Introduction

The multipole response and appearance of pygmy dipole resonance (PDR) in finite nuclei far from the β-stability line have become hot issues in nuclear physics [1, 2]. Pygmy dipole resonance, which corresponds to the collective motion between the neutron skin and saturated core, has gained considerable attention because of its important applications in nuclear astrophysics and nuclear physics [3-7]. For example, the PDR found in the isovector giant dipole resonance could have a pronounced effect on the neutron capture rate in r-process nucleosynthesis. The properties of PDR are also used to constrain the equation of state of asymmetric nuclear matter [8-12], it plays similar role as the neutron skin in nuclear physics [13, 14].

PDR has been widely studied over the years, both experimentally and theoretically, using various methods [15-28]. In contrast, pygmy monopole resonance (PMR) has been much less analyzed experimentally in neutron-rich nuclei, and it has been theoretically predicted in neutron-rich Mg [29, 30], Ca [30-32], Ni [30, 33, 34], Sn, and Pb [35-37] isotopes. The calculations were based mainly on discretized quasiparticle random phase approximation (QRPA) or the finite amplitude method. It has been shown that PMR may significantly reduce the incompressibility in the nucleus with pronounced neutron excess, which could provide a more general and deeper understanding of nuclear incompressibility in isospin asymmetric systems [35]. Therefore, the measurement of isoscalar giant monopole resonances (ISGMR) and confirming the existence of PMR in neutron-rich nuclei are very important in nuclear physics. Following the suggestion of theoretical results, the ISGMR was measured by Vandebrouck et al. in the neutron-rich nucleus 68Ni using inelastic α scattering at 50A MeV in inverse kinematics with the active target MAYA at GANIL [38, 39]. The pygmy monopole strength was observed at 12.9 MeV in addition to isoscalar giant monopole resonance. However, in the case of giant monopole resonance, excitations are usually built on the 2ℏω particle-hole configurations, which indicates that the particle states involved in all low-energy monopole excitations may be embedded in the continuum. Thus, correct treatment of the continuum in a neutron-rich nucleus is required to explain the experimental results.

In Refs. [40, 41], the nonrelativistic and relativistic continuum random phase approximations (CRPA) with Green’s function method were used to calculate the monopole strength distributions of 68,78Ni, and the calculations indicated that there was no pronounced monopole state below the excitation energy of 20 MeV. Instead, a shoulder structure appeared in the low-energy region. This suggests that the discretized RPA may not be applicable to the calculation of the monopole response in 68Ni, which should be replaced by the CRPA with Green’s function method. CRPA calculations show that there is no PMR for 68,78Ni. However, it is unclear whether PMR exists in more neutron-rich Ni isotopes. In this work, we focus on the evolution of ISGMR in neutron-rich Ni isotopes, particularly with respect to its low-energy strength.

The PMR in an open-shell nucleus cannot be accurately described by the CRPA with Green’s function method because the pairing correlation is not considered. Hagino and Sagawa formulated a continuum quasiparticle random phase approximation (CQRPA) for open-shell nuclei in the coordinate space representation in Ref. [42]. The nucleon-nucleon interactions for the ground state adopted the Woods-Saxon type. For the residual interactions in the CQRPA calculations, they used the t0 and t3 parts of the Skyrme residual interactions. In this study, we extend the CQRPA model in Ref. [42] in a more consistent manner and applied it to study the ISGMR in neutron-rich Ni isotopes. In the new CQRPA model, the Schrödinger equation with a Woods-Saxon mean-field potential was replaced by the Hartree-Fock mean field theory with the standard Skyrme interaction in the ground state calculations. The Landau-Migdal forms of residual interactions derived from the Skyrme energy density functional (EDF) are adopted in the CQRPA calculations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we briefly introduce our theoretical framework. In Sect. 3, the CQRPA monopole strength distributions were investigated. The low-energy strengths of more neutron-rich Ni isotopes were studied carefully to explore the PMR. Finally, Sect. 4 provides summary and perspective.

Theoretical framework

In this work, the Skyrme Hartree-Fock + Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (HF+BCS) and CQRPA methods were employed to study pygmy monopole resonance in neutron-rich nickel isotopes. The Skyrme interaction is expressed as an effective zero-range force between nucleons with density- and momentum-dependent terms, which has been successfully applied in the description of various nuclear properties [43, 44]. In this study, the Skyrme force SLy5 [45] was adopted for ground and excited state calculations. The pairing correlation is generated by a density-dependent zero-range force

The CQRPA model is briefly reviewed as follows. Further details are provided in Ref. [42]. The CQRPA response function

The monopole strength distribution S(E) of the system to an external field

Results and discussions

First, we briefly discuss the ground-state properties of the nickel isotopes. The ground-state properties of finite nuclei are depicted using the HF+BCS method [50-52]. The HF+BCS equation is solved in coordinate space, where the radial size is set to 20 fm, which guarantees that the results under study are stable.

Table 1 shows the binding energies per nucleon, the neutron (proton) separation energies, charge radii and neutron Fermi energies in even-even 68-84Ni isotopes calculated by using the SLy5 Skyrme interaction, meanwhile the calculated results are compared with the corresponding experimental data.

| Eb (MeV) | Sn (MeV) | Sp (MeV) | Rch (fm) | λn (MeV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68Ni | 8.71(8.68) | 6.99(7.79) | 14.47(15.43) | 3.91(3.89) | -7.09 |

| 70Ni | 8.64(8.60) | 6.11(7.31) | 15.76(16.12) | 3.93(3.91) | -6.24 |

| 72Ni | 8.56(8.52) | 5.45(6.89) | 17.04(17.15) | 3.95 | -5.62 |

| 74Ni | 8.46(8.43) | 4.95(6.66) | 18.29(18.02) | 3.96 | -5.13 |

| 76Ni | 8.36(8.34) | 4.53(6.02) | 19.50(18.92) | 3.98 | -4.70 |

| 78Ni | 8.26(8.24) | 3.29(5.60) | 20.69(20.26) | 3.99 | -2.40 |

| 80Ni | 8.10(8.09) | 1.70(3.15) | 21.46 | 4.01 | -1.86 |

| 82Ni | 7.94(7.94) | 1.44(2.70) | 22.18 | 4.03 | -1.60 |

| 84Ni | 7.78 | 1.11 | 22.85 | 4.04 | -1.17 |

It can be seen that the binding energies per nucleon decrease with increasing mass number, and the calculated values can reproduce the measurements well. The neutron separation energies of 68-82Ni predicted by the Skyrme EDF are somewhat smaller than the experimental data, but the calculated results can reproduce the data tendency with respect to the mass number well. In Table 1, it is shown that the theoretical proton separation energies Sp are in good agreement with the experimental data. We also show the calculated charge radii of even-even 68-84Ni isotopes in the table, which increase with increasing mass number. For the studied nuclei, only two nuclei, 68,70Ni, had experimental charge radii data. These results were well reproduced by the calculations. The calculated neutron Fermi energies are presented in the last column of Table 1, one can see that the neutron Fermi energies are approaching to zero when the nuclei are becoming more and more unstable.

For neutron-rich nickel nuclei, the discretized RPA has been proven to be unreliable, whereas Green’s function technique can properly take into account the contribution from the continuum [40, 41]. Therefore, CQRPA was adopted to explore the PMR in more neutron-rich Ni isotopes in the present study. As mentioned above, the residual interactions in the CQRPA calculations adopt the Migdal form. This means that the interactions used in CQRPA are not the same as those used in the ground-state calculations. We adjusted the residual interactions to ensure that a spurious isoscalar dipole state appeared at zero excitation energy, and the value of the renormalization factor was approximately 0.8.

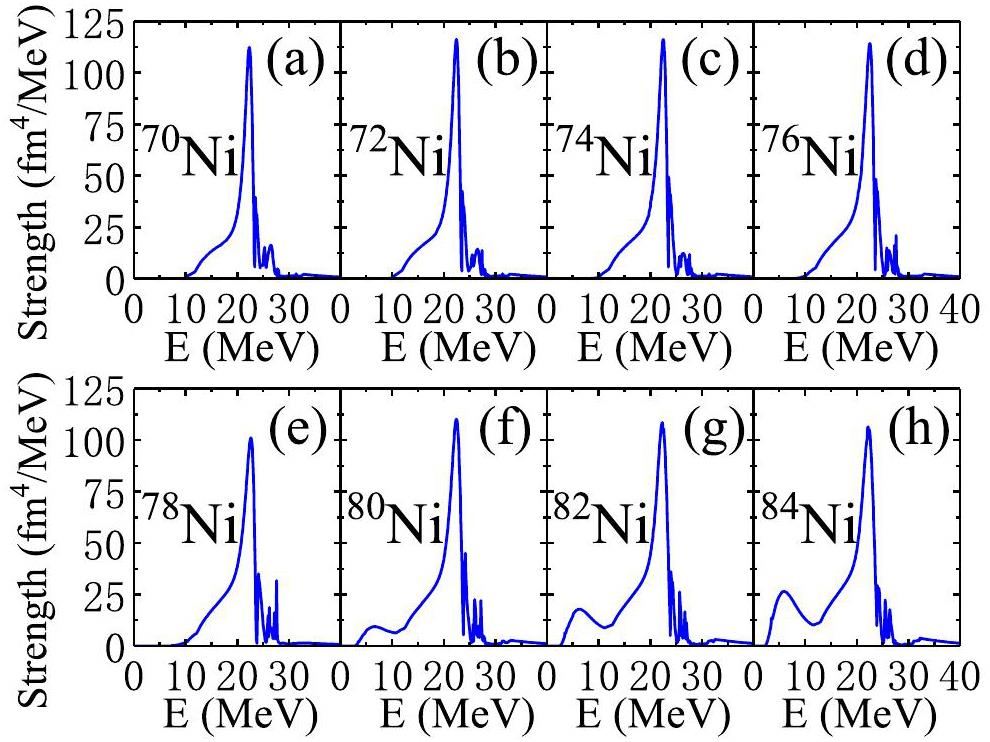

The CQRPA monopole strength distributions for 70-84Ni are shown in Fig. 1. One can see the monopole strengths for 70-78Ni increased monotonically from the particle threshold to the ISGMR peak at approximately 21 MeV. This implies that a shoulder structure appears in the low-energy region for 70-78Ni. This is consistent with the conclusions of Refs. [40, 41], there is no PMR for 70-78Ni. However, starting from 80Ni, the particle threshold becomes much lower, and an obvious PMR emerges in the energy region between 2.5 and 11 MeV. With the increasing of mass number, the low-energy strength becomes more and more strong.

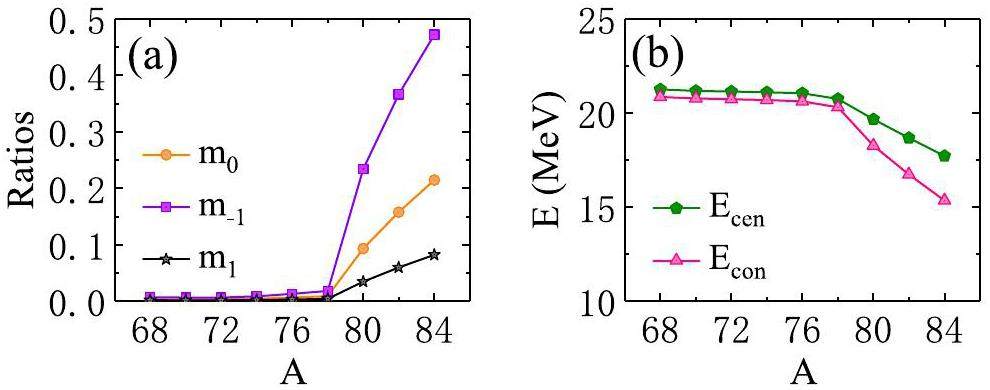

We separated the low-energy PMR from the giant monopole resonance at an excitation energy of E=11 MeV, and calculated the ratios of the low-energy strength to the whole ISGMR strength for the non-energy-weighted sum rule m0, inverse energy-weighted sum rule m-1 and energy-weighted sum rule m1, respectively. As illustrated in Fig. 2(a), the ratios of m0 (orange circles), m-1 (purple squares), and m1 (black stars) of the low-energy strength are almost zero until mass number A=78. From 80Ni, the three ratios increased significantly, and the values became larger in more neutron-rich nuclei. This suggests that the contribution of the PMR below 11 MeV increases with increasing mass number. The centroid energies Ecen (green pentagons) and constrained energies Econ (pink triangles) are plotted as functions of the mass number in Fig. 2(b), which is similar to Fig. 2(a), the values of Ecen and Econ remain constant when the mass number is not greater than 78, whereas the two energies are significantly decreased from 80Ni to 84Ni because of the appearance and enhancement of the low-energy monopole strengths. The values of Ecen are somewhat higher than those of Econ along the Ni isotopic chain, especially for 80-84Ni.

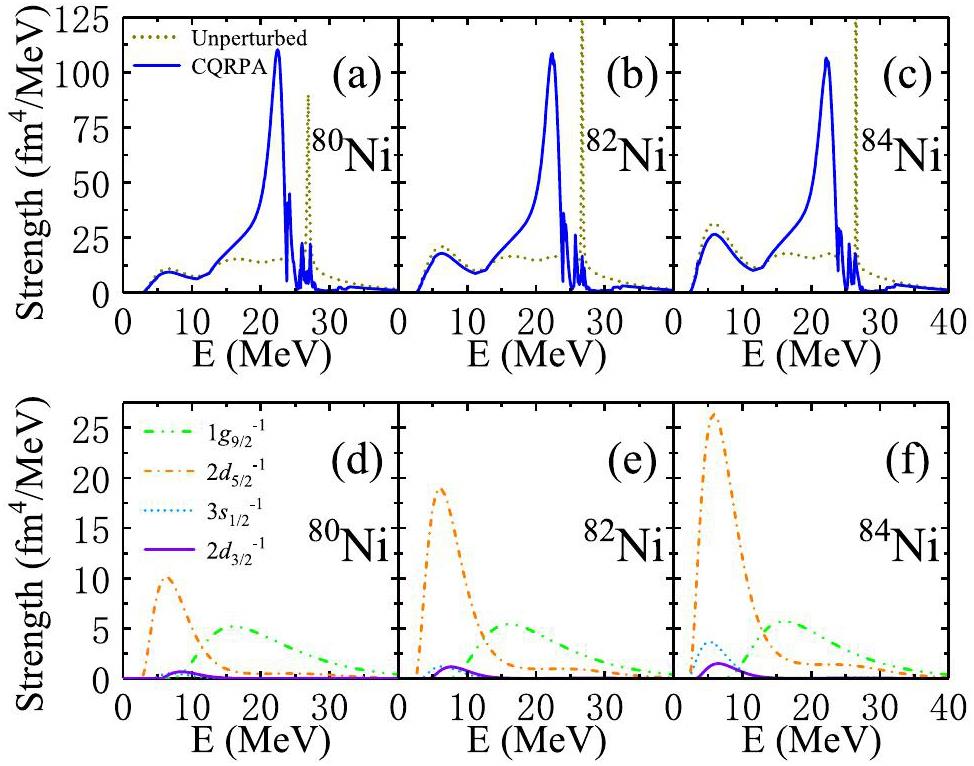

In this paragraph, quasiparticle excitations in the low-energy region will be carefully investigated because these excitations may contribute significantly to the PMR strengths. The unperturbed and CQRPA monopole strengths of 80-84Ni are shown in Fig. 3(a)-(c). For the giant monopole resonance, the CQRPA strengths are shifted down to a lower energy compared to the distribution of unperturbed strengths because the attractive residual interactions play an important role in isoscalar monopole excitation. The PMR strengths were slightly reduced compared to the unperturbed strengths, but the locations were almost unchanged. It can be seen that the low-energy strengths are highly sensitive to neutron excess. It was found that the low-energy strength below 20 MeV shown in the figures is made of the excitations mainly contributed by neutron states around the Fermi level, including 1g9/2, 2d5/2, 3s1/2, and 2d3/2. The corresponding single-particle energies Es.p., gaps Δ, quasiparticle energies Eq.p. and occupation probabilities v2 are listed in Table 2. We noticed that the single-particle energies of the four neutron states become increasingly bound with an increase in the neutron excess. It is shown that the gaps of the four neutron states are rather stable at approximately 0.6 MeV. The neutron states 2d5/2 are just above or below the Fermi energies; therefore, the quasiparticle energies are relatively small. As for states 1g9/2, 3s1/2 and 2d3/2, they are a little far from the Fermi energies, and their quasiparticle energies are relatively large except for state 3s1/2 in 84Ni, because its single-particle energy is much closer to the Fermi energy. One can see that the occupation probabilities of 1g9/2 are almost 1.0, leading to relatively stable excitations. Other partially occupied orbits (2d5/2, 3s1/2 and 2d3/2) changed their occupation probabilities when the neutron excess was increased. The corresponding unperturbed neutron threshold strengths, contributed by the excitation of neutrons around the Fermi surface to the continuum, are gradually enhanced[see Fig. 3(d)-(f)]: The occupancy probabilities of 2d5/2 are increased much more than the other states with the filling of neutrons, from 0.33 in 80Ni increased to 0.92 in 84Ni. Therefore, the increase in low-energy strengths in 80-84Ni is mainly due to the contribution of a stronger threshold strength of 2d5/2.

| 80Ni | 82Ni | 84Ni | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Es.p. | Δ | Eq.p. | v2 | Es.p. | Δ | Eq.p. | v2 | Es.p. | Δ | Eq.p. | v2 |

| 1g9/2 | -5.80 | 0.73 | 4.01 | 0.99 | -5.94 | 0.77 | 4.41 | 0.99 | -6.08 | 0.57 | 4.94 | 1.00 |

| 2d5/2 | -1.62 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.33 | -1.81 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.64 | -2.01 | 0.53 | 0.99 | 0.92 |

| 3s1/2 | -0.40 | 0.4 | 1.52 | 0.02 | -0.59 | 0.45 | 1.11 | 0.04 | -0.78 | 0.38 | 0.55 | 0.14 |

| 2d3/2 | 0.34 | 0.55 | 2.28 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 1.84 | 0.03 | -0.08 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 0.04 |

Summary and Perspectives

In the present study, we extended the CQRPA approach in Ref. [42] in a more consistent manner, in which the model includes the Skyrme interaction for both ground and excited state calculations. Then, the consistent Skyrme HF+BCS and CQRPA models were applied to explore the emergence, evolution, and origin of low-energy monopole strengths along the even-even Ni isotopes. Shoulder structures at low-energy region for 70-78Ni are found, which are similar to the conclusions in Refs.[40, 41]. However, the situation changed dramatically with the occupation of the weakly bound neutron orbitals. Indeed, starting from 80Ni, pronounced pygmy monopole strengths were clearly identified. The origin of the low-energy monopole strength is attributed to neutron excitations from the weakly bound orbitals into the continuum, including neutron states 1g9/2, 2d5/2, 3s1/2 and 2d3/2. The changes in the ratios of low-energy strengths to total ISGMR strengths for m-1, m0 and m1 as well as the centroid and constrained energies along Ni isotopes, are also discussed, and the changes are more obvious when the mass numbers are larger than 78, which are attributed mainly to the emergence of low-energy strengths. Eventually, the experimental data of PMR in neutron-rich nuclei are obviously inadequate, more efforts from the experimental investigations of PMR shall be made to confirm or disprove the predictions from models in the future.

Exotic modes of excitation in atomic nuclei far from stability

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 70,Experimental studies of the Pygmy Dipole Resonance

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 70, 210 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.02.003Low-lying dipole response in the relativistic quasiparticle time blocking approximation and its influence on neutron capture cross sections

. Nucl. Phys. A 823, 26 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2009.03.009Pygmy resonances and radiative nucleon captures for stellar nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Continuum random-phase approximation for (n,γ) reactions on neutron-rich nuclei: Collective effects and resonances

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Random forest-based prediction of decay modes and half-lives of superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01354-5Measurements of 27Al(γ, n) reaction using quasi-monoenergetic γ beams from 13.2 to 21.7 MeV at SLEGS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 66 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01662-yNuclear symmetry energy and neutron skins derived from pygmy dipole resonances

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Constraints on the symmetry energy and neutron skins from pygmy resonances in 68Ni and 132Sn

. Phys. Rev. C 81,Connecting the pygmy dipole resonance to the neutron skin

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Constraining symmetry energy from pygmy dipole resonances in 68Ni and 132Sn

. Chin. Phys. C 49,Symmetry Energy and Isovector Giant Dipole Resonance in Finite Nuclei

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 25, 1625 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/0256-307X/25/5/028Neutron skin and its effects in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01584-1New quantification of symmetry energy from neutron skin thicknesses of 48Ca and 208Pb

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01551-wEvidence for Pygmy and Giant Dipole Resonances in 130Sn and 132Sn

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95,Decay Pattern of Pygmy States Observed in Neutron-Rich 26Ne

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101,Search for the Pygmy Dipole Resonance in 68Ni at 600 MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,Emergence of pygmy dipole resonances: Magic numbers and neutron skins

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Probing surface quantum flows in deformed pygmy dipole modes

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Electric dipole strength and dipole polarizability in 48Ca within a fully self-consistent second random-phase approximation

. Phys. Lett. B 777, 163 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.12.026Theoretical studies of Pygmy Resonances

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 129,Importance of self-consistency in relativistic continuum random-phase approximation calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Soft dipole modes in neutron-rich Ni-isotopes in QRRPA

. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 19, 2845 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217732304015233Application of relativistic continuum random phase approximation to giant dipole resonance of 208Pb and 132Sn

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 61 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01288-5Pygmy dipole resonances in the relativistic random phase approximation

. Phys. Rev. C 63,Pygmy and giant dipole resonances in proton-rich nuclei 17,18Ne

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 34,Low-lying dipole resonance in neutron-rich Ne isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Low-energy dipole excitations in neon isotopes and N=16 isotones within the quasiparticle random-phase approximation and the Gogny force

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Emergent soft monopole modes in weakly bound deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Low-energy monopole strength in spherical and axially deformed nuclei: Cluster and soft modes

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Emergence of low-energy monopole strength in the neutron-rich calcium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Soft breathing modes in neutron-rich nuclei with the subtracted second random-phase approximation

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Low-energy monopole strength in exotic nickel isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Evolution of soft monopole mode in the even-even nickel isotopes 58-68Ni

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Incompressibility of finite fermionic systems: Stable and exotic atomic nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Feasibility of the finite-amplitude method in covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Toward a unified description of isoscalar giant monopole resonances in a self-consistent quasiparticle-vibration coupling approach

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Measurement of the isoscalar monopole response in the neutron-rich nucleus 68Ni

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113,Isoscalar response of 68Ni to α-particle and deuteron probes

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Self-consistent Hartree-Fock and RPA Green’s function method indicate no pygmy resonance in the monopole response of neutron-rich Ni isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Nuclear breathing mode in neutron-rich nickel isotopes: Sensitivity to the symmetry energy and the role of the continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Continuum QRPA in the coordinate space representation

. Nucl. Phys. A 695, 82 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)01122-8Self-consistent mean-field models for nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 121 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.75.121Self-consistent RPA calculations with Skyrme-type interactions: The skyrme-rpa program

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 142 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2012.07.016A Skyrme parametrization from subnuclear to neutron star densities Part II. Nuclei far from stabilities

. Nucl. Phys. A 635, 231 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00180-8Empirical pairing gaps, shell effects, and di-neutron spatial correlation in neutron-rich nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 940, 210 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2015.04.010The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Skyrme-Landau parameterization of effective interactions: (II). Self-consistent description of giant multipole resonances

. Nucl. Phys. A 534, 25 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(91)90556-LNuclear charge radii of the nickel isotopes 58-68,70Ni

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Microscopic study of the isoscalar giant monopole resonance in Cd, Sn, and Pb isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Effect of pairing correlation on low-lying quadrupole states in Sn isotopes

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Feng-Shou Zhang is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.