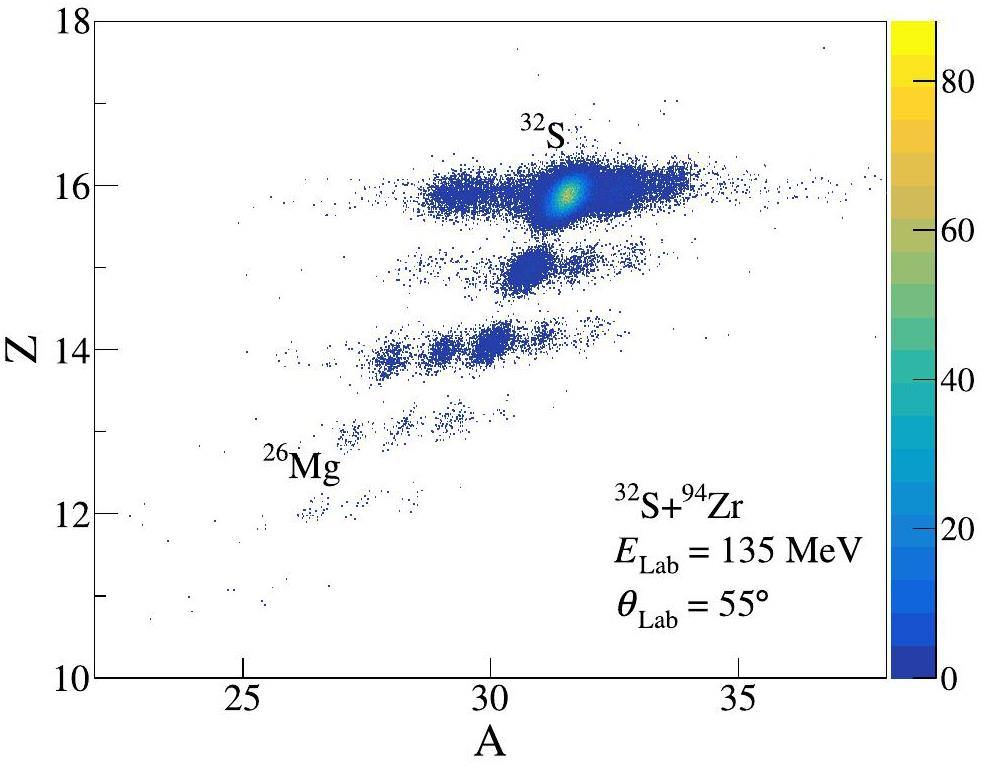

The resolution of the HiToF spectrometer allowed for the unambiguous identification of numerous projectile-like reaction products. Two-dimensional mass-charge spectra were obtained for the reaction 32S + 90,94Zr at θLab = 55° (close to the grazing angle), as shown in Fig. 11. Several reaction channels, including proton stripping, neutron stripping, and neutron pick-up reactions, were measured. The reaction products were clearly identified up to the pick-up of two neutrons and stripping of four protons. Rare events belonging to the -5p channels were also observed.

In the reaction system, the IC provides nuclear charge resolution

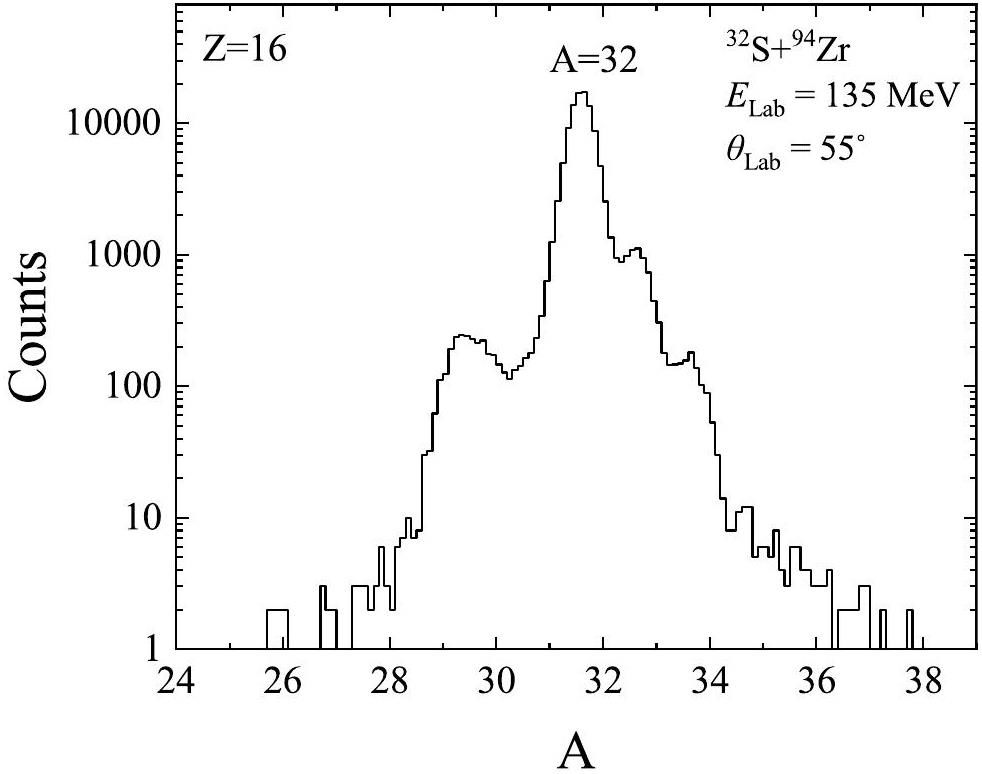

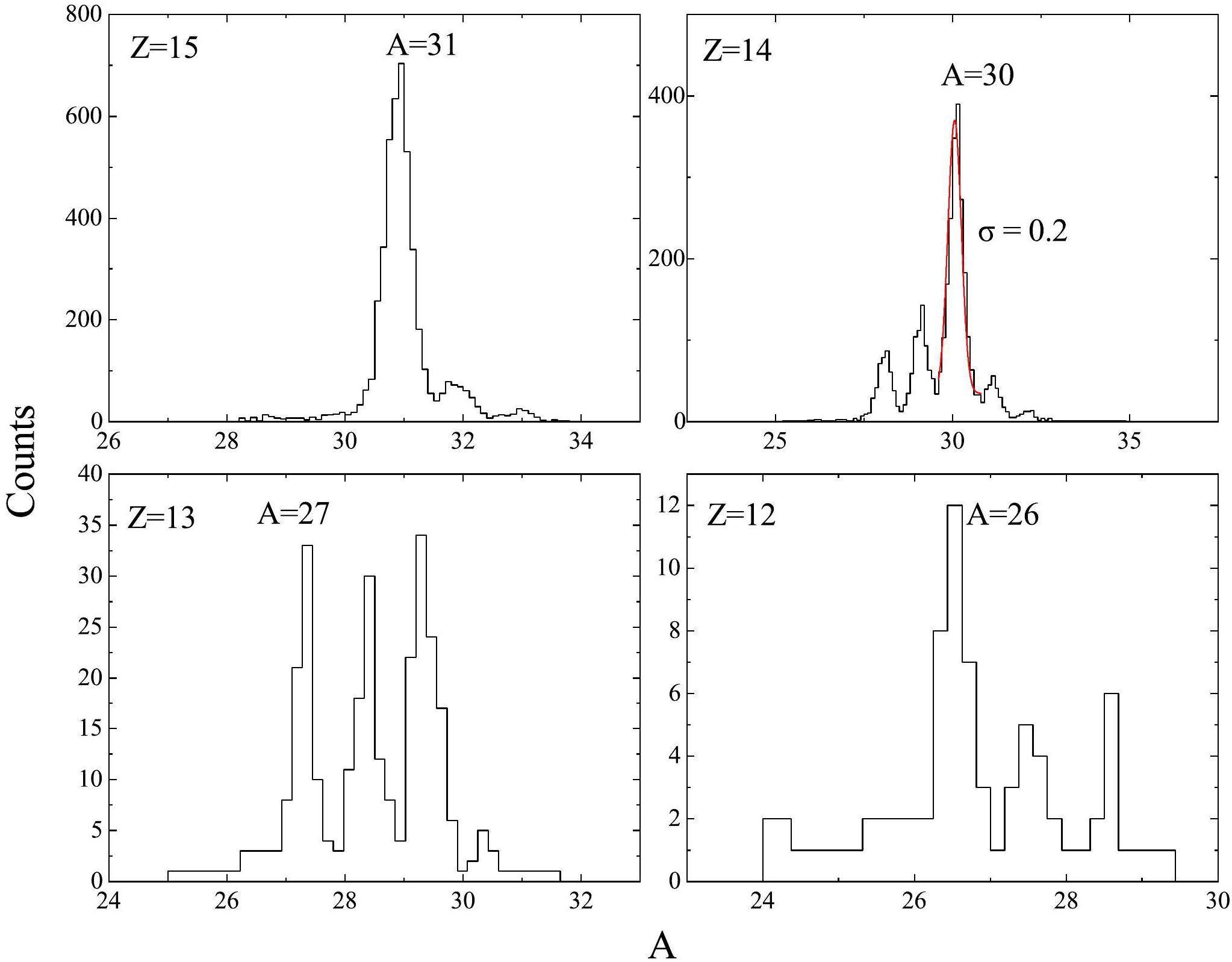

Mass spectra for various Z selections are shown in Figs. 12 and 13. For Z = 16, an exponential decline in ion yield with an increase in the number of transferred neutrons was observed. In Fig. 13, reaction products from Z = 12 to Z = 15 were observed. The peaks with Z = 12 and A= 26 correspond to the -4p-2n channel.

Summary and outlook

According to the test experiment, the HiToF spectrometer, a simple and high-precision equipment that can provide a large solid angle of 20 msr and allow a good resolution for mass, energy, and position, was adequately prepared to study multi-nucleon transfer reactions. The resolutions of mass, charge, and position are σ = 0.2 amu,

In the near future, improved IC and track reconstruction via the timing detector of ToF measurement and IC will be combined to enhance the energy resolution with a more precise magnetic field. An angular distribution with higher precision is obtained via the coincidence of IC for the measurement of projectile-like ions and v-E detectors for the measurement of target-like ions.

In the field of low-energy nuclear reactions, HiToF provides good opportunities for the experimental study of reaction mechanisms. HiToF’s robust particle identification capability is crucial for identifying reaction products and channels in MNT processes. Owing to the broad detection range of the spectrometer, a large number of reaction channels can be observed. This facilitated a more profound understanding of the reaction mechanism. Superior performance of the device is required for frontiers; therefore, efforts will be made to improve the detection system, such as enhancement of energy and position resolution.

The study of multi-nucleon transfer reactions for synthesis of new heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 19, 693 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477122060085Nucleosynthesis in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Europ. Phys. J. A 58, 114 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00771-1Mechanism of multinucleon transfer reaction based on the GRAZING model and DNS model

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 44,Production cross sections for exotic nuclei with multinucleon transfer reactions

. Front. Phys. 13,Production of heavy neutron-rich nuclei with radioactive beams in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 110 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0266-zTheoretical study of multinucleon transfer reactions by coupling the Langevin dynamics iteratively with the master equation

. Phys. Rev. C 109,New model based on coupling the Master and Langevin equations in the study of multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 849,Multinucleon transfer processes in 64Ni+238U

. Phys. Rev. C 59, 261 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.261Discovery of new isotope 241U and systematic high-precision atomic mass measurements of neutron-rich Pa-Pu nuclei produced via multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Production of heavy trans-target nuclei in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Transfer reactions in 206Pb+118Sn: From quasielastic to deep-inelastic processes

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Multinucleon transfer processes in heavy-ion reactions

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 36,Time of flight detectors for heavy ions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 162, 531 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(79)90731-6A kinematic coincidence technique for the study of low-energy heavy-ion reactions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 297, 461 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(90)91330-EThe time-of-flight spectrometer for heavy ions PISOLO

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 454, 306 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(00)00482-4Characterization of CIAE developed double-sided silicon strip detector for charged particles

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 73 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0406-0Development and test of double-sided silicon strip detector

. At. Energy Sci. Technol. (in Chinese) 49, 336 (2015). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2015.49.02.0336The effects of beam drifts on elastic scattering measured by the large solid-angle covered detector array

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 14 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00854-6A compact time-zero detector for mass identification of heavy ions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 193, 499 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(82)90242-7Improvement of the detection efficiency of a time-of-flight detector for superheavy element search

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 960,Detection efficiency evaluation for a large area neutron sensitive microchannel plate detector

. Chinese Phys. C 40,A position-sensitive transmission time detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 171, 71-74 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(80)90011-7Electrostatic-lenses position-sensitive TOF MCP detector for beam diagnostics and new scheme for mass measurements at HIAF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 152 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0676-1A position-sensitive twin ionization chamber for fission fragment and prompt neutron correlation experiments

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 830, 366 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.06.002A position-sensitive ionization chamber

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 124, 509 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(75)90603-5A large area position-sensitive ionization chamber for heavy-ion-induced reaction studies

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 495, 121 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(02)01579-6MITA: A Multilayer Ionization-chamber Telescope Array for low-energy reactions with exotic nuclei

. Europ. Phys. J. A 55, 87 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12765-7Commissioning of the Active-Target Time Projection Chamber

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 875, 65-79 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.09.013The time projection chamber

. Phys. Today 31, 46-53 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2994775A time projection chamber for the three-dimensional reconstruction of two-proton radioactivity events

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 613, 65-78 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2009.10.140Performance of a small AT-TPC prototype

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0437-6Low energy nuclear physics with active targets and time projection chambers

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 114,Compact 16-channel integrated charge-sensitive preamplifier module for silicon strip detectors

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 48 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00755-0Design study of a magnetically focussed time-of-flight spectrometer for heavy ions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 130, 125 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(75)90164-0COSY 5.0 - The fifth order code for corpuscular optical systems

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 258, 402 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(87)90920-X.The authors declare that they have no competing interests.