Introduction

The concept of synthesizing new superheavy elements through neutron-rich nuclei-induced fusion reactions is very attractive [1]. However, their structural characteristics can have a significant impact on induced fusion reactions. Therefore, it is of great importance to conduct in-depth experimental and theoretical studies on the mechanisms of the fusion reactions of neutron-rich nuclei. There are two contradictory theoretical viewpoints regarding the fusion reactions of halo nuclei near the Coulomb barrier: one suggests that halo nuclei and weakly bound nuclei themselves have much larger nuclear radii than predicted by the general liquid drop model, which would lower the fusion barrier and increase the fusion cross-section [2], and the other argues that the unstable structure of halo nuclei due to fragmentation leads to a smaller fusion cross-section [3-5]. Different theoretical models have shown different results [3-9]. The partial fusion process of weakly bound nuclei is complex, and its reaction mechanism is not well understood to date [10, 11].

The fragmentation of projectiles with low binding energies is known to have a significant impact on fusion reactions, resulting in distinct fusion pathways. Specifically, the complete fusion (CF) process arises from the successful capture of the entire projectile by the target. It should be noted that complete fusion (CF) may take on two distinct forms: direct CF, where fusion occurs without prior projectile fragmentation, and sequential CF, where all projectile fragments are captured after their fragmentation. If only certain fragments are captured, while others evade capture, the process is deemed incomplete fusion (ICF). The sum of complete and incomplete fusion reactions is called the total fusion (TF) [10, 12-14].

At present, the majority of both experimental and theoretical studies on fusion reaction mechanisms induced by halo and weakly bound nuclei have focused on comparatively heavier reaction systems [2, 10, 15-19], with less attention given to light nuclear reaction systems. Within these lighter systems, the reduction in Coulomb energy makes other effects more pronounced. For example, the effects of halo and cluster structures, which lead to an increase in the nuclear radii, may have a more significant impact on fusion reactions. In addition, the detection of fragmentation products from the projectile nuclei is more feasible. The fragmentation effects of halo and weakly bound nuclei continue to be an important research topic, both experimentally and theoretically. However, studies on the role of cluster structure effects in fusion reactions of light systems are scarce. The study of light nuclei and their clustering phenomena, such as α-cluster structures, has profound implications for understanding nuclear reaction mechanisms, particularly near the Coulomb barrier. These exotic configurations can significantly modify the fusion barrier and cross section, affecting the reaction dynamics [20-22].

Weakly bound nuclei, such as 6Li (α + d cluster, 1.47 MeV breakup threshold) and 7Li (α + t cluster, 2.47 MeV), exemplify how clustering governs the reaction outcomes. The different breakup energies of these isotopes profoundly influence the reaction mechanisms, particularly the competition between CF and ICF; lower thresholds enhance breakup and promote ICF, often suppressing CF [23, 24]. Further support for the role of cluster structures in light nuclei comes from previous studies such as Guo et al. [25], which emphasized that well-developed α-cluster configurations in nuclei, such as 6Li and 7Li, significantly influence the reaction dynamics near the Coulomb barrier. Their analysis showed that the presence of cluster structures enhances breakup probabilities and can alter the distribution between CF and ICF processes. Specifically, Guo et al. highlighted that for weakly bound projectiles, the cluster nature not only facilitates certain breakup channels but may also impact transfer reactions and overall fusion yields. These findings are consistent with our calculated results, where the effects of clustering contribute to increased fragmentation and cross sections of the ICF, particularly for 6Li. Thus, the interplay between nuclear clustering and reaction mechanisms remains a key factor in understanding barrier fusion with light and weakly bound nuclei.

Experimentally, researchers have initially focused on the fusion reaction mechanisms of weakly bound nuclei in light nuclear systems based on the available experimental conditions. However, the fusion cross-section results measured using different experimental approaches are inconsistent. Measurements of the fusion reaction cross-sections in light nuclear systems have been conducted either by directly detecting the residues using gas detectors with

Theoretically, the majority of studies on fusion reaction mechanisms have used the optical model (OM) [27] and CDCC [11, 28, 29]. However, these models do not consider the effects of secondary decay of the fusion reaction fragments. In contrast, the anti-symmetrized molecular dynamics (AMD) model can represent the cluster structure of the initial collision nuclei and reflect the dynamic evolution process during fragment formation. Moreover, significant success has been achieved in studying the symmetry energy and phase transitions of nuclear matter through heavy ion reactions in the Fermi energy domain [30-34].

While the understanding of weakly bound nuclear reactions is ongoing, direct comparative studies isolating the impact of the projectile cluster structure on fusion channels are scarce. This study addresses this gap by comparing 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C systems. These systems form the same compound nucleus 19F at similar excitation energies, yet differ significantly in their lithium projectile’s internal cluster structure and breakup properties. By analyzing their TF, CF, and ICF contributions, the influence of the projectile structure on the reaction pathways can be quantified, offering insights into clustering, weak binding, and CF/ICF competition. Therefore, this study adopted the AMD/DS version [35]. Owing to the selection of a finite coherence time, this version allows the system dynamics to exhibit both diffusion (D) and wave packet shrinking (S) effects, as manifested in the mean-field propagation. We present the results of our investigation of the fusion reactions of the 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C systems near the Coulomb barrier, as determined by AMD simulations. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The AMD models are briefly described in Sect. 3. Detailed comparisons of the fusion cross-sections with experimental data, time evolution of the density distributions, and fusion channel distribution are presented in Sect. 4. Finally, a summary is provided in Sect. 5.

AMD descriptions

In the framework of the AMD model [35], the wave function associated with a reaction involving A nucleons is expressed as a Slater determinant comprising Gaussian wave packets,

Owing to quantum mechanical effects, heavy-ion collisions are inherently stochastic at the microscopic level. The positions and momenta of individual particles fluctuated randomly. Therefore, including a stochastic term is crucial in modeling heavy-ion collisions, because it enables a diverse range of final states to be generated from a single initial state. In typical implementations, the stochasticity required for realistic heavy-ion collision simulations is introduced through randomized nucleon-nucleon interactions. However, the AMD model has been augmented to facilitate the quantum-mechanical branching of a single initial state into many possible final states induced by mechanisms beyond simple nucleon-nucleon scattering. In the AMD model, the time evolution of the centroids of the Gaussian wave packets, which represent the nucleons, follows the Vlasov equation and describes the dynamics of an ensemble of noninteracting particles under the influence of an averaged mean-field potential. Propagating the wave packets using the Vlasov equation enables each nucleon to move independently in the mean field generated collectively by the entire system. This approach provides a self-consistent framework to simulate the smooth evolution of single-particle wave functions along classical trajectories while preserving the quantum-mechanical uncertainties inherent in the Gaussian wave-packet representation. Vlasov dynamics approximates collisionless motion, allowing the AMD model to efficiently calculate the many-body time development through the mean-field potential before modeling granular collisions stochastically. The onset of decoherence at the time point denoted τ is postulated to induce the decomposition of the single-particle wave functions into a set of Gaussian wave packets, engendering a stochastic branching process, to consider the quantum effects inherited in the Gaussian wave packet formalism.

The single-particle wave function can diffuse in the context of one-body mean-field propagation. Upon reaching the point of decoherence, it becomes localized, thereby generating many-body correlations. By incorporating quantum branching through one-body mean-field propagation, the ability of the AMD approach to model reactions with numerous possible channels, such as multifragmentation phenomena, was significantly enhanced. This extension of the AMD model, often referred to as AMD-V, is alternatively labeled as AMD/D (for diffusion). An additional enhancement of the AMD approach, referred to as AMD/DS (indicating diffusion with shrinking), allows the dynamic contraction of single-particle wave functions, in addition to their diffusive dispersion [35]. Unlike the AMD/D model, which focuses solely on diffusion and manifests the multifragmentation process, the incorporation of wave function shrinking counterbalances the expansion following the collision event, resulting in weakened post-collision dilatation compared with AMD/D. As a result, the AMD/DS improved the formation of heavier nuclear fragments, improving the agreement with the experimental fragment distribution data. The addition of a balance between the diffusive expansion and contraction of single-particle wave functions in AMD/DS allows for a more precise fragmentation control, resulting in a more realistic depiction of the experimentally observed reaction products.

AMD simulations

The barrier energies for the two reaction systems,6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C, are approximately 3.68 MeV and 3.63 MeV, respectively [23]. These values are considered when discussing the energy dependence of the measured and calculated fusion cross sections. The AMD/DS code was used in this study. Employing Gogny interaction, a well-regarded effective interaction in nuclear physics is known for its accuracy in predicting nuclear phenomena. This code is also used to generate the initial nuclei of several elements, namely 6,7Li and 12,13C. The computed binding energies and root-mean-square(RMS) radii of these nuclei were compared with their corresponding experimental values, as summarized in Table 1. The calculated values were in good agreement with the experimental measurements, except for the RMS radii of 6,7Li. For these isotopes, the calculated radii exceeded the empirical values by approximately 20%. However, more sophisticated AMD implementations, such as the approach described in Ref. [36], reproduce the experimentally observed binding energies, and the radii of 6,7Li, are in good agreement. These results show the distinct cluster structures d + α and t + α inherent to these light lithium species. Thus, while basic AMD models may overestimate certain spatial properties of 6,7Li, extensions to the framework can lead to improved agreement with the experimental data for energy and nuclear cluster configurations. However, caution is needed, as the fusion cross-section is closely related to the radius or cluster separation within the projectile, which remains challenging to describe accurately.

| nucleus | AMD Binding energy (MeV) | AMD rms (fm) | Exp. Binding energy (MeV) | Exp. rms (fm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6Li(d+α) | 35.15 | 3.15 | 31.99 | 2.59 |

| 7Li(t+α) | 40.00 | 3.02 | 39.24 | 2.43 |

| 12C | 92.24 | 2.53 | 92.16 | 2.47 |

| 13C | 104.77 | 2.55 | 97.11 | 2.46 |

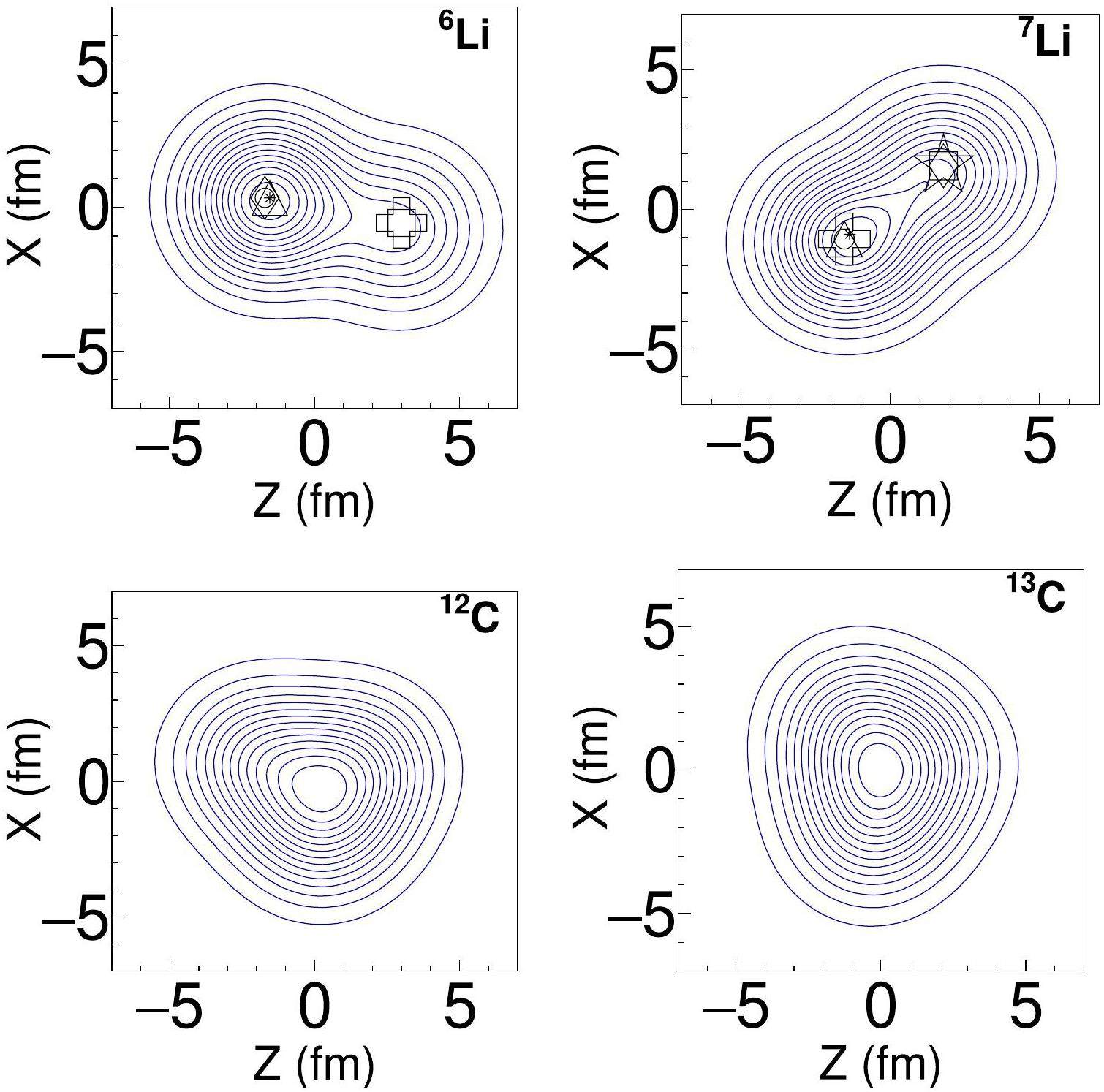

The spatial nucleon densities computed using the AMD framework are presented in Fig.1, with symbols denoting clusterized nucleon locations. The salient clustering of nucleons within the localized regions of the nuclear volume is evident in both the density profiles and localization plots. The calculations revealed tightly clustered substructures, indicative of developed alpha and deuteron/triton formations, corroborating significant deformation, particularly for 6Li and 7Li isotopes. Two distinct subgroups were unambiguously delineated, corresponding to an alpha cluster and a deuteron/triton moiety, respectively, consistent with the nuclear configuration d + α or t + α. In contrast, AMD computations of 12,13C [37, 38] showed minimal fragmentation into clustered subunits. The absence of clustered correlations manifests as more uniform, compact, and spherically symmetric spatial densities in these nuclei.

Using the initialized 6,7Li and 12,13C nuclei, AMD/DS calculations were performed to simulate the 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C fusion reactions across the center-of-mass energy range from 3 to 7.6. To facilitate a comparison between computational results and experimental values, dynamical evolutions are typically simulated for durations up to 300 fm/c. Subsequently, the GEMINI [39] code was employed as an afterburner to de-excite the primary emitting fragments to their ground states [30-34]. Simulations were conducted up to 2000 fm/c to enable full expansion of the system and asymptotic separation of fragments. This extended duration ensured the physical validity of the application of the coalescence technique for identifying light clusters in a dilute, post-reaction environment. This comprehensive dynamic treatment of multifragmentation is preferred to earlier termination (for example, 300 fm/c) and the subsequent use of statistical decay models such as GEMINI, as it directly captures the formation and evolution of fragments throughout the reaction. Subsequently, a phase-space coalescence technique was applied to identify emergent nuclear clusters. A universal coalescence radius of 5 fm in the coordinate space was adopted for all the energies. The charge (Z), mass (A), excitation energy, angular momentum, and velocity vectors were determined for each clustered fragment. The calculations ranged from 0 to 7 fm for the impact parameters, with a few fusion reactions beyond 7 fm.

Results and discussion

The experimental fusion cross-section data utilized here were obtained from [23, 24].The 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C reaction systems were obtained using beams from a 3 MV pelletron accelerator at the Institute of Physics, Bhubaneswar, impinging on enriched 13C(~60 μg/cm2) and natural 12C (~48 μg/cm2) targets, respectively. Fusion cross-sections were determined using the in-beam gamma-ray spectroscopy method, where the characteristic gamma rays of residual nuclei were detected by HPGe detectors positioned at 125° (and 90° for 6Li + 13C).

For the AMD simulations, the criterion of Z> 6 for the definition of TF events was chosen to ensure that only events were included, where the majority of the charge from the projectile and the target nuclei fused to form a single heavy fragment. For the systems studied (6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C), the combined charges (Z) of the projectile and the target were 9. By imposing Z> 6, peripheral reaction processes are effectively excluded, which typically result in fragments with a lower Z and focus on capturing events corresponding to total fusion. This approach provides a clear separation between the fusion and non-fusion reaction channels.

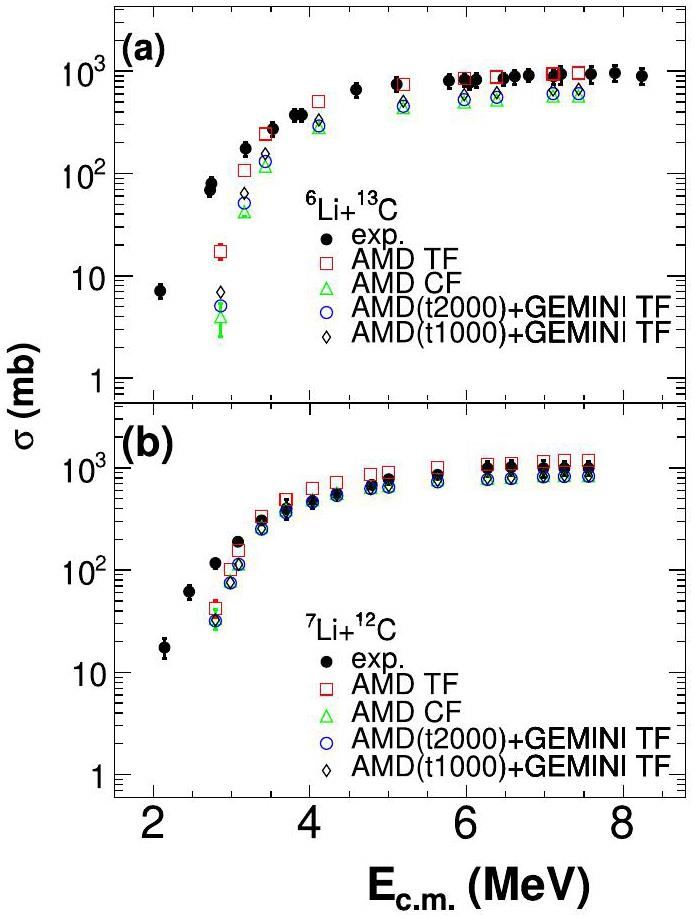

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the experimentally observed fusion cross sections (solid circles) with the calculated values. Those that emerged with Z>6 at the end of the AMD simulations are denoted as TF (open squares), and those with Z=9 (sum of projectile and target Z) are denoted as CF (open triangles).

The absolute fusion cross-sections of the TF predicted by the AMD simulations (open squares) demonstrate excellent quantitative agreement with the experimental measurements within uncertainties on an absolute scale for centers of mass Ecm larger than the barrier. The simulated cross-sections were calculated directly from the number of fusion events generated across the simulated impact parameter space. The experimental fusion cross-sections for both the 6Li+13C (a) and 7Li+12C (b) systems were accurately reproduced by TF (open squares) calculations at energies above the barrier. However, for the 6Li+13C system, the TF calculations significantly predicted the observed cross sections at energies below the barrier. This under-prediction is attributed to the inability of the current AMD implementation to model the quantum tunneling of clusters through the Coulomb barrier, a phenomenon that substantially enhances fusion at these low energies. Additionally, for CF, the formation cross-sections of CF in the primary AMD events are plotted by open triangle symbols. From Fig. 2, the differences in cross sections between AMD CF and AMD TF for the 6Li system are larger than those for the 7Li system. This observation suggests that the higher ICF fractions for reactions induced by 6Li compared to those induced by 7Li reflect that 6Li exhibits a more weakly bound cluster structure relative to 7Li. Weaker binding facilitates the breakup of 6Li into constituent clusters during collision. The calculated ICF probabilities directly reflect the stability of the nuclear structures. More fragile configurations are susceptible to dissociation into fragmented reaction pathways.

Figure 2 also presents the secondary decay results, filtered for atomic numbers (Z> 6), obtained by coupling the AMD code with the statistical decay code GEMINI. The GEMINI code was used to simulate the secondary decay of the primary reaction products generated in AMD simulations. The fusion cross-sections predicted by the combined AMD-GEMINI approach were underestimated compared to the experimental values. This discrepancy can be attributed to the inherent limitations of the GEMINI model, particularly its statistical framework, which may not sufficiently account for the dynamic effects of the de-excitation process. To ensure the robustness and convergence of the simulation results, additional calculations were performed by coupling AMD with GEMINI using a shorter stopping time (t=1000 fm/c) in addition to the t=2000 fm/c simulations presented in the manuscript. As shown in Fig. 3, the total fusion cross sections obtained with AMD(t=1000 fm/c)+GEMINI are in very good agreement with those obtained from AMD (t=2000 fm/c)+GEMINI across the entire energy range for both reaction systems. This confirms that the calculated results are stable for the choice of AMD stopping time. In our analysis, TF events, including both CF and ICF events, were used as inputs for GEMINI statistical decay calculations. However, it was observed that the TF cross-sections obtained from GEMINI corresponded only to the CF cross-sections from AMD. This suggests that during the decay process, contributions from ICF events were effectively decayed by the GEMINI. As a result, the TF cross-sections predicted by GEMINI were found to be lower than the experimental values, as only CF events survived after statistical decay.

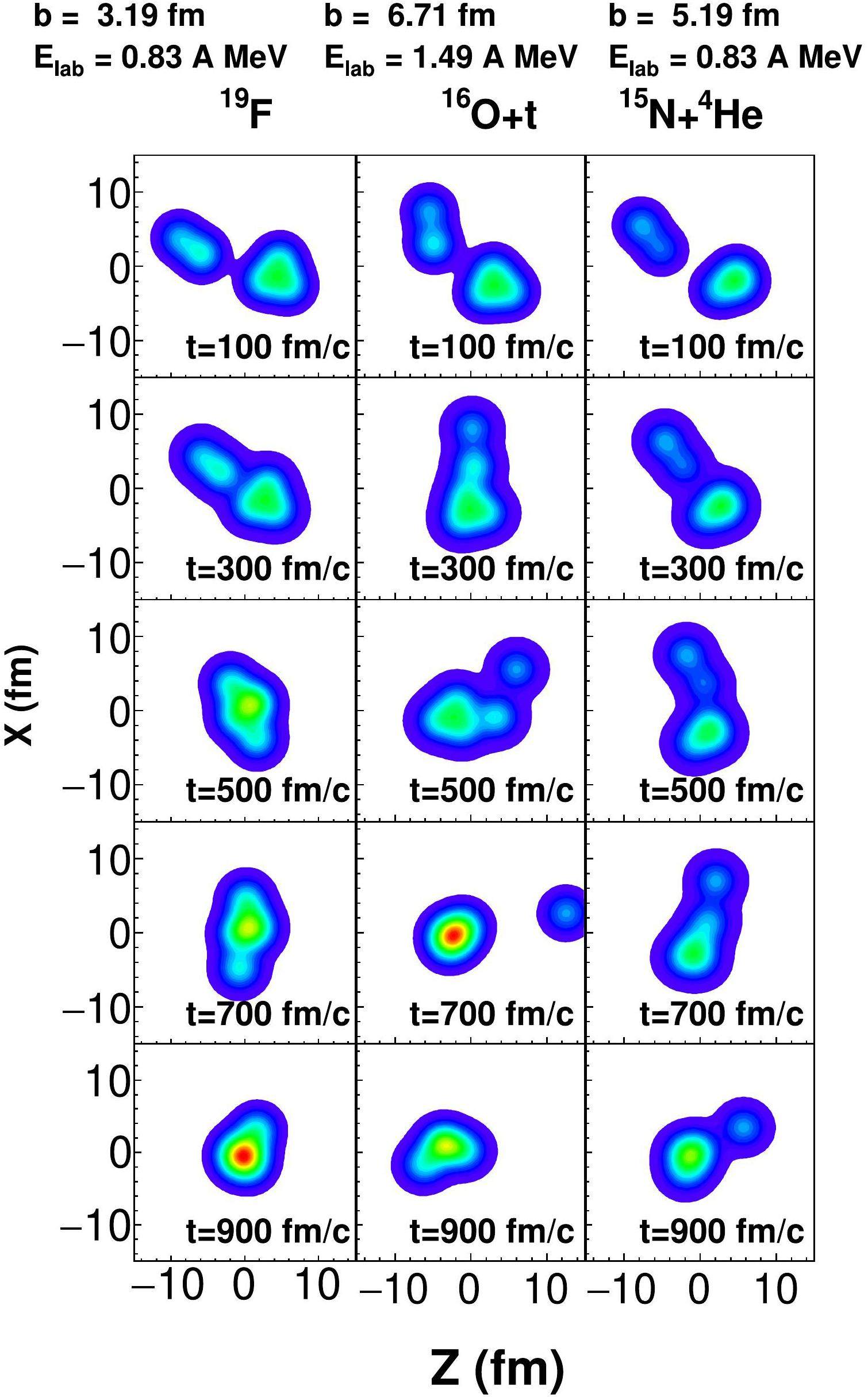

To investigate the dynamic mechanism of the fusion reactions, Fig. 3 exemplifies the temporal evolution of the nuclear densities exhibited in the CF and ICF reactions, as simulated within the AMD framework for 7Li + 12C system. The left panel depicts a CF event in which the entire projectile fuses with a target. The middle and right panels illustrate ICF processes distinguished by partial projectile absorption, and only the α particle or triton cluster is captured, whereas its deuteron/triton or α particle partner acts as a spectator fragment. Such binary transfers occur preferentially at higher impact parameters. For each energy, thousands to tens of thousands of collision events were simulated in proportion to the fusion cross-section across the designated impact parameter range. The tracking of the time-resolved density distributions revealed the microscopic dynamics underlying the CF and ICF reaction mechanisms in the AMD approach. Therefore, in Fig. 3, one can see the fusion processes occur around 300 fm/c, which leads to the formation of compound nuclei. Subsequently, in the context of ICF scenarios, these compound nuclei undergo disintegration around 500 fm/c.

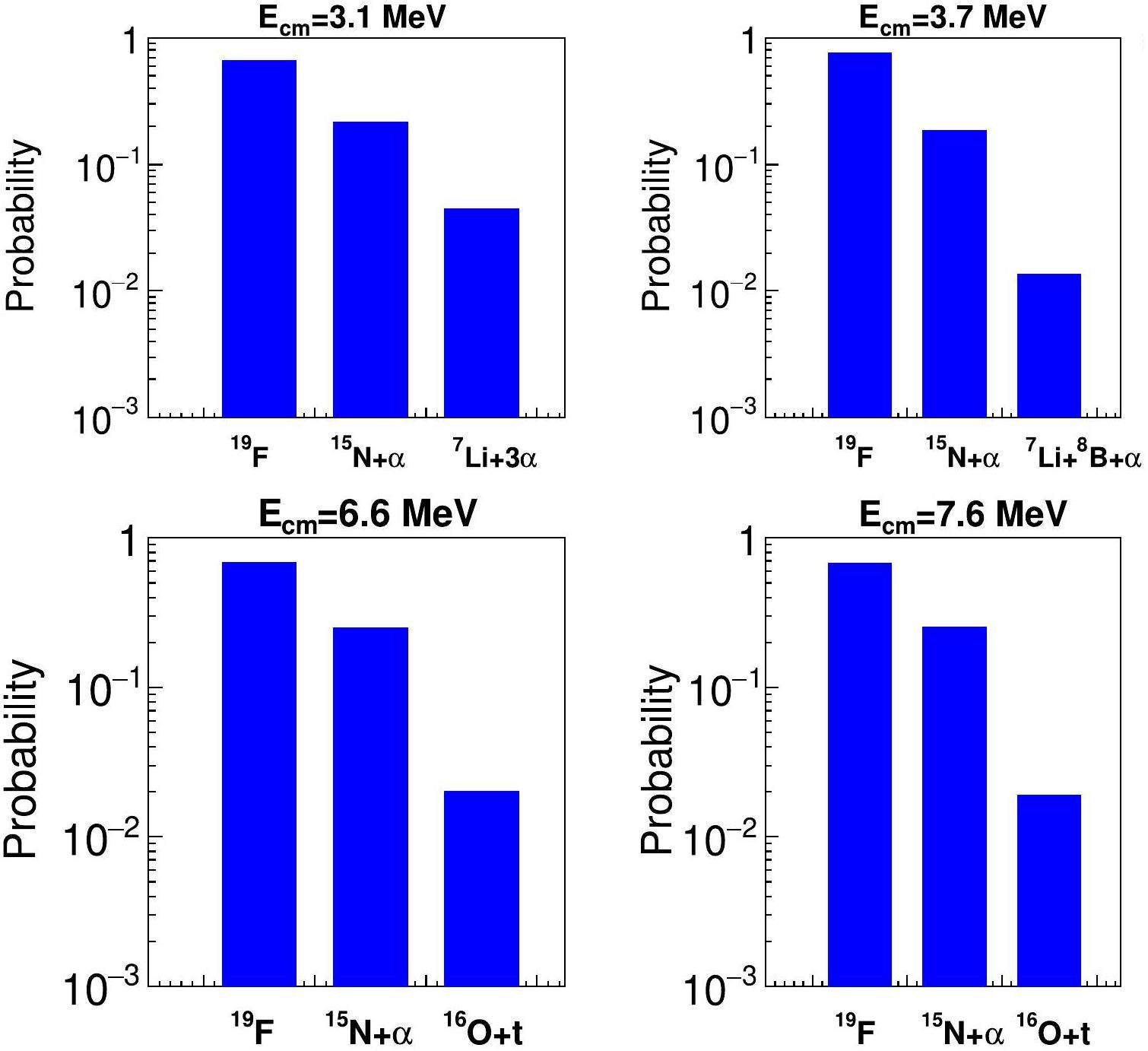

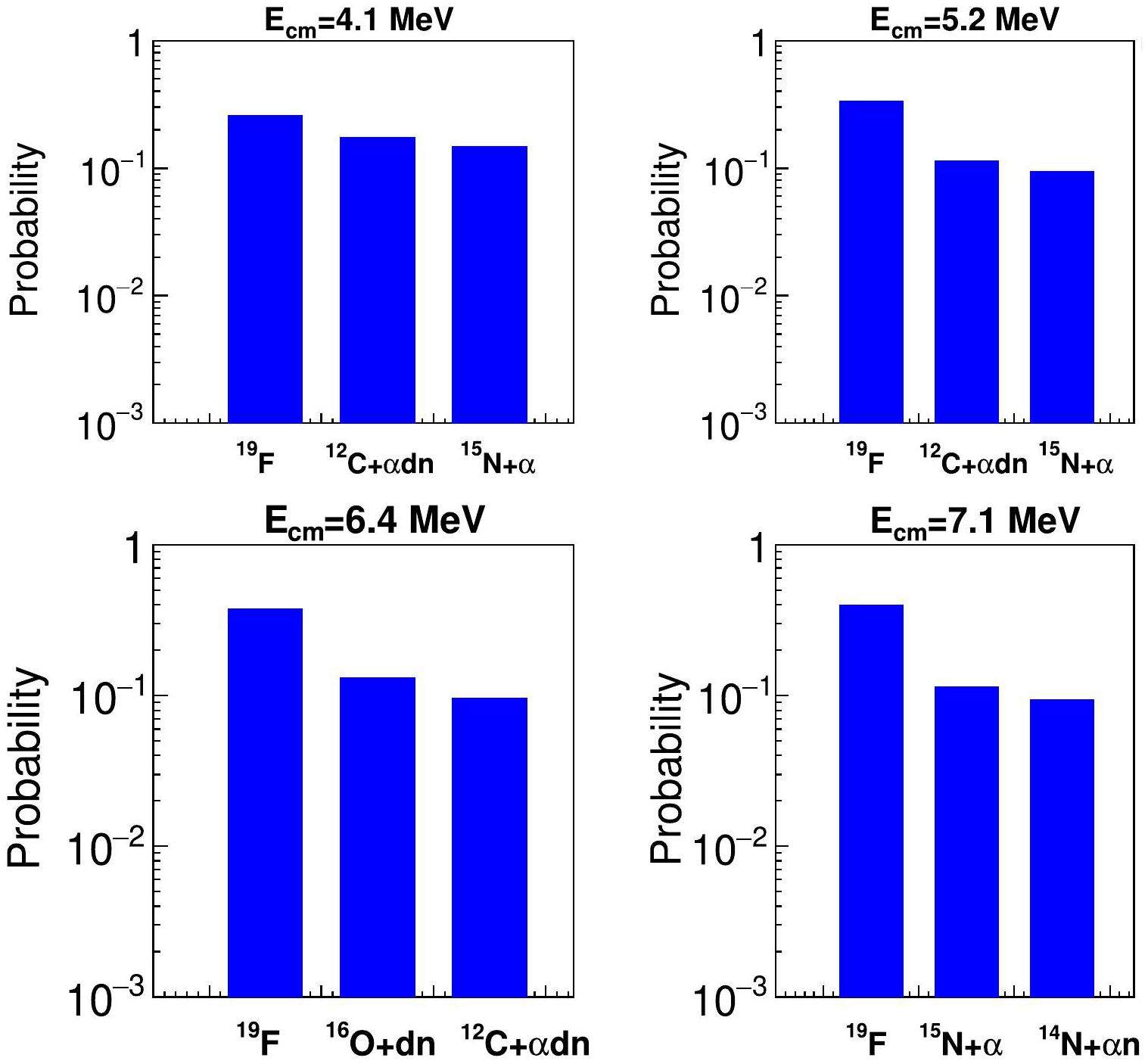

In Fig. 4, the fusion channel distribution in the primary stage is shown as a probability distribution for 7Li + 12C system. Only the top three major channels were plotted. The 19F and 15N+α channels dominate the fusion reaction at all selected energies. CF occurred in approximately 70–80% of these four cases. The third channel contribution is from different reactions at different incident energies, but their probabilities are only in the few percent range.

The distribution of the fusion channel in the primary stage for the 6Li + 13C system is shown in Fig. 5 as a probability distribution. Only the top three major channels were plotted for each incident energy. 19F formation (about 25% to 40%) is also the most probable channel at all selected energies as 7Li + 12C system. At lower incident energies of 4.1 MeV and 5.2 MeV, the other two dominant channels are 12C + α + d+ n and 15N+α. As the energy increases to 6.4 MeV, 16O + d + n and 12C + α + d + n remain the second and third largest, respectively. At the higher energies of 7.1 MeV, 15N + α and 14N + α+n dominate the second and third fusion reactions, respectively. In general, the CF leading to 19F is the primary reaction mechanism at all incident energies for 6Li + 13C.

However, 7Li + 12C and 6Li + 13C form the same compound nucleus 19F at the same excitation energy and produce similar total fusion cross-sections, as shown in Fig. 2, the results obtained from Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 reveal significant differences in the contributions of various reaction mechanisms. This indicates that the structure of the entrance channel has a substantial impact on the cross sections of the exit channel. Although the 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C systems share similarities in bulk properties, such as binding energies and rms radii, the substantial differences in their complete fusion (CF) characteristics, as shown in Figs. 2, 4, and 5 are attributed to variations in their cluster structure and breakup dynamics. Crucially, the breakup threshold of 6Li into α + d (1.47 MeV) is significantly lower than that of 7Li into α + t (2.47 MeV). This inherent instability of 6Li increases the probability of projectile breakup before fusion, channeling a larger fraction of reactions into incomplete fusion (ICF) pathways. Consequently, the relative contribution of complete fusion is considerably reduced for the 6Li + 13C system compared with the 7Li + 12C system, underscoring the strong influence of the structure of the entrance channel on the reaction.

AMD simulations for the 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C systems address the competing theories of fusion enhancement (owing to extended radii) versus suppression (due to breakup) for weakly bound nuclei. While both systems exhibit cluster structures, the more weakly bound 6Li exhibits a significant breakup into α+d, particularly near the barrier. This is evidenced by the higher fraction of ICF for 6Li than for 7Li. Although the TF cross-sections are similar, the CF fraction is notably lower for 6Li, indicating a more frequent prefusion breakup. Consequently, our results suggest that for these cluster structure projectiles, CF breakup and the associated suppression play a dominant role near the barrier, especially for 6Li.

Summary

In this study, the fusion dynamics of 6Li + 13C and 7Li + 12C systems near the Coulomb barrier were investigated using an AMD theoretical model. The AMD framework was first applied to generate ground-state configurations of the 6,7Li and 12,13C nuclei. The spatial density distributions and single-particle localization plots revealed pronounced cluster structures in 6Li and 7Li, characterized by well-developed d(t)+α configurations. In contrast, 12,13C exhibited more uniform densities without clear clustering. AMD simulations of the fusion reactions were then performed from 3 to 7.6 MeV center-of-mass energy. The total fusion cross sections predicted by AMD showed very good agreement with the experimental data above the Coulomb barrier. Below this barrier, calculations underestimated the measurements because of AMD’s inability of AMD to model quantum tunneling. Analysis of the reaction dynamics provided insight into the complete and incomplete fusion mechanisms. Complete fusion was found to be dominant at all incident energies, whereas partial capture of cluster constituents preferentially occurred through incomplete fusion at wider impact parameters. Cluster stability effects were also observed, with 6Li exhibiting a higher probability of incomplete fusion than the more robust clustered 7Li. In summary, the AMD model successfully described the fusion cross sections and reaction pathways in these light-exotic systems. The cluster structures within the projectiles influence the competition between the complete and incomplete fusion channels. The results highlight how intrinsic nuclear properties govern near-barrier fusion dynamics.

Theoretical study on fusion dynamics and evaporation residue cross sections for superheavy elements

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 24,Interaction potential and fusion of a halo nucleus

. Phys. Lett. B 265 23 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(91)90007-dNear-barrier fusion of 11Li with heavy spherical and deformed targets

. Phys. Rev. C 46, 377 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.46.377Giant resonance effects on heavy-ion fusion

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 2693 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.2693;Fusion of halo nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 588, 85c (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00104-9Effect of breakup reactions on the fusion of a halo nucleus

. Phys. Rev. C 47,Does the presence of 11Li breakup channels reduce the cross section for fusion processes?

Phys. Rev. C 50,Coulomb- and nuclear-induced breakup of halo nuclei at bombarding energies around the Coulomb barrier

. Nucl. Phys. A 597, 473 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00459-9Role of breakup processes in fusion enhancement of drip-line nuclei at energies below the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Investigation of the fusion mechanism in the 6Li-induced reaction on 93Nb

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Reaction mechanisms of the weakly bound nuclei 6,7Li and 7,9Be on light targets at near barrier energies

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58, 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-021-00655-wFusion and breakup of weakly bound nuclei

. Phys. Rep. 424, 1 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2005.10.006Recent developments in fusion and direct reactions with weakly bound nuclei

. Phys. Rep. 596, 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.08.001Comparative study of the effect of resonances of the weakly bound nuclei 6,7Li on total fusion with light to heavy mass targets

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Dynamics of complete and incomplete fusion of 6,7Li, 15N and 16O with a 209Bi target

. Eur. Phys. J. A 53, 212 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2017-12389-yNear barrier fusion excitation function of 6Li+208Pb

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Dynamical analysis on heavy-ion fusion reactions near Coulomb barrier

. Nucl. Phys. A 802, 91 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.01.022Fusion reactions with the one-neutron halo nucleus 15C

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106,Near-barrier fusion of the 8B+58Ni proton-halo system

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107,Progress on nuclear reactions and related nuclear structure at low energies

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46,Effects of alpha-clustering structure on nuclear reaction and relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46,Progress and perspective of the research on exotic structures of unstable nuclei

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46,7Li+12C and 7Li+13C fusion reactions at subbarrier energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 596, 299 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00392-4Fusion cross sections for 6Li+12C and 6Li+13C reactions at low energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 635, 305 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0375-9474(98)00164-xNegligible suppression of the complete fusion of 6,7Li on light targets, at energies above the barrier

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Is fusion inhibited for weakly bound nuclei?

Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 30 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.30Absence of fusion suppression due to breakup in the 12C+7Li reaction

. Phys. Lett. B 526, 295 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0370-2693(01)01505-2Non-frozen process of heavy-ion fusion reactions at deep sub-barrier energies

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33 132 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01114-xEffect of continuum couplings in fusion of halo 11Be on 208Pb around the Coulomb barrier

. Phys. Rev. C65,Reaction mechanisms and multifragmentation processes in 64Zn+58Ni at 35 A-79 AMeV

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Reaction dynamics and multifragmentation in Fermi energy heavy ion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Isobaric yield ratios and the symmetry energy in heavy-ion reactions near the Fermi energy

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Power law behavior of the isotope yield distributions in the multifragmentation regime of heavy ion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Isospin dependence of the nuclear equation of state near the critical point

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Antisymmetrized molecular dynamics for heavy ion collisions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 53, 501 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2004.05.002Neutron-rich B isotopes studied with antisymmetrized molecular dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 647 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.647The structure of ground and excited states of 12C

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 117, 655 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.117.655Hoyle-analog state in 13C studied with antisymmetrized molecular dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Systematics of complex fragment emission in niobium-induced reactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 483, 371 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(88)90542-8The authors declare that they have no competing interests.