Introduction

There are 288 naturally existing nuclei on earth, with 238U being the heaviest among them. Transuranium nuclei, with atomic numbers greater than 92, can only be produced through nuclear reactions [1-3]. The first transuranium nucleus, 239Np was discovered in 1940 among the fission products resulting from bombardment of 238U with thermal neutrons [4]. Since then, nuclear physicists have successfully synthesized 26 transuranium elements artificially by utilizing several types of nuclear reactions. Among these artificial nuclei, transactinide nuclei with Z ≥104 are known as superheavy nuclei (SHNs) [5-7]. These nuclei are located in the northeast region of the nuclear chart and exhibit extreme instability and short half-lives. Nevertheless, the synthesis and study of SHNs are crucial for advancing our understanding of the fundamental properties of nuclear forces, validating nuclear structural models, and extending the periodic table of elements.

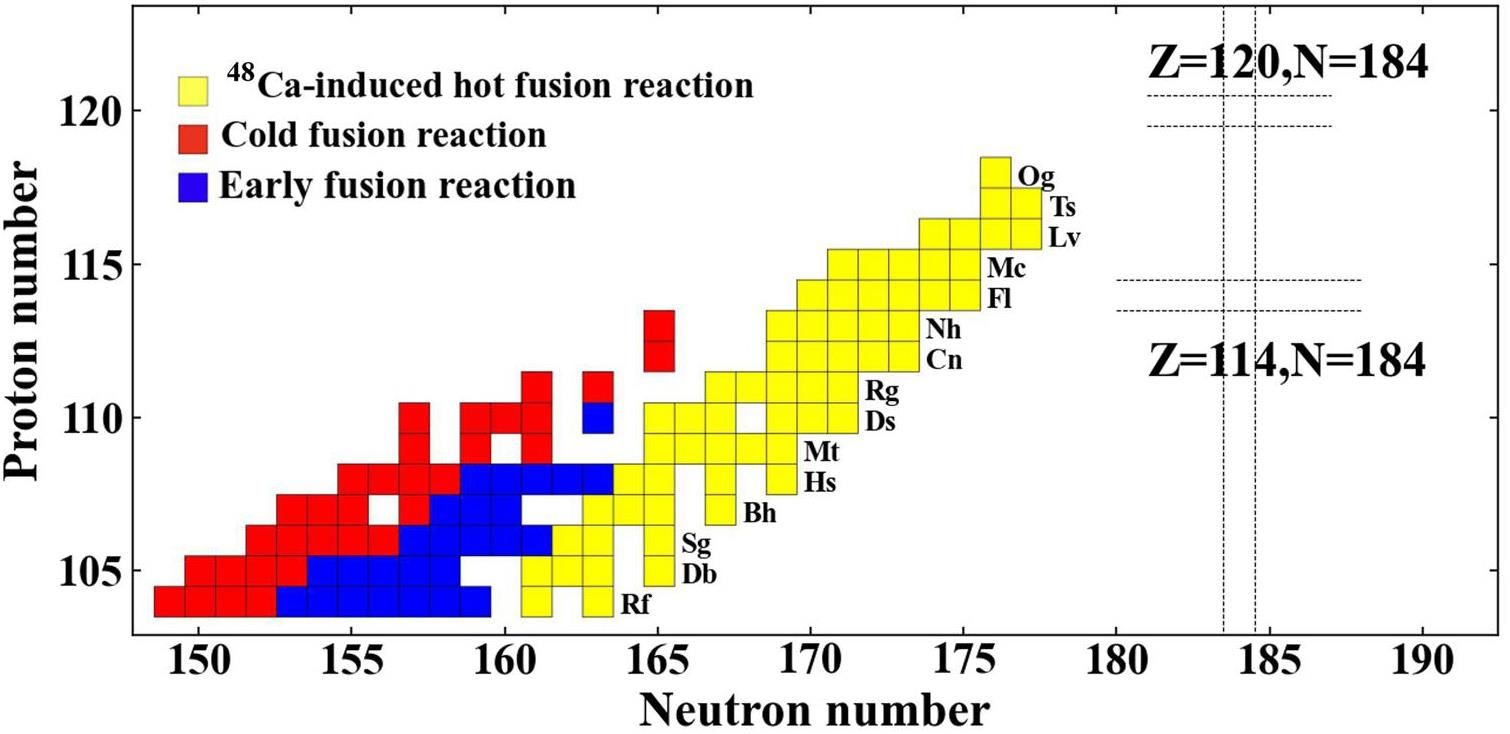

Although the SHN region lies at the limits of Coulomb stability, the shell structure effects can influence the fission barrier, thereby contributing to the existence of SHNs. Following the approach proposed by Strutinsky, which involves introducing shell corrections to the liquid-drop model, an “island of stability” at Z = 114 and N = 184 was predicted separately by Sobiczewski et al. and Meldner [8-12]. Further predictions from various microscopic approaches, such as the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock and relativistic mean-field methods, suggest that this “island of stability” could be located at Z = 114, 120, 124 or 126 and N = 172 or 184 [13-15, 16-20]. These theoretical predictions are supported by the observed increase in α-decay half-lives of isotopes with increasing neutron number [8, 21].

The primary mechanism for synthesizing SHNs involves fusion reactions using stable beams and long-lived targets. Early fusion reactions utilizing lighter projectiles and actinide targets were selected to produce superheavy elements (SHEs) with Z = 93 - 106 at LBNL and JINR [22-26]. Subsequent advancements in cold fusion reactions employing 208Pb or 209Bi targets facilitated the synthesis of SHEs with Z = 107 - 113 at GSI and RIKEN [27, 28]. In contrast, hot fusion reactions using 48Ca beams and actinide targets conducted in JINR at Dubna led to the successful synthesis of SHEs with Z = 114 - 118 [29-33]. Currently, the synthesis of new SHEs with Z = 119 - 122 represents a highly competitive frontier in nuclear research.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of research on the synthesis of SHNs, focusing on both experimental accomplishments and theoretical advancements. We discuss the latest achievements and breakthroughs in the synthesis of SHN, experimental facilities, and theoretical methods employed. Furthermore, this review discusses the challenges encountered in synthesizing new SHN and explores the potential directions for future research.

This article is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we introduce the discovered SHN and the methods used for their synthesis. Section 3 covers the current experimental facilities, including both existing and under-construction accelerators and separators. In Sect. 4, we discuss the widely applied microscopic and phenomenological models used in theoretical predictions. Section 5 reviews the latest experimental and theoretical advancements in the synthesis of new SHEs. Section 6 addresses the current experimental challenges in synthesizing new SHN and explores potential future developments. Finally, Section 7 provides a summary of this study.

The discovery of superheavy nuclei

Early fusion reactions with C, N, O, Ne, Mg and Ar beams

There are 3386 discovered nuclei of 118 known elements, including 119 artificial SHNs [34]. The discovery of superheavy isotopes began in 1969 at Berkeley, where the fusion reactions 12,13C + 249Cf led to the identification of 257-259Rf [22]. By changing the projectile into 15N and 18O, the elements with Z = 105 and 106 were also synthesized [23, 24]. JINR also independently produced the 104th and 105th elements via reactions 22Ne + 242Pu, 243Am [25, 26]. Additionally, based on the actinide targets 248Cm and 249Bk, researchers have successfully synthesized new superheavy nuclei 260-262Rf and 262Db [35, 36].

In 2000, the reaction 22Ne + 241Am was investigated at the Institute of Modern Physics (IMP) in China, leading to the discovery of 259Db [37]. In 2006, using the reaction 26Mg + 248Cm, 270,271Hs were produced at GSI, with 266,267Sg identified in the α-decay descendants [38, 39]. Most recently, in 2024, JINR researchers employed the reaction 40Ar + 238U, resulting in the synthesis of 273Ds [40]. Experimental results suggest that more asymmetric reaction systems can enhance both the fusion probability and evaporation residue (ER) cross sections when forming the same compound nucleus. For instance, in the 5n-emission channel leading to the formation of 273Ds, the ER cross section for the reaction 34S + 244Pu is 0.4 pb [41], while for the reaction 40Ar + 238U, it is 0.18 pb [40]. Similarly, the fusion cross sections for producing 232Cm and 274Hs via reactions 35Cl + 197Au and 26Mg + 248Cm are higher than those produced through reactions 40Ca + 192Os and 36S + 238U [42-46].

In the early stages of fusion reactions involving extremely asymmetric reaction partners, the formed compound nuclei possess high excitation energies, requiring the evaporation of three to five neutrons to reach the ground state. However, strong competition from fission during the de-excitation process significantly suppressed the yield of the desired nuclei. The limited atomic number of the light projectiles also constrains the atomic number of the SHE that can be synthesized experimentally. Therefore, there is a need to explore new reaction mechanisms to improve the synthesis efficiency of new elements.

Superheavy nuclei produced by cold fusion reactions

In 1974, researchers at JINR explored an alternative reaction mechanism to synthesize new SHNs [47]. By employing 206-208Pb targets and 50Ti and 54Cr projectiles, they discovered new isotopes of 255,256Rf and 260Sg [48, 49]. Because of the reduced mass asymmetry of these reaction systems and the high binding energies of the reaction partners, the excitation energies of the formed compound nuclei were suppressed. This resulted in a de-excitation process requiring the emission of only one or two neutrons, thereby reducing competition from fission. Compared to reactions involving actinide targets and light projectiles, this new reaction mechanism exhibited enhanced ER cross sections. This approach, characterized by low excitation energy and fewer neutron emission, is referred to as “cold fusion reaction”.

Another advantage of cold fusion reactions is that the commonly used 208Pb and 209Bi targets are more readily available in large quantities than actinide targets. In addition, the experimental conditions can be simplified as they are stable target nuclei. Therefore, GSI in Germany had selected this reaction mechanism to investigate the synthesis of new SHEs. In 1981, researchers at GSI managed to synthesize element with Z = 107 via the reaction 54Cr + 209Bi → 262Bh + n [50]. Following this, through the reactions 58Fe+208Pb→265Hs+n, 58Fe+209Bi→266Mt+n, 62,64Ni+208Pb→269,271Ds+n, 70Zn+208Pb→277Cn+n, the SHEs with Z = 108-112 were successfully synthesized [51-55].

Based on the cold fusion reaction, dozens of superheavy nuclei with Z = 104–110 were also synthesized in the GSI [54, 56-61]. In addition, Berkely synthesized 267Ds in the 1n-emission channel of the reaction 59Co+209Bi [62]. The synthesis of 271Ds via the reaction 64Ni+208Pb was also studied by researchers at IMP [63].

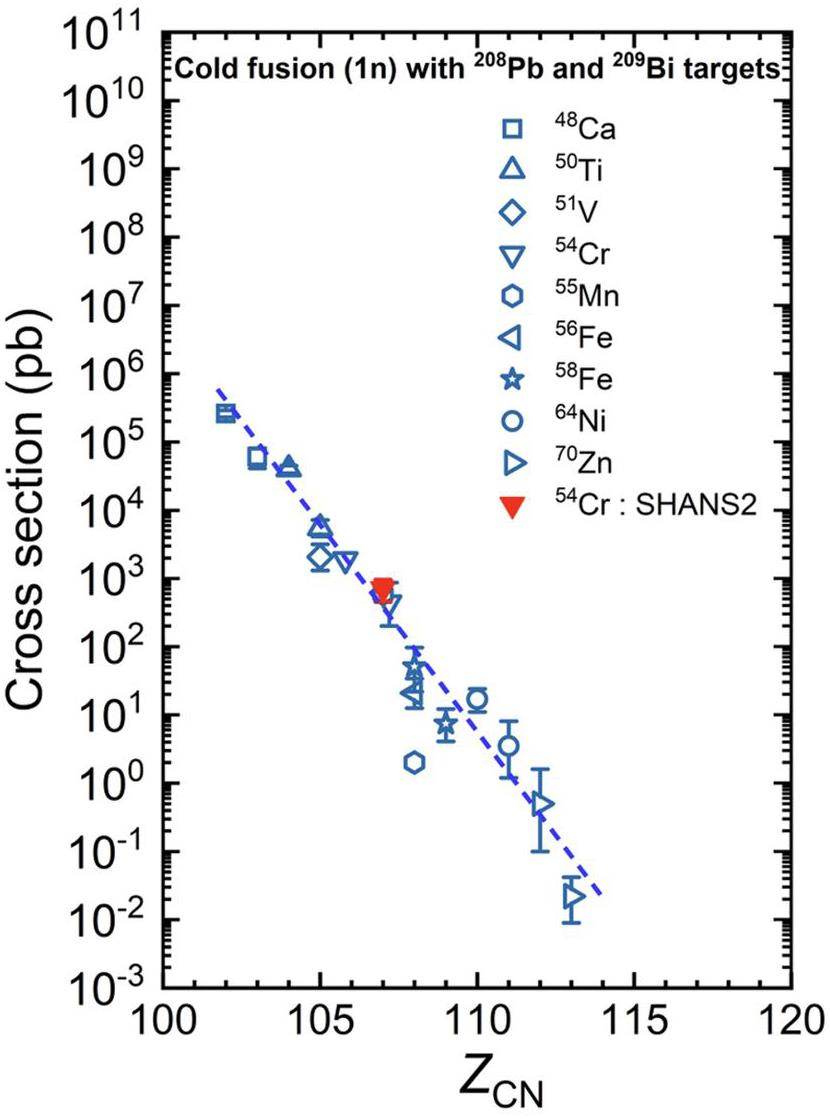

In 2004, RIKEN employed the reaction 70Zn + 209Bi and successfully synthesized the element with Z = 113 in the 1n-evaporation channel [27]. However, the ER cross section was only 0.03 pb, which is 107 times smaller than the ER cross section for synthesizing Bohrium. As shown in Fig. 1, there is an exponentially decreasing trend in the ER cross sections as the proton number of the formed compound nucleus increases [64]. This decrease is primarily due to the strong hindrance to the fusion of colliding nuclei caused by increasing Coulomb repulsion [65], as well as the deviation of the deformed subshell with Z = 108 and N = 162 [66, 67]. The synthesis of SHN with

Superheavy nuclei produced by 48Ca-induced hot fusion reactions

To reduce the hindrance caused by Coulomb repulsion, researchers at JINR explored combinations of 48Ca projectile and actinide targets. The selection of 48Ca as a projectile is due to its doubly magic nature with a high binding energy, which enhances fusion probabilities and lowers the excitation energy of the formed compound nuclei. Moreover, the high neutron excess of 48Ca contributes to the formation of neutron-rich compound nuclei. These neutron-rich nuclei tend to exhibit greater stability due to the reduced Coulomb repulsion among protons, a factor that is particularly crucial for superheavy elements, which possess large atomic numbers and therefore significant Coulomb forces acting against their stability.

In Table 1, the characteristics of the three types of fusion reaction are presented. Although the excitation energies in hot fusion reactions are higher than those in cold fusion reactions, leading to a lower survival probability of compound nuclei, the fusion probability in hot fusion reactions is enhanced by the high mass asymmetry of the reaction systems. Additionally, the neutron-rich projectile 48Ca results in the formation of compound nuclei with a higher neutron excess. The increased neutron-to-proton ratio in these compound nuclei enhanced their binding energy and stability.

| Aspect | Early fusion reactions | Cold fusion reactions | Hot fusion reactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Projectile | Light nuclei with Z=6–18 | Heavy nuclei with Z=22–30 | Double magic nucleus 48Ca |

| Target | Actinide targets | Pb or Bi targets | Actinide targets |

| Excitation energy | Higher, leading to 3–5 neutron emission | Lower, leading to 1–2 neutron emission | Higher, leading to 3–5 neutron emission |

| ER cross section range | From microbarn range to picobarn range | From microbarn range to femtobarn range | Picobarn range |

| Character of products | Neutron-deficient, Z=104–110, less stable | Neutron-deficient, Z=104–113, less stable | Neutron-rich, Z=104–118, potentially more stable |

| Successful synthesis | Elements 104 to 106 | Elements 107 to 113 | Elements 114 to 118 |

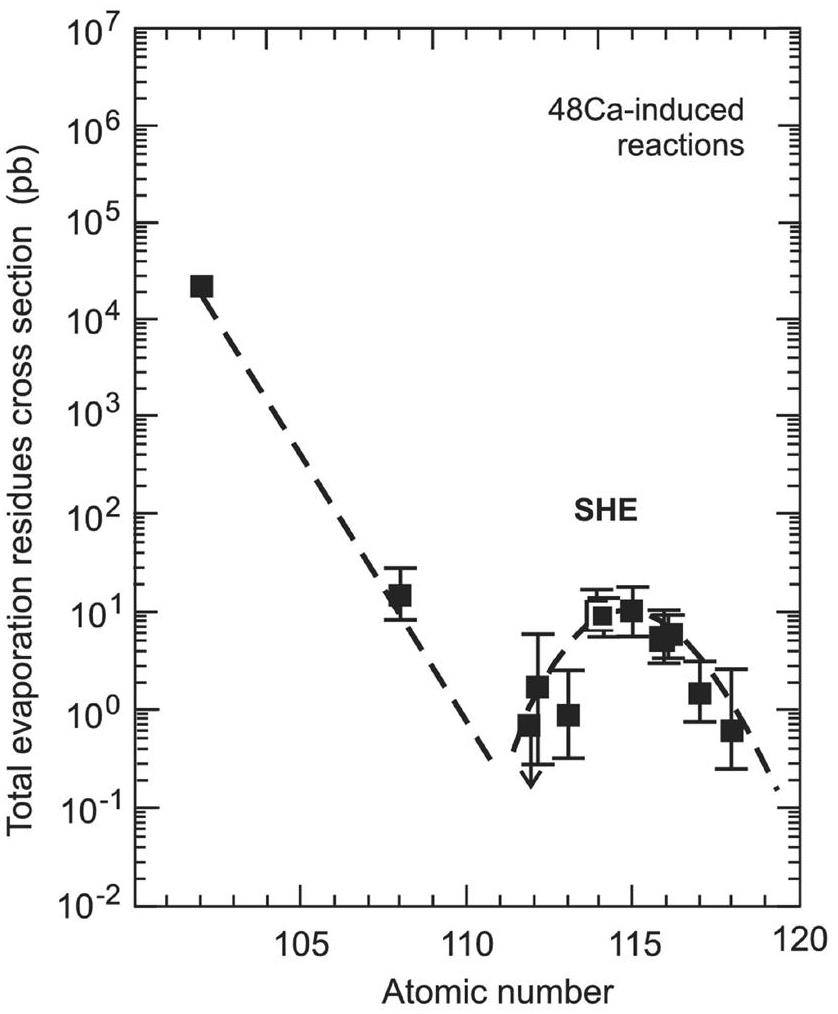

The first hot fusion reactions began with the 244Pu target, leading to the discovery of three isotopes of Flerovium, 287-289Fl [68]. Subsequently, elements with Z = 115 - 118 were synthesized using targets of 243Am, 248Cm, 249Bk, and 249Cf, thereby completing the seventh period of the periodic table [29, 31-33, 69]. The maximal ER cross sections for the hot fusion reactions are shown in Fig. 2. This reveals that the maximal ER cross sections increase as the proton number of the formed compound nucleus approaches the predicted shell closure at Z = 114, which is consistent with the increased fission barrier height predicted by macro-microscopic theory [70, 71]. Moreover, a new isotope of element 113 was discovered through the reaction 48Ca + 237Np, with an ER cross section of 0.9 pb, which is an order of magnitude higher than that for synthesizing element 113 via cold fusion reactions [72].

Figure 3 illustrates the SHNs synthesized through three types of fusion reactions, including those identified in the decay products. Compared with the other two types of fusion reactions, hot fusion reactions are particularly effective in synthesizing nuclei with higher proton numbers and greater neutron excess. Consequently, hot fusion reactions have become increasingly favored for the synthesis of new SHNs in recent years.

In 2021, GSI investigated the reaction 48Ca + 242,244Pu and discovered a new isotope, 280Ds, from decay descendants [73]. In 2022, researchers at Dubna identified 286Mc in the 5n-emission channel of the reaction 48Ca + 243Am [74]. In 2023, they explored the reaction 48Ca + 232Th and discovered a new isotope 276Ds, with 272Hs and 268Sg identified among the decay products [75]. This reaction was reattempted in 2024, leading to the discovery of 275Ds in the 5n-emission channel [40].

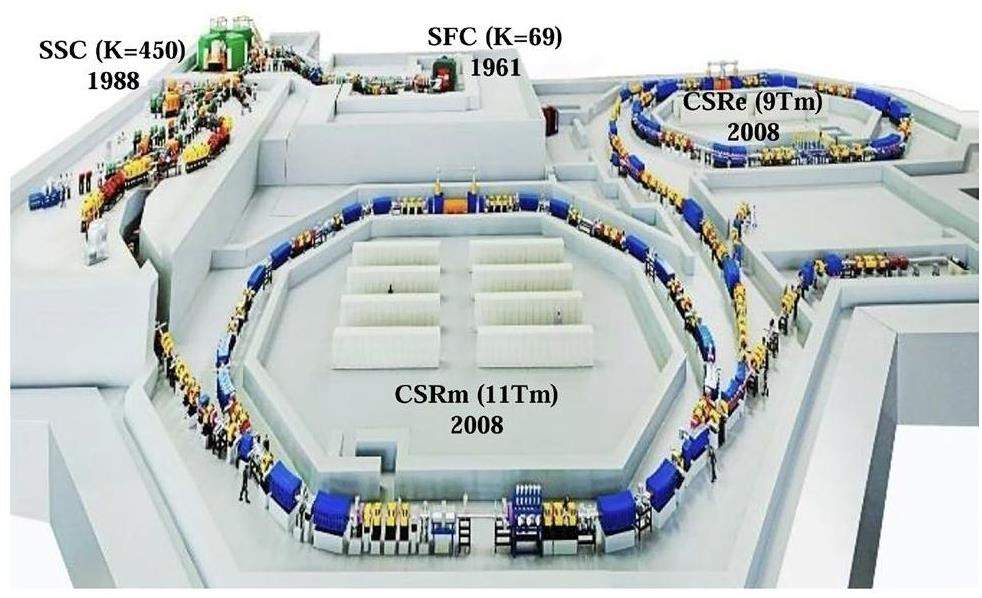

Experimental facilities

Modern heavy-ion research centers such as HIRFL in China, RIKEN in Japan, GSI in Germany, JINR in Russia, GANIL in France, LBNL, and LLNL in the USA have made significant progress in the synthesis of new isotopes with Z≤ 118 [27, 63, 67, 74, 76-80]. The largest heavy ion research facility in China is HIRFL at IMP [81, 82]. Its accelerator system consists of two cyclotrons (SFC and SSC), a synchrotron (CSRm), and a storage ring spectrometer (CSRe), as depicted in Fig. 4. Typically, the SFC is used as an injector for the SSC. Ions generated by the ion sources are first accelerated by the SFC and then injected into the SSC for further acceleration. The heavy ions provided by both cyclotrons can be accumulated, cooled, and accelerated in CSRm, then extracted to produce radioactive ion beams (RIB) or highly charged heavy ions. These secondary beams are accepted and stored in CSRe for various internal target experiments. In recent years, researchers at IMP have successfully synthesized 38 new nuclei, including 23 heavy and superheavy nuclei, based on HIRFL and other accelerators [83-95].

The UNILAC installed in 1975 at GSI is capable of accelerating all ion species from protons to uranium with energies ranging from 1.4 MeV/u to 11.4 MeV/u [96, 97]. Over the past 40 years, experiments using beams from UNILAC have successfully produced elements with Z= 107–112 and more than four hundred new isotopes [5]. Additionally, UNILAC along with the Heavy Ion Synchrotron SIS18, will serve as a high-current heavy ion injector for the new Facility for Antiproton and Ion Research (FAIR) Synchrotron SIS100 [98, 99].

The linear accelerator RILAC, constructed in 1975 at RIKEN, successfully synthesized approximately 200 new isotopes and made significant contributions to the synthesis and discovery of Nihonium [5, 101]. To facilitate the synthesis of new SHEs with Z=119, RILAC was upgraded to a superconducting linear accelerator system (SRILAC) in 2020 [102, 103]. The beam energy was increased from 5.5 MeV/u to 6.5 MeV/u, enabling SRILAC to play a major role in the synthesis of even heavier new elements.

The Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions (FLNR) in JINR has produced more than 200 new isotopes using two primary cyclotrons, DC-280 and U-400 [69, 103]. The U-400 accelerator, established in 1979 and continuously upgraded, plays a significant role in the synthesis of elements with Z= 113–118. To further explore the SHE region, DC-280 was developed in 2018, offering beam energies ranging from 4 MeV/u to 8 MeV/u and beam intensities up to 10 p, making it particularly suitable for the synthesis of new SHN [104-106].

The 88-inch Cyclotron Facility at LBNL was first commissioned in 1961 and has been in operation for over six decades. It has played a crucial role in the discovery of more than 600 isotopes [5, 100, 107]. In 2022, the construction of the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) was completed. The superconducting driver linac in the recently developed FRIB at MSU can accelerate the 238U isotope with a beam energy greater than 200 MeV/u, which provides access to the production of thousands of new nuclei [108-111].

Progressive and expansive research in nuclear physics continues to drive the upgradation and modernization of accelerators. The High-Intensity Heavy-Ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF) is a next-generation storage-ring-based heavy-ion facility developed by IMP, with expected completion by 2025 [112, 113]. HIAF integrates a linear accelerator and a synchrotron accelerator to deliver high-energy heavy-ion beams ranging from hydrogen to uranium. The principal goal of HIAF is to synthesize new superheavy nuclei and elements [114, 115]. In parallel, other advanced accelerator facilities, such as the FAIR SIS 100 at GSI, NICA-Booster in Dubna, and EURISOL in Europe, are currently under design and construction [116-118]. The comprehensive beam parameters for these facilities are detailed in Ref. [114].

For the synthesis of a new SHN, the expected ER cross sections are on the order of picobarns, with half-lives ranging from microseconds to several days [119]. The predominant decay modes for these unknown nuclei are predicted to be alpha decay and spontaneous fission. Therefore, decay products are typically separated and implanted into radiation-sensitive Si detectors. The detection of rare alpha-decay events from the synthesized SHN is then carried out against a significant background of side reaction products.

Currently, several kinematic separators have been employed in the study of heavy nuclei. Velocity filter SHIP at GSI and SHELS at JINR are notable examples [120, 121]. These facilities specialize in the separation and identification of heavy nuclei fragments using velocity filtering techniques. In addition, gas-filled magnetic separators, such as DGFRS-2 at JINR, TASCA at GSI, BGS at LBNL, GARIS-II at RIKEN, and SHANS at HIRFL, are employed to enhance the separation and detection of SHEs [122-127]. The detailed design of gas-filled recoil separators is described in Ref. [77]. These separators enable effective separation and high-sensitivity detection, which are critical for advancing the SHE research.

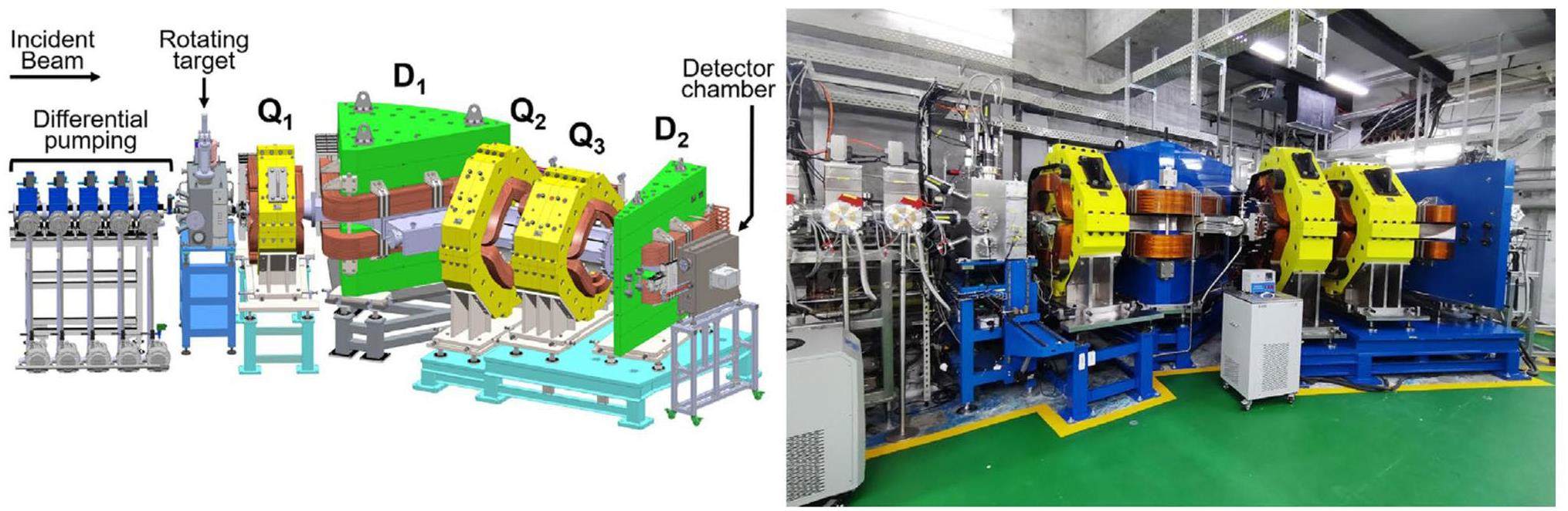

In recent years, the next generation of separators has been gradually put into operation. The GARIS-III at RIKEN was completed as part of an upgrade project in 2020. With enhanced resolution and advanced detector arrays, the aim was to investigate reactions with ER cross sections as low as 10 fb [122, 128]. In 2022, the CAFE2 Program at IMP initiated the development of a new gas-filled recoil separator, SHANS2, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Through a series of performance tests involving the reactions 40Ar + 175Lu, 40Ar + 169Tm, 40Ca + 169Tm, and 55Mn + 159Tb, SHANS2 demonstrated its effectiveness and reliability, highlighting SHANS2 as a critical tool for advancing research in the field of SHE synthesis [129, 130].

Theoretical Models

Currently, experiments aimed at investigating superheavy regions encounter several challenges. The target materials available are rare, expensive, and prone to contamination during experiments. Additionally, the limited beam intensity of accelerators requires long irradiation times, and the expected ER cross sections have already reached the detection limits. As a result, it is necessary to develop theoretical models that can provide precise predictions for optimal projectile-target combinations, incident energies, expected yields, and assess the feasibility of experimental plans.

Based on extensive experimental data, two main types of theoretical approaches have been developed to describe fusion-evaporation reactions. One type is the microscopic models, such as the quantum molecular dynamics (QMD) model [131-133] and time-dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF) theory [134-138]. The other type is the macroscopic phenomenological models, including the fusion-by-diffusion (FBD) model [134, 139, 140], dynamical cluster-decay model (DCM) [141, 142], two-step model [143-146], statistical model [147], multidimensional Langevin-type dynamical equations [148-151], and dinuclear system (DNS) model [9, 152-161].

Microscopic models

Microscopic models start with basic nucleon-nucleon interactions, often described by effective potentials such as Skyrme potentials. These models require self-consistent field calculations, in which each nucleon moves within the mean field generated by all other nucleons. Microscopic models offer a deep understanding of nucleon behavior and can explain and predict a wide range of nuclear phenomena. However, they often require significant computational resources and are limited by the accuracy of the interaction models.

TDHF theory can be derived from the time-dependent variational principle [162]. In the TDHF, the many-body wave function is approximated as a Slater determinant, automatically ensuring the Pauli exclusion principle. The TDHF method is a fully microscopic, parameter-free theory that unifies the nuclear structure and reactions within a single framework. Dynamic and quantum effects are automatically incorporated into this approach [163].

By constraining the density distribution obtained from the dynamical evolution in the TDHF method, the density-constrained time-dependent Hartree-Fock (DC-TDHF) model can be derived, allowing for the extraction of nucleus-nucleus potentials in heavy-ion reactions. Using this method, Ref. [164] investigated the feasibility of forming a compound nucleus with Z=119 via the 50Ti+249Bk reaction.

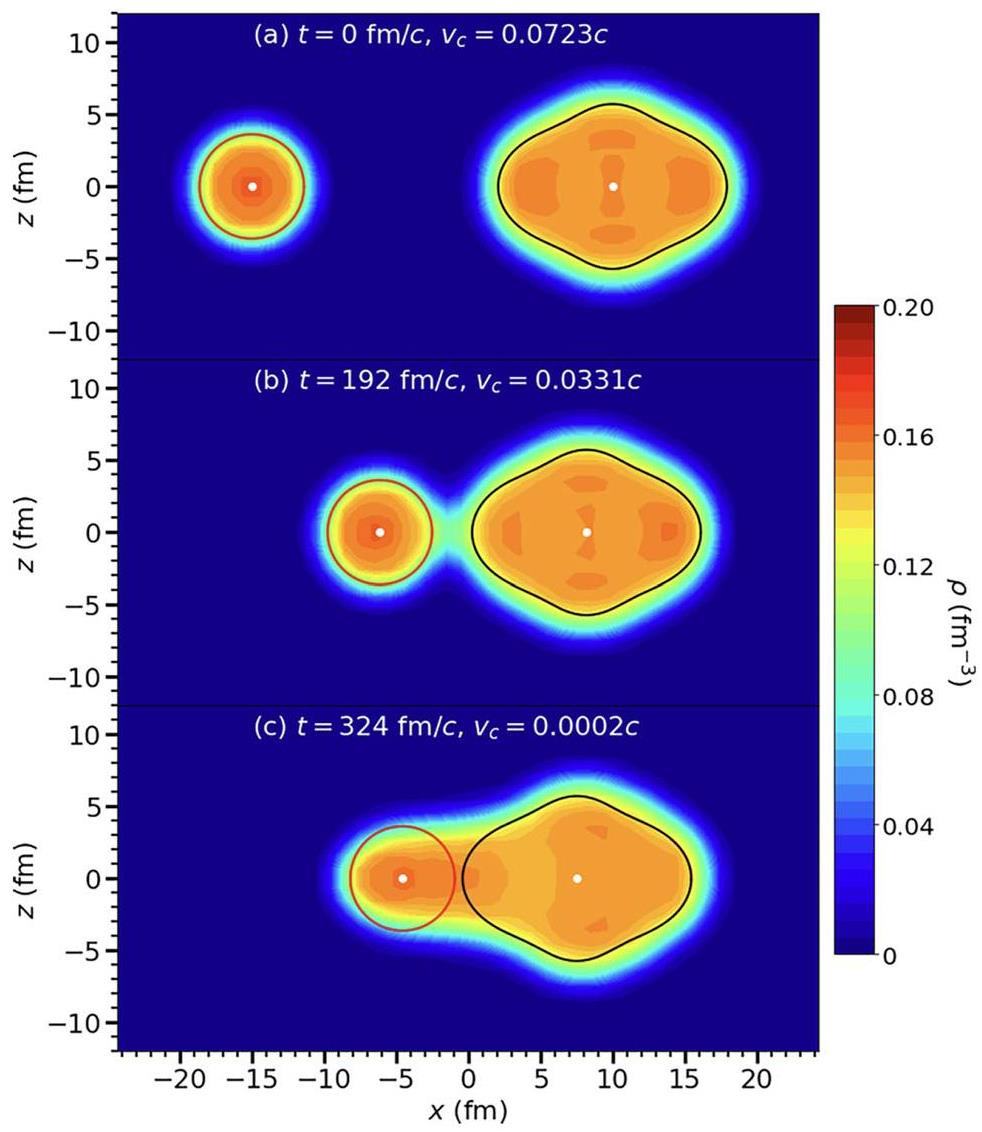

The TDHF model can also be combined with phenomenological models to obtain more accurate predictions. In Ref. [165], the isotopic dependence of quasi-fission and fusion-fission in the production of flerovium isotopes was investigated. The TDHF method was applied for fusion and quasifission dynamics, while the statistical evaporation model HIVAP was used for fusion-fission dynamics. Reference [134] examined the orientation effects of the 48Ca+238U reaction with the reaction dynamics described by TDHF theory, as illustrated in Fig. 6. This study combines the TDHF model with coupled-channel and FBD models, and predicts that the tip orientation is more favorable for both the capture process and formation of the compound nucleus in this reaction. Additionally, Ref. [137] combined the TDHF method with the Langevin equation, suggesting that differences in the probabilities of evaporation residue formation among reaction systems primarily originate from the evaporation process, which is sensitive to the fission barrier height and excitation energy of the compound nucleus.

The QMD model is a microscopic model derived from the classical molecular dynamics (CMD) model and the many-body Schrödinger equation [166]. In the QMD model, each nucleon is represented by a Gaussian wave packet, incorporating both mean-field effects and two-body collisions [167]. Advanced variations of the QMD model, such as the isospin-dependent quantum molecular dynamics (IQMD) model and the improved quantum molecular dynamics (ImQMD) model, are particularly effective in describing the processes of low-energy heavy-ion collisions.

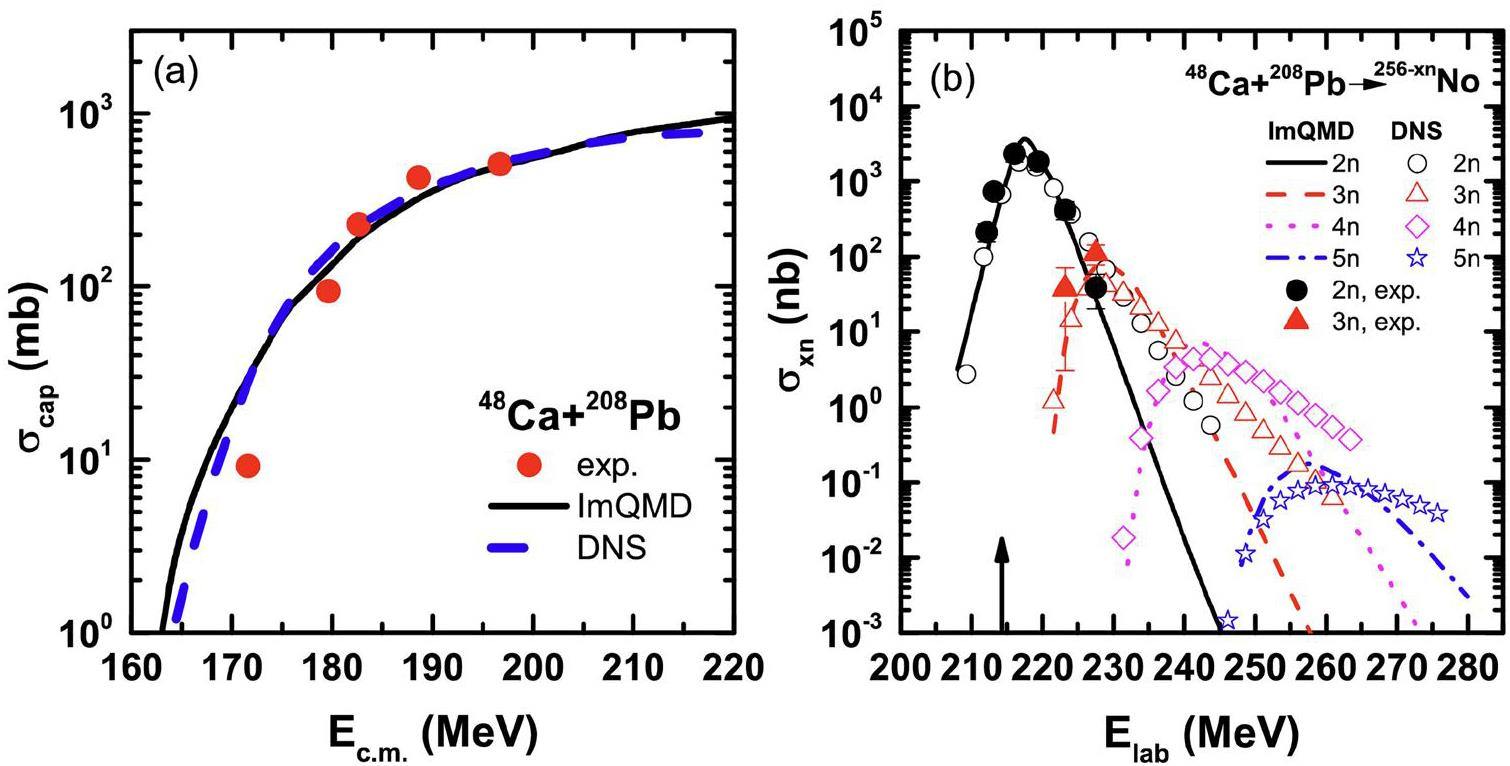

Within the QMD model framework, the fusion process is considered to occur when two independent nuclei successfully overcome the Coulomb barrier and maintain a stable monomer density during rotation or oscillation of the compound nucleus. By simulating a large number of events, the fusion cross section at a specific incident energy can be statistically determined. In Ref. [131], the excitation functions predicted by the ImQMD model for the reaction 48Ca+208Pu were compared with the results obtained from the DNS model and experimental data, as depicted in Fig. 7. This work confirmed the reliability of the ImQMD model and predicted the optimal projectile-target combinations for synthesizing 243-248No isotopes. Additionally, Ref. [133] applied the IQMD model to investigate the enhanced fusion probabilities in reactions with 44Ca beams, attributing the enhancement to the rapid development of the neck region and the higher neutron-to-proton ratio. The study also predicted the optimal projectile-target combinations for producing new 245-250Lr isotopes, along with the corresponding incident energies.

Phenomenological models

In phenomenological models, dynamical evolution equations are established by incorporating certain collective degrees of freedom to describe the dynamics of nuclear reactions. These approaches simplify the computational process by neglecting the intricate interactions among the nucleons. With the de-excitation process treated using statistical models, the HIVAP code, the KEWPIE code or the GEMINI++ model [143, 168-171], phenomenological models can be effectively applied to heavy-ion collision reactions near the Coulomb barrier.

One approach for describing the fusion process considers the dynamic evolution of the formed mononucleus, proposing that once the projectile and target nuclei come into contact, they rapidly lose their individuality and form a highly deformed nucleus. Fusion is considered to occur when the deformed nucleus gradually evolves into a spherical compound nucleus; otherwise, quasi-fission occurs. The macroscopic dynamical model was the first to describe the fusion mechanism based on this concept [172-175]. In this model, the nucleus is treated as a viscous liquid drop, and the fusion process is regarded as a purely dynamic phenomenon that can be described using classical equations of motion. However, this model faced challenges in reproducing the ER cross sections for fusion reactions, as it did not account for the competition between fusion and quasi-fission, nor did it incorporate the shell effect [176]. To address these limitations, the two-step model [143-145, 177] and fusion-by-diffusion model [139, 140] introduced shell effects in the calculation of the potential energy surface, along with statistical fluctuations in the interaction of colliding nuclei [178]. These enhancements have allowed for more accurate reproduction and prediction of ER cross sections in fusion reactions.

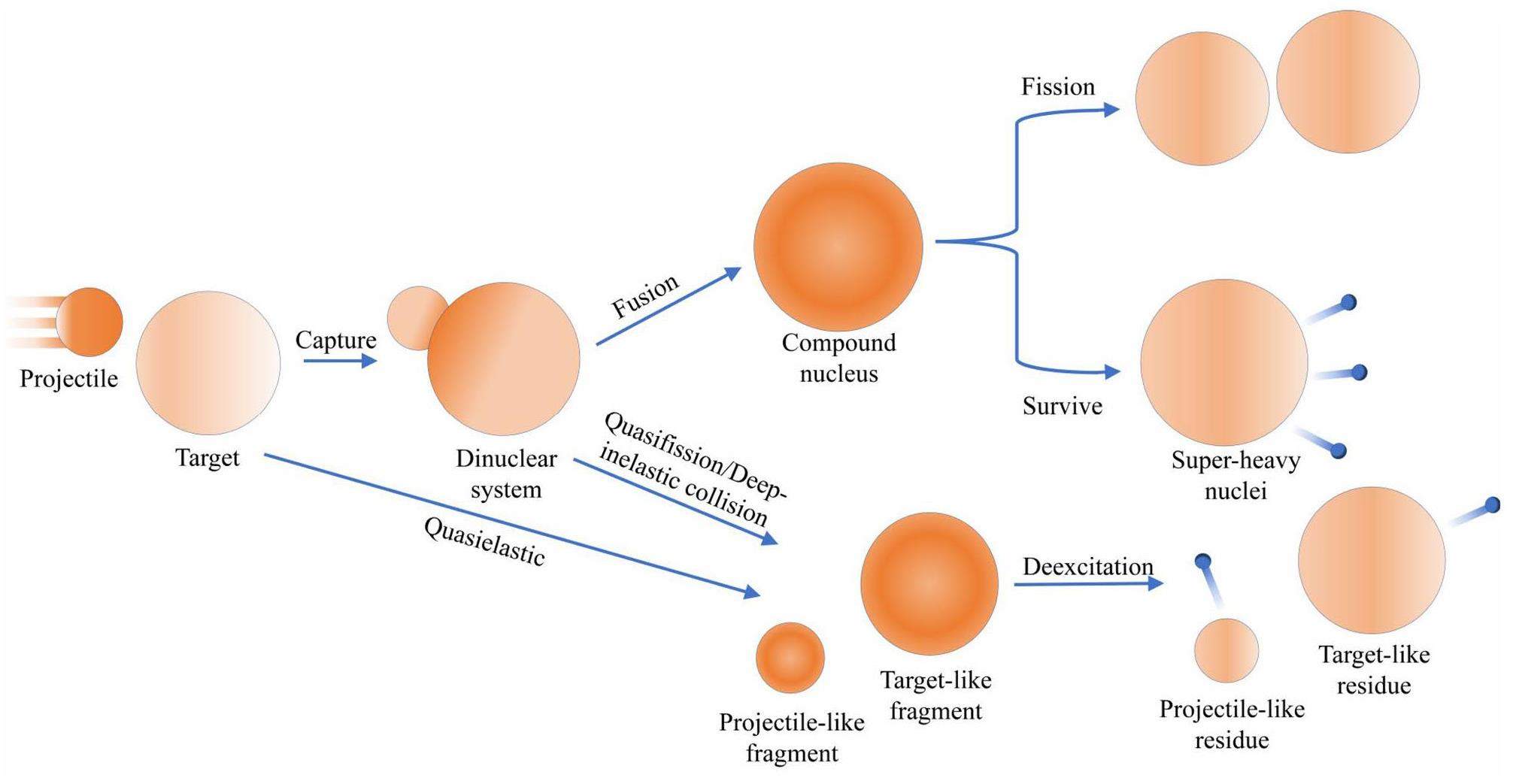

Another description of the fusion process focuses on the degree of freedom of the mass asymmetry. In these models, the two nuclei retain their individuality and nucleon transfer occurs within the formed dinuclear system, as depicted in Fig. 8. Fusion is considered to occur when all the nucleons from the projectile are successfully transferred to the target nucleus. Conversely, quasi-fission process takes place when nucleons are transferred from the target nucleus to the projectile [179].

Based on this assumption, the DNS model was developed. The nucleon transfer process within the DNS model is treated by solving a set of master equations, which are governed by the potential energy surface considering nuclear structure effects [154]. The calculated results for cold and hot fusion reactions using the dinuclear system model match well with available experimental data [157, 180]. However, this approach initially did not consider the dynamic factors influencing the fusion stage. To address this, Ref. [153] coupled the dynamic deformation of the nucleus with nucleon transfer within the DNS model, and predicted the ER cross sections for the synthesis of a new SHE. In recent years, neural networks and machine learning methods have been introduced to optimize nuclear data and refine the parameters of the theoretical model [181-184].

The nucleon collectivization model offers an intermediate approach for describing the fusion process compared with the previously mentioned methods [185]. In this model, within the formed dinuclear system, a portion of nucleons is considered to become “common” nucleon, shared by both nuclei. Fusion is thought to occur when all nucleons are transformed into common nucleons; otherwise, quasi-fission occurs. Although this model successfully describes the excitation function of hot fusion reactions, the physical concept of the introduced common nucleons remains highly controversial.

Given the significant difference in the descriptions of the fusion process across various models, some researchers have attempted to combine fusion mechanisms from different theoretical models and experimental observations to develop relatively simple empirical formulas for calculating fusion probability [186-191]. These formulas, informed by experimental phenomena and theoretical approaches, identify several influential factors in the fusion process, including the excitation energy, quasi-fission barrier, compound nucleus mass or charge number, and mass asymmetry [186, 188, 189]. These empirical formulas effectively reproduce the experimental results of the known fusion reactions. Recently, a model-independent method, based on the Coulomb barrier height of side-side collisions and Q value, was established to predict the optimal incident energies for unknown reaction systems [192]. This approach allows the estimation of optimal incident energies with minimal uncertainty.

Efforts in the Synthesis of New Superheavy Elements with Z = 119, 120

Since the synthesis of Oganesson through the reaction 48Ca+249Cf→294Og+3n, the seventh period of the periodic table was completed. However, for the synthesis of SHE with atomic numbers Z > 118, the 48Ca-induced fusion reactions are restricted by the limited availability of Einsteinium and Fermium targets. Consequently, heavier beams, such as 50Ti, 51V, and 54Cr, must be applied.

The experimental attempts to synthesize a new SHE are summarized in Table 2. Initially, GSI attempted to synthesize the SHE with Z=120 using the reaction 64Ni + 238U in 2008 [193], and JINR attempted the reaction 58Fe + 244Pu in 2009 [194]. However, no corresponding α decay chains were observed in these experiments. In 2016, GSI attempted to synthesize element with Z=120 via the reaction 54Cr + 248Cm [195, 196], observing three α decay chains attributed to 299120. Unfortunately, these were later identified as random events [197]. Additionally, in 2020, GSI conducted experiments to search for the new elements with Z = 119 and Z = 120 using the reactions 50Ti + 249Bk and 50Ti + 249Cf, respectively, but no evidence of a new SHE was found [198]. In 2022, RIKEN investigated the quasielastic barrier distribution for the reaction 51V+248Cm and deduced the optimal reaction energy for synthesizing element with Z = 119 through this reaction [199].

| Element | Year | Laboratory | Reaction | Results | Detection limit | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z = 120 | 2008 | GSI | 64Ni + 238U | No α decay chain | 0.09 pb | [193] |

| Z = 120 | 2009 | JINR | 58Fe + 244Pu | No α decay chain | 0.4 pb | [194] |

| Z = 120 | 2016 | GSI | 54Cr + 248Cm | Three random α decay chains | 0.58 pb | [195] |

| Z = 119 | 2020 | GSI | 50Ti + 249Bk | No α decay chain | 0.065 pb | [198] |

| Z = 120 | 2020 | GSI | 50Ti + 249Cf | No α decay chain | 0.2 pb | [198] |

| Z = 119 | 2022 | RIKEN | 51V + 248Cm | Optimal reaction energy was estimated | [199] |

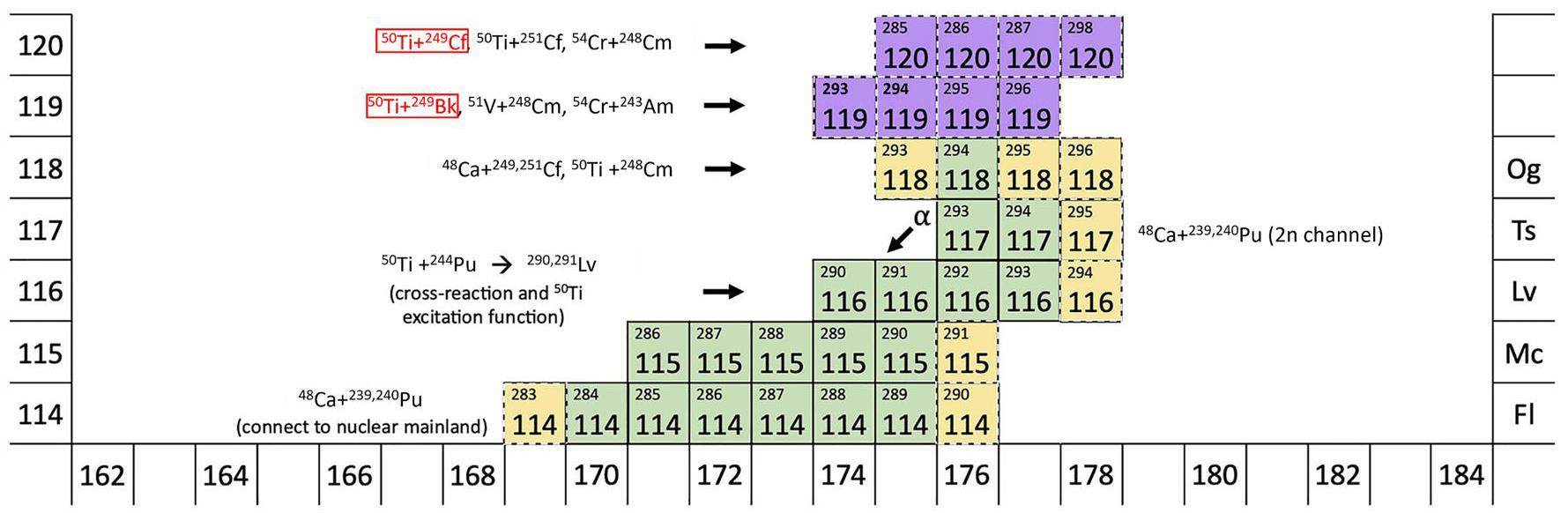

In 2024, the reaction 50Ti+244Pu was investigated at the LBNL 88-Inch Cyclotron Facility, producing an isotope 290Lv with an ER cross section of 0.44 pb [200]. Although the ER cross section is lower than that of the 48Ca-induced reactions, this experiment proves the feasibility of using a 50Ti beam for the production of a new SHE [201]. Recently, the upgraded experimental facility HIFRL-CAFE2 was tested using the reaction 48Ca + 243Am. The synthesis of the element with Z = 119 via the reaction 54Cr + 243Am is currently underway. JINR has also planned to explore the reactions 50Ti + 249Bk and 54Cr + 243Am for synthesizing the 119th element, as well as the reactions 50Ti + 249Cf and 54Cr + 248Cm for the 120th element [202]. The nuclei to be searched are summarized in Fig.9.

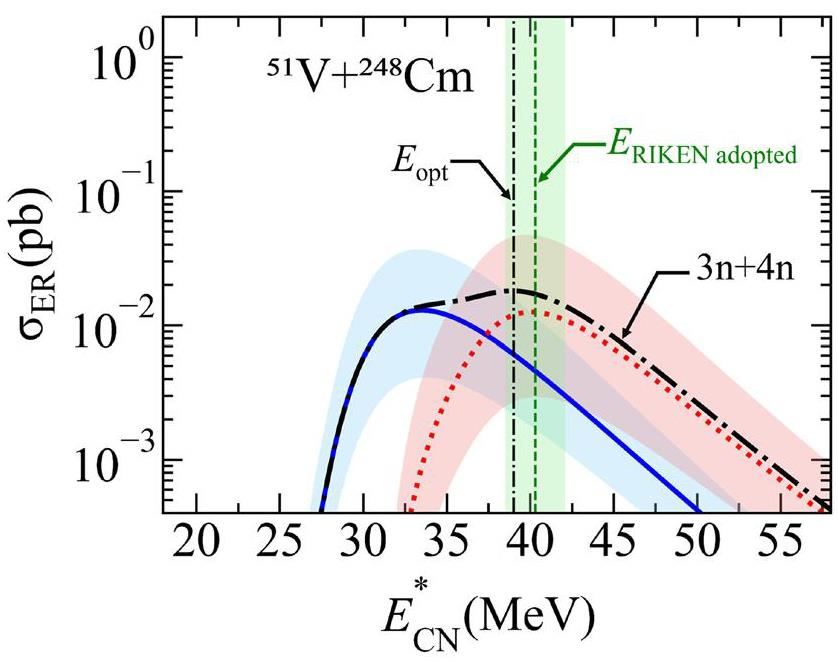

Various theoretical models have predicted the optimal projectile-target combinations and corresponding incident energies for new elements beyond Oganesson via fusion reactions [140, 142, 143, 153, 157, 188, 189, 203-210]. Figure 10 shows the optimal reaction energies predicted in Ref. [157] and estimated by RIKEN for the reaction 51V + 248Cm, with a strong agreement between the predicted and estimated energies. As summarized in Ref. [157] and Ref. [200], most models identify the reactions 50Ti + 249Bk and 50Ti + 249Cf as advantageous for producing SHE with Z = 119 and Z = 120. The predicted maximal ER cross sections from different models generally fall within the fetobarn range, although the optimal incident energies can differ by several MeV for certain reactions. Additionally, based on measurements of the mass and angular distributions of fission fragments, Ref. [211] also predicted that the reaction 50Ti + 249Cf shows promise for synthesizing SHE with Z = 120. For the synthesis of SHE with Z = 121, Ref. [156] suggested that the reactions 46Ti + 252Es and 46Ti + 254Es could be feasible in future experiments, with maximal ER cross sections expected to reach several fetobarns.

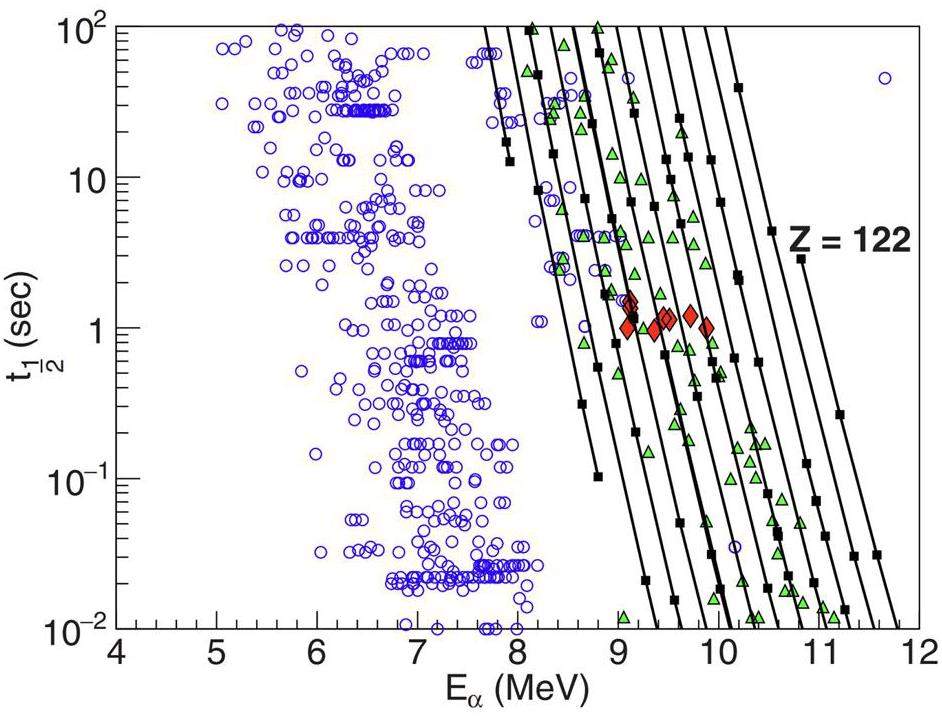

Recently, researchers proposed high-energy alpha particle emission as a novel mechanism for synthesizing new elements [212]. In the experiments conducted at JINR, the energy spectra of α particles emitted from the reactions 40Ar + 232Th and 48Ca + 238U at near-barrier energies were measured. The results indicated that at the kinematic limit, the observed cross sections were in the picobarn range. These experiments revealed that two-body reactions facilitate the production of heavy residue nuclei with minimal excitation energy, thereby enhancing their survival probability. Consequently, this reaction mechanism can potentially produce SHN with ER cross sections that are several orders of magnitude greater than those achieved through traditional fusion-evaporation reactions.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

The synthesis of new SHNs faces several challenges, including short half-lives and high instability of both the target materials and the produced nuclei [213, 214]. The maximal ER cross sections in the hot fusion reactions also approached the detection limit. Moreover, the limited availability of actinide targets requires the use of heavier projectiles in future experiments [200], which is expected to further suppress ER cross sections compared to those induced by 48Ca. To address these challenges, nuclear physics laboratories worldwide are upgrading their equipment, as discussed in Sect. 3, to achieve higher beam intensities and enhanced detection precision.

In various theoretical models, many assumptions and approximations have been adopted, such as employing the double-folding potential with a sudden approximation to calculate the nuclear potential, assuming quadrupole or hexadecapole deformations of the nucleus, and using empirical surface diffusion coefficients. The fission barrier in the de-excitation process is typically described in one-dimensional parameterized form. Precise nuclear masses of superheavy nuclei are also crucial [215-217]. As demonstrated in Refs. [218, 219], even predictions made using the same model can vary significantly when based on different mass tables.

Although these assumptions and approximations are necessary because of the current limitations in computational resources and theoretical development, the uncertainties introduced by empirical parameters and approximations constrain the extrapolative capability of the models and cannot be ignored. Some studies have attempted to estimate the uncertainties originating from these empirical parameters or to constrain them using microscopic approaches [146, 157, 158, 220]. However, a comprehensive evaluation of the uncertainties introduced by these empirical methods is required.

Calculations in the SHN region using microscopic models involve handling the interactions among a large number of nucleons, often resulting in computation times ranging from several months to years. This limitation significantly restricts the application of microscopic models in SHE research. While advancements in computational power, as predicted by Moore’s law, may alleviate this issue, the introduction of new parallel computing methods presents a more immediate solution. Researchers are exploring ways to identify the key physical degrees of freedom in nuclear reactions to develop new phenomenological models. Additionally, the limited amount of experimental data from 48Ca-induced reactions hinders the verification of theoretical models, raising concerns regarding their reliability when extrapolating to reactions involving heavier projectiles. More experimental data from a variety of projectile-target combinations are also needed to develop more robust theoretical models.

Currently, α decay tagging is the primary technique for identifying reaction products, but it is limited by the requirement that synthesized nuclei have suitable half-lives and unambiguous decay chains. As a result, many SHNs in the neutron-rich region cannot be identified using this method. Therefore, new identification techniques, such as high-precision mass measurements, laser resonance ionization, and a combination of mass separation with decay tagging, should be considered [221-223].

The relatively low neutron-to-proton ratio in both the projectile and target nuclei during the fusion reactions leads to the formation of a compound nucleus with a reduced neutron number. Additionally, the compound nucleus must undergo neutron evaporation to reach its ground state, resulting in the production of nuclei that are typically neutron-deficient. Such conditions present a significant challenge for the production of neutron-rich superheavy nuclei, as the heaviest available targets are currently 249Cf and 249Bk.

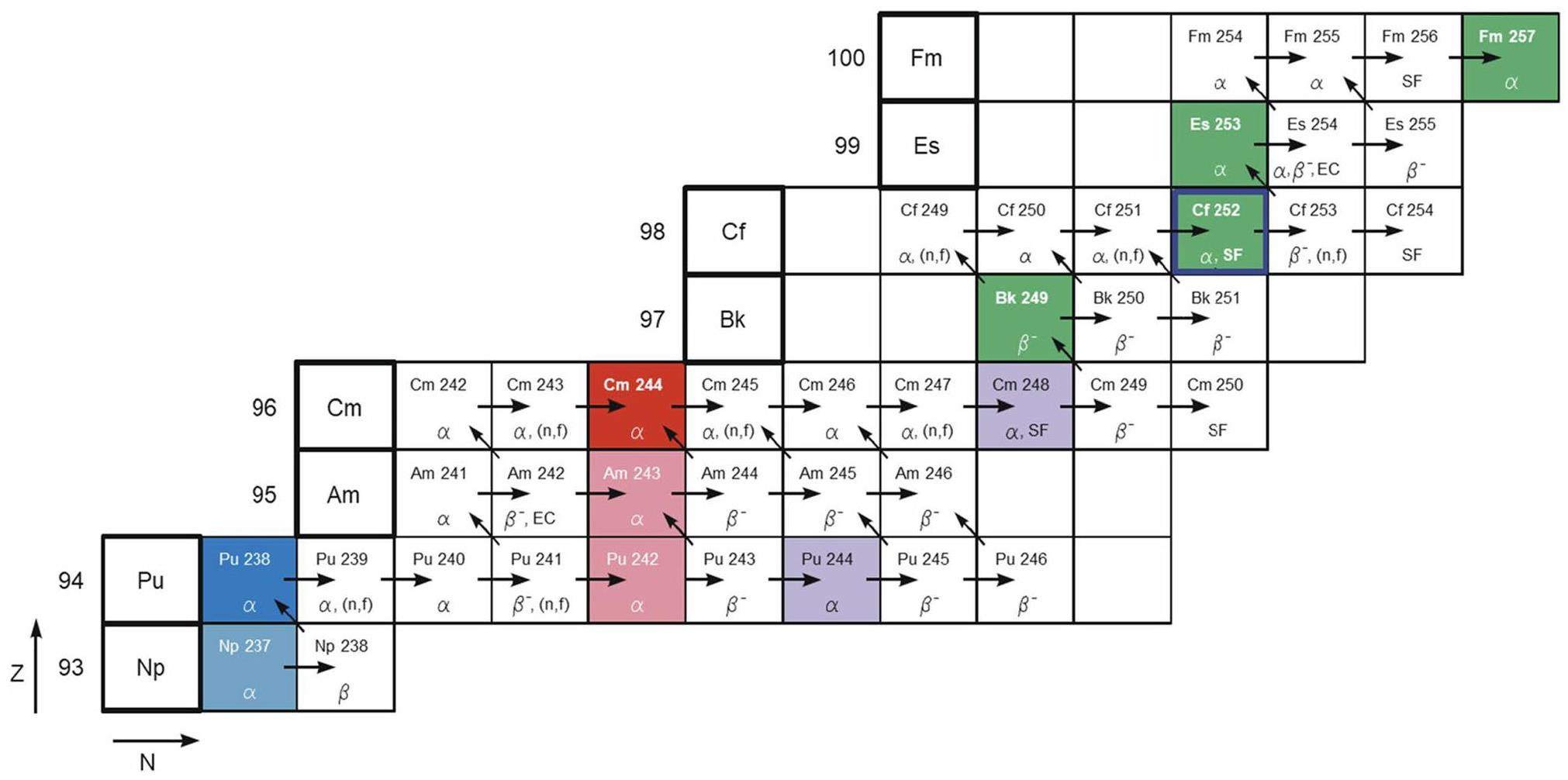

The actinide target nuclei used in fusion reactions are produced through the intense neutron irradiation of targets composed of mixed Pu, Am, and Cm in high-flux reactors, as illustrated in Fig. 11. Currently, reactors capable of providing these actinide materials include the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory [224], the Advanced Test Reactor (ATR) at Idaho National Laboratory [225], and the SM-3 Reactor at the Research Institute of Advanced Reactors (RIAR) in Dimitrovgrad [226]. Additionally, the Jules Horowitz Reactor (JHR) [227] and the Tsinghua High Flux Reactor (THFR) [228], which are currently under construction, will also provide heavy actinide targets. In future experiments, new actinide target materials, particularly neutron-rich targets, such as 251Cf and 254Es, could be produced and applied in fusion reactions [202].

Theoretical studies suggest an “island of stability” where enhanced shell effects lead to long-lived nuclei. However, the precise location of this area remains uncertain because of the varying predictions from different nuclear models. Macroscopic-microscopic models employing different potentials, such as Nilsson, Woods-Saxon, and folded Yukawa, typically locate the center at Z = 114, N = 184 [11, 12, 229, 230]. Depending on the selected parameters, self-consistent models using Skyrme-Hartree-Fock or relativistic mean field interactions predict various combinations of Z = 114, 120, 124, or 126, and N = 172 or 184 [14, 15, 15-20]. In recent years, researchers have been investigating novel reaction mechanisms to explore the neutron-rich superheavy region and reach the center of the “island of stability”. Radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions have been proposed as methods for synthesizing neutron-rich SHN [159, 190, 222, 231, 232]. Additionally, multi-nucleon transfer (MNT) reactions have been suggested as promising approaches for producing neutron-rich isotopes [1-3, 222, 232-238].

Radioactive beams

Compared to stable beams, neutron-rich radioactive projectiles have higher neutron-to-proton ratios, enabling exploration of the neutron-rich SHN region. Figure 12 summarizes the possible radioactive beams that can be generated at the Argonne Tandem Linac Accelerator System (ATLAS). However, a significant challenge for radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions is low beam intensity. Although stable beam intensities can reach the order of 1012 p/s, the intensities of radioactive beams are currently much weaker. To address this limitation, modern radioactive beam accelerator facilities, such as the Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory (RIBF) and the Second-generation System On-Line Production of Radioactive Ions (SPIRAL2) [239, 240], are working on upgrading their capabilities to achieve high-intensity exotic ion beams [222, 241].

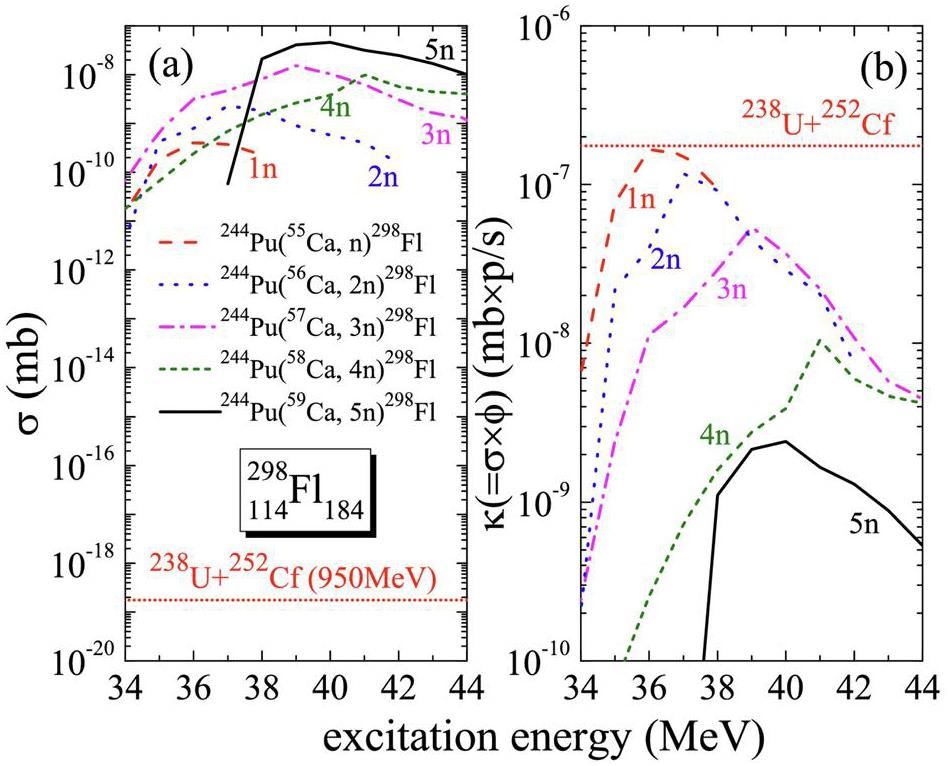

Many theoretical studies have investigated the mechanisms of radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions. Reference [242] predicted that the reaction induced by the neutron-rich radioactive beam 46Ar could produce new neutron-rich nuclei 290-292Fl, provided that the beam intensity was sufficient. Reference [159] explored the production of neutron-rich SHN with Z = 105–118 through radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions. Additionally, Ref. [243] examined the possibility of reaching the “island of stability” via radioactive beams and 244Pu, 248Cm, 249Cf targets.

Multi-nucleon transfer reactions

Several MNT reaction experiments have been conducted in recent years. In 2018, significant α particle emission was observed in the reaction 238U + 232Th [244]. A comparison between the experimental results and theoretical calculations suggested the possible formation of unknown neutron-rich nuclei with atomic numbers of up to 116, as depicted in Fig. 13. However, owing to limitations in the detection methods, the cross section information for these formed nuclei was not measured. Significant advancement in the production of new nuclei via MNT reactions was achieved in 2015 at the UNILAC accelerator at GSI, where the reaction 48Ca+248Cm was studied. This experiment resulted in the identification of five new neutron-deficient isotopes: 216U, 219Np, 223Am, 229Am and 233Bk [245]. These findings demonstrate that the MNT reactions can be effectively utilized to synthesize neutron-deficient transuranium nuclei. In 2023, RIKEN discovered a new neutron-rich nucleus, 241U, through the MNT reaction 238U + 198Pt, demonstrating the feasibility of MNT reactions for producing neutron-rich nuclei near the N = 152 subshell [246].

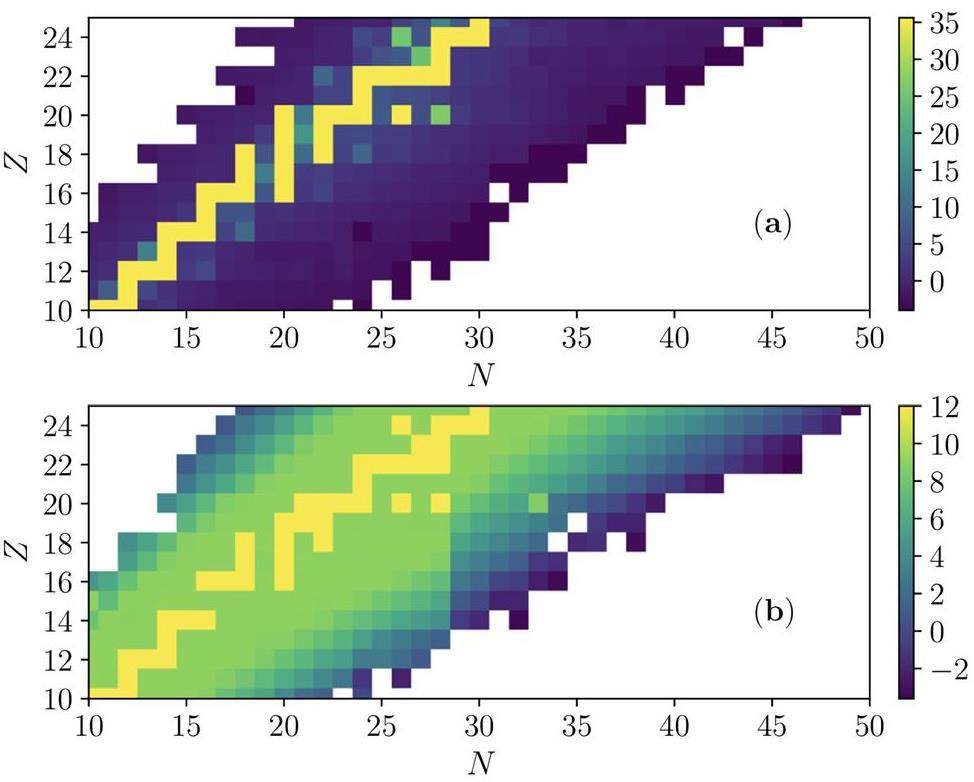

Several theoretical models, such as the DNS model [6, 247-251], GRAZING model [252-254], QMD model [252, 255, 256], Langevin equations [257, 258], time-dependent covariant density functional theory [259], and TDHF model [256, 260-264] have also been applied to investigate MNT reactions. In Ref. [265], the reliability of DNS model in MNT reactions was validated, predicting the production cross sections of four new Rf isotopes through the 238U + 252Cf reaction. Reference [266] combined the GRAZING model framework with the DNS model, significantly enhancing the theoretical descriptions of experimental results for MNT reactions. Reference [267] introduced the deformation degree of freedom and Monte Carlo de-excitation methods, leading to the development of an improved DNS-sysu model, and explored the feasibility of reaching the “island of stability” through radioactive-beam induced fusion reactions and MNT reactions, as shown in Fig. 14.

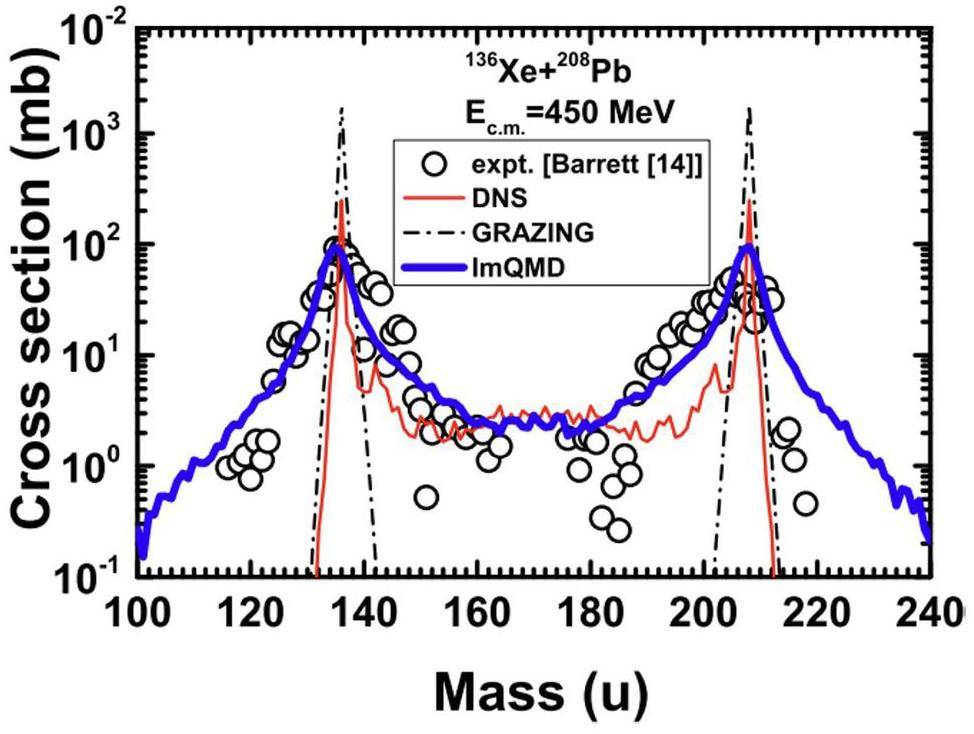

Based on the ImQMD model, Ref. [268] studied the production cross sections of superheavy isotopes formed in the 238U + 238U reaction, finding that the isospin dependence of the fission barrier results in production cross sections for neutron-rich isotopes 254-256Cf being nearly three orders of magnitude lower than those of 249Cf. Ref. [252] presents a comparison of the mass distributions of primary binary fragments predicted by the ImQMD, DNS, and GRAZING models with experimental data, as shown in Fig. 15. The study reveals that the DNS and GRAZING models are primarily suitable for describing transfer processes involving only a few nucleons between the projectile and target. In contrast, the ImQMD model shows a high level of agreement with experimental results across most mass regions.

For the TDHF model, Ref. [262] observed that in the 238U + 124Sn reaction, owing to the inverse quasifission process, 124Sn can transfer a large number of nucleons to 238U, leading to the formation of new isotopes. By employing a multidimensional dynamical model based on Langevin equations, Ref. [269] explored the production of heavy transuranium nuclei during collisions with actinide nuclei. The results suggest the feasibility of synthesizing several neutron-rich heavy actinide isotopes, with production cross sections surpassing 1 μb. Additionally, new methods based on the master and Langevin equations have been applied to MNT reactions [270, 271]. The feasibility of MNT reactions with radioactive beams has been investigated in several studies [272-275].

Summary

The search for new superheavy nuclei achieved significant success, particularly with the completion of the seventh period of the periodic table. Despite these accomplishments, the synthesis of elements beyond Z = 118 remains a substantial challenge, largely because of the limited availability of actinide targets and rapidly decreasing ER cross sections. Employing heavier projectiles is a promising approach for the synthesis of new superheavy elements. The feasibility of the 50Ti projectile is experimentally validated. The investigation of new reaction mechanisms, including radioactive beam-induced fusion and multi-nucleon transfer reactions, presents promising pathways for producing neutron-rich superheavy nuclei and for approaching the next shell closure. Recent developments in theoretical models have provided valuable predictions for optimizing experimental conditions. However, the reliability of these models requires further validation. Continued upgrades to accelerator beam intensities and detector efficiencies, coupled with the development of more precise theoretical models, will be crucial for overcoming the challenges associated with the synthesis of new superheavy elements.

Radioactive Element 93

. Phys. Rev. 57, 1185-1186 (1940). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.57.1185.2Production cross sections for exotic nuclei with multinucleon transfer reactions

. Front. Phys. 13(6),Progress of synthesis of superheavy nuclei

, Prog. Phys. 21(1), 29-44 (2001).Superheavy nuclei and superheavy elements

. Phys 43(12), 817-825 (2014). https://doi.org/10.7693/wl20141206Theoretical study of structure and synthesis mechanism of superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 31(3), 253-272 (2014). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.31.03.253Study on superheavy nuclei and superheavy elements

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 34(3), 318-331 (2017). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.34.03.318Closed shells for Z> 82 and N> 126 in a diffuse potential well

. Phys. Lett. 22(4), 500-502 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9163(66)91243-1Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations: FRDM(2012)

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 109-110, 1-204 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.10.002Shell structure of the superheavy elements

. Nucl. Phys. A 611(2), 211-246 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(96)00337-5Shape coexistence and triaxiality in the superheavy nuclei

. Nature 433, 705-709 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03336Nuclear structure features of very heavy and superheavy nuclei-tracing quantum mechanics towards the ’island of stability’

. Phys. Scr. 92(8),Superheavy nuclei in self-consistent nuclear calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 56, 238-243 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.56.238Shell corrections of superheavy nuclei in self-consistent calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Description of structure and properties of superheavy nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 58(1), 292-349 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2006.05.001On magic numbers for super- and ultraheavy systems and hypothetical spherical double-magic nuclei

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys 43(1),The quest for superheavy elements and the limit of the periodic table

. Nat Rev Phys 6, 86-98 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-023-00668-yPositive Identification of Two Alpha-Particle-Emitting Isotopes of Element 104

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 22, 1317-1320 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.22.1317261Rf; new isotope of element 104

. Phys. Lett. B 32 (2), 95-98 (1970). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(70)90595-2Studies of lawrencium isotopes with mass numbers 255 through 260

. Phys. Rev. C 4, 632-642 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.4.632Discovery of the transfermium elements. part ii: Introduction to discovery profiles. part iii: Discovery profiles of the transfermium elements (note: For part i see pure appl. chem., vol. 63, no. 6, pp. 879-886, 1991)

. Pure and Appl. Chem. 65 (8), 1757-1814 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199365081757The synthesis of element 105

. Sov. At. Energy 29, 967-975 (1970).Experiment on the synthesis of element 113 in the reaction 209Bi(70Zn,n)278113

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 73, 2593 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1143/jpsj.73.2593The discovery of the heaviest elements

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 72, 733 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.72.733Synthesis of the isotopes of elements 118 and 116 in the 249Cf and 245Cm+48Ca fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Synthesis of nuclei of the superheavy element 114 in reactions induced by 48Ca

. Nature 400, 242 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/22281Investigation of the 243Am+48Ca reaction products previously observed in the experiments on elements 113, 115, and 117

. Phy. Rev. C 87,Observation of the decay of 292116

. Phy. Rev. C 63,Synthesis of a new element with atomic number Z=117

. Phy. Rev. Lett. 104,Spontaneous fission of rutherfordium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 31, 1801-1815 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.31.1801Two new alpha-particle emitting isotopes of element 105, 261Ha and 262Ha

. Phys. Rev. C 4, 1850-1855 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.4.1850A new alpha-particle-emitting isotope 259 Db

. Eur. Phys. J. A 10, 21-25 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100500170140Doubly magic nucleus 108270Hs162

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97,Observation of the 3n evaporation channel in the complete Hot-Fusion reaction 26Mg+248Cm leading to the new superheavy nuclide 271Hs

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100,Synthesis and decay properties of isotopes of element 110: 273Ds and 275Ds

. Phys. Rev. C 109,α decay of 273110: Shell closure at N=162

. Phys. Rev. C 54, 620-625 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.54.620Further experimental study of fast fission with the Cl + Au system

. Nucl. Phys. A 385(2), 319-330 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90175-0Fusion barrier distributions for heavy ion systems involving prolate and oblate target nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 54, 3068-3075 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.54.3068Experimental fusion barrier distributions reflecting projectile octupole state coupling to prolate and oblate target nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1587-1590 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.1587Effects of shape and transfer degrees of freedom on sub-barrier fusion

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 23 (10), 1303 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/23/10/019Fusion-fission and quasifission of superheavy systems in heavy-ion induced reactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 834 (1), 374c-377c (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.01.043Synthesis of neutron-deficient isotopes of fermium, kurchatovium and element with atomic number 106

. JETP Lett. 20 (8), 20 (1974).Experiments on the synthesis of neutron-deficient isotopes of kurchatovium in reactions with accelerated 50Ti ions

. Sov. At. Energy 38 (6), 492-501 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01127435On the properties of the element 106 isotopes produced in the reactions Pb+ 54Cr

. Zeitschrift für Physik A Atoms and Nucl. 315, 197-200 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01419379Identification of element 107 by α correlation chains

. Z. Phys. A 300 (1), 107-108 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01412623The identification of element 108

. Z. Phys. A 317 (2), 235-236 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01421260Observation of one correlatedα-decay in the reaction 58Fe on 209Bi→ 267109

. Z. Phys. A: Hadrons Nucl. 309 (1), 89-90 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01420157Production and decay of 269110

. Z. Phys. A: Hadrons Nucl. 350 (4), 277-280 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01291181The new element 111

. Z. Phys. A: Hadrons Nucl. 350 (4), 281-282 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01291182The new element 112

. Z. Phys. A: Hadrons Nucl. 354 (3), 229-230 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02769517Spontaneous fission and alpha-decay properties of neutron deficient isotopes 257- 253 104 and 258 106

. Z. Phys. A: Hadrons Nucl. 359, 415-425 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1007/s002180050422Decay properties of neutron-deficient isotopes 256, 257 Db, 255 Rf, 252, 253 Lr

. Eur. Phys. J. A 12, 57-67 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100500170039The new isotopes 258 105, 257 105, 254 lr and 253 lr

. Z. Phys. A 322, 557-566 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01415134The isotopes 259 106, 260 106, and 261 106

. Z. Phys. A 322, 227-235 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01411887The new isotope 270 110 and its decay products 266 Hs and 262 Sg

. Eur. Phys. J. A 10, 5-10 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100500170137Element 107

. Z. Phys. A 333, 163-175 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01565147Evidence for the possible synthesis of element 110 produced by the 59Co+209Bi reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 51, R2293-R2297 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.51.R2293Observation of the superheavy nuclide 271Ds

. Chin. Phys. Lett 29 (1),Systematics of production cross sections in 54Cr-induced fusion evaporation reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 110 (1),Superheavy nuclei: from predictions to discovery

. Physic. Scripta. 92 (2),Discovery of enhanced nuclear stability near the deformed shells N=162 and Z=108

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 624-627 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.624Synthesis of superheavy elements by cold fusion

. Radiochem. Acta. 99 (7-8), 405-428 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1524/ract.2011.1854Measurements of cross sections for the fusion-evaporation reactions 244Pu(48Ca,xn)292-x114 and 245Cm(48Ca,xn)293-x116

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Search for superheavy nuclei

. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 63 (1), 383-405 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-102912-144535Spontaneous-fission half-lives of deformed superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 1871-1880 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.1871Properties of the hypothetical spherical superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 56, 812-824 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.56.812Synthesis of the isotope 282113 in the 237Np+48Ca fusion reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Spectroscopy along flerovium decay chains: discovery of 280Ds and an excited state in 282Cn

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,New isotope 286Mc produced in the 243Am+48Ca reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 106,New isotope 276Ds and its decay products 272Hs and 268Sg from the 232Th+48Ca reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Super-heavy element research

. Rep. Prog. Phys.. 78(3),Discovery of isotopes of elements with Z≥100

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 99 (3), 312-344 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2012.03.003Super heavy elements - experimental developments

. EPJ Web Conf. 182, 02091 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201818202091Status and prospect of super heavy nuclei research at IMP

. Nucl. Phys. Rev. 23(4), 359-368 (2006). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.23.04.359Introduction of the heavy ion research facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL)

. J. Instrum. 15(12),Present status of HIRFL complex in Lanzhou

. JINST 1401(1),α decay of the new isotope 204Ac

. Phys. Lett. B 834,α decay of the new neutron-deficient isotope 205Ac

. Phys. Rev. C 89,New isotope 207Th and odd-even staggering in α-decay energies for nuclei with Z>82 and N<126

. Phys. Rev. C 105,New α-emitting isotope 214U and abnormal enhancement of α-particle clustering in lightest uranium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,α-decay properties of the new isotope 216U

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Alpha decay properties of the semi-magic nucleus 219Np

. Phys. Lett. B 777, 212-216 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.12.017New isotope 220Np: probing the robustness of the N=126 shell closure in neptunium

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Short-lived α-emitting isotope 222Np and the stability of the N=126 magic shell

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125,New short-lived isotope 223Np and the absence of the Z=92 subshell closure near N=126

. Phys. Lett. B 771, 303-308 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.03.074Identification of the new isotope 224Np

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Results and perspectives for study of heavy and super-heavy nuclei and elements at IMP/CAS

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58(8), 158 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00811-wDiscovery of new isotopes 160Os and 156W: revealing enhanced stability of the N=82 shell closure on the neutron-deficient side

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132,α -decay properties of new neutron-deficient isotope 203Ac

. Phys. Lett. B 850,Longitudinal beam diagnostics R&D at GSI-UNILAC

. in: 15th international conference on heavy ion accelerator technology (HIAT’22), 2022, pp. 144-149. https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-HIAT2022-TH2I2High brilliance uranium beams for the GSI FAIR

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 20,High brilliance beam investigations at the universal linear accelerator

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 25,Upgrade program of the high current heavy ion UNILAC as an injector for FAIR

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res. A 577(1), 211-214 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2007.02.054Synthesis of new superheavy nuclei

. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 58(3), 392-399 (2022). https://doi.org/10.12202/j.0476-0301.2022082SHE Research at RIKEN Nishina Center

. Acta. Phys. Polon. Supp. 17(3), 3-A21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.5506/APhysPolBSupp.17.3-A21Facility upgrade for superheavy-element research at RIKEN

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58(12), 238 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00888-3Start-Up of the DC-280 cyclotron, the basic facility of the factory of superheavy elements of the laboratory of nuclear reactions at the joint institute for nuclear research

. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 16, 866-875 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477119060177DC-280 cyclotron for factory of super heavy elements experimental results

. in: Proc. of 12th Int. Particle Acc. Conf.(IPAC2021), 2021, pp. 4126-4129. https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-IPAC2021-THPAB182The new DC-280 cyclotron. status and road map

. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 15, 809-813 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477118070373SHE factory: cyclotron facility for Super Heavy Elements Research

. in: International Conference on Cyclotrons and their Applications (22nd), 2020.The 88-Inch Cyclotron: A one-stop facility for electronics radiation and detector testing

. Meas. 127, 580-587 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2017.10.018Heavy ion beam physics at Facility for Rare Isotope Beams

. J. Instrum. 15(12),Crossing N=28 toward the neutron drip line: first measurement of Half-Lives at FRIB

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129,Acceleration of uranium beam to record power of 10.4 kW and observation of new isotopes at Facility for Rare Isotope Beams

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 27,Accelerator commissioning and rare isotope identification at the facility for rare isotope beams

. Mod. Phys. Lett. 37(09),Status of the high-intensity heavy-ion accelerator facility in China

. AAPPS Bulletin 32(1), 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-022-00064-1Design study of charge-stripping scheme of heavy ion beams for HIAF-BRing

. 35(5), 46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01397-2Huizhou accelerator complex facility and its future development

. Sci. Sin-Phys. Mech. As 50(11),HIAF: New opportunities for atomic physics with highly charged heavy ions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. B 408, 169-173 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2017.03.129The FAIR Heavy Ion Synchrotron SIS100

. J. Instrum. 15(12),NICA Booster: a new-generation superconducting synchrotron

. Uspekhi Fizicheskikh Nauk 193(2), 206-225 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3367/UFNe.2021.12.039138Eurisol design study: towards an Ultimate ISOL Facility for Europe

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 18(10), 1960-1964 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301309014081Nuclei in the "Island of Stability" of superheavy elements

. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. 337,Research at SHIP – status and perspectives

. EPJ Web Conf. 38, 01002 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/20123801002Separator for heavy eLement spectroscopy – velocity filter SHELS

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. B 376, 140-143 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2016.03.045DGFRS-2—A gas-filled recoil separator for the Dubna super heavy element factory

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. A 1033,The TransActinide separator and chemistry apparatus (TASCA) at GSI – Optimization of ion-optical structures and magnet designs

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. B 266(19), 4153-4161 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2008.05.132The Berkeley gas-filled separator

. in: AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 455,Gas-filled recoil ion separator GARIS-II

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. B 317, 311-314 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.05.085HIRFL Today

. Nucl. Phys. A 805(1), 533c-540c (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.02.292First superheavy element experiments at the GSI recoil separator TASCA: The production and decay of element 114 in the 244Pu(48Ca,3-4n) reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Development of digital electronics for the search of SHE nuclei using GARIS-II/III at RIKEN

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. A 1049,Ion-optical design and multiparticle tracking in 3D magnetic field of the gas-filled recoil separator SHANS2 at CAFE2

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. A 1004A gas-filled recoil separator, SHANS2, at the China Accelerator Facility for Superheavy Elements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. A 1050,Production cross sections of 243-248No isotopes in fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Improved quantum molecular dynamics model and its applications to fusion reaction near barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Fusion enhancement in the collisions with 44Ca beams and the production of neutron-deficient 245–250Lr isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Microscopic study of the hot-fusion reaction 48Ca+238U with the constraints from time-dependent hartree-fock theory

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Novel role of superfluidity in low-energy nuclear reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119,Entrance channel dynamics of hot and cold fusion reactions leading to superheavy elements

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Time-dependent Hartree-Fock plus Langevin approach for hot fusion reactions to synthesize the Z=120 superheavy element

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Systematic study of capture thresholds with time dependent Hartree-Fock theory

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Synthesis of superheavy element 120 via 50Ti+ACf hot fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Exploring the production of new superheavy nuclei with proton and α-particle evaporation channels

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Possibility to form Z=120 via the 64Ni+238U reaction using the dynamical cluster-decay model

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Predicted cross sections for the synthesis of Z=120 fusion via 54Cr+248Cm and 50Ti+249Cf target-projectile combinations

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Residue cross sections of 50Ti-induced fusion reactions based on the two-step model

. Eur. Phys. J. A 52, 35-39 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2016-16035-0Isospin dependence of reactions 48Ca+ 243-251Bk

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 17, 66-79 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301308011768Elimination of fast variables and initial slip: a new mechanism for fusion hindrance in heavy-ion collisions

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys 46(11),Synthesis of superheavy elements: Uncertainty analysis to improve the predictive power of reaction models

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Model for compound nucleus formation in various heavy-ion systems

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Cross sections for the production of superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 944, 257-307 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2015.02.010Description of fusion and evaporation residue formation cross sections in reactions leading to the formation of element Z=122 within the Langevin approach

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Dynamical mechanism of fusion hindrance in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Effects of neck and nuclear orientations on the mass drift in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Theoretical study of the synthesis of superheavy nuclei with Z=119 and 120 in heavy-ion reactions with trans-uranium targets

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Influence of the nuclear dynamical deformation on production cross sections of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Production cross sections of superheavy nuclei based on dinuclear system model

. Nucl. Phys. A 771, 50-67 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2006.03.002Orientation effects on evaporation residue cross sections in 48Ca-induced hot fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Possibilities for the synthesis of superheavy element Z= 121 in fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech 35(6), 95 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01452-yPredictions of synthesizing elements with Z=119 and 120 in fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Production of unknown Fl isotopes in proton evaporation channels within the dinuclear system model

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Synthesis of neutron-rich superheavy nuclei with radioactive beams within the dinuclear system model

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Deformation and orientation effects in the driving potential of the dinuclear model

. Eur. Phys. J. A 24(2), 223-229 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2004-10138-1Cluster emission in massive transfer reactions based on dinuclear system model

, Nucl. Tech. 46,Heavy-ion collisions and fission dynamics with the time-dependent Hartree–Fock theory and its extensions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 103, 19-66 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2018.07.002TDHF theory and its extensions for the multinucleon transfer reaction: a mini review

. Front. Phys. 7, 20 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2019.00020Fusion and quasifission dynamics in the reactions 48Ca+249Bk and 50Ti+249Bk using a time-dependent Hartree-Fock approach

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Isotopic trends of quasifission and fusion-fission in the reactions 48Ca+239,244Pu

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Transport model comparison studies of intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 125,“quantum” molecular dynamics—a dynamical microscopic n-body approach to investigate fragment formation and the nuclear equation of state in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rep. 202(5), 233-360 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(91)90094-3Survival probability of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Exploring the optimal way to produce Z=100-106 neutron-rich nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Fusion-fission reactions with a modified Woods-Saxon potential

. Phys. Rev. C 77,KEWPIE2: A cascade code for the study of dynamical decay of excited nuclei

. Comp. Phys. Comm 200, 381-399 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2015.12.003Three lectures on macroscopic aspects of nuclear dynamics

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 4, 383-450 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6410(80)90014-9Dynamical aspects of nucleus-nucleus collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 391, 471-504 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90621-2The dynamics of the fusion of two nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 376(2), 275-291 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90065-3Dynamical hindrance to compound-nucleus formation in heavy-ion reactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 459(1), 145-172 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(86)90061-8What is the most realistic mechanism of the compound nucleus formation in the complete fusion of two massive nuclei?

. Acta. Physica Hungarica Series A: Heavy Ion Phys. 19, 67-75 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1556/APH.19.2004.1-2.10Isospin dependence of reactions 48Ca + 243-251Bk

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 17, 66-79 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301308011768Hot fusion reactions with deformed nuclei for synthesis of superheavy nuclei: An extension of the fusion-by-diffusion model

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Progress in transport models of heavy-ion collisions for the synthesis of superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46(08),Predictions for the synthesis of unknown 279-281Nh and 287,288Nh isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 111,Evaporation residue cross sections of superheavy nuclei based on optimized nuclear data

. Chin. Phys. C 47(12),Bayesian uncertainty quantification for synthesizing superheavy elements

. Phys. Lett. B 858,Constraining the Woods-Saxon potential in fusion reactions based on the neural network

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Multiple constraints on nuclear mass formulas for reliable extrapolations

. Phys. Rev. C 107(4),Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: Nucleon collectivization as a mechanism for compound nucleus formation

. Phys. Rev. C 64,Theoretical study of evaporation-residue cross sections of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: A search for new production reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Systematics of fusion probability in “hot” fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Production cross sections of superheavy elements Z=119 and 120 in hot fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Synthesis of transactinide nuclei using radioactive beams

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Compound nucleus formation in reactions between massive nuclei: Fusion barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 51, 2635-2645 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.51.2635Law of optimal incident energy for synthesizing superheavy elements in hot fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. Res. 5,Attempt to produce element 120 in the 244Pu+58Fe reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 79,Review of even element super-heavy nuclei and search for element 120

. Eur. Phys. J. A. 52(6), 1-34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2016-16116-0Review of even element super-heavy nuclei and search for element 120

. Eur. Phys. J. A 52, 1-34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2016-16180-4Some critical remarks on a sequence of events interpreted to possibly originate from a decay chain of an element 120 isotope

. Eur. Phys. J. A 53(6), 1-9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2017-12307-5Search for elements 119 and 120

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Probing Optimal Reaction Energy for Synthesis of Element 119 from 51V+248Cm Reaction with Quasielastic Barrier Distribution Measurement

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 91(8),Toward the Discovery of New Elements: Production of Livermorium (Z=116) with 50Ti

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133(17),Heaviest element yet within reach after major breakthrough

. Nature 632(8023), 16-17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-02416-3Actinide targets for the synthesis of superheavy nuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59(12), 304 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-01144-ySynthesis and decay process of superheavy nuclei with Z= 119-122 via hot-fusion reactions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 52(9), 287 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2016-16287-6Examination of promising reactions with 241Am and 244Cm targets for the synthesis of new superheavy elements within the dinuclear system model with a dynamical potential energy surface

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Investigation of fusion probabilities in the reactions with 52,54Cr, 64Ni, and 68Zn ions leading to the formation of Z=120 superheavy composite systems

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Optimal ways to produce heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58(6), 111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00764-0Predictions of synthesizing element 119 and 120

. Sci. Chin. Phys. Mech 54, 61-66 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-011-4436-4Systematic study of probable target-projectile combinations for the synthesis of Z = 120 isotopes using the Skyrme energy density formalism

. Nucl. Phys. A 1027,Possibilities for synthesis of new isotopes of superheavy elements in fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Optimal colliding energy for the synthesis of a superheavy element with Z=119

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Zeptosecond contact times for element Z=120 synthesis

. Phys. Lett. B 808,High energy alpha particle emission as a challenging mechanism for synthesis of very heavy nuclei

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1643(1),Random forest-based prediction of decay modes and half-lives of superheavy nuclei

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01354-5Predictions of the decay properties of the superheavy nuclei 293, 294119 and 294, 295120

, Nucl. Tech. 46, 114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2023.hjs.46.080011High quality microscopic nuclear masses of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Lett. B 851,Accuracy versus predictive power in nuclear mass tabulations

. Phys. Rev. C 106(2),Refining the nuclear mass model via the α decay energy

. Phys. Rev. C 104(6),Influence of nuclear basic data on the calculation of production cross sections of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Assessing the impact of nuclear mass models on the prediction of synthesis cross sections for superheavy elements

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Survival probabilities of compound superheavy nuclei towards element 119

. (2024). arXiv:2408.07371Development of the detector system for β-decay spectroscopy at the KEK Isotope Separation System

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Phys. Res, Sect. B 376, 338-340 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2016.01.041How to extend the chart of nuclides?

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 1-51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00046-7First direct measurements of superheavy-element mass numbers

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Isotope production and materials irradiation research studies to support HFIR LEU conversion assessment, Tech. rep.

,Summary of plutonium-238 production alternatives analysis final report, Tech. rep.

,Production of medical radionuclides in Russia: Status and future—a review

. Appl. Radiat. Isot 84, 48-56 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.11.025The future Jules Horowitz material test reactor: A major European research infrastructure for sustaining the international irradiation capacity

. in:An optimization design study of producing transuranic nuclides in high flux reactor

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 55(8), 2723-2733 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2023.04.023On the nuclear structure and stability of heavy and superheavy elements

. Nucl. Phys. A 131(1), 1-66 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(69)90809-4Survey of single-particle states in the mass region A>228

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 49(4), 833-891 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.49.833Progress on production cross-sections of unknown nuclei in fusion evaporation reactions and multinucleon transfer reactions

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 32(01),The synthesis of new neutron-rich heavy nuclei

. Front. Phys. 7, (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2019.00023Relaxation of angular momentum in fission and quasifission reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 41, 1495-1511 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.41.1495Characteristic time for mass asymmetry relaxation in quasi-fission reactions

. europhysics letters 1(3), 113 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/1/3/004Fission and quasifission in u-induced reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 36, 115-142 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.36.115Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: obstacles and opportunities

. EPJ Web Conf. 86, 00066 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/20158600066Detailed study of multinucleon transfer features in the 136Xe+238U reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Multinucleon transfer reactions: a mini-review of recent advances

. Front. Phys. 10,The RIKEN RI Beam Factory Project: A status report

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods B 261(1), 1009-1013 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2007.04.174Status of the SPIRAL2 Project

in: Proc. 10th Int. Particle Accelerator Conf. (IPAC’19), 2019, pp. 844-847. https://doi.org/10.18429/JACoW-IPAC2019-MOPTS005Progress and perspective of the research on exotic structures of unstable nuclei

, Nucl. Tech. 46, 189 (2023). https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2023.hjs.46.080020Theoretical study on production of unknown neutron-deficient 280–283Fl and neutron-rich 290–292Fl isotopes by fusion reactions Phys

. Rev. C 98,Possibility of reaching the predicted center of the “island of stability” via the radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35(9), 161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01542-xExperimental survey of the production of α-decaying heavy elements in 238U+232Th reactions at 7.5–6.1 Mev/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Observation of new neutron-deficient isotopes with Z≥ 92 in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 748, 199-203 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2015.07.006Discovery of new isotope 241U and systematic high-precision atomic mass measurements of neutron-rich Pa-Pu nuclei produced via multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Optimal detection angles for producing N=126 neutron-rich isotones in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. Res. 5,Probing the production mechanism of neutron-rich nuclei in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Influence of neutron excess of projectile on multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 785, 221-225 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.08.049Effect of cluster transfer on the production of neutron-rich nuclides near N=126 in multinucleon-transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Role of the quasifission yields in the multinucleon transfer reactions of 136Xe+208Pb

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Multinucleon transfer in the 136Xe+208Pb reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Predicting the production of neutron-rich heavy nuclei in multinucleon transfer reactions using a semi-classical model including evaporation and fission competition, GRAZING-F

. Phys. Rev. C 91,136Xe+208Pb reaction: A test of models of multinucleon transfer reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Microscopic study of the production of neutron-rich isotopes near N=126 in the multinucleon transfer reactions 78,82,86Kr+208Pb

. Phys. Rev. C 109,New neutron-rich isotope production in 154Sm+160Gd

. Phys. Lett. B 760, 236-241 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.06.073Multinucleon transfer as a method for production of new heavy neutron-enriched isotopes of transuranium elements

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58(3), 41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00688-9Synthesis of transuranium nuclei in multinucleon transfer reactions at near-barrier energies

. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 16(6), 667-670 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477119060475Multinucleon transfer with time-dependent covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Production of proton-rich actinide nuclei in the multinucleon transfer reaction 58Ni+ 232Th