Introduction

Relativistic heavy-ion collisions provide a unique laboratory for studying quantum chromodynamics (QCD) under extreme conditions, including the formation of quark-gluon plasma (QGP) [1]. Extensive studies have been conducted at both RHIC and LHC energies across various collision systems to investigate the properties of the QGP matter [2-7]. Among various collision systems, isobaric collisions, such as

The two-particle momentum correlation function, known as femtoscopy, originating from Hanbury-Brown Twiss (HBT) interferometry [22], is a powerful tool for accessing the expanding source dynamics of heavy-ion physics [23-27]. Femtoscopy in relativistic heavy-ion collisions extracts space-time information about particle emission sources and probes collision dynamics. Studies have been performed on the momentum correlation of various particle species, including mesons, nucleons, light charged particles, and even antiprotons, revealing details about source size and interaction mechanisms [28]. At LHC energies, the ALICE Collaboration precisely measured the initial energy density, effective temperature, system size, lifetime, and interactions between various hadron pairs via femtoscopy, extracted the scattering parameters, and demonstrated the feasibility of detecting three-body correlations [5, 29, 30]. Notably, momentum correlations have confirmed charge-parity-time (CPT) symmetry in proton-proton and antiproton-antiproton interactions [31]. Recent advances have extended the femtoscopy studies to exotic systems, including strange hadrons (e.g., Ω and ∑ hyperons), charm hadrons (e.g. D mesons), light nuclei (e.g., deuterons, tritons), and test predictions from lattice QCD and chiral effective field theory [32-34]. Measurements have been performed for the correlations between Λ-Λ, p-Λ and p-Ω, particularly for the study of hyperon-hyperon and hyperon-nucleon interaction in dense matter [35-41]. Momentum correlation studies have also been conducted for proton-deuteron and deuteron-deuteron systems, with the scattering parameters measured, offering valuable insights into strong interactions in exotic nuclear systems [42, 43]. In addition to heavy-ion collisions, analyses have been extended to smaller collision systems with further constraints on the dynamics of particle production during high-energy collisions [44-46].

In this study, we explore the effects of nuclear structure on the momentum correlation of nucleons in isobar collisions by considering the different deformation configurations of Ru and Zr nuclei. In contrast to femtoscopy studies in non-deformed nuclear systems (e.g. Au+Au and Pb+Pb), the distinct deformation profiles of Ru (quadrupole) and Zr (octupole) nuclei in isobaric collisions introduce differences in the initial-state geometry. In addition, different nuclear deformation parameters correspond to different neutron skin thicknesses. Because two-particle correlations are sensitive to source size, comparing Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr systems can reveal how nuclear deformation affects particle emission dynamics and final-state momentum correlation, which may offer an appropriate way to explore the interplay between nuclear deformation and collective dynamics inside the QGP.

This paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, a multiphase transport model is described, and different cases of the Woods-Saxon parameters for Ru and Zr are introduced. In Sect. 3, the results of the momentum correlation functions of nucleon pairs for different isobaric deformation configurations are discussed. In Sect. 4, a brief summary will be given.

Model and Methodology

The AMPT model

A multiphase transport model [47, 48] has been applied extensively and successfully to study heavy-ion collisions at relativistic energies [49-54]. In the string melting version of the model, the initial state phase space information of partons considering fluctuating initial conditions is generated by the heavy ion jet interaction generator (HIJING) model, where minijet partons and excited strings are produced by hard and soft processes, respectively [55]. To study the collisions of deformed nuclei, we altered the nucleon distribution, which is discussed in more detail in Sect. 2.2. The interaction between partons is then simulated by Zhang’s parton cascade (ZPC) model which includes only two-body parton elastic scatterings [56]. During the hadronization process, a quark coalescence model was used to combine partons into hadrons. Then, the final-state hadronic evolution is described by a relativistic transport (ART) model that considers baryon-baryon, baryon-meson, and meson-meson elastic and inelastic scatterings, as well as resonance decay processes [57].

The nuclear deformation configuration

In AMPT, the default spatial distribution of nucleons in the nucleus rest frame is given by Woods-Saxon (WS) distribution, defined as follows [15, 58-60]:

The quadrupole deformation parameter β2 and the octupole deformation parameter β3 describe the deformation of the nucleus from a spherical shape. These parameters have been widely used in recent studies [15, 58, 62-65].

In this study, we investigated the influence of the nuclear structure on the nucleon momentum correlations in relativistic isobar collisions (Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr). Because the Woods-Saxon parameters for these two isobaric systems have not been determined, we explored four cases of parameter sets in our study, as shown in Table 1 [15, 62, 64, 66-68]. Case 1 is without deformation, and values of R0 and "a" for Ru and Zr are set to be the same, while in case 2, Ru (β2 = 0.13) has a bigger quadrupole deformation than Zr (β2 = 0.06). Case 3 is based on calculations using the energy density functional theory (DFT), which also assumes that the nuclei are spherical. The differences in R0 and "a" between Zr and Ru result in a thicker neutron skin for Zr. Case 4 also includes the deformation effect and neutron skin effect. In this study, the distribution of nucleons (protons and neutrons) inside the nuclei was initialized according to Eq. (1) based on the nuclear matter density configuration.

| Nucleus | Ru | Zr | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Para. | R0 (fm) | a (fm) | β2 | β3 | R0 (fm) | a (fm) | β2 | β3 |

| Case 1 | 5.096 | 0.540 | 0 | 0 | 5.096 | 0.540 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 2 | 5.13 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0 | 5.06 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0 |

| Case 3 | 5.067 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 4.965 | 0.556 | 0 | 0 |

| Case 4 | 5.09 | 0.46 | 0.162 | 0 | 5.02 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 0.20 |

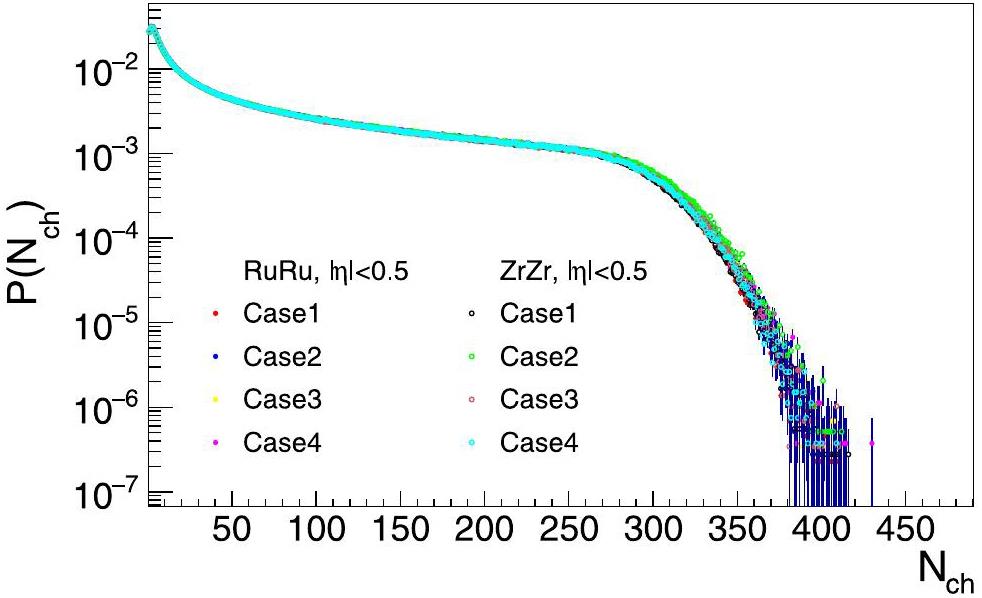

In the AMPT model, the shape of the initial geometry produced by collisions is primarily determined by the collision event impact parameter "b" and nuclear structure parameters. To facilitate an experimental comparison, we divided the centrality classes based on the number of final-state charged particles with pseudorapidity |η| < 0.5, instead of directly using the impact parameter. The charged-particle multiplicity distributions of the four cases of the Woods-Saxon parameterization for Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr collisions at

| Multiplicity cut (>) | ||||||||

| Ru + Ru | Zr + Zr | |||||||

| 7.7 GeV | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

| 0% – 20% | 61 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 61 | 62 | 61 | 61 |

| 20% – 40% | 31 | 33 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 32 | 32 |

| 40% – 60% | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 15 |

| 60% – 80% | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 200 GeV | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

| 0% – 20% | 150 | 154 | 153 | 154 | 150 | 155 | 151 | 151 |

| 20% – 40% | 69 | 73 | 71 | 73 | 69 | 73 | 69 | 70 |

| 40% – 60% | 28 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 27 | 28 |

| 60% – 80% | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

Correlation function

The Lednický-Lyuboshitz method [69-72] was used to calculate the momentum correlation function. Firstly, the s-wave scattering amplitude for proton-proton (p-p) pair is obtained by

The equal-time reduced Bethe-Salpeter amplitude for p-p pair is calculated approximately as

For the n-p pair, η is set to 0, and the Coulomb wave function

Results and Discussion

Based on the centrality definition and initial nuclear configuration described above, we studied the nucleon momentum correlation in the Ru and Zr collision systems.

The final-state phase space information can be obtained from the AMPT model for collisions with different deformed nuclei. We derived the correlation functions of p-p and n-p for four cases of nuclear deformation in different centrality classes in isobaric collisions at

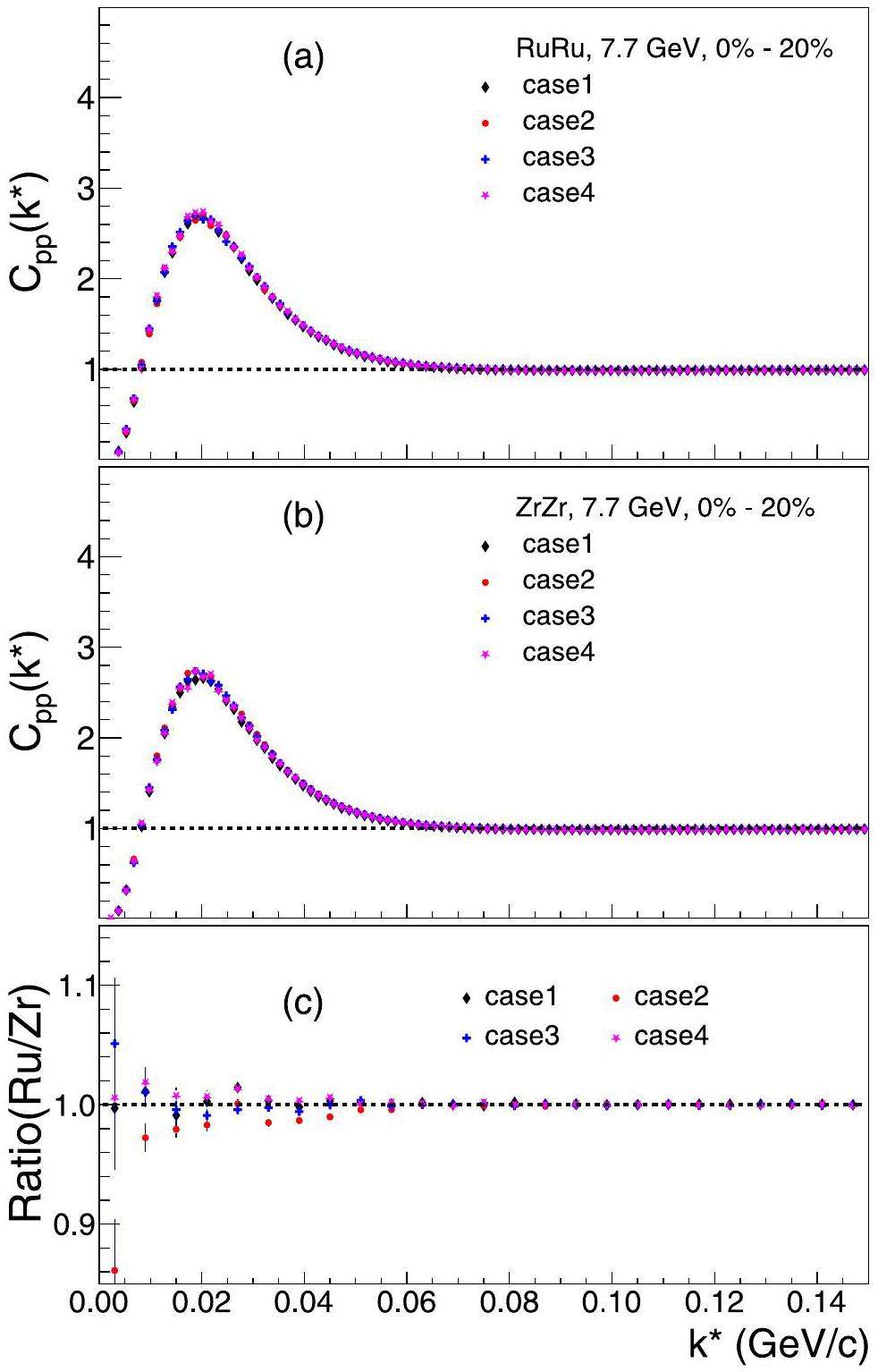

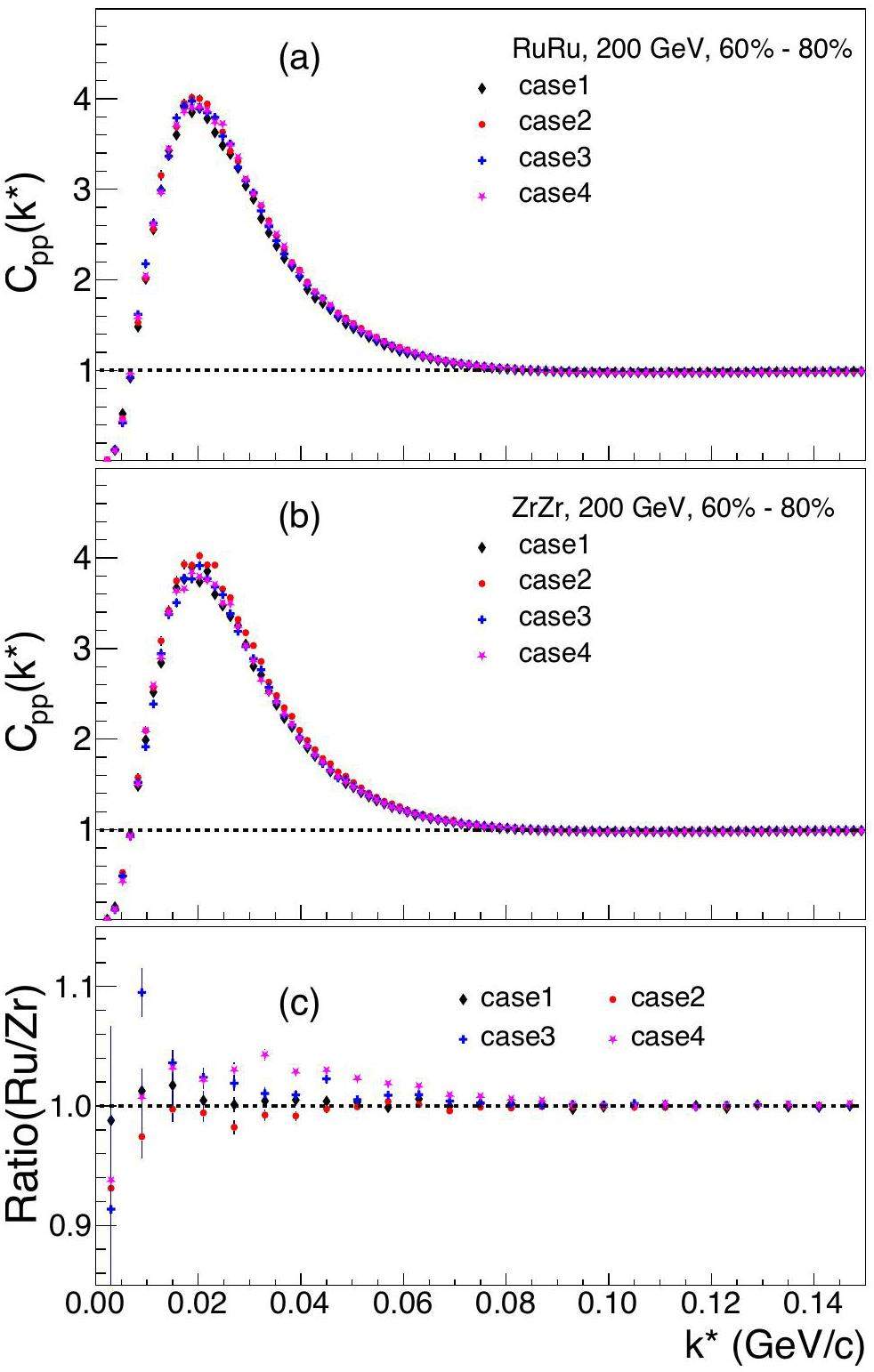

Figure 2 shows the AMPT results of the p-p correlation functions for Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr collisions at

In panel (c) of Fig. 2, the ratios of the correlation functions are calculated for each deformation parameterization case, allowing for a quantitative study of the initial-state effects on the two collision systems. It can be seen that in Case 1, the parameters of both systems are identical. Despite the difference in the number of nuclear charges between the two systems, little difference is observed between the correlation functions. Case 3 does not involve a nuclear shape change but incorporates the neutron skin effect. Our results demonstrate that the neutron skin effect caused by different density distributions of protons and neutrons might have a negligible influence on the correlation function in central collisions, consistent with the understanding that neutron skin effects are largely suppressed in central collisions, as they predominantly manifest in peripheral collisions [76].

In Case 2, the ratio of the correlation functions between the two systems for 0–20% centrality is less than 1 with a 1–2% offset in the low k* region. As β3 is 0 for both Ru and Zr, the relative magnitude of the correlation function is determined by the radius parameter R0 and quadrupole deformation parameter β2. In contrast, the ratio results of Case 4 are slightly larger than 1, with a relative difference of ∼ 1%, indicating that β3 may have a potential influence on the correlation results. The ratios of these four cases are generally consistent with 1 at large k* (>0.05 GeV/c), indicating that the effects of nuclear deformation are negligible in this region.

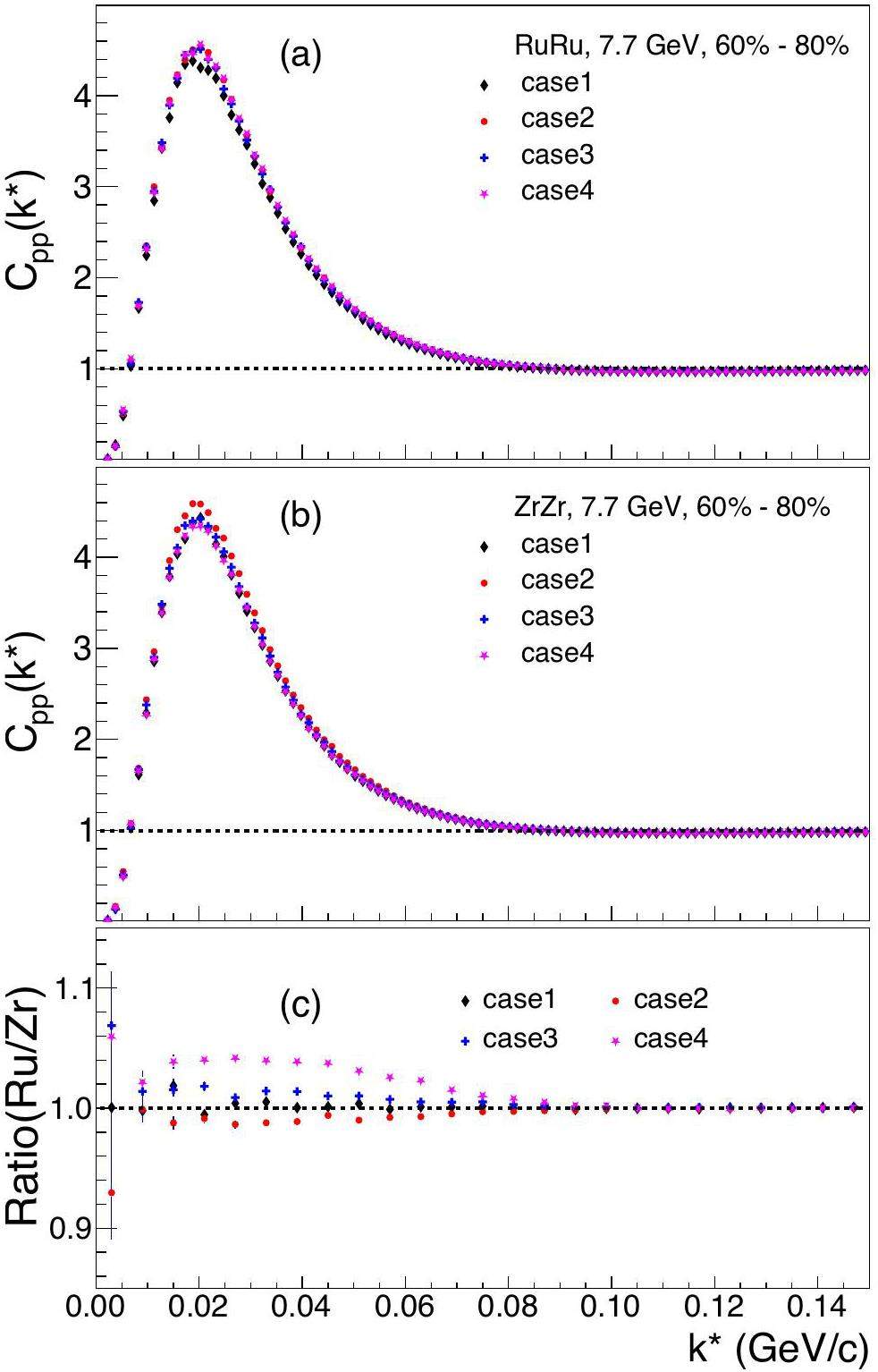

Figure 3 shows the results of the correlation functions for four different cases of deformation configuration in Ru + Ru (Panel a) and Zr + Zr (Panel b) collisions at

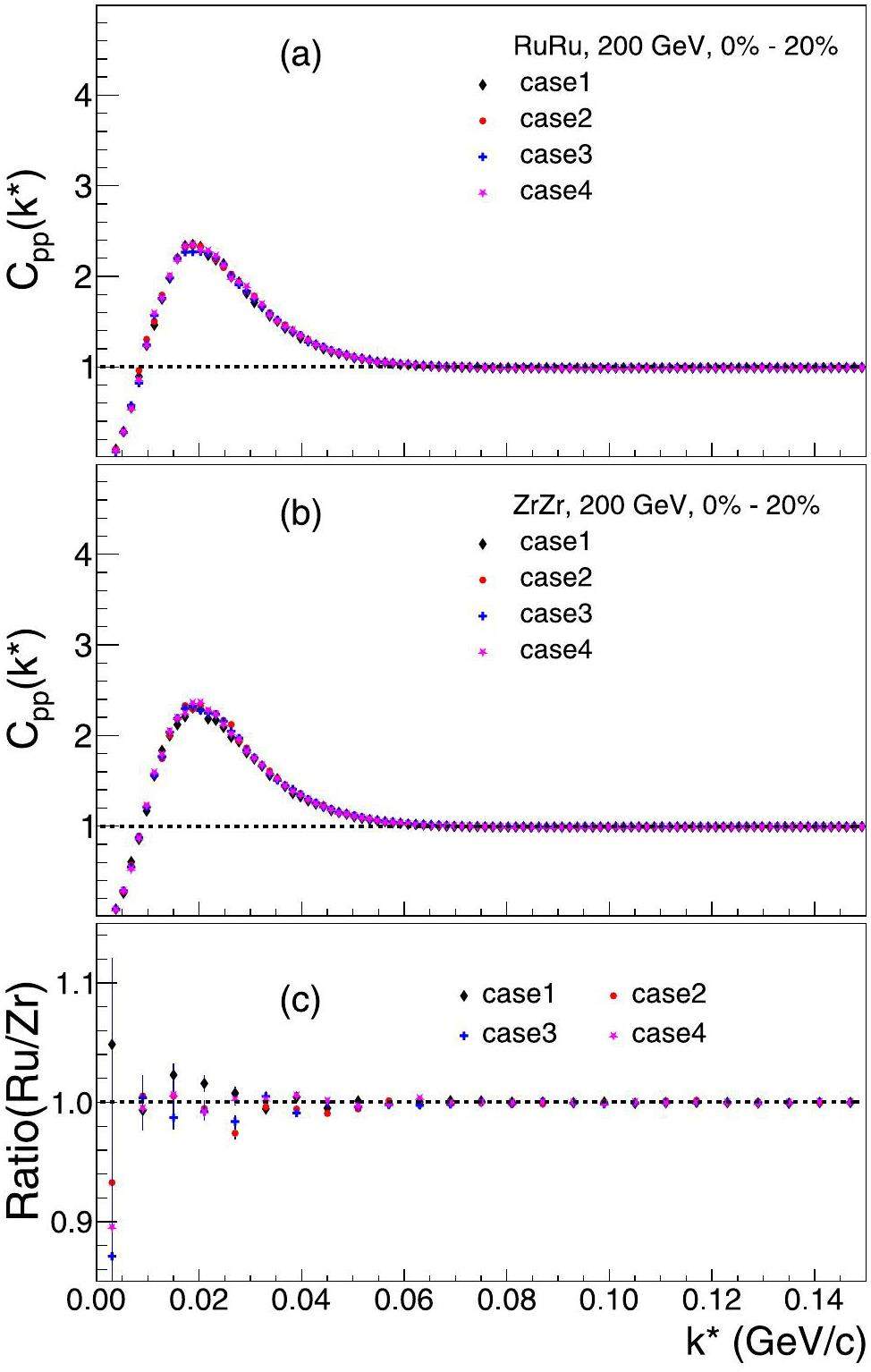

Figures 4 and 5 show the results of central and peripheral collisions at

In peripheral collisions, the ratio (Ru/Zr) in Case 1 is consistent with unity. The ratios for Case 2 show deviations from unity with magnitudes similar to those at

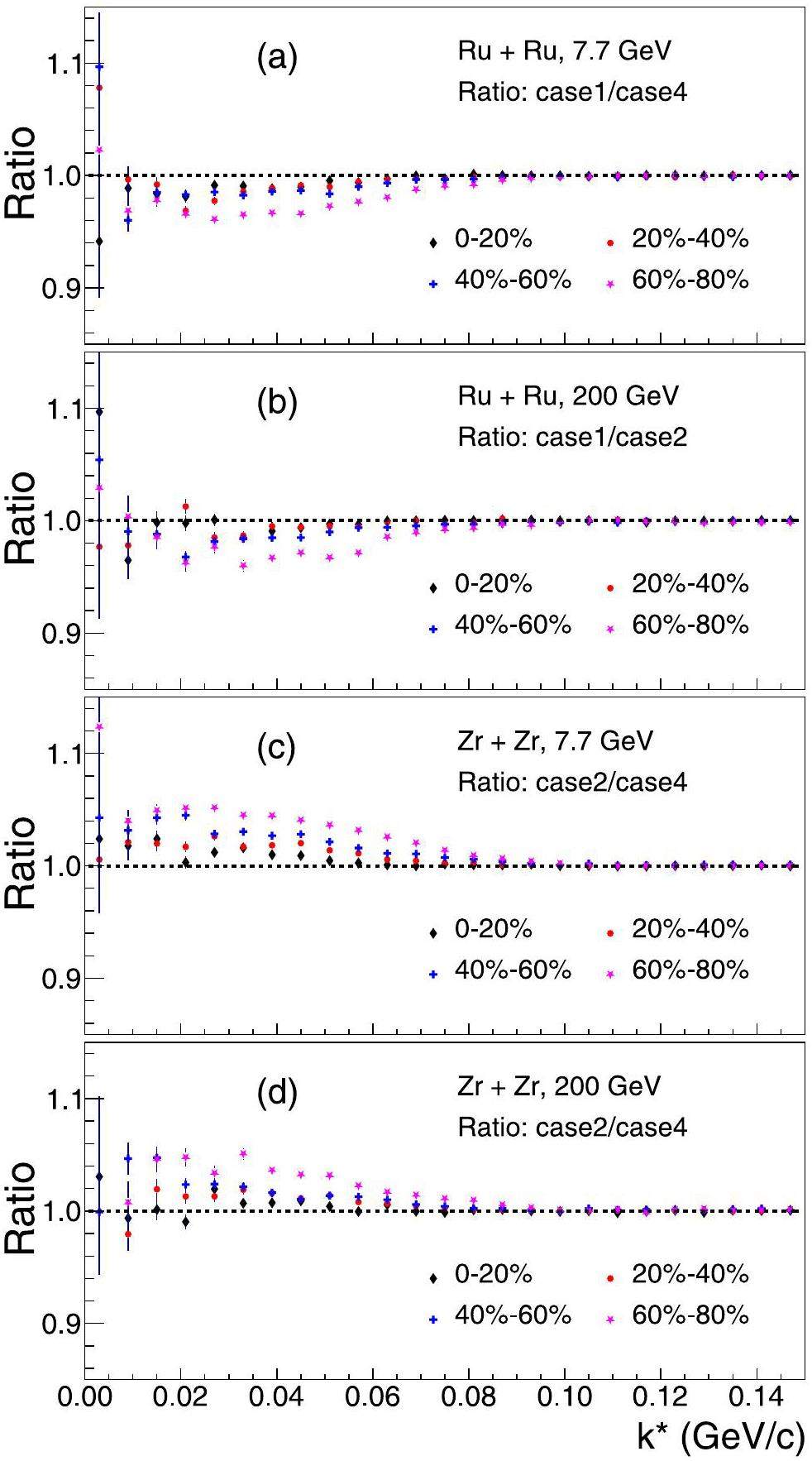

We calculated the ratios of the correlation functions between different parameterization cases across the centrality classes from 0–20% to 60–80%. Figure 6 shows the results for Zr + Zr and Ru + Ru collisions at

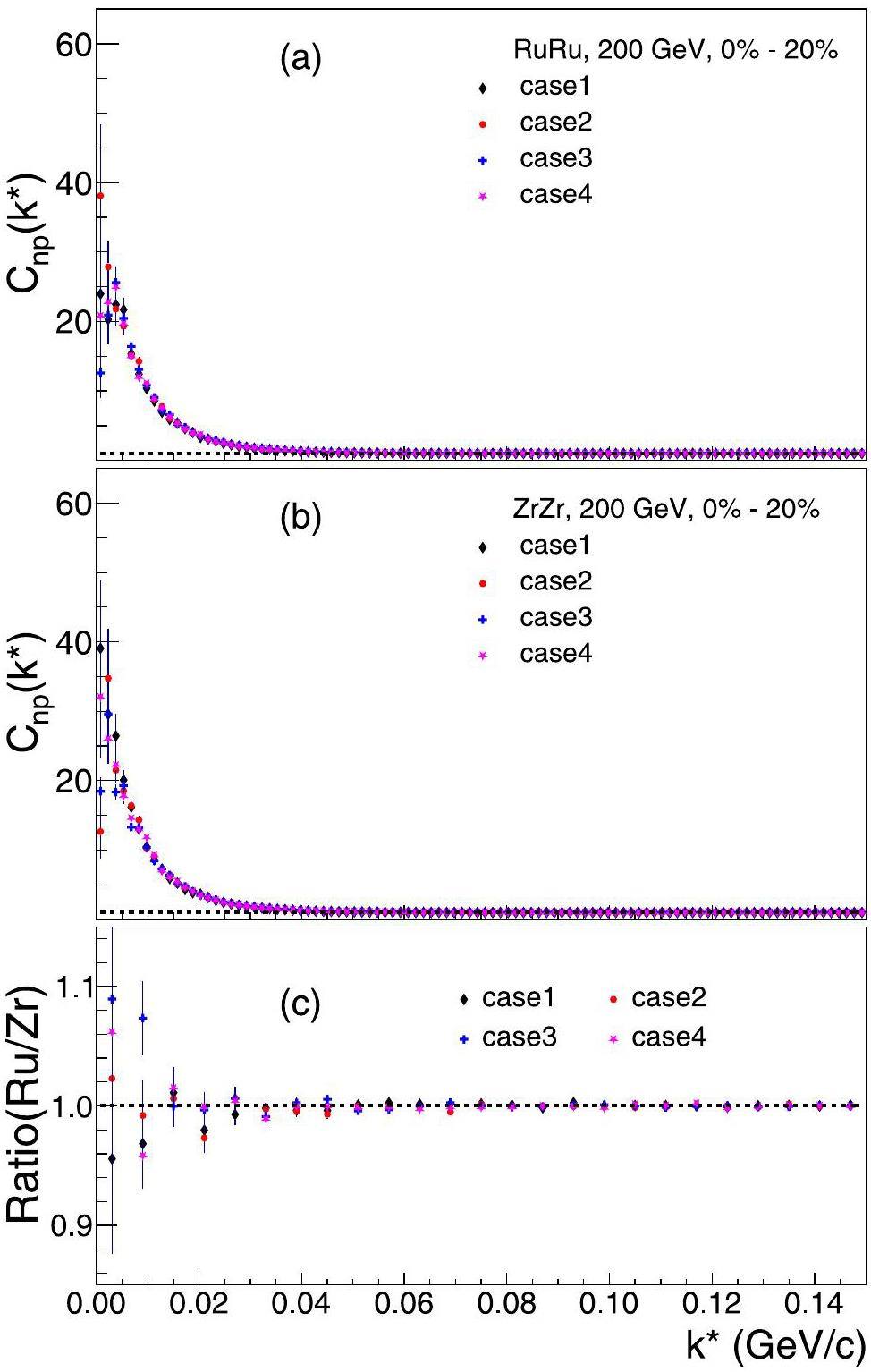

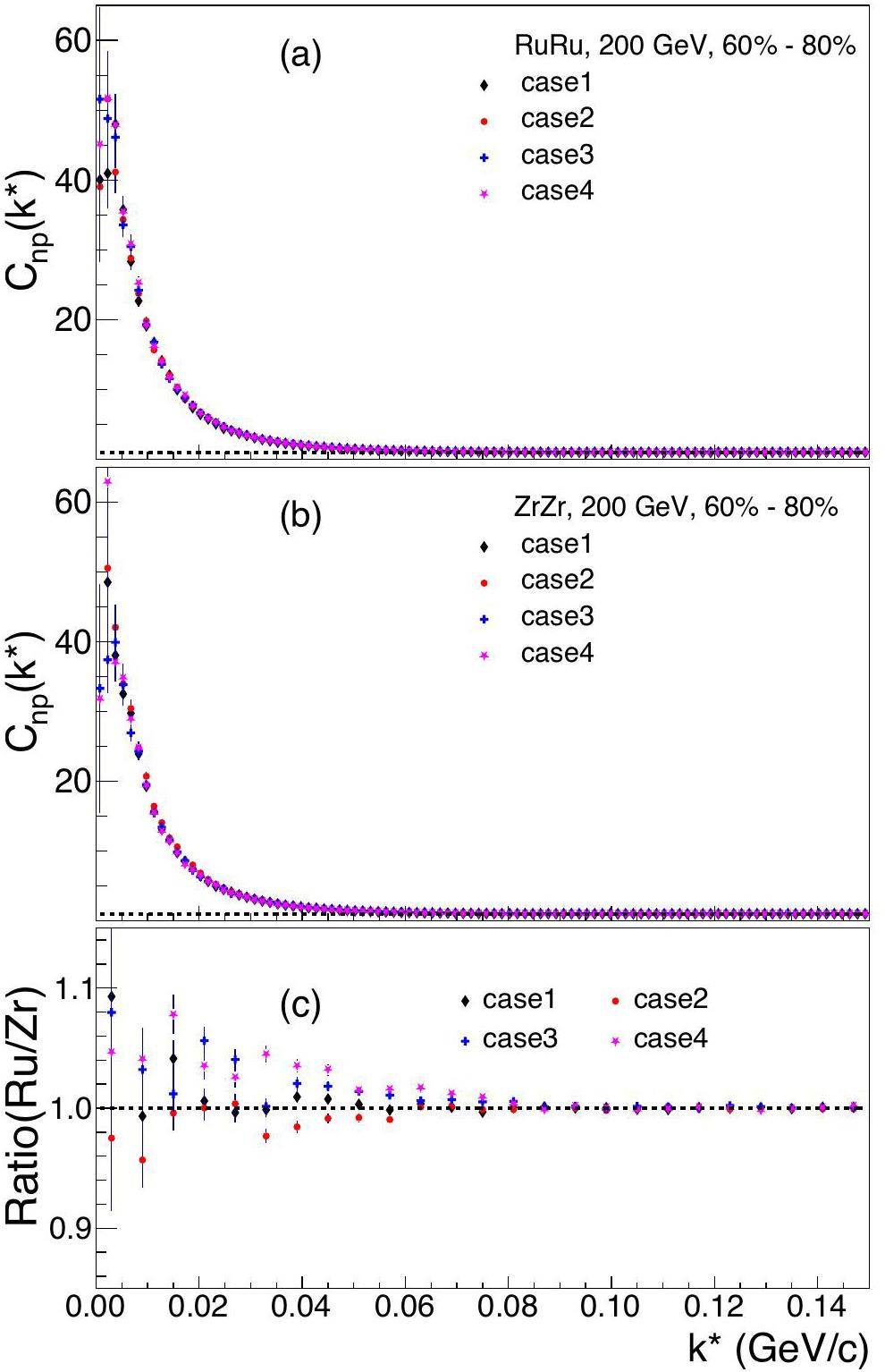

Studies have also been performed for n-p correlation. Figures 7 and 8 show the results of central and peripheral Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr collisions at

The ratios of the correlation functions between the two systems (Ru/Zr) for the different cases are shown in the bottom panels of Figs. 7 and 8. It was found that the ratio results at

Summary

Using the AMPT model, we investigated the nucleon momentum correlation in the relativistic collisions of Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr at

The ratios of the correlation functions between the two isobaric systems (Ru/Zr) for four different cases of Woods-Saxon parametrization were evaluated based on the simulation data with a clear centrality dependence. The ratio shows no deviation from unity in case 1 for nuclei with the same nuclear size and without deformation. We observed a deviation from unity in the ratios for cases 2-4 in both central and peripheral collisions, which could be attributed to the deformation effect. We found that the influence of the nuclear structure becomes more significant in peripheral collisions. A maximum deviation of 5% from unity was observed between all the Woods-Saxon parameterization cases and 4% between collision systems in 60–80% peripheral collisions, incorporating nuclear size and the neutron skin effect. Meanwhile, it was found that the energy dependence of both the neutron skin effect and deformation effect in the p-p correlation is shallow. In addition, we found that in both p-p and n-p, the intensity of the correlation function in central collisions is greater than that in peripheral collisions. The results of the p-p correlation at

Notably, our simulation study did not consider the evolution and interactions of magnetic fields related to the charge number of the colliding nuclei. Further theoretical studies incorporating magnetic field effects in nucleon momentum correlation, along with experimental measurements at RHIC energies, would enable more precise examinations of nuclear structure and size, providing stronger constraints on the nuclear structure parameters of the isobar systems [77].

Strongly coupled quark-gluon plasma in heavy ion collisions

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89,Experimental and theoretical challenges in the search for the quark-gluon plasma: The STAR Collaboration’s critical assessment of the evidence from RHIC collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 757, 102-183 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.03.085Formation of dense partonic matter in relativistic nucleus-nucleus collisions at RHIC: Experimental evaluation by the PHENIX collaboration

. Nucl. Phys. A 757, 184-283 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.03.086Probing charm quark dynamics via multiparticle correlations in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129,Properties of QCD matter: a review of selected results from ALICE experiment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01583-2Anisotropic flow of charged particles in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116,Probing longitudinal structures of quark gluon plasma in extreme states of nuclear matter

. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astro. 55, 1 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1360/SSPMA-2024-0571Search for the chiral magnetic effect with isobar collisions at sNN=200 GeV by the STAR Collaboration at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Status of the chiral magnetic effect and collisions of isobars

. Chin. Phys. C 41,Predictions for isobaric collisions at sNN=200 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Properties of the QCD matter: review of selected results from the relativistic heavy ion collider beam energy scan (RHIC BES) program

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01591-2Charge separation measurements in Au+Au collisions at sNN=7.7−200 gev in search of the chiral magnetic effect

. arXiv:2506.00275Search for the chiral magnetic effect through beam energy dependence of charge separation using event shape selection

. arXiv:2506.00278Probing nuclear structure with mean transverse momentum in relativistic isobar collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Impact of nuclear structure on the background in the chiral magnetic effect in 4496Ru + 4496Ru and 4096Zr + 4096Zr collisions at sNN=7.7 ~ 200 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Multiparticle azimuthal correlations in isobaric 96Ru+96Ru and 96Zr+96Zr collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. arXiv:2409.15040Precision tests of the nonlinear mode coupling of anisotropic flow via high-energy collisions of isobars

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40,Evidence of quadrupole and octupole deformations in Zr96+Zr96 and Ru96+Ru96 collisions at ultrarelativistic energies

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Vorticity in isobar collisions of 4496Ru + 4496Ru and 4096Zr + 4096Zr at sNN=200 GeV

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 33 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-00932-wAnisotropy fluctuation and correlation in central α-clustered 12C+197Au collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Imaging shapes of atomic nuclei in high-energy nuclear collisions

. Nature 635, 67-72 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08097-2Correlation between photons in two coherent beams of light

. Nature 177, 27-29 (1956). https://doi.org/10.1038/177027a0Pion interferometry of nuclear collisions. 1. theory

. Phys. Rev. C 20, 2267-2292 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.20.2267Intensity interferometry in subatomic physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 553-602 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.62.553Correlation femtoscopy of multiparticle processes

. Phys. Atom. Nucl. 67, 72-82 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1134/1.1644010Searching for 4Li¯ via the momentum-correlation function of p¯−3He¯

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Review of HBT or Bose-Einstein correlations in high energy heavy ion collisions

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 50, 259-270 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/50/1/031Calculation of momentum correlation functions between π, K, and p for several heavy-ion collision systems at sNN=39 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Pion-kaon femtoscopy in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV measured with ALICE

. Nucl. Phys. A 982, 351-354 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2018.10.048Scattering studies with low-energy kaon-proton femtoscopy in proton-proton collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Measurement of interaction between antiprotons

. Nature 527, 345-348 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15724λλ interaction from relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Femtoscopy of d mesons and light mesons upon unitarized effective field theories

. Phys. Rev. D 108,Probing multistrange dibaryons with proton-omega correlations in high-energy heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Unveiling the strong interaction among hadrons at the LHC

. Nature 588, 232-238 (2020). [Erratum: Nature 590, E13 (2021)]. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3001-6Proton - lambda correlations in central Au+Au collisions at sNN=200-GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Study of baryon number transport dynamics and strangeness conservation effects using ω-hadron correlations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01464-8λλ correlation function in Au+Au collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114,First Observation of an Attractive Interaction between a Proton and a Cascade Baryon

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Antinuclei in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rept. 760, 1-39 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2018.07.002The proton-ω correlation function in Au+Au collisions at sNN=200 GeV

. Phys. Lett. B 790, 490-497 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.01.055Light nuclei femtoscopy and baryon interactions in 3 GeV Au+Au collisions at RHIC

. Phys. Lett. B 864,Simulations of momentum correlation functions of light (anti)nuclei in relativistic heavy-ion collisions at sNN=39 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 107,p-p, p-λ andλ-λcorrelations studied via femtoscopy in pp reactions at s=7 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Pion femtoscopy in p+p collisions at s=200 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Search for a common baryon source in high-multiplicity pp collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Lett. B 811,A Multi-phase transport model for relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Further developments of a multi-phase transport model for relativistic nuclear collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00944-5Anisotropy flows in Pb–Pb collisions at LHC energies from parton scatterings with heavy quark trigger

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-00999-yInitial partonic eccentricity fluctuations in a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Impact of globally spin-aligned vector mesons on the search for the chiral magnetic effect in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 839,The effect of hadronic scatterings on the measurement of vector meson spin alignments in heavy-ion collisions

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Energy dependence of transverse momentum fluctuations in Au+Au collisions from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 111,Ab-initio nucleon-nucleon correlations and their impact on high energy 16O+16O collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 862,HIJING: A monte carlo model for multiple jet production in pp, pA and AA collisions

. Phys. Rev. D 44, 3501-3516 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.44.3501ZPC 1.0.1: A parton cascade for ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 109, 193-206 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(98)00010-1Formation of superdense hadronic matter in high-energy heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 2037-2063 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.2037Test the chiral magnetic effect with isobaric collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Impact of nuclear deformation on relativistic heavy-ion collisions: Assessing consistency in nuclear physics across energy scales

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Parameterization of deformed nuclei for glauber modeling in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 749, 215-220 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2015.07.078Ratios of collective flow observables in high-energy isobar collisions are insensitive to final-state interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Scaling approach to nuclear structure in high-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Tables of internal conversion coefficients for superheavy elements

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tabl. 78, 129-160 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.2001.0859Production of light nuclei in isobaric Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr collisions at sNN=7.7−200 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Probing the octupole deformation of 238U in high-energy nuclear collisions

. arXiv:2504.15245Importance of isobar density distributions on the chiral magnetic effect search

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Determine the neutron skin type by relativistic isobaric collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 819,Effect of nuclear structure on particle production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions using a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Final state interaction effect on pairing correlations between particles with small relative momenta

. Yad. Fiz. 35, 1316-1330 (1981).Finite-size effects on two-particle production in continuous and discrete spectrum

. Phys. Part. Nucl. 40, 307-352 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063779609030034Multiboson effects in multiparticle production

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Notes on correlation femtoscopy

. Phys. Atom. Nucl. 71, 1572-1578 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778808090123Femtoscopy in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 55, 357-402 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.55.090704.151533Tomography of ultrarelativistic nuclei with polarized photon-gluon collisions

. Sci. Adv. 9,A review of intense electromagnetic fields in heavy-ion collisions: Theoretical predictions and experimental results

. Research 8, 0726 (2025). https://doi.org/10.34133/research.0726Yu-Gang Ma is the editor-in-chief for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.