Introduction

The cluster structure in an atomic nucleus is a spatially located subsystem consisting of strongly related nucleons with much greater internal binding energy than external nucleons, which can be treated as a whole without considering its internal structure [1]. In 1968, Ikeda proposed that nuclear cluster states tend to occur in excited states near cluster threshold energy [2]. In some weakly bound nuclei, the cluster structure is more obvious, and the cluster structure is also ubiquitous in light nuclei; for example, the configuration of 6Li is composed of a α particle and a deuteron, the 2α structure for 8Be, 3α for 12C, and 5 α for 20Ne [3, 4]. The most convenient method to study the cluster structure inside a nucleus is to separate the cluster via pick-up or stripping reactions. A theoretical explanation of the pre-equilibrium reaction was initially developed using the exciton model. Semi-classical theories have been less successful in explaining the angular distribution of emitted particles. The Boltzmann master equation theory was mainly used to calculate the energy spectra of particles emitted during nucleon-induced reactions and heavy-ion reactions. Details can be found in the review paper [5]. However, the emission of preequilibrium clusters in transfer reactions around the Coulomb barrier is also an important physical problem. The emission of preequilibrium clusters is a complex process that is related not only to the cluster structure of the collision system but also to the dynamics of the reaction. In the treatment of nuclear structures, the cluster state is the overlap of the single-particle wave functions. In the nuclear reaction, the formation of a preequilibrium particle is different from the cluster emitted during the de-excitation of a composite nucleus, and a pre-equilibrium cluster is formed before the formation of the compound nucleus. Its emission continues until the formation of the composite nucleus, and the pre-equilibrium cluster may be emitted from any fragment during the reaction. Cluster emission provides important information for the study of single-particle states or multiparticle correlation of nuclei and is a powerful tool for nuclear spectroscopy [5]. Moreover, cluster emission in intermediate- and high-energy heavy-ion collisions is also important for investigating nuclear fragmentation and little-bang nucleosynthesis [6-8].

Since multinucleon transfer (MNT) reactions and deep inelastic heavy-ion collisions were proposed in the 1970s [9-11], a large number of experiments have been carried out to measure the double differential cross-sections, angular distributions, and energy distributions of different reaction systems. However, it is worth noting that there has been relatively little experimental and theoretical research on pre-equilibrium cluster emissions in transfer reactions. In the 1980s, scientists at RIKEN in Japan and IMP in China measured the pre-equilibrium cluster emission of the transfer reactions of 14N+159Tb, 169Tm, 181Ta, 197Au, 209Bi [12] and 12C+209Bi [13, 14], respectively. The angular distributions, kinetic energy spectra, and total production cross-sections of the emitted particles were measured experimentally. As we all know, since the concept of superheavy stable island was proposed in the 1960s, the synthesis of superheavy nuclei has become an important frontier in the field of nuclear physics. In the past few decades, 15 types of superheavy elements Z=104~118 [15] have been artificially synthesized by hot fusion or cold fusion reactions. However, owing to the limitations of projectile-target materials and experimental conditions, it is difficult for the fusion evaporation reaction to reach the next period of the periodic table. With MNT reactions, many nuclei can be generated depending on the transfer channels, and with the development of separation and detection technology, the MNT reaction may be the most promising method for synthesizing unknown superheavy elements. This mechanism has been applied to the production of heavy and super-heavy isotopes [16, 17].

The study of pre-equilibrium cluster emission in the MNT reaction is not only of great significance for understanding the cluster structure of the collision system but also for exploring the formation mechanism of the cluster, the kinetic information of the reaction process, and the nuclear astrophysical process. The High Intensity Accelerator Facility (HIAF) built in Huizhou, China has a large energy range and a wide range of particle beams [18], which provides a good experimental platform for the study of nuclear cluster structures and cluster emission.

In this study, we systematically investigated the preequilibrium cluster emission in transfer reactions. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide a brief description of the DNS model for describing preequilibrium cluster production. In Sect. 3, the production cross sections, kinetic energy spectra, and angular distributions of the preequilibrium clusters are analyzed and discussed. A summary and perspective are presented in Sect. 4.

Brief description of the model

The dinuclear system (DNS) model was first proposed by Volkov [19] to describe deep inelastic heavy-ion collisions. For the first time, Adamian et al. applied the DNS model to fusion evaporation reactions in competition with the quasi-fission process to study the synthesis of superheavy nuclei [20-22]. The Lanzhou nuclear physics group has further developed the DNS model [23-26]; for example, they introduced the barrier distribution function method in the capture process, considered the effects of quasi-fission and fission in the fusion stage, used statistical evaporation theory, and the Bohr-Wheeler formula to calculate the survival probability of superheavy nuclei. The DNS model has been widely used to study the production cross-section, quasi-fission, fusion dynamics, etc., in the synthesis of superheavy nuclei based on fusion evaporation (FE) reactions and multinucleon transfer (MNT) reactions [27-30].

Using the DNS model, we calculated the temporal evolution, kinetic energy spectra, and angular distributions of the pre-equilibrium clusters in the transfer reactions with incident energy near the Coulomb barrier. Compared to our previous work [31], we introduced the transfer of clusters in the master equation of the DNS model, and the Coulomb force was considered in the pre-equilibrium cluster emission process. A pre-equilibrium particle is formed before the formation of the compound nucleus, and its emission continues until the composite nucleus is formed. The cross section of pre-equilibrium particle emission (ν= n, p, d, t, 3He, α, 6,7Li and 8,9Be) is defined as

The capture cross section of binary system overcoming the Coulomb barrier

In the capture stage, the collision system overcomes the Coulomb barrier, forming a composite system. The capture cross section is given by

For the heavy systems, the collision system does not form a potential energy pocket after overcoming the Coulomb barrier, T(Ec.m.,J) is calculated by the classic trajectory method,

The barrier distribution function is Gaussian form [25, 33]

The nucleon and cluster transfer dynamics

In the nucleon transfer process, the distribution probability of DNS fragments is obtained by numerically solving a set of master equations [34]. Fragment (Z1,N1) has the proton number of Z1, the neutron number of N1, the internal excitation energy of E1, and the quadrupole deformation β1, and the time evolution equation of its distribution probability can be described as

Similar to the cascade transfer of nucleons [25], the transfer of clusters is also described by the single-particle Hamiltonian,

In the relaxation process of relative motion, the DNS is excited by the dissipation of the relative kinetic energy and angular momentum. The excited DNS opens a valence space in which valence nucleons have a symmetrical distribution around the Fermi surface. Only the particles in states within the valence space are actively excited and undergo transfer. The average of these quantities was calculated in the valence space as follows:

The memory time is connected with the internal excitation energy [38],

In the relaxation process of relative motion, the DNS is excited by the dissipation of the relative kinetic energy. The local excitation energy is determined by the dissipation energy from the relative motion and the potential energy surface of the DNS [26, 28],

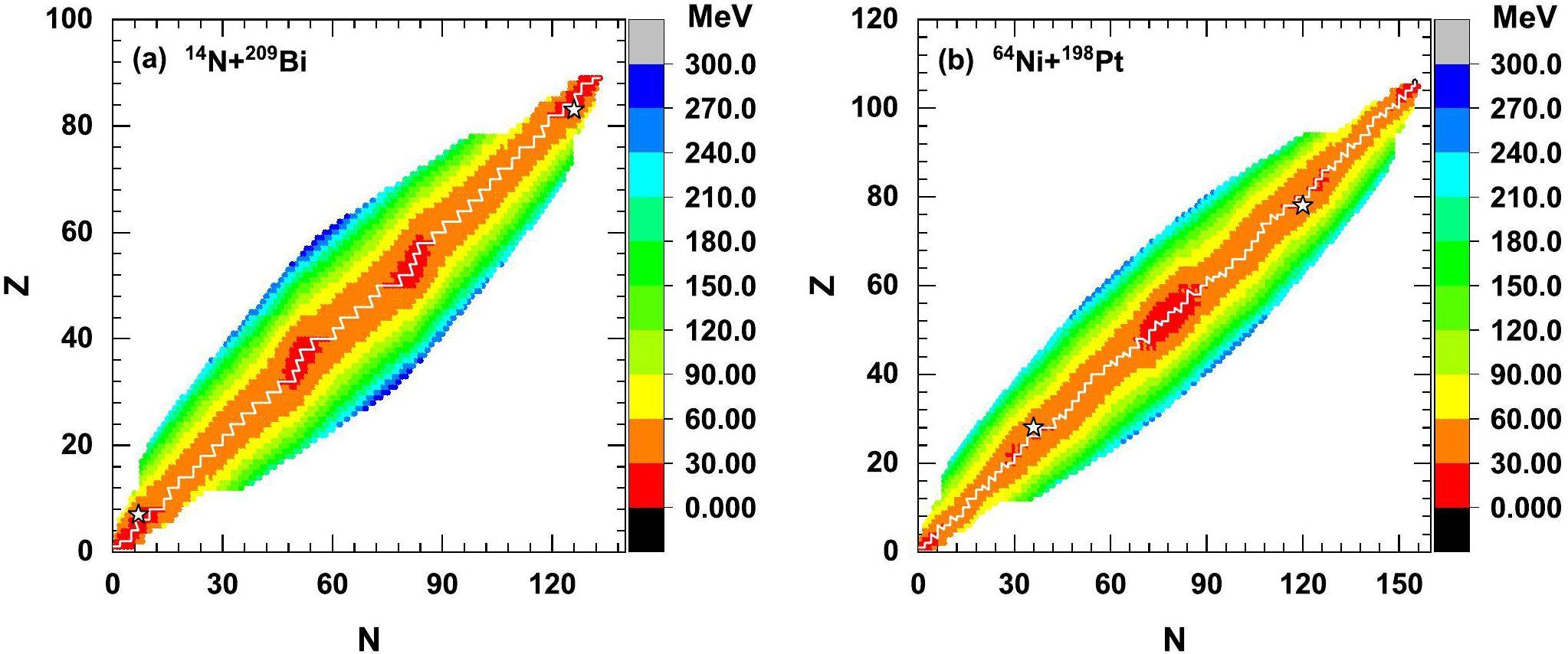

The potential energy surface (PES) of the DNS is evaluated as

The preequilibrium cluster emission

The emission probabilities of pre-equilibrium clusters with the kinetic energy Ek are calculated by the uncertainty principle within the time step

Based on the Weisskopf evaporation theory [46, 47], we have the particle decay widths as follows,

The inverse cross section is given by

The level density is calculated from the Fermi-gas model as

The kinetic energy of the pre-equilibrium particle is sampled using the Monte Carlo method within the energy range

We use the deflection function method [39, 50] to calculate the angular distribution of the pre-equilibrium particles emitted from the DNS fragments as

Results and discussion

The pre-equilibrium cluster emission in the transfer reaction is very complicated and is not only related to the structure of the collision system, for example, the pre-formation factor, but also to the dynamic evolution of the reaction process, that is, the dissipation of relative motion and the coupling of internal degrees of freedom of the reaction system. The emission of pre-equilibriumrium cluster is a non-equilibrium process of time and space evolution, which is a powerful probe for deeply investigating the MNT reaction dynamics.

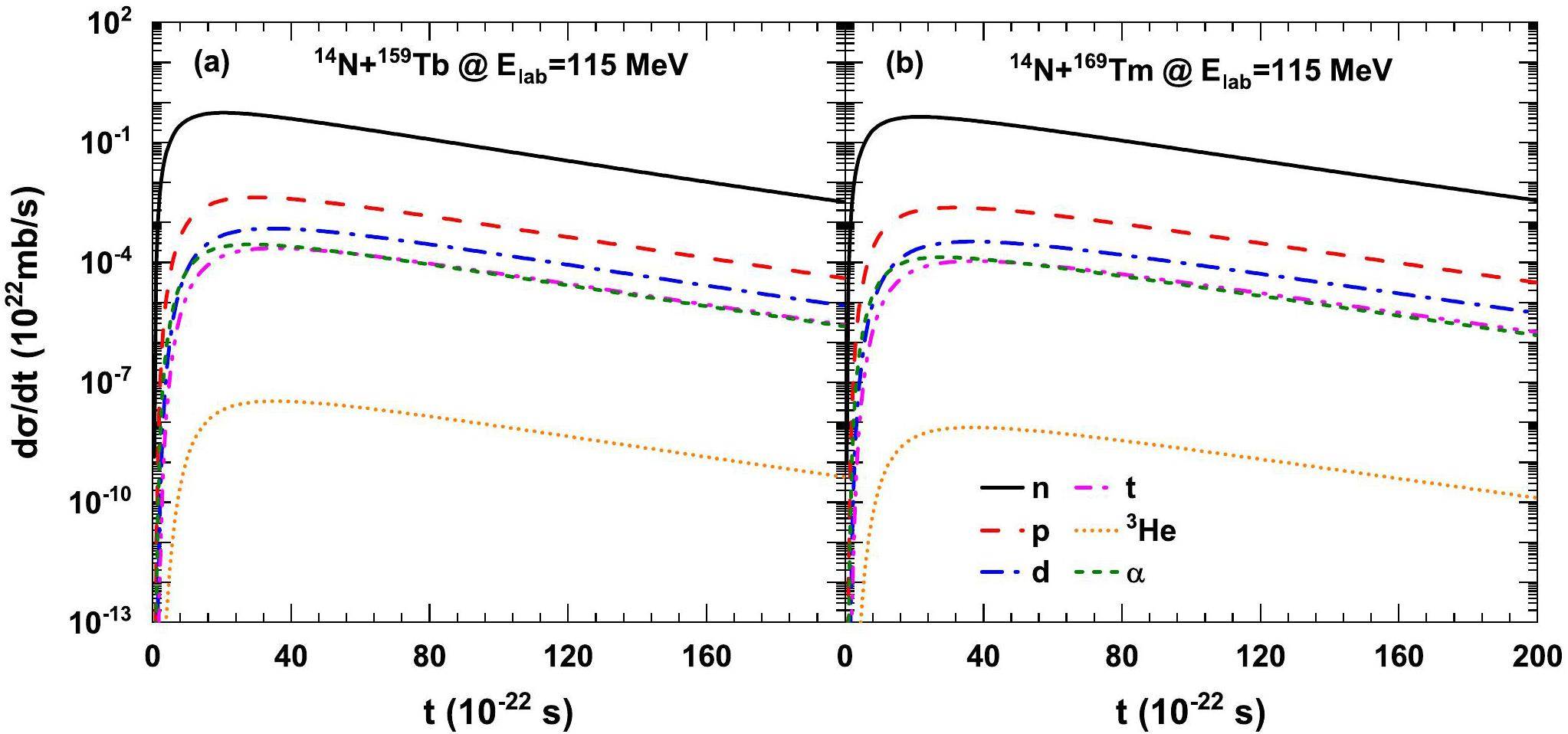

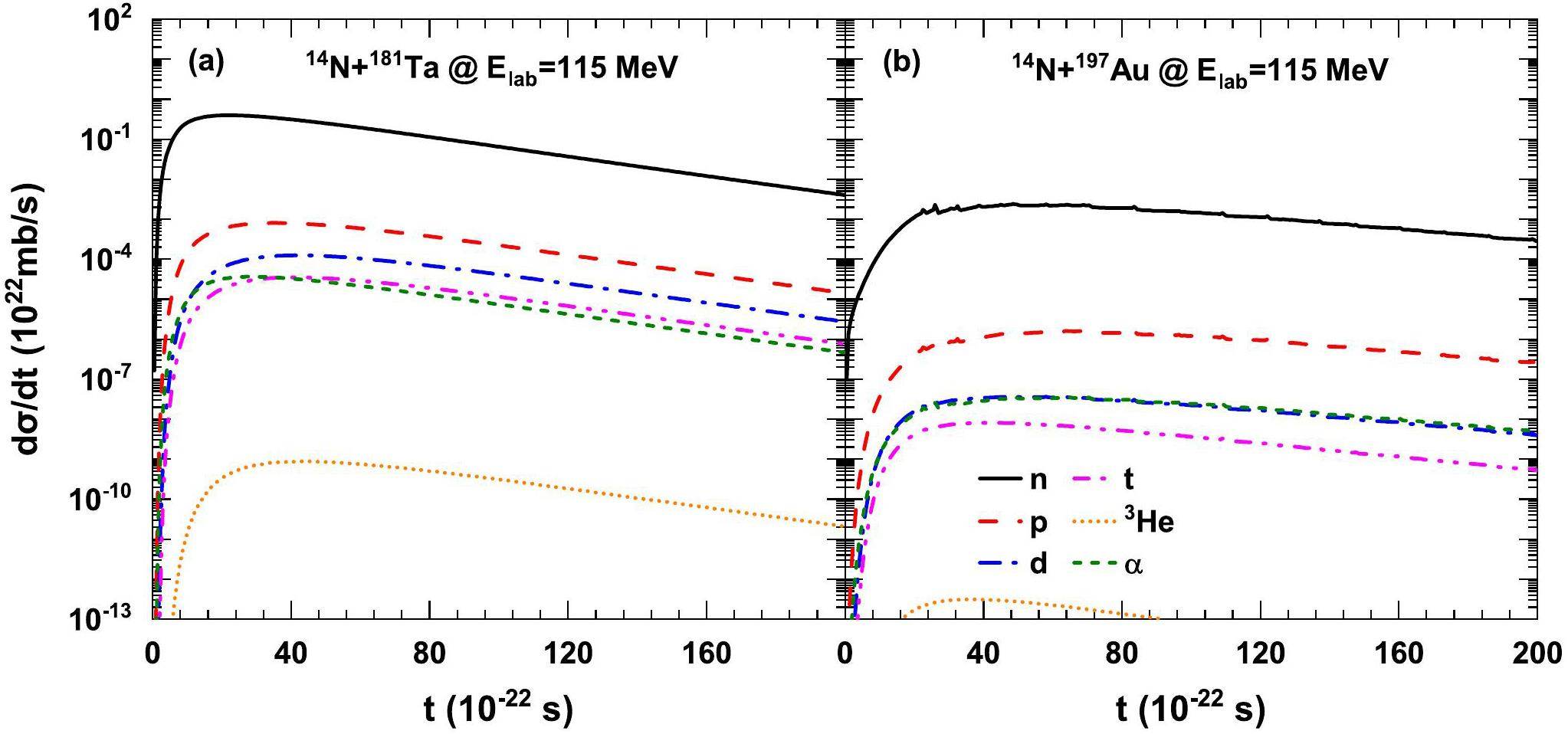

The temporal evolution of the emission probability of n, p, d, t, 3He and α from the transfer reactions of 14N + 159Tb, 169Tm, 181Ta and 197Au at Elab=115 MeV is shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, respectively. The formation of the compound nucleus is of the order of a few hundred zeptoseconds, while the reaction time of the preequilibrium process is approximately several zeptoseconds. It can be seen from the figures that the emission of the pre-equilibrium cluster continues until the formation of the composite nucleus. At the beginning of the reaction, the emission probability of the preequilibrium cluster increased rapidly, reaching a maximum value at approximately 20×10-22~40×10-22 s, and then remained stable or decreased gradually. The emission probabilities of α and hydrogen isotopes are comparable, and the yields are approximately 3~4 orders of magnitude lower than that of neutrons but much larger than that of 3He. The local excitation energy of the DNS fragment increases with time, and the emitted clusters can remove part of the energy, which is conducive to the formation of a compound nucleus with a lower excitation energy. The total emission cross sections of the preequilibrium clusters can be obtained by counting the temporal evolution of the cluster yields. The total emission cross sections of the different preequilibrium particles are shown in Table 1. It is obvious that the α yields are comparable with the proton emission

| Reaction system | Elab (MeV) | σn (mb) | σp (mb) | σd (mb) | σt (mb) | σα (mb) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12C+209Bi | 73 | 2.90×10-1 | 2.58×10-6 | 3.83×10-9 | 4.06×10-8 | 7.58×10-20 | 4.54×10-6 |

| 14N+159Tb | 115 | 1.45×10-1 | 1.29×10-6 | 1.92×10-9 | 2.03×10-8 | 3.79×10-20 | 2.27×10-6 |

| 14N+169Tm | 115 | 7.24×10-2 | 6.46×10-7 | 9.58×10-10 | 1.02×10-8 | 1.89×10-20 | 1.13×10-6 |

| 14N+181Ta | 115 | 3.62×10-2 | 3.23×10-7 | 4.79×10-10 | 5.08×10-9 | 9.74×10-21 | 5.67×10-7 |

| 14N+197Au | 115 | 1.81×10-2 | 1.62×10-7 | 2.40×10-10 | 2.54×10-9 | 4.74×10-21 | 2.83×10-7 |

| 14N+209Bi | 115 | 9.05×10-3 | 8.08×10-8 | 1.20×10-10 | 1.27×10-9 | 2.37×10-9 | 1.42×10-7 |

| 58Ni+198Pt | 170.2 | 1.11×10-4 | 7.65×10-5 | 7.16×10-8 | 1.23×10-9 | 4.30×10-10 | 2.96×10-9 |

| 58Ni+198Pt | 185.6 | 2.78×10-5 | 1.94×10-5 | 1.79×10-8 | 3.08×10-10 | 1.07×10-10 | 7.39×10-10 |

| 64Ni+198Pt | 181.4 | 6.94×10-6 | 4.85×10-6 | 4.47×10-9 | 7.70×10-11 | 2.69×10-11 | 1.85×10-10 |

| 72Ni+198Pt | 176.0 | 1.74×10-6 | 1.21×10-6 | 1.12×10-9 | 1.92×10-11 | 6.72×10-12 | 4.62×10-11 |

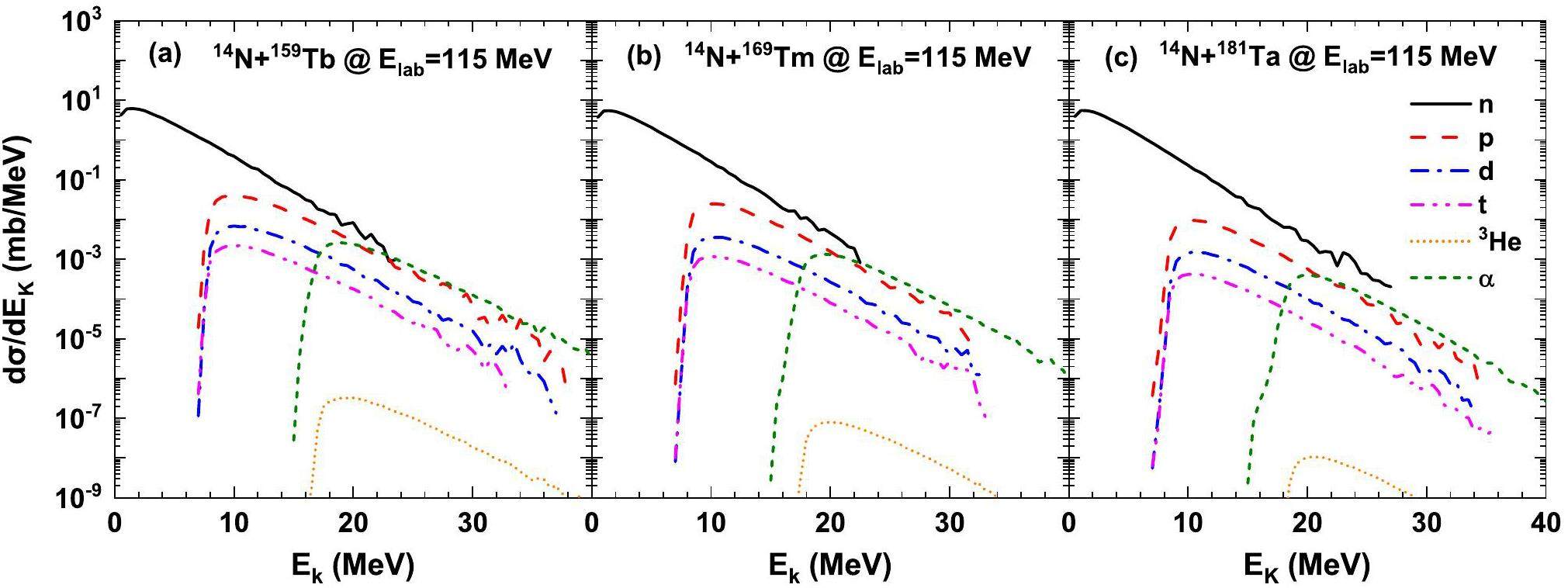

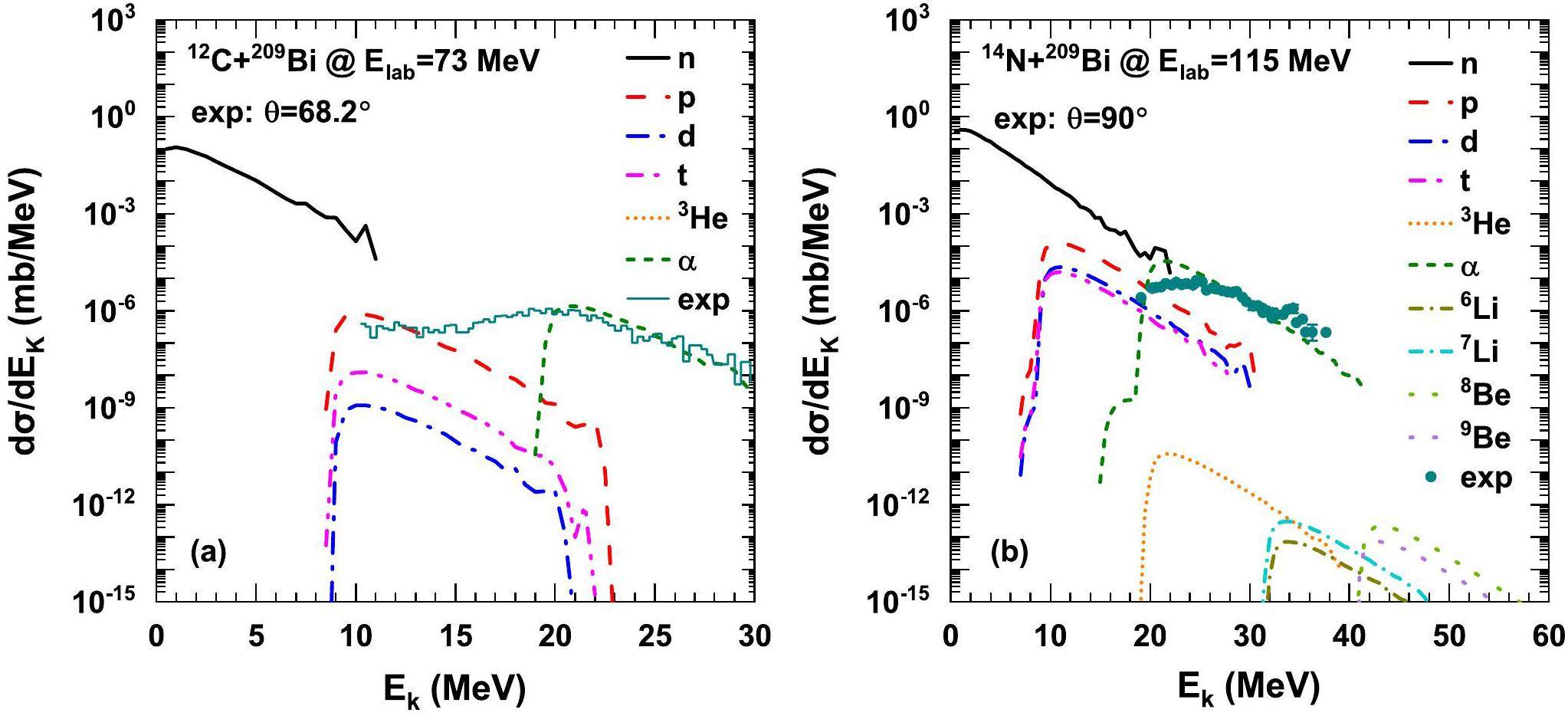

Figure 4 shows the kinetic energy spectra of the light nuclei produced in the transfer reactions 14N + 159Tb, 169Tm, 181Ta at Elab =115 MeV. It can be seen from the figure that the kinetic energy spectra of the different reactions show a similar shape, presenting the Boltzmann distribution. The emission of neutrons was the most important factor. Compared with the previous work [31], we introduced Coulomb barrier correction in this study. Hydrogen isotopes have similar emission probabilities, owing to the same amount of charge, and the peak of their kinetic energy spectrum is approximately 10 MeV. Because α and 3He are more charged, the kinetic energy spectra move in the direction of greater energy (i.e., to the right in the picture). In addition, we can see from Fig. 4 that the emission probability of α is approximately three to five orders of magnitude higher than 3He, because the former has a lower separation energy and is more easily emitted from the DNS fragments. The calculation results above are consistent with experimental data [12, 14].

In Fig. 5, we show the kinetic energy spectra of the pre-equilibrium clusters (n, p, d, t, 3He, α, 6,7Li, 8,9Be) in the transfer reactions induced by 12C and 14N to the same target nucleus 209Bi. The kinetic energy spectra of these pre-equilibrium particles in the transfer reactions show the nuclear structure effect and the dynamic characteristics of the nuclear reaction. The available experimental data for the α emission from the HIRFL for the massive transfer reaction of 12C+209Bi [14] and from RIKEN for 14N+209Bi [12] are well reproduced with the DNS model. The excitation energy of DNS fragments, transition probability, binding energy, and separation energy of the transferred nucleons (clusters) affect the kinetic energy spectra. The emission cross-section of the preequilibrium cluster is mainly related to its formation probability and emission probability. In our calculation, it is assumed that the clusters already exist in the DNS; therefore, the emission cross-sections of different clusters are mainly determined by the emission probabilities. The higher the charge of the emitted particle, the higher the Coulomb barrier. However, the larger the separation energy of the cluster, the smaller the decay width and the lower the emission probability. The kinetic energy spectra of the clusters are strongly related to the Coulomb barriers and excitation energies of the composite system.

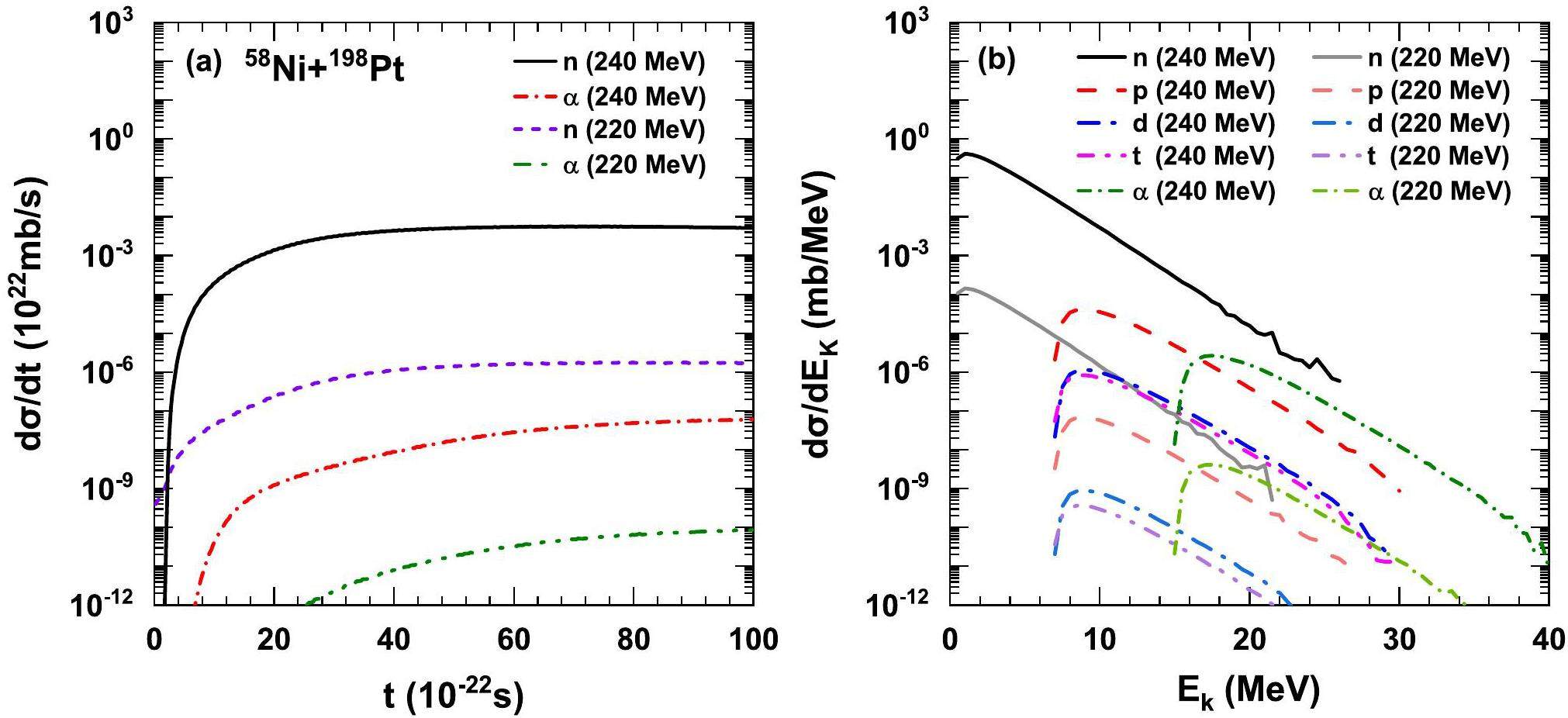

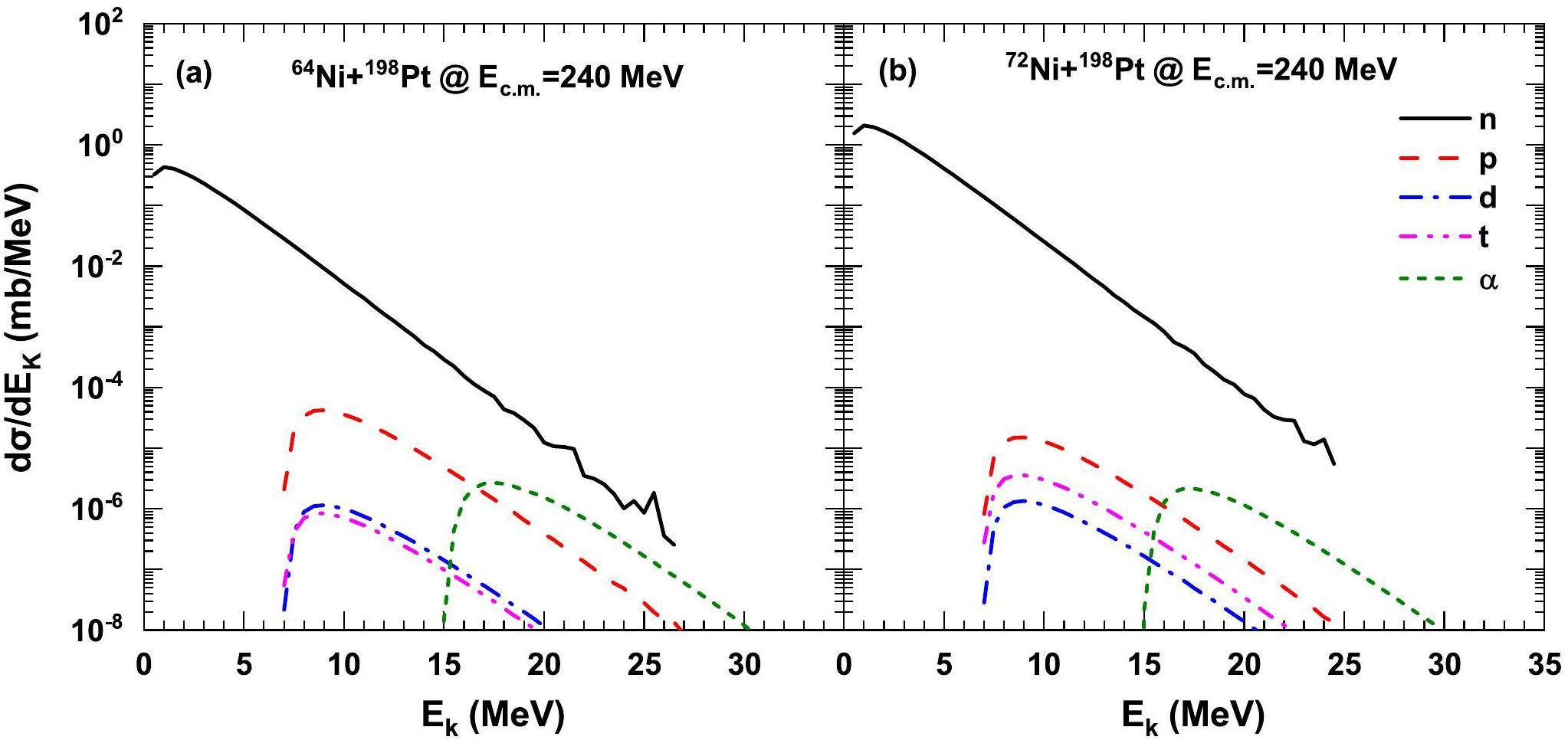

The emission of the pre-equilibrium cluster is not only related to the reaction system, but also to the incident energy. Figure 6 shows a comparison of the time evolution and kinetic energy distribution of the transfer reaction, 58Ni+198Pt, at incident energies of 220 and 240 MeV. The left part of this figure shows the temporal evolution, and the right part shows the kinetic energy spectra of the pre-equilibrium particles. The kinetic energy of the pre-equilibrium cluster is mainly determined by the local excitation energy of the projectile-like and target-like fragments, and a high local excitation energy is beneficial to cluster emission. We can see that the emission probability at Ec.m. = 240 MeV is about 2 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than at Ec.m. = 220 MeV, indicating that the emission probability of the pre-equilibrium clusters increased with the incident energy. In Fig. 7, we compare the transfer reactions of bombarding the target nucleus 198Pt with heavier isotopes of Ni at Ec.m. = 240 MeV, on the left is the kinetic energy spectra of the pre-equilibrium clusters emitted in the 64Ni+198Pt reaction, and on the right is the reaction of 72Ni+198Pt. Compared with the reaction system of 64Ni+198Pt, the reaction induced by 72Ni seems to be more likely to emit neutrons, but the former is more likely to emit protons. In both reaction systems, the peak of the kinetic energy spectra of the proton isotopes was approximately 9 MeV, while the peak of α kinetic energy spectra was approximately 17 MeV.

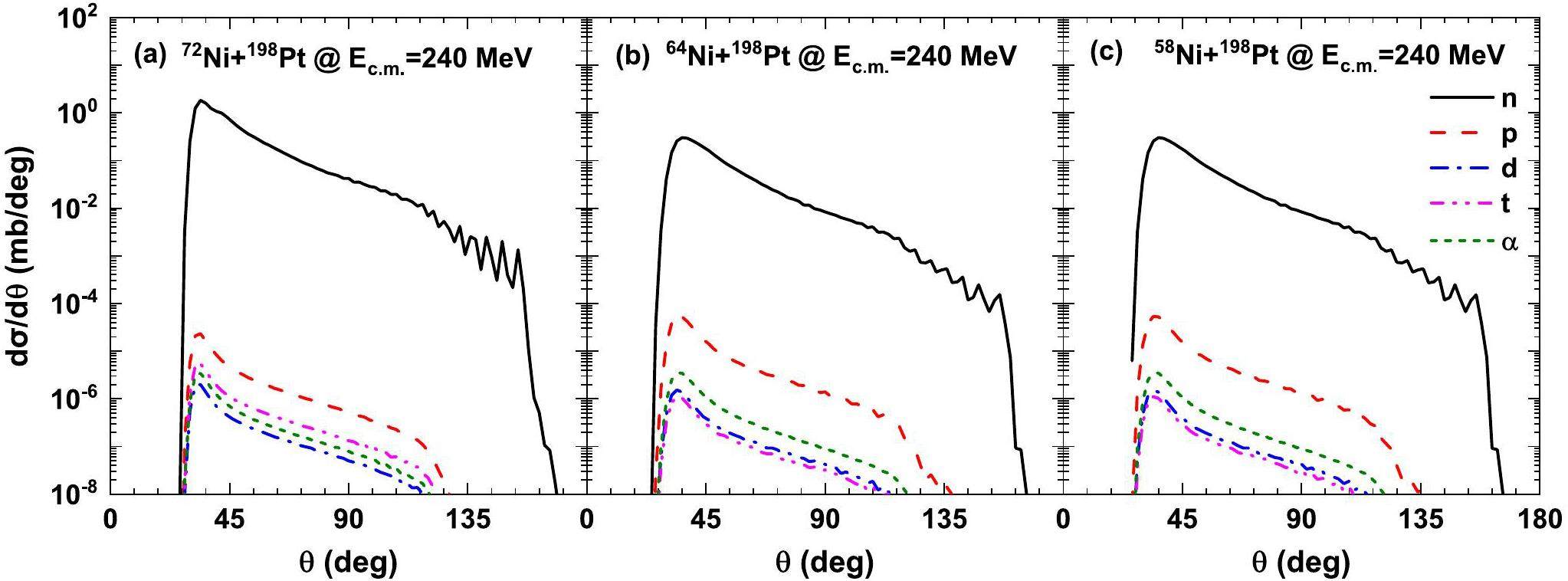

The particles emitted in the pre-equilibrium process and from the compound nucleus have different kinetic energies and angular distributions [51]. Direct particles primarily emit in the same direction as the incident particles and have similar energy to each other, while the particles of the compound process emit in all directions, in equal amounts forward and backward. Pre-equilibrium particles tend to be emitted forward and are generally more energetic than those from the composite nucleus. Shown in Fig. 8 is the angular distributions of the emitted pre-equilibrium clusters in 58,64,72Ni+198Pt at Ec.m.=240 MeV. The angular distribution was different for different reaction systems. For the same reaction system, the shapes of the angular distributions of different clusters are quite similar because different clusters may evaporate from the same excited DNS fragment. It can also be seen from the figure that the angular distributions of the pre-equilibrium particles are anisotropic, and their shapes show characteristics similar to of those the angular distributions of fragments in multinucleon transfer reactions [39, 50]. In the program calculation, we ignored the values for which the output was less than 1E-10. Under the three reaction systems, the angular distributions of the particles increased rapidly when the angle of the center of mass system was approximately 26 and reached a maximum value between 32 and 36. There is a window of 32–160 for the pre-equilibrium neutron emission. The study of the angular distribution of pre-equilibrium clusters in the transfer reaction is of great significance to the study of the angular distribution of the primary fragments in the MNT reaction and is helpful for the management of experimental measurements.

Conclusion

In summary, within the framework of the DNS model, we investigated the emission mechanism of the preequilibrium clusters in the massive transfer reactions near the Coulomb barrier energies, that is, the temporal evolution, kinetic energy spectra, and angular distributions of n, p, d, t, 3He, α, 6,7Li, 8,9Be in collisions of 12C+209Bi, 14N+159Tb, 169Tm, 181Ta, 197Au, 209Bi, and 58,64,72Ni+198Pt. Cluster transfer and dynamic deformation are coupled to the relative dissipation of the angular momentum and motion energy in the DNS model. The emission of preequilibrium clusters strongly depends on the incident energy, separation energy, and Coulomb barrier from the primordial DNS fragments. The yields of hydrogen isotopes and α production have similar magnitudes but are more probable than those of heavy particles. The kinetic energy spectra manifest the difference of charged particles, that is, more kinetic energy for the α emission than the ones of protons. The pre-equilibrium clusters follow the MNT fragment emission on the angular distributions and are related to the correlation of the nucleons. The reaction mechanism is helpful for investigating the cluster structure of atomic nuclei and MNT fragment formation, that is, the yields, shell effect, and emission dynamics, which are being planned for future experiments at HIAF in Huizhou.

Clustering property of nucleus

. Nuclear Physics Review 12, 18-21 (1995). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.12.03.018The systematic structure-change into the molecule-like structures in the self-conjugate 4n nuclei

. Progress of Theoretical Physics Supplement 68, 464-475 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.E68.464The 5α condensate state in 20Ne

. Nature Communications 14, 8206 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43816-9The 5α condensate state in 20Ne

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 35, 35 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01385-6Cluster emission, transfer and capture in nuclear reactions

. Physics Reports 374, 1-89 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(02)00268-5Novel approach to light-cluster production in heavy-ion collisions

. Physical Review C 109,Kinetic approach of light-nuclei production in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Physical Review C 108,Unveiling the dynamics of little-bang nucleosynthesis

. Nature Communications 15, 1074 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45474-xNew isotopes 29,30Mg, 31,32,33Al, 33,34,35,36Si, 35,36,37,38P, 39,40S and 41,42Cl produced in bombardment of a 232Th target with 290MeV 40Ar ions

. Nuclear Physics A 176, 284-288 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(71)90270-3Systematics of nucleon transfer between heavy ions at low energies

. Nuclear Physics A 176, 299-320 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(71)90272-7Transfer reactions in the interaction of 40Ar with 232Th

. Nuclear Physics A 215, 91-108 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(73)90104-8Preequilibriumα-particle emission in heavy-ion reactions

. Nuclear Physics A 334, 127-143 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(80)90144-Xα particle emitted in the reaction of 12C on 209Bi

. Chinese Physics C 1, 70-78 (1977).Product cross sections for the reaction of 12C with 209Bi

. Nuclear Physics A 349, 285-300 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(80)90455-8Discovery of isotopes of elements with Z≥100

. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 99, 312-344 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2012.03.003The study of multi-nucleon transfer reactions for synthesis of new heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Physics of Particles and Nuclei Letters 19, 693-716 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477122060085Discovery of new isotope 241U and systematic high-precision atomic mass measurements of neutron-rich Pa-Pu nuclei produced via multinucleon transfer reactions

. Physical Review Letters 130,High intensity heavy ion accelerator facility (HIAF) in china

. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 317, 263-265 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.08.046Deep inelastic transfer reactions-the new type of reactions between complex nuclei

. Physics Reports 44, 93-157 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(78)90200-4Effective nucleus-nucleus potential for calculation of potential energy of a dinuclear system

. International Journal of Modern Physics E 05, 191-216 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301396000098Treatment of competition between complete fusion and quasifission in collisions of heavy nuclei

. Nuclear Physics A 627, 361-378 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)00605-2Fusion cross sections for superheavy nuclei in the dinuclear system concept

. International Journal of Modern Physics E 633, 409-420 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00124-9Fusion probability in heavy-ion collisions by a dinuclear-system model

. Europhysics Letters 64, 750 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2003-00622-0Entrance channel dependence of production cross sections of superheavy nuclei in cold fusion reactions

. Chinese Physics Letters 22, 846 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/22/4/019Production cross sections of superheavy nuclei based on dinuclear system model

. Nuclear Physics A 771, 50-67 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2006.03.002Formation of superheavy nuclei in cold fusion reactions

. Physical Review C 76,Production of new superheavy Z=108-114 nuclei with 238U, 244Pu, and 248,250Cm targets

. Physical Review C 80,Production of heavy and superheavy nuclei in massive fusion reactions

. Nuclear Physics A 816, 33-51 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2008.11.003Influence of entrance channels on the formation of superheavy nuclei in massive fusion reactions

. Nuclear Physics A 836, 82-90 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.01.244Systematics on production of superheavy nuclei Z = 119-122 in fusion-evaporation reactions

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 32, 103 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00946-3Preequilibrium cluster emission in massive transfer reactions near the coulomb barrier energy

. Physical Review C 107,Nuclear constitution and the interpretation of fission phenomena

. Physical Review 89, 1102-1145 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.89.1102Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: How accurately can we describe it and calculate the cross sections?

Physical Review C 65,Effect of cluster transfer on the production of neutron-rich nuclides near N=126 in multinucleon-transfer reactions

. Physical Review C 108,Characteristics of quasifission products within the dinuclear system model

. Physical Review C 68,Nuclear clusters as a probe for expansion flow in heavy ion reactions at (10–15)A gev

. Physical Review C 55, 1443-1454 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.55.1443Formation and dynamics of exotic hypernuclei in heavy-ion collisions

. Physical Review C 102,Relaxation times in dissipative heavy-ion collisions

. Zeitschrift für Physik A Atoms and Nuclei 290, 47-55 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01408479Analysis of relaxation phenomena in heavy-ion collisions

. Zeitschrift für Physik A Atoms and Nuclei 284, 209-216 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01411331Distribution of the dissipated angular momentum in heavy-ion collisions

. Physical Review C 27, 590-601 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.27.590Production of heavy isotopes in transfer reactions by collisions of 238U+238U

. Physical Review C 80,Production of neutron-rich isotopes around N=126 in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Physical Review C 95,Interaction barrier in charged-particle nuclear reactions

. Physical Review Letters 31, 766-769 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.31.766Nuclear masses and deformations

. Nuclear Physics 81, 1-60 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(66)90639-0Production of neutron-rich actinide isotopes in isobaric collisions via multinucleon transfer reactions

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 160 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01314-zStatistics and nuclear reactions

. Physical Review 52, 295-303 (1937). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.52.295A statistical approach to describe highly excited heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Chinese Physics C 40,Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations

. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 59, 185-381 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.1995.1002Influence of pre-fission particle emission on fragment angular distributions studied for 208Pb(16O,f)

. Physical Review C 45, 719-725 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.45.719Production of neutron-rich heavy nuclei around N = 162 in multinucleon transfer reactions

. The European Physical Journal A 58, 162 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00819-2Pre-equilibrium processes in nuclear reactions

. Nature 292, 671-672 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1038/292671a0The authors declare that they have no competing interests.